Developing Process Based Inventing Activities: A Spider’s Web of Intrigue

and Creativity 2

Paper presented at the Sixth International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition,

Keele, United Kingdom, August, 2000.

Charles Byrne

Department of Applied Arts

Faculty of Education

University of Strathclyde

Glasgow, Scotland

Tel: 0141 950 3315 / 3476

Fax: 0141 950 3314

e-mail: c.g.byrne@strath.ac.uk

Introduction

In 1997, my colleague Mark Sheridan and I established the SCARLATTI Project which

aimed to investigate and document the teaching approaches and methodologies used by

Scottish secondary school music teachers in the area of Inventing (Composing, Improvising

and Arranging) and to share good practice, findings and thoughts with interested colleagues.

It was envisaged that a number of teachers would be able to access and share information

via e-mail and world wide web based discussion groups and music teachers who subscribed

to the project were invited to contribute to the SCARLATTI HyperNews discussion group

established at the Clyde Virtual University. HyperNews has the facility to link quickly and

easily with other sites and we began to create a bank of information and materials that we

hoped teachers would find of some use. It is within this context that we began developing

the Spider’s Web Composing Lessons.

Models of teaching composing

In looking for models of good teaching in composing and improvising and for background

reading that could be of use to practising teachers, we found much of interest in the

‘teaching thinking’ literature, particularly DeCorte’s idea of a ‘powerful learning

environment’ (1990). Having been Principal Teachers of Music in busy, urban secondary

schools, we recognised this phenomenon as being almost exactly the same as ‘lunchtime’ in

our own music departments. A budding Rock band is busy learning and perfecting a song,

pairs of youngsters are helping each other learn their parts ready for the Wind Band

rehearsal, two or three guitarists are composing a song together and a student piano player

is leading a small group through songs from the film ‘Titanic’.

In this scenario, capable peers may be working with novice songwriters or performers.

‘Modelling’ of expected levels of performance is given and support, or ‘scaffolding’

(Wood, Bruner & Ross, 1976) for further learning is provided. Encouragement and advice

is offered, and accepted and this ‘coaching’ gradually gives way to ‘fading’ when the

learner has gained sufficient experience to be able to regulate her own learning (DeCorte,

1990; McGuinness & Nisbet, 1991).

We looked at Guilford’s work (1967) identifying the stages in the creative process outlined

by Dewey (1910), Wallas (1926; 1945) and Rossman (1931) and we were intrigued by the

emphasis placed on reviewing and evaluating within each of these models. The link between

creative thinking and problem solving which, according to Guilford (1967) are essentially

the same major operation, led us to conceive of a series of composing lessons consisting of

short musical steps. At any point, students would be able to ask questions, solve musical

problems and make decisions as to the development of the musical material as a result of

their own evaluation and reflection.

Process, Product and Passing exams

The purpose of the Spider’s Web Composing Lessons is not to facilitate the study of

children’s compositional processes and products. Rather the purpose is to provide

opportunities for novice composers to develop skills and strategies in handling musical

materials within an organised framework.

New approaches to teaching and learning composing often cause teachers to think

immediately of problems, usually assessment. Many music teachers in Scotland adopt a

fairly short term approach to Inventing; the examination led syllabus dictates that a folio of

compositions, improvisations or arrangements must be completed by a certain date so, the

product immediately becomes the focus of attention, rather than the process. It may be that

some music teachers are uncomfortable “with the prospect of designing activities for pupils

which add to their general educational and musical development rather than accomplish the

desired objective of preparing a folio of inventions which will secure them a good pass at

Standard Grade music” (Byrne & Sheridan, 1998a, p. 299). Barrett (1998) observes that

while Kratus (1994) and Bunting (1988) place an emphasis on the compositional process, it

is interesting to note that “Bunting (1988) acknowledges that analysis of students’

compositional products is an important part of any assessment procedure” (Barrett, 1998,

p.14). It seems that it is not only in Scotland that if it moves, we must assess it.

Webster (1988) proposes a theory of creative-thinking in music based on a synthesis of

convergent and divergent thinking. Many possible solutions to a musical problem are

generated and this focusing on the process, since thinking implies a present tense activity,

“becomes a kind of ‘structured play’” (Webster, 1988, p. 77). Students may have recourse

to knowledge or musical concepts already learned and may apply convergent thinking skills

in assimilating new and existing knowledge. Such an approach encourages teachers to

allow the student “space and freedom to think and experiment, while the requirements of

the product for examination takes a back seat. The process, however is under scrutiny and

the core skills components of critical thinking and planning and organising, employed in

the process can be rewarded” (Byrne & Sheridan, 1999). With the introduction in Scotland

of the new Higher Still courses and pathways there has been a slight shift toward assessing

the process with the requirement for students to complete a composing log giving details of

the compositional processes and techniques used (Higher Still Development Unit, 1997). In

these web based composing lessons, the emphasis is firmly placed on the process of

composing.

Composers in the classroom

As composers and secondary music teachers, Mark Sheridan and I had over twenty-five

years experience of creating materials for our students and we believed that learning to

compose could be both stimulating and fun provided that activities were framed

appropriately. Our teaching of composing and improvising in the classroom had been based

on giving students real musical problems which they were capable of solving rather than

mere paper and pencil exercises in the use of notation and chord boxes which, while they

may have produced “correct answer” type results, were, it is argued, of little musical

significance or value. In a recent study (Sheridan & Byrne, submitted for publication) we

describe these “correct answer” type activities as “Closed Critical Thinking Activities” in

which the student is given very little opportunity to experiment with or explore different

sounds and combinations. Although there may be more than one correct answer, free and

original thought is often excluded due to the contrived nature of the musical problem.

Here is an example of a popular composing activity. (Popular by teachers’ reckoning, we

have not yet asked the students!)

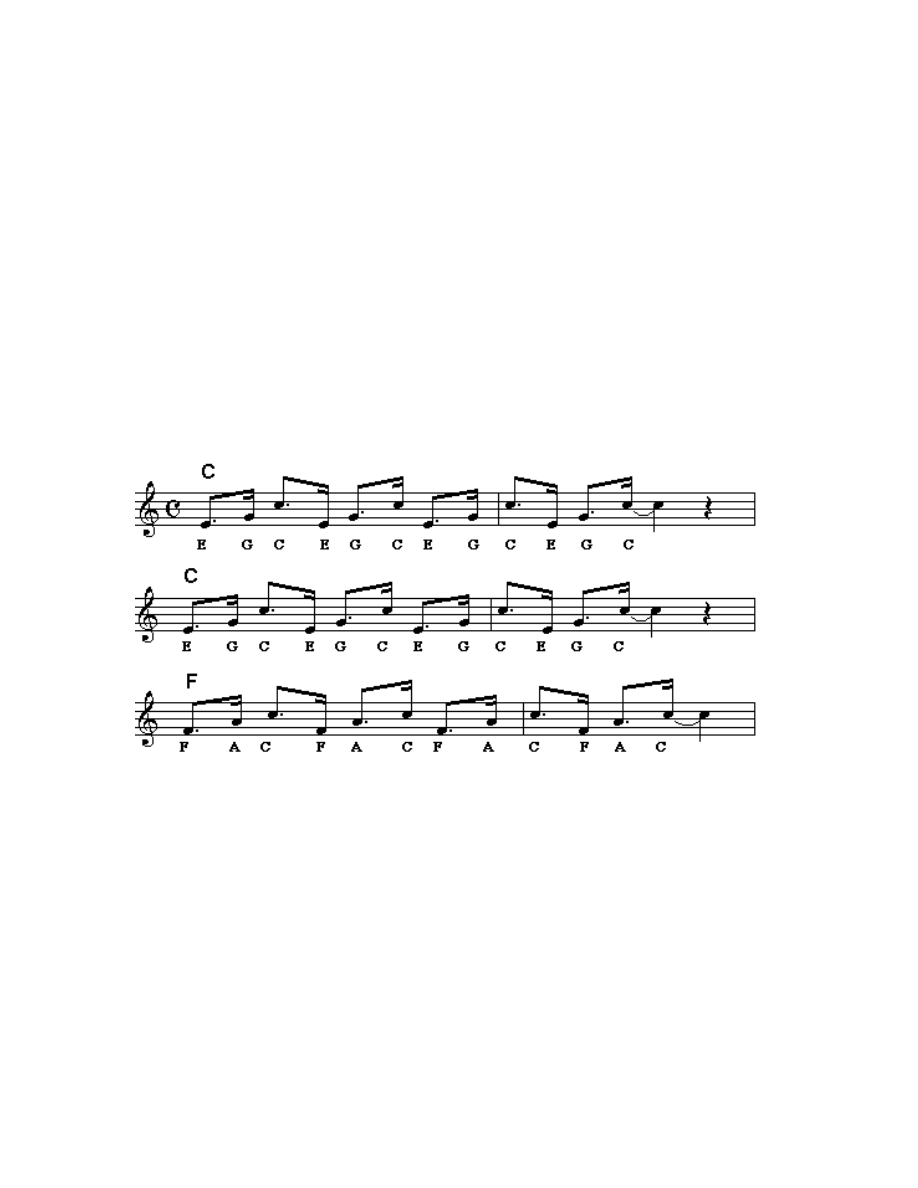

The class have finished playing “In the Mood” on keyboards and a natural composing

activity developing from this is to create a new melody that fits the chord scheme for “In the

Mood” and makes use of the same jazzy, syncopated rhythms (Figure 1).

Figure 1

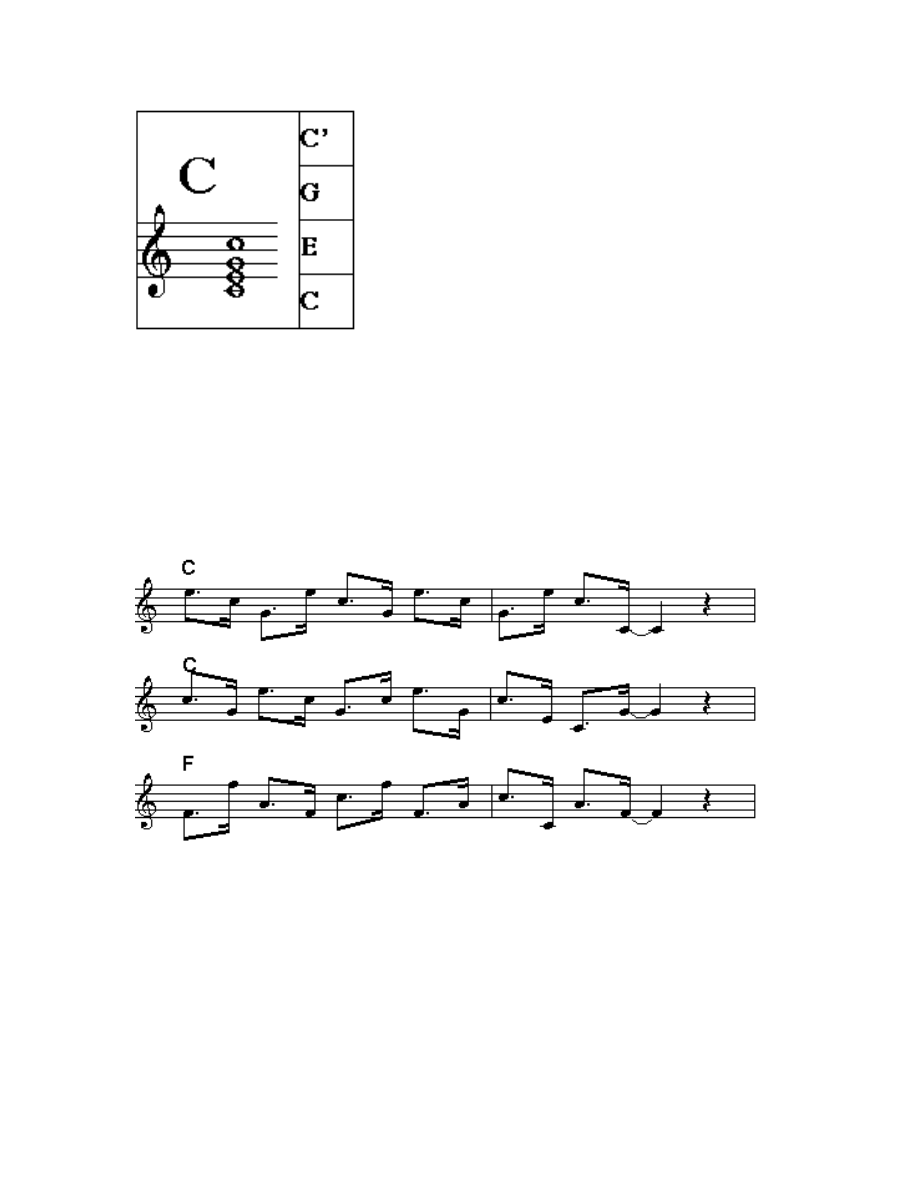

Students are required to use the same rhythms and to select notes from the chord of C

major that will fit, creating their own tune. Chords are often shown in the form of chord

boxes which spell out either the letter names, the pitches in standard notation or both. Figure

2 is an example of one format.

Figure 2

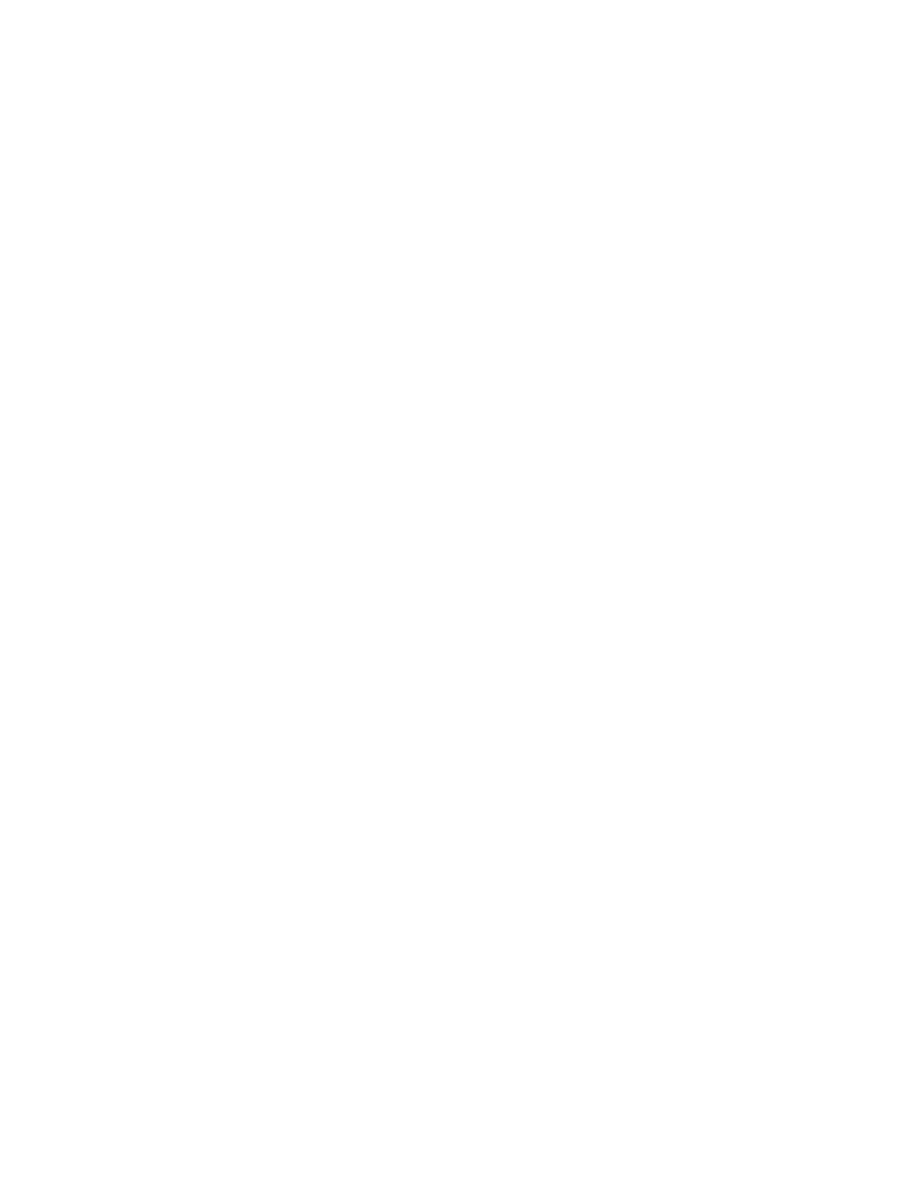

Students are given few rules and are simply advised to use the notes of the chord to make a

new tune. Enlightened teachers may ensure that students use a musical instrument during

this "composing" process while others will expect students to use pencil and manuscript

paper and to check their results later, either by themselves, with a more capable peer or with

the teacher at the piano. Here is the sort of result that can be expected (Figure 3):

Figure 3

The contrived nature of activities such as this may be described as "occupying knowledge-

restricted problem environments" (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1985, p. 66). The student is

only allowed to use material contained within the problem to provide a solution. Thinking

must therefore be convergent since the process involves the solver in selecting one set of

permutations which closely match the predicted outcome. The moving around of letter

names on the page can, at best, be a logical-mathematical challenge and, at worst, a

meaningless and futile exercise. As Elliott puts it “One learns to compose by being

inducted into culture-based and practice-centered ways of musical thinking” (Elliott, 1995,

p 162) and not, surely, by moving letters and symbols around on a piece of paper without

any point of reference in the sound world being established. Composers often use the piano

to check material that has already been worked out in their head. Similarly, there is little

point in requiring a musical composition to be notated if, as Odam observes “a child (and

possibly the teacher) has interpreted the task of inventing a piece of music on a pitched-

percussion instrument as the random playing of pitches and their recording” (Odam, 1995,

p 43).

Inventing as part of Standard Grade Music

Evidence suggests (Byrne & Sheridan, 1998a) that the Inventing element of Standard Grade

Music (SEB, 1988) is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the area where students achieve poorer

grades than the other elements of solo and group performing, and listening. In 1991, 36%

of candidates achieved grades 1 or 2 in the Inventing element of Standard Grade Music

compared to 53% achieving the same grades for Solo Performance. By 1996, the figure for

Solo Performance had risen to 63% while that for Inventing had risen to only 43% (Byrne

& Sheridan, 1998a). Teachers often admit to lack of confidence in teaching and assessing

inventing work and perhaps this is reflected in the fact that 90 secondary schools are now

involved in the SCARLATTI Project which represents nearly 50% of all schools invited to

participate. Teachers are always looking for new material and we were happy to use the

SCARLATTI Project web based lessons as a vehicle for introducing teachers to some of the

ideas discussed in this paper. Data from the University’s world wide web server indicate

that many individuals are downloading the materials but few are responding to the invitation

to submit feedback and evaluation of the lessons.

Spider’s Web Composing Lessons

The first lesson in the series makes use of text and graphics only and asks students to make

decisions on rhythms and melodic ideas using very few pitches. Critical responses are

encouraged through the use of questions such as “Which rhythm did you like best and

why?”. Students are reminded that “this is a disposable, process based activity. Remember

all the steps if you can but feel free to forget all of the notes and rhythms which you have

just worked with” (Byrne & Sheridan, 1998b).

The second lesson, ‘Pattern Duet’, builds upon some of the ideas in the first lesson and

makes use of sound files. These were recorded using a Roland Digital Piano and MC-50

Sequencer. Each short segment was then recorded onto a Mini Disc Recorder and converted

into aif format which can be recognised by web browsers. The music notation graphics for

all lessons were produced using Mosaic Composer software from Mark of the Unicorn.

Small pieces of notation were clipped using the Flash-It utility and then converted to gif

files in Claris HomePage 3.0 web site design software.

‘Pattern Duet’ introduces the notion of combining different melodic ideas and the sound

files allow the student to hear the melodic shape of each pattern although not in

combination. Teachers and students will have to devise methods of doing this in the

classroom, whether by using recording devices or by setting up the activity for small groups

of instrumentalists. Individual students could work at a computer workstation, responding to

the material on an electronic keyboard with a built in sequencer. Hyperlinks are included in

this lesson in order to provide definitions of new or unfamiliar concepts. For example,

transposition is illustrated in the section built around the chord of G major and a definition

is also given. Finally, understanding of the concept can be checked by asking the student to

make the transposition that will make each pattern fit with the chord of E minor.

The third lesson in the series, ‘Happy Birthday Mr Smith’ illustrates how an effective piece

of music can be created using a limited range of notes and some interesting, yet simple

chords. This is an example of an exploded composition, allowing the student to feel and

hear how a piece has been developed from a tiny musical idea. Users are able to hear parts

separately and in combination with each other and the generation of material, textural

considerations and instrumentation are explored.

Although these composing lessons represent pitches and rhythms in conventional notation

the sound files have been included as additional points of reference. It is important that

teachers do not simply treat these lessons as yet another paper based exercise that can be

‘marked’ later on. There is, quite deliberately, no emphasis placed on students being either

able to or required to write down their compositions in any conventional way. Of course,

students may want to begin to do this and activities such as these may well provide the

motivation for some to learn how to use notation. Salaman (1997) asks “ what musical

purpose staff notation serves in the lives of average pupils” (p. 148) and if the answer has

to do with wanting to record an interesting musical result then the purpose of learning

notation has moved beyond that of acquiring inert knowledge (Scardamalia & Bereiter,

1985).

Feedback and evaluation

So far, there has been little feedback from teachers or students regarding the lessons’ ease

of use, suitability of tasks and the practical implications of their use in the classroom.

Electronic evaluation forms are included on the web site although few have been completed

and returned. Those that have replied to the request for comments and feedback suggest that

the activities are appropriate for secondary years 1 and 2 students and the third lesson,

Happy Birthday Mr Smith being useful for years 3 and 4 as preparation for, guess what,

completion of the inventing folio. As models for the use of text and graphics they have

proved useful for student teachers.

The lessons are no substitute for good teaching and good teachers will know how much

help to give individuals and when to provide support and advice. Each set of tasks and

examples could be done either by individual students or small groups working together. The

results of working through ‘Pattern Duet’, for example, could be a series of MIDI files or a

new set of material that could form the basis of another project.

Further development

Other composing lessons are planned including one which introduces a new thinking tool

for composers which draws upon different views on the stages of the creative process

(Dewey, 1910; Wallas, 1926, 1945; Rossman, 1931; Weisberg, 1986) as well as the work

of Tony Buzan (1974) and Edward de Bono (1976, 1982). The ORIENT thinking tool is

intended as an aid to helping students through the composing process. It will not actually

compose any of the music but it should help the novice composer organise his or her

thoughts and ideas, providing opportunities to allow them to check how the composing

process is going.

Once again, the emphasis is on the process and is offered to music teachers in an effort to

move them away from the product oriented approach in the hope that they will see the

importance of providing useful skills in composing and thinking that students can apply in

later life and which will form the basis of a continuing interest in creative work in music.

References

Barrett, M. (1998). Researching Children’s Compositional Process and Products:

Connections to Music Education Practice? In, Children Composing, B. Sundin, G. E.

McPherson & G. Folkestad (Eds.) Malmo: Lund University.

Bunting, R. (1988). Composing music: Case studies in the teaching and learning process.

British Journal of Music Education, 5(3), 269-310.

Buzan, T. (1974).Use Your Head. London: BBC Books.

Byrne, C. & Sheridan, M. (1998a). Music: a source of deep imaginative satisfaction?

British Journal of Music Education, 15(3), 295-301.

Byrne, C. & Sheridan, M. (1998b). Spider’s Web Composing Lessons.

http://www.strath.ac.uk/Departments/AppliedArts/lessonmenu/complessons.html

Byrne, C. & Sheridan, M. (1999). Think Music. In, Effective Music Teaching. CD-ROM,

Edinburgh: Higher Still Development Unit.

de Bono (1976). Teaching Thinking. London: Temple Smith.

de Bono, E. (1982). de Bono’s Thinking Course. London: British Broadcasting

Corporation.

DeCorte, E. (1990). Towards powerful learning environments for the acquisition of problem

solving skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 5, 5-19.

Dewey, J. (1910). How We Think. Boston: Heath.

Elliott, D. J. (1985). Music Matters. A New Philosophy of Music Education. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The Nature of Human Intelligence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Higher Still Development Unit (1997). Subject Guide: Music. Edinburgh: Higher Still

Development Unit.

Kratus, J. (1994). The ways children compose. In H. Lees (Ed.) Musical connections:

Tradition and change, (Proceedings of the 21st World Conference of the International

Society for Music Education, held in Tampa, Florida) Auckland, NZ: Uniprint, The

University of Auckland, 128-141.

McGuinness, C. & Nisbet, J. (1991) ‘Teaching Thinking in Europe’, British Journal of

Educational Psychology, 61, 174-186.

Odam, G. (1995). The Sounding Symbol. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes (Publishers) Ltd.

Rossman, J. (1931). The Psychology of the Inventor. Washington, D.C.: Inventors

Publishing Co.

Salaman, W. (1997). Keyboards in schools. British Journal of Music Education, 14(2),

143-149.

Scardamalia, M, & Bereiter, C. (1985). Cognitive Coping Strategies and the Problem of

“Inert Knowledge”. In, S. F. Chipman, J. W. Segal & R. Glaser (Eds.),Thinking and

Learning Skills, Volume 2: Research and Open Questions, New Jersey: Laurence

Earlbaum Associates.

Scottish Examination Board. (1988). Scottish Certificate of Education: Standard Grade;

Arrangements in Music. Dalkeith: Scottish Examination Board.

Sheridan, M. & Byrne, C. (submitted for publication). The SCARLATTI Papers.

Wallas, G. (1926; 1945). The Art of Thought. London: Watts.

Webster, P. R. (1988). Creative Thinking in Music: Approaches to Research. In, J.T.Gates

(Ed) Music Education in the United States: Contemporary Issues. Tuscaloosa: The

University of Alabama Press.

Weisberg, R. (1986). Creativity: genius and other myths. New York: W. H. Freeman and

Company.

Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S. & Ross, G. (1976) ‘The role of tutoring in problem solving’,

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89-100.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Building Applications and Creating DLLs in LabVIEW

Arcana Evolved Ruins of Intrigue NPC Creation Kit

Psychoticism and Creativity

Baker Critical and Creative Thinking

CREATIVE EUROPE PROGRAMME TheCultural and Creative Sectors Loan Guarantee Facility (FAQ)

Aldous Huxley On Drugs And Creativity

Salvation and Creativity Two Understandings of Christianity

Creation of Financial Instruments for Financing Investments in Culture Heritage and Cultural and Cre

Applications of Genetic Algorithms to Malware Detection and Creation

Social networks personal values and creativity

Collaboration and creativity The small world problem

conceptual storage in bilinguals and its?fects on creativi

Creationism and?rwinism

1 ANSYS Command File Creation and Execution

Creativity and Convention

Creating a dd dcfldd Image Using Automated Image & Restore (AIR) HowtoForge Linux Howtos and Tutor

więcej podobnych podstron