Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Knowledge,

Health Beliefs, and Preventive Practices in 2 Age Cohorts: A

Comparison Study

Kymberlee Montgomery, DrNP, MSN; and Mary Ellen Smith-Glasgow, PhD, RN

Drexel University College of Medicine and College of Nursing, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

ABSTRACT

Background:

Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common sexually transmitted

infection in the United States and a known precursor of cervical cancer. Recent studies suggest a bimodal

HPV prevalence for women in 2 age groups: 19 to 26 and 40 to 70. HPV and cervical cancer knowledge has

yet to be investigated in the older population of women.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate and compare the HPV and cervical cancer

knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive practices in women in these 2 age groups.

Methods:

This study used a cross-sectional, descriptive design. A convenience sample of 300 women in

2 age groups was recruited from 3 ambulatory obstetrics and gynecology practices in Philadelphia, Pa.

Participants completed the Awareness of HPV and Cervical Cancer Questionnaire to determine their HPV

and cervical cancer knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive practices.

Results:

A total of 280 responses (131 for the age group 19 –26 years and 149 for the age group 40 –70

years) were received. Significant differences were found between the 2 groups in knowledge (P

⫽ 0.010)

only, but not health beliefs (perceived susceptibility [P

⫽ 0.111] and perceived seriousness [P ⫽ 0.266]).

Significant differences in select preventive practices were also noted between these 2 groups. These

included Pap smear (P

⫽ 0.05), use of condoms (P ⫽ 0.002), and use of oral contraception (P ⬍ 0.001).

Conclusions:

There is a remarkable need for age-appropriate HPV and cervical cancer awareness and

education for women older than the age of 40. Women’s health care providers are perfectly positioned to

act as a catalyst to improve HPV and cervical cancer knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive practice to

ensure optimal health promotion for all women. (Gend Med. 2012;9:S55–S66) © 2012 Elsevier HS Journals,

Inc. All rights reserved.

Key words:

cervical cancer, health knowledge, human papillomavirus.

Accepted for publication November 1, 2011.

doi:10.1016/j.genm.2011.11.002

© 2012 Elsevier HS Journals, Inc. All rights reserved.

1550-8579/$ - see front matter

G

ENDER

M

EDICINE

/V

OL

. 9, N

O

. 1S, 2012

S55

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 20 million Americans are currently

infected with one or more low-risk (types 6 and 11)

and/or high-risk (types 16 and 18) human papillo-

maviruses (HPVs).

Although new prevention vac-

cines are available,

⬎6 million will become newly

infected each year.

Spread mostly through skin-

to-skin contact during any type sexual contact,

HPV is the etiologic agent of genital warts and can

be isolated in 99.7% of cervical cancer cases.

Although HPV is implicated in cancers affecting

other organ sites, including vulval, oral, and anal

cancers, the study presented here focused on cer-

vical cancer risk. HPV-related cancer is the second

leading cause of cancer deaths in women world-

wide, including

⬎4200 deaths in the United States

in 2010.

Therefore, it is evident that HPV-related

cervical cancer affects millions of women and is

responsible for significant morbidity and mortality

worldwide. Cervical cancer alone contributes to

⬃300,000 lives lost annually.

Although previous studies demonstrated a de-

crease in HPV prevalence as women age, research

instead suggests that a bimodal HPV prevalence

distribution is present showing a first peak around

the age of 20 years and a second peak around the

age 40 to 50 years.

Fluctuations in relationship

infrastructure in which there are increases in di-

vorce rates and infidelity disclosures and accep-

tance of nontraditional sexual relationships place

women at age 40 and older to be at a higher risk for

sexually transmitted infection exposures. A pleth-

ora of studies demonstrated limited HPV knowl-

edge and health beliefs in both the adolescent and

college-age populations.

Multilevel educa-

tional interventions have targeted preteens, teen-

agers, and college students regarding HPV and its

relation to cancer. Women aged 40 and older are

often overlooked, despite the facts that 80% of

women will be infected with HPV by the age of 50

and 35% of cervical cancer deaths occur in women

older than the age of 65. Other HPV-related can-

cers also disproportionately affect older women.

The incidence of vulval cancer increases from 1.1

per 100,000 in women aged 25 to 39 to 3.8 in

those of ages 60 to 64. Women older than the age

of 40 may not believe themselves at risk and,

therefore, may not practice preventive measures

that can potentially save their lives. In addition,

although HPV also affects women older than the

age of 40, there are few HPV educational or pre-

vention campaigns targeting middle-age and older

adult female populations.

The purpose of this study was to determine the

differences in knowledge, health beliefs (suscepti-

bility and seriousness), and preventive practices

related to HPV and related cancers in groups of

women aged 19 to 26 and 40 to 70 years. The

research hypothesis was that women aged 40 to 70

years will have less knowledge, perceive them-

selves to be less susceptible, and report lower use of

preventive practices regarding HPV and cervical

cancer compared with women aged 19 to 26 years.

The results of this study regarding the women aged

40 and older were previously reported by Mont-

gomery et al.

Study Design

This descriptive study used a cross-sectional de-

sign to determine differences in knowledge and

health beliefs related to cervical cancer and HPV in

women aged 40 to 70 years compared with those

aged 19 to 26 years. Over a 2-month period, anon-

ymous data were collected using a self-adminis-

tered pen-and paper questionnaire.

Setting and Sample

A convenience sample of 131 women aged 19 to

26 and 149 women aged 40 to 70 years was re-

cruited from the waiting rooms of 3 ambulatory

obstetrics and gynecology offices of a large metro-

politan university hospital in Philadelphia, Pa. All

3 offices were used in an attempt to get a racially

heterogeneous sample in this urban area that has

rate of cervical cancer 1.7 times higher than the

national rate.

The inclusion criteria were women

aged 19 to 26 or 40 to 70 years presenting to their

health care provider for an annual well woman

visit and who did not have a history of HPV or

cervical cancer.

The application G*Power (Version 3.0.10, Uni-

versity of Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany) was

used to guide the power analysis for this study. The

power analysis was based on an independent sam-

Gender Medicine

S56

ple t test in which the 2 groups (women aged

19 –26 years and 40 –70 years) were to be compared

at 1 time point for the primary dependent variable:

knowledge. Small to medium effect size (0.36) was

postulated in keeping with Cohen’s recommenda-

tion for differences between cells means (Cohen’s

d).

Power was set at 0.80, meaning that there

would be an 80% probability of reaching statistical

significance if there is difference between the

groups.

In this study, for a significance level of

␣ ⫽ 0.05,

with an effect size of 0.36, to achieve a power of

0.80, a total sample size of 250 subjects with 125

subjects in each group was required. To ensure

adequate power and allow for any attrition due to

missing data, an additional 50 subjects were re-

cruited. Of the 300 women who received the study

packets, 280 respondents were eligible for analysis

and returned the completed questionnaires in

sealed envelopes; 20 questionnaires were incom-

plete and were not used in these analyses. Partici-

pants were classified into 2 groups based on their

age. The first group (group A) comprised of women

between 19 and 26 years of age (n

⫽ 131). The

second group (group B) included women between

the ages of 40 and 70 years (n

⫽ 149).

Procedure

After approval by the university’s institutional

review board, the study commenced by training a

research assistant (RA; receptionist) at each of the

3 offices. The training entailed using data on the

practice management program to identify poten-

tial eligible participants when women are checked

in for their visits, inviting potential participants,

and keeping all data anonymous by sealing all

envelopes and placing them in the research bin in

a secured drawer in the specific office. At each of

the 3 sites, there were flyers posted on the walls

and a trained RA invited participants if they met

eligibility. If the patient met 2 of the requirements

(age and the reason for the visit [well-women

check up]), she was given an additional informa-

tional sheet to read to further determine eligibility

(exclusion criteria if she had a history of HPV or

cervical cancer). After she read the sheet, the RA

asked if she was eligible. If the patient said yes, she

was given the survey packet with a cover letter that

accompanied the packet. The cover letter con-

tained a brief description of the research project,

assurance of anonymity, the voluntary nature of

participation, and institutional review board con-

tact information. Completion of the survey acted

as consent for participation. Once the survey was

completed, it was placed in a sealed envelope to be

returned to the researcher. Complete anonymity

was maintained, and no identity was disclosed.

Main Research Variables

Sociodemographic variables collected in this

study included age, race, education, health insur-

ance status, religious affiliation, marital status, and

income level.

HPV and Cervical Cancer Knowledge, Health

Beliefs, and Preventive Practices

The Awareness of HPV and Cervical Cancer

Questionnaire was used to measure knowledge,

health beliefs and perceptions, and preventive

practices related to HPV and cervical cancer.

This

self-administered, 36-item questionnaire was de-

veloped by Ingledue et al

based on the Health

Beliefs Model (HBM)

to investigate HPV/cervical

cancer knowledge, health beliefs and perception,

and preventive measures in college-age women.

This tool was selected because it was specifically

designed to measure HPV and cervical cancer

awareness, but also because it was based on the

HBM, the conceptual framework that guided this

study. Before selection, the questionnaire was re-

viewed by a panel of experts consisting of obste-

tricians/gynecologists, physicians, and nurse prac-

titioners from the university who concluded that

the questions were generalizable to women of all

age groups. Despite its original intent of targeting

college-age women, subsequent studies have used

this questionnaire in women of various age

groups, thereby validating its generalizability for

age.

The questionnaire is divided into 3 sections. The

first section consists of 15 multiple-choice questions

intended to measure knowledge of HPV and cervical

cancer. One point is awarded for each correct re-

sponse. Scores can be between 0 and 15, with higher

K. Montgomery and M. Smith-Glasgow

S57

scores indicative of higher level of HPV and cervical

cancer knowledge. The second section is intended to

measure the perceived threat portion of cervical can-

cer and consists of 15 questions, each with possible

responses using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging

from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Nine

of the 15 questions relate to perceived susceptibility

and have a possible subtotal score range of 9 to 45.

The remaining 6 questions relate to perceived seri-

ousness and have a potential score that ranges from

6 to 30. Higher scores denote that perceived suscep-

tibility and seriousness about HPV and cervical can-

cer are high. The final section of the questionnaire

consists of 6 questions that focus on individual sex-

ual behaviors, risk factors, and history of Pap smears.

These multiple-choice questions represent a measure

of preventive practices related to HPV and cervical

cancer.

Ingledue et al

used consensual validity via a

panel of experts who represented several health

professionals including 2 gynecologists, 2 profes-

sors of health education, and a medical profes-

sional from the Breast and Cervical Cancer

program to support content validity of the in-

strument. The authors also conducted a test-retest

reliability procedure over a 10-day period to estab-

lish the stability of the instrument over time. High

test-retest reliability was reported for knowledge (r

⫽ 0.90), perceptions and beliefs (r ⫽ 0.95), and

preventive behaviors (r

⫽ 0.90). Internal consis-

tency reliability was not reported in the study by

Ingledue et al.

For the current study, the internal

consistency reliability was adequate (Cronbach’s

␣

⫽ 0.77) for the knowledge subscale and the sus-

ceptibility subscale (

␣ ⫽ 0.66) but unacceptably

low for the seriousness subscale (

␣ ⫽ 0.20). The

low reliability for the seriousness subscale makes

any conclusion based on this subscale tentative at

best. Quantitative data were coded and entered

into the SPSS-PC program, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, Illinois) and stored on a secured com-

puter used for research purposes only.

Data Analysis

All data were collected strictly anonymously

with no identifying information or codes associ-

ated with them. Frequency distributions and mea-

sures of central tendency and variability were cal-

culated for sociodemographic and dependent

study variables. All values with missing data were

tracked and excluded from analysis. Chi-square

tests were performed to verify differences in

sociodemographic characteristics between the

groups.

To examine differences in knowledge and health

beliefs (susceptibility and seriousness) between the

younger and older groups of women, indepen-

dent-sample t tests were performed. However, ac-

cording to the HBM, knowledge, susceptibility,

and seriousness can have confounding effects on

each other and should be controlled for appropri-

ately. Therefore, to adjust for any differences in

sociodemographic characteristics as well as con-

founding effects of subdimensions of health be-

liefs (eg, knowledge and seriousness when compar-

ing susceptibility), additional ANCOVAs were

performed with the potential confounders acting

as covariates. Before analysis, the dependent vari-

ables were tested to meet the assumptions of

ANCOVA. Chi-square analyses were used to exam-

ine any differences in distribution of responses

between the groups of women for preventive prac-

tices. The Fisher exact test was used if the assump-

tions of the

2

test were not met. The level of

significance for all the tests was set at

␣ ⫽ 0.05.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographics of all the participants in this

study are detailed in

. The respondents

identified themselves as mostly white (55.4%) and

African

American

(29.6%),

college

graduates

(42.9%), Catholic (38.6%) or Christian (31.80%),

mostly single (42.9%) or married (34.3%), with an

annual income of $41,000 to $60,000 (27.4%) and

private health insurance (80%). The

2

test com-

paring the sociodemographic characteristics be-

tween the 2 groups revealed that the groups were

similar for the sociodemographic characteristics of

education (P

⫽ 0.24), type of insurance (P ⫽ 0.08),

and race (P

⫽ 0.06) but significantly different for

marital status (P

⬍ 0.001), religion (P ⫽ 0.02), and

income level (P

⬍ 0.001).

Gender Medicine

S58

As seen in

, more women in the older

group reported being married (50.30%) compared

with the younger group (16%), whereas more single

women were present in the younger group (68.7%)

than in the older group (20.10%). The number of

women reporting that their religion was Catholic

was significantly higher in the older group (43.6%)

compared with the younger group (32.8%), along

Table I. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants (N

⫽ 280).

Characteristic

Total Sample

(N

⫽ 280),

100%

Group A

(Age 19-26 y, n

⫽ 131),

47%

Group B

(Age 40–70 y, n

⫽ 149),

53%

P

Age, y, mean (SD)

37.93 (14.96)

23.22 (2.3)

50.86 (7.60)

⬍0.001

Sexual partners, mean (SD)

2.62 (3.05)

3.91 (3.8)

1.45 (1.37)

⬍0.001

Race/ethnicity, n (%)

0.062

White/non-Hispanic

155 (55.40)

63 (48.10)

92 (61.70)

African American/non-Hispanic

83 (29.60)

46 (35.10)

37 (24.80)

Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

14 (5)

8 (6.10)

6 (4)

Hispanic/Latino

22 (7.90)

13 (9.90)

9 (6)

Other

6 (2.10)

1 (0.80)

5 (3.40)

Missing

0

0

0

Education

0.236

High school graduate

60 (21.40)

22 (16.80)

38 (25.50)

Some college courses

94 (33.60)

51 (38.90)

43 (28.80)

College graduate

120 (42.90)

56 (42.70)

64 (43)

Other

5 (1.80)

2 (1.50)

3 (2)

Missing

1 (0.30)

0

1 (0.70)

Marital status

⬍0.001

Single

120 (42.90)

90 (68.70)

30 (20.10)

Married

96 (34.30)

21 (16)

75 (50.30)

Widowed

7 (2.50)

0 (0)

7 (4.70)

Divorced

25 (9.00)

1 (0.80)

24 (16.10)

Living with significant other

31 (11.00)

19 (14.50)

12 (8.10)

Missing

1 (0.30)

0

1 (0.70)

Religion

0.022

Christian

89 (31.80)

48 (36.70)

41 (27.50)

Catholic

108 (38.60)

43 (32.75)

65 (43.60)

Jewish

23 (8.20)

5 (3.80)

18 (12.10)

Muslim

4 (1.40)

2 (1.50)

2 (1.30)

Other

54 (19.40)

32 (24.50)

22 (14.80)

Missing

2 (0.60)

1 (0.75)

1 (0.70)

Income level, $

⬍0.001

0–20K

26 (9.30)

16 (12.30)

10 (7.00)

21–40K

68 (24.30)

48 (36.60)

20 (13.40)

41–60K

77 (27.40)

40 (30.50)

37 (24.80)

61–80K

38 (13.40)

12 (9.20)

24 (16.20)

ⱖ80K

56 (20.00)

9 (6.80)

47 (31.60)

Missing

16 (5.60)

6 (4.60)

10 (7.00)

Health insurance

0.081

None

9 (3.20)

5 (3.80)

4 (2.70)

Private

224 (80.00)

98 (74.75)

126 (84.60)

Publicly funded

28 (10.10)

15 (11.50)

13 (8.60)

Unsure

16 (5.80)

12 (9.20)

4 (2.70)

Missing

3 (0.90)

1 (0.75)

2 (1.40)

K. Montgomery and M. Smith-Glasgow

S59

with more women in the older group identifying

their religion as Jewish (12.1% compared with 3.8%).

In contrast, there was a significantly higher percent-

age of women reporting their religion as Christian in

the younger group (36.7%) compared with the older

group (27.5%). Income levels were also significantly

higher in the older group, with 31.6% of the women

reporting a total annual household income of

ⱖ$80,000. In contrast, most respondents in the

younger group reported their annual income level to

be either between $21,000 and $40,000 (36.60%) or

$41,000 and $60,000 (30.5%). Health insurance sta-

tus was similar in the 2 groups, with the majority of

the participant’s reportedly carrying private insur-

ance. It should be noted that although race was not

significantly different (P

⫽ 0.06) between the 2

groups, the older group had more white participants

(61.7%) compared with the younger group (48.1%).

Knowledge and Health Beliefs

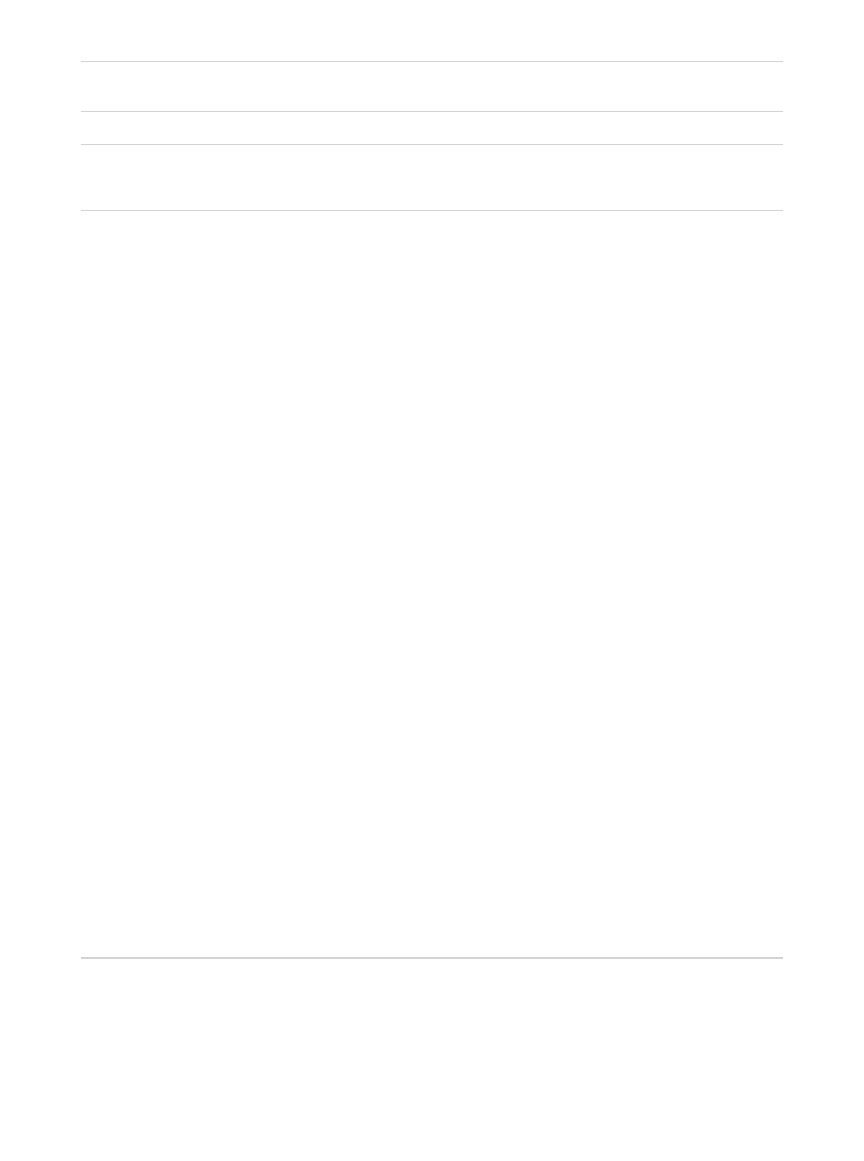

Results from the independent t test showed that

the groups were significantly different for knowl-

edge, t (277.55)

⫽ 3.00 (P ⫽ 0.003), and suscepti-

bility, t (227.33)

⫽ 4.21 (P ⬍ 0.001).

presents the comparison of frequency of correct

responses for the knowledge section of the ques-

tionnaire between the 2 groups, Also, as evident

from the sociodemographic differences presented

in

, the 2 groups were significantly differ-

ent in marital status, type of religion, and level of

income. These characteristics along with the re-

maining subdimensions of the HBM model acted

as covariates in the final ANCOVAs.

presents both unadjusted and ad-

justed means and variance (SD) for knowledge,

susceptibility, and seriousness for the 2 groups.

Before analysis, the data were checked and met the

following assumptions: (1) independence of obser-

vation; (2) normal distribution of the dependent

variables knowledge, susceptibility, and serious-

ness; (3) homogeneity of variance; and (D) linear

relationship between the covariates and the de-

pendent variables. Results indicate that after con-

Table II. Comparison of frequencies of correct responses for multiple-choice questions regarding HPV/cervical cancer

knowledge in women aged 18 to 26 years (n

⫽ 131) and 40 to 70 years (n ⫽ 149).

Frequency (%)

Group A (18–26 y), n

⫽ 131

Group B (40–70 y), n

⫽ 149

1. The virus associated with cervical cancer

is transmitted by

102 (77.9)

66 (44.3)

2. Cervical cancer and precancerous cells

are associated with the presence of

105 (80.2)

402 (26.8)

3. Cervical cancer can be diagnosed by

107 (81.7)

32 (21.5)

4. Prevention of cervical cancer may require

84 (64.1)

84 (56.6)

5. HPV can cause

74 (56.5)

98 (65.8)

6. HPV can live in the skin without causing

growths or changes

88 (67.7)

82 (55.8)

Risk factors (yes or no)

7. Multiple sex partners

104 (79.4)

100 (67.1)

8. Having genital warts

77 (58.8)

76 (51.7)

9. Sexual intercourse before 18

65 (49.6)

75 (50.3)

10. Taking illegal drugs

20 (15.3)

27 (18.1)

11. Having contracted any STIs

98 (76)

85 (57.8)

12. Smoking cigarettes

31 (23.7)

33 (22.3)

13. Poor diet or nutrition

69 (53.1)

79 (53.4)

14. Using tampons

86 (65.6)

101 (67.8)

15. Use of oral contraceptives (birth

control pills)

13 (10.2)

13 (8.8)

HPV

⫽ human papillomavirus; STIs ⫽ sexually transmitted infections.

Gender Medicine

S60

trolling for all the sociodemographic characteris-

tics and pertinent subdimensions of the HBM,

there was a significant difference between the

groups for knowledge only (F

1,265

⫽ 6.80, P ⫽

0.01), but not for susceptibility (F

1,265

⫽ 2.55, P ⫽

0.11). As evident in

, the differences in

adjusted means for knowledge are similar after

controlling for sociodemographic characteristics

and subdimensions, whereas that of susceptibility

and seriousness are lower.

It should be noted that the younger group of

women have a higher level of knowledge and

health belief scores compared with the older

group. Moreover, the ANCOVA revealed that the

sociodemographic covariates race and education

led to significant difference in knowledge. Based

on this finding, knowledge levels for different race

and education levels were plotted in separate

graphs (

and

Preventive Practices

Results of the analysis revealed significant differ-

ences between the groups for use of condoms (P

⬍

0.002), oral contraceptives (P

⬍ 0.001), Pap smear

(P

⬍ 0.048), and family member diagnosed with

HPV (P

⬍ 0.05), but not for cigarette smoking (P ⫽

1.00) and sexual involvement (P

⫽ 0.164) (

). Although 34.7% of the women in the younger

group reported using condoms regularly (usually

and always), only 18.4% of the women in the older

group reported doing so. The use of condoms was

low in the older age group, with 59.2% of the

women never using a condom during sexual activity,

compared with only 34.6% in the younger age

group. Almost half the women in the younger group

(43.8%) reported using oral contraceptives. In con-

trast, more women in the older age group (86.3%)

did not use oral contraceptives at the time of partic-

ipation. In response to the question of whether the

women knew anyone in the family with a history of

HPV/cervical cancer, a higher percentage (72.5%) of

women in the older age group reported not knowing

one compared with the younger age group (58.8%).

Table III. Adjusted and unadjusted mean (SD) for knowledge, susceptibility, and seriousness for younger and older groups

of women using sociodemographic factors as a covariate.

n

Unadjusted, Mean (SD)

P

Adjusted,* Mean (SD)

P

Knowledge

0.003

†

0.010

†

Group A (19–26 y)

129

8.57 (3.14)

8.57 (3.41)

Group B (40–70 y)

146

7.44 (3.41)

7.43 (3.38)

Susceptibility

⬍0.001

†

0.111

Group A (19–26 y)

129

29.09 (6.53)

28.12 (4.63)

Group B (40–70 y)

146

26.03 (4.63)

26.88 (5.88)

Seriousness

0.097

0.266

Group A (19–26 y)

129

20.26 (2.76)

20.19 (3.02)

Group B (40–70 y)

146

19.69 (2.78)

19.76 (2.98)

*

Adjusted means are based on ANCOVA analyses with the following covariates: race, education, marital status, religion, income, and

subdimensions.

†

P

⬍ 0.05; the P values for the unadjusted means are calculated for the t test and the P values for the adjusted means are calculated for

the ANCOVA.

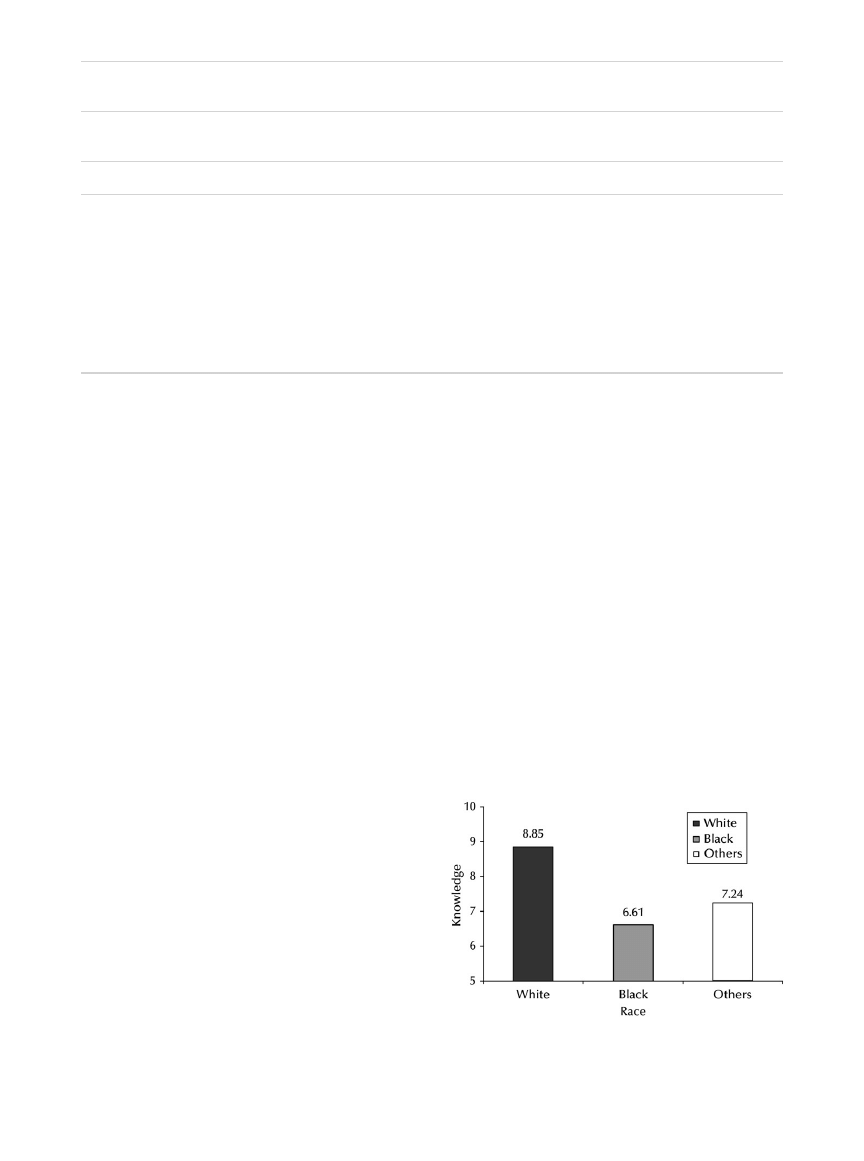

Figure 1. Means of knowledge by race for the study par-

ticipants (N

⫽ 280).

K. Montgomery and M. Smith-Glasgow

S61

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to determine the differences in

knowledge, health beliefs and perceptions, and

type of preventive practices in women aged 40 to

70 years compared with younger counterparts

aged 19 to 26 years who have typically been the

target of most national HPV public awareness and

prevention programs.

The results of this study partially support the

hypothesis that women aged 40 to 70 have less

knowledge regarding HPV and cervical cancer

knowledge, perceive themselves as less susceptible

to its acquisition, and may perceive HPV and cer-

vical cancer to be less serious than other diseases

compared with women aged 19 to 26. Although

this study demonstrated that the older age group

has less knowledge than the younger group, there

were no differences in susceptibility or seriousness

between the 2 groups.

Knowledge

Although the existence of HPV has been recog-

nized as a sexually transmitted infection for more

than half a century, discovery of HPV as a poten-

tial cause for cervical cancer that affects women

shortly after beginning their first sexual relation-

ship did not emerge until the 1970s.

The delin-

eation between the low-risk and high-risk types of

HPV was a breakthrough scientific development

⬍10 years ago.

Since then, younger women

have been the target of public health education

and prevention as well as vaccination campaigns;

therefore, it is not surprising that this study indi-

cates that older women have comparatively less

knowledge about HPV and cervical cancer than

the younger participants.

Compared with other studies, the findings of

this study regarding cervical cancer and HPV

knowledge in women aged 19 to 26 are not con-

sistent with previous findings in this population

using the same questionnaire.

The average

knowledge score reported in the study conducted

by Ingledue et al

using 428 college women was

6.8 out of 15, whereas the study by Denny-Smith

et al

reported an average score of 10.2 in women

of similar age. The study by Ingledue et al

did not

provide sufficient sociodemographic information

about their participants, whereas the study by

Denny-Smith et al

used 240 undergraduate nurs-

ing students with superior knowledge about med-

ical conditions compared with age-matched gen-

eral population. The findings from either study are

difficult to compare with these results. It should be

noted that the study by Ingledue et al

was per-

formed before the massive public educational

campaigns by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention and pharmaceutical companies to in-

crease awareness in the young adult population.

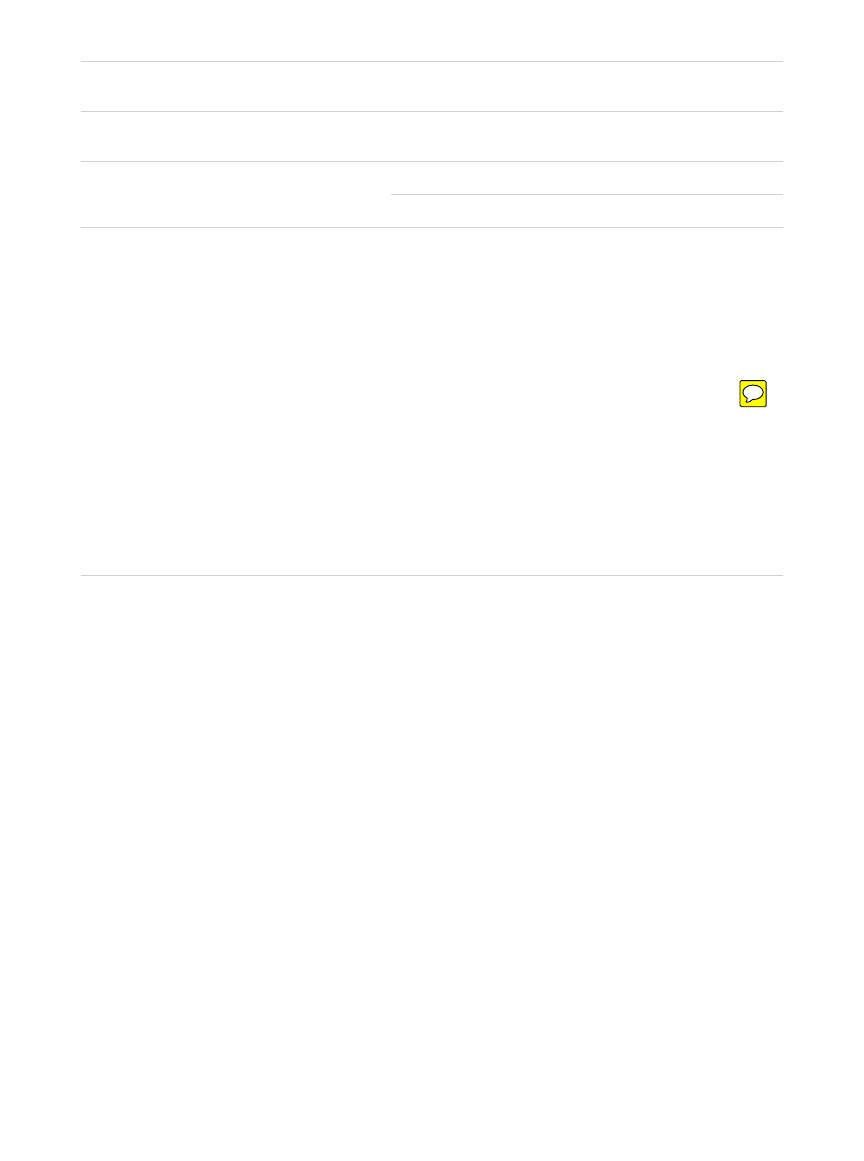

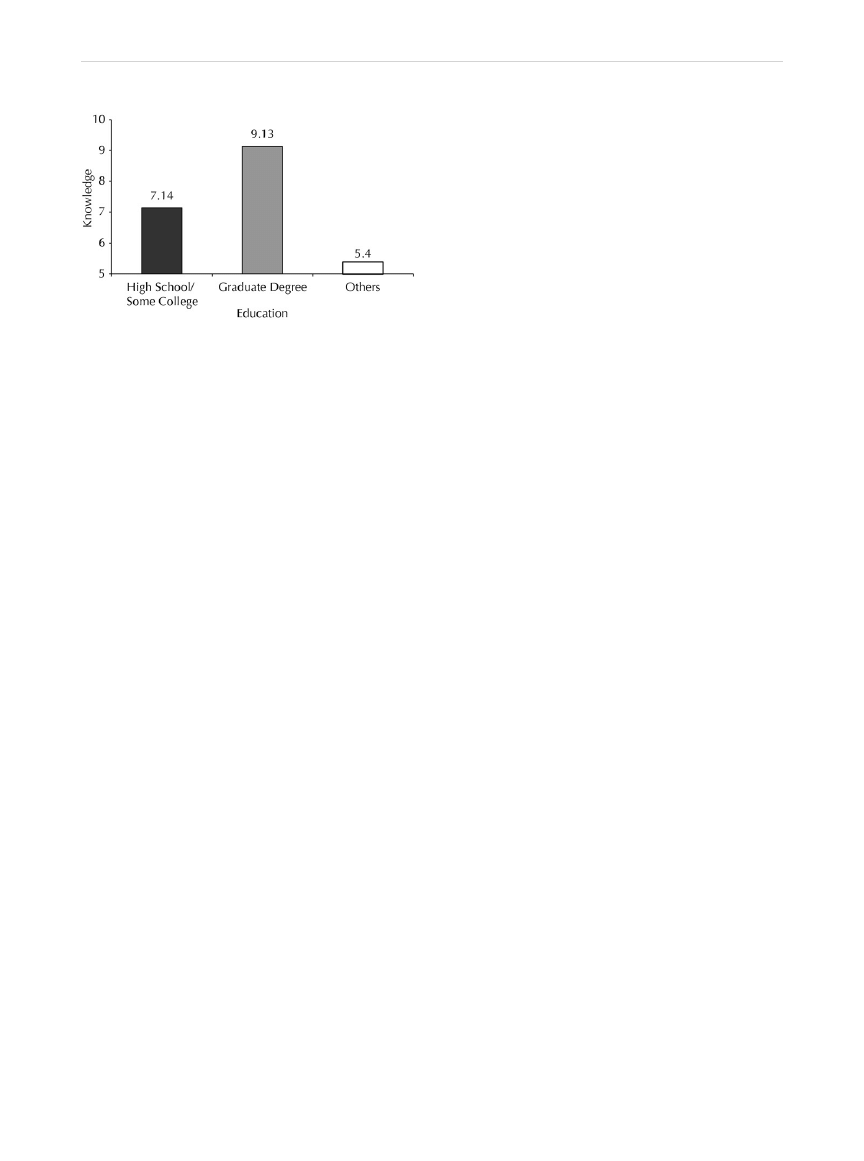

Finally, as suggested from

and

, knowl-

edge scores vary according to individual’s race and

education. White women appear to have higher

levels of knowledge compared with African Amer-

ican women and other minorities. Furthermore,

college graduates have greater knowledge compared

with high school graduates. It is possible that older

women whose ethnicity or educational attainment

place them in higher risk categories based on knowl-

edge of HPV and cervical cancer should be the prime

target of educational interventions involving HPV

and cervical cancer awareness.

Health Beliefs (Perceived Susceptibility and

Perceived Seriousness)

Contrary to the research hypothesis, this study

found no significant differences in perceived sus-

ceptibility to HPV and cervical cancer or in per-

ceived seriousness, after controlling for knowledge

and sociodemographic characteristics. Before con-

trolling for knowledge, the younger group of

women had a significantly higher level of per-

Figure 2. Means of knowledge for educational level of

study participants (N

⫽ 280).

Gender Medicine

S62

ceived risk than women in the older group. The

differences in knowledge may therefore be an im-

portant mediator between the 2 groups and their

perceived risk. However, the low internal consis-

tency in these measures renders any findings based

on these scales inconclusive.

Preventive Practices

The hypothesis that women aged 40 to 70 would

use preventive practices less than women aged 19

to 26 was only partially supported. As previously

described, women polled in the older age group

reported fewer sexual partners within the past 5

years and less condom use. Therefore, most sexu-

ally active women in this age group are in long-

term relationships and do not perceive themselves

at risk for a sexually transmitted disease, nor do

they appreciate the connection between HPV and

cervical cancer. Younger women, however, use

condoms more, are sexually intimate with more

sexual partners, and report a higher incidence of

oral contraceptive use than women in the older

Table IV. Comparison of frequency and percentage of participant responses to preventive practices in women aged 19 to

26 years and 40 to 70 years.

Preventive Practices

Total Sample

(N

⫽ 280),

100%

Group A

(Age 19–26 y, n

⫽ 131),

47%

Group B

(Age 40–70 y, n

⫽ 149),

53%

P*

Sexual experience, n (%)

0.16

Currently involved

71.43

76.34

67.11

Not currently involved

26.43

21.37

30.87

Never had sexual intercourse

1.79

2.29

1.34

Missing

0.36

0.00

0.67

Use of condoms, n (%)

Always

10.36

13.74

7.38

Usually

15.00

19.85

10.74

Sometimes

10.36

10.69

10.07

Occasionally

4.64

4.58

4.70

Rarely

10.71

14.50

7.38

Never

46.79

33.59

58.39

Missing

2.14

3.05

1.34

Use of oral contraceptives, n (%)

⬍0.001

Yes

76 (27.14)

57 (43.51)

19 (12.75)

No

199 (71.07)

73 (55.73)

126 (84.56)

Don’t know

1 (0.36)

0.00

1(0.67)

Missing

4 (1.40)

1 (0.80)

3 (2.00)

Cigarette smoking, n (%)

1.00

Yes

57 (20.36)

27 (20.61)

30 (20.13)

No

222 (79.29)

104 (79.39)

118 (79.19)

Missing

1 (0.36)

0.00

1 (0.67)

Pap smear, n (%)

0.05

Never

8 (2.86)

6 (4.58)

2 (1.34)

Within the past year

194 (69.29)

97 (74.05)

97 (65.10)

Had one but not within past year

75 (26.79)

28 (21.37)

47 (31.54)

Missing

3 (1.07)

0.00

3 (2.01)

Family member diagnosed with HPV, n (%)

0.05

Yes

50 (17.86)

28 (21.37)

22 (14.77)

No

185 (66.07)

77 (58.78)

108 (72.48)

Don’t Know

39 (13.93)

23 (17.56)

16 (10.74)

Missing

6 (2.14)

3 (2.29)

3 (2.01)

*

Significance P

ⱕ 0.05.

K. Montgomery and M. Smith-Glasgow

S63

group. The qualitative study (by Vanslyke et al

of 54 women age 18 to 60 found that women

identify 3 cervical cancer preventive measures:

having regular annual examinations by a health

care provider, having a Pap smear, and having an

awareness of changes in one’s own body.

Significance to Practice

As a caring profession, nursing is dedicated to the

health and wellness of all populations and is per-

fectly positioned to act as a catalyst to improve

knowledge, health beliefs, and preventive practice to

ensure optimal health promotion for all women.

This study challenges clinical nurse practitioners to

reinforce the primary goals of Healthy People 2020

to help individuals of all ages increase life expec-

tancy and improve their quality of life, as well as

reduce the number of new cancer cases and the ill-

ness, disability, and death caused by cancer. Gaps

found throughout existing literature in women’s un-

derstanding of HPV, a potentially deadly virus, sug-

gests the need for more comprehensive education

about preventing genital HPV, its possible sequelae,

and the significance of Pap and HPV screening for

cancer detection and prevention in women of all

ages. Knowledge related to HPV, its relationship to

cervical cancer, and cervical cancer itself is low in

younger and older women. Despite national cam-

paigns to educate young women, knowledge contin-

ues to be low. Therefore, practitioners need to em-

power women with comprehensive knowledge

regarding HPV, with a focus tailored to the appropri-

ate needs of their age population. Through collabor-

ative efforts, it is paramount that the nursing com-

munity fully addresses the deficiencies in HPV/

cervical cancer knowledge, perceived risk, and

preventive practices across the life span of both

women and men. In addition, information gained

through intervention research fosters the develop-

ment of multidisciplinary and multifaceted national

education campaigns designed to educate popula-

tions of all sociodemographic backgrounds. Last,

joining forces with political action campaigns to

reach out to minorities who are at the most increased

risk for cervical cancer will result in the preservation

of human life and the promotion of healthy behav-

ior changes.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be interpreted

in light of the several existing limitations. First, the

participants of this study were mostly residents

from an urban area; consequently, the findings

may not be generalized to other populations.

Second, this study relied on self-report with no

attempt to independently verify respondents’ in-

formation. In addition, although this study used

an anonymous questionnaire, limitations of a sur-

vey study may apply. Surveys provide only real-

time descriptions of behaviors and feelings of the

respondents, and responses cannot always be

taken as accurate descriptions of what the respon-

dents actually do or feel. This is especially true for

behavior that is contrary to generally accepted

norms of society, such as information regarding

sexual activity.

Some of these women may have

been unwilling to indicate that they have engaged

in controversial behaviors, thus skewing the re-

sults (social desirability bias).

Scientific advances continue to provide clini-

cians with updated information regarding HPV

and cervical cancer. The Awareness of HPV and

Cervical Cancer Questionnaire developed

⬎5 years

ago may not represent this current scientific infor-

mation.

Revision of this tool to reflect scientific

development and cultural beliefs is crucial to gain

a better understanding of knowledge, health be-

liefs, and preventive practices in all women.

Implications for Future Research

The findings of this study provides the basis for

understanding HPV and cervical cancer knowledge,

health beliefs, and preventive practices of women of

2 high-risk age groups (19 –26 and 40 –70 years).

However, this study did not investigate age on a

continuum throughout a woman’s life span. Conse-

quently, the findings are unable to reflect the range

of ages when knowledge decreases. The next logical

step is to investigate the age threshold at which

knowledge decreases. Furthermore, the tool of this

study needs to be refined to reflect current practice

patterns and levels of HPV and cervical cancer

knowledge. Most importantly, a thorough investiga-

tion of the impact of the differences in women’s

knowledge on their health beliefs and preventive

Gender Medicine

S64

practices in populations with a high prevalence and

risk of cervical cancer is essential to combat this dis-

ease. Finally, identifying deficiencies in the current

education campaigns and redesigning culturally sen-

sitive, age-appropriate educational awareness, and

health promotion will better equip women to win

the fight against cervical cancer.

Another vital area of research involves investi-

gating current practice patterns regarding HPV and

cervical cancer knowledge of health care providers.

New evidence regarding HPV and cervical cancer is

emerging at an explosive pace, and it is challeng-

ing for health care providers to stay current with

the copious amount of information. Determining

the level of HPV and cervical cancer knowledge of

caregivers will help researchers to identify whether

patients

have

access

to

the

appropriate

information.

CONCLUSIONS

Women aged 40 to 70 have decreased HPV and cer-

vical cancer knowledge compared with women aged

19 to 26 who have been the target of substantial

national educational campaigns. Unlike the younger

group of women, women aged 40 to 70 did not have

comprehensive sex education during their formative

years. Therefore, they did not have the opportunity

to make a connection between their sexual activity

and their risk of cervical cancer. This initial defi-

ciency is further complicated by the intentional ex-

clusion of women aged 40 and older from the na-

tional education campaigns. In addition, this study

suggests that the group that has the greatest risk of

cervical cancer (African American women aged

40 –50 with low education levels) is the same group

that health care providers have failed to educate the

most. African American women are 50% more likely

to be diagnosed with cervical cancer and are twice as

likely to die of the disease compared with white

women in the United States.

Until further re-

search is completed and age-appropriate educational

materials are developed, it is crucial that health care

providers increase the HPV and cervical awareness of

all women regardless of their age and perhaps enable

women to win the battle against this potentially fatal

disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Brian Crain for medical editing

and assistance with manuscript preparation.

Dr. Smith-Glasgow was principally responsible for

study conception and design and critical manuscript

revision. Ms. Montgomery primarily acquired and

analyzed study data, and drafted the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The symposium and publication of these proceed-

ings were supported by: The National Institutes of

Health, The Drexel University College of Medi-

cine, The Helen I. Moorehead, MD Foundation,

The Doris Willig, MD Foundation, The Institute

for Women’s Health and Leadership, and The Cen-

ter for Women’s Health Research at the Drexel

University College of Medicine.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009

Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance.

www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/exordium.htm.

Accessed

March 13, 2011.

2. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al. Preva-

lence of HPV infection among females in the

United States. JAMA. 2007;297:813– 819.

3. Parkin D. The global health burden of infection-

associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer.

2006;118:3030 –3044.

4. Muñoz N, Fransechi S, Bosetti C, et al. Role of

parity and human papillomavirus in cervical can-

cer: the IARC multicentric case-control study. Lan-

cet. 2002;359:1093–1101.

5. World Health Organization. Immunization, Vac-

cines and Biologicals. Human papillomavirus

(HPV).

http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/

Accessed March 13, 2011.

6. National Cancer Institute. A Snapshot of Cervical

Cancer.

http://www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/serving

people/snapshots/cervical.pdf.

Accessed March

13, 2011.

7. Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, et al. A popula-

tion-based study of all grades of cervical neoplasia in

rural Costa Rica. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:6464–6473.

8. Lazcano-Ponce E, Herrero R, Muñoz N, et al. Epi-

demiology of HPV infection among Mexican

K. Montgomery and M. Smith-Glasgow

S65

women with normal cervical cytology. Int J

Cancer. 2001;91:412– 420.

9. Molano M, Posso H, Weiderpass E, et al. Preva-

lence and determinants of HPV infection among

Colombian women with normal cytology. Br J

Cancer. 2002;87:324 –333.

10. Muñoz N, Méndez F, Posso H, et al. Incidence,

duration, and determinants of cervical human

papillomavirus Infection in a cohort of Colombian

women with normal cytological results. J Infect

Dis. 2004;190:2077–2087.

11. Baer H, Allen S, Braun L. Knowledge of human

papillomavirus infection among young adult men

and women: implications for health education and

research. J Community Health 2000;25:67–78.

12. Burak LJ, Meyer M. Using the health belief model

to examine and predict college women’s cervical

cancer screening beliefs and behavior. Health

Care Women Int. 1997;18:251–262.

13. Ingledue K, Cottrell R, Bernard A. College wom-

en’s knowledge, perceptions, and preventive be-

haviors regarding HPV and cervical cancer. Am J

Health Studies. 2004;19:28 –34.

14. Vail-Smith K, White D. Risk level, knowledge, and

preventive behavior for HPV among sexually active

college women. J Am Coll Health. 1992;40:227–230.

15. Montgomery K, Rosen-Bloch J, Bhattacharya A,

Montgomery O. Human papillomavirus and cervi-

cal knowledge, health beliefs, and preventative

practices in older women. J Obstet Gynecol Neo-

natal Nurs. 2010;39:238 –249.

16. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:

155–159.

17. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM. Health Behavior and

Health Education. Theory, Research and Practice.

San Francisco, Calif: Wiley & Sons; 2002.

18. Denny-Smith T, Bairan A, Page M. A survey of

female nursing students’ knowledge, health be-

liefs, perceptions of risk, and risk behaviors

regarding human papillomavirus and cervical

cancer. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:62– 69.

19. Moscicki A, Hills N, Shiboski S, et al. Risks for

incident human papillomavirus infection and low-

grade squamous intraepithelial lesion develop-

ment in young females. JAMA. 2001;285:2995–3002.

20. Koutsky L, Ault K, Wheeler C, et al, Proof of Prin-

ciple Study Investigators. A controlled trial of hu-

man papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. N Engl J Med.

2002;347:1645–1651.

21. Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, et al. Epidemi-

ologic classification of human papillomavirus

types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl

J Med. 2003;348:518 –527.

22. Vanslyke J, Baum J, Plaza V, et al. HPV and cervical

cancer testing and prevention: knowledge, be-

liefs, and attitudes among Hispanic women. Qual

Health Res. 2008;18:584 –596.

23. US Department of Health and Human Services.

Healthy People 2020.

Accessed March 13, 2011.

24. Zia H. Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of

an American People. New York: NY: Farrar, Straus

& Giroux; 2000.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: rec-

ommendations of the Advisory Committee on Im-

munization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal

Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1–24.

26. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures

2009.

http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfacts

figures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-

2009.

Accessed March 13, 2011.

27. Cates JR, Brewer NT, Fazekas K, et al. Racial differ-

ences in HPV knowledge, HPV vaccine acceptabil-

ity, and related beliefs among rural, southern

women. J Rural Health. 2009;25:93–97.

Address correspondence to:

Kymberlee Montgomery, DrNP, MSN, College of Nursing & Health Professions, 1505

Race St Ms 501, Philadelphia, PA 19102. E-mail:

kimberlee.a.montgomery@drexel.edu

Gender Medicine

S66

Document Outline

- Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Knowledge, Health Beliefs, and Preventive Practices in ...

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Knowledge health beliefs and preventive practicies

Knowledge of cervical cancer and screening practices of nurses at a regional hospital in tanzania

Cervical Cancer Prevention and Early american cancer society

Morbidity and mortality due to cervical cancer in Poland

What do British women know about cervical cancer symptoms and the risks

Quality of life and disparities among long term cervical cancer suvarviors

Women s knowledge about cervical cancer

health behaviors and quality of life among cervical cancer s

New technologies for cervical cancer screening

Comparison of Human Language and Animal Communication

Menagement Dile in cervical cancer

Human Relations and Social Responsibility

Alternative approaches to cervical cancer screening — kopia

HUMAN RIGHTS AND THEIR IMPORTANCE goood

Papilloedema, Papillitis and Pseudopapillitis

[Mises org]Hayek,Friedrich A A Free Market Monetary System And Pretense of Knowledge(1)

Chater N , Oaksford M Human rationality and the psychology of

New technologies for cervical cancer screening

więcej podobnych podstron