Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Customer-induced stress in call centre work:

A comparison of audio- and videoconference

Ju¨rgen Wegge

1

*, Joachim Vogt

2

and Christiane Wecking

3

1

Technical University of Dresden, Germany

2

University of Copenhagen, Denmark

3

University of Dortmund, Germany

Call centre work was simulated in an experiment with 96 experienced call centre

agents. The experimental design comprised two factors. First, agents communicated

with customers either via phone, pc-videoconference or pc-videoconference with

additional instructions increasing time pressure. The second experimental factor varied

customer behaviour: half of the customers were friendly whereas the other half were

rude. Several indicators of strain (e.g. emotional dissonance, tiredness) were assessed

by self-reports. Moreover, the levels of immunoglobulin A (IgA) in salvia were

determined at three sampling points and specific behaviours of agents (e.g. smiling to

customers) were assessed using video data. It was found that unfriendly customer

behaviour led to more strain and lower call performance than friendly customer

behaviour. Inducing time pressure increased IgA-levels and reduced talking-time with

customers. However, contrary to the expectations, the availability of video data did not

enhance strain of agents. Instead, it was found that videoconferencing increased

activation of agents if customers were friendly. Since higher levels of activation can

counteract boredom and because customers often prefer to see their service

providers, adding videoconference facilities in call centres seem to be a fruitful way of

enriching routine call centre work.

The main purpose of this paper is to contribute to research on stress in call centre work.

As different forms of computer-mediated communication (e.g. emails, videoconference)

become more and more prominent as vehicles for communication (Olson & Olson,

2003; Wegge, 2006; Wegge & Bipp, 2004), and because in call centre work computers as

well as electronic connections with customers are already available, it is likely that

having a videoconference will soon be part of the daily work of agents. Therefore, it is

interesting to explore whether this new form of interaction with customers is neutral

with respect to strain and performance of call centre agents. Is a phone call with a verbal

aggressive customer more demanding when agents and customers can also see each

* Correspondence should be addressed to Prof. Dr Ju¨rgen Wegge, TU Dresden, Fakulta¨t Mathematik und

Naturwissenschaften, Arbeits und Organisation Psychologie, 01062 Dresden, Germany (e-mail: wegge@psychologie.tu-

dresden.de).

The

British

Psychological

Society

693

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2007), 80, 693–712

q

2007 The British Psychological Society

www.bpsjournals.co.uk

DOI:10.1348/096317906X164927

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

other? And what happens if customers are in a good mood and make compliments

towards agents? Do agents feel comfortable in this situation, and particularly so if they

can see the customers? The main purpose of this research is to collect empirical

evidence that allows answering these and similar questions. In a laboratory experiment

with experienced call centre agents as participants, we investigated whether the typical

work of agents changes when talks with customers are conduced via videoconference.

In addressing this issue, we further analyse the impact of two common stressors in call

centre work: customer aggression and time pressure. In the following, we first address

the phenomenon of customer-induced stress. Next, we present a brief overview

regarding research on videoconferencing and discuss potential benefits and problems of

this communication technology in call centre work.

Customer aggression as a prominent stressor in call centre work

Previous studies have shown that customers are often rude (Dormann & Zapf, 2004) and

this is also the case in interactions with call centre agents (Grandey, Dickter, & Sin,

2004). Since agents are supposed to be always friendly to customers, and because their

performance is usually controlled by the organization (e.g. by making test calls),

deviations from this norm will easily be detected (Holman, 2003). Hence, strong

requirements to hide or downplay negative emotions and to fake positive emotions

during work are present in call centre work. A study of Totterdell and Holman (2003)

illustrates this point. Using a time-sampling (diary) method over 2 weeks, Totterdell and

Holman found in a sample of 18 call centre agents that in about 9% of all occasions,

customers were judged to be unpleasant and that this was significantly associated with

agents faking emotions. They reported that they tried to appear more enthusiastic as

they would feel on 58% of all occasions. The opposite form of faking emotions (to be less

enthusiastic as felt) occurred only in 15% of all occasions. This specific phenomenon – a

discrepancy between expressed and felt emotions – is named ‘emotional dissonance’ in

theories of emotion work (Grandey, 2000; Zapf, 2002) and several prior studies found

that unfriendly or rude customers induce more emotional dissonance than friendly

customers in service jobs (e.g. flight attendants, retail clerks; Dormann & Zapf, 2004;

Fischbach, 2003; Tschan, Rochat, & Zapf, 2005). For call centre work, at least one study

with similar findings is available (Wegge, van Dick, & Wecking, 2006). Moreover, we

know from prior research that the volitional presentation of non-felt emotions and the

continuous self-control of one’s own feelings are demanding and, therefore, might also

lead to lower task performance (see Tice & Bratslavsky, 2000; Zapf, 2002 for reviews).

Accordingly, we propose:

H1a:

Compared to friendly customers, unfriendly customers provoke more intense emotions

and induce more strain (e.g. emotional dissonance) in call centre agents.

H1b:

Compared to friendly customers, unfriendly customers provoke a less friendly service

(e.g. less laughing) and lower task performance (deviations from scripts) of agents.

Potential effects of videoconferencing in call centre work

To our knowledge, no empirical studies are available that investigated the effects of

videoconferencing (vc) in call centre work. However, several basic features of

videoconferencing (e.g. availability of video data) are relevant for this work environment,

too. When compared with communication via e-mail or phone, facial information as well

694

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

as other non-verbal signals can be utilized and prior studies found that this helps, for

example to improve speech perception, person identification, perception and inference

of emotional states, and the general regulation of conversations (Bruce, 1996; Finn, Sellen,

& Wilbur, 1997; Wallbott, 1998). However, there is also strong evidence documenting that

communication via videoconference has some specific disadvantages. These disadvan-

tages are based on several features of videoconferences. The most important features are:

(a) the missing eye-contact due to the use of cameras and camera positioning; (b) a

temporal delay of signals due to coding and transmission times; (c) the fade-out of some

visual information and (d) the use of physically separated rooms (Finn et al., 1997; Meier,

2000). All these differences can lead to severe problems in communicating via

videoconference such as problems regarding effective turn-taking during discussions or

problems with respect to using continuous backchannel signals (e.g. ‘Yes’, ‘I see’) that

indicate understanding and communication readiness. In view of these problems, it is no

surprise that users of vc often produce longer and more interrupted dialogues and develop

less mutual understanding, even when compared with those who solely use an audio-link

(O’Mailley, Langton, & Anderson, 1996; Purdy, 2000; see however Day & Schneider, 2002).

In addition, it is regularly found that participants overcompensate communication

problems in videoconferences by increasing the level of verbal and non-verbal behaviour

(Blokland & Anderson, 1998; Meier, 2000). This can make the communication situation

strange and might hinder individuals to express themselves as usual.

Communication between call centre agents and customers serves various purposes,

for example taking orders, advertising and hard selling. Therefore, it might be that the

availability of the customers’ video data improves the quality of these services because

speech perception, person identification and the inference of emotional states of

customers are improved. Based on a better regulation of conversations with customers

and in view of possible multimedia effects, the social influence of agents on customers

should be enhanced. This conclusion is also consistent with results obtained in social

presence research. The concept of social presence comprises a number of dimensions

relating to the degree of interpersonal contact (e.g. immediacy, intimacy). Developed by

Short, Williams, and Christie (1976), this effect represents a basis for many later models

of computer-mediated communication (e.g. media richness, for a recent review, see

Tanis, 2003). Social presence is defined by Short et al. (1976, p. 65) as the degree of

salience of the other person in the interaction. It is assumed that social presence is

conveyed by many features such as non-verbal signals and facial expression. Increased

social presence should make interactions more personal, spontaneous and efficient in

terms of personal influence. In support of this proposition, several studies have found

that different media types can be distinguished with respect to social presence

judgments. Face-to-face (ftf) communication is judged as most socially present and

written messages are rated least socially present. For videoconferences, only few data

are available but most researchers (e.g. Short et al., 1976; Wegge, Bipp, & Kleinbeck,

2007) reported high values close to ftf-communication.

As the social presence of customers should be also high in communication via

videoconference, it is very likely that messages or actions of customers lead to more

intensive states and processes (e.g. attitudes, behaviour, emotions) on the side of

the agent compared with a similar situation where customers and agents communicate

phone-to-phone. Therefore, it is likely that negative emotions induced by aggressive

customers, for example should be experienced more intense when communication is

conducted via videoconference. Moreover, in a videoconference between an agent and a

customer, customers have access to video data of the agent and, of course, the agent is

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

695

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

aware of this. According to the theory of objective self-awareness (Wicklund, 1979), the

availability of cameras and/or one’s own picture in a social situation increases

self-awareness. Furthermore, it was found in several studies that a high degree of self-

awareness makes persons more self-critical so that emotional states that are experienced

in the actual situation should become more salient (Wegge, 2006). Hence, the

experience of emotions as well as the experience of emotional dissonance of agents is

probably increased by the availability of the own picture on the side of customers.

Based on the research reviewed above and the underlying theories, in particular

social presence theory (Short et al., 1976) and the theory of self-awareness (Wicklund,

1979), we formulate the following hypotheses with respect to the potential impact of

videoconferencing on strain and behaviour of call centre agents.

H2a:

Compared to an audio interaction, the availability of video data leads to more intensive

emotions of agents and more intensive strain (e.g. emotional dissonance).

H2b:

Compared to an audio interaction, the availability of video data leads to more intensive

expression of positive emotions (e.g. laughing, smiling, showing agreement).

It should be noted that we did not expect any effect of video data on the expression

of negative emotions as participants were asked to be always friendly to customers.

Moreover, participants were trained call centre agents who know the importance of this

rule and their actual behaviour was videotaped (cf. method section).

Time pressure as an additional stressor

A further common stressor in call centre work is time pressure (Holman, 2003; Zapf,

2002). Customers usually expect to be served as quickly as possible. However, due to

unexpected high call volumes or mismanaged call distributions, many customers

experience long waiting times. As customer satisfaction is negatively affected by long

waiting times, the tasks of agents are often conducted under high time-pressure (Taylor

& Bain, 1999). Most phone calls with customers take only a few minutes and feedback or

incentives are available in many call centres to handle calls as fast as possible (Holman,

2003). In addition, prior research has shown that strain of agents (e.g. emotional

exhaustion) is higher if the average length of calls is short (Deery, Iverson, & Walsh,

2002). It can also be expected that time pressure causes acute arousal, for example

activation of the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system which can be monitored by

means of electrophysiological and biochemical methods, for example by measuring

immunoglobulin A (IgA) secretion. IgA is an immunological protein that is present in the

secretions covering the mucosa, and it forms a first line of defence against invading

pathogens. IgA secretion has been used as a measure of both acute arousal and chronic

strain because it increases in acute active coping situations within minutes of challenge

whereas passive coping after prolonged periods of chronic stress causes reduced

transport of this antibody. As the experiment presented here used the former kind of

acute active coping situations in call centre work, IgA seemed a suitable

biopsychological indicator of acute arousal in addition to self-report (e.g. emotional

dissonance) and observation data (e.g. talking times). Overall, high time-pressure is a

common problem in call centre work and well-being is typically found to be reduced in

this context if time pressure is high. Therefore, we decided to examine the importance

of this stressor by adding conditions with high time-pressure when agents

communicated via videoconference. Our first corresponding hypothesis is:

696

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

H3a:

Adding time pressure in a videoconference with customers leads to higher strain (e.g.

emotional dissonance, high salivary IgA-levels) and less time talking with customers.

In addition, we examined a hypothesis regarding the interaction between time

pressure and customer friendliness. This proposition is build on the above derived

assumptions, namely, that agents have mainly problems with unfriendly customers and

high time-pressure:

H3b:

The impact of time pressure on customer-induced strain (e.g. emotional dissonance) is

moderated by customer friendliness: if customers are unfriendly, the negative effect of time

pressure is amplified.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 42 male and 54 female call centre agents. After getting approval

from management, agents were recruited by advertisements that were distributed to 20

call centres. They were asked to participate in a simulation study on call centre work for

25e. In some experimental conditions, further financial incentives for attaining goals

related to communication times with customers were provided (see below).

The participants’ mean age was 29.8 years (SD ¼ 9

:9). Agents had to work at least 2

months in a call centre in order to participate in this study (mean tenure was 37.5

months, SD ¼ 35

:7).

General procedure

On arrival, the experimenter informed participants that this study examines causes of

stress in call centre work. He explained that three salvia samples (allowing the

measurement of immunoglobulin A, IgA) and answers to several questionnaires have to

be given for this purpose. To increase the realism of this simulation, the laboratory room

and the whole material and equipment closely resembled a typical call centre office.

Next, participants received a detailed introduction to the experimental simulation and

an explanation of their computer workplace. They were told that they were hired as an

agent responsible for customer services linked to mobile phones produced by the firm

‘OTKOM’. The experimenter explained that agents always would have to be very

friendly to customers and that OTKOM sees the customers as ‘kings’. Therefore, agents

were required to give an excellent service and always had to ‘smile down the line’.

The experimenter further explained that six customer calls conducted by two other

experimenters simulating typical customer behaviour follow later on. To analyse the

communication processes in detail, all interactions were videotaped with the informed

consent of participants. The corresponding camera was positioned in an unobtrusive

way in a shelf about 2 m away from the workplace. Participants were informed that

customers can have three different types of wishes: information requests, complains

regarding a product or the wish to order a product. The agents’ task was to determine

the actual type of customer request and select the corresponding option presented in

the computer program available for solving these tasks. Next, they should follow the

specified sequence of questions that was also presented on the screen. The task is

described more fully below.

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

697

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

In this introduction, the experimenter also explained the rules for gaining additional

incentives in experimental conditions with time pressure (see below). He then

distributed a first questionnaire, including biographical questions (e.g. age, gender, prior

work in call centres) and collected a first salvia sample (IgA-I) as a baseline measure.

The experimenter left the room, went over to the second laboratory and re-established

contact with the participant via the computer according to the selected communication

condition (see below). He clarified remaining questions regarding the handling of the

equipment. Next, all participants conducted six standardized talks with ‘customers’ of

OTKOM mobiles. The role of customers was played by four additional experimenters

who were unknown to participants. The experimenters (costumers) were trained for

this purpose and blind to the hypotheses of the experiment. They always followed

standardized scripts in each talk and worked as two mixed-sex teams (each participant

met only one ‘customer team’) calling participants in an alternate sequence.

After each of the six customer talks participants had to answer a brief mood checklist

assessing several aspects of their actual emotional state (e.g. degree of activation,

emotional dissonance). After the third talk, the first experimenter returned to the room

of the participant. He distributed a second questionnaire measuring customer

friendliness and collected a second salvia sample (IgA-II). The experimenter then left

the room once again and informed the ‘customers’ to continue their talks. After six talks

had been completed, the experimenter returned to the participant. He distributed a

third questionnaire measuring once again customer friendliness and collected a third

salvia sample (IgA-III). Finally, participants were paid and debriefed.

Experimental design

The design of the experiment was a 3(communication condition) £ 2(customer

behaviour) between-subject design. Participants were randomly assigned to each of the

six experimental conditions so that 15–17 individuals participated in each condition.

Contacts with customers (communication factor) were varied in such a way that either

all interactions with customers were conducted via phone ( phone), via videoconfer-

ence (vc) or via videoconference with additional instructions inducing time pressure

(vc plus time pressure). In this third condition, participants were informed that

additional financial incentives could be gained if they manage to serve customers

quickly. For each talk below 120 seconds, two extra Euros were paid. In order to provide

time-feedback, a clock that was started at the beginning of each conversation with

customers was visible on the computer screen in this condition. When the

experimenter returned after the third talk, he also stated how much additional money

was gained. Participants were further informed in this condition that the quality of

customer service is more important than service speed. Therefore, none of the elements

of the communication scripts should be omitted. Two customer calls were designed to

allow keeping the time limit. Therefore, participants should have been motivated to

attain the time goal and experience time pressure.

Customer behaviour followed prescribed scripts which were consistent with the

specified sequence of questions that agents had to ask. The behaviour of customers was

manipulated in such a way that all six customer talks were either of a friendly or an

unfriendly nature. Friendly customers praised the quality of OTKOM products in three

talks, stating for example that the prices of OTKOM mobile phones are very reasonable.

In the other three conversations, they praised the agent, stating for example that they

never talked to a more competent agent before. Unfriendly customers complained

698

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

about the low quality of OTKOM products in three calls and they insulted the call centre

agent in the other three talks (e.g. stating that the mobile phones are garbage or that the

call centre agent is incompetent). The sequence of these talks was counterbalanced

across communication conditions so that the statements regarding OTKOM products

and the personality of agents occurred with the same frequency in the first block of talks

(talks 1–3) and the second block of talks (talks 4–6).

Task

All customer calls started with a welcome note presented on the computer screen that

agents should read out. Then, agents always had to ask for the customer’s name and their

number or their date of birth if they were new. Next, agents had to check whether the

customer wished to order a mobile (order talk), needed information about an OTKOM

product (information talk) or had a complaint about products (complaint talk). Each

participant conducted two of these different types of talks in a fixed sequence so that

each type of talk was present in both blocks (talks 1–3 and 4–6). The contents of the six

talks were different (e.g. customers always presented different names and complaints)

and the structure of the three talks also varied. In an order talk, for example the agent

had to check which phone should be send, how the customer would like to pay (invoice

or credit card), ask for the shipping addresses and whether the customer wants more

information about OTKOM products. All calls ended with a farewell note presented on

the computer screen that agents should read out.

Equipment

Conversations with customers were conducted using a pc-based (desktop)

videoconference system (Zydacron OnWan 350) that utilizes LAN connections between

computers (transfer 768 kbps). The connection (via IP address) was built between two

separate labs located near each other, with a time delay between both stations about 1

second. The video display (30 fps) was presented on a 17 inch SVGA colour monitor

with a small digital camera mounted on top of the screen in conditions with a

videoconference. Headsets were always used for transmission of audio signals. Within

those connections where video data were available, only the picture of the customer

was visible on the right part of the computer screen (size approx. 4.5 £ 5.5 inch; no

picture of the agent). The program for handling the communication sequence was

presented on the left part of the screen.

Measures

The constructs in this study were assessed via observation by the experimenters, by

analysing salvia, by self-reports of participants obtained with several questionnaires at

specific times during the experiment and by analysing video data.

Observation by the experimenter

For each customer talk, the experimenters playing the customers judged on a special

sheet immediately after a talk, the time needed for the talk and the participants

performance. Performance was defined as adherence to the prescribed communication

scripts. The two experimenters noted each substantial deviation from the script (e.g. a

deviation would be that agents forget to ask for a shipping address or to give a farewell

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

699

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

note). Both experimenters controlled each other with respect to these measures and

there was no disagreement. Based on this data, the total amount of deviations from

communication scripts across all six talks was computed. This variable is considered as a

cumulative performance index (range was between 0 and 17, M ¼ 2

:76, SD ¼ 3:45).

Salvia samples (IgA)

In order to obtain saliva of sufficient volume for the IgA-analysis, the Sarstedt Salivette

was used. It contains a dental roll in a tube that can be centrifuged to extract the saliva

from the cotton. Participants were asked three times during the course of the

experiment (see above) to take a dental roll and to place it in their mouth for exactly

2 minutes. This constant time method is sufficient to control for saliva flow (Kugler,

1990). It has been shown that IgA-levels do not correlate with saliva volume (Vogt, 1998,

p. 97) and that IgA effects are independent of saliva flow (Bristow, Hucklebridge, Clow,

& Evans, 1997). After the experiment, the samples were deep-frozen at

2 208C. On the

day of analyses, they were defrosted and centrifuged by 2,000 cycles per minute for

3 minutes. IgA was determined using low-level radial immune diffusion endoplates

(method by Mancini, Carbonara, & Heremans, 1965, adopted for saliva according to

Kugler, 1990). It was expected that IgA-levels (mg/dl) increase under acute stress

(Kugler, 1994). We selected IgA as an indicator of acute arousal as it was shown before

that IgA increases under strain in a similar way as cortisol (Evans, Bristow, Hucklebridge,

Clow, & Pang, 1994). Various studies (reviewed by Evans, Clow, & Hucklebridge, 1997)

have revealed acute IgA rises in short-term tasks where arousal (i.e. activation of the

sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system) dominated over psychological stress (cortisol

secretion). Moreover, IgA was preferred over cortisol because it is less influenced by

circadian rhythms. Both cortisol (Klußmann et al., 2005) and IgA (Hagemann, Vogt,

Mauss, & Kalveram, 2000) show a peak in the early morning. While salivary cortisol

peaks were also found 45 minutes after awakening, at noon, in the afternoon and

evening, no such peaks were found in a 16-hour day for IgA (Hagemann et al., 2000).

Late afternoon IgA values, however, were found to be lower than early morning values in

the study of Tzai-Li and Gleeson (2004).

Variables assessed with questionnaires

Participants answered various questionnaires during the course of the experiment that

were constructed, in part, on the basis of several prior validated scales. After each of the

six talks with customers, participants answered a one page mood checklist.

The following four variables were measured with this checklist. Emotional Dissonance

was assessed with four items selected from the corresponding subscale of the Frankfurt

Emotion Work Scales (FEWS, see Zapf, Vogt, Seifert, Mertini, & Isic, 1999). These items

were slightly changed so that a repetition after each talk was possible. An example item

is: ‘How often did you display emotions that were not in correspondence with real

feelings?’. The reliability of this scale was good at all six points of measurement

(

a ¼

:84–:90) in this study. The mean value across the six measurement points was used

for later data analysis. Participants further answered three bipolar questions regarding

their actual mood after each talk. The first question referred to Mood Valence (from

unpleasant to pleasant), the second question concerned Activation (from calm to

excite) and the third question asked for Tiredness (from awake to tired). Prior research

has shown that these three mood dimensions describe largely independent aspects of

700

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

human moods (see for example Schimmak, 1999). In support of this assumption, a

principal component factor analysis comprising all available mood items suggested a

three-factor solution (eigenvalues

. 1 were 6.1, 2.7 and 2.3) explaining 61% of the

variance. According to the rotated matrix of the three-factor solution (varimax rotation),

all items solely showed substantial loadings on their corresponding factor. Therefore, we

built three corresponding scales for measuring the three mood dimensions.

The reliability of these measures was good as the intercorrelations across the six

points of measurement were consistently high. For mood valence, the correlations were

in the range of

:36 , r , :59 (all p , :01; if the six measures are considered as a scale,

a ¼

:77). The corresponding correlations for activation are in the range of :30 , r , :57

(all p ,

:01; a ¼ :79) and for tiredness :47 , r , :92 (all p , :01, a ¼ :92).

Time Pressure was assessed by self-report as a manipulation check after the six calls

with customers were finished. Participants answered three questions, for example: ‘I

felt under high time pressure’. The reliability of this scale that was developed for this

study was good (

a ¼

:77). Finally, Customer Friendliness was assessed as a further

manipulation check after calls 3 and 6. We used the subscale ‘disliked customers’ which

consists of four items, for example ‘Customers were hostile’. This scale was developed

within a broader context by Dormann and Zapf (2004) and also had a good reliability at

both sampling points in our study (

a ¼

:89). The mean of the two measurements was

used for data analysis. For all scales, participants had to evaluate the items on five-point

answering scales. For the three mood scales, the verbal anchors were mentioned above.

For the other items, these endpoints were 1 ¼ ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ¼ ‘strongly

agree’; 1 ¼ ‘very little’ to 5 ¼ ‘a great deal’, or 1 ¼ ‘not at all’ to 5 ¼ ‘most of the time’.

Items were coded in such a way (e.g. recoded for customer dislike) that high values

always indicated high values of the corresponding construct.

Video data

Two trained raters who were blind with respect to the experimental hypotheses judged

various aspects of the behaviour of participants using ‘The Observer 4.0’ program. The

following variables were analysed for all six calls with customers. It was coded (a) how

often agents showed a smile, (b) how often agents were laughing and (c) how long

agents were talking (or not talking) with customers during the communication period.

In addition, it was determined (d) how often agents verbally agreed with customers

(e.g. by saying ‘yes’ or ‘okay’) and (e) how often they indicated non-verbal agreement by

nodding. These variables were summed up across talks for later data analysis. In order to

examine the reliability of these measures, a randomly determined set of 10 participants

was coded by both raters. The inter-rater-reliability of these variables was high: Cohen’s

k ¼

:91 in this analysis. Therefore, the behaviour of agents was coded in a very

consistent and reliable manner by both raters.

Results

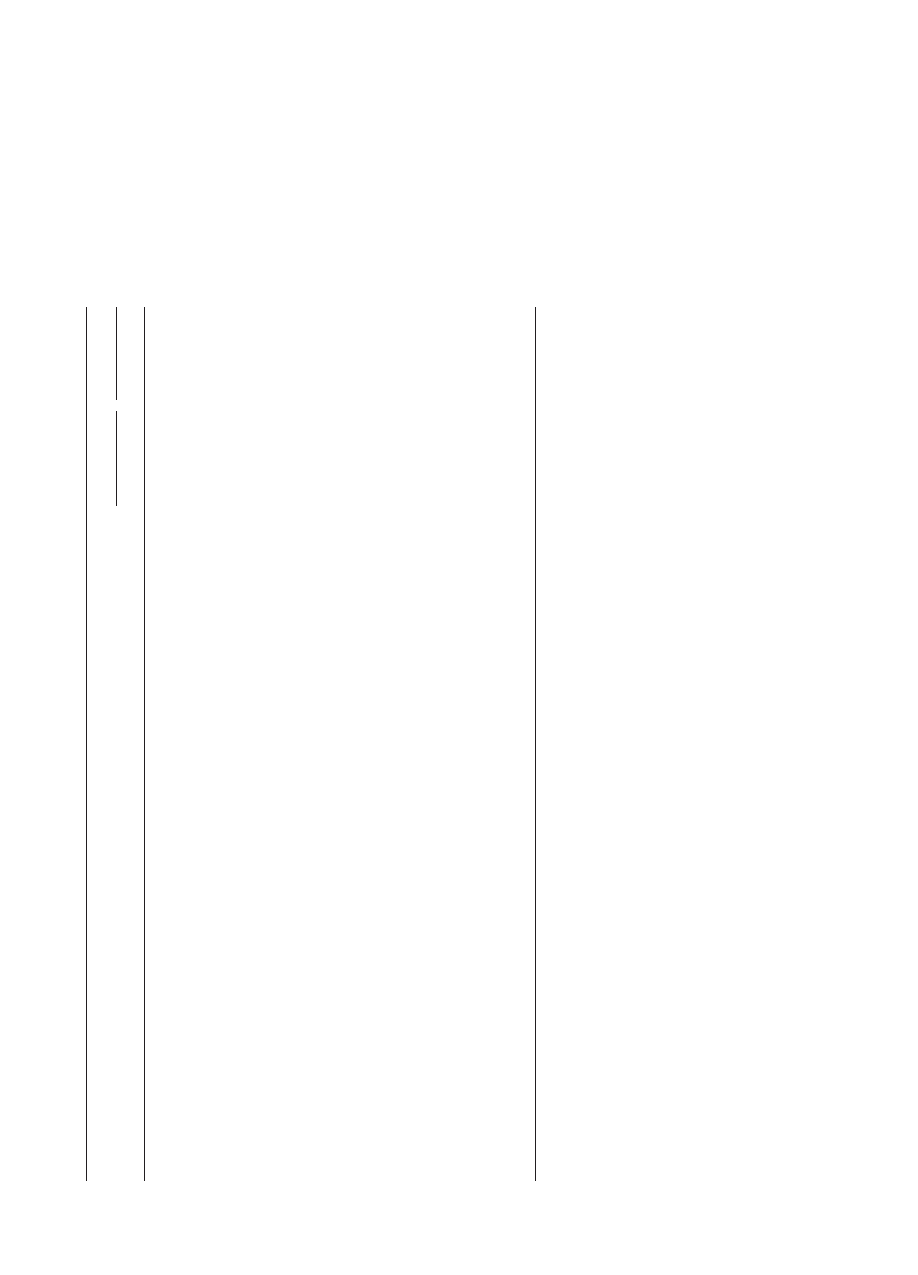

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, reliability estimates and correlations of main dependent

variables are presented in Table 1. In view of these results, it can be concluded that

all variables were assessed in a reliable way and that the various self-reports (e.g.

mood valence, activation, exhaustion, customer friendliness) and the various

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

701

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

T

able

1.

Means,

stand

ar

d

d

e

viations,

corr

elations

and

reliability

estimates

(in

par

enthesis)

of

central

variables

MS

D

1

2

3

4

5678

9

1

0

1

1

1

2

1

3

1.

Sex

1

.56

.49

(–)

2.

Age

29.84

9.93

.07

(–)

3.

P

erformance

(err

ors)

2.76

3.45

.16

2

.11

(1.0)

4.

IgA-I

(baseline)

23.64

12.33

2

.11

2

.06

2

.14

(–)

5.

Emotional

dissonance

2.08

.78

2

.18

2

.08

.05

.07

(.84)

6.

Mood

valence

3.28

.86

.22*

.06

2

.07

2

.16

2

.67**

(.77)

7.

Activation

3.10

.68

.05

2

.04

.06

.22*

.13

2

.26**

(.79)

8.

Tir

edness

2.54

.95

.03

2

.06

.15

.06

.29**

2

.36**

.34**

(.92)

9.

Customer

friendliness

3.43

1.25

.26**

.18

2

.23*

.04

2

.71**

.69**

2

.08

2

.28**

(.89)

10.

Smiling

17.42

12.07

2

.20

.13

2

.20*

2

.06

.02

.12

2

.19

.02

.04

(.91)

11.

Laughing

4.49

4.45

.04

.36**

2

.09

.01

2

.17

.26**

2

.04

2

.18

.30**

.17

(.91)

12.

T

alking

(seconds)

428

139

.30**

.12

.09

.03

2

.18

.29**

2

.01

2

.09

.26**

.03

.27**

(1.0)

13.

V

erbal

agr

eement

66.49

28.72

.29**

.29**

2

.20*

.06

2

.22*

.22*

.15

.00

.36**

.06

.26**

.50**

(.91)

14.

Non

verbal

agr

eement

9.31

10.27

2

.07

.15

2

.18

2

.15

2

.19

.23*

.02

.01

.21*

.30*

.06

.11

.09

(91)

Note

.

*

#

.05,

**

#

.01;

N

¼

94

–

9

6

due

to

single

missing

values;

1

male

¼

0,

female

¼

1.

702

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

behaviours of participants observed in this study (e.g. smiling, laughing, talking)

represent different phenomena.

Manipulation checks

Due to the random assignment of participants to experimental conditions, sex, age and

prior work experiences are not systematically linked to experimental factors (all p .

:10).

We conducted additional manipulation checks with respect to the impact of our

experimental procedures regarding time pressure and customer behaviour. Table 2

documents the related results. It was found, as expected, that communication times were

significantly shorter in conditions of time pressure (the comparison for vc vs. vc plus time

pressure is significant with tð90Þ ¼ 3

:67, p , :01). Moreover, time pressure was also

reported to be higher in corresponding conditions (this contrast is significant with

tð90Þ ¼ 2

:49, p , :01). Only 3 out of the 37 participants in both conditions with time

pressure did not earn a bonus. On an average, agents earned additionally 4.3e when serving

friendly customers and 4.1e when serving rude customers under time pressure. Overall,

these results clearly indicate that the manipulation to induce time pressure was effective.

The manipulation of customer behaviour did also work as expected (see Table 2) as

customers with rude behaviour were judged to be much less friendly than customers who

were polite (Fð1

; 90Þ ¼ 293:74, p , :01, h

2

¼

:75). Taken together, it can be concluded

that both experimental manipulations had strong main effects as predicted. The side-effects

of both manipulations (rude customer increase perceptions of time pressure; high time-

pressure enhances the perception of customer unfriendliness) were not problematic for

testing our hypotheses because no interaction was statistically significant.

Group comparisons for testing the hypotheses

To test the hypotheses, two MANOVAS were conducted. In the first MANOVA, salvia data

were analysed. In this analysis, the time of measurement was treated as a repeated

measurement factor in combination with both experimental factors (see Table 2). The

second MANOVA examined the remaining dependent variables (see Table 2). In both

MANOVAS, we used Helmert-contrasts for analysing the impact of the experimental

factor ‘communication condition’. This form of contrast is appropriate because it

compares (a) the first group (phone) to the remaining groups (the mean of both

vc-conditions; this reveals differences due to using a videoconference) and (b) the

second group (vc) to the last group (vc with time pressure; this reveals differences due

to time pressure). It should be noted that this form of contrast does not represent a post

hoc comparison as H2 and H3 require testing exactly these differences

1

. In addition, the

overall F-value of the factor ‘communication mode’ or the F-value of the interaction

between both experimental factors is not a valid test of hypotheses in this design as this

value is an average of both underlying group contrasts (phone vs. both vc-conditions and

vc vs. vc with time pressure). Therefore, these F-values are not reported.

1

It can be argued that for some tests solely the conditions phone vs. vc should be compared (thereby loosing statistical power

but being strict with excluding potential effects of time pressure that were only present within vc-conditions). Therefore, we

conducted two additional MANOVAs without the condition VC þ time pressure. The findings are almost identical with two

exceptions. There is (a) no longer a significant decrease in IgA from time 2 to time 3 (p ,

:22) and (b) the increase in showing

verbal agreement due to using a vc becomes significant with Fð1

; 58Þ ¼ 4:35, p , :04). As these differences are minor and

understandable, we solely present the results based on the Helmert contrasts.

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

703

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

T

able

2.

Manipulation

checks,

salivar

y

IgA,

experimenter

obser

vation

and

self-r

epor

t

Phone

friendly

Phone

rude

VC

friendly

VC

rude

VC

þ

time

friendly

VC

þ

time

rude

Communication

1

Interaction

1

M

(SD

)

M

(SD

)

M

(SD

)

M

(SD

)

M

(SD

)

M

(SD

)

C

ustomer

beha

viour

1

P-VC

VC-VC

þ

P-VC

VC-VC

þ

Manipulation

checks

Communication

(seconds)

912

(135)

872

(163)

986

(208)

996

(162)

840

(97)

863

(129)

3.67**

Time

pr

essur

e

.71

(.87)

1.67

(.96)

.49

(.45)

1.75

(.96)

1.37

(1.15)

2.06

(.99)

24.6**

2.49**

Customer

friendliness

4.70

(.35)

2.28

(.94)

4.68

(.30)

2.45

(.76)

4.18

(.57)

2.33

(.50)

293.7**

2.12*

Salivar

y

IgA-le

vels

(mg/dl)

2

IgA-I

22.4

(13.6)

23.6

(8.9)

22.6

(12.5)

18.5

(8.7)

28.0

(17.2)

24.7

(9.6)

2.16*

3

IgA-II

32.1

(22.9)

30.7

(.96)

27.1

(11.9)

23.3

(17.4)

36.4

(24.2)

31.6

(22.0)

1.79

þ

3

IgA-III

30.5

(20.0)

27.6

(15.2)

25.4

(15.9)

20.6

(8.4)

28.4

(11.6)

25.9

(14.7)

Obser

vation

and

Self-Report

P

erformance

(err

ors)

1.62

(1.7)

3.94

(5.1)

2.47

(4.4)

4.56

(3.6)

1.12

(1.2)

2.94

(1.9)

9.41**

1.79

þ

Emotional

dissonance

1.39

(.44)

2.65

(.70)

1.38

(.35)

2.62

(.65)

1.92

(.51)

2.49

(.69)

76.38**

2

2.31*

Mood

valence

3.94

(.75)

2.69

(.54)

4.13

(.66)

2.85

(.56)

3.53

(.67)

2.58

(.53)

82.11**

2.78**

Activation

2.65

(.80)

3.09

(.45)

3.27

(.76)

3.07

(.65)

3.39

(.69)

3.17

(.52)

2

2.46*

2

2.31*

Tir

edness

1.86

(.86)

2.83

(.94)

2.50

(1.1)

2.69

(.64)

2.51

(.94)

2.88

(.91)

7.47**

Smiling

14.4

(11.1)

14.7

(10.8)

18.9

(13.3)

20.1

(11.2)

18.6

(14.7)

18.2

(11.2)

2

1.67

þ

Laughing

6.06

(4.5)

3.44

(.4.5)

5.40

(4.3)

3.33

(3.9)

5.35

(5.1)

3.31

(3.9)

6.09*

T

alking

(seconds)

461

(153)

387

(119)

520

(171)

452

(143)

391

(107)

369

(90)

3.97*

3.14**

V

erbal

agree

ment

70.3

(20.9)

49.9

(19.7)

87.4

(33.5)

58.0

(17.9)

72.9

(36.5)

60.7

(25.9)

14.04**

2

1.66

þ

Non

verbal

agr

eement

13.4

(10.7)

3.5

(3.9)

11.7

(12.8)

9.5

(11.5)

9.0

(9.6)

8.9

(9.6)

3.95*

1.99*

Notes

.

P-VC

¼

Helmer

t

contrast

phone

vs.

mean

of

both

vc-conditions;

VC-VC

þ¼

Helmert

contrast

vc

vs.

vc

plus

time

pr

essur

e;

*p

,

:05,

**

p

,

:01;

1

Significant

F-values

ar

e

p

resented

for

the

experimental

factor

‘customer

beha

viour’

and

significant

t-values

ar

e

shown

for

Helmert

contrasts

(P-VC

and

VC-VC

þ

);

2

N

¼

92

due

to

single

missing

saliva

data,

time

1

vs.

time

2/time

3

F

ð1

;

86

Þ¼

11

:53

**

h

2

¼

:12,

time

2

vs.

time

3

F

ð1

;

86

Þ¼

6:

12

**

,h

2

¼

:07;

3

These

effects

relate

to

the

single

time

of

measur

ement:

if

time

1

and

time

2

ar

e

consider

ed

simultaneously

the

contrast

is

significant

with

tð

87

Þ¼

2:

15,

p

,

:03.

704

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Test of H1

This hypothesis concerns the impact of customer behaviour on the intensity of

emotions, strain and behaviour of agents. It was expected (H1a) that compared with

friendly customers, the behaviour of unfriendly customers leads to more intense

emotions and strain. This hypothesis is corroborated by the data with respect to the

variables mood valence, tiredness and emotional dissonance (see Table 2). However,

the self-reported degree of activation and IgA-levels were not systematically increased by

the unfriendliness of customers. This is probably due to the fact that both variables are

rather broad, unspecific measures of activation (arousal) that do not always differentiate

between positive and negative stimuli. We come back to this point.

In support of H1b, it was found that the friendliness of the service and the

performance quality of agents (defined as errors in adhering to the communication

script) were significantly lower if customers were unfriendly. Participants talked less,

laughed less often and showed less verbal and non-verbal agreement when customers

were unfriendly. Only the frequency of smiling was not affected by this manipulation.

Taken together, this pattern of findings clearly indicates that unfriendly customer

behaviour increases strain and lowers task performance of agents.

Test of H2

This hypothesis focuses on potential effects linked to the experimental factor

‘communication condition’. The first part of this hypothesis (H2a) was not supported by

the data when compared with an audio interaction, the availability of video data did not

lead to more intensive emotions or more strain. There was no significant effect of the

corresponding Helmert-contrast (phone vs. mean of vc-conditions) for the IgA-level, for

emotional dissonance, for mood valence or feelings of tiredness. However, self-reported

activation levels are higher in both vc-conditions (see Table 2). As this effect is further

qualified by a two-way interaction indicating that higher activation levels induced by

videoconferencing are only found if customers are friendly, this result does not indicate

a potential disadvantage of using videoconferencing for communication with

customers. To the contrary, it could be argued that only seeing a friendly customer

increases activation and that this makes the otherwise often boring job of call centre

agents more interesting. We come back to this point in the discussion.

Hypothesis 2b focuses on potential differences with respect to the expression of

positive emotions (laughing, smiling, showing agreement). As documented in Table 2, this

hypothesis found some support in the data. Adding video data in conversations with

customers did not change the frequency of laughing of participants, but it increased the

frequency of smiling and the frequency of showing verbal agreement with customers.

The observed differences are in the predicted direction with a near miss of statistical

significance (p

, .10, see also Footnote 1). With respect to showing non-verbal

agreement, a significant interaction of experimental factors was found. Non-verbal

agreement (nodding) was more often observed in vc-communication when compared

with conversations via phone but this difference is only found if customer behaviour was

rude. Therefore, it is likely that this type of behaviour was deliberately used by participants

in vc-conditions to calm down aggressive customers. Taken together, H2b found some

support in this study. There is evidence, as expected, that the specific communication

condition changes the expression of positive emotions and behaviour indicating

agreement with another person. However, these effects were not very strong and/or

depend on the presence of some other conditions (having to talk to rude customers).

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

705

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Test of H3

With respect to the manipulation of time pressure (H3a), it was expected that adding time

pressure in a videoconference leads to higher strain of agents and less talking with

customers. This part of the hypothesis is supported by the data as talking was reduced in

these conditions (see Table 2) and IgA-levels were also significantly higher in conditions

with time pressure. This was already the case at sampling point 1 (tð88Þ ¼ 22

:16,

p ,

:04, see Table 2). The further results regarding IgA-levels indicate that the whole

simulation of call centre work was taxing for participants. IgA-levels significantly

increased from baseline to sampling point 2 (Fð1

; 86Þ ¼ 11:53, p , :01, h

2

¼

:12) and

decreased significantly at the end of the experiment (Fð1

; 86Þ ¼ 6:11, p , :02, see also

Footnote 1), probably because participant’s tension was reduced when the experiment

was finished. An additional MANOVA that examined solely IgA-levels from time 1 and time

2 (where strain should be induced by experimental manipulations) once again revealed

that the condition with time pressure caused the largest IgA efflux (see Table 2). It should

be noted that inducing time pressure within a videoconference further had a marginally

significant impact on performance (agents made fewer errors) and also changed the mood

of agents (the mood was less positive under high time-pressure; see Table 2). The second

part of H3 relates to potential interactions between customer friendliness and time

pressure. It was expected that the negative effect of time pressure on strain is amplified if

customers are rude. This idea is not supported by the results as there was no

corresponding interaction (vc vs. vc plus time pressure) for IgA-levels, mood valence or

tiredness. However, there is a significant interaction for emotional dissonance (Table 2).

Interestingly, if agents can see friendly customers, time pressure leads to higher

emotional dissonance. One possible explanation is the following: if agents want to hurry-

up in order to keep a time limit, friendly customers are most problematic because agents

have to suppress sympathy for these customers and motivation to talk with them.

Discussion

Computer-mediated communication within- and between-organizations becomes more

and more common. Therefore, researchers have started to analyse the various factors

that make this type of communication different from traditional forms of

communication. The purpose of our study was to contribute to this research by

investigating if and how the work of call centre agents and the immediate impact of this

work on well-being of agents are changed if communication with customers is

conducted via videoconference. In analysing this issue, we attempted to construct an

ecologically valid simulation of this work with experienced call centre agents and

examined not only the impact of adding video data but also the effect of two further

common stressors in call centres: the presence of time pressure and verbal aggressions

towards agents. The results of our experiment are important in several ways.

First, we were able to demonstrate that inducing time pressure in communication

with customers raised IgA-levels in salvia. Moreover, talking-times were reduced, mood

of agents was less positive and there was also a marginally significant effect regarding

performance of agents as fewer errors were made under high time-pressure. Taken

together, all these differences show that agents focused their attention on the task and

were aroused by the underlying manipulation. This finding might be interpreted as

evidence that corresponding goals of management in call centres (e.g. to have a fast,

high-quality service) can be achieved by offering financial incentives to agents for

706

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

serving customers quickly. However, we did not measure customer satisfaction because

no real customers were involved in our study. In addition, time pressure was solely

induced in conditions where agents had a videoconference as we were interested to

examine the potential additive effects of both manipulations when agents and customer

can see each other. Therefore, drawing the conclusion that inducing time pressure will

increase performance of agents or customer satisfaction in typical call centre work is

not warranted. Moreover, we should also note that the moods of agents were negatively

affected and customers were experienced to be more unfriendly in our study if time

pressure was high. While acute time pressure increases IgA and might improve attention

and performance, it can also lead to chronic stress and lower IgA-levels in the long run

(Henningsen et al., 1992; Kugler, 1994). In this case, the immune system’s integrity is

threatened and the susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections is enhanced

( Jemmott & McClelland, 1989; Schaubroeck, Jones, & Xie, 2001) with a higher

probability of non-productive times of agents. In view of these findings, we propose that

more research on the long-term health costs of time pressure in call centre work is

needed. This should involve more than one physiological measure used in the reported

experiment, especially as IgA can be seen as both, a measure of acute arousal in the short

term and an index of immune system integrity in the long run.

Second, we found in support of recent theories of emotion work (Dormann & Zapf,

2004; Grandey, 2000; Zapf, 2002) that customer behaviour has to be considered a

stressor in call centre work. There were several substantial effects linked to the

manipulation of customer behaviour and all of these findings indicate that compared

with friendly customers, rude customer behaviour promotes strain (e.g. bad mood,

emotional dissonance) and reduces well-being of agents. It was also found that the

customers have to pay for their aggression with a lower quality of service by the agent.

The only point that seems to contradict this consistent pattern of findings is that IgA-

levels and self-reports of activation were not raised if customers were rude. However,

these measures mainly indicate unspecific arousal. Prior research has documented that

IgA-levels correlate with the actual and perceived workload (Zeier, Brauchli, & Joller-

Jemelka, 1996) but not necessarily with the specific emotional state (Endresen et al.,

1991). Therefore, this deviation is understandable and does not contradict the general

conclusion that unfriendly customers are considerable stressors in call centre work.

Third and most importantly, we found contrary to our expectations that the availability

of video data did not simply enhance strain of agents. There was no single main effect in the

data indicating that establishing a videoconference between agents and customers is more

taxing for agents than having a phone-to-phone connection only. In other words, hearing a

rude (polite) customer is as effective in annoying (pleasing) call centre agents as hearing

and seeing the customer in the same situation. The total absence of any strong negative

effects of the availability of video data is surprising. Perhaps, we simply underestimated the

power of the spoken word in eliciting emotional reactions. No effects of visual information

were also found by O’Malley, Langton, Anderson, Doherty-Sneddon, and Bruce (1996) for

the performance of dyads working on a problem-solving task, by Harmon, Schneer, and

Hoffman (1995) in a comparison of group decisions derived ftf or via audioconference, and

also by Day and Schneider (2002) in investigating the effect of a medical treatment in a field

study. Consistent with these findings, there is also evidence that anonymity does not always

make the interaction less social (e.g. see Postmes & Spears, 2002). Therefore, a strong and

simple link between the media used for communication and the strain that might result in

this situation is probably not existent. The only disadvantage of having video data observed

in our study was that emotional dissonance might be increased if time pressure is high and

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

707

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

customers are polite. Emotional dissonance linked to suppressing or overplaying positive

emotions is only recently discussed in research on emotional labour (see Glomb & Tews,

2004; Wegge, van Dick, & Wecking, 2006). The preliminary evidence regarding this

phenomenon shows that this form of emotional dissonance is less problematic for the well-

being of service providers. However, as discussed in more detail in the next section, we

believe that replications of these results are needed before it is concluded that there are no

negative effects of videoconferencing in call centre work. Extending this database could be

very fruitful as the data of our study also show that videoconferencing increased activation if

customers were friendly. Higher levels of activation can counteract boredom, a common

problem in call centre work. In addition, smiling to customers and showing verbal

agreement tended to be more pronounced in a videoconference. As customers often prefer

to see service providers (Finn et al., 1997; Wegge & Bipp, 2004) and because the social

presence of agents should be increased in a videoconference, adding videoconference

facilities in call centres could be an option for both enriching this type of work and making it

more effective if the absence of negative effects is confirmed in future studies.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that might be addressed in further research. First, it

should be noted that we simulated call centre work in a laboratory. While conducting a

study in a laboratory, context has several advantages (e.g. a precise analysis of differences

in customer behaviour and communication procedures, the use of various measures) and

also has limitations. We do not know, for example whether the phenomena examined in a

short-term setting like this can be generalized to behaviour of employees at the workplace

where work is organized in 8-hour shifts. However, the participants in our study were

experienced call centre agents. Moreover, the experimental procedures were designed to

simulate call centre work in a realistic context with typical tasks and manipulation checks

indicated that these procedures were effective. In addition, during debriefing, the

experimenter always asked how realistic participants judged the simulated scenario.

Almost all call centre agents attested this simulation a high degree of realism (e.g. with

respect to the type of talks, the presence of scripted communication and the

corresponding computer program). However, five agents mentioned during debriefing

that customers are typically not so friendly and three agents mentioned that customers are

typically not so unfriendly. Therefore, the sequence of calls we used in our simulation was

indeed somehow untypical. However, 88 agents did not mention this point. Moreover, we

decided to keep this factor constant within agents as many other problems arise (e.g.

sequence effects) if a more variable order of friendly and unfriendly customers is used. Of

course, it would be interesting to conduct further studies in which more complex

sequences of friendly and unfriendly customer behaviour are enacted (e.g. in an

experiment) or observed (e.g. in field studies).

Second, it should be noted that we videotaped the behaviour of all participants in

this study with a distant camera. The visible camera on top of the computer screen was

used only in the vc conditions and there is evidence for the effectiveness of this

manipulation (e.g. agents felt and behaved differently with or without this camera).

However, it is not clear how the level of self-awareness and the behaviour of agents were

influenced by the constant availability of the distant camera. Therefore, further studies

without this limitation might be interesting, in particular, if additional measures with

respect to the degree of self-awareness are assessed, too.

708

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Third, we should be also aware that potentially influential factors for strain reactions

of agents were not manipulated, for example technical parameters of the

videoconference, such as the bandwidth of data transfer, the size of the picture of the

customer, the availability of the own picture of agents or the occurrence of technical

problems that are still a common problem in videoconferences (see for example Wegge,

2006). Future research should address also this lacuna by examining the impact of these

factors. In the same vein, we should note that participants were not familiar with

videoconferencing. Even though the experimenter explained the system and no

problems did occur during communication with customers’ reactions will probably

change with more experience in the use of this new communication technology (see

Webster, 1998, for a field study on this issue). Further studies should consider this and

other limitations (e.g. effects of inducing time pressure in phone-to-phone

communication with customers were not investigated).

Finally, we like to encourage practitioners as well as researchers to examine the

impact of videoconferencing in the regular work of call centre agents as there is now

first empirical evidence that adding video data in this type of work can have advantages.

In our study, there was no evidence for the problematic effects that we expected to find,

for example more strain due to the mere availability of video data or a substantial

enhancement of cumulative effects of stressors (e.g. if aggressive customers had to be

served under high time-pressure). It also remains open whether similar results will be

found if inter-individual differences in the personality of agents are considered. Based on

the research of Workman, Kahnweiler, and Bommer (2003) it can be expected, for

example that communication via videoconference is preferred more by individuals with

an external and global cognitive style.

Our study indicated that adding a videoconference in the routine work of call centre

agents seems to be rather a cure than a curse for most agents. Of course, there are many

other possibilities to increase work motivation and well-being in call centres, for

example by utilizing the motivating potential of work and organizational identification

(Holman, 2003; Wegge, van Dick, Fisher, Wecking, & Moltzen, 2006), by improving the

(interaction) control of agents (Zapf, 2002), or – and this statement is based on a study

with data from 2,091 agents working in 85 call centres in the UK – by promoting a

positive work climate (e.g. supervisory support, autonomy, participation of agents) and

reducing work overload (Wegge, van Dick, Fisher, West, & Dawson, 2006).

Nevertheless, offering videoconferencing in call centres might prove to be a new,

additional improvement. A promising way to examine this question further with little

risk would be to offer agents the choice to communicate with customers also via

videoconference.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation (WE 1504/7-1). We

are grateful to Rolf van Dick, Kevin Daniels and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments

on earlier versions of this paper.

References

Blokland, A., & Anderson, A. H. (1998). Effect of low frame-rate video on intelligibility of speech.

Speech Communication, 26, 97–103.

Customer-induced stress in call centre work

709

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Bristow, M., Hucklebridge, F. H., Clow, A., & Evans, P. D. (1997). Modulation of secretory

immunoglobulin A in salvia in relation to an acute episode of stress and arousal. Journal of

Psychophysiology, 11, 248–255.

Bruce, V. (1996). The role of face in communication: Implications for videophone design.

Interacting with Computers, 8, 166–176.

Day, S. X., & Schneider, P. L. (2002). Psychotherapy using distance technology: A comparison of

face-to-face, video, and audio treatment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 499–503.

Deery, S., Iverson, R., & Walsh, J. (2002). Work relationships in telephone call centers:

Understanding emotional exhaustion and employee withdrawal. Journal of Management

Studies, 39, 471–496.

Dormann, C., & Zapf, D. (2004). Customer-related social stressors and burnout. Journal of

Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 61–82.

Endresen, I. M., Ellertsen, B., Endresen, C., Hjelman, A. M., Matre, R., & Ursin, H. (1991). Stress at

work and psychological and immunological parameters in a group of Norwegian female bank

employees. Work and Stress, 5, 217–227.

Evans, P., Bristow, M., Hucklebridge, F., Clow, A., & Pang, F. Y. (1994). Stress, arousal, cortisol and

secretory immunoglobulin A in students undergoing assessment. British Journal of Clinical

Psychology, 33, 575–576.

Evans, P., Clow, A., & Hucklebridge, F. (1997). Stress and the immune system. Psychologist July,

303–307.

Finn, K. E., Sellen, A. J., & Wilbur, S. B. (1997). Video-mediated communication. Mahwah:

Erlbaum.

Fischbach, A. (2003). Determinants of emotion work. Available at: http://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/

diss/2003/fischbach/fischbach.pdf [25.11.2003].

Glomb, T. M., & Tews, M. J. (2004). Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 1–23.

Grandey, A., Dickter, D., & Sin, H. -P. (2004). The customer is not always right: Customer verbal

aggression toward service employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 397–418.

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize

emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 95–110.

Hagemann, T., Vogt, J., Mauss, I., & Kalveram, K. Th. (2000). Circadian rhythm of salvary

immunoglobulin A. Journal of Psychophysiology, 14, 186.

Harmon, J., Schneer, J. A., & Hoffman, L. R. (1995). Electronic meetings and established decision

groups: Audioconferencing effects on performance and structural stability. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 61, 138–147.

Henningsen, G. M., Hurrell, J. J., Baker, F., Douglas, C., MacKenzie, B. A., Robertson, S. K., et al.

(1992). Measurement of salivary immunoglobulin A as an immunologic biomarker of job

stress. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment, and Health, 18, 133–136.

Holman, D. (2003). Call centres. In D. Holman, T. D. Wall, C. W. Clegg, P. Sparrow, & A. Howard

(Eds.), The new workplace: A guide to the human impact of modern working practices

(pp. 115–134). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Jemmott, J. B., & McClelland, D. C. (1989). Secretory IgA as a measure of resistance to infectious

disease. Behavioral Medicine, 15, 63–71.

Klußmann, A., Gebhardt, H., Mu

¨ller, B. H., Maßbeck, P., Topp, S., Steinberg, U.,

et al. (2005).

Gestaltung gesundheitsfo

¨rderlicher Arbeitsbedingungen fu

¨r Rettungsdienstpersonal. [Health

promoting work conditions for paramedics]. Notfall and Rettungsmedizin, 8, 564–568.

Kugler, J. (1990). Filminduzierte A

¨nderung der emotionalen Befindlichkeit und Immunglobulin

A im Speichel. [Video-induced changes of emotional state and immunoglobulin A in saliva ].

Dissertation: Heinrich-Heine-Universita

¨t Du

¨sseldorf.

Kugler, J. (1994). Stress, salivary immunoglobulin A and susceptibility to upper respiratory tract

infection. Evidence for adaptive immunomodulation. Psychologische Beitra

¨ge, 36, 175–182.

Mancini, G., Carbonara, A. O., & Heremans, J. F. (1965). Immunochemical quantitation of antigens

by single radial immunodiffusion. Immunochemistry, 2, 235–254.

710

Ju¨rgen Wegge et al.

Copyright © The British Psychological Society

Reproduction in any form (including the internet) is prohibited without prior permission from the Society

Meier, C. (2000). Videokonferenzen [Videoconferencing]. In M. Boos, K. J. Jonas, & K. Sassenberg

(Eds.), Computervermittelte kommunikation in organisationen (pp. 153–164). Go

¨ttingen:

Hogrefe.

Olson, G. M., & Olson, J. S. (2003). Human-Computer Interaction: Psychological aspects of the

human use of computing. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 491–516.

O’Malley, C., Langton, S., Anderson, A., Doherty-Sneddon, G., & Bruce, V. (1996). Comparison of

face-to-face and video-mediated interaction. Interacting with Computers, 8, 177–192.

Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2002). Behavior online: Does anonymous computer communication

reduce gender inequality? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1073–1083.

Purdy, M. J. (2000). The impact of communication media of negotiation outcomes. International

Journal of Conflict Management (online), 11, 162, 26p.

Schaubroeck, J., Jones, J. R., & Xie, J. L. (2001). Individual differences in utilizing control to cope

with job demands: Effects on susceptibility to infectious disease. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 86, 265–278.

Schimmak, U. (1999). Strukturmodelle von Stimmungen: Ru

¨ckschau, Rundschau und Ausschau.

[Structural models of mood: A review and outlook]. Psychologische Rundschau, 50, 69–89.

Short, J. A., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunication. New

York: Wiley.

Tanis, M. (2003). Cues to identity in CMC. The impact on person perceptions and subsequent

interaction outcomes. University of Amsterdam: Ipskamp.

Taylor, P., & Bain, P. (1999). An assembly line in the head: Work and employee relations in the call

centre. Industrial Relations Journal, 30, 101–117.

Tice, D. M., & Bratslavsky, E. (2000). Giving in to feel good: The place of emotion regulation in the

context of general self-control. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 149–159.

Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2003). Emotion regulation in customer service roles: Testing a model

of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 55–73.

Tschan, F., Rochat, S., & Zapf, D. (2005). It’s not only clients: Studying emotion work with clients

and co-workers with an event-sampling approach. Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 78, 195–220.

Tzai-Li, L., & Gleeson, M. (2004). The effect of single and repeated bouts of prolonged cycling and

circadian variation on saliva flow rate, immunoglobulin A and

a-amylase responses. Journal of

Sports Sciences, 22, 1015–1024.

Vogt, J. (1998). Psychophysiologische Beanspruchung von Fluglotsen [Psychophysical strain of

air traffic controller]. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Dortmund, Germany.

Wallbott, H. G. (1998). Decoding emotions from facial expression: Recent developments and

findings. European Review of Social Psychology, 9, 191–232.

Webster, J. (1998). Desktop videoconferencing: Experiences of complete users, wary users and

non-users. MIS Quarterly, September, 257–286.

Wegge, J. (2006). Communication via videoconference: Emotional and cognitive consequences of

affective personality dispositions, seeing one’s own picture and disturbing events. Human

Computer Interaction, 21, 273–318.

Wegge, J., & Bipp, T. (2004). Videokonferenzen in Organisationen: Chancen, Risiken und

personalpsychologisch relevante Anwendungsfelder [Videoconferences in organizations

Chances, risks and relevant applications for personnel psychology]. Zeitschrift fu

¨r

Personalpsychologie, 3, 95–111.

Wegge, J., Bipp, T., & Kleinbeck, U. (2007). Goal setting via videoconference. European Journal

of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16, 169–194.

Wegge, J., van Dick, R., Fisher, G. K., Wecking, C., & Moltzen, K. (2006). Work motivation,