Nominal aspect, quantity, and time :

The case of the Finnish object

1

T U O M A S H U U M O

University of Tartu

(Received 16 May 2008 ; revised 30 January 2009)

It is well known that the quantity indicated by an NP affects clausal aspect if the

referent of the NP participates in the event incrementally, i.e. in a part-by-part

manner (e.g. She was mowing

THE LAWN

). In general, an incremental NP that indicates

a closed quantity makes the overall aspect of the sentence telic and thus bounded,

whereas one indicating an open quantity results in unbounded aspect (e.g. W

ATER

was

dripping from the ceiling). In this paper the interplay between quantity and aspect will

be called nominal aspect. It is argued that quantity may relate with time in two

different ways : first, as overall quantity (which, if incremental, cumulates over time),

and second, as transient quantity. The latter term refers to the quantity involved in

the situation at a given point in time. It is argued that the interpretation of certain

NPs evokes both kinds of quantity ; e.g. in This machine pumps

THE WASTE WATER OF

THE FACTORY

into the drain the object indicates a quantity that is open in the overall

sense (there is no end to the waste water entering the event of pumping) but closed in

the transient sense (at any point, all [relevant] waste water gets pumped into the

drain). A corresponding distinction is drawn in the domain of verbal aspect, which

can also be bounded or unbounded in two different ways. Overall aspect unfolds over

time and, if telic, ultimately reaches its endpoint, as in She took the letter to the post

office. Transient aspect is the aspectual nature of an event at any given point in time.

It is understood as orthogonal to the time axis and gives a cross-section of the on-

going event. In This brush cleans the conveyor belt before it enters the machinery the

overall aspect (of the ‘ cleaning ’) is unbounded, but the transient aspect is bounded,

assuming that the brush continuously keeps the conveyor belt in a state of total

cleanliness. In this paper, such oppositions are used in explaining the case marking of

the Finnish object (partitive vs. ‘ total object ’ case marking), which reflects both

quantificational and aspectual factors. It is argued that the total object can indicate

a closed quantity and a bounded aspect not only in the overall sense but also in

the transient sense. This distinction is then used to account for many hitherto un-

explained uses of the cases.

1. I

N T R O D U C T I O N

:

N O M I N A L A S P E C T

For decades, verbal aspect, nominal quantity and the interplay between the

two have been popular research topics in linguistics (a thorough survey of

[1] I am grateful to two anonymous JL referees for their invaluable feedback that helped me

improve the quality of this paper significantly. All remaining shortcomings and errors are

of course my responsibility alone. This research was funded by the Estonian Science

Foundation (Grant 7552).

J. Linguistics 46 (2010), 83–125.

f Cambridge University Press 2009

doi:10.1017/S0022226709990223

First published online 17 November 2009

83

the literature is given in Sasse 2002). In particular, formal semantics (for in-

depth studies see e.g. Verkuyl 1972, 1993 ; Krifka 1989) has studied the

interdependence of aspectual and quantificational factors, demonstrating

that aspect must be considered a

COMPOSITIONAL

phenomenon. Many anal-

ogies between the aspectual (verbal) and quantificational (nominal) domains

have been pointed out, and it has been demonstrated in detail how clause-

level aspect depends on the contribution of many clausal elements, not just

the verb. Especially Verkuyl (1972, 1993) has emphasized the significance of

the arguments of the verb for aspect. The situation is perhaps clearest in

transitive clauses in which the object is an incremental theme (see Dowty

1991) and thus participates in the event gradually. For instance, in She was

painting the fence the activity proceeds along the fence gradually and reaches

its endpoint when the whole fence has been painted. The extent of the fence

(its quantity) thus sets boundaries to the duration of the painting, since the

painting can only last as long as there remains fence to be painted. Such

dependence of clausal aspect on nominal quantity will be referred to in the

present paper as

NOMINAL ASPECT

.

Among phenomena related to nominal aspect, the concept of boundedness

is of central importance. As is also well known, the opposition between

bounded and unbounded is common to both verbal aspect and nominal

quantity (see Talmy 2000 : 42–88 for a detailed comparison). In the aspectual

domain, boundedness depends first and foremost on the verb and its inherent

aspectual nature, also known as Aktionsart. At the clausal level, however,

other factors such as aspectual constructions (e.g. the progressive), durative

modifiers (for two hours), and locatives indicating a source or a goal con-

tribute to the aspectual interpretation. In recent literature on aspect, it has

become customary to distinguish two different levels of aspect. Sasse (2002 :

203–204) calls these

ASPECT

1

(viewpoint aspect, including the perfective/im-

perfective dichotomy and its associates, often expressed by grammatical

means) and

ASPECT

2

(the Aktionsart type of aspect, more directly dependent

on the lexical meaning of the verb). Smith (1997 : 3) draws a similar distinction

between

SITUATION TYPES

(Sasse’s

ASPECT

2

) and

VIEWPOINT TYPES

(Sasse’s

ASPECT

1

). She distinguishes five main types of situations :

STATES

(static, durat-

ive, e.g. know),

ACTIVITIES

(dynamic, durative, atelic, e.g. dance),

AC-

COMPLISHMENTS

(dynamic, durative, telic, consisting of a process and its

outcome, e.g. build),

SEMELFACTIVES

(dynamic, atelic, instantaneous, e.g.

sneeze) and

ACHIEVEMENTS

(dynamic, telic, instantaneous, e.g. find). States

and activities are atelic and thus inherently unbounded, i.e. have no natural

end point. Accomplishments, semelfactives and achievements are bounded

situation types : they have an endpoint which they reach either after a gradual

development (accomplishments) or instantaneously (achievements and

semelfactives). A crucial difference between them is telicity : the

COMPLETIVE

types accomplishments and achievements bring about an end result, whereas

semelfactives are atelic. This means that in the completive event types the

T U O M A S H U U M O

84

state that follows the event differs from the state that precedes it, whereas in

semelfactives the two states are (conceptualized as) similar. Smith also dis-

tinguishes three viewpoint aspect types that the speaker may select when

viewing a situation : these are the

PERFECTIVE

viewpoint (viewing a situation

in its entirety, including both initial and final endpoints if such exist), the

IMPERFECTIVE

viewpoint (viewing only part of a situation, including neither

the initial nor the final endpoint) and the

NEUTRAL

viewpoint (flexible,

including the initial endpoint of a situation and at least one internal stage).

A rapidly growing literature has addressed the phenomenon called

ASPECTUAL COERCION

, (informally) the alteration of the aspectual meaning of

a linguistic element (typically a verb) to semantically match its context.

Coercion takes place, for instance, when a telic verb is used in a progressive

construction (for details, see e.g. Pustejovsky & Bouillon 1995, de Swart 1998

and Michaelis 2004). De Swart (1998 : 349) defines aspectual coercion as ‘ an

implicit, contextually governed process of reinterpretation which comes into

play whenever there is a conflict between the aspectual nature of the

eventuality description and the input condition of some aspectual operator ’.

Topics studied under the rubric of coercion within the formal semantics tra-

dition cover phenomena ranging from verbal Aktionsart to nominal quantity.

In the nominal domain, boundedness depends on whether the NP refers to

a closed (bounded) or an open (unbounded) quantity. For clarity, I will

follow Larjavaara (1991) in using the terms

OPEN

vs.

CLOSED

to refer to this

nominal quantificational opposition, and reserve the terms

BOUNDED

and

UNBOUNDED

for verbal aspectual use. In incremental situations, open quantity

gives rise to unbounded aspect and closed quantity to bounded aspect.

Another pair of terms used for this purpose were introduced by Krifka

(1989), who distinguishes

QUANTIZED

(closed/bounded) and

CUMULATIVE

(open/unbounded) expressions in both the aspectual and the quantificational

domains. In the nominal domain, only mass nouns and plural forms are

typically able to indicate both open and closed quantities (of substances and

multiplicities), whereas singular count nouns refer to indivisible entities,

which inherently constitute closed quantities. However, indivisible entities

may also participate in events incrementally, as in The potter was making a

flower pot.

With mass nouns and plurals, the opposition between open and closed

quantities also correlates with definiteness : definite mass nouns and plural

forms generally indicate closed quantities, while indefinite ones indicate open

quantities. For instance, in The flour is in the cup the definite subject NP

refers to a closed quantity of flour, whereas in There is flour in the cup the

quantity of the flour is open (‘ some flour ’). Count nouns, on the other hand,

always indicate a closed quantity, since their referent is conceived as an

indivisible whole. This closedness does not correlate with definiteness, cf. The

strawberry [closed quantity, definite] is in the cup vs. There is a strawberry

[closed quantity, indefinite] in the cup (for such relationships between

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

85

definiteness and quantification, with special reference to English and Finnish,

see Chesterman 1991). However, as is well known, the boundary between

mass and count nouns is fuzzy, and the speaker has the ultimate option of

representing even prototypical count nouns as mass-like, as in the following

example from Langacker (1991 : 73) : After I ran over the cat with our car,

there was cat all over the driveway. According to de Swart (1998 : 352 ; see also

Bach 1986), such examples also involve a coercion, and the literature uses the

notions of a

UNIVERSAL GRINDER

and a

UNIVERSAL PACKAGER

to reflect (re-

spectively) the nature of the operations at work when we use mass nouns in a

count-noun-like fashion, and when we use count nouns as mass-like.

In her cognitive linguistic study of Russian aspect, Janda (2004) makes a

detailed comparison between nominal referents (in her terms, the idealized

cognitive model (ICM) of matter) and verbal aspect. Her general objective is

to explain aspectual phenomena as a metaphor of the ICM of matter. She

draws a basic distinction between discrete solid objects and fluid substances

(basically the count vs. mass distinction), and argues that a similar distinction

can be made in aspect, with perfective aspect corresponding to a solid object

and imperfective aspect to a fluid substance. Crucial features of a discrete

solid object include the fact that it has inherent shape and edges, cannot be

easily penetrated, cannot occupy the same place as another discrete object,

is stable, and can be grasped (Janda 2004 : 475–476). Another feature that

distinguishes solid objects from fluid substances is what Janda calls

‘ streamability ’ : fluid substances can ‘ stream ’ and participate in events

gradually (incrementally), whereas solid objects cannot. What makes Janda’s

work especially fruitful for studies dealing with the interplay of nominal

quantity and aspect is that she not only discusses these domains separately

but also introduces many conceptual operations that are available to the

speaker for manipulating these notions. Such operations may result, for

instance, in the conceptualization of a solid object as fluid-substance-like

(‘ pulverization ’, cf. Langacker’s example above), or the conceptualization of

a fluid substance as filling a container with firm boundaries, or the placement

of a solid object within a fluid substance, and so on.

In spite of these similarities between verbal aspect and nominal quantity,

there are also important differences regarding the nature of boundedness

(closedness) in the two domains. Perhaps the most important difference is

that verbal boundedness is always boundedness in time and correlates with

the temporal features of the event : whether the event is ongoing or termin-

ated (imperfective vs. perfective), and whether it has an inherent endpoint or

not (atelic. vs telic). Nominal quantity, on the other hand, is not necessarily

distributed over time, though it may be, if the referent participates in-

crementally. In the verbal domain,

BOUNDEDNESS

is both a lexical semantic

feature of particular verbs and a feature of concrete usages of verbs (or of

whole clauses). Though these levels correlate, they need not always coincide,

as shown by the extensive studies on aspectual coercion (e.g. Michaelis 2004

T U O M A S H U U M O

86

and the references mentioned there). For instance, the verb run indicates a

basically unbounded activity, but sentences like He ran a mile or He ran from

school to the station refer to a bounded situation that ceases after the in-

dicated distance has been traversed. In the nominal domain, only count

nouns indicate a closed quantity as part of their lexical meaning. In contrast,

mass nouns are neutral with respect to quantity, since mass nouns receive

their quantificational interpretation only in concrete usage events. For in-

stance, the noun flour designates a substance, but without the context of an

actual usage event it is impossible to tell whether the quantity of the sub-

stance is to be conceived as closed (as in The flour is in the cup) or open (as in

There is flour in the cup).

Typically, the referent of a count noun participates in the situation

throughout and does not set a boundary to its duration. For instance, in

The girl patted the dog, the quantity of the participants ‘ girl ’ and ‘ dog ’ does

not set boundaries to the duration of the ‘ patting. ’ Both the girl and the

dog participate in the event throughout as wholes (not incrementally),

both already exist before the event and continue their existence after

the event. Neither of the participants is ‘ consumed ’ during the event. This

conceptualization is especially common and natural if the referent of the

NP is a solid object, whereas fluid substances more typically participate

gradually.

Indeed, the situation is different when a nominal referent (typically a

substance) participates in the event incrementally. In this case the extent

of the referent also determines the duration of the event. An incremental

participant is ‘ consumed ’ (either concretely or figuratively) during the pro-

cess, as in The boy was eating a sandwich or The professor was reading the

thesis, where the process reaches its endpoint when the whole referent of the

object has participated in it. Here the participation of the nominal referent is

incremental in an objective sense, i.e. the eating and reading are actually

affecting (or directed at) different parts of the sandwich or the thesis at sub-

sequent points of time. Since a sandwich and a thesis are bounded entities,

the activities that involve them as incremental participants are understood

as (aspectually) telic : they reach their endpoint when the whole entity has

participated. However, an incremental participant can also be quantitatively

open, resulting in aspectual unboundedness of the situation ; here the situ-

ation is continuously ‘ fed ’ by the incremental participant with new sub-

stance, as in Water was pouring out of the drain. Indeed, as pointed out by

Verkuyl (1993) and Krifka (1992 : 50), it may not be the activity of ‘ eating ’ or

‘ reading ’ as such that constitutes the boundedness in examples like He ate

the sandwich or She read the book ; rather, it is the nature of the object that

creates the boundedness (i.e. we typically eat entities or portions of some

kind, and read books, papers and other things, whose extension is bounded).

It is also possible that the incremental participation of a nominal referent in

a situation is based on subjective factors, such as an incremental scanning of

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

87

a nominal referent which is not affected itself or does not undergo a change

in the course of the event (see Talmy 2000 : 71 for details).

In the following sections, I will study nominal and verbal aspect and their

effects on the case marking of the object in Finnish, which reflects both

aspectual and quantificational factors. I begin by introducing the classical

view of Finnish object marking in section 2, where it is shown how the case

marking is determined by a complex interplay of aspect and quantity, and

often results in massive ambiguity. In section 3, I discuss certain problematic

usages that seem to contradict the general principles of object marking.

These usages often (though not always) involve incremental objects. In sec-

tion 4 I discuss examples where it is the subject (not the object) whose re-

ferent participates incrementally, and show how this affects the object

marking. In section 5 I return to one of the problematic object types dis-

cussed in section 3, the so-called quasi-resultative type, and show how this

static type can be associated with dynamic types where either the subject or

the object indicates an incremental participant. Section 6 sums up the results

of the study.

2. T

H E

F

I N N I S H O B J E C T M A R K I N G S Y S T E M

:

A N O V E R V I E W

One of the most problematic issues in Finnish grammar is without doubt the

case marking of the object (for literature in English, see e.g. Denison 1957 ;

Heina¨ma¨ki 1984, 1994 ; Helasvuo 2001 ; Huumo 2005). The case marking

of the object is part of a more extensive system of oppositions among the

grammatical cases of the language. The

PARTITIVE

case marks the object un-

der three conditions : a) in negated sentences, b) in aspectually unbounded

sentences (more precisely : atelic, progressive, cessative, and irresultative

(semelfactive) sentences), and c) in sentences where the object NP refers to an

open, indefinite quantity. Its counterpart is a morphologically heterogeneous

category which will be referred to here (following the recent descriptive

grammar ISK 2004) as the

TOTAL OBJECT

, designating what might be called

completeness of quantity or aspect or both. The case opposition between the

partitive and other grammatical cases works not only in the marking of the

syntactic object (Heina¨ma¨ki 1984, 1994 ; Chesterman 1991 ; Huumo 2005), but

also of the existential subject (see Helasvuo 2001, Huumo 2003) and the

predicate nominal (Huumo 2009), though under different conditions. Fur-

thermore, the ‘ total ’ cases that participate in the system vary from one

subtype to another. In existential subjects and predicate nominals, the total-

case counterpart of the partitive is always the nominative. In object marking,

the situation is more complicated : the total object can be marked with either

the nominative, the genitive, or the irregular accusative form of personal

pronouns (ending -t). Historically the object-marking genitive was an ac-

cusative case with the ending *-m, but it coalesced with the genitive -n as the

result of a sound change whereby word-final -m became -n. This sound

T U O M A S H U U M O

88

change caused a reanalysis of many infinitival constructions in the language,

such that many accusative-marked objects of finite verbs were reinterpreted

as genitive-marked subjects of infinitives (see e.g. Anttila 1989 : 103–104).

The choice of the case is based on an interplay of multiple factors,

including quantity, definiteness, the count vs. mass distinction, negation,

subject-verb agreement, and aspect. Among these factors, quantity and the

count vs. mass distinction are involved in all three main syntactic contexts of

the case opposition (existential subject, predicate nominal and object).

Negation requires the partitive marking of objects and existential subjects

but not of predicate nominals. Pure aspect (i.e. without quantity) affects the

case marking of the object only. In the following discussion, I will not deal

with predicate nominals (for these, see Huumo 2009) but will focus on object

marking ; subjects will be treated in section 4.

As mentioned above, there are three main factors that affect the case

marking of the object : quantity, aspect, and negation. The received view of

Finnish grammar (e.g. Chesterman 1991 : 93 ; Vilkuna 2000 : 119 ; ISK 2004 :

887) maintains that negation is the strongest of these conditions, followed by

aspect and quantity. That negation is the strongest condition is shown by the

fact that (practically) all objects of negated clauses take the partitive case,

whereas the case marking in affirmative clauses is determined by a complex

interplay between quantity and aspect. The effects of quantity can be seen

most clearly in expressions of a punctual achievement, since these indicate

a situation that is indisputably bounded and brings about an end result ; thus

aspect will not be a reason for using the partitive (certain exceptions are

discussed in Huumo, forthcoming). Consider (1)–(3), whose punctuality is

also reflected in the fact that they reject direct durative modifiers (which in

Finnish are marked like the total object and correspond semantically to the

English for an hour type)

2

.

(1)

Lo¨ys-i-n

kirja-n

(*minuuti-n).

find-

PST

-1

SG

book-

TOT

minute-

TOT

‘ I found a/the book (*for a minute). ’

(2)

Lo¨ys-i-n

voi-ta

(*minuuti-n).

find-

PST

-1

SG

butter-

PAR

minute-

TOT

‘ I found some butter (*for a minute). ’

(3)

Lo¨ys-i-n

voi-n

(*minuuti-n).

find-

PST

-1

SG

butter-

TOT

minute-

TOT

‘ I found the butter (*for a minute). ’

[2] The following abbreviations are used in the glosses :

ABE

=abessive,

ABL

=ablative,

ADE

=adessive,

ART

=article,

CONNEG

=connegative verb form (=the form of the main verb

when used with a negator),

ELA

=elative,

GEN

=genitive,

ILL

=illative,

IPFV

=imperfective,

INE

=inessive,

INF

=infinitive,

NEG

=negation verb,

NOM

=nominative,

PAR

=partitive,

PL

=plural,

PRS

=present tense,

PTCP

=participle,

PST

=past tense,

PX

=(Xth person) pos-

sessive suffix,

SG

=singular,

TOT

=total object.

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

89

In (1) the object is a count noun and refers to a bounded entity (thus to

a closed quantity) ; therefore the total object must be used. The punctual

nature of (1) also excludes an aspectual partitive. In (2) and (3) the object is

a mass noun, which can be differentially quantified by means of the case

opposition. The partitive in (2) indicates that the quantity of the butter

is open (‘ some butter ’), whereas the total object in (3) indicates a closed

quantity of a definite referent (‘ the butter ’).

At the other end of the aspectual scale we have atelic verbs that indicate

an unbounded situation, i.e. an activity or a state. In such examples the

unbounded aspect requires the partitive even if the object is a count noun or

a mass noun indicating a closed quantity. Such examples do allow direct

durative modifiers (consider examples (4) and (5) ; however, see also section

3.2 for exceptions).

(4)

Pitel-i-n

ka¨de-ssa¨-ni

kirja-a

y voi-ta

(tunni-n).

hold-

PST

-1

SG

hand-

INE

-1

SGPX

book-

PAR

butter-

PAR

hour-

TOT

‘ I was holding

y held [a/the] book

y [the/some] butter in my hand (for an hour).’

(5)

Rakasta-n

sinu-a

y olut-ta.

love-

PRS

.1

SG

you-

PAR

beer-

PAR

‘ I love you. ’

y ‘I love beer.’

Example (4) indicates an activity and example (5) a state. As shown by the

English translation of (4), the object marking does not reveal whether the

quantity of the butter is open or closed. This is because the unbounded

aspect demands the partitive in any case. The aspectual function of the par-

titive thus ‘ conceals ’ the quantity of the referent. In (5) the situation is ab-

stract and therefore the question of quantity does not arise : the object does

not refer to an actual instance of beer that could be quantified but is under-

stood as generic. Note, too, that the unboundedness of the situation in (4)

can be understood in two different ways : as progressivity (‘ was holding ’) or

as cessativity ‘ held ’, where the event has ceased without reaching an end

point (Sasse 2002 : 206 uses the term

DELIMITATIVE

for this type of aspect). In

some languages there are aspectual grams that specifically indicate delimi-

tative meanings ; for instance Russian has verb prefixes whose meaning is

roughly ‘ to do X for a while ’ (see Dickey 2007 and Janda 2007, who calls

such events

COMPLEX ACTS

). As example (4) shows, there is no specific way of

indicating cessativity in the Finnish system ; this is just one possible in-

terpretation of the polysemous partitive object. However, the fact that it is

the partitive and not the total object that is used to indicate cessativity clearly

shows how the total object requires more than just a perfective viewpoint (i.e.

the fulfilment of an accomplishment) to be available.

Examples like (4) also demonstrate that a partitive object is able to indicate

pure quantity only if it does not indicate unboundedness, that is, only in

aspectually bounded examples like (2). Similar observations have been made

T U O M A S H U U M O

90

in the literature on aspectual coercion. For instance, de Swart (1998 : 349)

argues that a progressive predication such as Anna was running a mile does

not licence the inference that Anna actually ran a mile ; when focusing on the

ongoing activity, the progressive conceals the projected end result of the

event. Thus, according to de Swart, the semantics of the progressive involves

‘ stripping an event of its culmination point ’ (p. 355). Similarly, the Finnish

partitive in unbounded sentences often conceals the projected overall quantity

of the object NP. Unlike the object in examples (2) and (3), the object in

example (4) is unable to indicate the quantity of its referent by case alteration,

because the unboundedness of the aspect excludes the total object altogether.

Among the conditions motivating object case marking, accordingly, aspect

appears to be stronger than quantity. This is why many grammars of Finnish

(e.g. Chesterman 1991, Vilkuna 2000) represent the three conditions for the

partitive object in the form of the hierarchy

NEGATION

>ASPECT>QUANTITY

,

where negation is the strongest condition (requiring the partitive irrespective

of quantity and aspect) and aspect is the second-strongest (requiring the

partitive irrespective of quantity). However, as the following discussion will

show, this hierarchy is a simplification, and matters are in fact more com-

plicated.

Leaving aside punctual and atelic examples for the moment, I will now

discuss the case marking in examples that indicate accomplishments, i.e. non-

punctual telic events that develop gradually towards their endpoint. In such

examples the total object indicates the combination of bounded aspect and

closed quantity, whereas the partitive usually has many possible interpret-

ations. In this type, the partitive but not the total object allows a direct

durative modifier in the same clause. Consider examples (6) and (7), where

the star in parentheses indicates the ungrammaticality of the total object

version in the presence of the durative modifier.

(6)

Lu-i-n

kirja-a

y (*)kirja-n

(tunni-n).

read-

PST

-1

SG

book-

PAR

book-

TOT

hour-

TOT

‘ I was reading the book

y read the book (for an hour).’ [

PAR

]

‘ I read the [whole] book. ’ [

TOT

]

(7)

So¨-i-n

puuro-a

y (*)puuro-n

(tunni-n).

eat-

PST

-1

SG

porridge-

PAR

porridge-

TOT

hour-

TOT

‘ I was eating (the) porridge ’

y ‘I ate (some of the) porridge (for an hour).’ [

PAR

]

‘ I ate up the porridge. ’ [

TOT

]

As the English translations indicate, the partitive indeed has a considerable

variety of possible interpretations. First, it can have the aspectual function of

indicating either a progressive or a cessative reading where the event has been

interrupted (terminated before reaching its possible endpoint). These readings

are both possible in the partitive versions of (6) and (7), as the English trans-

lations show (‘ I was reading the book ’ vs. ‘ I read the book (without finishing

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

91

it) ’ in (6) ; ‘ I was eating the porridge ’ vs. ‘ I ate (some of the) porridge ’ in (7)).

Another reading of the partitive is the quantificational one, which applies if

the event itself has been completed but the quantity of the object NP is open.

When considering examples (6) and (7), it should be kept in mind that the

hierarchy

NEGATION

>

ASPECT

>

QUANTITY

represents the situation from the

viewpoint of the partitive object, not of the total object, which can only be

used if the sentence does not meet

ANY

criterion of the partitive (however, in

section 3.2, this principle too turns out to be problematic). Thus aspectual

factors (boundedness) alone cannot trigger the total object unless the quan-

tity indicated by the object NP is closed.

If we consider example (7) in more detail, we see that the alternative in-

terpretations of the partitive set up another kind of a hierarchy. With the

progressive reading, the partitive object conceals the (projected) quantity of

the object referent : the example does not tell whether the projected endpoint

of the event would involve a closed or an open quantity of porridge (the

opposition between ‘ I was eating porridge ’ and ‘ I was eating

THE

porridge ’).

The same ambiguity arises in the cessative interpretation where the activity

has been interrupted : again, we do not know whether the event had been

proceeding towards an endpoint involving a closed quantity (‘ I ate some of

the porridge ’) or not, in which case the partitive object indicates open quan-

tity of the porridge eaten so far (‘ I ate some porridge ’). In sum, examples (6)

and (7) show that the total object is used only if the situation has both

reached its endpoint and has affected a closed quantity (‘ I ate up the por-

ridge ’). They also show that the multifunctional nature of the partitive often

gives rise to ambiguity, and when indicating a more dominant function (e.g.

progressivity) the partitive conceals less dominant features that it can indi-

cate in other contexts (quantity).

Finally, it needs to be pointed out that, in addition to progressivity and

cessativity, there is yet another aspectual function for the partitive, which in

the Finnish tradition is referred to as

IRRESULTATIVITY

(discussed in Huumo

forthcoming). An irresultative situation is (typically) punctual (at least

bounded) but fails to bring about a substantial end result that would mo-

tivate the use of the total object and is thus atelic. Its opposite is a resultative

situation which is conceptualized as involving a fundamental, often irre-

versible change of state in the object referent. On the basis of the resultativity

vs. irresultativity opposition, Finnish punctual verbs can be divided into two

groups : resultative (accomplishment/achievement) verbs like tappaa ‘ kill ’,

ostaa ‘ buy ’, huomata ‘ notice ’ and lo¨yta¨a¨ ‘ find ’ that take the aspectual total

object, and irresultative (semelfactive) verbs like to¨na¨ista¨ ‘ nudge ’, mulkaista

‘ glance ’ and lyo¨da¨ ‘ hit ’ that take the aspectual partitive object. The re-

sultative total object thus indicates a transition : the event brings about a

change, after which it does not return to its original state but enters another

one. The partitive, on the other hand, indicates that no such transition takes

place and that immediately after achieving its target state the situation

T U O M A S H U U M O

92

returns to the original state (or to a state that is conceptualized as similar to

the original state). Croft (forthcoming) calls these different situation types

DIRECTED ACHIEVEMENTS

and

CYCLIC ACHIEVEMENTS

, respectively, and points

out that directed achievements can be further divided into two classes : re-

versible ones, such as open, and irreversible ones, such as break or die. A

different terminology is used by Smith (1997), who draws a distinction be-

tween two punctual situation types,

ACHIEVEMENTS

(which result in a change)

and

SEMELFACTIVES

(which do not bring about a change). At a crude level,

such distinctions also reflect the resultativity opposition between the Finnish

object markers. However, there are certain uses of the partitive that do not

properly fit such a classification. For instance, Leino (1991) points out that

the verb vaihtaa ‘ change ’ often takes the partitive object in cases where one

realization of the object replaces another and where the two realizations both

belong to the same category – even though such a change would count se-

mantically as an accomplishment (8).

(8)

Vaihdo-i-n

paita-a.

change-

PST

-1

SG

shirt-

PAR

‘ I changed my shirt ’.

In example (8) the person takes off one shirt and puts on another, which

would be expected to count as an accomplishment, but nevertheless the

partitive object is used. What is also noteworthy in (8) is the number of the

object : it is in the singular though actually there are two referents.

Other exceptional instances include punctual verbs that allow both a re-

sultative and an irresultative interpretation of the situation they indicate

(and thus an alteration between the partitive and the total object). The best-

known example is the verb ampua ‘ shoot ’ in (9), discussed by Heina¨ma¨ki

(1984).

(9)

Ammu-i-n

lintu-a

y linnu-n.

shoot-

PST

-1

SG

bird-

PAR

bird-

TOT

‘ I was shooting [aiming at] the bird. ’

y ‘I shot [at] the bird [but failed to kill it].’ [

PAR

]

‘ I shot the bird [dead]. ’ [

TOT

]

With the total object, the verb ‘ shoot ’ indicates resultativity, i.e. the death

of the bird as a result of the shooting. With the partitive object it indicates

the irresultativity of the shooting. In addition, the partitive also has a

PROSPECTIVE

3

reading where it indicates a phase that precedes the actual

[3] Smith (1997) and Croft (forthcoming) also discuss examples such as She almost crossed the

river, where accomplishments are ambiguous between the reading where the event did not

occur at all (the crossing of the river was not even started) and the reading where it occurred

but was not completed (she did not reach the other side of the river). It is interesting that

Finnish object marking sometimes reflects this kind of opposition : in the Finnish

counterpart of the above example (Ha¨n melkein ylitti jokea

y joen [s/he almost crossed

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

93

event. Thus (9) also shows that achievement verbs must be divided into two

classes :

PROPER ACHIEVEMENTS

that do not allow the partitive object to indi-

cate a prospective viewpoint aspect (e.g. lo¨yta¨a¨ ‘ find ’ in examples (1)–(3))

and

EXTENDED ACHIEVEMENTS

that allow the prospective viewpoint aspect.

The resultative vs. irresultative opposition is also relevant with certain

verbs that indicate the causation of a gradual change-of-state in the patient,

e.g. lyhenta¨a¨ ‘ shorten ’ and la¨mmitta¨a¨ ‘ warm ’. Smith (1997 : 24) calls such

events

DEGREE PREDICATES

and Croft (forthcoming)

DIRECTED ACTIVITIES

; and

both argue that such verbs indicate a directed change that has no natural end-

point. However, an endpoint can be conceptualized into the event, and this

opposition is reflected in the Finnish object marking : with the total object

these verbs indicate an abrupt, absolute change (‘ make short/warm ’), but

with the partitive object they indicate a gradual, scalar change with no par-

ticular endpoint (‘ make [somewhat] shorter/warmer ’). The situation is further

complicated by the fact that these verbs are not punctual but durative, and

therefore the partitive can also receive the progressive reading. Consider (10).

(10)

Lyhens-i-n

hame-tta

y hamee-n.

shorten-

PST

-1

SG

skirt-

PAR

skirt-

TOT

‘ I was shortening the skirt. ’

y ‘I shortened the skirt [somewhat].’ [

PAR

]

‘ I shortened the skirt. ’ [

=made it short] [

TOT

]

It should be pointed out that the aspectual opposition here called re-

sultativity vs. irresultativity is quite different from the opposition observed

in accomplishments : here it is related to the nature of the end result of the

event, and the relevant factor is

NOT

whether the event has been brought to

its possible endpoint or not (as in ‘ reading a book ’) but the nature of the

endpoint itself. In many grammatical descriptions of Finnish, however, the

term irresultative has also been used to refer to durative events that have not

been brought to their endpoint, and it needs to be emphasized that my usage

of the term is somewhat narrower. It is also worth noting that although (10)

would most naturally be classified as an accomplishment, its object marking

seems to correspond to that of accomplishments only partially (i.e. when the

partitive indicates progressivity). The fact that the irresultative reading is

also possible for the partitive shows that such situations can also be con-

ceptualized as semelfactives.

Next consider negation. Keeping in mind that negation requires all objects

to be marked with the partitive, we can expect that negated examples will

have even more possible readings than affirmative examples like (10). Indeed,

as pointed out by Itkonen (1976), examples like (11) may have as many as

six possible readings, taking into account both aspect and quantity, if we

river-

PAR

y river-

TOT

]) the total object would mean that the crossing was not completed,

whereas the partitive would mean that the crossing was not even initiated (cf. also the

English progressive She was almost crossing the river).

T U O M A S H U U M O

94

consider all alternatives from the viewpoint of the corresponding affirmative

sentence that has been negated.

(11)

En

voidel-lut

y

suks-i-a.

NEG

.1

SG

wax-

PST

.

CONNEG

ski-

PL

-

PAR

‘ I was not waxing

y did not wax [the] skis.’

Note first that the affirmative counterpart of (11) could have either the total

object (‘ I waxed the skis ’) or the partitive object (‘ I was waxing [the] skis ’ ;

‘ I waxed some [of the] skis ’). The total object would indicate bounded aspect

together with a closed quantity, which in turn could be understood in two

ways : it could consist either of one pair of skis or of a larger but closed

quantity of (pairs of) skis. The affirmative partitive in turn could have two

aspectual readings (the same as in example (10)). First, it could have the

progressive reading, which would again conceal whether the event is con-

ceptualized as an accomplishment or an activity, i.e. whether it is progressing

towards a closed quantity of skis or not (‘ I was waxing the skis ’ vs. ‘ I was

waxing skis ’). Second, the partitive could have the cessative reading, main-

taining the same ambiguity of the overall quantity (‘ I waxed some [of the]

skis ’). The negative partitive conceals all these possibilities and focuses only

on the fact that the event did not take place at all.

To sum up, it is easy to see that the general function of the partitive is

to indicate the

INCOMPLETENESS

of the situation in one way or another

(a generalization suggested by Leino 1991) : either the situation does not take

place at all (negation), or it does not reach an endpoint (atelic/cessative/

progressive), or it reaches its endpoint but does not affect a closed quantity of

entities. It is also noteworthy that the partitive often implies either an actual

or a potential continuation of the event. In the progressive reading, the event

is actually ongoing, and in the cessative reading it could potentially be

carried on further. In the reading involving an open quantity, the event could

(in many cases) be continued so as to affect a larger quantity of entities. It is

only the irresultative partitive that lacks such an implication – this is because

the event type indicated by the verb is itself one lacking a relevant end result.

The total object, on the other hand, indicates that the event has been brought

to its endpoint and that the activity has affected a closed quantity in full.

Thus a potential continuation of the event is excluded, though it may be

possible to repeat the event (e.g. to read a book again).

The above discussion also shows that the lexical aspectual situation type of

the examples is in many ways crucial to the selection of the object marker. In

contrast, viewpoint aspect can be explicitly expressed by the object case only

in certain situation types. The unbounded situation types, i.e. states and

activities, require the partitive object irrespective of quantity and viewpoint

aspect (examples (4) and (5) ; exceptions will be discussed in section 3). In

unbounded situation types the partitive thus cannot unequivocally indicate

viewpoint aspect, though it can often be interpreted with this kind of

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

95

a meaning. Among the bounded situation types, accomplishments trigger the

total object if the situation has been brought to its endpoint and if the

quantity of the object NP is closed and its entire referent has participated in

the event. In accomplishments, the partitive can indicate a cessative or pro-

gressive viewpoint aspect, or (if not interpreted as indicating one of these

viewpoint aspects) an open quantity of the object referent. The two punctual

situation types, achievements and semelfactives, do not allow the progressive

or cessative readings for the partitive, since the situations they indicate are

not durative. Proper achievements (‘ notice ’, ‘ find ’) take the aspectual total

object (or the quantificational partitive), but extended achievements (in

Finnish, verbs meaning e.g. ‘ shoot ’, ‘ buy ’, ‘ kill ’) allow the aspectual par-

titive to indicate a prospective viewpoint aspect – that the event is about to

take place or that the referent of the subject is attempting the achievement.

Semelfactives always take the partitive object, since in spite of their temporal

boundedness they are atelic and lack an end result. However, as example (8)

shows, the division of punctual verbs into achievements and semelfactives is

far from clear-cut, and as example (9) shows, some punctual verbs (‘ shoot ’)

can take both kinds of object marking depending on the conceived nature of

the end result. An even more complicated case in point involves so-called

degree predicates like ‘ warm ’, ‘ lengthen ’ or ‘ shorten ’ (example (10)). These

resemble accomplishments in that they are durative and thus allow the pro-

gressive partitive (10). However, the object marker also participates in the

resultative vs. irresultative opposition with degree predicates : it can reflect

the conceived nature of the end result (gradual vs. absolute). The overall

situation is summarized in table 1, which indicates the readings available for

the partitive object in each situation type.

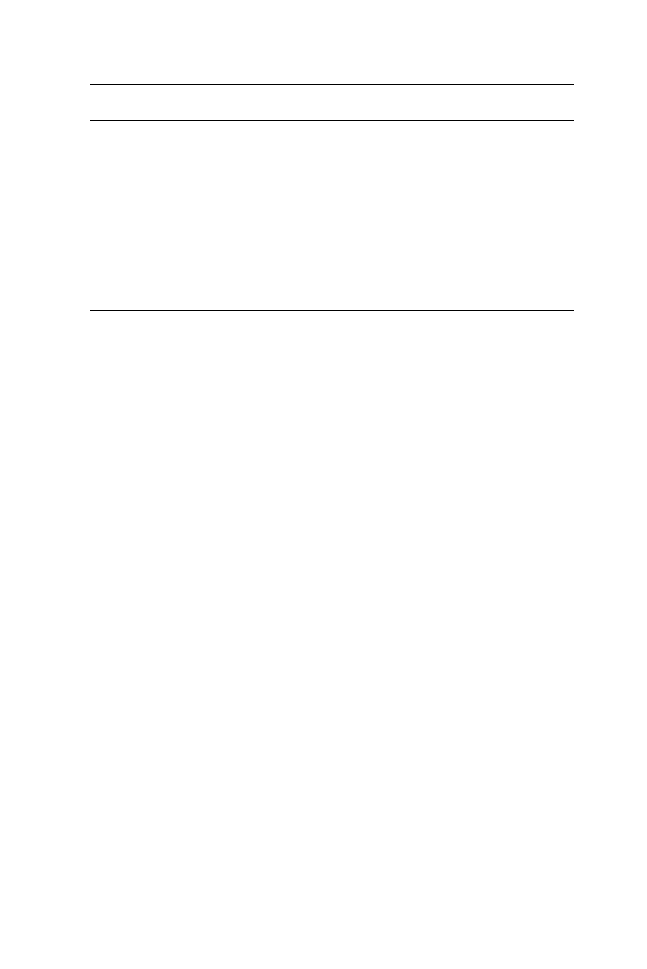

Viewpoint aspect

Prog.

Cess.

Prosp.

Irres.

Quantity

Situation type

Activity

+

(

+)

(

+)

–

–

(

+)

State

+

–

(

+)

–

–

(

+)

Accomplishment

+

+

–

–

+

Proper achievement

–

–

–

–

+

Extended achievement

–

–

+

–

+

Semelfactive

+

–

–

–

(

+)

(

+)

Achievement/

Semelfactive

–

–

+

+

+

Degree predicate

+

–

–

+

+

Key : Prog.

=Progressive; Cess.=Cessative; Prosp.=Prospective; Irres.=Irregulative

Table 1

The functions of the partitive object

T U O M A S H U U M O

96

In each row of the table, the possible readings of the partitive are marked

with a plus (

+) mark. As can be seen, there is a plus mark immediately

following the name of certain situation types. These are the atelic situation

types that exclude the total object altogether : activities, states and se-

melfactives. The other situation types, which do not have a plus mark after

their name, allow viewpoint aspect and quantity to determine the case of the

object. As can also be seen, some of the plus marks in the table are in par-

entheses. A bare plus mark indicates a function that can be the

SOLE FACTOR

motivating the partitive object. Parentheses around the plus mark indicate

that the partitive

ALLOWS

the interpretation with the function in question, in

addition to another function. This happens in situation types that require the

partitive in any case but can have different aspectual readings for it. For

instance, the partitive object in an activity expression can have either a pro-

gressive or a cessative reading, but since the atelic nature of the situation type

requires the partitive anyway, these functions remain only possible alterna-

tive interpretations. In contrast, the partitive object of an accomplishment

verb can

SPECIFICALLY

indicate progressive or cessative aspect, or open

quantity. The same principles work in quantification : in atelic situation types

that require the aspectual partitive anyway, the partitive cannot unequi-

vocally indicate open quantity (it remains indifferent to quantity). In con-

trast, the telic situation types allow the partitive to have a quantificational

reading – but only if its viewpoint aspectual readings do not apply. If inter-

preted as indicating viewpoint aspect, the partitive again becomes indifferent

to quantity.

Above I have discussed object case marking from the point of view of the

partitive object, trying to pin down the factors motivating it within each

aspectual type. Alternatively, the system can be approached from the point

of view of the total object, the usage conditions of which turn out to be

simpler : the total object is used in (affirmative) accomplishment and

achievement expressions with a perfective viewpoint (thus excluding pro-

spective, progressive and cessative viewpoints), on condition that the object

indicates a closed quantity that has participated in the event in its entirety.

At a crude level, the opposition between the partitive and the total object

thus seems to follow the principle suggested by Leino (1991) : the partitive

indicates incompleteness of the situation in one way or another. This expla-

nation strives towards a central objective of all scientific investigation : gen-

eralization. However, an adequate explanation must also be able to deal with

problematic instances, and one should not strive towards generalization at

the expense of the facts. Though a widespread consensus prevails among

scholars of Finnish grammar that the three factors of negation, aspect and

quantity explain the case marking of the object, and that more general terms

such as boundedness or incompleteness represent useful and valid general-

izations, there remain a few problematic instances that are not easily ex-

plained by such general principles. These include particular uses of both the

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

97

partitive and the total object. First, the partitive is used in certain examples

that are aspectually bounded and cannot proceed further in time ; thus the

total object would be expected (Huumo forthcoming). Second, the total

object is used in certain examples indicating situations that are aspectually

unbounded ; thus the partitive would be expected. Some of these uses have

been discussed in some detail in the literature, while others have escaped the

attention of scholars.

In the following discussion it will be argued that the generalizations con-

cerning Finnish object marking have given too much weight to what has

been taken to be the prototype situation for these oppositions, that is, an

aspectual opposition which involves as one pole a telic, non-punctual and

thus an accomplishment-type situation that gradually proceeds towards

its endpoint, finally reaches it and thereby attains completion. In English,

such examples include I took

y was taking the letter to the post office (non-

incremental object) or I read

y was reading the book (incremental object);

to understand the Finnish object marking properly we need to pay attention

to incremental and non-incremental instances in each opposition type.

The problematic instances to be discussed in the following sections involve

expressions that indicate unbounded situations but nevertheless select the

aspectual total object. In section 3 I will argue that the motivation for using

the total object in such instances is indeed boundedness of aspect or quantity

(or both), but a type of boundedness that differs fundamentally from the

canonical kind that gets realized only after cumulating gradually over time.

The type of boundedness that will be relevant here, to be called

CONTINUOUS

BOUNDEDNESS

, is one that obtains throughout the entire situation, at any given

point of time during its duration. In section 3.1, I will discuss two types

of usage of the total object that have received attention in earlier work,

i.e. habitual expressions and so-called quasi-resultative sentences (Huumo

2005). Habitual expressions are aspectually dual in the sense that they indi-

cate the iteration of an event that may itself be bounded. Since the quantity

of the iterations is unbounded, the overall situation is also unbounded, even

though its component situations may be bounded. It will be shown that in

habitual examples, Finnish aspectual object marking reflects the nature of the

component situations, not the overall habitual situation, although the dur-

ation of the latter can however be indicated by durative adverbs. The quasi-

resultative type consists of stative situations which, according to the analysis

of Huumo (2005), are conceptualized as ‘ frozen ’ fictive accomplishments

that extend over time. In section 3.2 the focus is on two usage types that have

not been discussed previously : continuous completives (accomplishments/

achievements) and continuously bounded quantities. It is in these latter two

types that we need to draw a distinction between

OVERALL ASPECT

(classical

aspect, proceeding and cumulating in time) and another type of aspect,

henceforth called the

TRANSIENT ASPECT

, which is orthogonal to the time axis

and thus gives a characterization of the ‘ cross-section ’ of the situation at any

T U O M A S H U U M O

98

given point of time, i.e. whether the indicated relationship is conceptualized

as bounded or unbounded at any given point of time during the event. It is

argued that transient aspect plays a central role in Finnish object marking

and needs to be taken into account in order to give a coherent picture of the

grammatical systems involved in aspectual object marking.

3. T

H E T O T A L O B J E C T A S I N D I C A T O R O F C O N T I N U O U S

B O U N D E D N E S S

The fact that the total object can be used in unbounded examples shows that

the general rules of Finnish object marking fail to explain certain usages that

are of crucial importance to the theory of aspect. In this section it is argued

that even in such problematic instances the function of the total object is to

indicate boundedness (of aspect or quantity), but of a type that differs from

the canonical type where boundedness equates to the reaching of an endpoint

where the event itself culminates. In the instances to be discussed below,

boundedness prevails

CONTINUOUSLY

: the situation does not develop towards

an endpoint but consists of a continuous force-dynamic interaction (in the

sense of Talmy 2000 : 409–470) that serves to keep the situation complete at

each point of time, as in the English example This brush cleans the conveyor

belt before it enters the machinery (‘ continuously keeps the conveyor belt in

the state of total cleanliness ’).

In the same way as canonical boundedness, continuous boundedness can

be based either on aspect alone or on a combination of aspect and quantity.

When the continuous boundedness of a situation is purely aspectual, the

situation is conceptualized as a continuous completive (a higher-order term

for accomplishments and achievements) where a force-dynamic interaction

between an actor and an undergoer keeps the undergoer in a state conceived

as completed, or

RESULTATIVE

, as the classical Finnish terminology puts it (see

also Huumo forthcoming). This means that the situation cannot develop

towards an even greater perfection ; on the other hand, without the con-

tinuous force-dynamic interaction the situation would cease to obtain and

the undergoer would leave its resultative state. Correspondingly, when the

continuous boundedness of the situation is motivated by a combination of

bounded aspect and closed quantity, the object is incremental and changes its

reference through time but at the same time indicates closedness of quantity

at each individual point of time. More concretely, such a sentence means that

CONTINUOUSLY ALL

substance (or multiplicity of individuals) that enters the

situation is brought into a new, resultative state by the force-dynamic inter-

action indicated by the verb.

In sections 3.2 and 3.3 I will discuss such examples in detail ; I will refer to

the two types as

CONTINUOUSLY CLOSED QUANTITIES

and

CONTINUOUS COM-

PLETIVES

. First, however, I will discuss in section 3.1 two other types where

the total object is used in unbounded sentences. These types have been dealt

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

99

with in the literature to some extent, and they are closely related to the new

types introduced here. The first type consists of habitual or generic examples,

and the second type of so-called quasi-resultative examples (for these, see

Huumo 2003). After this, I will proceed to continuous boundedness.

3.1 The habitual and the quasi-resultative types

In the literature, two kinds of uses of the total object in unbounded sentences

have been distinguished : the habitual-generic type and the so-called quasi-

resultative type. In the linguistic literature on aspectual coercion, a lot has

been written about habitual and generic expressions, with a consensus pre-

vailing that habitual and generic expressions coerce dynamic expressions

into static ones (see e.g. Carlson & Pelletier 1995, de Swart 1998 : 383).

However, Michaelis (2004 : 5, 20–21) points out that as far as their internal

composition is concerned, habitual situations are isomorphic to iterated

events, i.e. activities. Langacker (1999 : 251) argues that although a habitual

or generic expression indicates a situation that occurs repeatedly, this rep-

etition can be generalized into a continuously prevailing state in the

STRUCTURAL

plane, which ‘ comprises event instances with no status in actu-

ality ’ and is thus different from the

ACTUAL

plane, which ‘ comprises event

instances that are conceived as actually occurring ’. According to Langacker,

habitual and generic expressions differ from repetitive (iterative) ones in the

sense that the latter remain in the actual plane : ‘ A repetitive expression

profiles a higher-order event residing in the actual plane, whereas habituals

and plural generics – grouped as general validity predications – profile

higher-order events in the structural plane ’. Croft (forthcoming) emphasizes

that habitual expressions involve a repeated sequence of events which are

characteristic of a particular individual, and that, in this sense, such expres-

sions construe the regular recurrence of the event as an inherent state of the

individual.

For our present analysis the relevant factor is the necessity of distin-

guishing between two levels in habitual expressions : the level of the indi-

vidual component situations and the (virtual) level of the more abstract

habitual state itself. Such a division between the two levels explains the facts

of Finnish object marking quite neatly : the case of the object is determined

by the nature of the component situations, even though there may be other

aspectual elements present (such as durative modifiers) that relate to the

event at the more abstract level of the habitual state. The stative meaning of

habitual expressions can thus be seen as another kind of viewpoint aspect,

which is not internal but external to the actual events : it expands the view-

point of the conceptualization from singular component events to a con-

tinuous habitual state. The selection of the Finnish object case depends in all

respects on the type of the component situations. If the component situations

fulfil the general criteria for the total object, then the total object is used even

T U O M A S H U U M O

100

though the habitual reading makes the overall situation unbounded at the

structural level. The aspectual unboundedness of the overall habitual situ-

ation is shown by the fact that a direct durative modifier can be used in spite

of the presence of the total object, which normally rejects such modifiers

because of the boundedness it indicates (cf. example 3 above). This excep-

tional compatibility of such otherwise incompatible elements is explained by

the fact that they indicate boundedness at two different levels. Consider (12)

and (13).

(12)

Ole-n luke-nut lehde-n

kirjasto-ssa jo

vuode-n aja-n.

be-1

SG

read-

PTCP

paper-

TOT

library-

INE

already

year-

GEN

time-

TOT

‘ For a year already, I have been reading the newspaper in the library. ’

(13)

Leikkas-i-n

nurmiko-n yksin koko kesa¨-n.

mow-

PST

-1

SG

lawn-

TOT

alone whole summer-

TOT

‘ For the whole summer I mowed the lawn alone. ’

The total object in (12) and (13) gets its motivation from the bounded nature

of the component situations : the examples indicate that, each time, the whole

paper is read (12) and the entire lawn is mown (13). The component situations

underlying the habitual state are thus accomplishments. At the habitual level,

the situation is static and thus unbounded : the person has the habit of

reading the paper in the library or mowing the lawn. It is this habitual state

whose duration is indicated by the durative modifier : in (12) the durative

modifier indicates that the habit of reading the paper in the library has lasted

for a year. The exceptional compatibility of the total object and the durative

modifier is thus explained by the fact that they indicate boundedness at two

different levels : the total object indicates the boundedness of each component

situation (i.e. the reading of the whole paper on each occasion), whereas the

durative modifier sets temporal boundaries to the overall habitual state. It is

worth noting that in this respect Finnish differs from many other languages,

such as French or Russian (discussed by Smith 1997) which use imperfective

verb forms in habitual expressions – a point I return to below.

A more problematic usage of the total object is the one called the quasi-

resultative type (QR, see Huumo 2003). QR sentences are aspectually static

and unbounded but nevertheless take the total object, which makes them

appear an anomaly. The term

QUASI

-

RESULTATIVE

was originally suggested by

Itkonen (1976) to characterize the exceptional object marking of such ex-

amples : QR sentences resemble bounded sentences (

RESULTATIVES

in the

traditional terminology) in form but are semantically unbounded. Itkonen

associated the phenomenon with particular verbs, and distinguished three

classes of QR verbs : 1) non-agentive perception verbs such as ‘ see ’, ‘ hear ’, 2)

non-agentive mental verbs such as ‘ know ’, ‘ remember ’, and 2) transitive

verbs indicating locative relationships (in a broad sense). It is noteworthy

that like the habitual sentences discussed above, QR sentences also accept a

direct durative modifier. Consider (14)–(17).

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

101

(14)

Na¨e-n

ha¨ne-t

koko aja-n.

see-

PRS

.1

SG

s/he-

TOT

all

time-

TOT

‘ I [can] see him/her all the time. ’

(15)

Ole-n

tien-nyt

se-n

jo

viiko-n.

be-

PRS

.1

SG

know-

PTCP

it-

TOT

already week-

TOT

‘ I have known it for a week already. ’

(16)

Kuusi kuukaut-ta lumi peitta¨-a¨

maa-n.

six

month-

PAR

snow cover-

PRS

.3

SG

land-

TOT

‘ For six months, snow covers the land. ’

(17)

Vesi

ta¨ytta¨-a¨

ammee-n.

water fill-

PRS

.3

SG

tub-

TOT

‘ Water fills the tub. ’ [

=the tub is full of water]

In the above examples, (14) has a non-agentive perception verb, (15) has a

non-agentive mental verb, while (16) and (17) indicate a locative relationship

in a transitive construction. As pointed out by Leino (1991), the meaning of

examples like (16) and (17) involves a sense of continuous completeness : the

land is totally covered with snow and the tub is completely full of water.

Note, however, that the overall aspect of such examples is unbounded, and

therefore, according to the hierarchy of the Finnish object marking rules, the

partitive would be the expected case. Such examples also illustrate the fact

that many (non-agentive) perception and mental verbs and transitive verbs

of location can be used in the quasi-resultative pattern. In fact, it is some-

what misleading to talk about specific ‘ QR verbs ’, especially as far as group 3

is concerned, since many different verbs may appear in this pattern. It is,

rather, the compatibility of the meaning of the verbs and the QR pattern that

is relevant here.

Different explanations for the QR pattern have been proposed (see Huumo

2005 for a summary and discussion), ranging from historical explanations

to the semantic explanation suggested by Denison (1957) and elaborated by

Huumo (2005), according to which a conceptualization based on

FICTIVE

DYNAMICITY

(in the sense of Talmy 2000 : 99–175) motivates the total object

in such constructions. According to this latter explanation, the QR pattern

represents the conceptualization of a static situation as involving fictive

dynamicity – a fictive change that is brought to its end phase. Fictive dyn-

amicity is a concept introduced by Talmy (2000) in his extensive study on

cognitive semantics. He demonstrates how fictive dynamicity is a widespread

conceptualization strategy in language and how it can be argued to motivate

numerous usages of semantically dynamic lexical items (such as motion

verbs) and grammatical markers to express situations that are actually static

in the extralinguistic reality. The most celebrated examples of fictive motion

are expressions that indicate the static position of an elongated entity (such

as a road, a river, or a mountain range) by representing it with a motion verb

and locative elements indicating directionality, e.g. The highway goes from

T U O M A S H U U M O

102

Tartu to Tallinn (

yfrom Tallinn to Tartu); This mountain range extends all

the way from Mexico to Canada (

yfrom Canada to Mexico). It is clear that

the directionality indicated in such examples is purely subjective, since the

extralinguistic situation is static and involves no motion. This is also shown

by the fact that the extralinguistic situation remains the same even if the

directionality changes into its opposite, as shown by the two versions of the

above examples. If a similar change were to be made in an expression of

actual motion (The bus goes from Tartu to Tallinn

y from Tallinn to Tartu),

the referent situations would also have to be different.

Talmy demonstrates that in addition to such canonical expressions

of fictive motion there are many other types of linguistic expressions that

make use of dynamic elements to indicate static situations via fictive dyn-

amicity (see Talmy 2000 for a more detailed analysis). To give a few examples,

dynamic verbs of appearance can be used to indicate the permanent presence

of an entity in a location (The palm trees cluster around the oasis ; This rock

formation appears near volcanoes), and many expressions indicating a cog-

nitive (perceptive) relationship between a human being and the surrounding

world represent such a relationship as involving directionality, even though

the actual situation involves no motion (e.g. I can see you from where I’m

standing ; From my bedroom window I can see all the way to the mountains ;

for directionality in Finnish expressions of perception see Huumo 2010,

and in Finnish expressions of other kinds of mental relationships, Huumo

2006).

What connects the Finnish QR pattern with the phenomenon of fictive

dynamicity is that though QR expressions are apparently static, they have

many features that seem to point to an underlying dynamic conceptualization.

For instance, many verbs available in the QR construction are aspectually

ambiguous : they may indicate either a state or an accomplishment/achieve-

ment. Both meanings can plausibly be regarded as basic lexical meanings of

the verbs, although an alternative is to treat one of these meanings as basic

and the other as a result of aspectual coercion (see Michaelis 2004 : 53–54

who examines English verbs such as remember and fill). However, since it is

less than clear which of the meanings should be considered the primary one

(and on what basis), I prefer to consider the static and dynamic meanings of

such verbs as being on a par, which makes the verbs aspectually polysemous ;

for example, the mental verbs ‘ see ’ or ‘ hear ’ can indicate either a continuous

or an inchoative perceptive relationship between the experiencer and the

stimulus (‘ to become aware of something by sensing it ’ vs. ‘ to continuously

perceive something by a sense ’). On the other hand, for transitive-locative

verbs such as ‘ cover ’ (16) or ‘ fill ’ (17) the primary reading is clearly the

dynamic change-of-state one. The static reading seen in (16) and (17) is thus

secondary and arises only in particular contexts, especially in sentences

where the subject refers to an inanimate, static entity. The explanation based

on fictive dynamicity thus assumes that these static uses are motivated by a

T H E F I N N I S H O B J E C T

103

conceptualization involving a fictive change ; accordingly, the total object of

such examples reflects the aspectual nature of the

FICTIVE

accomplishment.

This analysis is supported by the fact that, in Finnish, canonical fictive

motion can also be expressed by transitive verbs such as ylitta¨a¨ ‘ cross ’, and

in this case the total object is also used, as shown in (18).

(18)

Tie

ylitta¨-a¨

autiomaa-n.

road cross-

PRS

.3

SG

desert-

TOT

‘ The road crosses the desert. ’

Example (18) is semantically transparent and supports the fictive dynamicity

analysis for the whole QR pattern. In (18), the fictive motion of crossing the

desert is construed as completed (i.e. the road covers the whole distance from

one side of the desert to the other), and this is what motivates the total

object – note that the overall unboundedness of the actual (static) referent

situation would be expected to trigger the partitive marking. If we compare

(18) with a similar example indicating true objective motion (19), we see that

in (19) the case opposition in the object marking works normally with the

same verb ylitta¨a¨ ‘ cross ’ : the partitive indicates progressive aspect and the

total object the completion of the event.

(19)

Bussi ylitt-i

autiomaa-ta

y autiomaa-n.

bus

cross-

PST

.3

SG

desert-

PAR

desert-

TOT

‘ The bus was crossing the desert. ’ [

PAR

]

y ‘The bus crossed the desert.’ [

TOT

]

A comparison with (19) suggests that the total object is used in (18) because

the fictive crossing of the desert by the road is conceptualized as similar to

the completed crossing of the desert by the bus in (19). The partitive object

would not be natural in (18), but if used, it would have to indicate a pro-

gressive meaning of actual, ongoing motion along the road (as in The road

was just crossing the desert when it started to rain). In the same way as in the

habitual type, the partitive is thus unable to indicate the unbounded nature

of the overall static situation.

As already noted, Finnish object markers clearly differ in this respect from

aspect markers of certain other languages, where attention is focused on the

overall (unbounded) nature of situations like that in (18). For instance,

Spanish transitive verbs that indicate fictive motion in a manner similar to

(18) take the imperfective past tense form, which reflects the conceptualiza-

tion of the situation as unbounded ; consider (20).

(20)

Esta vı´a

cruza-ba

la

ciudad de

este a oeste.

this road cross-

IPFV

.3

SG ART

city

from east to west

‘ This road crossed the city from East to West. ’

(Internet)

The imperfective form cruzaba ‘ crossed ’ in (20) reflects the unboundedness

of the situation and differs dramatically from the Finnish object markers that

T U O M A S H U U M O

104

focus on the

INTERNAL

aspectual nature of the fictive motion – i.e. whether

the fictive motion along the desert is completed or not.

The following example demonstrates that the meaning opposition observed

in (19) is also present in locative QR examples. In (17) the verb ta¨ytta¨a¨ ‘ fill ’

was used to designate the static situation where the bath is full of water,

whereas in (21) it indicates actual change, where the bath is being filled with

water by someone. Again, the opposition between the object markers works

normally in (21) : the partitive indicates progressivity and the total object

conveys completeness of the event. The opposition between fictive dynamic-

ity and an actual change is thus displayed here in the same way as in (18)

vs. (19).

(21)

A

¨ iti

ta¨ytta¨-a¨

ammee-n

y ammet-ta.

mother fill-

PRS

.3

SG

tub-

TOT

tub-

PAR

‘ Mother fills (will fill) the tub. ’ [

TOT

]

y ‘Mother is filling the tub.’ [

PAR

]

If the explanation that the object marking in QR sentences is based on

fictive dynamicity is correct, then the motivation for the total object in QR

examples resembles that proposed above for habitual examples, except for

the fact that the accomplishment motivating the total object is iterated in

habitual examples but only fictive in the QR type. In the same way as in

habituals, this fictive accomplishment is then ‘ stretched ’ over time, only this

time the temporal dimension is not based on iteration. I will return to the QR

type in section 5, after treating certain other problematic uses of the object

markers in unbounded sentences. In sections 3.2 and 3.3 I will discuss

the hitherto unexplained uses where the total object is motivated by a con-

tinuously closed quantity or a continuously bounded aspect (continuous

completives).

3.2 Transient vs. overall quantification

The literature on Finnish object marking has mentioned certain apparently

habitual examples (including a total object) that under closer scrutiny turn

out to be problematic for the explanation provided above for habituals.