English Historical Review Vol. CXXIII No. 505

© The Author [2008]. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

Advance Access publication on November 5, 2008

doi:10.1093/ehr/cen276

The De Obitu Willelmi : Propaganda for the

Anglo-Norman Succession, 1087 – 88?*

T he De obitu Willelmi is an intriguing text of just 654 words, purporting

to be an account of the deathbed of William the Conqueror, and

describing how he divided his realms between his eldest son Robert

‘ Curthose ’ , who received Normandy, and the younger William ‘ Rufus ’

who became king of England. It survives only as a rare appendage to

the

Gesta Normannorum Ducum

of William of Jumièges and his

continuators, being found in full at the end of a single manuscript,

although the fi rst 52 words are also found in a closely related copy.

1

These, together with a fragmentary and apparently independent

manuscript which lacks any part of the De obitu Willelmi , are the only

extant copies of the B redaction of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum ,

and the two containing the De obitu Willelmi date to the late eleventh

or early twelfth century. This paper re-examines the evidence for the

date and authorship of the De obitu Willelmi , and proposes a context

for it in the aftermath of the Conqueror’s death.

Fourteen of the forty-seven surviving MSS of the Gesta Normannorum

Ducum

are in England, including the three manuscripts of the B

redaction. All these three are of an early date; the other redactions

continued to be copied into the thirteenth century and beyond. B2,

which alone contains the complete text of De obitu Willelmi , is a

Durham manuscript and is known to have been corrected in the early

twelfth century. Palaeographic analysis, comparing it with other Durham

manuscripts, has indicated a date in the last decade of the eleventh

century or the fi rst quarter of the twelfth.

2

Gullick has subsequently

identifi ed Symeon of Durham’s hand in both the text and its annotations,

confi rming its terminus ante quem as Symeon’s death just before 1130.

3

In addition to De obitu Willelmi and some short anecdotes, this redaction

includes a note of the death in 1092 of Nicholas, bastard son of Duke

* I am grateful to my supervisor Professor Nicholas Brooks and to Dr Elizabeth van Houts for

their encouragement and their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

1 . Part of the B2 manuscript of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum, London, British Library, MS

Harley 491, fos. 3r – 46v; the B1 manuscript, Oxford, Magdalen College MS 73, fos. 70r – 117v; B3,

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson G. 62, fos. 71v – 73r. The classifi cation of these manuscripts

is taken from E.C.M. van Houts, ed., The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumièges,

Orderic Vitalis and Robert of Torign i (2 vols, Oxford, 1992), I: Introduction and Books I – IV, xcv –

cxix. De obitu Willelmi is translated in Gesta Normannorum Ducum VII, ed. van Houts, ii, 185 – 191.

2 . A. Sapir and B.M.J. Speet, De Obitu Willelmi: Kritische beschouwing van een verhalende bron over

Willem de Veroveraar uit de tijd van zijn zonen (Amsterdam, 1976), 3 – 4. I am grateful to Dr A. Sapir

Abulafi a for making this text available to me and to Mr Eric Idema for translating it into English.

3 . M. Gullick, ‘ The Hand of Symeon of Durham: Further Observations on the Durham

Martyrology Scribe ’ , in D. Rollason, ed., Symeon of Durham. Historian of Durham and the North.

Studies in North-Eastern History (Stamford, 1998), 14 – 31.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1418

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

Richard III and therefore the Conqueror’s older cousin; it therefore

post-dates this event.

4

An initial dating range for the B2 redaction and

De obitu Willelmi is thus fi xed as 1092 to c. 1125. If, however, as suggested

(but subsequently rejected) by Sapir and Speet, De obitu Willelmi was

not composed as part of the B redaction, but circulated independently

before being attached to it, then its terminus post quem is fi xed only by

the date of the Conqueror’s death in 1087. van Houts considered that

this was a possibility. She proposed that the other additions to the B

redaction are too different in style from De obitu Willelmi to share a

common author. ‘ The B redactor, anxious to include all the information

about the dukes and the kings that he could fi nd, used De obitu Willelmi

but did not write it himself. ’

5

The text itself was fi rst edited by Marx in 1914, who described it as

the product of ‘ an anonymous monk of St Stephen’s Caen ’ because it

contains a description of the Conqueror’s tomb and the epitaph on it.

6

Since then it has had fl

uctuating fortunes in Anglo-Norman

historiography. David used it uncritically in his 1920 portrait of Robert

Curthose,

7

and in 1964 Douglas wrote, ‘ It is a remarkable description,

and while … it must be received with some discrimination, its simplicity

and circumstantial detail command confi dence, and it is not to be set

aside. ’

8

In 1971 Le Patourel said

9

As a precise and matter-of-fact account it carries conviction; whereas

Orderic’s description was written a generation later, his interpretation bears

the stamp of that generation and the whole has been worked over to make a

literary set-piece. It is better to follow the earlier statement, certainly for any

argument based on detail.

This despite the fact that in 1965 both Barlow and Loyn had noted that

certain passages in De obitu Willelmi describing the Conqueror’s personal

habits had been lifted from Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne, the Vita

Karoli Magni.

10

A major study by Engels then revealed that De obitu Willelmi is a

pastiche of two ninth-century sources, Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne

and the life of Louis the Pious by the anonymous ‘ Astronomer ’ (the Vita

4 . Sapir and Speet, Kritische , 18.

5 . Gesta Normannorum Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, lxiv – lxv.

6 . J. Marx, Guillaume de Jumièges, Gesta Normannorum Ducum. Edition Critique (Rouen and

Paris, 1914), 145 – 8.

7 . C.W. David, Robert Curthose, Duke of Normandy (Cambridge, 1920), 40 – 1.

8 . D.C. Douglas, William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact upon England (London, 1964),

371.

9 . J. Le Patourel, ‘ The Norman Succession, 996 – 1135. ’ ante , lxxxvi (1971), 225 – 50 at 232.

10 . F. Barlow, William I and the Norman Conquest (London, 1965), 43, 177ff.; H.R. Loyn, The

Norman Conquest (London, 1965), 193; O. Holder-Egger, ‘ Einhardi Vita Karoli Magni. ’ Monumenta

Germaniae Historica, Scriptores rerum Germanorum , xxv (1911).

1419

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

Hludouuici ).

11

Engels demonstrated that the fi rst part of De obitu

Willelmi , describing the Conqueror’s deathbed and arrangements for

the succession, is lifted from Vita Hludouuici , while the latter part is

a series of disconnected extracts from Vita Karoli Magni , describing

his habits and physical appearance. The parallel texts are reproduced

here in Appendix I . Some historians have seen this as destroying the

credibility of De obitu Willelmi as a useful text: Bates said succinctly, ‘ It

is of little value, ’

12

while Barbara English concluded it was

13

merely a piece created by someone who wanted a short biography of the

Conqueror and copied out the most appropriate sources to which he had

access, altering them in the light of the general (and not specialised)

knowledge available to him … As De obitu Willelmi can so easily be

demonstrated to be merely an echo of older texts, then Orderic Vitalis ’

account assumes a greater importance.

It is certainly true that as an ‘ original ’ source for information about the

last days of the Conqueror, De obitu Willelmi now needs to be seen in a

new light. But nevertheless it was written, and copied into a manuscript

of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum . Moreover it does not contain the

most obvious information nor is it copied in the most obvious way

from the most suitable sources. This raises the question of who might

have written it and why. First, though, it will be helpful to explore

the implications of the detailed work on the text itself done by Engels

and by Sapir and Speet in the light of the new edition of the Gesta

Normannorum Ducum by van Houts.

As Engels demonstrated, De obitu Willelmi is largely composed of

extracts from its two models. Of its 654 words, the fi rst 440 describe the

Conqueror’s last days, and of these 330 are from the Vita Hludouuici ,

with a further 77 being the title and essential changes to names, etc. The

second part describes William in 214 words, of which 181 are taken from

the Vita Karoli Magni . Again, 32 of the ‘ new ’ words are essential changes

to accommodate the different people and places involved. Thus, of the

654 words, only 34 are ‘ voluntary ’ changes. Various hypotheses to explain

this close adherence could be suggested, of which the two extremes on

the spectrum are as follows. Either the topoi themselves had widely

understood symbolic value at the turn of the twelfth century and the

texts were so well known by the intended audience that the symbolism

would be enhanced by a close use of the models, or there was a need for

a written account of the last days of the Conqueror and his choice of

11 . L.J. Engels, ‘ De obitu Willelmi ducis Normannorum regisque Anglorum: Texte, modèles,

valeur et origine ’ , in Anon, Mélanges Christine Mohrmann, Nouveau recueil offert par ses anciens

élèves (Utrecht/Anvers, 1973), 209 – 55.

12 . D. Bates, William the Conqueror (London, 1989), 180.

13 . B. English, ‘ William the Conqueror and the Anglo-Norman Succession ’ , Historical Research ,

lxiv (1991), 221 – 36 at 227.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1420

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

successors, meeting the expected formulae without necessarily adhering

too closely to the facts, and these models supplied a useful short cut.

The generous use of the Charlemagne model fi ts well with both

hypotheses. Charlemagne’s legendary status was widely known in both

lay and ecclesiastical milieux, and Einhard’s text was readily available:

the most recent study reveals 134 surviving manuscripts, of which 24 are

eleventh century or earlier.

14

Any ruler might be compared with

Charlemagne, and especially one such as William the Conqueror, for

whom at least some of the parallels were accurate. Similar comparisons

are made, for example, in the Carmen de Hastingae Proelio : ‘ promptior

est Magno largior et Carolo ’ and by William of Malmesbury, who quotes

the

Vita Karoli Magni

several times.

15

The Conqueror endowed

monasteries generously and reformed the church in Normandy and

England, and had undoubtedly built up a greatly increased ‘ empire ’ .

But despite its superfi cial suitability, there are some curious features

of the use of the Vita Karoli Magni . First, as Engels showed, the selected

passages are used in order, with one exception where a small phrase of

chapter 22 is inserted after the sentence from chapter 25. This is also the

only place where the text is not followed exactly, voce clara being replaced

by voce rauca in De obitu Willelmi . Why should this one change be

inserted out of sequence? Does it neatly serve to lend credence to the

description, by highlighting a well-known feature of the deceased king?

After all, many more people would have heard his voice than would

have been familiar with his domestic habits.

16

Is it signifi cant that the

substituted word occupies the same space on the line, so a copyist would

not be confused by line breaks occurring in different places thereafter?

Or is this to read too much into a simple alteration?

Secondly, the amalgamation of several small extracts from the model

necessitates adjustments where they join. Most of these are managed

easily, but in one place in particular the junction is left unpolished: the

burial place of the Conqueror was already agreed, but in the Vita Karoli

Magni there is a debate about a suitable site for Charlemagne. This is

omitted from De obitu Willelmi , but its echo remains as the copyist

picks up at ‘ At length all were agreed that there was no better place … ’

and inserts ‘ than that which had already been agreed ’ . This slight

14 . M.M. Tischler, ‘ Einharts Vita Karoli; Studien zur Entstehung, überlieferung und Rezeption ’ ,

Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Schriften , xlviii (2001), 20 – 44.

15 . F. Barlow, ed., Carmen de Hastingae Proelio of Guy Bishop of Amiens (Oxford, 1999), 44 – 5,

line 736; William of Malmesbury, e.g.: ‘ Iustae fuit staturae, immensae corpulentiae, fatie fera, fronte

capillis nuda, roboris ingentis in lacertis, ut magno sepe spectaculo fuerit quod nemo eius arcum tenderet

… ’ Gesta Regum Anglorum III. 279; R.A.B. Mynors, R.M. Thomson and M. Winterbottom, eds.,

William of Malmesbury: Gesta Regum Anglorum. The History of the English Kings. Two Volumes

(Oxford, 1998 – 99), i, 508 and see ii, 256 – 8.

16 . There is an echo of this attribute in William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum III.

281: ed. Mynors et al. , 510 – 11, ‘ it was his practice deliberately to use such oaths, so that the mere

roar from his open mouth might somehow strike terror into the minds of his audience ’ .

1421

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

roughness might suggest that the De obitu Willelmi was produced

carelessly, or in haste.

Thirdly, the model is largely abandoned towards the end, for the

description of the funeral arrangements and epitaph. The role of Rufus

in causing the tomb to be built is stressed, and an epitaph is then given.

But this epitaph differs somewhat from that given by Orderic Vitalis in

his Ecclesiastical History, which Sapir and Speet have established is

almost identical to the version copied down at the tomb in 1522 and

recorded by Charles de Bourgueville in 1588. This could indicate that

Orderic’s is the original, and that the one in De obitu Willelmi is a

corrupted version, but as Sapir and Speet pointed out, it could also

mean that the 1522 copyist relied on Orderic’s Ecclesiastical History to

fi ll lacunae in the engraved inscription, in which case De obitu Willelmi

could contain the original version.

17

In favour of the De obitu Willelmi

version being the original, van Houts has identifi ed another fi fteenth-

or sixteenth-century copy of the epitaph, the same as that in the B2

manuscript,

18

but unless the links between the manuscripts can be

proved, all that can be said is that there was a continuing tradition of

copying the B2-type epitaph in England.

In contrast to the use of the Vita Karoli Magni as a model, the use of

the Vita Hludouuici does not sit comfortably with the fi rst hypothesis,

being neither an obvious nor common topos for the life of a great ruler.

Louis faced three major rebellions by his sons, failed to live up to his

great father’s standards and was once forced to abdicate for a year. If the

source was understood, it was unfl attering; if, as is more likely, it was

relatively unknown in Anglo-Norman society, how readily available was

it for copying, and what prompted the choice?

Twenty-two manuscripts of the Vita Hludouuici survive, but only

fi ve are eleventh century or earlier.

19

There may of course have been

many more in the medieval period, and it is possible that it has survived

less well than the Vita Karoli Magni . But nevertheless it seems relatively

scarce. Of these fi ve manuscripts, four now have the two texts bound

adjacent to each other, so one problem is readily resolved: even if the

Vita Hludouuici

was not as widely available as Einhard’s Life of

Charlemagne, it does seem to have travelled with it. Moreover the

17 . Sapir and Speet, Kritische , 36; Orderic Vitalis ’ Historia Ecclesiastica VIII.1: M. Chibnall, ed.,

The Ecclesiastical History of Orderic Vitalis. Historia Ecclesiastica. Six Volumes (Oxford, 1069 – 1978),

iv, 110 – 13 [ Oderic Vitalis , ed. Chibnall]; C. de Bourgueville, Les recherches et antiquitez de la ville et

université de Caen et lieux circonvoisins des plus remarquables (Caen: 1588) (cited in Sapir and Speet,

Kritische , 36). Orderic’s version of the epitaph is included in this study at the end of Appendix I ,

for comparison. Although Orderic’s autograph copy of Books VII and VIII had probably

disappeared from the St Evroul library by 1522, a late twelfth-century copy was still at St Etienne

Caen. See Oderic Vitalis : ed. Chibnall, iv, xiii – xv.

18 . Gesta Normannorum Ducum : ed. van Houts, ii, 189, footnote 7; the manuscript is London,

British Library, Cotton Titus A. XIX, fo. 114v.

19 . E. von Tremp, ‘ Theganus Gesta Hludowici imp. et Astronomus Vita Hludowici ’ , Monumenta

Germaniae Historica, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum , lxiv (1995), 33 – 4 and 123 – 33.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1422

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

manuscript of the Vita Hludouuici which von Tremp has identifi ed as

being closest to the text used for De obitu Willelmi is one of these four.

This copy, which originated near Chartres, is the only one with the

same wording as De obitu Willelmi for the list of regalia granted to

Rufus.

20

Here then is a partial explanation for the choice of the

‘ Astronomer’s ’ text as a model: it may have been to hand when the

copyist was making his extracts from the

Vita Karoli Magni and

composing De obitu Willelmi .

The use of the Vita Hludouuici in De obitu Willelmi cannot, however,

be dismissed so lightly. If it does not fi t with the fi rst hypothesis, it still

fi ts the second, and the possible signifi cance of this merits further

investigation. Unlike the Vita Karoli Magni , it has been used (with one

small but very important exception) as a sequence of extracts, selected

from three consecutive chapters, but within this material a quarter has

been changed. The one place where the text has been rearranged has a

crucial effect. The phrase ‘ which with God and the leading men of the

palace as witnesses he had already granted to him a long time previously ’

is carried forward to make it refer directly to the prodigal son (Robert

Curthose), not to the favoured heir (Rufus).

21

The resulting emphasis in this fi rst part of De obitu Willelmi is

distinctive. As Engels noted, there is no mention of the youngest son,

Henry, despite there being a place for him in the ‘ Astronomer’s ’ model.

Word for word, 11% is the title, introduction and conclusion, linking

the description to the Conqueror; 19% concerns his sickness, last rites

and death; 11% his division of the treasury for pious bequests; 10% is a

list of witnesses, only 3% describes the promise of the regalia to Rufus,

while a full 46% describes the rift with Curthose, his unsuitability for

rule and his father’s reluctant agreement to confi rm him as duke of

Normandy. This part alone takes up almost a third of the whole De

obitu Willelmi , suggesting that the major aim of the author was to stress

the Conqueror’s disillusionment with his eldest son. This effect is also

emphasised by placing these extracts at the beginning of De obitu

Willelmi , instead of after the description of the Conqueror in life,

which would be a more conventional order to adopt. Indeed, De obitu

Willelmi does not seem to fi t into any contemporary literary category,

which might point to a particular and unusual motive for its

composition.

20 . E. von Tremp, ‘ Die Uberlieferung der Vita Hludowici imperatoris des Astronomus ’ ,

Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Studien und texte , i (1991), 17 – 19 and 58 – 60; I would like to

thank Mr Charles West for his help translating this text. Of these fi ve early manuscripts, one [Paris

B.N., lat. 5943 A] is the autograph of Ademars of Chabannes, the other four originate, respectively,

in northern France, Trier, Chartres and St-Germain-des-Prés. The manuscript von Tremp identifi ed

as the exemplar for De obitu Willelmi is the early to mid eleventh-century Chartres ‘ P1 ’ manuscript,

Paris B.N. lat. 5354, which includes Vita Karoli Magni on fos. 50r – 61v and VH on fos. 61v – 85v. But

see Gesta Normannorum Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, lxiii – lxiv.

21 . See Appendix I . ‘ quam/quem Deo teste et proceribus palatii ille secum et ante se largitus ei

fuerat ’ .

1423

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

The De obitu Willelmi states clearly that on his deathbed the Conqueror

was at fi rst minded to disinherit Curthose completely, and was reluctantly

persuaded to grant him Normandy, predicting as he did so that it would

soon descend into chaos. Engels suggested that De obitu Willelmi was

composed in England in the fi rst few years of the twelfth century, before

Curthose was deposed at the Battle of Tinchebrai (1106) and when Normandy

was indeed sliding into chaos. Against this, Sapir and Speet decided that the

omission of Henry, despite the mention of a third brother in the Vita

Hludouuici model, must mean that it was composed before 1100.

There is a third possible piece of dating evidence which should be

taken into account here, namely the epitaph with which De obitu

Willelmi ends. Orderic Vitalis names Otto the Goldsmith as the man

chosen by Rufus to make the tomb, and describes how from among

many epitaphs written, that composed by Thomas of York (1070 – 1100)

was selected ‘ because of his metropolitan dignity ’.

22

The combination

of this fl attering emphasis on the archbishop’s poem with the deliberate

omission of Henry, which suggests that he was of no relevance, together

point strongly to a date before 1100.

Sapir and Speet also concluded that since the B redaction of Gesta

Normannorum Ducum refers to the death of Abbot Nicholas in 1092,

this must give the terminus post quem. Their fi rst hypothesis was that De

obitu Willelmi could have been written in the Rouen area at the time of

Rufus’s visit to Normandy between late 1096 and early 1097 (by which

time Curthose was preparing to depart on Crusade or had already left)

and they suggested furthermore that Rufus might then have built the

tomb for which he is commended in De obitu Willelmi . Their second

hypothesis, which they subsequently rejected, was that De obitu Willelmi

might initially have circulated independently from the

Gesta

Normannorum Ducum (in which case the 1092 terminus post quem

disappears) and they suggested rather unconvincingly that De obitu

Willelmi might in such a case have been produced in association with

the Treaty of Rouen in 1091, at which Curthose and Rufus mended their

quarrel and then took arms against Henry.

23

If, however, De obitu Willelmi was written separately and only added

to the end of the B2 manuscript later, the terminus post quem is actually

September 1087, the date of the Conqueror’s death. Several factors

should be considered here. First, there is the curious fact that the Vita

Hludouuici manuscript closest to that used for De obitu Willelmi is from

near Chartres, but all three surviving manuscripts of the B redaction of

Gesta Normannorum Ducum are in England, as are the two fourteenth-

century copies of excerpts from it.

24

There is no continental tradition of

22 . Oderic Vitalis VIII.1: ed. Chibnall, iv, 110 – 11.

23 . Engels, De obitu Willelmi ducis , 253 – 5; Sapir and Speet ( Kritische ), 30 – 4.

24 . Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 138, 167 – 77, and London, College of Arms, MS1,

fos. 176r – 179v. Gesta Normannorum Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, cxix.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1424

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

including

De obitu Willelmi

in the

Gesta Normannorum Ducum .

Secondly, even in England there is no surviving evidence for a continuing

tradition: there are later copies of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum of

English provenance, but none include De obitu Willelmi .

25

Thirdly, De

obitu Willelmi does not generally seem to have been employed as a

source for later accounts of the Conqueror’s death, even in England.

There may be faint echoes of its assertion that he had to be persuaded

to divide his lands, in the Gesta Regum Anglorum , but the latest edition

emphasises the similarity somewhat unwarrantedly, rendering

‘ Normanniam inuitus et coactus Rotberto, Angliam Willelmo … delegauit ’

as ‘ Reluctantly and under pressure he entrusted Normandy to Robert;

England he gave to William ’ .

26

William of Malmesbury was writing in

the reign of Henry I, while Curthose was in prison, so the stress achieved

by the word order here is not too surprising, but the addition of the

extra English verb lends it additional weight. A second possible slight

echo of De obitu Willelmi ’ s detail is in John of Worcester (and following

him Symeon of Durham), which at this point in the narrative includes

material not in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, notably the release of Odo,

and also omits Henry. Otherwise, De obitu Willelmi ’ s details are not

shared with other sources.

Overall, the impression is that De obitu Willelmi , and perhaps also

the B2 redaction of the Gesta Normannorum Ducum , is something of a

dead end, divorced from the main stream of the Gesta Normannorum

Ducum and the wider tradition of historical writing. It is a text which

now seems geographically removed from its supposed Norman origins,

which has not been copied in the way that other manuscripts in the

Gesta Normannorum Ducum family have, and which does not appear to

have infl uenced subsequent authors. Wace, writing in Normandy in the

third quarter of the twelfth century, uses some of the anecdotes which

are interpolated into the B redaction of Gesta Normannorum Ducum ,

but includes nothing which suggests that he was familiar with the De

obitu Willelmi

. Indeed the whole tenor of his description of the

Conqueror’s deathbed is markedly different from that in De obitu

Willelmi , and a more likely source here is Orderic Vitalis.

27

It is unlikely

that in the middle ages, De obitu Willelmi would have been set aside as

an unreliable blending of its two ninth-century sources, since it is merely

25 . For example, a fourteenth-century copy of the D redaction from Whalley Abbey, Lancashire

(Cambridge, Trinity College MS O.1.17, fos. 212v – 244r) and a fi re damaged and now divided late

twelfth-century copy of the F redaction from Reading Abbey, which was listed in the 1191 × 93

Cartulary of Reading (London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A. VIII fos. 5r – 100v +

Cambridge, Gonville and Caius, MS 177/210), van Houts nos D4 and F7; Gesta Normannorum

Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, cii – ciii and cxii – cxiii.

26 . Gesta Regum Anglorum III.282: eds. Mynors et al. , i, 510 – 11.

27 . E. van Houts, ‘ Wace as Historian ’ , in G.S. Burgess and E. van Houts, eds., The History of

the Norman People: Wace’s Roman de Rou (Woodbridge, 2004), xxx – lxii, xxxviii; Oderic Vitalis , ed.

Chibnall, iv, xxi – xxii.

1425

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

an extreme example of the common practice of drawing from older

models and topoi. Contemporary writers might rather have been

impressed by the parallels made. An alternative explanation is that it

had served its particular purpose by the early twelfth century, and it

was only by chance that it survived at all.

There is nothing here which means that De obitu Willelmi must have

been included in the B redaction of Gesta Normannorum Ducum from

the beginning, and some justifi cation for suggesting that it might have

been added later. If this were the case, De obitu Willelmi could be an

independent text, composed at some point in the reign of William

Rufus, aiming primarily to discredit Curthose but also assuming that

Henry was of no account. Since Henry was more important once

Curthose had left for the Crusade,

28

this supports the idea that De obitu

Willelmi was composed before 1097. This would mean a return to the

old view of it as much the earliest account of the death of the Conqueror,

signifi cantly earlier than the date suggested by Engels, and probably

earlier than Sapir and Speet’s favoured date of 1096 – 97. van Houts

proposed that De obitu Willelmi predates 1100, and called it ‘ a piece of

propaganda in favour of King William Rufus, too different from the

anecdotes [inserted in the B redaction] to come from the same pen ’ . If

this is so, there is no reason why it could not have circulated independently

for some time before it was incorporated.

29

If one accepts that De obitu Willelmi was written within 13 years of

the Conqueror’s death, and probably within a decade, it achieves a new

importance, not necessarily for the surface facts it presents, but for the

light it might shed on the situation in the fi rst part of Rufus’s reign. The

remainder of this study will consider why and by whom De obitu

Willelmi might have been written, in order to see if a coherent hypothesis

for its existence can be achieved.

As Engels stressed, a key to understanding De obitu Willelmi is to

consider the places where it differs from its models, since these are likely

to result from deliberate choice.

30

An obvious feature is the men named

in the text. A comparison of those named at the deathbed in the Vita

Hludouuici with those in De obitu Willelmi shows that only three

‘ unnecessary ’ changes were made. The younger son of the king was

omitted, and two court offi cials, John ‘ medicus ’ and Gerard ‘ cancellarius ’

were inserted. These changes are all the more striking in view of the

28 . For example in 1096, ‘ Count Henry went over to King William, whose loyal adherent he

became. The king then granted him the whole of the counties of the Cotentin and Bayeux, except

for the city of Bayeux and the town of Caen. ’ Gesta Normannorum Ducum VIII.7: ed. van Houts,

ii, 210 – 13. Henry did not, however, witness many of Rufus’s acta . H.W.C. Davis, ed., Regesta

Regum Anglo-Normannorum 1066 – 1154. Three Volumes. Volume i. Regesta Willelmi Conquestoris et

Willelmi Rufi , 1066 – 1100 (Oxford, 1913).

29 . Engels, De obitu Willelmi ducis , 253 – 4; Sapir and Speet, Kritische , 31; Gesta Normannorum

Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, lxiv – lxv.

30 . Engels, De obitu Willelmi ducis , especially at 234.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1426

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

otherwise close parallelism of the texts. Orderic by contrast, writing in

Henry I’s reign, included Henry, and omitted both these offi cials. Both

Engels and Sapir and Speet have noted these differences; Sapir and

Speet also gave a summary of the careers of two people who may

correspond to John and Gerard.

The inclusion of these two men, John and Gerard, in such a restricted

description as De obitu Willelmi , is certainly curious and requires some

explanation. Turning to John fi rst, it is not surprising that a doctor is

mentioned at the deathbed, since there were certainly medical

practitioners in Normandy and England at this time. What is signifi cant

is that a John is named, since as will be demonstrated below he is not

identifi able in any other sources relating to the Conqueror.

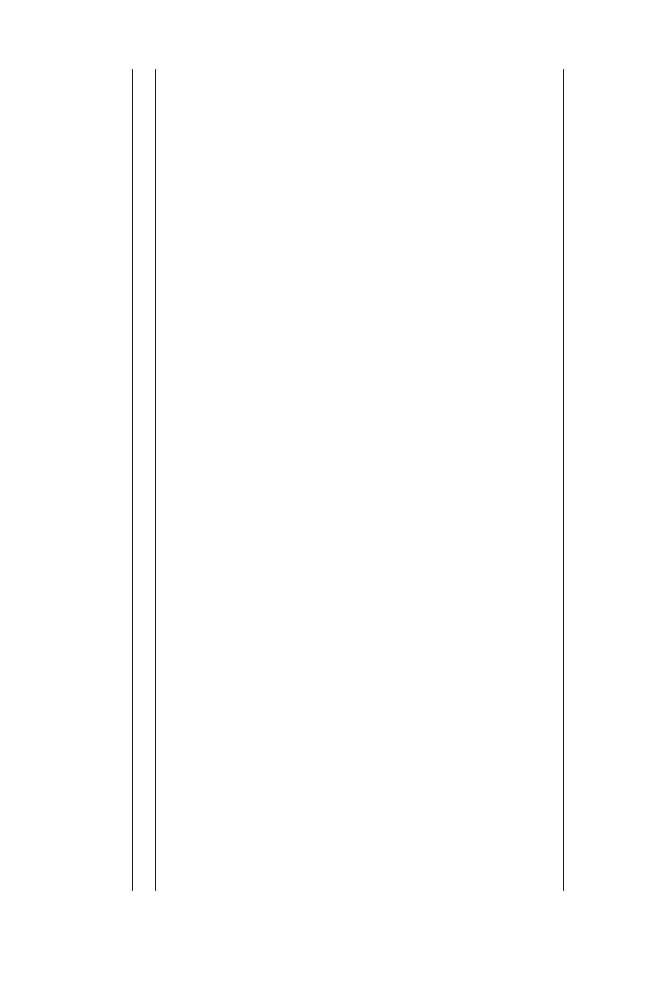

Table 1 summarises the key information about the nine doctors

associated with the Conqueror in non-narrative sources. Pre-eminent

among the royal doctors in Normandy was Gilbert Maminot, bishop of

Lisieux. A royal chaplain, he was consecrated bishop in 1077. On at

least one occasion, he was with the king in England, witnessing a charter

at Windsor in 1070.

31

Despite the dispute between his monastery and

the bishop, Orderic several times praised Gilbert’s medical abilities,

describing him as ‘ the king’s physician and chaplain … A man of great

learning and eloquence … ’

32

Gilbert also held land in England at

Domesday, in sixteen counties and from several previous holders,

perhaps indicating multiple small gifts from the king. Some of these

holdings may have related to his years as a royal chaplain, for example

his three virgates of the royal demesne at Windsor, where Albert the

Clerk and Eudo the steward also held.

33

While much smaller than the

English estates of Odo of Bayeux or Geoffrey of Coutances, Gilbert’s

total estate (valued at nearly £130) was still signifi cant.

34

Gilbert’s

presence at the deathbed is thus readily explained, especially since the

king was near Rouen, only about 80 km from Lisieux. De obitu Willelmi ,

however, does not mention that he was a doctor, reserving that title for

John. Orderic, while not actually calling Gilbert a ‘ medicus ’ in this

context (perhaps in deference to his episcopal rank), named him as

one of several senior clergy who watched over the king’s ‘ spiritual and

corporal needs ’ .

35

In this company, John’s inclusion in De obitu Willelmi as the only

named doctor is noteworthy. De obitu Willelmi is the only source to

31 . B. 81: D. Bates, ed., Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum. The Acta of William I (1066 – 1087)

(Oxford, 1998), 343 – 5.

32 . Oderic Vitalis V.3: ed. Chibnall, iii, 18 – 23.

33 . D[omesday] B[ook] Berks. i.56d.

34 . Odo’s personal holding exceeded £3,000, Geoffrey of Coutances held land valued at just

over £750, while the next largest estate of a Norman bishop was that of Gilbert, Bishop of Evreux,

valued at only £22. DB passim.

35 . Oderic Vitalis VII.14: ed. Chibnall, iv, 80 – 1. Chibnall translates ‘ archiater ’ as ‘ physician ’

here.

1427

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

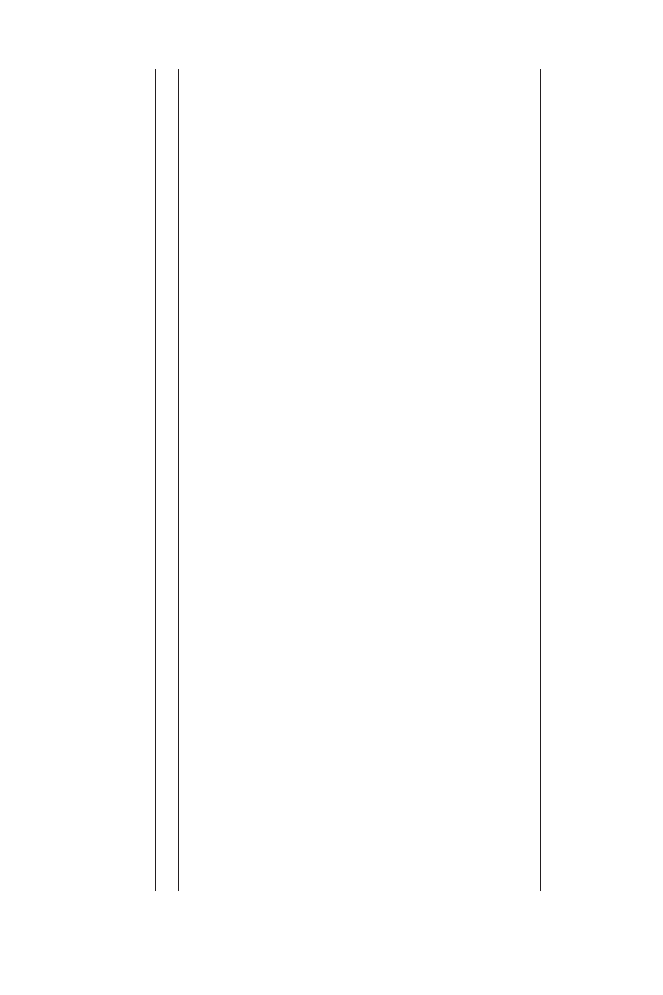

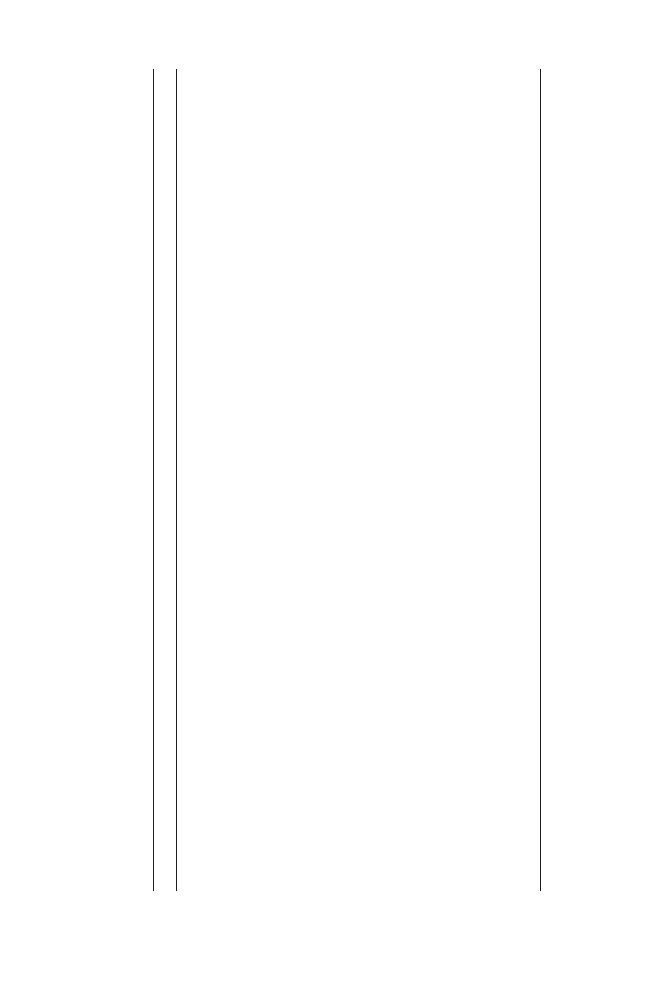

Table

1:

The doctors associated with William the Conqueror. Diplomatic and Domesday evidence

Name

No. of charters TRE

(with dates)

No. of William the Conqueror

acta

(with dating range)

Land held TRE

Land held

1086

a

Preferment?

Baldwin

b

1 (

1062

)

13

(

1066

–

1086

)£

11

£

16

.3

s.

Abbot of Bury St Edmunds,

1064

Gilbert

—

27

(

1042

×

1084

)

—

£

128

.5

s.

Bishop of Lisieux,

1077

Nigel

c

—

3 (

1035

×

1066

)

—

£

41

.6

s.

—

Gontard

d

—

5 (

1066

×

1078

–

c.

1087

) —

4 churches

Abbot of Jumièges,

1078

Robert

e

—

1 (

1081

×

1086

)

—

—

—

Rodolfus

f

—

1 (

1063

×

1066

)

—

—

—

Aelfric

—

—

—

4

acres

—

Tetbald

—

—

—

c.

£

1

—

John

—

—

—

—

Bishop

of

Wells,

1088

a

Some parcels of land are not valued in Domesday, so the fi

gures in the table are approximations only.

b

Baldwin witnessed a grant by Edward the Confessor in favour of Waltham Abbey in

1062

: Keynes (

Regenbald

). His personal landholdings are complex because he held land of

King Edward before becoming abbot, and this had been transferred to St Denis: B.

254

Bates (

Regesta

),

pp.

767

–

9. Moreover it is not always clear if land granted by William the

Conqueror was to Baldwin in person or to him in his capacity as Abbot.

c

The connection between the Domesday

‘ Nigel medicus

’ and the Nigel who witnessed F.

95

, F.

166

and F.

227

is not certain. Fauroux (

Recueil

),

pp.

247

–

8,

357

–

8,

435

–

7.

d

These

churches,

one

of

which

was

valued

at

28

s.

at Domesday, were transferred to St Wandrille when Gontard entered the abbey as a monk between

1066

and

1078

. B.

263

: Bates

( Regesta

),

p.

792

.

e

Named

as

a

subtenant

in

B.

49

: Bates (

Regesta

),

p.

235

.

f

Witnessed

F.

165

: Fauroux (

Recueil

),

p.

357

.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1428

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

mention a John ‘ medicus ’ before the death of the Conqueror, and as

Table 1 demonstrates, no doctor of this name held land at Domesday.

While this does not rule out the possibility that he acted as a royal

doctor, it suggests that he had not yet risen high in the king’s favour. As

already observed, there is no place for a named physician in the Vita

Hludouuici , so the inference must be that this is a calculated decision to

draw attention to him. Leaving aside the possibility that he was in some

way being blamed for the king’s death, or at least being held responsible

(neither of which are likely in this documentary context), this suggests

that he is mentioned in order to involve him in the events in some other

way, or to heighten his reputation.

If he was not offi cially a court ‘ medicus ’ , is there evidence for another

John associated with the Conqueror who might fi t this role? John was

not an unusual name at this period,

36

but there is no surviving evidence

for a chaplain named John among all those who witnessed charters, or

were named in them, during the lifetime of the Conqueror ( Table 2 ).

This material represents a minimum of twenty-two chaplains, but since

few of the individuals have identifying second names, the actual total

could be much greater, up to fi fty-six. In the two cases that do survive

of a ‘ John ’ witnessing a charter, the men concerned were both attached

to the recipient houses.

37

There is additionally one anomalous attestation

‘ Johannis Bathonensis episcopi ’ in a Durham charter in a hand from the

later twelfth century, purporting to date to about 1086; but since this

John was not consecrated until 1088 and only moved the see from Wells

to Bath c. 1091, this must represent a later accretion.

38

The possibility

does remain, however, that in its original form (if it had one) the charter

was witnessed by this John as a chaplain, and his title was later changed

anachronistically.

39

Thirteen names of chaplains occur as Domesday landholders, often

of modest amounts, but John is not among these either. For example,

36 . For example, Bishop John of Avranches (1060 – 7) went on to become Archbishop of Rouen

(1067 – 79), and Fécamp was ruled by an Abbot John from 1028 to 1079.

37 . ‘ Johannes monachus noster ’ in a dispute between Marmoutiers and St Pierre de la Couture:

F. 159 (1063 × 1066), in M. Fauroux, ed., Recueil des actes des ducs de Normandie de 911 a 1066 (Caen,

1961), 344 – 8; ‘ Ex parte sancte Trinitatis … Johannes ’ for La Trinité Fécamp: B. 147 (1066 × 1087),

Bates ( Regesta ), 489. The latter appears to have been identifi ed by Mooers as an attestation by the

John who became bishop of Bath and Wells, and furthermore to have been used as evidence that

this John was a royal chaplain from 1066 to 1087, but there seems to be no justifi cation for these

assumptions. S. Mooers Christelow, ‘ Chancellors and Curial Bishops: Ecclesiastical Promotions

and Power in Anglo-Norman England ’ , Anglo-Norman Studies , xxii (2000), 49 – 69, especially at 57.

38 . B. 115: Bates ( Regesta ), 407 – 8. John made his profession of obedience to Canterbury in July

1088 and was consecrated in the same month. F.M.R. Ramsey, ed., English Episcopal Acta x: Bath

and Wells, 1061 – 1205 (Oxford, 1995). The grant of Bath Abbey to John, enabling him to move the

see from Wells, was confi rmed in January 1091: W. Hunt, ed., ‘ Two Chartularies of the Priory of

St Peter at Bath’, Somerset Record Society , vii (1893), especially at 40 – 2.

39 . Compare, for example, B. 232 (1069), where Herfast is described in a late eleventh-century

cartulary copy of a charter as ‘ Erfast tunc capellani, postea episcopi ’ . Bates, Regesta , 725.

1429

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

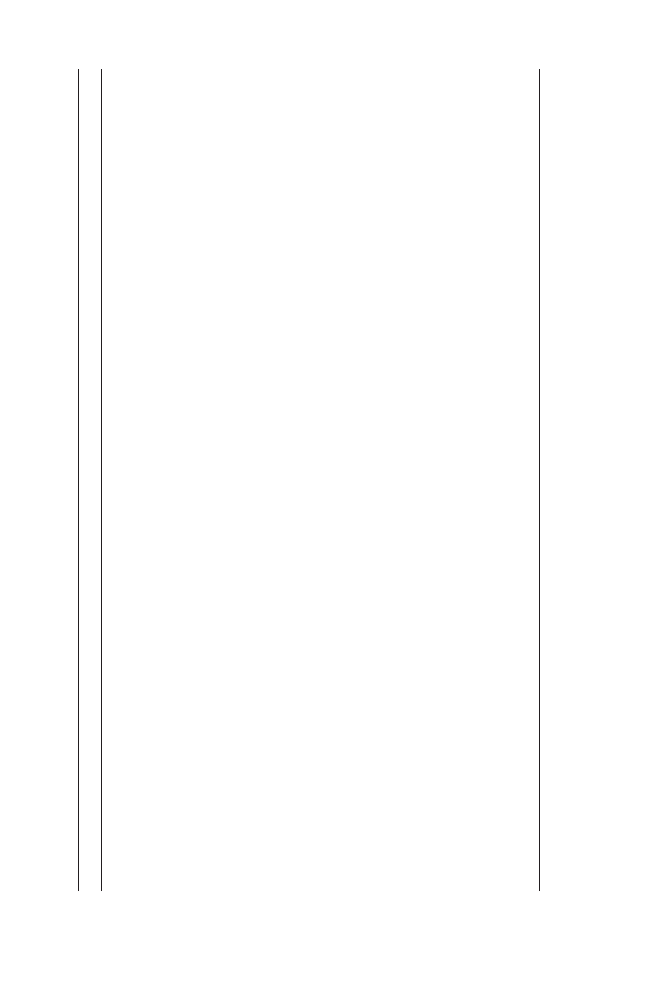

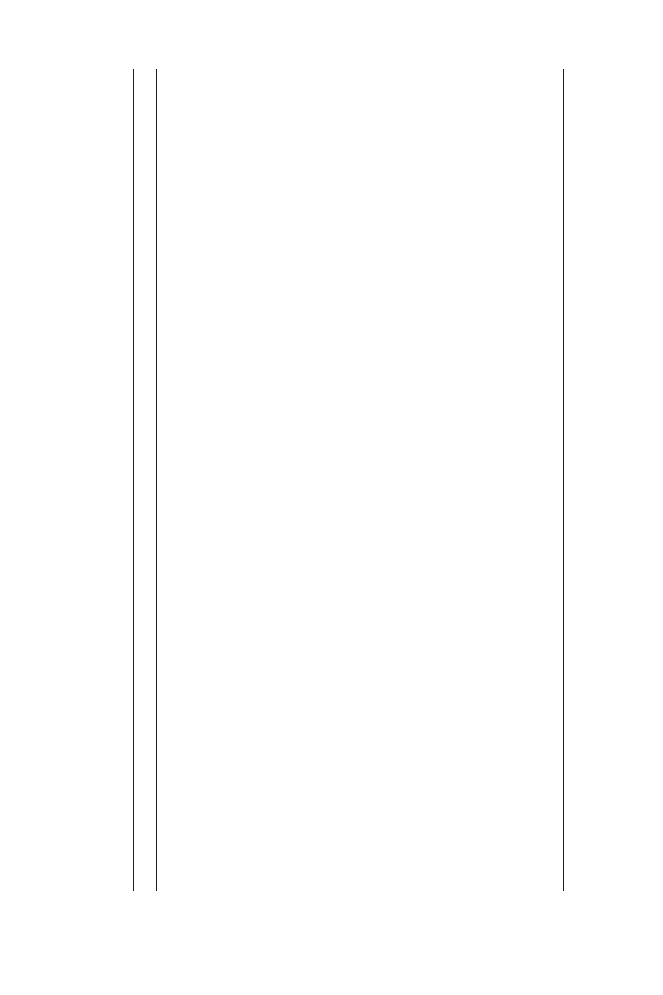

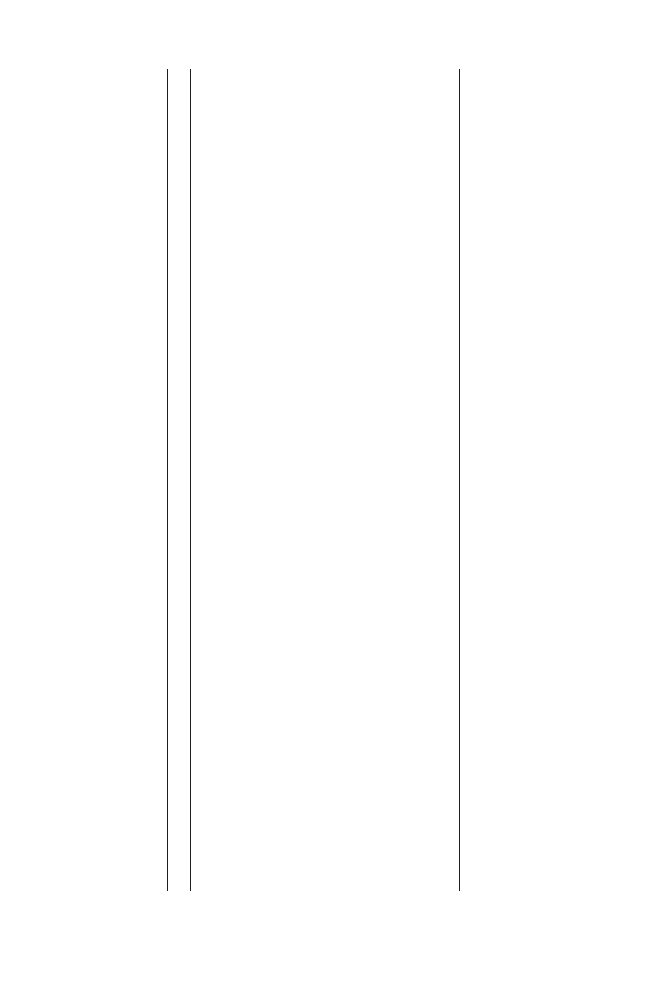

Table 2: Acta of William the Conqueror in which chaplains are named

a

Name

b

No.

of acta

Date range (with acta at

dating extremes)

Rainald

12

1050 × 1066 (F. 197) – 1080 ×

1084 (B. 162)

Samson

9

1072 × 1085 (B. 265) – 1083

(B. 64)

Odo (Queen’s chaplain)

5

1078 × 1083 (B. 160) – 1083

(B. 64)

Robert

c

5

1035 × 1065 (F. 164) – 1086

(B. 115)

d

Ingelric

4

1066 × 1067 (B. 216) – 1069

(B. 138)

Bernard

2

1068 (B. 181) – 1081 (B. 39)

Henry (Queen’s chaplain)

2

1079 × 1087 (B. 164) – 1080 ×

1083 (B. 161)

Theobald

2

1052 × 1058 (F. 141) – 1055

(F. 137)

Thomas

2

1068 (B. 181) – 1080 × 1084

(B. 162)

Baldwin

1

1052 × 1058 (F. 141)

Gerard

1

1073 × 1077 (B. 173a)

e

Goisfrid

1

1083 (B. 64)

Gontard

f

1

1066 × 1078 (B. 263)

Herfast

1

1069 (B. 232)

Maurice

g

1

1086 (B. 115)

Michael

1

1068 (B. 181)

Osmund

h

1

1074 (B. 27)

Ralf

i

1

1040 × 1050 (F. 117)

Ranulf

1

1086 (B. 115)

Seufredus

1

1042 × 1066 (F. 187)

Walter

1

1086 (B. 181)

William

1

1068 (B. 181)

a

Information drawn from Bates ( Regesta ) and Fauroux ( Recueil ).

b

Multiple entries may refer to more than one individual, of the same name. This table therefore

refers to a minimum of 22 chaplains, and a theoretical maximum of 56.

c

There were at least three royal chaplains called Robert: Robert Losinga became bishop of

Hereford in 1079, Robert de Limesey became bishop of Chester in 1086, Robert Bloet was

appointed to Lincoln by Rufus in 1094, after serving as chancellor.

d

Bates is undecided if B. 115 is genuine. See discussion in Bates ( Regesta ), p. 407.

e

Witnessed as chaplain with Robert Curthose; the same charter was witnessed by Osmund as

chancellor with the Conqueror.

f

The same Gontard who became abbot of Jumièges in 1078.

g

Probably the same Maurice who appears in eight acta as chancellor (1078 – 82).

h

Probably the same Osmund who appears in fi ve acta as chancellor (1067 – 78).

i

There are a further fi ve occurrences of ‘ Ralf ’ with no title ‘ chaplain ’ or ‘ priest’, between

1035 × 1066 (F. 166) and 1070 × 1083 (B. 206).

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1430

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

Samson, who is probably the man who became bishop of Worcester in

1096, held land valued at £11 3 s. and appears in nine royal charters, one of

which concerns the donation of land to him.

40

This practice of giving

small grants of land to royal chaplains was a well-established tradition:

several of Edward the Confessor’s chaplains held land in 1066, and some

of them were still landholders in 1086.

41

Chaplains such as Seufredus, who

witness early ducal charters, are not recorded in Domesday and perhaps

had already died, but many of the chaplains appointed to bishoprics by

the Conqueror had personal holdings, perhaps as a reward for their earlier

services.

42

(Bishop Peter of Chester, who died before 1086, even has two

references preserved to previous small landholdings of his.

43

)

There are also numerous lay royal servants who witnessed charters or

appear in Domesday. (Wiltshire Domesday alone lists twenty-nine such

men, including a cook, a doctor and three chamberlains, with an average

holding of £3.4 s. ) Three of these servants were called John, but none

seem likely to have been an important royal doctor: one (with no job

listed) held land to the value of 40s.; John ‘ hostillarius ’ held land in two

counties to the value of £6.5 s. ; and John ‘ camerarius ’ held land valued at

35s. which the queen had given him.

44

By contrast, once Rufus came to the throne, the evidence proliferates

for a royal doctor named John. A priest of the city of Tours, he was

appointed bishop of Wells in summer 1088, with a speed uncharacteristic

of Rufus’s usual treatment of episcopal vacancies. In near-contemporary

sources, this John is always referred to as Turonicus , but, perhaps as a result

of a misreading of Wellensis , he is referred to in Anglia Sacra and thereafter

as John de Villula.

45

Ranulf Flambard is often cited as an example of a

man who rose swiftly by lay employment at Rufus’s court, to become a

bishop. But he already held land at Domesday, valued at over £20, and he

was not consecrated until 1099, after a decade of curial service. Compared

with him, John’s rise from obscurity to the episcopacy was meteoric.

40 . B. 265: Bates, Regesta , 796.

41 . For example, Edward the Confessor’s two chaplains Ingelric, who held land valued at over

£300 at one stage and at Domesday still held property valued at £24, and Regenbald, whose land

at Domesday was valued at about £40, spread over fi ve counties. S. Keynes, ‘ Regenbald the

Chancellor (sic), ’ Anglo-Norman Studies , x (1988), 185 – 222.

42 . For example, Bishop Walkelin of Winchester held a hide of land valued at £4 at Brownwich,

and ‘ it is not of the bishopric ’ : DB Hants. i.40d; Bishop Osbern of Exeter held lands attached to

Bosham church, to a value of £60.15 s. in 1086, and had held them from Edward the Confessor: DB

Sussex i.17b.

43 . Two churches and about two hides of land in Somerset, valued at £3, DB Somerset i.91c;

and a close in the borough of Wallingford rendering 4d., DB Berks. i.56b.

44 . Wimbourne, DB Dorset i.85a; DB Wilts. i.74c and DB Somerset i.87c, i.90c; DB Glos.

i.163d. Compare this last holding with that of ‘ William camerarius ‘ : nearly £60 in eight counties,

including a vineyard in Holborn.

45 . Wharton’s Anglia Sacra I: ‘ The Canon of Wells, ’ 559. D. Greenway, John le Neve; Fasti

Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066 – 1300. VII. Bath and Wells (London, 2001), 1. See, for example B. 68, an

original charter dated 1072 (Bates, Regesta , 311 – 14) which Giso, John’s predecessor at Wells, attested

as Giso UUellensis.

1431

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

Orderic implied, but did not state categorically, that this ‘ John the

doctor ’ acted as a chaplain to Rufus; he lumped him together with those

‘ chaplains and favourites ’ who obtained bishoprics from him, to whom

he ‘ bestowed ecclesiastical honours, like hireling’s wages, on clerks and

monks of the court, looking less for piety in these men than for

obsequiousness and willing service in secular affairs’.

46

Smith, in his

study of John’s career, suggested that Rufus was already using him as a

chaplain before he became king, although there is no evidence that

Rufus had an independent household before 1087.

47

If John’s service

only began then, there was not much time for him to make such an

impression on the young king as would justify his preferment the

following year.

The other chroniclers were clear that the John who became bishop of

Bath and Wells was a doctor, and they were not always complimentary

about his abilities. ‘ John, who originated from Tours, succeeded Giso as

bishop of Wells. He practised as a doctor, though he had not been

trained as one. ’

48

‘ A native of Tours and by practice rather than by book-

learning a skilled physician. ’

49

Thus there is an anomalous situation for the fi rst of the two royal

servants named in De obitu Willelmi . John ‘ medicus ’ not only had no

place in the model used but also had no discernable place in the royal

household prior to 1087. Once Rufus became king, however, a man

who could be this John emerged swiftly into an important role, more

suited to that accorded him in De obitu Willelmi . The possibility of a

causal link between these facts will be discussed later.

Turning now to the second royal servant in De obitu Willelmi , a

chancellor is as plausible an attendant near a royal deathbed as a doctor.

Keynes has shown that from at least Edward, the Confessor’s reign there

was an embryonic chancery in England. A succession of Normans acted

as chancellor, probably beginning with Herfast in about 1068. The

fl uidity of the role and title may be indicated by the presence of a witness

‘ Herfastus capellanus ’ on a charter in 1069.

50

Herfast seems to have been

replaced, in turn, by Osmund and Maurice, as each was elevated to the

episcopate. In each case, surviving royal charters are also witnessed by

chaplains of these names during their ‘ term of offi ce ’ as chancellor.

51

Maurice was consecrated bishop of London in 1086. Davis suggested

that he was succeeded as chancellor by Robert Bloet, but in 1931

46 . Oderic Vitalis , X.2: ed. Chibnall, v, 204 – 5 and 202 – 3.

47 . R.A.L. Smith, Collected Papers (London, 1947), 75.

48 . John of Worcester, entry for 1091: P. McGurk, ed., The Chronicle of John of Worcester. Three

Volumes. Volume iii: The Annals from 1067 to 1140 … (Oxford, 1998), iii, 57.

49 . Gesta Regum Anglorum IV.340: eds. Mynors et al. , 588 – 9.

50 . B. 181, see also B. 138 and 81; for Herfast as capellanus in 1069 (probably April) see B. 232.

Bates, Regesta , 594 – 601, 463 – 5, 343 – 5, 725.

51 . Osmund: see B. 27; Maurice: see B. 110 (a Durham forgery) and B. 115 (possibly genuine).

Bates, Regesta , 176 – 8, 394 – 7, 406 – 8.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1432

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

Galbraith proposed that Gerard, or Girard, afterwards bishop of

Hereford, was briefl y chancellor in between.

52

This was based partly on

the evidence of Hugh the Chantor of York, and partly on two writs,

both attested by ‘ G.cancellario ’ , the fi rst of which Galbraith dated to

late in the Conqueror’s reign or soon after, the second to early in the

reign of Rufus. Bates has since concluded that neither can be dated

more closely than 1086×1088,

53

but it is nevertheless probable that

Gerard served, albeit briefl y, in the chancery at the end of the Conqueror’s

reign. A chaplain named Gerard appears in the witness list of one of the

acta of the Conqueror’s reign (see Table 2 ), and Eadmer described

Gerard not as Rufus’s chancellor but as a

‘

chaplain of the king,

’

complying with his wishes in his dispute with Anselm.

54

A ‘ Gerald the

chaplain ’ held three pieces of land valued together at Domesday at

£3 10 s.

55

As with John ‘ medicus ’ , the Vita Hludouuici model does not justify

the inclusion of Gerard ‘ cancellarius ’ in De obitu Willelmi . Unlike John,

however, there is evidence that a man of this name witnessed royal

charters prior to 1088 and held land at Domesday, and he may have

been chancellor briefl y. While there is no certainty that all this evidence

relates to one and the same person, there is at least a body of evidence

that such a man existed. Unlike John, Gerard continued to act as a royal

chaplain for Rufus, only obtaining a bishopric in 1096. Neither of these

men seems to have held a prominent enough position at court in 1087

to warrant their mention in De obitu Willelmi unless there were some

particular motive for doing so. Of the two, John’s inclusion is by far the

more curious. The question therefore arises whether either of them was

linked in some specifi c way to Rufus around the time of his accession,

or even to the production of De obitu Willelmi , as van Houts has

proposed.

Superfi cially, De obitu Willelmi is not greatly concerned with the

English succession. The part of the Vita Hludouuici model dealing with

the royal succession is shortened, leaving only the non-committal

statement ‘ he allowed his son William to have the crown, the sword and

the golden sceptre with inlaid jewels’. In contrast, extra phrases are

added to emphasise the Conqueror’s fears for Normandy if Curthose

should become duke. When these facts are combined with the probable

dating of

De obitu Willelmi

to Rufus’s reign, and the surviving

manuscripts being in England, a logical inference is that it sees his

accession as an accomplished fact.

52 . Davis, Regesta , xvi – xxi; V.H. Galbraith, ‘ Girard the Chancellor ’ , ante , xlvi (1931), 77 – 9.

53 . C. Johnson, ed., Hugh the Chantor: The History of the Church of York, 1066 – 1127 (London,

1961), 11; B. 278 and B. 352: Bates, Regesta , 835 – 6 and 1003 – 4.

54 . Historia Novorum II.68: G. Bosanquet, tr., Eadmer’s History of Recent Events in England.

Historia Novorum in Anglia (London, 1964), 71.

55 . DB Devon i.117a.

1433

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

Close analysis of the other sources for the 1087 succession reveals,

however, some ambiguity. Symeon of Durham and William of

Malmesbury both hint at a need for speed: ‘ he gave the kingdom of

England to his son William … [who] hurried off to England … ( festinato

adiit ), ’

56

‘ William, before his father had fi nally expired, had sailed away

to England (

antequam plane pater expiraret Angliam enauigauerat )

thinking it more to the purpose to secure his own future interests than

to attend the burial of his father’s body. To this end, he was neither

dilatory nor sparing in the distribution of funds. ’

57

Orderic as usual

paints a fuller picture:

58

… the king, fearing that rebellion might suddenly break out in a realm as

far-fl ung as his, had a letter to secure the recognition of the new king

addressed to Archbishop Lanfranc and sealed with his seal. Giving it to his

son William Rufus, he ordered him to cross to England without delay. Then

he gave him his blessing with a kiss, and sent him post-haste ( properanter

direxit ) overseas to receive the crown.

There are also two curious small passages in William of Malmesbury:

Robert ‘ forfeiting both his father’s blessing and his inheritance, failed to

secure England’, and of Rufus, ‘ his hopes gradually rose and he began

to covet the succession’.

59

Orderic also reported King Malcolm of

Scotland in 1091 as saying ‘ I owe you nothing, King William [Rufus] …

but if I could see King William’s eldest son, Robert, I would be ready to

offer him whatever I owe ’ and to Curthose himself Malcolm said, ‘ King

William required my fealty to you as his fi rst-born son ’ , To which Robert

replied, ‘ what you allege is true. But conditions have changed and my

father’s decrees have been undermined in many ways. ’

60

Robert of Torigni seems to go further:

61

let me give you an account of his death, as some say it happened … [he]

granted the kingdom of England to his son William … [who crossed] to

England as swiftly as possible, where he was accepted … When urged to

reconquer by force the kingdom of England, taken away from him by his

brother, Robert is said to have answered with his usual simplicity and, if I

may put it so, almost as a fool: ‘ By the angels of God, if I were in Alexandria,

the English would have waited for me and they would never have dared to

make him king before my arrival. Even my brother William, whom you say

has dared to aspire to the kingship, would never risk his head without waiting

for my permission. ’

56 . Symeon of Durham, Historia Regum 169: T. Arnold, ed., Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia.

II. II Historia Regem … (London, Rolls Series, lxxv, 1885), 214.

57 . Gesta Regum Anglorum III.283: eds. Mynors et al. , 512 – 13.

58 . Oderic Vitalis VII.16: ed. Chibnall, iv, 96 – 7.

59 . Gesta Regum Anglorum III.274 and IV.305: eds. Mynors et al. , 502 – 3, 542 – 3.

60 . Oderic Vitalis VIII.22: ed. Chibnall, iv, 268 – 71.

61 . Gesta Normannorum Ducum VII.44 and VIII.2: ed. van Houts, ii, 192 – 5 and 202 – 5.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1434

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

The most overt remarks are in Eadmer’s Historia Novorum . He chose to

begin his book by comparing the blessings of the reign of Edgar with

that of ‘ Ethelred, because he had grasped the throne by the shedding of

his brother’s blood … monstrous wrongs were done which every year

increased and grew worse and worse’. Then when describing the

succession in 1087:

62

[Rufus], intent on seizing the prize of the kingdom before his brother

Robert, found Lanfranc, without whose support he could not possibly attain

the throne, not altogether favourable to the fulfi llment of this his desire.

Accordingly, fearing that any delay in his consecration might result in the

loss of the dignity which he coveted, he began, both personally and indirectly

by all whom he could get to support him, to make promises to Lanfranc

…

These and other passages suggest that the succession of Rufus to England

in 1087 was not an entirely clear-cut matter. Can De obitu Willelmi shed

any light on this situation?

Previous research on De obitu Willelmi has paid great attention to the

donation of the regalia, pointing to a 1096 × 1098 charter in favour of St

Etienne Caen which exchanges them for property in England.

63

English

concluded that the Conqueror ‘ made no declaration about the succession

to England. The regalia … may have been those of the king of England

who was also duke of Normandy, to remain at Caen until a new king-

duke could legitimately claim them. ’

64

Sapir and Speet noted that De

obitu Willelmi might be mentioning the regalia in a metaphorical sense,

to indicate that Rufus was heir to the kingdom. But they favoured using

this passage to propose a date for De obitu Willelmi ‘ s composition in

1096 – 7, associated with the construction of the Conqueror’s tomb and

the handover of Normandy from Curthose to Rufus on the eve of the

crusade.

65

They observed that the Caen charter, like De obitu Willelmi ,

describes the Conqueror’s death; it is also witnessed by Bishop John of

62 . HN 3, 5 and 25: tr. Bosanquet, 3 – 5 and 26; M. Rule, ed., Eadmeri Historia Novorum in

Anglia, et opuscula duo de Vita Sancti Anselmi et quibusdam miraculis ejus (London, Rolls Series,

lxxxi, 1884), 25. This compares interestingly with his statement in the Vita Anselmi: ‘ When the

renowned William King of the English died, his son William inherited [ obtinuit ] the throne. ’

R.W. Southern, ed., Eadmer: The Life of St Anselm Archbishop of Canterbury. Eadmeri monachi

Cantuariensis . Vita Sancti Anselmi, archiepiscopi Cantuariensis (London, 1962), 63. The other

Canterbury source, the Acta Lanfranci, says ‘ … Lanfranc chose his son William as king, even as

his father had desired … ’ ‘ … fi lium eius Willelmum, sicut pater constituit, Lanfrancus in regem

elegit … ’ J.M. Bately, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Collaborative Edition. Volume iii. Manuscript A

(Cambridge, 1986), 87. This is in Hand 13 of the A manuscript, which was written after 1093. See

also the discussion in English ( William the Conqueror and the … Succession ), at 229 – 32; and J.S.

Beckerman, ‘ Succession in Normandy, 1087, and in England, 1066: The role of Testamentary

Custom, ’ Speculum , xlvii (1972), 258 – 60.

63 . The charter is printed in full in Sapir and Speet ( Kritische ), 56 – 7. Davis, Regesta , no. 397.

64 . English ( William the Conqueror and the … Succession ), at 236.

65 . Sapir and Speet, Kritische , 30 – 2.

1435

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

Bath and Bishop Gerard of Hereford, who may be the John and Gerard

of De obitu Willelmi .

These apparent connections may, however, be coincidental. The

wording of the Caen charter concerning the regalia is very different

from that in De obitu Willelmi . Also, there are three other bishops and

ten laymen who witness the charter, besides John and Gerard, many of

them closely associated with Rufus’s rule in England. It is not clear

where the charter was attested, and there are suffi cient references in the

sources to both John and Gerard assisting Rufus in various ways for

their presence together as witnesses to be unremarkable. There is also a

more fundamental objection to linking the production of De obitu

Willelmi to this charter, namely that there is no obvious purpose that it

could have served in 1096 – 7. It was suggested by van Houts that Rufus

needed De obitu Willelmi to strengthen his claim to the regalia, and that

De obitu Willelmi was a ‘ piece of propaganda ’ written for that purpose;

she proposed Gerard as a possible author.

66

While De obitu Willelmi

does read like propaganda (but against Curthose, rather than in favour

of Rufus) it remains unclear who would have had reservations about the

release of this set of regalia to Rufus in 1096 – 7 and yet would have been

swayed by De obitu Willelmi . The possibility has to be considered

therefore that the question of the regalia has become a red herring,

hindering a fuller investigation of De obitu Willelmi ’ s signifi cance.

It is nevertheless apparent that the regalia are deliberately included in

De obitu Willelmi . The Vita Hludouuici model was modifi ed to stress

that Rufus was to be the recipient, not just that they are to be handed

into neutral care until the succession is decided,

67

and only after this

was the text cut. If Rufus’s succession, or the grant to him of some token

of royalty, were irrelevant, this sentence could have been omitted. So,

obliquely, De obitu Willelmi acknowledges Rufus as the next king by his

father’s consent, but this is not its main purpose.

There are fi ve features of the 1087 succession which merit particular

comment. First is Rufus’s hasty departure, even before his father had

died, at a time when there was no obvious external foe. The need for

speed is mentioned several times, and De obitu Willelmi does not actually

say he was present when his father died. This suggests a real fear, and

one obvious cause is lest a rival, presumably Curthose, beat him to the

throne. Orderic said that Rufus’s only companion on his journey was

Robert Bloet, who replaced Gerard as chancellor. It would have taken

two days to ride from Rouen to the port at Touques, longer if they

crossed from Wissant.

68

One can imagine them waiting with a boat

66 . Gesta Normannorum Ducum : ed. van Houts, i, lxiv – lxv.

67 . The imperial regalia were left with the widowed empress on several occasions from 1024

onwards, and Orderic Vitalis was aware of this convention. French kings sometimes left their

regalia to St Denis: M. Chibnall, The Empress Matilda. Queen Consort, Queen Mother and Lady of

the English (Oxford, 1991), 40 – 3.

68 . Oderic Vitalis VII.16 and X.2: ed. Chibnall, iv, 97 and v, 203.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1436

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

until they heard the king was dead, so as to minimise delay. Here, De

obitu Willelmi differs from the other accounts of the deathbed, by

implying that Rufus was present for the grant of the regalia. This seems

to be achieved deliberately, by the alteration of misit to permisit. This

may be a device to gloss over Rufus’s absence when the succession was

declared, or to stress that he was present at this critical time, only

departing subsequently. This lack of clarity is echoed in Stephen’s

accession; he was accused by the bishop of Angers, ‘ As for your statement

that the king changed his mind, it is proved false by those who were

present at the king’s death. Neither you nor Hugh could possibly know

his last requests, since neither was there. ’

69

Secondly, there is the absence of Curthose. He was heir to Normandy

and Maine, if no more. His father lay sick at Rouen for well over a

month, and if Curthose was indeed at Abbeville, as Robert of Torigni

says, he could have been at the bedside in a matter of days.

70

The

conventional wisdom is that by 1087 Curthose had been ‘ in rebellion ’

for several years, but a close examination of the contemporary sources

does not bear this out. On the contrary, this story can be shown to rely

on one passage in Orderic Vitalis, written when Curthose had already

been Henry I’s prisoner in England for many years, discredited and

disinherited. Orderic contradicts himself in another passage, saying that

Curthose had ‘ only recently ’ ( tunc nouiter ) left court, and the other

chroniclers are agreed that William the Conqueror was able to move a

large army to England in 1085 to counter the threatened Danish invasion,

and then he remained there himself until late summer 1086.

71

These

actions do not sit well with the idea of his son staging a major rebellion

at the time. It seems unlikely moreover that Curthose would have

imperilled his inheritance by deliberately staying away, and in the

absence of any description of a major rift with his father at this late

stage, except the contradictory comments of Orderic, the question arises

whether he might have been deliberately kept from knowing how ill his

father was.

Thirdly, Lanfranc was apparently unprepared for the king’s decision.

He was a close adviser and supporter of the Conqueror, yet Eadmer

stressed that Lanfranc had no idea that Rufus was the chosen heir.

Archbishop and king corresponded regularly, yet all the indications are

that no message was sent to Lanfranc between July and September 1087.

The only letter that is mentioned is the one Orderic said was carried by

69 . M. Chibnall, ed., John of Salisbury’s Memoirs of the Papal Court. Ioannis Saresberiensis

Historia Pontifi calis (London, 1956), 85; cited in W.C. Hollister, Henry I (New Haven and London,

2001), 479.

70 . Gesta Normannorum Ducum VIII.2: ed. van Houts, ii, 202 – 3.

71 . Oderic Vitalis VII.14 and V.10: ed. Chibnall, iv, 80 – 1 and iii, 112 – 13; ASC E for 1085 and

1086: D. Whitelock, D.C. Douglas and S.I. Tucker, eds., The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Revised

Translation (London, 1961), 161 – 2; K. Lack, Conqueror’s Son: Duke Robert Curthose, Thwarted King

(Stroud, 2007), 27 – 35.

1437

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

Rufus. This letter has not survived. Barlow observed that this letter only

occurs in the Norman tradition; ‘ neither the letter nor its tenor was

preserved at Canterbury. It would have been sensible for Lanfranc to fi le

this important mandate, but whoever collected and published his

correspondence omitted it, and Eadmer passes over it in silence. If

indeed such a letter ever existed … . ’

72

There was a two-week interval before Lanfranc crowned Rufus, during

which Eadmer claimed considerable pressure was applied. An additional

factor in Lanfranc’s deliberations may have been the knowledge that

both Harold and William the Conqueror had been crowned by the

archbishop of York, and in the delicate state of the primacy dispute,

Lanfranc would not want Rufus to apply to Archbishop Thomas.

Fourthly, one might expect some evidence that Rufus had been

publicly recognised as heir to the kingdom, or had at least supplanted

Curthose in his father’s charters. But there is no such evidence. The one

time when the Conqueror might have made some statement about the

succession, at Salisbury in 1086, it seems that he instead continued to

demand personal loyalty to himself alone.

73

No original charters place

Rufus before Curthose; two eighteenth-century copies of charters

apparently do so, but the latest two surviving acta have the normal

sequence of attestations. In the last two surviving acta he witnessed for

his father, Rufus was not even given the title comes , despite the fact that

one of them was witnessed in England.

74

Fifthly, there is the reaction of the magnates on both sides of the

Channel to Rufus’s succession. The story in the sources varies, and is

complicated by the hostility between Lanfranc and Odo, but the barons

moved quickly in support of the elder brother’s claim. The plot may

have been hatched in Normandy before Christmas; by Easter 1088 there

was a widespread uprising imminent in England. Interestingly, there

was no comparable rising against Curthose in Normandy. This rising

needs to be seen not merely in the context of the acknowledged status

of an anointed king and the oaths recently sworn to him,

75

but of what

the rebels stood to lose in practical terms. Although, as Strevett has

noted, Rufus was supported by many of the nobility based in England,

the three greatest lay landholders there and the Conqueror’s fi ve closest

supporters all rose for Curthose in 1088.

76

Odo had been imprisoned by

72 . F. Barlow, William Rufus (London, 1983), 55. Barlow points to a possible parallel with a letter

from Henry I to the pope, which Anselm omitted from his letter collection.

73 . ASC E for 1086: ed. Whitelock, 162.

74 . B. 205 (June 1082) and B. 279 (1083), B. 252 (January 1084) and B. 156 (probably Christmas

1085), B. 146 (April 1086 or later, ‘ fi lii regis Willelmus et Henricus ’ ) and B. 242 (late 1086 × 1087,

‘ fi lius regis ’ ): Bates, Regesta , 644 – 6, 837, 763, 513, 482 – 4, 741 – 2.

75 . M. Strickland, ‘ Against the Lord’s Anointed: Aspects of Warfare and Baronial Rebellion in

England and Normandy, 1075 – 1265 , in G. Garnett and J. Hudson, eds., Law and Government in

Medieval England. Essays in Honour of Sir James Holt (Cambridge, 1994), 56 – 79.

76 . N. Strevett, ‘ The Anglo-Norman Civil War of 1101 Reconsidered ’ , Anglo-Norman Studies ,

xxvi (2003), 159 – 75 at 160 – 1.

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

1438

THE DE OBITU WILLELMI

the Conqueror, but the other magnates who sided with Curthose are

never known to have wavered in their loyalty. Of the rebel leaders, only

Eustace of Boulogne had relatively little to lose, since his main lands

were on the continent.

Donald and Bennett have both suggested that this rising represented

the magnates asserting their rights as Normans, not bound by Anglo-

Saxon conventions, pushing for a unitary succession and their own

newly achieved power as kingmakers, rather than personal loyalty to

Curthose.

77

An echo of this may survive in the speech that Orderic gave

to them:

78

If we serve Robert duke of Normandy as we ought we will offend his brother

William … Again, if we obey King William dutifully, Duke Robert will

confi scate our inherited estates in Normandy … since King William is the

younger of the two and very obstinate and we are under no obligation to

him he must be deposed or slain. Then let us make Duke Robert ruler over

England and Normandy to preserve the union of the two realms, for he is

older by birth and of a more tractable nature, and we have already sworn

fealty to him during the lifetime of the father of both men.

Whatever the underlying complexities, the 1087 succession certainly

occurred within a framework of varying expectations, and at a time of

transition. It conformed to Norman tradition for Normandy, but does

not seem to have followed English practices very closely, apparently

relying on designation, with a minimum of election and a move towards

‘ pre-emptive anointing’.

79

A few surviving hints in the sources, and

particularly the events of 1088, indicate that the succession of Rufus was

not the universally expected outcome, nor was it accepted without

contention.

Modern historiography has not always found the partition of 1087

comfortable either. Barlow and Le Patourel have stressed the inevitability

of divided loyalties when the Anglo-Norman lands were split, and these

were diffi culties that the Conqueror must have foreseen.

80

Bates and

others have suggested that a man so apparently eager to retain power

might wish to pass on his ‘ empire ’ intact, thereby enhancing his own

posterity. It is also certain that England was the richer of the two realms:

would William willingly deprive Normandy of this newly acquired

source of wealth? ‘ There is in fact a lot to be said for the emergence of

77 . M. Donald, King Stephen (London, 2002), 44. M. Bennett, ‘ Poetry as History? The ‘ Roman

de Rou ’ of Wace as a Source for the Norman Conquest’, Anglo-Norman Studies , v (1983), 21 – 39,

at 36.

78 . Oderic Vitalis VIII.2: ed. Chibnall, iv, 122 – 5.

79 . G. Garnett, ‘ Coronation and Propaganda: Some Implications of the Norman Claim to the

Throne of England in 1066 ’ , Transactions of the Royal Historical Society , xxxvi (1986), 91 – 116 at 93

and 115 – 6.

80 . Barlow ( William Rufus ), 40 – 5; J. Le Patourel, Feudal Empires, Norman and Plantagenet

(London, 1984).

1439

EHR, cxxiii. 505 (Dec. 2008)

PROPAGANDA FOR THE ANGLO-NORMAN SUCCESSION

an awareness among the Anglo-Norman aristocracy and ruling family

of the importance of keeping Normandy and England united. ’

81

Strevett

has more recently argued that ‘ substantial sections of the aristocracy

clearly doubted whether the decision taken to divide Normandy and

England in 1087 was either legally correct or politically viable

’

,

82

although as Holt has noted, the term ‘ law ’ is scarcely applicable to this

period, except as an ‘ assemblage of customs and conventional practices

which were still malleable ’ .

83

The possibility that De obitu Willelmi could be part of the process of

promoting Rufus at the expense of Curthose’s more obvious claims to