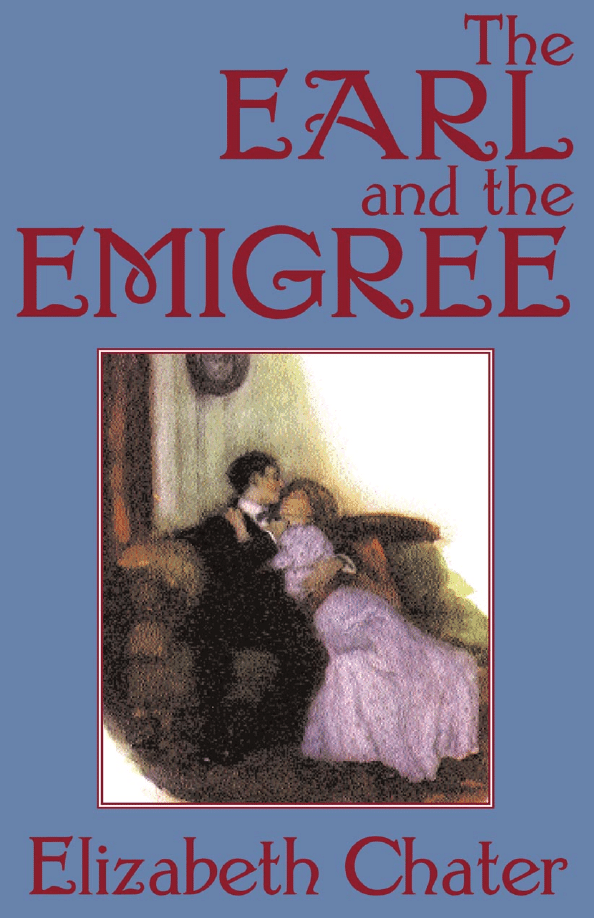

The Earl

and the

Émigrée

The Earl

and the

Émigrée

Elizabeth Chater

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy,

recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without

explicit permission in writing from the Author.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents

are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any

resemblance to actual events or locals or persons, living or dead, is

entirely coincidental.

© Copyright 1985 by Elizabeth Chater

First e-reads publication 1999

www.e-reads.com

ISBN 0-7592-2245-2

Other works by Elizabeth Chater

also available in e-reads editions

The Marriage Mart

The Gamester

Milord's Liegewoman

Angela

The King's Doll

The Runaway Debutante

Milady Hot-at-hand

Lady Dearborn's Debut

A Place For Alfreda

The Duke's Dilemma

A Time To Love

A Delicate Situation

The Earl

and the

Émigrée

1

D

ibble, butler to the Right Honorable Earl of Stone and Hamer,

strode impatiently toward the massive front doors of Milord’s great

London townhouse. He was more than a little annoyed as he

swung back one panel of the door in response to the peremptory

battering of the knocker. At this hour—dusk of a cold, rainy afternoon in

March—the third footman, a gauche but earnest youth, should properly have

been in attendance in Milord’s great hallway, ready to receive or discourage

any visitor ill-advised enough to brave the wretched weather at such an

unfashionable hour. But the third footman, Batty by name, had reported to his

superior with an inflammation of the nose and throat so obviously putrid that

Dibble waved him away to the servants’ quarters before he infected his elders

and betters.

Dibble had, perforce, to man the door himself until Batty could send down

the second or even the fourth footman, both of whom were enjoying their

regular four-hour respite. The Earl, Dibble decided grimly, was far too lenient

with his staff. Four hours free per diem, for every member of the staff of the

townhouse! Unheard of! And all to be arranged, of course, by Dibble! The

timekeeping alone imposed another burden upon an already heavily laden

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

1

Majordomo, Dibble grumbled, and resolved to give the importunate upstart

who was belaboring the door knocker what for, and send him off with a flea in

his ear!

But when he swung the huge portal open, his mouth followed suit. The

disturber of the peace of the Earl of Stone and Hamer was a slight, unimpres-

sive figure just over five feet tall, draped theatrically in a black, hooded cloak

far too long for it. Dibble eyed the mud-splattered garment with extreme

repugnance. He was struck in the face by a gust of icy-cold rain, and his exac-

erbated temper flared.

“Wot d’ye think yer playin’ at?” he growled in plebeian accents his master had

never heard from his pursed lips. “Get t’ell ahta ‘ere before I shifts yer ballast!”

As he began to shut the door, the bedraggled creature dared to address

him. In a voice whose odd yet cultured accent startled him, the creature

announced, “I am the émigrée whom Milord is expecting. You may lead me to

him, if you please!”

The name, which sounded like Amy Gray, gave Dibble pause, but only

momentarily. It was quite unthinkable that His Lordship should have sched-

uled an appointment with any person so obviously not of the ton. Dibble

peered over the intruder’s shoulder—not a difficult feat—to check that no

great carriage waited for the visitor. The street was empty, soaking wet, and

miserably cold. With a feeling that banishment to such an icy hell was no

more than the intruder’s due, Dibble prepared to shut the door. To his sur-

prise, the creature thrust its way past him in one decisive, writhing movement,

and turned to face him in the huge, warm, well-lighted hallway. Placing a

small basket upon the white-and-black marble tiled floor, the bedraggled lit-

tle figure thrust back the shrouding hood, revealing a dirty, female face with

masses of matted hair and a pair of huge amber eyes that blazed at the butler

like molten gold.

“You would deny me entrance?” snapped the intruder, with impeccable

English faintly accented, and very evident anger. “You will take me at once to

your master, sirrah! I have not come this far to be put off by the impertinence

of a servant!”

“Indeed?” A cold voice sounded from somewhere above the heads of the

antagonists. “Perhaps you will deign to tell me what it is you have come to do?”

Down the massive carpeted stairway advanced the imposing figure of Lord

Alexander Christopher Deeth Stone, twelfth Earl of Stone and Hamer. In the

light of the thousand candles he was an impressive figure indeed, and the pre-

sumptuous intruder drew a breath and stared at his magnificence for a

moment without answering his question. He was a big man, well over six feet

and broad in proportion. Light gleamed from the pristine white of his freshly

powdered wig, and glinted from the cold silver of his remarkable eyes, fringed

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

2

round with black lashes and accented by heavy black eyebrows. His costume

was a quelling black brocade, cut formally, and relieved only by a white silk

waistcoat and knee breeches above silk stockings and black, silver-buckled

shoes. A single fob hung from his waist, and a heavy crested ring was the only

adornment upon the white hands. As he waited for a reply, one black eyebrow

arrogantly raised, the Earl took out a white handkerchief and touched it to his

lips. A pleasant scent of spice wafted to the nostrils of the two standing in the

hall below him.

At this moment, the butler’s nose wrinkled. In the warm air of the great

hallway there was beginning to be apparent a most unexpected odor. The bas-

ket that the cloaked female figure had placed upon the floor had a divided lid,

the two flaps of which began to move disconcertingly. It was from this basket

that the unpleasant odor seemed to be emanating.

“Milord, there is something alive within the basket,” began the butler,

moving toward it and stretching out a hand.

“You will open that basket at your own risk,” advised the female in a tone

of considerable anticipation. “I have a ferret in it. Jille is not happy with her

present situation!” She then had the effrontery to laugh. Dibble stared at the

ragamuffin with acute distaste. Then he turned to his master. “Milord, shall I

call a footman to evict this creature?” he asked humbly.

“I am surprised that you permitted it to enter the house,” said the Earl

repressively.

At once the golden eyes were ablaze. “I have done you and your house a

signal service, at great hazard to my own life and purpose,” came the cultured

and charming voice in purest Parisian French. “I had considered your dignity,

sir”—the lack of title emphasized her scorn as she continued in impeccable

English. “However, since you refuse to permit me the courtesy of a private

hearing, I shall tell you, in front of your servant, that I am returning two things

which belonged to Your Lordship’s brother!”

At this remark, a sudden glacial chill seemed to strike the men. Dibble’s

ample form froze in an attitude of acute embarrassment; only his eyes moved,

under lowered brows, to see how his master was taking this home thrust. The

Earl’s large figure merely stiffened slightly, and his black lashes concealed for a

moment those silver-cold eyes.

After a minute he said softly, “Perhaps we should adjourn to the library,

Mademoiselle. Dibble, see that I am not disturbed.”

The butler bowed, happy to have escaped a severe reprimand for permit-

ting the little French troublemaker to enter the hallowed precincts of Stone

House. The other two went down the huge hallway, past several inset doors

under heavily carved lintels. The girl, following the Earl, paused to regard

these appreciatively.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

3

“Rather fine,” she conceded.

Milord, glancing back over his shoulder, raised his eyebrows.

When they were both inside the well-lighted library, the Earl strode over

to stand in front of a glowing fire. As he faced his uninvited guest, he said, in

a voice from which all warmth had departed, “What is this you bring me?”

The girl placed her malodorous basket on a small side table, and cooed, in

a tone so seductively sweet as to raise Milord’s eyebrows a second time,

“Come, ma petite Jille, good little mother, let Cozette take from under you that

uncomfortable object which has so disturbed your rest!” Fishing in some hid-

den pocket, she brought out a scrap of meat and, opening one half of the

divided lid, offered the tidbit to the long narrow head that was tentatively

poking, snakelike, from the depths of the basket. While her pet consumed her

treat, Cozette put her hand into the dark interior, lifted up a piece of worn,

tatty fur, and drew out a rag bundle from the bottom of the basket. This she

tendered rather haughtily to Milord.

That nobleman found a quizzing glass in one coat pocket, and raised it to

inspect the dubious bundle coolly.

“Take it!” snapped the disrespectful child.

Milord did so and, laying it upon the top of a leather-covered desk, prod-

ded it open gingerly with a pen and the shaft of the quizzing glass. And then

suddenly there was a glorious shimmer of light, and from the dirty rag Milord

drew forth a diamond necklace of such purity and magnificence that even

Cozette’s eyes widened, and she forgot to give the ferret its next bit of meat.

Milord bent over the necklace with the first trace of interest Cozette had

observed on his countenance. “My mother’s necklace,” he breathed. Then,

looking sternly into her face, he said, “Where did you get it?”

Cozette started, not because of his tone, but because Jille, impatient for

her supper, had gently nipped her finger. Hastily passing out the next small

bit of meat, Cozette explained, “Your brother took it when he ran away with

the daughter of the French ambassador.” She frowned. “I had thought you

knew of this?”

The Earl said noncommittally, “We missed it after he had gone, but we

hesitated to connect him to . . . the theft.”

Cozette frowned at the pale, arrogant face. Then, shrugging, she contin-

ued, “Did you know that Charmaine’s Papa forbade her to marry your brother,

and, in fact, disowned her? They were much in love, however, and set up

housekeeping in a cozy attic in Paris. Your brother worked as a translator, and

taught English to anyone who could pay his fees.”

The Earl cocked his head arrogantly. “So Neville had something worth

selling,” he commented. “My father and I wondered how he would manage to

provide for himself. To say nothing of the little French baggage—”

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

4

“I think that is not very convenable of you, to speak so of any lady, but espe-

cially of your brother’s wife,” said Cozette severely.

“Wife?” The Earl’s black eyebrows rose in sardonic disbelief.

“Oh, yes, they married. Some poor priest evidently thought it better that

they marry than burn—as Saint Paul told the Corinthians.”

A glint of what might have been laughter flashed for a moment in the cold

gray eyes. “So they married? And now they are sending back the necklace?

Well, what do they want to buy with it?”

Cozette’s expression became closed and guarded. “They are not offering

to bargain,” she said tersely. “They are dead, both of them. They were

caught up in the street into a mob fleeing from the King’s soldiers. Both

were killed under the mistaken impression that they were part of the mob of

revolutionaries.” She eyed him somberly. “Fortunately, their son was not

with them that day.”

“Their son?” snapped the Earl. “Are you trying to foist some gutter-bred brat

off on me as my brother’s son?”

“I am not going to foist anyone or anything on you,” Cozette snapped

back. “I notice, however, that you displayed little of this reluctance in

acknowledging the ownership of the diamond necklace, accepting it as your

own.” She patted the ferret’s head, put it gently back into the basket, and

turned to leave the library.

“Wait!” said the Earl coldly. “I have not given you permission to go.”

The small dirty face tilted up to his with as much arrogance as his own. “I

am not, thank le bon Dieu, under any compulsion to obey you,” she said haugh-

tily. “You are a monster, cold and unbending, and insensitive as all the English!

I would not permit le pauvre petit Alexandre to come to you now if you begged

me! You would freeze le bébé with your hauteur du diable!”

“Did Neville name the boy after me?” said the Earl, his icy demeanor

momentarily dissolving into interest and something more.

“How should I know whether they named the poor child after so bitter

and unloving an uncle?” sniffed the small, grimy female. “In any case, I do not

think I shall give him to you and your pompous Dribble.”

“Dibble,” corrected the Earl absently. He was evidently uncertain of the

good faith of this very articulate urchin. The girl shrugged and turned again

to the door. A hand on her shoulder swung her around abruptly. The Earl,

with more animation than she had yet seen on his face, was glaring down at

her from his superior height.

“Where is my nephew?” he demanded. When she did not answer at once,

he shook her roughly. “I intend to have him in this house tonight if he is hid-

den anywhere in London,” he warned the girl. “You will harm only yourself by

defying me! Unless—Is it money you want for bringing him to me?”

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

5

Cozette shook his hand from her shoulder. Her small face was aflame with

rage. “Money? You would ask such an insulting question of me? I have brought

that poor child out of a France gone mad, disrupted by civil war! We have

hidden, and slept in barns, and once even a pig sty! We have never had food

enough to satisfy hunger! Had it not been for Jille, that well-trained and lov-

ing friend, we should surely have starved! She caught the rabbits and—and

other small game that kept body and soul together during those terrible weeks

when I struggled to bring your nephew to the safety and comfort—as I

thought!—of his father’s home! And your wretched baubles! Poor Jille had to

rest upon them in the bottom of her bed, lest some sans culotte should find

them and take them from me! And now you have the . . . effrontery to suggest

that I did this for money!”

The Earl took her arm, this time less roughly. “I beg your pardon,

Mademoiselle,” he said. The girl could not read any real warmth or, indeed,

regret at his callous behavior, into that apology. “You must admit that you

have given me surprising news—shocking information! I will ask you now

where my nephew is. When we have him safe in his father’s home, there will

be time for discussion and . . . appreciation.”

Narrow-eyed, the girl glared at the imposing figure so close to her. “I do

not trust you, Milor’, and I only hope that poor infant will be treated tenderly

in this cold, dark mansion! From what I have seen of you and other of the

English, you are a race of heartless monsters.”

“At least we have not threatened to kill our King,” said the Earl sternly.

But the chit had an answer. “Not this one, at least!” she riposted. “I believe

that your Charles the First was beheaded, was he not?”

The Earl glared his dislike at this presumptuous little ragamuffin. Very few

of his male acquaintances and none of his female friends would have cared to

tempt his disapproval by correcting him so summarily. He set his teeth and

gritted out, “Where is the child—if you please?”

Sniffing her disdain, the girl led the way out into the hall. “He is outside,

hiding in your shrubbery. I dared not bring him in until I was sure your

household was suitable to receive him. And I am not yet convinced of it,” she

added darkly.

“This house will be suitable,” snarled the Earl. “At least we shall not have

to depend upon a ferret to feed him.”

“It is obvious,” said the maddening little female, “that you have never had

to escape from a country torn by civil dissent!”

Setting his jaw against reprisals, the Earl followed the girl outside his

imposing front doors, attended at a safe distance by Dibble and the two foot-

men he had summoned. The girl went at once to a rather handsome clump of

shrubbery that served to mask the front windows from the gaze of the com-

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

6

mon folk who might have business upon the street. There, with a coaxing,

gentle tone the Earl remembered from her conversation with the ferret,

Cozette wheedled forth a very small, weary, and exceedingly dirty little boy.

When he would have staggered getting out of the bushes, the Earl was beside

him instantly, and caught him up into his arms. The boy did not cry out, only

stared hard up into the face looming above him in the dusk.

“He is made of good stuff,” exulted the Earl, who would not have been sur-

prised to have a screaming, writhing child in his arms. Quickly, he took the

boy inside.

The girl followed, and when Dibble would have shut the door in her face,

she sailed through it with all the airs and grace of a duchess. In fact, she

caught up with the Earl as he was about to take the boy into the library.

“He needs food first, then a bath and a clean bed,” she said firmly. “This is

neither the time nor the place for questions and . . . intimidation.”

The Earl found himself, for the first time in his adult life, glaring at

another human being. “I did not intend to intimidate the boy,” he said, between

his teeth.

“Perhaps,” the infuriating female said patronizingly, “you are not aware

of how—formidable,” lapsing into French, “your manner is?” She shuddered

too elaborately.

Risking a glance down at the small boy he held in his arms, the Earl was

first surprised and then delighted to catch a knowing little twinkle of laughter

in those wide blue eyes so much like Neville’s. His breath caught in his throat.

Nev had always been a merry little fellow, amused by the weight of their fam-

ily’s consequence rather than impressed by it. It had been, in their father’s

stern opinion, a fault in him that must be rigorously rooted out. Perhaps,

thought the Earl in a rare flash of insight, it had been that constant harrying

that had finally driven the gentle, laughing boy to run off with the charming

little Frenchwoman. So this was Nev’s son!

“Parles-toi l’anglais?” he murmured.

The child’s smile flashed—Neville’s smile! “Coco has made very sure I

speak Papa’s language with an accent of high tone,” he said in impeccable

English.

“And who might Coco be?” murmured the Earl.

Alexandre’s glance sought out the girl’s rumpled, dirty figure. He pointed,

his own small finger grubby. “Cozette de Nullepart,” he explained with his

endearing grin. “It means Cozette of Nowhere.”

The Earl’s elevated eyebrows emphasized his opinion of that designation.

Huge amber eyes challenged his judgment.

“It was better to teach him to say that, when we were stopped and ques-

tioned,” she explained quietly.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

7

The Earl felt a frisson over his skin, the merest touch of emotion, as he

considered the plight of a small girl and child being stopped by soldiers or

ruthless members of the mob or even wandering rogues preying on the devas-

tated countryside. She seemed to catch his feeling of unease.

“When they became too brutal, I escaped or diverted their attention by

appearing to hear other members of my nonexistent group approaching.”

She was smiling slightly, but the Earl could see the bleak memory of fear

in those amazing eyes. “Eh bien! Let us get young Lex some food, Milord!”

she suggested.

Wordlessly, the Earl moved out into the hall.

“Where do you take us?” questioned Cozette.

“To the dining room, of course,” the Earl answered over his shoulder

impatiently.

“But no! This is absurd!” As the girl uttered the unseemly contradiction of

His Lordship’s statement, Dibble was heard to utter an obvious gasp. No one in

the household ever contradicted the Earl. It was unthinkable! Yet this grubby

little female with her ridiculously top-lofty ways had just done so. Even worse,

she had turned and handed the foul-smelling basket to Dibble, and was taking

the child from Milord’s arms in a most peremptory fashion.

“We had much better eat in your kitchen,” she said firmly. “We are both

too dirty to eat in a civilized dining room.”

Dibble, horrified at the burden he had been forced into accepting, stared

at his master in agonized indecision. The Earl was looking at the determined

female with a quizzical glance Dibble had never seen upon that hard, hand-

some countenance.

“Dibble, you may lead us to the kitchen,” he said. “And then get rid of that

malodorous basket before Chef Pierre leaves us in a Gallic huff.” And he

grinned at the girl.

“Jille will be fairly comfortable in your stables if we feed her very well.

Then tomorrow I shall see about a room somewhere for myself, with a land-

lord who will not mind a ferret in residence.”

Even Dibble was forced to grin at this naiveté. Neither of the men made a

reply, however, leaving the chit in blissful ignorance of the absurdity of her

expectations. The small procession moved to the kitchen, whence, thanks be,

Pierre had already departed to his own rooms, and the kitchen maids and

boys were busily cleaning up. To say that they were surprised at the sudden

appearance of their master and his unusual guests is an understatement. In

fact, one boy had to be sharply nudged by the senior maid before he would

close his gaping mouth.

Cozette took charge with a calm air of authority that had the Earl’s brows

elevating over sharp silver eyes.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

8

“Some warm food for the little one, if you please,” she asked pleasantly.

“That soup which is simmering on the back of the stove, perhaps, and a piece

of bread, buttered? I shall have the same. And you, my friend,” she addressed

the gaping boy, “will you get me some meat for Jille? She is a very useful ferret

who has kept us alive during our flight from France.”

Neatly done, thought the Earl. She’s told them enough to satisfy their

most urgent curiosity, and possibly win their sympathy. Although none of

them had ever taken orders from such a ramshackle miss, they did her bidding

with a willingness that surprised His Lordship and quite obviously amazed the

butler. He had lost no time in surrendering the basket to the kitchen boy, and

was now glaring as the latter cut up a nice piece of raw beef into small bits and

offered them to the bright-eyed, alert, but friendly animal.

The soup was presented in two bowls, and a platter heaped with crusty

bread lavishly buttered joined it on the servants’ table. It looked and smelled

so delicious that the Earl asked the senior kitchen maid for another bowl for

himself, and sat down beside his guests, to the affronted disapproval of

Dibble. The girl, who had used the time of serving up the meal to wash her

own hands and face and the child’s, shot a glinting look at Milord, inviting

him to share her amusement at the pompous servant. The Earl did not smile—

she wondered briefly what a smile would do to that cold, handsome counte-

nance—but at least his face lost the stern chill that had seemed habitual to it.

The soup was filling and tasty, and all three diners enjoyed a second bowl-

ful. The bread, too, seemed to disappear like magic. Toward the end of the

informal meal, young Lex’s head began to droop and his eyelids to flutter. The

girl observed these signs with satisfaction.

“He will be asleep before I finish bathing him,” she said quietly. “Will you

have someone show us to a room, Milord?”

“I shall myself conduct you and my nephew upstairs,” said the Earl.

“Dibble, have someone prepare my brother’s old room for his son.” He

glanced around the ring of staring, wondering faces. “This lady has brought

Mr. Neville’s son from France at great danger and pains to herself,” he said in a

low voice. “The child’s parents were victims of a mob. He will be staying with

me now.” He turned and led the way out of the kitchen and toward the front

of the house. Cozette came after him, carrying the drowsy child.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

9

2

C

ozette surveyed the spacious, handsomely decorated room with

approval. A maid was kneeling in front of the grate, fanning a good

fire into warmth and light. Another maid was going from one mas-

sive candelabrum to another, touching them alight with a taper.

Two more maids were just entering the chamber with brass hot water cans,

while Dibble himself was pulling a bathing tub in front of the fire.

“This is well done, Milord,” she commented to her involuntary host. “Your

servants are well trained and willing.”

The Earl’s hard lips twisted. “A good deal of the willingness may be simple

curiosity,” he murmured. “The arrival at Stone House of an unknown nephew

is an earthshaking event.”

Cozette was stripping the filthy rags off the child. “Some cold water,

please,” she requested of Dibble. “I would not wish the boy to be scalded like

a lobster!” Her bright smile held such sweetness that the butler obeyed her

without reluctance.

The Earl, watching this exchange with a sardonic eye, made a mental res-

olution that this grimy little witch should not work her wiles upon him. There

would be a reckoning, and very soon, but at least he would permit her to

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

10

clean the boy and make him comfortable first. A suitable governess would be

found in the morning, and this female paid off and sent about her own busi-

ness—accompanied by her familiar, the ferret Jille. This categorization of the

girl as a witch so amused His Lordship that a small smile tugged at his lips.

Dibble, straightening up from dumping a large pitcher of cold water into the

tub, caught sight of the abortive smile and wondered whatever had come over

His Lordship. Levity in such a situation, he would have thought, was the last

thing the Earl would be displaying! Dibble could not recall having seen his

master smile once in all the years he had worked for the family. The butler

shook his head. The sooner this odd little madam could be removed from

Stone House, the better it would be for all concerned.

At this moment, Cozette took off her long, concealing cloak in order to

kneel by the tub and wash the sleepy child. Dibble’s gasp was echoed by

nearly every person in the room. Under the filthy garment was a dress of

pale gold silk, also stained and dusty, and hacked off well above the ankles

to show a number of full petticoats, also cut short. It revealed a figure that

had the Earl narrowing his cold gray eyes. He stared more closely at the

face half hidden by the dirty masses of hair. Then he strode over to the

kneeling girl.

“You have disguised yourself to make your escape easier, have you not?” he

demanded. “I shall have your real name, Mademoiselle, not the nonsense you

have taught my nephew to call you!”

“Cozette is only a—how do you say?—love name my father used for me.”

She turned a weary, smiling countenance up to his. “I am Ma’am’selle Michelle

deLorme, daughter of Professor Henri deLorme, tutor to the children of noble

houses. Your brother’s wife, Charmaine, had been a pupil of my Papa’s, and

brought your brother to us to discover if we might find work for him. Papa

was delighted to help so charming and courteous an Englishman.” This last

phrase was accompanied by a minatory look that made evident Cozette’s

opinion of Neville’s brother. “Papa was able to find him work teaching English

to the sons of minor nobility who were hoping to travel to England or Canada

for refuge.” She sighed and leaned wearily against the high tub. Then, pulling

the sleepy Lex to his feet in the tub, she endeavored to drape one of the large

towels about him.

With an exclamation of mingled disgust and alarm, the Earl stepped for-

ward and took the boy, towel and all, into his own strong grasp. He carried

the boy over to the bed and placed him on it. “Tuck him in,” he commanded,

and gestured the servants out of the room.

Silently, Cozette dried the child and pulled the clean, lavender-scented

covers over him. As she straightened up from the task, she staggered slightly.

Before she could recover herself, two strong arms were about her own person,

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

11

and she was clasped close to a massive body. Too tired to struggle, she merely

turned her head and stared warily up into Milord’s face.

“Shall I take care of you, now, as you did of my nephew?” the Earl mur-

mured, his eyes on the white breasts that threatened to swell out of the once-

fashionable garment. He carried her over to the tub and set her on her feet

beside it. With her last bit of strength, Cozette pushed him away.

“Milord!” she said. “I had not expected to find such treatment in an English

nobleman’s home!”

“But we are all heartless monsters; cold, unbending, and insensitive, I

believe you named us,” taunted His Lordship. “Surely you do not expect gentle

treatment from me? I think I should enjoy bathing that grimy little body—”

From somewhere within her weary body the girl drew enough strength to

stand erect and face him with defiance. And then she smiled with such sweet-

ness that the Earl felt his heart beat painfully in his chest.

“You make the joke with me! Just like your brother Neville—always il fait le

farceur! Eh bien! Where would you have me rest tonight, Monsieur le Comte?

Might it not be well for me to remain here near the little one, lest he wake in

the night and be afraid?”

The Earl regarded her with respect. Knowingly or not, she had success-

fully put an end to his lecherous intentions, reminding him clearly of the debt

he owed her for her care of his nephew and his family jewels. He stood back

with a slight bow.

“Bien entendu, Ma’am’selle deLorme! You have won this round with the insen-

sitive Englishman. Sleep well, for tomorrow we shall have a reckoning! To

determine your reward for your services to my House,” he explained, at her

puzzled, apprehensive look.

“To see le bébé resting so sweetly is reward enough, Milord,” the girl said softly.

The Earl bowed again and left the bedroom.

Cozette frowned, sighed, and then began to divest herself of her stained

garments, her eyes on the water in the tub, and especially on a cake of laven-

der soap that rested in a dish beside it. In a minute she had slipped her

exhausted body into the still-warm comfort of the bath, and was scrubbing

away blissfully. She noted that there was another brass pot of warm water at

hand, which would do nicely to wash the sticky dirt from her hair. It had been

a wise plan to make herself look dirty and unattractive, but for some reason

she did not wish to consider too deeply, it now seemed equally important that

she present the best appearance of which she was capable when she met the

Earl in the morning.

She got out of the tub and began to dry herself with the big towels warm-

ing before the fire. Her glance fell upon the heap of dirty clothing she had so

thankfully discarded. With a sharp thurst of panic she ran over and delved

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

12

among the grimy petticoats for the two small, flat packages she had worn next

to her skin since the night she had left her father’s house. With relief, she

found them. One of the packets contained the record of a marriage between

Neville Stone and Charmaine de la Valeur, while a second document testified

to the birth of a son, Alexandre Julien Stone, a year later. These official docu-

ments were necessary, Papa had said, to prove little Lex’s birthright. Papa had

warned her to keep them safe until she could deliver them, with the boy, to

his father’s people.

Cozette placed that package, unopened, on the table by the bed. She

would sleep here with the child tonight, so it would be safe to leave the

documents there beside her. The experiences of the last few weeks had been

so terrifying that she had trained herself to stay alert and waken at the

slightest sound.

The other packet was of quite a different nature. The girl stood with it

clutched in both hands, her eyes searching the room for a hiding place. She

dared not lock the door. Such an act would draw unwelcome attention, even

arouse curiosity. She had no nightrobe under which to hide the letter, and she

could not bear to put on her clean body the filthy garments she had worn for

weeks. Yet she dared not leave the second package on the table. It was too

important, too dangerous to be exposed to the risk of idle or hostile scrutiny.

Under the pillow? No, for Lex might waken early, discover it, and open it

in childish curiosity. Reluctantly, at length she took up the clothing she had

discarded so eagerly, and flicked through it until she found the strip of mater-

ial that had served as a pouch to bind the packets to her body. She put it on

again and secured the second packet. Then she donned the cleanest of the

petticoats and climbed wearily into bed beside the sleeping child.

Cozette’s awakening was sheer delight. The bed had been comfort itself:

goose-down mattress, lavender-scented sheets, a soft woolen comforter—and

all so clean! After her nights in haymows, barns, and even in rough brush

under the stars, such soft, clean comfort was a matter for rejoicing. And then

to waken to see Lex’s dear little face smiling down into hers, and feel his hands

patting her gently to rouse her from slumber! She did not think to scan the

room, so lulled was she in the drowsy security of the bedroom.

She gurgled a laugh as she caught the little child close to her breast—

remembering too late that she had slipped into bed almost naked, with just

one petticoat to conceal the packet. Her involuntary gesture of rejection had

brought a puzzled look into Lex’s face. The girl hastened to reassure him.

“Coco puts you away, mon brave, because she has no clothes to wear.”

“You are cold?” asked the child. “See, someone has given me a robe!

Perhaps mon oncle? I like it very much.” He displayed a dressing gown of bright

wool, belted around his small figure. “Shall I look to see if mon oncle has given

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

13

you a robe also?” His sparkling blue eyes went beyond Cozette’s bare, gleam-

ing shoulder.

“I have it here,” a deep voice sounded from the other side of the room.

The Earl advanced toward the bed, carrying a négligée of amber velvet and

lace. The girl gave an involuntary cry of pleasure, and then withdrew hastily

under the covers.

“A thousand thanks, Monseigneur!” she stammered. “If you will go away

until I have donned it . . .?”

“Now why,” asked the Earl, “should I do anything as foolish as that?” He

favored her with a wide and wolfish smile, a predatory smile that had nothing

of humor in it.

For this effrontery he was treated to a flash of golden fire from Cozette’s

fine eyes. He regarded her with an insolent gaze.

“One hears,” he drawled meditatively, “of the, ah, flexibility of behavior

among the beautiful habituées of King Louis’s court. Can it be that rumor lies?

One would think not.”

“I do not care what you or rumor—an unreliable intelligencer!—says about

the habituées of the Court! For my part, I never was such an one. The daughters

of tutors, however gently born, are not usually invited into the Royal Circle!

In any case, my behavior is not, and never has been, what you are pleased,

with that hateful arrogance, to call flexible! Now will you please go away and let me

get some clothes on?” the girl ended, with a cry that was almost a wail.

For the first time, Cozette heard the Earl laugh. He threw back his head

and gave a shout of mirth that softened his austere and forbidding counte-

nance into attractive warmth. She caught her breath at the powerful attraction

that radiated from the big man. He was dressed for riding, and the hard, virile

appeal of him was very evident. He regarded her closely, eyes glinting with

mischief, then gave a pseudo-disappointed sigh.

“If I must, I must! One would not wish to alarm little Lex!” The two males

shared a grin as the Earl swept a mocking bow. “Cover yourself with the nég-

ligée, Ma’am’selle! Your breakfast will be brought to you shortly. You may eat it

in this room. Later this morning, we will have our conference.” This last was

said in a colder tone from which all trace of amusement had gone.

Cozette shivered involuntarily. “Monseigneur! Am I to go to this confer-

ence dressed en négligée?”

“You would prefer a less formal costume?” His wicked glance probed sug-

gestively at her body.

“Mon Dieu!” breathed Cozette. “Are all Englishmen sex-mad? The half was

not told me!”

Again, involuntarily, the Earl laughed. “I have ordered a dressmaker to

attend you here in one hour. She will bring costumes from which you may

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

14

make a choice. I cannot have you running tame in my house in your present

get-up,” he taunted. “I have had your, ah, traveling costume burned,” he

added casually.

While agreeing heartily with this decision, Cozette was reminded of the

packet she had formerly worn under that grimy costume, and glanced hur-

riedly at the bedside table where she had left it. The documents were gone!

How could she prove Alexandre’s identity now? Her glance flew to the Earl. He was

dangling the packet from his fingertips.

“I saw these when I entered the room,” he offered with unforgivable

complacence.

Cozette shrugged. They were, after all, his nephew’s documents. She

would have given them to him this morning in any case. “They are for you,”

she said agreeably, and ventured a smile.

For some reason, this easy acquiescence put him in a better humor. With a

final lazy glance over as much of the girl as could be discerned under the covers,

he extended his free hand to the boy. “Come, Lex, we must permit our Coco to

dress herself. Are you hungry, mon vieux? I waited to have breakfast with you.”

Lex took the proffered hand eagerly and walked out of the room chatting

happily to his new-found uncle. Cozette realized with a twinge of sadness

that he had missed a man’s presence in his small world; no matter how dearly

he had come to regard her, she was no true relative, and would soon be

replaced in his affections by some woman of the Earl’s choosing. Better so,

perhaps. The sooner the boy could forget those frantic, desperate weeks of

running and hiding, the better for him. She must always be associated in his

mind with those dreadful days. Here in this England he would have a life

more secure, both as to safety and wealth, than his young parents had ever

been able to provide. And she would be free very soon to carry out the dan-

gerous and difficult part of her mission.

The girl drew a deep breath as she rose and slipped into the lovely gar-

ment the Earl had provided. Had it been worn by some woman of his house?

It seemed new. Had he sent out to get it very early this morning? He puzzled

her, this arrogant, beautiful nobleman in his somber black elegance and frigid

attitude. So coldly critical, yet he had shouted with laughter twice, like a boy.

So rigidly correct in form, yet he had behaved and spoken with shocking sen-

suality upon occasion. A riddle! She had better depart quickly, Cozette

warned herself, lest she become too attracted to the virile intimidating master

of this mansion.

She could leave very soon, she realized, and complete her other mission in

this country. Lex was safe. He would soon be willing to do without her. The

thought pained her warm heart. Still, it would be much better to go. She

feared the Earl, and what he might discover. She had no way of knowing

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

15

where his sympathies might lie. True, she had made him laugh twice, she

reminded herself. And that laughter had changed and softened his harsh

beauty remarkably. Perhaps he needed someone to challenge his authority, to

infuriate and amuse him? Cozette sighed. Do not spin impossible dreams, she

advised herself practically. You have your urgent task, and after that is completed, your

own way to make. The sooner you can get the packet delivered and find work, the better for

you, my girl! A lavish breakfast gave support to this mood.

When she was dressed, she found a pair of bedroom slippers that were a

shade too large, but comfortable and warm. Then she explored the rather

masculine-looking dressing table in the adjoining room, where a cot had

already been set up for her use. She found also, brushes, combs, and even a

small flacon of perfume waiting for her! What a joy to touch delicate scent to

her wrists and throat, to run the comb gently through hair deliberately mat-

ted and unkempt to aid her disguise! She was brushing the heavy silken length

of it in a sort of lazy euphoria when she heard a knock on the bedroom door.

Going through quickly, she called out, “Entrez!”

The door swung open, and a modishly dressed older woman, accompanied

by two younger women bearing boxes and large bags, came into the room.

The older woman’s eyes lit up as they beheld the slender, golden-haired girl in

the luxurious négligée. Not a great beauty, perhaps, but charming and even

lovely—given the proper clothing, which she was eager to supply! She burst

into staccato speech.

“Ah, Mademoiselle! Are you the young woman I am to have the pleasure

of dressing? Thank God you have a figure, and the looks to do me credit!

Now let me see your coloring, if you please! Will you step over to the win-

dow, Mademoiselle?”

Before the willing but slightly bewildered Cozette could catch her breath,

she found herself being robed in one attractive garment after another to the

accompaniment of a constant stream of advice, instruction, questions to

which the modiste did not wait for answers, and gossip about the great ladies

of London’s Beau Monde, which was so much Greek to Cozette, since she had

never heard of any of the ladies mentioned.

After half an hour of this, the girl called a halt. “Madame,” she said

firmly, “enough!” She softened that with a smile. “I do not know what you

have been told—”

“His Lordship has told me that you escaped the Terror with his beloved

nephew, and brought him safe through horrible dangers to London! For this

he wishes to express his thanks with a few garments, since you left everything

behind you when you fled the Revolution!” The modiste shivered with fright,

and her two girls echoed the gesture. But Cozette was not to be diverted from

her protest.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

16

“You have displayed gowns which would grace a duchess, Madame, but I

shall be fortunate indeed to obtain a post as a governess in this London, and I

must have gowns which will be suitable for that position. Oh,” she noticed

the shock upon three faces, “of course I must accept one or two dresses today,

since the clothing in which I made my escape is beyond use. Now I have

noticed two costumes which I think exceptionally pretty and quite suitable.”

Three faces brightened. “This seal-brown walking dress will resist staining and

be warm enough for your rather cool climate.” Three heads nodded agree-

ment. “Then there is this amber silk afternoon dress—ah, élégante! What

woman could resist it?”

Three wide smiles greeted that judgment. “And that brown cloak you have not

shown me yet,” Cozette pointed to a soft woolen cape one of the girls had placed

over a chair. “That should keep me warm while I look for work, n’est-ce pas?”

The modiste gave a sudden cackle of mirth, and said, in the strong accent

of her native Provence, “It will keep you warm, petite, no doubt about that! But

it may lose you the job, if the mistress of the house sees it!” She lifted the

cloak and flung it about Cozette’s shoulders with a fine flourish. It was lined

with sable. For just a moment Cozette cuddled the exquisitely soft fur around

her, then took it off with a sigh.

“Beautiful, but quite impractical,” she decided.

“On the contrary,” said the Earl, coming in through the open doorway, “it

is completely practical in this climate. We will have it, Madame, and any

other garments you deem suitable for a gently bred woman who is my

nephew’s companion and a member of my household.”

Now it was four female faces that were momentarily awe-stricken by the

virile force of the big man who confronted them. Then the modiste broke

into her normal stream of half-commanding, half-wheedling conversation, as

she began to display the various costumes she thought suitable. The Earl held

up one white hand.

“Thank you. Please leave whatever dresses Mademoiselle deLorme liked,

and send the account to my agent. Good day.” It was a firm though quiet dis-

missal, and the modiste knew it. Very quickly she gathered up those costumes

that had not suited Ma’am’selle for one reason or another, and, leaving behind

the boxes of delicate silk underwear and the smaller boxes of shoes, whisked

her assistants away with her.

Cozette stared with dismay at the heaps of clothing she had left. “I cannot

possibly pay for this upon the salary of a governess!” she protested.

“Then you will have to stay with me until you have worked it off, will you

not?” asked the Earl, coolly mocking.

Cozette glanced quickly at that saturnine face. For a moment she was sure

the Earl himself was surprised at what he had just said, but the fleeting expres-

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

17

sion faded almost at once into his usual arrogant calm. Observing this, the girl

said slowly, “It is a point of pride with the English to keep the face stiff, is it

not? Why should this be? Is it degrading to show emotion, Milord?”

The Earl stared at her uncomfortably. What was she at now, prying into a

man’s behavior? One kept one’s own counsel, to be sure! So his own father had

always instructed, and acted. It betrayed weakness to allow anyone to know

what emotions might be seething under a calm facade. To have such intimate

knowledge could give other men power over oneself. He looked at her coldly.

“If you are to remain here as Alexander’s governess, Miss deLorme”—no

more fancy French Ma’am’selles! Begin as you mean to go on—”you must learn

to control your own emotions, and your speech as well. Your unruly tongue

will bring you nothing but difficulty in England. And Alexander must be

trained to be less open, as well.”

The wide amber eyes fixed on his face so intently slowly darkened. “You

would make le petit Alexandre such a one as yourself? Cold and rigid and closed? I

cannot permit it!” she cried with a soft intensity.

“You cannot—? You have nothing to say about the way my nephew will be

trained. The sooner you realize that fact, Miss deLorme, the sooner you will

settle into your rôle in this household.” Then, seeing the stricken expression

on the small, delicately pretty face, the Earl relented enough to say, in a less

threatening tone, “I accept the fact that I owe you much for your rescue of the

child. For this reason alone, I am willing to permit you to remain here until

the boy is old enough to be sent to boarding school. Four years, possibly five.

By that time, if you are as frugal as the French female is reputed to be,” he

added with a note of mockery, “you should have been able to save enough

from your salary to keep you until another post can be found for you. You

seem well educated, for a female. The position of governess provides security

and protection from the harsher realities of life.”

Cozette found his patronizing attitude enraging. “I would venture to guess,

Milord, that I am better educated than you are! I have heard my father say

that young males in English public schools learn ‘small Latin and less Greek,’

as Jonson said of your great poet Shakespeare. All Englishmen, alas, do not

have Shakespeare’s genius to offset their lack!”

“Your father had made a deep study of English public schools?” sneered

the Earl. Really, this wasp of a girl had a diabolical skill for getting under

one’s skin! It could be quite dangerous to the smooth running of his house-

hold to hire her. Yet he did owe her a tremendous debt for bringing the boy

safe to England. He glared at the small, defiant figure in the pretty dark-

brown walking dress. A momentary memory of soft white shoulders and a

swelling breast under tattered silk invaded his mind, but he put it firmly from

him. The girl was a danger and he knew it. How to get rid of her without dis-

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

18

honoring his obligation to her? He said coldly, “If you find the English and

their ways so distasteful, permit me to discharge my great debt to you by

providing enough money for you to return to France, where things are done

so much better!”

It was a low blow, and he realized it as soon as the words had left his lips.

A wave of pallor blanched all color from her face, and the amber eyes dark-

ened with pain. After a moment she said, in a small, controlled voice that had

the effect of daunting the Earl, “I am afraid I cannot return to France, Milord.

My father was betrayed to the Tribunal, arrested for summary trial, and may

already have gone to the guillotine for aiding les aristos. His crime: He tried to

hide two noble children whom he was tutoring. I have nothing of which to be

ashamed, but there is no one left of my family to whom I could return in Paris.

I must accept your . . . generous hospitality for a time, until Lex is old enough

to go to school—or you decide to dismiss me.”

The Earl’s gaze dropped under that unhappy glance. He tried to shrug as

he turned slightly away. Well, he had got his wish; the girl was humbled and

submissive. “When you have eaten breakfast, will you be kind enough to

attend me in the library? There are certain matters which must be discussed in

a more formal atmosphere.” His gaze went around the bedroom, taking in the

bed disheveled by the boy and his companion. “You will be given the room

next to this—”

“A cot in the dressing room will be best,” Cozette corrected steadily.

“Then I can hear him if he calls out at night. His wardrobe should not be so

extensive just yet as to require the whole space in that room.”

“Do you have to challenge everything I say?” Milord found himself

snarling at the irresponsible little female. Humble? Submissive? That would be

the day! He glared at her defiant little face. “A good servant would know bet-

ter than to continue provoking her master!”

“I am not a servant, sir!” flared the girl.

“You have ample funds to support you in London without working?

Forgive me if I remind you, but you have just given me a pitiful little story

about your destitute and friendless conditions!”

His challenge forced her to lower her eyelids and retract her defiance.

“You are correct, of course,” she said after a moment. “I—I pray you will for-

give my—intransigence. I shall strive to—to control my emotions, to become

less . . . provoking.”

The Earl, although for the moment victorious, found himself strangely

anxious to get away from the face that seemed to reproach him. He wanted to

escape the awkward situation quickly, so he nodded and left the bedroom. It

is as though I were the one routed, he mused. What is it about this little

French waif which so unmans me? My father could have—And then he rallied

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

19

himself with a grimace of wry humor. I’ll wager the little tigress would have

proved a match even for him!

Cozette stood very still in the center of the room after he had left. Her

eyes were blind with sorrow at the reminder of her loss. It was something to

have been robbed of one’s father and one’s country in one disastrous blow.

What was left? The love of the boy, for whom she had both deep affection

and pity. Her other task, every hour becoming more urgent. And life itself, a

gift denied to so many of her countrymen. “I shall contrive, Father,” she whis-

pered. “If the sansculottes and the roving bands of soldiers and the rogues on the

roads could not destroy me, can I permit one cold and uncaring Englishman

to do so?” An involuntary shudder wracked her thin body. He was a formida-

ble antagonist, that Comte Anglais! She shrugged to rid herself of such sickly

fears. Where there is life, there is hope, she told herself sternly. I have le bébé

safe with his family, and myself secure for the moment in this great house-

hold. Perhaps it is not so bad! From such a haven I may quickly and unobtru-

sively accomplish my other mission. Meanwhile, Lex needs me in this

mausoleum. Á bas the arrogant Earl! She checked her appearance and went

down to the kitchen to ask for luncheon.

Chef Pierre decided, after one look at her, to accept this quietly élégante

countrywoman with the Parisian accent as a valuable addition to the staff.

Gouvernante to the newly discovered heir, she merited better service than a

plate at the servants’ table. So he had her placed in a small, unexpectedly

bright morning room, and prepared for her one of his finest omelettes aux fines

herbes, and the croissants he was saving for himself. Much flattered by her

knowledgeable appreciation of the feast, he himself presented wine and cof-

fee, and spent a few minutes deploring the anarchy that had overtaken their

beloved country.

It was Dibble, looking into the room in a search for the French girl, who

interrupted the chef’s discourse. Cozette rose, thanking him again for the

superb luncheon, then followed Dibble to Milord’s library.

That nobleman was waiting for her, the only visible signs of his impatience

being a fine white line outlining the haughty curve of each nostril. “I trust you

had a satisfactory luncheon?” he asked.

“Your chef is a master,” the girl acknowledged.

“Perhaps, then, you are ready to discuss the details of your position in my

household?” Without waiting for her reply, the Earl continued, “Normally,

my Comptroller, Ian Ross, would have dealt with the matter, but since it so

closely concerns family business—my heir—I shall handle it personally. I

have decided to keep you both here for a few weeks until I have learned to

know the boy, especially his habits and capacity of intelligence. I shall

instruct you as to what course of training I deem suitable for his further

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

20

development. Including, as you must be aware, the need for more restraint in

his behavior.”

“He is four years old,” said Cozette between her teeth.

“I am well aware of that,” replied His Lordship, moving aside to reveal a

small Persian rug dreadfully spattered with ink. “When I brought him in here

this morning, he seized my inkwell, as you see, a lion made of gold and cop-

per, and thinking it a toy, he tipped it over the rug before I could prevent him.

It was a very valuable rug.”

Cozette stared at the mess with horror. “If I had been here with him as I

should have been—!” she began.

The Earl held up his hand. “I had taken him from your care, to permit you

to eat your breakfast and to be fitted with needed clothing.”

“It will not happen again,” she promised, eyes steady on his. “As long as I

am here.”

“We shall see.” He shrugged.

“Where is Lex now?”

“I had Dibble give him into the care of one of the younger maids, who is

taking him for a walk in the garden at the center of the square,” the Earl

advised her. “When they return, Alexander is to be given his lunch in the

nursery and put down for a nap. The girl will stay with him until you return to

take charge. Now,” he said firmly, “I have written out a program and schedule

I wish you to follow. You are to have one hour a day free for your own com-

fort, as well as one whole day a month. Your salary will be as specified.” He

handed her two sheets of paper covered closely with firm writing, and a slip

with a figure. The sum of money astonished her, and she raised wide golden

eyes in inquiry.

“So much? To care for a little boy? I should prefer to do it for nothing.”

“But I prefer you to receive the money, and I am the master here,” said the

Earl with chilling hauteur.

Cozette glared at him. Why did he have to make even his great generos-

ity feel like an insult? The master, indeed! “You are more haughty than the

greatest aristocrat in France!” she heard herself saying.

“My lineage is equally distinguished, I am sure,” said the twelfth Earl of

Stone and Hamer coldly. His glance rested upon a carved escutcheon over the

massive fireplace. The girl’s gaze followed his. Carved deep into the wood was

a great hammer which seemed about to crash down upon a massive stone.

Beneath it was the legend, Beware the Might of Stone and Hamer.

It could have been an omen. Cozette shivered. The nobleman regarded

her thoughtfully.

“I think you will be very careful of the boy until he is feeling secure in his

new life. Has he spoken of his parents?”

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

21

“Once or twice,” replied Cozette. “I have told him they have gone to

Heaven, where he will one day join them. He asked, le pauvre petit, when we

landed in England off the fishing boat, if this was Heaven.”

“I imagine you told him it was not,” said the Earl caustically.

The girl nodded. “I have tried to comfort and entertain him. He is a

brave, cheerful little child. I believe you will grow to love him and take pride

in his manliness.”

“Then let us both make sure you do not undermine his manliness with too

much cossetting,” advised her employer.

Cozette should have let it go at that, but her evil genius prompted her to say,

rather pertly, “You wish all that joie de vivre to turn into cold, rigid insensitivity?”

In a single swift stride he was beside her, towering over her with a con-

trolled rage that suddenly terrified her. He took her arm in a grasp that made

her flinch. “First,” he said in a voice so low she had to strain to hear it, “you

will never again use that tone of voice when speaking to me. I am master here.

Do you understand that?”

“Yes,” the girl whispered, appalled at the fury she had unleashed.

“Second, you will follow my instructions as to the child’s schedule and train-

ing exactly. Is that clear?”

“Yes.” Cozette felt her composure returning slowly, but she was shocked at

the ease with which he had dominated and frightened her.

“Third, you will adopt an attitude toward the child which is compatible

with my wish to see him become an English gentleman, not some foreign fop,

mawkish and theatrical. Do I make myself plain?”

Cozette’s chin lifted. The taunt that foreigners were too emotional had

gone home. Her amber eyes blazed gold defiance. “Yes, Milord, I under-

stand your wishes. And the child is, after all, of your blood, and must live in

your world.” Heaven defend him, her eyes seemed to add. “But I am not one

who can thrust all human feeling into a deep well, or under a heavy rock. I

can only love the child, and care for him in ways that le bon Dieu has given

me. You may dismiss me from your service if you become dissatisfied with

my—my attitude!”

“Be very sure I will,” snapped the Earl.

Still he did not release his crushing grip upon her arm, and his ice-gray

eyes seemed to bore into her very brain. After an uncomfortable pause,

Cozette tried to draw her arm away. Subtly, the Earl’s manner changed. His

grip softened but remained firmly on her. The ice-cold eyes warmed with lit-

tle glints, and he scrutinized her face and then her body in a leisurely manner

that was like an insult.

Cozette’s quick anger flashed. “Let me go at once, sir! I am not accustomed

to such—”

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

22

“Such what?” inquired the Earl, lazily insolent. Very obviously he allowed

his gaze to rest upon her breast, now moving quickly with the force of her

anger. “Perhaps I should take advantage of that hot Gallic emotion that comes

to you so easily?” he speculated, his manner a subtle affront. “The idea inter-

ests me, but there are always problems. Are you by any chance untouched?

How old are you?”

Cozette jerked her arm away from his grip. “I am twenty,” she said in a

voice whose coldness rivaled his most chilling speech. “I am the spinster

daughter of an intellectual, carefully reared within a safe and loving home. I

am not a woman of the streets, nor do I intend to be treated as such! Is that

clear to you, Lord Stone?”

Before he could answer her, she had turned away to leave his infuriating

presence. The sound of his voice stopped her. “You will remain here until I

dismiss you. How many times must I remind you that I am the master in

this house?”

Ignoring her outraged glare, he produced a small, grimy packet from a

drawer in his desk. “You will tell me how you got these.”

“Your brother brought them to my father for safekeeping the day he . . .

died,” said Cozette gently. “He and his wife were worried about the unrest in

Paris, the violence, the suspicion of foreigners. My father advised them to

make ready to return to England at once. Your brother’s wife was reluctant to

leave her beloved Paris, but had finally agreed to do so. There were papers and

official permissions to get, passage on the stage to be arranged for . . . It was all

in train on that fateful day.” She twisted her hands in anguish. “Oh, if only they

had heeded the warnings a little sooner! They were so young—so happy!”

The Earl’s face was set in hard lines, his eyes hooded by the heavy lids.

After a moment, he said, “And now you will tell me why you were so nervous

when you noticed that I had taken the papers.”

Did the man miss nothing? Cozette’s heart sank. Did she dare to lie to

him? She must! The second packet was of so vital, so demanding an impor-

tance that she dreaded to think what her few days of hesitation, of postpone-

ment of that imperative duty, might result in.

The Earl’s hard gaze had never left her face. “Tell me what is wrong,” he

said harshly. “Is there another packet? Did you think I had found the wrong

one? Is that why you were terrified when you saw this one in my hands?”

When Cozette shook her head blindly, refusing to answer, he went on inex-

orably, “What other important papers might a little Frenchwoman have

brought to England? Was your ‘rescue’ of my nephew merely a blind for some

other, less humanitarian scheme?”

“Your nephew’s safety has been my first objective,” said Cozette stolidly.

“But not your only object?” demanded the man. “If I am to trust you—”

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

23

“If you do not trust me,” interrupted the girl, “I shall leave at once.”

But this easy solution was not acceptable to His Lordship, it seemed.

“Since I have admitted you into my household, and am, in some sense,

responsible for your actions, I must know what sort of—person I have spon-

sored. Are you, Ma’am’selle deLorme, under your rather charming affectation

of romantic innocence, a calculating little spy?” He snapped the last word out

at her so sharply that it shook her composure exactly as he had intended.

Cozette stared at him, a bird hypnotized by a snake, fascinated by his

piercing stare. “It is a private matter between my father and—and an old

friend of his.”

“And would this ‘old friend’ be an informer or agent for the French gov-

ernment?” challenged the Earl.

The girl, white-faced, met his probing stare openly. “I can tell you only

this: The person to whom I am to deliver my message is a member of the

British government.”

The Earl was smiling unpleasantly. In the light, which seemed to Cozette

to be dazzlingly bright, his handsome face bore a look of hard arrogance that

daunted her. She forced herself to look straight into those intimidating silver

eyes. She must keep her wits about her! The secret was not hers to tell! What

was he saying?

“Are you so naive that you do not know there are many political factions

in my country, and that some of them might not be blindly devoted to the

party in power? Some in fact are subversive, and would like nothing better

than to do our country harm!” He stepped to her side and shook her fiercely.

“Are you a spy? I demand to know!”

“I am not a spy,” said Cozette. Her mind was racing. No simple excuses

would convince this astute antagonist. What was a likely story? He obviously

believed that she—and all women—were romantic idiots. She took a deep

breath and plunged into speech.

“My father met a certain Englishwoman when both were younger—before

he met my mother, that is. Papa knew that his chance of surviving the Terror

was slight, and wished to bid farewell to a lady for whom he had always felt

the deepest affection and admiration.” She sighed soulfully. It could have been

true—and if so, how romantic!

“Very pretty! Quite an histoire, in fact! Very likely a lie. But if your mission

is one of pure sentiment, then you will have no reason to refuse when I ask to

behold this so harmless letter.”

Caught up in the emotions appropriate to her story, Cozette glared at him.

“Have you no delicacy of feeling? No sense of propriety? How can you

demand to read a private communication? Another man’s love letter?” She was

halfway to believing her own invention.

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

24

The Earl glared at her in exasperation. Then heavy lids drooped over the

piercing silver eyes, and he said, “Your father’s position was—is,” he corrected

himself, “a precarious one. He must have felt an overwhelming need to have

that letter delivered, if he was willing to send his only daughter.”

“He also had an overwhelming need to send Lex to the safety of his own

family,” the girl reminded him. “I believe he was trying to protect me from

the—savage, senseless cruelty of the Revolutionary Tribunal.”

The Earl was silenced by the controlled anguish in Cozette’s voice and

expression. After a moment he said quietly, “Do not despair, my child. A man

of your father’s spirit will survive, depend upon it! He has done nothing for

which he might . . . receive a heavy penalty.”

Cozette, aware as he never could be of the hazards and the injustices of

the revolution, made no reply. He had only, in fact, expressed her own deep-

est hopes for her beloved parent.

After a moment, the Earl said, more kindly than he had ever spoken to her.

“Your father entrusted you with heavy responsibilities, Ma’am’selle.” Then, as

if compelled, he added, “He seems to have judged you correctly.”

Cozette felt a remarkable pleasure in this half-apology. That this cold man

should speak well of her inexplicably pleased her. Now he was going on, “You

may give your Papa’s letter to one of my grooms. It will be delivered today.”

Alarm! Had the creature been lulling her into a false sense of security, only

to pounce? Think quickly, Cozette!

“I could not treat so delicate a matter so casually,” she objected. “A groom to

present such an intimate message? No, no, Milord, I must deliver it in person!”

And she smiled sweetly. Checkmate!

Not so!

“Then you must use one of my carriages,” instructed her antagonist blandly. “I

shall tell Dibble to have one waiting for you. You will not wish to lose any time.”

And of course the coachman would report the address without loss of time

to his master! It was clear to Cozette that the Earl was still suspicious. This

was no time to provoke him further. She said gently, “I shall be happy to

accept your most generous offer—when I can find time. At the moment I

must go to Lex. Thank you, Milord!”

“You are welcome.” The odious creature was deliberately taunting, as

though he knew she had lied to him; as though he had discovered and opened

the packet. Could she bring herself to share the dangerous secret with him?

She bit at her full lower lip, considering the risks.

“But now you must go off to find Lex,” the Earl reminded her mockingly.

Seething, the girl dropped him her most formal curtsy and walked from

the library as haughtily as she could.

The Earl laughed!

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

25

3

S

eated alone beside the sleeping child later in the afternoon, Cozette

tried to decide upon a course of action. She had, as she had promised

Papa before they came for him, delivered the small boy to his father’s

people. In theory, then, that part of her task was completed. Yet there

was an atmosphere in this great mansion, a formality, a chill, that might

destroy the spontaneous charm and joy of the small child so peacefully rest-

ing near her. He had had enough to bear in his short life! And so, if it came

to that, had she!

Cozette recalled that hasty, furtive departure . . . the house in darkness,

the servants vanished, her father carrying small Alexandre in his arms through

the passage to the deserted kitchen; Papa’s steady eyes and his final quiet-

voiced instructions to her before he gave the child into her arms and silently

opened the back door into the reeking alley. And then the thunderous,

dreaded, yet expected knocking at the front door, and her father closing and

locking the kitchen door behind her without even time for a farewell kiss or a

father’s blessing! Biting her trembling lips, Cozette had made her stealthy

flight over the slimy cobblestones, not daring to weaken her self-control by

thoughts of the beloved parent even now facing the dread interrogation; only

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

26

wondering if he had been deceived, or if there would in fact be the promised

covered dung cart behind whose noisome vats she could crouch with the

small drugged boy, her dark cloak spread over them both.

It had been her father’s idea that even rabid revolutionaries would not wish

to examine so malodorous a vehicle too closely. So it had proven. Her taci-

turn driver had not been stopped until they reached the gates of Paris. There,

he had been waved on with crude shouts. When finally he drew up in a farm

barnyard at dawn, he did not reply as Cozette thanked him for their safe

deliverance out of the city. Stiff from the long confinement, the girl staggered

down from the cart and pulled the boy gently out after her. The driver merely

stared at her out of dark, hooded eyes in a seamed gray countenance, then

turned away and drove the cart behind the barn.

“Are we there, Cozette?” The child’s voice had recalled her to her respon-

sibility. Alexandre’s eyes were heavy and dazed, but utterly trusting as he

stared up at her.

“Not yet, mon brave,” she replied with a warm, reassuring smile. “First we

must eat, and then find a less smelly way to continue our journey, no?”

The boy smiled at her, wrinkling his little nose. A wave of tenderness for

the small figure had swept over the girl. She resolved grimly to get young

Alexandre to safety with his father’s people no matter what it cost her.

And she had done so, she reminded herself, staring down at the boy’s

relaxed body. The Earl had accepted his nephew’s arrival with a coldness she

supposed might be natural to the very restrained English. Accepted; not wel-

comed. Therein lay her problem. Could she abandon the child to the frigid-

ity of this English household? Would he be unhappy, lonely, frightened? Of

course he would! His parents had been loving, if casual, in their attitude

toward him. The concierge’s wife had acted as a surrogate grandmother to the

child, and Cozette had found herself cast in the role of sister, friend, and

occasional governess. Now Neville and his Charmaine were dead; the

concierge’s wife had begged her to remove the boy because she was afraid for

her own family; and Cozette’s father, who had taken the child under his quiet

protection, was . . .

He had warned her it was unlikely he would survive the interrogation,

known adherent to the King’s cause as he was. Yet there had been only

warmth and the serenity of quiet dedication in his countenance as he left her

that night.

The girl rose and walked quickly to the window to drive away such

anguished recollections. She must control her turbulent emotions, become as

calm and self-controlled as her host. Learn, in fact, to keep the stiff upper lip!

She picked up the schedule the Earl had handed to her and began to read

it carefully. She was relieved to discover that the subjects he had noted for his

Elizabeth Chater—The Earl and the Émigrée

[ e - r e a d s ]

27

nephew’s program of study were well within her scope—although she

doubted the wisdom of instructing a four-year-old boy in even simple mathe-

matics or history. Still, perhaps she could make games out of numbers, games

that might interest a small boy. And the history could be told as exciting sto-

ries of valorous knights and deeds of great bravery; surely such tales would

enthrall a child as bright as Lex.

Nodding with satisfaction at her plan for interesting studies, Cozette