Garden ponds and

boggy areas:

havens for wildlife

working today

for nature tomorrow

Ponds and biodiversity

England is damp and cloudy, and

naturally full of ponds, wetlands and

the plants and animals they support.

But the drive to intensify agriculture

has hit hard. Land drainage, from the

Romans onwards, reduced pond

numbers to about 1,250,000 in 1890

and to only about 400,000 today.

Most of these ponds were made for

watering stock, or were used for

foundries, mills or water storage.

Many are now polluted from run-off

from roads and agricultural fields.

Others are changing naturally,

through lack of management, and are

overgrown by trees or filling with

silt. While still important for many

species of wildlife, they rarely contain

an abundance of common species.

Garden ponds help to reduce this

loss. Few will sustain endangered or

highly specialised species, but they

can be a real haven for many others.

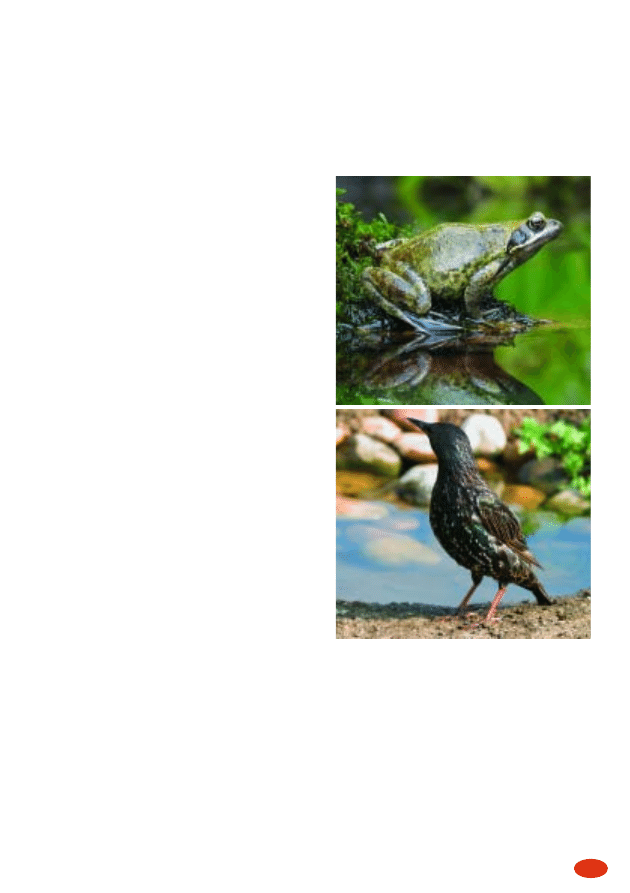

Frogs may be doing better in

suburban gardens than in the wider

countryside. Well-designed garden

ponds can provide a refuge for many

species of freshwater plants and

animals. They are valuable for other

wildlife too. Birds drink and bathe in

the shallow margins, or eat the

autumn seed heads of reeds. Insects

feed on exposed mud, and at night,

bats hunt for flying insects over the

water. If you want to see plenty of

wildlife close to home, put in a

garden pond.

3

Garden ponds

Why have a garden pond?

Most people are fascinated by water and a garden pond is an excellent

way of having it close to home. Garden ponds provide beauty and

interest, and if well designed, will make a real difference for wildlife.

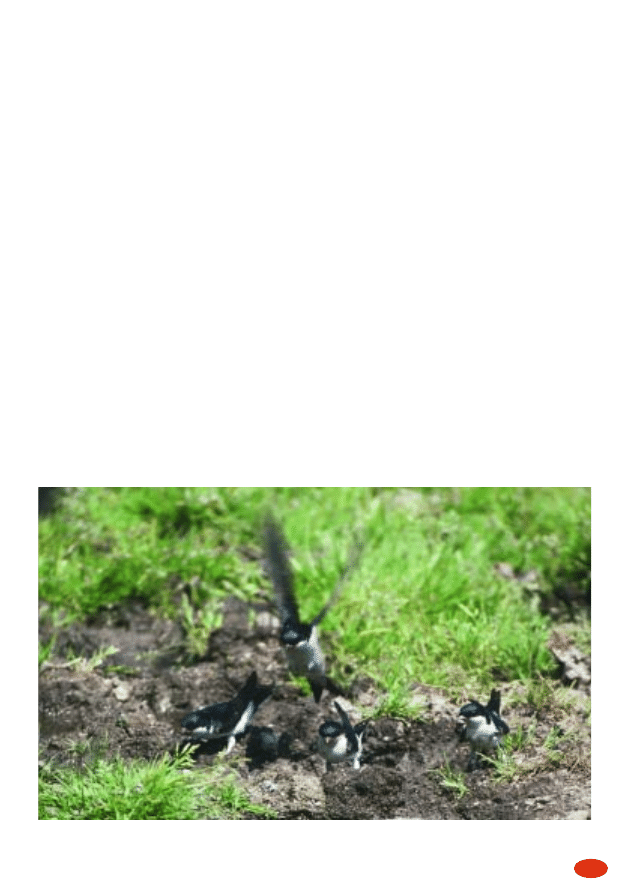

Top: Frog with reflection. Andy Sands

Bottom: Starling. Paul Keene

Opposite: Ragged robin. Chris Gibson/English Nature

4

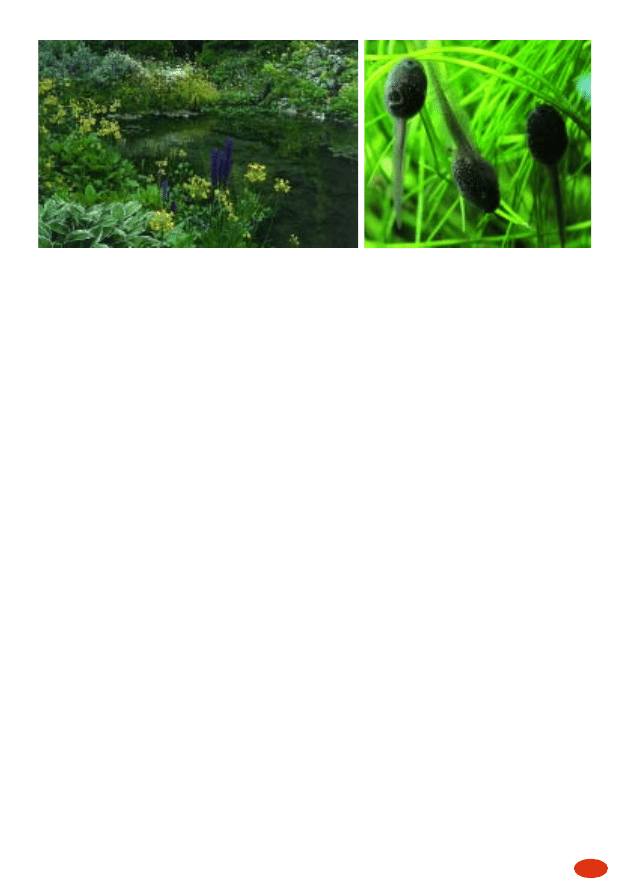

Ponds and garden beauty

Ponds can look marvellous in

gardens. Water gives a natural,

peaceful effect. Reflections add

brilliance, colour and movement.

Having a pond – especially with a

bog garden – allows a greater variety

of plants to thrive, and even in the

most scorching summer, ponds

remain lush and refreshing to the

eyes. The birds and insects they

attract animate the summer garden,

and there is joy and fascination in

watching the changing occupants and

character of the pond through the

seasons. For older children, there

can be few better introductions to the

natural world than discovering the

extraordinary wild creatures that lurk

in and around garden ponds.

What is the purpose of your

pond?

This leaflet is about creating a pond

for wildlife.

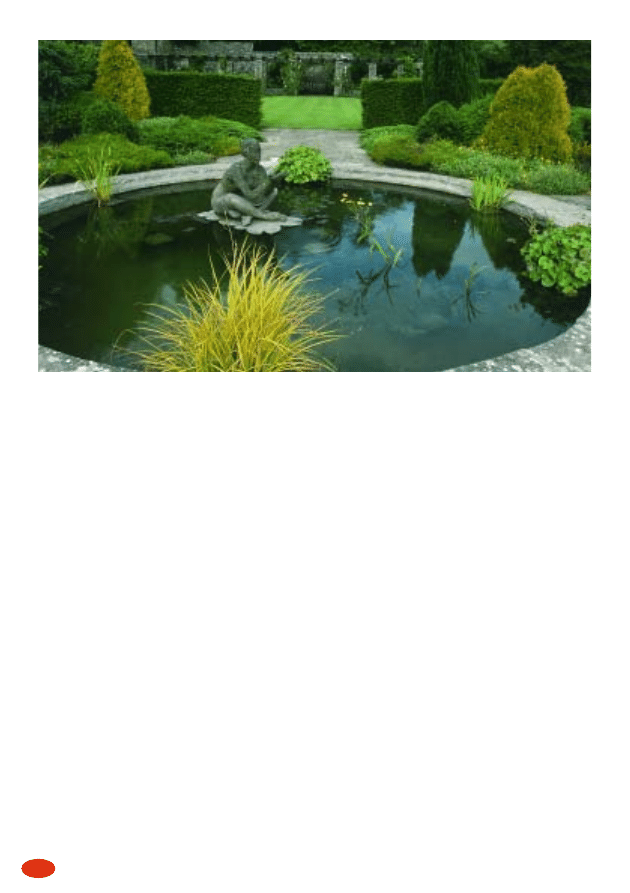

Formal garden ponds, often concrete,

with vertical sides and overhanging

flagstone surrounds, can give a strong

central design to a garden and are

valued for reflections and shape.

However, the steep sides make them

dangerous traps for hedgehogs and

mice. Even cats and dogs may fall in

and be unable to climb out. Frogs

and toads will be trapped in the pond,

and may drown once past the tadpole

stage.

Many people want to keep fish in

their pond. Unfortunately, they may

Formal ponds like this one are not built with nature in mind. Bob Gibbons

dig up bottom-rooted vegetation and

most will eat tadpoles and other pond

animals. If you regularly feed large

numbers of fish, the nutrients added

to the water will encourage green

algae and blanket weed that can

smother the whole pond in a very

short time. Most ponds with large

fish have to have pumps, filters and

aerators. The answer may be to have

one pond for fish, and another,

without fish, for wildlife.

Gardeners usually want to add exotic

plants to their ponds, as to their

flowerbeds. These will not stop

plenty of interesting native animals

colonising their ponds, but plants

long-adapted to conditions here

normally support a greater variety of

invertebrates. Wildlife ponds should

contain mainly native plants, many of

them very beautiful.

Designing your pond

Think carefully where your pond is

to be. Once dug, it can’t be moved!

If it’s in sight of the living room or

kitchen windows, you’ll be able to

watch birds, bats and other visitors

from inside your home. If the pond

is away from the house, it may attract

more timid species, and you can plan

the garden so the pond is a beautiful

surprise in a private corner. Mark

out the outline with canes and see

how it will look before you start

digging.

Aim to have part of the pond in full

sunlight. This allows the water to

warm up quickly in the spring, so

encouraging plant growth. Some

wildlife species prefer shaded water,

but avoid digging a new pond right

by a large tree as you may damage

5

Garden ponds

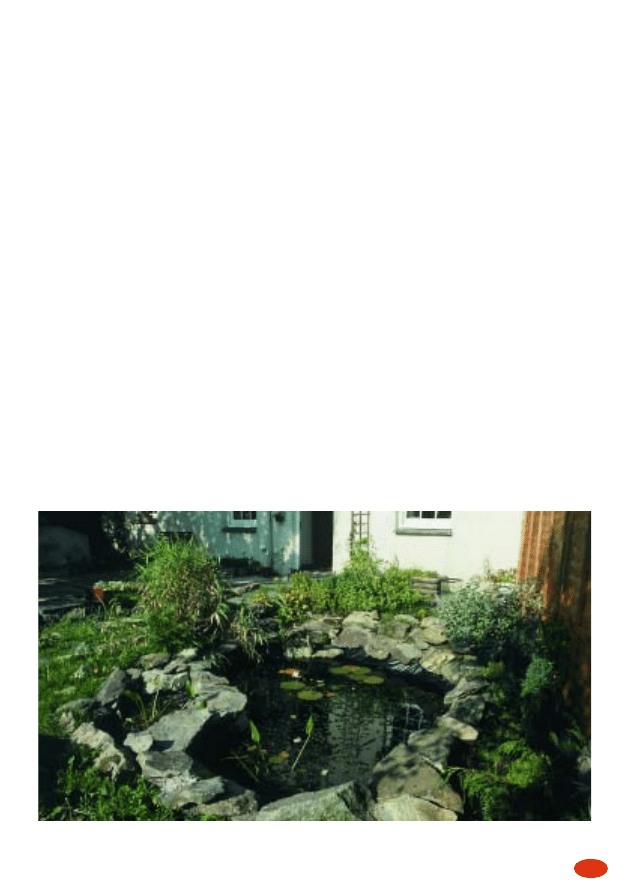

Even very small ponds can be rich in wildlife. Bob Gibbons

6

the roots. Worse, new roots may

penetrate your liner and your pond

may fill with leaves. Think also

about where the water supply is to

come from.

How big should it be? This is up to

you and your budget. Bigger ponds

mean more plant species and a more

varied habitat for animals. But

doubling the dimensions of a pond

increases the liner cost four times,

and creates eight times the volume of

soil to dispose of! The pond should

be in scale with the rest of your

garden: even tiny ponds can hold a

lot of wildlife. If you have the space,

an excellent arrangement for wildlife

is to have one larger pond, several

shallow small pools and a bog garden

area, allowing some pools to become

muddy or dry in the summer. This

variety of habitats will ensure a great

diversity of species.

Garden ponds needn’t be deep.

Most pond animals are found in the

shallowest water – a couple of

centimetres deep. Deep open water

is the most dangerous habitat for

small animals, especially if fish are

present - so maximise the shallows.

For a wildlife pond, 40-50cm is deep

enough, and will mean much less soil

to remove.

A clean water supply is crucial. If

water is contaminated with fertilising

nutrients, you will face a continual

struggle with algal build up. If your

pond is on a slope, it will fill from

rainwater run-off. It is, then, very

important that the ground above the

pond is not artificially fertilised, or

left bare, because nutrients and silt

will wash in.

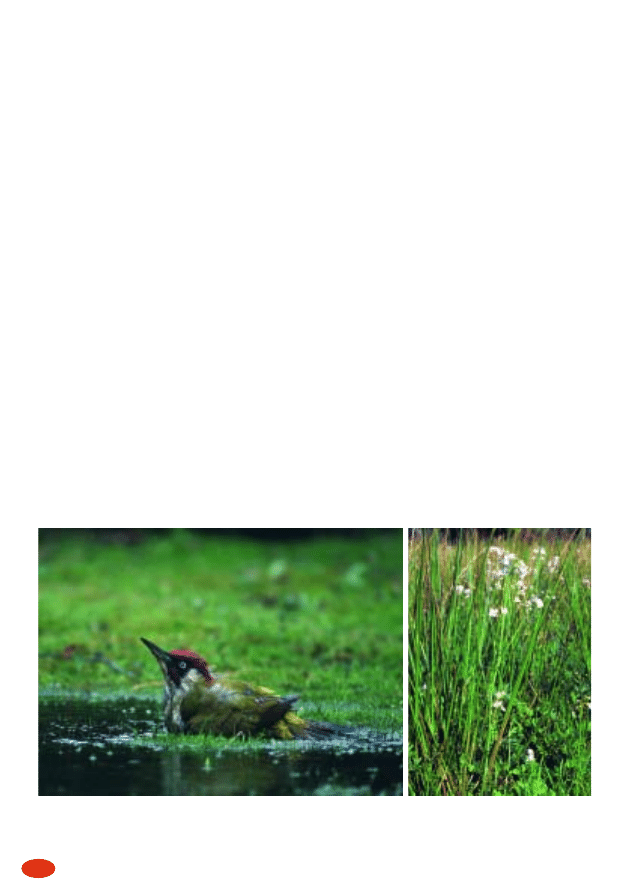

Green woodpecker. Chris Gomersall

The cuckooflower is one of the main food

plants of the orange-tip butterfly.

Chris Gibson/English Nature

Most people fill their ponds with tap

water. This is easy – but rather

wasteful. Tap water also often

contains high quantities of nutrients

that encourage algal growth. The

best possible source is rain water.

Can you site your pond close enough

to the house or a greenhouse or shed,

to be able to siphon water from a

butt? With a little ingenuity, you

may be able to divert water from a

down-pipe directly into the pond.

What shape should the pond be?

Straight edges look unnatural and

should be avoided. The margins are

best for wildlife, so in larger ponds,

try for a wavy-edged oval rather than

a plain circular shape. The most

important design element is the

profile of the sides. Make sure you

leave LOTS of shallow water shelf

area at about 1-15cm deep, where

water plants will flourish. The

margins should be very gently sloping

in at least some places, so the finished

pond merges naturally into the land.

Ideally, create a ‘drawdown’ zone, a

very shallow (5cm or less) area,

which you can cover with gravel and

round stones, to form a beach and

protect the liner in summer. Flooded

in winter, it will partly dry out in

summer, making a fabulous habitat

for many insect species, and a great

bathing area for birds.

Constructing your pond

•

You can make a pond in any

month but early autumn is perhaps

the most practical season, when

the ground is neither too hard, dry

nor cold.

7

Garden ponds

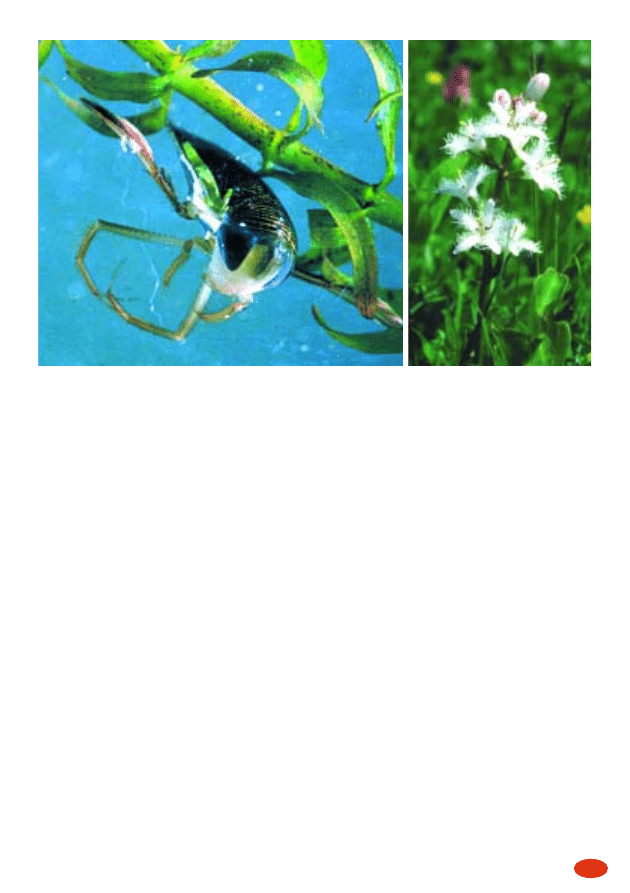

Water boatman Corixa punctata. Bob Gibbons Bogbean. Chris Gibson/English Nature

8

•

You don’t want to put a spade

through an underground pipe!

Check your site plans for evidence

of buried cables or pipes. You can

usually work out where the drains

run by following the inspection

covers.

•

Unless you garden on heavy clay,

you will need a liner. For very

small ponds you can buy pre-

formed liners of plastic or

fibreglass, but some of these don’t

have gently-sloping sides for

animals to escape. Some gardeners

use concrete, but this is a major

undertaking, and can be very

expensive. Most people use a

flexible liner. The best ones are

of butyl or EPDM rubber, and

should be guaranteed for 25 years.

Don’t be tempted by cheap

polythene. This often splits and

punctures within a couple of years.

•

How big a liner do you need?

Measure the greatest length and

width of the hole and then the

depth. Add twice the depth to

both of the other dimensions.

This means that if the length is

3m, the width 2m and the depth

40cm then you need a liner 3.8m

long and 2.8m wide. Allow for

extra liner so that the edges can be

buried in the surrounding soil.

•

When you have dug the hole,

remove all sharp projecting stones

or roots that could puncture the

liner. This is time consuming, but

essential. Locating and repairing

holes later is extremely difficult!

Add a 2.5cm layer of damp sand

as further protection, or use a

fabric layer. Old carpets cut to

shape will do, although they will

rot eventually and become

ineffective. Alternatively, buy

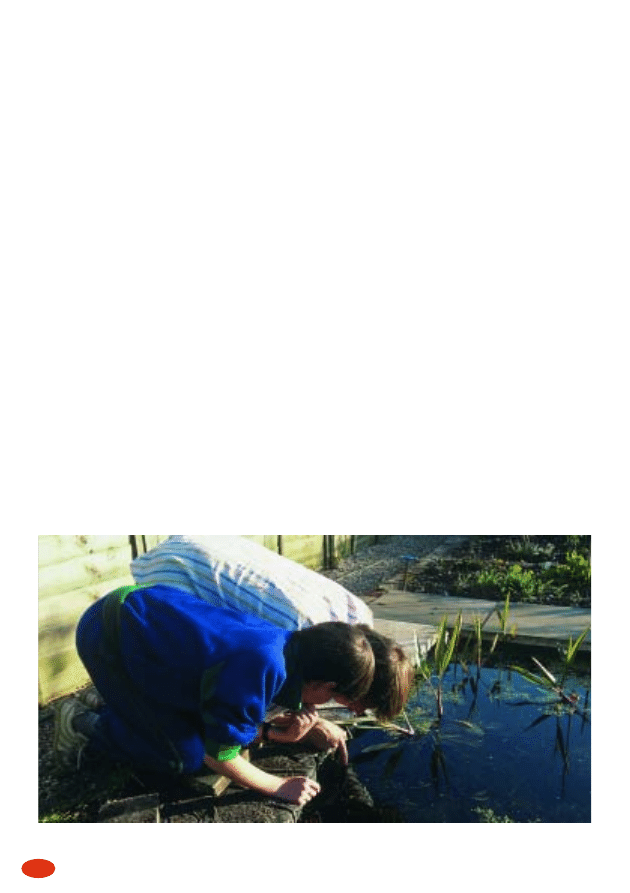

Pond watching. Bob Gibbons

9

Garden ponds

For large and ambitious

projects

Most garden ponds don’t need

planning permission. But if you

are making a very large pond,

if it is close to your boundary

(especially if this is a road or

footpath) or on agricultural

land, contact your planning

officer and ask for advice.

Officers are almost always

helpful and often interested in

ponds themselves.

If you are going to take water

from a river or stream or

discharge water into one, you

will require a licence from the

Environment Agency. In any

case, if your garden is on the

flood plain of a river, you must

consult the Environment

Agency, especially over the

removal of spoil.

Ponds and safety

It is essential to plan your

pond with safety in mind. The

following steps will help to

reduce risks for young

children:

• Keep the pond shallow,

and have wide, very gently-

sloping margins all round.

• Have plenty of marginal

plants, especially where

sides are steeper.

• Don’t let the pond surface

become completely covered

with duckweed or other

floating species, which can

make a pond look like an

area of flat ground and

encourage children (and

dogs) to walk into it.

• Fence the pond securely.

The fence should be at least

110cm high, and with close

vertical posts that can’t

easily be climbed or

squeezed between.

However, make sure that

you can get over or through

the fence immediately in

case a child somehow

manages to get past.

• Strong plastic or metal

meshes to keep children

completely away from the

water are now commercially

available.

These are only really

appropriate for smaller

ponds, and must be

properly installed so

children can’t get under

them. Safe commercial

models are advertised in

garden magazines.

10

do this is to use turf. The grass

will grow into the pond, making it

easy for animals to climb in and

out. Beach areas should be

covered with fine pea gravel (not

sharp edged pieces) and round or

flat stones. As silt collects

between the stones, plants will

start to colonise, so you will

protect the liner and have an

attractive area of habitat as well.

•

You don’t need to spread subsoil

over the pond bottom to encourage

plants. And NEVER put topsoil

into a pond, because you will

bring in unwanted nutrients.

For more details, consult one of the

excellent guides listed at the end of

this leaflet.

Ponds and the rest of your

garden

For many animals, the quality of

habitat outside the pond is just as

important as the water itself. This is

especially true for frogs, toads and

thick polyester matting from

lining suppliers. If you have put

in a beach area, it can be a good

plan to put an extra layer of surplus

trimmed-off liner over the liner on

the beach, to help protect it from

people’s feet and dogs’claws.

•

What to do with the spoil? A

pond two metres by three metres

and 50 cm deep in the middle will

create two cubic metres of loose

soil. If the garden is on a slope,

use some of this to ensure the

sides of the pond are level all

round. Many people use the

surplus soil to make a rockery or a

bank nearby, and these features

can be great winter refuges for

amphibians. Make sure the rocks

come from a sustainable source,

and not from rain-sculptured

limestone, and plant the bank

with native species to provide

cover all year round.

•

Digging is hard but satisfying

work. Hand digging makes it

easier to make modifications and

adjustments as you go along. For

big ponds, if you have vehicle

access, you could hire a mini-

digger or approach a contractor

for a quote. One digger and its

operator can do a huge amount in

a day for a modest rate, but make

sure that you agree plans and

costs in advance.

•

Hide the edge of the liner. For

most of the pool, the best way to

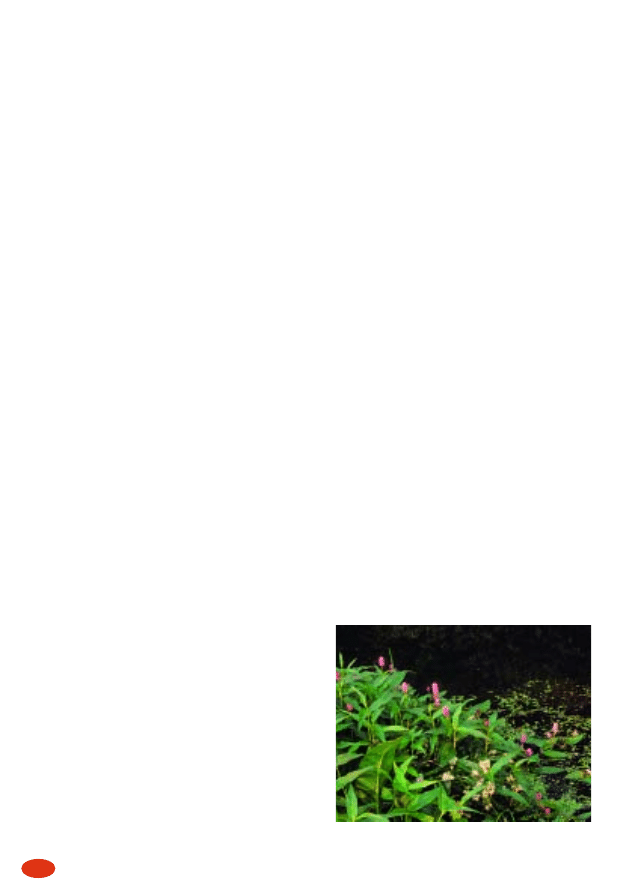

Amphibious bistort. Chris Gibson/English Nature

newts, which spend most of their

lives on land, using the water mainly

to breed. A very formal garden will

offer no support for these

amphibians, which need dense cover

and a plentiful supply of insects and

worms for food. Set aside a

proportion of your garden to help

them, with dense, shady, shrubby

borders and areas of long grass under

trees. Leaving a few areas unkempt

is great for wildlife, and you can

provide over-wintering habitat by

making piles of logs in a quiet

shaded area. Rockeries make good

amphibian habitat too.

Bog gardens are wildlife assets.

Create one when you make your

pond. A bog garden is an area which

is permanently damp, in which

moisture-loving plants can thrive.

Dig a hole about 30cm deep, line it

with butyl and then just refill it with

the extracted soil. A bog garden can

look wonderful next to a pond,

especially if it’s located so that

surplus pond water drains into it

naturally. Dense, lush vegetation in

bog gardens is superb habitat for

newly-emerged young frogs. Bog

gardens also support some very

attractive native flowers.

11

Garden ponds

Smooth newt. Chris Gibson/English Nature

Common toad. Roger Key/English Nature

12

Native plants for your pond

Plants are vital components of your

wildlife pond, providing both habitat

and food for a host of animal species.

Wildlife ponds should have much of

their water surface covered by a good

variety of plants. The more

complicated the underwater

‘architecture’ of roots, stems and

leaves, the more animal species can

co-exist. Very few animals like clear

open water, where they are easily

spotted and eaten by fish.

Although some plants can colonise

ponds very quickly, people will want

to introduce plants of their own choice.

It is important to plant native species,

to which our native animal species

are adapted. The species in the table

(see pages 14-15) are all attractive

and easy to establish.

Water plants fall into four rather

artificial categories. Submerged

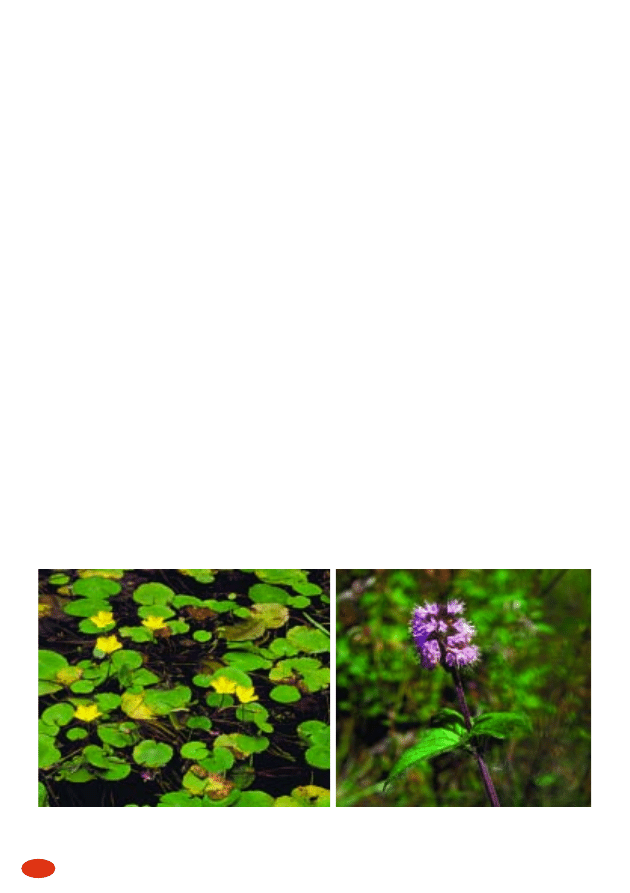

Left: Fringed water-lily. Right: Water mint. Chris Gibson/English Nature

Facing page: Parrot’s feather. This introduced plant can quickly smother even a large pond. Bob Gibbons

plants live with all or most of their

structure underwater. They offer a

very valuable habitat for animal

species in deeper water, and help

mop up surplus nutrients.

Floating leaf plants have their

leaves on the water surface in

summer, and provide shade and

cover. Floating sweet-grass provides

some of the best habitat, and is

excellent for growing over the edge

of the liner, giving a natural look.

Emergent plants include some

attractive species. They prefer

shallow water to root, forming

excellent invertebrate habitat, but

most of their summer growth is out

of the water. They include rushes

and reeds, as well as some very fine

flowering species, but some are just

too vigorous for a small pond.

Marginal and bog plants thrive at

the water’s edge or in wet soil. They

14

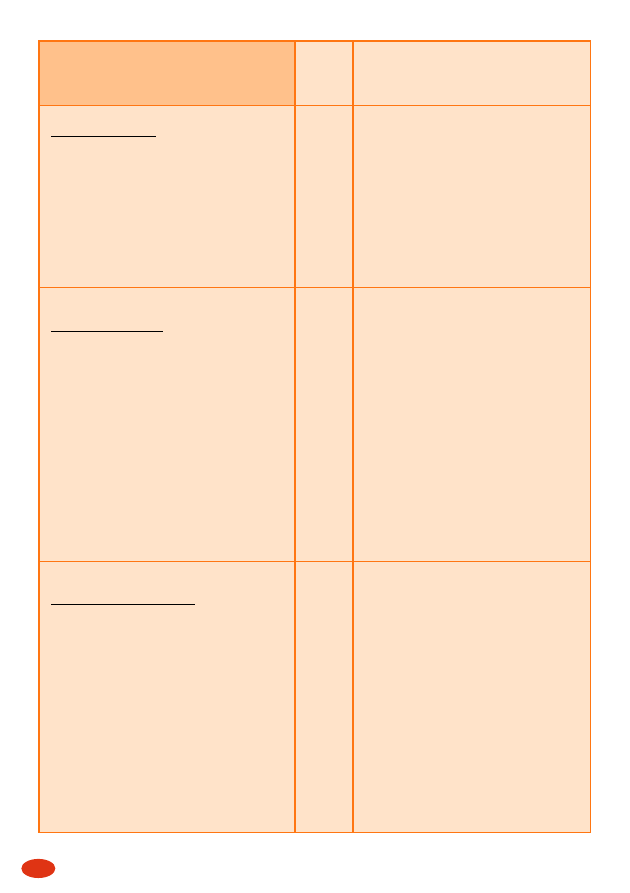

Submerged plants

Curled pondweed (Potamogeton crispus)

1

Also fennel pondweed (P. pectinatus)

Water starwort (Callitriche stagnalis)

1

Floating rosettes of rounded leaves

Rigid hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum)

1

Thickly-tufted plant, vigorous

Water milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum)

1

Caution! NOT Myriophyllum

aquaticum

Water crowfoot (Ranunculus aquatilis)*

1

Partly floating, attractive white

flowers

Floating leaf plants

Broad-leaved pondweed

2

Excellent for habitat

(Potamogeton natans)

Frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae)

1

Attractive white flowers

Floating sweet-grass (Glyceria fluitans)

2-3

Good habitat; plant at the margin to

float out

Yellow water-lily (Nuphar lutea)

2

‘Brandy bottle’: smells of alcohol

Fringed water-lily(Nymphoides peltata)

2

Fringed yellow flowers like buttercup

Water soldier (Stratiotes aloides)

2-3

Impressive spiky plant that sinks in

winter

White water-lily (Nymphaea alba)

3

Beautiful, but too vigorous for most

gardens

Shallow water emergents

Amphibious bistort (Persicaria amphibia)

1

Pink flower stalks, dark green leaves

Water forget-me-not (Myosotis scorpiodes)

1-2

Small, pale blue flowers

Lesser spearwort (Ranunculus flammula)

1

Less spectacular, less invasive than

spearwort

Spearwort (Ranunculus lingua)

2-3

Giant water buttercup, to 90cm high

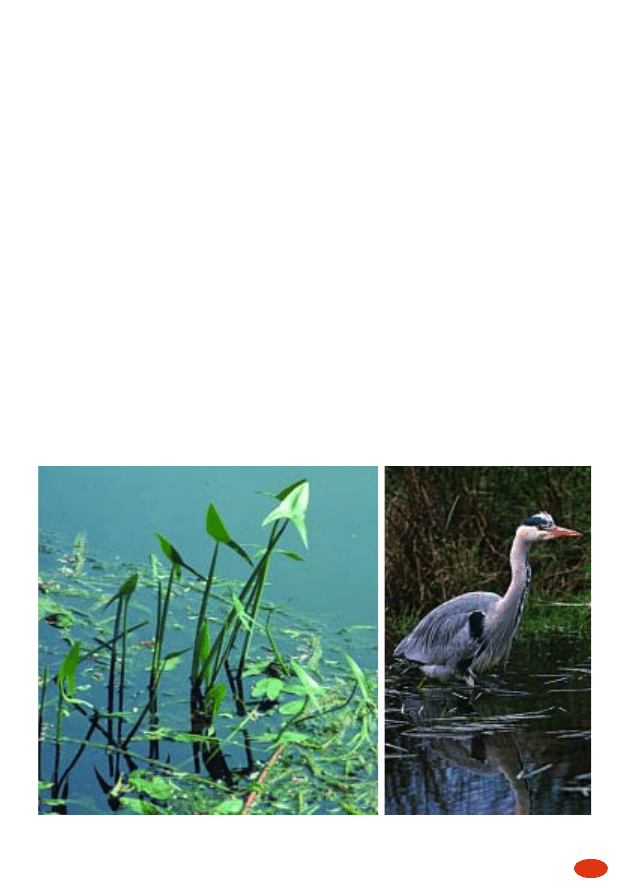

Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia)

1-2

Arrow-head leaves, and small white

flowers

Brooklime (Veronica beccabunga)

1

Blue flowers, straggly, good at the

pond edge

Bogbean (Menyanthes trifoliate)

2-3

Beautiful, invasive but easy to control

Native plants for garden ponds

Suitable

Comments

for

15

Garden ponds

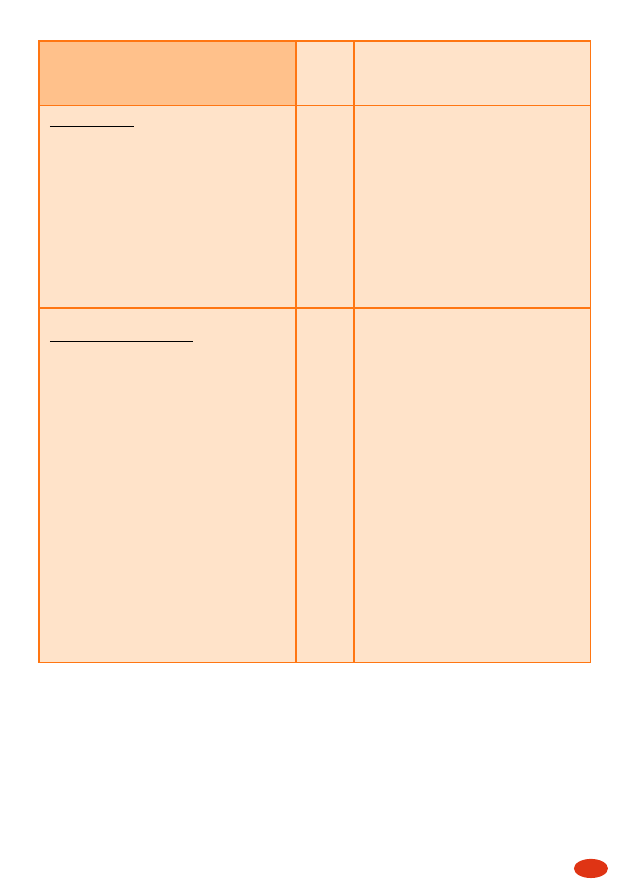

Tall emergents

Flowering rush (Butomus umbellatus)

1-2

Very pretty pink-flowering rush

Branched bur-reed (Sparganum erectum)

3

Unusual spiky flower, semi evergreen

Water mint (Mentha aquatica)

2-3

Pretty, scented leaves, invasive, good

for bees

Water plantain (Alisma plantago-aquatica)

2

Small pink flowers, up to 1m high

Greater pond-sedge (Carex riparia)

2-3

Makes good invertebrate habitat

Lesser bulrush (Typha angustifolia)

2-3

Not for small ponds

Common reed (Phragmites australis)

3

Fine plant, but too big for most ponds

Marginal and bog plants

Bugle (Ajuga repens)

1

Very pretty, deep blue, good for insects

Marsh marigold (Caltha palustris)

1-2

Superb low yellow-flowering plant

Hard rush (Juncus inflexus)

2

Less invasive than soft rush; brown

fruits

Lady’s smock (Cardamine pratensis)

1

Pretty pale purple flowers

Yellow flag (Iris pseudacorus)

2

Superb yellow flowers, red seed

capsules

Ragged robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi)

1

Pretty, delicate pink flower

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

2

Great red-purple spikes

Yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

2

Fine yellow-spiked plant

Marsh woundwort (Stachys palustris)

1-2

Pale purple flower spikes

Great willowherb (Epilobium hirsutum)

3

Tall red-flowered plant, seeds freely

Hemp agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum)

3

Impressive red-purple flowers, seeds

freely

Royal fern (Osmunda regalis)

2-3

Superb native fern, dislikes lime

Suitability

1

Plants appropriate for all ponds, including small ones.

2

Plants rather too big or vigorous for smaller ponds.

3

Plants best reserved for larger ponds only.

*

Most crowfoots do best where the water level drops to expose a

muddy margin on which the seeds germinate.

Native plants for garden ponds

Suitable

Comments

for

include some real beauties. If you’ve

made a bog garden alongside your

pond, you can really go to town with

some stunning effects, while

providing cover for frogs, toads and

newts.

Non-native plants

Ideally, a wildlife pond should only

contain native species. But there are

attractive exotics. These can still

provide cover for wildlife although

they are less likely to be food plants

for insect visitors. Use them

sparingly, letting natives form the

bulk of the planting. Beware, too, of

the problem plants below!

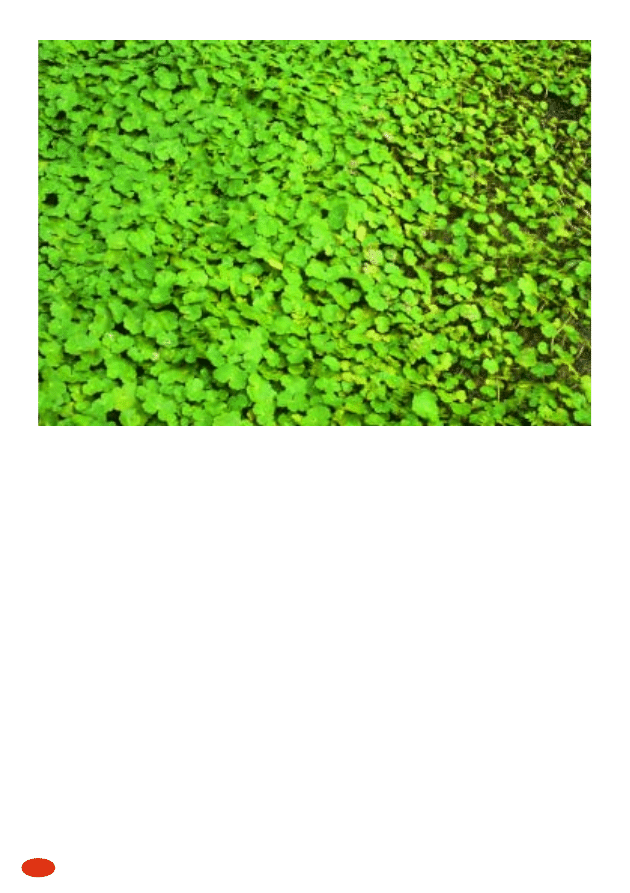

Invasive aliens

The words recall science fiction, but

the danger is real enough. Many

species of imported plants have

escaped from garden ponds into the

wild. A few are causing very serious

ecological damage to ponds and

rivers, through their ability to spread

from small fragments and form dense

choking mats of vegetation. NEVER

plant any of the following aquatic

species in your pond (which they

would take over in no time). Be

careful, because some of these species

are still on sale in garden centres.

•

Fairy or water fern (Azolla

filiculoides)

Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides - a plant to avoid! Bob Gibbons

16

•

New Zealand pygmyweed or

Australian swamp-stonecrop

(Crassula helmsii)

•

Parrot’s-feather (Myriophyllum

aquaticum)

•

Floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle

ranunculoides)

•

Canadian pondweed/Nuttalls

pondweed (Elodea

canadensis/Elodea nuttallii)

•

Curly waterweed (Lagarosiphon

major)

If you think any of these species may

have colonised your pond, don’t

panic, but physically remove all you

can, compost the plants, and keep

doing so until you are sure they have

disappeared.

Under no circumstances dispose of

even a fragment of any of these

plants in the wild!

Where to get plants

It’s illegal to uproot any wild plant

without permission from the

landowner, although you can collect

seed. Your best source may be

17

Garden ponds

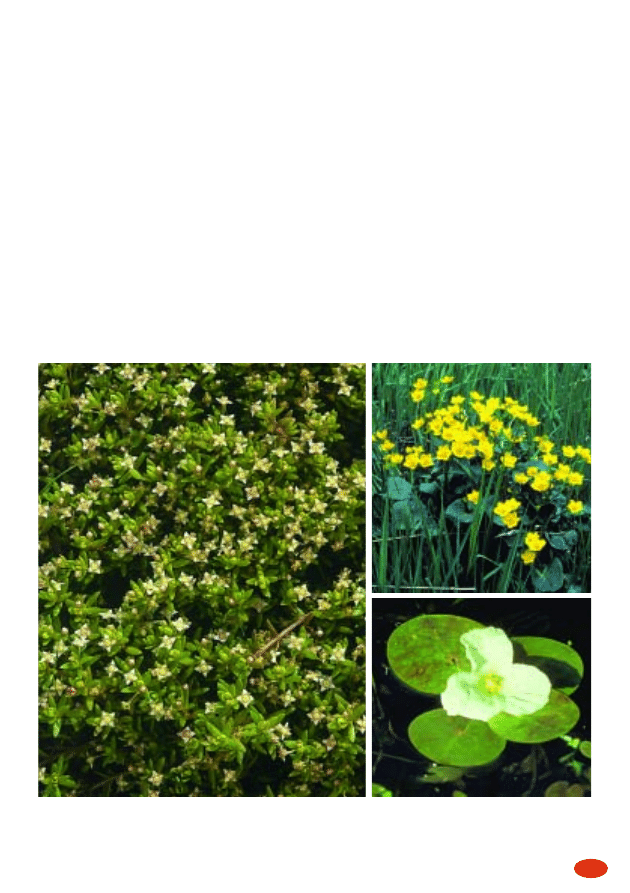

Above: Crassula helmsii - another invasive. Bob Gibbons

Top right: Who needs the cultivated variety when the native one is as beautiful as this? Marsh marigold. Chris Gibson/English Nature

Bottom right: Frogbit. Chris Gibson/English Nature

18

neighbours, friends or a local

gardening club, who will usually be

able to spare cuttings of their own

pond stock, but watch out for

aliens! Often, your local wildlife

trust will be doing management work

on a reserve pond, and may be able

to provide material. There are some

excellent specialist native plant

suppliers, many of them listed on

Flora Locale’s website

www.floralocale.org.

Although many garden centres now

sell native species of pond plants,

these may be ‘improved’ garden

varieties, which are actually of less

use to wildlife. The double-flowered

variety of marsh marigold – Caltha

palustris plena – is one to avoid.

Some centres still sell the invasive

plants mentioned earlier, and their

native stock may be contaminated

with exotic species.

Managing your pond plants

Once established, most water plants

grow extraordinarily fast unless they

are heavily shaded. This means they

compete for space in a small pond

and need management. Some plants

like bogbean send out long runners

and can spread two or three metres in

a season, but are easily reduced

because the brittle stems can be

snapped. Others, like the common

reed – only suitable for the very

largest ponds – form dense, tough,

root masses that need a saw to cut

them back.

Don’t over-manage your pond plants.

Remember, they are home for the

animals in the pond, so leave them

alone during the summer, especially

the grasses growing out from the

lawn with leaves spreading into the

pond margins. It’s best to remove

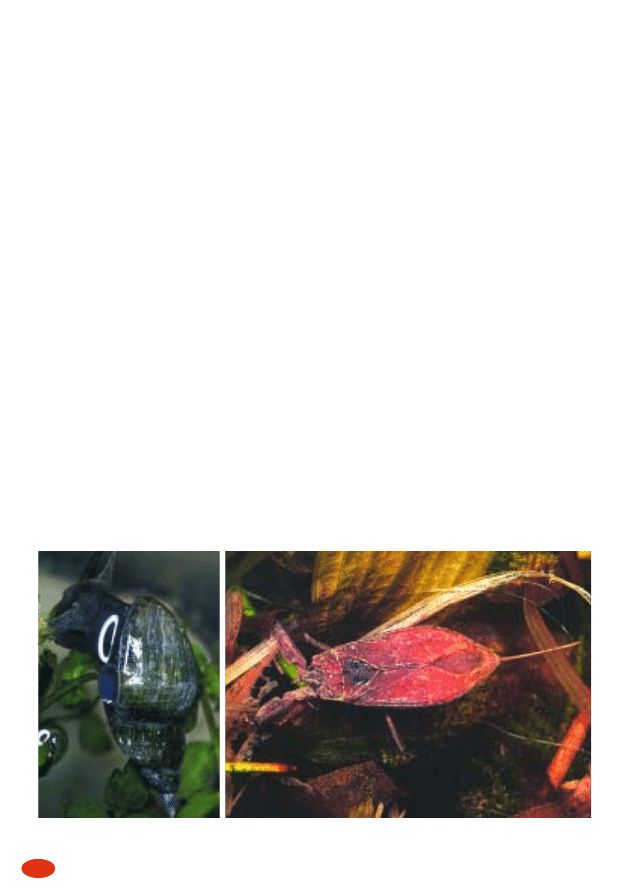

Great pond snail. Garth Coupland Water scorpion. Roger Key/English Nature

excess vegetation in the autumn,

when most amphibians have left the

pond. The submerged plants in

particular may have grown very

strongly. Pile the material by the

pond for 24 hours, so that the tougher

trapped animals have some chance to

escape, but don’t let it begin to rot

there, or nutrients will leach back in

to the pond to cause algal problems.

Pond plants compost quickly and

well. NEVER put any material from

your garden into a wild pond. You

could unknowingly be releasing a

problem species or disease into the

wild.

Animals in your pond

Although plants are beautiful and

valuable in their own right, it is the

animals that provide the greatest

interest for many people. There

could be dozens of species in a good

large garden pond, although some

will be too small to see without a

microscope. Getting animals into

your pond is easy – they find their

own way, provided the water quality

is good and the right plants are

established. Frogs, toads and newts

will discover your new pond quickly,

usually within a season and even in

most heavily urbanised areas. Insects

fly in, and arrive within days. Other

animals, like snails and small

crustaceans find their way somehow.

They travel on the feet of ducks or

bathing birds, or arrive attached to

introduced plants.

Animals play many roles in ponds.

Freshwater shrimps eat organic

debris and rotten vegetation. Water

19

Garden ponds

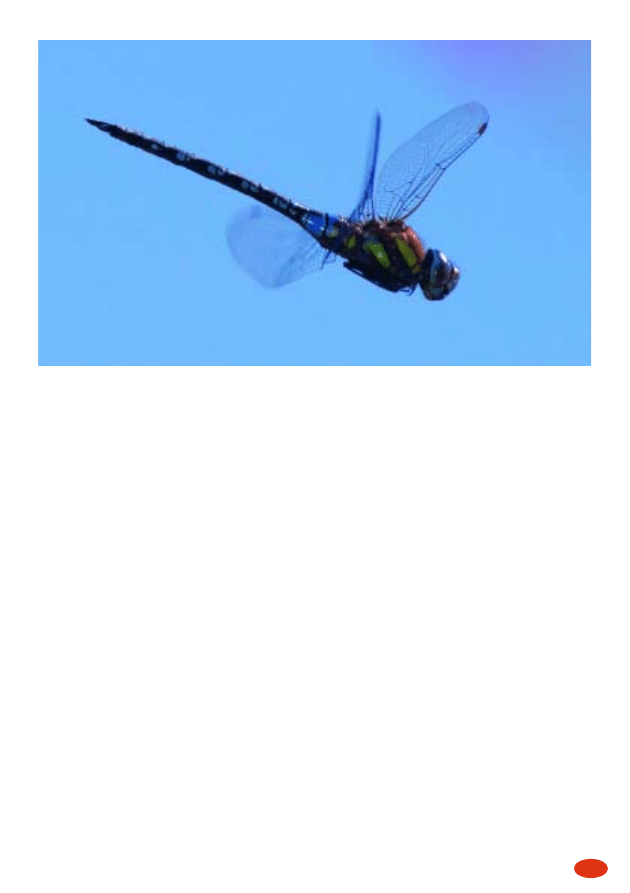

Migrant hawker. Paul Keene

20

fleas and others consume bacteria

and tiny single-celled organisms

living in the bottom sludge or as

plankton in the open water.

Herbivores, including snails,

mayflies, caddis-flies and some

beetles, eat larger algae and plants.

Other species are predators, eating

other animals, and then themselves

being eaten by bigger predators.

Some live all their life in the pond,

while others, like the dragonflies,

stay there for several years as

flightless larvae, before enjoying a

brief period as flying hunting adults

and then returning to the pond to lay

their eggs.

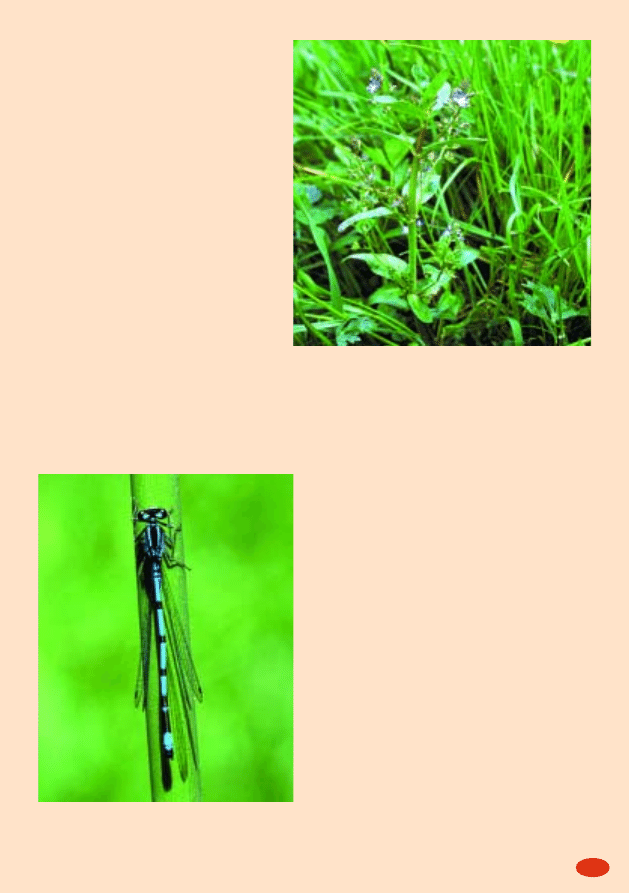

Birds, bats and beasts

Once your pond is established, it will

be a magnet for other animals. Many

garden birds such as blackbirds and

starlings will bathe at the edges, and

others will come down to drink. You

may see house martins and swallows

dipping for drinking water as they fly

or landing to collect mud for their

nests. Garden ponds are often staked

out by herons on the look out for

prey. If you are very lucky, you may

see the whirring blue flight of a

kingfisher, although they rarely find

the small fish they want in garden

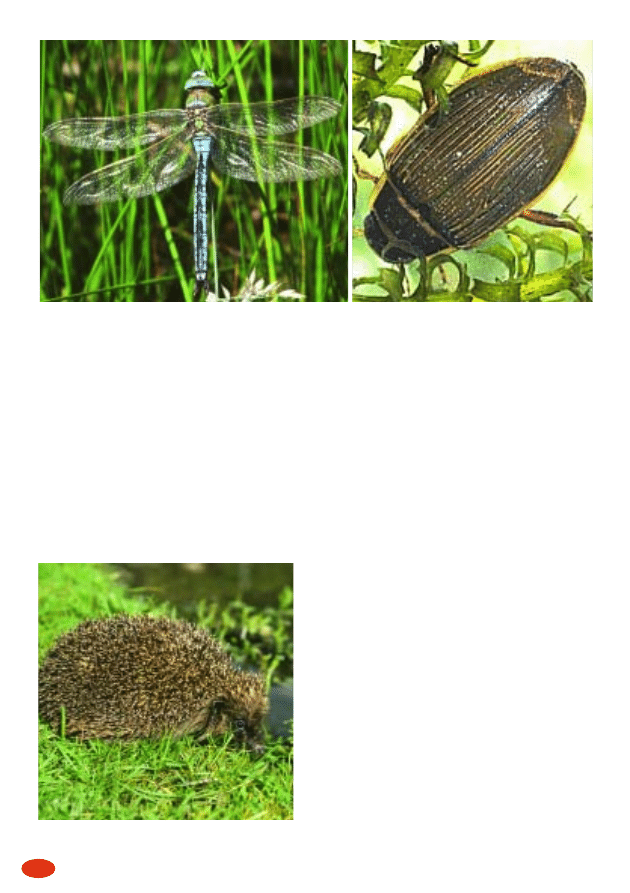

Emperor dragonfly. Dave Sadler

Great diving beetle. Roger Key/English Nature

Thirsty hedgehog. Mike Powles

ponds. Grass snakes may visit or

even take up residence for the summer

if there are plenty of frogs to eat.

If you watch a pond at dusk you are

likely to see bats, probably

pipistrelles, flying over the water,

attracted by emerging insects.

Hedgehogs and even badgers may

stop for a drink, although you will be

fortunate to see them.

Frequently asked questions

about ponds

I already have a garden pond - what

can I do to make it more wildlife

friendly?

Formal ponds are not designed for

wildlife. They tend to have steep

sides without extensive shallow

areas. Concrete fish ponds can be

difficult for animals to escape from

and few have extensive vegetation

cover. To help wildlife, first ensure

that frogs and hedgehogs can leave

the pond, using rocks, stones or

paving slabs as a ramp. Then, create

more shallow habitat. Use sandbags,

recycled bricks or building blocks to

make a retaining wall near the pond

edge, and backfill to near the water

surface, using stones, gravel or

subsoil (NOT topsoil). This will

produce shallow water habitat in

which plants can get established.

Remember that a complicated

underwater ‘architecture’ will

support more animal species.

Finally, do you really want those

fish? If you can bear to give them

away (don’t release them into the

wild!), or just not replace them when

21

Garden ponds

House martins collecting mud for nests. Bob Gibbons

the heron has breakfasted, you’ll

enjoy many more species of animals

in your pond.

Should I put in a fountain and filter to

keep the water clear and oxygenated?

These aren’t needed for a wildlife

pond. Pond filters take out suspended

particles – but also the plankton

essential to a healthy pond. They are

only needed in over-stocked fish

ponds. Fountains help maintain

oxygen levels in fishponds, but oxygen

isn’t a problem in a balanced wildlife

pond. For all that, fountains and

waterfalls can make attractive features

and they do no harm at all to wildlife.

Should I put a net over the pond to

keep leaves out in autumn?

It is difficult to net larger ponds, and it

isn’t necessary unless the pond is right

under a large tree. Sometimes frogs,

grass snakes or birds can get tangled

in, or trapped under nets. A moderate

input of leaves does no harm.

Leaves have little fertilising ability,

but are food for many small

organisms. It is best to use a rake to

remove excessive leaves, and put

them into the compost heap.

I’m finding dead frogs in and around

my pond – what is the problem?

Although most frogs hibernate under

cover on land, a few over-winter in

the bottom of ponds. If the water is

frozen for a long period, some frogs

may be killed by a build up of toxic

decay gases. Bodies may float to the

surface in spring. Occasionally,

female frogs are drowned during the

mating period by over-attentive

males. The most serious cause of

death is the newly imported Red Leg

Disease, a viral complaint that causes

starvation, unpleasant ulceration and

eventually death. If your frogs look

unwell, look up the Froglife website

22

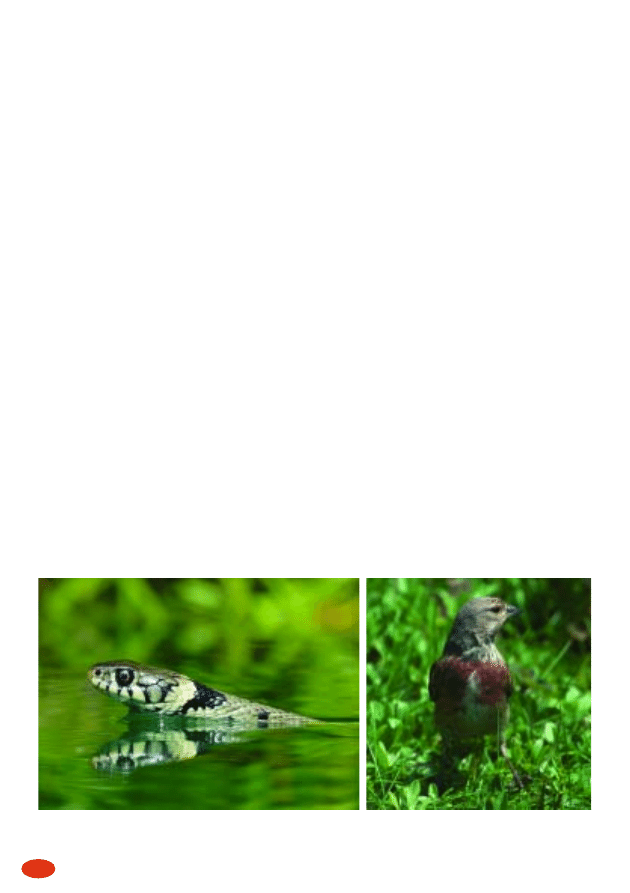

The grass snake is the largest British snake. Harmless to humans, it can

spend much of its time in water, often feeding on frogs. Andy Sands

The linnet is one of many bird species that may drop

in for a quick drink. Chris Gomersall

at www.froglife.org, where you will

find photographs of diseased animals,

and a reporting sheet to help track the

spread of the disease.

There are no frogs or newts in my

pond. Where can I go to get some?

If the conditions are right in the pond

and the garden and if there is another

pond within half a kilometre or so

from which they could migrate,

amphibians will find their own way.

The process can take up to a year

although it is normally much quicker.

Alternatively, bring in a couple of

masses of frogspawn, collected from

other gardens. Ideally, get spawn

from more than one source to avoid

inbreeding – but never from the wild.

Check with the owner that the

“parent” pond doesn’t have a frog

disease problem. Newts are best

introduced as adults but great crested

newts are specially protected and it is

illegal to move them at any stage of

their lifecycle.

I have too much frogspawn in my

pond, where should I put it?

You will have frogspawn according

to the number of frogs surviving in

and around your pond, so there won’t

be ‘too much’. Nearly all tadpoles

die and are eaten each year, the huge

numbers in early spring dwindling to

only a few young froglets by the

summer. Don’t move frogspawn

from your pond to the wild as you

may inadvertently spread diseases.

You will also increase the survival

chances of the remaining eggs and so

may finish up with more, rather than

fewer frogs!

My pond develops a thick layer of

green weed or duckweed. What is

wrong?

Blanket weed and duckweed are

natural components of pond

communities, and both in moderation

are excellent habitat. However,

duckweed can spoil the appearance

of a pond and is almost impossible to

23

Garden ponds

Both photos Bob Gibbons.

However much frogspawn you have in your pond, only

a tiny number of eggs will develop into adult frogs.

24

eradicate. A heavy build-up of

blanket weed or duckweed usually

means there is too much fertility in

the water. The likely reason is

nutrients in the water supply. Using

tap water is often a cause. Another

may be run-off from a fertilised lawn

or flowerbed. If you can’t improve

the water supply, there are other ways

to reduce the problem. Remove all

blanket weed with a lawn rake as it

builds up, and compost it. Duckweed

can be skimmed away. Remove

dying vegetation each autumn, and

cut back the plants hard so they have

plenty of opportunity for new growth

next year. Removing vegetation will

limit nutrient build up, and fast

growing plants next year will

compete for nutrients with the algae.

Immersing small bags of barley straw

is an effective natural control for

blanket weed, although it won’t

provide more than a temporary fix.

My old pond dries out in the summer.

Does it need digging out?

Drying out is common in older ponds

with a build-up of silt and organic

matter, but these old temporary ponds

can be extremely good for wildlife.

They usually hold water for long

enough in spring for successful

amphibian breeding, and acquire a

special set of species which tolerate

partial drying out. Why not dig a

small new pond next to the old one,

to restart the succession process? If

there isn’t space for this, and you

want standing water all year, dig out

only part of the old pond, to preserve

some of the valuable drying habitat.

How can I stop my pond freezing

over in winter?

Frozen water isn’t really a problem

unless you are keeping fish, or if

there are a lot of over-wintering

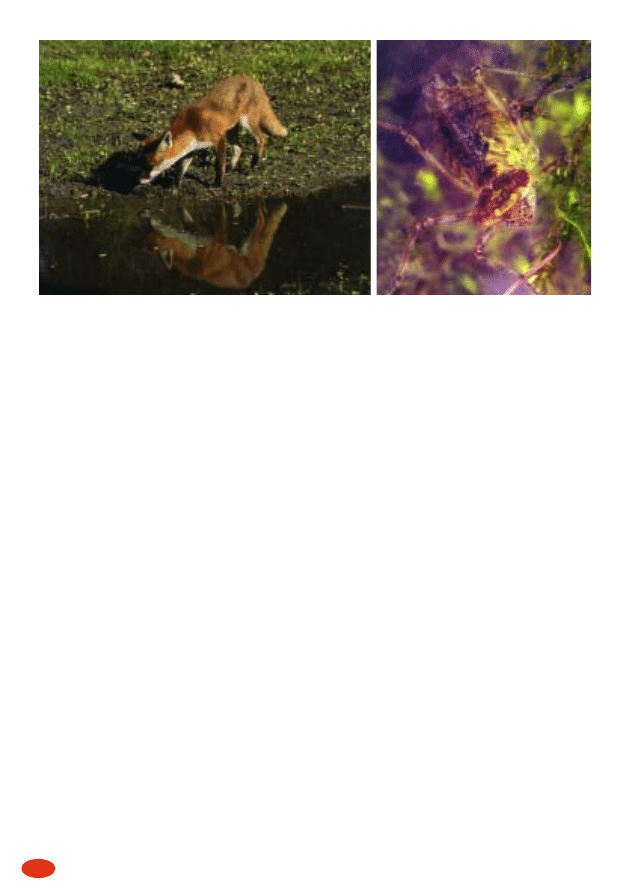

Foxes occasionally visit garden ponds but you may need to be an early

The larvae of dragonflies are fearsome predators,

riser to see one. Mike Lane

taking tadpoles and even small fish.

Roger Key/English Nature

frogs. Even then, you only need a

small hole to allow gases to escape.

Float a large ball on the surface to

keep a vent open. Alternatively,

make a hole by resting a saucepan of

hot water on the ice to melt through.

Never hit the ice with a hammer to

break it as the vibrations can kill

sensitive animals throughout the

pond.

Enjoying your pond

Don’t just spend time working on

your pond – give yourself time to

stop and enjoy it, and the fascinating

creatures it contains. All sorts of

birds visit ponds including pied

wagtails and their beautiful (unfairly

named!) cousins, grey wagtails. In

the early morning you may glimpse a

25

Garden ponds

fox coming to drink. In the heat of

the day, watch the dragonflies and

other insects flying over the pond,

mating and laying eggs. Look out

for dragonfly larvae emerging and

hatching into winged adults - one of

the most extraordinary events you

can witness in a garden. In the

evening, don’t forget to look for bats.

Use the books on ponds and pondlife

listed on page 26 to discover what

species you have in your pond. The

easiest way to study small

invertebrates is to catch them with a

fine kitchen sieve, and study them in

a white plastic tray. Why not build

up a list of species from season to

season and year to year? Eventually,

you may become a pond expert

yourself!

Arrowhead. Chris Gibson/English Nature

The grey heron may not always be a welcome

visitor. Bob Gibbons

26

Finding out more

The Ponds Conservation Trust, 1999.

The Pond Book: A guide to the

Management and Creation of Ponds.

Oxford. Order through

www.pondstrust.org.uk

Louise Bardsley 2003.

The Wildlife Pond Handbook.

New Holland, London.

Peter Robinson, 2003.

RHS Water Gardening.

Dorling Kindersley.

Trevor Beebee 1995.

Pond Life.

Whittet Books.

Lars-Henrik Olsen, Jacob Sunesen

and Bente Vita Pedersen 2001.

Small freshwater creatures.

Oxford University Press.

D.G. Hessayon 1993.

The Rock and Water Garden Expert.

Transworld Publishers Ltd, London.

P.S. Croft 1986.

A Key to the Major Groups of British

Freshwater Invertebrates.

Field Studies Council.

The freshwater name trail,

and Guide to the reptiles and

amphibians of Britain and Ireland.

Field Studies Council AIDGAP

leaflets.

This is one of a series of English

Nature leaflets about gardening with

wildlife in mind. The others are:

Reptiles in your garden; Amphibians

in your garden; Wildlife-friendly

gardening: a general guide;

Composting and peat-free gardening;

Plants for wildlife-friendly

gardening; and Meadows in your

garden. In preparation: Dragonflies

and damselflies in your garden. All

leaflets are free and can be obtained

from the Enquiry Service on

01773 455101 or e-mail:

enquiries@english-nature.org.uk

English Nature also produces an

interactive CD, Gardening with

wildlife in mind. This has detailed

texts and photos of 500 plants and

300 ‘creatures’ and shows how they

are ecologically linked. It costs

£9.99 (add £1.50 postage and

packing) and can be obtained from

The Plant Press, 10 Market Street,

Lewes, BN7 2NB. Alternatively call

John Stockdale on 01273 476151 or

e-mail john@plantpress.com

Small wildlife pond. Bob Gibbons

Useful organisations

Pond Conservation:

The Water Habitats Trust,

BMS,

Oxford Brookes University,

Gipsy Lane,

Oxford OX3 0BP.

www.pondstrust.org.uk

Froglife,

White Lodge,

London Road,

Peterborough PE7 0LG.

www.froglife.org

Flora Locale,

36, Kingfisher Court,

Hambridge Road,

Newbury RG14 5SJ.

www.floralocale.org

The Herpetological Conservation

Trust,

655A Christchurch Road,

Boscombe,

Bournemouth,

Dorset BH1 4AP.

www.herpconstrust.org.uk

The Wildlife Trusts,

The Kiln,

Waterside,

Mather Road,

Newark NG24 1WT.

www.wildlifetrusts.org

Plantlife,

14, Rollestone Street,

Salisbury SP1 1DX.

www.plantlife.org.uk

Royal Horticultural Society,

80, Vincent Square,

London SW1P 2PE.

www.rhs.org.uk

Above: Azure damselfly. Robin Chittenden

Above right: Brooklime. Chris Gibson/English Nature

27

Pond Conservation is the national

charity working to conserve and

protect ponds and small water

bodies through research, training

and practical management and

creation projects.

English Nature is the

Government agency

that champions the

conservation of wildlife

and geology throughout

England.

This is one of a range of

publications published by:

External Relations Team

English Nature

Northminster House

Peterborough PE1 1UA

www.english-nature.org.uk

© English Nature 2005

Printed on Evolution

Satin, 75% recycled

post-consumer waste

paper, elemental chlorine

free.

ISBN 1 85716 856 9

Catalogue code IN16.9

Designed and printed by

Astron Corporate

Solutions.

15M.

Front cover photographs:

Top left: Pond skaters may arrive at

new ponds within days.

Roger Key/English Nature

Bottom left: Broad-bodied chaser.

Paul Keene

Main: The kingfisher is an unlikely

visitor to most ponds but can turn up

almost anywhere near water.

Chris Gomersall

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

(Gardening) Blackberries And Raspberries In Home Gardens

(gardening) Composting and peat free gardening

(gardening) Plants for wildlife friendly gardens

(gardening) Pests and Diseases

(Gardening) Harvesting and storing vegetables

Guidelines for Persons and Organizations Providing Support for Victims of Forced Migration

Body Lang How to Read and Make Body Movements for Maximum Success

How?n We Help the Homeless and Should We Searching for a

Data and memory optimization techniques for embedded systems

!!!2006 biofeedback and or sphincter excerises for tr of fecal incont rev Cochr

13 Interoperability, data discovery and access The e infrastructures for earth sciences resources

Guidelines for Persons and Organizations Providing Support for Victims of Forced Migration

Focus and Concentration Some Tips For Getting Your Players Back

christmas and new year a glossary for esl learners

Artificial Immune Systems and the Grand Challenge for Non Classical Computation

The Art of Seeing Your Psychic Intuition, Third Eye, and Clairvoyance A Practical Manual for Learni

eCourse Wine and Beer Are Good for Us Yes! (Second in a Series)

więcej podobnych podstron