Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à

Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche.

Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents

scientifiques depuis 1998.

Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit :

erudit@umontreal.ca

Article

Lucía Molina et Amparo Hurtado Albir

Meta : journal des traducteurs / Meta: Translators' Journal, vol. 47, n° 4, 2002, p. 498-512.

Pour citer la version numérique de cet article, utiliser l'adresse suivante :

http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/008033ar

Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir.

Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique

d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI

http://www.erudit.org/documentation/eruditPolitiqueUtilisation.pdf

Document téléchargé le 23 December 2009

"Translation Techniques Revisited: A Dynamic and Functionalist Approach"

498

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

Translation Techniques Revisited:

A Dynamic and Functionalist Approach

lucía molina and amparo hurtado albir

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article a pour objectif de cerner la notion de technique de traduction entendue

comme un des instruments d’analyse textuelle qui permet d’étudier le fonctionnement

de l’équivalence par rapport à l’original. Nous rappelons tout d’abord les différentes

définitions et classifications qui ont été proposées ainsi que les confusions termi-

nologiques, conceptuelles et de classification qui en ont découlé. Nous donnons ensuite

notre définition de la technique de traduction en la différenciant de la méthode et de la

stratégie de traduction et proposons une approche dynamique et fonctionnelle de celle-

ci. Pour terminer, nous définissons chacune des diverses techniques de traduction

existantes et en présentons une nouvelle classification. Cette proposition a été appliquée

dans le cadre d’une recherche sur la traduction des éléments culturels dans les traduc-

tions en arabe de

Cent ans de solitude de García Márquez.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to clarify the notion of translation technique, understood as an

instrument of textual analysis that, in combination with other instruments, allows us to

study how translation equivalence works in relation to the original text. First, existing

definitions and classifications of translation techniques are reviewed and terminological,

conceptual and classification confusions are pointed out. Secondly, translation tech-

niques are redefined, distinguishing them from translation method and translation strat-

egies. The definition is dynamic and functional. Finally, we present a classification of

translation techniques that has been tested in a study of the translation of cultural ele-

ments in Arabic translations of

A Hundred Years of Solitude by Garcia Marquez.

MOTS-CLÉS/KEYWORDS

translation technique, translation method, translation strategy, translation equivalence,

functionalism

1. TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES AS TOOL FOR ANALYSIS:

THE EXISTING CONFUSIONS

The categories used to analyze translations allow us to study the way translation

works. These categories are related to text, context and process. Textual categories

describe mechanisms of coherence, cohesion and thematic progression. Contextual

categories introduce all the extra-textual elements related to the context of source

text and translation production. Process categories are designed to answer two basic

questions. Which option has the translator chosen to carry out the translation

project, i.e., which method has been chosen? How has the translator solved the prob-

lems that have emerged during the translation process, i.e., which strategies have

been chosen? However, research (or teaching) requirements may make it important

to consider textual micro-units as well, that is to say, how the result of the translation

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

498

functions in relation to the corresponding unit in the source text. To do this we need

translation techniques. We were made aware of this need in a study of the treatment

of cultural elements in Arabic translations of A Hundred Years of Solitude

1

. Textual

and contextual categories were not sufficient to identify, classify and name the

options chosen by the translators for each unit studied. We needed the category of

translation techniques that allowed us to describe the actual steps taken by the trans-

lators in each textual micro-unit and obtain clear data about the general method-

ological option chosen.

However, there is some disagreement amongst translation scholars about trans-

lation techniques. This disagreement is not only terminological but also conceptual.

There is even a lack of consensus as to what name to give to call the categories,

different labels are used (procedures, techniques, strategies) and sometimes they are

confused with other concepts. Furthermore, different classifications have been pro-

posed and the terms often overlap. This article presents the definition and classifica-

tion of translation techniques that we used in our study of the treatment of cultural

elements in Arabic translations of A Hundred Years of Solitude. We also present a

critical review of earlier definitions and classifications of translation techniques.

2. THE DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO CLASSIFYING

TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES

2.1. Translation Technical Procedures in the Compared Stylistics.

Vinay and Darbelnet’s pioneer work Stylistique comparée du français et de l’anglais

(SCFA) (1958) was the first classification of translation techniques that had a clear

methodological purpose. The term they used was ‘procédés techniques de la traduc-

tion.’ They defined seven basic procedures operating on three levels of style: lexis,

distribution (morphology and syntax) and message. The procedures were classified as

direct (or literal) or oblique, to coincide with their distinction between direct (or

literal) and oblique translation.

Literal translation occurs when there is an exact structural, lexical, even mor-

phological equivalence between two languages. According to the authors, this is only

possible when the two languages are very close to each other. The literal translation

procedures are:

•

Borrowing. A word taken directly from another language, e.g., the English word bull-

dozer has been incorporated directly into other languages.

•

Calque. A foreign word or phrase translated and incorporated into another language,

e.g., fin de semaine from the English weekend.

•

Literal translation. Word for word translation, e.g., The ink is on the table and L’encre est

sur la table.

Oblique translation occurs when word for word translation is impossible. The

oblique translation procedures are:

•

Transposition. A shift of word class, i.e., verb for noun, noun for preposition e.g.,

Expéditeur and From. When there is a shift between two signifiers, it is called crossed

transposition, e.g., He limped across the street and Il a traversé la rue en boitant.

•

Modulation. A shift in point of view. Whereas transposition is a shift between gram-

matical categories, modulation is a shift in cognitive categories. Vinay and Darbelnet

translation techniques revisited

499

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

499

500

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

postulate eleven types of modulation: abstract for concrete, cause for effect, means for

result, a part for the whole, geographical change, etc., e.g., the geographical modulation

between encre de Chine and Indian ink. Intravaia and Scavée (1979) studied this proce-

dure in depth and reached the conclusion that it is qualitatively different from the

others and that the others can be included within it.

•

Equivalence. This accounts for the same situation using a completely different phrase,

e.g., the translation of proverbs or idiomatic expressions like, Comme un chien dans un

jeu de quilles and Like a bull in a china shop.

•

Adaptation. A shift in cultural environment, i.e., to express the message using a differ-

ent situation, e.g. cycling for the French, cricket for the English and baseball for the

Americans.

These seven basic procedures are complemented by other procedures. Except for

the procedures of compensation and inversion, they are all classified as opposing pairs.

•

Compensation. An item of information, or a stylistic effect from the ST that cannot be

reproduced in the same place in the TT is introduced elsewhere in the TT, e.g., the

French translation of I was seeking thee, Flathead. from the Jungle Book Kipling used the

archaic thee, instead of you, to express respect, but none of the equivalent French pro-

noun forms (tu, te, toi) have an archaic equivalent, so the translator expressed the same

feeling by using the vocative, O, in another part of the sentence: En verité, c’est bien toi

que je cherche, O Tête-Plate.

•

Concentration vs. Dissolution. Concentration expresses a signified from the SL with

fewer signifiers in the TL. Dissolution expresses a signified from the SL with more

signifiers in the TL, e.g., archery is a dissolution of the French tir a l’arc.

•

Amplification vs. Economy. These procedures are similar to concentration and dissolu-

tion. Amplification occurs when the TL uses more signifiers to cover syntactic or lexical

gaps. According to Vinay and Darbelnet, dissolution is a question of langue and adap-

tation of parole, e.g., He talked himself out of a job and Il a perdu sa chance pour avoir

trop parlé. The opposite procedure is economy, e.g., We’ll price ourselves out of the mar-

ket and Nous ne pourrons plus vendre si nous sommes trop exigeants.

•

Reinforcement vs. Condensation. These are variations of amplification and economy

that are characteristic of French and English, e.g., English prepositions or conjunctions

that need to be reinforced in French by a noun or a verb: To the station and Entrée de la

gare; Shall I phone for a cab? and Voulez-vous que je téléphone pour faire venir une

voiture? Mallblanc (1968) changed Vinay and Darbelnet’s reinforcement for over-char-

acterization, because he found it was more appropriate for the traits of French and

German. He pointed out that German prepositions, such as, in can be translated into

French as dans le creux de, dans le fond de, or, dans le sein de.

•

Explicitation vs. Implicitation. Explicitation is to introduce information from the ST

that is implicit from the context or the situation, e.g., to make explicit the patient’s sex

when translating his patient into French. Implicitation is to allow the situation to indi-

cate information that is explicit in the ST, e.g., the meaning of sortez as go out or come

out depends on the situation.

•

Generalization vs. Particularization. Generalization is to translate a term for a more

general one, whereas, particularization is the opposite, e.g., the English translation of

guichet, fenêtre or devanture by window is a generalization.

•

Inversion. This is to move a word or a phrase to another place in a sentence or a para-

graph so that it reads naturally in the target language, e.g., Pack separately … for conve-

nient inspection and Pour faciliter la visite de la douane mettre à part ….

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

500

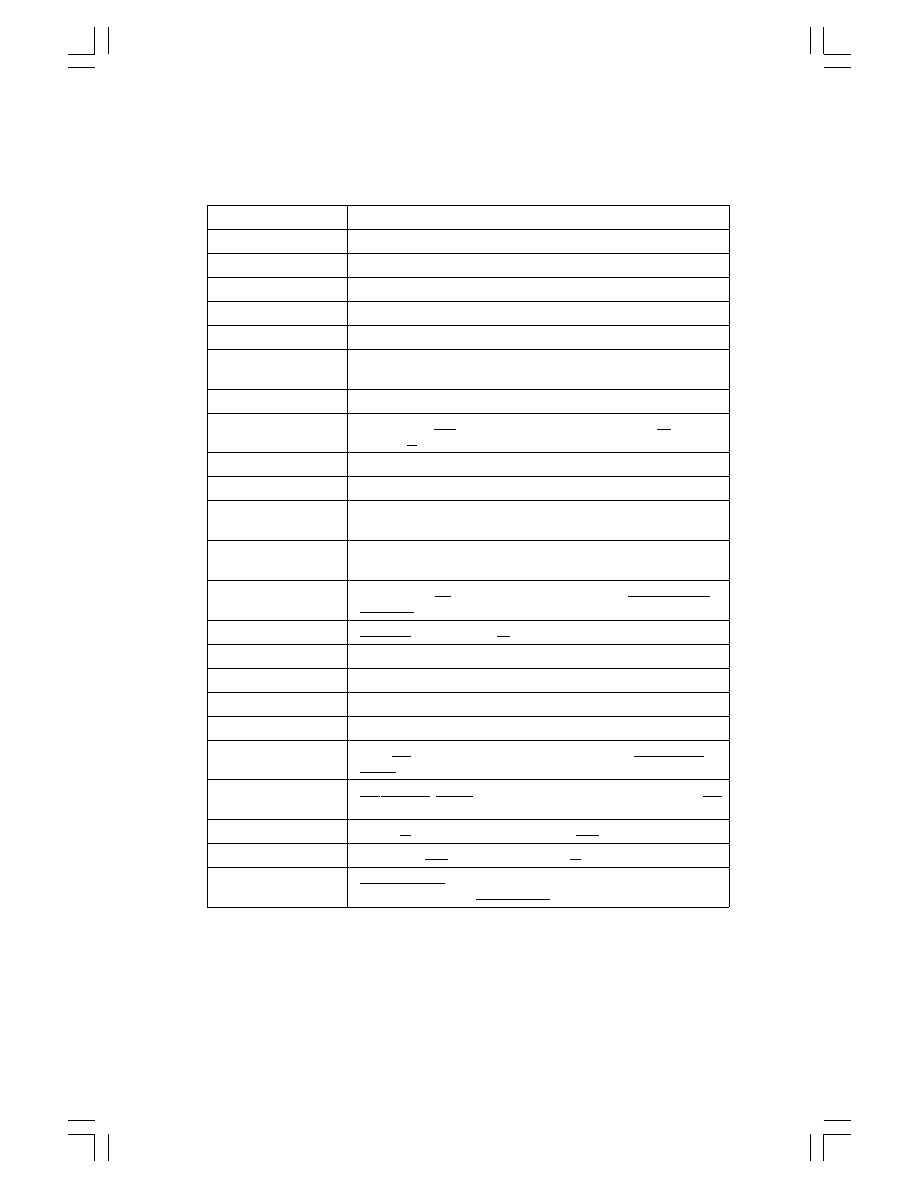

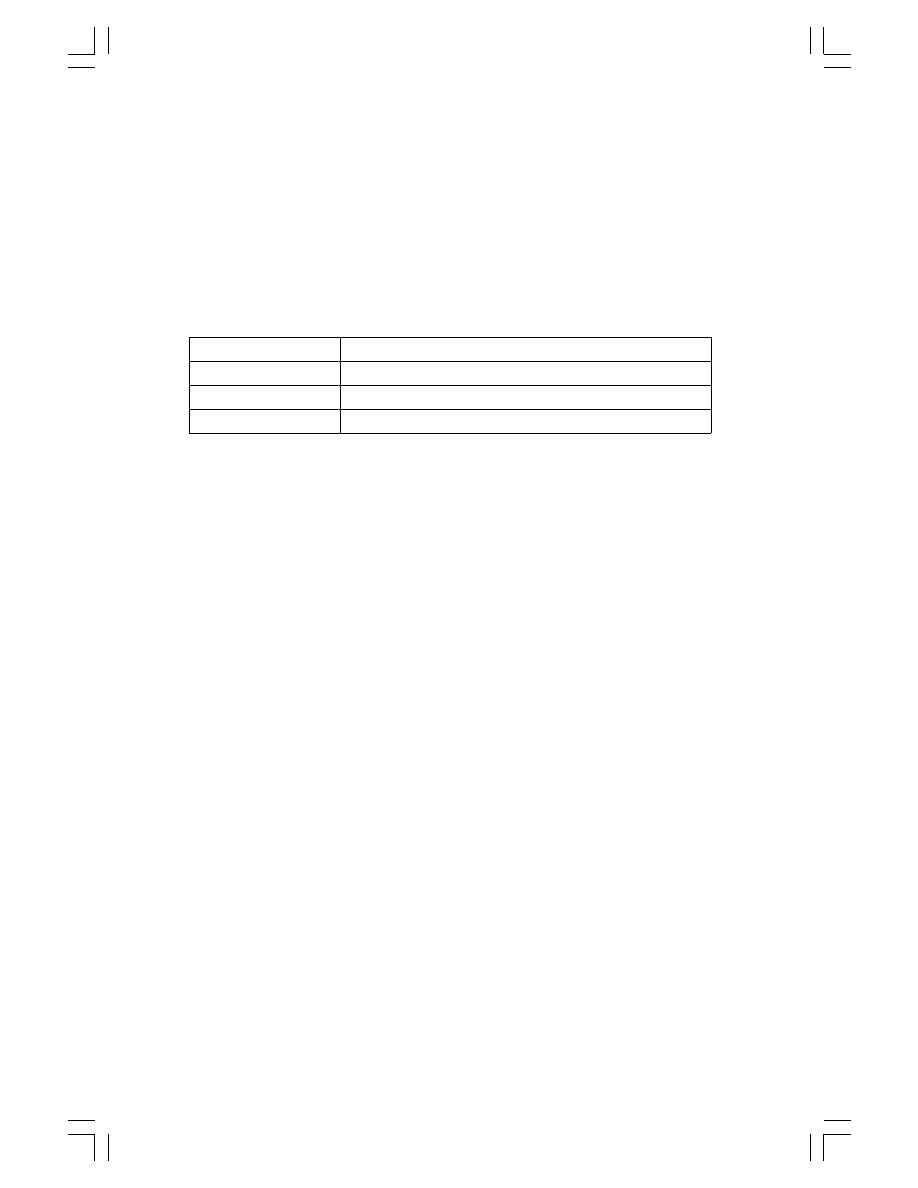

Table 1

Vinay and Darbelnet’s translation procedures

Borrowing

Bulldozer (E)

⇒

Bulldozer (F)

Calque

Fin de semaine (F)

⇒

Week-end (E)

Literal translation

L’encre est sur la table (F)

⇒

The ink is on the table (E)

Transposition

Défense de fumer (F)

⇒

No smoking (E)

Crossed transposition

He limped across the street (E)

⇒

Il a traversé la rue en boitant (F)

Modulation

Encre de Chien (F)

⇒

Indian Ink (E)

Equivalence

Comme un chien dans un jeu de quilles (F)

⇒

Like a bull in a china

shop (E)

Adaptation

Cyclisme (F)

⇒

Cricket (E)

⇒

Baseball (U.S)

Compensation

I was seeking thee, Flathead (E)

⇒

En vérité, c’est bien toi que je

cherche, O Tête-Plate (F)

Dissolution

Tir à l’arc (F)

⇒

Archery (E)

Concentration

Archery (E)

⇒

Tir à l’arc (F)

Amplification

He talked himself out of a job (E)

⇒

Il a perdu sa chance pour

avoir trop parlé (F)

Economy

Nous ne pourrons plus vendre si nous sommes trop exigeants (F)

⇒

We’ll price ourselves out of the market (E)

Reinforcement

Shall I phone for a cab? (E)

⇒

Voulez-vous que je téléphone pour

faire venir une voiture? (F)

Condensation

Entrée de la garde (F)

⇒

To the station (E)

Explicitation

His patient (E)

⇒

Son patient / Son patiente (F)

Implicitation

Go out/ Come out (E)

⇒

Sortez (F)

Generalization

Guichet, fenêtre, devanture (F)

⇒

Window (E)

Particularization

Window (E)

⇒

Guichet, fenêtre, devanture (F)

Articularization

In all this immense variety of conditions,… (E)

⇒

Et cependant,

malgré la diversité des conditions,… (F)

Juxtaposition

Et cependant, malgré la diversité des conditions,… (F)

⇒

In all this

immense variety of conditions,… (E)

Grammaticalization

A man in a blue suit (E)

⇒

Un homme vêtu de blue (F)

Lexicalization

Un homme vêtu de blue (F)

⇒

A man in a blue suit (E)

Inversion

Pack separately […] for convenient inspection (E)

⇒

Pour faciliter

la visite de la douane mettre à part […] (F)

2.2. The Bible translators

From their study of biblical translation, Nida, Taber and Margot concentrate on

questions related to cultural transfer. They propose several categories to be used

translation techniques revisited

501

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

501

502

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

when no equivalence exists in the target language: adjustment techniques, essential

distinction, explicative paraphrasing, redundancy and naturalization.

2.2.1. Techniques of adjustment

Nida (1964) proposes three types: additions, subtractions and alterations. They are

used: 1) to adjust the form of the message to the characteristics of the structure of

the target language; 2) to produce semantically equivalent structures; 3) to generate

appropriate stylistic equivalences; 4) to produce an equivalent communicative effect.

•

Additions. Several of the SCFA procedures are included in this category. Nida lists dif-

ferent circumstances that might oblige a translator to make an addition: to clarify an

elliptic expression, to avoid ambiguity in the target language, to change a grammatical

category (this corresponds to SCFA’s transposition), to amplify implicit elements (this

corresponds to SCFA’s explicitation), to add connectors (this corresponds to SCFA’s

articulation required by characteristics of the TL, etc.). Examples are as follows. When

translating from St Paul’s Epistles, it is appropriate to add the verb write in several

places, even though it is not in the source text; a literal translation of they tell him of her

(Mark I:30) into Mazatec would have to be amplified to the people there told Jesus about

the woman, otherwise, as this language makes no distinctions of number and gender of

pronominal affixes it could have thirty-six different interpretations; He went up to

Jerusalem. There he taught the people some languages require the equivalent of He went

up to Jerusalem. Having arrived there, he taught the people.

•

Subtractions. Nida lists four situations where the translator should use this procedure,

in addition to when it is required by the TL: unnecessary repetition, specified refer-

ences, conjunctions and adverbs. For example, the name of God appears thirty-two

times in the thirty-one verses of Genesis. Nida suggests using pronouns or omitting

God.

•

Alterations. These changes have to be made because of incompatibilities between the

two languages. There are three main types.

1)

Changes due to problems caused by transliteration when a new word is introduced

from the source language, e.g., the transliteration of Messiah in the Loma language,

means death’s hand, so it was altered to Mezaya.

2)

Changes due to structural differences between the two languages, e.g., changes in

word order, grammatical categories, etc. (similar to SCFA’s transposition).

3)

Changes due to semantic misfits, especially with idiomatic expressions. One of the

suggestions to solve this kind of problem is the use of a descriptive equivalent i.e.,

a satisfactory equivalent for objects, events or attributes that do not have a stan-

dard term in the TL. It is used for objects that are unknown in the target culture

(e.g., in Maya the house where the law was read for Synagogue) and for actions that

do not have a lexical equivalent (e.g., in Maya desire what another man has for

covetousness, etc.)

Nida includes footnotes as another adjustment technique and points out that

they have two main functions: 1) To correct linguistic and cultural differences, e.g.,

to explain contradictory customs, to identify unknown geographical or physical

items, to give equivalents for weights and measures, to explain word play, to add

information about proper names, etc.; 2) To add additional information about the

historical and cultural context of the text in question.

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

502

2.2.2. The essential differences

Margot (1979) presents three criteria used to justify cultural adaptation. He refers to

them as the essential differences.

1)

Items that are unknown by the target culture. He suggests adding a classifier next to the

word (as Nida does), e.g., the city of Jerusalem or, by using a cultural equivalent (similar

to the SCFA procedure of adaptation), e.g., in Jesus’ parable (Matthew 7:16) to change

grapes / thorn bushes and figs / thistles for other plants that are more common in the

target culture. However, he warns the reader that this procedure is not always possible.

Taber y Nida (1974) list five factors that have to be taken into account when it is used:

a) the symbolic and theological importance of the item in question, b) its fequency of

use in the Bible, c) its semantic relationship with other words, d) similarities of func-

tion and form between the two items, e) the reader’s emotional response.

2)

The historical framework. Here Margot proposes a linguistic rather than a cultural

translation, on the grounds that historical events cannot be modified.

3)

Adaptation to the specific situation of the target audience. Margot maintains that the

translator’s task is to translate and that it is up to preachers, commentarists and Bible

study groups to adapt the biblical text to the specific situation of the target audience.

He includes footnotes as an aid to cultural adaptation.

2.2.3. The explicative paraphrase

Nida, Taber and Margot coincide in distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate

paraphrasing. The legitimate paraphrase is a lexical change that makes the TT longer

than the ST but does not change the meaning (similar to the SCFA amplification /

dissolution. The illegitimate paraphrase makes ST items explicit in the TT. Nida, Taber

and Margot agree this is not the translator’s job as it may introduce subjectivity.

2.2.4. The concept of redundancy

According to Margot (1979), redundancy tries to achieve symmetry between ST

readers and TT readers. This is done either by adding information (grammatical,

syntactic and stylistic elements, etc.) when differences between the two languages

and cultures make a similar reception impossible for the TT readers, or by suppressing

information when ST elements are redundant for the TT readers, e.g., the Hebrew

expression, answering, said that is redundant in some other languages. This proce-

dure is very close to SCFA’s implicitation / explicitation.

2.2.5. The concept of naturalization

This concept was introduced by Nida (1964) after using the term natural to define

dynamic equivalence (the closest natural equivalent to the source language message).

Nida claims that naturalization can be achieved by taking into account: 1) the source

language and culture understood as a whole; 2) the cultural context of the message;

3) the target audience. This procedure is very close to SCFA’s adaptation.

translation techniques revisited

503

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

503

504

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

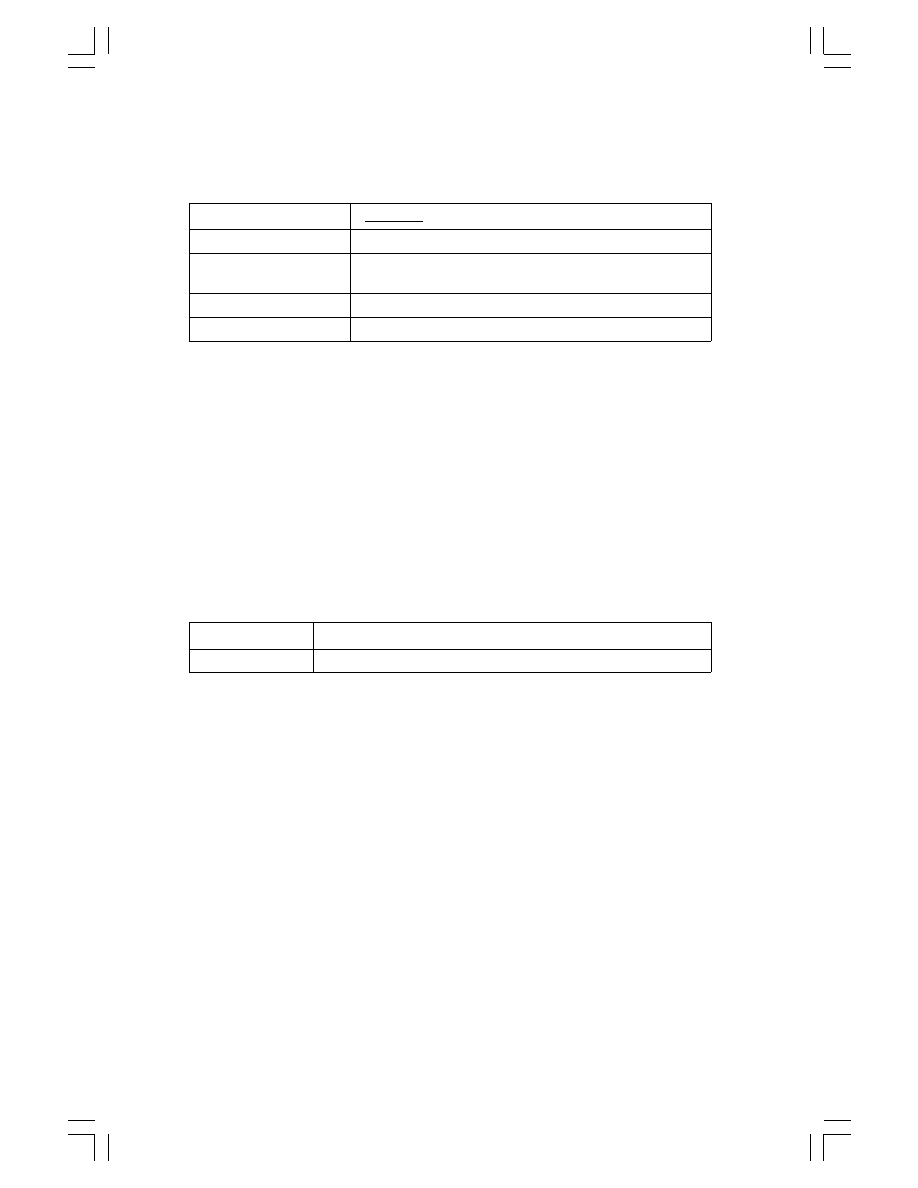

Table 2

The Bible translators’ proposals

Classifier

The city of Jerusalem

Alteration

Messiah (E)

⇒

Mezaya (Loma)

Cultural equivalent

grapes / thorn bushes and figs / thistles

⇒

other plants

that are more common in the target culture

Equivalent description

Synagogue

⇒

The house where the law was read (Maya)

Footnotes

2.3. Vázquez Ayora’s technical procedures

Vázquez Ayora (1977) uses the term operative technical procedures, although he

sometimes refers to them as the translation method. He combines the SCFA pre-

scriptive approach with the Bible translators, descriptive approach and introduces

some new procedures:

•

Omission. This is to omit redundancy and repetition that is characteristic of the SL,

e.g., to translate The committee has failed to act by La comisión no actuó, omitting the

verb to fail and avoiding over-translation: La comisión dejó de actuar.

•

Desplacement and Inversion. Displacement corresponds to SCFA’s inversion, where

two elements change position, e.g., The phone rang and Sonó el teléfono.

Table 3

Vázquez Ayora’s contribution

Omission

The committee has failed to act (E)

⇒

La comisión no actuó (Sp)

Inversion

The phone rang (E) fi Sonó el teléfono (Sp)

2.4. Delisle’s contribution

Delisle (1993) introduces some variations to the SCFA procedures and maintains the

term procedure for Vinay and Darbelnet’s proposals. However, for some other cat-

egories of his own, he introduces a different terminology, e.g., translation strategies,

translation errors, operations in the cognitive process of translating… He lists several

of these categories as contrasting pairs.

In his review of Vinay and Darbelnet, he proposes simplifying the SCFA

dichotomies of reinforcement/condensation and amplification/economy and he

reduces them to a single pair, reinforcement/economy. Reinforcement is to use more

words in the TT than the ST to express the same idea. He distinguishes three types of

reinforcement: 1) dissolution; 2) explicitation (these two correspond to their SCFA

homonyms); and 3) periphrasis (this corresponds to SCFA’s amplification).

Economy is to use fewer words in the TT than the ST to express the same idea. He

distinguishes three types of economy: 1) concentration; 2) implicitation (these two

correspond to their SCFA homonyms and are in contrast to dissolution and

explicitation); and concision (this corresponds to SCFA’s economy and is in contrast

to periphrasis).

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

504

The other categories Delisle introduces are:

•

Addition vs. Omission. He defines them as unjustified periphrasis and concision and

considers them to be translation errors. Addition is to introduce unjustified stylistic

elements and information that are not in the ST, omission is the unjustifiable suppres-

sion of elements in the ST.

•

Paraphrase. This is defined as excessive use of paraphrase that complicates the TT with-

out stylistic or rhetorical justification. It is also classified as a translation error. Delisle’s

paraphrase and addition coincide with Margot’s illegitimate paraphrase.

•

Discursive creation. This is an operation in the cognitive process of translating by

which a non-lexical equivalence is established that only works in context, e.g., In the

world of literature, ideas become cross-fertilized, the experience of others can be usefully

employed to mutual benefit is translated into French as, Dans le domaine des lettres, le

choc des idées se révèle fécond; il devient possible de profiter de l’expérience d’autrui. This

concept is close to Nida’s alterations caused by semantic incompatibilities and translit-

eration.

Table 4

Delisle’s contributions

Dissolution

Reinforcement

Explicitation

Periphrasis (+)

Addition (–)

Paraphrase (–)

Concentration

Economy

Implicitation

Concession (+)

Omission (–)

Discursive creation

Ideas become cross-fertilized (E)

⇒

Le choc des idées

se révèle fécond (F)

2.5. Newmark’s procedures

Newmark (1988) also uses the term procedures to classify the proposals made by the

comparative linguists and by the Bible translators, as well as some of his own. These

are:

•

Recognized translation. This is the the translation of a term that is already official or

widely accepted, even though it may not be the most adequate, e.g., Gay-Lussac’s

Volumengesetz der Gase and Law of combining volumes.

•

Functional equivalent. This is to use a culturally neutral word and to add a specifying

term, e.g., baccalauréat = French secondary school leaving exam; Sejm = Polish parlia-

ment. It is very similar to Margot’s cultural equivalent, and in the SCFA terminology it

would be an adaptation (secondary school leaving exam / parliament) with an

explicitation (French/ Polish).

•

Naturalization. Newmark’s definition is not the same as Nida’s. For Nida, it comes from

transfer (SCFA’s borrowing) and consists of adapting a SL word to the phonetic and

morphological norms of the TL, e.g., the German word Performanz and the English

performance.

translation techniques revisited

505

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

505

506

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

•

Translation label. This is a provisional translation, usually of a new term, and a literal

translation could be acceptable, e.g., Erbschaftssprache or langue d’heritage from the

English heritage language.

Newmark includes the option of solving a problem by combining two or more

procedures (he called these solutions doubles, triples or quadruples). Newmark also

adds synonymy as another category.

Table 5

Newmark’s procedures

Recognized translation

Volumengesetz der Gase (G)

⇒

Law of combining volumes (E)

Functional equivalent

Baccalauréat (F)

⇒

Baccalauréat, secondary school leaving exam (E)

Naturalization

Performance (E)

⇒

Performanz (G)

Translation label

Heritage language (E)

⇒

Langue d’heritage (F)

3. CRITICAL REVIEW OF TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES

As we have seen, there is no general agreement about this instrument of analysis and

there is confusion about terminology, concepts and classification. The most serious

confusions are the following.

3.1. Terminological confusion and over-lapping terms

Terminological diversity and the overlapping of terms make it difficult to use these

terms and to be understood. The same concept is expressed with different names and

the classifications vary, covering different areas of problems. In one classification one

term may over-lap another in a different system of classification. The category itself

is given different names, for example, Delisle uses procedure, translation strategy, etc.

3.2. The confusion between translation process and translation result

This confusion was established by Vinay y Darbelnet’s pioneer proposal, when they

presented the procedures as a description of the ways open to the translator in the

translation process. Nevertheless, the procedures, as they are presented in the SCFA

do not refer to the process followed by the translator, but to the final result. The

confusion has persisted and translation techniques have been confused with other

translation categories: method and strategies.

In some of the proposals there is a conceptual confusion between techniques

and translation method. Vinay y Darbelnet introduced the confusion by dividing the

procedures following the traditional methodological dichotomy between literal and

free translation. As they worked with isolated units they did not distinguish between

categories that affect the whole text and categories that refer to small units. Further-

more, the subtitle of their book, Méthode de traduction, caused even more confusion.

In our opinion (see 4.1.), a distinction should bemade between translation method,

that is part of the process, a global choice that affects the whole translation, and trans-

lation techniques that describe the result and affect smaller sections of the translation.

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

506

The SCFA use of the term procedures created confusion wirh another category

related to the process: translation strategies. Procedures are related to the distinction

between declarative knowledge (what you know) and procedural or operative knowl-

edge (know-how) (Anderson 1983). Procedures are an important part of procedural

knowledge, they are related to knowing how to do something, the ability to organise

actions to reach a specific goal (Pozo, Gonzalo and Postigo 1993). Procedures include

the use of simple techniques and skills, as well as expert use of strategies (Pozo y

Postigo 1993). Strategies are an essential element in problem solving. Therefore, in

relation to solving translation problems, we think a distinction should be made

between techniques and strategies. Techniques describe the result obtained and can

be used to classify different types of translation solutions. Strategies are related to the

mechanisms used by translators throughout the the whole translation process to find

a solution to the problems they find. The technical procedures (the name itself is

ambiguous) affect the results and not the process, so they should be distinguished

from strategies. We propose they should be called translation techniques.

3.3. The confusion between issues related to language pairs and text pairs

Vinay y Darbelnet’s original proposal also led to a confusion between language prob-

lems and text problems. Their work was based on comparative linguistics and all the

examples used to illustrate their procedures were decontextualized. In addition, be-

cause they gave a single translation for each linguistic item, the result was pairs of

fixed equivalences. This led to a confusion between comparative linguistic phenom-

ena (and the categories needed to analyse their similarities and differences) and phe-

nomena related to translating texts (that need other categories).

The use of translation techniques following the SCFA approach is limited to the

classification of differences between language systems, not the textual solutions

needed for translation. For example, SCFA’s borrowing, transposition and inversion,

or, Vázquez Ayora’s omission, should not be considered as translation techniques.

They are not a textual option open to the translator, but an obligation imposed by

the characteristics of the language pair.

4. A DEFINITION OF TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES

Our proposal is based on two premises: 1) the need to distinguish between method,

strategy and technique; 2) the need for an dynamic and functional concept of trans-

lation techniques.

4.1. The need to distinguish between method, strategy and technique

We think that translation method, strategies and techniques are essentially different

categories. (Hurtado 1996).

4.1.1. Translation method and translation techniques

Translation method refers to the way a particular translation process is carried out in

terms of the translator’s objective, i.e., a global option that affects the whole text.

There are several translation methods that may be chosen, depending on the aim of

translation techniques revisited

507

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

507

508

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

the translation: interpretative-communicative (translation of the sense), literal (lin-

guistic transcodification), free (modification of semiotic and communicative catego-

ries) and philological (academic or critical translation) (see Hurtado Albir 1999: 32).

Each solution the translator chooses when translating a text responds to the glo-

bal option that affects the whole text (the translation method) and depends on the

aim of the translation. The translation method affects the way micro-units of the text

are translated: the translation techniques. Thus, we should distinguish between the

method chosen by the translator, e.g., literal or adaptation, that affects the whole text,

and the translation techniques, e.g., literal translation or adaptation, that affect micro-

units of the text.

Logically, method and functions should function harmoniously in the text. For

example, if the aim of a translation method is to produce a foreignising version, then

borrowing will be one of the most frequently used translation techniques. (Cf. This

has been shown in Molina (1998), where she analyses the three translations into

Arabic of García Marquez’s A Hundred Years of Solitude. Each translation had

adopted a different translation method, and the techniques were studied in relation

to the method chosen).

4.1.2. Translation strategy and translation techniques

Whatever method is chosen, the translator may encounter problems in the transla-

tion process, either because of a particularly difficult unit, or because there may be a

gap in the translator’s knowledge or skills. This is when translation strategies are

activated. Strategies are the procedures (conscious or unconscious, verbal or non-

verbal) used by the translator to solve problems that emerge when carrying out the

translation process with a particular objective in mind (Hurtado Albir 1996, 1999).

Translators use strategies for comprehension (e.g., distinguish main and secondary

ideas, establish conceptual relationships, search for information) and for reformula-

tion (e.g., paraphrase, retranslate, say out loud, avoid words that are close to the

original). Because strategies play an essential role in problem solving, they are a cen-

tral part of the subcompetencies that make up translation competence.

Strategies open the way to finding a suitable solution for a translation unit. The

solution will be materialized by using a particular technique. Therefore, strategies

and techniques occupy different places in problem solving: strategies are part of the

process, techniques affect the result. However, some mechanisms may function both

as strategies and as techniques. For example, paraphrasing can be used to solve prob-

lems in the process (this can be a reformulation strategy) and it can be an amplifica-

tion technique used in a translated text (a cultural item paraphrased to make it

intelligible to TT readers). This does not mean that paraphrasing as a strategy will

necessarily lead to using an amplification technique. The result may be a discursive

creation, an equivalent established expression, an adaptation, etc.

4.2. A dynamic and functional approach to translation techniques

In our opinion, most studies of translation techniques do not seem to fit in with the

dynamic nature of translation equivalence. If we are to preserve the dynamic dimen-

sion of translation, a clear distinction should be made between the definition of a

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:15 PM

508

technique and its evaluation in context. A technique is the result of a choice made by

a translator, its validity will depend on various questions related to the context, the

purpose of the translation, audience expectations, etc.

If a technique is evaluated out of context as justified, unjustified or erroneous,

this denies the functional and dynamic nature of translation. A technique can only

be judged meaningfully when it is evaluated within a particular context. Therefore,

we do not consider it makes sense to evaluate a technique by using different termi-

nology, two opposing pairs (one correct and the other incorrect), e.g., Delisle’s

explicitation/implicitation and addition/omission.

Translation techniques are not good or bad in themselves, they are used func-

tionally and dynamically in terms of:

1)

The genre of the text (letter of complaint, contract, tourist brochure, etc.)

2)

The type of translation (technical, literary, etc.)

3)

The mode of translation (written translation, sight translation, consecutive interpret-

ing, etc.)

4)

The purpose of the translation and the characteristics of the translation audience

5)

The method chosen (interpretative-communicative, etc.)

4.3. Definition of translation techniques

In the light of the above, we define translation techniques as procedures to analyse

and classify how translation equivalence works. They have five basic characteristics:

1)

They affect the result of the translation

2)

They are classified by comparison with the original

3)

They affect micro-units of text

4)

They are by nature discursive and contextual

5)

They are functional

Obviously, translation techniques are not the only categories available to analyse

a translated text. Coherence, cohesion, thematic progression and contextual dimen-

sions also intervene in the analysis.

5. A PROPOSAL TO CLASSIFY TRANSLATION TECHNIQUES

Our classification of translation techniques is based on the following criteria:

1)

To isolate the concept of technique from other related notions (translation strategy,

method and error).

2)

To include only procedures that are characteristic of the translation of texts and not

those related to the comparison of languages.

3)

To maintain the notion that translation techniques are functional. Our definitions do

not evaluate whether a technique is appropriate or correct, as this always depends on its

situation in text and context and the translation method that has been chosen.

4)

In relation to the terminology, to maintain the most commonly used terms.

5)

To formulate new techniques to explain mechanisms that have not yet been described.

The following techniques are included in this proposal

2

:

•

Adaptation. To replace a ST cultural element with one from the target culture, e.g., to

change baseball, for fútbol in a translation into Spanish. This corresponds to SCFA’s

adaptation and Margot’s cultural equivalent.

translation techniques revisited

509

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:16 PM

509

510

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

•

Amplification. To introduce details that are not formulated in the ST: information,

explicative paraphrasing, e.g., when translating from Arabic (to Spanish ) to add the

Muslim month of fasting to the noun Ramadan. This includes SCFA’s explicitation,

Delisle’s addition, Margot’s legitimate and illigitimate paraphrase, Newmark’s explica-

tive paraphrase and Delisle’s periphrasis and paraphrase. Footnotes are a type of ampli-

fication. Amplification is in opposition to reduction.

•

Borrowing. To take a word or expression straight from another language. It can be pure

(without any change), e.g., to use the English word lobby in a Spanish text, or it can be

naturalized (to fit the spelling rules in the TL), e.g., gol, fútbol, líder, mitin. Pure borrowing

corresponds to SCFA’s borrowing. Naturalized borrowing corresponds to Newmark’s

naturalization technique.

•

Calque. Literal translation of a foreign word or phrase; it can be lexical or structural,

e.g., the English translation Normal School for the French École normale. This corre-

sponds to SCFA’s acceptation.

•

Compensation. To introduce a ST element of information or stylistic effect in another

place in the TT because it cannot be reflected in the same place as in the ST. This

corresponds to SCFA’s conception.

•

Description. To replace a term or expression with a description of its form or/and func-

tion, e.g., to translate the Italian panettone as traditional Italian cake eaten on New Year’s

Eve.

•

Discursive creation. To establish a temporary equivalence that is totally unpredictable

out of context, e.g., the Spanish translation of the film Rumble fish as La ley de la calle.

This coincides with Delisle’s proposal.

•

Established equivalent. To use a term or expression recognized (by dictionaries or lan-

guage in use) as an equivalent in the TL, e.g., to translate the English expression They

are as like as two peas as Se parecen como dos gotas de agua in Spanish. This corresponds

to SCFA’s equivalence and literal translation.

•

Generalization. To use a more general or neutral term, e.g., to translate the French

guichet, fenêtre or devanture, as window in English. This coincides with SCFA’s accepta-

tion. It is in opposition to particularization.

•

Linguistic amplification. To add linguistic elements. This is often used in consecutive

interpreting and dubbing, e.g., to translate the English expression No way into Spanish

as De ninguna de las maneras instead of using an expression with the same number of

words, En absoluto. It is in opposition to linguistic compression.

•

Linguistic compression. To synthesize linguistic elements in the TT. This is often used

in simultaneous interpreting and in sub-titling, e.g., to translate the English question

Yes, so what? With ¿Y?, in Spanish, instead of using a phrase with the same number of

words, ¿Sí, y qué?. It is in opposition to linguistic amplification.

•

Literal translation. To translate a word or an expression word for word, e.g., They are as

like as two peas as Se parecen como dos guisante, or, She is reading as Ella está leyendo. In

contrast to the SCFA definition, it does not mean translating one word for another. The

translation of the English word ink as encre in French is not a literal translation but an

established equivalent. Our literal translation corresponds to Nida’s formal equivalent;

when form coincides with function and meaning, as in the second example. It is the

same as SCFA’s literal translation.

•

Modulation. To change the point of view, focus or cognitive category in relation to the

ST; it can be lexical or structural, e.g., to translate

as you are going to have a

child, instead of, you are going to be a father. This coincides with SCFA’s acceptation.

•

Particularization. To use a more precise or concrete term, e.g., to translate window in

English as guichet in French. This coincides with SCFA’s acceptation. It is in opposition

to generalization.

•

Reduction. To suppress a ST information item in the TT, e.g., the month of fasting in

opposition to Ramadan when translating into Arabic. This includes SCFA’s and

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:16 PM

510

Delisle’s implicitation Delisle’s concision, and Vázquez Ayora’s omission. It is in oppo-

sition to amplification.

•

Substitution (linguistic, paralinguistic). To change linguistic elements for paralinguistic

elements (intonation, gestures) or vice versa, e.g., to translate the Arab gesture of put-

ting your hand on your heart as Thank you. It is used above all in interpreting.

•

Transposition. To change a grammatical category, e.g., He will soon be back translated

into Spanish as No tardará en venir, changing the adverb soon for the verb tardar,

instead of keeping the adverb and writing: Estará de vuelta pronto.

•

Variation. To change linguistic or paralinguistic elements (intonation, gestures) that

affect aspects of linguistic variation: changes of textual tone, style, social dialect, geo-

graphical dialect, etc., e.g., to introduce or change dialectal indicators for characters

when translating for the theater, changes in tone when adapting novels for children, etc.

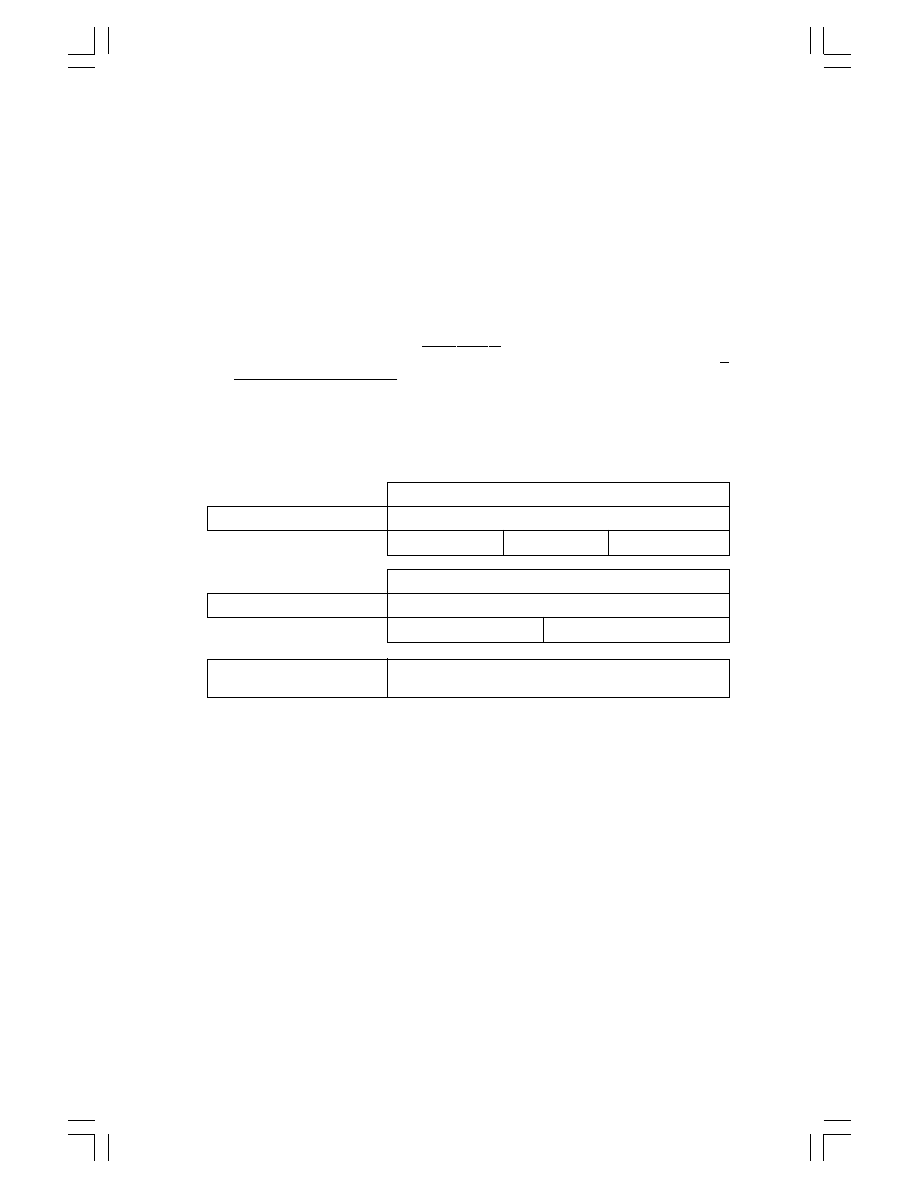

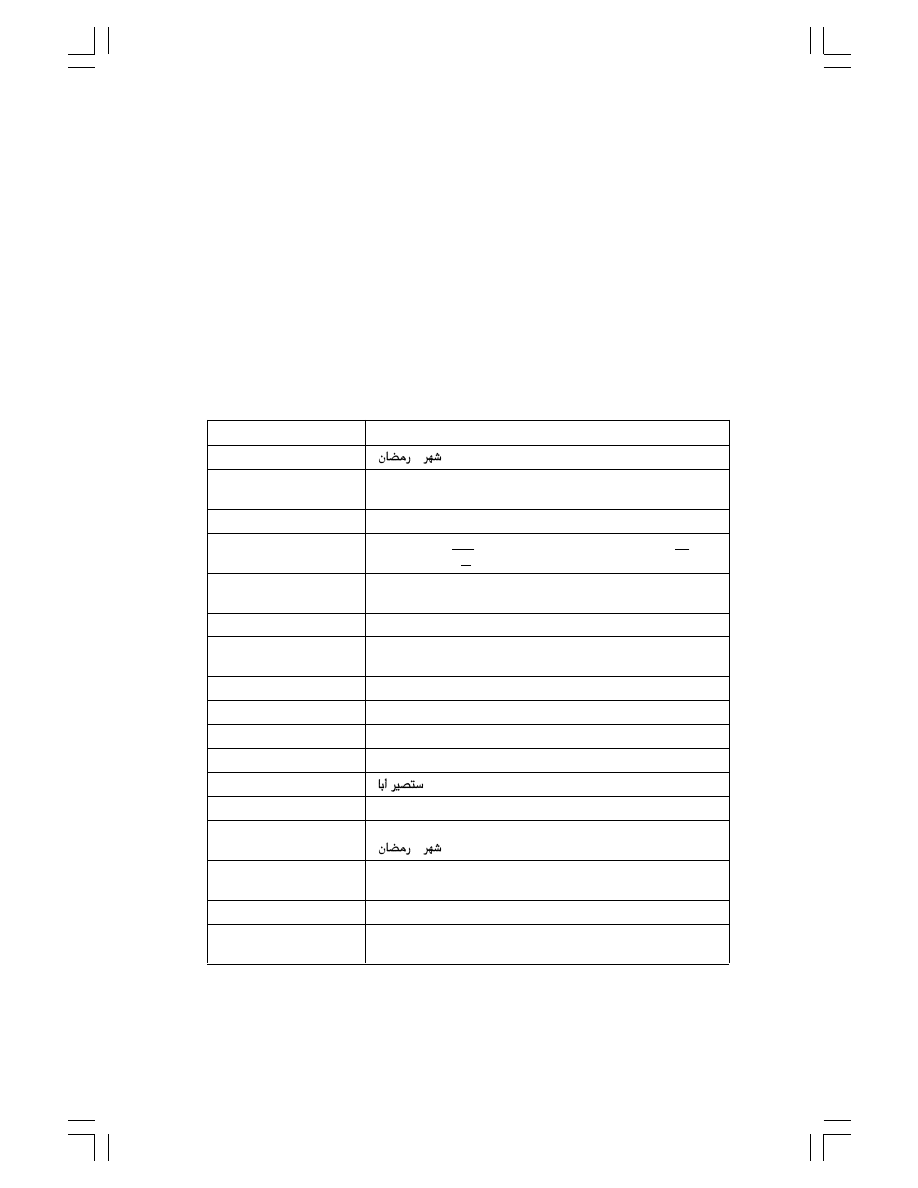

Table 6

Classification of translation techniques

Adaptation

Baseball (E)

⇒

Fútbol (Sp)

Amplification

(A)

⇒

Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting (E)

Borrowing

Pure: Lobby (E)

⇒

Lobby (Sp)

Naturalized: Meeting (E)

⇒

Mitin (Sp)

Calque

École normale (F)

⇒

Normal School (E)

Compensation

I was seeking thee, Flathead (E)

⇒

En vérité, c’est bien toi

que je cherche, O Tête-Plate (F)

Description

Panettone (I)

⇒

The traditional Italian cake eaten on

New Year’s Eve (E)

Discursive creation

Rumble fish (E)

⇒

La ley de la calle (Sp)

Established equivalent

They are as like as two peas (E)

⇒

Se parecen como dos gotas

de agua (Sp)

Generalization

Guichet, fenêtre, devanture (F) fi Window (E)

Linguistic amplification

No way (E)

⇒

De ninguna de las maneras (Sp)

Linguistic compression

Yes, so what? (E)

⇒

¿Y? (Sp)

Literal translation

She is reading (E)

⇒

Ella está leyendo (Sp)

Modulation

(A)

⇒

You are going to have a child (Sp)

Particularization

Window (E)

⇒

Guichet, fenêtre, devanture (F)

Reduction

Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting (Sp)

⇒

(A)

Substitution

Put your hand on your heart (A)

⇒

Thank you (E)

(linguistic, paralinguistic)

Transposition

He will soon be back (E)

⇒

No tardará en venir (Sp)

Variation

Introduction or change of dialectal indicators, changes of

tone, etc.

translation techniques revisited

511

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:16 PM

511

512

Meta, XLVII, 4, 2002

NOTES

1.

Cf. Molina (1998).

2.

This classification of translation techniques has been tested in Molina 1998, where it was used as an

instrument to analyse translations.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J.R. (1983): The architecture of cognition, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Delisle, J. (1993): La traduction raisonnée. Manuel d’initiation à la traduction professionnelle de

l’anglais vers le français, Ottawa: Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa.

Hurtado Albir, A. (1994): ‘Perspectivas de los Estudios sobre la traducción,’ in A. Hurtado Albir

(ed.) Estudis sobre la Traducció, Col. Estudis sobre la Traducció, vol. 1, Universitat Jaume I,

25-41.

—– (1996) ‘La traductología: lingüística y traductología,’ Trans 1, 151-160.

—– (1997) ‘La cuestión del método traductor. Método, estrategia y técnica de traducción,’

Sendebar, n

o

7, 12-20.

—– (1999) Enseñar a traducir, Madrid: Edelsa

Malblanc, A. 1968): Stylistique comparée du français et l’allemand, Paris: Didier.

Margot, J. Cl. (1979): Traduire sans trahir. La théorie de la traduction et son application aux textes

bibliques, Laussane: L’Age d’Homme.

Mason, I. (1994 ): ‘Techniques of translation revised: a text linguistic review of borring and

modulation ’ in A. Hurtado Albir (ed.) Estudis sobre la Traducció, Col. Estudis sobre la

Traducció, vol. 1, Universitat Jaume I, 61-72.

Molina, L. (1998): El tratamiento de los elementos culturales en las traducciones al árabe de “Cien

años de soledad”, Dissertation, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

—– (Research thesis in progress): Análisis descriptivo de los culturemas árabe- español. Universitat

Autònoma de Barcelona.

Newmark, P. (1988): A textbook of translation, London: Prentice Hall International.

Nida, E. A. (1964): Toward a Science of Translating with Special Reference to Principles and Proce-

dures Involved in Bible Translating, Leiden: E.J.Brill.

—– and Taber, Ch. (1969): The Theory and Practice of Translation, Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Pozo, J. I., Gonzalo, I. and Y. Postigo (1993): ‘Las estrategias de elaboración en el currículo:

estudios sobre el aprendizaje de procedimientos en diferentes dominios’ in C. Monereo

(ed.) Estrategias de aprendizaje, Barcelona: Domenech, 106- 112.

Scavée, P. and Intravaia, P. (1979): Traité de stylistique comparée. Analyse comparative de l’Italien

et du Français, Bruxelles: Didier.

Vázquez-Ayora, G. (1977): Introducción a la traductología, Washington: Georgetown University

Press.

Vinay, J.-P. and J. Darbelnet (1977): Stylistique comparée du français et de l’anglais, París: Didier:

Georgetown University Press.

01.Meta 47/4.Partie 1

11/21/02, 2:16 PM

512

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Content Based, Task based, and Participatory Approaches

Verb form and function

Is Technical Analysis Profitable, A Genetic Programming Approach

Complex Numbers and Functions

Plant Structure and Function F05

Operation And Function Light Anti Armor Weapons M72 And M136 (2)

The Heart Its Diseases and Functions

Map Sensor Purpose and Function

30 Szczupska Maciejczak Jarzebowski Development and Functio

Detection and Function of Opioid Receptors on Cells from the Immune System

SHSBC 208 TV?MO DYNAMIC AND ITEM ASSESSMENT

Content Based, Task based, and Participatory Approaches

Verb form and function

SSP 406 DCC Adaptive Chassis Control Design and Function

U5 6 Technical English Vocabulary and Grammar

5 Your Mother Tongue does Matter Translation in the Classroom and on the Web by Jarek Krajka2004 4

więcej podobnych podstron