39

石油・天然ガスレビュー

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

JAPAN AND THE ARCTIC:

NOT SO POLES APART

Within the last two decades, the Arctic has

transformed from a forgotten backwater at the

end of the Cold War to becoming a focus of

increased international attention. The Arctic

Council was set up in Ottawa, Canada in 1996

among the eight Arctic states: Canada, Denmark,

Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the

U.S.. Its own history cites its formation as to serve

“as a high-level intergovernmental forum to provide

a means for promoting cooperation, coordination

and interaction among the Arctic States, with the

involvement of the Arctic indigenous communities

and other Arctic inhabitants on common Arctic

issues; in particular, issues of sustainable development

and environmental protection in the Arctic.”

*1

In short,

it had a limited mandate, only to issues pertaining to

protection of the environment and the indigenous

peoples. In fact, during its formative years, it garnered

little attention, and was even ignored by its eight

creators. The Arctic Council toiled in the margins of

international affairs, its membership described as cozy

and club-like.

*2

After all the Arctic was a remote and foreboding

place, attracting the attention of only “cranks,

visionaries and dictators.”

* 3

U.S. President William

Taft(1909-1913) thought ownership of the North Pole

to be useless. By the mid-20th century, the region

became a major theater of the Cold War. In the former

Soviet Union, Stalin(leader of the Soviet Union from

1 9 2 4 t o 1 9 5 3), i n h i s r e l e n t l e s s d r i v e f o r

JOGMEC Washington Office

Jasmin Sinclair

この20年間で、北極地帯は冷戦終結以来の“忘れ去られた僻地”から国際的関心が集まる地域へと変

貌を遂げた。2013年5月15日、北極評議会は、その設立から17年後に、明らかに北極地帯の国家とは

言えないアジア諸国である中国、インド、日本、韓国、シンガポールに対して恒久的オブザーバーとし

ての参加を認めた。これら非北極・非西洋諸国からの関心と参加は、この地域の重要性の高まりを裏付

け、反映させるものとなっている。特に、中国、日本、韓国からの関心は、経済的可能性によって動機

付けられている。本稿では、北極評議会参加諸国間の外交的・協調的取り組みとともに、日本独自の取

り組みや、炭化水素資源採掘・北極航路に関わる潜在的な角逐あるいは協力可能な分野に関して焦点を

当てる。

は

じめに

1.

The Arctic Council evolving

Table

The Arctic Council

Member States

Observer States

Canada

Denmark(Greenland)

Iceland

Finland

Norway

Russia

Sweden

U.S.A.

China

*

France

Germany

India

*

Italy

*

Japan

*

The Netherlands

Poland

South Korea

*

Singapore

*

Spain

United Kingdom

*:Admitted in May 2013

Source:The Arctic Council, http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/

40

2014.3 Vol.48 No.2

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

industrialization, created gulags and mines in the

Russian Arctic. The 1970s saw the opening up of the

North Slope of Alaska to oil development. At the end

of the Cold War, the Arctic was relegated as an

afterthought on the international stage.

Seemingly, in the blink of an eye, everything

changed. In 2006, NASA showed pictures of melting

polar ice caps. In 2007, a Russian Arctic scientist laid

claim to the North Pole by planting his nation’s flag on

the seabed in an election campaign publicity stunt.

* 4

The geopolitical race was on as accessibility to the

Arctic became a tangible reality. The Arctic Council

was soon thrust in the international arena. Seventeen

years after its founding, the Arctic Council granted

permanent observer status to five decidedly non-polar

Asian nations: China, India, Japan, Singapore, and

South Korea.

* 5

The Arctic was once the province of

the five littoral states(Canada, Greenland, Norway,

Russia, and the U.S.). But attention of and participation

from non-Arctic European nations and now Asian

nations underscore and reflect the growing importance

of the region.

*6

The Arctic is now global.

The Arctic Council’s visibility has ascended hand-in-

hand with the increased changes in the Arctic due to

accelerated climate change.

* 7

In granting non-Arctic

nations the status of permanent observers, the Arctic

Council has broadened the emphasis of its raison d’être.

In addition to its prior emphasis on advancing

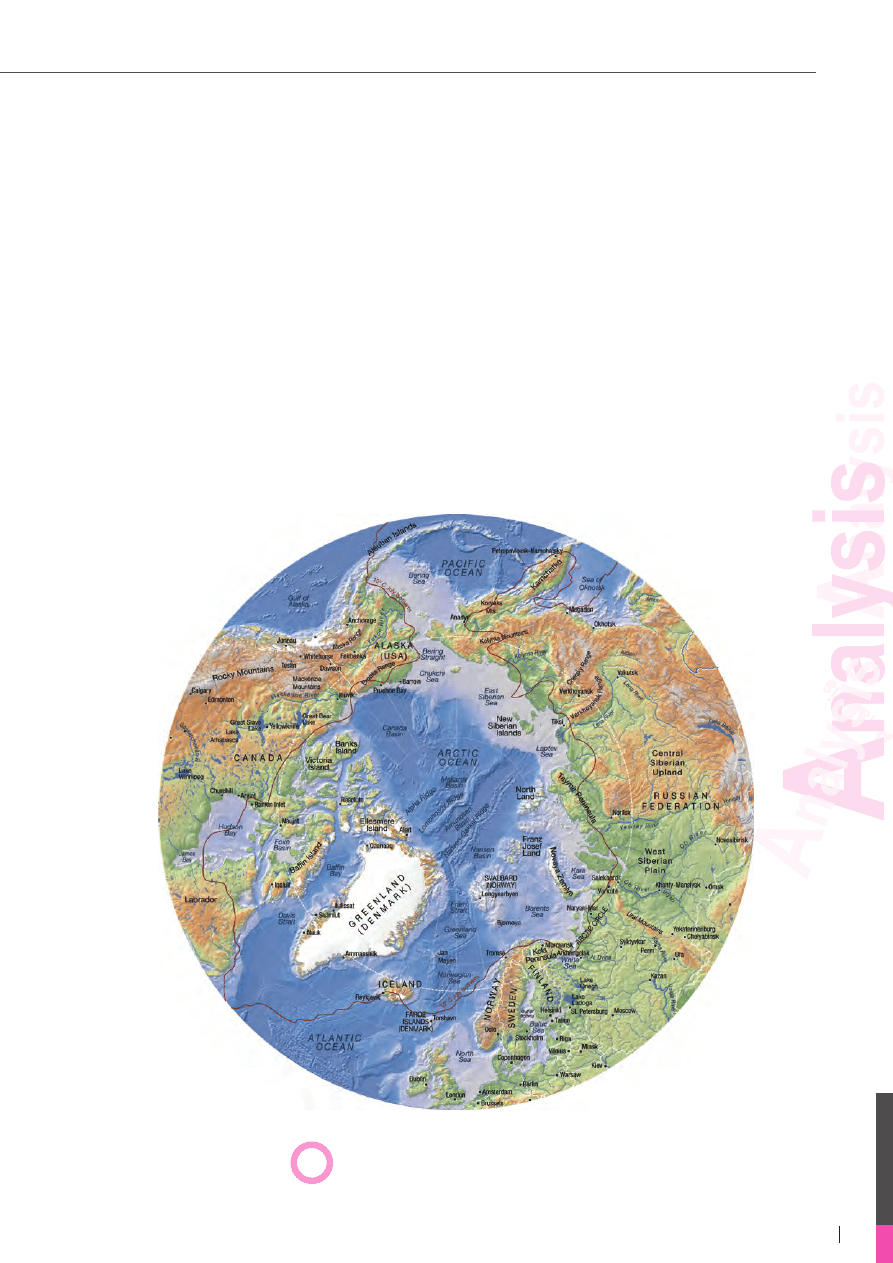

Source: Hugo Ahlenius, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, http://www.grida.no/graphicslib/detail/arctic-topography-and-bathymetry-

topographic-map_d003

Fig1

Political topographic map of the Arctic

41

石油・天然ガスレビュー

JOGMEC

K Y M C

JAPAN AND THE ARCTIC:NOT SO POLES APART

sustainable development of the Arctic while preserving

and conserving its unique ecosystems, the Arctic

Council placed a new emphasis on increased cooperation

and interaction with business.

*8

This development also

reflects how the future of Arctic affairs will more than

likely be influenced by Asian nations. The main drivers

are economic in nature. New sea routes in the Arctic—

the North West Passage(NWP)and the Northern Sea

Route(NSR)cut travel time and distance by 30% and

offer cheaper transit, compared to the traditional

southern route whereby ships pass through the Strait

of Malacca and the Suez Canal.(South Korea has

dubbed the NSR as the “Silk Road of the Twenty-First

Century.”)The second economic driver for the nations

of East Asia is the Arctic’s abundant resources.

*9

The effects of climate change on the Arctic means

that the Arctic’s geography is changing. One of the

more tangible effects of this change is that Arctic

waters are open for passage during most of the

summer months. The effects of climate change happen

more rapidly than anywhere else in the world.

* 10

Melting sea ice will soon allow extended navigation

periods in the Arctic Ocean, with the potential to

transform commercial shipping

* 11

, giving rise to new,

shorter sea lanes. Shipping traffic in the Arctic could

rise dramatically.

The Arctic also holds 13% of the world’s undiscovered

oil, along with 30 % of undiscovered natural gas and

20% of undiscovered natural gas liquids.

*12

Furthermore,

according to the U.S. Geological Survey, 84 % of the

undiscovered oil and gas occurs offshore of the Arctic

littoral states.

*13

It is no wonder that industry and government

representatives are full of high hopes. But despite large

ocean stretches, the Arctic remains inhospitable, with

long and dark winters, and areas far from search and

rescue facilities.

* 14

Indeed, the Arctic represents

special hazards, such as the danger of icing on

installations, long distances between offshore fields and

land and lack of infrastructure.

*15

And yet, despite the

bleakness, the prospect of the Arctic as a resource

base has opened new economic potential.

It is against this backdrop that this paper will

explore Japan’s increased interest in the Arctic.

Having succeeded to permanent observer status in the

Arctic Council, Japan has the potential to help shape

the challenges emerging as the Arctic changes. Japan

brings “considerable financial, scientific and legitimating

capacity to the Council.”

* 16

As do its two competing

East Asian neighbors, China and South Korea, also

newly-minted permanent observers to the Arctic

Council. All three countries are deeply dependent on

foreign trade. Their aims of establishing partnerships

among the Arctic states are understandable.

a) Formative Years in Developing an Arctic

Strategy

In August 2012, one of Japan’s top newspapers, the

Yomiuri Shimbun, wrote that “Japan has started out

late in the game[of Arctic affairs].” The article

excoriated Japan’s governance, saying it was at risk of

lagging behind, in contrast to China and South Korea.

Indeed, of its two neighbors, Japan was the last to file

2.

The Arctic itself evolving

3.

JAPAN IN THE ARCTIC

42

2014.3 Vol.48 No.2

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

its application to obtain observer status to the Arctic

Council.

* 17

As recently as four years ago, Japanese

policymakers paid scant attention to the Arctic.

* 18

In

reality, Japan has a long history in polar research,

acknowledged and encouraged by the Japanese

government, predating its two neighbors.

* 19

Its early

focus was on Antarctica in 1957. In the 1990s, the

Nippon Foundation and the Ship & Ocean Foundation

(now the Ocean Policy Research Foundation), worked

with Norway and Russia. Together they formed the

International Northern Sea Route Program(INSROP),

a six-year project, whose purpose was to study the

viability and feasibility of Arctic shipping lanes.

* 20

INSROP morphed into the Japan Northern Sea Route

Program(JANSROP)and JANSROP II. Covering a

three-year span(2002-2005), its aim was to study the

NSR for the Japanese shipping industry.

*21

But due to

Japanese companies’ skepticism of Arctic shipping

routes, combined with Japan’s economic decline

starting in the 1990s, shipping companies concluded

the risks far outweighed potential benefits.

Japanese companies backed off, but government

efforts on formulation of an Arctic policy continued

apace. In 2009, Japan officially submitted its application

for Permanent Observer status to the Arctic Council.

*22

In 2010, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs(MOFA)

established an Arctic Task Force under the Ocean

Division, International Legal Affairs Bureau, “in order

to make cross-sectoral approach towards the foreign

policy on the Arctic including the aspect of international

law.”

* 23

Since November 2012, officials from MOFA

have attended Arctic Council meetings. And in 2012, a

major think-tank, the Japan Institute of International

Affairs(JIIA), released a research project entitled,

"Arctic Governance and Japan's Diplomatic Strategy",

bolstering government efforts.

*24

b) Japan’s Movers and Shakers in Arctic

Affairs

Japan’s process in formulating public policy has been

described as being an “iron triangle,” consisting of the

civil service, politicians, and business interests.

*25

It can

be characterized as symbiotic or parasitic, depending

o n o n e’s p o i n t o f v i e w . B u s i n e s s e s l o b b y t h e

government. The civil service looks to business for

information. Businesses look to the government on

trade issues. This process also applies to formulation of

Arctic policy.

i)Ministerial Level

▪Ministry of Foreign Affairs(MOFA)

▪ Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and

Tourism(MLIT)

▪ Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science

and Technology(MEXT)

▪ Ministry of Defense(MOD)

ii) Research Organizations, Think-Tanks,

Independent Agencies

*26

▪ The Ocean Policy Research Foundation(OPRF)

▪ National Institute for Polar Research(NIPR)

▪ Japan Institute of International Affairs(JIIA)

▪ Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation

(JOGMEC)

▪ Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and

Technology(JAMSTEC)

▪ Institute of Low Temperature Science(ILTS)

▪ Japan Consortium for Arctic Environmental

Research(JCAR)

▪ Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency(JAXA)

iii)Private Institutions

▪ Energy and Shipping Companies

c)The Attraction of the Arctic for Japan

As a maritime nation, the Japanese government

understandably has a deep interest in the promotion

and usage of Arctic passageways. One shipping route,

the NSR, passes through the Arctic Ocean connecting

the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean.

* 27

With

melting sea ice resulting from global climate change,

the commercial potential of the route is becoming more

tangible. Traffic is certainly increasing. According to

Rosatomflot, a Russian state-run corporation that

guides ships through the Arctic with nuclear-powered

icebreakers, the number of cargo ships taking the NSR

has jumped from 4 in 2010 to 34 in 2011, representing

a more than eight-fold increase.(In contrast, the Suez

Canal handled 17,799 trips in the same year.)

*28

But

43

石油・天然ガスレビュー

JOGMEC

K Y M C

JAPAN AND THE ARCTIC:NOT SO POLES APART

because the navigation season has now lengthened to

four months a year, from July to mid-November, NSR

traffic can only grow. As of mid-September 2013, 531

vessels received transit permits.

*29

i)Shipping

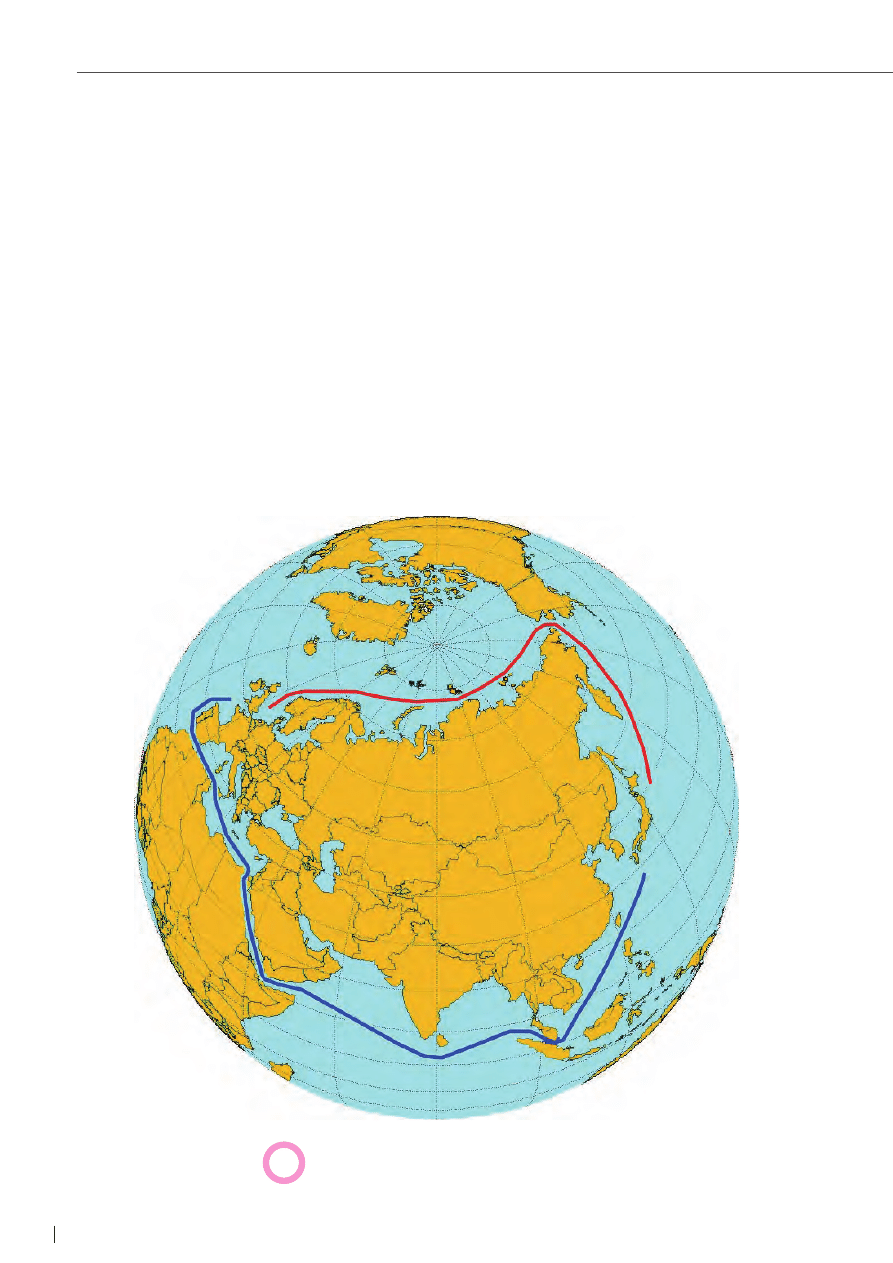

The NSR has long been viewed as a short-cut

linking Asia to Europe via Russia’s Arctic coast.

Japanese and South Korean energy companies are

already shipping oil products through the ice. Last

year, Gazprom shipped liquefied natural gas(LNG)

to Japan. In August 2013, Norway sent two

shipments of oil products(one of them naphtha)to

Japan. Using the NSR on a return trip from Asia

to Europe, South Korea sent high-quality diesel to

Europe.

*30

Utilizing the NSR has obvious advantages than

the traditional southern route through the Strait of

Malacca and Suez Canal. The first advantage is

distance. The NSR is 3,900 nautical miles(7,223

km)shorter than the southern route which is over

11,000 nautical miles(20,372 km). Along with

shaving distance, the second advantage is that

voyage time is also saved. Cargoes transiting

through the Suez Canal can take approximately 35

days. The NSR cuts the travel time by up to 20

days.

*31

The NSR’s third advantage lies in saving money

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sevmorput%27.jpg

Fig2

Comparing the Northern Sea Route in red

and transit via the Suez Canal in blue

44

2014.3 Vol.48 No.2

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

and lives by avoiding security risks. By transiting

through the NSR, ships can effectively lower the

possibility of pirate encounters. The Strait of

Malacca and the Gulf of Aden are notorious havens

for pirates, who board ships and kidnap their

crews for ransom. This translates into higher in-

surance premiums for carriers and the risk of

losing lives. Rounding the Africa’s Cape of Good

Hope is available, but this route would be longer in

terms of distance and time, and again, would add

to shipping costs.

*32

To sum up the costs and benefits of the NSR for

commercial shipping, the time and distance saved

transiting through the NSR is offset by higher

costs. Despite saving fuel, carriers still have to pay

higher transit fees to Russia, along with ensuring

the use of icebreakers. Foreign ships are also

required to notify the Russian government three

months in advance. Some Japanese observers see

Russian bureaucracy as more formidable than

Arctic ice.

*33

One CEO predicts that the NSR will

take another 10 to 20 years to become truly viable

for container ships.

* 34

The Secretary-General of

the International Maritime Organization, Koji

Sekimizu states that icebreaker support is more

than necessary, as ice will remain a big issue even

during summer. Safety protocols and mitigation of

oil spills and accidents will also grow as the

volume of traffic increases.

* 35

The most likely

scenario for the NSR is that it will be dominated

by transport of oil and gas instead of cargo ships.

Indeed the energy sector stands to profit from use

of the NSR, as Asian LNG markets are best

positioned for European exporters. Japan can take

advantage of being a hub port due to its close

proximity to the Bering Strait.

*36

ii)Energy

Japan’s energy imports surged in the wake of

the Fukushima crisis in March 2011. The nuclear

plant meltdown led to the shutdown of the nation’s

48 reactors.

* 37

Japan’s nuclear industry once

supplied one-third of the nation’s power, with

p l a n s t o i n c r e a s e i t u p t o 5 0% b y 2 0 3 0 .

* 3 8

Implementation of these plans is doubtful, as

nuclear power supplied only 2% of electric

generation in 2012.

*39

Nuclear energy will remain

a key source of base-load power, as a December

2013 draft of the new Basic Energy Plan states.

*40

Once Asia’s largest nuclear power producer, Japan

recorded its first trade deficit since 1980 due to

increased reliance on imported LNG to offset the

loss of its nuclear capacity. The 2011 trade deficit

totaled ¥2.49 trillion(US$32 billion).

* 41

Japan

imported 79.4 million tons of LNG from January to

November 2013.

* 42

Japan has diversified its

energy mix, importing crude from Iran. But this

entails political risk, with U.S. sanctions ever-

looming on banks companies conducting business

with Iran. In May 2013, crude imports from Iran

more than doubled compared to the previous year.

The U.S. extended Japan’s exemption for another

six months.

*43

Japan lacks sufficient domestic hydrocarbon

resources, meeting less than 15 % of its primary

energy usagge from domestic resources. It is the

world’s largest LNG importer, ranking second

behind China in coal imports, and third in oil imports

behind the U.S. and China.

*44

It is thus in Japan’s

best interest to “cultivate a diversity of resource

exporting partners.”

* 45

For Japan, then, the NSR

could spell a boon in terms of diversifying its energy

mix, in part, due to its large northern ports in

Hokkaido. The business community is finally seeing

the potential of the Arctic. Indeed, Japan received

its first tranche of LNG via the Arctic from

Norway’s Snohvit LNG project in Hammerfest. It

arrived in Kitakyushu City on December 5, 2012.

*46

Thus, Japan’s domestic energy security is a major

driver in its attraction to the Arctic as it seeks to

diversify its supplies and suppliers.

With this aim in mind, Japan Oil, Gas and Metals

National Corporation(JOGMEC), an independent

administrative agency tendered a bid in 2011 for

the right to develop an oil field off the coast of

Greenland. On December 24, 2013, JOGMEC was

awarded this right.

* 47

JOGMEC has teamed up

45

石油・天然ガスレビュー

JOGMEC

K Y M C

JAPAN AND THE ARCTIC:NOT SO POLES APART

w i t h I N P E X , J X , J A P E X a n d M i t s u i O i l

Exploration to explore two blocks of total 5,000

square kilometers.

* 48

It is a joint project with

Chevron and Shell. In addition, JOGMEC and

ConocoPhillips and the U.S. Department of Energy

conducted successful tests off Alaska's North Slope

for the extraction of natural gas from methane

hydrates.

*49

In a nexus of business interests combining with

government aims, MOFA appointed Masuo Nishibayashi

as Ambassador to the Arctic in March 2013.

*50

Amb.

Nishibayashi is only one of two specially appointed

from Asia. The second is Kemal Siddique from

Singapore. The Japanese position is a newly-created

post, which speaks to Japan’s attempts to demonstrate

its commitment to the Arctic.

* 51

Amb. Nishibayashi

s t a t e s t h a t i t i s n e c e s s a r y f o r J a p a n t o b e

“appropriately involved” in Arctic discussions. He

continues: “The ice is melting and this means ships

will be able to pass through. We have to see if this is

commercially viable.”

*52

Japan will need this engagement with the Arctic

Council as it strives to secure diverse energy resources.

The Arctic can provide that for Japan. Its diplomatic

contacts with Nordic and Baltic nations will ensure its

involvement in developing the riches of the Arctic.

*53

Japan has also established bilateral relations with

Finland to promote development of the Arctic.

*54

Japan’s open relations with the Arctic nations will put

i t i n g o o d s t e a d i n t e r m s o f e n e r g y r e s o u r c e

development. In particular, talks with Russia could result

in ameliorating tensions over the Kuril Island, which

have prevented Russia and Japan from signing a peace

treaty formally ending WW II hostilities.

* 55

Another

reason for their cooperation is to compete with China.

*56

China’s assertive policies in the Arctic notwithstanding,

Japan and Russia are moving closer to one another in

earnest. In early February 2014 Russian President

Vladimir Putin and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

met. This was the fifth high-level meeting between the

two countries in less than a year. Russia’s foray into

Asia is for diplomatic purposes and for securing a

diversified energy client base. Closer ties to Japan would

ensure Russia leverage in Asian relations before China’s

ascendancy is cemented. As for energy, China is Russia’s

biggest Asian customer. Should Japan also become a

Russian customer, Russia could use energy both as a

diplomatic and commodity bargaining chip.

*57

Russia’s

East Asian customer base would be solidified.

The advantages for Japan lie in resources, shipping

routes, and diplomacy. Japan has already scored a plus

in resources. In May 2013, INPEX Corporation secured

a partnership with Rosneft to explore two Arctic oil

fields.

*58

In terms of diplomacy and alliances, Russia lent

its weight to support Japan’s bid to become a permanent

observer in the Arctic Council, ignoring China. Moscow

also supported Tokyo’s application to hold the 2020

Olympic Games.

Although China and Japan are currently involved in

escalating spats in the East China Sea, it should be

noted that while Moscow and Tokyo are warming to

each other, neither would overtly do something to mar

their relations with Beijing. In spite of recent heated

rhetoric in Sino-Japanese relations, Prime Minister Abe

reiterated that “the two countries could never clash. We

must not let that happen.”

*59

4.

CONCLUSION

46

2014.3 Vol.48 No.2

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

<注・解説>

*1: http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about-us/arctic-council/history

*2: Waldie, Paul, “Arctic Council seeks balance as commerce beckons in the Far North,” The Globe and Mail,

October 16, 2013, accessed at http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/looking-up-the-far-norths-

global-appeal/article14898080/

*3: Emmerson, Charles, “The Cold Rush: Attraction of the North Pole,” Chatham House, The World Today, Volume

69, Number 7, accessed at hhttp://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/The%20World%20

Today/2013/AugSep/WT0413Emmerson.pdf

*4: Byers, Michael, “Great Powers Shall Not in the Arctic Clash,” Global Brief, November 11, 2013, accessed at

http://globalbrief.ca/blog/2013/11/11/great-powers-shall/

*5: http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/about-us/arctic-council/observers. The European Union also applied

as a permanent observer, but its application is being upheld due to the EU's dispute with Canada over an EU ban

on trade in seal products.

*6: Jegorova, Natalja, “Regionalisation and Globalisation: The Case of the Arctic, Arctic Yearbook 2012, accessed at

http://www.arcticyearbook.com/images/Articles_2013/JEGOROVA% 20AY13% 20FINAL.pdf, p. 125

*7: Jakobson, Linda, “Northeast Asia Turns Its Attention to the Arctic,” NBR Analysis Brief, December 17, 2012,

accessed at http://nbr.org/publications/analysis/pdf/Brief/121712_Jakobson_ArcticCouncil.pdf

*8: Käpylä, Juha and Harri Mikkola, “The Global Arctic: The Growing Arctic Interests of Russia, China, the United

States and the European Union,” November 8, 2013, Finnish Institute of International Affairs(FIAA), accessed

at http://www.isn.ethz.ch/layout/set/print/content/view/full/24620?lng=en&id=172671

*9: Wilson, Page, “Asia Eyes the Arctic,” The Diplomat, August 26, 2013, accessed at http://thediplomat.

com/2013/08/asia-eyes-the-arctic/

*10: Emmerson, Charles, Glada Lahn, “Arctic Opening: Opportunity and Risk in the High North,” http://www.

chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Energy,%20Environment%20and%20

Development/0412arctic.pdf, p. 8

*11: Humpert, Malte, and Andreas Raspotnik, “The Future of Arctic Shipping Along the Transpolar Sea Route,” The

Arctic Yearbook 2012, accessed at http://arcticyearbook.com/images/Articles_2012/Humpert_and_Raspotnik.

pdf, p. 299

*12: The subject of the Arctic’s oil and gas potential was explored in an earlier paper. The numbers are based upon

USGS, July 23, 2008, http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=1980&from=rss_home

*13: USGS, http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3049/fs2008-3049.pdf, p. 4

*14: Simon, Bernard, “The Arctic: Through icy waters,” Financial Times, August 18, 2011, accessed at http://

www.ft.com/cms/s/2/7f2c025e-c731-11e0-a9ef-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2sw2Qftar

*15: Fouche, Gwladys, “Oil firms must speed up efforts on Arctic safety – Norway watchdog,” Reuters, November 21,

2013, accessed at http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/11/21/norway-exploration-safety-

idUKL5N0J53YR20131121. The safety watchdog is the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway.

*16: Manicom, James and Whitney Lackenbauer, “East Asian States, The Arctic Council and International Relations

in the Arctic,” CIGI Policy Brief No.26, accessed at http://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/no26.pdf, p. 5

*17: The article was cited by Jakobosn, Linda and Syong-Hong Lee,”The Northeast Asian States’ Interests in the

Arctic and Possible Cooperation with the Kingdom of Denmark,” SIPRI, April 2013, accessed at http://www.

sipri.org/research/security/arctic/arcticpublications/NEAsia-Arctic%20130415%20full.pdf, p. 19

*18: Ibid.

*19: Tonami, Aki and Stewart Watters, “Japan’s Arctic Policy: The Sum of Many Parts,” Arctic Yearbook 2012,

accessed at http://www.arcticyearbook.com/images/Articles_2012/Tonami_and_Watters.pdf, p. 93

*20: Tulupov, Dmitry, “Towards The Arctic Ocean through the Kuril Islands,” Russian International Affairs Council,

47

石油・天然ガスレビュー

JOGMEC

K Y M C

JAPAN AND THE ARCTIC:NOT SO POLES APART

April 15, 2013, accessed at http://russiancouncil.ru/en/inner/?id_4=1711#top

*21: Tonami, A. and Watters, S., p. 95

*22: Tonami, A. and Watters, S., p. 96

*23: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. (2010). Launching of the "Arctic Task Force (ATF)". [Press Release]

accessed at http://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/announce/2010/9/0902_01.html

*24: Tulupov, C.

*25: Tonami, A. and Watters, S., p. 94

*26: Jakobson, L. and Lee, S., pp. 20-23

*27: Toriumi, Shigeki, “The Potential of the Northern Sea Route,” Yomiuri Shimbun, February 28, 2011, accessed at

http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/adv/chuo/dy/opinion/20110228.htm

*28: Matsuo, Ichiro and Takashi Kida, “Northern Sea Route heats up between Europe, East Asia,” Asahi Shimbun,

August 21, 2012, accessed at http://ajw.asahi.com/article/economy/business/AJ201208210040

*29: Rodova, Nadia, “Russia’s Northern Sea Route: Global Implications,” Platts Commodity News, September 26,

2013, accessed at http://www.platts.com/news-feature/2013/oil/euro-nsr/index

*30: Yep, Eric, “Energy Companies Try Arctic Shipping Shortcut Between Europe and Asia,” The Wall Street

Journal, August 21, 2013, accessed at http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324619504579026031

203525734

*31: Rodova, N. and Yep, E.

*32: Toriumi, S.

*33: Jakobson, L. and Lee, S.

*34: Maersk: Arctic Shipping "Not a Short-Term Opportunity", Ship and Bunker News, October 11, 2013, accessed at

http://shipandbunker.com/news/world/441225-maersk-arctic-shipping-not-a-short-term-opportunity

*35: Chernov, Vitaly and Nadezhda Malysheva, “IMO Secretary-General Koji Sekimizu: “In the forthcoming five

years, the Northern Sea Route will be the main shipping lane for navigation in the Arctic”, Portnews IAA,

October 18, 2013, accessed at http://en.portnews.ru/comments/1691/

*36: Toriumi, S.

*37: Reynolds, Isabel and Takashi Hirokawa, “Hosokawa Targets Tokyo’s Clout in Japan Nuclear Debate,” Bloomberg

News, January 22, 2014, accessed at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-01-21/hosokawa-targets-tokyo-s-

economic-clout-in-japan-nuclear-debate.html

*38: Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose, “Ageing Japan faces ‘chronic’ trade deficit after Fukushima,” The Telegraph,

January 24, 2012, accessed at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/9036792/Ageing-Japan-faces-

chronic-trade-deficit-after-Fukushima.html

*39: Japan Country Analysis Brief, Energy Information Administration(EIA), October 29, 2013, accessed at http://

www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=JA

*40:

“Nuclear Power in Japan,” World Nuclear Association, December 27, 2013, accessed at http://www.world-

nuclear.org/info/Country-Profiles/Countries-G-N/Japan/

*41: Dickie, Mure, “Japan records first trade deficit since 1980,” Financial Times, January 25, 2012, accessed at

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/e4f868c0-4738-11e1-b847-00144feabdc0.html

*42: Sheldrick, Aaron and James Topham, “Japan’s TEPCO plans for LNG buyers’ group, with 40 mln T/yr target,”

Reuters, January 17, 2014, accessed at http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/01/17/japan-lng-procurement-

idUSL3N0KR21M20140117

*43: Ivanov, Georgi, “Japan and the Arctic: directions for the 21st century,” The World Outline, August 28, 2013,

accessed at http://theworldoutline.com/2013/08/japan-the-arctic/

*44: See No. 39.

*45: Toriumi, S

48

2014.3 Vol.48 No.2

JOGMEC

K Y M C

アナリシス

執筆者紹介

Jasmin Sinclair(ヤスミン シンクレア)

College of Charleston, Political Science/International Relations 卒業(B.A.)。

JET プログラム(The Japan Exchange and Teaching Program)で来日し、鹿児島県で 3 年間英語教育に携わる。帰米後、在米国日

本大使館(ワシントン)勤務を経て、2001 年 1 月に JNOC(石油公団)ワシントン事務所の調査員として任用、現在に至る。休日は

家族とともに古武術の道場で鍛錬に励む。その他の趣味は料理と映画鑑賞。

*46: Motomura, Masumi, “Arctic Circle Energy Resources and Japan’s Role,” JIIA, 2012 Research Project Outcome:

"Arctic Governance and Japan's Diplomatic Strategy", accessed at http://www2.jiia.or.jp/en/pdf/research/2012_

arctic_governance/02e-motomura.pdf, p. 1

*47: JOGMEC.(2013). Successful Award of Exploration Licenses Offshore Greenland[Press Release]accessed at

http://www.jogmec.go.jp/english/news/release/news_10_000011.html

*48: See No.47.

*49: U.S. Department of Energy. (2012). U.S. and Japan Complete Successful Field Trial of Methane Hydrate

Production Technologies [Press Release] accessed at http://energy.gov/articles/us-and-japan-complete-successful-

field-trial-methane-hydrate-production-technologies

*50: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/03/20/national/arctic-council-ambassador-named/#.UUmIzhzeSpc

*51: Bennett, Mia, “East Asian Diplomacy in the Arctic,” Foreign Policy Association, June 26, 2013, accessed at

http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2013/06/26/east-asian-diplomacy-in-the-arctic/

*52: Reynolds, Isabel, “Melting ice cap draws China, Japan to seek Arctic riches,” Bloomberg News, May 13, 2013,

accessed at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-05-13/melting-ice-cap-draws-china-japan-to-seek-arctic-riches.

html

*53:

“Tokyo ready for talks on Arctic with Nordic, Baltic nations,” Japan Times, November 11, 2013, accessed at

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2013/11/12/national/tokyo-ready-for-talks-on-arctic-with-nordic-baltic-nations/

*54:

“Japan, Finland agree to cooperate in developing Arctic,” Kyodo News International, October 18, 2013, accessed

at http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/kyodo-news-international/131018/japan-finland-agree-cooperate-

developing-arctic

*55:

“Russia and Japan may join forces in business battle for Arctic,” The Voice of Russia, February 7, 2014, accessed

at http://voiceofrussia.com/2014_02_07/Russia-and-Japan-may-join-forces-in-business-battle-for-Arctic-3898/.

*56:

“Japan, Russia plan commercial use for Arctic Ocean sea lane,” Mainichi Shimbun, October 2, 2013 , accessed at

http://www.houseofjapan.com/local/japan-russia-plan-commercial-use-for-arctic-ocean-sea-lane

*57: McGwin, Kevin, “My rival’s rival,” The Arctic Journal, February 12, 2014, accessed at http://arcticjournal.com/

politics/my-rivals-rival

*58: Pourzitakis, Stratos, “Japan and Russia: Arctic Friends,” The Diplomat, February 1, 2014, accessed at http://

thediplomat.com/2014/02/japan-and-russia-arctic-friends/

*59: McGwin, K.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Greenshit go home Greenpeace, Greenland and green colonialism in the Arctic

The?onomic Emergence of China, Japan and Vietnam

Comparison of the U S Japan and German British Trade Rivalr

Spiral syllabus The name refers not so much to the teaching content which is specified within the sy

Anna And The King How Can I Not Love You Enriquez Joy

The Not So Innocent Angel by Starvanger1

Warning to Japan Norway and the United States From the Cetaceans (DOLPHIN S CONTACTS)

Jon Scieszka Time Warp Trio 02 The NOT So Jolly Roger

Joy Enriquez How Can I Not Love You (Soundtrack Anna And The King) Partitura Piano

D Webster The Not So Peaceful Civilization A Review of Maya War

Amarinda Jones The Not So Secret Baby

Mettern S P Rome and the Enemy Imperial Strategy in the Principate

Diet, Weight Loss and the Glycemic Index

Ziba Mir Hosseini Towards Gender Equality, Muslim Family Laws and the Sharia

pacyfic century and the rise of China

Danielsson, Olson Brentano and the Buck Passers

więcej podobnych podstron