A Byte of Python

Swaroop C H

27 May 2013

Contents

8

1.1 Who Reads A Byte of Python? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

1.2 Academic Courses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.3 License . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.4 Read Now . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.5 Buy the Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.6 Download . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

1.7 Read the book in your native language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

13

2.1 Who This Book Is For . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2.2 History Lesson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

2.3 Status Of The Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

2.4 Official Website . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

2.5 Something To Think About . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

15

3.1 Features of Python . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.1.1 Simple . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.1.2 Easy to Learn . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.1.3 Free and Open Source . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3.1.4 High-level Language . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1

3.1.5 Portable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.1.6 Interpreted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.1.7 Object Oriented . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.1.8 Extensible . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.1.9 Embeddable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.1.10 Extensive Libraries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.2 Python 2 versus 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.3 What Programmers Say . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

18

4.1 Installation on Windows . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4.1.1 DOS Prompt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4.1.2 Running Python prompt on Windows . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4.2 Installation on Mac OS X . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

4.3 Installation on Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

4.4 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

21

5.1 Using The Interpreter Prompt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

5.2 Choosing An Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

5.3 Using A Source File . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

5.3.1 Executable Python Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

5.4 Getting Help . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

5.5 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

27

6.1 Comments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

6.2 Literal Constants . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

6.3 Numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

6.4 Strings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

6.4.1 Single Quote . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

6.4.2 Double Quotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

2

6.4.3 Triple Quotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

6.4.4 Strings Are Immutable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

6.4.5 The format method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

6.5 Variable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

6.6 Identifier Naming . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

6.7 Data Types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

6.8 Object . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

6.9 How to write Python programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

6.10 Example: Using Variables And Literal Constants . . . . . . . . . 32

6.10.1 Logical And Physical Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

6.10.2 Indentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

6.11 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

35

7.1 Operators . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

7.1.1 Shortcut for math operation and assignment . . . . . . . 38

7.2 Evaluation Order . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

7.3 Changing the Order Of Evaluation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

7.4 Associativity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

7.5 Expressions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

7.6 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

41

8.1 The if statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

8.2 The while Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

8.3 The for loop . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

8.4 The break Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

8.4.1 Swaroop’s Poetic Python . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

8.5 The continue Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

8.6 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

3

48

9.1 Function Parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

9.2 Local Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50

9.3 Using The global Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

9.4 Default Argument Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

9.5 Keyword Arguments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53

9.6 VarArgs parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

9.7 Keyword-only Parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

9.8 The return Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55

9.9 DocStrings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56

9.10 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

58

10.1 Byte-compiled .pyc files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

10.2 The from . . . import statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

10.3 A module’s name . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

10.4 Making Your Own Modules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61

10.5 The dir function . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62

10.6 Packages . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

10.7 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64

65

11.1 List . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65

11.1.1 Quick Introduction To Objects And Classes . . . . . . . . 65

11.2 Tuple . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

11.3 Dictionary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69

11.4 Sequence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70

11.5 Set . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

11.6 References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73

11.7 More About Strings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

11.8 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

4

76

12.1 The Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76

12.2 The Solution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77

12.3 Second Version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79

12.4 Third Version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80

12.5 Fourth Version . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

12.6 More Refinements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

12.7 The Software Development Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

12.8 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

13 Object Oriented Programming

85

13.1 The self . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

13.2 Classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86

13.3 Object Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

13.4 The init method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

13.5 Class And Object Variables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

13.6 Inheritance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

13.7 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

94

14.1 Input from user . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

14.2 Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

14.3 Pickle . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

14.4 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

99

15.1 Errors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

15.2 Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

15.3 Handling Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

15.4 Raising Exceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

15.5 Try .. Finally . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

15.6 The with statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

15.7 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

5

104

16.1 sys module . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

16.2 logging module . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

16.3 Module of the Week Series . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

16.4 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

107

17.1 Passing tuples around . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

17.2 Special Methods . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

17.3 Single Statement Blocks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

17.4 Lambda Forms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

17.5 List Comprehension . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

17.6 Receiving Tuples and Dictionaries in Functions . . . . . . . . . . 110

17.7 The assert statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

17.8 Escape Sequences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

17.8.1 Raw String . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

17.9 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

112

18.1 Example Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

18.2 Questions and Answers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.3 Tutorials . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.4 Videos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.5 Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.6 News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.7 Installing libraries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.8 Graphical Software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

18.8.1 Summary of GUI Tools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

18.9 Various Implementations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

18.10Functional Programming (for advanced readers) . . . . . . . . . . 116

18.11Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116

6

117

118

20.1 Birth of the Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

20.2 Teenage Years . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118

20.3 Now . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

20.4 About The Author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119

119

121

22.1 Arabic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121

22.2 Brazilian Portuguese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

22.3 Catalan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

22.4 Chinese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122

22.5 Chinese Traditional . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

22.6 French . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123

22.7 German . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

22.8 Greek . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

22.9 Indonesian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

22.10Italian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

22.11Japanese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

22.12Mongolian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

22.13Norwegian (bokmål) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

22.14Polish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

22.15Portuguese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

22.16Romanian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

22.17Russian and Ukranian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

22.18Slovak . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

22.19Spanish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

22.20Swedish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

22.21Turkish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129

7

129

1

A Byte of Python

‘A Byte of Python’ is a free book on programming using the Python language.

It serves as a tutorial or guide to the Python language for a beginner audience.

If all you know about computers is how to save text files, then this is the book

for you.

This book is written for the latest Python 3, even though Python 2 is the

commonly found version of Python today (read more about it in

1.1

Who Reads A Byte of Python?

Here are what people are saying about the book:

The best thing i found was “A Byte of Python”, which is simply a

brilliant book for a beginner. It’s well written, the concepts are well

explained with self evident examples.

–

This is the best beginner’s tutorial I’ve ever seen! Thank you for

your effort.

– Walt Michalik (wmich50-at-theramp-dot-net)

You’ve made the best Python tutorial I’ve found on the Net. Great

work. Thanks!

– Joshua Robin (joshrob-at-poczta-dot-onet-dot-pl)

Excellent gentle introduction to programming #Python for beginners

–

8

Hi, I’m from Dominican Republic. My name is Pavel, recently I read

your book ‘A Byte of Python’ and I consider it excellent!! :). I learnt

much from all the examples. Your book is of great help for newbies

like me. . .

– Pavel Simo (pavel-dot-simo-at-gmail-dot-com)

I recently finished reading Byte of Python, and I thought I really

ought to thank you. I was very sad to reach the final pages as I now

have to go back to dull, tedious oreilly or etc. manuals for learning

about python. Anyway, I really appreciate your book.

– Samuel Young (sy-one-three-seven-at-gmail-dot-com)

Dear Swaroop, I am taking a class from an instructor that has no

interest in teaching. We are using Learning Python, second edition,

by O’Reilly. It is not a text for beginner without any programming

knowledge, and an instructor that should be working in another field.

Thank you very much for your book, without it I would be clueless

about Python and programming. Thanks a million, you are able to

‘break the message down’ to a level that beginners can understand

and not everyone can.

– Joseph Duarte (jduarte1-at-cfl-dot-rr-dot-com)

I love your book! It is the greatest Python tutorial ever, and a very

useful reference. Brilliant, a true masterpiece! Keep up the good

work!

– Chris-André Sommerseth

I’m just e-mailing you to thank you for writing Byte of Python online.

I had been attempting Python for a few months prior to stumbling

across your book, and although I made limited success with pyGame,

I never completed a program.

Thanks to your simplification of the categories, Python actually seems

a reachable goal. It seems like I have finally learned the foundations

and I can continue into my real goal, game development.

9

. . .

Once again, thanks VERY much for placing such a structured and

helpful guide to basic programming on the web. It shoved me into

and out of OOP with an understanding where two text books had

failed.

– Matt Gallivan (m-underscore-gallivan12-at-hotmail-dot-com)

I would like to thank you for your book ‘A byte of python’ which i

myself find the best way to learn python. I am a 15 year old i live

in egypt my name is Ahmed. Python was my second programming

language i learn visual basic 6 at school but didn’t enjoy it, however

i really enjoyed learning python. I made the addressbook program

and i was sucessful. i will try to start make more programs and read

python programs (if you could tell me source that would be helpful).

I will also start on learning java and if you can tell me where to find

a tutorial as good as yours for java that would help me a lot. Thanx.

– Ahmed Mohammed (sedo-underscore-91-at-hotmail-dot-com)

A wonderful resource for beginners wanting to learn more about

Python is the 110-page PDF tutorial A Byte of Python by Swaroop C

H. It is well-written, easy to follow, and may be the best introduction

to Python programming available.

– Drew Ames in an article on

published on Linux.com

Yesterday I got through most of Byte of Python on my Nokia N800

and it’s the easiest and most concise introduction to Python I have

yet encountered. Highly recommended as a starting point for learning

Python.

– Jason Delport on his

Byte of Vim and Python by @swaroopch is by far the best works in

technical writing to me. Excellent reads #FeelGoodFactor

– Surendran says in a

10

“Byte of python” best one by far man

(in response to the question “Can anyone suggest a good, inexpensive

resource for learning the basics of Python?”)

– Justin LoveTrue says in a

“The Book Byte of python was very helpful ..Thanks bigtime :)”

–

Always been a fan of A Byte of Python - made for both new and

experienced programmers.

–

Patrick Harrington, in a StackOverflow answer

Even NASA

The book is even used by NASA! It is being used in their

with their Deep Space Network project.

1.2

Academic Courses

This book is/was being used as instructional material in various educational

institutions:

• ‘Principles of Programming Languages’ course at

• ‘Basic Concepts of Computing’ course at

University of California, Davis

• ‘Programming With Python’ course at

• ‘Introduction to Programming’ course at

• ‘Introduction to Application Programming’ course at

• ‘Information Technology Skills for Meteorology’ course at

• ‘Geoprocessing’ course at

• ‘Multi Agent Semantic Web Systems’ course at the

1.3

License

This book is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

license.

This means:

11

• You are free to Share i.e. to copy, distribute and transmit this book

• You are free to Remix i.e. to adapt this book

• You are free to use it for commercial purposes

Please note:

• Please do not sell electronic or printed copies of the book unless you have

clearly and prominently mentioned in the description that these are not

from the original author of this book.

• Attribution must be shown in the introductory description and front page of

the document by linking back to

http://www.swaroopch.com/notes/Python

and clearly indicating that the original text can be fetched from this

location.

• All the code/scripts provided in this book is licensed under the

unless otherwise noted.

1.4

Read Now

You can

1.5

Buy the Book

A printed hardcopy of the book can be purchased

for your offline reading pleasure,

and to support the continued development and improvement of this book.

1.6

Download

•

•

If you wish to support the continued development of this book, please

consider

1.7

Read the book in your native language

If you are interested in reading or contributing translations of this book to other

human languages, please see the

12

2

Preface

Python is probably one of the few programming languages which is both simple

and powerful. This is good for beginners as well as for experts, and more

importantly, is fun to program with. This book aims to help you learn this

wonderful language and show how to get things done quickly and painlessly - in

effect ‘The Perfect Anti-venom to your programming problems’.

2.1

Who This Book Is For

This book serves as a guide or tutorial to the Python programming language. It

is mainly targeted at newbies. It is useful for experienced programmers as well.

The aim is that if all you know about computers is how to save text files, then you

can learn Python from this book. If you have previous programming experience,

then you can also learn Python from this book.

If you do have previous programming experience, you will be interested in the

differences between Python and your favorite programming language - I have

highlighted many such differences. A little warning though, Python is soon going

to become your favorite programming language!

2.2

History Lesson

I first started with Python when I needed to write an installer for software I had

written called ‘Diamond’ so that I could make the installation easy. I had to

choose between Python and Perl bindings for the Qt library. I did some research

on the web and I came across

, a famous and

respected hacker, where he talked about how Python had become his favorite

programming language. I also found out that the PyQt bindings were more

mature compared to Perl-Qt. So, I decided that Python was the language for

me.

Then, I started searching for a good book on Python. I couldn’t find any! I

did find some O’Reilly books but they were either too expensive or were more

like a reference manual than a guide. So, I settled for the documentation that

came with Python. However, it was too brief and small. It did give a good idea

about Python but was not complete. I managed with it since I had previous

programming experience, but it was unsuitable for newbies.

About six months after my first brush with Python, I installed the (then) latest

Red Hat 9.0 Linux and I was playing around with KWord. I got excited about it

and suddenly got the idea of writing some stuff on Python. I started writing a few

pages but it quickly became 30 pages long. Then, I became serious about making

it more useful in a book form. After a lot of rewrites, it has reached a stage

13

where it has become a useful guide to learning the Python language. I consider

this book to be my contribution and tribute to the open source community.

This book started out as my personal notes on Python and I still consider it in

the same way, although I’ve taken a lot of effort to make it more palatable to

others :)

In the true spirit of open source, I have received lots of constructive suggestions,

criticisms and

from enthusiastic readers which has helped me improve

this book a lot.

2.3

Status Of The Book

This book has been reformatted in October 2012 using Pandoc to allow generation

of ebooks as requested by several users, along with errata fixes and updates.

Changes in December 2008 edition (from the earlier major revision in March

2005) was updating for the Python 3.0 release.

The book needs the help of its readers such as yourselves to point out any parts

of the book which are not good, not comprehensible or are simply wrong. Please

or the respective

with your comments and

suggestions.

2.4

Official Website

The official website of the book is

http://www.swaroopch.com/notes/Python

where you can read the whole book online, download the latest versions of the

book,

, and also send me feedback.

2.5

Something To Think About

There are two ways of constructing a software design: one way is to

make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies; the other

is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.

– C. A. R. Hoare

Success in life is a matter not so much of talent and opportunity as

of concentration and perseverance.

– C. W. Wendte

14

3

Introduction

Python is one of those rare languages which can claim to be both simple and

powerful

. You will find yourself pleasantly surprised to see how easy it is to

concentrate on the solution to the problem rather than the syntax and structure

of the language you are programming in.

The official introduction to Python is:

Python is an easy to learn, powerful programming language. It

has efficient high-level data structures and a simple but effective

approach to object-oriented programming. Python’s elegant syntax

and dynamic typing, together with its interpreted nature, make it

an ideal language for scripting and rapid application development in

many areas on most platforms.

I will discuss most of these features in more detail in the next section.

Story behind the name

Guido van Rossum, the creator of the Python lan-

guage, named the language after the BBC show “Monty Python’s Flying

Circus”. He doesn’t particularly like snakes that kill animals for food by

winding their long bodies around them and crushing them.

3.1

Features of Python

3.1.1

Simple

Python is a simple and minimalistic language. Reading a good Python program

feels almost like reading English, although very strict English! This pseudo-code

nature of Python is one of its greatest strengths. It allows you to concentrate on

the solution to the problem rather than the language itself.

3.1.2

Easy to Learn

As you will see, Python is extremely easy to get started with. Python has an

extraordinarily simple syntax, as already mentioned.

3.1.3

Free and Open Source

Python is an example of a FLOSS (Free/Libré and Open Source Software). In

simple terms, you can freely distribute copies of this software, read its source

code, make changes to it, and use pieces of it in new free programs. FLOSS is

based on the concept of a community which shares knowledge. This is one of the

reasons why Python is so good - it has been created and is constantly improved

by a community who just want to see a better Python.

15

3.1.4

High-level Language

When you write programs in Python, you never need to bother about the

low-level details such as managing the memory used by your program, etc.

3.1.5

Portable

Due to its open-source nature, Python has been ported to (i.e. changed to make

it work on) many platforms. All your Python programs can work on any of these

platforms without requiring any changes at all if you are careful enough to avoid

any system-dependent features.

You can use Python on Linux, Windows, FreeBSD, Macintosh, Solaris, OS/2,

Amiga, AROS, AS/400, BeOS, OS/390, z/OS, Palm OS, QNX, VMS, Psion,

Acorn RISC OS, VxWorks, PlayStation, Sharp Zaurus, Windows CE and even

PocketPC!

You can even use a platform like

to create games for iOS (iPhone, iPad)

and Android.

3.1.6

Interpreted

This requires a bit of explanation.

A program written in a compiled language like C or C++ is converted from the

source language i.e. C or C++ into a language that is spoken by your computer

(binary code i.e. 0s and 1s) using a compiler with various flags and options.

When you run the program, the linker/loader software copies the program from

hard disk to memory and starts running it.

Python, on the other hand, does not need compilation to binary. You just run

the program directly from the source code. Internally, Python converts the

source code into an intermediate form called bytecodes and then translates this

into the native language of your computer and then runs it. All this, actually,

makes using Python much easier since you don’t have to worry about compiling

the program, making sure that the proper libraries are linked and loaded, etc.

This also makes your Python programs much more portable, since you can just

copy your Python program onto another computer and it just works!

3.1.7

Object Oriented

Python supports procedure-oriented programming as well as object-oriented

programming. In procedure-oriented languages, the program is built around

procedures or functions which are nothing but reusable pieces of programs. In

object-oriented

languages, the program is built around objects which combine

16

data and functionality. Python has a very powerful but simplistic way of doing

OOP, especially when compared to big languages like C++ or Java.

3.1.8

Extensible

If you need a critical piece of code to run very fast or want to have some piece

of algorithm not to be open, you can code that part of your program in C or

C++ and then use it from your Python program.

3.1.9

Embeddable

You can embed Python within your C/C++ programs to give ‘scripting’ capa-

bilities for your program’s users.

3.1.10

Extensive Libraries

The Python Standard Library is huge indeed. It can help you do various things

involving regular expressions,documentation generation, unit testing, threading,

databases, web browsers, CGI, FTP, email, XML, XML-RPC, HTML, WAV

files, cryptography, GUI (graphical user interfaces), and other system-dependent

stuff. Remember, all this is always available wherever Python is installed. This

is called the Batteries Included philosophy of Python.

Besides the standard library, there are various other high-quality libraries which

you can find at the

Summary

Python is indeed an exciting and powerful language. It has the right

combination of performance and features that make writing programs in

Python both fun and easy.

3.2

Python 2 versus 3

You can ignore this section if you’re not interested in the difference between

Python 2 and Python 3. But please do be aware of which version you are using.

This book was rewritten in 2008 for Python 3. It was one of the first books to

use Python 3. This, unfortunately, resulted in confusion for readers who would

try to use Python 2 with the Python 3 version of the book and vice-versa. But

slowly, the world is still migrating to Python 3.

So, yes, you will be learning to use Python 3 in this book, even if you want

to ultimately use Python 2. Remember that once you have properly understood

and learn to use either of them, you can easily learn the changes between the

two versions and adapt easily. The hard part is learning programming and

17

understanding the core Python language itself. That is our goal in this book,

and once you have achieved that goal, you can easily use Python 2 or Python 3

depending on your situation.

For details on differences between Python 2 to Python 3, see the

3.3

What Programmers Say

You may find it interesting to read what great hackers like ESR have to say

about Python:

(1) Eric S. Raymond is the author of “The Cathedral and the Bazaar” and is

also the person who coined the term Open Source. He says that

has become his favorite programming language

. This article was the real

inspiration for my first brush with Python.

(2) Bruce Eckel is the author of the famous Thinking in Java and Thinking in

C++

books. He says that no language has made him more productive than

Python. He says that Python is perhaps the only language that focuses on

making things easier for the programmer. Read the

for

more details.

(3) Peter Norvig is a well-known Lisp author and Director of Search Quality

at Google (thanks to Guido van Rossum for pointing that out). He says

that Python has always been an integral part of Google. You can actually

verify this statement by looking at the

page which lists Python

knowledge as a requirement for software engineers.

4

Installation

4.1

Installation on Windows

Visit

http://www.python.org/download/

and download the latest version. The

installation is just like any other Windows-based software.

Caution

When you are given the option of unchecking any “optional” compo-

nents, don’t uncheck any.

4.1.1

DOS Prompt

If you want to be able to use Python from the Windows command line i.e. the

DOS prompt, then you need to set the PATH variable appropriately.

18

For Windows 2000, XP, 2003 , click on Control Panel — System — Advanced

— Environment Variables. Click on the variable named PATH in the ‘System

Variables’ section, then select Edit and add ;C:\Python33 (please verify that

this folder exists, it will be different for newer versions of Python) to the end of

what is already there. Of course, use the appropriate directory name.

For older versions of Windows, open the file C:\AUTOEXEC.BAT and add the line

‘PATH=%PATH%;C:\Python33’ (without the quotes) and restart the system. For

Windows NT, use the AUTOEXEC.NT file.

For Windows Vista:

1. Click Start and choose Control Panel

2. Click System, on the right you’ll see “View basic information about your

computer”

3. On the left is a list of tasks, the last of which is “Advanced system settings.”

Click that.

4. The Advanced tab of the System Properties dialog box is shown. Click the

Environment Variables button on the bottom right.

5. In the lower box titled “System Variables” scroll down to Path and click

the Edit button.

6. Change your path as need be.

7. Restart your system. Vista didn’t pick up the system path environment

variable change until I restarted.

For Windows 7:

1. Right click on Computer from your desktop and select properties or Click

Start and choose Control Panel — System and Security — System. Click

on Advanced system settings on the left and then click on the Advanced

tab. At the bottom click on Environment Variables and under System

variables, look for the PATH variable, select and then press Edit.

2. Go to the end of the line under Variable value and append ;C:\Python33.

3. If the value was %SystemRoot%\system32; It will now become

%SystemRoot%\system32;C:\Python33

4. Click ok and you are done. No restart is required.

4.1.2

Running Python prompt on Windows

For Windows users, you can run the interpreter in the command line if you have

set the PATH variable appropriately

To open the terminal in Windows, click the start button and click ‘Run’. In the

dialog box, type cmd and press enter key.

Then, type python3 -V and ensure there are no errors.

19

4.2

Installation on Mac OS X

For Mac OS X users, open the terminal by pressing Command+Space keys (to

open Spotlight search), type Terminal and press enter key.

Install

by running:

ruby -e "$(curl -fsSkL raw.github.com/mxcl/homebrew/go)"

Then install Python 3 using:

brew install python3

Now, run python3 -V and ensure there are no errors.

4.3

Installation on Linux

For Linux users, open the terminal by opening the Terminal application or by

pressing Alt + F2 and entering gnome-terminal. If that doesn’t work, please

refer the documentation or forums of your particular Linux distribution.

Next, we have to install the python3 package. For example, on Ubuntu, you

can use

. Please check the documentation or

forums of the Linux distribution that you have installed for the correct package

manager command to run.

Once you have finished the installation, run the python3 -V command in a shell

and you should see the version of Python on the screen:

$ python3 -V

Python 3.3.0

Note

$ is the prompt of the shell. It will be different for you depending on the

settings of the operating system on your computer, hence I will indicate

the prompt by just the $ symbol.

Default in new versions of your distribution?

Newer distributions such

as

Ubuntu 12.10 are making Python 3 the default version

, so check if it is

already installed.

4.4

Summary

From now on, we will assume that you have Python 3 installed on your system.

Next, we will write our first Python 3 program.

20

5

First Steps

We will now see how to run a traditional ‘Hello World’ program in Python. This

will teach you how to write, save and run Python programs.

There are two ways of using Python to run your program - using the interactive

interpreter prompt or using a source file. We will now see how to use both of

these methods.

5.1

Using The Interpreter Prompt

Open the terminal in your operating system (as discussed previously in the

) and then open the Python prompt by typing python3 and

pressing enter key.

Once you have started python3, you should see >>> where you can start typing

stuff. This is called the Python interpreter prompt.

At the Python interpreter prompt, type print(’Hello World’) followed by the

enter key. You should see the words Hello World as output.

Here is an example of what you should be seeing, when using a Mac OS X

computer. The details about the Python software will differ based on your

computer, but the part from the prompt (i.e. from >>> onwards) should be the

same regardless of the operating system.

$ python3

Python 3.3.0 (default, Oct 22 2012, 12:20:36)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple Clang 4.0 ((tags/Apple/clang-421.0.60))] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> print('hello world')

hello world

>>>

Notice that Python gives you the output of the line immediately! What you just

entered is a single Python statement. We use print to (unsurprisingly) print

any value that you supply to it. Here, we are supplying the text Hello World

and this is promptly printed to the screen.

How to Quit the Interpreter Prompt

If you are using a Linux or Unix

shell, you can exit the interpreter prompt by pressing ctrl-d or entering

exit() (note: remember to include the parentheses, ‘()’) followed by the

enter key. If you are using the Windows command prompt, press ctrl-z

followed by the enter key.

21

5.2

Choosing An Editor

We cannot type out our program at the interpreter prompt every time we want

to run something, so we have to save them in files and can run our programs

any number of times.

To create our Python source files, we need an editor software where you can type

and save. A good programmer’s editor will make your life easier in writing the

source files. Hence, the choice of an editor is crucial indeed. You have to choose

an editor as you would choose a car you would buy. A good editor will help you

write Python programs easily, making your journey more comfortable and helps

you reach your destination (achieve your goal) in a much faster and safer way.

One of the very basic requirements is syntax highlighting where all the different

parts of your Python program are colorized so that you can see your program

and visualize its running.

If you have no idea where to start, I would recommend using

software which is available on Windows, Mac OS X and Linux.

If you are using Windows, do not use Notepad - it is a bad choice because

it does not do syntax highlighting and also importantly it does not support

indentation of the text which is very important in our case as we will see later.

Good editors such as Komodo Edit will automatically do this.

If you are an experienced programmer, then you must be already using

or

. Needless to say, these are two of the most powerful editors and you

will benefit from using them to write your Python programs. I personally use

both for most of my programs, and have even written an

In case you are willing to take the time to learn Vim or Emacs, then I highly

recommend that you do learn to use either of them as it will be very useful for

you in the long run. However, as I mentioned before, beginners can start with

Komodo Edit and focus the learning on Python rather than the editor at this

moment.

To reiterate, please choose a proper editor - it can make writing Python programs

more fun and easy.

For Vim users

There is a good introduction on how to

. Also recommended is the

and my

For Emacs users

There is a good introduction on how to

erful Python IDE by Pedro Kroger

. Also recommended is

22

5.3

Using A Source File

Now let’s get back to programming. There is a tradition that whenever you

learn a new programming language, the first program that you write and run is

the ‘Hello World’ program - all it does is just say ‘Hello World’ when you run it.

As Simon Cozens (the author of the amazing ‘Beginning Perl’ book) puts it, it

is the “traditional incantation to the programming gods to help you learn the

language better.”

Start your choice of editor, enter the following program and save it as hello.py.

If you are using Komodo Edit, click on File — New — New File, type the lines:

(

'Hello World'

)

In Komodo Edit, do File — Save to save to a file.

Where should you save the file? To any folder for which you know the location

of the folder. If you don’t understand what that means, create a new folder and

use that location to save and run all your Python programs:

• C:\\py on Windows

• /tmp/py on Linux

• /tmp/py on Mac OS X

To create a folder, use the mkdir command in the terminal, for example, mkdir

/tmp/py.

Important

Always ensure that you give it the file extension of .py, for example,

foo.py.

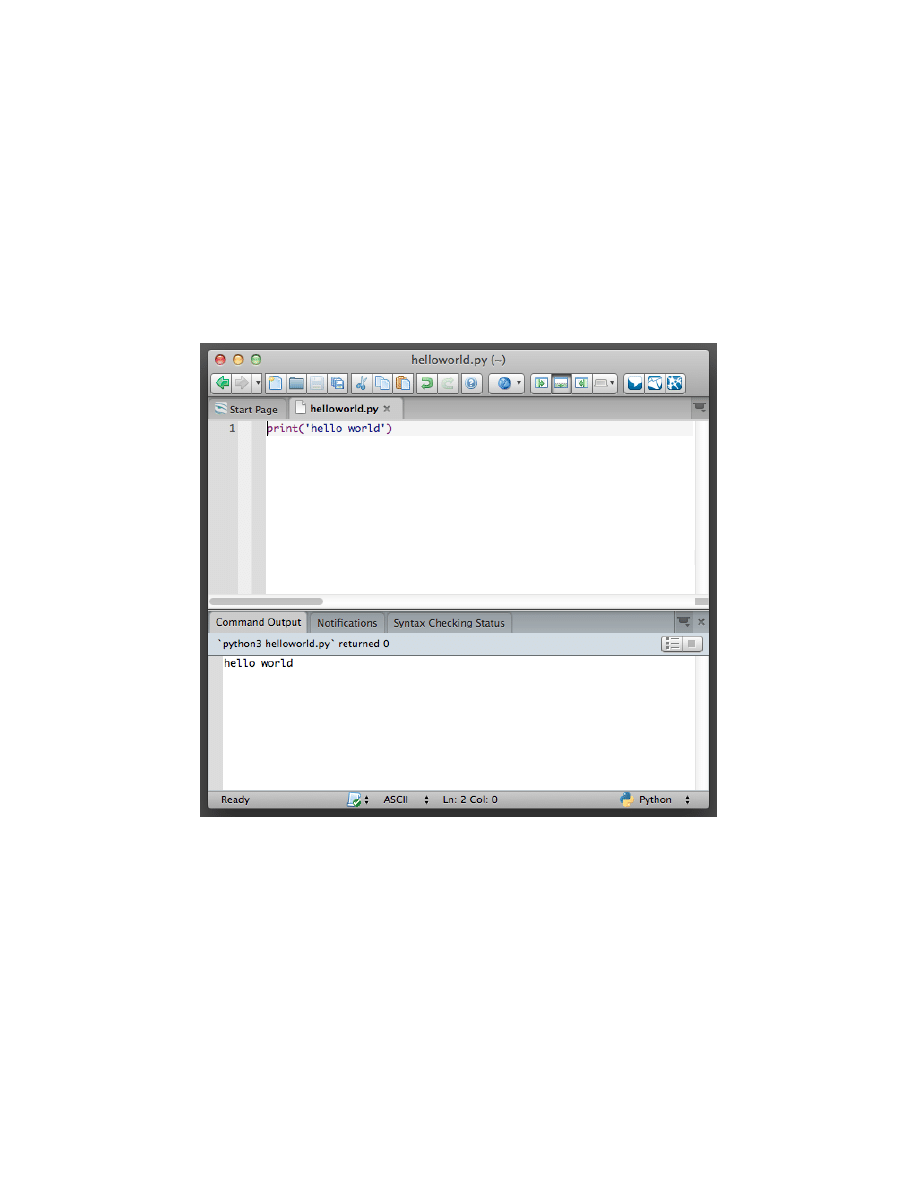

In Komodo Edit, click on Tools — Run Command, type python3 hello.py and

click on Run and you should see the output printed like in the screenshot below.

The best way, though, is to type it in Komodo Edit but to use a terminal:

1. Open a terminal as explained in the

2. Change directory where you saved the file, for example, cd /tmp/py

3. Run the program by entering the command python3 hello.py.

The output is as shown below.

$ python3 hello.py

Hello World

23

Figure 1: Screenshot of Komodo Edit with the Hello World program

24

If you got the output as shown above, congratulations! - you have successfully

run your first Python program. You have successfully crossed the hardest part

of learning programming, which is, getting started with your first program!

In case you got an error, please type the above program exactly as shown above

and run the program again. Note that Python is case-sensitive i.e. print is not

the same as Print - note the lowercase p in the former and the uppercase P in

the latter. Also, ensure there are no spaces or tabs before the first character in

each line - we will

see why this is important later

How It Works

A Python program is composed of statements. In our first program, we have

only one statement. In this statement, we call the print function which just

prints the text ’Hello World’. We will learn about functions in detail in a

- what you should understand now is that whatever you supply in the

parentheses will be printed back to the screen. In this case, we supply the text

’Hello World’.

5.3.1

Executable Python Programs

This applies only to Linux and Unix users but Windows users should know this

as well.

Every time, you want to run a Python program, we have to explicitly call

python3 foo.py, but why can’t we run it just like any other program on our

computer? We can achieve that by using something called the hashbang line.

Add the below line as the first line of your program:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

So, your program should look like this now:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

(

'Hello World'

)

Second, we have to give the program executable permission using the chmod

command then run the source program.

The chmod command is used here to change the mode of the file by giving

execute permission to all users of the system.

$ chmod a+x hello.py

Now, we can run our program directly because our operating system calls

/usr/bin/env which in turn will find our Python 3 software and hence knows

how to run our source file:

25

$ ./hello.py

Hello World

We use the ./ to indicate that the program is located in the current folder.

To make things more fun, you can rename the file to just hello and run it as

./hello and it will still work since the system knows that it has to run the

program using the interpreter whose location is specified in the first line in the

source file.

So far, we have been able to run our program as long as we know the exact

path. What if we wanted to be able to run the program from folder? You can do

this by storing the program in one of the folders listed in the PATH environment

variable.

Whenever you run any program, the system looks for that program in each of

the folders listed in the PATH environment variable and then runs that program.

We can make this program available everywhere by simply copying this source

file to one of the directories listed in PATH.

$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/X11R6/bin:/home/swaroop/bin

$ cp hello.py /home/swaroop/bin/hello

$ hello

Hello World

We can display the PATH variable using the echo command and prefixing the

variable name by $ to indicate to the shell that we need the value of this

“environment variable”. We see that /home/swaroop/bin is one of the directories

in the PATH variable where swaroop is the username I am using in my system.

There will usually be a similar directory for your username on your system.

If you want to add a directory of your choice to the PATH variable - this

can be done by running export PATH=$PATH:/home/swaroop/mydir where

’/home/swaroop/mydir’ is the directory I want to add to the PATH variable.

This method is very useful if you want to write commands you can run anytime,

anywhere. It is like creating your own commands just like cd or any other

commands that you use in the terminal.

5.4

Getting Help

If you need quick information about any function or statement in Python, then

you can use the built-in help functionality. This is very useful especially when

using the interpreter prompt. For example, run help(print) - this displays the

help for the print function which is used to print things to the screen.

26

Note

Press q to exit the help.

Similarly, you can obtain information about almost anything in Python. Use

help() to learn more about using help itself!

In case you need to get help for operators like return, then you need to put

those inside quotes such as help(’return’) so that Python doesn’t get confused

on what we’re trying to do.

5.5

Summary

You should now be able to write, save and run Python programs at ease.

Now that you are a Python user, let’s learn some more Python concepts.

6

Basics

Just printing ‘Hello World’ is not enough, is it? You want to do more than that

- you want to take some input, manipulate it and get something out of it. We

can achieve this in Python using constants and variables, and we’ll learn some

other concepts as well in this chapter.

6.1

Comments

Comments

are any text to the right of the # symbol and is mainly useful as notes

for the reader of the program.

For example:

(

'Hello World'

)

# Note that print is a function

or:

# Note that print is a function

(

'Hello World'

)

Use as many useful comments as you can in your program to:

• explain assumptions

• explain important decisions

• explain important details

• explain problems you’re trying to solve

27

• explain problems you’re trying to overcome in your program, etc.

Code tells you how, comments should tell you why.

This is useful for readers of your program so that they can easily understand

what the program is doing. Remember, that person can be yourself after six

months!

6.2

Literal Constants

An example of a literal constant is a number like 5, 1.23, or a string like ’This

is a string’or "It’s a string!". It is called a literal because it is literal -

you use its value literally. The number 2 always represents itself and nothing

else - it is a constant because its value cannot be changed. Hence, all these are

referred to as literal constants.

6.3

Numbers

Numbers are mainly of two types - integers and floats.

An examples of an integer is 2 which is just a whole number.

Examples of floating point numbers (or floats for short) are 3.23 and 52.3E-4.

The E notation indicates powers of 10. In this case, 52.3E-4 means 52.3 *

10ˆ-4ˆ.

Note for Experienced Programmers

There is no separate long type. The

int type can be an integer of any size.

6.4

Strings

A string is a sequence of characters. Strings are basically just a bunch of words.

You will be using strings in almost every Python program that you write, so pay

attention to the following part.

6.4.1

Single Quote

You can specify strings using single quotes such as ’Quote me on this’. All

white space i.e. spaces and tabs are preserved as-is.

6.4.2

Double Quotes

Strings in double quotes work exactly the same way as strings in single quotes.

An example is "What’s your name?"

28

6.4.3

Triple Quotes

You can specify multi-line strings using triple quotes - (""" or ”’). You can use

single quotes and double quotes freely within the triple quotes. An example is:

'''This is a multi-line string. This is the first line.

This is the second line.

"What's your name?," I asked.

He said "Bond, James Bond."

'''

6.4.4

Strings Are Immutable

This means that once you have created a string, you cannot change it. Although

this might seem like a bad thing, it really isn’t. We will see why this is not a

limitation in the various programs that we see later on.

Note for C/C++ Programmers

There is no separate char data type in

Python. There is no real need for it and I am sure you won’t miss it.

Note for Perl/PHP Programmers

Remember that single-quoted strings

and double-quoted strings are the same - they do not differ in any way.

6.4.5

The format method

Sometimes we may want to construct strings from other information. This is

where the format() method is useful.

Save the following lines as a file str_format.py:

age =

20

name =

'Swaroop'

(

'{0} was {1} years old when he wrote this book'

.

format

(name, age))

(

'Why is {0} playing with that python?'

.

format

(name))

Output:

$ python3 str_format.py

Swaroop was 20 years old when he wrote this book

Why is Swaroop playing with that python?

29

How It Works:

A string can use certain specifications and subsequently, the format method can

be called to substitute those specifications with corresponding arguments to the

format method.

Observe the first usage where we use {0} and this corresponds to the variable

name which is the first argument to the format method. Similarly, the second

specification is {1} corresponding to age which is the second argument to the

format method. Note that Python starts counting from 0 which means that first

position is at index 0, second position is at index 1, and so on.

Notice that we could have achieved the same using string concatenation: name +

’ is ’ + str(age) + ’ years old’ but that is much uglier and error-prone.

Second, the conversion to string would be done automatically by the format

method instead of the explicit conversion to strings needed in this case. Third,

when using the format method, we can change the message without having to

deal with the variables used and vice-versa.

Also note that the numbers are optional, so you could have also written as:

age =

20

name =

'Swaroop'

(

'{} was {} years old when he wrote this book'

.

format

(name, age))

(

'Why is {} playing with that python?'

.

format

(name))

which will give the same exact output as the previous program.

What Python does in the format method is that it substitutes each argument

value into the place of the specification. There can be more detailed specifications

such as:

decimal (.) precision of

3

for

float

'0.333'

>>>

'{0:.3}'

.

format

(

1

/

3

)

fill

with

underscores (_)

with

the text centered

(^) to

11

width

'___hello___'

>>>

'{0:_^11}'

.

format

(

'hello'

)

keyword-based

'Swaroop wrote A Byte of Python'

>>>

'{name} wrote {book}'

.

format

(name=

'Swaroop'

, book=

'A Byte of Python'

)

6.5

Variable

Using just literal constants can soon become boring - we need some way of

storing any information and manipulate them as well. This is where variables

come into the picture. Variables are exactly what the name implies - their value

can vary, i.e., you can store anything using a variable. Variables are just parts

30

of your computer’s memory where you store some information. Unlike literal

constants, you need some method of accessing these variables and hence you

give them names.

6.6

Identifier Naming

Variables are examples of identifiers. Identifiers are names given to identify

something

. There are some rules you have to follow for naming identifiers:

• The first character of the identifier must be a letter of the alphabet (up-

percase ASCII or lowercase ASCII or Unicode character) or an underscore

(‘_’).

• The rest of the identifier name can consist of letters (uppercase ASCII or

lowercase ASCII or Unicode character), underscores (‘_’) or digits (0-9).

• Identifier names are case-sensitive. For example, myname and myName are

not

the same. Note the lowercase n in the former and the uppercase N in

the latter.

• Examples of valid identifier names are i, __my_name, name_23. Examples

of ‘’invalid” identifier names are 2things, this is spaced out, my-name,

>a1b2_c3 and "this_is_in_quotes".

6.7

Data Types

Variables can hold values of different types called data types. The basic types

are numbers and strings, which we have already discussed. In later chapters, we

will see how to create our own types using

6.8

Object

Remember, Python refers to anything used in a program as an object. This is

meant in the generic sense. Instead of saying ‘the something’, we say ‘the object’.

Note for Object Oriented Programming users

Python is strongly object-

oriented in the sense that everything is an object including numbers, strings

and functions.

We will now see how to use variables along with literal constants. Save the

following example and run the program.

31

6.9

How to write Python programs

Henceforth, the standard procedure to save and run a Python program is as

follows:

1. Open your editor of choice, such as Komodo Edit.

2. Type the program code given in the example.

3. Save it as a file with the filename mentioned.

4. Run the interpreter with the command python3 program.py to run the

program.

6.10

Example: Using Variables And Literal Constants

Filename : var.py

i =

5

(i)

i = i +

1

(i)

s =

'''This is a multi-line string.

This is the second line.'''

(s)

Output:

$ python3 var.py

5

6

This is a multi-line string.

This is the second line.

How It Works:

Here’s how this program works. First, we assign the literal constant value 5 to

the variable i using the assignment operator (=). This line is called a statement

because it states that something should be done and in this case, we connect the

variable name i to the value 5. Next, we print the value of i using the print

function which, unsurprisingly, just prints the value of the variable to the screen.

Then we add 1 to the value stored in i and store it back. We then print it and

expectedly, we get the value 6.

Similarly, we assign the literal string to the variable s and then print it.

Note for static language programmers

Variables are used by just assigning

them a value. No declaration or data type definition is needed/used.

32

6.10.1

Logical And Physical Line

A physical line is what you see when you write the program. A logical line is

what Python sees as a single statement. Python implicitly assumes that each

physical line

corresponds to a logical line.

An example of a logical line is a statement like print(’Hello World’) - if this

was on a line by itself (as you see it in an editor), then this also corresponds to

a physical line.

Implicitly, Python encourages the use of a single statement per line which makes

code more readable.

If you want to specify more than one logical line on a single physical line, then

you have to explicitly specify this using a semicolon (;) which indicates the end

of a logical line/statement. For example,

i =

5

(i)

is effectively same as

i =

5

;

(i);

and the same can be written as

i =

5

;

(i);

or even

i =

5

;

(i)

However, I strongly recommend that you stick to writing a maximum of a

single logical line on each single physical line

. The idea is that you should

never use the semicolon. In fact, I have never used or even seen a semicolon in a

Python program.

There is one kind of situation where this concept is really useful : if you have

a long line of code, you can break it into multiple physical lines by using the

backslash. This is referred to as explicit line joining:

s =

'This is a string. \

This continues the string.'

(s)

33

This gives the output:

This is a string. This continues the string.

Similarly,

\

(i)

is the same as

(i)

Sometimes, there is an implicit assumption where you don’t need to use a

backslash. This is the case where the logical line has a starting parentheses,

starting square brackets or a starting curly braces but not an ending one. This is

called implicit line joining. You can see this in action when we write programs

using

in later chapters.

6.10.2

Indentation

Whitespace is important in Python. Actually, whitespace at the beginning

of the line is important

. This is called indentation. Leading whitespace

(spaces and tabs) at the beginning of the logical line is used to determine the

indentation level of the logical line, which in turn is used to determine the

grouping of statements.

This means that statements which go together must have the same indentation.

Each such set of statements is called a block. We will see examples of how

blocks are important in later chapters.

One thing you should remember is that wrong indentation can give rise to errors.

For example:

i =

5

(

'Value is '

, i)

# Error! Notice a single space at the start of the line

(

'I repeat, the value is '

, i)

When you run this, you get the following error:

File "whitespace.py", line 4

print('Value is ', i) # Error! Notice a single space at the start of the line

^

IndentationError: unexpected indent

34

Notice that there is a single space at the beginning of the second line. The error

indicated by Python tells us that the syntax of the program is invalid i.e. the

program was not properly written. What this means to you is that you cannot

arbitrarily start new blocks of statements

(except for the default main block

which you have been using all along, of course). Cases where you can use new

blocks will be detailed in later chapters such as the

How to indent

Use only spaces for indentation, with a tab stop of 4 spaces.

Good editors like Komodo Edit will automatically do this for you. Make

sure you use a consistent number of spaces for indentation, otherwise your

program will show errors.

Note to static language programmers

Python will always use indentation

for blocks and will never use braces. Run from __future__ import

braces to learn more.

6.11

Summary

Now that we have gone through many nitty-gritty details, we can move on

to more interesting stuff such as control flow statements. Be sure to become

comfortable with what you have read in this chapter.

7

Operators and Expressions

Most statements (logical lines) that you write will contain expressions. A simple

example of an expression is 2 + 3. An expression can be broken down into

operators and operands.

Operators

are functionality that do something and can be represented by symbols

such as + or by special keywords. Operators require some data to operate on

and such data is called operands. In this case, 2 and 3 are the operands.

7.1

Operators

We will briefly take a look at the operators and their usage:

Note that you can evaluate the expressions given in the examples using the

interpreter interactively. For example, to test the expression 2 + 3, use the

interactive Python interpreter prompt:

>>>

2

+

3

5

>>>

3

*

5

35

15

>>>

+ (plus)

Adds two objects

3 + 5 gives 8. ’a’ + ’b’ gives ’ab’.

- (minus)

Gives the subtraction of one number from the other; if the first

operand is absent it is assumed to be zero.

-5.2 gives a negative number and 50 - 24 gives 26.

* (multiply)

Gives the multiplication of the two numbers or returns the string

repeated that many times.

2 * 3 gives 6. ’la’ * 3 gives ’lalala’.

** (power)

Returns x to the power of y

3 ** 4 gives 81 (i.e. 3 * 3 * 3 * 3)

/ (divide)

Divide x by y

4 / 3 gives 1.3333333333333333.

// (floor division)

Returns the floor of the quotient

4 // 3 gives 1.

% (modulo)

Returns the remainder of the division

8 % 3 gives 2. -25.5 % 2.25 gives 1.5.

<< (left shift)

Shifts the bits of the number to the left by the number of bits

specified. (Each number is represented in memory by bits or binary digits

i.e. 0 and 1)

2 << 2 gives 8. 2 is represented by 10 in bits.

Left shifting by 2 bits gives 1000 which represents the decimal 8.

>> (right shift)

Shifts the bits of the number to the right by the number of

bits specified.

11 >> 1 gives 5.

11 is represented in bits by 1011 which when right shifted by 1 bit gives

101which is the decimal 5.

& (bit-wise AND)

Bit-wise AND of the numbers

5 & 3 gives 1.

| (bit-wise OR)

Bitwise OR of the numbers

5 | 3 gives 7

36

ˆ (bit-wise XOR)

Bitwise XOR of the numbers

5 ˆ 3 gives 6

~ (bit-wise invert)

The bit-wise inversion of x is -(x+1)

~5 gives -6.

< (less than)

Returns whether x is less than y. All comparison operators return

True or False. Note the capitalization of these names.

5 < 3 gives False and 3 < 5 gives True.

Comparisons can be chained arbitrarily: 3 < 5 < 7 gives True.

> (greater than)

Returns whether x is greater than y

5 > 3 returns True. If both operands are numbers, they are first

converted to a common type. Otherwise, it always returns False.

<= (less than or equal to)

Returns whether x is less than or equal to y

x = 3; y = 6; x <= y returns True.

>= (greater than or equal to)

Returns whether x is greater than or equal to

y

x = 4; y = 3; x >= 3 returns True.

== (equal to)

Compares if the objects are equal

x = 2; y = 2; x == y returns True.

x = ’str’; y = ’stR’; x == y returns False.

x = ’str’; y = ’str’; x == y returns True.

!= (not equal to)

Compares if the objects are not equal

x = 2; y = 3; x != y returns True.

not (boolean NOT)

If x is True, it returns False. If x is False, it returns

True.

x = True; not x returns False.

and (boolean AND)

x and y returns False if x is False, else it returns

evaluation of y

x = False; y = True; x and y returns False since x is False. In this

case, Python will not evaluate y since it knows that the left hand side

of the ‘and’ expression is False which implies that the whole expression

will be False irrespective of the other values. This is called short-circuit

evaluation.

or (boolean OR)

If x is True, it returns True, else it returns evaluation of y

x = True; y = False; x or y returns True. Short-circuit evaluation

applies here as well.

37

7.1.1

Shortcut for math operation and assignment

It is common to run a math operation on a variable and then assign the result of

the operation back to the variable, hence there is a shortcut for such expressions:

You can write:

a =

2

a = a *

3

as:

a =

2

a *=

3

Notice that var = var operation expression becomes var operation=

expression.

7.2

Evaluation Order

If you had an expression such as 2 + 3 * 4, is the addition done first or the

multiplication? Our high school maths tells us that the multiplication should be

done first. This means that the multiplication operator has higher precedence

than the addition operator.

The following table gives the precedence table for Python, from the lowest

precedence (least binding) to the highest precedence (most binding). This

means that in a given expression, Python will first evaluate the operators and

expressions lower in the table before the ones listed higher in the table.

The following table, taken from the

, is provided for

the sake of completeness. It is far better to use parentheses to group operators

and operands appropriately in order to explicitly specify the precedence. This

makes the program more readable. See

Changing the Order of Evaluation

below

for details.

lambda

Lambda Expression

or

Boolean OR

and

Boolean AND

not x

Boolean NOT

in, not in

Membership tests

is, is not

Identity tests

38

<, <=, >, >=, !=, ==

Comparisons

|

Bitwise OR

ˆ

Bitwise XOR

&

Bitwise AND

<<, >>

Shifts

+, -

Addition and subtraction

*, /, //, %

Multiplication, Division, Floor Division and Remainder

+x, -x

Positive, Negative

~x

Bitwise NOT

**

Exponentiation

x.attribute

Attribute reference

x[index]

Subscription

x[index1:index2]

Slicing

f(arguments ...)

Function call

(expressions, ...)

Binding or tuple display

[expressions, ...]

List display

{key:datum, ...}

Dictionary display

The operators which we have not already come across will be explained in later

chapters.

Operators with the same precedence are listed in the same row in the above

table. For example, + and - have the same precedence.

7.3

Changing the Order Of Evaluation

To make the expressions more readable, we can use parentheses. For example,

2 + (3 * 4) is definitely easier to understand than 2 + 3 * 4 which requires

knowledge of the operator precedences. As with everything else, the parentheses

should be used reasonably (do not overdo it) and should not be redundant, as in

(2 + (3 * 4)).

There is an additional advantage to using parentheses - it helps us to change the

order of evaluation. For example, if you want addition to be evaluated before

multiplication in an expression, then you can write something like (2 + 3) * 4.

39

7.4

Associativity

Operators are usually associated from left to right. This means that operators

with the same precedence are evaluated in a left to right manner. For example, 2

+ 3 + 4 is evaluated as (2 + 3) + 4. Some operators like assignment operators

have right to left associativity i.e. a = b = c is treated as a = (b = c).

7.5

Expressions

Example (save as expression.py):

length =

5

breadth =

2

area = length * breadth

(

'Area is'

, area)

(

'Perimeter is'

,

2

* (length + breadth))

Output:

$ python3 expression.py

Area is 10

Perimeter is 14

How It Works:

The length and breadth of the rectangle are stored in variables by the same

name. We use these to calculate the area and perimeter of the rectangle with the

help of expressions. We store the result of the expression length * breadth

in the variable area and then print it using the print function. In the second

case, we directly use the value of the expression 2 * (length + breadth) in

the print function.

Also, notice how Python ‘pretty-prints’ the output. Even though we have not

specified a space between ’Area is’ and the variable area, Python puts it for

us so that we get a clean nice output and the program is much more readable

this way (since we don’t need to worry about spacing in the strings we use for

output). This is an example of how Python makes life easy for the programmer.

7.6

Summary

We have seen how to use operators, operands and expressions - these are the

basic building blocks of any program. Next, we will see how to make use of these

in our programs using statements.

40

8

Control Flow

In the programs we have seen till now, there has always been a series of statements

faithfully executed by Python in exact top-down order. What if you wanted to

change the flow of how it works? For example, you want the program to take

some decisions and do different things depending on different situations, such as

printing ‘Good Morning’ or ‘Good Evening’ depending on the time of the day?

As you might have guessed, this is achieved using control flow statements. There

are three control flow statements in Python - if, for and while.

8.1

The if statement

The if statement is used to check a condition: if the condition is true, we

run a block of statements (called the if-block), else we process another block of

statements (called the else-block). The else clause is optional.

Example (save as if.py):

number =

23

guess =

int

(

input

(

'Enter an integer : '

))

if

guess == number:

(

'Congratulations, you guessed it.'

)

# New block starts here

(

'(but you do not win any prizes!)'

)

# New block ends here

elif

guess < number:

(

'No, it is a little higher than that'

)

# Another block

# You can do whatever you want in a block ...

else

:

(

'No, it is a little lower than that'

)

# you must have guessed > number to reach here

(

'Done'

)

# This last statement is always executed, after the if statement is executed

Output:

$ python3 if.py

Enter an integer : 50

No, it is a little lower than that

Done

$ python3 if.py

Enter an integer : 22

No, it is a little higher than that

41

Done

$ python3 if.py

Enter an integer : 23

Congratulations, you guessed it.

(but you do not win any prizes!)

Done

How It Works:

In this program, we take guesses from the user and check if it is the number that

we have. We set the variable number to any integer we want, say 23. Then, we

take the user’s guess using the input() function. Functions are just reusable

pieces of programs. We’ll read more about them in the

We supply a string to the built-in input function which prints it to the screen

and waits for input from the user. Once we enter something and press enter key,

the input() function returns what we entered, as a string. We then convert this

string to an integer using int and then store it in the variable guess. Actually,

the int is a class but all you need to know right now is that you can use it to

convert a string to an integer (assuming the string contains a valid integer in

the text).

Next, we compare the guess of the user with the number we have chosen. If they

are equal, we print a success message. Notice that we use indentation levels to

tell Python which statements belong to which block. This is why indentation is

so important in Python. I hope you are sticking to the “consistent indentation”

rule. Are you?

Notice how the if statement contains a colon at the end - we are indicating to

Python that a block of statements follows.

Then, we check if the guess is less than the number, and if so, we inform the user

that they must guess a little higher than that. What we have used here is the

elif clause which actually combines two related if else-if else statements

into one combined if-elif-else statement. This makes the program easier

and reduces the amount of indentation required.

The elif and else statements must also have a colon at the end of the logical

line followed by their corresponding block of statements (with proper indentation,

of course)

You can have another if statement inside the if-block of an if statement and

so on - this is called a nested if statement.

Remember that the elif and else parts are optional. A minimal valid if

statement is:

if

True

:

(

'Yes, it is true'

)

42