Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, 439–459 (1998)

NETWORKS IN TRANSITION: HOW INDUSTRY

EVENTS (RE)SHAPE INTERFIRM RELATIONSHIPS

RAVINDRANATH MADHAVAN

1

, BALAJI R. KOKA

2

and JOHN E.

PRESCOTT

2

*

1

College of Commerce and Business Administration, University of Illinois at

Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, Illinois, U.S.A.,

2

Katz Graduate School of Busi-

ness, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

Interfirm relationship networks are strategic resources that can potentially be shaped by

managerial action. As a first step towards understanding how managers can shape networks,

we develop a framework which explains how industry networks evolve over time and in response

to specific events. Our main thesis is that industry events may be either structure-reinforcing

or structure-loosening, and that their potential structural impact may be predicted in advance.

We validate our hypotheses with longitudinal data on the strategic alliance network in the

global steel industry.

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Strat. Mgmt. J. Vol. 19, 439–459 (1998)

INTRODUCTION

Interfirm

relationships,

especially

strategic

alliances between industry players, represent sig-

nificant flows of knowledge and other resources

that are crucial to industry leadership. This insight

has been the basis for a robust stream of research

in organization theory and strategic management,

beginning with Pfeffer’s (1972) contributions and

continuing to the present day. Interfirm relation-

ships not only help to manage competitive uncer-

tainty and resource interdependency (Pfeffer and

Salancik, 1978), but also serve as conduits for

information and control benefits (Burt, 1992).

Since they are the channels by which goods and

services are accessed, interfirm relationships can

be considered to be resources in their own right

(Freeman and Barley, 1990). While these factors

have been relatively well-understood in the con-

text of dyadic interfirm relationships (i.e., when

relationships are taken one at a time), researchers

Key words:

interfirm relationship networks; industry

events; structural change

*Correspondence to: John E. Prescott, Katz Graduate School

of Business, University of Pittsburgh, 246 Mervis Hall, Pitts-

burgh, PA 15260, U.S.A.

CCC 0143–2095/98/050439–21$17.50

Received 16 January 1996; Revised 3 September 1996

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Final revision received 16 May 1997

in strategic management have recently begun to

acknowledge that multiple dyadic relationships

interconnect

and

bind

firms

into

networks

(Nohria, 1992). The strategic conduct of firms in

an industry is influenced not only by the proper-

ties of their relationships taken one at a time, but

also by the overall structure of interfirm relation-

ship networks (cf. Wellman, 1988). Network ana-

lysts such as Burt (1992) have employed this

logic to argue that well-structured networks are

the basis of superior returns in a variety of

settings, and form valuable ‘social capital.’ Thus,

interfirm relationship networks can be viewed as

strategic resources that play a significant role in

strategic performance. This reasoning is implicit

in recent research that employs the network per-

spective to explore questions of strategy (e.g.,

Nohria and Garcia-Pont, 1991; Shan, Walker, and

Kogut, 1994).

Despite the recent interest in the strategic

implications of interfirm networks, there remains

a need for better theories of ‘how networks

evolve and change over time’ (Nohria, 1992: 15).

The tradition in network analysis has been to

view networks as given contexts for action, rather

than

as

being

subject

to

deliberate

design

(Laumann, Galaskiewicz, and Marsden, 1978;

440

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

Nohria, 1992), perhaps a necessary corollary of

the assumption that social structure endures over

time (Barnes and Harary, 1983; Schott, 1991).

However, current network research has begun to

direct attention at what underlies different net-

work structures (e.g., Cook, 1987; White, 1992).

In line with this research thrust, we take the

position that managerial action can potentially

shape networks so as to provide a favorable

context for future action. In order to understand

how managers may do this, research needs to

move beyond asking how networks constrain and

shape action, to examining what factors constrain

and shape networks. This paper seeks to address

the consequent need for an evolutionary perspec-

tive on interfirm networks. Specifically, we draw

upon the structural perspective (Wellman, 1988)

to theorize about how and why interfirm networks

change over time. We argue that interfirm net-

works evolve in response to key industry events

that may be either structure-reinforcing or struc-

ture-loosening. Further, based on the properties

of each event, it may be possible to identify

an event, in advance, as potentially structure-

reinforcing

or

potentially

structure-loosening.

Identifying the potential impact of an event in this

way alerts managers to the evolutionary nature of

their industry networks, and provides guidelines

for strategic maneuvering. We validate our frame-

work using longitudinal data on interfirm relation-

ships (strategic alliances initiated between 1977

and 1993) in the global steel industry.

NETWORKS IN TRANSITION

The structure of an industry network plays an

important role both in firm performance and in

industry evolution. Since external relationships

provide access to key resources, the structure of

relationship networks describes the asymmetric

access that rivals have to raw materials, infor-

mation, technology, markets, or other crucial per-

formance requirements. Consequently, network

structure provides the context for competitive

action, and structural properties such as network

centrality (e.g., Galaskiewicz, 1979) or autonomy

(Burt, 1992) have been proposed as being corre-

lates of strategic performance. Analogously, it

may be argued that network structure also influ-

ences industry evolution. By directing and limit-

ing access to key resources, the network structure

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

enhances or constrains the ability of specific firms

to shape industry developments. A firm that is

an isolate (i.e., disconnected from the industry’s

network) may find itself without significant input

into,

or

timely

information

about,

crucial

decisions affecting the industry’s future. For

example, Apple Computer Inc. is increasingly

finding itself in this position (Wall Street Journal,

12 December 1995).

Because network structure is a key influence

on performance and industry evolution, managers

engage in strategic maneuvering to secure key

positions in their industry’s network, such as

entering into strategic alliances in order to ensure

access to key technologies or other resources.

Thus, periods of strategic change in the history

of an industry are often marked by observable

flurries of interfirm activity. For example, given

the current state of flux and potential strategic

change in the telecommunications industry, a

number of interfirm relationships have been

announced over the last few years (e.g, Elec-

tronics Times, 17 June 1993; Wall Street Journal,

16 November and 29 November 1995). Similarly,

in the biotechnology industry 246 alliances were

announced in one year (Wall Street Journal, 21

November 1995). Though industry networks can

often be observed to be in a state of flux, the

current literature provides little guidance on what

types of network changes to expect consequent

to major industry events. As previously noted,

network analysts usually assume that social struc-

ture endures over time (Schott, 1991; Barnes

and Harary, 1983), although there are significant

exceptions (e.g., Doreian, 1986; Burt, 1988; Bur-

khardt and Brass, 1990). While this is often a

necessary assumption that facilitates investigation

of how structure influences action, turning it into

an

empirical

question

(i.e.,

does

structure

endure?) can lead to valuable insights. This is

especially true if, as we argue, interfirm networks

are strategic resources that managers design and

develop over time in order to meet their objec-

tives. Accordingly, we propose that the structure

of interfirm relationship networks changes in

potentially predictable ways over time and in

response to specific industry events. A dynamic

perspective on interfirm networks will demon-

strate that networks change over time as the

network participants take advantage of opportuni-

ties to improve their individual positions in the

network. A network at a given point in time is

Networks in Transition

441

a ‘snapshot’ that shows interactions as they cur-

rently exist. The crucial question then becomes:

How will the pattern of relationships change if

the firms were to get the interaction they ‘want’?

(Schott, 1991).

This was the motivation behind the current

investigation of how industry networks evolve

over time and in response to industry events.

Understanding how industry events shape net-

works has actionable managerial implications,

including: (1) articulating what network changes

to expect when specific types of industry events

take place; and (2) determining how to use the

anticipated network changes to a specific firm’s

advantage. Thus, we felt that efforts to develop

a theory of structural change in networks would

be a valuable addition to the strategy literature.

However, the broad claim that network struc-

tures change over time does not hold much theo-

retical interest in itself. On the other hand, the

nature of such change, the ‘occasions’ in which

it takes place, and the direction of the change

are topics worthy of serious investigation, and

form the focus of this paper. We characterize the

nature of structural change in terms of centrality,

centralization,

and

interblock

relations.

The

‘occasions’ of structural change are characterized

in terms of the properties of specific industry

events that set off the change. The direction of

structural change is characterized as being either

structure-reinforcing or structure-loosening. These

three

facets

(i.e.,

nature,

‘occasions,’

and

direction) jointly describe the process of struc-

tural change in interfirm networks.

THE PROCESS OF STRUCTURAL

CHANGE IN NETWORKS

Before defining the nature, ‘occasions,’ and direc-

tion of structural change in networks, we must

first indicate what does not constitute structural

change. First, since network structure is viewed

as the relatively enduring pattern of relationships,

it does not change merely because some actors

leave a network position and some others enter

it. This is consistent with the focus of network

analysis on identifying structural patterns that go

beyond the specific actors that may occupy a

network position at any given point in time.

Second, the network structure does not change in

a fundamental sense merely because the rate of

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

network activity increases or decreases. For

example, if actors that were previously in contact

were merely to increase their interaction with

each other, while not initiating any new contacts

with others or different types of contacts with

current partners, the pattern of relationships does

not change. In contrast, true structural change

would be evidenced by significant variation over

time in the underlying pattern of relationships

that bind a given set of actors. This was the logic

employed in defining the nature, ‘occasions,’ and

direction of structural change in industry net-

works.

Nature of structural change

While an array of techniques have been recently

proposed to characterize the nature of structural

change (Burt, 1992; Sanil, Banks, and Carley,

1995), we chose to focus on changes in network

centrality and interblock relations, for the follow-

ing reasons (cf. Doreian, 1986; Snijders, 1990).

As far as centrality was concerned, our interest

in understanding how networks are strategic

resources dictated that we begin by focusing on

the bases of partner attractiveness. This was on

the reasoning that one cannot design and build an

efficient–effective network (Burt, 1992) without

being able to attract the right partners. The causal

force behind centrality resides in the direct and

indirect ‘demand’ for relations with an individual

actor (Burt, 1991). This suggested to us that we

should begin by analyzing structural change in

terms of what made firms in an industry more

or less ‘in demand’ as partners over time.

With respect to interblock relations, we rea-

soned that structural change should be manifest

in changing relations between groups of firms, as

well as between individual firms. In the strategy

literature, the group level of analysis has always

been significant, (e.g., strategic groups) and we

felt that structural change should be investigated

at this level as well. In network terms, firms can

be divided into blocks, with each block being

composed of firms that are structurally similar,

and relations among blocks can be analyzed (e.g.,

Nohria and Garcia-Pont, 1991). Thus, our dis-

cussion characterizes structural change in terms

of the relative centrality of participating firms

and in patterns of relationships between blocks

of firms.

442

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

Centrality and centralization

The network notion of centrality reflects the sig-

nificance of a firm in its network. At the simplest

level of conceptualization, a highly central firm

is likely to be connected to many more partners

than the less central firm. Centrality comes from

being the object of relations from other contacts

(Burt, 1991). In the network literature, centrality

has been empirically linked to effects such as

power

(Krackhardt,

1990),

reputation

(Galaskiewicz, 1979), and the early adoption of

innovation

(Rogers,

1971).

Being

a

well-

connected and significant player in a network can

be a crucial strategic advantage. Each contact

is a potential conduit for relevant information,

resources, or influence. As Galaskiewicz (1979)

noted, an organization’s power is determined less

by its internal resources than by the set of

resources it can mobilize through its contacts.

The more such contacts the firm has, the better

it is ‘plugged in’ to the key task and influence

processes of the industry, and the stronger is its

strategic advantage. Thus, the relative centrality

of firms is an important factor for the network

analyst interested in describing structural change

in networks. Firms that realize the value of cen-

trality may constantly be attempting to improve

their centrality by connecting with more and more

central partners. In the process, they may abandon

relationships with partners who are perceived as

being less valuable, reducing the latter’s cen-

trality. Since firm centrality is evidently such a

key resource, we argue that changes in the rela-

tive centrality of firms are important indicators

of structural change. If a given set of firms

retains, over the years, their relative levels of

centrality, there is no indication of a structural

change in the network. On the other hand, a

network undergoing true change would be charac-

terized by either an increase or a decrease in the

firms’ levels of centrality. Attempting a centrality-

based assessment of structural change is consis-

tent with our focus, as strategic management

researchers, on the firm-level implications of such

change. Thus, we argue that before-and-after mea-

sures of centrality can be used to assess structural

change at the firm level. At least one prior inves-

tigation of network evolution (Doreian, 1986) has

used changes in actor centrality as a means to

estimate structural change in networks.

Centrality is a firm-level construct, but the

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

distribution of centrality among firms in a net-

work gives rise to the construct of centralization,

which indexes the tendency of a single firm to

be more central than all others in the network

(Freeman, 1979). In a highly centralized network,

for example, there will be a few very central

firms and many peripheral firms. On the other

hand, a network with many firms at relatively

similar levels of centrality is less centralized.

Thus, centralization provides an aggregate meas-

ure for the distribution of centrality among firms

in a network. Analogous to centrality, before-

and-after measures of centralization can be used

to assess structural change at the network level

(Doreian, 1986).

Interblock relations

In analyzing centrality and centralization, we are

mainly concerned with understanding the patterns

of relationships established by individual firms

with other firms. A complementary concern for

intergroup relations will allow us to explicate

general types of relations maintained by groups

of firms (Scott, 1991). For purposes of analysis,

firms may be divided into blocks in one of three

ways, using the respective criteria of structural

equivalence (e.g., Lorrain and White, 1971), gen-

eral equivalence (e.g., Burt, 1976), and contextual

equivalence (e.g., Freeman and Barley, 1990).

While the criteria of structural equivalence and

general equivalence are based on patterns of

relationships between firms, that of contextual

equivalence

is

based

on

attribute

similarity

between firms (e.g., Barley, 1988). We chose the

criterion of contextual equivalence as it allowed

us to capture change in patterns of relationship

between strategically meaningful categories of

firms. Each block in our analysis consists of firms

that are similar on the attribute of technology.

There are two advantages to using the criterion

of contextual equivalence. First, it is consistent

with the concern of strategic management with

performance

and

other

differences

between

‘groups’ of firms, as evidenced by the wealth of

research on strategic groups (McGee and Thomas,

1986). Second, contextually equivalent blocks

allow us to keep the block membership constant

and thus to observe how relations within and

between those blocks change over time. The

underlying logic was that changes in relationship

patterns within and between blocks are an

Networks in Transition

443

important indicator of structural change. For

example, Nohria and Garcia-Pont (1991) analyzed

strategic alliance activity in the world automobile

industry in terms of relationships between stra-

tegic groups. A longitudinal treatment of similar

data would bring out shifts in the pattern of

relationships between groups with differing capa-

bilities, in conjunction with changes in the com-

petitive dynamics as a key indicator of struc-

tural change.

‘Occasions’ for structural change

In defining the ‘occasions’ that trigger structural

change, we adopted an event focus. Recent work

in organizational research has underlined the

value of a theory of how organizational phenom-

ena are structured (Barley, 1986). A promising

line of reasoning suggested by this work is to

investigate specific events as ‘occasions for struc-

turing’ (Barley, 1986). For example, based on

his study of how new technologies such as medi-

cal imaging help to recreate role structures among

radiologists and radiological technologists, Barley

(1986: 80) proposed that major restructuring only

occurs

when

organizations

face

‘exogenous

shock.’ In a network context, Burkhardt and Brass

(1990) investigated how the organizational power

structure changes in response to a change in

technology. Their study showed that early adop-

ters of a new technology increased their power

and centrality to a greater degree than did later

adopters (Burkhardt and Brass, 1990).

An event focus tracks the evolution of an

industry network over time by examining struc-

ture through various ‘windows’ of time (e.g.,

Doreian, 1986). The length of any ‘window’

depends on specific events. A key advantage of

this approach is that researchers and managers

are equally likely to agree that industry events

provide more relevant ‘check points’ for network

evolution than arbitrary time periods. An anal-

ogous logic may be found in the use of a

‘decision focus’ for case study research in organi-

zations (e.g., Allison, 1971). In the absence of

an event focus, the choice of an appropriate

‘window’ length becomes a thorny problem. As

Doreian (1986) suggests, we need a time-specific

theory rather than one which merely states that

network processes are located in time. Adopting

an event focus provides an elegant solution to

this problem: the timing of industry events allows

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

for a setting in which the length of ‘windows’ is

automatically determined for the researcher.

Building on this reasoning, we propose that

key industry events provide occasions for network

restructuring. The events of interest are specific

occurrences

that

knowledgeable

observers

acknowledge as impacting competition on an

industry-wide basis and in the long run. Illus-

trations include major technological develop-

ments, the entry of a resourceful and determined

competitor, changes in regulatory infrastructure,

or dramatic shifts in consumer preferences.

As we argued earlier, network position deter-

mines access to key resources, such as infor-

mation or the potential for control (Burt, 1992),

and network structure is a crucial influence on

firm performance and industry evolution (cf.

Pfeffer, 1981). Specific industry events provide

opportunities for firms to attempt to improve their

positions in their industry network. Some industry

events, such as fundamental regulatory reform or

radical technological change, potentially change

the basis of competition in an industry. This will

have an observable impact on the network of

relations within the industry. Firms may find that

they need access to a different set of resources

than provided by their current partners. They

may then be prompted to initiate a new set of

relationships with a different set of partners. Thus,

some industry events will be followed by substan-

tial change in the industry’s network structure.

While all technology shocks need not result in

fundamental industry reorientation (Tushman and

Anderson, 1986), there is ample evidence that

some technology events reshape industries. For

example, Piore and Sabel (1984) argued that

changes in production technology underlie shifts

in the way economic activity is organized. Simi-

larly, Glasmeier (1991) documented the radical

impact that technology changes wrought on the

production networks of Swiss watchmakers. On

the other hand, all industry events may not result

in such drastic change. There may be some types

of changes that help to reinforce the current

strategic trajectory of the industry (e.g., by

removing barriers to the achievement of current

industry goals). Such an event could increase the

value of the firm’s current set of relationships,

and actually serve to strengthen them.

444

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

Direction of structural change

The third facet of structural change revolves

around the question: What types of network

changes are likely to follow key industry events?

Our main thesis is that the structural impact of

industry

events

may

be

either

structure-

reinforcing or structure-loosening. We view the

structure of a network as being reinforced if, in

general, hitherto powerful firms increase their

network power while hitherto less powerful firms

become even less powerful. In other words, the

network structure is reinforced if the existing

distribution of network power is strengthened,

benefitting the network ‘rich’ at the expense of

the network ‘poor.’ On the other hand, the struc-

ture of a network is loosened if hitherto powerful

firms decrease their network power while hitherto

less powerful firms become more powerful than

they were. To continue the ‘rich–poor’ analogy,

the network structure is loosened if network

power is redistributed, benefitting the network

‘poor’ at the expense of the network ‘rich.’ Thus,

the direction of structural change hinges on

whether the existing distribution of network

power is reinforced or loosened.

Accordingly, we now proceed to develop the

framework to arrive at a strategically meaningful

conceptualization of when to expect what kind

of structural change in industry networks. Our

thesis is that the characteristics of the ‘occasion’

for structural change may be used as a basis for

predicting the direction of such change. Armed

with this knowledge, managers may take appro-

priate steps in order to protect and enhance their

network positions and associated ‘social capital.’

The answers to three questions help to determine

whether

an

event

is

potentially

structure-

reinforcing or structure-loosening (See Table 1):

(1) How does the event affect the currently

Table 1.

Characteristics of events affecting network structure

Characteristics of events

Structure–reinforcing event

Structure-loosening event

Effect on the bases of competition

Enhances and strengthens existing

Radically changes the bases of

bases of competition

competition

Who benefits?

Dominant players with high cen-

Peripheral players with low cen-

trality in current network

trality in current network

Who initiates?

Dominant players in current net-

Peripheral players in current net-

work

work

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

accepted bases of competition in the industry?

(2) Who does the event potentially benefit?

(3) Who initiated the event? Structure-reinforcing

events serve to strengthen the current structure

of the network, because they typically sustain,

rather than disrupt, current industry trajectories.

Structure-reinforcing events mainly benefit those

players who are already in key positions in the

network, and are likely to be initiated by those

same dominant players. In contrast, structure-

loosening events trigger change in existing pat-

terns of relationships, as they are more likely to

be disruptive of accepted practices and industry

definitions. Structure-loosening events tend to

benefit peripheral players who use the event to

improve their positions, and are less likely to be

initiated by dominant industry players. Based on

the characteristics of each event, it may be pos-

sible to predict whether it will reinforce or loosen

the current structure. Such prediction will be

crucial in determining the nature of structural

impact to expect after key industry events, and

what moves to make in response.

Our framework thus characterizes the process

of network evolution in terms of the nature,

‘occasions’ and direction of structural change.

The nature of structural change is characterized

in terms of shifts in centrality, centralization,

and relationships between contextually equivalent

technology

blocks.

‘Occasions’

of

structural

change are characterized in terms of key industry

events that provide opportunities for network

restructuring. The direction of structural change

is

characterized

as

being

either

structure-

reinforcing or structure-loosening. These three

aspects of structural change are the building

blocks for a description of the overall process of

structural change and provide the framework for

developing our hypotheses.

Networks in Transition

445

PROPERTIES AND HYPOTHESIZED

EFFECTS OF STRUCTURE-

REINFORCING EVENTS

Structure-reinforcing events will have the follow-

ing three properties:

1. They build upon and extend currently accepted

bases of competition in the industry. For

example, Tushman and Anderson (1986) have

argued that incremental technological improve-

ments enhance and extend the underlying tech-

nology, thus reinforcing the existing order.

Bower and Christensen (1995) have put for-

ward the notion of performance trajectories,

which is useful here. The performance tra-

jectory of a product class is defined by the

rate at which the performance of a product

has improved, and is expected to improve,

over time (Bower and Christensen, 1995: 45).

A structure-reinforcing event will typically

help to sustain the performance trajectory of

a

product

class—for

example,

thin

film

components in computer disk drives replaced

conventional ferrite heads and oxide disks,

enabling data to be recorded more densely. A

regulatory event that removes strategic barriers

that previously existed would be another type

of structure-reinforcing event. For example,

under current laws, the regional telephone util-

ities are seriously constrained in their inter-

national investments. A change in this regula-

tory

framework

would

increase

the

international activity of such firms, without

introducing radical change in the underlying

competitive logic of their industry. In contrast,

the proposed changes that would allow tele-

phone and cable utilities to compete with each

other would probably introduce radical change

in the basis of competition (e.g., telephone

utilities would have to make decisions on what

types of programming to carry). From a cogni-

tive perspective, structure-reinforcing events

would not result in any substantial change in

the managerial recipes (Spender, 1980) in an

industry.

Thus,

structure-reinforcing

events

will typically extend and strengthen a current

competitive regime.

2. Firms that are already in powerful network

positions will benefit more from such events

than more peripheral firms. There are two

reasons why this is the case. First, the domi-

nant firms in the industry are likely to be the

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

ones that are also in powerful network posi-

tions. Since the event reinforces the current

competitive paradigm, the dominant firms are

likely to become even more dominant, becom-

ing more desirable partners in the process.

Second, their powerful position in the network

allows them a better opportunity to capitalize

on the event than the more peripheral firms.

The causal force behind this advantage is pro-

vided by the information and control benefits

(Burt, 1992) of their network positions.

3. They are more likely to be initiated by firms

that are currently dominant. Given that a struc-

ture-reinforcing event is likely to benefit them

more than their weaker counterparts, dominant

players are more likely to initiate such events.

A variety of reasons combine to make this

so. In the field of technology, for example,

incremental progress occurs through the inter-

action of many firms, unlike initial break-

throughs (Tushman and Anderson, 1986).

Since the central players in the network are,

by definition, placed at the center of such

interaction, they are likely to be the source of

such improvements. Similarly, events such as

a regulatory initiative that removes strategic

barriers have to be coordinated and orches-

trated through a lobbying process—again, a

task that dominant firms are likely to be more

effective at (e.g., New York Times, 29 Nov-

ember 1994). In interpersonal networks, Burk-

hardt and Brass (1990) found that if early

adopters are more central than late adopters

before a technological event, the existing pat-

tern of relationships is likely to be strength-

ened. Finally, Bower and Christensen (1995)

have put forward the argument that established

companies tend to concentrate on technologies

that sustain their current performance trajector-

ies because those technologies serve their cur-

rent customer base better. Thus, the established

and dominant firms are less likely to initiate

radical and disruptive change (Henderson and

Clark, 1990).

Hypothesized effects

Centrality

Structure-reinforcing events provide highly central

firms with an opportunity to increase their cen-

trality. Since their desirability as partners is now

446

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

higher, they will be able to attract more partners.

At the same time, the peripheral players will now

find it even more difficult to attract partners.

Thus, highly central firms are in the best position

to benefit from a structure-reinforcing event, and

we would expect them to remain central after the

event. Similarly, peripheral players will remain

peripheral. In sum, any structural change would

be an increase in centrality for the already central

firms and increasing marginalization of peripheral

firms. Thus, we would expect a significant and

positive correlation between centrality indicators

before and after the structure-reinforcing event.

Accordingly:

Hypothesis 1a:

The centrality of individual

firms before a structure-reinforcing event will

be significantly and positively correlated with

their centrality after the event.

Centralization

The results at the level of the overall network

will be analogous. Since hitherto central firms

will increase their centrality, and hitherto periph-

eral firms will remain marginalized, a structure-

reinforcing event will increase the overall cen-

tralization of the network. Thus:

Hypothesis 1b:

A structure-reinforcing event

will have the effect of increasing the centrali-

zation of the network.

Interblock relations

The causal forces outlined above would also

imply that a structure-reinforcing event would

benefit groups of firms which are hitherto in

attractive positions. Since the fundamentals of

competition do not shift, the pattern of relation-

ships between the blocks should be reinforced

over time. In other words, the bases of partner

attractiveness and the bonds between blocks of

firms will remain, or indeed, strengthen. We

expect to observe an increasing set of relation-

ships among those blocks that potentially benefit

from the structure-reinforcing event.

Explicit hypothesis testing regarding the sta-

bility or change in the pattern of interblock

relations is hampered by the lack of appropriate

methodological and statistical tools (Snijders,

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

1990). Thus our approach is grounded in a set

of procedures (described in the Results section)

which allow us to draw conclusions regarding the

role of a structure-reinforcing event on the pattern

of interblock relations.

PROPERTIES AND HYPOTHESIZED

EFFECTS OF STRUCTURE-

LOOSENING EVENTS

We use a reverse logic to articulate the properties

and effects of structure-loosening events. Struc-

ture-loosening events will have the following

three properties:

1. They radically change the basis of competition

in the industry. One of the best examples is

provided by what Tushman and Anderson

(1986) have labeled ‘competence-destroying

discontinuity.’ Such discontinuities mark a rad-

ical shift in technological paradigms, and tend

to obsolete the skills and knowledge base pre-

viously required. Nontechnology events can

be structure-loosening, too. For example, the

proposed regulatory move to dismantle the

natural monopolies given to telephone and

cable utilities is widely expected to change

the competitive dynamics of the telecommuni-

cation industry. In network terms, structure-

loosening events imply that firms may need

to look for a sharply different set of partners

who will provide them with a new set of

resources.

2. Firms that are already in powerful network

positions have no automatic benefit from such

an event. The more peripheral firms are equa-

lly likely to benefit. Previously powerful firms

may be constrained in their ability to quickly

find new partners, largely because of prior

commitments to existing partners. On the other

hand, the relatively peripheral firms may have

greater leeway. Further, the previously domi-

nant firms may have difficulty adopting the

new paradigm (Henderson and Clark, 1990),

making them less desirable partners under the

new competitive regime. These factors serve

to dampen whatever information and control

benefits prior network centrality may have

offered.

3. They are more likely to be initiated by firms

that

are

currently

peripheral.

The

initial

impetus, such as the adoption of a radical new

Networks in Transition

447

technology or a fundamentally new pricing

strategy, is more likely to come from smaller

players acting alone rather than from the inter-

actions of highly central firms (Henderson and

Clark, 1990). The peripheral players also have

the motivation to introduce structure-loosening

events, as they can only gain—unlike the cur-

rently central players, who stand to lose their

dominance. By the same token, the currently

dominant players are unlikely to initiate struc-

ture-loosening events that can radically rede-

fine the competitive dynamics of the industry.

For example, consider IBM’s bitter and long-

lived opposition to the UNIX operating system

during the 1980s.

Hypothesized effects

Reversing the logic of the previous set of hypoth-

eses, we argue as follows.

Centrality

The structure-loosening event will reduce the

benefit of previous centrality. Since hitherto

highly central firms are no longer in the best

position to benefit from the event, we would

expect them to become less central. Peripheral

players, on the other hand, may use the oppor-

tunity to improve their position, and increase their

centrality. Thus, it may appear that the centrality

of individual firms before a structure-loosening

event will be negatively correlated with their

centrality after the event. However, this is an

extreme characterization of structure-loosening,

representing a case ‘in the limit.’ In reality, we

expect some countervailing forces, because there

are several reasons why prior centrality could be

‘sticky’ even after a structure-loosening event.

First, existing contacts may help to mitigate the

negative impact of the structure-loosening event,

even for those firms whose current competencies

are made less valuable. With the help of those

contacts, these firms may succeed in salvaging

the situation and remain more or less dominant—

at least for the time being. This is one more

powerful reason why networks should be viewed

as a strategic resource: they shield the firm from

being buffeted by industry shocks, and increase

the possibility of immediate survival (Stopford

and

Baden-Fuller,

1990).

Second,

structure-

loosening events need not benefit all peripheral

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

firms—many previously peripheral firms may

remain peripheral even after the event. Some

previously peripheral firms that were well-posi-

tioned to benefit from a particular structure-

loosening event may increase their centrality (e.g.,

those who possess a competency that has now

become

valuable).

Because

of

these

countervailing movements, the net correlation will

not be negative. What we expect, instead, is that

the correlation between before-and-after centrali-

ties will be considerably less in the case of

structure-loosening events than in the case of

structure-reinforcing events. Thus:

Hypothesis

2a:

The

correlation

between

before-and-after centralities

will be signifi-

cantly less for a structure-loosening event than

it will be for a structure-reinforcing event.

Centralization

Structure-loosening events provide less central

firms with an opportunity to increase their cen-

trality. Since their desirability as partners is now

higher than it was earlier, they will be able to

attract more partners. At the same time, the hith-

erto central players will now find it more difficult

to attract partners, as their competencies may be

less valuable under the new competitive regime.

This will have the effect of temporarily decreas-

ing the overall centralization of the network.

1

Eventually, the network may revert to a highly

centralized state, with a new set of firms being

in highly central positions. However, during the

transition phase, the gap between the hitherto

central firms (whose centrality now decreases)

and the hitherto peripheral firms (whose centrality

now increases) is likely to decrease. Thus:

Hypothesis 2b:

A structure-loosening event

will have the effect of temporarily reducing

the centralization of the network.

Interblock relations

The causal forces outlined above would imply

that a structure-loosening event would signifi-

cantly change the established pattern of relations

between blocks of firms. The shift in competitive

1

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for pointing out

that the decrease in centralization may be temporary.

448

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

regime undermines the current bases of partner

attractiveness, potentially leading to a ‘shuffling’

period which will rearrange the bonds between

blocks of firms. During this period of ‘shuffling,’

blocks which previously had little reason to inter-

act may need to draw on each other’s resource

bases to succeed in the new competitive order.

Conversely,

blocks

which

have

established

relationships may find them to be less important

for the emerging competitive environment. We

expect to observe an increasing set of relation-

ships involving blocks who are likely to be the

beneficiaries of the structure-loosening event. At

the same time, we expect to observe fewer inter-

actions among hitherto connected blocks.

METHODS AND DATA

We tested our hypotheses by analyzing and inter-

preting changes in the structure of the strategic

alliance network in the global steel industry

between 1977 and 1993. The steel industry is an

appropriate context for the study both because it

has witnessed significant strategic changes over

the last few decades (e.g., Abe and Suzuki, 1991)

and because interfirm relationships have been an

acknowledged influence on the industry’s evolu-

tion (e.g., Knoedler, 1993). The strategic alliance

network is an appropriate network to focus on

because (1) strategic alliances represent relation-

ships between rivals, which are acknowledged

sources of influence on industry evolution (Porter,

1980); (2) they represent flows of knowledge

and access to markets, which have been key

success factors in the industry (Grant et al.,

forthcoming); and (3) there has been a significant

amount of strategic alliance activity in the global

steel industry (Madhavan and Prescott, 1995).

Choice of industry events

Two key industry events, the regulatory shock of

1984 and the technology shock of 1987, are used

as the anchor points for our analysis. In 1984,

several regulatory decisions (the Cooperative

Research Act, the approval of the National-NKK

venture) in the United States signaled a lowering

of the traditional institutional barriers to coopera-

tive strategy. In the same year, the Voluntary

Restraints Agreement, by limiting the amount

of steel foreign producers could export into the

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

American market, also provided some impetus to

the cooperative production of steel in the United

States—e.g., production joint ventures between

Japanese and U.S. steel producers. The 1987

technological event was the decision by Nucor to

adopt the Compact Strip Production technology

for its Crawfordsville, Indiana plant, which had

two major implications: (1) a potential threat to

the integrated players who had a monopoly of

the high-margin sheet steel market; and (2) an

acceptance of the Compact Strip Production tech-

nology as the apparent winner over other technol-

ogies such as the Hazelett process. The literature

on the steel industry suggests that these two

events are widely perceived as being turning

points in the history of the industry (e.g., Wall

Street Journal, 16 February 1984; Ghemawat,

1993; Hogan, 1991).

We reasoned that the particular regulatory

event that took place in 1984 has the character-

istics of a structure-reinforcing event. First, it did

not change the basis of competition in the steel

industry. Rather, what it did was to remove bar-

riers to cooperative activity, while leaving in

place the relative strengths of industry players

(e.g., Wall Street Journal, 16 February 1984).

Second, the already central players were in the

best position to benefit from the event, as they

could use their contacts to find new partners

or to strengthen existing relationships. Third, as

regulatory events are often the result of the lobby-

ing efforts of powerful industry actors (e.g., New

York Times, 29 November 1994), it is quite likely

that this event was initiated by dominant players.

One likely scenario is that this regulatory event

was driven by the need for U.S. and Japanese

integrated steel producers to join together in order

to service the steel needs of Japanese transplant

automobile manufacturers in the United States.

On the other hand, the particular technology event

that took place in 1987 has the characteristics of

a structure-loosening event. First, it acted as a

competence-destroying

discontinuity

(Tushman

and Anderson, 1986) for the central players (the

integrateds), and radically changed the basis of

competition in the industry. The primary impact

was that it potentially opened up the attractive

sheet steel market (hitherto the preserve of the

integrateds) to competition from the minimills

(Ghemawat, 1993). The introduction of the com-

pact

strip

production

process

substantially

changed the operating economics of the steel

Networks in Transition

449

industry, representing a 10–15 percent drop in

production

cost

and,

more

significantly,

a

reduction in capital cost from $1000 per ton of

capacity to $300 a ton (Christensen and Rosen-

bloom, 1991). Second, the prior centrality of the

integrated manufacturers did not give them any

advantage in exploiting the new technology.

Further, with the emergence of a viable new

technology, the hitherto central integrateds were

no longer as attractive (as potential partners) as

they used to be. Third, the technology event was

initiated by Nucor, a hitherto (very) peripheral

firm in the network. (For an additional reason to

believe that the 1987 event was a structure-

loosening event, see the Results section, wherein

we discuss the impact of the events on the num-

bers of strategic alliances initiated.)

Data

Since the focus of our study was the evolution of

networks, we were primarily interested in alliance

relationships within the industry. We accordingly

adopted

a

relationship

criteria

(Laumann,

Marsden, and Prensky, 1983) to define the bound-

aries for our study. Only those firms in the steel

industry that formed at least one strategic alliance

and their partners were included in the study.

The data on strategic alliances in the global steel

industry were obtained from the Dow Jones News

Retrieval Service. These data covered the period

1977–93, and related to all types of strategic

alliances, including joint ventures, joint programs,

licensing arrangements, and long-term supply

relationships. In all, 130 firms participated in the

network, comprising 41 integrated steel firms, 10

minimills, and 9 specialty steel producers, 20

upstream partners (e.g., a coal mining company),

26 downstream partners (e.g., an automobile

manufacturer) and 24 firms from other industries.

In terms of nationality, there were 66 American

firms, 11 Canadian firms, 19 Japanese/Korean

firms, 25 European firms and 9 firms from other

parts of the world. In terms of production output,

30 of the top 50 steel firms in the world partici-

pated in alliance activity and they accounted for

75 percent of the top 50 output in 1990.

Adapting the approach suggested by Contractor

and Lorange (1988) and used by Nohria and

Garcia-Pont (1991), each alliance was assigned a

numerical score indicating its ‘intensity’ on a

continuous 9-point scale. A score of 1 on the

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

scale indicated an alliance of low intensity

(technical training), while a score of 9 indicated

an alliance of high intensity (greenfield joint

venture). Thus, the score for each alliance proxies

the strength, or ‘intensity,’ of the relationship,

thereby indicating the potential for resource flow

(cf. Krackhardt, 1992). If a pair of partners had

more than one alliance, the scores for all alliances

were added to form a composite index. As an

additional validity check, we also conducted other

supplementary analyses, the results of which are

detailed in the Results section.

In order to facilitate analysis of changes

‘around’ each event, the data were captured in

the form of a series of 130

×

130 matrices

depicting the relationship between each potential

pair of partners. Since strategic alliances are bidi-

rectional by definition, these matrices were sym-

metric. The first matrix, Structure-Reinforcing at

time period one (SR1), consisted of all alliances

announced in 1977–83, i.e., before the regulatory

event of 1984—a structure-reinforcing event. The

second

matrix,

Structure-Reinforcing

at

time

period two (SR2), consisted of all alliances

announced in 1984–93, i.e., after the regulatory

event. Comparing these two networks would

enable us to draw some conclusions about the

effect of the structure-reinforcing event. A similar

‘cut’ was made to bring out the effect of the

technology event of 1987—a structure-loosening

event. The third matrix, Structure-Loosening at

time period one (SL1), consisted of all alliances

announced in 1977–86, i.e., before the technology

event of 1987. The fourth matrix, Structure Loos-

ening at time period 2 (SL2), consisted of all

alliances announced in 1987–93, i.e. after the

technology event. The effect of the structure-

loosening event would be assessed by comparing

these two networks.

It must be noted here that our method of

creating separate matrices using pre- and post-

event alliances parallels the ‘sliding window’

approach advocated by Doreian (1986), rather

than the use of an ‘expanding window.’ The

major advantage of such an approach is that it

helps to purge the resultant matrices of historical

components. By ensuring that the post-event

matrix contains only new alliances initiated after

the

event,

the

‘sliding

window’

approach

‘decumulates’ the network, and is thus able to

better

capture

structural

change

(Doreian,

1986:61).

450

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

The approach adopted resulted in matrices

which have an overlapping time coverage across

SR1 and SL1, as well as between SR2 and SL2,

which was unavoidable since we were investigat-

ing the effect of two events in the same industry.

The comparisons and statistical tests, however,

were

between

the

nonoverlapping

pairs

of

SR1/SR2 and SL1/SL2. We did investigate a

three-period analysis, comparing and contrasting

the structure in 1977–83, 1984–86, and 1987–

93. However, the short ‘window’ and sparseness

of the second network (1984–86) were causes

for serious concern. In this context, Doreian

(1986: 62) has pointed out that short ‘windows’

are undesirable because of higher ratios of noise

to structural information. Accordingly, we chose

the two-period analysis.

Operationalization of network measures

From among the various measures of centrality

available (e.g., Freeman, 1979), we chose the

flow betweenness measure, as it best reflects the

idea of centrality emerging from the ability to

benefit

from

and

control

the

flow

of

resources/information in the network (Freeman,

Borgatti, and White, 1991). The measure assesses

the amount of flow (m

jk

) between firm j and

firm k that must pass through firm i. The flow

betweenness of firm i is the sum of all m

jk

where

i, j and k are distinctive and is given by:

Centrality (Firm i)

=

冘冘

m

jk

(i)

The flow betweenness measure is therefore a

measure of the contribution of firm i to all pos-

sible maximum flows and depends on the number

and intensity of alliances of firm i. This was

consistent with the way we coded each alliance

for its capacity for resource flow.

Centralization is operationalized as the average

difference between the centrality of the most

central firm and that of all other firms. For a

given network, network centralization is given by:

Centralization of Network

=

冘

C

max

−

C(firm i)

n

−

1

where C

max

is the centrality measure of the most

central firm and n is the number of firms in

the network.

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

We operationalized blocks in terms of the tech-

nology of the firms. Technology was selected as

the attribute for creating contextual equivalent

groups for three reasons. First, the technological

basis (integrated, minimill, specialty) of a firm

significantly affects its cost structure, product

offerings, and customer groups. Second, tradition-

ally there has been a limited degree of compe-

tition in the product–markets between the tech-

nology

groups.

In

recent

years,

however,

competition between integrated and minimills has

intensified. Third, international competition has

been significantly influenced by the implemen-

tation of new-generation technologies since the

end of World War II. Given this set of factors,

changes in the pattern of relationships between

technology blocks should provide insights into

the process of network transition. The 130 firms

were thus divided into six technology blocks—

integrated steel firms, minimills, specialty steel

firms, upstream, downstream, and others—and

we investigated how relations between them had

changed after each event.

Analysis

The above four 130

×

130 matrices were used as

the input to UCINET IV, a widely used network

analysis program. UCINET IV was used to ana-

lyze firm centrality (Hypotheses 1a and 2a) and

overall centralization (Hypotheses 1b and 2b) in

each network. The approach we took for explor-

ing interblock differences was block-model analy-

sis. UCINET IV allows the ‘collapsing’ of firms

into blocks and the mapping of relationships

within and between these blocks. In order to

increase the validity of our conclusions, relations

between or within blocks were considered to exist

if the density was at least equal to or greater

than the overall network density (Gerlach, 1992).

Network density is measured as the total value

of all ties divided by the number of possible ties,

and signifies the ‘average’ level of relationship

in the network. By taking only those relationships

that are equal to or greater than network density,

we consider only those interblock relationships

that are stronger than the ‘normal’ relationship

level in the network. Relations between the blocks

were then examined before and after each event

in an effort to describe and interpret how the

pattern of relations had changed.

Networks in Transition

451

RESULTS

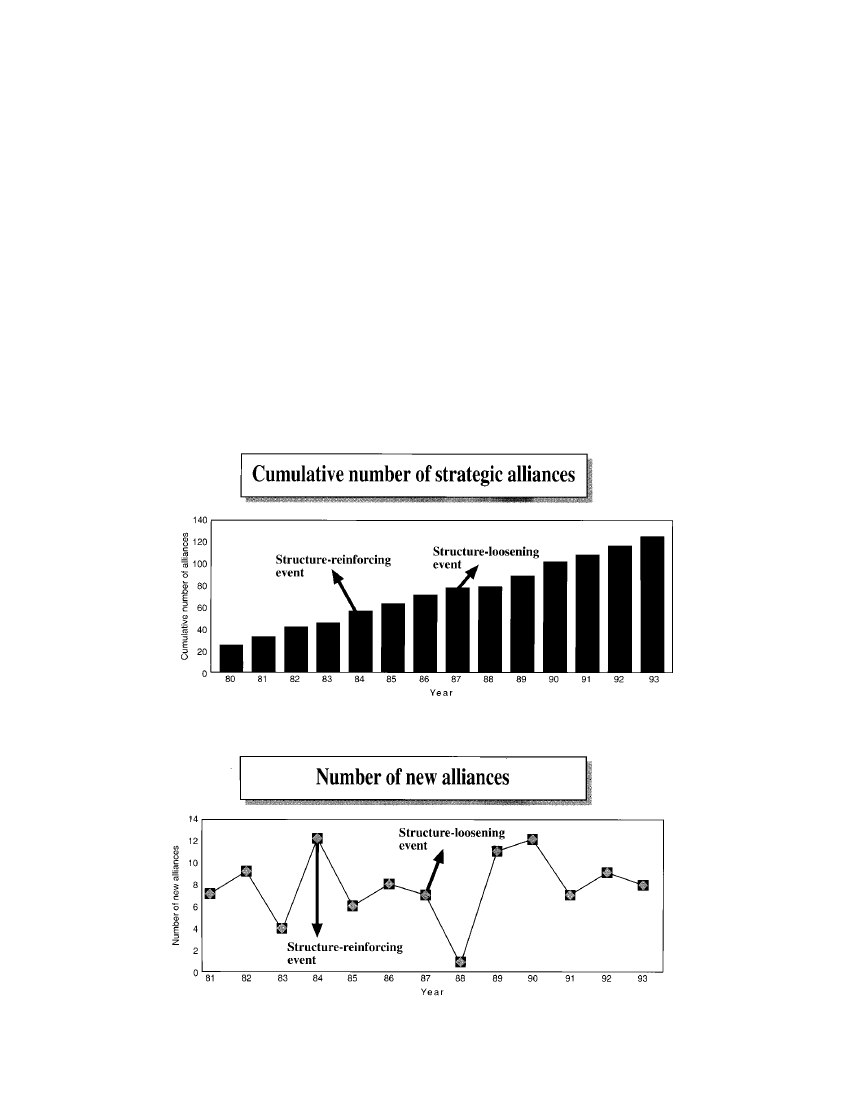

The accompanying charts in Figure 1 present the

number of alliances in the global steel industry

between 1980 and 1993 (the period 1977–80 has

been collapsed into 1980 for ease of depiction).

The data show a steady increase in the cumulative

number of announced strategic alliances. On ana-

lyzing the number of new alliances announced in

any year, however, we find an interesting pattern.

There was a sharp rise in the number of new

alliances

in

1984,

i.e.,

after

the

structure-

reinforcing event. Immediately after the structure-

loosening event of 1987, there was sharp drop in

the number of new alliances, though alliance

activity picked up in subsequent years. We inter-

pret this drop as confirmation that the 1987 event

was a structure-loosening event: steel industry

Figure 1.

Strategic alliances in the global steel industry, 1980–93

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

firms would have taken time to analyze the devel-

opment and assess its implications, as it was

potentially a competence-destroying discontinuity

(Tushman and Anderson, 1986).

Overall, 130 strategic alliances were reported

during 1977–93. Of these, 8 percent were techni-

cal training agreements; 10 percent were patent

licensing

agreements;

3

percent

were

production/buy-back agreements; 3 percent were

‘know-how’ licensing agreements; 1 percent were

service agreements; 6 percent were nonequity

alliances; 5 percent were joint ventures in existing

operations; and 64 percent were greenfield joint

ventures.

Table 2 presents the results of the centralization

and centrality analyses. First, we found that there

was a significant correlation of 0.58 (p

⬍ 0.001)

between firm centralities before and after the

452

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

Table 2.

Tests of hypotheses

Hypothesis

Network measures

Tests of significance

Interpretation

1. Hypothesis 1a

Correlation between actor centralities

before and after SR event: 0.58

p

⬍ 0.001

Strongly supported

2. Hypothesis 1b

Centralization before SR event

a

: 30.33%

Centralization after SR event: 64.23%

Difference between the two measures:*

z

=

5.47

Strongly supported

(p

⬍ 0.001)

3. Hypothesis 2a

Correlation between actor centralities

before and after SR event: 0.58

Correlation between actor centralities

before and after SL event: 0.38

Difference

between

the

two

corre-

lations:**

z

=

1.73

Supported

(p

⬍ 0.05)

4. Hypothesis 2b

Centralization before SL event

b

: 52.55%

Centralization after SL event: 44.42%

Difference between the two measures:*

z

=

1.47

Moderately supported

(p

⬍ 0.08)

N

=

130.

a

SR event: structure-reinforcing event.

b

SL event: structure-loosening event.

*Test for difference between proportions (single-tailed test); **Test for difference between independent correlations (single-

tailed test).

structure-reinforcing event, confirming Hypothesis

1a. Next, we found that network centralization

increased from 30.33 percent to 64.23 percent

(p

⬍ 0.001) after the structure-reinforcing event,

thereby providing support for Hypothesis 1b.

Thus, the data strongly support the expected

effects of a structure-reinforcing event.

The effect of the structure-loosening event was

also as expected. We found that there was a

correlation of 0.38 (p

⬍ 0.001) between firm cen-

tralities before and after the structure-loosening

event, which was considerably less than the corre-

lation for the structure-reinforcing event. The dif-

ference between the two correlations was signifi-

cant at p

⬍ 0.05, thus supporting Hypothesis 2a.

Network centralization decreased from 52.55 per-

cent to 44.42 percent (p

⬍ 0.08) after the struc-

ture-loosening event, thereby providing moderate

support for Hypothesis 2b.

2

2

Our method of coding alliances differentially (on a scale

from 1 to 9) appeared to be the most efficient way to proxy

the overall strength of the relationship between two players,

as it captures, although roughly, the cumulative strength of a

set of alliances. In order to address concerns about the pitfalls

of imputing cardinality, however, we did two supplementary

analyses. First, we ignored the strength of the alliances, and

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

In order to explore the relationships among

the technology blocks, we used an interpretation-

intensive approach. We must note here that both

the composition of the groups, as well as judging

if the patterns of intergroup relations are different,

are both tasks that are heavily dependent on the

industry context of a particular study. The results,

in

our

interpretation,

support

our

position

developed in the hypotheses section (see Figures

2 and 3).

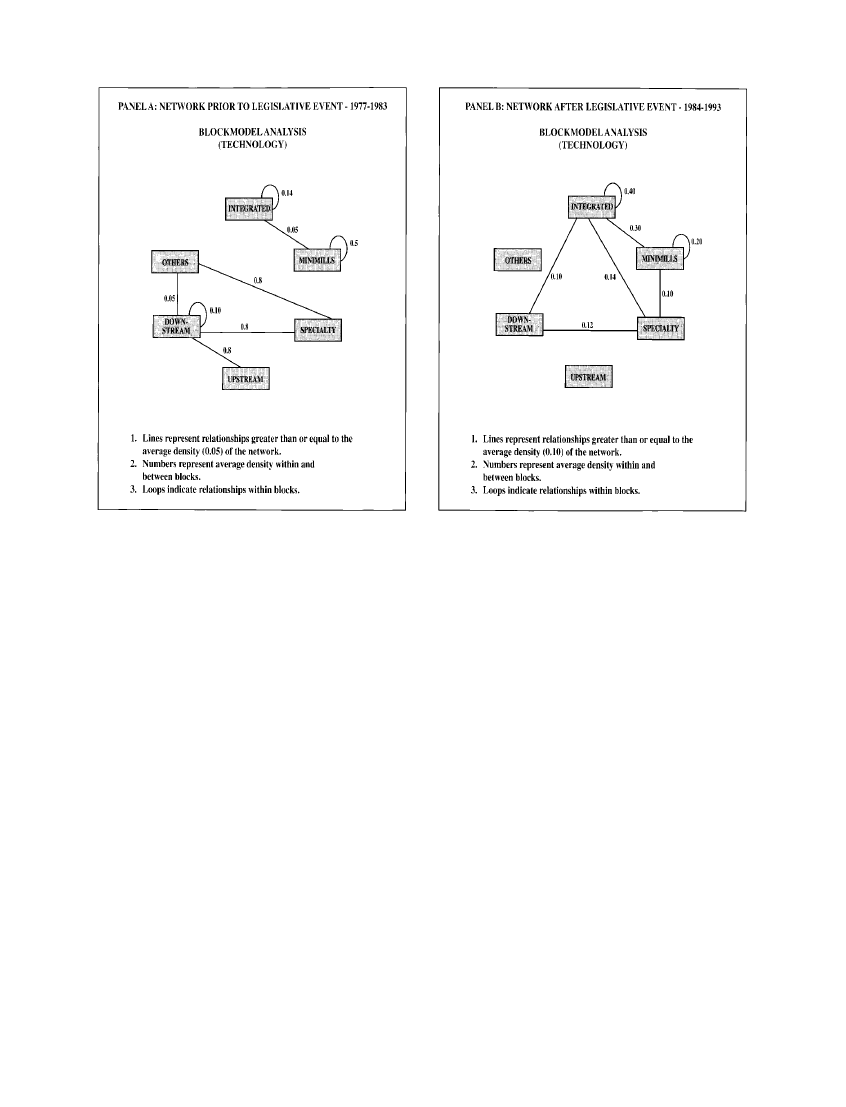

First,

we

examined

how

the

structure-

reinforcing event affected relations between tech-

nology blocks (Figure 2). As noted earlier, only

those relationship arcs that are greater than the

average network density are considered. The

change in the number and the strength of these

expressed the relationship between each pair of players simply

in terms of the number of alliances between them. The

corresponding network was then analyzed in the same way

we analyzed the earlier network. As predicted, the correlation

between SR1 and SR2 centralities (0.66) was higher than that

between SL1 and SL2 (0.45). Second, we constructed a

subnetwork consisting only of greenfield joint ventures and

reran the analysis. Again, as predicted, the correlation between

SR1 and SR2 centralities (0.25) was higher than that between

SL1 and SL2 (0.21), though by a narrower margin.

Networks in Transition

453

Figure 2.

Global steel industry networks: Effect of a structure-reinforcing event on technology blocks

arcs is used to judge if the pattern of relations

between and within blocks is different (Snijders,

1990). The analysis of technology blocks shows

that there were eight arcs before the event, and

seven arcs afterwards. Four of the earlier eight

arcs were dropped and three new ones were

added. The structure-reinforcing event appears to

have resulted in the strengthening of the positions

of the integrated and speciality steel players

(Figure 2). Prior to the event, integrated players

were only connected to each other and to mini-

mills. After the event, the integrated players have

relationships with minimills (much stronger now),

speciality producers, and downstream players, as

well as with each other. Specialty producers have

also established new relationships with minimills

and integrateds after the event. This strengthening

of the integrated and specialty producers was to

be expected, as they were the dominant players

before the event.

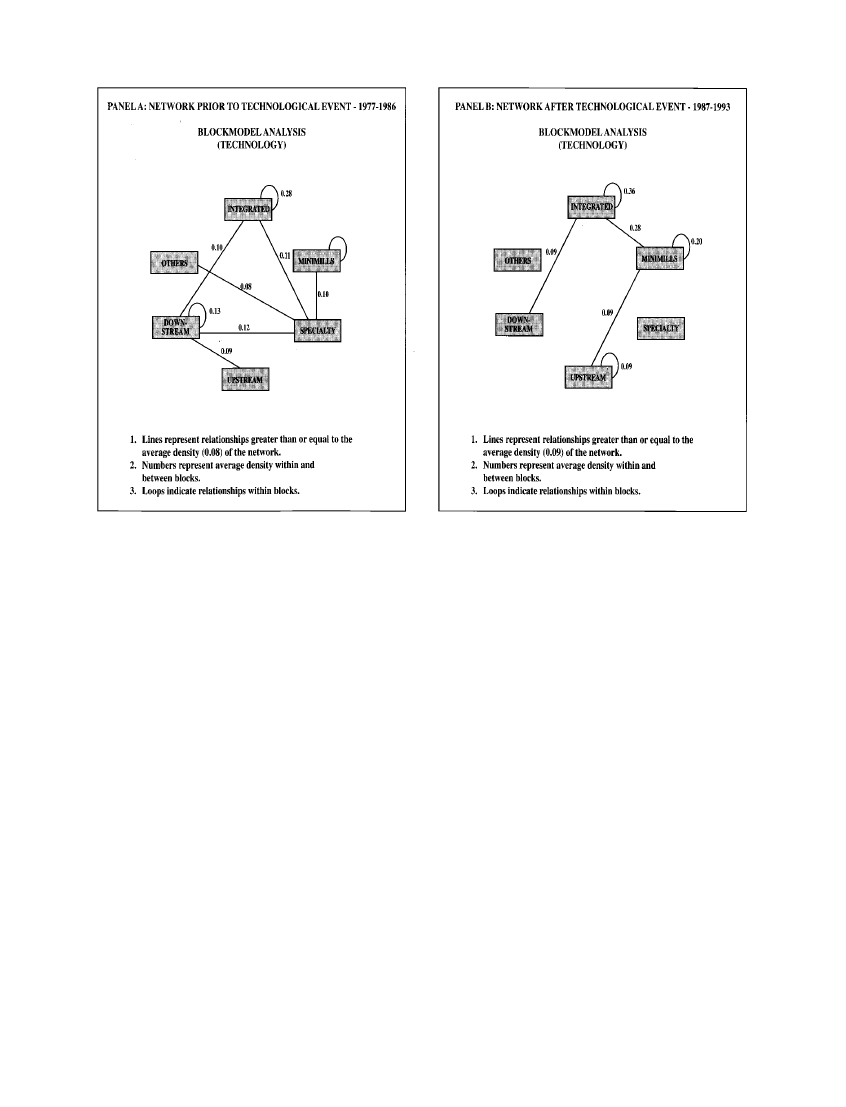

Next, we examined how the structure-loosening

event affected relations between the technology

blocks (Figure 3). The impact of the structure-

loosening event appears to have been somewhat

greater and more radical than the structure-

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

reinforcing event. Six out of eight earlier arcs

were dropped, and four new ones were added.

Visually, it can be seen that the structure-

loosening event has resulted in a substantial reori-

entation of the network from a ‘crow’s nest pat-

tern’ of interlocked blocks to a much more

streamlined network with relatively high cen-

trality for the minimill players (Figure 3). This

redesign was expected, especially for the mini-

mills, since the structure-loosening event provided

the ‘occasion’ for less dominant players to

improve their position.

As an additional check on the validity of our

conclusions, we conducted centrality analysis for

the blocks (similar to the analysis conducted ear-

lier at the firm level). For the technology blocks

we found that the centrality correlations before-

and-after

the

structure-reinforcing

event

was

0.757, which was significant at p

⬍ 0.08. As

expected, the centrality correlations before-and-

after the structure-loosening event was 0.647,

which was lower, although not significantly, than

the correlation for the structure-reinforcing event.

In summary, the analysis of technology blocks

shows support for our position. In particular,

454

R. Madhavan, B. R. Koka and J. E. Prescott

Figure 3.

Global steel industry networks: effect of a structure-loosening event on technology blocks

structure-reinforcing events provide conditions

conducive to the established players while struc-

ture-loosening events establish a forum for per-

ipheral players to restructure the network to

their advantage.

DISCUSSION

Our discussion will cover two main topics. First,

we offer our interpretation of the results, and

identify a few limitations. Second, we sketch out

some major implications of our study.

Interpretation of results

On the whole, the results show strong support

for our framework. Three of our hypotheses

(Hypotheses 1a, 1b and 2a) were supported at a

significance level better than 0.05. Hypothesis 2b

was also supported, with results in the hypothe-

sized

direction

and

significant

at

p

⬍ 0.08.

Though appropriate statistical significance tests

are not available, we judged our positions related

to interblock relationships to be supported. Since

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

we hypothesized opposing results for structure-

reinforcing and structure-loosening events, and

found support in both cases, these results suggest

a strong test of our framework. Thus, we con-

clude that the ideas of structure-reinforcing and

structure-loosening events have validity.

An issue worth noting here is the possibility

that the sequencing of change may have an

important effect. In our sample, the structure-

loosening event followed the structure-reinforcing

event. It is quite possible that the firms may have

expended much of their ‘degrees of freedom’ in

responding to the structure-reinforcing event, and

may not have been able to respond very much

to the subsequent event. Barley’s (1986) obser-

vations about the cumulative effect of structuring

are relevant in this context. Because of this path

dependency effect, the net effect of the structure-

loosening event may have been muted. If this is

indeed the case, the sample may have provided

us with a conservative test of our hypotheses,

increasing our confidence in the results.

A related aspect also worth discussion is the

length of time ‘windows’ over which structural

change takes place. In our approach, ‘window’

Networks in Transition

455

length is dictated by the choice of appropriate

event

‘around

which’

structural

change

is

expected to take place. This is consistent with

Doreian’s (1986: 63) advice that we find ‘good

pragmatic reasons’ for selecting a ‘window’

length, given the absence of a ‘theory on the

shelf.’

However, we acknowledge that such a

method does not resolve all issues. For example,

there is the question of how long a structure-

loosening event will have the effect of reducing

centralization—i.e., how long will it be before a

new set of players become highly central, and

the network reverts to a highly centralized state,

if ever? Given the nascency of research into

network evolution, as well as the highly industry-

specific contingencies that might influence the

pace of ‘recentralization,’ there appear to be no

clear answers to such a question at this point.

Another important issue that merits discussion

is whether industry events must necessarily be

followed by network changes of one type or

other. We believe, and our data have demon-

strated, that there are aggregate network changes

that follow key industry events. However, this

does not mean that it is possible to predict how

an industry event will affect the fortunes of every

individual firm in the network. Whether a given

firm is able to improve its position in the network

is dependent on three factors: its ability to attract

desirable partners, its motivation to improve its

position, and whether it has an opportunity to do

so. These factors are consistent with Burt’s

(1992) discussion on the issue of entrepreneurial

motivation and network opportunity. What our

study has shown is that industry events provide

certain firms with the opportunity to improve their

network positions. Firms that are differentially

endowed with the ability or the motivation to

improve their network position will benefit differ-

entially. Clearly, questions of ability and moti-

vation are important (e.g., what constitutes the

ability to improve one’s network position?)—

however, they are beyond the scope of this paper.

Thus, the data on strategic alliances in the

global steel industry show encouraging support

for our main thesis, i.e., that industry events may

be classified as structure-reinforcing and structure-

loosening, and that they impact the subsequent

structure of the network. Our research also shows

that industry events may be identified in advance

as potentially structure-reinforcing or potentially

structure-loosening. This possibility of prediction

has important implications, to be discussed below.

1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Strat. Mgmt J., Vol 19, 439–459 (1998)

Limitations

When interpreting our results, a few cautionary

statements are in order. First, as in most network

studies, our conclusions are based on the experi-

ence of one industry network, i.e., the global

steel industry. In that sense, our study should

perhaps be

viewed

as

ideographic research.

Second, the two events in our study took place

in somewhat close proximity to each other (within

3 years), and some of their effects may have

been intertwined. Third, the effect of the two

events were investigated over relatively short pe-

riods

of

time—9

years

for

the

structure-

reinforcing change and 6 years for the structure-

loosening change—and all the changes may not

have appeared in the network. Finally, it is diffi-

cult to tease out the effect of the path dependency

factor that is ever-present in longitudinal research.

Some of these are limitations that may be

addressed by future work that goes across indus-

tries to investigate the effects of structure-

reinforcing and structure-loosening events.

Implications

As hinted at before, we believe that our results

have significant implications, both for research

and for practice.

Research implications

The increasing popularity of the network perspec-