Durand 11-1

11

Personality Disorders

[UNF.p.430-11 goes here]

An Overview of Personality Disorders

Aspects of Personality Disorders

Categorical and Dimensional Models

Personality Disorder Clusters

Statistics and Development

Gender Differences

Comorbidity

Personality Disorders Under Study

Cluster A Personality Disorders

Paranoid Personality Disorder

Schizoid Personality Disorder

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Cluster B Personality Disorders

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Borderline Personality Disorder

Histrionic Personality Disorder

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

Cluster C Personality Disorders

Avoidant Personality Disorder

Dependent Personality Disorder

Durand 11-2

Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

Visual Summary: Exploring Personality Disorders

Abnormal Psychology Live CD-ROM

Antisocial Personality Disorder: George

Borderline Personality Disorders

An Overview of Personality Disorders

Describe the essential features of personality disorders according to DSM-IV-

TR and why they are listed on Axis II.

According to DSM-IV-TR, personality disorders are “enduring patterns of

perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and oneself that are

exhibited in a wide range of social and personal contexts, . . . are inflexible and

maladaptive, and cause significant functional impairment or subjective distress” (p.

686) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a). Now that you have taken out your

yellow marker and highlighted this definition of personality disorders, what do you

think it means?

We all think we know what a “personality” is. It’s all the characteristic ways a

person behaves and thinks: “Michael tends to be shy”; “Mindy likes to be dramatic”;

“Juan is always suspicious of others”; “Annette is outgoing”; “Bruce seems to be

sensitive and gets upset easily over minor things”; “Sean has the personality of an

eggplant!” We tend to type people as behaving in one way in many different

situations. For example, like Michael, many of us are shy with people we don’t know,

but we won’t be shy around our friends. A truly shy person is shy even among people

Durand 11-3

he or she has known for some time. The shyness is part of the way the person behaves

in most situations. We have all probably behaved in all the ways noted here (dramatic,

suspicious, outgoing, easily upset). However, we usually consider a way of behaving

part of a person’s personality only if it occurs in many times and places. In this

chapter we look at characteristic ways of behaving in relation to personality disorders.

First we examine in some detail how we conceptualize personality disorders and the

issues related to them; then we describe the disorders themselves.

Aspects of Personality Disorders

What if a person’s characteristic ways of thinking and behaving cause significant

distress to the self or others? What if the person can’t change this way of relating to

the world and is unhappy? We might consider this person to have a personality

disorder. The DSM-IV-TR definition notes that these personality characteristics are

“inflexible and maladaptive, and cause significant functional impairment or subjective

distress.” Unlike many of the disorders we have already discussed, personality

disorders are chronic; they do not come and go but originate in childhood and

continue throughout adulthood. Because they affect personality, these chronic

problems pervade every aspect of a person’s life. If a man is overly suspicious, for

example (a sign of a possible paranoid personality disorder), this trait will affect

almost everything he does, including his employment (he may have to change jobs

frequently if he believes co-workers conspire against him), his relationships (he may

not be able to sustain a lasting relationship if he can’t trust anyone), and even where

he lives (he may have to move often if he suspects his landlord is out to get him).

DSM-IV-TR notes that having a personality disorder may distress the affected

person. However, individuals with personality disorders may not feel any subjective

distress; indeed, it may be acutely felt by others because of the actions of the person

Durand 11-4

with the disorder. This is particularly common with antisocial personality disorder,

because the individual may show a blatant disregard for the rights of others yet exhibit

no remorse (Meloy, 2001). In certain cases, someone other than the person with the

personality disorder must decide whether the disorder is causing significant functional

impairment, because the affected person often cannot make such a judgment.

DSM-IV-TR lists 10 specific personality disorders and several others that are

being studied for future consideration; we review them all. Although the prospects for

treatment success for people who have personality disorders may be more optimistic

than previously thought (Perry, Banon, & Ianni, 1999), unfortunately, as we see later,

many people who have personality disorders in addition to other psychological

problems tend to do poorly in treatment. Data from several studies show that people

who are depressed have a worse outcome in treatment if they also have a personality

disorder (Sanderson & Clarkin, 1994; Shea et al., 1990).

Most of the disorders we discuss in this book are in Axis I of DSM-IV-TR, which

includes the standard traditional disorders. The personality disorders are included in a

separate axis, Axis II, because as a group they are distinct. The characteristic traits are

more ingrained and inflexible in people who have personality disorders, and the

disorders themselves are less likely to be successfully modified.

personality disorders Enduring maladaptive patterns of relating to the

environment and oneself, exhibited in a wide range of contexts that cause

significant functional impairment or subjective distress.

Having personality disorders on a separate axis requires the clinician to consider

in each assessment whether the person has a personality disorder. In the axis system, a

patient can receive a diagnosis on only Axis I, only Axis II, or on both axes. A

Durand 11-5

diagnosis on both Axis I and Axis II indicates that a person has both a current disorder

(Axis I) and a more chronic problem (e.g., personality disorder). As you will see, it is

not unusual for one person to be diagnosed on both axes.

You may be surprised to learn that the category of personality disorders is

controversial, because it involves a number of unresolved issues. Examining these

issues can help us understand all the disorders described in this book.

Categorical and Dimensional Models

Most of us are sometimes suspicious of others and a little paranoid, overly dramatic,

too self-involved, or reclusive. Fortunately, these characteristics have not lasted too

long or been overly intense, and they haven’t significantly impaired how we live and

work. People with personality disorders, however, display problem characteristics

over extended periods and in many situations, which can cause great emotional pain

for themselves and/or others. Their difficulty, then, can be seen as one of degree

rather than kind; in other words, the problems of people with personality disorders

may just be extreme versions of the problems many of us experience on a temporary

basis, such as being shy or suspicious.

The distinction between problems of degree and problems of kind is usually

described in terms of dimensions instead of categories. The issue that continues to be

debated in the field is whether personality disorders are extreme versions of otherwise

normal personality variations (dimensions) or ways of relating that are different from

psychologically healthy behavior (categories) (Costa & Widiger, 1994; Gunderson,

1992; Livesley, Schroeder, Jackson, & Jang, 1994). We can see the difference

between dimensions and categories in everyday life. For example, we tend to look at

gender categorically. Our society views us as being in one category (female) or the

other (male). Yet we could also look at gender in terms of dimensions. For example,

Durand 11-6

we know that “maleness” and “femaleness” are in part determined by hormones. We

could identify people along testosterone and/or estrogen dimensions and rate them on

a continuum of maleness and femaleness rather than in the absolute categories of male

or female. We also often label people’s size categorically, as tall, medium, or short.

But height, too, can be viewed dimensionally, in inches or centimeters.

Most people in the field see personality disorders as extremes on one or more

personality dimensions. Yet because of the way people are diagnosed with the DSM,

the personality disorders—like most other disorders—end up being viewed in

categories. You have two choices—either you do (yes) or you do not (no) have a

disorder. For example, either you have antisocial personality disorder or you don’t.

The DSM doesn’t rate how dependent you are; if you meet the criteria, you are

labeled as having dependent personality disorder. There is no between when it comes

to personality disorders.

There are advantages to using categorical models of behavior, the most important

being their convenience. With simplification, however, come problems. One is that

the mere act of using categories leads clinicians to reify them; that is, to view

disorders as real “things,” comparable to the realness of an infection or a broken arm.

Some argue that personality disorders are not things that exist but points at which

society decides a particular way of relating to the world has become a problem. There

is the important unresolved issue again: Are personality disorders just an extreme

variant of normal personality, or are they distinctly different disorders?

Many researchers believe that many or all personality disorders represent

extremes on one or more personality dimensions. Consequently, some have proposed

that the DSM-IV-TR personality disorders section be replaced or at least

supplemented by a dimensional model (Widiger, 1991; Widiger & Frances, 1985) in

Durand 11-7

which individuals not only would be given categorical diagnoses but also would be

rated on a series of personality dimensions. Widiger (1991) believes such a system

would have at least three advantages over a purely categorical system: (1) It would

retain more information about each individual, (2) it would be more flexible because

it would permit both categorical and dimensional differentiations among individuals,

and (3) it would avoid the often arbitrary decisions involved in assigning a person to a

diagnostic category.

Although no general consensus exists about what the basic personality dimensions

might be, there are several contenders (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975; Tellegen, 1978;

Watson, Clark, & Harkness, 1994). One of the more widely accepted is called the

five-factor model, or the “Big Five,” and is taken from work on normal personality

(Costa & McCrae, 1990; Costa & Widiger, 1994; Goldberg, 1993; Tupes & Christal,

1992). In this model, people can be rated on a series of personality dimensions, and

the combination of five components describe why people are so different. The five

factors or dimensions are extraversion (talkative, assertive, and active versus silent,

passive, and reserved), agreeableness (kind, trusting, and warm versus hostile, selfish,

and mistrustful), conscientiousness (organized, thorough, and reliable versus careless,

negligent, and unreliable), emotional stability (even-tempered versus nervous, moody,

and temperamental), and openness to experience (imaginative, curious, and creative

versus shallow and imperceptive) (Goldberg, 1993). On each dimension, people are

rated high, low, or somewhere between.

Cross-cultural research establishes the universal nature of the five dimensions. In

German, Portuguese, Hebrew, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese samples, individuals

have personality trait structures similar to American samples (McCrae & Costa,

1997). A number of researchers are trying to determine whether people with

Durand 11-8

personality disorders can also be rated in a meaningful way along these dimensions

and whether the system will help us better understand these disorders (L. A. Clark,

1993; Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, Silva, & McGee, 1996; Schroeder, Wormworth, &

Livesley, 1993).

Personality Disorder Clusters

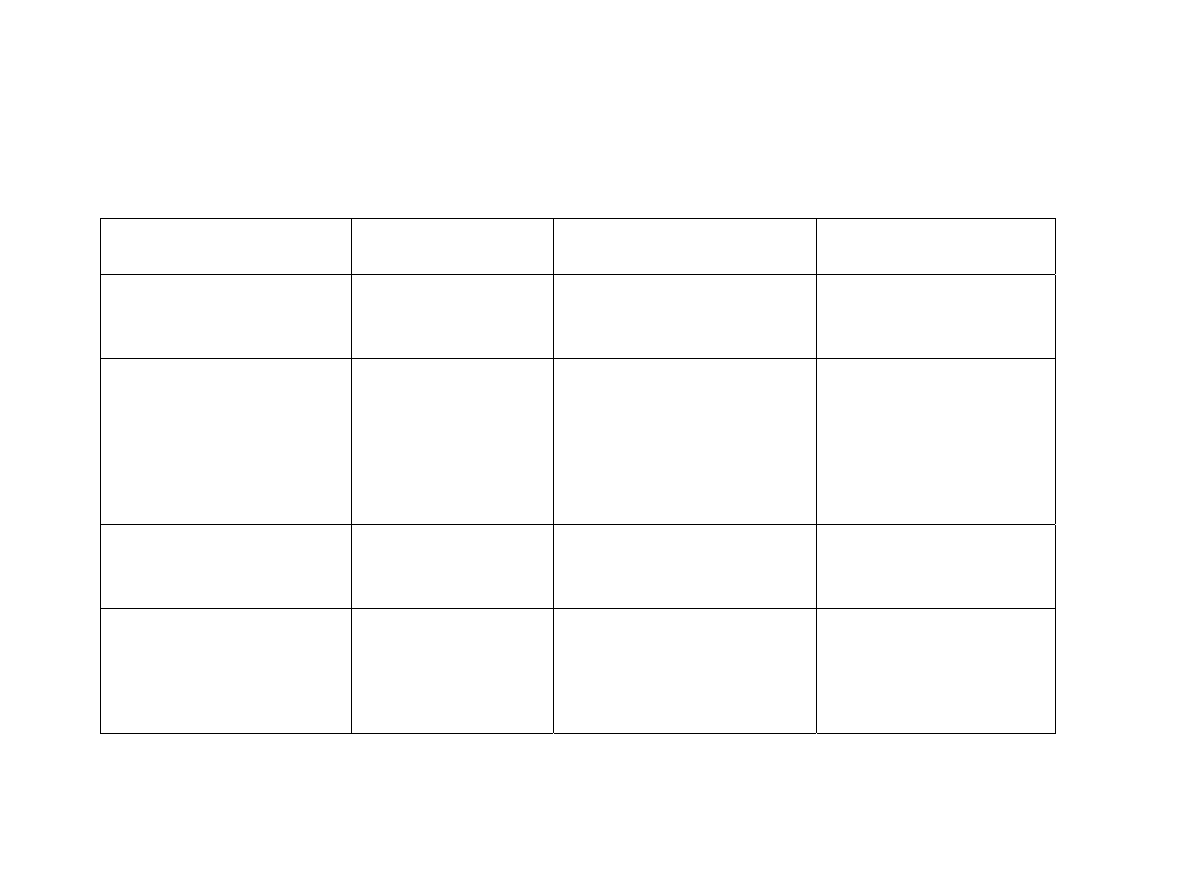

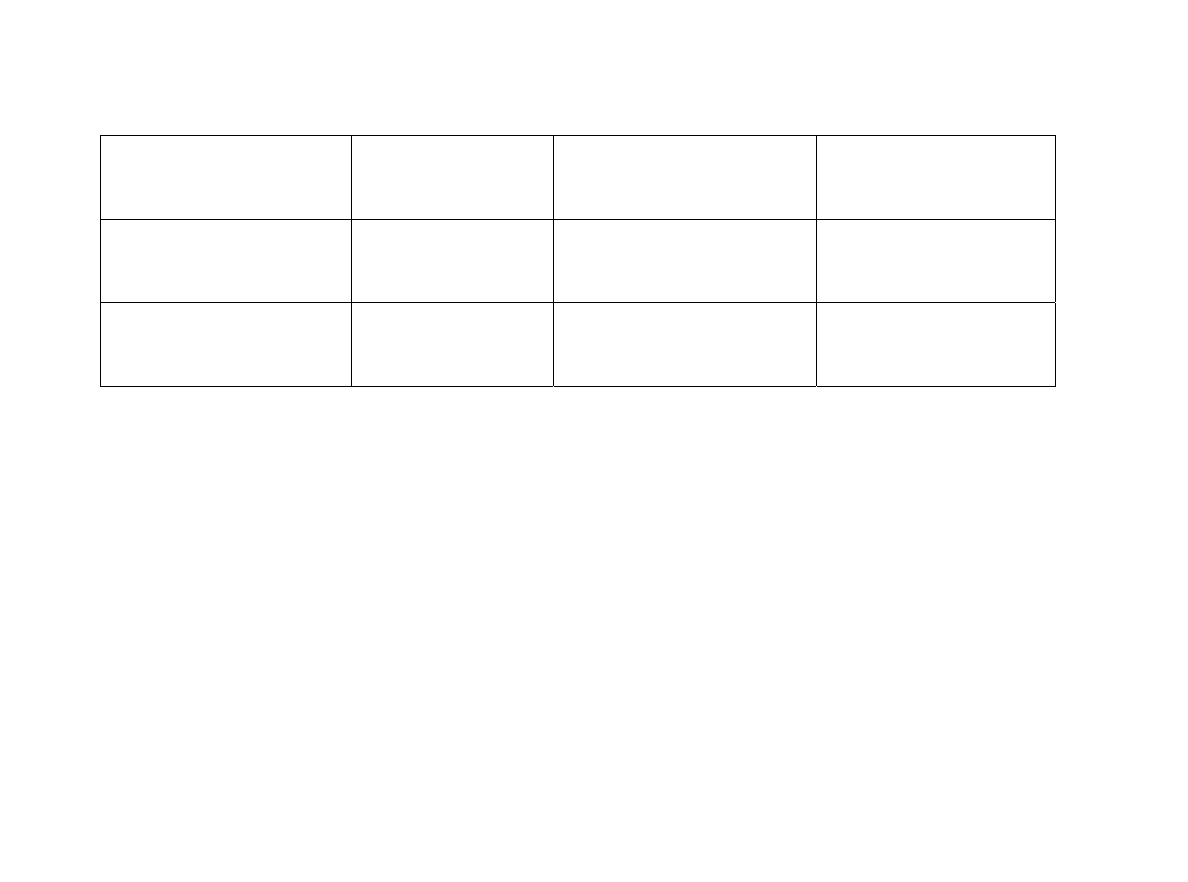

DSM-IV-TR divides the personality disorders into three groups, or clusters; this will

probably continue until a strong scientific basis is established for viewing them

differently (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a). The cluster division (see Table

11.1) is based on resemblance. Cluster A is called the odd or eccentric cluster; it

includes paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. Cluster B is the

dramatic, emotional, or erratic cluster; it consists of antisocial, borderline, histrionic,

and narcissistic personality disorders. Cluster C is the anxious or fearful cluster; it

includes avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. We

follow this order in our review.

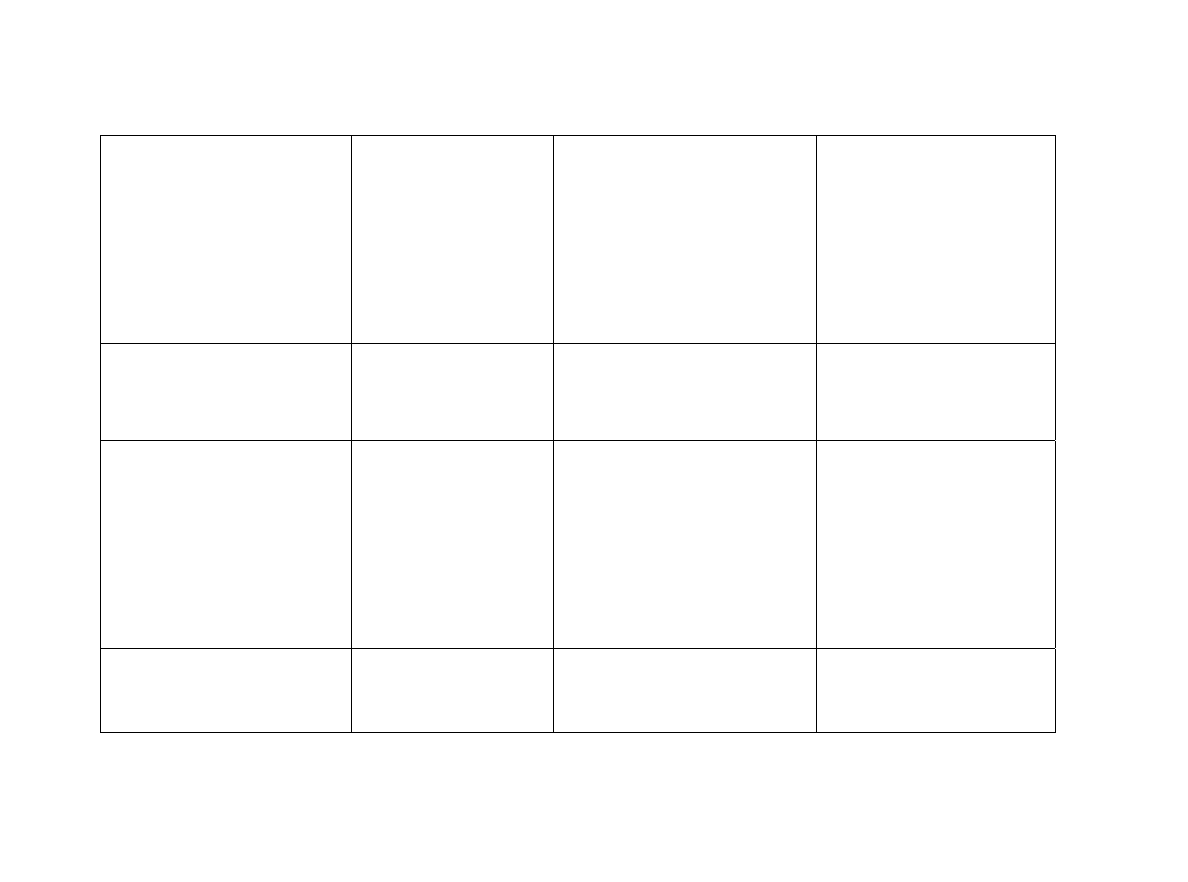

Statistics and Development

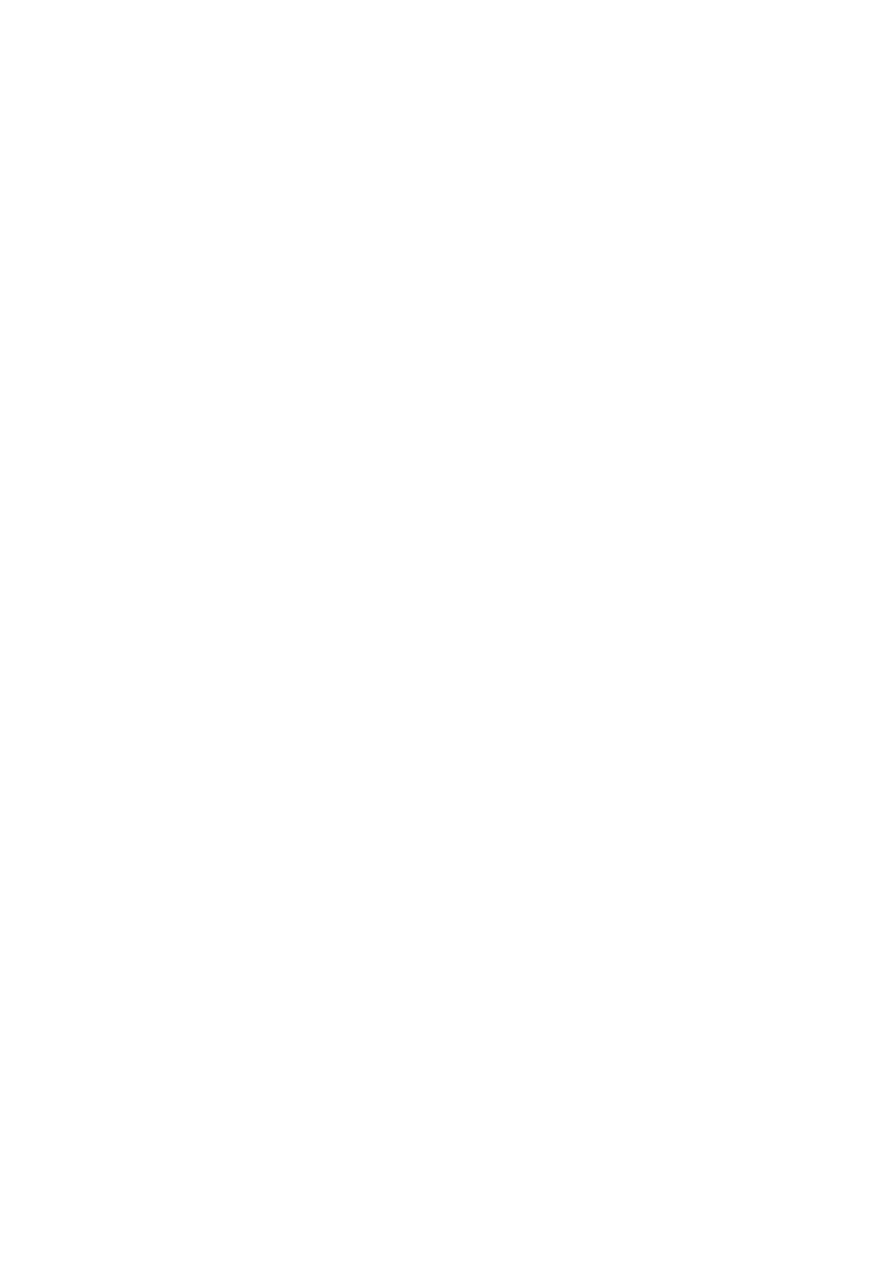

Personality disorders are found in 0.5% to 2.5% of the general population, 10% to

30% of all individuals served in inpatient settings, and in 2% to 10% of those

individuals in outpatient settings (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a), which

makes them relatively common. As you can see from Table 11.2, schizoid,

narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders are relatively rare, occurring in less

than 1% of the general population. Paranoid, schizotypal, histrionic, dependent, and

obsessive-compulsive personality disorders are found in 1% to 4% of the general

population.

Durand 11-9

Personality disorders are thought to originate in childhood and continue into the

adult years (Phillips, Yen, & Gunderson, 2003) and to be so ingrained that an onset is

difficult to pinpoint. Maladaptive personality characteristics develop over time into

the maladaptive behavior patterns that create distress for the affected person and draw

the attention of others. Our relative lack of information about such important features

of personality disorders as their developmental course is a repeating theme. The gaps

in our knowledge of the course of about half these disorders are visible in Table 11.2.

One reason for this dearth of research is that many individuals seek treatment not in

the early developmental phases of their disorder but only after years of distress. This

makes it difficult to study people with personality disorders from the beginning,

although a few research studies have helped us understand the development of several

disorders.

Durand 11-10

[Start Table 11.1]

TABLE 11.1 DSM-IV-TR Personality Disorders

Personality Disorder

Description

Cluster A—Odd or Eccentric Disorders

Paranoid personality disorder

A pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others such that their motives are

interpreted as malevolent.

Schizoid personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of detachment from social relationships and a restricted range

of expression of emotions in interpersonal settings.

Schizotypal personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of social and interpersonal deficits marked by acute

discomfort with reduced capacity for close relationships and by cognitive or

perceptual distortions and eccentricities of behavior.

Cluster B—Dramatic, Emotional, or Erratic Disorders

Antisocial personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others.

Durand 11-11

Antisocial personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image,

affects, and control over impulses.

Histrionic personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of excessive emotion and attention seeking.

Narcissistic personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of grandiosity (in fantasy or behavior), need for admiration,

and lack of empathy.

Cluster C—Anxious or Fearful Disorders

Avoidant personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of social inhibition, feelings of inadequacy, and

hypersensitivity to negative evaluation.

Dependent personality disorder

A pervasive and excessive need to be taken care of, which leads to submissive

and clinging behavior and fears of separation.

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

A pervasive pattern of preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental

and interpersonal control at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency.

Source: From Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Copyright © 2000 American

Psychiatric Association. Reprinted with permission.

Durand 11-12

[End Table 11.1]

Durand 11-13

People with borderline personality disorder are characterized by their volatile

and unstable relationships; they tend to have persistent problems in early adulthood,

with frequent hospitalizations, unstable personal relationships, severe depression,

and suicidal gestures. Approximately 6% succeed in their suicidal attempts (J. C.

Perry, 1993; M. H. Stone, 1989). On the bright side, their symptoms gradually

improve if they survive into their 30s (Dulit, Marin, & Frances, 1993), although

elderly individuals may have difficulty making plans and may be disruptive in

nursing homes (Rosowsky & Gurian, 1992). People with antisocial personality

disorder display a characteristic disregard for the rights and feelings of others; they

tend to continue their destructive behaviors of lying and manipulation through

adulthood. Fortunately, some tend to burn out after the age of 40 and engage in

fewer criminal activities (Hare, McPherson, & Forth, 1988). As a group, however,

the problems of people with personality disorders continue, as shown when

researchers follow their progress over the years (Phillips & Gunderson, 2000).

Gender Differences

Borderline personality disorder is diagnosed much more frequently in females, who

make up about 75% of the identified cases (Dulit et al., 1993) (see Table 11.2).

Historically, histrionic and dependent personality disorders were identified by

clinicians more often in women (Dulit et al., 1993; Stone, 1993), but according to

more recent studies of their prevalence in the general population, equal numbers of

males and females may have histrionic and dependent personality disorders

(American Psychiatric Association, 2000a, Lilienfeld, Van Valkenburg, Larntz, &

Akiskal, 1986; Nestadt et al., 1990; Reich, 1987). If this observation holds up in

Durand 11-14

future studies, why have these disorders been predominantly diagnosed among

females in general clinical practice and in other studies (Dulit et al., 1993)?

Durand 11-15

[Start Table 11.2]

TABLE 11.2 Statistics and Development of Personality Disorders

Disorder Prevalence

Gender

Differences

Course

Paranoid personality disorder

0.5% to 2.5% (Bernstein,

Useda, & Siever, 1993)

More common in males (O’Brien,

Trestman, & Siever, 1993)

Insufficient information

Schizoid personality disorder

Less than 1% in United

States, Canada, New

Zealand, Taiwan

(Weissman, 1993)

More common in males (O’Brien

et al., 1993)

Insufficient information

Schizotypal personality disorder 3% to 5% (Weissman,

1993)

More common in males (Kotsaftis

& Neale, 1993)

Chronic: some go on to de-

velop schizophrenia

Antisocial personality disorder

3% in males; less than

1% in females (Sutker,

Bugg, & West, 1993)

More common in males (Dulit,

Marin, & Frances, 1993)

Dissipates after age 40 (Hare,

McPherson, & Forth, 1988)

Durand 11-16

Borderline personality disorder

1% to 3% (Widiger &

Weissman, 1991)

Females make up 75% of cases

(Dulit et al., 1993)

Symptoms gradually improve

if individuals survive into

their 30s (Dulit et al., 1993).

Approximately 6% die by

suicide (Perry, 1993).

Histrionic personality disorder

2% (Nestadt et al., 1990)

Equal numbers of males and fe-

males (Nestadt et al., 1990)

Chronic

Narcissistic personality disorder Less than 1%

(Zimmerman &

Coryell, 1990)

More prevalent among men

May improve over time

(Cooper & Ronningstam,

1992; Gunderson,

Ronningstam, & Smith,

1991)

Avoidant personality disorder

Less than 1% (Reich,

Yates, & Nduaguba,

Equal numbers of males and fe-

males (Millon, 1986)

Insufficient information

Durand 11-17

1989; Zimmerman &

Coryell, 1990)

Dependent personality disorder

2% (Zimmerman &

Coryell, 1989)

May be equal numbers of male

and females (Reich, 1987)

Insufficient information

Obsessive-compulsive

personality disorder

4% (Weissman, 1993)

More common in males (Stone,

1993)

Insufficient information

[End Table 11.2]

Durand 11-18

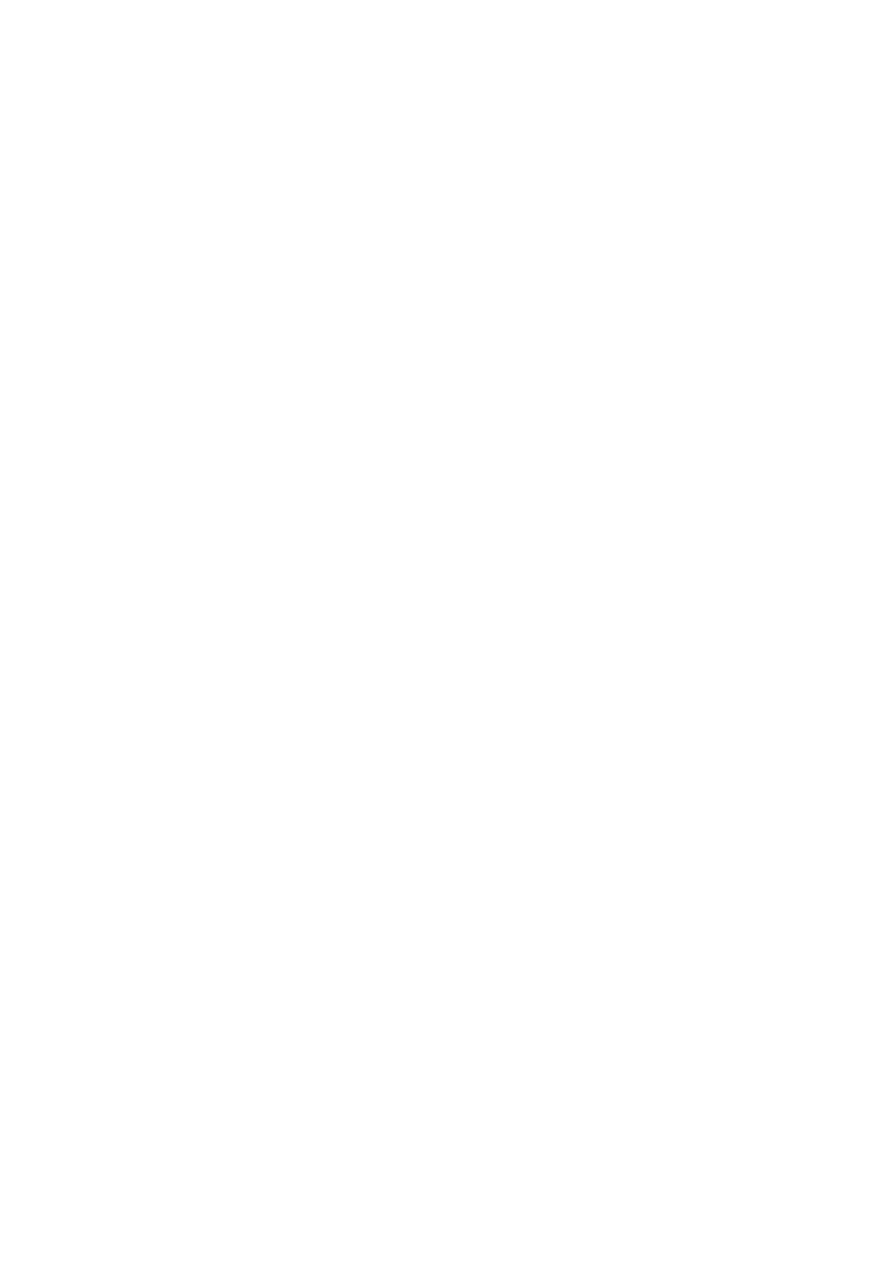

Do the disparities indicate differences between men and women in certain basic

genetic and/or sociocultural experience, or do they represent biases on the part of the

clinicians who make the diagnoses? Take, for example, a study by Maureen Ford and

Thomas Widiger (1989), who sent fictitious case histories to clinical psychologists for

diagnosis. One case described a person with antisocial personality disorder, which is

characterized by irresponsible and reckless behavior and usually diagnosed in males;

the other case described a person with histrionic personality disorder, which is

characterized by excessive emotionality and attention seeking and more often

diagnosed in females. The subject was identified as male in some versions of each

case and as female in others, although everything else was identical. As the graph in

Figure 11.1 shows, when the antisocial personality disorder case was labeled male,

most psychologists gave the correct diagnosis. However, when the same case was

labeled female, most psychologists diagnosed it as histrionic personality disorder

rather than antisocial personality disorder. In the case of histrionic personality

disorder, being labeled a woman increased the likelihood of that diagnosis. Ford and

Widiger (1989) concluded that the psychologists incorrectly diagnosed more women

as having histrionic personality disorder.

[Figure 11-1 goes here]

[UNF.p.435-11 goes here]

This gender difference in diagnosis has been criticized by other authors (e.g.,

Kaplan, 1983) on the grounds that histrionic personality disorder, like several of the

other personality disorders, is biased against females. As Kaplan (1983) points out,

many of the features of histrionic personality disorder, such as overdramatization,

vanity, seductiveness, and overconcern with physical appearance, are characteristic of

the Western stereotypical female. This disorder may simply be the embodiment of

Durand 11-19

extremely “feminine” traits (Chodoff, 1982); branding such an individual mentally ill,

according to Kaplan, reflects society’s inherent bias against females. Interestingly, the

“macho” personality (Mosher & Sirkin, 1984), in which the individual possesses

stereotypically masculine traits, is nowhere to be found in the DSM.

The issue of gender bias in diagnosing personality disorder remains highly

controversial. Remember, however, that just because certain disorders are observed

more in men or in women doesn’t necessarily indicate bias (Lilienfeld et al., 1986).

When it is pres-ent, bias can occur at different stages of the diagnostic process.

Widiger and Spitzer (1991) point out that the criteria for the disorder may themselves

be biased (criterion gender bias), or the assessment measures and the way they are

used may be biased (assessment gender bias). For example, Westen (1997) found that

although clinicians use the behaviors outlined in DSM-IV-TR for Axis I disorders, for

the personality disorders in Axis II they tend to use subjective impressions based on

their interpersonal interactions with the client. This may allow more bias, including

gender bias, to influence diagnoses of personality disorders. As research efforts

continue, we will try to make the diagnosis of personality disorders more accurate

with respect to gender and more useful to clinicians.

[UNF.p.436-11 goes here]

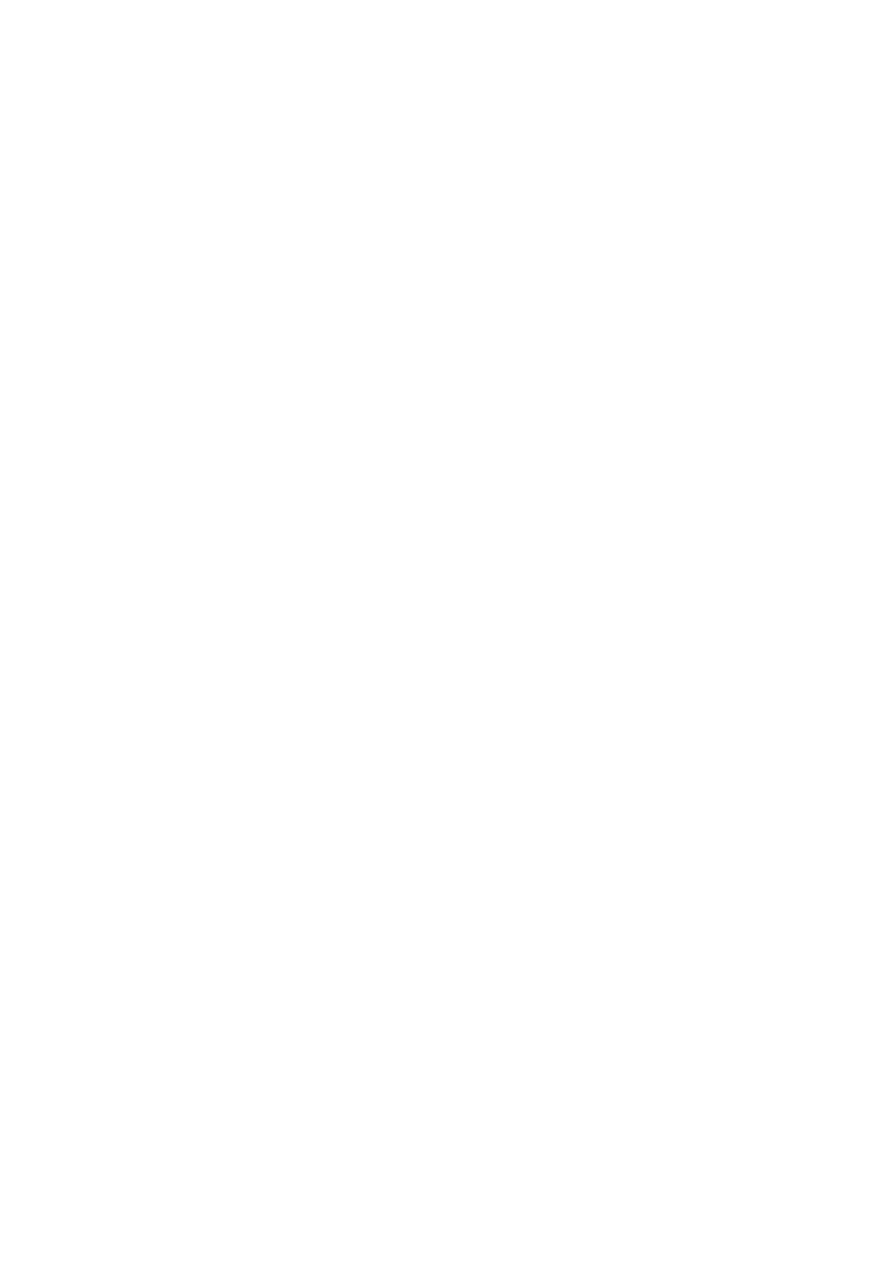

Comorbidity

Looking at Table 11.2 and adding up the prevalence rates across the personality

disorders, you might conclude that between 20% and 30% of all people are affected.

In fact, the percentage of people in the general population with a personality disorder

is estimated to be between 0.5% and 2.5% (American Psychiatric Association,

2000a). What accounts for this discrepancy? A major concern with the personality

disorders is that people tend to be diagnosed with more than one. The term

Durand 11-20

comorbidity historically describes the condition in which a person has multiple

diseases (Caron & Rutter, 1991). A fair amount of disagreement is ongoing about

whether the term should be used with psychological disorders because of the frequent

overlap of different disorders (e.g., Nurnberg et al., 1991). In just one example, Morey

(1988) conducted a study of 291 people who were diagnosed with personality disorder

and found considerable overlap (see Table 11.3). In the far left column is the primary

diagnosis, and across the table are the percentages of people who also meet the

criteria for other disorders. For example, a person identified with borderline

personality disorder also has a 32% likelihood of fitting the definition of another

supposedly different disorder—paranoid personality disorder (Grove & Tellegen,

1991).

Do people really tend to have more than one personality disorder? Are the ways

we define these disorders inaccurate, and do we need to improve our definitions so

that they do not overlap? Or did we divide the disorders in the wrong way to begin

with, and do we need to rethink the categories? Such questions about comorbidity are

just a few of the important issues faced by researchers who study personality

disorders.

Personality Disorders Under Study

Other personality disorders have been proposed for inclusion in the DSM—for

example, sadistic personality disorder, which includes people who receive pleasure by

inflicting pain on others (Fiester & Gay, 1995), and self-defeating personality

disorder, which includes people who are overly passive and accept the pain and

suffering imposed by others (Fiester, 1995). However, few studies supported the

existence of these disorders, so they were not included in DSM-IV-TR (Pfohl, 1993).

Durand 11-21

[Start Table 11.3]

TABLE 11.3 Diagnostic Overlap of Personality Disorders

Percentage of People Qualifying for Other Personality Disorder Diagnoses

Obsessive-

Diagnosis Paranoid Schizoid Schizotypal Antisocial Borderline Histrionic Narcissistic Avoidant Dependent compulsive

Paranoid 23.4 25.0

7.8 48.4 28.1 35.9 48.4 29.7 7.8

Schizoid

46.9 37.5 3.1 18.8 9.4 28.1 53.1 18.8 15.6

Schizotypal

59.3

44.4

3.7 33.3 18.5 33.3 59.3 29.6 11.1

Antisocial 27.8

5.6

5.6

44.4

33.3

55.6

16.7

11.1

0.0

Borderline 32.0

6.2

9.3

8.2

36.1

30.9

36.1

34.0

2.1

Histrionic 28.6

4.8

7.9

9.5

55.6

54.0

31.7

30.2

4.8

Narcissistic 35.9

14.1

14.1

15.6

46.9

53.1

35.9

26.6

10.9

Avoidant

39.2

21.5 20.3 3.8 44.3 25.3 29.1 40.5 16.5

Dependent

29.2 9.2 12.3

3.1 50.8 29.2 26.2 49.2

9.2

Durand 11-22

Obsessive-

21.7 21.7 13.0

0.0 8.7 13.0 30.4 56.5 26.1

compulsive

Source: “Personality disorders in DSM-III and DSM-III-R,” by Lesley C. Morey, 1988, American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 537–

577. Copyright © 1988 by the

[End Table 11.3]

Durand 11-23

Two new categories of personality disorder are under study. Depressive

personality disorder includes self-criticism, dejection, a judgmental stance toward

others, and a tendency to feel guilt. Some evidence indicates this may indeed be a

personality disorder distinct from dysthymic disorder (the mood disorder described in

Chapter 6 that involves a persistently depressed mood lasting at least 2 years);

research is continuing in this area (Phillips et al., 1998). Negativistic personality

disorder is characterized by passive aggression in which people adopt a negativistic

attitude to resist routine demands and expectations. This category may be a subtype of

a narcissistic personality disorder (Fossati et al., 2000). Neither depressive personality

disorder nor negativistic personality disorder has yet had enough research attention to

warrant inclusion as additional personality disorders in the DSM.

We now review the personality disorders currently in DSM-IV-TR, 10 in all, and

look briefly at a few categories being considered for inclusion.

Concept Check 11.1

Fill in the blanks to complete the following statements about personality disorders.

1. Unlike many disorders, personality disorders are _______; they originate in

childhood and continue throughout adulthood.

2. Personality disorders as a group are distinct and therefore placed on a separate

axis, _______.

3. It’s debated whether personality disorders are extreme versions of otherwise

normal personality variations (therefore classified as dimensions) or ways of

relating that are different from psychologically healthy behavior (classified as

_______).

Durand 11-24

4. Personality disorders are divided into three clusters or groups: _______

contains the odd or eccentric disorders; _______ the dramatic, emotional, and

_______ erratic disorders; and the anxious and fearfuldisorders.

5. Gender differences are evident in the research of personality disorders,

although some differences in the findings may be because of _______.

6. People with personality disorders are often diagnosed with other disorders, a

phenomenon called _______.

Cluster A Personality Disorders

Describe the essential characteristics of each of the Cluster A (odd/eccentric)

personality disorders, including information pertaining to etiology and

treatment.

Three personality disorders—paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal—share common

features that resemble some of the psychotic symptoms seen in schizophrenia. These

“odd” or “eccentric” personality disorders are described next.

Paranoid Personality Disorder

Although it is probably adaptive to be a little wary of other people and their motives,

being too distrustful can interfere with making friends, working with others, and, in

general, getting through daily interactions in a functional way. People with paranoid

personality disorder are excessively mistrustful and suspicious of others without

justification. They assume other people are out to harm or trick them; therefore, they

tend not to confide in others. Consider the case of Jake.

Jake

Durand 11-25

Research Victim

Jake grew up in a middle-class neighborhood, and although he never got in serious

trouble, he had a reputation in high school for arguing with teachers and

classmates. After high school he enrolled in the local community college, but he

flunked out after the first year. Jake’s lack of success in school was in part

attributable to his failure to take responsibility for his poor grades. He began to

develop conspiracy theories about fellow students and professors, believing they

worked together to see him fail. Jake bounced from job to job, each time

complaining that his employer was spying on him while at work and at home.

At age 25—and against his parents’ wishes—he moved out of his parents’

home to a small town out of state. Unfortunately, the letters Jake wrote home on a

daily basis confirmed his parents’ worst fears. He was becoming increasingly

preoccupied with theories about people who were out to harm him. Jake spent

enormous amounts of time on his computer exploring Web sites, and he

developed an elaborate theory about how research had been performed on him in

childhood. His letters home described his belief that researchers working with the

CIA drugged him as a child and implanted something in his ear that emitted

microwaves. These microwaves, he believed, were being used to cause him to

develop cancer. Over a period of 2 years he became increasingly preoccupied with

this theory, writing letters to various authorities trying to convince them he was

being slowly killed. After he threatened harm to some local college administrators,

his parents were contacted and they brought him to a psychologist, who diagnosed

him with paranoid personality disorder and major depression.

Durand 11-26

paranoid personality disorder Cluster A (odd or eccentric) personality disorder

involving pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others such that their motives

are interpreted as malevolent.

Clinical Description

The defining characteristic of people with paranoid personality disorder is a pervasive

unjustified distrust (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a). Certainly there may be

times when someone is deceitful and “out to get you”; however, people with paranoid

personality disorder are suspicious in situations where most other people would agree

their suspicions are unfounded. Even events that have nothing to do with them are

interpreted as personal attacks (Phillips & Gunderson, 2000). These people would

view a neighbor’s barking dog or a delayed airline flight as a deliberate attempt to

annoy them. Unfortunately, such mistrust often extends to people close to them and

makes meaningful relationships difficult. Imagine what a lonely existence this must

be! Suspiciousness and mistrust can show themselves in a number of ways. People

with paranoid personality disorder may be argumentative, may complain, or may be

quiet, but they are obviously hostile toward others. They often appear tense and are

“ready to pounce” when they think they’ve been slighted by someone. These

individuals are very sensitive to criticism and have an excessive need for autonomy

(Bernstein, Useda, & Siever, 1993).

Disorder Criteria Summary

Paranoid Personality Disorder

Features of paranoid personality disorder include:

• Pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others

• Suspicion that others are exploiting, harming, or deceiving the person

Durand 11-27

• Preoccupation with unjustified doubts about the loyalty of friends or associates

• Tendency to read hidden demeaning or threatening meanings into benign remarks

• Bearing persistent grudges over insults, injuries, or slights

• Person perceives attack on his or her character or reputation that are not apparent to

others

• Recurrent suspicions, without justification, regarding the fidelity of spouse or

sexual partner

• Does not occur exclusively with schizophrenia, a mood disorder with psychotic

features, or another psychotic disorder

Source: Based on DSM-IV-TR. Used with permission from the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Copyright

2000. American Psychiatric Association.

Causes

Evidence for biological contributions to paranoid personality disorder is limited.

Some research suggests the disorder may be slightly more common among the

relatives of people who have schizophrenia, although the association does not seem to

be strong (Bernstein et al., 1993; Coryell & Zimmerman, 1989; Kendler & Gruenberg,

1982). In other words, relatives of individuals with schizophrenia may be more likely

to have paranoid personality disorder than people who do not have a relative with

schizophrenia. As we see later with the other odd or eccentric personality disorders in

Cluster A, there seems to be some relationship with schizophrenia, although its exact

nature is not yet clear (Siever, 1992).

Psychological contributions to this disorder are even less certain, although some

interesting speculations have been made. Some psychologists point directly to the

Durand 11-28

thoughts of people with paranoid personality disorder as a way of explaining their

behavior. One view is that people with this disorder have the following basic mistaken

assumptions about others: “People are malevolent and deceptive,” “They’ll attack you

if they get the chance,” and “You can be OK only if you stay on your toes” (Freeman,

Pretzer, Fleming, & Simon, 1990). This is a maladaptive way to view the world, yet it

seems to pervade every aspect of the lives of these individuals. Although we don’t

know why they develop these perceptions, some speculation is that the roots are in

their early upbringing. Their parents may teach them to be careful about making

mistakes and to impress on them that they are different from other people (Turkat &

Maisto, 1985). This vigilance causes them to see signs that other people are deceptive

and malicious (Beck & Freeman, 1990). It is certainly true that people are not always

benevolent and sincere, and our interactions are sometimes ambiguous enough to

make other people’s intentions unclear. Looking too closely at what other people say

and do can sometimes lead you to misinterpret them.

Cultural factors have also been implicated in paranoid personality disorder.

Certain groups of people, such as prisoners, refugees, people with hearing

impairments, and the elderly, are thought to be particularly susceptible because of

their unique experiences (Christenson & Blazer, 1984; O’Brien, Trestman, & Siever,

1993). Imagine how you might view other people if you were an immigrant who had

difficulty with the language and the customs of your new culture. Such innocuous

things as other people laughing or talking quietly might be interpreted as somehow

directed at you.

We have seen how someone could misinterpret ambiguous situations as

malevolent. Therefore, cognitive and cultural factors may interact to produce the

suspiciousness observed in some people with paranoid personality disorder.

Durand 11-29

Treatment

Because people with paranoid personality disorder are mistrustful of everyone, they

are unlikely to seek professional help when they need it, and they have difficulty

developing the trusting relationships necessary for successful therapy (Phillips &

Gunderson, 2000). Establishing a meaningful therapeutic alliance between the client

and the therapist therefore becomes an important first step (Meissner, 2001). When

these individuals finally do seek therapy, the trigger is usually a crisis in their lives—

such as Jake’s threats to harm strangers—or other problems such as anxiety or

depression and not necessarily their personality disorder.

Therapists try to provide an atmosphere conducive to developing a sense of trust

(Freeman et al., 1990). They often use cognitive therapy to counter the person’s

mistaken assumptions about others, focusing on changing the person’s beliefs that all

people are malevolent and most people cannot be trusted (Tyrer & Davidson, 2000).

Be forewarned, however, that to date there are no confirmed demonstrations that any

form of treatment can significantly improve the lives of people with paranoid

personality disorder. A survey of mental health professionals indicated that only 11%

of therapists who treat paranoid personality disorder thought these individuals would

continue in therapy long enough to be helped (Quality Assurance Project, 1990).

[UNF.p.439-11 goes here]]

Schizoid Personality Disorder

Do you know someone who is a “loner”? Someone who would choose a solitary walk

over an invitation to a party? A person who comes to class alone, sits alone, and

leaves alone? Now, magnify this preference for isolation many times over and you

can begin to grasp the impact of schizoid personality disorder (Kalus, Bernstein, &

Durand 11-30

Siever, 1995). People with this personality disorder show a pattern of detachment

from social relationships and a limited range of emotions in interpersonal situations

(Phillips & Gunderson, 2000). They seem “aloof,” “cold,” and “indifferent” to other

people. The term schizoid is relatively old, having been used by Bleuler (1924) to

describe people who have a tendency to turn inward and from the outside world.

These people were said to lack emotional expressiveness and pursued vague interests.

Consider the case of Mr. Z.

schizoid personality disorder Cluster A (odd or eccentric) personality disorder

featuring a pervasive pattern of detachment from social relationships and a

restricted range of expression of emotions.

Mr. Z.

All on His Own

A 39-year-old scientist was referred after his return from a tour of duty in

Antarctica where he had stopped cooperating with others, withdrawn to his room,

and begun drinking on his own. Mr. Z. was orphaned at 4 years, raised by an aunt

until 9, and subsequently looked after by an aloof housekeeper. At university he

excelled at physics, but chess was his only contact with others. Throughout his

subsequent life he made no close friends and engaged primarily in solitary

activities. Until the tour of duty in Antarctica he had been quite successful in his

research work in physics. He was now, some months after his return, drinking at

least a bottle of Schnapps each day and his work had continued to deteriorate. He

presented as self-contained and unobtrusive, and he was difficult to engage

effectively. He was at a loss to explain his colleagues’ anger at his aloofness in

Antarctica and appeared indifferent to their opinion of him. He did not appear to

Durand 11-31

require any interpersonal relations, although he did complain of some tedium in

his life and at one point during the interview became sad, expressing longing to

see his uncle in Germany, his only living relation. (Cases and excerpts from

“Treatment Outlines for Paranoid, Schizotypal and Schizoid Personality

Disorders,” by the Quality Assurance Project, 1990, Australian and New Zealand

Journal of Psychiatry, 24, 339–350. Reprinted with permission of the Royal

Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.)

Clinical Description

Individuals with schizoid personality disorder seem neither to desire nor to enjoy

closeness with others, including romantic or sexual relationships. As a result they

appear cold and detached and do not seem affected by praise or criticism. One of the

changes in DSM-IV-TR from previous versions is the recognition that at least some

people with schizoid personality disorder are sensitive to the opinions of others but

are unwilling or unable to express this emotion. For them, social isolation may be

extremely painful. Unfortunately, homelessness appears to be prevalent among people

with this personality disorder, perhaps as a result of their lack of close friendships and

lack of dissatisfaction about not having a sexual relationship with another person

(Rouff, 2000).

Disorder Criteria Summary

Paranoid Personality Disorder

Features of schizoid personality disorder include:

• Pervasive pattern of detachment from social relationships and a restricted range of

expression of emotions, beginning by early adulthood

Durand 11-32

• Lack of desire for or enjoyment of close relationships, including family

relationships

• Almost always chooses solitary activities

• Little if any interest in sexual experiences with another person

• Takes pleasure in few, if any, activities

• Lacks close friends or confidantes other than first-degree relatives

• Appears indifferent to praise or criticism from others

• Shows emotional coldness or detachment

• Does not occur exclusively with schizophrenia or another disorder

Source: Based on DSM-IV-TR. Used with permission from the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Copyright

2000. American Psychiatric Association.

The social deficiencies of people with schizoid personality disorder are similar to

those of people with paranoid personality disorder, although they are more extreme.

As Beck and Freeman (1990) put it, they “consider themselves to be observers rather

than participants in the world around them” (p. 125). They do not seem to have the

unusual thought processes that characterize the other disorders in Cluster A (Kalus,

Bernstein, & Siever, 1993) (see Table 11.4). For example, people with paranoid and

schizotypal personality disorders often have ideas of reference, mistaken beliefs that

meaningless events relate just to them. In contrast, those with schizoid personality

disorder share the social isolation, poor rapport, and constricted affect (showing

neither positive nor negative emotion) seen in people with paranoid personality

disorder. We see in Chapter 12 that this distinction among psychotic-like symptoms is

important to understanding people with schizophrenia, some of whom show the

“positive” symptoms (actively unusual behaviors such as ideas of reference) and

Durand 11-33

others only the “negative” symptoms (the more passive manifestations of social

isolation or poor rapport with others).

[Start Table 11.4]

TABLE 11.4 Grouping Schema for Cluster A Disorders

Psychotic-like

Symptoms

“Positive”

“Negative”

(e.g., ideas of

(e.g., social

reference, magical

isolation, poor

Cluster A

thinking, and

rapport, and

Personality perceptual

constricted

Disorder distortions) affect)

Paranoid Yes

Yes

Schizoid No

Yes

Schizotypal Yes

No

Source: Adapted from “Schizophrenia Spectrum Personality Disorders,” by L. J.

Siever, in Review of Psychiatry, Vol. 11, A. Tasman and M. B. Riba (eds.), 1992 pp.

25–42. Copyright © 1992, the American Psychiatric Press.

[End Table 11.4]

Causes and Treatment

Research on the genetic, neurobiological, and psychosocial contributions to schizoid

personality disorder remains to be conducted (Phillips et al. 2003). Childhood shyness

is reported as a precursor to later adult schizoid personality disorder. It may be that

this personality trait is inherited and serves as an important determinant in the

development of this disorder. Research over the past several decades has pointed to

Durand 11-34

biological causes of autism, and it is possible that a similar biological dysfunction

combines with early learning or early problems with interpersonal relationships to

produce the social deficits that define schizoid personality disorder (Wolff, 2000). For

example, research on the neurochemical dopamine suggests that people with a lower

density of dopamine receptors scored higher on a measure of “detachment” (Farde,

Gustavsson, & Jonsson, 1997). It may be that dopamine (which seems to be involved

with schizophrenia as well) may contribute to the social aloofness of people with

schizoid personality disorder.

It is rare for a person with this disorder to request treatment except in response to

a crisis such as extreme depression or losing a job (Kalus et al., 1995). Therapists

often begin treatment by pointing out the value in social relationships. The person

with the disorder may even need to be taught the emotions felt by others to learn

empathy (Beck & Freeman, 1990). Because their social skills were never established

or have atrophied through lack of use, people with schizoid personality disorder often

receive social skills training. The therapist takes the part of a friend or significant

other in a technique known as role playing and helps the patient practice establishing

and maintaining social relationships (Beck & Freeman, 1990). This type of social

skills training is helped by identifying a social network—a person or people who will

be supportive (Stone, 2001). Outcome research on this type of approach is

unfortunately quite limited, so we must be cautious in evaluating the effectiveness of

treatment for people with schizoid personality disorder.

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

People with schizotypal personality disorder are typically socially isolated, like

those with schizoid personality disorder. In addition, they behave in ways that would

seem unusual to many of us (Siever, Bernstein, & Silverman, 1995), and they tend to

Durand 11-35

be suspicious and to have odd beliefs (Kotsaftis & Neale, 1993). Consider the case of

Mr. S.

Mr. S.

Man with a Mission

Mr. S. was a 35-year-old chronically unemployed man who had been referred by a

physician because of a vitamin deficiency. This was thought to have eventuated

because Mr. S. avoided any foods that “could have been contaminated by

machine.” He had begun to develop alternative ideas about diet in his 20s, and he

soon lefthis family and began to study an eastern religion. “It opened my third

eye; corruption is all about,” he said.

He now lived by himself on a small farm, attempting to grow his own food

and bartering for items he could not grow himself. He spent his days and evenings

researching the origins and mechanisms of food contamination and, because of

this knowledge, had developed a small band who followed his ideas. He had never

married and maintained little contact with his family: “I’ve never been close to my

father. I’m a vegetarian.”

He said he intended to do a herbalism course to improve his diet before

returning to his life on the farm. He had refused medication from the physician

and became uneasy when the facts of his deficiency were discussed with him.

(Cases and excerpts from “Treatment Outlines for Paranoid, Schizotypal and

Schizoid Personality Disorders,” by the Quality Assurance Project, 1990,

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 24, 339–350. Reprinted with

permission of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.)

Durand 11-36

schizotypal personality disorder Cluster A (odd or eccentric) personality

disorder involving a pervasive pattern of interpersonal deficits featuring acute

discomfort with, and reduced capacity for, close relationships, as well as by

cognitive or perceptual distortions and eccentricities of behavior.

Clinical Description

People given a diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder are often considered

“odd” or “bizarre” because of how they relate to other people, how they think and

behave, and even how they dress. They have ideas of reference, which means they

think insignificant events relate directly to them. For example, they may believe that

somehow everyone on a passing city bus is talking about them, yet they may be able

to acknowledge this is unlikely. Again, as we see in Chapter 12, some people with

schizophrenia also have ideas of reference, but they are usually not able to “test

reality” or see the illogic of their ideas.

Individuals with schizotypal personality disorder also have odd beliefs or engage

in “magical thinking,” believing, for example, that they are clairvoyant or telepathic.

In addition, they report unusual perceptual experiences, including such illusions as

feeling the presence of another person when they are alone. Notice the subtle but

important difference between the feeling that someone else is in the room and the

more extreme perceptual distortion in people with schizophrenia who might report

there is someone else in the room when there isn’t. Only a small proportion of

individuals with schizotypal personality disorder go on to develop schizophrenia

(Wolff, Townshed, McGuire, & Weeks, 1991). Unlike people who simply have

unusual interests or beliefs, those with schizotypal personality disorder tend to be

suspicious and have paranoid thoughts, express little emotion, and may dress or

behave in unusual ways (e.g., wear many layers of clothing in the summertime or

Durand 11-37

mumble to themselves) (Siever, Bernstein, & Silverman, 1991). Prospective research

on children who later develop schizotypal personality disorder found that they tend to

be passive and unengaged and are hypersensitive to criticism (Olin et al., 1997).

Disorder Criteria Summary

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Features of schizotypal personality disorder include:

• Pervasive pattern of social and interpersonal deficits marked by acute discomfort

with close relationships, cognitive (or perceptual) distortions, and eccentricities of

behavior, beginning by early adulthood

• Incorrect interpretations of casual incidents and external events as having a

particular or unusual meaning specifically for the person

• Odd beliefs or magical thinking that influences behavior and is inconsistent with

subcultural norms

• Unusual perceptual experiences, including bodily illusions

• Odd thinking and speech (e.g., vague, overelaborate, stereotyped)

• Suspiciousness or paranoid ideation

• Inappropriate or constricted affect

• Behavior or appearance that is odd, eccentric, orpeculiar

• Lack of close friends or confidantes other than first-degree relatives

• Excessive social anxiety associated with paranoid fears rather than negative

judgments about self

• Does not occur exclusively with schizophrenia or another disorder

Source: Based on DSM-IV-TR. Used with permission from the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Copyright

2000. American Psychiatric Association.

Durand 11-38

Clinicians have to be warned that different cultural beliefs or practices may lead to

a mistaken diagnosis of schizotypal personality disorder. For example, some people

who practice certain religious rituals—such as speaking in tongues, practicing

voodoo, or mind reading—may do so with such obsessiveness as to make them seem

extremely unusual, thus leading to a misdiagnosis (American Psychiatric Association,

2000a). Mental health workers have to be particularly sensitive to cultural practices

that may differ from their own and can distort their view of certain seemingly unusual

behaviors.

Causes

Historically, the word schizotype was used to describe people who were predisposed

to develop schizophrenia (Meehl, 1962; Rado, 1962). Schizotypal personality disorder

is viewed by some to be one phenotype of a schizophrenia genotype. Recall that a

phenotype is one way a person’s genetics is expressed. Your genotype is the gene or

genes that make up a particular disorder. However, depending on a variety of other

influences, the way you turn out, your phenotype, may vary from other people with a

similar genetic makeup. Some people are thought to have “schizophrenia genes” (the

genotype) and yet, because of the relative lack of biological influences (e.g., prenatal

illnesses) or environmental stresses (e.g., poverty), some will have the less severe

schizotypal personality disorder (the phenotype).

The idea of a relationship between schizotypal personality disorder and

schizophrenia arises in part from the way people with the disorders behave. Many

characteristics of schizotypal personality disorder, including ideas of reference,

illusions, and paranoid thinking, are similar but milder forms of behaviors observed

among people with schizophrenia. Genetic research also seems to support a

relationship. Family, twin, and adoption studies have shown an increased prevalence

Durand 11-39

of schizotypal personality disorder among relatives of people with schizophrenia who

do not also have schizophrenia themselves (Dahl, 1993; Torgersen, Onstad, Skre,

Edvardsen, & Kringlen, 1993). However, these studies also tell us that the

environment can strongly influence schizotypal personality disorder. For example,

some research suggests a woman’s exposure to influenza in pregnancy may increase

the chance of schizotypal personality disorder in her children (Venables, 1996). It

may be that a subgroup of people with schizotypal personality disorder has a similar

genetic makeup when compared with people with schizophrenia.

Biological theories of schizotypal personality disorder are receiving empirical

support. For example, cognitive assessment of people with this disorder point to mild

to moderate decrements in their ability to perform on tests involving memory and

learning, suggesting some damage in the left hemisphere (Voglmaier et al., 2000).

Other research using magnetic resonance imaging points to generalized brain

abnormalities in this group (Dickey et al., 2000).

Treatment

Some estimate that between 30% and 50% of the people with this disorder who

request clinical help also meet the criteria for major depressive disorder. Treatment

will obviously include some of the medical and psychological treatments for

depression (Goldberg, Schultz, Resnick, Hamer, & Schultz, 1987; Stone, 2001).

Controlled studies of attempts to treat groups of people with schizotypal

personality disorder are few, and, unfortunately, the results are modest at best. One

general approach has been to teach social skills to help them reduce their isolation

from and suspicion of others (Bellack & Hersen, 1985; O’Brien et al., 1993; Stone,

2001). A rather unusual tactic used by some therapists is not to encourage major

Durand 11-40

changes; instead, the goal is to help the person accept and adjust to a solitary lifestyle

(M. Stone, 1983).

Not surprisingly, medical treatment has been similar to that for people who have

schizophrenia. In one study, haloperidol, often used with schizophrenia, was given to

17 people with schizotypal personality disorder (Hymowitz, Frances, Jacobsberg,

Sickles, & Hoyt, 1986). There were some improvements in the group, especially with

ideas of reference, odd communication, and social isolation. Unfortunately, because

of the negative side effects of the medication, including drowsiness, many stopped

taking their medication and dropped out of the study. About half the subjects

persevered through treatment but showed only mild improvement.

Further research on the treatment of people with this disorder is important for a

variety of reasons. They tend not to improve over time, and some evidence indicates

that some will go on to develop the more severe characteristics of schizophrenia.

Concept Check 11.2

Which personality disorders are described below?

1. Carlos, who seems eccentric, never shows much emotion. He has always

sought solitary activities in school and at home. He has no close friends. At

birthday parties during his adolescence, he would take his gifts to a corner to

play. Carlos appears indifferent to what others say, has never had a girlfriend,

and expresses no desire to have sex. He is meeting with a therapist only

because his family tricked him into going. _______

2. Paul trusts no one and incorrectly believes other people want to harm him or

cheat him out of his life earnings. He is sure his wife is having an affair

although he has no proof. He no longer confides in friends or divulges any

Durand 11-41

information to coworkers for fear that it will be used against him. He dwells

for hours on harmless comments by family members. _______

3. Alison lives alone out in the country and has little contact with relatives or any

other individuals in a nearby town. She is extremely concerned with pollution,

fearing that harmful chemicals are in the air and water around her. If it is

necessary for her to go outside, she covers her body with excessive clothing

and wears a face mask to avoid the contaminated air. She has developed her

own water purification system and makes her own clothes. _______

Cluster B Personality Disorders

Describe the essential characteristics of each of the Cluster B

(dramatic/erratic) personality disorders.

Identify the differences between psychopathy and antisocial personality

disorder.

People diagnosed with the next four personality disorders we highlight—antisocial,

borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic—all have behaviors that have been described as

“dramatic,” “emotional,” or “erratic.” These personality disorders with exaggerated

presentations are described next.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

People with antisocial personality disorder are among the most dramatic of the

individuals a clinician will see in a practice and are characterized as having a history

of failing to comply with social norms. They perform actions most of us would find

unacceptable, such as stealing from friends and family. They also tend to be

irresponsible, impulsive, and deceitful (Widiger & Corbitt, 1995). Robert Hare

Durand 11-42

describes them as “social predators who charm, manipulate, and ruthlessly plow their

way through life, leaving a broad trail of broken hearts, shattered expectations, and

empty wallets. Completely lacking in conscience and empathy, they selfishly take

what they want and do as they please, violating social norms and expectations without

the slightest sense of guilt or regret” (Hare, 1993, p. xi). Just who are these people

with antisocial personality disorder? Consider the case of Ryan.

Ryan

The Thrill Seeker

I first met Ryan on his 17th birthday. Unfortunately, he was celebrating the event

in a psychiatric hospital. He had been truant from school for several months and

had gotten into some trouble; the local judge who heard his case had

recommended psychiatric evaluation one more time, though Ryan had been

hospitalized six previous times, all for problems related to drug use and truancy.

He was a veteran of the system and already knew most of the staff. I interviewed

him to assess why he was admitted this time and to recommend treatment.

My first impression was that Ryan was cooperative and pleasant. He pointed

out a tattoo on his arm that he had made himself, saying that it was a “stupid”

thing to have done and that he now regretted it. In fact, he regretted many things

and was looking forward to moving on with his life. I later found out that he was

never truly remorseful for anything.

Our second interview was quite different. During those 48 hours, Ryan had

done a number of things that showed why he needed a great deal of help. The

most serious incident involved a 15-year-old girl named Ann who attended class

with Ryan in the hospital school. Ryan had told her that he was going to get

himself discharged, get in trouble, and be sent to the same prison Ann’s father was

Durand 11-43

in, where he would rape her father. Ryan’s threat so upset Ann that she hit her

teacher and several of the staff. When I spoke to Ryan about this, he smiled

slightly and said he was bored and that it was fun to upset Ann. When I asked

whether it bothered him that his behavior might extend her stay in the hospital, he

looked puzzled and said, “Why should it bother me? She’s the one who’ll have to

stay in this hell hole!”

Just before Ryan’s admittance, a teenager in his town was murdered. A group

of teens went to the local cemetery at night to perform satanic rituals, and a young

man was stabbed to death, apparently over a drug purchase. Ryan was in the

group, although he did not stab the boy. He told me that they occasionally dug up

graves to get skulls for their parties; not because they really believed in the devil,

but because it was fun and it scared the younger kids. I asked, “What if this were

the grave of someone you knew, a relative or a friend? Would it bother you that

strangers were digging up the remains?” He shook his head. “They’re dead, man;

they don’t care. Why should I?”

Ryan told me he loved PCP, or “angel dust,” and that he would rather be

dusted than anything else. He routinely made the 2-hour trip to New York City to

buy drugs in a particularly dangerous neighborhood. He denied that he was ever

nervous. This wasn’t machismo; he really seemed unconcerned.

Ryan made little progress. I discussed his future in family therapy sessions,

and we talked about his pattern of showing supposed regret and remorse and then

stealing money from his parents and going back onto the street. In fact, most of

our discussions centered on trying to give his parents the courage to say no to him

and not to believe his lies.

Durand 11-44

One evening, after many sessions, Ryan said he had seen the “error of his

ways” and that he felt bad he had hurt his parents. If they would only take him

home this one last time, he would be the son he should have been all these years.

His speech moved his parents to tears, and they looked at me gratefully as if to

thank me for curing their son. When Ryan finished talking, I smiled, applauded,

told him it was the best performance I had ever seen. His parents turned on me in

anger. Ryan paused for a second, then he too smiled and said, “It was worth a

shot!” Ryan’s parents were astounded that he had once again tricked them into

believing him; he hadn’t meant a word of what he had just said. Ryan was

eventually discharged to a drug rehabilitation program. Within 4 weeks, he had

convinced his parents to take him home, and within 2 days he had stolen all their

cash and disappeared; he apparently went back to his friends and to drugs.

When he was in his 20s, after one of his many arrests for theft, he was

diagnosed as having antisocial personality disorder. His parents never summoned

the courage to turn him out or refuse him money, and he continues to con them

into providing him with a means of buying more drugs.

Clinical Description

Individuals with antisocial personality disorder tend to have long histories of violating

the rights of others (Widiger & Corbitt, 1995). They are often described as being

aggressive because they take what they want, indifferent to the concerns of other

people. Lying and cheating seem to be second nature to them, and often they appear

unable to tell the difference between the truth and the lies they make up to further

their own goals. They show no remorse or concern over the sometimes devastating

effects of their actions. Substance abuse is common, occurring in 83% of people with

Durand 11-45

antisocial personality disorder (Dulit et al., 1993; S. S. Smith & Newman, 1990), and

appears to be a lifelong pattern among these individuals (Skodol, Oldham, &

Gallaher, 1999). The long-term outcome for people with antisocial personality

disorder is often poor, regardless of gender (Pajer, 1998). One study, for example,

followed 1,000 delinquent and nondelinquent boys over a 50-year period (Laub &

Vaillant, 2000). Many of the delinquent boys would today receive a diagnosis of

conduct disorder, which we see later may be a precursor to antisocial personality

disorder in adults. The delinquent boys were more than twice as likely to die an

unnatural death (e.g., accident, suicide, homicide) as their nondelinquent peers, which

may be attributed to factors such as alcohol abuse and poor self-care (e.g., infections,

reckless behavior).

Disorder Criteria Summary

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Features of antisocial personality disorder include:

• Person at least 18 years of age who has shown a pervasive pattern of disregard for

and violation of the rights of others since age 15

• Failure to conform to social norms, as evidenced by repeatedly breaking the law

• Deceitfulness, including lying, using aliases, or conning others for profit or

pleasure

• Impulsivity or failure to plan ahead

• Irritability or aggressiveness, as indicated by frequent fights or assaults

• Reckless disregard for safety of others

• Consistent irresponsibility with employment or paying bills

• Lack of remorse at harming others

• Evidence of conduct disorder with onset before age 15

Durand 11-46

• Does not occur exclusively during the course of schizo-phrenia or a manic episode

Source: Based on DSM-IV-TR. Used with permission from the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Copyright

2000. American Psychiatric Association.

Antisocial personality disorder has had a number of names over the years.

Philippe Pinel (1801/1962) identified what he called manie sans délire (mania without

delirium) to describe people with unusual emotional responses and impulsive rages

but no deficits in reasoning ability (Sutker, Bugg, & West, 1993). Other labels have

included “moral insanity,” “egopathy,” “sociopathy,” and “psychopathy.” A great

deal has been written about these labels; we focus on the two that have figured most

prominently in psychological research: psychopathy and DSM-IV-TR’s antisocial

personality disorder. As you will see, there are important differences between the two.

Defining Criteria Hervey Cleckley (1941/1982), a psychiatrist who spent much of

his career working with the “psychopathic personality,” identified a constellation of

16 major characteristics, most of which are personality traits and are sometimes

referred to as the Cleckley criteria. They include superficial charm and good

intelligence; absence of delusions and other signs of irrational thinking; absence of

“nervousness” and other psychoneurotic manifestations; unreliability; untruthfulness

and insincerity; lack of remorse or shame; inadequately motivated antisocial behavior;

poor judgment and failure to learn by experience; pathologic egocentricity and

incapacity for love; general poverty in major affective reactions; specific loss of

insight; unresponsiveness in general interpersonal relations; fantastic and uninviting

behavior, with drink and without; suicide rarely carried out; sex life impersonal,

Durand 11-47

trivial, and poorly integrated; and failure to follow any life plan (Cleckley, 1982, p.

204).

antisocial personality disorder Cluster B (dramatic, emotional, or erratic)

personality disorder involving a pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of

the rights of others. Similar to the non-DSM label psychopathy but with greater

emphasis on overt behavior rather than personality traits.

Robert Hare and his colleagues, building on the descriptive work of Cleckley,

researched the nature of psychopathy (e.g., Hare, 1970; Harpur, Hare, & Hakstian,

1989) and developed a 20-item checklist that serves as an assessment tool. Six of the

criteria that Hare (1991) includes in his Revised Psychopathy Checklist (PCL-R) are

as follows:

1. Glibness/superficial charm

2. Grandiose sense of self-worth

3. Proneness to boredom/need for stimulation

4. Pathological lying

5. Conning/manipulative

6. Lack of remorse

With some training, clinicians are able to gather information from interviews with

a person, along with material from significant others or institutional files (e.g., prison

records), and assign the person scores on the checklist, with high scores indicating

psychopathy (Hare, 1991).

The DSM-IV-TR criteria for antisocial personality disorder focus almost entirely

on observable behaviors (e.g., “impulsively and repeatedly changes employment,

residence, or sexual partners”). In contrast, the Cleckley/Hare criteria focus primarily

Durand 11-48

on underlying personality traits (e.g., being self-centered or manipulative). DSM-IV-

TR and previous versions chose to use only observable behaviors so that clinicians

could reliably agree on a diagnosis. The framers of the criteria felt that trying to assess

a personality trait—for example, whether someone was manipulative—would be more

difficult than determining whether the person engaged in certain behaviors, such as

repeated fighting.

Antisocial Personality, Psychopathy, and Criminality Although Cleckley did not

deny that many psychopaths are at greatly elevated risk for criminal and antisocial

behaviors, he did emphasize that some have few or no legal or interpersonal

difficulties. In other words, some psychopaths are not criminals and some do not

display the aggressiveness that is a DSM-IV-TR criterion for antisocial personality

disorder. Although the relationship between psychopathic personality and antisocial

personality disorder is uncertain, the two syndromes clearly do not overlap perfectly

(Hare, 1983). Figure 11.2 illustrates the relative overlap among the characteristics of

psychopathy as described by Cleckley and Hare, antisocial personality disorder as

outlined in DSM-IV-TR, and criminality, which includes all people who get into

trouble with the law.

Dyssocial psychopathy may be included with antisocial disorder but not

psychopathy (McNeil, 1970). The antisocial behavior of dyssocial psychopaths is

thought to originate in these people’s allegiance to a culturally deviant subgroup.

Many former gang delinquents may fall into this category, as may some members of

the Cosa Nostra and some ghetto guerrillas in South Africa. Unlike Cleckley

psychopaths, dyssocial psychopaths are presumed to have the capacity for guilt and

loyalty.

[Figure 11-2 goes here]

Durand 11-49

As you can see in the diagram, not everyone who has psychopathy or antisocial

personality disorder becomes involved with the legal system. What separates many in

this group from those who get into trouble with the law may be IQ. In a prospective,

longitudinal study, White, Moffit, and Silva (1989) followed almost 1,000 children,

beginning at age 5, to see what predicted antisocial behavior at age 15. They found

that, of the 5-year-olds determined to be at high risk for later delinquent behavior,

16% did indeed have run-ins with the law by the age of 15 and 84% did not. What

distinguished these two groups? In general, the at-risk children with lower IQs were

the ones who got in trouble. This suggests that having a higher IQ may help protect

some people from developing more serious problems or may at least prevent them

from getting caught! There may, however, be cultural differences in this finding. One

study discovered that the relationship between IQ and delinquency did not hold up for

African American youth (Donnellan, Ge, & Wenk, 2000). One explanation for this

difference may lie in the community. Some African American youth with higher

cognitive abilities may not have alternative opportunities in their neighborhoods for

avoiding criminal activities (e.g., employment opportunities).

Some psychopaths function successfully in certain segments of society (e.g.,

politics, business, entertainment). Because of the difficulty in identifying these