Traditional land-use and nature conservation in

European rural landscapes

Tobias Plieninger

, Franz Ho¨chtl

, Theo Spek

a

Albert-Ludwigs-University, Department of Forest and Environmental Sciences, Institute for Landscape Management,

Tennenbacher Str. 4, D-79106 Freiburg, Germany

b

National Service for Archaeological Heritage, Department of Landscape and Heritage, P.O. Box 1600,

NL-3800 BP Amersfoort, The Netherlands

1.

Introduction

Rural Europe offers a great diversity of cultural landscapes. This

landscape diversity is, for the most part, a result of the variety of

land-uses that have overlaid, refined or replaced each other

throughout history. In European landscape history five basic

stages are distinguished (

): the natural,

prehistoric landscape (from Palaeolithic till ancient Greek

times); the antique landscape (from ancient Greek times till

early Mediaeval times); the mediaeval landscape (from early

Mediaeval times till Renaissance); the traditional agricultural

landscape (from Renaissance till 19th century, sometimes till

today); and industrial landscapes (mostly from mid-18th till

mid-20th century, in many places till today). The analysis of the

function, the changes and the development of European rural

landscapes has been the commitment of the Permanent

Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape (PECSRL) since

1957 (

). In this issue we present a series of

papers from PECSRL’s 2004 meeting. The issue focuses on the

changes that traditional rural landscapes have experienced and

on the challenges of controlling their development.

2.

Interactions of traditional land-use and

conservation

Traditional land-uses include all ‘‘practices which have been

out of fashion for many years and techniques which are not

generally part of modern agriculture’’ (

). They

are supposed to have had their maximum extent in the second

half of the 19th century (

). Two common

characteristics of most forms of traditional land-use are

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 3 1 7 – 3 2 1

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Published on line 19 April 2006

Keywords:

Countryside

Cultural landscapes

Europe

Land-use

Nature conservation

a b s t r a c t

Europe’s countryside is characterised by a rich diversity of cultural landscapes and has been

shaped by traditional land-uses. These landscapes provide numerous ecological services,

e.g. the support of high levels of biodiversity. However, many traditional land-use systems

have been lost or diminished in past decades, as land-uses have polarised either toward

extensification and land abandonment or intensification. Remaining traditional land-use

systems continue to be at risk. This paper introduces a special issue of six contributions that

address land-use and landscape changes across Europe. The paper advocates a double-track

strategy in cultural landscape development: first, some remaining traditional land-use

systems should be preserved, and new tools for their economic viability be designed.

Second, the key elements of traditional land-use that provide ecological services should

be identified and integrated into future, more productive land-use systems.

#

2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Present address: Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Ja¨gerstr. 22/23, D-10117 Berlin,

Germany. Tel.: +49 30 20370 538; fax: +49 30 20370 214.

E-mail address:

(T. Plieninger).

a v a i l a b l e a t w w w . s c i e n c e d i r e c t . c o m

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / e n v s c i

1462-9011/$ – see front matter # 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:

relatively low nutrient inputs and relatively low output per

hectare. Therefore, traditional land-use systems are also

termed

‘‘low-intensity

land-use

systems’’

). However, ‘‘traditional land-use’’ is not in

all cases completely congruent with ‘‘low-intensity land-use’’

as there are traditional land-use systems that have been very

labour-intensive and had high nutrient and labour inputs.

Examples can be found in late medieval and early modern

Flanders, northern Italy, the Netherlands and southwest

England (and on a more local scale in many densely populated

areas of Europe). These traditional high-intensity systems also

had a high biodiversity, caused by the many gradients of

nutrient and labour inputs at a local and regional scale.

Although traditional land-use techniques vary consider-

ably throughout Europe, a rough categorisation into livestock

systems, arable and permanent crop systems, and mixed

systems can be made (

). Traditional land-use systems

have mainly persisted in upland and remote areas where

physical constraints have prevented a modernisation of

agriculture. The most extensive and diverse low-intensity

land-use systems can be found in Spain and Portugal (

have analysed a number of

basic principles that are characteristic for traditional land-use

systems. These are important for understanding the function-

ing of such systems and, additionally, can serve as guidelines

for the design of new land-use systems (

Principle of multiple uses: Traditional land-use systems

optimise resource use and minimise risks through poly-

culture and other forms of multiple uses. Another important

aspect of historical cultural landscapes has always been the

interaction between public, common and private land-use.

The extensive use of common lands (forests, heathlands,

grasslands and marshes) has been extremely important for

biodiversity in northwest Europe and has changed a lot over

the centuries, due to changes in agricultural systems,

economy and common rights (

Principle of rotational uses: In traditional systems land-use is

intended to meet individual needs more than to maximise

economic profit. Therefore, traditional land-use systems

involve numerous uses that are spatially and temporally

differentiated, but applied on the whole land. This leads to a

discontinuous change between periods of human impact

and periods of regeneration.

Principle of recycling: In traditional land-use, external inputs

of agrochemicals or fodder are low. Nutrient emissions and

water losses are minimised, and production wastes are re-

used as fertilizers.

Principle of low-energy economy: Traditional systems are

stamped by a scarcity of energy and transport resources.

Principle of spatial fuzziness: In traditional systems different

land-use structures and processes intermingle, although

ecological and land-use settings provide a gradient of

variation.

add principles such as a slow rate of

change that produces long periods of relative stability, man-

agement techniques that enhance the structural diversity of

vegetation, the maintenance of a high proportion of semi-

natural vegetation, and low use of agrochemicals.

The high nature-conservation value of most traditional

land-use systems is without controversy (see, for example,

, for a study on birds). Under these

circumstances it seems paradoxical that the provision of rich

biodiversity was never the primary aim of traditional land-use,

but that it was nothing more than an unintended by-product

(

). Today these amenities are considered

externalities that are uncoupled from agricultural or forestry

production and must be specially managed and financed

(

). The fact that traditional land-use in

Europe has, instead of damaging biodiversity, even fostered

habitat and species richness is remarkable as this contrasts

with the evidence from most other parts in the world

(

). Correspondingly most non-Europeans

understand conservation as an activity to restore conditions

of pristine wilderness with a complete absence of human

impact. What distinguishes traditional cultural landscapes in

Europe from other human-shaped landscapes in the world is

the long history of land-use since the retreat of the glaciation

that has facilitated the co-evolution of species, ecosystems

and man (

). Nowadays European agri-biodi-

versity is considered just as valuable as wild biodiversity

(

In addition to their nature-conservation value, cultural

landscapes are also appreciated due to their cultural values

bound to the history of a place and its cultural traditions

(

). There is an increasing recogni-

tion of the necessity to include the values and priorities of

people in any activity of natural or cultural resources

conservation. Likewise, cooperation between actors of nature

and cultural heritage conservation have been increasing

recently.

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 3 1 7 – 3 2 1

318

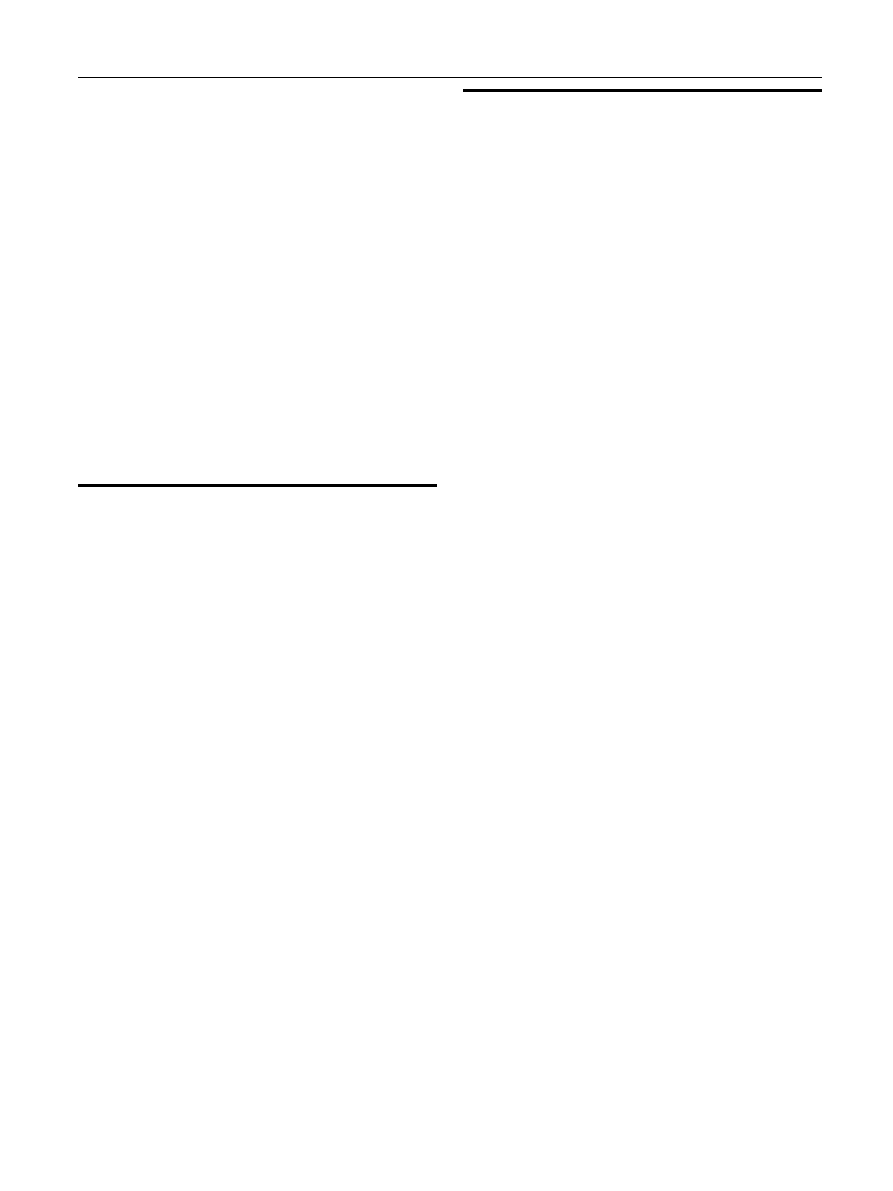

Table 1 – Traditional land-use systems in Europe

Livestock systems

Arable and permanent crop systems

Mixed systems

Low-intensity livestock raising in

upland and mountain areas

Low-intensity dryland arable cultivation

in Mediterranean regions

Low-intensity mixed

Mediterranean cropping

Low-intensity livestock raising in

Mediterranean regions

Low-intensity arable cultivation

in temperate regions

Low-intensity, small-scale traditional

mixed farming

Low-intensity livestock raising in

wooded pastures

Low-intensity rice cultivation

Low-intensity livestock raising in

temperate lowland regions

Low-intensity tree crops

Low-intensity vineyards

Source:

.

A central dilemma of Europe’s traditional cultural land-

scapes is their instability, i.e. their dependence on a medium

degree of human impact. If land-use is extensified or

abandoned traditional landscapes are displaced by sponta-

neous vegetational succession. In Portugal, for example, land

abandonment and consecutive shrub encroachment have led

to the disappearance of more than 245,000 ha of low-intensity

farmland in the 1980s (

). Con-

versely, too intensive human impact will lead to the conver-

sion of traditional landscapes to more simplified landscapes.

For instance, at least 1,400,000 ha of low-intensity farmland

has been converted into highly productive irrigated fields in

Spain since 1973 (

). This polarisa-

tion of land-use trends, with extensification or land abandon-

ment on one side (

) and mechanisation

and intensification on the other (see, for example,

), puts many traditional land-use systems seriously at

risk. Although some agri-environmental schemes provide

financial assistance for the maintenance of traditional cultural

landscapes, their impact has so far been narrow (

).

3.

The Permanent Conference for the Study of

the Rural Landscape

The Permanent European Conference for the Study of the

Rural Landscape is an international network of about 350

landscape researchers from more than 30 European countries

whose interests focus on the past, present and future of

European cultural landscapes. It was established in 1957 and

has been a constant factor in European landscape research

since. Initially, it consisted mainly of historical geographers,

but during the last few decades its membership has diversified

to include ecologists, social scientists, rural planners, land-

scape architects, human geographers, physical geographers,

historians, archaeologists, landscape managers, as well as

other scholars and practitioners interested in European

landscapes. Members undertake both fundamental and

applied research on all aspects of the rural landscape or have

a position in landscape or heritage management. PECSRL

covers Pan-Europe connecting researchers from all parts of the

continent. The main objectives of PECSRL are: (1) to facilitate

personal contacts and information exchange between Eur-

opean landscape researchers; (2) to improve interdisciplinary

cooperation between landscape researchers from various

scientific and human landscape disciplines; (3) to improve

cooperation between landscape researchers and landscape

managers; (4) to function as a platform for new initiatives in

European landscape research and landscape management. An

important medium for our network is the international

PECSRL conference, organised every two years in a different

European country. Recent conferences took place in Trond-

heim (1998), London/Aberystwyth (2000), Tartu/Otepa¨a¨ (2002)

and Lesvos/Limnos (2004). The next conference will be in

Berlin/Brandenburg (September 2006). More information

about this European landscape network is available at

. Membership is free for all those who

are interested in the field of cultural landscape research and

landscape planning.

4.

Papers on land-use and conservation in

rural areas

This issue collects some of the papers presented at the 21st

session of the Permanent Conference for the Study of the Rural

Landscape, held in Lemnos and Lesvos, Greece, in September

2004.

The array of contributions is opened with a paper by

having a methodological focus. Against the

background of a project undertaken in the Italian Alps, the

authors describe and discuss methodological procedures, as

well as the advantages and disadvantages of transdisciplinary

research. Transdisciplinarity, that is interdisciplinary inves-

tigation engaged in by academic researchers from different

disciplines and also involving non-academic participants

(

), is a buzzword currently resounding

throughout the academic landscape. It would appear to be

the final destination of applied research par excellence. Still, the

authors argue that transdisciplinarity is in no way a panacea.

Many problems, especially within basic research, can be better

analysed by applying the approved methods of one discipline.

The concept is well suited to solving problems related to the

management of public goods, however. This refers to goods

the holder cannot prevent another from consuming and in

which numerous and greatly differing individuals partake.

One such public good is the landscape.

The historical developments that still determine today

the agricultural landscape dynamics of rural regions in the

Mediterranean are the subject of

contribution. Traditional Mediterranean terraced

agricultural landscapes, as represented by the authors’

study area, the Greek island of Lesvos, have been in a steady

state of decline and in other cases have already been

completely degraded due to changes in the prevailing land-

use systems occurring in the last 150 years. Based on the

analysis of the driving forces behind Mediterranean land-

scape change caused by social, political, technological and

economic developments, the authors define cornerstones for

political intervention to counteract the negative effects of

land-use intensification on the one hand and the complete

abandonment of entire landscapes in the Mediterranean on

the other.

Since the mid-1980s there has been an intensive debate in

central Europe on the issue of nature-conservation strategies

that seek to exclude humans and their activities from the rural

landscape. Wilderness advocates have called for the establish-

ment of so-called wilderness areas in which nature may

develop completely unhindered, without human intervention,

as a means of combating progressive biodiversity loss (

). Against this backdrop, the paper presented by

Olsson and Thorvaldsen (this issue)

represents an apparent

paradox in that they have demonstrated that nature-con-

servation principles based on the exclusion of anthropogenic

influence can even lead to an acceleration in species decline.

The results of the authors’ research into eider (Somateria

mollissima L.) population dynamics, its dependence upon

habitat quality, as well as past and present human land-use

practices reveal the hazards associated with focusing on very

narrow guiding principles when dealing with nature con-

servation.

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 3 1 7 – 3 2 1

319

How can the ecological and cultural values of Scandinavian

semi-natural grasslands be maintained and developed? This is

the leading question in

paper entitled

‘‘Biodiversity and the local context. Linking semi-natural

grasslands and their future use to social aspects’’. Over the last

century there has been a substantial loss in the area of semi-

natural grasslands in Sweden as a consequence of widespread

land abandonment and a drastically diminishing number of

grazing animals. Therefore, science is required to find

strategies that ensure the persistence of this valuable

ecosystem. Stenseke suggests an interdisciplinary research

strategy, namely the application of a broad spectrum of

geographical methods which helps to bridge the gap between

social and natural science in natural resource management

research. Her call for flexible landscape policies allowing

adaptive management in various local contexts is an

important conclusion in the light of an often strongly

equalising European common agricultural policy.

Throughout the world Europe is noted for its art treasures,

monuments and also for its multifaceted and impressive

rural landscapes. Whereas the book market is inundated

with art-related tour guides, there is no comparable guide to

Europe’s cultural landscapes. This deficiency is the fulcrum

of

article ‘‘Recording rural land-

scapes and their cultural associations: some initial results

and impressions’’. Over a number of years the author has

compiled basic information for a Pan-European visual-

cultural guide to be used as a source of information for

planners, educators and the general public. More than

simply informing, it could potentially help to motivate

broader public support for endangered rural landscape types

such as bocage (hedgerows, enclosed fields), coltura promiscua

(central Italian mixed cropping) and dehesas/montados (oak

woodland supporting the Iberian hog–sheep–grain–cork

agroforestry system). Furthermore, Zimmermann charac-

terises the perceptions of local people in relation to land-

scape change and decline as determined from his study trips

through Europe and over the course of many informal

interviews.

Taking as an example the Causse Me´jan, one of the few

remaining open steppe habitats in France and the hilly,

profoundly ravined Valle´e Francaise in the Cevennes

National Park,

calls into question the

commonly held, traditional image of closed, autarchic

agrarian societies in upland communities, which was long

used to reinforce the equilibrium-centred model of human–

nature interdependencies. She argues that landscape

research should be geared toward conceptual models in

order to identify future perspectives for upland communities.

In contrast to the idealised notion of sustainability, as

suggested in equilibrium-based models, this approach repre-

sents a more useful theoretical platform based on an

awareness of the fact that in complex systems even small-

scale changes or random events may have notable repercus-

sions for the system as a whole. Against this background, the

author highlights the flexibility and resilience developed over

centuries by mountain communities in their daily struggle

with the environment. Her paper reveals these character-

istics as fundamental prerequisites for successful future

mountain landscape policies.

5.

Outlook

What is the future of high nature-value rural landscapes such as

traditional olive groves on Lesvos, the coltura promiscua in Italy,

the dehesas and montados on the Iberian Peninsula or Scandi-

navia’s semi-natural grasslands? Are they ‘‘exemplars’’ or

‘‘anachronisms’’ (

) in the modern landscape?

The collection of papers shows that land-use, and especially

agriculture, is the most important driving force that shapes

landscape sceneries. In agreement with the existing landscape

ecological literature the papers stress the considerable ecolo-

gical amenities that traditional low-intensity land-use delivers

to society. At the same time they show that cultural landscapes

have been in constant change, both in history and present. The

papers give a two-fold orientation: first, the integrity of the

remaining traditional land-use systems should be conserved,

and strategies need to be developed so that the ecological

services they provide are rewarded by society. We only can

preserve parts of traditional land-use systems well, after we

have a thorough insight into the complex interaction between

land-use and biodiversity. This leads to a plea for an

interdisciplinary historical–ecological approach in which ecol-

ogists and landscape historians closely cooperate. Moreover,

there is a need to link these ‘‘old-fashioned landscapes’’ with

new economic objectives, e.g. with rural tourism. Nevertheless,

it is neither feasible nor desirable to maintain traditional land-

use systems in their historical spatial extent (

).

Therefore, second, it will be necessary to determine the key

elements of traditional land-uses that provide ecological

services and to integrate these into future land-use systems.

Still, there are many potential trajectories of landscape

development, and particular landscapes will develop for each

specific societal and ecological setting.

predicted a complex mosaic of future landscapes, including

commodity-output oriented industrial landscapes, over-

stressed multifunctional landscapes, museum-like landscapes,

marginalised vanishing landscapes and wilderness landscapes.

One common insight of all authors in this issue is that a

sustainable landscape development is impossible without the

involvement of land-users and local people, i.e. of the sculptors

of the landscape. The papers give some hints for a fruitful

exchange between landscape research and the land-use

practice.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Peter Howard for proof-

reading all papers in this special issue.

r e f e r e n c e s

Baldock, D., Beaufoy, G., Clark, J., 1995. The Nature of Farming:

Low Intensity Farming Systems in Nine European

Countries. Institute for European Environmental Policy,

London.

Bignal, E.M., McCracken, D.I., 1996. Low-intensity farming

systems in the conservation of the countryside. J. Appl. Ecol.

33 (3), 413–424.

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 3 1 7 – 3 2 1

320

Bignal, E.M., McCracken, D.I., Corrie, H., 1995. Defining European

low-intensity farming systems: the nature of farming. In:

McCracken, D.I., Bignal, E.M., Wenlock, S.E. (Eds.), Farming on

the Edge: The Nature of Traditional Farmland in Europe. Joint

Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, pp. 29–37.

Carruthers, S.P., 1993. The dehesas of Spain—exemplars or

anachronisms? Agroforestry Forum 4 (2), 43–52.

Green, B.H., Vos, W., 2001. Managing old landscapes and making

new ones. In: Green, B.H., Vos, W. (Eds.), Threatened

Landscapes: Conserving Cultural Landscapes. Spon Press,

London, New York, NY, pp. 139–149.

Hampicke, U., 2006. Efficient conservation in Europe’s

agricultural countryside—rationale, methods and policy

reorientation. Outlook Agric. 35 (2), in press.

Heath, M.F., Tucker, G.M., 1995. Ornithological value and

pastoral farming systems. In: McCracken, D.I., Bignal, E.M.,

Wenlock, S.E. (Eds.), Farming on the Edge: The Nature of

Traditional Farmland in Europe. Joint Nature Conservation

Committee, Peterborough, pp. 54–59.

Herzog, F., 1997. Stand der agroforstlichen Forschung in West-

und Mitteleuropa. Z. Kulturtechnik Landentwicklung 38 (4),

145–148.

Ho¨chtl, F., Lehringer, S., Konold, W., 2005. ‘‘Wilderness’’: what it

means when it becomes a reality—a case study from the

southwestern Alps. Landscape Urban Plan. 70, 85–95.

Ho¨chtl, F., Lehringer, S., Konold, W. Pure theory or useful tool?

Experiences with transdisciplinarity in the Piedmont Alps.

Environ. Sci. Policy 9 (4), this issue

Kizos, T., Koulouri, M. Agricultural landscape dynamics in the

Mediterranean: Lesvos (Greece) case study using evidence

from the last three centuries. Environ. Sci. Policy 9 (4), this

issue.

Konold, W., Schwineko¨per, K., Seiffert, P., 1996. Zuku¨nftige

Kulturlandschaft aus der Tradition heraus. In: Konold, W.

(Ed.), Naturlandschaft—Kulturlandschaft. Die Vera¨nderung

der Landschaften nach der Nutzbarmachung durch den

Menschen. Ecomed, Landsberg, pp. 289–312.

Kristensen, S.P., 1999. Agricultural land and landscape changes

in Rostrup. Denmark: process of intensification and

extensification. Landscape Urban Plan. 46, 117–123.

MacDonald, D., Crabtree, J.R., Wiesinger, D., Dax, T., Stamou, N.,

Fleury, P., Gutierrez-Lazpita, J., Gibton, A., 2000. Agricultural

abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: environmental

consequences and policy response. J. Environ. Manage. 59

(1), 47–69.

Mitchell, N., Buggey, S., 2001. Protected landscapes and cultural

landscapes: taking advantage of diverse approaches. George

Wright Forum 17 (1), 35–46.

O’Rourke, E. Changes in agriculture and the environment in an

upland region of the Massif Central, France. Environ. Sci.

Policy 9 (4), this issue.

Olsson, E.G.A., Thorvaldsen, P. The eider conservation paradox

in Tautra—a new contribution to the multidimensionality

of the agricultural landscapes in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy

9 (4), this issue.

Palang, H., Helmfrid, S., Antrop, M., Aluma¨e, H., 2005. Rural

landscapes: past processes and future strategies. Landscape

Urban Plan. 70, 3–8.

Phillips, A., 1998. The nature of cultural landscapes—a nature

conservation perspective. Landscape Res. 23 (1), 21–38.

Stenseke, M. Biodiversity and the local context. Linking

seminatural grasslands and their future use to social

aspects. Environ. Sci. Policy 9 (4), this issue.

Tress, G., Tress, B., Fry, G., 2004. Clarifying integrative research

concepts in landscape ecology. Landscape Ecol. 20, 479–493.

Vos, W., Meekes, H., 1999. Trends in European cultural

landscape development: perspectives for a sustainable

future. Landscape Urban Plan. 46, 3–14.

Wilson, O.J., Wilson, G.A., 1997. Common cause or common

concern? The role of common lands in the post-productivist

countryside. Area 29 (1), 45–58.

Zimmermann, R.C. Recording rural landscapes and their

cultural associations: some initial results and impressions.

Environ. Sci. Policy 9 (4), this issue.

Tobias Plieninger studied forestry and environmental sciences

and completed his PhD degree at the University of Freiburg (Ger-

many) in 2004, specialising in landscape management. He is now a

research fellow at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences

and Humanities and investigates how the emergence of bioenergy

changes agriculture and forestry in rural areas. His research inter-

ests include rural development, land-use planning and landscape-

level conservation.

Franz Ho¨chtl, PhD, graduated in agricultural biology at the Uni-

versity of Stuttgart-Hohenheim (Germany) in 1997. Since 1998 he

has been working as a junior scientist at the University of Freiburg.

From 1999 to 2003 he was collaborating in two research projects

about landscape development strategies for alpine communities

in Piedmont (Italy). At present his work encompasses the analysis

of the social and ecological effects of forest expansion in south

Germany and the design of instruments for its control. Further-

more, he is the coordinator of a research project about the syner-

gies of monument and nature conservation in traditional

vineyards and historical parks.

Theo Spek is a senior researcher in landscape history and soil

science at the National Service for Archaeological Heritage Man-

agement in Amersfoort (the Netherlands), where he also leads an

interdisciplinary research programme at the interface between

heritage management and landscape studies. His research inter-

ests include landscape history of northwest Europe, anthropo-

genic soil formation and historical ecology. He is Secretary-

General of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of

the Rural Landscape (PECSRL).

e n v i r o n m e n t a l s c i e n c e & p o l i c y 9 ( 2 0 0 6 ) 3 1 7 – 3 2 1

321

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

INTERNET USE AND SOCIAL SUPPORT IN WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER

No Man's land Gender bias and social constructivism in the diagnosis of borderline personality disor

Compare and contrast literature of Whitman and Dickinson in terms of God, man and nature

Kwiek, Marek The University and the State in Europe The Uncertain Future of the Traditional Social

The Name and Nature of Translation Studies In James S Holmes

Kwiek, Marek The University and the State in a Global Age Renegotiating the Traditional Social Cont

Pye D Polarised light in science and nature (IOP)(133s)

Phillip Cary Inner Grace Augustine in the Traditions of Plato and Paul 2008

No Man s land Gender bias and social constructivism in the diagnosis of borderline personality disor

Ziyaeemehr, Kumar, Abdullah Use and Non use of Humor in Academic ESL Classrooms

Tsitsika i in (2009) Internet use and misuse a multivariate regresion analysis of the predictice fa

How to use format function built in U100version emulator and

the development and use of the eight precepts for lay practitioners, Upāsakas and Upāsikās in therav

The development and use of the eight precepts for lay practitioners, Upāsakas and Upāsikās in Therav

Functional Origins of Religious Concepts Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds

2008 4 JUL Emerging and Reemerging Viruses in Dogs and Cats

Angielski tematy Performance appraisal and its role in business 1

Kissoudi P Sport, Politics and International Relations in Twentieth Century

więcej podobnych podstron