KATOLICKI UNIWERSYTET LUBELSKI

JANA PAWŁA II

Wydział Nauk Humanistycznych

Instytut Filologii Angielskiej

Agata Bednarz

nr albumu: 81874

THE STRUCTURE OF DP IN ENGLISH AND POLISH

Praca magisterska

napisana pod kierunkiem

dr hab. Anny Bondaruk, prof. KUL

w Katedrze

Językoznawstwa Teoretycznego

Lublin 2010

2

CONTENTS

List of abbreviations ……..………………………………………………………… 4

Introduction ..………………………………………………………………………. 6

Chapter 1: The DP Hypothesis- Theoretical Background

Introduction…………………………………………………………………….. 9

1.1. The GB analysis of an NP and a clause ...……………………………... 9

1.2. Abney’s DP Hypothesis ...……………………………………………... 16

1.3. Further remarks on the structure of nominal phrases ..……….…….….. 24

Conclusion ..………………………………………………………………… 28

Chapter 2: Functional Projections within the DP

Introduction ……………………………………………………………………. 29

2.1. AgrP - Agreement Phrase ……………………………………………… 30

2.2. NumP – Number Phrase ……………………………………………….. 34

2.3. QP – Quantifier Phrase ……………………………………………….... 36

2.4. The order of adjectives …………………………………………………. 42

2.5. Little n – the nominal shell ………………………………………… …. 45

2.6. DemP – Demonstrative Phrase and PossP – Possessive Phrase ……….. 48

2.7. The hierarchy of functional elements within the DP …………………... 51

Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... 55

Chapter 3: The DP in Polish

Introduction ……………………………………………………………………. 57

3.1. Is there a DP in Polish? ………………………………………………... 58

3.1.1. Left Branch Extraction (LBE) …………………………………... 59

3.1.2. Double genitive constructions …………………………………... 65

3.1.3. The lack of N-to-D movement …………………………………. .. 66

3.1.4. Other arguments against the DP analysis of Polish nominals …... 68

3

3.2. The internal structure of nominal phrases in Polish …………………… 70

3.2.1. Noun – pronoun asymmetry. The position of personal pronouns .. 71

3.2.2. Adjectives ……………………………………………………...... 73

3.2.3. Possessive and demonstrative pronouns ………………………… 77

3.3. The structure of Polish nominal phrases ………………………….......... 79

Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... 81

Summary and conclusions ………………………………………………………... ... 83

References ………………………………………………………………………....... 88

4

List of Abbreviations

1

st

– first person

2

nd

– second person

3

rd

– third person

A – Adjective

ACC – accusative

Agr – Agreement

AgrP – Agreement Phrase

AP – Adjective Phrase

AUX – auxiliary

C – Complementizer

Class – Classification

ClassP – Classification Phras

Conj – Conjunction

ConjP – Conjunction Phrase

CP – Complementiser Phrase

D – Determiner

DAT – dative

def. – definite

Deg – Degree

DegP – Degree Phrase

Dem – Demonstrative

DemP – demonstrative Phrase

Det – Determiner

DP – Determiner Phrase

ERG – Ergative

EPP – Extended Projection Principle

fem. – feminine

Foc – Focus

FocP – Focus Phrase

GB Theory – the Government and

Binding Theory

GEN – genitive

I – Inflection

IP – Inflection Phrase

K – nominal complementizer

KP – nominal complementizer phrasal

projection

LBE – the Left Branch Extraction

masc. – masculine

n – light noun

N – Noun

NP – Noun Phrase

NOM – nominative

nP – light noun phrase

Num – Number

NumP – Number Phrase

Ø – empty position

Ɵ-role – theta- or thematic role

P – Preposition

pl. – plural

PP – Preposition Phrase

possd – Possessed feature

Q – Quantifier

QP – Quantifier Phrase

sing. – singular

5

Spec. – Specifier

Subj. – subjective

t – trace

Tns. – Tense

UTAH – the Uniormity of Theta Assignment Hypothesis

v – light verb

V – Verb

vP – light verb phrase

VP – Verb Phrase

X – any lexical category

XP – any phrasal category

6

Introduction

The aim of this dissertation is to investigate the structure of nominal expressions

in English and Polish. The thesis examines the syntax of nominal expressions in both

languages and aims at providing a universal representation of nominal phrases. The

starting point for the study is the DP Hypothesis put forward by Abney (1987).

The nominal expression investigated in this dissertation is a constituent headed

by a Noun. Some examples are given in (1) below:

(1) a. Mary is a student.

b. This is a big black dog.

c. The existence of DP in articleless languages is controversial.

All the expressions in italics given in (1) belong to a group of nominal phrases.

Although they differ in the degree of complexity, they all share the same syntactic

structure. Following Abney (1987), it is claimed that they are all instantiations of a

Determiner Phrase (DP). They are headed by a functional element D, whose overt

realisation corresponds to either a definite or an indefinite article (in English those are:

a(n)/ the).

Postulating the universality of grammar, it appears necessary to assume that the

same structure applies to all human languages, whether they show some overt

realisation of D or not.

However, a lot of controversies surround the structure of DP. Some of the

queries are listed below:

1. Are nominal expressions consisting of only one word DPs? (e.g. Mary)

7

2. If an article or an empty element constitutes a head of the phrase, what is the

syntactic position of other elements appearing within the phrase, i.e.

Quantifiers, Adjectives, etc.?

3. Why do articleless languages allow syntactic phenomena (e.g. Left Branch

Extraction) disallowed by languages with overt realisations of D?

Those questions and others have been addressed by numerous studies carried on

since the DP Hypothesis first appeared. Data taken from different languages and

different elements of nominal expressions were targeted. However, it is possible to

distinguish two major stands: one extending the DP Hypothesis onto all languages

without exceptions (Abney (1987), Progovac (1998), Migdalski (2000), Sio (2006),

Rutkowski (2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2007a, 2007b, 2009), among others), the other

treating the nominals appearing in aricleless languages as traditional NPs (Fukui (1986),

Chierchia (1998), Willim (2000), Kim (2004), Bošković (2003, 2004, 2005, 2008),

among others).

As far as the theoretical model is concerned, this study is based on two linguistic

theories created by Chomsky, i.e. the Government and Binding Theory (Chomsky

(1981)) and the Minimalist Program (Chomsky (2000, 2001)). The lack of a single

framework stems from the fact that a considerable number of important studies on the

structure of nominals has not been carried out with the recently recognised Minimalist

Program, for instance, two works crucial for this study: Abney’s (1987) The English

noun phrase in its sentential aspekt and Rutkowski’s (2007b) Hipoteza frazy

przedimkowej jako narzedzie opisu składniowego polskich grup imiennych.

This dissertation offers an overview of the DP Hypothesis, as well as more

recent interpretations of the structure of nominal expressions. Both approaches toward

8

articleless languages are taken into consideration. Chapter 1focusses on Abney’s (1987)

dissertation, which introduces the idea of DP structure. The goal of this chapter is to

present the DP Hypothesis, all together with its theoretical background. Furthermore,

early analyses of functional projections intervening between a DP and an NP are

outlined and explained.

Chapter 2 provides a survey of more recent approaches to the DP structure. The

major part of this chapter is devoted to various functional projections appearing

between a DP and an NP. This analysis leads to postulating a complete structure of

nominal phrases, which can be applied both to the English and Polish language.

The final chapter focuses on the analysis of the structure of Polish nominals. It

presents two recent approaches to nominal phrases in Slavic languages: one adapting

Abney’s DP Hypothesis to the Polish syntax, the other presenting Polish nominals as

NPs. Taking both approaches into consideration, the structure worked out in the

previous chapter of the study is explained and special attention is paid to the possibility

of adapting it to the Polish syntax. Finally, the complete structure of a DP in Polish is

presented.

9

Chapter 1

The DP Hypothesis - Theoretical Background

Introduction

The aim of Chapter 1 is to introduce the background and core assumptions of the DP

Hypothesis introduced by Stephen Abney in his PhD dissertation, in 1987. On the basis

of cross-linguistic indicators and facts, Abney demonstrates that the classical GB

interpretation of the structure of nominal phrases is flawed. He rejects the idea of a

nominal phrase understood as a phrasal projection of a lexical head – a Noun, and

suggests a new structure – one parallel to the structure of a clause and based on the

functional projection of a Determiner with an NP functioning as its complement.

The basic GB analysis of the structure of nominal phrases, together with syntactic

facts suggesting its explanatory inadequacy is given in section 1. Subsequently, section

2 outlines Abney’s DP Hypothesis, the way it is presented in his PhD dissertation.

Finally, section 3 focuses on further problems with the structure of nominal phrases,

especially concentrating on the position of elements intervening between a Determiner

and a Noun, i.e. Quantifiers, Adjectives, etc.

1.1 The GB analysis of an NP and a clause

The classical GB interpretation of the structure of nominal phrases provides us with

the following phrase maker:

10

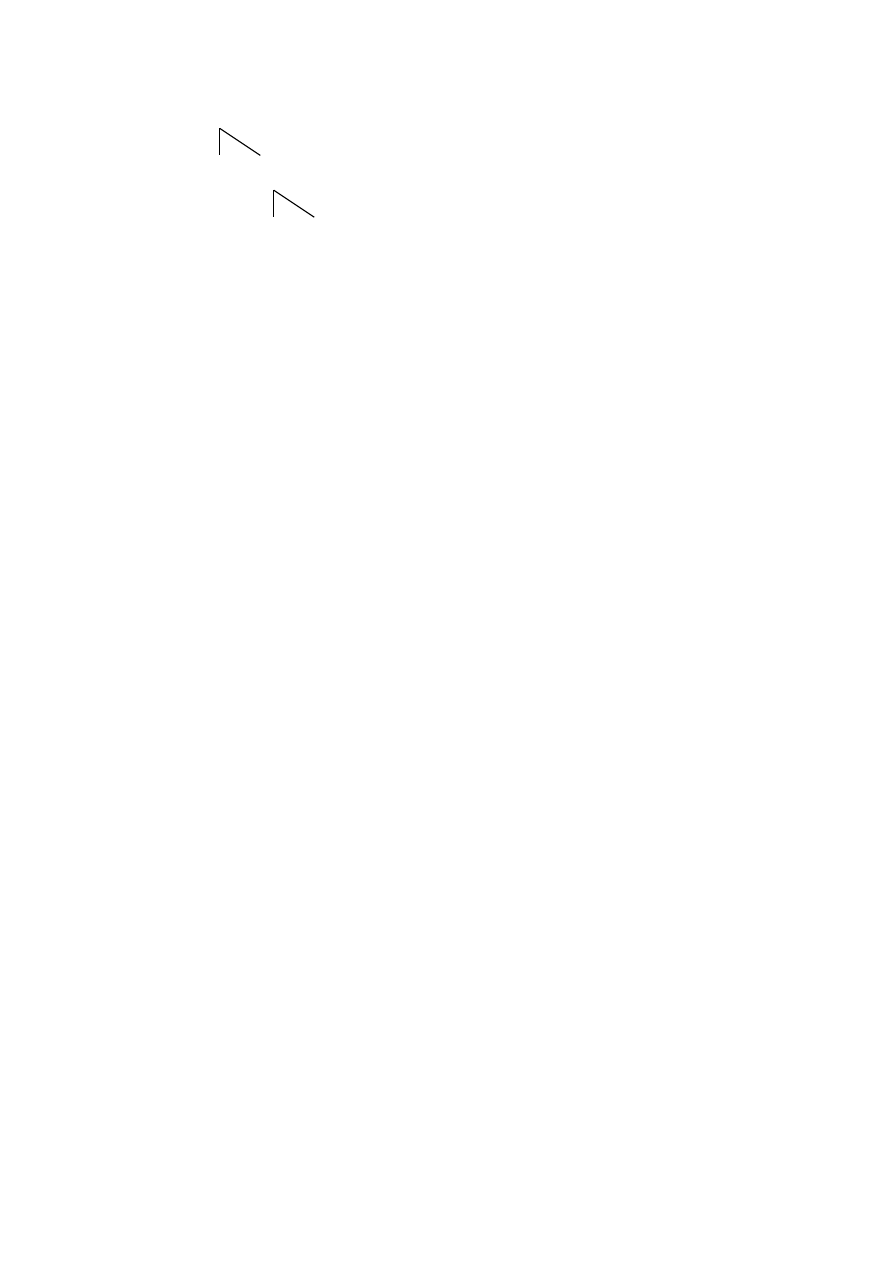

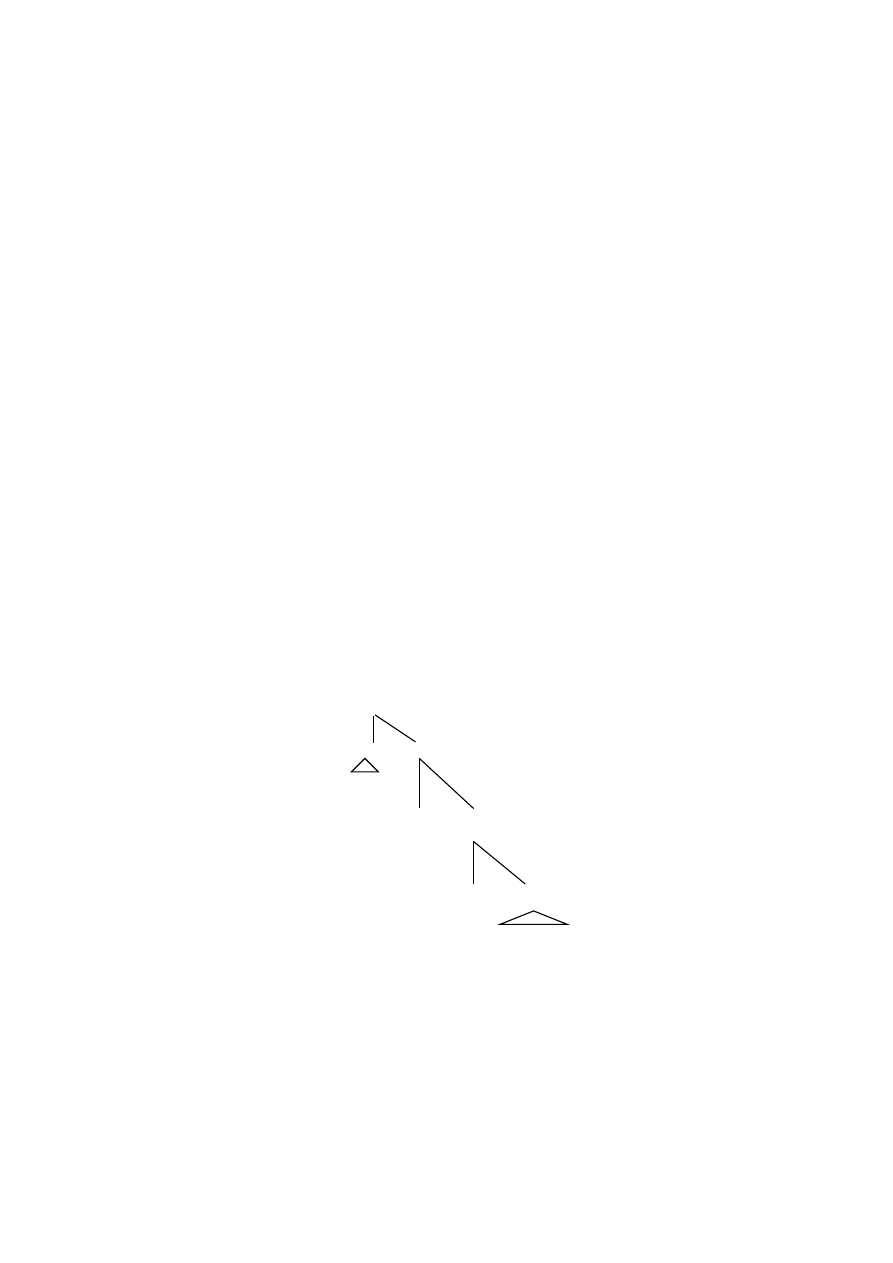

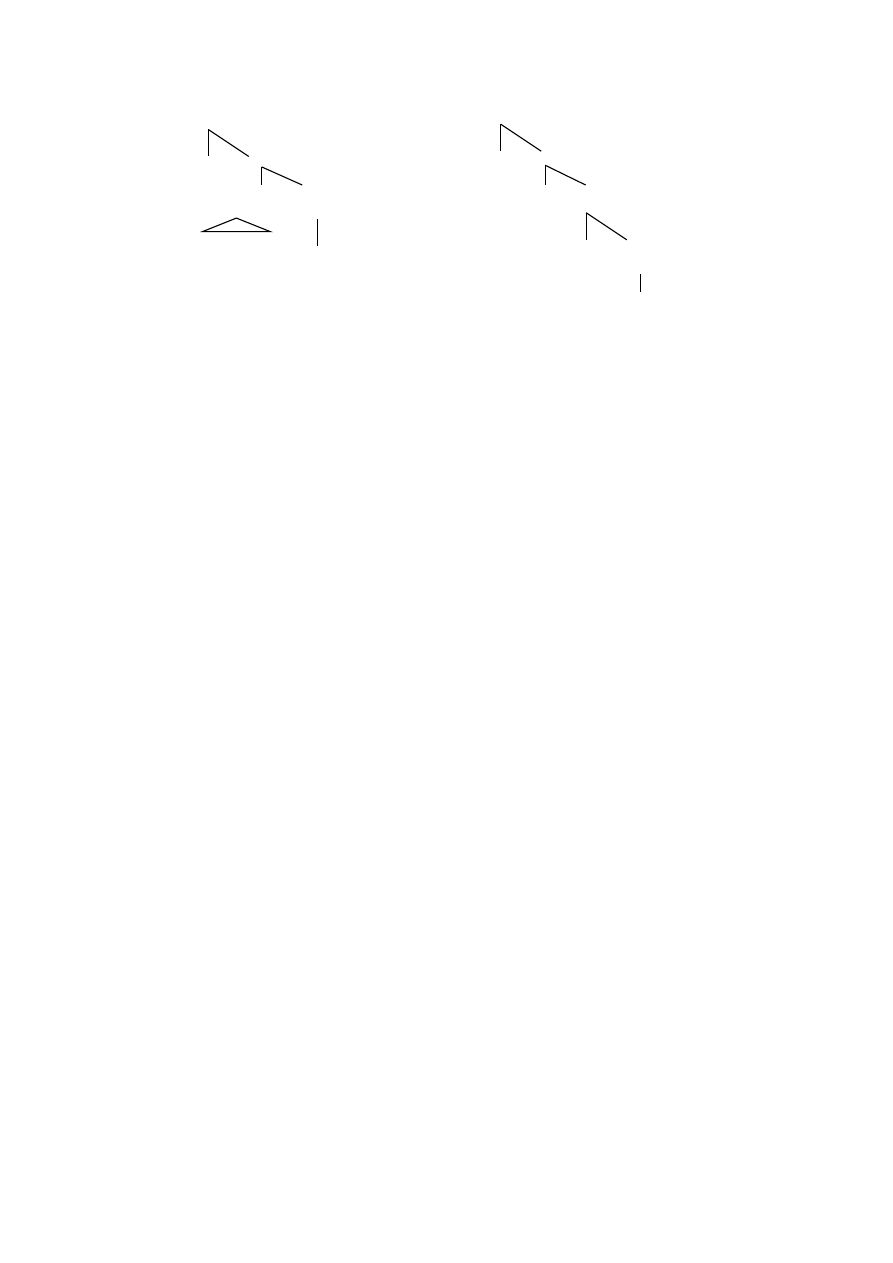

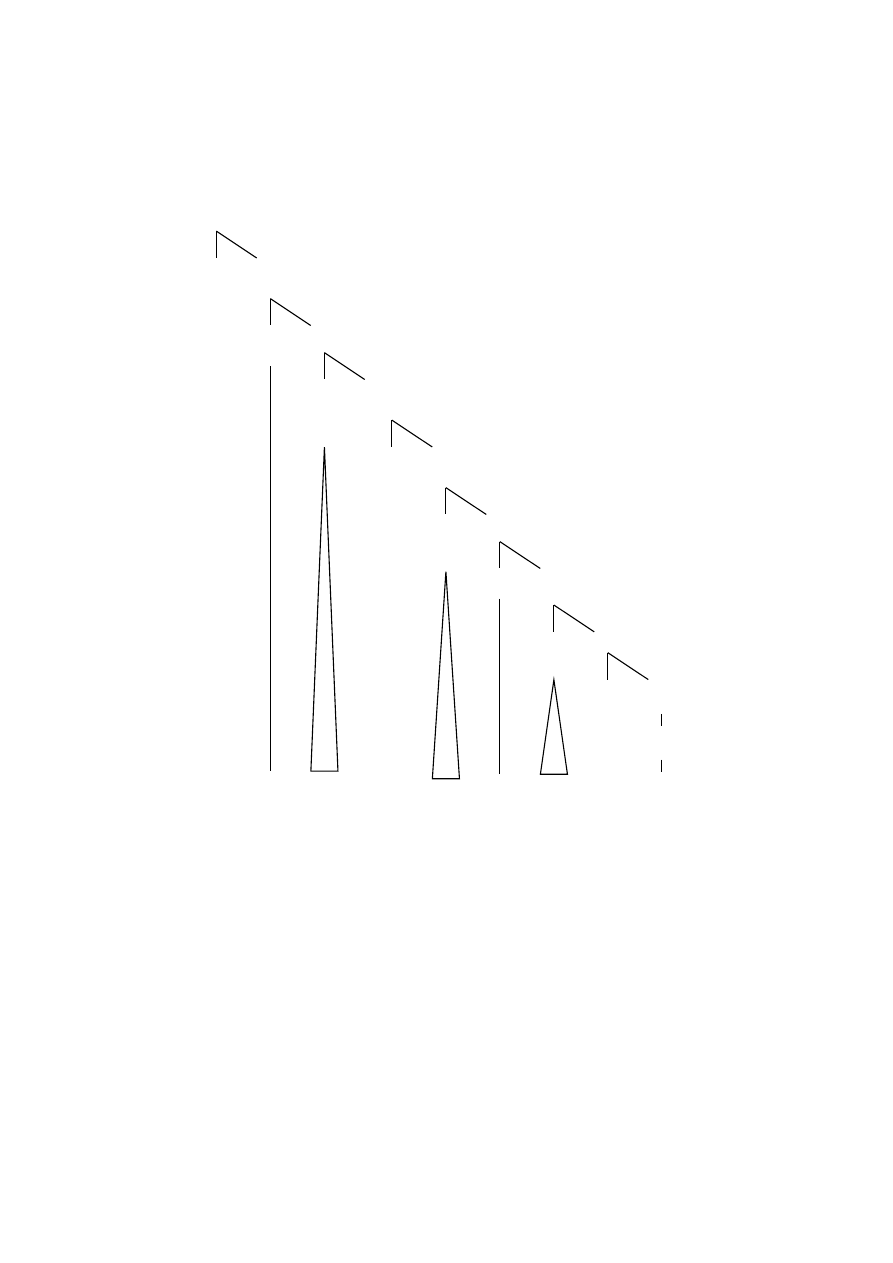

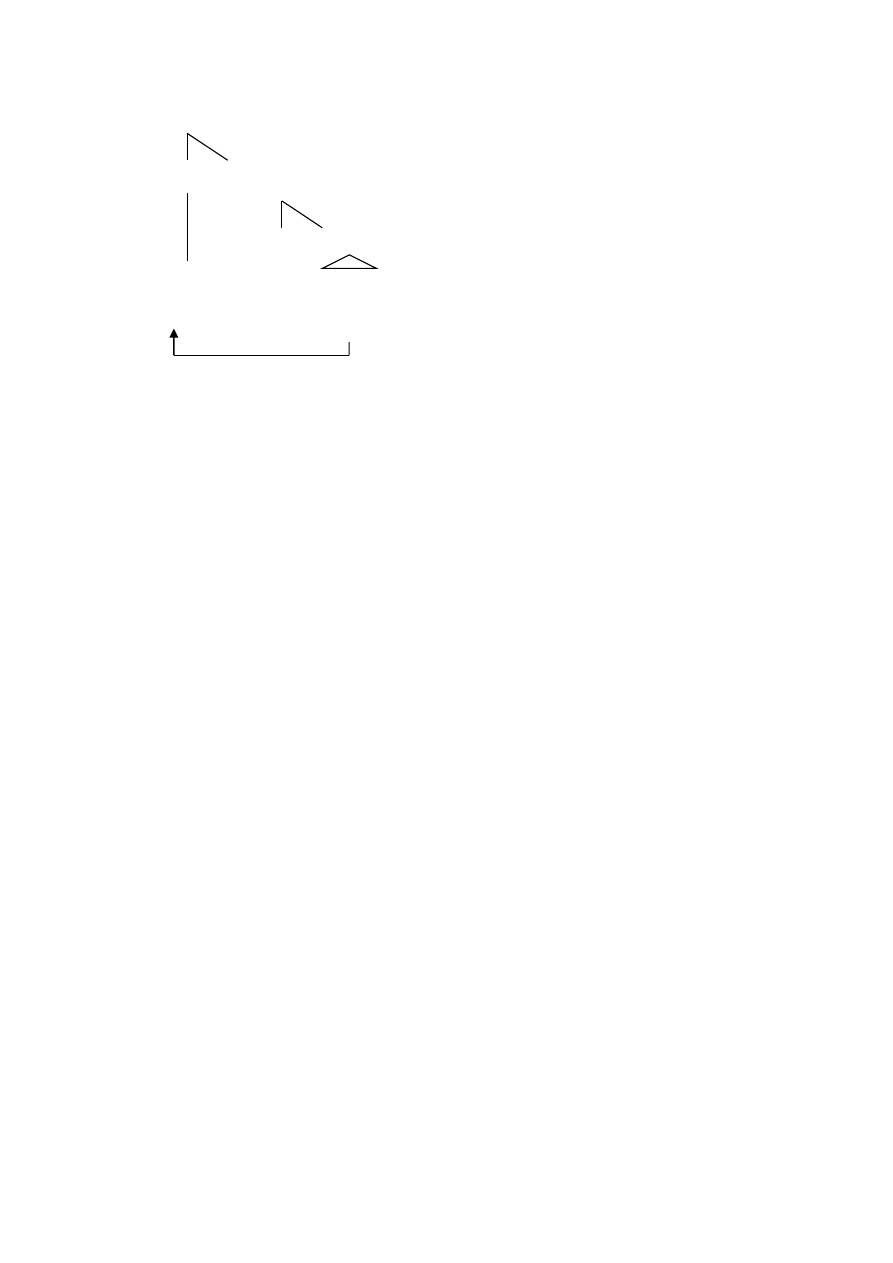

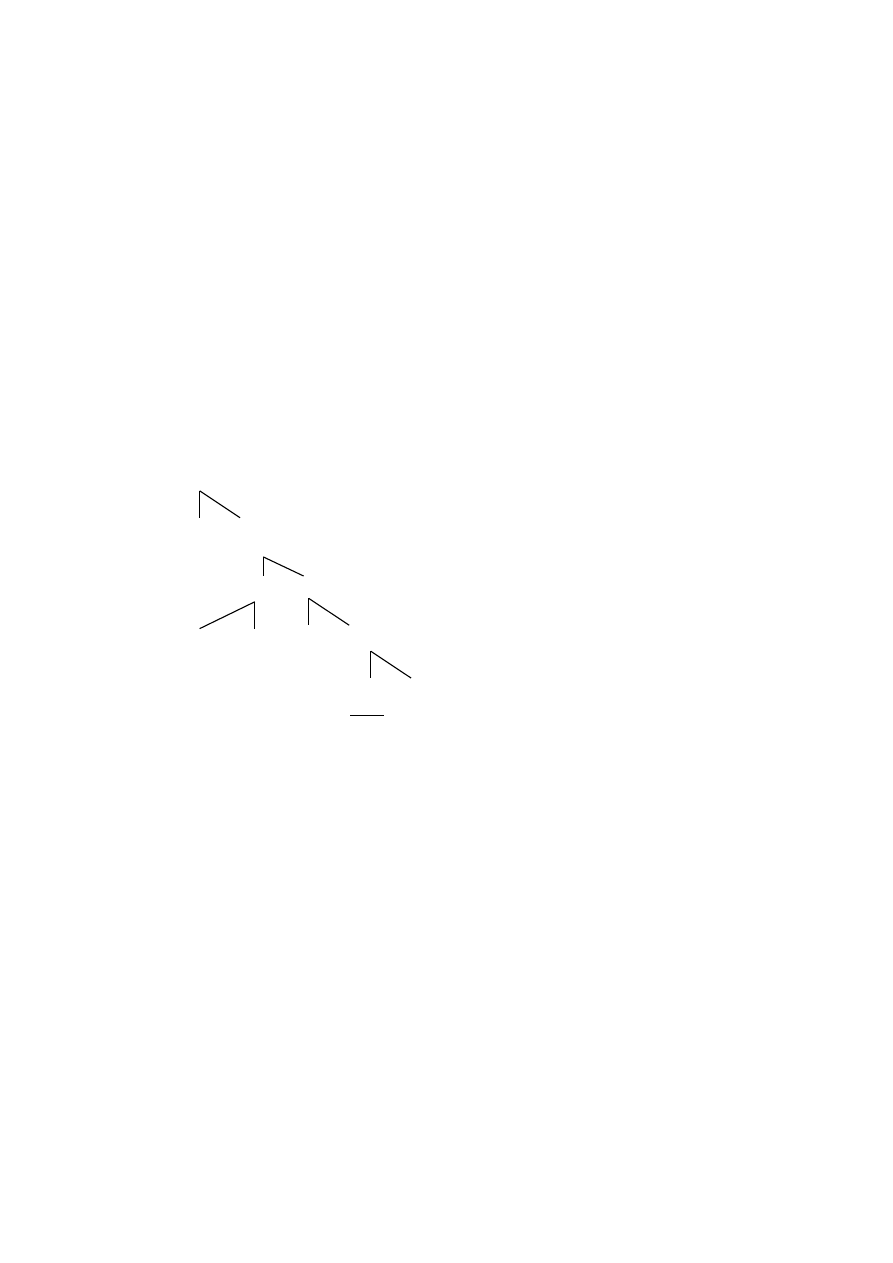

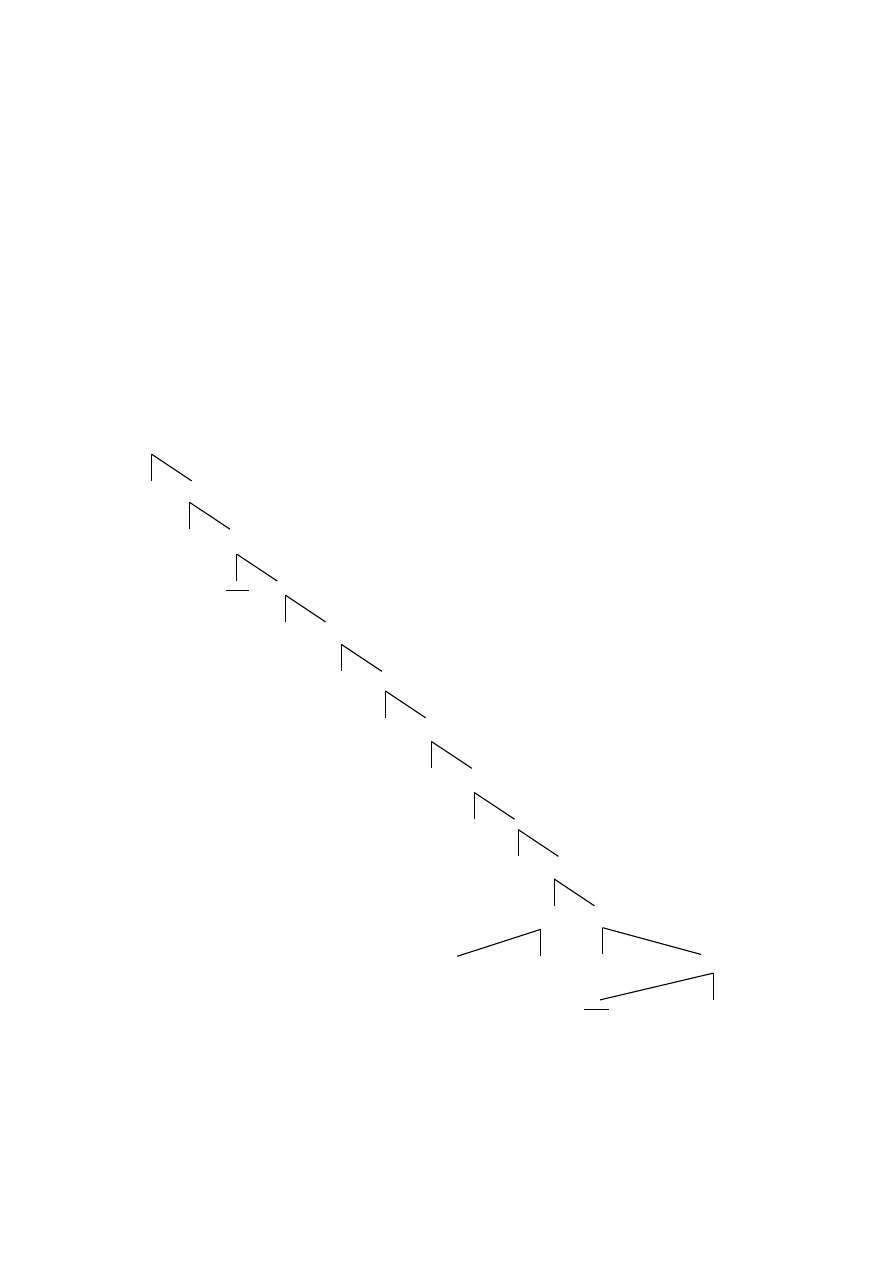

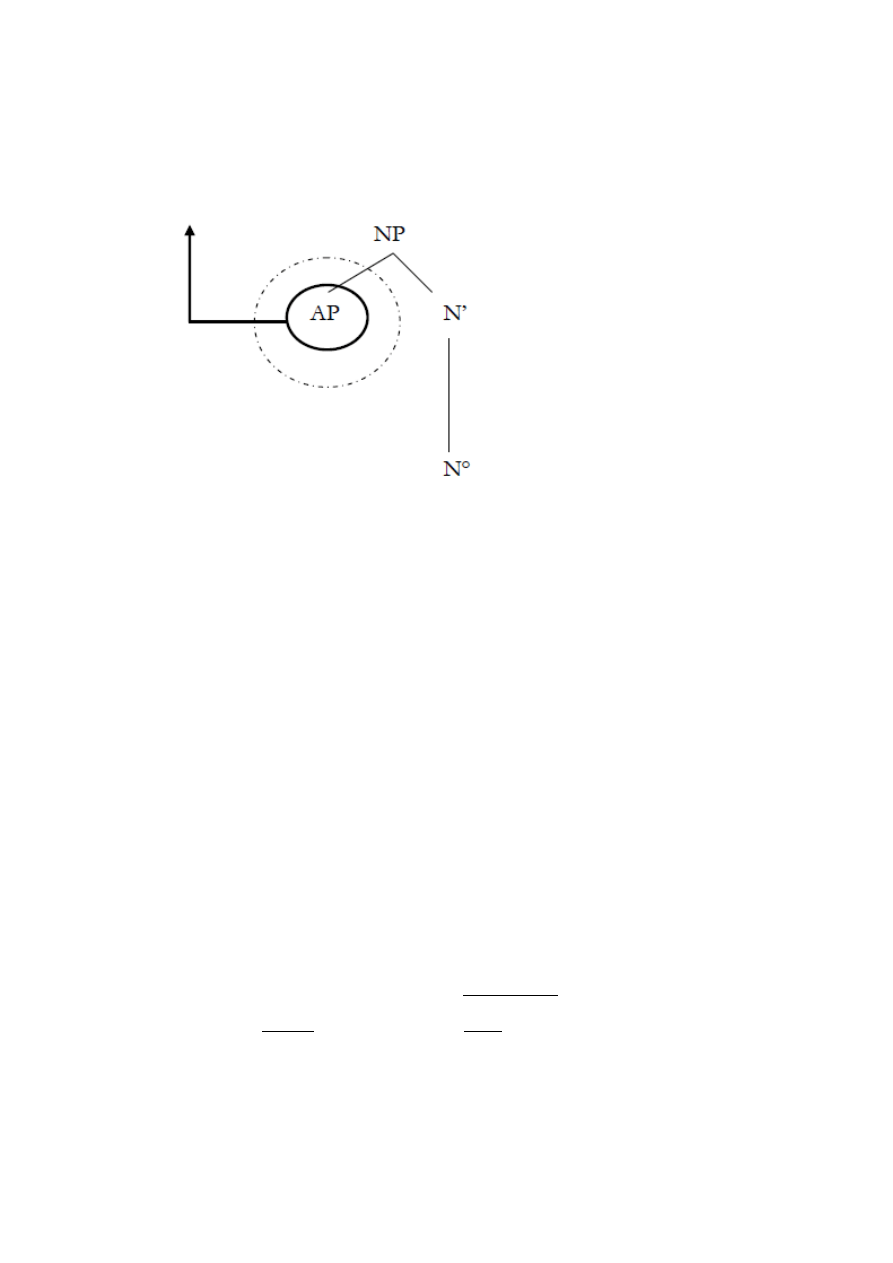

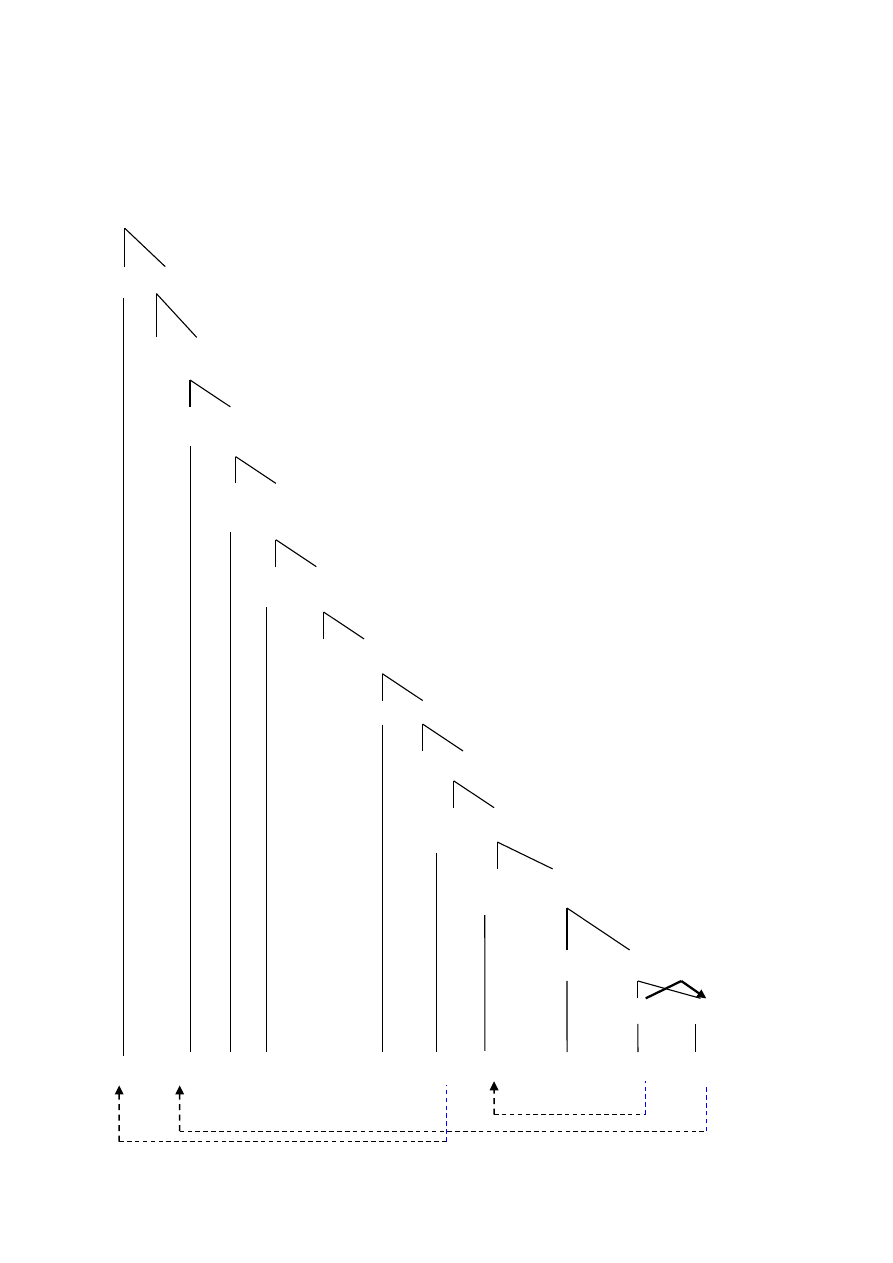

(1) NP

D(P) N’

N

XP

As can be seen in (1), the maximal projection of a nominal phrase, the NP,

dominates the intermediate projection N’ and the specifier D(P), the Determiner

(Phrase). The N’, in turn, dominates the zero projection, i.e. the Noun (N) and its

complement, marked as an XP in order to show that it can be realised syntactically by

various types of phrases, for instance PPs.

This structure is built in accordance with the X-bar Theory (Chomsky (1970);

Jackendoff (1977)). The phrase is endocentric – the constituents are projections of a

single head. It observes the Binary Branching Constraint – the higher nodes dominate

only two nodes at once – and the Singlemotherhood Constraint – nodes are dominated

only by one element at the same time.

However, that structure raises numerous questions. The basic one concernes the

status of Determiners. In English, all the elements that may appear under D, i.e.

possessives (possessive pronouns and genitives), demonstratives and articles, remain in

complementary distribution – they cannot co-occur within one phrase, as shown in (2).

(2) a. *the Mary’s description

b. *the her description

c. *Mary’s her description

d. *this the description

(Haegeman and Guéron (1999: 408))

e. this description

f. her description

g. Mary’s description

h. the description

11

The conclusion to be drawn from (2 a-h) is that all Determiners occupy the same

node – D. No clear evidence pointing to the possibility of claiming the existence of the

DP can be found – this fact is reflected by the presence of brackets, which are used to

mark optionality, within the DP in the phrase maker in (1). However, to accept the

possibility that Determiner Phrases do not exist is to accept a strong violation of the X-

bar Theory constraints, which also means accepting the fact that Determiners, as a class,

are possibly not able to project further, take complements or to have proper specifiers. If

this were so, Determiners would be the only exception within all lexical and functional

elements of a language.

What is more, the claim that all elements, traditionally bearing the name of

Determiners, share the same grammatical features turns out not to be true when

confronted with the data in (3a) and (3b) below:

(3) a. Mary’s house

b. the house

my teacher’s house

a house

the woman next door’s house

Ø houses

the French student’s house

this house

the teacher of history’s house

that house

her house

these houses

Thelma and Louise’s house

those houses

(Haegeman and Guéron (1999: 409))

As demonstrated in (3a), possessors are an open class of elements; they are

unlimited and new elements within this class can still appear. On the contrary, articles

and demonstratives, as can be seen in (3b), constitute a closed class – no new elements

can be created. This argument is true cross-linguistically – the restriction with regard to

the number of articles and demonstratives is evident in other languages as well, not only

in English. For instance, in Hungarian there is only one definite article a (Szabolcsi

(1984)). What is more, in comparison with the possessives, articles and demonstratives

12

do not contribute significantly to the descriptive content of the phrase. Articles carry the

[±definiteness] feature, whereas demonstratives indicate the spatial relation between the

speaker and the object being described (Haegeman and Guéron (1999: 410)).

It is also worth noticing that not all languages have a restriction on the co-

occurrencee of possessives and articles or demonstratives, as presented in (4).

(4) a. un mio libro

[Italian]

a my book

‘a book of mine’

b. esas ideas tuyas

[Spanish]

those ideas yours

‘those ideas of yours’

c. cartea ta

[Romance]

(Radford (1988: 171-172))

book-def. your

‘the book of yours’`

d. ten mój pies

[Polish]

this my dog

‘this dog of mine’

The constructions shown in (4) are ungrammatical in English but they are fully

grammatical in Romance and Slavic languages. A possible explanation for this

phenomenon is offered by Radford (1988). He suggests that Determiners can be

attached to the maximal projection of NP and they extend an NP into another NP. This

hypothetical structure is presented in (5) below:

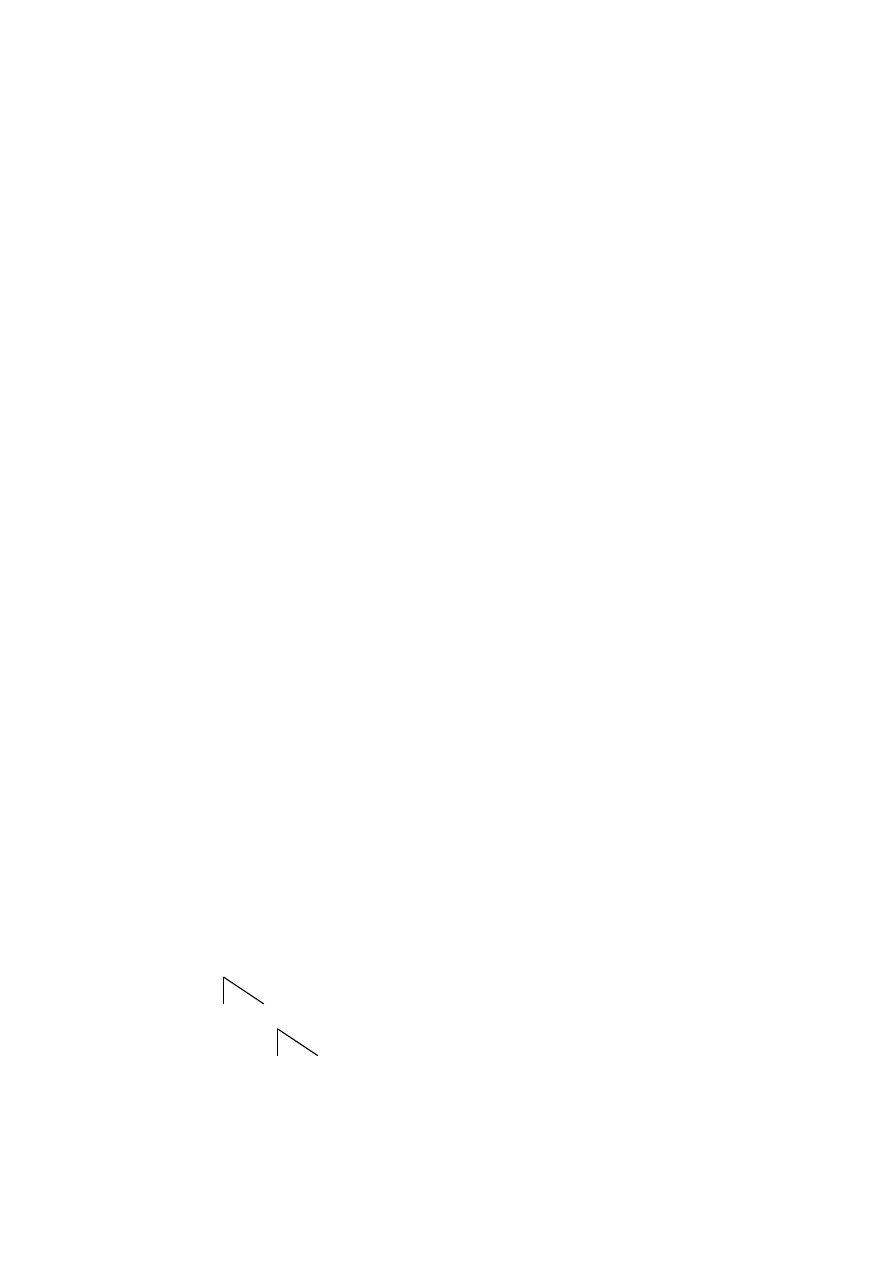

(5) a.

NP

b. NP→ D NP

D

NP

D

NP

13

On the basis of the structure in (5a), it is possible to formulate a phrase structure rule

presented in (5b), saying that an NP immediately dominates a Determiner and another

NP. This is strongly criticised by Radford (1988). A major flaw of this line of reasoning

is that it does not take into consideration the fact that rule (5b) is recursive and hence

can be reapplied indefinitely many times. In accordance with rule (5b), the structures

presented in (6) below would be recognised as grammatical.

(6) a. *the a this my car

b. *mój ten wasz tamten stół

[Polish]

*my this your that table

c. *un mio tuo quello libro

[Italian]

*a my your this book

As can be seen in (6a-c ), a larger number of Determiners within one nominal

phrase is ungrammatical even in Romance or Slavic languages, in spite of the fact that

these languages normally allow the combination of a possessor plus an article or a

demonstrative.

Analysing the notion of multiple determiners presented above, a conclusion may

be drawn that possessors constitute a class of elements different from articles and

demonstratives and, because of this, they need to have a separate position assigned to

them within the construction of a nominal phrase (Haegeman and Guéron (1999)). This

position seems to be missing in the classical structure that treats nominal phrases simply

as NPs with Determiners occupying the position of [Spec; NP].

Further evidence against the structure in (1) stems from a comparison of Nouns

and Verbs understood as two most important lexical classes. In contradistinction to the

questionable structure of a nominal phrase, the GB Theory provides us with a complete

14

and in-depth analysis of verbal phrases. Verbs (and Nouns alike) project maximal

projections – Verb Phrases (VPs) but, above all, they are augmented with functional

projections of an Inflection and a Complementiser. Therefore, the entire clause is

understood as an extended projection of a Verb. This structure is presented in (7).

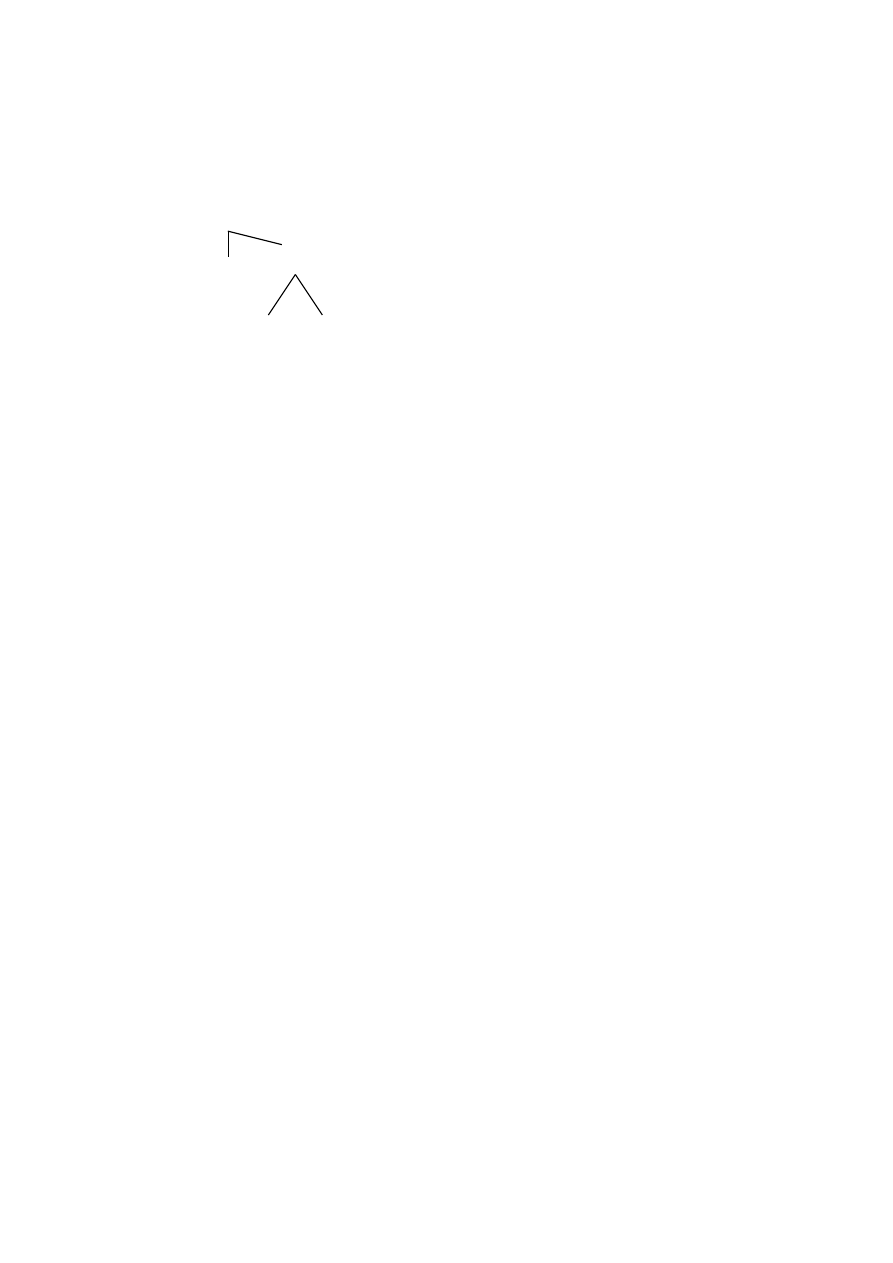

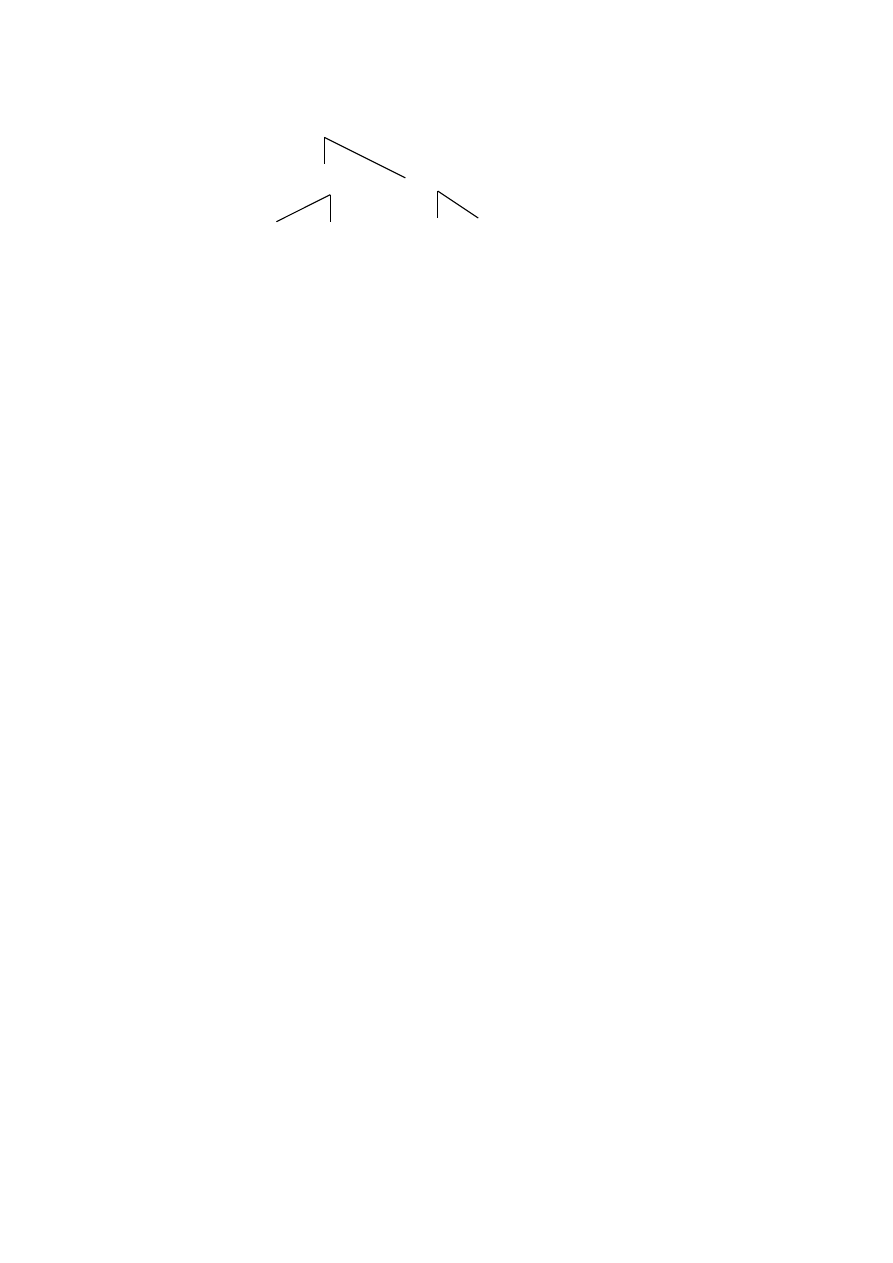

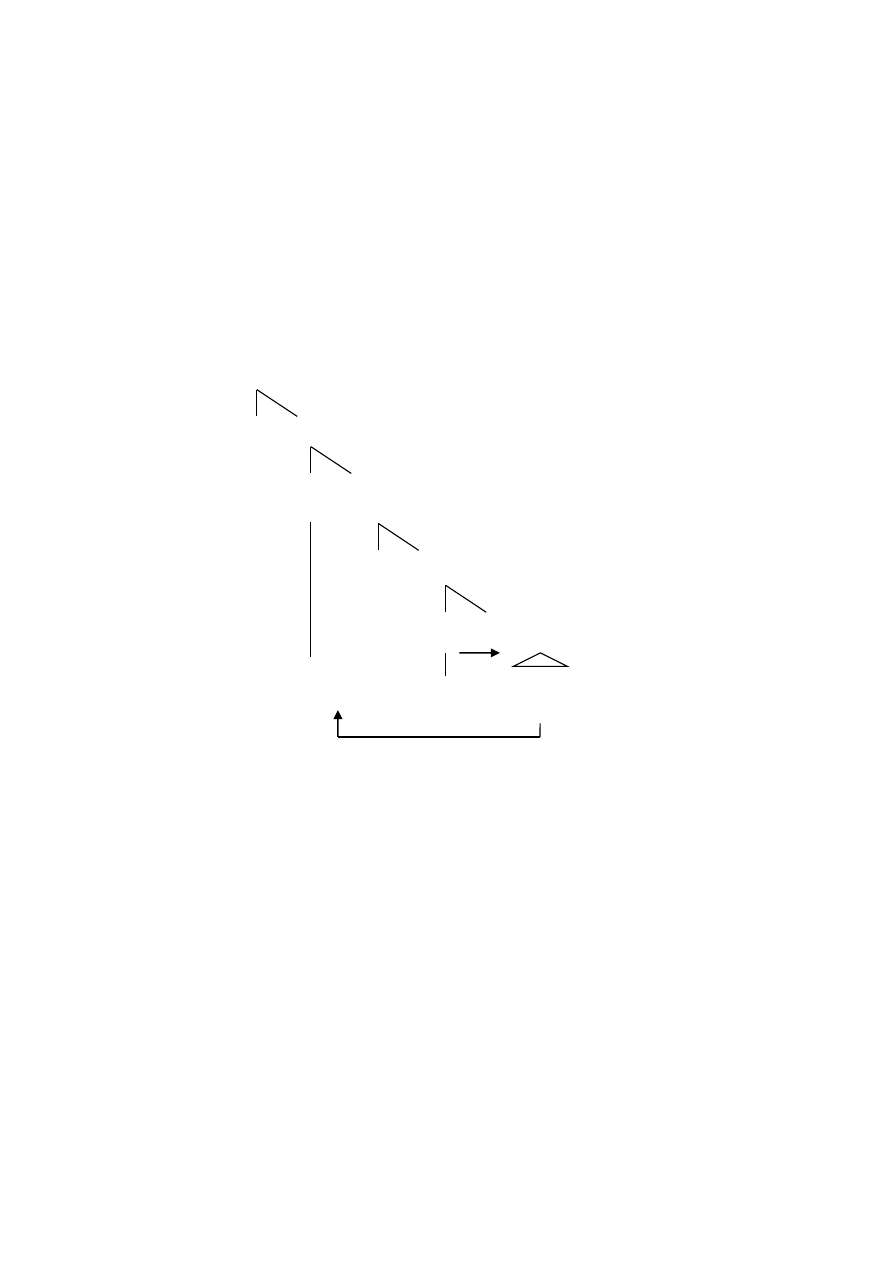

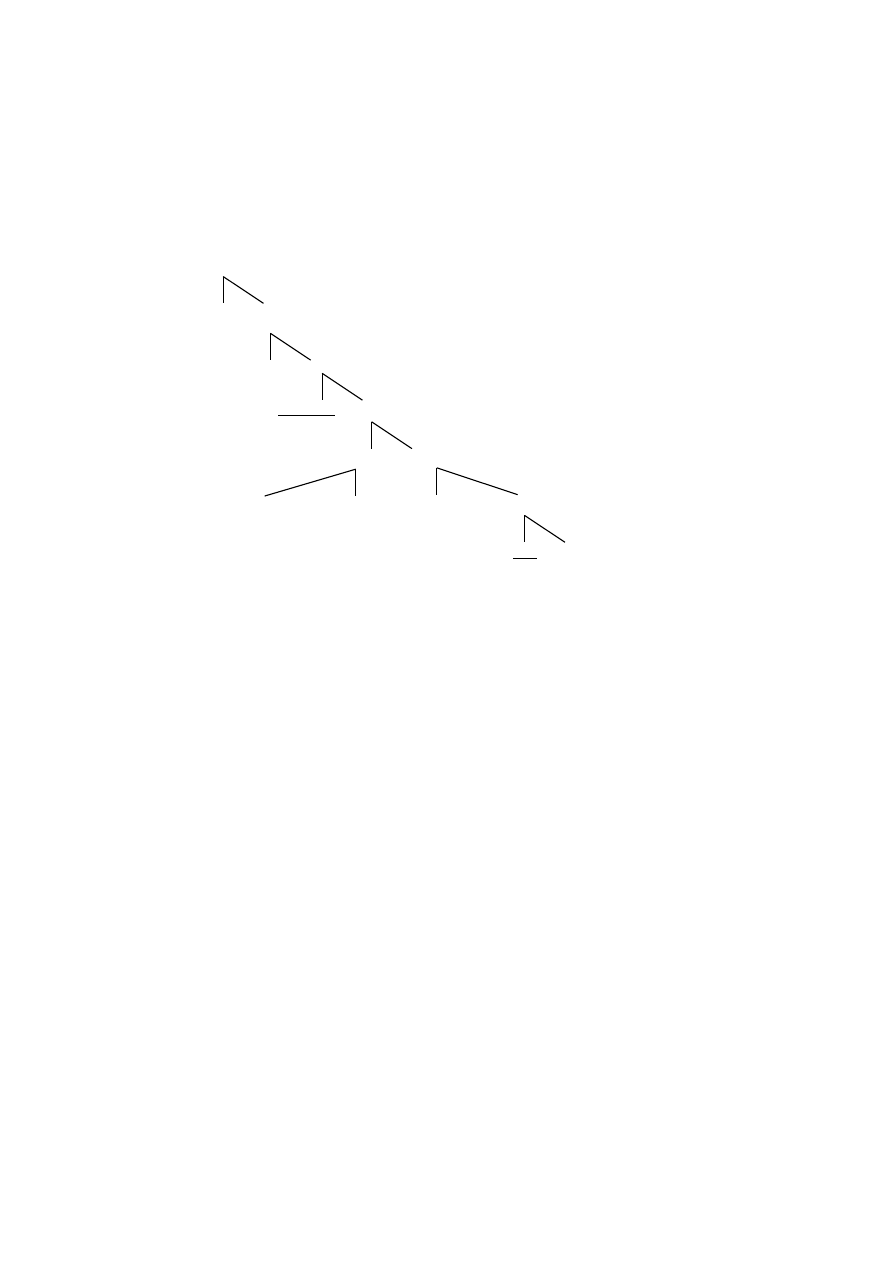

(7) CP

Spec

C’

C

IP

NP

I’

I

VP

[± tense]

[±agreement] Specifier V’

(Haegeman (1997:18))

V

XP

As can be seen, each lexical or functional element within a clause projects its

intermediate and maximal projection in accordance with the X-bar Theory. The highest

projection of the clause is the CP – the Complementiser Phrase, that dominates its

specifier and C’. The CP is headed by a Complementiser, which carries the illocutionary

force of the sentence and takes the IP – the Inflection Phrase as its complement. The IP

immediately dominates the NP (which fulfils the role of the subject of the clause) and

I’. The I’ dominates the head of the IP. I is the functional element carrying the features

[± tense; ±agreement]. The complement of I is the Verb Phrase –VP, which

immediately dominates its specifier and V.’ VP is headed by a Verb which can take

numerous possible types of complements (for instance: PPs, NPs, CPs, etc.).

The complexity of the structure presented in (8) is even more striking when we

consider the following facts revealing the similarities between nominal and verbal

15

phrases that cannot be explained with the help of the structure in (1). First of all,

Determiners show some features similar to Complementisers (Haegeman and Guéron

(1999)). They constitute a closed class of functional elements and they do not contribute

significantly to the semantics of the sentence. Still, they can introduce the Noun Phrase

and have the [±definiteness] or [±distance] feature.

In addition, there appears another question, this time, based on the analysis of the

semantic projection of a Verb Phrase and a Noun Phrase. According to Chomsky

(1957), each lexical item has its categorial (c-) and semantic (s-) projection. The two c-

projections are an X-bar and an X-double-bar projections of the syntactic unit and the s-

projection is a projection of the meaning of the lexical item. It is worth focusing on the

fact that the s-projection of a verb spreads over the best part of the sentence involving

all of its main elements, i.e. the subject, the predicate and the objects. To put it another

way, the whole clause refers to the action denoted by the verb, other parts of the

sentence, e.g. adverbials, just give some additional information. By way of illustration,

in John is doing homework, the whole clause expresses an action of doing homework.

Here homework constitutes a complement of the verb, whereas John (Specifier of IP)

adds the information about who the Agent is.

In contradistinction to a Verb, a Noun has a narrower-spread s-projection – it is

simply the same as the c-projection of the noun (i.e. NP). Therefore, it affects only

complements enclosed within the NP.

16

1.2 Abney’s DP Hypothesis

The starting point for Abney’s dissertation is an ambiguous construction that could

be understood both as an NP and a clause (Abney (1987: 14-15)). An example of this

construction is shown in (8) below:

(8)

John’s building a spaceship.

That can be paraphrased as follows:

(9) John built a spaceship.

With the meaning illustrated in (9) the structure constitutes the so-called

‘Poss- ing’ gerundive construction, which in its form is similar to a clause, yet it

remains an NP. From the comparison of (8) and the corresponding clause (9) one

may draw the following conclusions, which may later on serve as evidence for the

theory assuming the existence of DPs:

1. The structure of (8) is similar to the structure of (9): John is a subject, building

denotes the action, therefore fulfils the same function as a verb, and a spaceship

is an object.

2. (8), in contrast to (9), is an NP because it has the characteristic distribution of

NPs, i.e. it can function as a [Spec; IP], compare the following examples (Abney

(1987: 15)):

(10) a. *Did [that John built a spaceship] upset you?

b. Did [John’s building a spaceship] upset you?

c. Did [John] upset you?

Putting these two pieces of information together, we obtain a structure as presented

in the P-maker below:

17

(11)

NP

.

NP

VP

John’s

V

NP

building a spaceship

Here the NP John's building a spaceship comprises an NP John’s in the position of

[Spec; NP] and its verbal complement building a spaceship. However, this structure

represents a strong violation of basic conditions on syntactic structure of phrases. First

of all, the Endocentricity Constraint is violated by the fact that the highest NP lacks a

head. Secondly, the structure of NPs John’s and a spaceship is still unclear.

Abney’s solution to this problem is as follows: the structure of noun phrases must be

based on the structure of clauses and it must be headed by an inflectional element. As a

result of this, the Endocentricity Constraint is satisfied and the presence of an overt

gerundive ending ’s is accounted for. The P-maker of an NP structure showing the

similarity to a clause is given in (12b) (Abney (1987:23)).

(12) a. Clause

b. Abney’s nominal phrase

IP

XP

NP

I’

XP

X’

John

John’s

I

VP

X

VP

[Tns, Agr]

[Agr]

V

NP

V

NP

built a spaceship

building a spaceship

18

The head of the nominal phrase is a functional element represented by Agreement

(it has no name by itself because its functions are still not clarified, therefore it remains

marked as an X). The VP building a spaceship is its complement, and John's (another

nominal expression) functions as its Specifier. This structure can be confirmed by

examples from Turkish, especially as far as the inflectional projection hosting Agr is

concerned:

(13) a. el

b. sen-in el-in

c. on-un el-i

you- Gen hand- 2

nd

sg

he-Gen hand-3

rd

sg

‘the/a hand’

‘your hand’

‘his hand’

(Abney (1987:21))

In the examples above a noun acquires the same number and person as the

possessive pronoun preceding it. This strong agreement between the possessor and the

noun in Turkish serves as an argument for the presence of an Agr within the noun

phrase. The logical consequence of this postulate and the fact that within clauses the

Agr feature, always carried by the functional element (I), is required by a functional

element present within an NP and similar to the I.

The idea of the inflectional projection within the noun phrase seems even more

unavoidable in the case of languages like Yup’ik, in which the subject of a noun phrase

is assigned the same Ergative case as the subject of a clause.

(14) a. angute-t kiputa- a- t

the men- Erg buy- Past- it- 3

rd

pl masc

‘the men bought it’

b. angute- t kuiga- t

the men- Erg river- 3

rd

pl masc

‘the men’s river’

(Abney (1987: 39))

19

According to Abney (1987), the mysterious element similar to I and carrying the

Agr feature is in fact a Determiner (D) projecting into a D’ and further on into a DP. His

arguments supporting this hypothesis are as follows (Abney (1987: 75-76)):

1. Determiners are a class of functional elements, therefore they can behave

like modals (which appear under I in IPs) and appear under functional D.

What is more, they are the best candidate for being a carrier of the Agr

feature, similarly to the Inflection within a clause.

2. With the hypothesis applied, it is finally possible to distinguish the

intermediate and maximal projections and pinpoint specifiers and

complements taken by Determiners. As a result, Determiners, as a class, are

no longer defective with respect to the X’- theory.

The representation of this new structure of nominal phrases is shown in the P-

maker below:

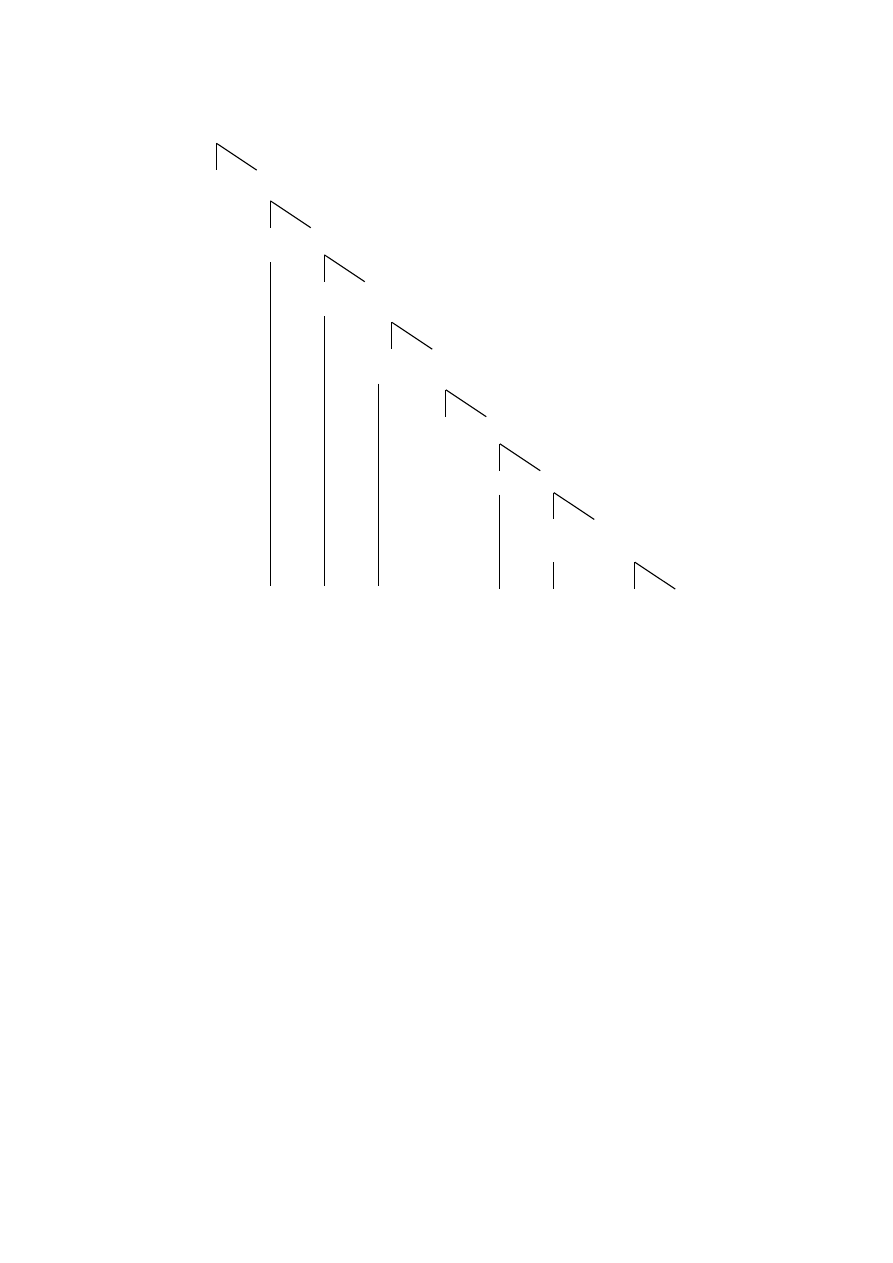

(15)

DP

.

DP

D’

John’s

D

VP

Agr

V

NP

building a spaceship

The nominal phrase is presented as a DP headed by a functional D filled by the

Agr. The main DP takes its own specifier and the complement, i.e. the DP John's and

the VP building a spaceship, respectively, this structure works for any kind of nominal

20

expression in English. The space for all pre-nominal elements is provided, and the

presence of Agreement is accounted for and shown within the structure below:

(16)

DP

D’

DP

D

NP

a.

my

Agr

pen

b.

Ø

a

cat

It also accounts for double-modifier structures combining an article with a

possessor (i.e. multiple modifiers presented already on the basis of examples taken from

Romance and Slavic languages in section 1.2. of this chapter), which appear also in

Hungarian. There, the possessor, a determiner, is preceded by another determiner - the

definite article a/az, e.g.

(17) a. Az en vendeg-e-m

the my guest- possd-1

st

sg

‘my quest’

b. a te ismerös- ei- d

the your acquaintance-possd-2

nd

sg

‘your acquaintance’

(Abney (1987: 44))

Here the overt agreement between the possessor and the noun as well as the

appearance of multiple determiners (which were placed by Jackendoff (1977)) within a

treble- bar structure, violating basic constraints of the X-bar Theory) suggests that the

DP hypothesis is in fact true. Not only is there a need for a functional element that

would carry the agreement feature but also there must be a position for the possessive

pronoun that in classical interpretations filled the position of [Spec; NP], i.e.

Determiner. Following Szabolsci (1984), Abney claims that an additional determiner

21

like this appearing in Hungarian is a kind of complementiser K introducing noun

phrases instead of clauses

and projecting into K-bar and K-double-bar (Abney (1987:

44) after Szablocsi (1984)). This fact stresses still more strongly the sentential aspect of

nominal phrases. An example of a Hungarian phrase with a double-modifier and its P-

maker is shown in (18) (cf. (17a)).

(18) KP

K

DP

az

DP

i

D’

en

D

NP.

Agr

i

-m

N

N

j

Agr

j

vendeg- e-

(Abney (1987:44, 251))

What is also worth mentioning, Abney’s DP hypothesis allows us to locate PRO

in a subject position within the noun phrase. This ‘nominal’ PRO functions as an Agent

in cases like (19) below (Abney (1987:92)) e.g.

(19) [

DP

PRO the [

DP

destruction of the city]]

22

Here PRO is assigned a Θ-role via predication – PRO functions as an external argument

of destruction (reflecting the argument structure of clauses). What is more, PRO is also

responsible for licensing rationale clauses embedded within a noun phrase.

(20) the PRO review of the book [PRO to prove a point] (Abney (1987:93))

As can be seen in (20), only when PRO is present is the rationale clause

licensed, because the process of licensing requires the Agent Θ-role realized

syntactically and covert PRO can assume this role.

Another piece of evidence for Abney’s hypothesis is the notion of head to head

movement within the noun phrase, which accounts for post-nominal adjectives in

English. What is more, the NP-internal head-to-head movement reflects another

similarity between CPs and DPs. The head of the NP is claimed to move to the head of

the DP position (the equivalent of V-to- T and T- to- C movements). Due to this fact

adjectives appearing postnominally in English

are not exceptions any more but fit into a

general paradigm

(Abney (

1987: 287)).

(21)

a. a good boy

c. *good someone

b. *a boy good

d. someone good

According to Abney, someone like everyone, anyone, etc., represent

morphological mergers. Every and one are separately merged within an NP and they can

be formed thanks to the movement of one to the D position, which is illustrated in (22)

below:

23

(22)

DP

.

D

NP

D

N

AP

N’

some-one

i

good

N

t

i

In fact, not only have the concepts of PRO and head movement been affected by

the DP hypothesis, but above all, the notion of the determiner has undergone a great

change. Before 1987, the category of determiners included both possessors and articles.

However, after Abney’s dissertation, the status of possessors and pronouns has radically

changed. Abney claims that possessors cannot be determiners because:

1. possessors co-occur with other determiners therefore, they cannot occupy the

same place within the structure of the phrase (Abney (1987: 270)), e.g.

(23) a. in Italian:

un mio libro

‘a my book’

b. in Hungarian: az en ostalem

‘the my table’

2. possessors do not have the same distribution as DPs, as shown in (24):

(24) a. * the car of [Mark’s]

b. the car of [Mark]

c. [Mark’s] car (Abney (1987: 270))

On the contrary, pronouns are typical determiners:

1. pronouns do not occur with modifiers typical for NPs

(25) a. *Mark’s [you]

b. Mark’s [car] (Abney (1987: 281))

24

2. pronouns can appear with nouns within the so called idiosyncratic gaps, e.g.

(26) a. I Claudius

b. You fool

(Abney (1987: 282))

1.3 Further remarks on the structure of nominal phrases

Placing Determiners in the position of the head of a nominal phrase solves the main

problems that were left untouched by the traditional analysis of nominals. However,

there still remain queries left without answers, e.g. the question of the position of

elements intervening between Determiners and Nouns (written in italics) in (27) below.

(27) a. the many good man

(Abney (1987:290))

b. Ø two parts steel

c. Ø two dozen roses

d. Ø three men

(Abney (1987: 291))

The phrases presented above are the instances of a quantifier phrase - (27a), a

measure phrase - (27b), a semi-numeral phrase - (27c) and a numeral phrase - (27d).

They are all understood by Jackendoff (1977) as instances of treble-bar NPs, which are

unacceptable in the X-bar Theory. Abney’s (1987) answer to this problem is

proclaiming the existence of an additional projection appearing between a DP and an

NP, i.e. an AP (Adjective Phrase). Both structures - Jackendoff’s (28a) and Abney’s

(28b) - are shown below:

25

(28) a. N’’’

(Jackendoff (1977: 291))

b. DP

(Abney (1987:336))

Possr/D N’’

D AP

QP/NP

N’

DegP A’

two parts

two

N

A

NP

steel

parts

N

steel

In comparison with Jackendoff’s proposal in (28a), the structure offered by Abney in

(28b) shows the compliance with the X-bar Theory - no treble-bar projections are

involved. What is more, it provides us with a full structure with a place for an Adjective

Phrase.

Abney assumes that Quantifiers, Adverbs and descriptive Adjectives belong to a

single category of Adjectives (Abney (1987:293)) and that pre-nominal and post-

nominal Adjective Phrases differ in their inner structure and nature (Abney (1987:326)).

The first assumption stems from the following facts:

1. Quantifiers and Adjectives differ mostly in their semantics; the differences in

supporting the partitive constructions and functioning as pronouns do not

concern the comparative and superlative (Abney (1987:301)).

2. Adverbs and Adjectives take the same degree words and Adverbs as their

modifiers as shown in (29) (Abney (1987:301)). The ending -ly present with

Adverbs is just a prepositional adjective Case-marker and may be treated like

verbal ending -ing (Abney (1987:302) after Larson (1987)).

(29) a. sufficiently quick

b. sufficiently quickly

(Abney (1987: 301))

26

3. All Adjectives, Adverbs and Quantifiers share common [+N] feature (Abney

(1987:302)).

Therefore, adjective phrases, quantifier phrases and adverb phrases are identical

in their internal structure.

However, as has already been mentioned, there is a difference between pre-

nominal and post-nominal adjective phrases. According to Abney (1987), pre-nominal

adjective phrases are APs taking an NP as their complement, whereas post-nominal

adjective phrases are in truth Degree Phrases (DegPs).

As can be seen in (30) below, degree words within adjective phrases, e.g. too,

behave similarly to Determiners within nominal expressions. They modify all kinds of

adjective phrases appearing in the initial position, as in (30a) and (30b), and they cannot

be multiplied, as shown in (30c)

(30) a. too many

as hungrily

so long

b. too sick

as happy

c. *as too sick

*too as happy

Therefore, it is natural to claim that Degree words project DegPs and take

adjective phrases as complements, just like Determiners project DPs and take nominal

phrases as therir complements (Abney (1987: 298)). The structure of the DegP with

proper examples is presented by means of a P-maker in (31) below:

27

(31)

DegP

.

DegP

Deg’

Ø

AP

Deg AP

much [+Q]

too

tall

quite [+Adj] as nice

(Abney (1987:306))

As can be seen in (31), Abney’s proposal covers even adjective phrases which

function as modifiers of phrases like too tall that have already been recognized as

DegPs.

The case of pre-nominal adjective phrases is much different. First of all, pre-

nominal adjective phrases cannot take typical PP complements, whereas post nominal

DegPs must have complements, e.g.:

(32) a. the [proud] man

*the [proud of his son] man

b. *the man [proud]

the man [proud of his son]

(Abney (1987:326))

This query can be explained if we assume that instead of a typical PP the pre-

nominal AP takes an NP as its complement. At the same time, it appears that Adjectives

have similar properties to auxiliary verbs within verbal phrases, i.e. appearing as

‘auxiliaries’ they cannot take complements characteristic for their class and they f-select

NPs. Therefore, it is possible to claim that Adjectives are ‘defective’ Nouns, just as

corresponding Auxiliaries are defective Verbs (Abney (1987: 327)). This leads us to the

conclusion that the only structure possible for pre-nominal adjective phrases is the

structure presented in (28b).

28

Conclusion

In this chapter it has been shown that the classical GB structure of nominal phrases,

which treats them as NPs headed by a Noun with a Determiner in the [Spec; NP]

position is inadequate. In the case of Determiners, the GB analysis violates the

constraints of the X-bar theory. What is more, it fails to provide an appropriate

explanation for the cross-linguistic phenomenon of multiple determiners found in

languages of Romance and Slavic groups. In comparison with the structure of CPs, the

GB analysis of NPs ignores the similarities between Determiners and Complementisers,

which suggest that the former may fulfil the same function of introducing the

descriptive content of the phrase. In addition to this, the classical structure does not

explain the difference in understanding the s-projection of clauses and nominal phrases.

Abney’s (1987) proposal of analysing nominal phrases as DPs removes the

deficiencies of the former representation. It also accounts for the phenomena such as:

the argument structure of Poss-ing gerundive constructions, the strong agreement within

the nominal phrase, corresponding to the Inflection in clauses and post-nominal

adjectives in English. The explanation is offered also for the question concerning the

position of adjectives, quantifiers and other elements intervening between a Determiner

and a Noun, which according to Abney project their own projections (DegPs and APs).

29

Chapter 2

Functional projections within the DP

Introduction

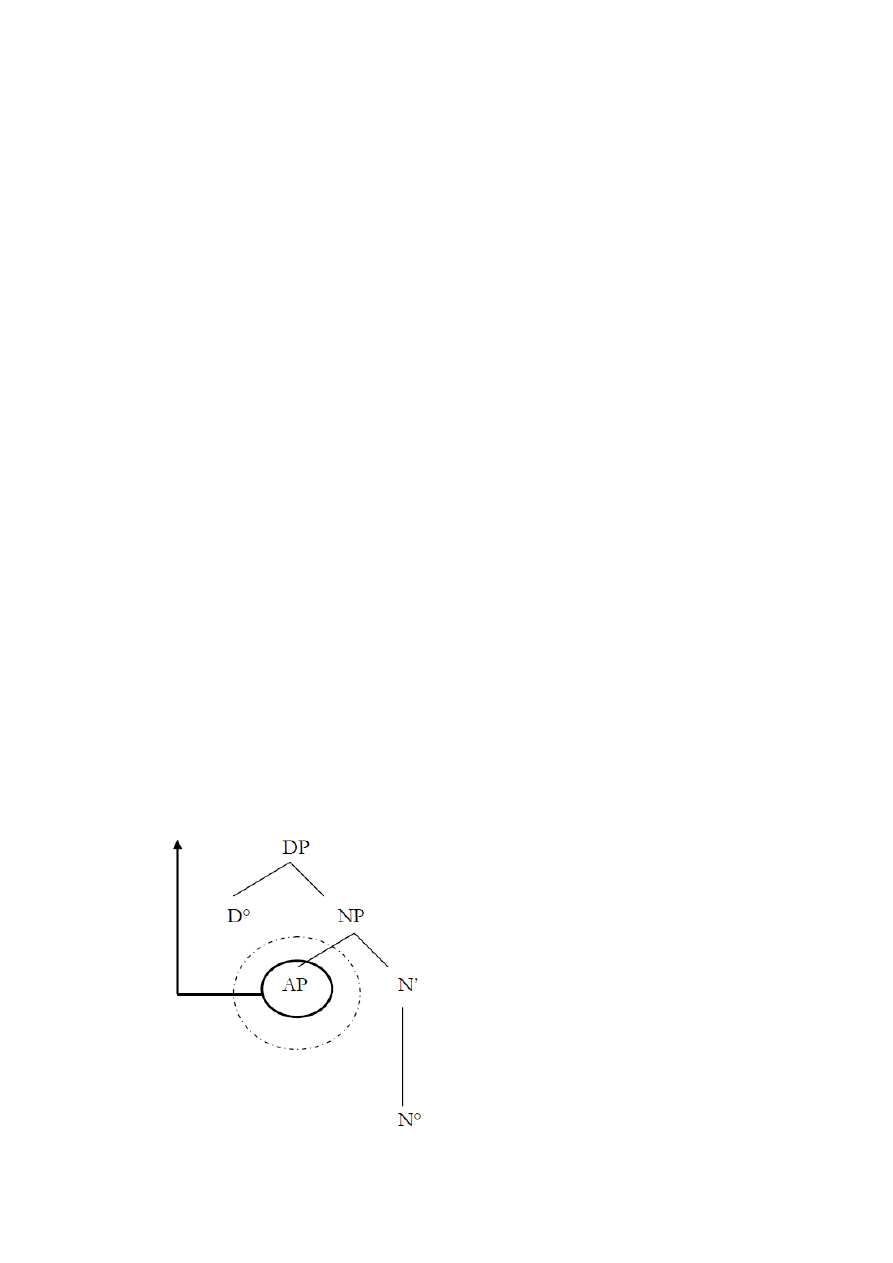

In the first chapter, following Abney (1987), the existence of the Determiner Phrase has

been postulated as a functional projection built upon the Nominal Phrase. A nominal

phrase is headed by a functional element - D, just as a clause is headed by a functional

element I. However, aspiring to a uniformity between nominal and verbal structures,

motivated by the equal importance of both elements for the meaning of a sentence, we

are obliged to analyse the possibility of other functional projections existing within the

DP-projections intervening between the Determiner and its complement – NP, parallel

to projections appearing between an IP and an NP.

Chapter 2 discusses numerous proposals of functional projections appearing

within the DP. Sections 2.1 to 2.3 present an Agreement Phrase (AgrP), a Number

Phrase (NP) and a Quantifier Phrase (QP). Section 2.4 is concerned with the order of

adjectives within a nominal phrase from Cinque’s (1994) and Scott’s (2002)

perspective. Section 2.5 introduces the proposal of nP (a little n). In section 2.6 a

Demonstrative Phrase (DemP) and a Possessive Phrase (PossP) are discussed. Finally,

section 2.6 provides a discussion of the hierarchy of elements appearing within a DP.

30

2.1 AgrP - Agreement Phrase

The issue of agreement between various elements appearing within a DP was

raised by Abney (1987) and introduced as one of the cross-linguistic facts proving the

similarity of verbal and nominal phrases. Agreement is understood to be a feature

carried by the head of the phrase - D (cf. Chapter 1 (13)). It is manifested by proper

forms of nouns and neighbouring elements showing the same number, person or case.

On the basis of Hungarian data, Szabolcsi (1994) postulates the existence of Agreement

as a whole projection intervening between NP and DP. The data demonstrating this

problem are shown in (1).

(1) a. az en kalap-om

the I hat-1

st

sing.

‘my hat’

b. a te kalap-od

the you hat- 2

nd

sing.

‘your hat’

c. a Peter kalap-ja

the Peter- NOM hat-3

rd

sing.

‘Peter’s hat’

As can be seen in (1), Hungarian possessors are marked with nominative case

and show agreement with the noun that follows them. This structure is an exact

reflection of the relation between a subject and a verb within a sentence. What is more,

Hungarian possessors may also occupy frontal position within the nominal phrase,

preceding the article and the noun, as in (2b).

(2) a. a Mari kalap-ja

the Mari- NOM hat-3

rd

sing.

‘Mary’s hat’

31

b. Mari-nak a kalap-ja

Mari- DAT the hat- 3

rd

sing.

‘Mary’s hat’

Szabolcsi (1994) claims that (2b) is derived from (2a). The possessor Mari

occupying the position of [Spec; AgrP] moves leftwards to the [Spec; DP] where it is

assigned the dative case. The structure introduced by Szabolcsi is as follows (cf. (1a-c)

and (2a-b)):

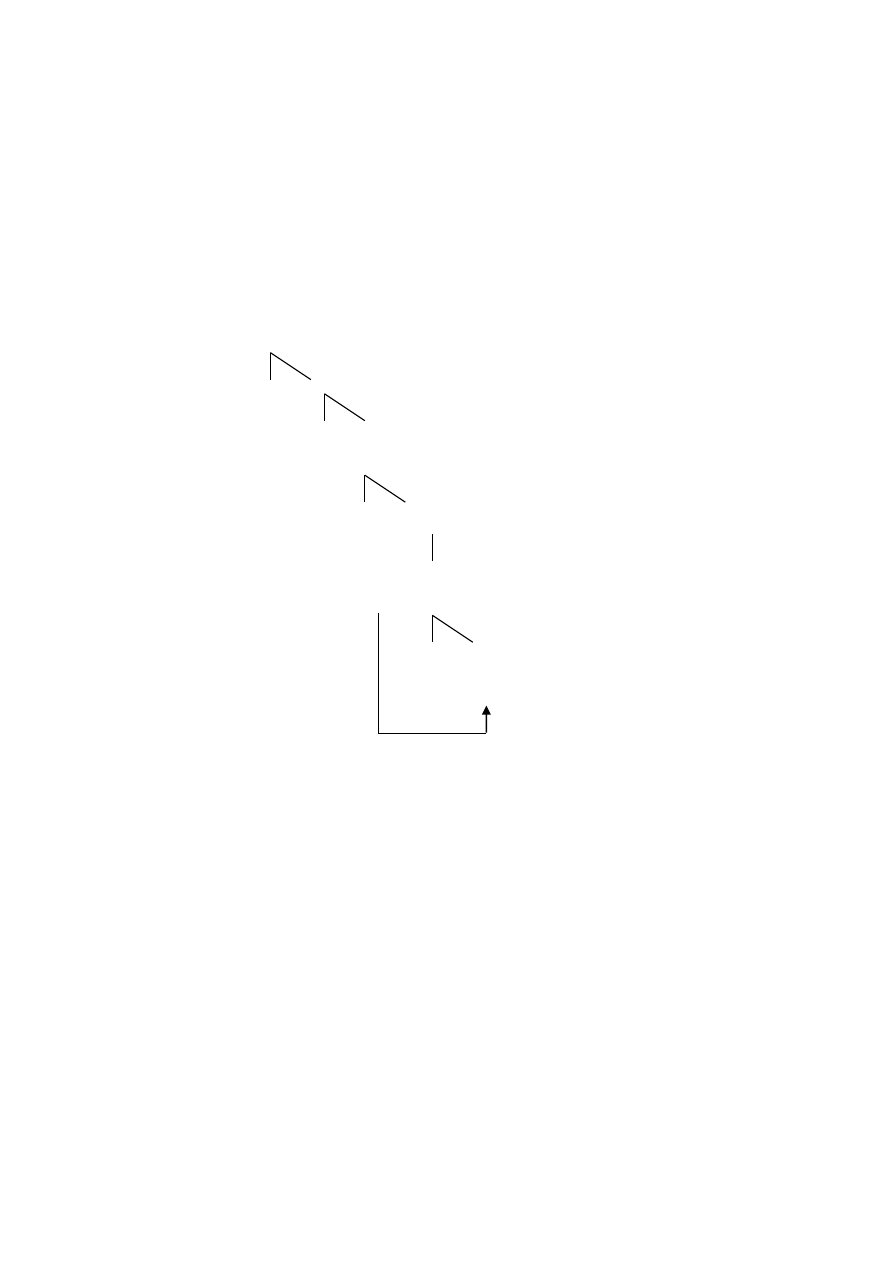

(3) DP

Spec

D’

D

AgrP

Spec Agr’

Agr

NP

az

en

-om

kalap

a

te

-od

kalap

a

Peter -ja

kalap

a

Mari -ja

kalap

Mari- nak

i

a

t

i

-ja

kalap

Another piece of evidence in favour of the AgrP is based on the comparative

analysis of the position of particular adjectives in Romance and Germanic languages

and parametrised N-to-Agr movement postulated by Cinque (1994). By comparing

English and Italian data, it can be seen that some adjectives appearing prenominally in

English follow the noun in Italian (cf. (4 a-b)).

(4) a. the beautifu big red ball

[English]

b. la bella grande palla rossa

[Italian]

the beautiful big ball red

(Cinque (1994;93))

32

The classical GB analysis of Adjective Phrases assumes that they are attached to

the nominal phrase by adjunction. Due to the fact that they are neither complements nor

specifiers of the Noun Phrase they can recursively occur in the position intervening

between nouns and determiners and therefore create the structure presented in (5)

below.

(5) N’’

Spec N’

AP N’

AP

N’

AP

N’

N

(Radford (1988: 201))

However, the structure in (5) does not account for the data in (4) – it is actually

just the opposite: it creates a conceptually unsatisfactory result of allowing left-

adjunction in Germanic languages but right-adjunction in Romance. The structural

difference between the data in (4a-b) can be explained in two ways: either by claiming

that the final adjective in Romance languages is lowered into the position below the

noun, or proposing the leftward movement of a noun from the N position into some

empty head position intervening between the two APs.

Cinque (1994) supports the thesis of leftward noun movement. The piece of

evidence he produces is based on similar verb movement present in both language

33

groups (i.e. the obligatory raising of a finite V). As a result, the following structure is

postulated:

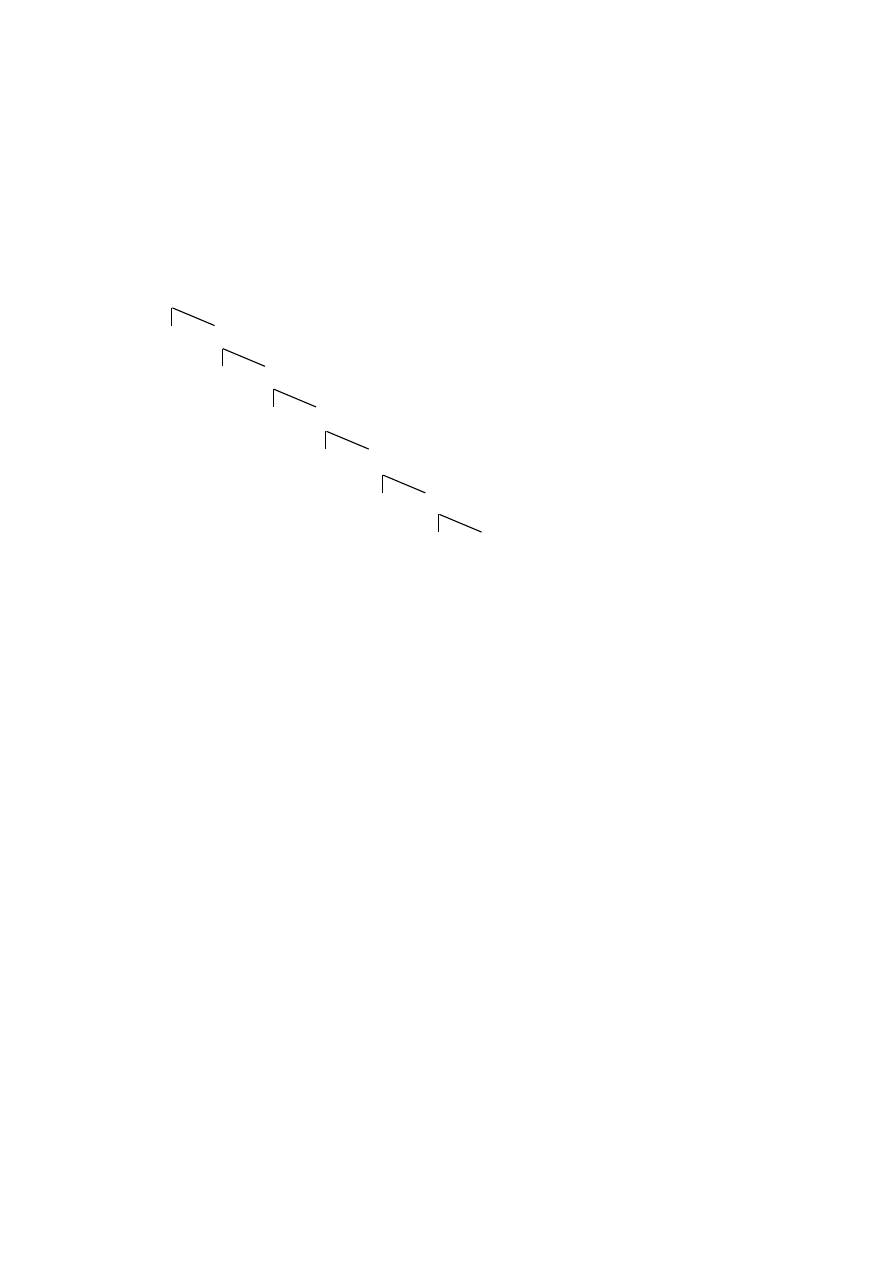

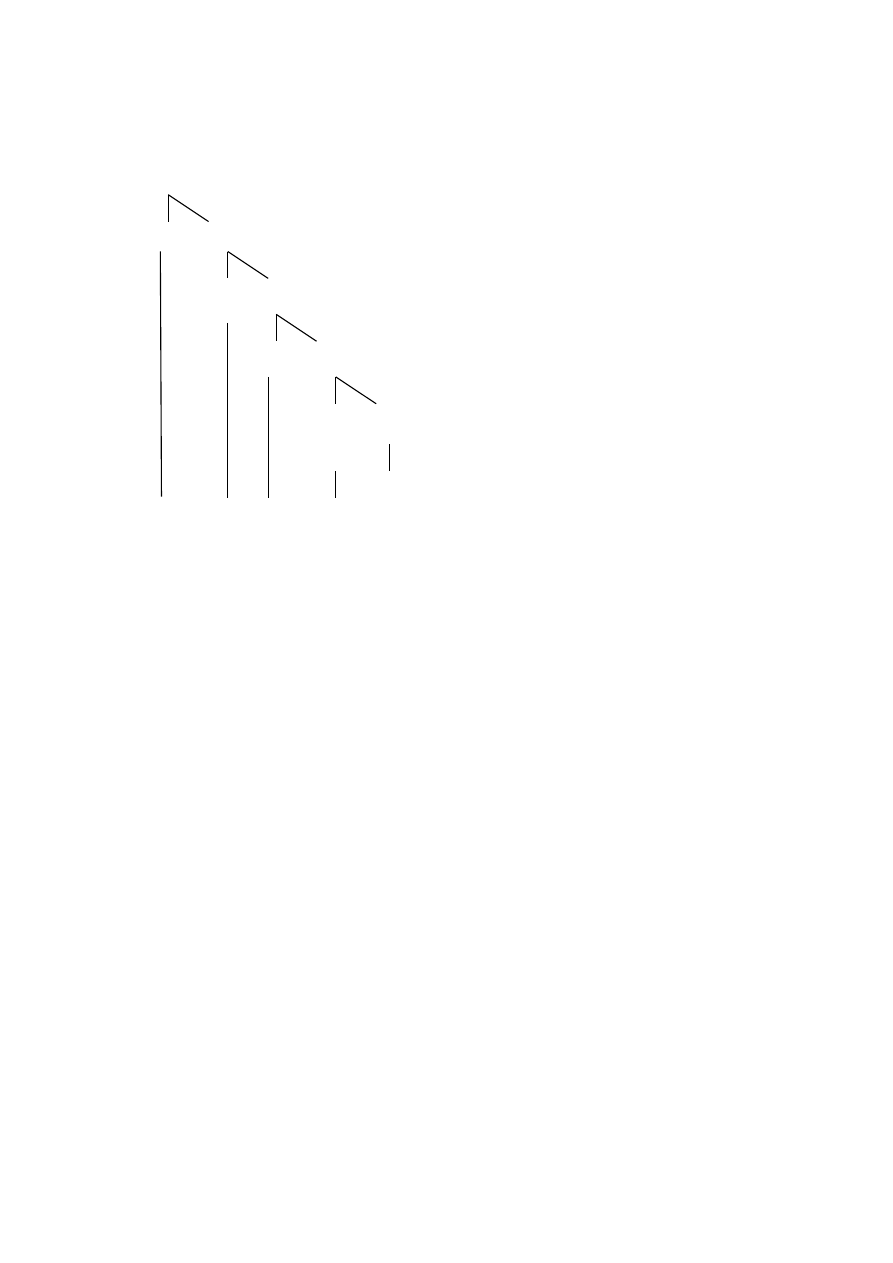

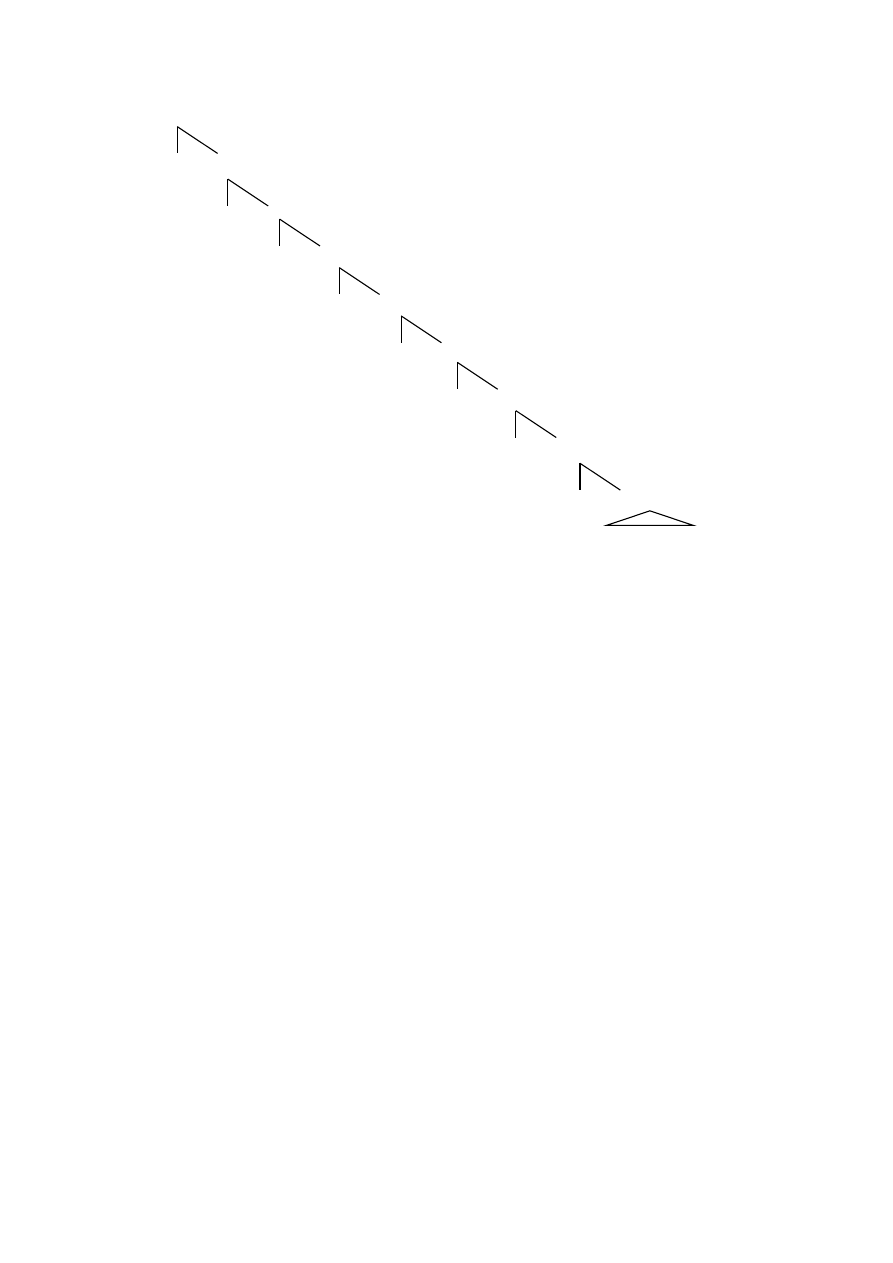

(6) DP

Spec D’

D AgrP

Spec Agr’

AP

Agr AgrP

Spec Agr’

AP

Agr AgrP

Spec Agr’

AP

Agr NP

N’

N

a.

the beautiful

big red ball

b.

la bella

grande palla

i

rossa

t

i

As can be seen in (6), Cinque rejects the classical GB interpretation of adjectives

treated as adjuncts of the NP, adjoined to the N’ and expanding it into another N’, and

places them in the position of [Spec;AgrP]. This leaves us with empty Agr head

positions within each AgrP, constituting possible landing sites for head-to-head

movement. At the same time, the conceptually unsatisfactory difference between left-

34

and right-adjunction ceases to exist. Therefore, the noun – adjective order within a DP

may differ across languages.

2.2 NumP- Number Phrase

On the basis of data from Celtic and Semitic languages the notion of Number

Phrase has been developed (Ritter (1988, 1991), Duffield (1995), Mohammad (1988),

Lyons (1997), among others). The elements of nominal phrases in these languages show

strong agreement with respect to number and gender. Therefore, although all the lexical

elements originate within the NP, they are moved higher to be assigned case (the head

noun) or to gain the proper number and gender (modifying elements – possessors)

(Ritter (1991)).

The structure proposed by Duffield (1995), after Ritter (1991) and others, with

proper examples is presented in (7) below:

35

(7) DP

Spec D’

D AgrP

Spec Agr’

Agr NumP

Spec Num’

Num NP

AP NP

Spec

N

a. sieq

i

Willy

j

t

i

t

i

l-leminija t

j

t

i

b. guth

i

t

i

t

i

aidir an tsagairt t

i

c. an leabhar

i

nua

t

i

a. sieq Willy l-leminija

[Hebrew]

foot-fem. sing. Willy the-right-fem. sing.

‘Willy’s right foot’

b. guth aidir an tsagairt

[Irish]

voice strong the priest-GEN

‘the priest’s powerful voice’

c. an leabhar nua

[Irish]

the book new

‘the new book’ (Duffield (1995: 309)

Assuming that the core position of all elements within a phrase is universal for

all languages, the same structure should appear in Celtic and in Semitic languages.

36

Therefore, the basic position of both the modifying adjective phrase and the possessor is

on the left-hand side of the Noun. The possessor, later on, moves to its target site from

the A’-position in [Spec;NP] to the [Spec;AgrP]. The functional projection of Number

caries the features of number and gender, and provides the landing site for the Noun.

The head noun is said to move from the N position to the functional position of Num

which accounts for the leftward position of the head noun in relation to the possessor

and modifying adjective phrases. In Irish, the Noun undergoes head-to-head movement

either to Num or to D if the latter is not occupied by some other element (cf. (7b) and

(7c)).

The NumP is one of the first functional projections claimed to appear between a

DP and an NP. However, there is no proof for its existence in Germanic and Slavic

languages. Therefore it will not be mentioned in Chapter 3, devoted to the structure of

Polish nominals.

2.3. QP - Quantifier Phrase

Apart from articles, possessors and demonstratives, another important group of

modifiers are quantifiers (e.g. some, many, all, (a) little, (a) few etc.). Although they are

in the complementary distribution with articles, they are recognized as a different class

requiring their own projection within the nominal phrase – a Quantifier Phrase.

However, the position of the Quantifier Phrase is not explicit. Following Giusti (1991,

1997), we must consider the existence of three different groups of quantifiers appearing

in different positions: quantifiers which must precede an article, as in (8), quantifiers

37

that may follow an article, as in (9), and quantifiers that do not co-occur with articles, as

in (10):

(8) a. tutti *(i) ragazzi

‘all the children’

b. *i tutti ragazzi

c. li ho visti tutti

‘I saw them all’

(9) a. molti Ø *i ragazzi

‘many boys’

b. i molti ragazzi

‘the many boys’

c. ne ho visti molti/ *ne ho visti i molti

‘I saw many of them’

(10) a. alcuni/ *i ragazzi

‘some boys’

b. ne ho visti alcuni .

‘I saw some of them’

(Giusti (1997: 114))

The quantifiers like molti ‘many’ behave like adjectives. They follow the article

and, when placed in the phrase initial position, they cause the expression to become

ungrammatical (cf. (9a) and (9b)). At the same time, they show agreement with regard

to umber and gender with the head noun. Therefore, it is possible to claim that, in fact,

they belong to the same lexical class as common adjectives. Consequently, just as

adjectives, they appear in a DP internal position of the high [Spec; AgrP], as shown in

(11) below.

38

(11) DP

D

AgrP

Spec Agr’

Agr

NP

Spec N’

AP

N

i due ragazzi simpatici t

i

the

two boys nice

(Giusti (1997: 115))

A piece of evidence supporting this theory is to be found in Romanian

encliticised definite article (Giusti (1991)). In Romanian, the definite article

encliticcises on the leftmost element of the nominal phrase: a noun or an adjective

moved into the D position. The same rule applies in the case of quantifiers and,

therefore, it is possible to claim that they do function as adjectives. As shown in (12) the

quantifier ambi ‘both,’ as well as the adjective frumosi ‘nice,' carries the encliticcsed

article.

(12) a. ambii baieti

both-the children

b. frumosii baieti

nice-the children

(Giusti (1994: 120))

39

However, according to Giusti (1991, 1994, 1997) not all quantifiers have the

same properties. The quantifiers as tutti 'all’ display selectional properties over the DP

they are followed by. They require the nominal phrase to be definite, therefore they are

followed by the article + noun construction as has been shown in (8a-b). The

explanation for this phenomenon proposed by Giusti (1991) is as follows: quantifiers

that are followed by articles are in fact external to DP and create their own projection

above the whole DP as shown in (13) below (cf. (8a)):

(13) QP

Spec Q’

Q DP

tutti

i ragazzi

all

the boys

(Giusti (1997. 114))

This analysis is repeated by Giusti and Leko (1995) in the context of pronominal

DPs modified by the quantifier tutti ‘all’ in Italian and its equivalents in French and

English. Comparing the data in (14a-c), with typical constructions of tutti + nominal

DP, as, for instance, in (8) and (13), they propose the structure shown in (15).

(14) a. voi/ noi tutti

[Italian]

b. nous/ vous tous

[French]

c. you/ we all

[English]

40

(15) QP

Spec Q’

Q DP

voi/noi

i

tutti

t

i

vous/nous

i

tous

t

i

you/we

i

all

t

i

According to Giusti and Leko (1995), pronouns originate within the DP and are

moved upwards to the [Spec; QP] position, as opposed to typical nominal DPs shown in

(13), which stay in the lower parts of the phrase. This claim, however, is highly

questionable. There seems to be no reason for the pronoun rising (this is not

syntactically motivated). What is more, Polish data discussed by Rutkowski (2002c)

constitute a clear set of counterarguments. The Polish equivalent of the quantifier tutti-

wszyscy, which behaves exactly like regular adjectives, shows strong agreement in

terms of case, number and gender with the head noun, as well as with the pronoun (cf.

(16)).

(16)

a. [wszyscy lingwiści] czytali mój artykuł

all linguists read my article

‘all linguists read my article’

b. [wy wszyscy] czytaliście mój artykuł

you all

read

my article

‘you all read my article’

c. *[wszyscy wy] czytaliście mój artykuł

all

you read

my article

(Rutkowski (2002c:163))

41

On the basis of data in (16), Rutkowski (2001, 2002a, 2002c) claims that both

the quantifier and pronoun are DP internal. The quantifier wszyscy is placed in the head

Q position and takes a complement, i.e. NP. The pronoun originates within the NP and

it is moved to the D position as a result of the N-to-D raising of pronouns. This leads to

the uniformity of the basic structure of Quantifier Phrase and neutralises the artificial

division of quantifiers. Rutkowski’s proposal is represented in the P-maker below.

(17) DP

Spec D’

D

QP

Spec

Q’

Q NP

GEN (Q)

wy-Gen

i

wszyscy

t

i

(Rutkowski (2007b:88))

However, the structure given by Rutkowski (2007b) is quite problematic.

According to the Head Movement Constraint, the element moved passes through each

head position intervening between the original and target positions. Here, the pronoun

wy skips an intervening Q, which is already occupied by wszyscy.

42

2.4 The order of adjectives

According to Abney (1987) (cf. Chapter 1, 1.3), adjectives constitute two separate

groups: pre-nominal adjectives, which form their own functional projection appearing in

the position intervening between a DP and an NP, and post-nominal adjectives, which

appear within Degree Phrases bellow the NP. What is more, adjectives are said to be

‘defective’ Nouns and fulfil similar functions within a DP as Auxiliaries within a CP.

However, there are some inconsistencies in Abney’s analysis of adjectives and

other components of the DP Hypothesis. According to Abney, Auxiliaries and

Determiners, being functional elements, are members of a closed class. They do not

contribute significantly to the meaning of the clause and are inseparable from the lexical

element they introduce. Adjectives, though claimed to be functional elements too, do

not match this description – they are members of an open lexical class, they can be

separated from the noun, and they do contribute to the meaning. At the same time, the

existence of post-nominal adjectives (the trigger for Abney’s interpretation) constitutes

the basis for Cinque’s (1994) analysis of Agreement Phrase (cf. Chapter 2, 2.1), which

postulates that APs occurring within a DP occupy the position of [Spec;AgrP] (cf. (6)).

Another query that stays unsolved under Abney’s analysis is the order of

Adjectives. In most languages elements modifying nouns have a strict and highly

restricted order of appearance. Each adjective appearing within a DP must be placed in

a proper position according to the semantic group it belongs to. According to the

research conducted by Pereltsvaig (2007), only 11.5% of native speakers of Russian do

not follow the universal order of adjectives. In this case Cinque’s (1994) analysis of

APs seems to be more justified. According to him, Adjective Phrases placed within

functional projections undergo selection under the conditions placed by the functional

43

head. Therefore, it is claimed that each Agreement Phrase hosting an AP within it

carries one of the attributive features, the order of which is as follows:

(18) possessor> cardinal> ordinal> quality> size> shape> colour> nationality

(Cinque (1994: 96))

The model presented by Cinque has undergone numerous modifications and

reshapings. New projections have been postulated and the analysis became more

detailed and specific. Scott’s (2002) analysis constitutes a good example of such

modification. According to Scott (2002), the number of AP-related functional

projections within a DP in much bigger than the eight introduced by Cinque (1994). The

universal hierarchy of DP elements proposed by him is as follows:

(19) Det> ordinal number> cardinal number> subjective comment> evidential>

size> length> height> speed> depth> width> weight> temperature> wetness>

age> shape> colour> nationality/origin> material> compound element> NP

(Scott (2002;114))

The application of the model is presented in (20) below.

44

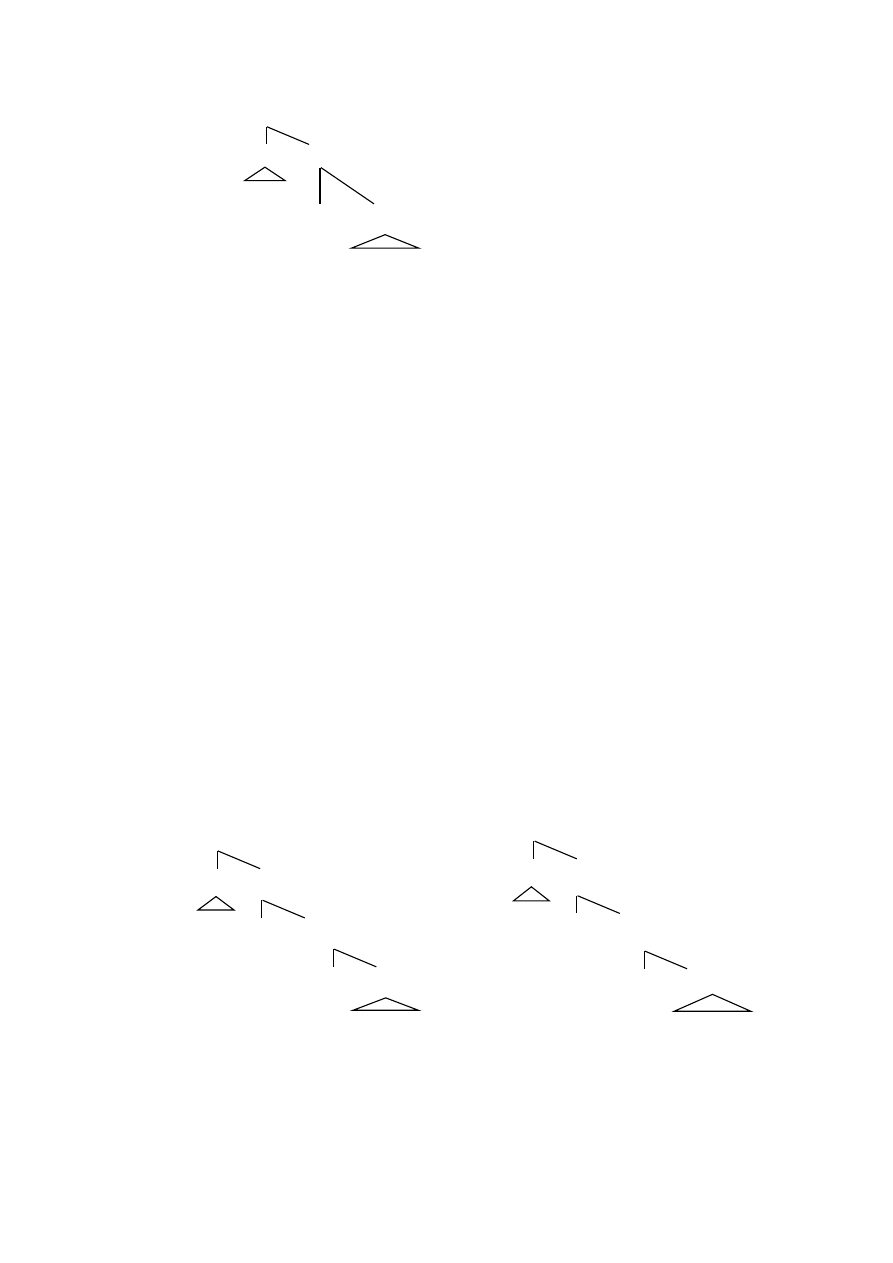

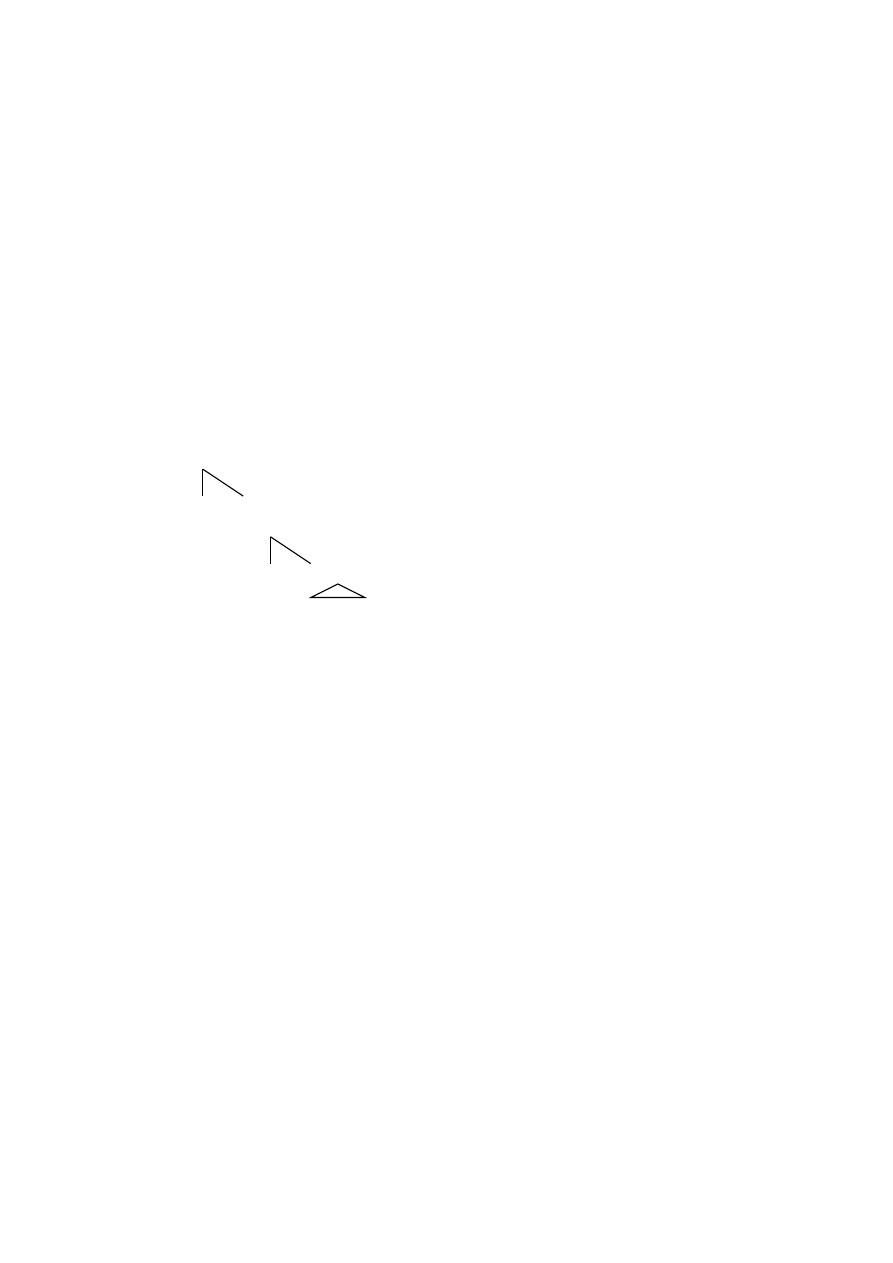

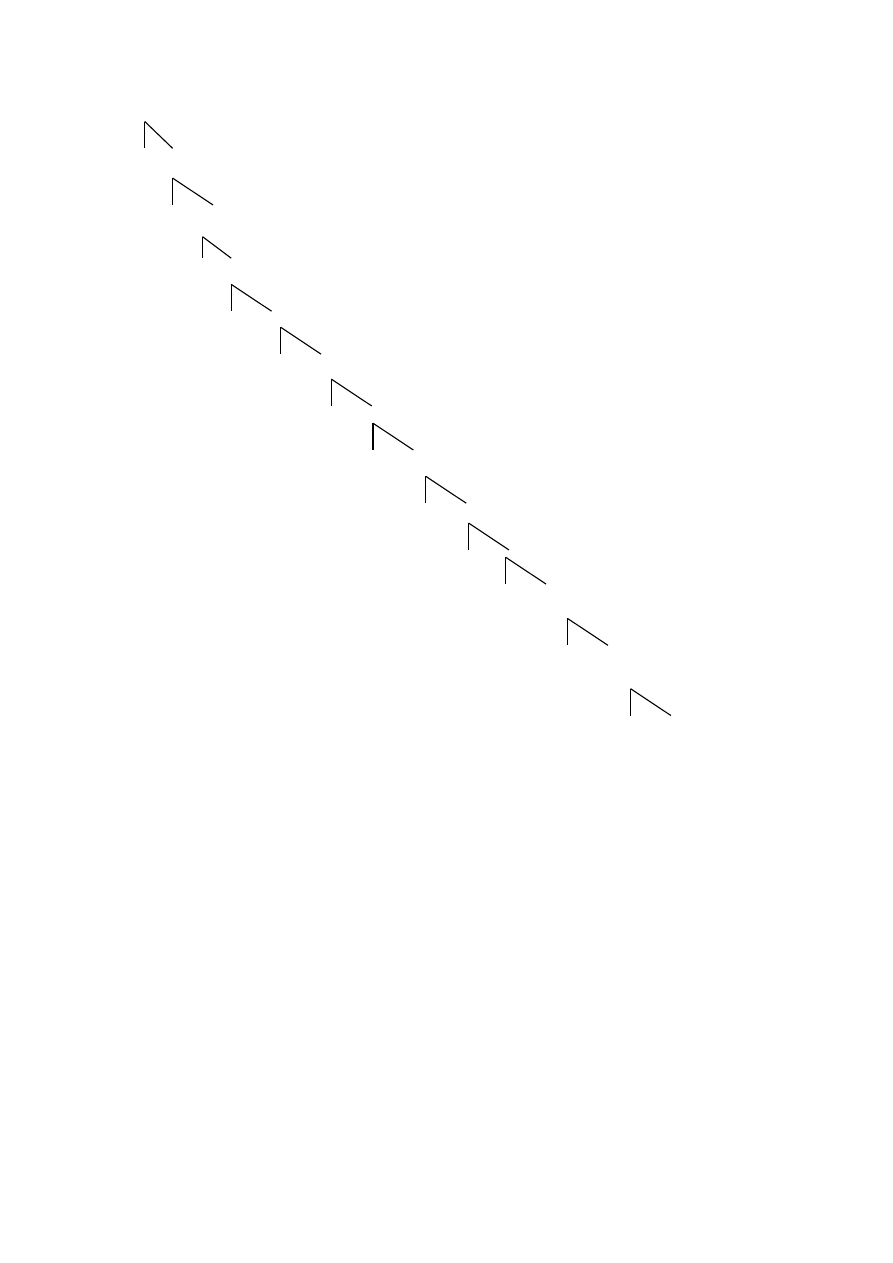

(20) DP

D

D’

AdvP Subj. CommentP

AP

Subj. CommentP’

e

SizeP

e LengthP

AP LengthP’

(Scott (2002:106))

e ColourP

AP Colour P’

e

NP

What is more, Scott (2002) introduces the notion of Focus Phrase appearing

within the DP as an instance of another functional projection – the landing site for

elements undergoing preposing, i.e. the movement of the emphasised element towards

the left side of the phrase. The emphatic use of preposing in English is not uncommon.

The process can be applied even for more than one constituent. The emphasised

elements are moved to the [Spec;FocP] position, appearing below the DP, as shown in

(21).

(21) a. It’s [

DP

the green

i

big t

i

chair] that I want.

b. It’s [

DP

the old

j

green

i

big t

j

t

i

chair] that I want.

c. It’s [

DP

the nice green

i

big t

i

chair] that I want.

d. It’s [

DP

the nice green

i

old

j

big t

j

t

i

chair] that I want.

e.

[

DP

Carol’s horrible

i

six t

i

children] made life miserable for her second husband.

(Scott (2002: 113))

really

that

cool

long

red

dress

45

f.

DP

D’

D FocP

AP

FocP’

e

SizeP

AP ColourP

AP ColourP’

e

NP

All the proposals made by both Cinque (1994) and Scott (2002) are based

on the assumption that the order of adjectives within a nominal expression is

syntactically motivated and the influence of the speaker’s interpretation ends where the

preposing starts (Rutkowski (2007b)). Therefore, it is possible to assume that both

structures are universal. However, a more complex structure introduced by Scott (2002)

precisely exhausts the subject.

2.5 Little n - the nominal shells

One of the most awkward syntactic questions concerns the structure of constructions

with a ditransitive verb. According to the basic GB-theory assumptions, there could be

only one complement within a phrase and, due to this fact, the idea of the indirect object

being an additional complement is unacceptable. The analysis developed by Larson

(1988) and updated by Chomsky (1995a) casts light on this case. The analysis is as

the

green

i

big

t

i

chair

46

follows: a verbal phrase consists of two verbal projections – shells; the lower shell is the

projection of a lexical verb, whereas the higher one is the projection of a light verb - v,

which is given a null spell-out and whose meaning is closely connected with the

meaning of its complement. At the beginning, the lexical verb is merged between the

two objects, then it is adjoined to the light verb – v, which is strongly affixal in nature

and triggers the Move operation. An example structure is given in (22) below.

(22) a. Mary gave a book to John.

b. vP

Mary v’

v

0

VP

gave v

0

[

DP

a book] V’

V [

PP

to John]

gave

(Hornstein et al. (2005: 99))

The structure in (22) remains in agreement with The Uniformity of Theta

Assignment Hypothesis (UTAH) (Baker (1988, 1997)), which requires linking specific

theta-roles to particular positions in initial syntactic structure. And therefore the Theme

theta-role must be assigned to a book in the object position, the Goal theta-role to John,

and the Agent role must be assigned to Mary in the subject position.

Assuming that the structure of nominal expressions is similar or even identical

with the structure of verbal expressions, the existence of little n within the DP has been

proposed (cf.Valois (1996), Bhattacharya (1998), and many others). The little n selects

47

an NP and introduces an Agent. The surface order, again, appears to be the result of

Move operation (Adger (2003)). An example structure is presented below:

(23) a. Richard’s gift of the helicopter to the hospital

b. DP

Richard’s D’

D nP

Richard

n’

n

0

NP

gift

n

0

of the helicopter N’

gift to the hospital

(Adger (2003: 268))

The motivation for the existence of the little n is the case checking of the

nominal elements within the DP. D checks the Genitive case of the Agent and having a

strong [gen] feature causes the movement of the Agent from the [Spec;nP] position in

order to satisfy the locality requirement. The little n carries the weak [of] feature and,

due to this, it checks the case of the of-Phrase but does not cause movement (Adger

(2003)).

A more recent interpretation of this structure is presented by Radford (2004).

According to him, a lexical noun gift merges with its internal arguments: a Goal to the

hospital and a Theme of the helicopter. Then the NP merges with a little n, whose

specifier corresponds to the Agent phrase Richard. The little n is strongly affixal in

nature and therefore triggers the movement of the Noun. The whole nP merges with a

48

DP headed by a null Determiner. The null Determiner is able to assign the Genitive

case to the nominal Richard. The null D carries the [EPP] feature requiring it to be

extended into a DP projection with a proper specifier. As a result it triggers the

movement of the Richard to the [Spec; DP] position.

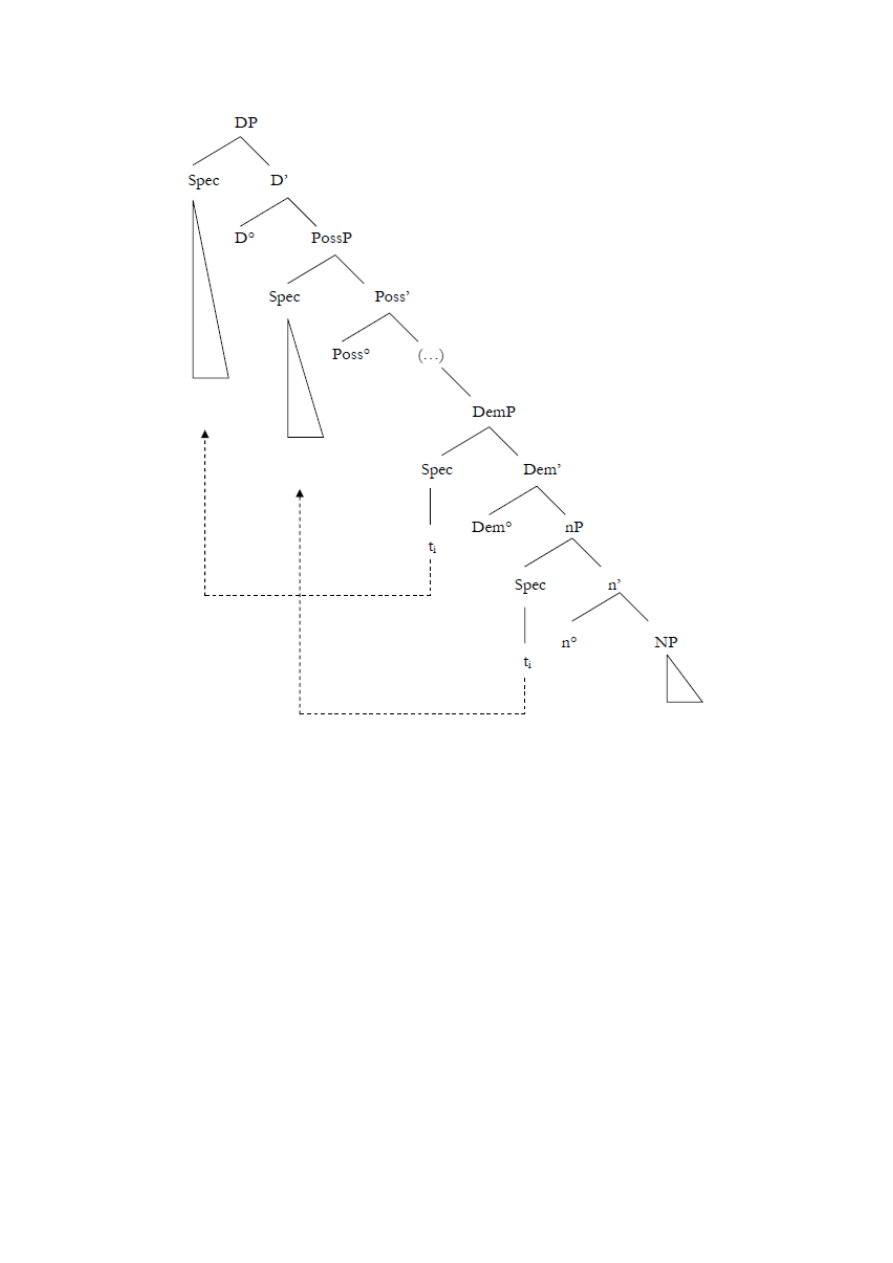

2.6 DemP – Demonstrative Phrase and PossP - Possessive Phrase

According to Abney (1987), articles, demonstratives and possessives occupy the same

syntactic position, i.e. a D position. This assumption is confirmed by the fact that those

elements in English are in complementary distribution. However, it is inconsistent with

the data taken from other Germanic, Romance and Slavic languages.

(24)

a. ta moja książka

[Polish]

this my book

‘this book of mine’

b. diese unserve wunderbaren Bücher

[German]

these our wonderful books

‘these wonderful books of ours’

(Rutkowski (2007b: 257-258))

As shown in (24) above, in some languages both possessive and demonstrative

pronouns can appear within one nominal phrase. Taking into consideration the data in

(24) it is no longer possible to claim that possessives and demonstratives occupy the

same position within the syntactic structure. What is more, they show agreement with

the Noun they modify, therefore, they are similar in syntactic behaviour rather to lexical

not to functional elements (Zlatić (1997)). In traditional perspective, Agreement is said

to involve a c-command relation between a modifier and an element modified, i.e. they

49

must fill a specifier and a head positions. To account for the presence of overt

agreement in the data in (24), it is possible to claim that both pronominal elements

occupy [Spec; XP] position. Due to the fact that a demonstrative pronoun usually

appears phrase-initially, Lecko (1999) suggests that it occupies [Spec, DP] position.

Then, a possessive pronoun must be placed in different Spec position. According to

Veselovská (1995), it appears within a Possessive Phrase, placed closely below a DP

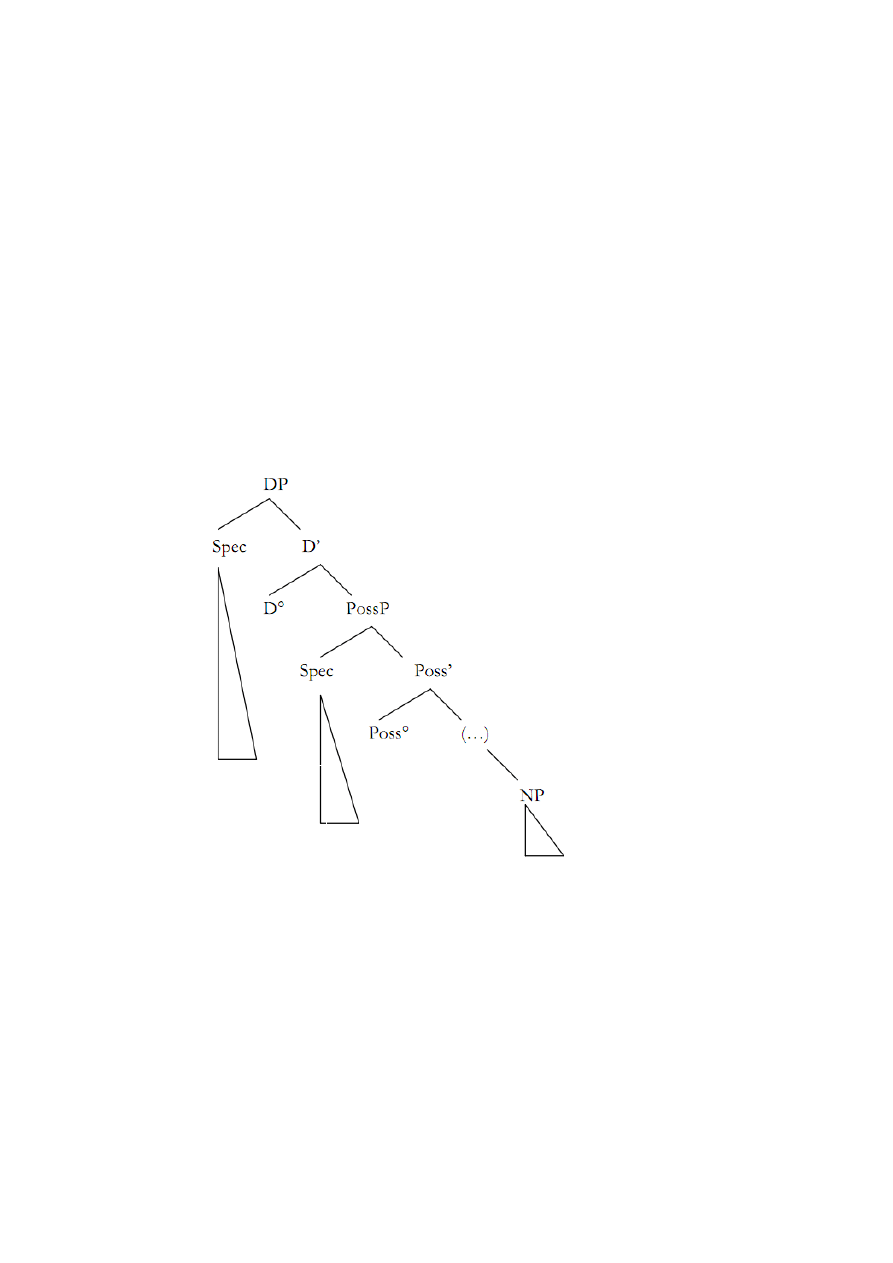

projection. The structure steaming from the analysis presented above is shown in (25):

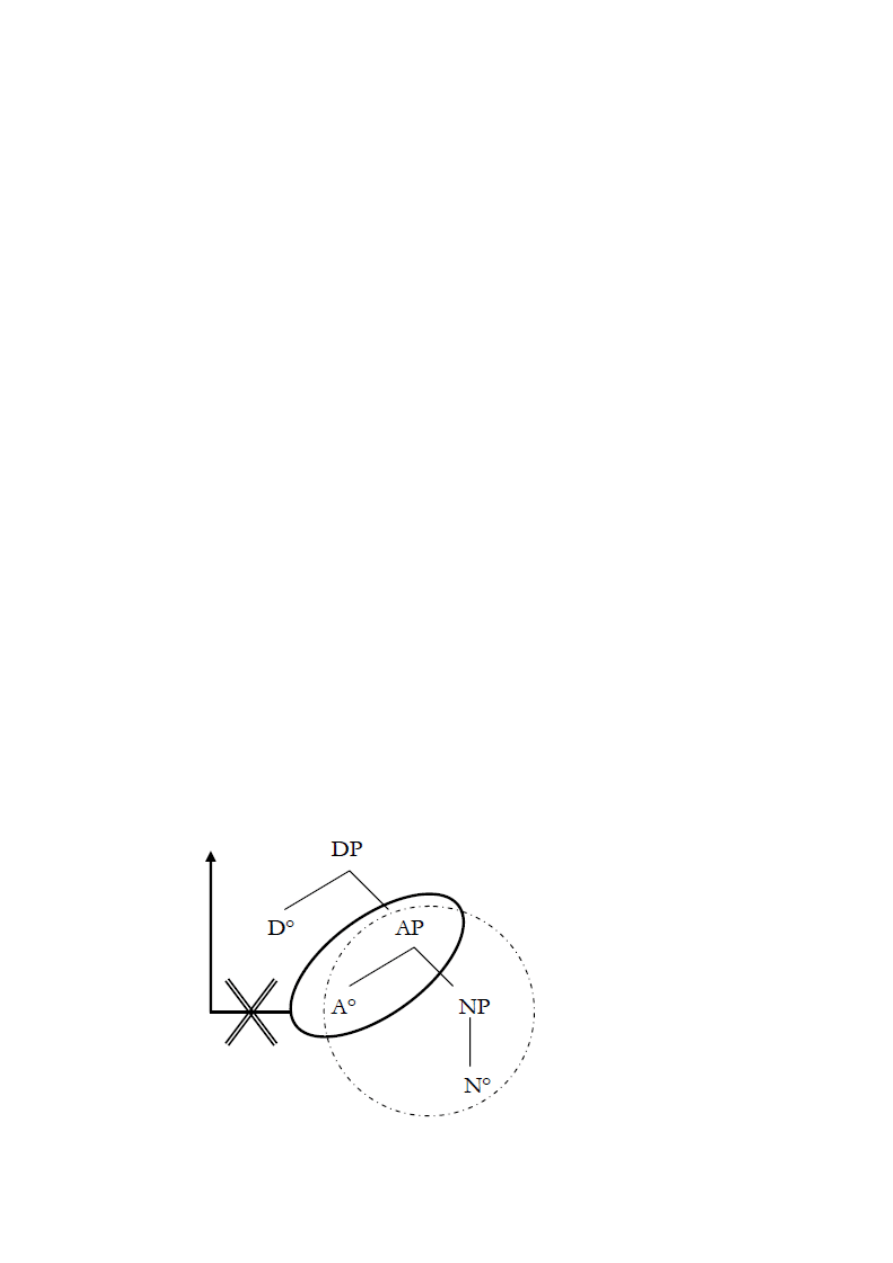

(25)

(Rutkowski (2007b:258))

According to Giusti (1997), the structure given in (25) above illustrates only the

final word order, which is a result of movements appearing during the derivation. This

is confirmed on the basis of data taken from Spanish presented in (26) below:

POSSESSIVE

PRONOUN

DEMONSTRATIVE

PRONOUN

NOUN

50

(26) a. este

libro

this- masc. sing book

‘this book’

b. el libro este

the book this-masc. sing.

‘this book’

c. *el este libro

the this-masc.sing. book

‘this book’

d. *este el libro

this-masc. sing. the book

‘this book’

(Rutkowski (2007b: 259-261))

As shown in (26), the demonstrative pronoun este may precede, as well as,

follow the noun. Giusti (1997) claims that a Demonstrative- Noun order presented in

(26a) is a result of a movent of the Noun. The overt agreement between the Noun and

the modifier may apply only if they are in a c-command relation, therefore it is not

possible to claim that a demonstrative originates lower in the structure than a Noun. As

far as the position of the Demonstrative is concerned, it can be neither a [Spec; DP] nor

a D position. The D position is already occupied by a definite article el (cf. (26 b-d)),

whilst the construction with a Demonstrative in [Spec; DP] position is ungrammatical

(cf. (26d)). Therefore, it is possible to claim that a demonstrative pronoun occupies a

specifier position within a Demonstrative Phrase (DemP) - a functional projection

appearing between a DP and an NP. From there it may be moved upward to [Spec; DP]

in order to satisfy the requirements connected with D

0

(Rutkowski (2007b)).

On the basis of the analysis presented above the initial position of possessive

pronouns may be established. In Spanish both demonstrative and possessive pronouns

may appear within one nominal phrase as shown in (27) below:

51

(27) el cuadro

i

redondo este suyo t

i

the picture round this his

‘this found picture of his’

(Rutkowski ( 2007b: 262))

According to Giusti (2002), the final syntax of el cuadro redondo este syuo is a

result of a movement of the Noun cuadro. The rest of the elements stay in their initial

positions. Therefore the possessive pronoun is claimed to appear within a projection

situated closely above the NP but lower than a DemP. Grohmann and Panagiotidis

(2004) suggest that [Spec; nP] should be accepted as the initial position of possessive

pronouns.

2.7 The hierarchy of functional elements within the DP

The issue closing this chapter pertains to the order of functional elements within the DP.

The result of my analysis will be the structure of nominal phrase which I will adopt in

this thesis

As has been shown in section 2.5, gift of the helicopter to the hospital is an nP.

Analysing examples given in (28) below, it is possible to establish the position of the nP

within the structure of DP:

(28) a. Richard’s [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital]

(Adger (2003: 268))

b. my [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital]

c. my generous [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital]

d. Richard’s generous [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital]

e. some generous [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital]

f. *Richard’s [

nP

gift generous of the helicopter to the hospital]

g. *Richard’s [

nP

gift of the helicopter generous to the hospital]

h. *Richard’s [

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital] generous

i. *[

nP

gift of the helicopter to the hospital] some generous

52

As can be seen in (28 a-i), the little n stays lowest within the structure of the DP.

It is preceded by all the other elements, i.e. determiners, possessives, adjectives and

quantifiers. What is more, other functional elements of the DP intervening within the nP

cause the ungrammaticality of the phrase (cf. (28g-h)). On the basis of (28c-d), it may

be concluded that elements appearing under D, Possessives and Quantifiers, precede

APs. Therefore, bearing in mind the stipulations made in the previous sections of this

chapter, a claim could be made that the hierarchy of functional elements is as follows:

(29) DP

my D’

D PossP

my Poss’

Poss QP

Spec Q’

Q AgrP

generous Agr’

Agr nP

Spec n’

n

0

NP

gift

n

0

of the helicopter N’

gift to the hospital

However, there is still one functional projection already discussed but not included

within the structure above – i.e. the Number Phrase. According to Megerdoomian

53

(2008), the position of NumP is between the two nominal shells: the nP and the NP.

Following Travis (1992), Megerdoomian claims that Num carries the information about

the cardinality of the nominal phrase, and when projected, it gives the +SAQ (specified

quantity) interpretation to the noun phrase. This is necessary because this is the way in

which nominals, all marked as mass within the Lexicon, gain the count interpretation

(Megerdoomian (2008: 88) after Borer (2001)).

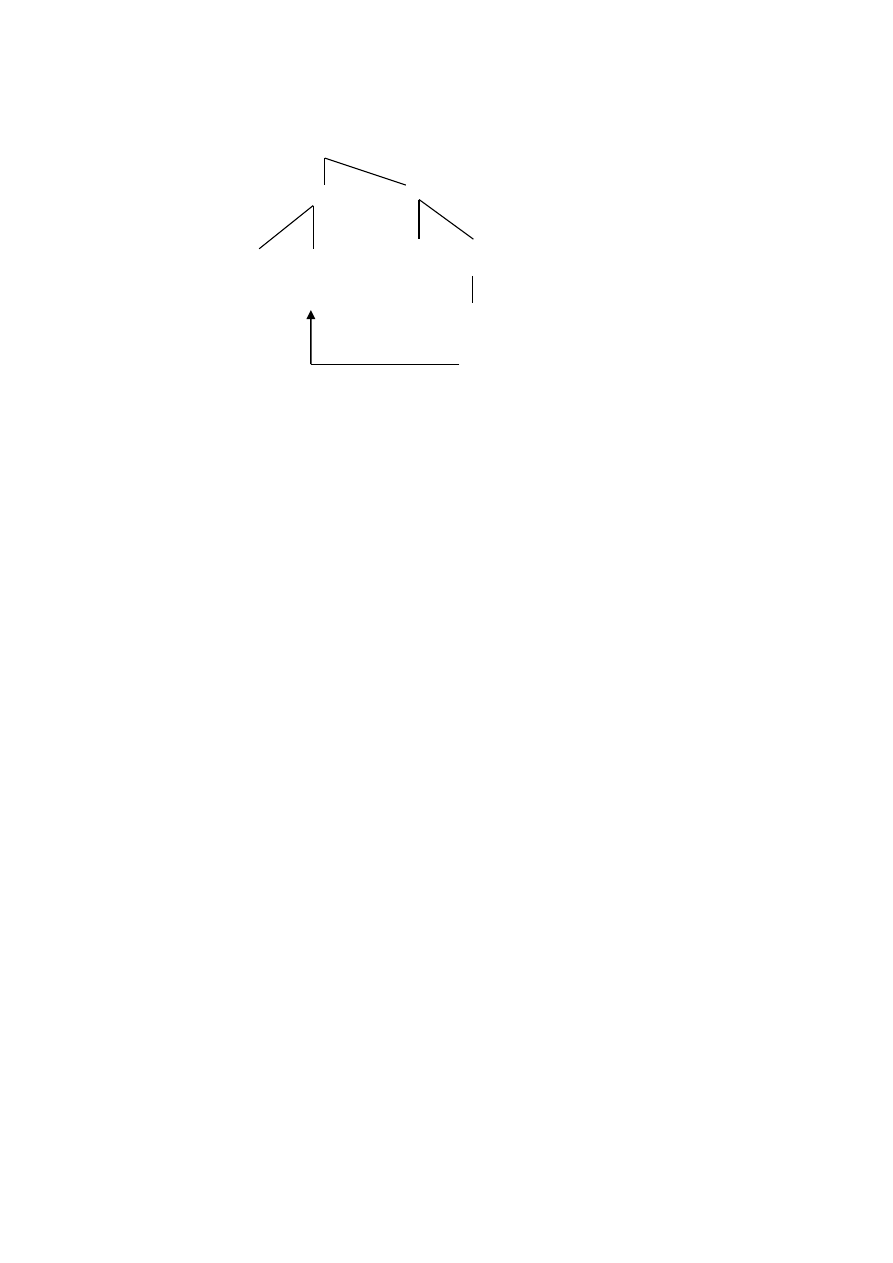

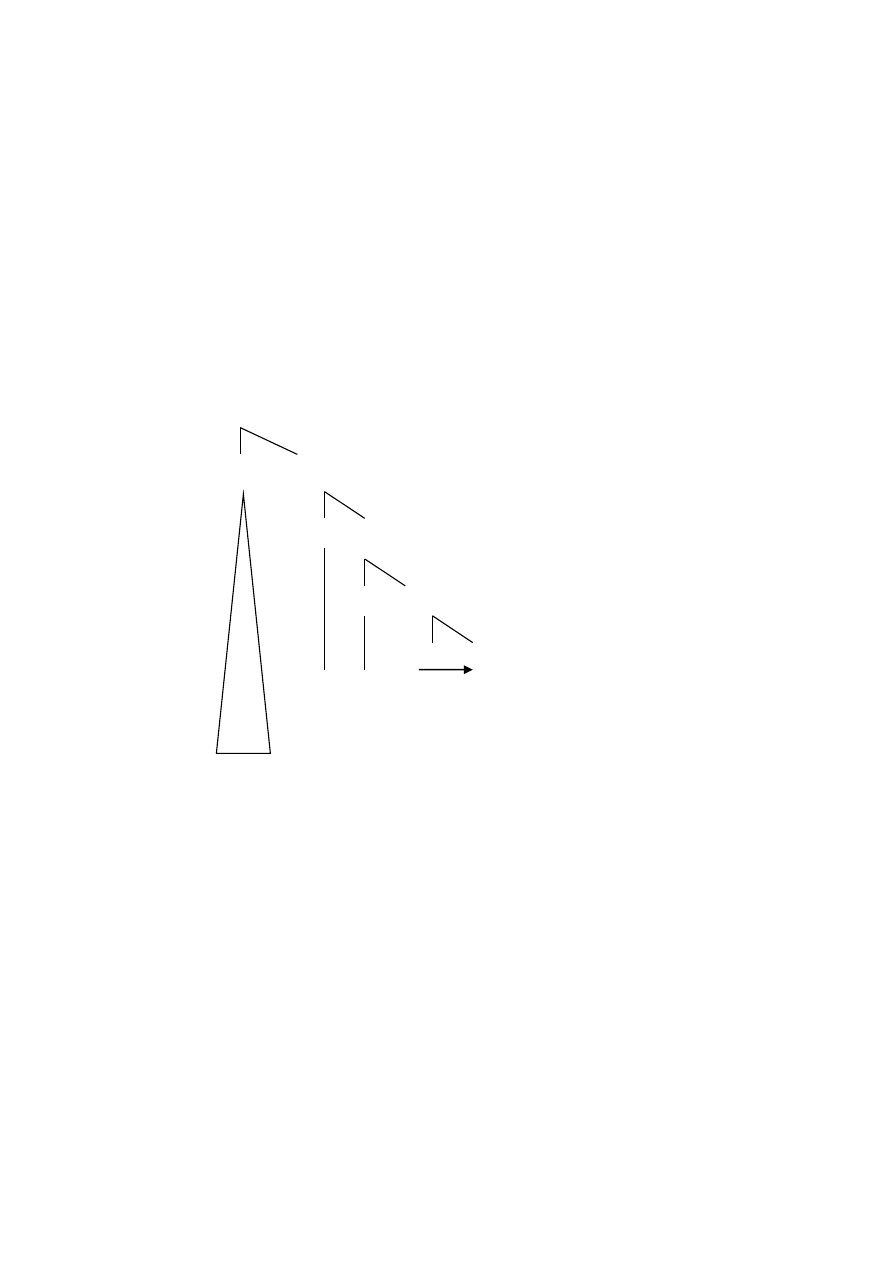

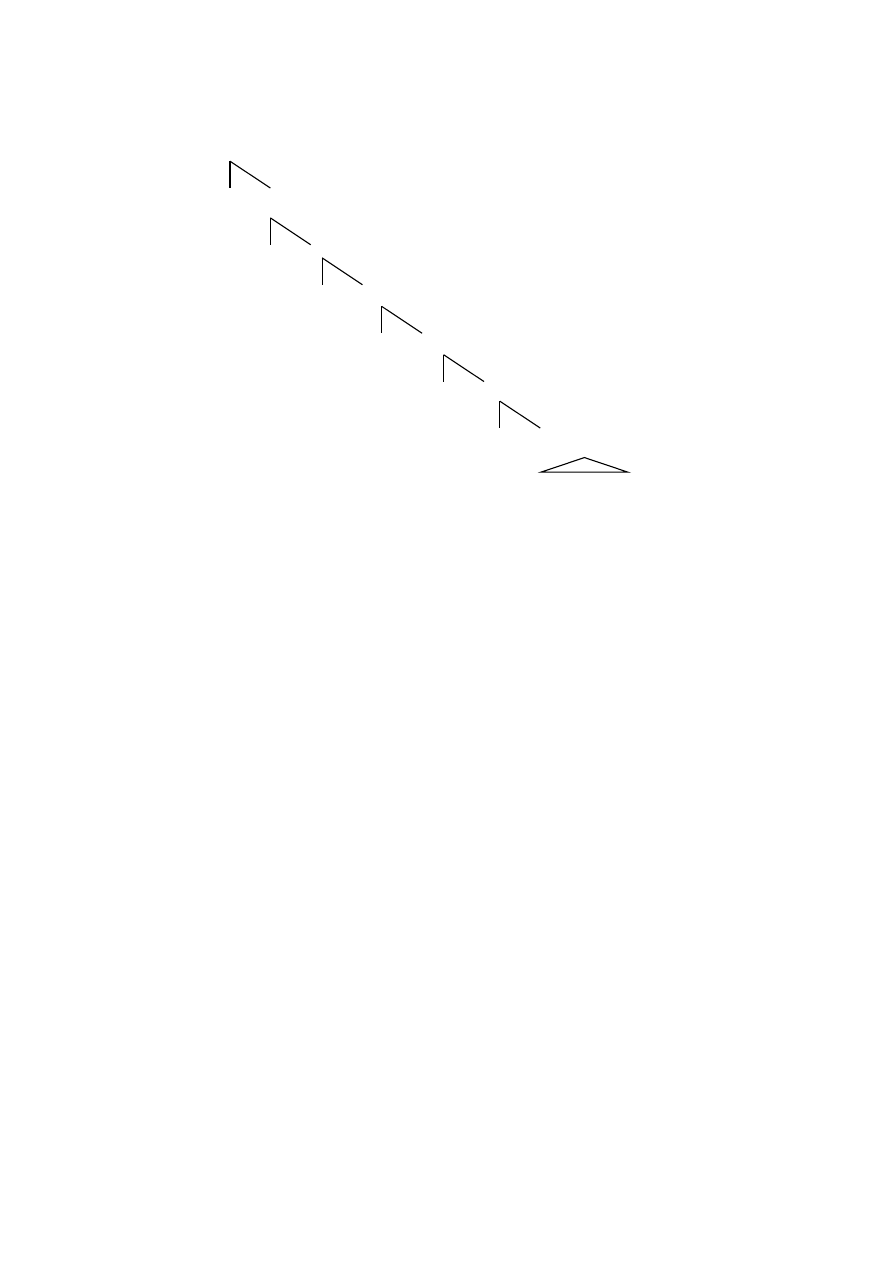

On balance, the structure of DP that I will adopt for the subsequent part of my

analysis of the nominal constructions is the structure consisting of all the projections

mentioned in this chapter and arranged in the following order of appearance:

(30)

DP> PossP> QP> AgrP

1

>…> AgrP

n

> nP> NumP> NP

I assume that the number of AgrPs appearing within the DP is not limited and that it

depends on the actual need, therefore in (30) AgrPs are provided with index numbers.

The index n expresses the theoretical lack of limit on the number of AgrPs within the

DP. The P-maker illustrating the structure is presented in (31) below:

54

(31)DP

D’

D PossP

Poss’

Poss QP

Spec Q’

Q AgrP

Spec Agr’

Agr nP

Spec n’

n

0

NumP

Spec Num’

Num NP

The Focus Phrase discussed in section 2.4 (cf. (21 f)) is not included within the

structure presented in (31). This is motivated by the fact that the presence of this

projection is necessary only in case of emphatic preposing which I will not discuss. The

lack of FocP does not disturb the order of projections, and it will not influence the

analysis that follows.

55

Conclusion

In Chapter 2, I have presented the structure of the DP has been presented, following the

recent analyses available in the literature. One by one, the functional projections

appearing within the nominal phrases: Possessor Phrase, Quantifier Phrase, Agreement

Phrases hosting Adjectives, little n and Number Phrase have been overviewed. Their

place within the nominal structure has been discussed and the reasons for postulating

the existence of each of them have been highlighted.

The Possessor Phrase is the first projection appearing bellow the DP, it hosts the

possessors. The PossP cannot appear in the same position as Saxon genitives - this is a

restriction steming from the UTAH. The second in the order of appearance is the

projection of Quantifiers. According to the theory of the Genitive of Quantification, the

QP is placed within the DP, even though it used to be claimed to be nominal-external.

Following the QP are the Agreement Phrases hosting Adjectives, whose order is

restricted and must follow the universal hierarchy. The number of possible AgrPs within

the DP is not restricted and depends on the need.

Below the AgrP complex, there appears the double layer of nominal shells: nP

and NP. The existence of nP has been proclaimed on the basis of the following three

assumptions:

4. the structure of nominal phrases should be as close to the structure of Verbal

phrases as possible.

5. the requirements of case checking within the nominal expression (especially

the locality condition not satisfied if Agent is claimed to Merge straight in

[Spec;DP] position)

56

6. the UTAH - the requirement linking specific theta-roles to particular

positions in initial syntactic structure.

The lowest projection within the DP is the NP - the projection of a lexical head -

a Noun, which can take complements, as has been assumed from the very beginning of

the research into the structure of nominal phrases.

57

Chapter 3

The DP in Polish

Introduction

Polish is a member of the group of languages which demonstrate no overt instantiation

of the functional element D. Therefore, it is not unexpectable to come across an analysis

of nominal phrases in Polish which assumes that there is no DP projection in this

language. However, the case of Polish is not an isolated one. The same feature may be

observed, among many others, in Chinese, Japanese and in other languages belonging to

the Slavic family. On the theoretical level of research pertaining to this topic, two major

ways of reasoning can be seen:

1. One presenting nominal phrases in languages mentioned strictly as NPs

without the DP layer, and therefore, explaining the syntactic difference

between languages with and without Determiners (Fukui (1986), Zlatić

(1997), Chierchia (1998), Willim (2000), Kim (2004), Bošković (2003,

2004, 2005, 2008) among others);

2. One adopting the idea of functional projection appearing above the NP

without an element, which could appear under D, at the same time being in

favour of universality of the syntactic structure (Corver (1992), Longobardi

(1994), Progovac (1998), Yadroff (1999), Migdalski (2000), Sio (2006),

Perltsvaig (2007), Rutkowski (2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2002c, 2007a, 2007b,

2009) among others).

In this chapter I will present both approaches to the DP, although, I am in

favour of the analysis positing the existence of DP in Polish. I will start by outlining the

58

arguments both for and against the NP interpretation of nominals (section 3.1). Later, I

will move towards the second interpretation, focusing mostly on the argumentation and

analysis as presented by Rutkowski (2007b) in his PhD dissertation. Finally, in section

I will concentrate on the structure, with the use of which Polish nominal phrases could

be described.

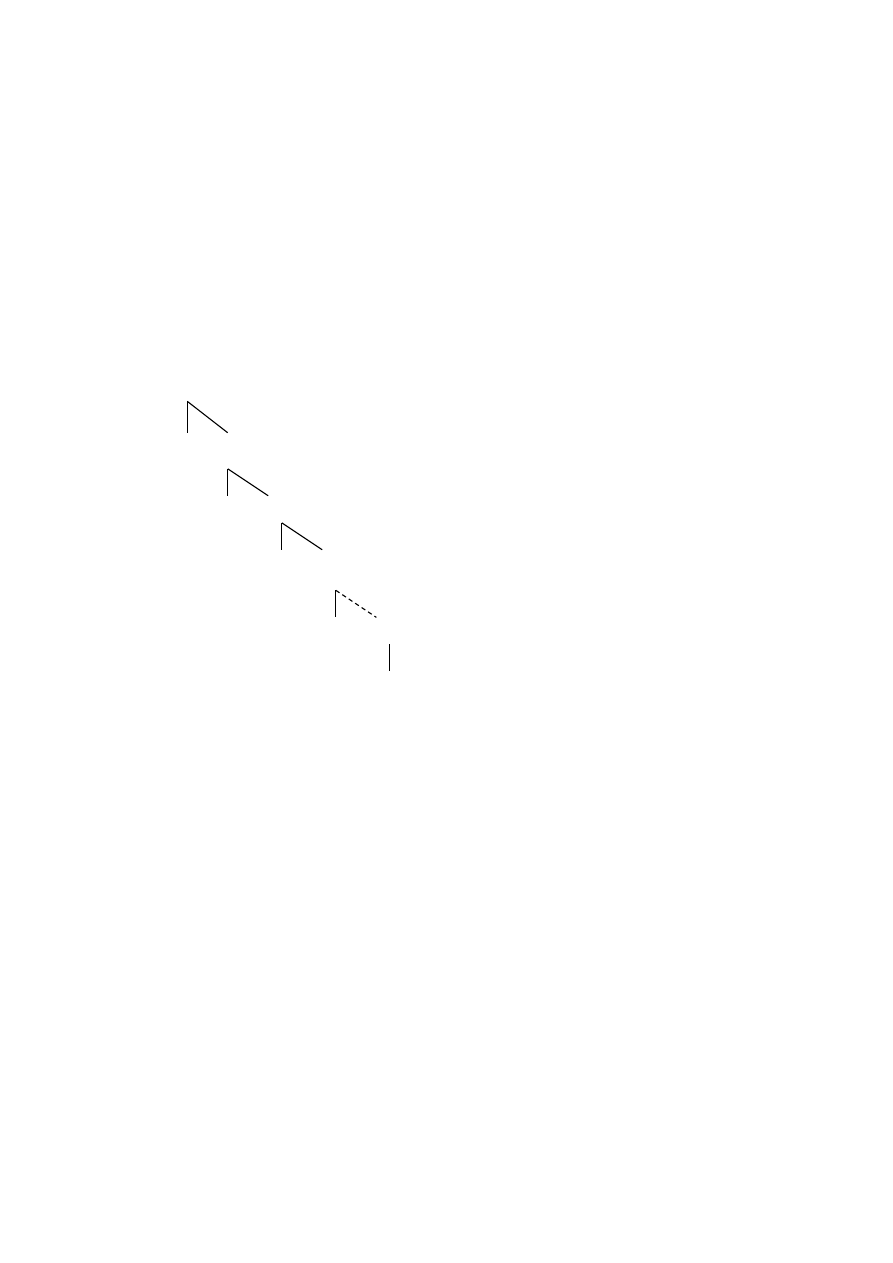

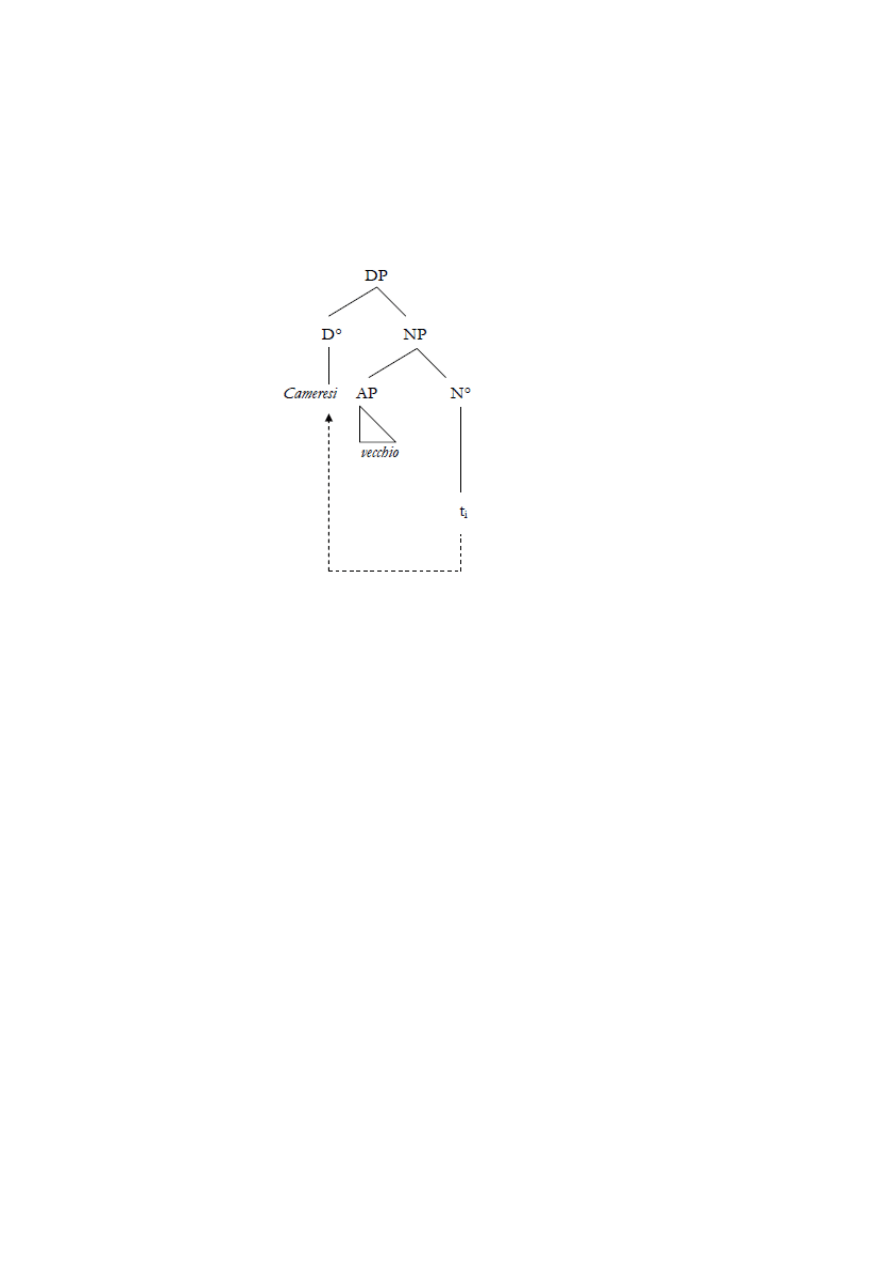

3.1 Is there a DP in Polish?

The existence of languages having in their lexicon no element that could function as an

article is not infrequently the major argument against proclaiming Abney’s DP

Hypothesis as universal (cf., for instance, Fukui (1986)). This observation makes

nominals be treated as they are understood under classical GB analysis – as NPs.

Consequently, the element D is still placed under the [Spec; NP] position and adjectives

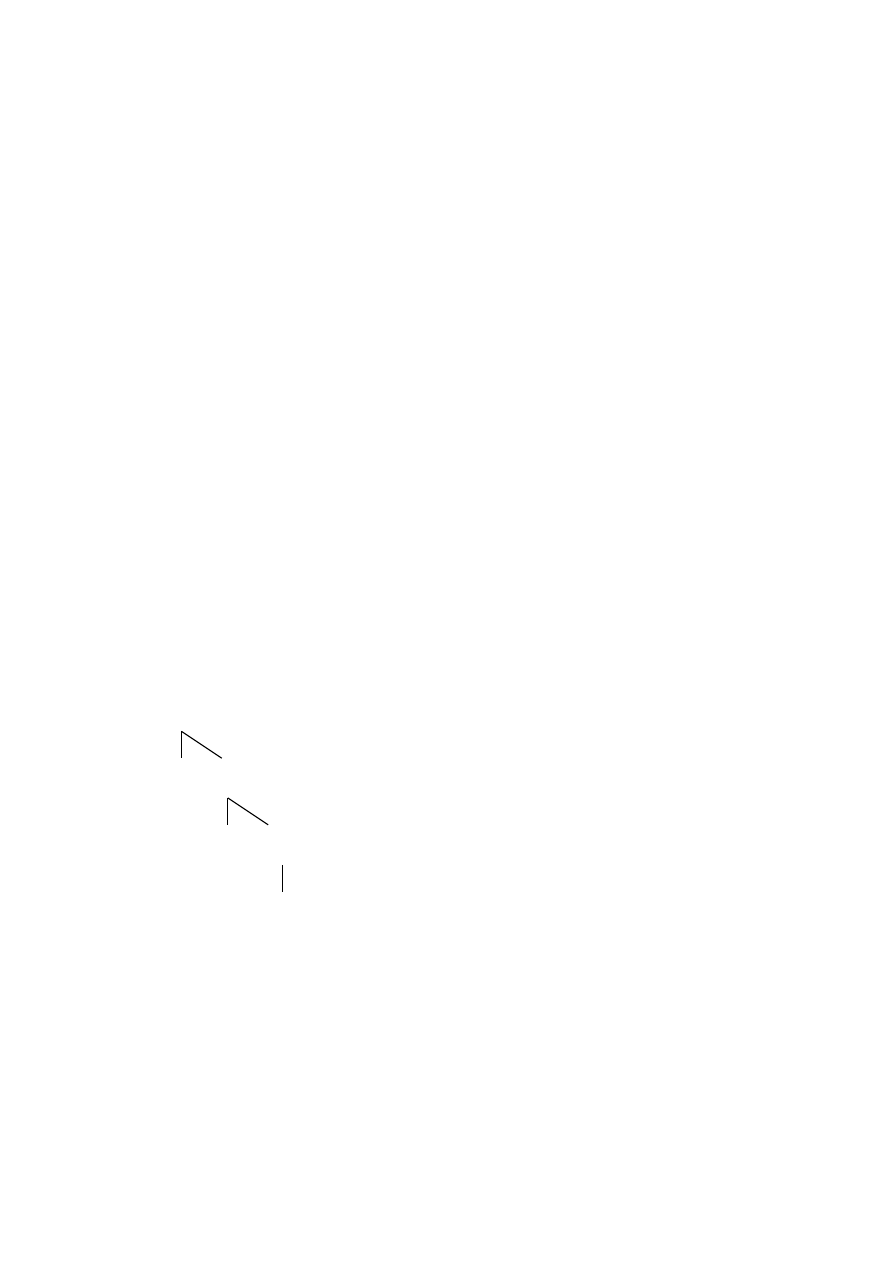

are treated as adjuncts. The structure is shown in the P-maker in (1) below:

(1) NP

D

N’

AP N’

N

The same structure is applicable to Polish. It is supposed to explain phenomena

such as the Left Branch Extraction (LBE) or the impossibility of a nominal construction

59

with the double genitive (Bošković (2005, 2008)). Both phenomena are discussed in

detail in the following subsections of this chapter.

3.1.1 Left Branch Extraction (LBF)

The Left Branch Extraction is a key argument against applying the DP Hypothesis to

languages without a lexical instantiation of the functional Determiner. Bošković (2005,

2008) illustrates this on the basis of examples from Serbo-Croatian and Latin, shown

below:

(2) Serbo-Croatian:

a. Cijegi si vidio [t

i

oca]?

whose AUX-2

nd

sing. seen father

‘Whose father did you see?’

b. Tai je vidio [t

i

kola].

that AUX-3

rd

sing. seen car

‘That car, he saw.’

c. Lijepei je vidio [t

i

kuce].

beautiful AUX-3

rd

sing. seen houses

‘Beautiful houses, he saw.’

d. Kolikoi je zaradila [t

i

novca]?

how-much AUX-3

rd

sing. earned money

‘How much money did she earn?’

(3) Latin:

a. Cuiami amat Cicero [t

i

puellam]?

whose loves Cicero girl

‘Whose girl does Cicero love?’

b. Qualesi Cicero amat [t

i

puellas]?

what-kind-of Cicero loves girls

‘What kind of girls does Cicero love?’

(Bošković (2005: 2-3))

60

As can be seen in the examples above, pre-nominal modifiers in Serbo-Croatian

and in Latin can be extracted from within the nominal group. Their landing site is the

initial position on the left-hand side of the sentence (Bošković (2005)). The LBE is

characteristic for articleless languages only and, in languages like English, it is simply

ungrammatical (Uriagereka (1988), Bošković (2005, 2008)). According to Bošković

(2005, 2008), the difference between the two groups of languages lies in the fact that

languages with articles have a DP projection, whereas articleless languages have only

an NP projection - the traditional NP. What is more, they differ in the position of

Adjectives. In DP-languages, as suggested by Abney (1987) (cf. Chapter 1, section 1.3),

Adjectives are heads of a functional projection appearing between a DP and an NP,

therefore, they alone do not form a full constituent and cannot be extracted – as being a

full constituent is a condition for extraction. In non-DP-languages, on the other hand,

Adjectives are adjuncts, therefore they form constituents and are prone to extraction

(Bošković (2005)). The graphical representation of nominal phrases and the LBE in