Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig Johansson

University of Oslo

Abstract

The paper gives an overview of developments in the use of corpora in English language

research, from corpora before computers, through the small (from our present

perspective) classical corpora, to the vast and varied collections that are now available.

Special attention is paid to ICAME, the International Computer Archive of Modern

English (now: the International Computer Archive of Modern and Medieval English),

which from its modest beginnings in 1977 has turned into a world-wide community of

scholars active in the field. Some areas where there has been considerable achievement,

and where there is a great potential for future work, are singled out: language variation,

lexis, grammar, and contrastive linguistics. After about forty years of computer-corpus

research, much has been achieved, but it is likely that we are only at the beginning of the

era of corpus linguistics. If corpora are used with care and imagination, corpus studies

have a bright future.

1. Introduction

First of all, I am greatly honoured to be invited to give a talk to this conference.

Thank you very much.

I was asked to talk about corpus linguistics in retrospect and in prospect. It

was an oversight on my part that I picked the title “Corpus linguistics—past,

present, future”, which was similar to the topic of a lecture given previously to

this association by Jan Aarts. I hope, however, that it will be instructive to

compare the ways in which we approach the subject. Although we share the view

that corpus studies are fundamental in linguistics, we have been involved in

different projects, and this must inevitably have led to some differences in

emphasis and point of view.

2.

What is corpus linguistics?

‘Corpus linguistics’ is a fairly new term, but it is frequently used. We find it in

book titles such as Corpus Linguistics: Recent Developments in the Use of

Computer Corpora in English Language Research (edited by Jan Aarts and

Willem Meijs, 1984), Corpus Linguistics Hard and Soft (edited by Merja Kytö et

al. 1988), English Corpus Linguistics (edited by Karin Aijmer and Bengt

Altenberg, 1991), Directions in Corpus Linguistics (edited by Jan Svartvik, 1992),

and Graeme Kennedy’s Introduction to Corpus Linguistics (1998), to mention

just a few. There is a journal called the International Journal of Corpus

Stig

Johansson

4

Linguistics, of which I am the consulting editor. And there is an association of

English corpus linguistics in Japan, which is the only national organisation, as far

as I know.

The term ‘corpus linguistics’ may, however, be misleading. It is not

comparable with a term like sociolinguistics, which is defined by the object of

study: language and society. The aim of corpus linguistics is to study language

through corpora. It is an approach to the study of language. Note what Wallace

Chafe wrote in a paper published in the early 1990s:

What, then is a ‘corpus linguist’? I would like to think that it is a

linguist who tries to understand language, and behind language the

mind, by carefully observing extensive natural samples of it and then,

with insight and imagination, constructing plausible understandings

that encompass and explain those observations. […] But I continue to

believe that one should not characterize linguists, or researchers of

any kind, in terms of a single favorite tie to reality. […] I would like

to see the day when we will all be more versatile in our methodologies,

skilled at integrating all the techniques we will be able to discover for

understanding this most basic, most fascinating, but also most elusive

manifestation of the human mind. (Chafe 1992: 96)

Although the term is not unproblematic, it may be useful to talk about corpus

linguistics to underline that it is an important and useful approach to language

studies. Is it really necessary to say this? I am afraid it is. Bas Aarts, University

College London, made an interview with Noam Chomsky a few years ago

(February 1996, private communication; see also Aarts 2000: 5f.). In response to

the question “What is your view of modern corpus linguistics?” Chomsky said “It

doesn’t exist. If you have nothing, or if you are stuck, or if you’re worried about

Gothic, then you have no choice.” Later in the interview he said: “You don’t take

a corpus, you ask questions.”

I beg to differ. There is no conflict between using a corpus and asking

questions. It is not possible to do anything interesting with a corpus if we do not

take care in formulating research questions. But there is a danger these days

when corpora are easily available and ready to use that we forget this. Many years

ago Bengt Sigurd made the following remark in a paper on the effects of the

computer on linguistics:

The computer easily fills a cellar with tables showing what letters are

most frequent in the third word of sentences, what words contain the

letter y, what words are followed by och [‘and’], etc. It is easy for a

linguist to drown in this sea of information. But linguistic facts are

only interesting scientifically if they can be related to other facts, and

can be interpreted and explained. The computer easily fills a whole

cellar with answers to which it may be difficult to find sensible

questions. (Sigurd 1980, quoted in translation)

5

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Using a corpus without formulating a question is like looking for a needle in a

haystack—and having forgotten what one is looking for.

Traditionally, before the age of computer corpora, linguists who were

concerned with text-related studies started out with a research question and

collected material that was suitable for studying this. It was usually a long and

laborious process. What is important in going to a computer corpus that

somebody else has compiled is to consider whether it is suitable for our research

question. Not: here I have a corpus, what can I do with it? But: I have a research

question, is the corpus appropriate?

What sorts of questions can we ask? I would like to stress that there is a

wide range of possible questions. Many years ago Dell Hymes wrote that “…

four questions arise in the study of language and other forms of communication:

● whether (and to what degree) something is formally possible;

● whether (and to what degree) something is feasible in virtue of

the means of implementation available;

● whether (and to what degree) something is appropriate (adequate,

happy, successful) in relation to a context in which it is used and

evaluated;

● whether (and to what degree) something is in fact done, actually

performed, and what its doing entails.” (Hymes 1972: 281)

Linguists have a tendency to dictate the sorts of questions that are considered

essential or respectable to ask. I think we should be open to different types of

questions, whether we use corpora or not. For some types of question corpora are

essential, if not indispensable.

Formulating research questions is our primary task. Graeme Kennedy puts

it in this way in his book on corpus linguistics:

Linguists use corpora to answer questions and solve problems. […]

The most important skill is not to be able to program a computer or

even to manipulate available software (which, in any case, is

increasingly user-friendly). Rather, it is to be able to ask insightful

questions which address real issues and problems in theoretical,

descriptive and applied language studies.

(Kennedy 1998: 2)

The questions we can ask are only limited by our imagination. It is our task as

corpus linguists to formulate important research questions.

3.

Corpora—old and new

Although the term ‘corpus linguistics’ is relatively new, the notion of a corpus is

an old one. The Oxford English Dictionary records the use of the word in the

sense of a collection of texts from the first half of the 18

th

century:

Stig

Johansson

6

A body or complete collection of writings or the like; the whole body

or collection of literature on any subject.

The linguistic use of the term is recorded from 1956 and is defined as follows:

The body of written or spoken material upon which a linguistic

analysis is based.

Following W. Nelson Francis, a corpus pioneer who sadly passed away earlier

this year (2002), the corpus approach is much older. In a paper published in 1992

he writes about “Language corpora B.C.”, which in this case does not mean

before Christ, but before computers—or perhaps before the Brown Corpus!

Nelson Francis refers to the vast data collections for large dictionary, dialect, and

grammar projects, like Johnson’s dictionary, the Oxford English Dictionary, the

Survey of English Dialects, and Jespersen’s Modern English Grammar.

These corpora could not be manipulated by computer programs to reveal

patterns which might be hard to discover by other means. They could not be

easily transported beyond the place of origin. Above all, corpora B.C. frequently

consisted of collections of citations rather than texts. Hence they were inevitably

biased by the perspective of those who had collected the material. This is true of

the collections for the Oxford English Dictionary and Jespersen’s Modern

English Grammar, to take two celebrated examples. Commenting on the

collections of some classical English grammarians, Nelson Francis points out that

they are “inevitably skewed in the direction of the unusual and interesting

constructions that the readers encounter, at the expense of the natural use of

language” (Francis 1992: 28f.). James Murray makes a similar point about the

quotations collected at the early stages of the project which led to the Oxford

English Dictionary: “the editor or his assistants have to search for precious hours

for examples of common words, which readers passed by … Thus of Abusion, we

found in the slips about 50 instances: of Abuse not five.” The instructions were

accordingly adjusted to include: “Make as many quotations as you can for

ordinary words, especially when they are used significantly, and tend by the

context to explain or suggest their own meaning” (quoted from Murray 1979:

178).

The natural solution to this problem is to collect texts in a systematic

manner and subject them to the principle of ‘total accountability’. This was the

thinking behind the Survey of English Usage corpus (Quirk 1960), which was

‘B.C.’ in its conception, but has later been computerised. With this sort of corpus

and the proper computational tools, it is possible to study “the capriccio of

language” as well as “the equally characteristic ostinato”, to quote from Sture

Allén (1992: 1), a pioneering Swedish corpus linguist and former secretary of the

Swedish Academy. Linguists who use a computer corpus and attempt to take

account of all the material relevant to their research question may be forced to see

what they might otherwise overlook.

7

The Survey of English Usage was a breakthrough in the study of the

English language. Texts, both written and spoken, were collected in a principled

manner. They were carefully annotated for a range of features, and the material

was recorded on index cards which were kept in filing cabinets at University

College London. Researchers used to visit London to inspect the valuable

material. We are now very close to our notion of a corpus, except that the

material was not yet available on computer. But we are on the eve of what some

people have termed ‘the corpus revolution’.

4.

From the Survey of English Usage to the Brown Corpus

In his paper on “Problems of assembling and computerizing large corpora”

Nelson Francis writes that, when they were planning the Brown Corpus, they

convened a conference of “corpus-wise scholars”, including the director of the

Survey of English Usage, Randolph Quirk. He continued:

This group decided the size of the corpus (1,000,000 words), the

number of texts (500, of 2,000 words each), the universe (material in

English, by American writers, first printed in the United States in the

calendar year 1961), the subdivisions (15 genres, 9 of ‘informative

prose and 6 of ‘imaginative prose’) and by a fascinating process of

individual vote and average consensus, how many samples from each

genre (ranging from 6 in science fiction to 80 in learned and

scientific). (Francis 1982: 16)

Francis goes on to give further details on the text selection, he comments briefly

on the process of computerising the material, and in passing he mentions the cost

of producing the corpus:

The million of words of the Brown Corpus cost the United States

Office of Education about $ 23,000 in 1963–64, or about 2.3 cents a

word. (Francis 1982: 15)

In retrospect, we must say that this money was indeed very well spent.

The Brown Corpus has been significant in a number of respects. It

established a pattern for the use of electronic corpora in linguistics, at a time

when corpora were negatively regarded by linguists in the United States, as

shown by the well-known story of the meeting between Nelson Francis and

Robert Lees, one of the leading generative grammarians at the time (Francis

1982: 7). It was significant in the care which was taken to systematically sample

texts for the corpus and provide detailed documentation in the accompanying

manual (Francis and Kučera 1964, 1971, 1979). But the world-wide importance

of the Brown Corpus stems from the generosity and foresight shown by the

compilers in making the corpus available to researchers all over the world.

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

8

5.

The International Computer Archive of Modern English (ICAME)

In the early 1970s Geoffrey Leech at the University of Lancaster took the

initiative to compile a British counterpart of the Brown Corpus. This is what he

had to say about it at the first ICAME Conference in Bergen in 1979:

About seven or eight years ago I wrote to Nelson Francis, who at the

time had already completed his Brown Corpus, and I said “Wouldn’t

it be a jolly good idea if somebody did a parallel corpus for British

English?” … I remember Nelson was extremely friendly and helpful.

He gave us all the information so that we could learn from his work,

and the last thing he said to us was “Rather you than me. I wouldn’t

do it myself, but I send you my best wishes.” (quoted from the

ICAME Journal 20: 100f.)

Given the technical resources at the time, the making of a million-word corpus

was a major undertaking. After a great deal of work had been done at Lancaster,

the project was taken over and finished in Norway, through cooperation between

the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities

at Bergen. This is how the corpus got its name: the Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen Corpus.

Compiling the LOB Corpus was no easy task, in spite of the excellent

example set by the Brown Corpus. One difficult problem, which had threatened

to stop the whole project, was the copyright issue. This led indirectly to the

beginning of the International Computer Archive of Modern English (ICAME).

In February 1977, a small group of people met in Oslo to discuss the

copyright issue as well as corpus work in general. Geoffrey Leech came from

Lancaster with a suitcaseful of corpus texts. The other participants were: Nelson

Francis, who was then visiting professor at the University of Trondheim in

Norway, Jan Svartvik, who was working on the London-Lund Corpus, Jostein

Hauge, director of the Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities, Arthur

O. Sandved, chairman of the English department at the University of Oslo, and

myself.

The outcome of the meeting was a document announcing the beginning of

ICAME. I quote a passage from the text (see the ICAME Journal 20: 101f.):

The undersigned, meeting in Oslo in February 1977, have informally

established the nucleus of an International Computer Archive of

Modern English (ICAME). The primary purposes of the organization

will be:

1) collecting and distributing information on English language

material available for computer processing;

2) collecting and distributing information on linguistic research

completed or in progress on the material;

9

3) compiling an archive of corpuses to be located at the University

of Bergen, from where copies could be obtained at cost.

One of the main aims in establishing the organization is to make

possible and encourage the coordination of research effort and avoid

duplication of research.

The document announcing the establishment of ICAME was circulated to

scholars active in the field, and it was used to support applications for permission

to include texts in the LOB Corpus.

6.

From the Brown Corpus to the LOB Corpus

What was it like working on a corpus at this time? In the first instance we had to

identify the copyright holders, which was a difficult task as there were several

hundred. We (that is, I) wrote several hundred letters asking for permission. If

there was no reply, we had to write again, and in some cases we had to replace

texts that had previously been selected at Lancaster. While this was going on, we

also proofread and corrected the texts. Most of the texts had been typed in using

rather primitive equipment, and there were many errors. Knut Hofland at the

Centre in Bergen provided printouts, and in Oslo we (that is, mainly I) checked

the texts for errors and inconsistencies in coding. These were then corrected by

staff at Bergen. By the end of 1978 we had finished the LOB Corpus and

published the manual to go with the corpus, where details are given on the

sampling and coding of the corpus texts (Johansson et al. 1978). By this time

there had been great advances in computer technology, so the format of the LOB

Corpus was easier to read and handle than the original Brown Corpus. At about

the same time Knut Hofland made a revised version of the original Brown Corpus,

with upper- and lower-case letters and other features which reduced the need for

special codes and made the text more easily readable. At this time we had also

started a newsletter, ICAME News (which later became the ICAME Journal), and

the Centre in Bergen had started distributing corpora under the auspices of

ICAME (see further 7.5 below).

Matching the British and the American corpus was not always

straightforward (see Johansson 1992). For example, it was not easy to match the

‘Adventure and western’ category in the Brown Corpus. For this reason, the LOB

Corpus contains more general adventure stories, though there are also some texts

set in former British colonies, a setting which was thought to resemble the

western situation to some extent. More important, there were necessarily some

differences in the newspaper categories, as the pattern of newspaper publishing is

quite different in the United Kingdom and the United States. These matters are

discussed in detail in the LOB Corpus manual.

The matching becomes even harder with other corpora compiled according

to the Brown and LOB model, and it is a problem which besets all attempts to

replicate corpora in different languages or across varieties of the same language. I

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

10

am not suggesting that it is impossible or that such attempts should be given up,

but rather that great care should go into the planning of such projects, and

possible problems should be kept in mind in evaluating results from a comparison

of such corpora.

After the LOB Corpus had been completed, the next task was to tag the

corpus so that it could be used more efficiently for linguistic studies. A

symposium on grammatical tagging was held in Bergen in March 1979. There

were some 30–40 participants, including: Jan Aarts, Alvar Ellegård, Geoffrey

Leech, Randolph Quirk, Jan Svartvik, and the two Brown Corpus pioneers,

Nelson Francis and Henry Kučera.

Alvar Ellegård presented his detailed system of manual tagging used for

parts of the Brown Corpus (see Ellegård 1978), Jan Aarts described the system

developed at Nijmegen (see Aarts and van den Heuvel 1980), and Nelson Francis

and Henry Kučera spoke about the automatic word class tagging system used for

the Brown Corpus (see the report in ICAME News 2, 1979). The most tangible

result of the symposium was the promise, extracted by Geoffrey Leech in

exchange for a couple of bottles of wine, that the tagged Brown Corpus would be

put at our disposal in our work on the tagging of the LOB Corpus.

Before I move on to this, let me just say that nobody knew at the time that

the symposium in 1979 would be the start of a whole series of ICAME

conferences. A second conference was held in Bergen in 1981. One of the

participants was Magnus Ljung, who undertook to organise a conference in

Stockholm the following year. This was the start of the regular ICAME

conferences, which have been arranged annually since then.

The availability of the tagged Brown Corpus was of crucial importance for

the tagging of the LOB Corpus, although our project opted for a probabilistic

rather than a rule-based approach to tagging and disambiguation, an exciting idea

originating from Geoffrey Leech. The tagged Brown Corpus provided the first

probabilities for tag combinations in the tagging suite which later came to be

knows as CLAWS (Constituent-Likelihood Automatic Word-tagging System; see

the description in Garside et al. 1987).

The tagging of the LOB Corpus took a long time, not just because new

programs were developed, but also because of all the work that went into the

manual post-editing of the corpus. For me it meant hundreds of hours checking

the consistency of tagging, the general idea being that the post-edited corpus

would provide a better basis for statistics on tag combinations, and that these

could in turn be used in further development of the tagging suite. Again there was

cooperation between Oslo and Bergen. Knut Hofland provided me with

concordances for troublesome words. I checked the consistency of tagging and

sent lists of corrections back to Bergen. I have reported on some experiences

from the post-editing in a paper on “Grammatical tagging and total

accountability” (Johansson 1985). Examining the output of the automatic tagging

programs was not just a lot of hard work, it also gave me new insight. To take a

couple of examples from the paper:

11

a. The earnings rule was analysed as determiner + plural common

noun + verb rather than as determiner + plural noun + singular

noun. Still was identified as a singular noun in the rich still

supplied the traditional revenues. Orange planters and grave

digger were tagged as adjective + noun, and the same applies to

the last two words in stripping off to just underpants. These are

grammatically likely interpretations, though inappropriate in the

context. They could easily be corrected.

b. In other cases there was no single correct tagging, as in He didn’t

like her wearing jeans. Should her be analysed as a possessive

determiner or as an accusative form of the pronoun? What tag

should be assigned to in in expressions like in here and in there?

This is a context where we find both typical prepositions, such as

from, and typical adverbial particles, such as back. To take

another example, what tag should be assigned to like in feeling

very like a child, preposition or adjective?

Even greater problems were posed by -ed forms and, in particular, -ing forms,

which are chameleon-like and notoriously multifunctional (see the discussion in

the manual for the tagged LOB Corpus, Johansson et al. 1986). Having to deal

with a corpus in this way concentrates the mind. In retrospect, it could perhaps be

said that all the effort that went into the post-editing was misguided. Is it always

advisable to opt for a single tag? There is genuine ambiguity in language, there

are not always clear borderlines. Ideally the tagging system should reflect the

indeterminacy in language.

Before I leave this topic, I should point out that there are some differences

in the tagging of the Brown and LOB corpora, both in the tag set and in the way

distinctions were drawn. This means that comparisons based on the tagged

versions of the two corpora must be made with caution.

7. Developments

From LOB and Brown I turn now to some of the most significant trends up to the

present time. The development has been explosive, partly due to the rapid

technological advances and partly because of the increasing interest among

linguists in the study of language use rather than language systems in the abstract.

7.1 Quantity

of

text

The most obvious change has to do with the quantity of text. We now have

corpora of millions of words, such as the hundred-million-word British National

Corpus and the Bank of English, which is reported to contain several hundred

million words. The very notion of a corpus has undergone changes. As early as

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

12

1982 John Sinclair introduced his idea of monitor corpora, referring to gigantic,

slowly changing stores of text (Sinclair 1982: 4), and in recent years we have

witnessed a virtual explosion of material on the web, and some people speak

about the web as a corpus.

In view of these developments, is the traditional notion of a corpus

obsolete? I believe not. The material on the web is a good supplement, but not a

substitute. The quality of the material is variable, and the origin is often uncertain.

Something may still be said for smaller, carefully constructed corpora which can

be analysed exhaustively in a variety of ways. These will be needed for types of

texts which are not readily available in machine-readable form, not least spoken

material. Such texts will have to be keyboarded in the foreseeable future. There is

no simple answer to the question how a corpus should be structured and how

large it should be. It depends upon the research question.

7.2 Variety

of

text

In planning the Survey of English Usage, Randolph Quirk outlined an impressive

scheme to represent a wide variety of types of spoken and written English. The

idea of representing a broad range of texts was a guiding principle in the

compilation of the Brown and LOB corpora, except that speech was not included.

Some of the large corpora compiled in recent years have also been intended to be

broadly representative, notably the British National Corpus, which was planned

according to a careful design to represent present-day British English.

There is similar variety in some recent smaller corpora, such as the clones

of the Brown and LOB corpora (FROWN and FLOB) compiled at the University

of Freiburg under the direction of Christian Mair and the corpora within the

International Corpus of English (ICE) project initiated by Sidney Greenbaum.

The primary aim of these projects is to study recent changes in English and

geographical variation in English, respectively.

Apart from such broad-range corpora, there are many more specialised

corpora, such as:

•

historical corpora for studying language change, e.g. the Helsinki Corpus

and associated corpora compiled under the direction of Matti Rissanen and

his colleagues;

•

learner language corpora, such as the International Corpus of Learner

English (ICLE), a project initiated and coordinated by Sylviane Granger;

•

bilingual and multilingual corpora for contrastive analysis and translation

studies, e.g. the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus and the Oslo

Multilingual Corpus (see 8.4 below).

The variation in the types of corpora reflects the research questions of the

compilers.

13

7.3 Quality

of

text

The Survey of English corpus set a standard not just in the principled approach to

text collection, but also with respect to the quality of the text. As mentioned

above (Section 3), all the texts were carefully annotated, and the spoken material

was transcribed in great detail, noting not just stress and intonation, but also

paralinguistic features, such as tempo and voice quality (some of the notation was

sacrificed when the spoken material was computerised and was made available as

the London-Lund Corpus; cf. Svartvik and Quirk (1980)).

The earliest computer corpora consisted of raw text, but both the Brown

and the LOB corpora were later annotated on the word-class level (cf. Section 6

above), allowing more sophisticated searches and analyses. With the development

of automatic tagging programs, it has become possible to tag even large corpora

like the British National Corpus (though only a small portion of the texts have

been checked for errors and post-edited). Syntactically parsed corpora are still

rare, due to the difficulties of analysing syntax by computer, but there seems to be

an increasing interest in building treebanks. Well-known early examples of

treebanks are those built at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of

Lancaster.

An annotated corpus which has recently become available is ICE-GB, the

British part of the International Corpus of English (see Nelson et al. 2002), which

has been syntactically annotated and checked and comes with a sophisticated

search program. Moreover, the spoken material has been digitised and linked with

the transcription. As the corpus is relatively small measured by today’s standards,

one million words, it is less useful for lexical studies than the British National

Corpus, but to my mind it is the best-quality English corpus that is currently

available.

7.4 Software

Allied with the building of annotated corpora is the development of programs for

tagging and parsing, such as the CLAWS tagging suite developed at Lancaster

and the TOSCA tools developed at Nijmegen (which were used for the annotation

of ICE-GB). From the user’s point of view, it is significant that search programs

have become increasingly user-friendly, making linguists less dependent upon

computational expertise. Good examples of user-friendly and yet sophisticated

programs are Mike Scott’s WordSmith Tools and the International Corpus of

English Corpus Utility Program (ICECUP).

7.5 Distribution

of

texts

Another significant development has to do with the forms of distribution of

corpora. I have already mentioned the generosity of the Brown Corpus compilers

in making their corpus available to researchers across the world. As pointed out

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

14

in Section 5, one of the aims in starting ICAME was to compile an archive of

corpora which could be obtained by the research community. The distribution

started as early as 1978 at the Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities at

Bergen.

Initially, the material was made available in the form of magnetic tapes

containing texts and concordances for use with mainframe computers. Also

distributed were texts on diskette and concordances on microfiche. By the end of

1989, after approximately a decade, the number of data sets that had been

distributed amounted to: magnetic tape 390, microfiche 105, diskette 166. The

receivers were a large number of institutions in countries across the world,

including approximately 40 Japanese institutions. Most of the data sets distributed

at this time were texts or concordances for the Brown Corpus, the LOB Corpus,

and the London-Lund Corpus.

Since 1990 the form of distribution has changed radically, and it is now

virtually limited to texts (and programs) on the ICAME CD-ROM, which has

turned out to be much sought after. The available material has been expanded to

include a number of new corpora, both spoken and written, contemporary and

diachronic, corpora of raw texts and parsed corpora. Up-to-date information on

the ICAME archive is found at: http://helmer.aksis.uib.no/icame.html.

As early as the middle of the 1970s electronic texts began to be distributed

by the Oxford Text Archive, which holds a wide variety of texts in English and

other languages. With the increasing interest in the use of electronic texts for

research, other institutions have been established as well, such as the Linguistic

Data Consortium in the United States, which caters especially for computational

linguists and researchers in natural language processing.

The question of copyright continues to be a thorny issue in corpus work.

Corpus workers must abide by the same rules that apply to machine-readable

texts in general. This means that texts cannot be copied and shared among

researchers unless permission has been obtained from copyright holders. Such

permission may be difficult to obtain, and many corpora are therefore not

available outside the institutions where they were compiled. There are, for

example, severe restrictions on the use of the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus

and the Oslo Multilingual Corpus, not because we do not want to share our

material with others, but because we are restricted by our agreement with

copyright holders. An important task for corpus workers is to investigate whether

it is feasible to work out better conditions for the use of machine-readable texts

for non-profit language research.

7.6 New

organisations

The fast increasing interest in the use of corpora has led to the rise of new

organisations catering for corpus workers. Since 1992 there have been

conferences every other year on “Teaching and Language Corpora” (TaLC). We

also have “Practical Applications in Language Corpora” (PALC), which is

arranging its fourth conference at the University of Lodz in Poland in 2003, and

15

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

-1965 1966-

1970

1971-

1975

1976-

1980

1981-

1985

1986-

1990

“Corpus Use and Learning to Translate” (CULT), which had its last conference in

Bertinoro in Italy in 2000. Quite a different group, chiefly consisting of

computational linguists and researchers in natural language processing, have had

a series of annual meetings known as the “Workshop on Very Large Corpora”

(WVLC) since 1994. The different nature of these organisations testifies to the

wide range of uses of corpus studies.

Among other organisations I would like to single out the Japan Association

of English Corpus Studies (JAECS), which is now celebrating its first ten years

and seems to be flourishing, as testified by the number of participants at this

conference, by the activities reported on the JAECS web site, and not least by the

high quality of the contributions to the recent book on English Corpus Linguistics

in Japan (edited by Toshio Saito, Junsaku Nakamura, and Shunji Yamazaki,

2002).

8. Achievements

It is high time to say something about what has been achieved in our corpus

studies. If we had just assembled corpora and formed organisations, we would not

have made much progress. Have we gained new insight into language? Let me

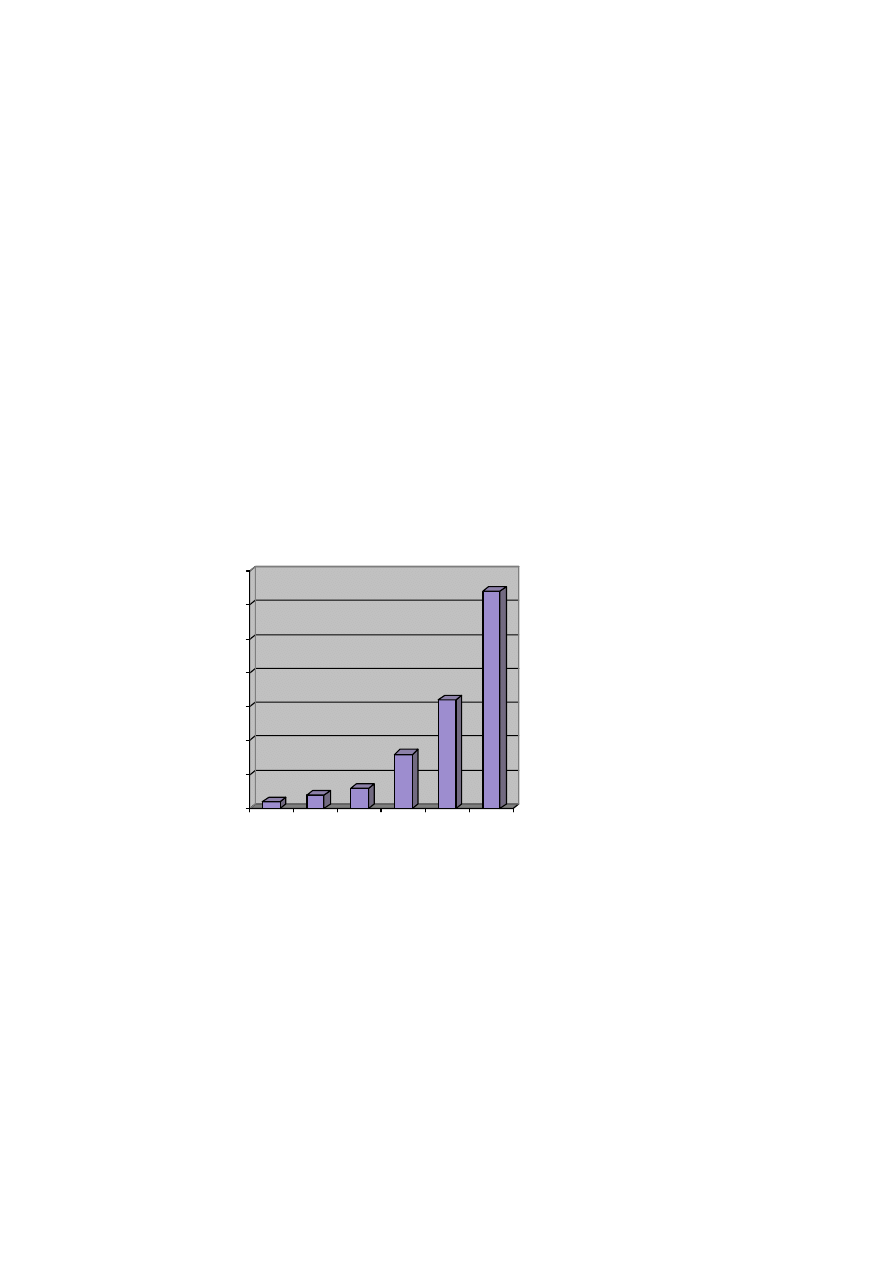

start by saying something about the growth in the number of corpus-based studies.

For a number of years Bengt Altenberg at Lund University in Sweden maintained

a bibliography of publications based on or related to the English text corpora

distributed through ICAME (see the ICAME web site). The pattern up to about

1990 is shown in Figure 1 (based on the figures in Johansson 1991: 312; I have

made no comparable survey since then). Included in these counts are studies of

different kinds: theoretical, descriptive, and applied.

Figure 1. Publications on English text corpora

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

16

Below I will single out some areas where there has been considerable

achievement, and where there is a great potential for further work in the future. I

confine my remarks to studies of present-day English, though I am aware that

there have been great advances in English historical corpus studies, primarily

inspired by Matti Rissanen and his group at the University of Helsinki (and I note

the prominence of historical studies in Saito et al. 2002). Incidentally, to

recognise the growing importance of historical studies, the official name of

ICAME was changed some years ago to the International Computer Archive of

Modern and Medieval English, but the acronym ICAME remains.

8.1 Language

variation

The study of language variation can hardly be undertaken without reference to a

body of language data, and corpora provide a very good basis for such studies.

One important early publication is Tottie and Bäcklund (1986), a collection of

papers examining different aspects of spoken and written English, most of them

based on the LOB Corpus and the London-Lund Corpus. A couple of years later

Douglas Biber published his important and influential book on Variation Across

Speech and Writing (Biber 1988), based on material from the LOB Corpus and

the London-Lund Corpus. We also find monographs dealing with special areas,

such as Tottie (1991), which examines negation in speech as in writing, and

Collins (1991), which deals with the use of cleft sentences in different genres of

speech and writing. On the whole, the study of spoken English has advanced

greatly as a result of the availability of spoken corpora, not least the London-

Lund Corpus.

Another type of variation study where corpus work has been significant is

the comparison of different geographical varieties of English. Many such studies

have used the Brown Corpus and its ‘clones’ (for British English, Australian

English, etc.), e.g. the quantitative comparison of modals in the Brown and LOB

corpora by Junsaku Nakamura (1993). As the new ICE corpora (the International

Corpus of English) become available, we can expect to gain new knowledge

about first- and second-language varieties of English across the world. Studies of

the associated ICLE corpora (International Corpus of Learner English) will yield

new information on English as used by foreign language learners as well as give

new insight into second-language acquisition.

8.2 Lexis

Lexicography is perhaps the area where corpora have had the greatest impact so

far. This is not surprising. There is a long tradition for collecting citations to

support lexicographical work, although the collection has often been biased

towards the unusual (cf. Section 3 above). An important milestone is the Collins

COBUILD English Language Dictionary (1987), which was a breakthrough for

the corpus-based approach in lexicography. In recent years new English

17

dictionaries generally claim that they are corpus-based. The influence of corpora

in lexicography was shown very clearly in many papers at the recent EURALEX

conference in Copenhagen.

The principal tool of the lexicographer is a computer-generated

concordance list. Such lists are very revealing in the study of collocations, i.e.

habitual combinations of words. The notion of collocation is not new, but it has

only become possible to study collocations systematically after large computer

corpora have become available. The significance of collocations has been

emphasised particularly by John Sinclair, who stresses the ‘idiom principle’ in

language use:

The principle of idiom is that a language user has available to him or

her a large number of semi-preconstructed phrases that constitute

single choices, even though they might appear to be analysable into

segments. (Sinclair 1991: 110)

John Sinclair suggests that the idiom principle, rather than being a minor feature

compared with grammar, is “at least as important as grammar in the explanation

of how meaning arises in text” (p. 112). This brings me to my next point.

8.3 Grammar

A large number of corpus-based books and articles on grammar have appeared in

the last couple of decades, but I will confine myself to a couple of important

publications. Through the Survey of English Usage (cf. Section 3), the ground

was prepared for the writing of a new grammar drawing on the material. All the

four authors of A Grammar of Contemporary English (1972)—Randolph Quirk,

Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik—had been involved in the

Survey of English Usage, and this has certainly left its mark in many places in the

grammar. Nevertheless, it is significant that the word corpus does not appear in

the book, except in the context of the discussion of plural forms of Latin

loanwords ending in -us. When the same author team published A Comprehensive

Grammar of the English Language (CGEL) in 1985, it was a different situation.

In the subject index we find numerous references to the classic corpora: the

Brown Corpus, the LOB Corpus, the London-Lund Corpus, and the corpus of the

Survey of English Usage. This can be interpreted as a sign of the breakthrough of

corpus studies.

CGEL is a monumental work and will remain a major resource for English

grammar for years to come. However, in its use of corpus material it can perhaps

best be described as corpus-informed rather than corpus-based. We can see this if

we make a comparison with the new Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written

English (LGSWE, Biber et al. 1999), which seems to be well-known in Japan,

judging by the numerous references in Saito et al. (2002).

In

LGSWE the word corpus appears on almost every page. While CGEL

was a synthesis of the knowledge of English grammar at the time, the aim of

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

18

LGSWE was to re-examine English grammar in the light of a large corpus. This

does not mean that previous work was neglected, but the main emphasis was on

new findings based on new material. The book starts out by presenting the

carefully thought-out structure of the corpus. Throughout the book findings are

reported for four main registers: academic prose, news reportage, fiction, and

conversation. Findings are not just reported, in each case there is an attempt at an

explanation of the patterns observed.

Time does not allow me to go into detail. How does LGSWE compare with

CGEL? LGSWE is certainly less comprehensive, but it contains a lot of

information which cannot be found in CGEL, particularly on quantitative

distributions of grammatical features in the four registers. Of greatest significance

is probably the new insight into the grammar of conversation, which is the topic

of the final chapter in the book. LGSWE certainly does not replace CGEL. Rather,

the two grammar should be seen as complementary.

The lesson I learned in working on LGSWE is how difficult it is to get at

many grammatical features. It is indeed very valuable to have available a large

computer corpus and software tools for analysing the material. Our corpus was

tagged at word class level, but a lot would have been gained if we had been able

to access a syntactically analysed corpus like ICE-GB (cf. Section 7.3), although

this is relatively small. As it was, we had to use a combination of manual and

computational techniques, and some studies had to be based on manual analysis

of a small selection from the corpus. The user of the book is advised to pay

attention to the analysis notes in the book which specify what material was taken

into account in each study.

LGSWE is not the ultimate corpus-based grammar, but it is a start. Some

people will object that the approach is not radical enough. By tagging the corpus

we imposed a set of pre-defined categories, and the results we get will reflect

what we put in. An alternative is to use a corpus-driven approach, in the manner

which is associated particularly with John Sinclair and his followers. This is how

the corpus-driven approach is defined in a recent book:

In a corpus-driven approach the commitment of the linguist is to the

integrity of the data as a whole, and descriptions aim to be

comprehensive with respect to corpus evidence. The corpus, therefore,

is seen as more than a repository of examples to back pre-existing

theories or a probabilistic extension to an already defined system. The

theoretical statements are fully consistent with, and reflect directly,

the evidence provided by the corpus. Indeed, many of the statements

are of a kind that are not usually accessible by any other means than

the inspection of corpus evidence. Examples are normally taken

verbatim, in other words they are not adjusted to fit the predefined

categories of the analyst; recurrent patterns and frequency

distributions are expected to form the basic evidence for linguistic

categories; the absence of a pattern is considered potentially

meaningful. (Tognini-Bonelli 2001: 84)

19

The study of distributional patterns in large corpora has led John Sinclair (1999:

8) to propose a model of language where “the main organising principle of text is

the lexical item, a unit which typically consists of several words and which

permits a considerable amount of variation in its realisation […]. The lexical item

organises both the semantics and the grammar within it, and is not confined by

grammatical unit boundaries.” It is along these lines that Susan Hunston and Gill

Francis formulate their pattern grammar (Hunston and Francis 2000).

It is difficult to predict what grammars in the future will look like, but

there is no doubt that they will be heavily influenced by corpus studies. I will

mention one possible avenue which I have pointed out a few times in the past (e.g.

in Johansson 1998a: 269ff.). Traditionally, there has been a gap between the

study of grammar and lexis. Lexis used to be left largely to the lexicographers,

grammar to the grammarians. Yet there are large areas of overlap. Dictionaries

generally provide some grammatical information, at least part of speech labels

and often much more than that. Grammars regularly contain lists of words that

have particular characteristics, e.g. uncountable nouns or verbs that take

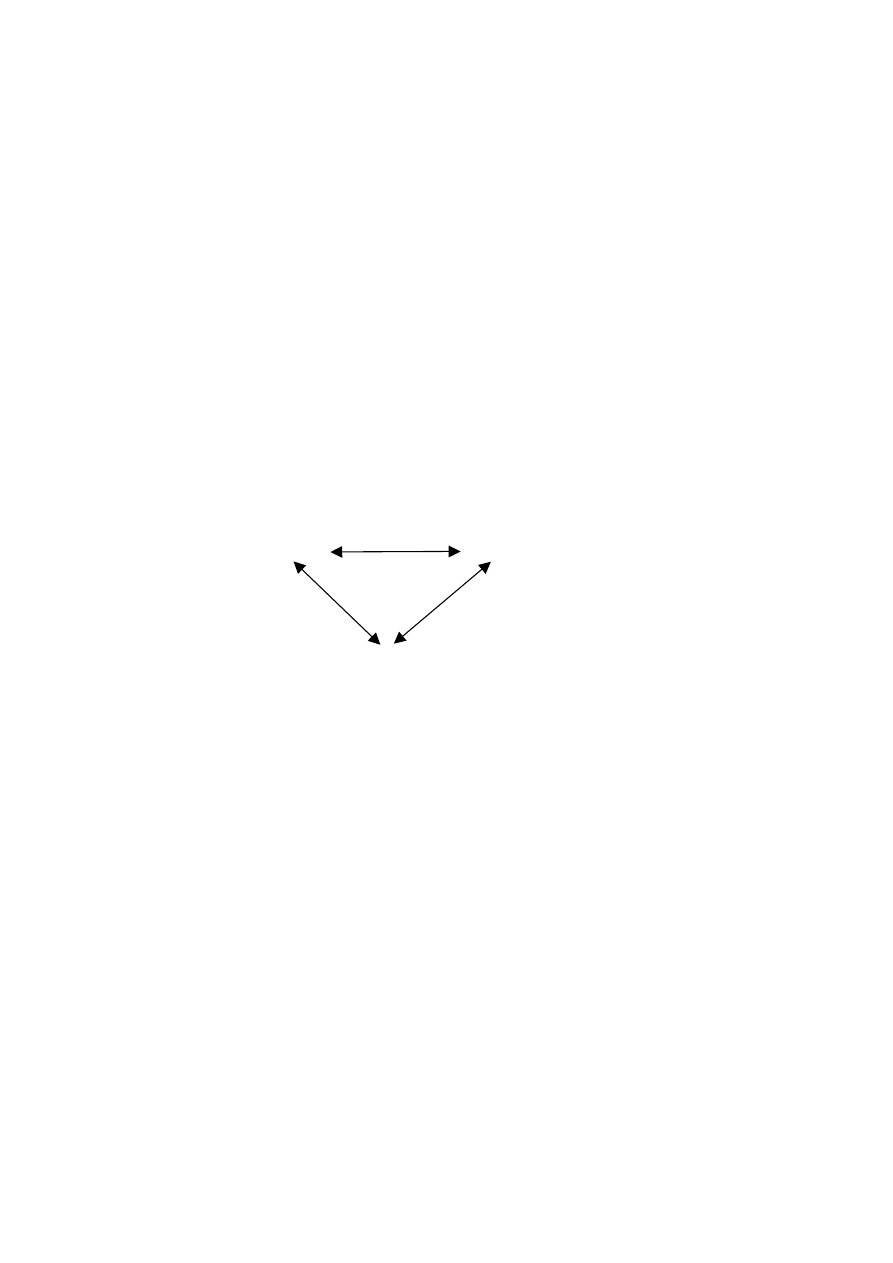

particular types of complements. I would like to see an integrated model with

grammar and lexicon linked to each other and to a corpus (see Figure 2). This

will have to be realised in electronic form, freed from the restrictions of paper

publications. The result will be a coherent language description. To the user,

dictionary and grammar will no longer be separated. They will no longer be

collections of observations and examples out of context, but a guide to language

in use. What I am proposing is long-term project, but I believe it is a goal worth

striving for in the future.

Dictionary

Grammar

Corpus

Figure 2. Dictionary, grammar, and corpus: an integrated model

8.4 Languages

in

contrast

As my last example, I will briefly touch on bilingual and multilingual corpus

studies, an area where there has been a virtual explosion in the last decade or so.

There are many good reasons for studying bilingual and multilingual corpora. As

we wrote in the early stages of our work on the English-Norwegian Parallel

Corpus,

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

20

Language comparison is of great interest in a theoretical as well as an

applied perspective. It reveals what is general and what is language

specific and is therefore important both for the understanding of

language in general and for the study of the individual languages

compared. (Johansson and Hofland 1994: 25)

There are important applications in foreign language teaching, bilingual

lexicography, the training of translators, and natural language processing (see

Véronis 2000).

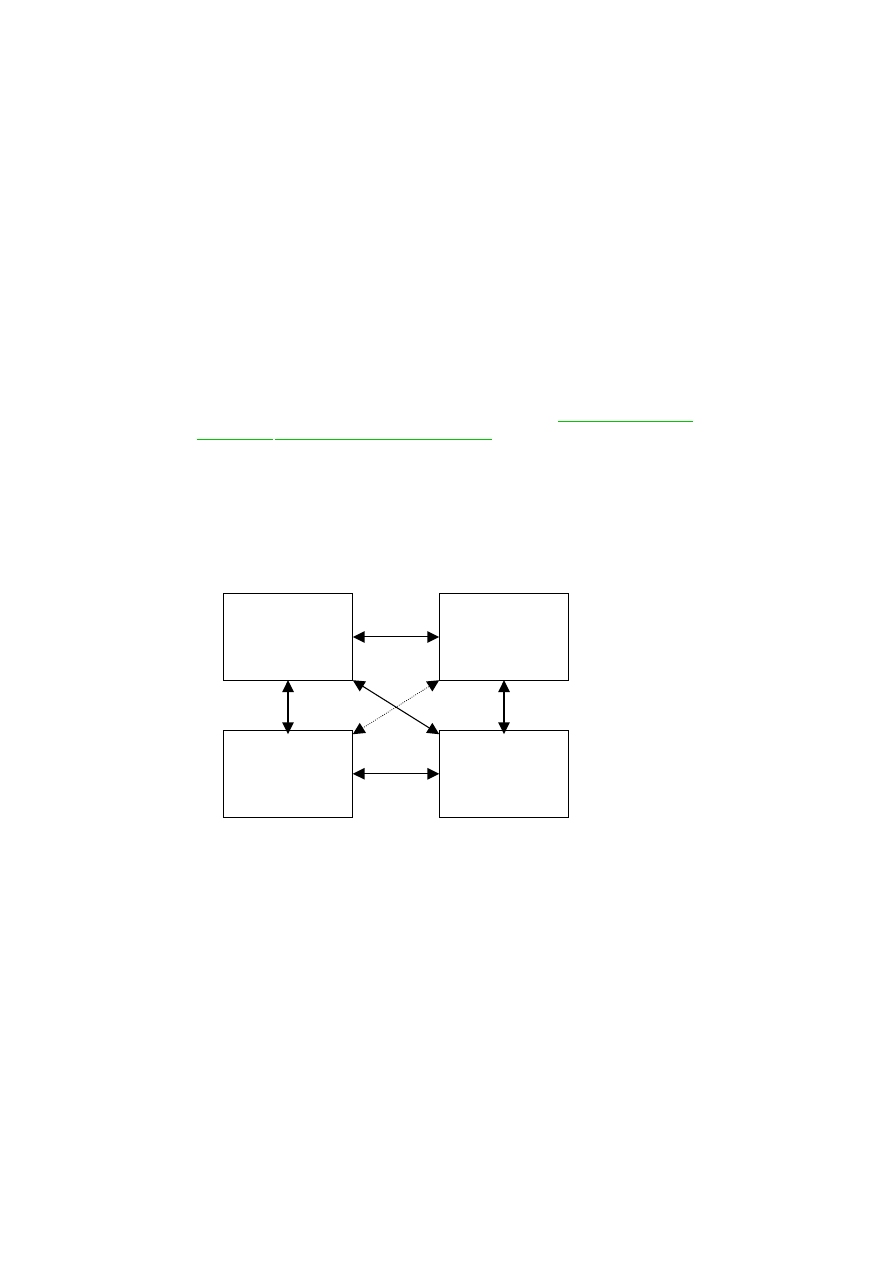

The types of research questions can be seen from the model for the

English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus, which is reproduced as Figure 3. We can

compare:

● original texts in the two languages;

● original texts and translations in either direction;

● original vs. translated texts in each language;

● translated texts across languages.

See further Johansson (1998b) and the following web sites: http://www.hf.uio.no/

iba/prosjekt, http://www.hf.uio.no/german/sprik. From the start with the English-

Norwegian Parallel Corpus, we have expanded our scope to include other

languages, and at present we are focusing on English, German, French, and

Norwegian. As the scope is expanded, so does the range of possible research

questions, and the more general questions can we ask on the nature of language

and translation.

Although there has been a great deal of work recently on bilingual and

multilingual corpora, I believe that this research area is only in a beginning phase,

and much more can be expected in the future.

Figure 3. The structure of the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus

ENGLISH

ORIGINALS

NORWEGIAN

TRANSLATIONS

ENGLISH

TRANSLATIONS

NORWEGIAN

ORIGINALS

21

9.

Prospects for the future

In my talk I have only been able to follow some trends in the development of

corpus studies, and I have presented a view from my own perspective, mainly

focusing on work which I have been involved in personally. It is an almost

impossible task to give a fully satisfactory overview of a field which is

developing so fast. As Graeme Kennedy writes in his introduction to corpus

linguistics,

[…] such is the speed of development and change in corpus

linguistics at the present time that anyone writing about it must be

conscious that it could be easy to produce a Ptolemaic picture of the

field with the world distorted […] (Kennedy 1998: 2)

It is even harder to make predictions for the future, though I have suggested some

avenues ahead.

As we move ahead, we must not forget the lessons from the past. The

transportability of computer corpora has meant that material which it would be

beyond any individual to produce has been put at the disposal of linguists across

the world. Much has been gained by having a common basis of reference and by

subjecting the same material to systematic study from different points of view. It

is my hope that the spirit of cooperation that we found among the corpus pioneers

will not be forgotten, no matter what other changes will follow.

Ten years ago Jan Svartvik used the title “Corpus linguistics comes of

age” in his introduction to Directions in Corpus Linguistics, and he wrote:

Towards the end of the 1980s some of us felt that corpus linguistics

had come of age and should satisfy the criteria for Nobel Symposia:

being a field of great scientific importance and great relevance to

society. (Svartvik 1992: 12)

It is a sign of the recognition both of Jan Svartvik himself and of his field that he

could arrange the first Nobel Symposium on Corpus Linguistics in Stockholm in

1991. In the years since then there have been no indications of old age setting in.

The field is strong and vigorous, not least here in Japan, as far as I can judge. If

corpora are used with care and imagination, I believe that corpus studies have a

bright future.

References

Aarts, Bas (2000) ‘Corpus linguistics, Chomsky and fuzzy tree fragments,’ in Chr.

Mair and M. Hundt (eds.), Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory.

Papers from the Twentieth International Conference on English Language

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

22

Research on Computerized Corpora (ICAME 20), Freiburg im Breisgau

1999. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi. 5–13.

Aarts, Jan and Theo van den Heuvel (1980) ‘The Dutch Computer Corpus Pilot

Project,’ ICAME News 4: 1–8.

Aarts, Jan and Willem Meijs (eds.) (1984) Corpus Linguistics. Recent

Developments in the Use of Computer Corpora in English Language

Research. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Aijmer, Karin and Bengt Altenberg (eds.) (1991) English Corpus Linguistics.

Studies in Honour of Jan Svartvik. London: Longman.

Allén, Sture (1992) ‘Opening address,’ in Svartvik (1992). 1–3.

Biber, Douglas (1988) Variation Across Speech and Writing. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward

Finegan (1999) Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English.

Harlow, Essex: Addison Wesley Longman Ltd.

Chafe, Wallace (1992) ‘The importance of corpus linguistics to understanding the

nature of language,’ in Svartvik (1992). 79–97.

Collins, Peter (1991) Cleft and Pseudo-cleft Constructions in English. London &

New York: Routledge.

Ellegård, Alvar (1978) The Syntactic Structure of English Texts. Gothenburg

Studies in English 43. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Francis, W. Nelson (1982 [1979]) ‘Problems of assembling and computerizing

large corpora,’ in H. Bergenholtz and B. Schaeder (eds.), Empirische

Sprachwissenschaft. Aufbau und Auswertung von Text-Corpora.

Königstein/Ts.: Scriptor. 110–123. Reprinted in Johansson (1982). 7–24.

Francis, W. Nelson (1992) ‘Language corpora B.C.,’ in Svartvik (1992). 17–32.

Francis, W. Nelson and Henry Kučera (1979 [1964, 1971]) Manual of

Information to Accompany a Standard Sample of Present-day Edited

American English, for Use with Digital Computers. Revised edition.

Providence, R.I.: Brown University.

Garside, Roger, Geoffrey Leech, and Geoffrey Sampson (eds.) (1987) The

Computational Analysis of English: A Corpus-based Approach. London:

Longman.

Hunston, Susan and Gill Francis (2000) Pattern Grammar: A Corpus-driven

Approach to the Lexical Grammar of English. Amsterdam & Philadelphia:

Benjamins.

Hymes, D. H. (1972) ‘On communicative competence,’ in J. B. Pride & J.

Holmes (eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings. Harmondsworth:

Penguin Books. 269–293.

ICAME News / ICAME Journal. Computers in English Linguistics. Bergen:

Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities.

Johansson, Stig (ed.) (1982) Computer Corpora in English Language Research.

Bergen: Norwegian Computing Centre for the Humanities.

Johansson, Stig (1985) ‘Grammatical tagging and total accountability,’ in S.

Bäckman and G. Kjellmer (eds.), Papers on Language and Literature

23

Presented to Alvar Ellegård and Erik Frykman, Gothenburg Studies in

English 60. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. 208–219.

——— (1991) ‘Times change, and so do corpora,’ in Aijmer and Altenberg

(1991). London: Longman. 305–314.

——— (1992) ‘The cloning of Brown,’ in A. W. Mackie, T. K. McAuley, and C.

Simmons, For Henry Kučera. Studies in Slavic Philology and

Computational Linguistics. Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Publications.

203–215.

——— (1998a) ‘On computer corpora in contrastive linguistics,’ in W. R.

Cooper (ed.), Compare or Contrast? Current issues in Cross-language

Research. Tampere English Studies 6. Tampere: University of Tampere.

259–289.

——— (1998b) ‘On the role of corpora in cross-linguistic research,’ in S.

Johansson and S. Oksefjell (eds.), Corpora and Cross-linguistic Research:

Theory, Method, and Case Studies. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

3–24.

——— (2001) ‘Grammar across speech and writing,’ in W. Vagle and K.

Wikberg (eds.), New Directions in Nordic Text Linguistics and Discourse

Analysis: Methodological issues. Oslo: Novus. 45–58.

Johansson, Stig and Knut Hofland (1994) ‘Towards an English-Norwegian

parallel corpus,’ in U. Fries, G. Tottie, and P. Schneider (eds.), Creating

and Using English Language Corpora. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA:

Rodopi. 25–37.

Johansson, Stig, Eric Atwell, Roger Garside and Geoffrey Leech (1986) The

Tagged LOB Corpus. Users’ Manual. Bergen: Norwegian Computing

Centre for the Humanities.

Johansson, Stig, Geoffrey Leech, and Helen Goodluck (1978) Manual of

Information to Accompany the Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen Corpus of British

English, for Use with Digital Computers. Oslo: Department of English,

University of Oslo.

Kennedy, Graeme (1998) Introduction to Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman.

Kytö, Merja, Ossi Ihalainen, and Matti Rissanen (eds.) (1988) Corpus Linguistics

Hard and Soft. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Murray, K.M. Elisabeth (1979) Caught in the Web of Words. James Murray and

the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nakamura, Junsaku (1993) ‘Quantitative comparison of modals in the Brown and

LOB corpora,’ ICAME Journal 17: 29–48.

Nelson, Gerald, Sean Wallis, and Bas Aarts (2002) Exploring Natural Language.

Working with the British Component of the International Corpus of

English. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Quirk, Randolph (1960) ‘Towards a description of English usage,’ in

Transactions of the Philological Society, 40-61. (Revised and reprinted as

‘The Survey of English Usage’ in Quirk 1968: 167–183)

——— (1968) Essays on the English Language: Medieval and Modern. London:

Longman.

Corpus linguistics—past, present, future: A view from Oslo

Stig

Johansson

24

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik (1972) A

Grammar of Contemporary English. London: Longman.

——— (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London:

Longman.

Saito, Toshio, Junsaku Nakamura, and Shunji Yamazaki (eds.) (2002) English

Corpus Linguistics in Japan. Amsterdam & Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Sigurd, Bengt (1980) ‘Om datorns effekter på språkvetenskap,’ in Skrifter for

Anvendt og Matematisk Lingvistikk 6, Department of Applied and

Mathematical Linguistics, University of Copenhagen.

Sinclair. John (1982) ‘Reflections on computer corpora in English language

research,’ in Johansson (1982). 1–6.

——— (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

——— (1999) ‘The computer, the corpus and the theory of language,’ in G.

Azzaro and M. Ulrych (eds.), Transiti linguistici e culturali. Atti del XVIII

Congresso nazionale dell’A.I.A. Trieste: E.U.T. 1–15.

Svartvik, Jan (1982) ‘Introduction,’ in J. Svartvik, M. Eeg-Olofsson, O.

Forsheden, B. Oreström, and C. Thavenius, Survey of Spoken English:

Report on Research 1975-81. Lund Studies in English 63. Lund CWK

Gleerup. 9–13.

Svartvik, Jan (ed.) (1992) Directions in Corpus Linguistics. Proceedings of Nobel

Symposium 82, Stockholm, 4-8 August 1991. Berlin & New York. Mouton

de Gruyter.

Svartvik, Jan and Randolph Quirk (eds.) (1980) A Corpus of English

Conversation. Lund Studies in English 56. Lund CWK Gleerup.

Tognini-Bonelli, Elena (2001) Corpus Linguistics at Work. Studies in Corpus

Linguistics 6. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Tottie, Gunnel (1991) Negation in English Speech and Writing. A Study in

Variation. San Diego: Academic Press.

Tottie, Gunnel and Ingegerd Bäcklund (eds). (1986) English in Speech and

Writing: A Symposium. Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia 60. Stockholm:

Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Véronis, Jean (ed.) (2000) Parallel Text Processing. Alignment and Use of

Translation Corpora. Text, Speech and Technology 13. Dordrecht etc.:

Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Web references

ICAME: http://helmer.aksis.uib.no/icame.html

The English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus: http://www.hf.uio.no/iba/prosjekt

The Oslo Multilingual Corpus: http://www.hf.uio.no/german/sprik

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Telling Truth to Power MI Past, Present, Future

japanese keiretsu past present future

need analysis past present future review

UFO,s Past, present and future

Education Past Present and Futur

Sajavaara, K Contrastive Linguistics Past and Present and a Communicative Approach

quiz past and future

View from the Bridge, A General Analysis

present, future, passe simple cw fr

Joan D Vinge View From A Height

SLOW DAZZLE The View From the Floor CD ( MSR34, Misra)msr34

The Blaster Worm The View from 10,000 feet

The View from Endless Scarp Marta Randall

Is Hip Hop Dead The Past, Present, and Mickey Hess

więcej podobnych podstron