http://lal.sagepub.com

Language and Literature

2002; 11; 55

Language and Literature

Peter Crisp, John Heywood and Gerard Steen

Metaphor identification and analysis, classification and quantification

http://lal.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/11/1/55

The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Poetics and Linguistics Association

can be found at:

Language and Literature

Additional services and information for

http://lal.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

http://lal.sagepub.com/subscriptions

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

A

RT I C L E

Language and Literature Copyright © 2002 SAGE Publications

(London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi), Vol 11(1): 55–69

[0963–9470 (200202) 11:1; 55–69; 020844]

Metaphor identification and analysis, classification and

quantification

Peter Crisp, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

John Heywood, Lancaster University, UK

Gerard Steen, Free University Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Abstract

Identifying metaphorically used words in the way we have proposed in the other articles

in this special issue inevitably leads to the detection of recurring structural patterns of

metaphor usage. It is the aim of the present article to explore these patterns in a

systematic fashion and develop a taxomony of the propositional structure of metaphors.

As a preliminary step, a decision has to be made about the units of discourse within

which one may examine patterns of the propositional structure of metaphorical

language. This article has adopted the position that all non-downgraded clauses, in the

manner of Mann and Thompson’s Rhetorical Structure Theory (1988), would be the

most eligible candidate.

Inside the boundaries of these text units, we have found single as opposed to

multiple metaphor, simple as opposed to complex metaphor, pure as opposed to mixed

metaphor, and restricted as opposed to extended metaphor. Moreover, these four

oppositions may also be combined with each other. Of the 16 logically possible

combinations, 2 are ruled out, but the other 14 combinations present just as many

structural types of metaphor.

We then move on to discuss how such a taxonomy may be used in the quantitative

characterization of the metaphorical style of an author. We show how the taxonomy

may be applied at various levels of measurement, ranging from the word through the

proposition to the text unit itself. Another possibility is to perform these measurements

at the level of metaphorical mappings, which is the option we have chosen to apply to

two stretches of fiction, by Sara Maitland and Salman Rushdie. The provisional results

of this analysis are then finally presented and discussed.

Keywords: complex metaphor; extended metaphor; multiple metaphor; propositional

structure; pure metaphor; restricted metaphor; simple metaphor; single metaphor

1 Introduction

A major advantage of the detailed approach we have taken to identifying

metaphor in naturally occurring discourse is that a number of distinct patterns of

metaphorical language use, and of the propositional structures underlying these,

have forced themselves upon our attention. Some at least of these patterns would

almost certainly have been overlooked by a more casual approach. Consider for

instance the differences between the following expressions containing

metaphorically used words from the Maitland (1990) text analysed by Heywood

et al. (2002):

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

(1)

Rachel seemed able to absorb everything that Phoebe tried.

(2)

He had set his mark on them.

(3)

Phoebe … asked herself with a sudden rush of nostalgia.

(4)

That was the stuff of melodrama.

The first sentence contains only one metaphorically used word, while each of (2)

through (4) contains two. Moreover in both (2) and (3) the two metaphorically

used words seem to denote in the same source domain whereas this is clearly not

the case for (4). There is also a further difference between (2) and (3). Whereas in

(2) the two metaphorically used words express two elements of the underlying

main metaphorical proposition, the predicate concept SET and the argument

concept MARK, in (3) the two words of sudden rush express what is just a single

argument in the underlying main metaphorical proposition, but an argument

containing some kind of internal semantic complexity.

This article will be devoted to establishing a taxonomy for metaphor that will

enable the differences of metaphorical language patterning noted in the four

sentences above to be classified systematically. In establishing this taxonomy we

will work with the three analytic levels of the surface linguistic expression, the

proposition and the conceptual mapping. All three of these levels are essential.

The importance of the linguistic expression is evident, as, in the context of

contemporary metaphor theory, is that of the conceptual mapping. The necessity

of working also with the intermediate level of the proposition is a central

assumption of our approach, one that was argued for in the first papers of this

special issue (Crisp, 2002; Steen, 2002). Propositional analysis we will see is an

essential tool in constructing a useful taxonomy of metaphor. We shall see, for

instance, that it would be difficult to account within a conceptually oriented

approach for the differences in metaphorical patterning between (2) and (3) above

without employing propositional analysis.

There are several advantages to creating a taxonomy of metaphor types of the

kind that we will present, but an important one is the possibility of the

quantification of metaphorical expressions in discourse for the purpose of corpus-

linguistic research. Another possible benefit of such a taxonomy is that it may

help the analyst to identify metaphors in the first place. It is possible to create a

schema for analysis in which a handful of questions have to be answered about

any sentence containing possible metaphorical expressions. Incorporating

classification into the business of identification itself in this manner helps to

sensitize the analyst to the presence of a wide variety of different kinds of

metaphors, a number of which might otherwise be missed.

This article will present a detailed discussion of the different patterns of

metaphorical expression exemplified above and discussed in context by Heywood

et al. (2002). We shall then continue with the categorization of these into a

taxonomy, the translation of this taxonomy into a schematic decision procedure

for metaphor classification, and finally the quantitative application of this

taxonomy to text analysis.

56

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

2 Units of discourse

If all patterns of metaphorical language were as clearly distinct as in the previous

examples, life would not be so difficult for the linguist interested in metaphor. In

fact many types of discourse do exhibit many instances of metaphorical language

patterning that are differentiated just as clearly and straightforwardly as in the

previously shown examples. However, if one’s aim is to establish a taxonomy for

the structure of metaphorical language which will be applicable in principle to

any genre or instance of discourse, then examples from more challenging types of

discourse, such as literary prose and poetry, also have to be dealt with. Some less

straightforward illustrations are offered below, from the Maitland (1990) and the

Rushdie (1995) texts discussed in more detail by Heywood et al. (2002), in order

to show that we have to introduce some further assumptions before we can

actually develop such a taxonomy.

(5)

It had been … a time when her body and her mind fitted together … tidily

and wholly.

(6)

Only in her anger could she drown out the dark shadow that pity and guilt

cast over her.

(7)

Abraham in a feverish rage spent hours crawling across the floor in search

of magic.

(8)

Their women, far from being grateful, turned on them, snarling, in late night

conversations telling them to shut up.

(9)

She grew moody and inward and sat behind her dustlines, besieged within

her own fortifications.

Although (5) through (9) are all complete sentences each containing more than

just two metaphorically used words, there are clear differences between them. For

instance, the most obvious distinction is probably the one between (9), which

involves clausal co-ordination, and the others, which do not. Intuitively there is a

lot to be said for treating the two co-ordinated clauses of (9) as independent units

of discourse. If this is done then ‘She grew moody and inward’ will count as one

linguistic expression with two metaphorically used words, grew and inward, and

will thereby become comparable to either (2) or (4) above, depending on the

perceived semantic relation between grow and inward.

Fortunately there is nothing either arbitrary or controversial in our isolating a

potentially sub-sentential unit of discourse, for the basic distinction employed by

many discourse analysts is precisely that between the sentence and the text span

or text unit, as in Mann and Thompson (1988). We take a text or T-unit to be a

semi-independent clause, a category that covers main clauses, matrix clauses plus

their embedded clauses, non-restrictive relative clauses and most adverbial

clauses. Appositions can also function as T-units. Such T-units form semantic

wholes in that they present a state of affairs as relatively integrated and separated.

Thus, despite their complexity, (5) to (7) each count as one T-unit, whereas (8)

and (9) do not. (See as follows for a display of the T-unit structure of [8] and [9].)

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

57

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

(8), with its verbless clause and its two non-finite adverbial clauses, counts as

four; and (9), with its two co-ordinated clauses, the second of which itself

contains a non-finite adverbial clause, counts as three. (5), (6) and (7), however,

each count as only one T-unit, though they do contain dependent clauses. This is

because in the case of (5) and (6) these are restrictive relative clauses introduced

by a time when in (5) and the dark shadow that in (6). Such clauses do not

possess the semantic independence required to function as a T-unit, since they

help to identify the primary referents of the noun phrases in which they occur. In

the case of (7), there is an adverbial adjunct that presents essential information

about how the hours were spent by the ‘he’ in question. Restrictive relative

clauses and embedded clauses, whether functioning as subjects, objects or

complements, and some finite adverbial clauses, lack the requisite semantic

independence to function as T-units. The two non-finite adverbial clauses in (8),

‘snarling’ and ‘in late night conversations telling them to shut up’, however, are

presented independently, marked off by commas; they are thus T-units. Each of

them has one metaphorically used word and so is comparable to (1) earlier. The

non-finite adverbial clause in (9), ‘besieged within her own fortifications’, has

two metaphorically used words and so is comparable to (2), if as seems

reasonable the two words are taken to denote in the same source domain (cf.

Heywood et al., 2002).

We display the T-unit constituency of (8) and (9) below in order to make things

completely clear:

(8)

Their women, far from being grateful, turned on them, snarling, in late night

conversations telling them to shut up.

8a. Their women turned on them

8b. far from being grateful

8c. snarling

8d. in late night conversations telling them to shut up

(9)

She grew moody and inward and sat behind her dustlines, besieged within

her own fortifications.

9a. She grew moody and inward

9b. and sat behind her dustlines

9c. besieged within her own fortifications

We have now specified a surface linguistic unit of discourse, the T-unit, that

should allow a range of quantifiable comparisons to be made at the level of the

linguistic expression between different genres and instances of discourse

containing metaphorical language. The level of the linguistic expression is

however only one of our three analytic levels. Although one may for a whole

range of purposes want to produce quantifiable generalizations at this level, by

itself it is relatively opaque. It has to be related to its potential role in the

construction of metaphorical mappings if it is to be of real interest to the analyst

aware of the conceptual dimensions of metaphor. However, as we saw in the first

58

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

two articles of this issue, we cannot move straight from linguistic expressions to

metaphorical mappings. We also need to work with the intermediate level of the

proposition. This becomes immediately clear when we display T-unit structures as

we have done previously. For, although each of the T-units shown earlier

expresses at least one main proposition, when the clauses involved are elliptical or

reduced, as they often are, only propositional analysis can make the underlying

propositional structure of predicate and argument(s) explicit. To spell this out by

means of an example, here is the propositional analysis of (8):

(10) S8A P1

(TURN WOMEN)

P2

(ON P1 MEN)

P3

(POSSESS MEN WOMEN)

S8B P1

(FAR-FROM P2)

P2

(MOD WOMEN GRATEFUL)

S8C P1

(SNARL WOMEN)

S8D P1

(TELL WOMEN P3)

P2

(TO P1 MEN)

P3

(HAVE-TO P4)

P4

(SHUT-UP MEN)

P5

(TIME P1 CONVERSATIONS)

P6

(MOD CONVERSATIONS LATE-NIGHT)

We now have a list of T-units of equal value which will facilitate the examination

and comparison of metaphorical structures across T-units within and between

sentences, together with a propositional analysis of these T-units. Lists of T-units

could form the input for an analysis of overall text structure in the fashion of

Rhetorical Structure Theory (Mann and Thompson, 1988, 1992), so that local

propositional analysis could be complemented by global coherence relation

analysis. The latter may be of importance when one wants to examine series of

metaphors across extended stretches of text.

3 Patterns of metaphorical structure

Now that we have established which units of linguistic expression may be

compared to each other when it comes to metaphorical structure, we can look at

the distinct patterns exhibited by these units. There is of course considerable

formal linguistic variation across T-units, as can be seen from (8). This means that

there is also considerable variation in their propositional structure, as can be seen

from (10). What unifies this variation in formal and propositional structure is the

fact that each T-unit is, by virtue of its relative semantic integrity, a distinct unit of

discourse that can be separately analysed and classified with regard to its

metaphorical properties.

Let us now re-examine (1) and the instances from (5) through (9) that can be

compared to it:

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

59

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

(1)

Rachel seemed able to absorb everything that Phoebe tried.

(8)

Their women turned on them

far from being grateful

snarling

Three of the above four T-units contains a single metaphorically used word. (We

are ignoring the complexities raised by the potential metaphoricity of on in (8a)

and far in (8b) for ease of exposition.) Each of these words in turn expresses a

single element of propositional structure, either a predicate or an argument. (We

shall in future use the phrase ‘semantic item’ to refer neutrally to either a

propositional argument or predicate.) In fact in this case all three semantic items

are two-place predicates (see 10 shown earlier).

There is in principle no limit to the number of propositions a T-unit may

express, no limit, that is, to its propositional complexity. Propositional complexity

when present is due to the presence of various kinds of subordinate proposition.

Yet for all its grammatical and propositional complexity, (1) is from the point of

view of its metaphorical structure very simple. Its single metaphorical word

expresses a single semantic item, this item just happening to be part of an

embedded proposition. The same is true of (8a) and (8c). In each case a single

metaphorical word expresses a single semantic item in the underlying

propositional structure. The presence of a single metaphorical word signals the

presence of an underlying metaphorical proposition, which provides in turn the

basis for constructing a cross-domain mapping, as may be seen by following the

five-step procedure proposed by Steen (1999). The proposition is able to do this

because the semantic item that the metaphorical word expresses relates to the

source domain of the potential cross-domain mapping.

We can now go on to complicate this picture in order to arrive at a taxonomy

for metaphor that is based on propositional structure. We will deal first with two

aspects that we term multiple metaphor and complex metaphor. Examples (2) and

(9) below exemplify multiple metaphor, while (3) and (5) exemplify complex

metaphor.

(2)

He had set his mark on them.

(9)

She grew moody and inward and sat behind her dustlines, besieged within

her own fortifications.

She grew moody and inward

and sat behind her dustlines

besieged within her own fortifications

(3)

Phoebe … asked herself with a sudden rush of nostalgia.

(5)

It had been … a time when her body and her mind fitted together … tidily

and wholly.

(2), (9a), (9b) and (9c) each contain metaphorical words signalling two different

semantic items in the underlying metaphorical proposition.

60

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

(11)

S2

P1

(SET JIM MARK)

P2

(ON P1 WOMEN)

P3

(POSSESS JIM MARK)

S9b

P1

(SIT-BEHIND FLORY DUSTLINES)

P2

(POSSESS FLORY DUSTLINES)

The underlying metaphorical proposition has at least two semantic items that

relate to the potential metaphorical source domain. This is what makes multiple

metaphors multiple.

(3) and (5) above are obviously different from (2) and (9). Although they too

each contain more than one metaphorical word, the total reaching four in (5), in

both cases these metaphorical words involve two different propositions, one

superordinate and the other subordinate and dependent on a semantic item in the

superordinate proposition. In (3) this item is an argument and in (5) it is a

predicate: see S3 P2 and P3 and S5 P3, P4 and P5 in (12):

(12) S3

P1

(ASK PHOEBE PHOEBE)

P2

(WITH P1 RUSH)

P3

(MOD RUSH SUDDEN)

P4

(OF RUSH NOSTALGIA)

S5

P1

(TIME P2)

P3

(FIT-TOGETHER BODY-AND-MIND)

P4

(MOD P3 TIDILY)

P5

(MOD P3 WHOLLY)

In terms of the linguistic surface, what is at issue is the modification of a head-

word, whether noun, verb or whatever, by one or more modifiers, whether

adjective, adverb or whatever.

We can now precisely define complex metaphor. (3) and (5) and other T-units

like them exhibit complex metaphor because they contain at least one semantic

item relating to a potential source domain occurring in a downgraded proposition

that is not co-referential with the semantic item on which that downgraded

proposition is dependent, and the semantic item on which the downgraded

proposition is dependent also itself relates to the potential source domain. Thus in

the qualifying downgraded proposition S3 P3 in (12) there are two metaphorical

arguments one of which is co-referential with the argument RUSH in the

proposition S3 P2, which is itself metaphorical. In the modifying downgraded

propositions S5 P4 and S5 P5 in (12) there is a single metaphorical argument in

each downgraded proposition, and the predicate of the superordinate proposition

S5 P3 on which S5 P4 and S5 P5 are dependent is also metaphorical. Thus, while

multiple metaphor extends the realization of a metaphor across a main

proposition, complex metaphor extends it within a proposition that is itself

dependent on a metaphorical semantic item within that main proposition.

The two remaining categories that we will incorporate into our taxonomy,

those of mixed and extended metaphor, are more familiar. It is however important

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

61

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

to show how they fit into our analytic system. A mixed metaphor in our definition

is present if within one metaphorical proposition, whether main, embedded or

downgraded, or in two metaphorical propositions one of which is superordinate to

the other that is itself downgraded and dependent on an item of the superordinate

proposition, there are two or more semantic items which relate to two or more

different potential source domains. This is what we have in (4), of which the

propositional analysis follows:

(13) S4

P1

(REF THAT STUFF)

P2

(OF STUFF MELODRAMA)

In S4 P2 the two arguments relate to the two different potential source domains of

‘physical substance’ and ‘drama’. Since the mixed metaphor is realized in a

downgraded proposition which is dependent on a co-referential argument in S4

P1, this metaphor is complex as well as mixed. In fact in the nature of the case a

mixed metaphor must always be either a complex or a multiple metaphor, for the

simplest kind of metaphor can with its single metaphorical word denote only in

one single potential source domain.

We can see from this that the analytic level of the proposition is vital for

establishing a taxonomy of metaphor. It enables us to see that the category of

mixed metaphor cross-cuts with other metaphorical categories, those namely of

multiple and complex metaphor. Yet of course at this stage the level of the cross-

domain mapping has also become crucial, for one can only judge mixed metaphor

to be present if one judges that there is more than one cross-domain mapping

present inside one unit.

The role of the cross-domain mapping also plays a necessary part in the

definition of extended metaphor. In our procedure it is a necessary condition of

extended metaphor being present that two or more successive metaphorical T-

units are judged to realize the same cross-domain mapping. This does not

however furnish a complete definition of extended metaphor since this condition

while being necessary is not sufficient, but space forbids a further explication of

our concept of extended metaphor.

4 Towards a taxonomy

To notice patterns of metaphorical structure is one thing, but to integrate them

into a proper taxonomy for metaphor is another. We have now provisionally

isolated a number of aspects of metaphor, but these do not seem to exclude one

other. They are potentially cross-cutting. A striking example is provided by (6),

which is repeated below for the sake of convenience.

(6)

Only in her anger could she drown out the dark shadow that pity and guilt

cast over her.

It is hopefully clear by now that the co-presence of drown out and shadow in one

62

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

proposition makes for both multiple and mixed metaphor. However, shadow is

also modified by dark, signalling the presence of a metaphorical downgraded

proposition dependent on the metaphorical argument expressed by shadow, which

entails complexity. (We shall temporarily leave aside the restrictive relative clause

following shadow, which contains yet a further metaphorical item, cast.) As a

result of this, this T-unit simultaneously exhibits mixed, multiple and complex

metaphor. We need to establish a form of taxonomy that recognizes our categories

of metaphor and allows them to cross-cut. We will in this section of our article

concentrate first upon the categories other than extended metaphor, then deal with

extended metaphor, and finally present our taxonomy in what is effectively a

decision procedure for metaphor classification.

The basic idea that we work with is that a T-unit consists of a main proposition

which may display various degrees of propositional complexity. Multiple

metaphor arises when a proposition contains more than one metaphorical

semantic item, as with (2) and (9a), (9b) and (9c) earlier. Complex metaphor

arises when a metaphorical item of a proposition is further developed by a

downgraded proposition which contains one or more novel metaphorical items, as

in (3) and (5). Mixed metaphor arises when multiple or complex metaphor

contains metaphorical items which may be derived from more than one source

domain, as in (4) and (6). The fact that one can have multiple and complex

metaphor at the same time is thus seen to be not at all surprising. It is simply a

consequence of the fact that if you have two or more metaphorical semantic items

in one proposition then one or more of these items may have a metaphorical

downgraded proposition dependent on it. To treat mixedness as a third variable,

one independent of the previous two variables as they are of each other, also

makes sense. It is a semantic variable that has to do with what source domains the

metaphorical items in the propositional analysis relate to, and this is an issue that

is independent of the structural properties of these items which make them either

multiple or complex metaphors. In other words, it is not redundant to say that the

combination of drown out and shadow is both multiple and mixed, for multiple

metaphor does not have to be mixed and mixed metaphor does not have to be

multiple – it may also be complex. Nor is it redundant to say that dark shadow is

complex and not mixed, for complex metaphor may be mixed and mixed

metaphor need not be complex – it may also be multiple.

The three variables of multiple, complex and mixed metaphor hence provide

the basis for three distinct types of observations about the conceptual structure of

metaphor when it is analysed by means of propositionalization. It is important to

notice that the variables are labelled by the marked terms of their measuring

scales: there is also metaphor which is not multiple, not complex and not mixed.

It is convenient to coin terms for these categories of metaphor, too, so that a

metaphor may always be described by a positive term. From now on, we will

speak of singular as opposed to multiple, simple as opposed to complex, and pure

as opposed to mixed metaphor.

All three categories dealt with earlier apply to the propositional structure of

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

63

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

metaphor within T-units. Some metaphors however may extend across T-units. A

candidate for extended metaphor would be ‘their women turned on them,

snarling’ in (8), where the metaphorical image of a dog turning on a human is

further elaborated in the next T-unit by means of ‘snarling’. When a metaphor is

not continued in the next T-unit, it may be called restricted.

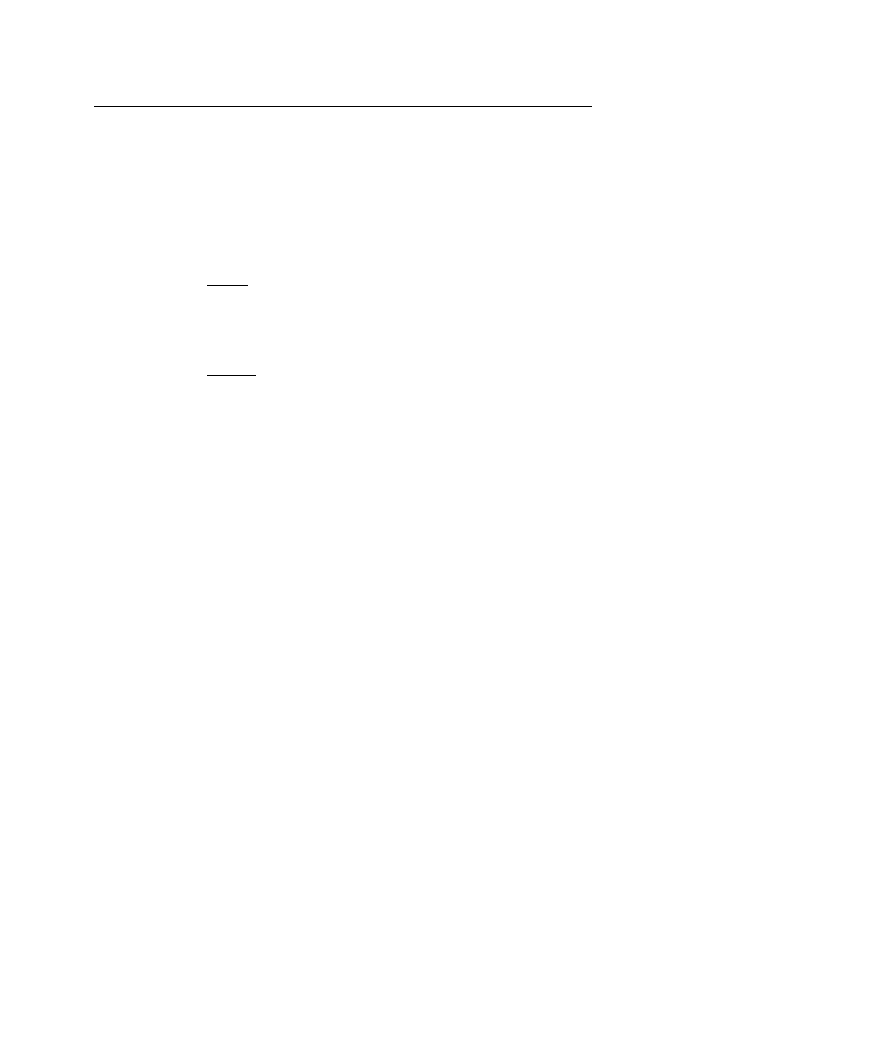

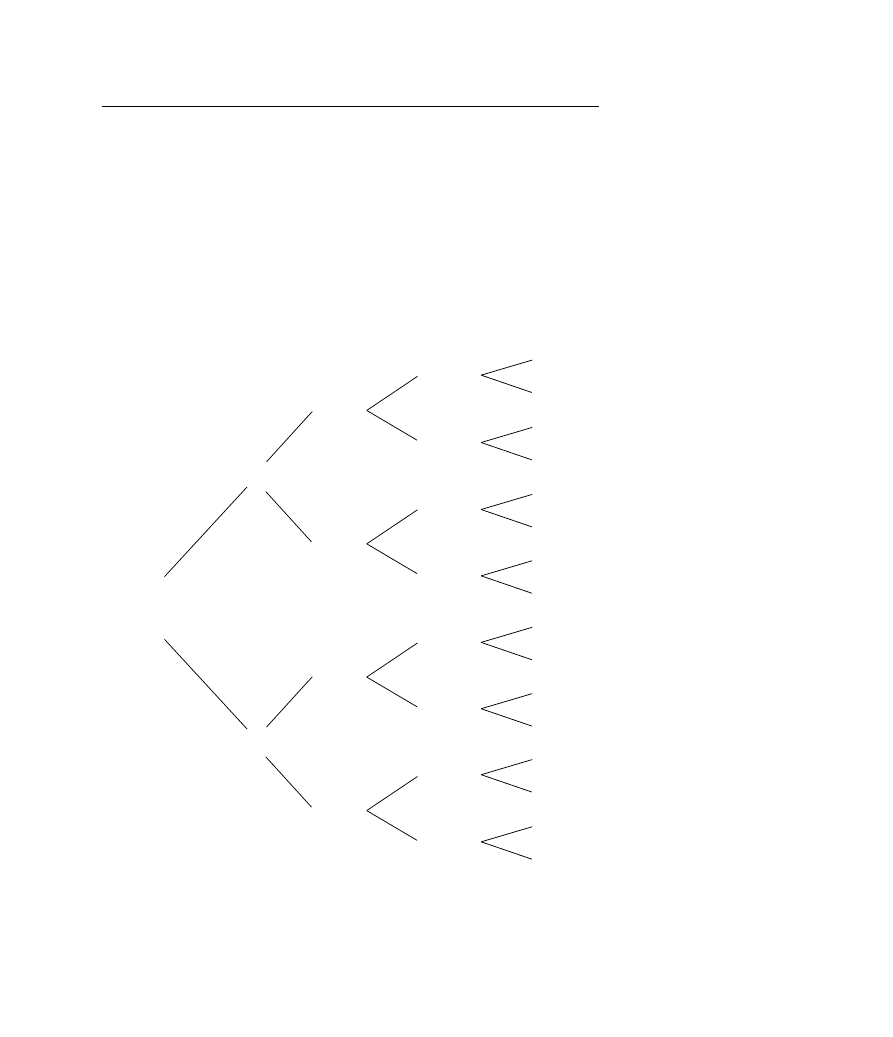

A schematic representation of our taxonomy would be as follows (see Figure

1). For any T-unit containing one or more metaphorically used words, one may

decide whether the metaphorical mapping is continued in the next T-unit or not

(extended or restricted). Whatever the answer to this question, one may then

proceed to examine whether the main metaphorical proposition expressed by the

T-unit contains only one or more than one metaphorical semantic item (multiple

or singular). Whatever the answer to this question, one may then continue to ask

64

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

Figure 1 Taxonomy of metaphorical mappings within T-units

Pure

*

Pure

Mixed

Pure

Mixed

Pure

Mixed

Pure

*

Pure

Mixed

Pure

Mixed

Pure

Mixed

Simple

Complex

Simple

Complex

Simple

Complex

Simple

Complex

Singular

Multiple

Singular

Multiple

Restricted

Extended

T-unit containing

metaphorically used

concept(s)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

whether the main metaphorical proposition has a metaphorical item with a

downgraded proposition dependent on it that itself contains at least one

metaphorical semantic item (complex or simple). Finally, if the answer to either

or both of questions 2 and 3 has been positive, then it has to be decided whether

the complex and/or multiple metaphorical mapping is pure or mixed. There are

only two out of 16 possible combinations of values of our four basic variables

which are logically impossible: one cannot have mixed metaphor in the case of

the combination of simple and singular metaphor, be it restricted or extended.

5 The unit of metaphor, or the problem of quantification

The phenomena of complex, multiple, mixed and extended metaphor may be

intuitively recognized and related to the structure of the propositional analysis of

T-units, but this does not yet offer us a precise enough instrument for the exact

description and measurement or quantification of metaphor in discourse. There

are several ways in which metaphors may be counted, and the four metaphor

properties that we have distinguished may be related to these various levels of

metaphor measurement with more or less felicity.

For instance, when we return to the complicated example of (6), there are

several problems to be noticed:

(6)

Only in her anger could she drown out the dark shadow that pity and guilt

cast over her.

T-unit (6) is not merely restricted, complex and mixed, but also:

(1)

its underlying main proposition contains two, and only two, metaphorically

used semantic items and that these are the predicate expressed by drown out

and the argument expressed by shadow (multiple metaphor property);

(2)

only one of its semantic items, the argument expressed by shadow, has a

downgraded metaphorical proposition dependent on it (complex metaphor

property);

(3)

shadow in fact has two, and only two, downgraded metaphorical

propositions dependent on it, that expressed by the adjective dark and that

expressed by the relative clause ‘that pity and guilt cast over her’ (complex

metaphor property);

(4)

the metaphorically used items are related to three source domains: the

predicate expressed by drown out is related to the source domain of liquids;

the complex structure of the argument expressed by shadow and the

downgraded propositions expressed by dark are related to the source

domain of light; and the term cast is related to the domain of movement

(mixed metaphor property).

However, it should be observed that for some research purposes it may be

convenient to ignore the additional details and label T-units for any incidence of

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

65

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

any of the marked values of the variables we have discussed until now. As a

result, (6) would be described as exhibiting restricted, complex, multiple and

mixed metaphor. This would be a relatively gross level of measurement if it is

compared with some form of counting metaphors based upon a full propositional

analysis, but it might be useful and give a speedy answer to some research

questions about the metaphorical nature of T-units as T-units in discourse.

Another alternative is suggested by the propositional procedure we have taken

to metaphor identification and analysis. This alternative approach would attempt

to tag propositions rather than T-units for the variables of multiple, complex,

mixed and extended metaphor. If this were successful, it would be a method for

classifying metaphorical ideas, operationally defined as propositions containing

metaphorically used concepts, according to their structure and content along the

lines suggested above. Thus, let us assume that the propositional structure of the

bulk of (6) is (14):

(14) P1

(POSSIBILITY P2)

P2

(DROWN-OUT PHOEBE SHADOW)

P3

(IN P2 ANGER)

P4

(MOD P3 ONLY)

P5

(POSSESS PHOEBE ANGER)

P6

(MOD SHADOW DARK)

According to our previous analyses, P2 would present a metaphorical proposition

that is restricted (it is not continued in the next T-unit), complex because one of

the metaphorical items is further modified (SHADOW, by DARK in P6), multiple

(DROWN-OUT plus SHADOW) and mixed (idem). The analysis of P6 as an

independent metaphorical idea unit, however, would seem less easy to solve.

According to the semantic spirit of our procedure, it is not multiple itself,

although it does look as if it is. It is not complex itself, either, but it is a part of a

complex metaphor, because of its relation to P2. And it is possible to say that it is

not mixed but pure, even though it does not sit easily in the categories of complex

and multiple metaphor.

A similar story could be told about counting metaphors as words or their

associated concepts. One could then adopt the convention of speaking of

metaphorically used concepts which participate in complex, multiple or mixed

metaphors, however these are defined, as propositions, T-units, or in yet another

way. This operational definition has been used by Steen (submitted) in a study of

the relation between metaphor recognition and metaphor properties. Important

parts of the variance occurring in the underlining data of metaphorically used

words turned out to be predictable by a handful of structural variables, including

the participation of the metaphorically used words in multiple metaphor. Yet one

other way of defining the unit of metaphor will be described later, but the point of

the present paragraphs has been to emphasize that it is not the only and not ‘the’

correct way to quantify metaphor.

Apart from looking at metaphors as concepts, propositions or T-units, which

66

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

are three basic and general levels of the conceptual structure of any analysis of

discourse, we may also define metaphors as conceptual mappings that cut across

these levels of discourse organization. This is the abstract conceptual approach

that we have referred to in the second article of this special issue (Steen, 2002),

and it is the method used by most cognitive linguists, who follow Lakoff and his

associates. In metaphor as a conceptual mapping, one only needs to assume the

existence of two independent conceptual domains, and it is an empirical issue

how many of the abstract conceptual correspondences are realized in a discourse

by means of metaphorically used words.

Probably the grossest quantitative question that can be asked of a text with

regard to metaphor is how many metaphors it contains. As can be seen from the

above, there is no single automatic answer to this question. Is one going to count

metaphorical concepts, metaphorical propositions, metaphorical T-units or

metaphorical mappings? Clearly, the answer to this question will depend upon the

interests of the analyst on any given occasion. Perhaps also on some occasions the

nature of the text involved might make one choice seem particularly appropriate.

But there can be no single absolute answer to the question of what to count as the

unit of metaphor.

The option for the unit of metaphor to be counted in a text that we have

adopted for illustration in this article is the number of cross-domain mappings.

This can be determined as follows. Every metaphorical T-unit which is neither

mixed nor extended will signal one such mapping, and so will count as one. Every

metaphorical T-unit that is mixed will have assigned to it the number of the source

domains which it can potentially activate. Any sequence of T-units which is

extended will count as one, no matter how many members it may have.

6 Sketch for an application

There is no space here for an exhaustive application of our procedure to a text or,

more interestingly, to a set of texts. However, it seems worthwhile to give a

relatively informal account of its quantitative application to the two texts we have

worked on so far, the excerpts from Sara Maitland’s Three Times Table and

Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh taken from the Lancaster University

Speech and Thought Presentation Corpus (see Heywood et al., 2002 for further

details). Since the Maitland text is a piece of popular fiction and the Rushdie a

piece of serious ‘literary’ fiction one could expect there to be differences between

the metaphorical patterning of the two texts, and in fact our procedure does

indeed indicate striking differences between them.

The Maitland text is approximately 2420 words long and, using our option of

defining the number of metaphors as the number of cross-domain mappings, it

contains 181 metaphors. The Rushdie is approximately 2156 words and contains

144 metaphors. This gives a metaphor/word ratio of 7.5 percent for the Maitland

and 6.7 percent for the Rushdie. A chi-square test shows that there is no

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

67

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

significant relation between the variables of number of words and number of

metaphorical mappings (X

2

(1)

= 0.85, n.s.). A mere counting of the numbers of

metaphors does not therefore reveal much in the way of difference between the

two texts.

When, however, we apply our taxonomy to the two texts, we obtain the

following findings. Although in both texts a large majority of the metaphors have

completely ‘negative’ values for our four categories, that is, they are restricted,

singular, simple and pure, Rushdie has a somewhat smaller proportion than

Maitland. Of Maitland’s metaphors, 70–75 percent are restricted, singular, simple

and pure, while the figure for Rushdie is 65.7 percent. However, this difference is

not statistically reliable (X

2

(1)

= 0.63, n.s.).

When one begins to look in detail at the nature of the metaphors in the two

texts that are multiple, complex or mixed, or some combination of these, one

remarkable difference is revealed. Of Rushdie’s metaphors, 17.4 percent are

multiple, while the figure for Maitland is 7.1 percent; this difference is

statistically reliable (X

2

(1)

= 7.09, p <0.01). It is probably also worth noting that

while all but one of Maitland’s multiple metaphors have only two metaphorical

semantic items, three of Rushdie’s have three. The ‘triple/double’ ratio for

Maitland is 8.3 percent while that for Rushdie is 13.6 percent. The differences

with regard to complex and mixed metaphor taken in isolation are less important,

though Rushdie does score higher on both these categories: 4.7 percent of

Maitland’s metaphors are complex and 7.7 percent are mixed, while 6.3 percent of

Rushdie’s are complex and 10.4 percent are mixed. However, there are no

statistically reliable relations here.

As already pointed out, one metaphorically used word may be classified from

more than one perspective. For instance, it is worth noting that we find in Rushdie

three instances of mixed metaphor combined with an additional independent

multiple or complex metaphor, while there is only one example of this, the

already cited (6), in Maitland. An example of Rushdie’s combination of mixed

metaphor with one or more independent complex or multiple metaphors where

there is a more obvious surface linguistic, as well as underlying semantic,

complexity is T-unit (15):

(15) which had managed by an act of will to wrench itself free of its fixed orbit

This is a non-restrictive relative clause modifying the noun body in ‘a heavenly

body’:

(16) P1

(MANAGE BODY P4)

P2

(BY P1 ACT)

P3

(OF ACT WILL)

P4

(WRENCH BODY P5)

P5

(MOD BODY FREE)

P6

(OF FREE ORBIT)

P7

(MOD ORBIT FIXED)

68

C

RISP ET AL

.

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

The combination of P1, P2 and P3 produces a complex metaphor with two

downgraded propositions. P4 gives rise to a multiple metaphor with two

metaphorical semantic items, the predicate WRENCH and the embedded

proposition P5. The combination of P5, P6 and P7 again gives rise to a complex

metaphor with two downgraded propositions. The T-unit as a whole is a mixed

metaphor drawing on three, and not just two, source domains, those of handed

action, concrete astronomical reality and abstract geometry, an orbit being an

abstract and not a concrete entity. There is nothing like this in the Maitland text. It

thus seems that our taxonomic model together with the method of propositional

analysis that underlies it is sensitive to differences of metaphorical patterning in

the two texts.

Acknowledgement

The third author wishes to thank the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the British

Council for travel grant BR 30–539, which facilitated preparation of this article.

References

Crisp, P. (2002) ‘Metaphorical Propositions: A Rationale’, Language and Literature 11(1): 7–16.

Heywood, J., Semino, E. and Short, M. (2002) ‘Linguistic Metaphor Identification in Two Extracts

from Novels’, Language and Literature 11(1): 35–54.

Maitland, S. (1990) Three Times Table. London: Chatto and Windus.

Mann, W.C. and Thompson, S.A. (1988) ‘Rhetorical Structure Theory: Toward a Functional Theory of

Text Organization’, Text 8: 243–81.

Mann, W.C. and Thompson, S.A. (eds) (1992) Discourse Descriptions: Diverse Analyses of a Fund-

raising Text. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rushdie, S. (1995) The Moor’s Last Sigh. London: Jonathan Cape.

Steen, G.J. (1999) ‘From Linguistic to Conceptual Metaphor in Five Steps’, in R.W. Gibbs Jr and G.J.

Steen (eds) Metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics, pp. 57–77. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Steen, G.J. (2002) ‘Towards a Procedure for Metaphor Identification’, Language and Literature 11(1):

17–33.

Steen, G.J. (submitted) ‘Metaphor Properties and Metaphor Recognition’, Journal of Pragmatics.

Addresses

Peter Crisp, Department of English, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, Hong

Kong. [email: b276780@mailserv.cuhk.edu.hk]

John Heywood, Department of Linguistics and Modern English Language, Lancaster University,

Lancaster LA1 4YT, UK. [email: j.heywood@lancaster.ac.uk]

Gerard Steen, Department of English, Free University, P.O. Box 7161, 1007 MC Amsterdam, The

Netherlands. [email: gj.steen@let.vu.nl]

M

ETAPHOR IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS

69

Language and Literature 2002 11(1)

© 2002 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Cultural Identity and Globalization Multimodal Metaphors in a Chinese Educational Advertisement Nin

Metaphor interpretation and emergence

Identifcation and Simultaneous Determination of Twelve Active

Metaphor, Relevance and the Emergent Property Issue

Am I Who I Say I Am Social Identities and Identification

Metaphor interpretation and emergence

Identity and the Young English Language Learner (E M Day)

Cruz Jansen Ethnic Identity and Racial Formations

Identification and fault diagnosis of a simulated model of an industrial gas turbine I6C

Cruz Jansen Ethnic Identity and Racial Formations

19657249 subaltern studies collective schizophrenic identity and confronted politics a revision

Generic Identity and Intertextuality

0415165733 Routledge Personal Identity and Self Consciousness May 1998

Akerlof Kranton Identity and the economics of organizations

identifying and discussing feelings 201

Variation in NSSI Identification and Features of Latent Classes in a College Population of Emerging

Susan B A Somers Willett The Cultural Politics of Slam Poetry, Race, Identity, and the Performance

Work motivation, organisational identification, and well being in call centre work

więcej podobnych podstron