Psychoticism and Creativity: A Meta-analytic Review

Selcuk Acar and Mark A. Runco

University of Georgia

Quite a few studies have examined the association of creativity with psychoticism. The present

article reports a meta-analysis that was intended to clarify the strength of the association and to

explain variation in effects sizes reported in 32 previous studies. These 32 studies involved 6,771

participants, most of them college students. Results indicated that the effect sizes were heteroge-

neous, but the overall mean effect size was small (r

⫽ .16, k ⫽ 119, 95% CI [.12, .20]). Of most

importance was that the analyses examining 8 moderators (gender, age, the type of sample, the

particular measure of creativity, the content of the particular creativity test, the index of creativity,

the particular measure of psychoticism, and the domain of creativity) and 2 interaction terms

(Creativity Measure

⫻ Measure of Psychoticism and Creativity Measure ⫻ Content of Creativity

Test) showed that the relationship between creativity and psychoticism is large (r

⫽ .50, 95% CI

[.39, .60]) but only when psychoticism is measured by the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire and

uniqueness is the index of creativity. Results are discussed with respect to their theoretical

implications.

Keywords: creativity, psychoticism, meta-analysis, EPQ, uniqueness

Creativity has long been associated with psychopathology. Ar-

istotle’s statement “No great genius has ever been without some

madness” (and the concise label mad genius) is still debated in the

literature. The relationship between creativity and psychopathol-

ogy is difficult to pinpoint, in large part because creativity and

psychopathology are both complex concepts. Also, the relationship

is probably bidirectional, with creativity sometimes influencing

psychopathology and psychopathology sometimes influencing cre-

ativity (Runco, 1991). This makes causal explanations quite chal-

lenging. It is not surprising, then, in their review of studies on the

relationship between creativity and psychopathology, that Lau-

ronen et al. (2004) found multiple links. They concluded that there

was a “fragile association between creativity and mental disorder,

but the link is not apparent for all groups of mental disorders or for

all forms of creativity” (p. 81). This echoes the conclusion of

Richards (2000 –2001) in her overview of research on this topic.

Clearly, it is necessary to be very specific in any examination of

creativity and psychopathology. With that in mind, the focus of the

present article should be explicitly stated. This article is focused on

psychoticism. It is unique in its use of meta-analytic procedures

used to explore it and its relationship with creativity.

H. J. Eysenck (1995) defined psychoticism (P) as “a disposi-

tional variable or trait predisposing people to functional psychotic

disorders of all types” (p. 203). The concept of psychoticism was

derived from psychosis, which is the common label for some

mental disorders, including schizophrenia and manic depressive

proclivities. Psychoticism might be considered “subclinical,” just

as some schizoaffective tendencies are clearly distinct from

schizophrenia (and therefore not psychopathological; Sass, 2000 –

2001; Schuldberg, 2000 –2001). This, of course, makes the possi-

ble bridge to creative performance easier to understand, given that

creative performance must be effective (Runco, 1988; Runco,

Jaeger, & Cramond, in press). Unambiguous psychopathology

would make it difficult for the person to be effective, at least in the

sense of adaptive action. To simplify, P involves some character-

istics of psychotic disorders, but high P scores do not necessarily

mean a psychotic disorder (H. J. Eysenck, 1995).

H. J. Eysenck (1995) portrayed P as a continuum that has

altruistic, socialized, empathic, conventional, and conformist

personality traits on one extreme (low psychoticism; P–); and

criminal, impulsive, hostile, aggressive, psychopathic, schizoid,

unipolar depressive, affective disorders, schizoaffective, and

schizophrenic traits on other extreme (high psychoticism; P

⫹).

P

⫹ scorers tend to have difficulty attending or with vigilance.

They may be noncooperative but are often highly original in

word association tests. This last point is also useful when

examining a bridge with creativity. MacKinnon (1962) and

Cross, Cattell, and Butcher (1967), as well as H. J. Eysenck

(1997, 2003), suggested that the study of psychoticism can

contribute much to the understanding of creativity.

One attraction of this line of work is that it bridges personality

with the cognitive underpinnings of creative thinking. As H. J.

Eysenck (2003) described it, some people have loose and very

wide associative networks, which allow divergent thinking and the

discovery of remote and highly original ideas. This is overinclusive

thinking and is, for Eysenck, rooted in personality. Open-ended

tests reveal this characteristic because they allow people with

wider associative horizons to produce novel, original, and unusual

responses. Overinclusive tendencies underlie both creativity and

This article was published Online First February 27, 2012.

Selcuk Acar and Mark A. Runco, Torrance Creativity Center, University

of Georgia, Athens.

We thank Rod Dishman and Nur Cayirdag for their contributions and

valuable comments on this article.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Selcuk

Acar, 350 Aderhold Hall, Torrance Creativity Center, University of Geor-

gia, Athens, GA 30602. E-mail: acarse@uga.edu

Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts

© 2012 American Psychological Association

2012, Vol. 6, No. 4, 341–350

1931-3896/12/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/a0027497

341

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

psychotic disorders. In fact, H. J. H. J. Eysenck (2003) proposed

that this is precisely why so many unambiguously creative persons

have been diagnosed with psychopathology.

H. J. Eysenck (1994) empirically tested his theory by adminis-

tering the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire—Revised ([EPQ–R]

which involves the P, Neuroticism [N], Extraversion, and Lie

scales); tests of impulsiveness (I), empathy (Em), and venture-

someness (V); Word Association Rare Response Test (WARRT);

and Barron–Welsh Art Scale (B-W). Bivariate correlations be-

tween P and creativity measures were

⫺.25 (p ⬍ .01), .27 (p ⬍

.01), and .17 (ns) for usual, unique, and rare responses from the

WAT, and .16 (ns) with the total score from the B-W. Those were

lower than coefficients reported in the earlier study by Woody and

Claridge (1977), who found correlations ranging between .32 and

.68 ( p

⫽ .001). Multidimensional scaling analysis indicated that

creativity measures (P, I, V, WAT rare, WAT unique, and B-W)

constituted a cluster different from another cluster consisting of

Em, WAT common, and N.

Kline and Cooper (1986) used scales of flexibility of closure,

spontaneous flexibility, ideational fluency, word fluency, and orig-

inality from the Comprehensive Ability Battery (Hakstian & Cat-

tell, 1976) as creativity measures to test their relationship with P

from the EPQ (H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). Analyses were

conducted separately for men and women. The highest and the

only significant correlation was with word fluency (r

⫽ .20)

among men. All other correlations were lower and not statistically

significant.

Barron (1993) also suspected a relationship between creativity

and psychoticism. In fact, he found that creative individuals had

high scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory

Schizophrenia scale, compared with the general population (Bar-

ron, 1963/1990). Evidence regarding high ego strength in creative

individuals, along with a negative correlation between ego strength

and schizophrenia in the general population, convinced him to

argue that weird thoughts become defensibly original because ego

strength allows the individual to sort out inconvenient thoughts.

That is what he called controlled weirdness. Fodor (1995) reported

more recent evidence supporting a similar view. He found that

people with psychosis proneness and high ego strength were more

creative than those with psychosis proneness with low ego

strength, high ego strength without psychosis proneness, and low

ego strength without psychosis proneness. This finding held across

various measures of creativity.

Other findings raised some doubts about the relation of P to

creativity. Csikszentmihalyi (1993) argued that psychoticism does

not say much about creativity and the relationship between the two

is weak: “How significant is it, for instance, that less than 3% of

the variance in a divergent-thinking test filled out by university

students is in common with the variance in their scores on psy-

choticism?” (p. 189). On the other hand, Martindale (1993) ac-

cepted H. J. Eysenck’s (1993) theory because he felt that the

relationship between creativity and psychoticism explains swings

of physiological arousal in creative people.

Mixed results about the relationship between creativity and

psychoticism suggest that it would be beneficial to look more

closely. A meta-analysis of studies reporting the relationship be-

tween creativity and psychoticism could help to resolve the con-

troversy. Although psychoticism represents a broader conceptual-

ization than the P scale of H. J. Eysenck (1995), there were several

reasons to focus the meta-analysis on the P scale. First, the inclu-

sion of schizotypy would have complicated analyses because of

additional heterogeneity that hinders meaningful interpretation.

Besides, studies have shown that schizotypal scales involve quite

a bit of neuroticism (for a review, see H. J. Eysenck, 1993), which

could be the reason for loading on different factors than P in factor

analytic studies (e.g., White, Joseph, & Neil, 1995). In addition,

there are enough studies (more than 30) specifically examining the

relationship between the P scale and creativity measures. Prece-

dents for meta-analyses with 30 – 40 studies are easy to find (e.g.,

Bennett & Gibbons, 2000; Kim, 2008). Taken together, these

reasons supported the decision to conduct a meta-analysis that

focused entirely on P and creativity.

A meta-analysis on creativity and psychoticism could also ex-

amine specific factors to determine whether they lead to the

aforementioned mixed results. One such factor reflects the variety

of definitions and measures of creativity used in previous studies.

Large effect sizes would be expected from research using word

association and divergent thinking tests, at least if H. J. Eysenck

(1993, 2003) was correct in his suggestion that high psychoticism

is related to higher performance in overinclusive thinking. Word

association and divergent thinking tasks are open-ended and as

such allow this sort of associational processes (Glazer, 2009).

The nature of the test content, as verbal or figural, may be

relevant. Guilford (1968) reported that verbal (symbolic and se-

mantic) divergent thinking was related to higher IQ than figural

tests. Runco (1986) found that verbal and figural stimuli produce

qualitatively and quantitatively different outcomes. He raised the

possibility that each elicits a unique ideational and associative

process. Runco (1993) also noted the difference between ideations

generated from verbal and figural tasks in that the former tend to

be more “rote and preconceived” and the latter more “effortful and

spontaneous” (Runco, 1986, p. 351). Also, verbal measures could

be more subject to experiential bias (Runco & Acar, 2010). At-

tempts to enhance creativity, as measured by tests of divergent

thinking, at least sometimes lead to improvements in verbal indices

but not figural (Kauffman & Rich, 2010). Richardson (1986) used

these kinds of findings to postulate a two-factor theory of creativ-

ity. One factor is verbal, the other figural.

H. J. Eysenck and Eysenck (1976) examined the specific scores

from tests of divergent thinking and concluded that psychoticism is

more related to originality than fluency and flexibility. This fits

with later findings that reported positive correlation between psy-

choticism and uniqueness scores in word association tests (H. J.

Eysenck, 1993).

Domain differences in creative performance (Baer, 1998;

Plucker, 1998; Runco, 1987) may also be relevant to the

creativity–psychoticism relationship. Sass (2000 –2001), Ludwig

(1992), and Post (1994) all found that incidences of psychopathol-

ogy varied according to domains. Post, for example, found that

psychopathologies are more common among creative artists than

among creative scientists. For this reason, the domains of science,

writing, and arts, and relationships with psychoticism were exam-

ined in the meta-analysis.

The relationship between creativity and psychoticism may differ

in males and females, given that male gender is positively corre-

lated with P (H. J. Eysenck, 1993; H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck,

1976). Certainly, differences could also be attributed to social

factors that influence creative efforts and achievements (Csik-

342

ACAR AND RUNCO

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

szentmihalyi, 1993; Runco, Cramond, & Pagnani, 2010). With this

in mind, the meta-analyses, reported below, took into account sex,

as well as age.

The relationship of psychopathology and creativity may be most

obvious in studies with eminent individuals (Andreasen & Powers,

1974, 1975; Ludwig, 1994). Perhaps the presence of psychoticism

itself has an impact on the salience that attracts fame and earns

eminence. A related possibility is that fame leads to the collection

of detailed information (e.g., biographies and autobiographies),

which in turn allows easier interpretation of problems or psycho-

pathology. Consider as one example Isaac Newton. He was ru-

mored to have autism, but this rumor only started after autism was

defined (in the 1940s) and recognized as a legitimate diagnostic

category for psychologists and psychiatrists. Once autism was

defined, biographers could look back at Newton’s idiosyncrasies,

which were readily available. But they were only available because

Newton was famous and a great deal had been written about him.

Ludwig’s (1995) study of 1,000 eminent people indicated that

increased eminence is related to higher incidences of psychopa-

thology. Richards (1981) found higher levels of psychopathology

among eminent creators than among laypeople. Gotz and Gotz

(1979b) compared highly and less successful artists and found that

there was higher P in the former group but no difference in

originality. Bachtold (1980) studied 18 eminently creative artists

and scientists and concluded that the relationship between creativ-

ity and psychoticism is more related to assertiveness and success

rather than the creative process. This variation as a function of

eminence could apply specifically to psychoticism. Level of

achievement was therefore tested in the following meta-analysis.

Last but not least, different versions of the P scale could lead to

variation. The P scale (H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1976) was

designed to measure psychoticism as a personality trait that is

believed to exist in varying degrees in psychotic as well as non-

psychotic groups. Factor analytic methods were employed in its

construction and revision. Its main use is in nonpsychotic groups;

thus, it is focused on personality traits rather than symptoms. Still,

it has been used a criterion against psychiatric diagnoses. All 25

items are worded as “yes” or “no” questions (e.g., “Would being

in debt worry you?”; “Do most things taste the same to you?”; “Do

you try not to be rude to people?”). After the release of the P scale

as a component of the EPQ, a new version (S. B. G. Eysenck,

Eysenck, & Barrett, 1985) was developed to improve the psycho-

metric quality of the scale. There were three problems with the

initial form: low reliability, low range of scoring, and highly

skewed distribution of scores. After addition and removal of sev-

eral items, the revised P consisted of 32 items. The correlation of

the new and old P was .88 and .81 for male and female groups,

respectively. When compared with the old form, the revised P had

slightly higher reliability (.78 and .76 against .74 to .68 for males

and females, respectively), a remarkably larger range of scores,

and moderately improved skewness. The measure of psychoticism

was included in this study because of those significant differences

between the two forms.

In sum, based on the theoretical and prior empirical data from

previous investigations, we addressed the following questions:

1.

How strong is the relationship between creativity and

psychoticism?

2.

Are there domain-based differences in the relationship

between creativity and psychoticism?

3.

Can the strength of relationship between creativity and

psychoticism be explained by the type of creativity tests

used in the studies? More specifically, do divergent

thinking and word association tests yield higher effect

sizes than the other tests?

4.

Does the figural or verbal content of the creativity tests

make a difference in terms of the relationship between

creativity and psychoticism?

5.

To what degree do different indices of creativity explain

the variability in the effect sizes? More specifically, does

the number of unique responses yield higher effect sizes

than the others?

6.

Does the particular measure of psychoticism explain the

variability of effect sizes?

7.

Do eminence, age, and gender explain the strength of the

relationship between creativity and psychoticism?

Method

Literature Search

Studies published in 1975 through 2010 were located through an

extensive literature search in English. The year 1975 was chosen as

the starting year because use of the P scale became possible after

the publication of the EPQ (H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). The

literature search was mainly conducted through keywords, which

consisted of creativity and psychoticism. Those keywords were

entered to electronic databases including Google Scholar, Psycho-

logical Abstracts Index, Science Direct and Web of Science, and

Educational Resources Information Center search engines. Sec-

ond, the reference lists and bibliographies of the articles found

through electronic search were reviewed.

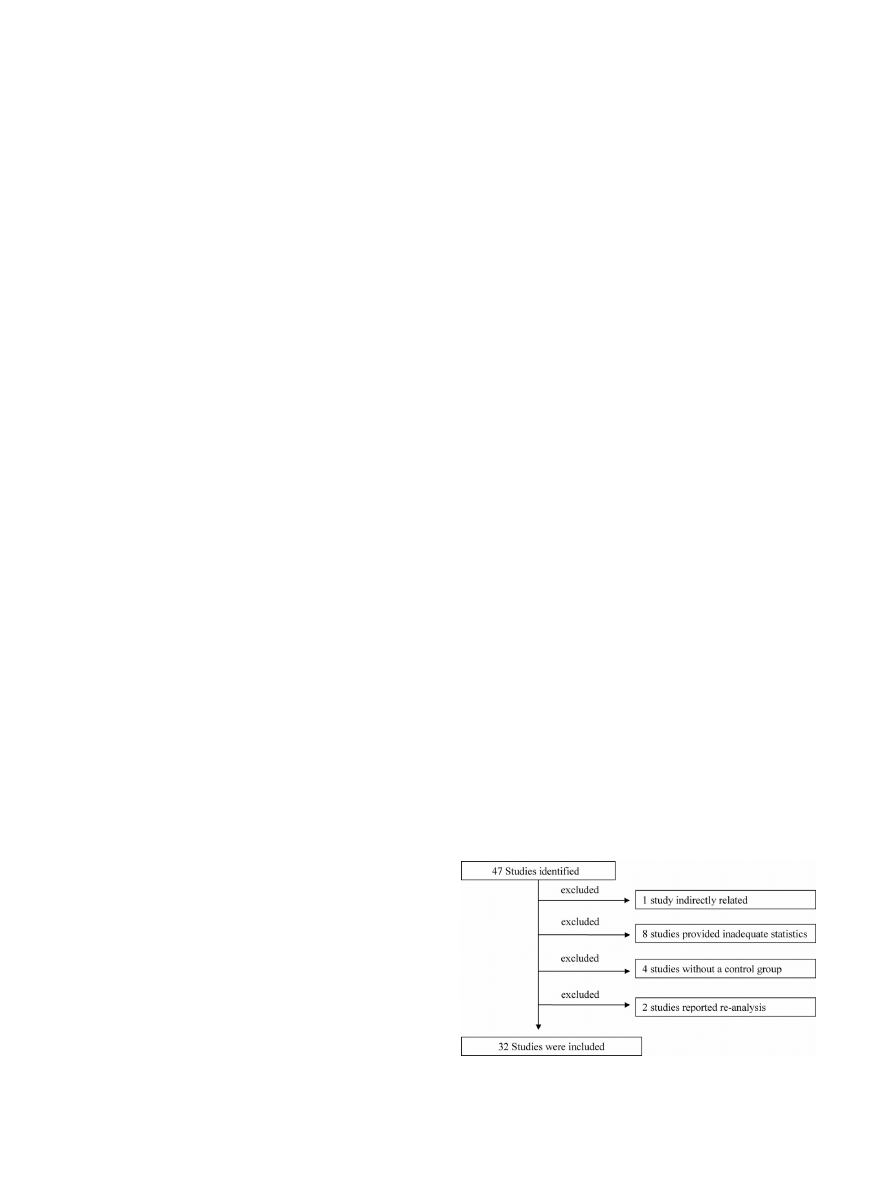

The decisions for inclusion and exclusion of the studies were

made based on the research questions listed above. Figure 1

summarizes this process. The following criteria were followed for

the studies to be included in or excluded from analyses:

Figure 1.

Flow chart for selection of studies.

343

PSYCHOTICISM AND CREATIVITY

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

1.

Publication: Only empirical articles that were published

in peer-reviewed journals were included. We did not

include dissertations, conference presentations, or other

research reports because they usually do not go through

a strict review process as do the journal articles.

2.

Sufficient statistics reported: Studies that did not report

basic statistics such as Pearson r, means, standard devi-

ations, t values, F values, or p values were not included

because they did not allow calculation of an effect size.

3.

Control group: Comparative studies reporting psychoti-

cism or creativity scores without any score of an appro-

priate control group were not included because those

scores were not comparable.

4.

Language: Only studies published in English were in-

cluded.

5.

Reanalysis: Studies that used the same data only once

were included. The preference was made on the basis of

completeness of the reporting.

Study Characteristics and Calculation of Effect Sizes

Thirty-two empirical studies representing 6,771 participants

allowed the calculation of 119 effect sizes. Most of the studies

yielded multiple effect sizes (the number of effect sizes per

article ranged from one to 14, with a mean of 3.75 and median

of 3). Most of the studies included samples of college students

in undergraduate and graduate programs. Given the age distri-

bution, we set a cutoff age at 30 years. Most studies used mixed

groups and reported the results together, but some studies

reported the results specific to gender, and some studies included

only a particular gender. Other studies were mixed but the sample was

dominated by a gender (above 75%). Such mixed studies were col-

lapsed to the dominant gender in the sample. To test our hypotheses

regarding different indices of creativity (which yielded multiple effect

sizes), we did not collapse multiple effect sizes from the same study.

Pearson r was selected as the effect size index because of the

nature of the research questions. Studies had different designs

but were mostly correlational and most of the original effect

sizes (n

⫽ 103) were reported as Pearson rs in bivariate corre-

lation tables. Other studies were comparative (P in high creative

vs. low creative; P in creative vs. control; creativity in high vs.

low psychoticism). Those studies reported means and standard

deviations that allowed calculating of F or t values. Some

provided their own t values. Each of these was converted to r

using the formula r

⫽ sqrt[t

2

/(t

2

⫹ df)]. When standard devia-

tions were not reported (i.e., Aguilar-Alonso, 1996), we calcu-

lated effect sizes from the exact p values, as suggested by

Rosenthal (1994).

After the effect sizes were retrieved and calculated, a grad-

uate student in educational psychology examined the data set to

ensure accuracy of the individual effect sizes and the codes for

the moderators. There was agreement of 97% across effect sizes

and codes. What few discrepancies existed were resolved by

logic.

Statistical Analysis

Because Pearson rs were not normally distributed, we trans-

formed them to Fisher’s Zr for the analyses. Effect size values

reported in the results were back-transformed to Pearson r. To give

more weight to studies with larger sample sizes, we weighted

individual correlation coefficients by the inverse variance weight

of (N – 3) associated with Zr values. A macro (SPSS 13.0) was

used to calculate the aggregated mean r effect size, the confidence

interval (95% CI), and the sampling error variance on the basis of

a random effects model. Random effects were employed to explain

both study-level sampling error and random sources of variability

(Lipsey & Wilson, 2001, p. 119). In this model, effects sizes were

weighted by the inverse of variance of each size. This yielded a

new estimated effect size value with the addition of a random

effects component (Hedges & Olkin, 1985).

The reliable interpretation of mean effect sizes is possible if

the data set is homogeneous. Heterogeneity was therefore tested

in the random effects model. The Q

T

value—representing the

sum of squares of each effect size that is related to the mean

weighted effect size—indicates heterogeneity if it is significant

at the p

⫽ .05 level. Sampling error accounting for less than

75% of the observed variance was used here as the indicator of

heterogeneity (Hedges & Olkin, 1985; Hunter, Schmidt, &

Jackson, 1982). Fail-safe N sample size (Rosenberg, 2005) was

also calculated. It indicates the estimated number of studies

with zero effect size that needs to be added to alter the results.

Moderators

Variability in the effect sizes that is not explained by sampling

error can be attributed to particular features of the study or to

moderators. For this reason, we prepared an iterative coding

scheme. There were eight moderators: domain, the measure of

creativity, the type (or content) of the creativity test, the index of

the creativity measure, the scale for or measure of psychoticism,

the sample characteristics, gender, and age. The definitions of the

moderators are provided in Table 1.

Analyses of Moderators

Each of eight moderators was coded with contrasts weights at

the .05 level (see Table 2). Two interaction terms (Measure of

Creativity

⫻ Index of Creativity Test and the Content of the

Creativity Test

⫻ the Index of Creativity Test) were entered to

weighted least squares regression analyses to determine inde-

pendent effects of each variable. For this analysis, we used a

macro (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001, pp. 216 –220) that runs within

SPSS. Maximum likelihood estimation was specified in the

mixed effects multiple linear regression analysis after adjusting

for nonindependence of the multiple effect sizes from a single

study. Tests of the regression model and contingent residual

value were requested. Last, number of effects (k), mean effect

sizes (r), 95% CIs, and p values for the planned contrasts were

provided by using another macro, from Lipsey and Wilson

(2001, pp. 209 –212; see Table 2).

Results

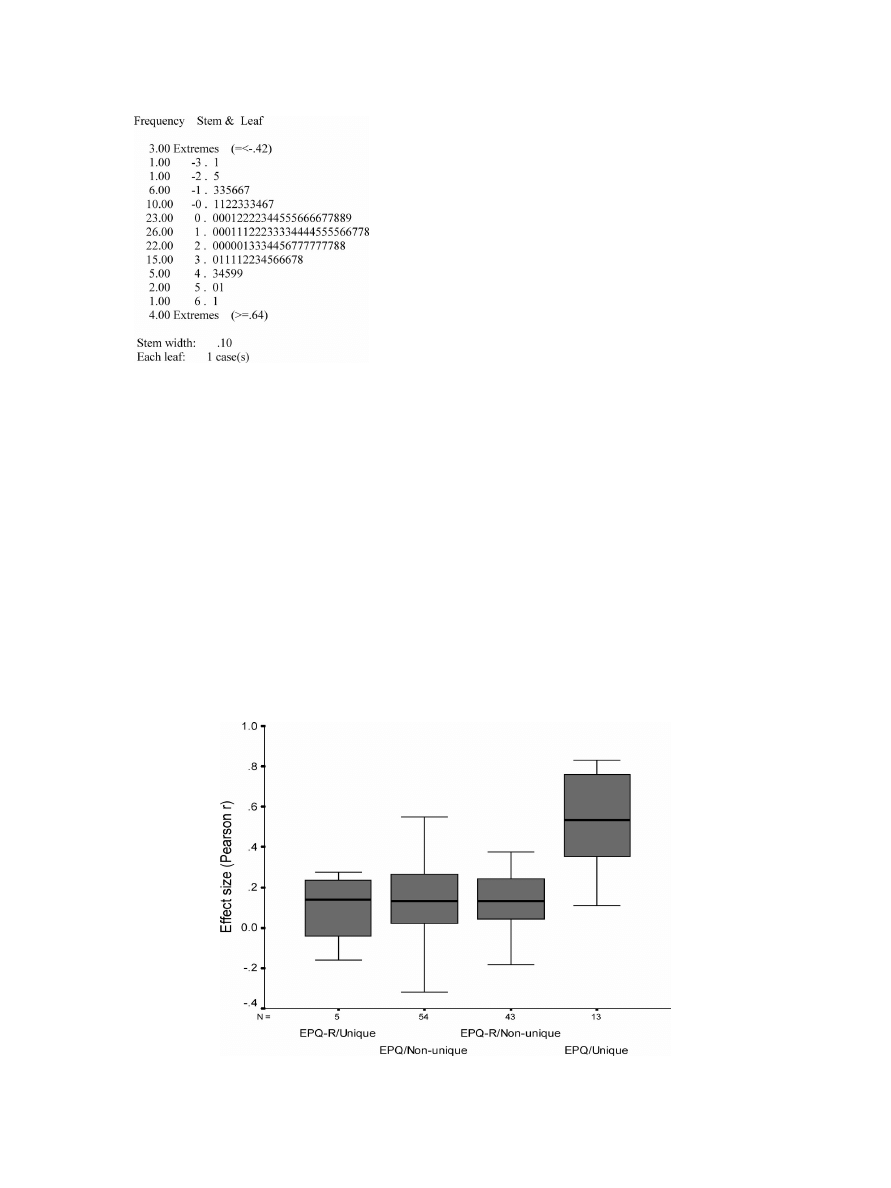

The first analysis examined the distribution of the effect sizes

that were based on Pearson r values (see Figure 2). The distri-

344

ACAR AND RUNCO

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Table 1

Definitions and Scope of Moderators

Moderator

Definition/test

Gender

Male

Samples with male groups above 75%

Female

Samples with female groups above 75%

Mixed

Samples with both males and females

Age (years)

Above 30

Samples with age above 30

Below 30

Samples with age below 30

Eminence

Eminent

Studies with eminent or highly successful individuals in a field of creativity

Noneminent

Studies with normal individuals

Measure of creativity

Divergent thinking (DT)

DT (Wallach & Kogan, 1965); Torrance Test of Creative Thinking, (Torrance,

1974, 2008); Inventiveness subscale of the Berlin Intelligence Structure Test

(Ja¨ger, Su¨ß, & Beauducel, 1997); House–Tree–Person Projective Drawing

Technique (H-T-P;Buck, 1992); Word Fluency (Goodglass & Kaplan, 1972);

Letter Fluency (Lezak, 1995), Thurstone Written Fluency Test, (Thurstone &

Thurstone, 1962); Alternate Uses (Guilford, Christensen, Merrifield, &

Wilson, 1978); and Utility Test (Wilson, Merrifield, & Guildford, 1969)

Word association tests

Word Association Rare Response Test (Kent-Rosanoff, 1910; Palermo &

Jenkins, 1964); Word Halo Test (Armstrong & McConaghy, 1977); AMT

(Merten & Fischer, 1999)

Barron–Welsh (B-W)

B-W (Barron & Welsh, 1987; Welsh & Barron, 1963); Polygons (Vanderplas

and Garvin, 1959); Welsh Figure Preference Test (Welsh, 1949); and

origence test (Rawlings & Georgiou, 2004)

Creative personality

Adjective Checklist or Creative Personality Scale (ACL/CPS; Gough, 1979)

Other

Remote Associates Test (Mednick, 1962); Bridge-the-Associative-Gap

(Gianotti, Mohr, Pizzagalli, Lehmann, & Brugger, 2001); conceptual

expansion (T. B. Ward, 1994); constraint of examples (Smith, Ward, &

Schumacher, 1993); creative imagery (Finke, 1990); How Do You Think

(Davis & Subkoviak, 1975); insight problems (Karimi, Windmann,

Gu¨ntu¨rku¨n, & Abraham, 2007); number of publications (Rushton, 1990); and

performance based (writing a story or poem; Martindale & Dailey, 1996)

Measure of psychoticism

P scale of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ)

H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975

P scale of the Eysenck Personality

Questionnaire—Revised (EPQ–R)

S. B. G.Eysenck et al., 1985; H. J. Eysenck & Eysenck, 1991

Symptom Checklist–90 (SCL-90)

Derogatis, Lipman, & Covi, 1973

Other

66-item anonymous survey (Rushton, 1990)

Content of creativity test

Verbal

All tests with verbal content, including DT, WAT, CPS/ACL, and other tests

Figural

All tests with figural content, including DT, B-W, and other tests

Both

Composite of both verbal and figural scores

Numerical

Items related to numbers in the Inventiveness scale of the Berlin Intelligence

Structure Test

None

Studies using no measures or number of publications as a measure of creativity

Indices of creativity

Fluency

Number of total responses or total score

Flexibility

Number of categories

Infrequency

Number of infrequent ideas including unique scores

Uniqueness

Number unique scores only

Practicality

Practical value of ideas

Other

Studies reporting no particular index of creativity

Domains

Arts

Participants were artists or measurement of creativity relied on artistic skills

(H-T-P, Buck, 1992; B-W, Welsh & Barron, 1963; Polygons, Vanderplas &

Garvin, 1959); Welsh Figure Preference Test (Barron & Welsh, 1987;

Welsh, 1949); and origence test (Rawlings & Georgiou, 2004)

Science

Measurement was scientific based (number of publications)

Writing

Participants were artists or measurement of creativity relied on writing skills

(Creative Writing—Poetry Measure; Joy, 2008)

General

General population or usual measures of creativity

Note.

DT

⫽ divergent thinking; WAT ⫽ Word Association Test; AMT ⫽ multiple-choice association test.

345

PSYCHOTICISM AND CREATIVITY

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

bution of effects was slightly skewed positively (g1

⫽ 228) and

leptokurtic (g2

⫽ 1.37). The fail-safe sample size was (N⫹)

8,452. The mean effect size (r) was .16 (k

⫽ 119, 95% CI [.12,

.20], p

⬍ .00001). Because of its heterogeneity, QT(118) ⫽

625.67, the mean effect size was not representative of the

studies included. The more meaningful analyses, therefore, are

probably those focused on the moderators (below).

The overall multiple regression model explained a significant

amount of the variance of the effect sizes, Q

R(11)

⫽ 89.36, p ⬍

.0001, R

2

⫽ .46; Q

E(98)

⫽ 104.59, p ⫽ .31. This model indicated

that the type of sample (

⫽ .22, z ⫽ 2.77, p ⫽ .006), the measure

of psychoticism (

⫽ .29, z ⫽ 3.35, p ⫽ .001), and the interaction

of Measure of Psychoticism

⫻ Index of Creativity Test ( ⫽ .58,

z

⫽ 4.48, p ⬍ .001) were independently related to effect size.

Planned comparisons indicated that studies consisting of eminent or

highly successful individuals reported smaller effect sizes (r

⫽ ⫺.04,

95% CI [

⫺.32, .24]) than those with only unexceptional participants

(r

⫽ .17, 95% CI [.13, .21]). In addition, studies measuring psychoti-

cism with the EPQ had a larger mean effect size (r

⫽ .20, 95% CI

[.15, .26]) than those using the EPQ–R (r

⫽ 11, 95% CI [.08, .15]) or

the Symptom Checklist–90 ([SCL-90] r

⫽ ⫺.44, 95% CI [⫺.55,

⫺.31]). Cell comparisons of the interaction of Measure of Psychoti-

cism

⫻ Index of Creativity Test indicated that the largest effect sizes

were reported in studies that used the EPQ as the measure of psy-

choticism and uniqueness as the index of creativity measure (r

⫽ .50.

95% CI [.39, .60]; see Figure 3). The other three cells each had mean

effect sizes slightly above .10.

All effect sizes for each level of the moderators are provided in

the Table 2 along with the number of effect sizes (k), the mean r

effect size values, the 95% CIs, and the p values for planned

comparisons. The descriptive results of the overall regression

model are also presented in the Table 3.

Table 2

Number of Studies and Categories and Univariate Analyses of Moderators

Moderator

Contrast weight

k

Mean r

95% CI

p

Gender

Male

⫺1

16

.13

[.05, .20]

.002

Female

.5

21

.17

[.11, .22]

⬍.001

Mixed

.5

82

.17

[.11, .22]

⬍.001

Age (years)

Below 30

1

93

.18

[.13, .22]

⬍.001

Above 30

⫺1

14

.05

[

⫺.07, .16]

.46

Not reported

0

12

.15

[.07, .23]

.001

Eminence

Eminent

⫺1

5

⫺.04

[

⫺.32, .24]

.78

Noneminent

1

114

.17

[.13, .21]

⬍.001

Measure of creativity

DT

1/2

70

.18

[.12, .24]

⬍.001

WAT

1/2

10

.22

[.14, .31]

⬍.001

B-W

⫺1/3

11

.11

[.03, .18]

.006

CPS

⫺1/3

4

.03

[

⫺.02, .08]

.27

Other measures

⫺1/3

20

.12

[.02, .21]

.02

Not used

—

4

.18

[.10, .25]

⬍.001

Type of creativity test

Verbal

0

71

.16

[.11, .22]

⬍.001

Figural

⫺1

37

.15

[.08, .22]

.001

Numerical

—

1

Both

—

2

.22

[.00, .43]

.05

None

1

8

.18

[.09, .27]

.001

Indices of creativity

Fluency

⫺1/4

34

.13

[.06, .21]

.001

Flexibility

⫺1/4

7

.00

[

⫺.11, .11]

.99

Infrequency

⫺1/4

17

.16

[.10, .22]

⬍.001

Uniqueness

1

18

.40

[.27, .51]

⬍.001

Practicality

—

1

Other

⫺1/4

42

.11

[.06, .16]

.001

Domains

Arts

⫺1/2

17

.14

[.08, .19]

⬍.001

Science

1

2

.36

[.19, .51]

.001

Writing

⫺1/2

10

.17

[.03, .30]

.02

General

0

90

.16

[.11, .21]

⬍.001

Measure of P

EPQ

1

67

.20

[.15, .26]

⬍.001

EPQ–R

0

49

.11

[.08, .15]

⬍.001

SCL-90

⫺1

2

⫺.44

[

⫺.55,⫺.31]

⬍.001

Other

—

Note.

DT

⫽ divergent thinking; WAT ⫽ Word Association Rare Response Test; B-W ⫽ Barron–Welsh

Art Scale; CPS

⫽ Creative Personality Scale; P ⫽ psychoticism; EPQ ⫽ Eysenck Personality Question-

naire; EPQ–R

⫽ Eysenck Personality Questionnaire—Revised; SCL-90 ⫽ Symptom Checklist–90.

346

ACAR AND RUNCO

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Discussion

The primary research question concerned the strength of the

relationship between creativity and psychoticism (Question 1 in

the introduction). This meta-analysis indicated that the effect size

can be as large as .50 (which is a large effect size by Cohen’s,

1988, oft-cited standards) when the EPQ is the measure of psy-

choticism and uniqueness is the index of creativity, but it ap-

proaches .00 with certain samples, measures, or indices of creativ-

ity. In most of cells in the table summarizing the univariate

analyses (see Table 2), the mean effect sizes are between .10 and

.20, which are regarded as a small effect (Cohen, 1988). Therefore,

the relationship between creativity and psychoticism is strong only

when the EPQ and uniqueness are involved. Relating this back to

the mad genius hypothesis, it appears that creativity and psycho-

pathology may have only an occasional and very specific relation-

ship rather than a broad and general one. As Simonton (2005)

suggested, the idea of a mad genius is probably often exaggerated.

The highest correlations with unique scores are consistent with

H. J. Eysenck’s (1993) expectations. Uniqueness is one way of

defining originality, and Eysenck argued that psychoticism is more

related to originality than fluency. It is important to note that

uniqueness and originality are not synonymous with creativity.

Creative ideas or products are original and sometimes unique, but

not all original ideas are really creative (H. J. Eysenck, 1993;

Runco, 2004; Runco et al., in press).

The variation among the psychoticism measures is intriguing.

The P scale of the earlier form, the EPQ, had a higher correlation

with the creativity measures than the revised form, the EPQ–R.

The revised P scale was intended to improve the psychometric

shortcomings of the EPQ, one of which was a skewed distribution

(S. B. G. Eysenck et al., 1985). The revised form included 13 new

items and excluded six items from the old form. Although the new

scale was more reliable and less skewed, it was still nonnormally

distributed. H. J. Eysenck (1992) mentioned the possibility that

skewness could be “inherent in the ‘true’ distribution of P” (p. 757)

rather than a psychometric deficiency. Given his theory linking

psychoticism with creativity, the earlier form is more defensible

than the revised form, at least with the assumption that P has a

naturally skewed distribution.

The specific measure of psychoticism used in the original stud-

ies (which we examined to answer Question 6) had an independent

effect (

⫽ .29, p ⫽ .001) in addition to being part of the

interaction effect. The interaction term compared the EPQ with the

EPQ–R, but the independent effect involved all three measures,

including the SCL-90. The SCL-90 was originally developed for

the “measurement of psychopathology in psychiatric and medical

outpatients” (Derogatis, Rickels, & Rock, 1976, p. 280). The items

in the Psychoticim subscale of SCL-90 include some symptoms of

schizophrenia and describe a withdrawn, isolated, even schizoid

Figure 2.

Stem-and-leaf plot of the r values.

Figure 3.

Effect size r values in four interaction groups.

347

PSYCHOTICISM AND CREATIVITY

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

lifestyle. As expected, it had a strong negative effect size (r

⫽

⫺.44) because it is a diagnostic tool rather than a personality-based

instrument, such as the P scale. In spite of the few effect sizes

available, this finding is potentially important in that it suggests

that psychoticism becomes counterproductive when it reaches the

level of mental illness. Several empirical studies have supported

this argument (Kinney et al., 2000 –2001; Schuldberg, 1990,

2000 –2001). This is entirely consistent with H. J. Eysenck’s

(1997) theory that psychoticism and psychosis represent one con-

tinuum and that only the former is subclinical and supports over-

inclusive thinking in a manner that is beneficial to creative per-

formances. It is also interesting to speculate about a parallel

between this finding and the inverted-U relationships that seems to

characterize the benefits of various kinds of asynchrony for cre-

ativity (Acar, 2011).

The mean effect sizes did not show differences between males

and females, nor between older and younger participants. There-

fore, they did not have independent effects. But there was an

independent effect for the type of sample (eminent or noneminent;

⫽ .22, p ⫽ .01). The mean effect size values were ⫺.04 for the

eminent group and .17 for the noneminent. This could be explained

by the possibility that noneminent people can express their “so-

cially unacceptable” behaviors listed in the P scale more comfort-

ably than eminent people.

None of other moderators had independent effects. It is inter-

esting that, among the creativity measures, the Creative Personal-

ity Scale had the lowest correlation with psychoticism, even

though both P and the Creative Personality Scale are personality-

based assessments. It might be useful to follow up on this using

another personality-based measure of creativity. Indeed, there

were limitations to this study. Some levels in the comparison group

had only a few effect sizes, and some confidence intervals were

quite large. Future studies could compute stronger analyses as they

provide more effect sizes for those specific levels of moderators.

For now, it appears that the theory of psychoticism is a moderately

useful one for studies of creativity.

The focus of the present study was on the relationship between

creativity and psychoticism. There certainly are conceptual and

theoretical issues involving these concepts outside of the meta-

analysis. For example, validity of P as a measure of psychoticism,

the relationship between schizotypy and P, and the role of other

personality traits in creativity are some of the issues that can be

examined in future studies.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the

meta-analysis.

*Abraham, A., Windmann, S., Daum, I., & Gu¨ntu¨rku¨n, O. (2005. Concep-

tual expansion and creative imagery as a function of psychoticism.

Consciousness and Cognition, 14, 520 –534. doi:10.1016/j.con-

cog.2004.12.003

Acar, S. (2011). Asynchronicity. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.),

Encyclopedia of creativity (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 72–77). San Diego, CA:

Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-375038-9.00015-7

*Aguilar-Alonso, A. (1996). Personality and creativity. Personality and

Individual Differences, 21, 959 –969.

Andreasen, N. J. C., & Powers, P. S. (1974). Overinclusive thinking in

mania and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 452– 456.

Andreasen, N. J. C., & Powers, P. S. (1975). Creativity and psychosis: An

examination of conceptual style. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32,

70 –73.

Armstrong, M. S., & McConaghy, N. (1977). Allusive thinking, the word

halo and verbosity. Psychological Medicine, 7, 439 – 445.

Bachtold, L. M. (1980). Psychoticism and creativity. Journal of Creative

Behavior, 14, 242–248.

Baer, J. (1998). The case for domain specificity in creativity. Creativity

Research Journal, 11, 173–177.

Barron, F. (1990). Creativity and psychological health. Buffalo, NY:

Creative Education Foundation. (Original work published 1963)

Barron, F. (1993). Controllable oddness as a resource in creativity. Psy-

chological Inquiry, 4, 182–l84.

Barron, F., & Welsh, G. W. (1987). Barron–Welsh Art Scale. Menlo Park,

CA: Mind Garden.

Bennett, D. S., & Gibbons, T. A. (2000). Efficacy of child cognitive–

behavioral interventions for antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis. Child

and Family Behavior Therapy, 22, 1–15.

*Booker, B. B., Fearn, M., & Francis, L. J. (2002). The personality profile

of artists. Irish Journal of Psychology, 22, 277–281.

Buck, J. N. (1992). House–Tree–Person Projective Drawing Technique:

Manual and interpretive guide. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psycholog-

ical Services.

*Burch, G. St. J., Hemsley, D. R., Corr, P., & Pavelis, C. (2006). Person-

ality, creativity and latent inhibition. European Journal of Personality,

20, 107–122.

*Chavez-Eakle, R. A., Lara, M. C., & Cruz-Fuentes, C. (2006). Personal-

ity: A possible bridge between creativity and psychopathology? Creativ-

ity Research Journal, 18, 27–38.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences

(2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

*Cox, A. J., & Leon, J. L. (1999). Negative schizotypal traits in the relation

of creativity to psychopathology. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 25–

36.

Cross, P. G., Cattell, R. B., & Butcher, H. J. (1967). The personality pattern

of creative artists. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 37, 292–

299.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1993). Does overinclusiveness equal creativity?

Psychological Inquiry, 4, 188 –189.

Davis, G. A., & Subkoviak, M. J. (1975). Multidimensional analysis of a

personality-based test of creative potential. Journal of Educational Mea-

surement, 12, 37– 43.

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., & Covi, L. (1973). SCL-90: An outpatient

psychiatric rating scale—Preliminary report. Psychopharmacology Bul-

letin, 9, 13–28.

Derogatis, L. R., Rickels, K., & Rock, A. F. (1979). The SCL-90 and the

MMPI: A step in the validation of a new self-report scale. British

Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 280 –289.

Eysenck, H. J. (1992). The definition and measurement of psychoticism.

Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 757–785.

Table 3

Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Moderators

Effect moderator

p

Gender

.09

.24

Age

⫺.10

.24

Type of sample

.22

.01

Content of creativity test

.12

.14

Measure of creativity

.01

.95

Index of creativity measure

⫺.03

.85

Measure of psychoticism

.29

.00

Domain of creativity

⫺.04

.65

Index of Creativity Measure

⫻ Measure of Psychoticism

.58

.00

Index of Creativity Measure

⫻ Content of Creativity Test

.06

.52

348

ACAR AND RUNCO

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Eysenck, H. J. (1993). Creativity and personality: Suggestions for a theory.

Psychological Inquiry, 4, 147–178.

*Eysenck, H. J. (1994). Creativity and personality: Word association,

origence, and psychoticism. Creativity Research Journal, 7, 209 –216.

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity. New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press.

Eysenck, H. J. (1997). Creativity and personality. In M. A. Runco (Ed.),

The creativity research handbook (pp. 41– 66). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton

Press.

Eysenck, H. (2003). Creativity, personality, and the convergent– divergent

continuum. In M. A. Runco (Ed.), Critical creative processes (pp.

95–114). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck

Personality Questionnaire (adult and junior). London, England: Hodder

& Stoughton.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1976). Psychoticism as a dimension

of personality. London, England: Hodder & Stoughton.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1991). Manual of the Eysenck

Personality Scales (EPS Adult). London, England: Hodder & Stoughton.

*Eysenck, H. J., & Furnham, A. (1993). Personality and the Barron–Welsh

Art Scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76, 837– 838.

Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version

of the Psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6,

21–29.

Finke, R. A. (1990). Creative imagery: Discoveries and inventions in

visualization. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Fodor, E. M. (1995). Subclinical manifestations of psychosis-proneness,

ego-strength, and creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 18,

635– 642.

Gianotti, L. R., Mohr, C., Pizzagalli, D., Lehmann, D., & Brugger, P.

(2001). Associative processing and paranormal belief. Psychiatry and

Clinical Neurosciences, 55, 595– 603.

Glazer, E. (2009). Rephrasing the madness and creativity debate: What is

the nature of the creative construct? Personality and Individual Differ-

ences, 46, 755–764.

Goodglass, H., & Kaplan, E. (1972). The assessment of aphasia and

related disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

*Gotz, K. O., & Gotz, K. (1979a). Personality characteristics of profes-

sional artists. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 49, 327–334.

Gotz, K. O., & Gotz, K. (1979b). Personality characteristics of successful

artists. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 49, 919 –924.

Gough, H. G. (1979). A creative personality scale for the Adjective Check

List. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1398 –1405.

Guilford, J. P. (1968). Intelligence, creativity and their educational impli-

cations. San Diego, CA: Robert Knapp.

Guilford, J., Christensen, P., Merrifield, P., & Wilson, R. (1978). Alternate

Uses (Form B, Form C). Orange, CA: Sheridan Psychological Services.

Hakstian, A. R., & Cattell, R. B. (1976). Manual for the Comprehensive

Ability Battery (CAB). Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and

Ability Testing.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis.

New York, NY: Academic Press.

*Hu, C., & Gong, Y. (1990). Personality differences between writers and

mathematicians on the EPQ. Personality and Individual Differences, 11,

637– 638.

Hunter, J. E., Schmidt, F. L., & Jackson, G. B. (1982). Meta-analysis:

Cumulating research findings across studies. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Ja¨ger, A. O., Su¨

, H. M., & Beauducel, A. (1997). Berliner

Intelligenzstruktur-Test. BIS-Test, Form 4 [Berlin Test of Intelligence

Structure, BIS-Test, Form 4]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

*Joy, S. (2008). Personality and creativity in art and writing: Innovation,

motivation, psychoticism, and (mal)adjustment. Creativity Research

Journal, 20, 262–277.

*Karimi, Z., Windmann, S., Gu¨ntu¨rku¨n, O., & Abraham, A. (2007). Insight

problem solving in individuals with high versus low schizotypy. Journal

of Research in Personality, 41, 473– 480.

Kauffman, J. D., & Rich, S. A. (2010, November). Torrance tests,

science, and future problem solving: A great mix. Paper presented at

57

th

Annual Convention of the National Association for Gifted Chil-

dren, Atlanta, GA.

Kent, G. H., & Rosanoff, A. J. (1910). A study of association in insanity.

Baltimore, MD: Lord Baltimore Press.

*Kidner, D. (1976). Creativity and socialization as predictors of abnormal-

ity. Psychological Reports, 39, 966.

Kim, K. H. (2008). Meta-analyses of the relationship of creative achieve-

ment to both IQ and divergent thinking test scores. Journal of Creative

Behavior, 42, 106 –130.

Kinney, D. K., Richards, R., Lowing, P. A., LeBlanc, D., Zimbalist, M. E.,

& Harlan, P. (2000 –2001). Creativity in offspring of schizophrenics and

controls. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 17–26.

*Kline, P., & Cooper, C. (1986). Psychoticism and creativity. Journal of

Genetic Psychology, 147, 183–188.

Lauronen, E., Veijola, J., Isohanni, I., Jones, P. B., Nieminen, P., &

Isohanni, M. (2004). Links between creativity and mental disorder.

Psychiatry, 67, 81–98.

Lezak, M. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford, England:

Oxford University Press.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ludwig, A. M. (1992). Creative achievement and psychopathology: Com-

parison among professions. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 46,

330 –356.

Ludwig, A. (1994). Mental illness and creative activity in female writers.

The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1650 –1656.

Ludwig, A. M. (1995). The price of greatness: Resolving the creativity and

madness controversy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

MacKinnon, D. W. (1962). The personality correlates of creativity: A study

of American architects. In G. S. Nielsen (Ed.), Proceedings of the 14th

International Congress of Applied Psychology, Copenhagen, 1961 (Vol.

2, pp. 11–39). Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard.

Martindale, C. (1993). Psychoticism, degeneration, and creativity. Psycho-

logical Inquiry, 4, 209 –211.

*Martindale, C. (2007). Creativity, primordial cognition, and personality.

Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1777–1785.

*Martindale, C., & Dailey, A. (1996). Creativity, primary process cogni-

tion, and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 20, 409 –

414.

*McCrae, R. R. (1987). Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to

experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1258 –

1265.

Mednick, S. A. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process.

Psychological Review, 69, 220 –232.

*Merten, T., & Fischer, I. (1999). Creativity, personality and word asso-

ciation responses: Associative behaviour in 40 supposedly creative per-

sons. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 933–942.

Palermo, D. S., & Jenkins, J. J. (1964). Word association norms: Grade

school through college. Minneapolis. MN: University of Minnesota

Press.

Plucker, J. A. (1998). Beware of simple conclusions: The case for the

content generality of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 179 –

182.

Post, F. (1994). Creativity and psychopathology. A study of 291 world-

famous men. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 22–34.

Rawlings, D., & Georgiou, G. (2004). Relating the components of figure

preference to the components of hypomania. Creativity Research Jour-

nal, 16, 49 –57.

*Rawlings, D., & Toogood, A. (1997). Using a “taboo response” measure

349

PSYCHOTICISM AND CREATIVITY

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

to examine the relationship between divergent thinking and psychoti-

cism. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 61– 68.

*Rawlings, D., Twomey, F., Burns, E., & Morris, S. (1998). Personality,

creativity and aesthetic preference: Comparing psychoticism, sensation

seeking, schizotypy and openness to experience. Empirical Studies of the

Arts, 16, 153–178.

*Reuter, M., Panksepp, J., Schnabel, N., Kellerhoff, N., Kempel, P., &

Hennig, J. (2005). Personality and biological markers of creativity.

European Journal of Personality, 19, 83–95.

Richards, R. L. (1981). Relationships between creativity and psycho-

pathology: An evolution and interpretation of the evidence. Genetic

Psychological Monographs, 103, 261–324.

Richards, R. (2000 –2001). Creativity and the schizophrenia spectrum:

More and more interesting. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 111–131.

Richardson, A. G. (1986). Two factors of creativity. Perceptual and Motor

Skills, 63, 379 –384.

Rosenberg, M. S. (2005). The file-drawer problem revisited: A general

weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis.

Evolution, 59, 464 – 468.

Rosenthal, R. (1994). Parametric measures of effect size. In H. Cooper &

L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 231–244).

New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

*Rossmann, E., & Fink, A. (2010). Do creative people use shorter asso-

ciative pathways? Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 891– 895.

Runco, M. A. (1986). Flexibility and originality in children’s divergent

thinking. Journal of Psychology, 120, 345–352.

Runco, M. A. (1987). The generality of creative performance in gifted and

nongifted children. Gifted Child Quarterly, 31, 121–125.

Runco, M. A. (1988). Creativity research: Originality, utility, and integra-

tion. Creativity Research Journal, 1, 1–17.

Runco, M. A. (1991). Divergent thinking. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Runco, M. A. (1993). Creativity, causality, and the separation of person-

ality and cognition. Psychological Inquiry, 4, 221–225.

Runco, M. A. (2004). Everyone has creative potential. In R. J. Sternberg,

E. L. Grigorenko, & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Creativity: From potential to

realization (pp. 21–30). Washington, DC: American Psychological As-

sociation.

Runco, M. A., & Acar, S. (2010). Do tests of divergent thinking have an

experiential bias? Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 4,

144 –148.

Runco, M. A., Cramond, B. L., & Pagnani, A. (2010). Gender differences

in creativity. In J. C. Chrisler & D. McCreary (Eds.), Handbook of

gender research in psychology (pp. 343–357). New York, NY: Springer.

Runco, M. A., Jaeger, G., & Cramond, B. (in press). The standard defini-

tion of creativity. Creativity Research Journal.

*Rushton, J. P. (1990). Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism. Person-

ality and Individual Differences, 11, 1291–1298.

*Rust, J., Golombok, S., & Abram, M. (1989). Creativity and schizotypal

thinking. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 150, 225–227.

Sass, L. A. (2000 –2001). Schizophrenia, modernism, and the “creative

imagination”: On creativity and psychopathology. Creativity Research

Journal, 13, 55–74.

Schuldberg, D. (1990). Schizotypal and hypomanic traits, creativity, and

psychological health. Creativity Research Journal, 3, 219 –231.

*Schuldberg, D. (2000 –2001). Six subclinical spectrum traits in normal

creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 13, 5–16.

*Schuldberg, D. (2005). Eysenck Personality Questionnaire scales and

paper-and-pencil tests related to creativity. Psychological Reports, 97,

180 –182.

Simonton, D. K. (2005). Are genius and madness related? Contemporary

answers to an ancient question. Psychiatric Times, 22, 21–23.

Smith, S. M., Ward, T. B., & Schumacher, J. S. (1993). Constraining

effects of examples in a creative generation task. Memory & Cognition,

21, 837– 845.

*Stavridou, A., & Furnham, A. (1996). The relationship between psychoti-

cism, trait creativity and the attentional mechanism of cognitive inhibi-

tion. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 143–153.

Thurstone, L. L., & Thurstone, T. G. (1962). Primary mental abilities.

Chicago, IL: Science Research Associates.

Torrance, E. P. (1974). The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking: Norms—

Technical manual. Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service.

Torrance, E. P. (2008). The Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking: Norms—

Technical manual. Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service.

*Upmanyu, V. V., & Kaur, K. (1986). Diagnostic utility of word associ-

ation emotional indicators. Psychological Studies, 32, 71–78.

*Upmanyu, V. V., & Upmanyu, S. (1988). Utility of word association

emotional indicators for predicting pathological characteristics. Person-

ality Study and Group Behaviour, 8, 13–22.

Vanderplas, J., & Garvin, E. (1959). The association value of random

shapes. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57, 147–154.

Wallach, M. A., & Kogan, N. (1965). Modes of thinking in young children:

A study of the creativity–intelligence distinction. New York, NY: Holt,

Rinehart & Winston.

*Ward, P. B., McConaghy, N., & Catts, S. V. (1991). Word association and

measures of psychosis proneness in university students. Personality and

Individual Differences, 12, 473– 480.

Ward, T. B. (1994). Structured imagination: The role of conceptual struc-

ture in exemplar generation. Cognitive Psychology, 27, 1– 40.

Welsh, G. S. (1949). Welsh Figure Preference Test. Palo Alto, CA:

Consulting Psychologists Press.

Welsh, G. S., & Barron, F. (1963). Barron–Welsh Art Scale. Palo Alto, CA:

Mind Garden.

White, J., Joseph, S., & Neil, A. (1995). Religiosity, psychoticism and

schizotypal traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 19, 847– 851.

Wilson, R. C., Merrifield, P. R., & Guilford, J. P. (1969). Scoring guide for

the Utility Test. Form A. Beverly Hills, CA: Sheridan Psychological

Services.

*Woody, E., & Claridge, G. (1977). Psychoticism and thinking. British

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 16, 241–248.

*Wuthrich, V., & Bates, T. C. (2001). Schizotypy and latent inhibition:

Non-linear linkage between psychometric and cognitive markers. Per-

sonality and Individual Differences, 30, 783–798.

Received July 18, 2011

Revision received November 29, 2011

Accepted January 3, 2012

䡲

350

ACAR AND RUNCO

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Psychology and Cognitive Science A H Maslow A Theory of Human Motivation

Eliade, Mircea Psychology and Comparative Religion

A Guide for Counsellors Psychotherapists and Counselling

evolutionary psychology and conceptual integration - opracowanie, psychologia, psychologia ewolucyjn

Building Applications and Creating DLLs in LabVIEW

Hallucinogenic Drugs And Plants In Psychotherapy And Shamanism

Zizek Psychoanalysis And The Post Political An Interview

Eliade, Mircea Psychology and Comparative Religion

Glaeser Psychology and the Market

Alta J LaDage Occult Psychology, A Comparison of Jungian Psychology and the Modern Qabalah

psychologia homo creativus 40 technik podkrecania umyslu hugh macleod ebook

Byrne Intrigue and Creativity

A Guide for Counsellors Psychotherapists and Counselling

Baker Critical and Creative Thinking

Antidepressant Awareness Part 3 Antidepressant Induced Psychosis and Mania

A Perspective on Psychology and Economics

CREATIVE EUROPE PROGRAMME TheCultural and Creative Sectors Loan Guarantee Facility (FAQ)

Folk Psychology and the Explanation of Human Behavior

Aldous Huxley On Drugs And Creativity

więcej podobnych podstron