Work motivation, organizational identification, and

well-being in call centre work

JU

¨ RGEN WEGGE

1

, ROLF VAN DICK

2

, GARY K. FISHER

2

,

CHRISTIANE WECKING

3

, & KAI MOLTZEN

4

1

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨t, Mu¨nchen, Germany;

2

Aston University, Birmingham, UK, and

Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universita¨t Frankfurt, Germany;

3

Universita¨t Dortmund, Germany; and

4

Philipps-Universita¨t Marburg, Germany

Abstract

Previous work has not considered the interplay of motivational forces linked to the task with those

linked to the social identity of employees. The aim of the present study is to combine these approaches.

Two studies with call centre agents (N

211, N 161) were conducted in which the relationships of

objective working conditions (e.g., inbound vs. outbound work), subjective measures of motivating

potential of work, and organizational identification were analysed. Job satisfaction, turnover intentions,

organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB), health complaints, and burnout were assessed as

indicators of the agents’ work motivation and well-being. In both studies it was found that objective

working conditions substantially correlated with subjective measures of work motivation. Moreover,

employees experiencing a high motivating potential at work reported more OCB, higher job

satisfaction, and less turnover intentions. As hypothesised, organizational identification was a further

independent predictor of job satisfaction, turnover intentions, OCB, and well-being. Highly

organizationally identified employees report higher work motivation and more well-being. Addition-

ally, interactions between the motivating potential and organizational identification were found.

However, all the results indicate that interventions seeking to enhance work motivation and well-being

in call centres should improve both the motivating potential of the job and organizational identification.

These two factors combined in an additive way across both studies.

Keywords: Call centre, work motivation, organizational identification, well-being, burnout, organiza-

tional citizenship behavior, work-related stress

Introduction

The main goal of the present study is to contribute to research in the area of stress among

call centre agents. More specifically, this paper focuses on two factors that should affect

work motivation and well-being: the motivating potential of the task and organizational

identification. Prior research has clearly documented that an appropriate work design

promotes employee satisfaction, motivation, and well-being. As call centres are a new

segment of the service industry, we examine whether the ‘‘old laws’’ apply to this kind of

work, too. A second purpose of this study is to investigate potential benefits of

Correspondence: Ju

¨ rgen Wegge, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨t Mu

¨ nchen (LMU), Department of Psychology,

Psychology of Excellence, Martiusstrasse 4, D-80802, Mu

¨ nchen, Germany. Tel: 498921809791. Fax:

498921804814. E-mail: wegge@psy.uni-muenchen.de

ISSN 0267-8373 print/ISSN 1464-5335 online # 2006 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/02678370600655553

Work & Stress, March 2006; 20(1): 60

/

83

organizational identification on work motivation and well-being in call centres. There are

only few studies that have examined the impact of organizational identification on well-

being. Thus, we seek to provide more evidence on this issue. Finally, this study investigates

whether and how motivational forces linked to the task combine with those forces linked to

the psychological attachment of employees towards their organization.

Call centres are a growing part of the service industry in many countries and a substantial

amount of call centre agent (customer service representative) jobs have been created in this

sector in recent years (Baumgartner, Good, & Udris, 2002; Holman, 2003; Moltzen & Van

Dick, 2002; Wegge, Van Dick, Fisher, West, & Dawson, 2006). Three percent of the US

working population and 1.3% of the European working population were employed in call

centres in 2002 (Deery, Iverson, & Walsh, 2002). In emergent markets, the call centre

sector is rapidly growing and it is estimated that soon there will be a workforce of 700,000 in

India (Shah & Bandi, 2003). The main task of call centre agents is to communicate with

customers via integrated telephone and computer solutions. Communication between

agents and customers serves various purposes, e.g., taking orders, giving information about

products, providing highly skilled IT services or legal advice, conducting consumer

research, advertising, and hard selling. Inbound agents receive calls from customers

whereas outbound agents dial up customers themselves.

A common stereotype regarding call centre work is that managing phone-based customer

interactions all the day is neither complicated nor demanding as most interactions are basic,

simple, and scripted. This stereotype, however, is not corroborated by recent research. On

the contrary, the majority of previous studies have shown (for a review, see Holman, 2003)

that the work of call centre agents is very demanding with respect to various aspects. In

order to do the job correctly, call centre agents have to perform several attention-

consuming, simultaneous subtasks such as controlling the call via the deployment of

sophisticated listening and questioning skills, operating a keyboard to input data into

computers, reading often detailed information from a visual display unit, and speaking to

customers. Furthermore, as many customers are subjected to long waiting times their

satisfaction is negatively affected and thus these tasks are often conducted under high time

pressure. Moreover, phone calls with customers are usually short (e.g., 2

/

5 minutes) and

therefore, a call centre agent often communicates with many different customers each day;

sometimes with about 100 customers during a typical 8 hour shift. Continuously keeping

track of to whom you are speaking and the frequent readjustment to new customers is a

further, non-trivial attention requirement. More significantly, call centre agents are usually

instructed to be friendly, enthusiastic, polite, and helpful to customers even if customers are

rude (which is not a rare event, see Grandey, Dickter, & Sin, 2004; Totterdell & Holman,

2003) and this induces further demands with respect to the volitional presentation of

emotions in opposition to those being actually felt, which is referred to as emotional

dissonance (e.g., Lewig & Dollard, 2003). As many call centres use monitoring procedures

such as test calls and recording of calls (Holman, 2002; Holman, Chissick, & Totterdell,

2002), violations of this norm will be easily detected. Recent research shows that the control

of one’s own emotions (e.g., by suppression, hiding, or overplaying emotions) can have

serious consequences. This form of emotion regulation consumes volitional energies

(Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998) and often leads to the development of

emotional exhaustion, a component of the burnout syndrome (for reviews of burnout and

emotional labor at work see Dormann & Zapf, 2004; Grandey, 2000; Payne & Cooper,

2001; Salovey, Detweiler, Steward, & Bedell, 2001; Schaufeli & Buunk, 2003; Zapf, 2002).

Thus, demands for emotion regulation at work can affect health negatively, especially if

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

61

intensive negative emotions are aroused or suppressed, and this was also found in call centre

work (Grandey et al., 2004; Isic, Dormann, & Zapf, 1999; Lewig & Dollard, 2003;

Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000; Totterdell & Holman, 2003; Wegge, van Dick, & Wecking,

2006; Zapf, Isic, Bechtoldt, & Blau, 2003).

Continuous attention to high volumes of differing customer demands, the regulation of

emotions, and conforming to organizational norms with respect to the display of positive

emotions can easily exceed the available resources of call centre agents. There are also some

aspects of call centre work, however, that are stressful because they disqualify the use of

available skills and resources. Most calls are based on a predetermined script that agents

have to follow strictly. Agents also have very little autonomy or control over their work

because they are not allowed to deviate from a predetermined message in order to meet

customer demands. Having to use the same communication script about hundred times a

day leads to feelings of monotony and boredom (Wieland & Timm, 2004) that might

accumulate over the course of the week (Richter, 2004). Boredom is sometimes also

induced by unnecessary waiting times that result from mismanaged call distribution or

unexpected low call volumes. Moreover, requirements for agents to be innovative,

proactive, or forward thinking are often low for these types of tasks and this typically also

yields lower work motivation and health problems. As several other common stressors (e.g.,

working in shifts, inconvenient postures due to computer work, high noise levels in large

offices) are also present in call centre work, it can be concluded that the work of agents is

neither simple nor undemanding. In support of this view, turnover rates in call centres are

very high. In a study of 14 call centres in Switzerland, for example, Baumgartner et al.

(2002) report an average turnover rate of 21% per annum.

The factors that make call centre work stressful are under extensive investigation (e.g.,

Dormann & Zijlstra, 2003; Holman, 2003). Very little research, however, has been

conducted with respect to important factors that might reduce strain and turnover in call

centres. Can traditional approaches to job design focusing on the tasks of employees also be

utilised to improve work motivation and well-being in call centres? As a major redesign of

the core tasks of call centre agents (having rather simple, often scripted phone calls with

customers) is almost impossible, some doubts may be raised. Furthermore, what other

factors, apart from designing core task features, might be successful in improving well-being

in such emotionally loaded environments? The purpose of the present study is to address

this issue. We draw upon the work by Hackman and Oldham (1980) and their Job

Characteristics Model (JCM). According to this model, job satisfaction, motivation, and

other outcomes are a function of five core characteristics of the job itself, mediated by

psychological states and moderated by variables such as knowledge and skills or the

individual’s need for growth. The five core job characteristics are skill variety, task identity,

meaningfulness of the task, autonomy, and feedback from the job itself (as opposed to

feedback by supervisors or others). These characteristics can be assessed with several items

for each dimension from the Job Diagnostic Survey, and a Motivating Potential Score

(MPS) can be calculated (Hackman & Oldham, 1975, 1980).

The first aim of the present study is to examine the relationship between objective job

characteristics (e.g., working on inbound vs. outbound tasks) and employees’ perceptions of

the motivating potentials of their jobs based on the JCM. The second aim is to investigate

whether the main proposition of this model (high MPS scores should correspond with high

work motivation and well-being) can also be corroborated in the restricted work of call

centre agents. Third, we want to examine the relationship of organizational identification

with work motivation and well-being of call centre agents. According to social identity

62

J. Wegge et al.

theory, a strong psychological attachment of employees to their organization should

typically improve work motivation (Van Knippenberg, 2000). Moreover, recent findings

show that the appraisal of stressors and successful coping with stressors are also influenced

by social identity (Haslam, 2004). Feeling strong ties with the organization might therefore

reduce stress that is based on adhering to organizational norms such as being always friendly

to customers. Finally, this study seeks to investigate the relative importance of both factors

(motivating potential and organizational identification) and their potential interactions with

regard to work motivation and well-being.

Job design in call centres

As work in call centres is often characterised by Tayloristic, restricted working conditions

(low autonomy, low task variety, short task cycles, etc., see Holman, 2003; Zapf et al.,

2003), several researchers have recommended the use of traditional strategies of job

enrichment and job enlargement (Hackman & Oldham, 1980) to improve work motivation

in call centres (e.g., Grebner, Semmer, Faso, Gut, Ka¨lin, & Elfering, 2003; Richter, 2004;

Wieland & Timm, 2004). The question, however, is whether it would be possible to

increase the motivating potential of work (e.g., task variety, task significance, task

completeness) given the strongly restricted nature of the work setting in which the basic

nature of the task itself cannot be changed. Previous research has shown that call centre

agents responsible for outbound calls report less time pressure, more autonomy, and lower

strain than agents working only inbound (e.g., Isic et al., 1999). Moreover, it can be

expected that employees also value getting access to training and development programs

(Shah & Bandi, 2003). Having access to vocational training should be perceived as a real

enrichment and benefit because many agents often receive little training before they start

their job. In a similar vein, a third objective aspect of working conditions that should be

linked with perceived motivating potentials of work is the type of employment contract.

According to assumptions from social exchange theory and research on psychological

contracts (e.g., Rousseau, 1998), employees with a full-time contract expect and often have

more positive exchange relationships with an organization than employees with a part-time

contract. Especially in organizations with a high turnover rate, having a full-time contract is

also probably perceived as an indication of long-term job security and this should improve,

for example, the organizational citizenship behavior of employees (Van Dyne & Ang, 1998).

Of course, employees with full-time contracts might also be responsible for several subtasks

(products), so that they experience higher task variety and task significance than employees

with part time contracts. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1. Objective working conditions in call centres, especially (a) inbound vs.

outbound tasks, (b) regular vocational training, and (c) part time vs. full-time contract

correlate with subjective measures of motivating potentials of work (expressed as MPS).

Higher values of MPS should be observed for employees with outbound tasks, more

training on the job, and full-time contracts.

Many previous studies have documented that high motivating potentials have a positive

impact upon indicators of work motivation and well-being such as job satisfaction, turnover

intentions, absenteeism, and OCB (Fried & Ferris, 1987; Johns, 1997; Van Dick & Wagner,

2001). Thus, if variations in the motivating potential occur in call centre work (which has

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

63

not yet been examined), it can be expected that these relationships will also be found in this

type of work. This leads to:

Hypothesis 2a. In call centre work, work motivation (MPS) is positively correlated with (a)

job satisfaction, (b) OCB, and (c) well-being, and negatively correlated with (d) turnover

intentions.

Social identity, work motivation, and health

As a second main motivating factor predicting work-related attitudes and behaviors, the

focus is drawn to employees’ psychological attachment towards their organization. We will

draw upon social identity theory for our hypotheses. Social identity theory, developed by

Tajfel and Turner (1979, 1986), explains intergroup conflicts and hostility between groups

with different ethnic backgrounds. Basic assumptions of this theory are that: (1) individuals

are striving for positive self-esteem; (2) that one part of an individual’s self-concept, one’s

social identity as opposed to one’s personal identity, is based on membership in social

categories; and (3) that individuals strive for positive differentiation between those

categories of which they are a member, i.e., their in-groups, from other categories, or

outgroups. Empirical research has indeed corroborated these propositions and shown, for

instance, that individuals who highly identified with their groups reported more prejudice

toward outgroups but also a higher tendency to follow the group’s norms and rules, to

defend the group to outsiders, and to put in extra efforts in tasks that supported the group.

Recently, social identity theory has also been fruitfully adapted in organizational contexts

showing that employees’ organizational identification is positively related to work-related

attitudes and behaviors such as job satisfaction or extra-role behaviors (Van Knippenberg &

Van Schie, 2000; for an overview see Van Dick, 2004). Van Dick and Wagner (2002), for

instance, demonstrate in two samples of schoolteachers that variables of work motivation,

job satisfaction, and self-reported extra-role behaviors were predicted positively by

identification with the professional group. Riketta (2005) provided meta-analytical

evidence, based on approximately 100 studies, of substantial relationships between

identification and indicators of work motivation such as job satisfaction (r

.54), turnover

intentions (r

.48), and extra-role behavior (r .19) (see also Riketta & Van Dick,

2005).

Research on the relationship between organizational identification and variables of stress

and well-being, however, has not been extensive. Van Dick and Wagner (2002) found a

negative correlation between organizational identification and physical health complaints.

Consistent with this finding, Schaubroeck and Jones (2000) showed that high organiza-

tional identification might function as a buffer against organizational stressors because

perceived demands to present (pretended) positive emotions as part of the work role

correlated positively with physical symptoms only for those employees reporting low

organizational identification. In the same vein, Brotheridge and Lee (2003) found that role

identification correlated negatively with emotional dissonance and also negatively with

burnout in a sample of 238 workers from various fields (e.g., service/sales workers, office

workers, laborers). Moreover, Haslam, Jetten, O’Brien, and Jacobs (2004) could demon-

strate the usefulness of a social identity and self-categorisation perspective on the appraisal

of stress-related information. In their experimental research they found that information

that described a situation as more or less stressful was perceived as more reliable if it came

from an in-group member. Haslam (2004) has recently summarised this and other evidence

64

J. Wegge et al.

into a self-categorisation model of stress in which he outlines that a common identity can

provide not only the basis for a more self-protective (effective) perception of stress-related

information but also the foundation of social support and coping, leading to greater well-

being. To summarise, there is considerable evidence for positive effects of identification in

the workplace with respect to indicators of work motivation and there is preliminary

evidence that (organizational) identification also promotes well-being of employees.

Whether these relationships can be found in call centre work has not yet been investigated.

However, in line with existing evidence from other work contexts, we formulate:

Hypothesis 2b. In call centre work, organizational identification is positively correlated with

(a) job satisfaction, (b) OCB, (c) employee well-being, and negatively correlated with (d)

turnover intentions.

Relationship between job design and social identity

Theories of job design and theories of organizational identification focus on rather different

aspects of work that motivate people to invest more or less effort and persistence. The job

design approach considers task characteristics like task variety and task feedback as more or

less motivating whereas the social identity approach focuses on inter-group relations and

self-categorisation processes with respect to social categories. Therefore, it seems plausible

that these different forces are to a large extent independent of each other. People might like

the task they do (e.g., teaching school children) but do not like the organization in which

this happens (the school) because this organization, for example, is managed by an

incompetent head-teacher. In the same vein, employees can identify strongly with an

organization but not like their boring tasks or how their work is organized (e.g., routine

office work without any autonomy). Conceptualizing the motivational incentives linked to

task design and social relations as rather independent from each other, however, does not

imply that interactions between these factors are impossible. Interactions might be

observed, for example, because highly committed employees experience higher self-esteem

and this reduces the potential impact of organizational stressors (Pierce, Gardner, Dunham,

& Cummings, 1993). The findings from Van Dick and Wegge (2004) in a sample of bank

employees point to another possible reason for interactions between job design and

organizational identification. In this study, different levels of organizational identification

had no impact on turnover intentions if the motivating potential was perceived as high. If

the motivating potential was low, however, only employees with low organizational

identification reported high turnover intentions. Thus, organizational identification might

be more important for work motivation and well-being if job design is perceived as sub-

optimal. Work in call centres has a much lower motivating potential than office work in a

bank (e.g., Isic et al., 1999) and we can, therefore, expect that finding independent main

effects of both factors is plausible in this context. Given the lack of studies examining both

organizational identification and motivating potentials of work, our predictions are

somewhat exploratory. The existing evidence, however, supports the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2c. In call centre work, the relationships between motivating potentials of work

and organizational identification on the one hand, and work motivation (job-satisfaction,

OCB, turnover intentions) and well-being (health complaints, burnout) on the other are

additive in nature.

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

65

Relationship between identification and OCB

In this research, identification with organizations is considered to be an important

antecedent of behavior in organizations. With respect to OCB, however, there is also

evidence that organizational identification might function as a moderator variable. In a study

by Van Dyne and Ang (1998), differences in the relationship between commitment and

OCB have been analysed for permanent versus non-permanent, contingent workers. As

expected, those employees who have been employed on a contingent basis showed lower

commitment and OCB levels. Contingent workers, however, showed similar levels of OCB

to those of permanent workers if their commitment was high. Thus, only contingent

workers with low levels of commitment showed low extra effort. As contingent working

relations and part-time employment are widely observed phenomena in call centre work, a

final aim of this research is to replicate these findings for call centre employees. If this is

successful, the implication for practitioners would be very clear. Increasing the identifica-

tion of part time workers will pay considerable dividends. Taken together, this leads to:

Hypothesis 3a. In call centre work, part time employees engage in less OCB than regular

employees.

Hypothesis 3b. In call centre work, the relationship between identification and OCB is

stronger for part-time employees than for full-time employees.

We will test our hypotheses using a cross-sectional multi-sample approach. Study 1

provides an initial investigation, and Study 2 will seek to replicate and extend the findings.

Study 1

Sample and procedure

After getting approval from management and union representatives, standardised ques-

tionnaires were distributed in two call centres, comprising 305 customer service

representatives. Respondents filled out the questionnaires during business hours and

participation was both confidential and voluntary. Two hundred and eleven questionnaires

were returned (response rate 67%). Sixty-five percent of respondents were female, average

age was 27.8 years (SD

6.7 years), and mean professional experience was 1.1 years

(SD

2.5 years). A total of 169 call centre agents are working inbound, 37 mainly

outbound; 32% of respondents had full-time contracts, 68% were working part time.

Questionnaires

Participants had to evaluate all the following items using 6-point answering scales with

endpoints 1

‘‘is not at all correct’’ to 6 ‘‘totally correct.’’ The items were then averaged

within each scale, which can thus have a range between 1 and 6.

Information on organizational identification was obtained with an instrument in the form

of a table that has been shown to be a reliable and economical measure with regard to the

assessment of different forms of identification (Van Dick, Wagner, Stellmacher, & Christ,

2004). Six items within the table tapped organizational identification (e.g., ‘‘I identify with

my organization,’’ ‘‘Being a member of my organization is a reflection of who I am’’). These

items were averaged and provided a good reliability (

a .85).

66

J. Wegge et al.

Additionally, the questionnaire contained the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman &

Oldham, 1975) to measure employees’ perceptions of their job (motivating potential) and

their job satisfaction. Motivating potential was measured with 14 items assessing the job’s

significance, identity, variety, autonomy, and feedback from the task itself to obtain a MPS.

Following the recommendations of Fried and Ferris (1987) and Evans (1991) regarding

problems with multiplicative composite scores, we used an additive form of the MPS,

summing up the values of the five job characteristics (

a .82). Job satisfaction was measured

with six items (e.g., ‘‘Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with this job,’’ ‘‘I am generally

satisfied with the kind of work I do in this job,’’

a .83).

Participants were also asked to complete a scale assessing Organizational Citizenship

Behavior (OCB). This scale consisted of 10 items based on the operationalisation of the

construct devised by Organ (1997). Item examples are ‘‘I help orienting new colleagues,’’

‘‘If colleagues are feeling blue, I try to cheer them up’’ (

a .75).

Turnover intentions were assessed with three items (‘‘I frequently think of quitting,’’ ‘‘I

often study job offers in the daily press,’’ ‘‘A job with a similar salary in another company

would be an interesting alternative to my present job,’’

a .67).

Finally, participants were asked to indicate how often they participate in training activities

(from 0

‘‘never’’ to 4 ‘‘regularly’’).

Results (study 1)

Table I presents means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables. All scales are

sufficiently reliable.

Test of Hypothesis 1. Based on the zero-order correlations shown in Table I, it can be

concluded that all three parts of Hypothesis 1 are corroborated. Higher values of the

subjective motivating potential of work (MPS) were observed for employees with

outbound tasks (r

.16), more training activities (r .23), and full-time contracts

(r

.23).

Test of Hypothesis 2a. In order to test this hypothesis, we inspected zero-order correlations

between variables again (see Table I). In line with our expectations, all correlations are

significant in the expected direction: the correlation between motivating potential and job

satisfaction (r

.67), motivating potential and OCB (r .58), and motivating potential

and turnover intentions (r

.18).

Test of Hypothesis 2b. As expected, zero-order correlations between organizational

identification and indicators of work motivation and well-being of employees are also

significant in this sample. Employees who felt more attached to their organization were

more satisfied with their job (r

.51), engaged more in OCB at work (r .55), and were

less likely to leave the organization (r

.33).

Test of Hypothesis 2c. The similarity of findings for the motivating potential and

organizational identification is obvious. The two variables, however, are correlated only

moderately (r

.39). To examine whether these relationships are additive in nature, a

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

67

Table I. Means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and zero-order correlations (Study 1).

M

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1. Age

27.8

6.9

/

2. Gender

1

1.36 0.49

.06

/

3. In vs. outbound work

2

1.20 0.40

.15*

.08

/

4. Type of contract

3

1.70 0.47

.15*

.07

.03

/

5. Training

2.30 0.93

.13

.09

.09

.17*

/

6. Motivating potential (MPS)

3.78 0.80

.26**

.06

.16*

.23**

.23**

(.82)

7. Organizational identification

3.84 1.2

.15*

.12

.21**

.20**

.22**

.39**

(.85)

8. Job satisfaction

4.34 0.99

.12

.05

.04

.09

.13

.67**

.51**

(.83)

9. Organizational citizenship (OCB)

4.67 0.69

.19**

.05

.16*

.28**

.40**

.58**

.55**

.51**

(.75)

10. Turnover intention

2.59 1.3

.00

.13

.02

.04

.01

.18** .33** .48** .20** (.67)

* p B.05, ** p B.01.

Notes: n between 194 and 211 due to missing data. Cronbach’s alphas are on the diagonal,

1

female

1, male 2;

2

Inbound tasks

1,

outbound tasks

2,

3

part time

0, full-time 1.

68

J.

W

egg

e

et

al.

series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted (see Table II). In these

regressions, age and gender were included as demographic controls first. Next, both

standardised predictor variables were entered. In the third step, the standardised product-

term of both predictors was entered as a further variable to examine potential interactions.

This procedure follows the suggestions of Aiken and West (1991).

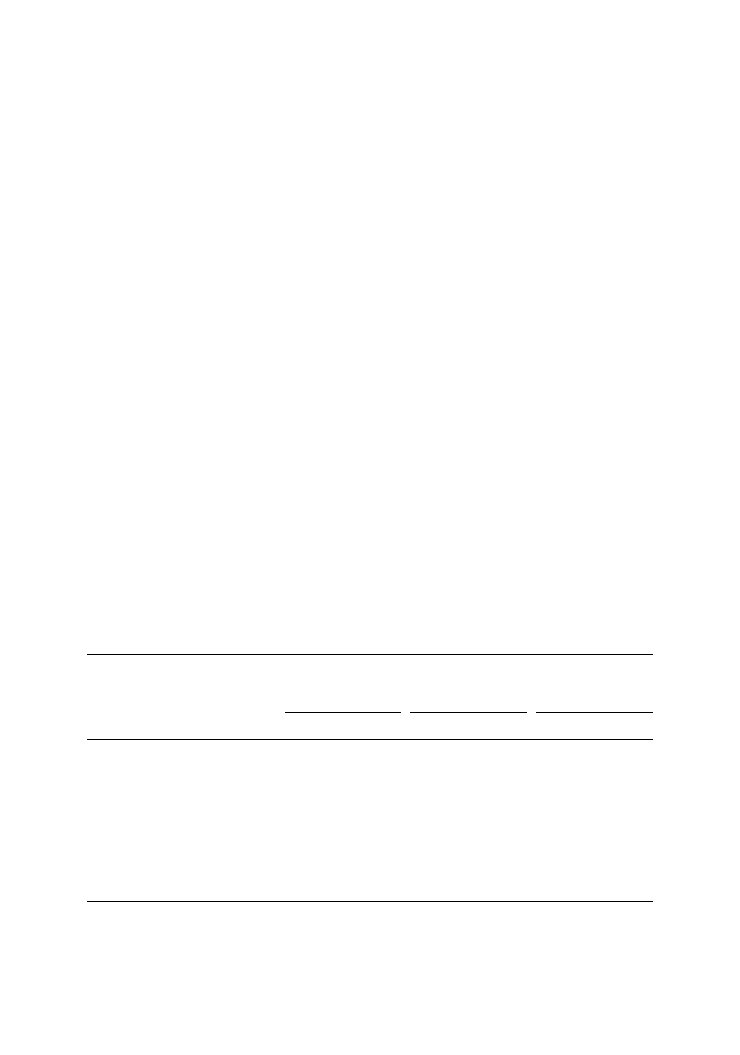

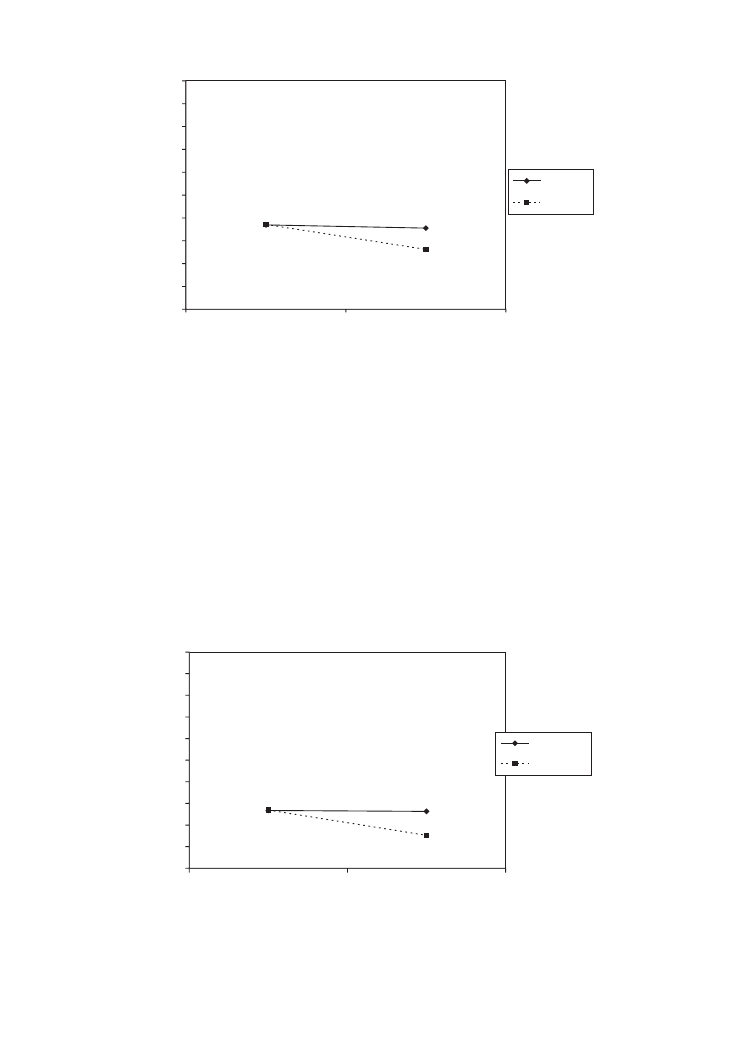

In support of Hypothesis 2c, we found that job satisfaction and OCB were associated

with both motivating potential and organizational identification in the expected direction.

Both variables had significant positive

b-values when included simultaneously in the

regression equation. Together, these variables explain a quite substantial amount of variance

of dependent variables (51% and 42%, respectively). For OCB, however, the interaction

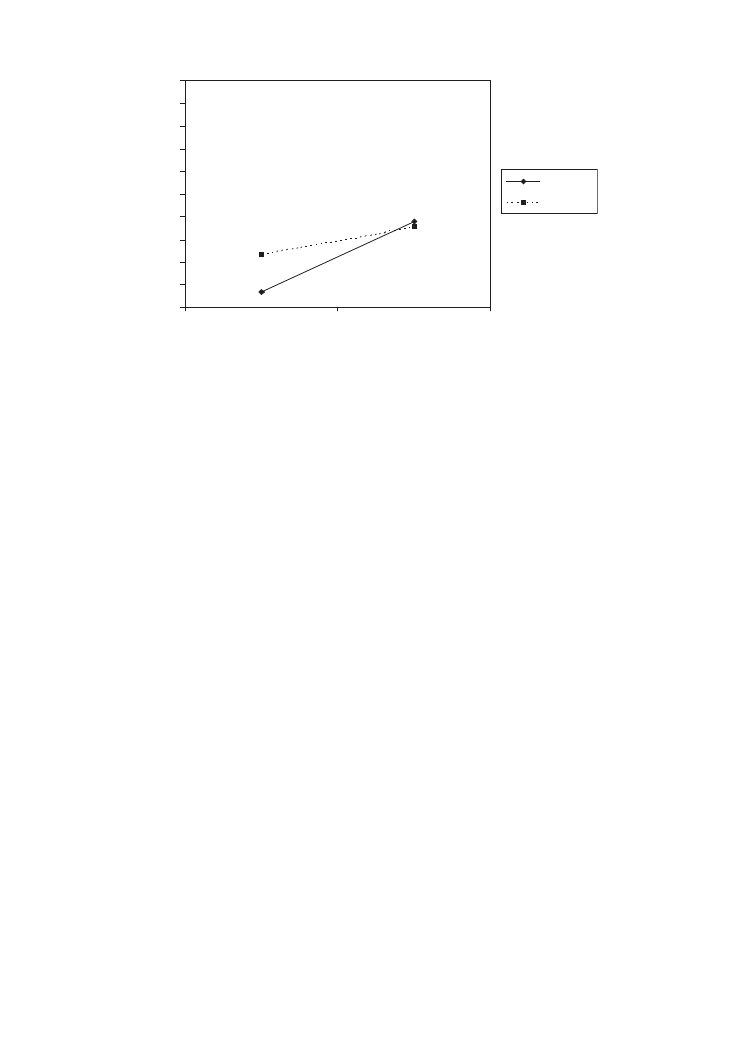

term was also significant. To examine the form of this interaction, we inserted cut-point

values of9one standard deviation from the mean of each variable (see Figure 1). This plot

reveals that the relationship between organizational identification and OCB was more

substantial for employees who perceived a low motivating potential of their job. Especially

under conditions of low motivating potential, organizational identification made a

difference with regard to OCB at work.

With respect to turnover intentions, Hypothesis 2c is not supported. As shown in Table

II, the only significant association occurs between turnover intentions and organizational

identification (

b

.31). Thus, taken together, the results give mixed evidence for

Hypothesis 2c, as the nature of the relationship between motivating potential and

organizational identification also depends on the nature of the criterion considered. For

job satisfaction and OCB, both predictors work in a rather additive way but for turnover

intentions only organizational identification is important.

Test of Hypothesis 3. According to Hypothesis 3a, part-time employees should engage in less

OCB than regular employees. This proposition is supported by the data (see Table I). The

corresponding correlation is significant (r

.28) indicating that call centre agents with a

full-time contract report more OCB than those with a part-time contract. Hypothesis 3b

suggested that the relationship between identification and OCB is stronger for part-time

Table II. Summary of hierarchical regression analyses (Study 1).

Job satisfaction

Organizational

Citizenship Behavior

(OCB)

Turnover intention

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

Age

.00

.01

.15*

.00

.01

.20**

.00

.01

.01

Gender

.00

.14

.03

.00

.10

.01

.27

.19

.10

Step I: R

2

.02

.04*

.01

Motivating potential (MPS)

.57

.06

.57**

.29

.04

.42**

.13

.10

.10

Organizational identification

.29

.05

.30**

.26

.04

.39**

.41

.10

.31**

Step II: R

2

/

DR

2

.53*/.51**

.46**/.42**

.14**/.13**

Motivating potential (MPS)

.56

.06

.57**

.29

.04

.42**

.14

.10

.10

Organizational identification

.29

.05

.30**

.26

.04

.39**

.40

.10

.31**

MPS

Organizational identification .00

.05

.06

.11

.04

.17** .14

.09

.11

Step III: R

2

/

DR

2

.53**/.00

.49**/.03**

.15**/.01

* p B.05, ** p B.01

Notes: n

191 for job satisfaction, n 193 for OCB, n 193 for turnover intention.

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

69

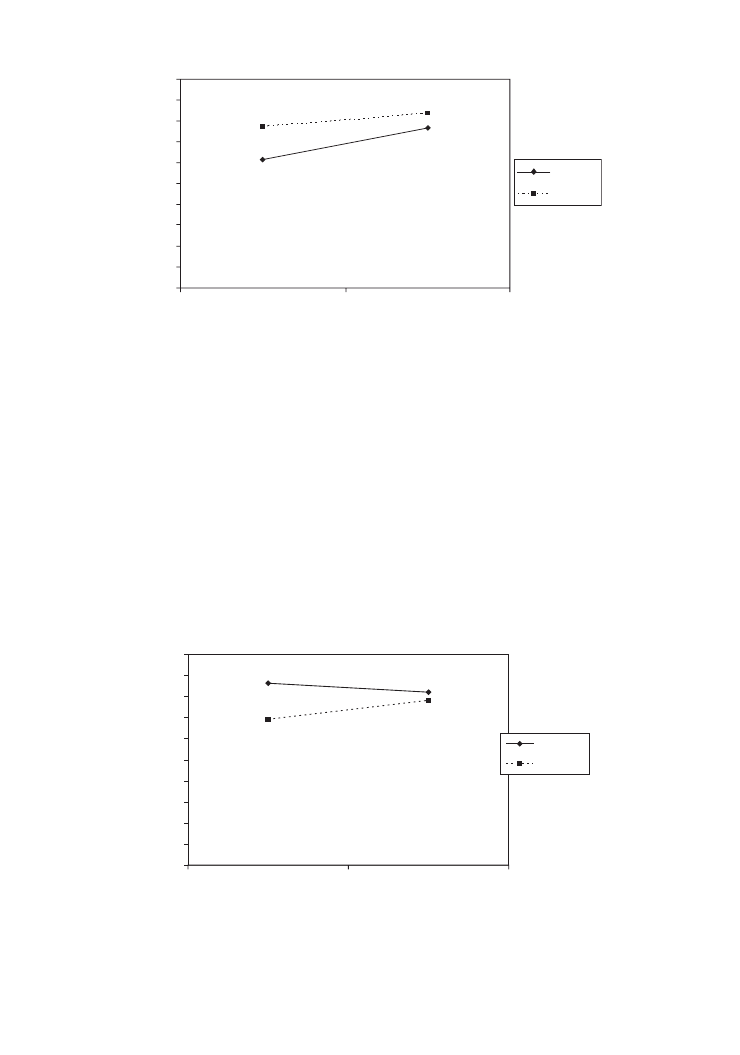

employees than for full-time employees. In order to test this proposition, we conducted

again a hierarchical, moderated regression analysis with standardised variables, controlling

for age and gender. The interaction term involving type of contract and identification (see

Figure 2) was significant with

b

.43 (p B.05; F(5, 186) 20.34; p B.01, R

2

.35). The

plot of this interaction reveals that the corresponding hypothesis is supported by the data.

Whereas organizational identification had almost no relationship with OCB for agents

with full-time contracts, agents with a part-time contract report higher OCB if their

organizational identification was high. Thus, the findings from Van Dyne and Ang (1998)

could be replicated in our first sample of call centre agents.

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Low ID

High ID

Identification

OCB

Low MPS

High MPS

Figure 1. Interaction between motivating potential of work (MPS) and organizational identification for

organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) at work (Study 1).

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Low ID

High ID

Identification

OCB

full time

part time

Figure 2. Interaction between the organizational identification and nature of contract for organizational citizenship

behavior (OCB) at work (Study 1).

70

J. Wegge et al.

Discussion (study 1)

The results of this study make potentially valuable contributions in several ways. First, we

found the expected relationship between objective working conditions and subjective

measures of the motivating potential of work. Thus, it can be concluded that even in the

often-restricted context of call centre work possibilities are available to improve the work

motivation of customer service representatives. We will discuss this issue in more detail in

the general discussion. Second, we found that experiencing a high motivating potential of

work is also linked with high job satisfaction, high OCB, and low turnover intentions. Thus,

enhancing work motivation seems worthwhile for both employees and the organization.

Third, in line with findings from a recent meta-analysis (Riketta, 2005) and recently

developed self-categorisation models of stress (Haslam, 2004), it was found that employees

with high organizational identification were more satisfied with their job, engaged more in

OCB and were less inclined to leave the organization. Fourth, it was also found, as

expected, that motivational forces linked to the work itself (MPS) and forces linked with

self-categorisation processes (organizational identification) can combine in an additive way.

This is true for two important indicators of work motivation: job satisfaction and OCB.

Finally, our attempt to replicate the interaction reported by Van Dyne and Ang (1998) in a

sample of call centre agents was successful. In our view, this is important because in call

centres a substantial proportion of contingent (non-permanent) workers can be found. Our

finding indicates that enhancing organizational identification will be especially effective for

contingent employees.

The purpose of Study 2 was to replicate the basic findings from Study 1 in another

sample of call centre agents. Because the sample in Study 2 was composed of agents from

eight different call centres representing a wider range of organizations, a replication would

lend substantial support to the findings of our first study. More importantly, the second

study was also designed to extend the perspective by including burnout as a further

dependent variable. It was also decided to add a validated questionnaire measuring various

psychosomatic complaints to collect more information about employee’s health status.

Study 2

Sample and procedure

More than 20 call centres were approached to get approval for collecting data. Eight call

centres agreed and standardised questionnaires were distributed. In total 300 question-

naires were distributed. Call centre agents filled out the questionnaires during leisure time.

Participation was confidential and voluntary. A total of 161 usable questionnaires were

returned (average response rate 53%). Sixty-two percent of respondents were female,

average age was 32.6 years (SD

9.7 years), and mean professional experience was 2.3

years (SD

2.6 years). A total of 119 agents (73%) indicated that they performed inbound

tasks, 39 agents mainly outbound tasks; 78 agents (47%) had full-time contracts, 83 were

working part-time.

Questionnaires

Organizational identification was assessed in this study with four items similar to those of

Study 1 (e.g., ‘‘I see myself as a member of this call centre,’’ ‘‘I feel strong ties with other

members of this call centre’’). These items were averaged and provided a good reliability

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

71

(

a .86). Additionally, the questionnaire contained items from a German screening

instrument measuring different aspects of working conditions (Pru

¨ mper, Hartmannsgruber,

& Frese, 1995) that is based on previously validated instruments. Some of these items were

also taken from the Job Diagnostic Survey.

To derive an indicator of employees’ perceptions of the motivation potential of their job

(MPS), measures of autonomy (3 items), task variety (3 items), and task identity (2 items)

were averaged into a new scale (8 items,

a .79).

Job satisfaction was measured with five items (e.g., ‘‘How satisfied are you with you job in

general?’’ ‘‘. . . with the conditions at your work place,’’

a .85).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) was assessed with seven items taken from

Staufenbiel and Hartz (2000) that are similar to the measure from Study 1. Item examples

are ‘‘I help colleagues to improve their work,’’ ‘‘If colleagues are feeling blue, I try to cheer

them up’’ (

a .84).

Turnover intentions were assessed with six items (e.g., ‘‘I frequently play with the idea of

quitting,’’ ‘‘I am searching for a new job,’’

a .90).

To measure employees’ well-being, two instruments were used. The Maslach Burnout

Inventory in the German translation (MBI-D) from Bu

¨ ssing and Perrar (1992) assesses

three components of burnout: Emotional exhaustion (8 items,

a .87), Depersonalisation (5

items,

a .75), and Personal accomplishment (a subjective evaluation that one performs well

in one’s job; 8 items,

a .77.) Whereas personal accomplishment is usually scored in the

opposite direction from the other two components of the Maslach Burnout Inventory, in the

present study high values of personal accomplishment indicate good performance).

In addition, a list of 21 different types of health complaints that was developed by Mohr

(1986) was presented and agents indicated how often they had experienced these

complaints in the last 6 months (

a .91). For all scales described above, participants had

to evaluate the items on 5-point answering scales with endpoints 1

‘‘is not at all correct’’

to 5

‘‘totally correct’’; 1 ‘‘never’’ to 5 ‘‘very often’’; or 1 ‘‘not at all’’ to 5 ‘‘very

much.’’ Finally, the degree of training was assessed with a single item asking agents to

indicate how often they participated in training in the last year (from 1

‘‘never’’ to

5

‘‘more than three training courses’’).

Results (study 2)

Table III presents means, standard deviations, and correlations of variables from Study 2.

All scales proved to be sufficiently reliable. Moreover, the observed correlations in this

sample are in the expected direction and again modest in size indicating that different

constructs were assessed.

Test of Hypothesis 1. Based on the zero-order correlations (see Table III), it can be

concluded that Hypothesis 1 is again corroborated by the data. Higher MPSs were

observed for employees with outbound tasks (r

.21), more training activities (r .27),

and full-time contracts (r

.18).

Test of Hypothesis 2a. In order to test this hypothesis, we examined seven zero-order

correlations in this study. Six of these correlations are significant as expected. These are

the correlation between: motivating potential and job satisfaction (r

.37); motivating

potential and OCB (r

.42); motivating potential and turnover intentions (r .25);

motivating potential and health complaints (r

.29); motivating potential and

72

J. Wegge et al.

Table III. Means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and zero-order correlations (Study 2).

M

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

1. Age

32.9

9.8

/

2. Gender

1

1.37 0.48

.11

/

3. In vs. outbound

work

2

1.25 0.43

.04

.38**

/

4. Type of contract

3

0.48 0.50

.05

.24**

.36**

/

5. Training

2.30 1.3

.36**

.09

.03

.02

/

6. Motivating

potential (MPS)

2.61 0.81

.01

.04

.21**

.27**

.18*

(.79)

7. Organizational

identification

3.47 0.96

.34**

.17*

.02

.04

.32**

.36**

(.86)

8. Job satisfaction

3.62 0.80

.05

.11

.02

.03

.06

.37**

.63**

(.85)

9. Organizational

citizenship (OCB)

3.89 0.66

.09

.10

.09

.11

.29**

.42**

.51**

.34**

(.84)

10. Turnover

intention

2.82 1.3

.22**

.23**

.02

.10

.19*

.25** .54** .51** .17*

(.90)

11. Health

complaints

2.24 0.72

.09

.12

.05

.10

.02

.29** .27** .38** .21*

.24**

(.91)

12. Emotional

exhaustion

2.22 0.75

.16

*

.14

.14

.14

.04

.23** .28** .46** .17*

.43**

.56**

(.87)

13. Depersonalisation

2.14 0.82

.40**

.25

.17*

.18*

.28** .11

.40** .35** .24**

.37**

.37**

.64**

(.75)

14. Personal

accomplishment

3.40 0.61

.41**

.06

.01

.10

.25**

.40**

.48**

.33**

.38**

.38** .32** .39** .40** (.77)

* p B.05, ** p B.01.

Notes: n between 161 and 141 due to missing data. Cronbach’s alphas are on the diagonal,

1

female

1, male 2;

2

Inbound tasks

1, outbound tasks 2,

3

part

time

0, full-time 1.

W

o

rk

motiva

tion,

identification,

and

well-b

eing

in

call

centre

wor

k

73

emotional exhaustion (r

.23); and motivating potential and personal accomplishment

(r

.40). One component of burnout (depersonalisation), however, is not significantly

correlated with motivating potential even though the relationship is in the expected

direction (r

.11). Taken together, this pattern strongly supports Hypothesis 2a.

Test of Hypothesis 2b. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the relevant seven zero-order

correlations involving organizational identification. All of them are significant as expected.

Employees who felt more attached to their organization were more satisfied with their job

(r

.63), engaged more in OCB at work (r .51), and were less prone to leave the

organization (r

.54). Moreover, these agents reported fewer health complaints

(r

.27) and less burnout (r .28 for emotional exhaustion, r .40 for deperso-

nalisation, and r

.48 for personal accomplishment). These results clearly support our

hypothesis.

Test of Hypothesis 2c. Motivating potential and organizational identification correlated

moderately once again (r

.36), so that it makes sense to test whether both variables

combine to predict work motivation and well-being. To examine this issue further, a series

of seven hierarchical regression analyses was conducted (see Tables IV and V) following

the suggestions of Aiken and West (1991). These regressions were similar to those

described for Study 1 (entering age and gender as demographic controls first, both

standardised predictor variables in step 2, and adding a standardised product-term of both

predictors in a last step). In six out of seven tests, Hypothesis 2c could be supported

because both predictor variables had a significant

b-weight in step 2 of these regressions.

The only exception found was for depersonalisation, because motivating potential had no

substantial association beyond organizational identification for this dependent variable.

This is also in line with the zero-order correlations. It is also noteworthy that motivating

potential and organizational identification explained quite a substantial amount of

variance in dependent variables (in the range of 9 to 42%). For two of the seven variables

the interaction term was also significant (health complaints and emotional exhaustion). A

plot of these interactions (see Figure 3 and Figure 4) indicates that in both cases only

employees with high organizational identification reported fewer health complaints if they

also perceived a high motivating potential at work. This implies that, for customer service

Table IV. Summary of hierarchical regression analyses (Study 2).

Job satisfaction

Organizational

Citizenship Behaviour

(OCB)

Turnover intention

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

Age

.00

.01

.05

.00

.01

.09

.00

.01

.20

*

Gender

.16

.13

.09

.16

.11

.11

.51

.21

.19*

Step I: R

2

.01

.02

.08**

Motivating potential (MPS)

.12

.05

.15

*

.17

.05

.26**

.14

.10

.11

Organizational identification

.50

.06

.62**

.31

.05

.46**

.62

.11

.47**

Step II: R

2

/

DR

2

.43**/.42**

.36*/.33**

.33**/.25**

MPS

Organizational identification

.01

.05

.08

.00

.04

.06

.12

.09

.09

Step III: R

2

/

DR

2

.44**/.01

.36**/.00

.34**/.01

* p B.05, ** p B.01.

Notes: n

158 for job satisfaction, n 155 for OCB, n 147 for turnover intention.

74

J. Wegge et al.

Table V. Summary of hierarchical regression analyses (Study 2).

Health complaints

Emotional

exhaustion

Depersonalisation

Personal

accomplishment

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

B

SE B

b

Age

.00

.01

.12

.00

.01

.14

.00

.01

.37** .00

.01

.42**

Gender

.19

.13

.13

.19

.13

.12

.34

.12

.21** .00

.10

.01

Step I: R

2

.03

.04

.20**

.18**

Motivating potential (MPS)

.14

.06

.19

*

.14

.06

.19*

.00

.06

.03

.18

.05

.29**

Identification

.15

.07

.20* .15

.07

.20* .25

.06

.31** .18

.05

.28**

Step II: R

2

/

DR

2

.13**/.10**

.13**/.10**

.29**/.09**

.38**/.20**

MPS

Identification

.12

.06

.17* .14

.06

.18*

.00

.06

.06

.00

.04

.03

Step III: R

2

/

DR

2

.16*/.03*

.17**/.03*

.29**/.00

.38**/.00

* p B.05, ** p B.01.

Notes: ns

136, 144, 151, 146 for health complaints, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal

accomplishment.

W

o

rk

motiva

tion,

identification,

and

well-b

eing

in

call

centre

wor

k

75

representatives who were highly identified with their organization, a good task design

ensured better well-being.

Test of Hypothesis 3. Similar to Study 1, full-time employees also tended to engage in more

OCB than part-time employees, although the corresponding correlation (r

.11, see Table

III) was only marginally significant. Thus, Hypothesis 3a could not be supported.

Hypothesis 3b predicted that the relationship between organizational identification and

OCB was stronger for part-time employees. We tested this proposition once again with a

hierarchical, moderated regression analysis with standardised variables, controlling for age

and gender. The interaction term involving contract and identification (see Figure 5) was

significant with

b

.26 (p B.01; F(5,149) 16.18. p B.01, R

2

.35). The plot of this

interaction shows that the corresponding hypothesis is also supported in Study 2. Whereas

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Low ID

High ID

Identification

Health Complaints

low MPS

high MPS

Figure 3. Interaction between the motivating potential of work (MPS) and organizational identification for health

complaints (Study 2).

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Low ID

High ID

Identification

Emotional Exhaustion

low MPS

high MPS

Figure 4. Interaction between the motivating potential of work (MPS) and organizational identification for

emotional exhaustion (Study 2).

76

J. Wegge et al.

organizational identification made little difference to OCB for agents with full-time

contracts, agents with a part-time contract reported much higher OCB if their

organizational identification was high than if their organizational identification was low.

Thus, the main findings from Van Dyne and Ang (1998) could once again be replicated.

General discussion

Despite stereotypical perceptions, the work of call centre agents is neither simple nor

undemanding. Therefore, researchers have started to analyse the various factors that make

call centre work stressful (Dormann & Zijlstra, 2003; Holman, 2003). The purpose of this

study was to contribute to this research by investigating whether traditional approaches of

job design can also be applied to improve work motivation and well-being in call centres.

Moreover, we examined the impact of organizational identification on various indicators of

work motivation and well-being. In line with a recently developed self-categorisation model

of stress (Haslam, 2004), it was assumed that a strong attachment to the organization would

help employees to adhere to organizational norms (e.g., being friendly to customers) and

(or) to handle the problems linked to their core tasks (e.g., communicating with often

unfriendly customers) more efficiently. Thus, apart from designing core task features,

improving organizational identification might be a successful intervention to enhance well-

being and to reduce turnover in call centres. In addressing these issues, the present study

also aimed to examine how the two factors might combine and whether organizational

identification relates to the work motivation (OCB) of part-time employees more positively

than the work motivation of full-time employees. Answering this last question is important,

as part-time, contingent contracts are very prominent in call centres.

With regard to the first aim, two main findings that could be replicated across the two

studies have to be emphasised. First, it was shown that higher MPSs for the task were

observed in call centres for employees with outbound tasks, more training, and full-time

contracts. Thus, these variables can be considered as important starting points for

improving work motivation. Moreover, it is clear from these findings that even in

surroundings where the basic task itself can hardly be changed, significant relationships

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Low ID

High ID

Identification

OCB

part time

full time

Figure 5. Interaction between the organizational identification and nature of contract for organizational citizenship

behavior (OCB) at work (Study 2).

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

77

between various aspects of work and motivating potential can be found. We also found

evidence in support of the main proposition of the underlying model in both studies: high

motivating potential corresponded with high work motivation (high job satisfaction, OCB,

personal accomplishments, and low turnover intentions) and better well-being (lower health

complaints and low emotional exhaustion). Taken together, in our view the replication of

these findings in two independent samples of customer service representatives coming from

10 different call centres lends strong support to the JCM of Hackman and Oldham (1980).

Using this model and corresponding interventions, therefore, would probably be effective

for improving work motivation and health in call centres, too. In line with Holman (2003, p.

129

/

130), these findings reveal ‘‘the old rules still apply in a new setting.’’ Providing greater

variety and autonomy, for instance through work redesign, should thus have positive effects

on agents’ attitudes and well-being.

What is the impact of organizational identification on the work motivation and well-being

of customer service representatives? In addressing this question, we referred to basic

insights and findings from social identity theory. According to this theory and recent

refinements with respect to appraisal of stressors and coping with stress in a social context

(see Haslam, 2004), strong psychological attachment of employees to their organization

should typically improve work motivation and well-being. Our research was not designed to

show that feeling strong ties with an organization reduces stress because employees have

fewer problems to adhere to organizational norms (e.g., being always friendly to customers)

or because they receive more social support in coping efficiently with stressors. Never-

theless, we were able to replicate in both studies that strong relationships exist between

organizational identification and several indicators of work motivation and well-being in this

context. A high organizational identification corresponded with high work motivation (high

job satisfaction, OCB, personal accomplishment, and low turnover intentions) and better

well-being (lower health complaints, lower emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation). As

the strengths of these relationships were slightly greater than those for the motivating

potential, it might be tempting to conclude that organizational identification in call centres

is more important in explaining work motivation and well-being than a good job design. To

analyse this issue, we have to consider how both factors relate to each other and whether the

correlations with dependent variables reflect the same or different processes.

The similarity of the findings for work motivation and organizational identification is

striking. As these variables are correlated positively in both studies (r

.39 and r .36), one

might expect that the same relationships always underlie these significant correlations.

However, and this deserves attention in practice as well as theory, we found consistent

evidence that motivational forces linked to the work task itself (MPS) and forces linked with

self-categorisation processes (organizational identification) combine in an additive way for

job satisfaction, OCB, health complaints, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplish-

ments. For explaining variance in turnover intentions (and this was replicated in both

studies, as was the finding for job satisfaction and OCB), organizational identification was a

stronger predictor than MPS. Finally, depersonalisation only correlated significantly with

organizational identification. Thus, both variables (and corresponding interventions to

change them, see Hackman & Oldham, 1980; Haslam, 2004; Rose, Jones, & Fletcher,

1998; Schreurs & Taris, 1998) should be taken into account when seeking to improve work

motivation and well-being in call centres. For reducing turnover intentions or feelings of

depersonalisation, organizational identification seems to be even more important than work

motivation.

78

J. Wegge et al.

In sum, we found strong evidence in both samples for a model that conceptualises

motivating forces linked to the task and those forces that are linked to the social identity of

employees and self-categorisation processes as rather independent from each other (see Van

Dick & Wegge, 2004, for a detailed account of these ideas, adding goals as a third basic

motivational force). There was also evidence, however, for interaction effects of MPS and

organizational identification: for OCB in Study 1 and for health complaints and emotional

exhaustion in Study 2. The pattern of these interactions is quite consistent, as employees

seemed always to benefit when both factors were positive, supporting the idea that

enhancing both motivational forces simultaneously is beneficial.

The final aim of this study was to examine whether the finding from Van Dyne and Ang

(1998) could be replicated for call centre agents. These researchers analysed the impact of

organizational commitment on OCB for contingent workers and full-time employees in two

service organizations (a bank and a hospital). According to their findings, enhancing

organizational identification leads to more OCB, especially for contingent workers. In both

of our studies we were able to replicate this interaction. Agents with a part-time contract

reported higher OCB if their organizational identification was high. Since part-time

contingent contracts are very prominent in call centres, the implication of this finding is

clear. Improving organizational identification to enhance extra-role behavior should deliver

considerable benefits for part-time employees.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, caution in interpreting the results is warranted due

to the substantive use of self-reports. In general, this was necessary because most concepts

involved here (e.g., organizational identification, feelings of burnout) are very difficult to

measure by other means. However, it might be fruitful to add more behavioral indicators in

future studies (e.g., indicators of well-being such as company records on absence and

turnover rates). It is noteworthy that we also assessed several core features of working

conditions (e.g., the form of the contract, inbound vs. outbound work) by self-report. Our

corresponding analysis revealed that these job features are related to other subjective, more

complex measures (e.g., the motivating potential of work) in a way that is very similar to

what is reported in other studies without these limitations. This lends some support to the

quality of the data. In addition, we made sure in both studies that data collection was

anonymous. Therefore, some typical problems of self-reports (e.g., biases induces by social

desirability) are probably not relevant here. Nevertheless, replications with optimised

methods are recommended.

A related potential drawback of this study is that both samples rely on mono-source data

derived from the call centre agents’ perspective only. Common method variance may

therefore overestimate main effects. However, common method variance cannot account for

interaction effects. On the contrary, this potential bias typically leads to an underestimation

of statistical interactions (Evans, 1985; McClelland & Judd, 1993). Therefore, we can have

some confidence in the various interactions obtained in this study despite the mono-source/

mono-method design.

It should also be noted that emotional labour and in particular emotional dissonance was

not considered in our research. As emotional labour can be as an important factor in call

centre work that is systematically linked with the well-being of agents (e.g., Wegge et al.,

2006; Zapf et al., 2003), future studies should also seek to address the interplay of

organizational identification, task design, and emotional labour. In the same vein, a more

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

79

precise examination of those working conditions that demonstrated a positive correlation

with motivating potential in both studies (inbound vs. outbound work, training on the job,

the nature of employment contracts) might be fruitful. As the causal factors underlying

these relationships were not investigated, they should be examined in future studies, for

example, if training activities are generally experienced as job enrichment by agents or if

jobs with high motivating potential in call centres solely require more training to complete

them effectively. Similarly, it could be analysed if the difference in findings between working

on inbound and outbound calls depends on the nature of these calls (e.g., the duration, the

use of scripts) or on the higher discretion (decision latitude of agents) associated with

outbound calls.

A further limitation pertains to the cross-sectional design of both studies. A longitudinal

study would enable causal hypotheses to be tested regarding the impact of, for example,

motivating potential on satisfaction and well-being. However, with respect to traditional

approaches of job design there is already ample evidence that such a causal interpretation is

warranted (e.g., Bond & Bunce, 2001). As experimental evidence for the causal role of

organizational identification in the stress process is also available (e.g., Haslam, 2004), we

believe that the basic propositions that can be derived from our correlational study will, at

least in part, also prove valid in a longitudinal test. Moreover, as our samples were

composed of agents from 10 different call centres, it seems reasonable to assume that

corresponding results would also be found in similar organizations.

Implications for practitioners

These findings have implications for call centre practitioners on two levels. First, at the

operational level, real benefits to both call centre organizations and agents would accrue

from: job designs that facilitate greater involvement, participation, and autonomy; and more

sophisticated call handling requirements in the form of low volume, long duration, high-

skill, phone-based customer interactions. Second, and perhaps most significantly, the

importance of both work motivation and organizational identification with regard to job

satisfaction, OCB, health complaints, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment,

challenges the current deployment and positioning of call centre business units themselves.

However, it would prove very difficult to implement the operational-level job design and call

handling requirements within the majority of call centres in their present form. The

suggestion here is that call centres need to evolve into more sophisticated, customer-

responsive business units in order to enable higher work motivation and organizational

identification.

At their origin in the 1980s, call centres were cost reduction, labor-saving inspired

business units that facilitated for the first time both the centralisation of customer

interactions and the employment of mass production methodologies within the service

sector. Taylor and Bain (1999) have defined the call centre labor process as an ‘‘assembly

line in the head.’’ The implication here is that call centre agents are not only under pressure

to handle vast numbers of calls but also that the calls are unskilled, short-cycle, monotonous

tasks. Taylor and Bain’s factories of the mind analysis clearly suggest that it would be

impossible to give rise to greater work motivation and organizational identification. Set

against such negative characterisations of the call centre workplace, however, are studies like

the one conducted by Frenkel, Tam, Korczynski, and Shire (1998) that pays tribute to the

high levels of skill that is sometimes required by frontline employees to perform challenging

and interesting phone-based customer transactions. In other words, the control and

80

J. Wegge et al.

compliance modus operandi concomitant with mass production are inappropriate and

therefore rejected where an organization providing high quality, value-added services relies

on the skills, initiative, and discretion of its employees to gain competitive advantage.

Recent research, however, suggests that while high quality phone-based professional

services do exist they characterise only a minority of transactions generally reserved for

high value clients (Batt & Moynihan, 2002).

Conclusions

We would argue that our research supports the promotion of greater work motivation and

organizational identification within call centres. Moreover, we believe that our studies have

contributed to the understanding of powerful factors influencing the attitudes and well-

being of call centre agents. Addressing and improving both the motivating potential of call

centre work as well as enhancing the organizational identification of call centre agents can

also help to overcome the reputation of call centres as ‘‘electronic sweatshops,’’ ‘‘satanic

mills,’’ or ‘‘battery farms’’ (see Sprigg, Smith, & Jackson, 2003). Instead of this, and in line

with Shah and Bandi (2003), who provide a positive case study of a motivating call centre

environment, at least some call centres of the future could and should provide challenging

work and constant opportunities for training, learning, and development.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of

this paper.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. New York: Sage.

Batt, R., & Moynihan, L. M. (2002). The viability of alternative call center production models. Human Resource

Management Journal, 12, 14

/

34.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited

resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252

/

1265.

Baumgartner, M., Good, K., & Udris, I. (2002). Call centers in der Schweiz. Psychologische Untersuchungen in 14

Organizationen [Call centers in Switzerland. Psychological investigations in 14 organizations]. Reports from the

Institute for Work Psychology. Zu

¨ richSwitzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2001). Job control mediates change in a work reorganization intervention for stress

reduction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6, 290

/

302.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2003). Development and validation of the emotional labour scale. Journal of

Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76, 365

/

379.

Bu

¨ ssing, A., & Perrar, K.-M. (1992). Die Messung von Burnout. Untersuchung einer deutschen Fassung des

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI-D) [Measurement of burnout: Analysis of a German version of the MBI].

Diagnostica, 38, 328

/

353.

Deery, S., Iverson, R., & Walsh, J. (2002). Work relationships in telephone call centers: Understanding emotional

exhaustion and employee withdrawal. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 471

/

496.

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2004). Customer-related social stressors and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health

Psychology, 9, 61

/

82.

Dormann, C., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2003). Call centres: High on technology—high on emotions. European Journal of

Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 305

/

310.

Evans, M. G. (1985). A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple

regression analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 305

/

323.

Evans, M. G. (1991). The problem of analyzing multiplicative composites. American Psychologist, 46, 6

/

15.

Frenkel, S., Tam, M., Korczynski, M., & Shire, K. (1998). Beyond bureaucracy? Work organization in call centers.

International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9, 957

/

979.

Work motivation, identification, and well-being in call centre work

81

Fried, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (1987). The validity of the Job Characteristics Model: A review and meta-analysis.

Personnel Psychology, 40, 287

/

322.

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal

of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 95

/

110.

Grandey, A., Dickter, D., & Sin, H.-P. (2004). The customer is not always right: Customer verbal aggression toward

service employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 397

/

418.

Grebner, S., Semmer, N. K., Faso, L. L., Gut, S., Ka¨lin, W., & Elfering, A. (2003). Working conditions, well-being,

and job related attitudes among call center agents. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12,

341

/

365.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology,

60, 159

/

170.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Haslam, S. A. (2004). Psychology in organizations: The social identity approach (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., O’Brien, A., & Jacobs, E. (2004). Social identity, social influence, and reactions to

potentially stressful tasks: Support for the self-categorization model of stress. Stress and Health, 20, 3

/

9.

Holman, D. (2002). Employee well-being in call centers. Human Resource Management Journal, 12, 35

/

50.

Holman, D. (2003). Call centers. In D. Holman, T. D. Wall, C. W. Clegg, P. Sparrow, & A. Howard (Eds.), The new

workplace: A guide to the human impact of modern working practices (pp. 115

/

134). Chichester: John Wiley.

Holman, D., Chissick, C., & Totterdell, P. (2002). The effects of performance monitoring on emotional labor on

well-being in call centers. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 57

/

81.

Isic, A., Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (1999). Belastungen und Ressourcen an Call Center Arbeitspla¨tzen [Job stressors

and resources among call center employees]. Zeitschrift fu

¨ r Arbeitswissenschaft, 53, 202

/

208.

Johns, G. (1997). Contemporary research on absence from work: Correlates, causes and consequences. In C. L.

Cooper, & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology Vol. 12 (pp.

115

/

174). Chichester: Wiley.

Lewig, K. A., & Dollard, M. F. (2003). Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in call

center workers. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 366

/

392.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects.

Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376

/

390.

Mohr, G. (1986). Die Erfassung psychischer Befindensbeeintra