J

. Child Psychol. Psychiat. Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 465–477, 1999

Cambridge University Press

' 1999 Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved

0021–9630

\99 $15.00j0.00

Avoidant

\Ambivalent Attachment Style as a Mediator between Abusive

Childhood Experiences and Adult Relationship Difficulties

Gerard McCarthy and Alan Taylor

Medical Research Council’s Child Psychiatry Unit, Institute of Psychiatry, London, U.K.

The role of attachment style, self-esteem, and relationship attributions as possible mediators

between abusive childhood experiences and difficulties in establishing supportive love

relationships in adulthood were investigated in a sample of women known to be at risk of

experiencing relationship problems. Measures of child abuse, the quality of love relation-

ships, and the three potential mediators were made concurrently in adulthood. Participants

who had experienced child abuse were found to be six times more likely to be experiencing

difficulties in the domain of adult love relationships than those who had not. Self-esteem and

relationship attributions were not found to be related to child abuse. When both child abuse

and avoidant

\ambivalent attachment style were considered together avoidant\ambivalent

attachment style, but not child abuse, was found to be related to relationship difficulties.

These findings indicate that avoidant

\ambivalent attachment style, but not self-esteem and

relationship attributions, is a mediating factor in the route from child abuse to adult

relationship abilities.

Keywords :

Child abuse, adult love relationships, mediators, avoidant

\ambivalent attach-

ment style.

Abbreviations :

A

\C: avoidant-resistant; APFA: Adult Personality Functioning Assess-

ment ; BDI : Beck Depression Inventory ; CSA : child sexual abuse ; ICC : interclass

correlation ; RAM : Relationship Attribution Measure ; RSD : Rosenberg self-derogation

scale ; SESS : Self-Evaluation and Social Support Instrument.

Introduction

A number of studies have shown that abusive child-

hood experiences are related to difficulties in establishing

supportive cohabiting relationships in adulthood. Studies

into the long-term outcome of childhood sexual abuse

have found increased rates of interpersonal difficulties

and sexual problems (Beitchman, Zucker, & Hood, 1992 ;

Finkelhor, 1983 ; Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith,

1990 ; Mullen, Martin, Anderson, Romans, & Herbison,

1994). Children who have experienced physical abuse or

harsh and

\or neglectful parenting have also been found

to experience difficulties in the domain of intimate adult

relationships (Andrews & Brown, 1988 ; Birtchnell, 1993 ;

Brown & Moran, 1994 ; Malinosky-Rummell & Hansen,

1993 ; Quinton, Pickles, Maughan, & Rutter, 1993). These

findings are important because research has established

that difficulties in close relationships, such as marital

discord and lack of support, are related both to the

development of emotional and behavioural problems in

the next generation (Emery, 1982 ; Farrington, 1995 ;

Requests for reprints to : Dr Gerard McCarthy, Child and

Adolescent Service, Weston Clinic, 4a Beaconsfield Rd,

Weston-super-Mare, BS23 1YE, U.K.

Jouriles, Piffner, & O’Leary, 1988 ; Patterson, 1982) and

to the development of mental health problems in adult

life (Brown & Harris, 1978 ; Quinton & Rutter, 1988 ;

Sampson & Laub, 1993).

As the evidence for a link between abusive childhood

experiences and adult relationship difficulties grows so

the need to understand how this effect occurs becomes

more urgent. A major issue for all concerned with the

well-being of children and adolescents is how to intervene

to prevent them going on to experience difficulties in

adulthood. However, little is known about the psycho-

logical processes underlying this association nor about

the role cognitive-affective mechanisms may play in

mediating the effects of abusive early experiences. A

better understanding of the precise mechanisms through

which negative childhood experiences exert their effect on

later psychosocial functioning is likely to have impli-

cations for methods of intervention to prevent the

development of later problems.

At present, attempts to delineate the role of specific

processes in mediating developmental continuities be-

tween abusive childhood experiences and adulthood are

hampered by the nature of the evidence available. Much

of this evidence comes from either short-term longi-

tudinal studies in childhood or from cross-sectional

retrospective studies undertaken in adulthood (Maughan

& McCarthy, 1997). Researchers investigating the link

between child abuse and adult depression have recently

465

466

G. M

CARTHY and A. TAYLOR

begun to undertake direct tests of the role of specific

mediating factors. This work has shown that stable

negative characteristics of the self may mediate the

association between child abuse and adult depression. In

particular two mediating factors have been identified.

These are bodily shame (Andrews, 1995) and charactero-

logical self-blame (Andrews & Brewin, 1990 ; Gold, 1986).

More recently Andrews (1997) has shown that bodily

shame also acts as a mediator between child abuse and

bulimia in a community sample of young women.

The present study attempts to build on this small body

of research to identify specific psychological factors that

mediate links between child abuse and adverse psycho-

logical functioning in adulthood. However, it differs in

two principal ways from the studies by Andrews and her

colleagues. First, rather than focusing on a particular

psychiatric outcome such as depression or bulimia, we

aimed to investigate psychological processes that mediate

the link between child abuse and the quality of adult love

relationships. As noted above, adult relationship abilities

are hypothesised to be one of the pathways by which

adverse early experiences lead to increased risk of

psychopathology in adult life. Second, rather than testing

the role of a single mediating factor such as self-esteem,

this study aimed to investigate the role of a number of

potential mediators. In particular, attachment style,

relationship attributions, and self-esteem were investi-

gated as possible mediating factors between abusive

experiences in childhood and later difficulties in the

domain of adult love relationships in a sample of adult

women.

Attachment Style

According to Bowlby’s theory of attachment (Bowlby,

1969, 1973, 1980) children develop cognitive

\affective

representations or internal working models of their

experiences in their attachment relationships. These are

hypothesised to provide a model about how close

relationships typically proceed and they are thought to

influence the quality of later love relationships (Bowlby,

1979, 1988 ; Crowell & Treboux, 1995). Indeed, a central

tenet of attachment theory is ‘‘ that parent–child relation-

ships are prototypes of later love relationships ’’ (Crowell

& Treboux, 1995, p. 296). Until recently, internal working

models have mainly been investigated in the context of

infants’ relationships with their principal caregivers,

where they are inferred on the basis of infant’s behaviour

in separation-reunion procedures (Ainsworth, Blehar,

Waters, & Wall, 1978). New methods have now been

developed to assess older children’s internal working

models of attachment (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985)

and adult’s representations of their childhood experiences

with parents (Main, 1991). At the same time, social and

clinical psychologists have begun to investigate the role of

working models of attachment or attachment styles

in adult romantic relationships (Collins & Read, 1990 ;

Hazan & Shaver, 1987). However, although there are

growing literatures on both the relationship between

maltreatment and the development of insecure attach-

ment relationships in childhood and the relationship

between attachment styles and the quality of love

relationships in adulthood, little is known about the role

internal working models may play in mediating continu-

ities in relationship functioning between childhood and

adulthood.

Investigations of attachment in maltreated children

have shown high levels of insecure (avoidant and am-

bivalent) attachments (Crittenden, 1988 ; Egeland &

Sroufe, 1981 ; Schneider-Rosen, Braunwald, Carlson, &

Cicchetti, 1985). In an inner-city disadvantaged sample,

Egeland and Sroufe (1981) found a specific association

between child abuse and the development of avoidant

attachment although subsequent investigations have not

replicated this finding. More recent research has shown

high levels of atypical attachment patterns that do not fit

smoothly into Ainsworth et al.’s (1978) traditional A-B-C

classification scheme (Main & Soloman, 1986). Critten-

den (1988) found that most maltreated children in her

sample could be classified as having avoidant-ambivalent

(A

\C) patterns of attachment and Carlson, Cicchetti,

Barnett, and Braunwald (1989) found that over 80 % of

maltreated infants had disorganized

\disoriented attach-

ments (Main & Soloman, 1986). Lynch and Cicchetti

(1991) have demonstrated that distortions in maltreated

children’s mental representations of attachment may

persist into the preadolescent years. They found that

30 % of maltreated children between the ages of 7 and 13

years reported having confused patterns of relatedness to

their mothers.

Recent work on adult love relationships has shown

that adult attachment style is associated with the quality

of these relationships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987 ; Shaver &

Hazan, 1993). Studies have demonstrated that attach-

ment style is related to levels of satisfaction, commitment,

and love and trust in the relationship (Collins & Reed,

1990 ; Davis, Kirkpatrick, Levy, & O’Hearn, 1994 ;

Mikulincer & Erev, 1991 ; Simpson, 1990) and with

observed levels of self-disclosure and emotional support

(Mikulincer & Nachshon, 1991 ; Simpson, Rholes, &

Nelligan, 1992). Secure attachment style is associated

with a desire for intimate relationships, and within

relationships secure adults seek a balance of closeness

and autonomy and are comfortable with feelings of

dependency. Anxious-ambivalent attachment style is

characterised by a desire for close relationships, but

fear of rejection may lead ambivalent adults to seek

extreme forms of intimacy and lower levels of autonomy.

Avoidant attachment style is associated with a need

to maintain distance and avoidant adults are thought

to feel uncomfortable with feelings of intimacy and

dependency (Shaver & Hazan, 1993). Bartholomew

(1990 ; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) has further

differentiated the avoidant style into a fearful avoidant

pattern and a dismissing avoidant pattern. Although

both types share a negative view of others, dismissing

avoidants have a positive view of self, whereas fearful

avoidants also have a negative view of self. Fearful

avoidant attachment style is known to be related to

a number of high-risk environments such as having

problem drinking parents (Brennan, Shaver, & Tobey,

1991) and being the victim of incestuous abuse

(Alexander, 1993). A number of studies have also

demonstrated that retrospective accounts of childhood

relationships with parents are related in theoretically

meaningful ways with adult attachment styles (Shaver &

467

AVOIDANT

\AMBIVALENT ATTACHMENT STYLE

Hazan, 1993). However, at present empirical investi-

gations into the role attachment representations may

play in mediating developmental continuities between

childhood adversity and the quality of adult love

relationships have yet to be undertaken.

Relationship Attributions

There are two main reasons for thinking that attribu-

tional processes may play a role in mediating continuities

between childhood experiences and later relationship

difficulties. First, research by Dodge and his colleagues

has demonstrated that children who have been physically

abused and harshly parented tend to acquire deviant

patterns of processing social information and that these

predict the development of later aggressive behaviour

(Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990 ; Dodge, Pettit, Bates, &

Valente, 1995 ; Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992). In

particular, physically abused children acquired a bias to

over-attribute hostile intent to others’ behaviour. Conse-

quently, children who have experienced physical abuse in

childhood may be at increased risk of developing mal-

adaptive attributional processes that, if carried into later

close relationships, may lead to difficulties in this domain.

For example, children who have experienced harsh

parenting and deliberate acts of physical or emotional

cruelty may be at increased risk of interpreting future

negative partner behaviour in close relationships as being

intentionally motivated, and therefore deserving of blame

and retaliation.

Second, a number of studies have demonstrated that

the attributions that partners make for relationship events

are related to marital satisfaction (Baucom, 1987 ; Brad-

bury & Fincham, 1990). Distressed partners have been

found to make causal and responsibility attributions that

accentuate the impact of negative events. Causal attri-

butions concern the explanations a partner makes for the

occurrence of a relationship event and responsibility

attributions deal with the accountability or answerability

for the event (Bradbury & Fincham, 1990). Researchers

have found that the attributions partners make for

relationship events are related to behaviour in adult love

relationships (Bradbury, Beach, Fincham, & Nelson,

1996 ; Bradbury & Fincham, 1992). Husbands who are

physically violent to their wives have also been shown to

be more likely than nonviolent husbands to attribute

negative intentions, selfish motivation, and blame to the

wife (Holtzworth-Munroe, 1992 ; Holtzworth-Munroe &

Anglin, 1991 ; Holtzworth-Monroe & Hutchinson, 1993).

Whereas current maladaptive attributional processes

may be a product of being in an unhappy current

relationship, it is also possible that maladaptive attri-

butional processes play a causal role in bringing about

problems in intimate relationships (Bradbury & Fincham,

1992). Indeed, maladaptive attributional processes may

pre-date the present relationship altogether and may have

their origins in an earlier developmental period. Recently,

researchers have begun to investigate associations be-

tween child abuse and maladaptive attributional pro-

cesses in adulthood. Gold (1986) found evidence of

greater dispositional blame for hypothetical bad events in

people who reported having been sexually victimised in

childhood. More recently, Andrews (1992) found that

retrospective reports of repeated physical and sexual

abuse in childhood were associated with a tendency for

women in violent marriages to blame their own characters

for the marital violence. Following on from these studies

we aimed to investigate the role causal and responsibility

attributions may play in mediating links between child

abuse and difficulties in adult love relationships.

Self

-esteem

Many theorists have argued that difficulties in making

close adult relationships derive from negative thoughts

and feelings about the self (Erikson, 1963 ; Kohut, 1977 ;

Sullivan, 1953). The idea that low self-esteem may

mediate developmental continuities between adverse

childhood experiences and difficulties in adulthood comes

from a number of areas.

First, research shows that negative childhood experi-

ences are related to impairments in various aspects of

children’s sense of self. Maltreated toddlers have been

shown to have more negative responses to visual self-

recognition experiments, and to experience more diffi-

culties in dealing with issues to do with autonomy and

exploration, than comparison children (Egeland &

Sroufe, 1981 ; Schneider-Rosen & Cicchetti, 1984). Older

maltreated children describe themselves as being less

competent and accepted than comparison children and

appear to have feelings of generalised low self-worth

(Vondra, Barnett, & Cicchetti, 1989). Also, in a series of

studies, Sroufe and his colleagues have shown that the

quality of care children receive in their early relationships

with parents is related to a number of measures of

children’s subsequent sense of self (Sroufe, 1986, 1989).

Children who received more sensitive care as infants tend

to have higher self-esteem, to have greater ego strength,

to be more ego resilient, to be more independent and

resourceful, and to have more elaborate and complex

fantasy play than children who received less sensitive care

(Arend, Gove, & Sroufe, 1979 ; Egeland & Sroufe, 1981 ;

Matas, Arend, & Sroufe, 1978 ; D. Rosenberg, 1984 ;

Sroufe, 1983 ; Waters, Wippman, & Sroufe, 1979).

Second, whereas these studies show how negative early

experiences can adversely affect the development of self-

esteem in childhood, a series of studies by Brown and his

colleagues suggest that these processes may be involved in

mediating continuities between lack of affectionate care

in childhood, negativity in current close relationships,

and vulnerability to depression (Andrews & Brown, 1988,

1993 ; Brown, Bifulco, & Andrews, 1990 ; Brown, Bifulco,

Veiel, & Andrews, 1990 ; Brown & Moran, 1994). Also of

importance here is evidence showing that the protective

effects of successful coping and positive experiences may

exert their effect on the developmental process by

bringing about an increase in self-confidence and self-

esteem (Rutter, 1989).

The Nature of Mediating Variables

Given the lack of research in this area the main aim of

this study was to carry out a preliminary investigation

into the role of these three potential mediating factors in

the link between abusive childhood experiences and later

problems in making supportive love relationships. An

468

G. M

CARTHY and A. TAYLOR

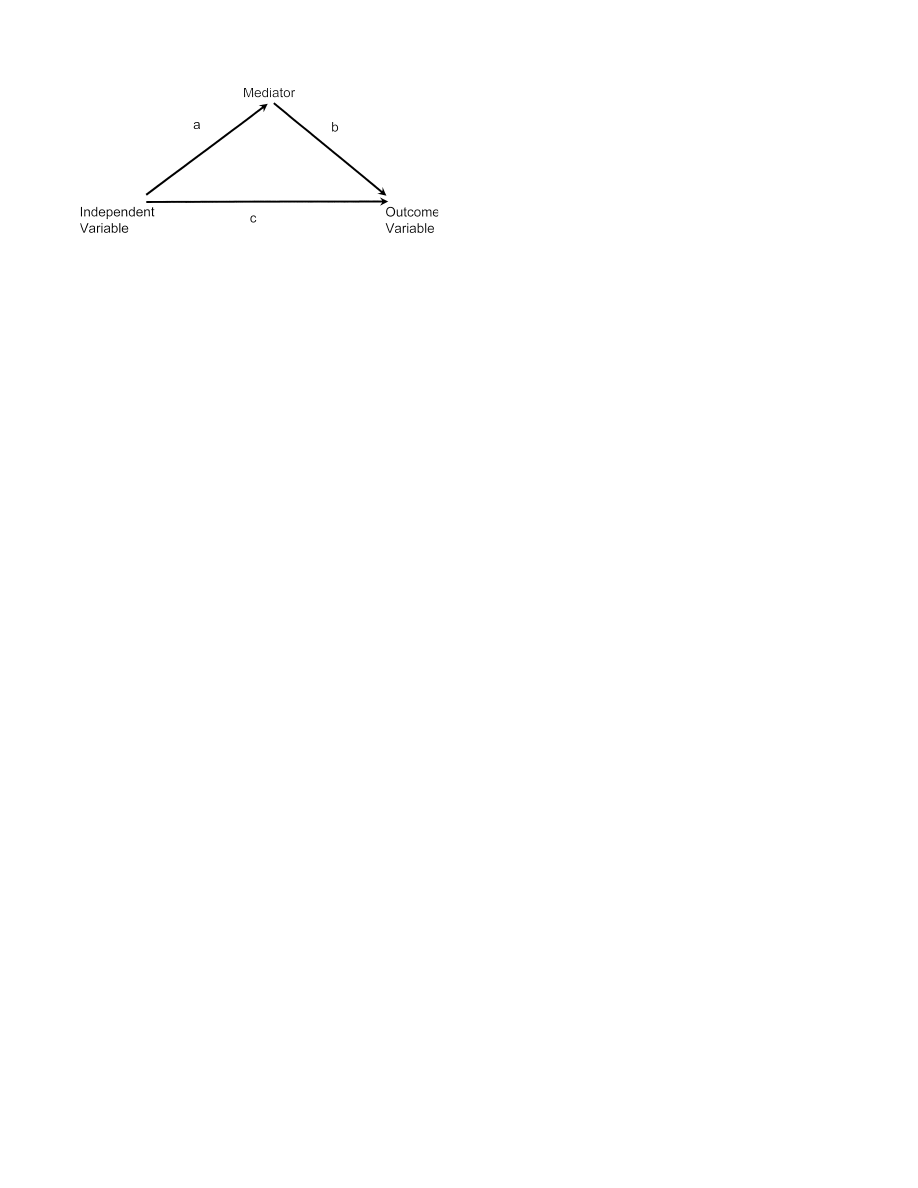

Figure 1.

Mediator model.

important limitation of the present study was that

measures of the three potential mediators were made in

adulthood rather than in childhood, concurrently with

measures of functioning in the domain of adult love

relationships. Ideally, prospective longitudinal studies

are required to provide a more powerful test of potential

mediating variables. However, until suitable prospec-

tively studied samples are available, much can be learned

from retrospective accounts of childhood experiences.

Prospective research in this area is also costly and time

consuming. In light of this it seemed reasonable to use the

present study to explore as far as possible potential

mediators that might profitably be incorporated in future

prospective work.

In order to test the value of our hypothesised medi-

ators, we used the framework outlined by Baron and

Kenny (1986) to guide our analyses. According to Baron

and Kenny a variable can be thought of as functioning as

a mediator if it meets the following conditions (see Fig.

1) : (1) if variations in levels of the independent variable,

in this case child abuse, significantly account for vari-

ations in the presumed mediator (Path A) ; (2) if variations

in the proposed mediator significantly account for vari-

ations in the dependent variable, in this case relationship

quality (Path B) ; (3) when paths (A) and (B) are

controlled, a previously significant relation between the

independent variable (child abuse) and the dependent

variable (relationship quality) is no longer significant.

From a theoretical perspective, when path C is reduced to

zero this provides strong evidence for a single dominant

mediator, whereas a significant but less complete re-

duction in the residual path C demonstrates that a given

variable plays an important role in mediating an effect.

Research has also shown that abusive childhood

experiences are often associated with a range of other

negative childhood experiences such as lack of parental

warmth and involvement and poor family functioning

(Bifulco, Brown, & Adler, 1991 ; Fergusson, Lynskey, &

Horwood, 1996 ; Mullen et al., 1993). This raises the

possibility that the apparent correlation between child

abuse and adverse psychosocial functioning in adult-

hood may account for the background factors that pre-

dispose to child abuse and not the abuse itself (Mullen

et al., 1993 ; Paradise, Rose, Sleeper, & Nathanson, 1994).

Indeed, there are a number of reports that raise the

possibility that poor family functioning may account for

much of the variance in the outcomes of child sexual

abuse victims (Fromouth, 1986 ; Harter, Alexander, &

Neimeyer, 1998 ; Wyatt & Mickey, 1987). Recently,

Mullen and his colleagues attempted to disentangle the

particular effects of child sexual abuse (CSA) from a

number of other negative childhood experiences (Mullen

et al., 1993). They found that while a number of other

factors also related to psychosocial difficulties in adult-

hood, CSA continued to have a direct negative impact

when these factors were controlled for. Results from the

Christchurch Health and Development Study have con-

firmed this finding (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey,

1996). In order to address these issues a high-risk group

of subjects was used, all of whom had experienced poor

parenting in childhood. This enabled us to investigate

specific processes that may contribute to the impact of

child abuse on adult relationship difficulties.

The main aim of the study was therefore to investigate

whether each of the potential mediators met the con-

ditions outlined for judging whether a variable can be

said to function as a mediator. In particular the study

aimed to test whether child abuse was significantly related

to the three mediating variables (path A), whether the

mediating variables were significantly related to the

quality of adult love relationships (path B), and whether,

when paths A and B were controlled, a previously

significant relationship between child abuse and relation-

ship problems became nonsignificant. Such a situation

would provide evidence that a variable functions as a

mediator between child abuse and adult relationship

problems.

Method

Participants

Forty women known to have experienced poor parenting in

childhood took part in the study. The sample was mainly drawn

from a number of previous longitudinal follow-up studies of

children living in inner-city London (Champion, Goodall, &

Rutter, 1995 ; Maughan & Hagell, 1996 ; Quinton et al., 1993).

During these studies participants had been interviewed about

their childhood experiences and this information was used to

establish a sample of women all of whom had experienced poor

parent–child relationships. A total of 44 women were identified

who met the criterion for having experienced poor parenting in

childhood, described in more detail below, but we were not able

to trace the current whereabouts of 5 of them. The remainder

(N

l 39) were contacted by letter to explain the purpose of the

new study and to ask whether they would agree to participate

and 5 (13 %) women refused to take part. The 34 women who

agreed to take part were interviewed in their homes. We felt it

was necessary to try to supplement the sample in order to

increase the number of cases available for statistical analyses. In

order to do this a further sample of women were recruited from

an inner-city general practice in South London. A total of 18

women from the general practice were interviewed and 6 were

found to meet the criteria for inclusion in the study outlined

below.

The average age of the women was 35

n7 and ages ranged from

25 to 42 years. Twenty-nine of the women were currently in a

cohabitation of at least 6 months duration ; 11 were not

currently cohabiting. Twenty-one of the women were currently

married and 10 were divorced or separated.

Measures

Childhood experiences

. Adults were interviewed about their

childhood experiences using a nonscheduled standardised in-

terview (Brown & Rutter, 1966). The interview included detailed

assessments of the quality of parent–child relationships. All of

469

AVOIDANT

\AMBIVALENT ATTACHMENT STYLE

the women reported having experienced a poor relationship

with one of their parents. This was defined as having experienced

any two of the following three indicators in childhood or

adolescence : (1) little or no warmth, (2) harsh or lax discipline,

(3) little or no communication or involvement in activities.

The women were also questioned in detail about abusive

experiences in childhood. Abuse in childhood was defined as

that occurring before the age of 16 years.

(1) Sexual abuse was defined as that involving direct physical

contact of the sexual parts. Willing sexual contact with

nonrelated peers in the teenage years was excluded. These

criteria are similar to those used in other studies that have

examined the relationship between childhood sexual

abuse and adult psychosocial functioning (Andrews,

1995 ; Andrews & Brown, 1988 ; Bifulco, Brown, &

Harris, 1994).

(2) Physical abuse was defined as repeated acts of violence by

a parent towards the child and included acts such as being

punched, burnt, kicked, hit with an instrument, or being

tied up.

(3) Emotional abuse referred to situations where the

parent(s) expressed marked negative feelings toward the

child. This included expressions of hostility or scape-

goating of the child. The hostile behaviour was required

to be persistent over time and personally focused on the

child.

Attachment style

. Attachment style was assessed using the

Hazan and Shaver (1987) adult attachment questionnaire. This

is a standard procedure for measuring adult attachment style.

In the first part subjects were given the three Hazan and Shaver

descriptions of attachment styles and asked to rate on a 7-point

scale (1

l disagree strongly and 7 l agree strongly), how much

they agreed or disagreed with each style as a description of the

way they generally are in love relationships. For example, the

secure prototype reads as follows : ‘‘ I find it relatively easy to get

close to others and am comfortable depending on them. I don’t

often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting

too close to me ’’. The avoidant prototype reads : ‘‘ I am some-

what uncomfortable being close to others ; I find it difficult to

trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on

them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love

partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable

being ’’. The ambivalent prototype reads ; ‘‘ I find that others are

reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my

partner doesn’t really love me or want to stay with me. I want

to get very close to my partner, and this some times scares

people away ’’. In the second part subjects were asked to choose

the attachment style that best described the way they typically

feel in romantic relationships. In our analyses we have focused

on the attachment scales rather than the discrete attachment

categories, to capitalise on the advantages of dimensional

analysis (Collins & Read, 1990). First, a limitation of discrete

measures is that inevitably some members represent the

category ‘‘ better ’’ than others. Second, dimensional scales can

help to retain information lost through a forced classification

procedure, especially where individuals report high scores on

two or more of the attachment scales. Third, the use of scale

measures is also useful in terms of statistical power when sample

sizes are small, as in our study (Fergusson & Horwood, 1995).

In particular we have focused on the avoidant and ambivalent

scales, as these were most likely to be involved in mediating

developmental continuities between child abuse and adult

relationship abilities.

Self

-esteem. This was assessed using the Rosenberg self-

esteem scale (M. Rosenberg, 1965). This is a 10-item Gutman

scale tapping global positive and negative attitudes to the self. It

has been used with a wide variety of subject populations and

shows good test–retest reliability (r

l n85). There is evidence

suggesting that this scale reflects two independent aspects of

self-esteem, tapped by the positively and negatively worded

items (Kaplan & Pokorny, 1969 ; Kohn & Schooler,

1983 ; Zeller & Carmaines, 1980) and that only the negative

measure is linked to childhood adversity and to negative

psychosocial outcomes (Andrews & Brown, 1993 ; Kaplan

& Pokorny, 1969). Therefore only the score based on the

negative items (range 5 to 20) was used in the following

analyses. Following Kaplan and Pokorny (1969) and Andrews

and Brown (1993) we refer to the negative measure as the

Rosenberg self-derogation (RSD) scale.

Attributions

. The procedure used in this study was a modi-

fication of the Relationship Attribution Measure (RAM)

developed by Fincham and Bradbury (1992). This measure has

high internal consistency and test–retest reliability. In the RAM

subjects are asked to imagine six hypothetical negative partner

behaviours and after each one they are asked to rate their

agreement with six statements on a 6-point scale. Subjects make

the ratings after imagining that the behaviour has just occurred

in their relationship. Each scale point is labelled ranging from

disagree strongly to agree strongly. The first three statements

are used to assess three different types of causal attributions.

These are the extent to which the cause rested with the partner

(locus), is likely to change (stability), and affects other areas of

the relationship (globality). The second three statements are

used to assess partner intent, motivation, and blame.

In the procedure used here subjects were asked to think about

the most important love relationships they had been involved

in. Then each scenario was read out by the interviewer and the

subject was asked to imagine themselves in the hypothetical

situation. After this the subject was asked to rate their

agreement with the six attribution statements from the RAM.

The stories were used to depict the following hypothetical

negative partner behaviours : jealousy, negative mood, lack of

interest, lack of support in carrying out household chores, an

unexpected let down, and abandonment. Many of these themes

had been used in previous research in the field (Fincham &

Bradbury, 1992 ; Holtzworth-Munroe & Hutchinson, 1993).

Hypothetical behaviours were used because they enable stan-

dard stimuli to be presented to all participating subjects and

because they could be rated by subjects who were not currently

in a love relationship. Following the RAM, negative partner

events were used because previous research has shown that

attributions for negative events are related more consistently

and more strongly to marital satisfaction than are attributions

for positive events (Baucom, Epstein, Sayers, & Goldman-Sher,

1989 ; Fincham, Beach, & Nelson, 1987).

Examples of the situations include the following :

(1) A woman and her partner have two young children and

she notices that he has not completed the chores and tasks

that he said he would do around the house.

(2) A woman wants to tell her partner something that has

been on her mind for a while and is important to her.

Finally she tells him and as she does she notices that he is

not paying attention to her and he is watching the

television.

Composite attribution indices were formed for responses across

the 18 causal attribution responses (3 dimensions

i6 stimulus

events) and the 18 responsibility attribution responses (3

dimensions

i6 stimulus events). Higher scores on each subscale

reflected attributions that accentuated the impact of the negative

partner behaviour (e.g. see it as more stable, intentional, and

blameworthy). These composite attribution indices were found

to be reliable. The alpha coefficient for the causal attribution

composite was (

α l n86) and for the responsibility attribution

composite it was (

α l n93).

470

G. M

CARTHY and A. TAYLOR

Interview measures of love relationships

. The quality of

subjects’ love relationships was assessed using the appropriate

section from the Adult Personality Functioning Assessment

(APFA), (Hill, Harrington, Fudge, Rutter, & Pickles, 1989).

The APFA assesses functioning in a range of domains (work,

love relationships, friendships, everyday coping, nonspecific

social contacts, and negotiations with officials and others).

Unlike trait-based measures of personality functioning, the

APFA depends on detailed descriptions of behaviour and

ratings are made by the interviewer from relatively extended

periods (of 5 years at the least). In this study ratings were made

for the previous 5 years. Questioning in each domain covers a

range of issues. In relation to love relationships, questioning

covers relationship histories during the rating period, and the

extent of shared activities, support, confiding, arguments, and

violence in each relevant relationship. The interview also

provides evidence of any deviance (defined as criminality,

drinking, problems of drug abuse) in participants’ partners’

functioning. Each domain is rated on a 6-point scale, with a

rating of 1 indicating exceptionally positive functioning, 2

indicating good functioning, 3 reflecting relatively minor or

transient problems, and ratings of 4, 5, and 6 indicating

increasing degrees of difficulty. For example, in love relation-

ships if a person has been married or has cohabited for several

years, and there have not been any major difficulties, a rating of

1 or 2 is made. When the subject has had persistent discord

leading to repeated breakdown of relationships, or when all

relationships have lacked confiding and support, or there was

an absence of sustained committed relationships, a rating of 5

or 6 is made. A rating of 4, 5, or 6 was taken as indicating that

a person had experienced difficulties in the domain of adult love

relationships over the last 5 years and a rating of 1, 2, or 3 was

taken as indicating positive functioning in this domain. The

APFA shows good inter-rater reliability with interclass cor-

relations (ICCs) ranging from

n65 to n88 in individual domains

and a mean ICC of

n77 (Hill et al., 1989). The ICC for the love

relationships domain was

n81.

Beck Depression Inventory

(BDI ) (Beck, 1984). An additional

aim of the study was to investigate the impact of current mood

on the pattern of associations predicted above. For example,

current mood states may influence reports of the past or they

may lead to distortions or biases in the reporting of more recent

events or experiences (Lewinsohn & Rosenbaum, 1987). Con-

sequently, associations between child abuse, relationship

difficulties, and the potential mediators could in part be

accounted for by current mood state. In order to investigate

this issue the BDI was used. This is a widely used 21-item

questionnaire designed to assess the severity of current de-

pressive symptoms.

Statistical Methods

The majority of analyses were carried out using SPSS (SPSS

Inc., 1994). Due to the small sample size of our study the

association between categorical variables was tested using

Fisher’s Exact test. Differences between groups on the con-

tinuous measures were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests

using exact p values as the scales were non-normal. Correlations

between scales were investigated using Spearman’s rank coef-

ficient. For the final mediation models exact logistic regression

using the package LogXact (LogXact, 1996 ; Mehta & Patel,

1995) was used. This enabled us to avoid problems with tests

based on large sample approximations that are used in standard

maximum likelihood logistic regression (Mehta & Patel, 1995).

All analyses were carried out on 39 cases except for the analyses

that included the BDI and the self-esteem scale, each of which

had one case with missing data.

Results

Child Abuse and Adult Relationships : Descriptive

Statistics

The incidence of child abuse was high in our sample.

Forty-one per cent (16

\39) of women with complete data

reported having experienced some form of child abuse :

six reported having been sexually abused, seven reported

having been physically abused, and three reported emo-

tional abuse. Three women reported having experienced

more than one form of child abuse. As expected, a high

level of negative functioning in adult love relationships

were found in this sample. Forty-nine per cent (19

\39)

were rated as having negative functioning in the domain

of adult love relationships over a 5-year period (rating of

4, 5, or 6 on the APFA) whereas 51 % (20

\39) were rated

as having positive functioning in this domain (rating of 1,

2, or 3 on the APFA).

Association between child abuse and poor adult relation

-

ships

. Child abuse and negative functioning in adult love

relationships were strongly associated. Among those who

had experienced child abuse 75 % (12

\16) were rated as

having experienced difficulties in adult love relationships

compared with only 30 % (7

\23) of those who had not

experienced child abuse (Fisher’s Exact Test, p

l n01).

Effects of current mood

. We investigated the possible

effect of current mood on the association between child

abuse and negative functioning in adult love relationships

and found that the BDI measure was not significantly

related to child abuse (Table 1). However, the level of

current depressive symptoms was considerably higher in

the group with poor adult relationships compared to the

group with good relationships, this difference just failing

to reach significance. As depressed mood was not

associated with child abuse it cannot act as a mediator of

the association between child abuse and poor adult

relationships. Therefore, the BDI measure has not been

included in subsequent analyses.

Possible Mediators : Descriptive Statistics

Theoretically we were interested in three possible

mediators of the association between child abuse and

difficulties in the domain of adult love relationships : self-

esteem, attachment style, and attributional style. De-

scriptive statistics for measures of these characteristics

are as follows : (1) Self-esteem : RSD scale mean 13

n3 (SD

3

n6); (2) Relationship attribution scales: responsibility

scale mean 64

n1 (SD 17n7), causal scale mean 67n8 (SD

12

n9); (3) Attachment scales: avoidant scale mean 3n4

(SD 2

n2), ambivalent scale mean 3n3 (SD 2n2). Although

we have not used the secure attachment scale and the

forced-choice attachment classification we include them

here for completeness. As expected, in our sample there

was a high rate of insecure attachment styles, with 41 %

of women rating themselves as having an avoidant

attachment style (16

\39) and 15% (6\39) rating them-

selves as anxious-ambivalent. The remaining 44 % rated

themselves as having a secure attachment style (17

\39).

This distribution of subjects across the three attachment

471

AVOIDANT

\AMBIVALENT ATTACHMENT STYLE

Table 1

Association between Measures

Experienced child abuse

Poor adult relationships

Yes

No

Test

Yes

No

Test

Variable

Mean

(SD)

Mean

(SD)

statistic

a

p

Mean

(SD)

Mean

(SD)

statistic

a

p

Beck Depression Inventory

9

n5

(9

n2)

8

n8

(6

n8)

170

n0

n953

11

n6

(8

n9)

6

n8

(5

n7)

116

n5

n063

Self-esteem

12

n5

(3

n2)

13

n8

(3

n8)

128

n0

n191

12

n1

(3

n2)

14

n4

(3

n6)

101

n0

n021

Attribution scales

Responsibility

71

n5 (16n6)

59

n0 (17n0)

122

n5

n079

73

n9 (13n9)

54

n9 (16n1)

68

n5

n001

Causal

72

n8 (11n1)

64

n3 (13n2)

121

n0

n074

74

n2

(9

n7)

61

n8 (12n8)

61

n0

n001

Avoidant attachment scale

4

n4

(2

n2)

2

n7

(2

n0)

109

n5

n032

4

n7

(2

n1)

2

n2

(1

n6)

66

n0

n001

Ambivalent attachment scale

4

n2

(2

n4)

2

n7

(1

n8)

116

n5

n053

4

n4

(2

n1)

2

n3

(1

n7)

80

n0

n002

Avoidant

\ambivalent scale

8

n6

(3

n9)

5

n4

(3

n2)

98

n5

n014

9

n1

(3

n3)

4

n4

(2

n6)

53

n5

n001

Secure attachment scale

3

n3

(2

n1)

4

n5

(2

n1)

115

n5

n050

3

n1

(1

n8)

4

n9

(2

n1)

90

n0

n004

a

All tests based on Mann–Whitney U.

categories was different from those found in other studies.

In their 1987 study Hazan and Shaver, for example,

found that 55 % were secure, 25 % avoidant, and 20 %

ambivalent, whereas Feeney and Noller (1990), in their

study of Australian students, found 55 % were secure,

30 % avoidant, and 15 % ambivalent. In particular, lower

rates of secure attachment style and higher rates of

avoidant attachment style were found here. The mean of

the secure attachment scale was 4

n0 (SD l 2n1).

The pattern of associations between the three proposed

mediating constructs (attachment style, relationship attri-

butions, and self-esteem) were also investigated, and

significant correlations were found between the measures.

The relationship attribution measures were correlated

with the two attachment scales, particularly the avoidant

scale, which had a correlation of

n43 (p l n006) with the

causal scale and

n42 (p l n008) with the responsibility

scale (correlations for the ambivalent scale were : .37,

p

l n019 and n35, p l n029, respectively). Scores on the

RSD were negatively correlated with both of the attach-

ment scales and the attributional scales. The individual

correlations were as follows : avoidance scale

lkn40,

p

l n013; ambivalence scale lkn56, p

n001; causal

scale

l kn39, p l n015; and responsibility scale lkn33,

p

l n042. The avoidant and ambivalent attachment

scales were positively correlated (correlation

l n51,

p

l n001), as were the attributional style scales (corre-

lation

l n58, p n001).

Possible Mediators : Preliminary Analyses

As a first stage in our analyses we looked at the relation

between our potential mediators and the experience of

child abuse to determine the magnitude and significance

of their association and therefore the possibility of

mediation. Results of these analyses are given in Table 1.

The measures of self-esteem and attributional style were

not significantly related to the experience of child abuse in

this sample and therefore could not act as mediators to

problems in adult functioning. For the RSD, the mean

scores by experience of child abuse were slightly lower in

the group who had experienced child abuse. The attri-

butional style measures gave more differentiation be-

tween the two groups, but the difference between groups

was above significance levels. Child abuse was signifi-

cantly related to attachment style with the difference

between groups being largest for the avoidance scale,

whereas the difference between groups for the ambiv-

alence scale was of slightly smaller magnitude and just

over the nominal significance level (see Table 1). As the

above analyses indicated that both types of insecure

attachment were related to child abuse and were highly

correlated, we created a further scale by summing the

individual ambivalence and avoidance scales. This re-

sulted in an overall avoidant

\ambivalent scale, with high

values indicating an attachment style characterised by

high level of both ambivalence and avoidance. We

considered it preferable to use this measure rather than

the secure attachment measure because it indexes negative

attachment process explicitly and in further analyses we

will focus primarily on this attachment measure. Based

on this measure, those who had experienced child abuse

had a much higher score on the avoidant

\ambivalent

scale than those who had not experienced child abuse

(see Table 1).

Attachment style and poor adult love relationships

. In

order to function as a mediator between poor adult

relationships and the experience of child abuse the

attachment measure also needed to be associated with

relationship difficulties. When we investigated this as-

sociation we found a strong link with avoidant

\

ambivalent attachment scale and difficulties in the do-

main of adult love relationships. The mean of this scale

among those with good functioning in this domain was

4

n4 (SD 2n6) compare to a mean of 9n1 (SD 3n3) for those

with poor functioning.

Other mediators and poor adult love relationships

.

Although attributions were not significantly related to

child abuse, they were strongly related to poor function-

ing in the domain of adult love relationships (see Table 1).

For example, subjects with poor functioning in the

domain of adult relationships had more negative scores

on the responsibility scale. This indicated that they were

more likely to attribute negative intent and blame than

those who did not have poor adult relationships. The

RSD scale was also related to poor relationships in

adulthood, with those having experienced poor relation-

ships having significantly lower RSD scores (see Table 1).

472

G. M

CARTHY and A. TAYLOR

Table 2

Logistic Regression Models of Poor Adult Relationships

95 % CI

OR

Lower

Upper

Score

a

p

b

Model 1

Child abuse

6

n48

1

n36

38

n27

7

n31

n006

Model 2

Child abuse

3

n70

0

n51

32

n90

2

n43

n142

Avoidant

\ambivalent scale

1

n56

1

n18

2

n24

11

n17

n001

a

Exact conditional scores test (df

l 1).

b

Mid-p value.

Attachment style as a mediator between child abuse and

adult relationship difficulties

. To investigate the potential

mediating effect of attachment style on the relation

between child abuse and poor adult relationships we used

exact logistic regression models ; the results are presented

in Table 2. Model 1, with only the effect for child abuse

fitted, indicates the strength of the relation between child

abuse and poor adult relationships. Those who had

experienced child abuse were over six times more likely to

have difficulties in the domain of intimate adult relation-

ships than those who had not. The large bounds to the

confidence interval for this effect are due to the small

sample size of the study, which results in a large degree

of uncertainty about the magnitude of the effect,

particularly in its upper bound. In order to test the

possible mediating effect of attachment style on child

abuse the avoidant

\ambivalent scale was added to the

model (Model 2). This scale was strongly related to poor

adult relationships—the more insecure individuals being

more likely to have poor functioning in the domain of

adult love relationships. The effect of child abuse in

this model was markedly diminished, becoming non-

significant and with the odds ratio falling by 43 % to 3

n7,

indicating that an avoidant

\ambivalent attachment style

is a strong mediator in the route from child abuse to

poor adult relationships.

Discussion

Results from this study provide support for the idea

that the link between abusive childhood experiences and

difficulties in making supportive cohabiting relationships

in adulthood are mediated in part by an avoidant

\

ambivalent attachment style. We have been able to

demonstrate that the avoidant

\ambivalent attachment

scale meets the three conditions outlined by Baron and

Kenny (1986) for judging whether a variable can be said

to function as a mediator. First, abusive childhood

experiences were found to be significantly related to the

avoidant

\ambivalent scale and second, the avoidant\

ambivalent scale was significantly related to difficulties in

the domain of intimate adult relationships. Finally, a

previously significant relationship between child abuse

and difficulties in adult love relationships became non-

significant when the above two pathways were controlled.

Importantly, this pattern of findings could not be

accounted for by current depressive mood. Previous

research has suggested that current mood states may be

associated with distortions or biases in the reporting of

recent experiences (Lewinsohn & Rosenbaum, 1987).

Ratings of current mood on the BDI were not sig-

nificantly related to reports of having experienced child

abuse nor to adult relationship difficulties. Also of interest

was the finding that the other two potential mediating

variables, self-esteem and relationship attributions, did

not appear to play a significant role in mediating the

effects of abusive childhood experiences on later re-

lationship abilities. We have been able to establish that

child abuse appears to have a direct negative impact on

functioning in later adult love relationships in a sample

where all the women had experienced poor parenting

in childhood, and that this link is partly mediated by

attachment processes. Child abuse is often associated

with other measures of poor family functioning and it has

been suggested that the latter may account for much of

the variance in the outcomes of child abuse victims

(Fromouth, 1986 ; Harter et al., 1988 ; Wyatt & Mickey,

1987). One of the particular strengths of this study’s

design was that we were able to explore these specific links

in a sample where all the women had experienced adverse

childhood experiences.

Of particular interest was the finding that an avoidant

\

ambivalent style appeared to play an important role in

mediating the effects of child abuse on adult relationship

difficulties. This suggests that child abuse may increase

the risk of developing an attachment style that is

characterised by high levels of avoidance and ambiv-

alence. That is, abusive experiences in childhood may

increase the risk of developing multiple and contradictory

strategies for dealing with attachment-related issues in

intimate relationships and this may give rise to recurrent

oscillations between a desire for extreme forms of

intimacy and a desire to maintain distance. For example,

when moving closer to romantic partners, women who

have been abused in childhood may feel anxious about

the prospect of developing an intimate relationship and

this may lead them to distance themselves from the

partner. However, when they move away, they may feel

uncomfortable about being alone and this may in turn

fuel the desire again for more extreme forms of intimacy.

The finding that an avoidant

\ambivalent attachment

style may play a role in mediating the effects of child

abuse on adult relationship difficulties is in line with

findings from research on attachment in childhood and

adulthood, where atypical attachment categories have

been found in a range of high-risk groups (Belsky &

Cassidy, 1994). Main and Soloman (1986) identified a

fourth pattern known as disorganised

\disoriented in

473

AVOIDANT

\AMBIVALENT ATTACHMENT STYLE

children and Crittenden (1988) called these atypical

patterns avoidant-resistant (A

\C) as they are charac-

terised in part by a co-mingling of avoidant and am-

bivalent behaviour. Rates of these attachment classi-

fications are known to increase as the severity of social

risk factors increases (Carlson et al., 1989 ; Cicchetti &

Toth, 1995 ; Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Grunebaum, &

Botein, 1990), and researchers have also recently es-

tablished that disorganised attachment classification is

associated with the development of hostile and aggressive

behaviour in children both at home and in the classroom

(Lyons-Ruth, Alpern, & Repacholi, 1993). Latty-Mann

(1989, 1991), in a study of adults who had grown up in

families with an alcoholic parent, identified a subgroup of

persons who rated themselves as experiencing high levels

of avoidance and ambivalence in their love relationships.

Latty-Mann suggested that this attachment style could be

called ‘‘ Ambivalent ’’ because they appeared both to

want closeness but also to fear it and its consequences.

Latty-Mann and Davis (1996) have recently provided

evidence suggesting that this new attachment style is

closely related to Bartholomew’s Fearful-Avoidant at-

tachment style (Bartholomew, 1990). Importantly, Fear-

ful attachment style is also known to be related to a

number of high-risk environments such as having had

problem drinking parents (Brennan et al., 1991) and

being the victim of incestuous abuse (Alexander, 1993).

Interestingly, Brennan et al. suggested, following Latty-

Mann and Davis (1988), that the fearful avoidant

category in Bartholomew’s scheme may be analogous to

the disorganised or A

\C category in infancy (Crittenden,

1988 ; Main & Soloman, 1986).

The fact that the residual pathway between child abuse

and relationship difficulties was not reduced to zero in

our final analyses suggests that an avoidant

\ambivalent

attachment style is one of a number of mediating factors

rather than the single dominant mediator. More research

is required to identify other mediating factors. These may

include other cognitive-affective variables such as dys-

functional patterns of emotional regulation (Cicchetti,

Ganiban, & Barnett, 1991 ; Thompson, 1990) and bodily

shame (Andrews, 1995, 1997 ; Gilbert, 1989 ; Gilbert,

Pehl, & Allen, 1994), as well as genetic and temperamental

factors (Rutter et al., 1997).

The finding that the Rosenberg self-derogation scale

did not appear to be a significant mediator was perhaps

surprising given that negative self-esteem is hypothesised

to play an important role in mediating the link between

early adversity and vulnerability to depression in adult-

hood (Brown & Moran, 1994 ; Harris, Brown, & Bifulco,

1990). However, the findings from this study suggest that

although negative self characteristics may mediate the

link between child abuse and adult depression, attach-

ment style is a more important mediator in the link

between child abuse and adult relationship abilities.

Interestingly, recent work suggests that insecure attach-

ment leads to depressive symptoms in adulthood in-

directly through its impact on low self-esteem and

dysfunctional attitudes (Roberts, Gotlib, & Kassel, 1996).

Alternatively, the finding that self-esteem was not a

significant mediator in the link between child abuse and

adult relationship abilities may in part reflect issues in the

measurement of self-esteem. For example, in an attempt

to overcome the perceived limitations of questionnaire

measures of global self-esteem, Brown and his colleagues

have developed an interview known as the Self-Evalu-

ation and Social Support Instrument (SESS), where

ratings are made on the basis of details about the quality

of the subjects’ life (Brown, Andrews, Bifulco, & Veiel,

1990). They have also found that the SESS is more

effective in predicting depression than Rosenberg’s self-

esteem questionnaire and they suggest that this is because

the SESS taps specific areas of self-dissatisfaction in real-

life situations and is less vulnerable to mood-state effects

than the more global questionnaire measure (Andrews &

Brown, 1993). In order to address these issues, inter-

viewer-based measures of the self such as the SESS could

be incorporated into future studies.

The findings in relation to the attributional measures

also deserve further consideration. Patterns of causal and

responsibility attributions were significantly related to

investigator-based ratings of functioning in the domain

of adult love relationships and the causal and responsi-

bility scales were also found to be moderately related to

child abuse. In particular, women with negative func-

tioning in their love relationships were found to have

more maladaptive causal and responsibility attributions

than women with good functioning in this domain. These

findings add to the growing body of literature on the links

between attributional processes and the quality of in-

timate adult relationships (Baucom, 1987 ; Bradbury &

Fincham, 1990). Although our findings suggest that

attachment processes are more powerful mediators than

relationship attributions in the link between child abuse

and adult relationship abilities, this pattern of findings

may in part be related to a number of methodological

difficulties associated with the measurement of attribu-

tional processes in close relationships. First, a number of

researchers have highlighted the problems associated

with trying to untangle the association between attri-

bution processes and current relationship satisfaction

(Berscheid, 1994 ; Bradbury & Fincham, 1990). Second,

the use of hypothetical situations to assess attributional

processes in close relationships has also been criticised

(Berscheid, 1994). In order to begin to address these

issues future studies may need to incorporate other

techniques that have been developed to assess attributions

in close relationships. These include coding attributions

from videotaped marital interactions (Holtzworth-

Munroe & Jacobsen, 1988) and thought sampling during

current interactions using an intercom (Berman, 1988).

Results from this study also revealed significant associ-

ations between measures of relationship attributions and

attachment style. This suggests that internal working

models of attachment are related to the way in which

adults interpret and attribute meaning to the behaviour

of their partners in close relationships (Bowlby, 1973).

Although the cross-sectional nature of the current study

was not able to address the direction of effects between

these two sets of constructs, the finding that attachment

style, but not attributional processes, were related to

childhood experiences suggests that attachment processes

may be playing a role in influencing the organisation of

attributional processes. However, it seems likely that

once established, internal working models of attachment

and attributional processes will influence one another in a

474

G. M

CARTHY and A. TAYLOR

reciprocal manner, with both sets of cognitive processes

acting to maintain the organisation of the other.

Interpretation of the present findings needs to be

qualified by several factors. First, it is possible that the

procedures used here to assess childhood experiences may

not be an accurate reflection of the quality of these early

experiences. Adult accounts of experiences from child-

hood may be affected by memory bias. However, a recent

review concluded that as long as retrospective reports are

restricted to factual accounts of significant episodes

occurring after the period of infantile amnesia they are

likely to be reasonably valid (Brewin, Andrew, & Gotlib,

1993). These authors suggested that problems associated

with recall bias can be minimised by using investigator-

based interviews. They also found that there was no

convincing evidence that retrospective reports of child-

hood experiences are compromised by current psychiatric

status.

Second, the cross-sectional design of this study makes

it difficult to interpret the direction of causality operating

between attachment style and adult relationship diffi-

culties. Although attachment style may play a role in

determining abilities in close relationships it is also

possible that people who have experienced negative close

relationships might consequently develop a negative

attachment style. In order to address these issues longi-

tudinal prospective studies need to be undertaken where

measures of attachment representations are taken prior

to the assessment of adult relationship abilities.

Third, some circumspection is required in evaluating

this exploratory study given the sample size. Although we

have found significant group differences using standard

levels of significance we have also found smaller group

differences, which might potentially be important even

though they are nonsignificant. This is a consequence of

the limited power of the study. For example, the

difference in BDI levels between women with relationship

difficulties and women with good relationships just failed

to reach nominal significance levels even though the

group differences were quite large. It is therefore im-

portant to replicate the findings of this research in a larger

sample to establish their generality.

If replicated, the finding that attachment processes

may play a role in mediating the link between abusive

childhood experiences and adult relationship difficulties

raises the possibility of designing interventions aimed at

breaking intergenerational cycles of disadvantage. It

suggests that interventions aimed at helping women who

have been abused to become aware of the origins and

potential consequences of their working models of

attachment may be useful in helping them develop

more supportive adult love relationships. Insights from

attachment theory suggest that therapeutic inter-

ventions aimed at helping abused individuals ‘‘ work

through ’’ unresolved childhood experiences could reduce

the likelihood of problems in later intimate relationships.

Alternatively, educational programmes aimed at teaching

at-risk groups about the impact of attachment processes

on intimate relationships and family life may be sufficient

to change the organisation of internal working models of

attachment. More research is required to investigate the

conditions under which representational models of at-

tachment can develop and become updated (Hamilton,

1987). Adolescents who have experienced abusive child-

hood experiences may be a group who would particularly

benefit from such interventions. During adolescence

young people are beginning to establish romantic rela-

tionships and they have also acquired the necessary

cognitive skills to enable them think about the causes and

consequences of their own and others’ behaviour.

Acknowledgements

—We would like to thank the women who

generously agreed to take part in this study, Dr Barbara

Maughan for her helpful comments on earlier drafts of this

paper, and Denise Shields for her help in preparing the

manuscript.

References

Ainsworth, M., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978).

Patterns of attachment : A psychological study of the Strange

Situation

. Hilldale, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum.

Alexander, P. (1993). The differential effects of abuse charac-

teristics and attachment in the prediction of long-term effects

of sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8, 346–362.

Andrews, B. (1992). Attribution process in victims of marital

violence : Who do women blame and why ? In J. H. Harvey,

T. L. Orbuch, & A. L. Weber (Eds.), Attributions, accounts

and close relationships

(pp. 176–193). New York : Springer-

Verlag.

Andrews, B. (1995). Bodily shame as a mediator between

abusive experiences and depression. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology

, 104, 277–285.

Andrews, B. (1997). Bodily shame in relation to abuse in

childhood and bulimia : A preliminary investigation. British

Journal of Clinical Psychology

, 36, 41–50.

Andrews, B., & Brewin, C. R. (1990). Attributions for marital

violence : A study of antecedents and consequences. Journal

of Marriage and the Family

, 52, 757–767.

Andrews, B., & Brown, G. W. (1988). Marital violence in the

community : A biographical approach. British Journal of

Psychiatry

, 153, 305–312.

Andrews, B., & Brown, G. W. (1993). Self-esteem and vul-

nerability to depression : The concurrent validity of interview

and questionnaire measures. Journal of Abnormal Psycho-

logy

, 102, 565–572.

Arend, R., Gove, F., & Sroufe, L. A. (1979). Continuity of

individual adaptation from infancy to kindergarten : A

predictive study of ego-resiliency and curiosity in pre-

schoolers. Child Development, 50, 950–959.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator mediator

variable in social-psychological research : Conceptual, stra-

tegic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology

, 51, 1173–1182.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy : An attach-

ment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relation-

ships

, 7, 147–178.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles

among young adults : A test of a four-category model. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology

, 61, 226–244.

Baucom, D. H. (1987). Attributions in distressed relations :

How can we explain them ? In S. Duck & D. Perlman (Eds.),

Heterosexual relations

, marriage, and divorce (pp. 177–206).

London : Sage.

Baucom, D. H., Epstein, N., Sayers, S., & Goldman-Sher, T.

(1989). The role of cognitions in marital relationships :

Definitional methodological, and conceptual issues. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

, 57, 31–38.

Beck, A. (1984). The Beck Depression Inventory. In M.

Williams (Ed.), The psychological treatment of depression : A

475

AVOIDANT

\AMBIVALENT ATTACHMENT STYLE

guide to the theory and practice of cognitive behavioral therapy

.

New York : Free Press.

Belsky, J., & Cassidy, J. (1994). Attachment theory and

evidence. In M. Rutter & D. F. Hay (Eds.), Developmental

principles and clinical issues in psychology and psychiatry

.

Oxford : Blackwell.

Beitchman, J. H., Zucker, K., & Hood, J. E. (1992). A review of

the long-term consequences of child sexual abuse. Child

Abuse and Neglect

, 16, 101–118.

Berman, W. (1988). The role of attachment in the post-divorce

experience. Journal of Personality, Society and Psychology,

54

, 496–504.

Berscheid, E. (1994). Interpersonal relationships. Annual Review

of Psychology

, 45, 79–129.

Bifulco, A., Brown, G. W., & Adler, Z. (1991). Early sexual

abuse and clinical depression in adult life. British Journal of

Psychiatry

, 159, 115–122.

Bifulco, A., Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1994). Childhood

Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA) : A retrospective

interview measure. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy-

chiatry

, 35, 1419–1435.

Birtchnell, J. (1993). Does recollection of exposure to poor

maternal care in childhood affect later ability to relate ?,

British Journal of Psychiatry

, 162, 335–344.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol 1 : Attachment.

London : Penguin.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, Vol 2 : Separation.

London : Penguin.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds.

London : Tavistock Publications.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss, Vol 3 : Loss, sadness and

depression

. New York : Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base : Parent–child attachment and

healthy human development

. New York : Basic Books.

Bradbury, T. N., Beach, S. R. H., Fincham, F. D., & Nelson,

G. M. (1996). Attributions and behavior in functional and

dysfunctional marriages. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology

, 64, 569–576.

Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Attributions in

marriage : Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin, 107,

3–33.

Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Attributions and

behavior in marital interaction. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology

, 63, 613–628.

Brennan, K. A., Shaver, P., & Tobey, A. (1991). Attachment

styles, gender and parental problem drinking. Journal of

Social and Personal Relationships

, 8, 451–466.

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Gotlib, I. H. (1993). Psycho-

pathology and early experiences : A reappraisal of retro-

spective reports. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 82–98.

Brown, G. W., Andrews, B., Bifulco, A., & Veiel, H. O. F.

(1990). Self-esteem and depression. I. Measurement issues

and prediction of onset. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric

Epidemiology

, 25, 200–209.

Brown, G. W., Bifulco, A., & Andrews, B. (1990). Self-esteem

and depression. III. Aetiological issues. Social Psychiatry and

Psychiatric Epidemiology

, 25, 235–243.

Brown, G. W., Bifulco, A., Veiel, H. O. F., & Andrews, B.

(1990). Self-esteem and depression. II. Social correlates of

self-esteem. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology,

25

, 225–234.

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of

depression

. London : Tavistock.

Brown, G. W., & Moran, P. (1994). Clinical and psychosocial

origins of chronic depressive episodes I : A community survey.

British Journal of Psychiatry

, 165, 447–456.

Brown, G. W., & Rutter, M. L. (1966). The measurement of

family activities and relationships : A methodological study.

Human Relations

, 19, 241–263.

Carlson, V., Cicchetti, D., Barnett, D., & Braunwald, K. (1989).

Disorganized

\disoriented attachment relationships in mal-

treated infants. Developmental Psychology, 25, 525–531.

Champion, L., Goodall, G., & Rutter, M. (1995). Behaviour

problems in childhood and stressors in early adult life : I. A

20-year follow-up of London school children. Psychological

Medicine

, 25, 231–246.

Cicchetti, D., Ganiban, J., & Barnett, D. (1991). Contributions

from the study of high risk populations to understanding the

development of emotion regulation. In K. Dodge & J. Garber

(Eds.), The development of emotion regulation (pp. 15–48).

New York : Cambridge University Press.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1995). Developmental psycho-

pathology and disorders of affect. In D. Cicchetti & S. L.

Toth (Eds.) Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 2 : Risk,

disorder, adaption.

New York : Wiley.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working

models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology

, 58, 644–663.

Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations

of attachment : The structure and function of working

models. In K. Bartholomew & D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances

in personal relationships

, Vol. 5 : Attachment processes in

adulthood

(pp. 53–90). London : Jessica Kingsley.

Crittenden, P. M. (1988). Relationships at risk. In J. Belsky &

T. Nezworski (Eds.), Clinical implications of attachment.

Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum.

Crowell, J. A., & Treboux, D. (1995). A review of adult

attachment measures : Implications for theory and research.

Social Development

, 4, 3.

Davis, K., Kirkpatrick, L., Levy, M., & O’Hearn, R. (1994).

Stalking the elusive love style : Attachment styles, love styles

and relationship developments. In R. Erber & R. Gilmour

(Eds.), Theoretical frameworks for personal relationships.

Hillsdale, NJ : Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1990). Mechanisms

in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683.

Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Valente, E. (1995).

Social-information-processing patterns mediate the effect of

early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of

Abnormal Psychology

, 104, 632–643.

Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1981). Developmental sequelae

of maltreatment in infancy. In R. Rizley & D. Cicchetti

(Eds.), Developmental perspectives in child maltreatment. San

Francisco, CA : Jossey-Bass.