P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Motivation and Emotion, Vol. 26, No. 1, March 2002 (

C

°

2002)

The Effects of Performance Monitoring

on Emotional Labor and Well-Being

in Call Centers

David Holman,

1

,2

Claire Chissick,

1

and Peter Totterdell

1

A study was conducted to investigate the relationship between performance moni-

toring and well-being. It also examined a mechanism, namely emotional labor,

that might mediate the relationship between them, assessed the effect of the work

context on the relationship between performance monitoring and well-being, and

examined the relative effects of performance monitoring and work context on

well-being. Three aspects of performance monitoring were covered, namely, its

performance-related content (i.e., immediacy of feedback, clarity of performance

criteria), its beneficial-purpose (i.e., developmental rather than punitive aims),

and its perceived intensity. The participants were 347 customer service agents in

two U.K. call centers who completed a battery of questionnaire scales. Regression

analyses revealed that the performance-related content and the beneficial-purpose

of monitoring were positively related to well-being, while perceived intensity had

a strong negative association with well-being. Emotional labor did not mediate

the relationship between monitoring and well-being in the form hypothesized,

although it was related to these two factors. Work context (job control, problem

solving demand, supervisory support) did not mediate the relationship between

monitoring and well-being, but job control and supervisory support did moderate

the relationship between perceived intensity and well-being. Relative to other

study variables, perceived intensity showed stronger associations with emotional

exhaustion, while job control and supervisory support tended to show stronger

1

Institute of Work Psychology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, United Kingdom.

2

Address all correspondence to David Holman, Institute of Work Psychology, University of Sheffield,

Sheffield S10 2TN, United Kingdom; e-mail: d.holman@sheffield.ac.uk. The support of the Economic

and Social Research Council (ESRC) (U.K.) is gratefully acknowledged. The work was part of the

programme of the ESRC Centre for Organization and Innovation.

57

0146-7239/02/0300-0057/0

C

°

2002 Plenum Publishing Corporation

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

58

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

associations with depression and job satisfaction. Implications for theory, practice,

and future research are discussed.

KEY WORDS: performance monitoring; emotional labor; well-being; stress; call centers; customer

service.

A wide range of job, organizational, and environmental factors has been identi-

fied as antecedents of affect and well-being at work. One organizational factor

that has received less attention than most is performance monitoring. Performance

monitoring can be defined as those practices that involve “the observation, exami-

nation, or recording of employee work related behaviors (or all of these), with and

without technological assistance” (Stanton, 2000, p. 87). To its advocates, per-

formance monitoring enables the organization to monitor and improve employee

performance, to reduce costs and to ensure customer satisfaction (Alder, 1998;

Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989). Employees are thought to benefit because they can

receive accurate and timely feedback, have their performance recognized and as-

sessed fairly, improve their performance and develop new skills (Grant & Higgins,

1989). It has also been suggested that well-being is improved by, for example, de-

riving satisfaction from the knowledge of one’s improved performance and from

being better able to cope with work demands (Aiello & Shao, 1993; Bandura, 1997;

Hackman and Oldham, 1976; Stanton, 2000). To its critics, performance monitor-

ing is intrinsically threatening to employees because the information gained may

adversely affect employees’ remuneration or their relationship with coworkers

(Alder, 1998). Monitoring is also considered to intensify employees’ workload

and to increase the level of work demands (Smith, Carayon, Sanders, Lim, &

LeGrande, 1992). The threat of monitoring and the high level of demand are

thought to impact negatively on employee well-being.

There are, however, relatively few studies of performance monitoring as an

antecedent of affect and well-being, although existing studies do suggest a link to

employee stress (Aiello & Kolb, 1995; Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989; Smith et al.,

1992). This lack of research seems surprising given that performance monitoring is

widely used by organizations. Indeed, in 1992 it was estimated that 26 million U.S.

workers were monitored electronically

3

(Nussbaum, 1992; Ross, 1992) and that

between 1990 and 1992 approximately 70,000 U.S. companies spent $500 million

on monitoring software (Bylinsky, 1991; Halpern, 1992). Moreover, it is likely

that the number of employees being monitored has increased in the last 10 years.

One reason for this is the greater use and availability of technologies that make

performance monitoring easier and more viable (e.g., monitoring software, just-in-

time systems, total quality management systems, Waterson et al., 1997). Another

3

This does not include those monitored through nonelectronic means and thus the overall total is likely

to be higher.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

59

reason is the growth of call centers.

4

In call centers, performance monitoring

occurs through the continuous electronic monitoring of quantitative performance

indicators such as length of call, number of calls, and amount of time logged on

and off the system. In addition, a call can be listened to or recorded remotely (with

or without the employee’s knowledge) in order to assess its quality. Performance

monitoring is thus a highly prominent and pervasive feature of everyday life in call

centers. Indeed, the pervasiveness of performance monitoring in call centers has

led to them being labelled as “electronic panopticans” (Fernie and Metcalf, 1998);

it also makes call centers an excellent location in which to study performance

monitoring.

Despite the prominence and pervasiveness of performance monitoring in call

centers, very little research has been conducted in to its effects (Chalykoff &

Kochan, 1989, Smith et al., 1992). Furthermore, only a handful of studies have

focused on how different aspects of performance monitoring might relate to well-

being (Stanton, 2000), and these studies have generally examined the content of

monitoring (e.g., type, frequency, feedback processes) rather than other aspects of

monitoring (e.g., its purpose or perceived intensity). Research has also tended to

use global measures of stress (e.g., feeling stressed or not, Aiello & Kolb, 1995)

or measures of satisfaction (Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989). Few studies have used

well-validated measures of well-being that reflect the diverse ways in which affect

can be experienced, for example, anxiety, depression, or emotional exhaustion

(Smith et al., 1992). Another weakness of the performance monitoring literature

is that field studies have rarely, if ever, addressed the mechanisms that might link

performance monitoring to well-being. Finally, there have been few attempts to

assess the joint effects of monitoring and contextual factors (e.g., job control, job

demand, social support) on well-being or to assess the importance of monitoring

relative to other contextual factors (Carayon, 1994).

The purpose of the present study was to address these issues. Specifically, this

study had the following four aims. The first aim was to examine the relationship

between the nature, purpose and intensity of performance monitoring, and vari-

ous measures of employee well-being in a call center environment. The second

aim was to examine one mechanism that might mediate the relationship between

performance monitoring and well-being in a service context, namely, emotional

labor. The third aim was to examine the joint effects of performance monitoring

and contextual variables on employee well-being. The final aim was to examine

the relative importance of performance monitoring and contextual variables with

regard to well-being.

4

For example, call centers currently employ approximately 2% of the U.K. working population, which

is a rise from 1% in the mid 1990’s (Fernie & Metcalf, 1998). Although call centers vary in size

and purpose, central to all call centers are information technologies that integrate call management

systems with VDU technologies and customer data bases. This enables incoming and outgoing calls

to be easily distributed to available staff, as well as enabling information (e.g., customers’ details) to

be instantly accessed or inputted (or both).

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

60

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

PERFORMANCE MONITORING

As noted, performance monitoring involves the observation, examination,

and recording of employee work behaviors (Stanton, 2000). Within organizations

it also normally involves feedback processes—although feedback is not necessar-

ily an aspect of monitoring. Performance monitoring has also been conceptualized

as existing in both “traditional” and “electronic” forms.

5

Traditional forms, such

as direct observation, listening to calls, work sampling, and self-report, tend to

be episodic and collect both qualitative and quantitative data. Electronic perfor-

mance monitoring involves the automatic and remote collection of quantitative

data (e.g., key strokes, call times). It also permits the continuous monitoring of

performance.

Traditional and electronic forms of performance monitoring vary according

to a range of characteristics (Carayon, 1993; Stanton, 2000). These characteristics

can be clustered into two main groups, namely, content and purpose. The “content”

of performance monitoring covers the more “objective” qualities of the monitoring

process. It includes: frequency (e.g., is it continuous or episodic, its regularity);

feedback (e.g., how data is fed back, how often it is fed back); performance cri-

teria (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, clarity); source (e.g., who or what collects the

data); and target (e.g., is monitoring at an individual or group level, which task is

monitored). The “purpose” of performance monitoring covers the uses to which

the performance data is put. For example, is the data used for punitive purposes,

developmental purposes, or to inform reward and payment decisions? In addi-

tion to content and purpose, performance monitoring research has highlighted a

third factor, “monitoring cognitions” (Stanton, 2000). This factor covers employee

perceptions of monitoring and includes attitudes toward monitoring (e.g., is it an

invasion of privacy), assessments of its fairness and whether the monitoring system

is trusted (Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989; Niehoff & Moorman, 1993). The perceived

intensity of monitoring has also been suggested as an important monitoring cog-

nition, but as yet it has not been studied empirically (Stanton, 2000).

PERFORMANCE MONITORING AND WELL-BEING

In laboratory and field studies, monitored employees (or participants) are

generally found to have higher levels of stress and dissatisfaction than nonmoni-

tored employees (Aiello et al., 1991; Aiello & Kolb; 1995, David & Henderson,

2000; Irving, Higgins, & Safeyeni, 1986).

6

In one of the more comprehensive

field studies, Smith et al. (1992) compared monitored and nonmonitored employ-

ees. Monitored employees reported higher levels of boredom, depression, anxiety,

anger, and fatigue.

5

While not ideal labels, we keep them as they are used by others in this field (e.g., Stanton, 2000).

6

One exception is the study by Nebeker and Tatum (1993), which found no difference.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

61

Other studies have focused on the relationship between various characteristics

of performance monitoring and well-being. Carayon (1994), in a reanalysis of the

Smith et al. (1992) data, focused on 14 performance monitoring characteristics. Of

the 14 measures, only two had a consistent relationship with employee stress. First,

if employees thought that performance monitoring presented a good picture of their

work to management, it was negatively associated with depression, anger, fatigue,

and job dissatisfaction. Second, if an employee’s performance data was compared

to other employees’ data, there was a positive association with depression, anger,

and fatigue. It is interesting to note that anxiety was not associated with any per-

formance monitoring characteristic. In a study of performance monitoring in a call

center, Chalykoff and Kochan (1989) found a positive relationship between job

satisfaction and the immediacy of feedback, clear rating criteria and whether the

feedback was positive. Like Carayon (1994), they too found no relationship with the

frequency of monitoring. They also found no relationship to attitudes about moni-

toring, such as whether it was an invasion of privacy or a good tool if used properly.

From the above it is apparent that, while being monitored is more stressful

than not being monitored, there is little evidence to indicate exactly what it is about

being monitored that makes it so much more stressful than not being monitored. The

strongest evidence suggests that feedback can have positive effects on well-being.

This contradicts any suggestion that monitoring produces only negative effects.

Given the paucity of studies on performance monitoring (especially in call

centers), more research is needed on how different aspects of performance moni-

toring relate to well being. In particular, research is needed that focuses on a wide

range of performance monitoring characteristics, for example, its content, purpose,

and monitoring cognitions. It is also important to examine whether performance

monitoring affects particular aspects of well-being or has more global effects. For

example, Carayon’s finding that performance monitoring was unrelated to anxiety

suggests it might only affect particular aspects of well-being (Carayon, 1994). It

is not possible at present to make reliable assertions as to whether monitoring has

specific or global effects. This is because previous research has tended to use global

measures of stress (i.e., whether the individual feels stressed or not) or measures

of satisfaction (Aiello & Kolb, 1995; Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989). This implies

that, as in the studies by Smith et al. (1992) and Carayon (1994), the diversity of

emotional experience should be measured.

Thus, the first aim of this study is to examine the relationship between differ-

ent aspects of employee well-being and the content of performance monitoring,

the purpose of performance monitoring and monitoring cognitions. How might

the different aspects of performance monitoring affect well-being? With regard

to the content of performance monitoring, two rival hypotheses exist. The first

hypothesis asserts that well-being may be improved by those aspects of the con-

tent of performance monitoring which pertain directly to the development of per-

formance (e.g., the feedback process, the clarity of performance criteria). The

performance-related content of performance is thought to increase an employee’s

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

62

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

knowledge of his or her performance and to help improve the employee’s skills

and performance. Greater knowledge of one’s performance can reduce anxiety

about how one is viewed by the organization. The improvement in skills and per-

formance may improve a person’s ability to cope with work demands, and this

results in reduced anxiety and less emotional exhaustion (Jenkins & Maslach,

1994; Karasek & Theorell, 1990). The second hypothesis asserts that performance

monitoring is intrinsically threatening, because the information gained may affect

remuneration and promotion decisions or affect an employee’s relationship with

the employee’s colleagues or supervisor (or both). The fear of evaluation may

also heighten sensitivity to feedback and damage feelings of self-worth (Smith,

Carayon, & Miezio, 1986). Monitoring is also seen to intensify workload (as in-

creased surveillance means that the employee has less opportunity to reduce his

or her work rate) and increase cognitive demand as it is an additional factor to be

considered by the employee (Smith et al., 1992). The threat of monitoring and the

high level of demand are thought to impact negatively on employee well-being. As

current evidence seems to support the first explanation, the first hypothesis of this

study is:

Hypothesis 1: The performance-related content of performance monitoring will

be positively associated with well-being.

Performance monitoring can be used for a number of reasons and although

no research has been conducted on the purposes of monitoring (Stanton, 2000),

it is likely that when an employee perceives the purposes of monitoring to be

beneficial (e.g., developmental, ensuring correct standards of service) rather than

nonbeneficial (e.g., punitive), then performance monitoring will be positively as-

sociated with well-being. Indeed, beneficial purposes may reduce the likelihood

of monitoring being thought of as threatening and anxiety provoking. The second

hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2: When the purpose of monitoring is perceived as beneficial, it will

be positively associated with well-being.

A range of employee monitoring cognitions could be studied, for example,

fairness, trust, and attitudes. In this study we decided to focus on intensity as it had

not been studied before. When monitoring is perceived as intense (i.e., that there

is no escape and that it is pervasive), individuals will feel under greater pressure

and perceive work demands to be higher. As higher levels of work pressure and

demands have generally been shown to be associated with lower levels of well-

being (Karasek & Theorell, 1990), the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3: The intensity of monitoring will be negatively associated with well-

being.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

63

EMOTIONAL LABOR AND CALL MONITORING

In service organizations, employees are generally required to manage their

emotional expression toward customers (Hochschild, 1983). In particular, em-

ployees are expected to display the appropriate emotional expression, whether

it be a display of positive emotion (e.g., “smiling down the phone” in call cen-

ters, Belt, Richardson, & Webster, 1999) or negative emotion (e.g., anger in bill

collectors, Sutton, 1991). The emotional display of employees is seen to be an

intrinsic and important aspect of the service provided, and the effort involved in

managing one’s emotions in exchange for a wage has been labelled “emotional

labor” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7). For the organization, emotional labor has a number

of potential benefits, such as improved customer service, customer retention and

increased sales. For the employee, studies generally show that the effects of emo-

tional labor can be positive and negative (although a few studies show no effects,

e.g., Zerbe, 2000). For example, Zapf, Vogt, Seifert, Mertini, and Isic (1999) found

that the requirement to express positive emotions was associated with feelings of

both personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion. Similarly, Schaubroeck

and Jones (2000) found that the requirement to express positive emotions was

associated with symptoms of ill health, while Parkinson (1991) found that more

emotionally expressive hairdressers received bigger tips.

Although the relationships between emotional labor and well-being are com-

plex, one aspect of emotional labor, called emotional dissonance, has been con-

sistently associated with lower well-being (Hochschild, 1983; Zapf et al., 1999).

Emotional dissonance occurs when there is a discrepancy between what a person

is required to express by the organization and what they feel. In response to this,

the individual can either display his or her “true” emotions or try to ensure that the

emotions displayed are in line with organizational requirements. If they choose the

latter option, two modes of emotional regulation may be deployed, surface acting

or deep acting (Hochschild, 1983). Surface acting involves the display of required

emotions but there is no attempt to actually feel or experience those emotions. For

example, an employee may “paste” a smile on her face even though she is feeling

unhappy. Thus, inherent in surface acting is a continued discrepancy between dis-

played and felt emotions. In contrast, workers who perform “deep acting” endeavor

to feel the required emotions as a means of creating an appropriate display of emo-

tion (Brotheridge & Lee, 1998). To perform deep acting, an employee can adopt

various strategies, such as attention deployment (think about events that call up

emotions needed), and cognitive change (reappraise the situation so its emotional

impact is lessened, Grandey, 2000).

The effort involved in managing one’s emotions is thought to decrease well-

being. Indeed, high levels of emotional management have been linked to emotional

exhaustion, a feeling of being used up, worn out and irritable in one’s personal

interactions (Brotheridge & Lee, 1998; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Maslach &

Jackson, 1981). Furthermore, being in a state of dissonance can in itself be anxiety

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

64

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

provoking (Carver, Lawrence, & Scheier, 1995), while surface acting may stifle

personal expression and this may be experienced as unpleasant and dissatisfying

(Rutter & Fielding, 1988). Continued and sustained feelings of dissonance and sur-

face acting (particularly faking and feeling false) may also result in depression, as

the feeling of “being a fake” and being false may damage one’s self worth (Bandura,

1997). Alternatively, deep acting may reduce dissonance and, therefore, anxiety.

Performance monitoring is one means through which organizational require-

ments are enforced. Performance monitoring may reduce the range of emotions

displayed by employees (by specifying what emotions can be displayed) and

increase the level of dissonance. This increase in dissonance and its regulation

using surface and deep acting may then affect well-being. This chain of reasoning

suggests that emotional labor will mediate the relationship between performance

monitoring and well-being. The following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

Hypothesis 4: Emotional labor will mediate the relationship between performance

monitoring and well-being.

WORK CONTEXT, PERFORMANCE MONITORING,

AND WELL-BEING

In separate reviews of the performance monitoring literature, Smith and

Amick (1989) and Carayon (1993) suggest that job control, job demand, and

social support are important factors to consider when examining the relationship

between work context, performance monitoring and well-being. Carayon (1993)

argues that, while performance monitoring will have direct effects on well-being,

its effects on well-being will also be indirect and mediated by the work context

(e.g., job design and supervisory style) (Rousseau, 1978). According to this idea,

performance monitoring indirectly affects well-being by simplifying work, reduc-

ing job control (Schleifer, 1990; Smith & Amick, 1989; Smith et al., 1992; Stanton

& Barnes Farrell, 1996) and increasing work demands (Smith et al., 1992). Smith,

Carayon, and Miezio (1986) also found that the introduction of performance mon-

itoring produces a stricter and more coercive style of supervision. These changes

in work context are then seen to impact negatively on employee well-being. The

following hypothesis is therefore proposed.

Hypothesis 5: Job control, job demands, and supervisory support will mediate the

relationship between performance monitoring and well-being.

Carayon (1993) also argues that the work context will moderate the relation-

ship between performance monitoring and well-being. In particular, it is expected

that job control, job demands, and supervisory support will affect the impact of the

intensity of monitoring. When job control and supervisory support are high they

will act as buffers, reducing the negative impact of intensity on well-being. Job

demand will act as a “multiplier.” When job demand is high, it will increase

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

65

the negative impact of intensity on well-being. With regard to the content and

purpose of monitoring, the supervisor could affect the content and purpose of per-

formance monitoring by, for example, deciding to use it for punitive purposes or

to increase the level of feedback. As such, when supervisory support is high it will

increase the impact that the content and purpose of monitoring have on well-being.

On the basis of the above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6: Job control, job demands, and supervisory support will moderate

the relationship between the intensity of monitoring and well-being.

Hypothesis 7: Supervisory support will moderate the relationship between the

content and purpose of call monitoring and well-being.

Carayon (1994) also examined the effects of performance monitoring characte-

ristics on well-being relative to other work context variables such as workload

demand, variation in workload, and job control. He found that workload demand

and job control tended to have much stronger relationships to well-being than

performance monitoring characteristics. However, this research was not conducted

in a call center environment where performance monitoring is more pervasive. In

such a context, performance monitoring may have a much stronger relationship

with well-being relative to other work context variables. The following research

question was therefore set.

Research Question 1: What are the relative effects of performance monitor-

ing characteristics and work context variables on well-being in a call center

environment?

METHOD

Sample and Procedure

The present research was conducted in two call centers, “Mortgage-call” and

“Loan-call,” that were part of a U.K. bank. The data for this study was collected as

part of a larger longitudinal investigation into employee attitudes and well-being in

call centers. The research was conducted mainly by a questionnaire administered

on site. Prior to the survey administration, interviews with four Call Center Agents

(CSAs) and two supervisors concerning call monitoring were conducted and the

information obtained was used in the questionnaire design. It was stressed that

participation in the research was entirely voluntary and confidentiality was guar-

anteed. The survey took place during normal working hours and questionnaires

were returned to the researcher on site. A total of 347 questionnaires were returned

by CSAs. This represented a response rate of 79%. Of the total sample, 70.6% were

female and 29.4% were male. The mean age was 32.3 years (range 19–57). The av-

erage job tenure was 28 months, and average time with the company was 45 months.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

66

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

Description of Cases and Performance Monitoring Procedures

At both sites, CSAs spent about 80–90% of their time answering incom-

ing calls that were mainly from external customers. The remaining time was

spent in team meetings and off-line administration. At Mortgage-call, a CSA’s

job entailed taking incoming calls from customers, bank branches, and solicitors

concerning mortgage enquiries. At “Loan-call,” CSAs took incoming calls re-

garding loan applications and queries. CSAs were also expected to sell loan

insurance.

CSAs were monitored similarly at both sites, although there were small dif-

ferences. At both sites, continuous electronic performance monitoring (via a man-

agement information system) was used to collect quantitative performance data

on logging-in and out times, average call time, average time unavailable, and av-

erage call rate. This information was circulated to CSAs on a daily basis. Episodic

traditional monitoring, namely listening to calls, was conducted in three ways.

Firstly, “side-by-side,” whereby the supervisor sits next to the CSA while they

take a call. Secondly, “remote” monitoring, where the supervisor sits separately

from the CSA, often out of sight, and listens to the CSA’s calls without the agent’s

knowledge. Thirdly, calls may be randomly taped and then listened to by the su-

pervisor on a later occasion. The dominant method used was remote monitoring.

The supervisor graded the content of the call according to a specific guideline. At

Mortgage-call a guideline of eight areas, such as “greeting,” “identify and analyse

customer needs,” and “professionalism,” was used. To obtain an “exceed” rating

with regard to professionalism, CSAs had to, for example, “demonstrate interest in

helping the customer,” “have a pleasant, friendly, approachable, and professional

tone,” offer “sincere apologies” and be “patient with difficult and unresponsive

customers.” At Loan-call, CSAs had to follow a call-guide that indicated what

should ideally be said to the customer. The call-guide was split into 12 sections

(e.g., introduction, gathering information, questioning) and included recommen-

dations about emotional display (e.g., shows empathy). CSAs received feedback

relating to calls during “coaching” sessions. Employees were meant to have their

calls listened to from three to six times a month, although in practice it was some

times less than this. Monitoring information made up 65% of the CSA’s Perfor-

mance Management plans. Performance management reviews took place once a

quarter and determined promotion and pay levels.

Measures

Performance Monitoring

The content, purpose, and intensity of performance monitoring were mea-

sured. The content of performance monitoring was measured using five items and

the items pertained directly to those aspects of the content of monitoring that are

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

67

performance-related. For this reason the scale is referred to as the “performance-

related content of monitoring.” The five items were partly based on items used by

Chalykoff and Kochan (1989) and included four questions on traditional perfor-

mance monitoring. This covered the frequency of call monitoring, clarity of perfor-

mance criteria, the immediacy of feedback and whether the feedback was positive.

Another question covering the frequency of feedback received from continuous

electronic monitoring was added. Both traditional and electronic forms of moni-

toring were covered and this is in keeping with recommendations by Lund (1992).

A 5-point scale was used (Not at all to A great deal;

α = 0.75). The purpose of

monitoring was a newly constructed 3-item scale (sample items, “The purpose

of call monitoring is to ensure I provide the correct level of customer service,”

“The purpose of call monitoring is to punish me rather than develop me” [reverse

scored]). For reasons of clarity we will refer to this scale as “beneficial-purpose

of monitoring.” The perceived intensity of performance monitoring was a 5-item

scale covering the intensity of both the electronic and traditional forms of moni-

toring (sample items, “Call monitoring, e.g., remote, side by side, at work is too

intense” and “Monitoring of statistics increases the pressure I feel under.” For pur-

pose and intensity of call monitoring, a 5-point scale was used (Strongly disagree

to Strongly agree) and the reliabilities were

α = 0.74 and α = 0.88 respectively.

Emotional Labor

With regard to emotional labor, emotional dissonance, surface acting, and

deep acting were measured. Emotional dissonance was measured using a newly

constructed 3-item scale (sample items; “I often feel there is a discrepancy between

what I feel and the emotions I am required to express to customers” and “There’s

no difference between the emotions I’m expected to express to customers and how

I feel” [reverse scored]). A 5-point scale was used (Strongly disagree to Strongly

agree). Surface acting and deep acting were measured using Brotheridge and Lee’s

3-item scales (Brotheridge & Lee, 1998). A sample item for surface acting was “In

order to do your job effectively, how often do you fake a good mood?” A sample

item for deep acting was “how often do you try to actually experience the emotions

you display to customers?” Both items used a 5-point scale (Not at all to A great

deal). The reliabilities for emotional dissonance, surface acting, and deep acting

were, respectively,

α = 0.76, α = 0.85, and α = 0.90.

Job Context

Adapted versions of the Jackson, Wall, Martin, and Davids’ scales were used

to measure job control and job demand (Jackson, Wall, Martin, & David, 1993).

Items were reworded where necessary to reflect a call center environment. Speci-

fically, job control was measured by a 5-item scale (sample item, “Can you vary

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

68

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

how you talk with customers?”;

α = 0.80). Job demand was measured by the

problem-solving demand scale and had five items (sample item, “Do you have to

solve problems which have no obvious correct answer?”;

α = 0.77). Both scales

used a 5-point scale (Not at all to A great deal). Supervisor support was based

on a measure used by Axtell et al. (2000) and consisted of six items relating to

the quality of supervisory style (e.g., “Does your supervisor discuss and solve

problems with you?”;

α = 0.79).

Well-Being

Four measures of job-related well-being were used, the first being “Intensity

of Emotional Exhaustion” (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Space limitations meant

that only the four items that loaded most highly on “Emotional Exhaustion” in

Maslach and Jackson’s study were used (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). A sample

item was “Feel emotionally drained from your work.” A 7-point scale was used

(Very Mildly to Very Strongly;

α = .93). Anxiety and Depression were measured

using six item scales developed by Warr (1990). Both scales asked about feelings

experienced at work over the last month. Feelings on the anxiety scale included

tense, worried, calm, and relaxed. Feelings on the depression scale included mis-

erable, depressed, and optimistic. A 5-point scale was used (Never to All of the

time) and the reliabilities were

α = 0.83 and α = 0.84 respectively. Job satisfac-

tion was measured using Warr, Cook, and Wall’s scale containing 15 items for

example, physical work conditions, job security, recognition for good work, and

amount of responsibility (Warr, Cook, & Wall, 1979). A sample item was “How

satisfied are you with your colleagues.” A 7-point scale (Extremely dissatisfied to

Extremely satisfied) was used (

α = 0.87). It is recognized that job satisfaction, as

an attitude, has both affective and cognitive components (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993;

Fisher, 2000; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). It was included in this study as we

were interested in its affective component and in order to facilitate comparison

with previous research.

RESULTS

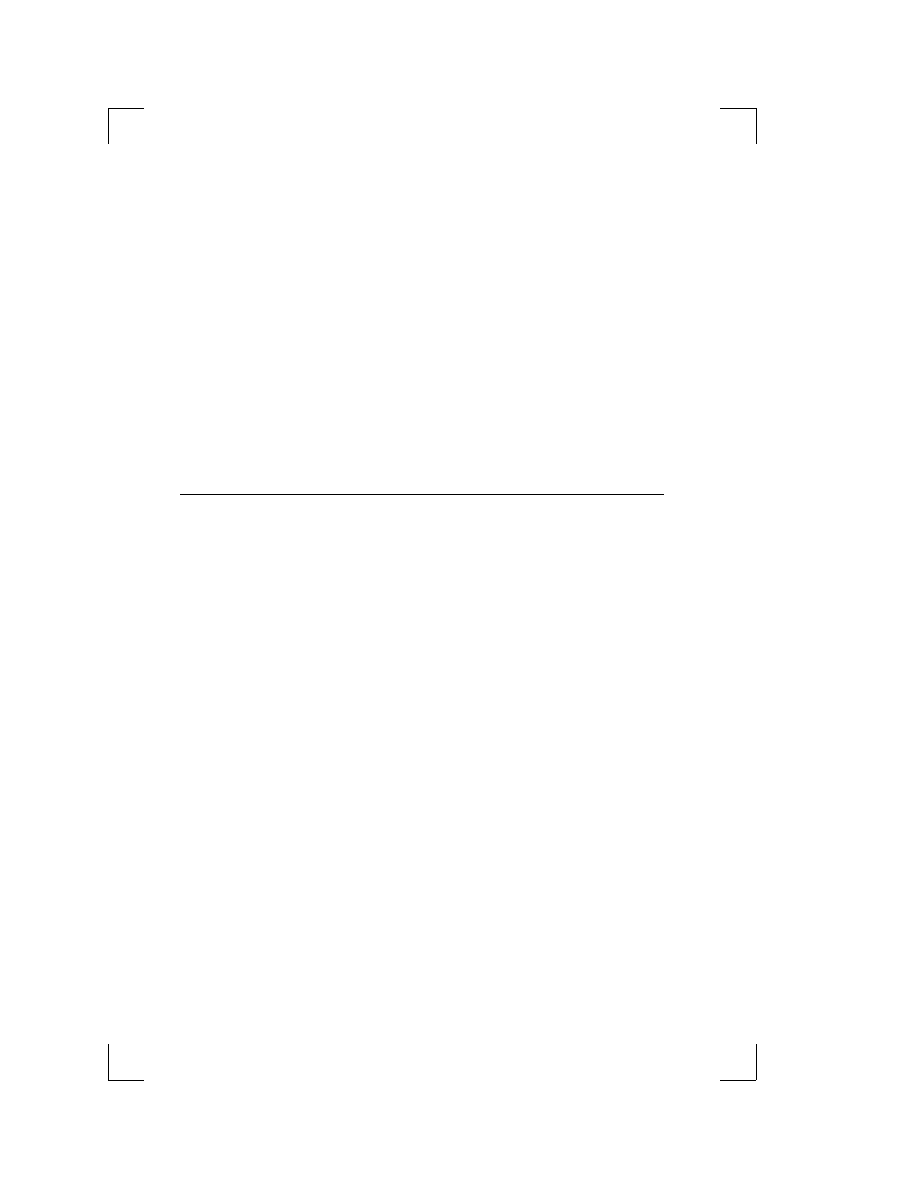

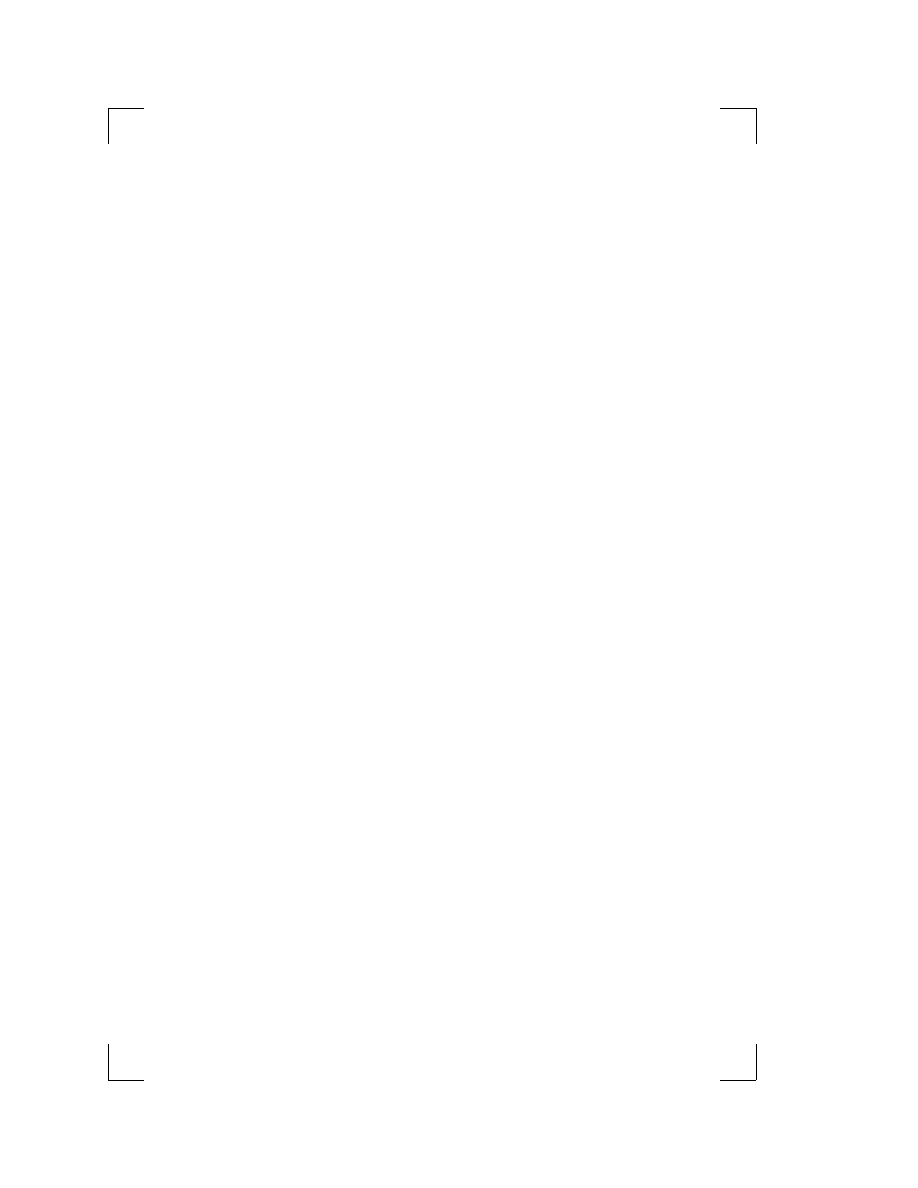

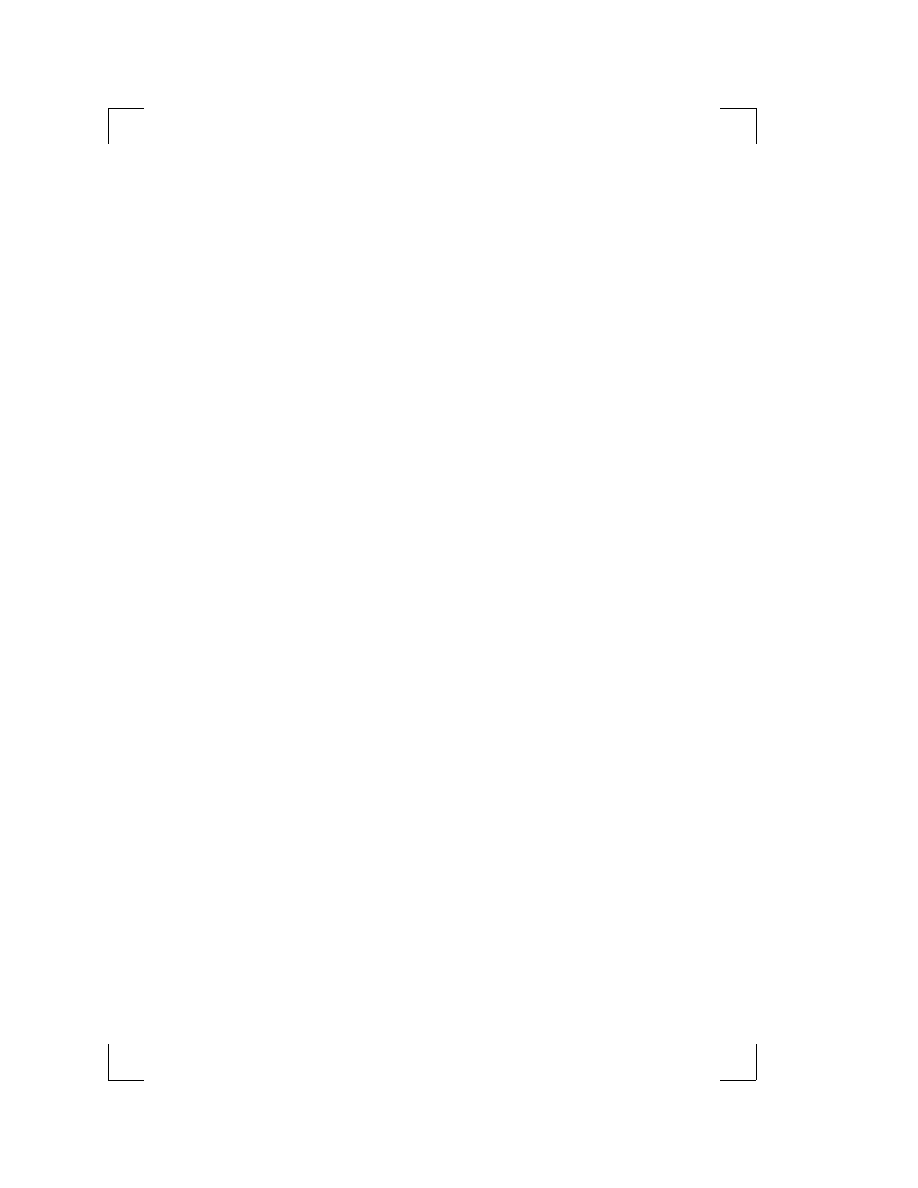

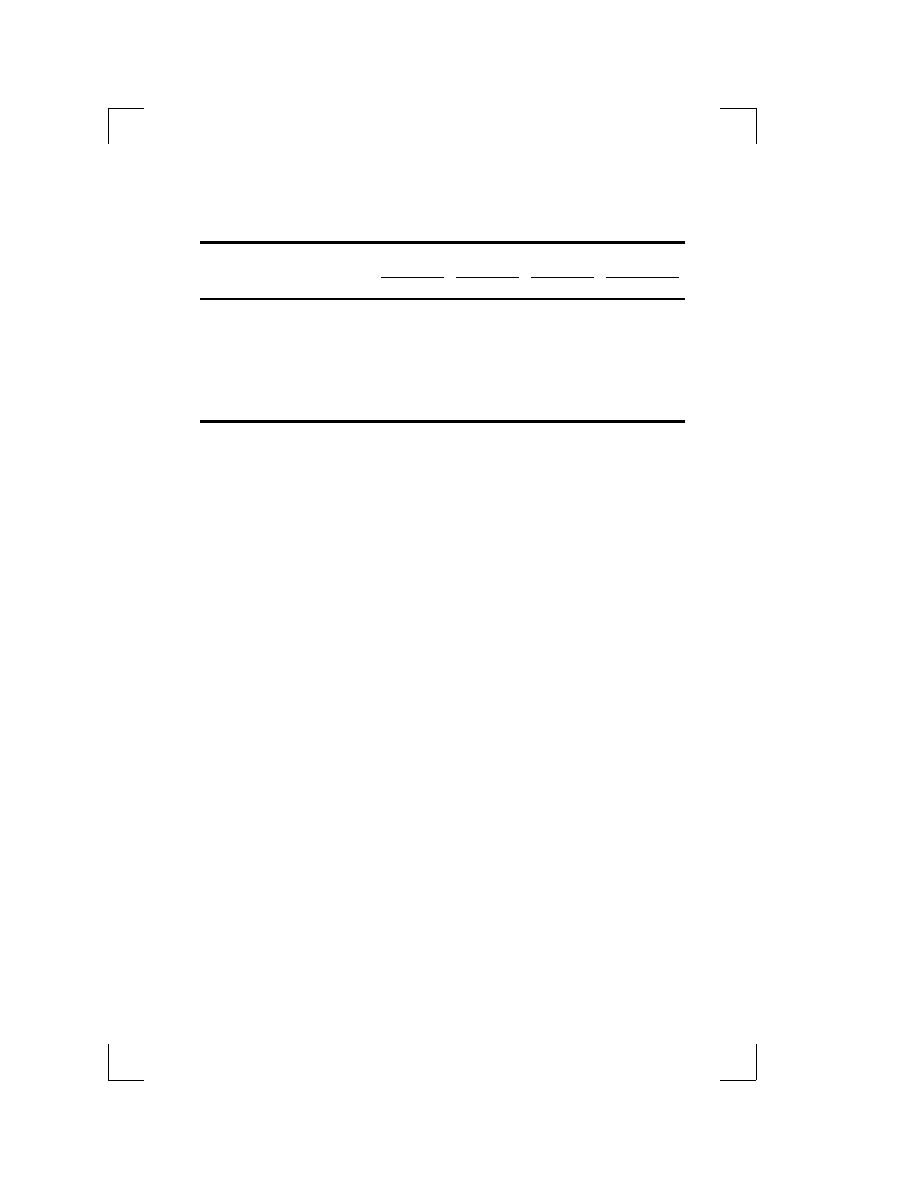

Zero-order correlations and means of the main study variables are shown in

Table I. Focusing on correlations between performance monitoring variables, it is

evident that the performance-related content of monitoring was unrelated to inten-

sity of monitoring. The performance-related content of monitoring was, however,

positively related to the beneficial-purpose of monitoring (r

= .30, p < .01), while

the beneficial-purpose of monitoring was negatively related to intensity (r

= −.42,

p

< .01). The sizes of the correlations between the monitoring variables suggests

that they are separate constructs. Of the correlations between the emotional labor

variables, deep acting was related to surface acting (r

= .37, p < .01) but not

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

T

able

I.

Means,

Standard

De

viations,

and

Correlations

Between

the

Main

Study

V

ariables

(N

=

347)

MS

D

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

1.

Age

(years)

32.22

8.69

—

2.

Gender

0.29

0.46

−

.28

∗∗∗

—

(male

=

1)

3.

Job

tenure

27.38

25.83

.40

∗∗∗

−

.22

∗∗∗

—

(months)

4.

Content

of

3.37

0.84

.03

−

.04

.08

—

performance

monitoring

5.

Purpose

of

3.94

0.66

−

.04

−

.06

−

.02

.30

∗∗∗

—

performance

monitoring

6.

Intensity

of

3.03

0.95

.13

∗

−

.09

.02

−

.07

−

.42

∗∗

—

performance

monitoring

7.

Emotional

3.41

0.76

−

.16

∗∗

.06

.08

−

.08

−

.16

∗∗

.25

∗∗∗

—

dissonance

8.

Surf

ace

2.67

1.04

−

.18

∗∗∗

.00

−

.02

−

.07

−

.13

∗

.19

∗∗∗

.39

∗∗∗

—

acting

9.

Deep

acting

2.30

1.00

−

.02

−

.02

.02

.06

.04

.10

.07

.37

∗∗∗

—

10.

Emotional

3.19

1.74

.01

.02

−

.12*

−

.07

−

.18

∗∗∗

.35

∗∗∗

.27

∗∗∗

.36

∗∗∗

.14

∗∗

—

exhaustion

11.

Job

4.41

0.81

.14

∗

−

.15

∗∗

.09

.38

∗∗∗

.41

∗∗∗

−

.29

∗∗∗

−

.33

∗∗∗

−

.28

.06

−

.39

—

satisf

action

12.

Job-related

2.78

0.73

−

.02

−

.09

−

.03

−

.09

−

.11

∗

.35

∗∗∗

.27

∗∗∗

.28

∗∗∗

.11

∗

.67

−

.37

∗∗∗

—

anxiety

13.

Job-related

2.63

0.75

−

.08

.04

−

.08

−

.17

∗∗

−

.25

∗∗∗

.31

∗∗∗

.32

∗∗∗

.29

∗∗∗

−

.05

.58

−

.59

∗∗∗

.67

∗∗∗

—

depression

14.

Job

control

2.56

0.88

−

.09

.22

.05

−

.05

.15

∗∗

−

.32

∗∗∗

−

.15

∗∗

−

.20

∗∗∗

−

.04

−

.17

∗∗∗

−

.17

∗∗∗

−

.27

∗∗∗

−

.26

∗∗

—

15.

Problem

3.51

0.75

.00

−

.05

.08

.09

−

.05

.18

∗∗∗

.06

.18

∗∗∗

.05

.22

∗∗∗

−

.15

∗∗

.13

∗∗

.04

.03

—

solving

demand

16.

Supervisor

3.67

0.76

.05

−

.01

.01

.53

∗∗∗

.43

∗∗∗

−

.32

∗∗∗

−

.23

∗∗∗

−

.19

∗∗

.02

−

.26

∗∗∗

.55

∗∗∗

−

.24

∗∗∗

−

.33

∗∗∗

.17

∗∗

.11

support

∗

p

<.

05

.

∗∗

p

<.

01.

∗∗∗

p

<.

001.

69

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

70

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

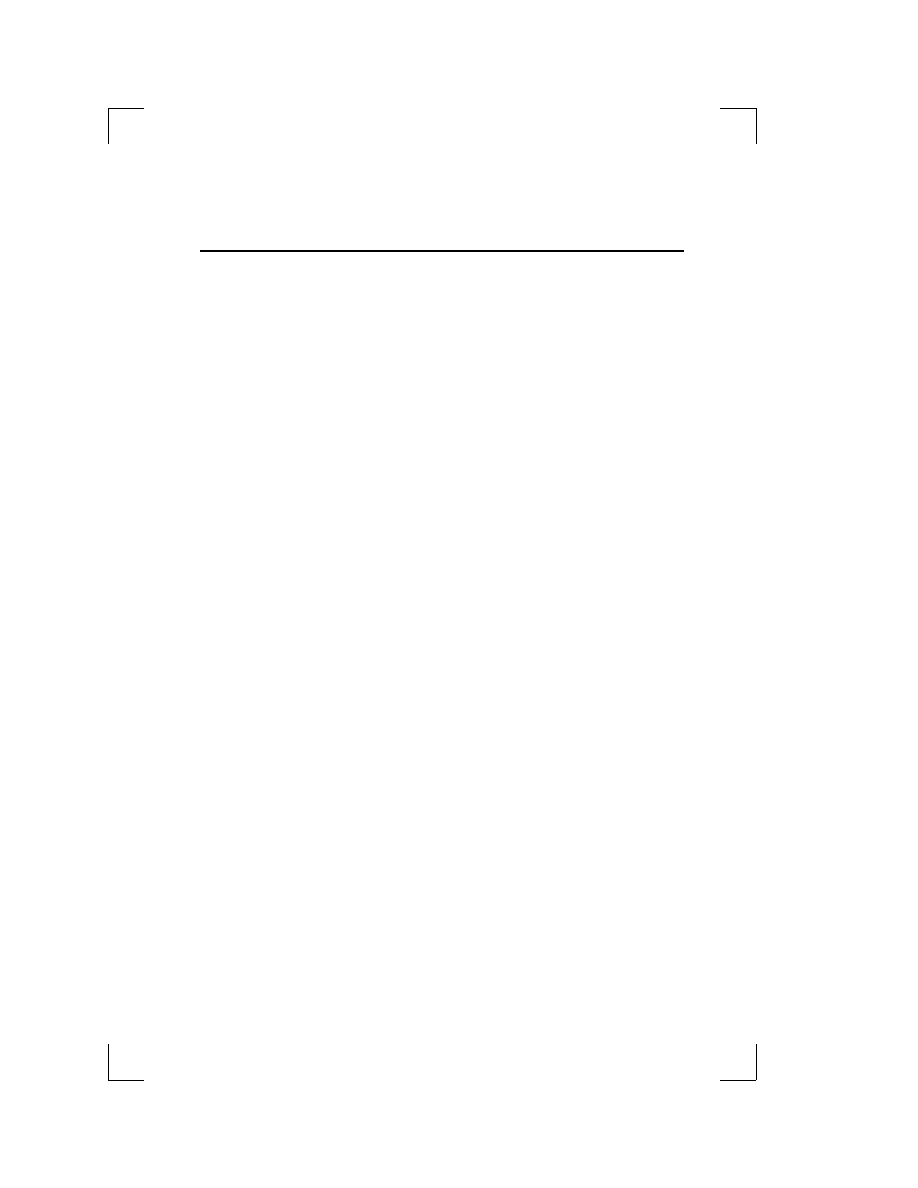

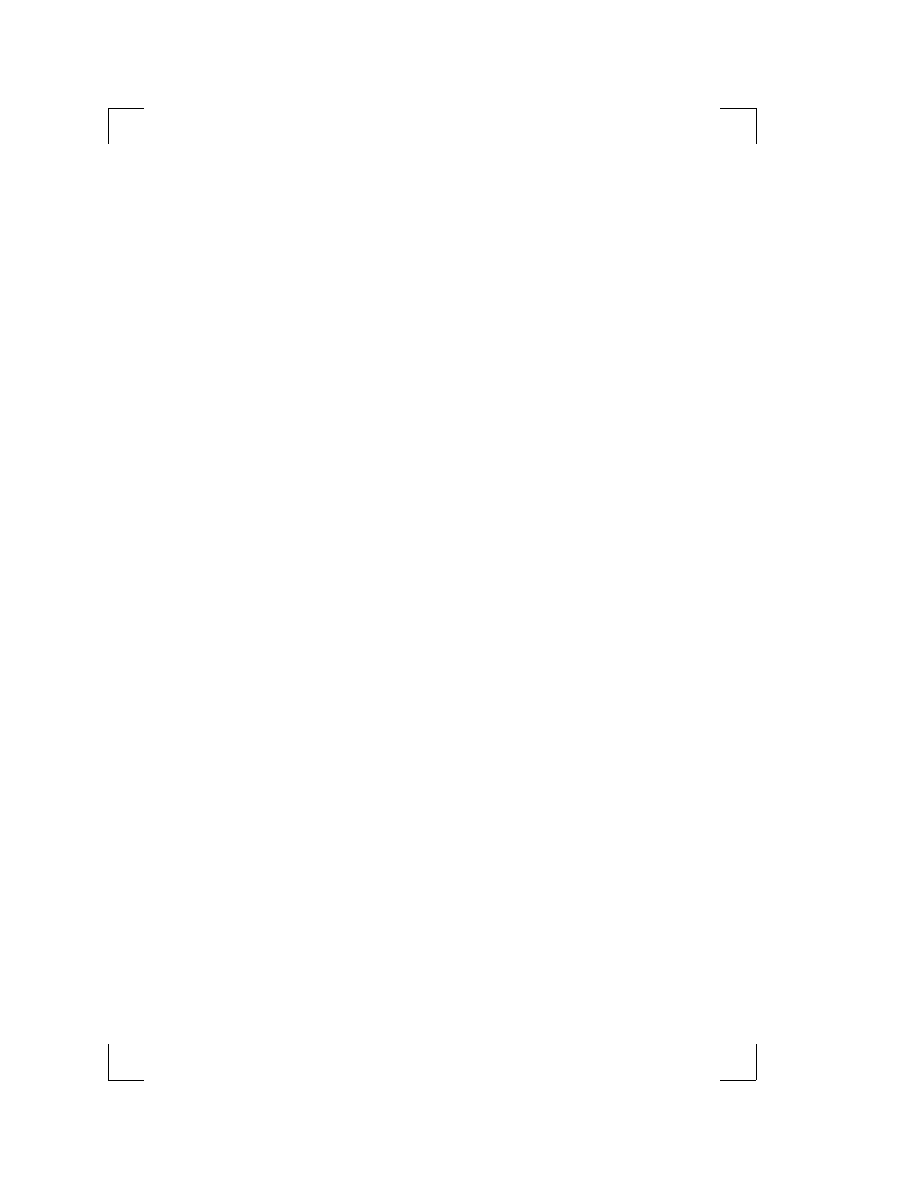

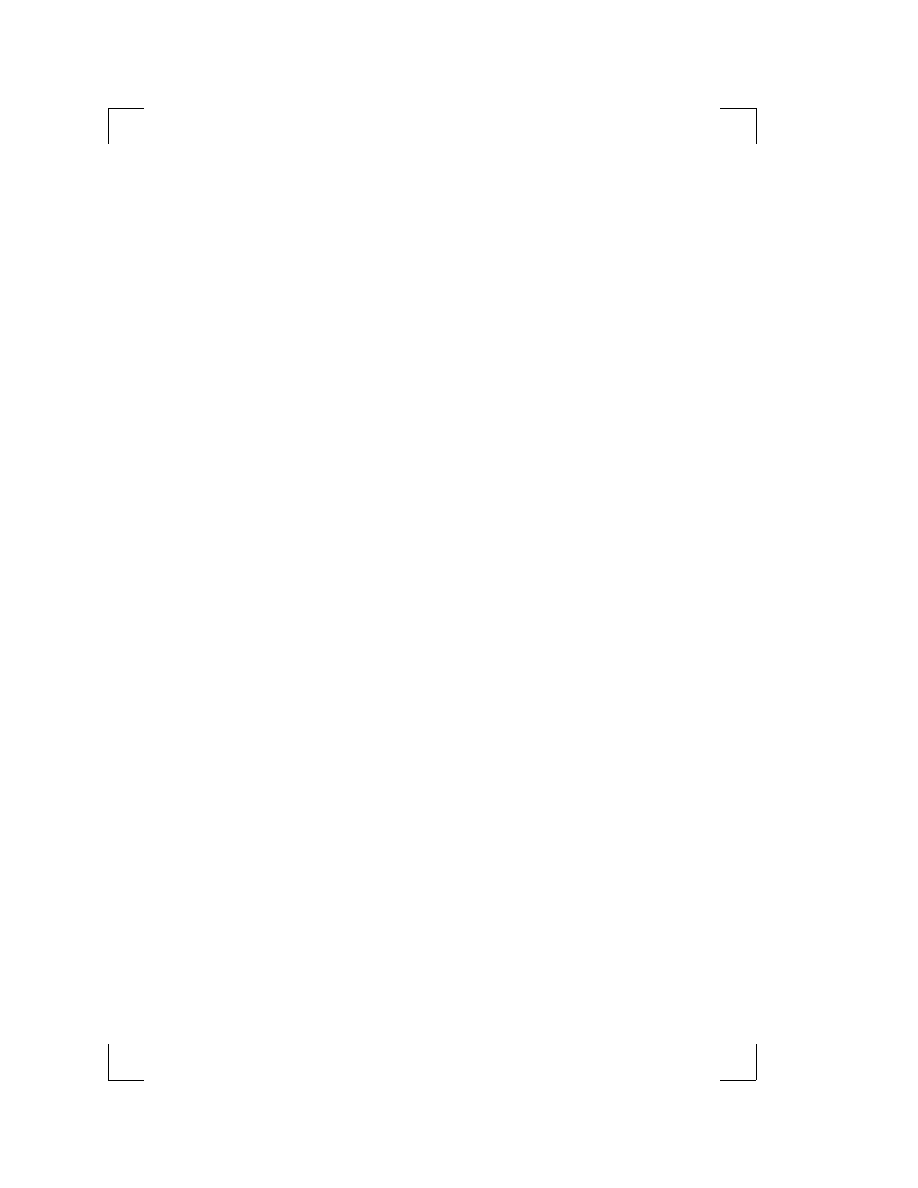

Table II. Results of Hierarchical Regressions: The Effect of Performance Monitoring on Well-

Being (N

= 347)

Emotional

exhaustion

Anxiety

Depression

Job satisfaction

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

All regressions

Step 1: Control

.00

—

.01

—

.03

—

.04

—

Regression 1

Step 2: Content of monitoring

.00

−.06 .01

−.10 .02

∗∗

−.15 .13

∗∗∗

.37

Regression 2

Step 2: Purpose of monitoring

.03

∗∗

−.17 .01

−.10 .06

∗∗∗

−.24 .18

∗∗∗

.42

Regression 3

Step 2: Intensity of monitoring

.13

∗∗∗

.38 .12

∗∗∗

.36

.12

∗∗∗

.36 .13

∗∗∗

−.37

∗∗

p

< .01.

∗∗∗

p

< .001.

emotional dissonance. Emotional dissonance and surface acting were positively

correlated (r

= .39, p < .01). The sizes of the correlations between the emotional

labor variables suggests that they are separate constructs.

Relationship of Performance Monitoring to Well-Being

To test the first three hypotheses, a series of hierarchical regressions were

conducted for each of the well-being measures. At step one, control variables

were entered, namely, site (dummy coded), age, gender, and job tenure. The

same control variables were used in all subsequent analyses. At step two, the

appropriate performance monitoring variable was entered. The results are shown

in Table II. From Table II, it can be seen that the performance-related content

of performance monitoring was unrelated to emotional exhaustion and anxiety,

negatively associated with depression (

β = −.15, p < .01) and positively associ-

ated with job satisfaction (

β = .37, p < .01). Hypothesis 1, that the performance-

related content of call monitoring will be positively associated with well-being,

was partially confirmed. Hypothesis 2, that when the purpose of monitoring is ben-

eficial it will be positively associated with well-being, and Hypothesis 3, that the

intensity of monitoring will be negatively associated with well-being, were gener-

ally confirmed. Specifically, the beneficial-purpose of monitoring was negatively

associated with emotional exhaustion and depression (

β = −.17, p < .01, and

β = −.24, p < .01 respectively), but positively associated with job satisfaction

(

β = .42, p < .01). The intensity of monitoring was associated with all the mea-

sures of well-being. Intensity was positively associated with emotional exhaustion,

anxiety, and depression (respectively,

β = .38, β = .36, β = .36, all p < .01) and

negatively associated with job satisfaction (

β = −.37, p < .01). It is also worth

noting that the level of association between well-being and intensity was consis-

tently higher than for the performance-related content or beneficial-purpose of

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

71

monitoring variables. The intensity of monitoring accounted for 12–13% of the

remaining variance, after the control variables had been entered, for each of the

well-being measures.

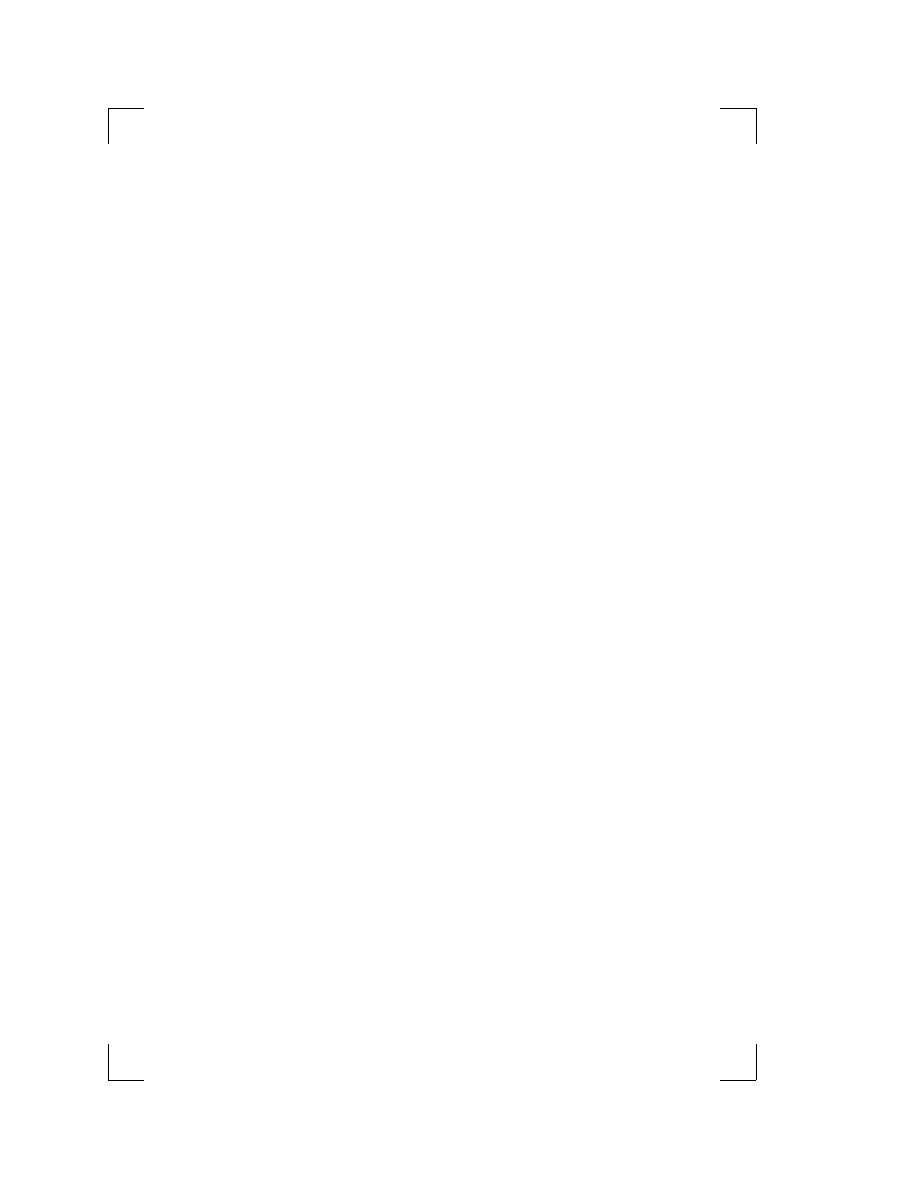

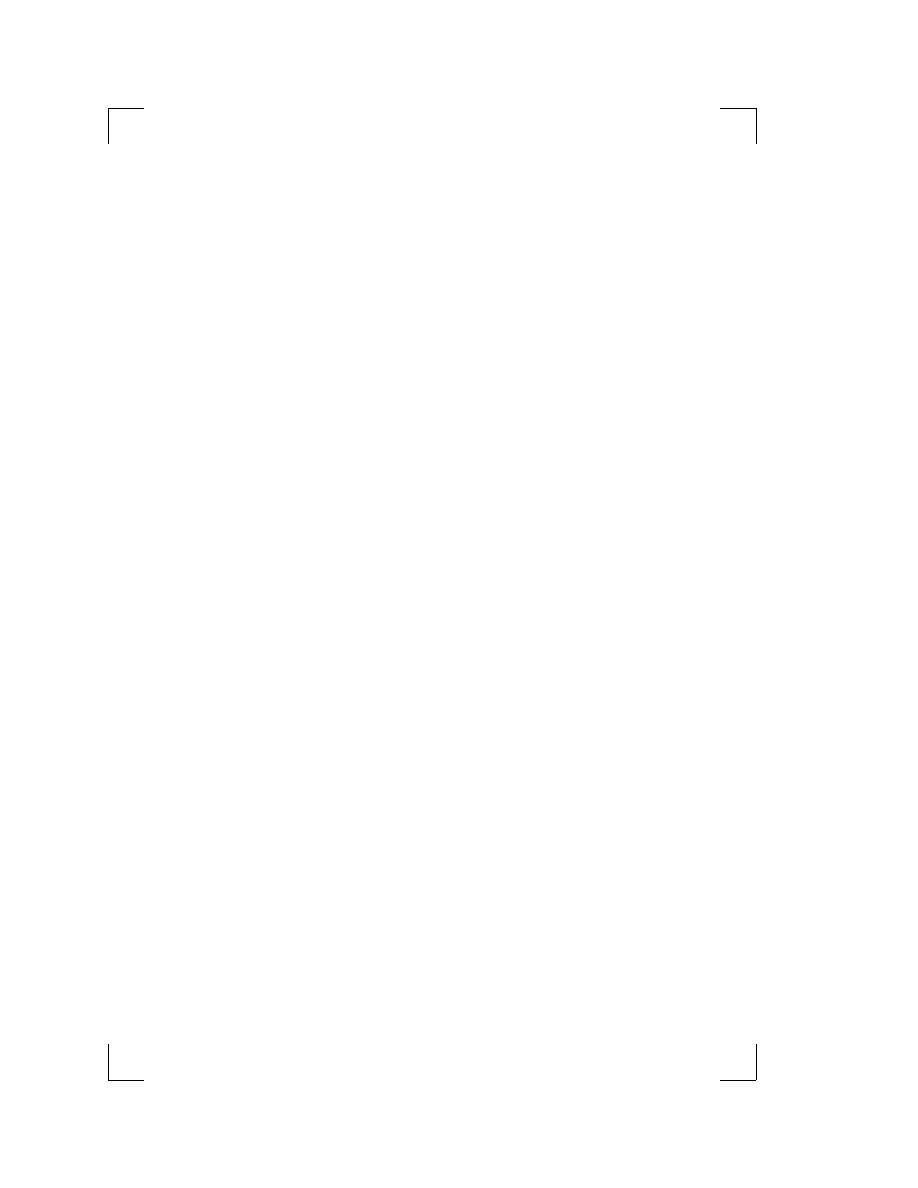

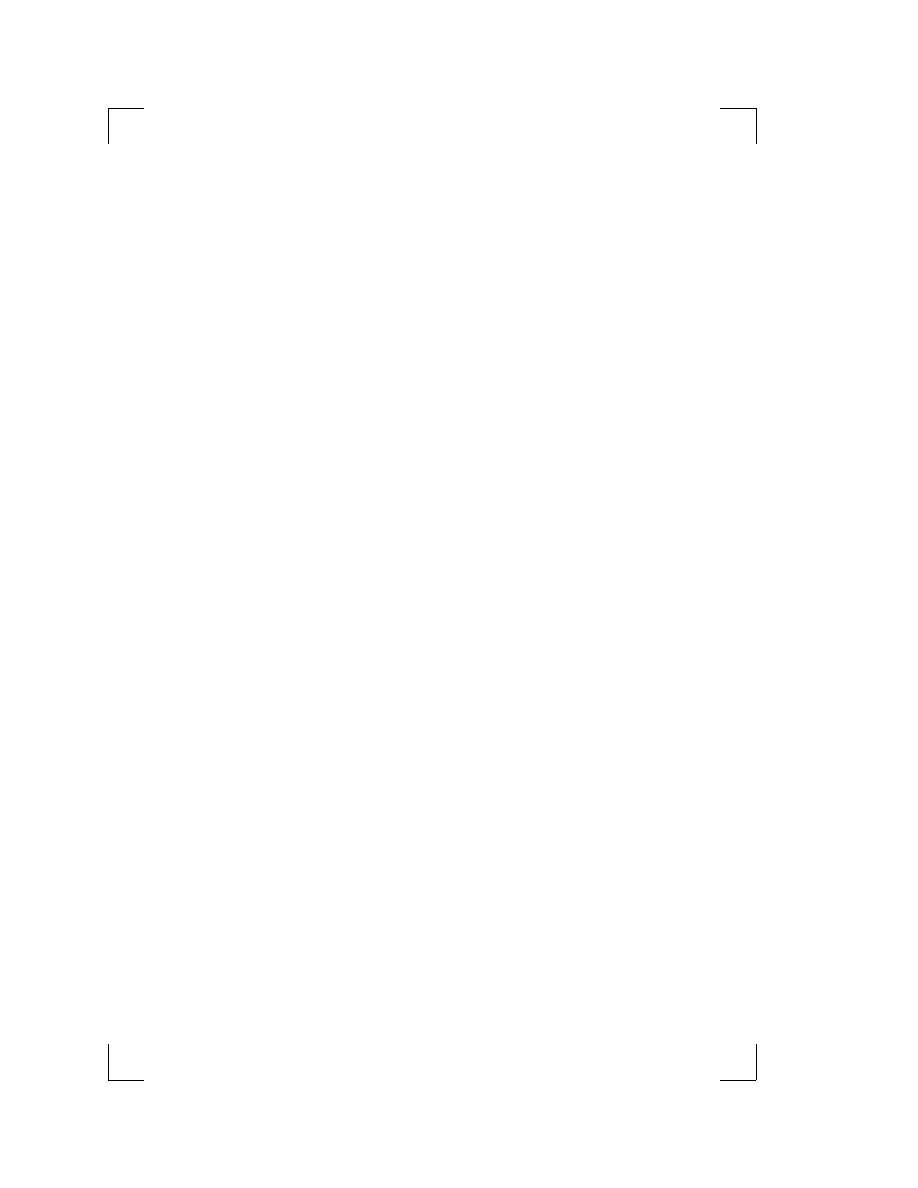

Relationship of Call Monitoring to Emotional Labor and Well-Being

Hypothesis 4 stated that emotional labor (manifest as dissonance followed by

surface or deep acting) would mediate the relationship between performance mon-

itoring and well-being. Following Baron and Kenny (1986), the test for mediation

was carried out in two stages. The first stage examined whether the following

conditions exist: the independent variable must affect the mediator, the indepen-

dent variable must affect the dependent variable, and the mediator must affect

the dependent variable. These initial conditions must be met if a mediation can

be said to exit. These conditions were not met with regard to deep acting and

most of the other variables, and with regard to the performance-related content of

monitoring and both emotional dissonance and surface acting. Deep acting and

the performance-related content of monitoring were not included in further medi-

ation analyses. The second stage involved the test for mediation. Thus, for each of

the well-being measures, control variables were entered at step one, followed by

the appropriate monitoring measure at step two. At step three, emotional disso-

nance was entered and at step four, surface acting. A mediated effect is shown when

the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is nonsignificant

when the effects of the mediator(s) are partialled out. We found no mediation

effects, as the performance monitoring variables were still significantly related

to the dependent variable, indicating that they had direct effects on well-being

unmediated by emotional labor.

However, we were still interested to explore the separate relationships be-

tween performance monitoring and emotional labor (manifest as dissonance fol-

lowed by surface or deep acting), and emotional labor and well-being. Two further

sets of hierarchical regressions were therefore conducted. The first set of regres-

sions examined whether dissonance mediated the relationship between perfor-

mance monitoring and surface acting. To test this, surface acting was the dependent

variable and control variables were entered at step one. At step two the appropri-

ate monitoring variable was entered (purpose or intensity), followed by emotional

dissonance at step three. The results in Table III show that when emotional disso-

nance was entered, the relationship between performance monitoring and surface

acting became nonsignificant. Emotional dissonance thus mediates the relation-

ship between the beneficial-purpose and intensity of monitoring and surface acting.

The second additional set of regressions found that surface acting did not mediate

the relationship between dissonance and well-being, and further regression anal-

yses confirmed that emotional dissonance and surface acting had direct effects on

well-being.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

72

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

Table III.

Results of Hierarchical Regressions: Emotional Dissonance

Mediating Between Performance Monitoring and Surface Acting (N

= 347)

β at each step

1

2

3

Regression 1

Step 1: Controls

—

—

—

Step 2: Purpose of monitoring

−.14

∗∗

−.08

Step 3: Emotional dissonance

.36

∗∗∗

R

2

.08

∗∗

.10

∗∗

.22

∗∗

1R

2

—

.02

.12

∗∗

Regression 2

Step 1: Controls

—

—

—

Step 2: Intensity of monitoring

.19

.09

Step 3: Emotional dissonance

.35

∗∗∗

R

2

.08

.11

∗∗

.22

∗∗∗

1R

2

—

.04

.11

Note. Regression 1: Surface acting as dependent and purpose of monitoring as

independent variable. Regression 2: Surface acting as dependent and intensity

of monitoring as independent variable.

∗∗

p

< .01.

∗∗∗

p

< .001.

Relationship of Work Context, Performance Monitoring,

and Well-Being

Hypothesis 5 stated that job control, job demands, and supervisory support

will mediate the relationship between performance monitoring and well-being.

To test this a series of hierarchical regressions were conducted with each of the

well-being meaures as the dependent variable. At step one, control variables were

entered, at step two, the appropriate performance monitoring variable was entered,

and at step three, the appropriate work context variable (i.e., job control, problem

solving demand, supervisor support) was entered. Hypothesis 5 was not confirmed

as no mediation effects were found. Further analysis also revealed that perfor-

mance monitoring did not mediate the relationship between work context and

well-being.

Hypotheses 6 and 7 were concerned with the moderating effects of the work

context on the relationship between performance monitoring and well-being. To

test these hypotheses, a series of hierarchical moderated regressions were con-

ducted with each well-being measure as the dependent variable. All variables were

standardized prior to analysis. At step one, control variables were entered, followed

by the appropriate performance monitoring variable at step two and the appropri-

ate work context variable at step three. Finally, at step four, the appropriate cross-

product term was entered (i.e., performance monitoring variable

× work context

variable). A consistent and significant pattern of interactions was found, but only

with regard to the intensity of monitoring and two work context measures, namely,

job control and supervisor support. Only these results are shown in Table IV.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

73

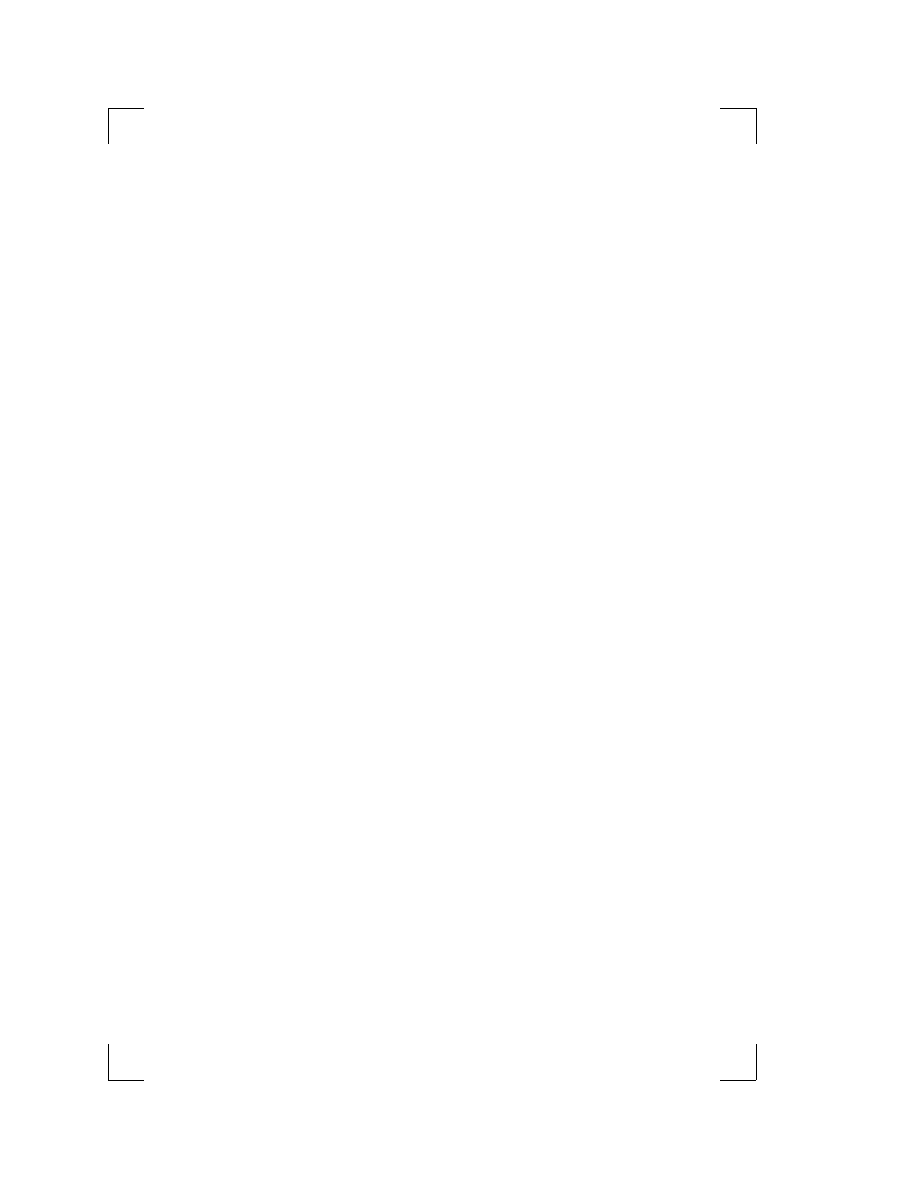

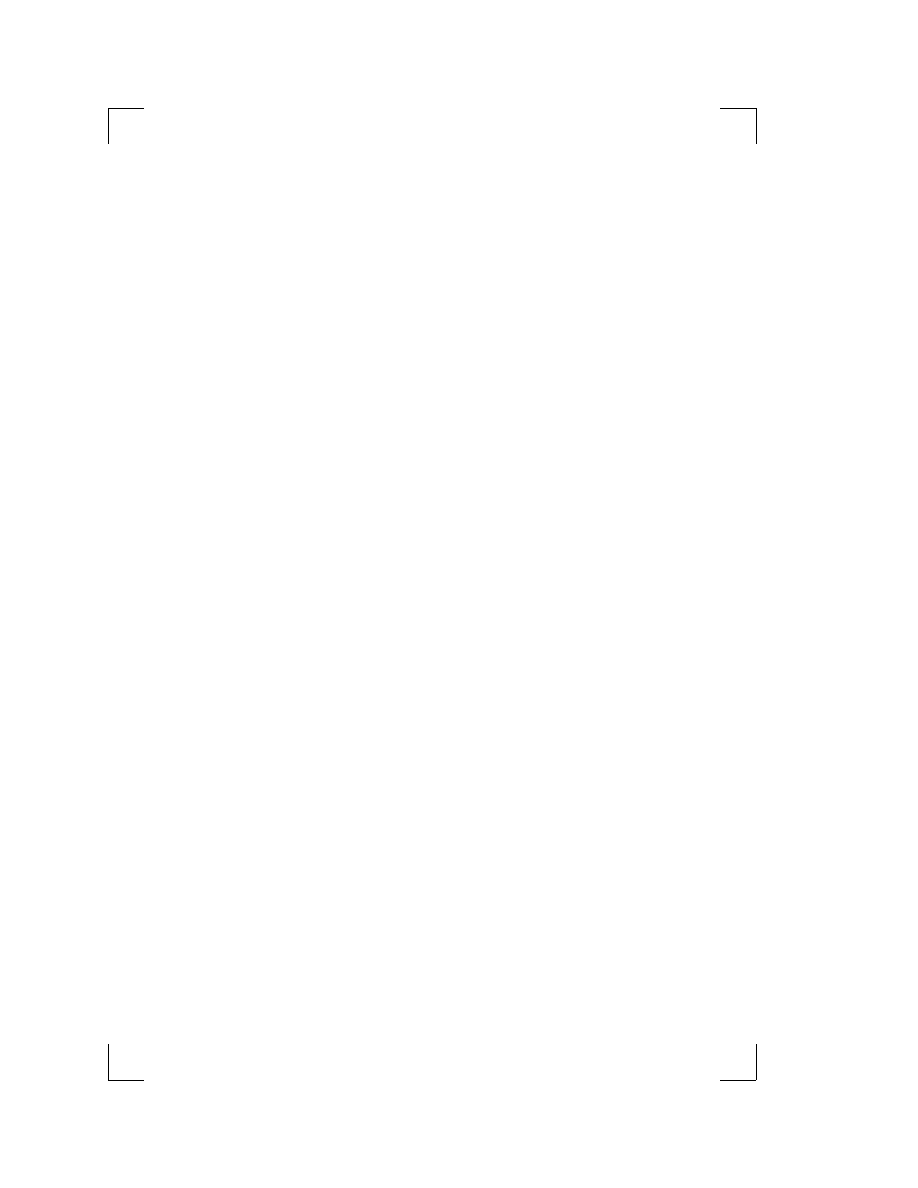

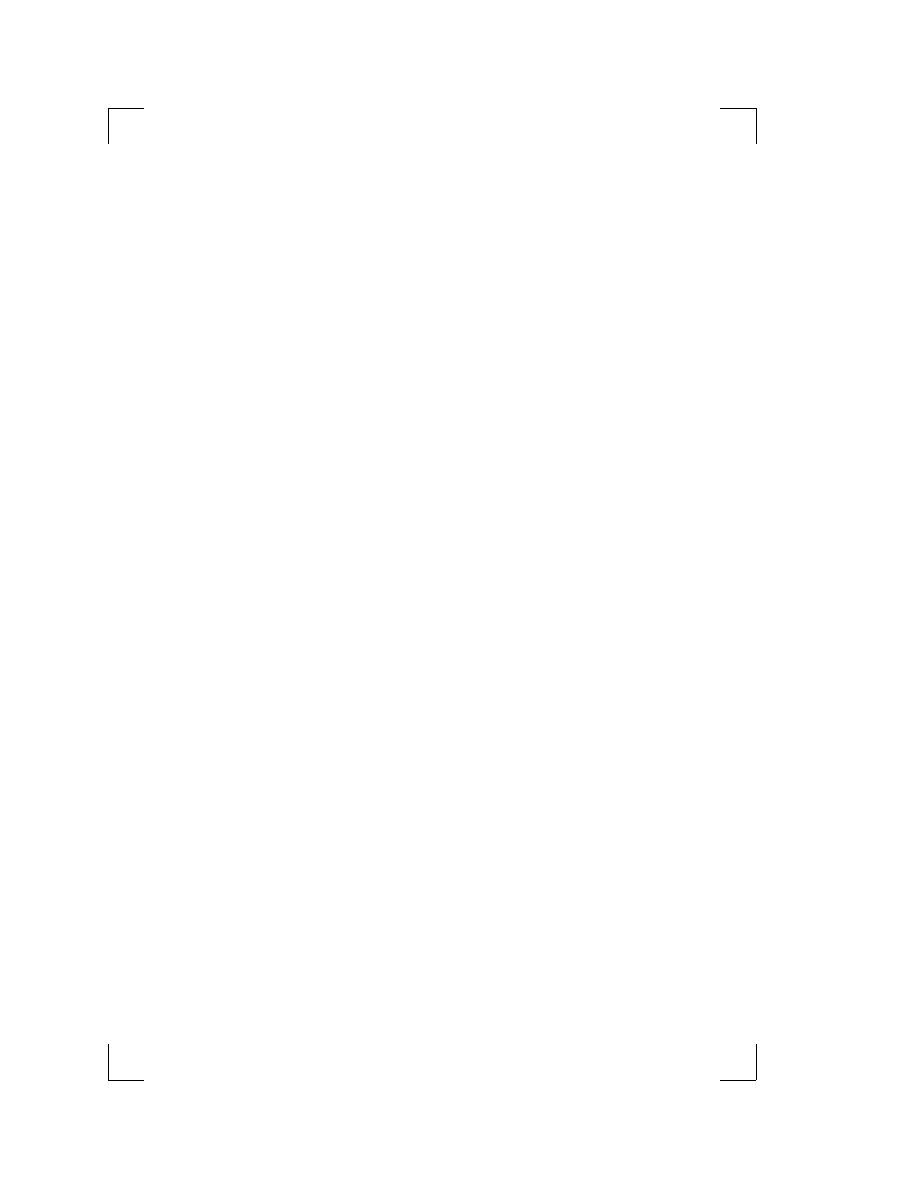

Table IV. Results of Hierarchical Moderated Regressions: The Moderating Effect of Job Control

and Supervisor Support on the Relationship Between the Intensity of Performance Monitoring and

Well-Being (N

= 347)

Emotional

exhaustion

Anxiety

Depression

Job satisfaction

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

1R

2

β

All regressions

Step 1: Controls

.00

—

.01

—

.03

—

.04

—

Step 2: Intensity of monitoring

.13

∗∗∗

.38 .12

∗∗∗

.36 .12

∗∗∗

.36 .13

∗∗∗

−.37

Regression 1

Step 3: Job control

.02

∗∗

−.16 .04

∗∗∗

−.23 .08

∗∗∗

−.33 .03

∗∗∗

.20

Step 4: Interaction term

.04

∗∗∗

−.71 .03

∗∗

−.58 .01

∗

−.41 .02

∗∗

.46

Regression 2

Step 3: Supervisor support

.02

∗∗

−.16 .02

∗∗

−.15 .06

∗∗∗

−.26 .21

∗∗∗

.49

Step 4: Interaction term

.01

∗

−.52 .02

∗∗

−.58 .02

∗∗∗

−.69 .00

.13

∗

p

< .05.

∗∗

p

< .01.

∗∗∗

p

< .001.

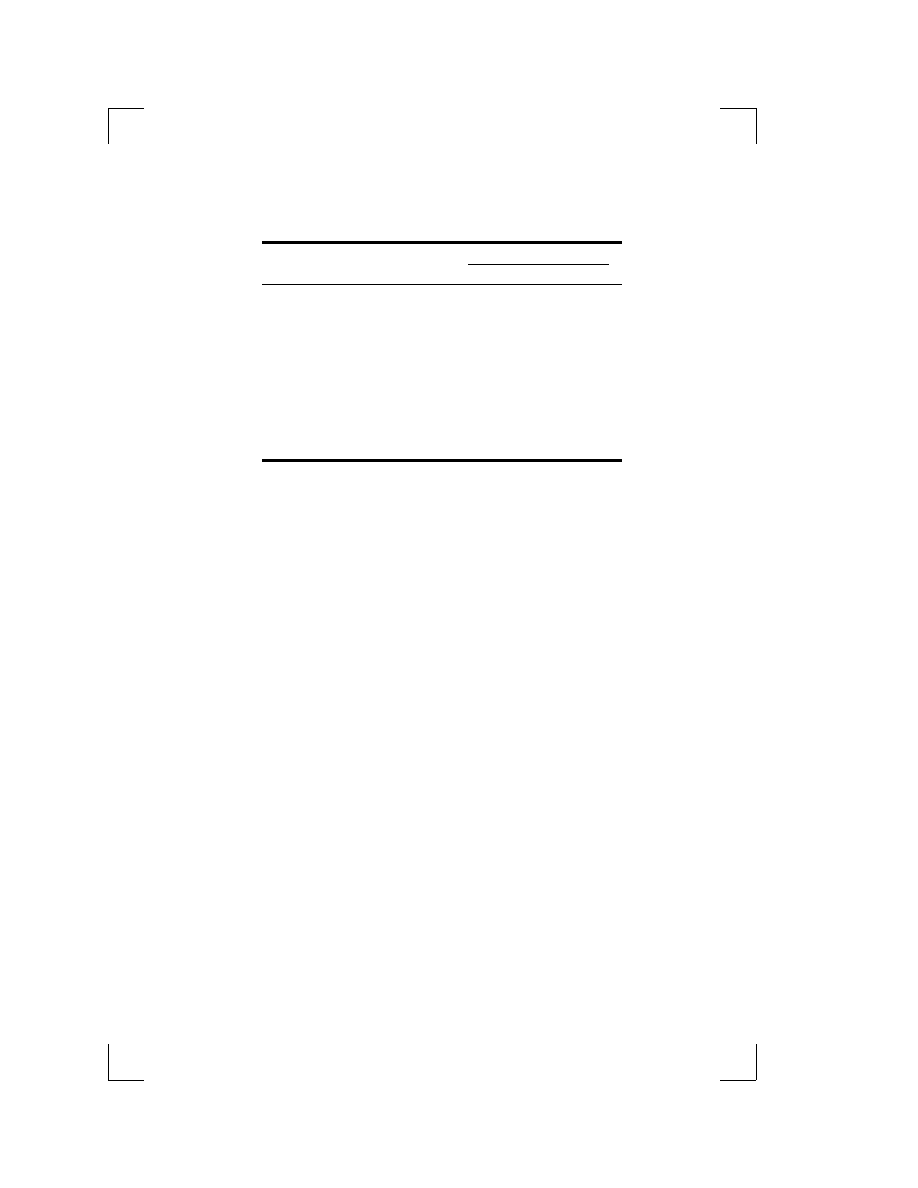

Table IV shows that there were significant interactions between job control

and the intensity of monitoring with regard to emotional exhaustion ( p

< .01),

anxiety ( p

< .01), depression (p < .05), and job satisfaction (p < .01). There

were also significant interactions between supervisor support and the intensity of

monitoring with regard to emotional exhaustion ( p

< .05), anxiety (p < .01), and

depression ( p

< .01). When plotted the interactions were in the form predicted.

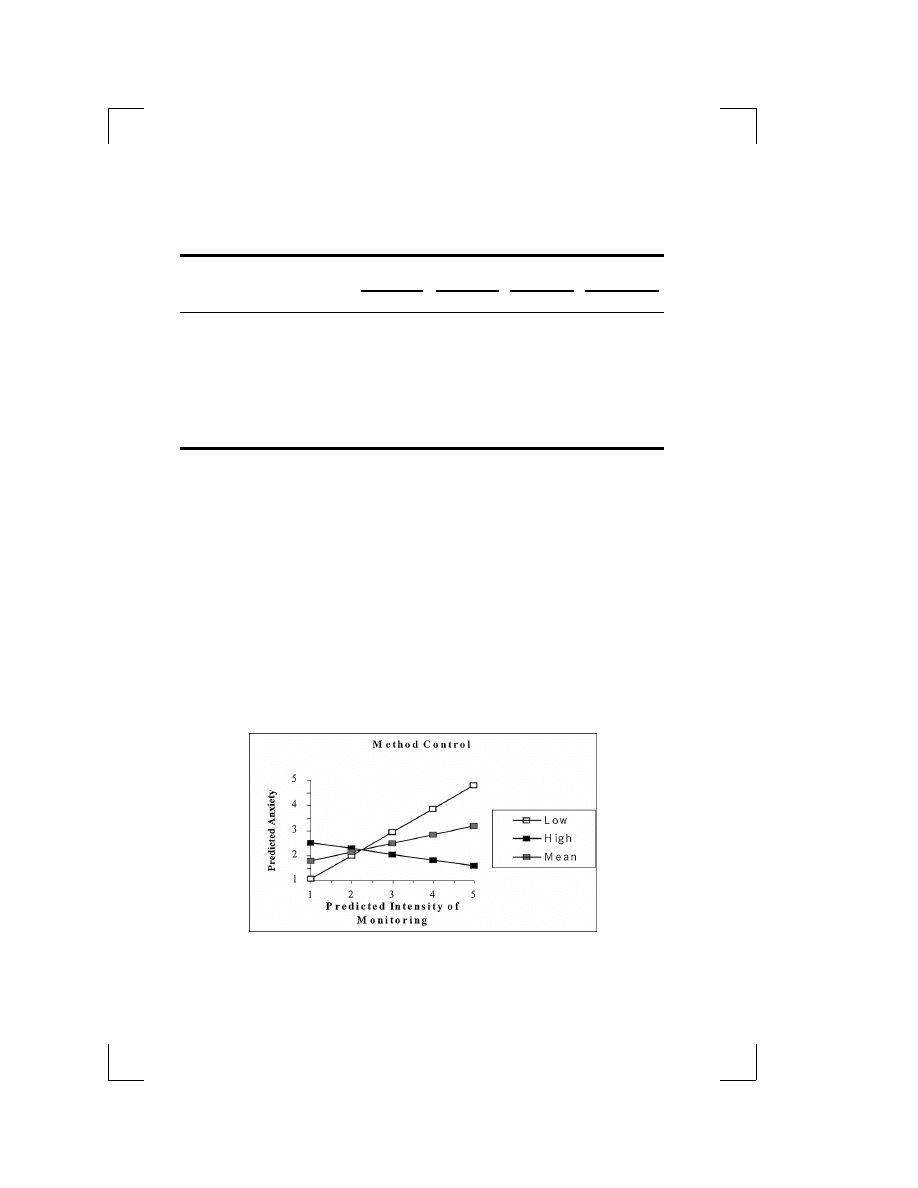

For example, from Fig. 1 it can be seen that when the intensity of monitoring

was high, it was associated with low levels of anxiety when job control was high.

When job control was low, high intensity was associated with high levels of anxiety.

Overall, the results from the moderated regression analysis offer partial support for

Hypothesis 6. Job control and supervisor support may thus act to buffer the effects

of the intensity of monitoring on well-being. Hypothesis 7 was not confirmed as

Fig. 1. Job-related anxiety as a function of method control and intensity

of monitoring.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

74

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

Table V. Stepwise Hierarchical Regressions of Effects of Performance Monitoring Characteristics and

Work Context Variables on Well-Being (N

= 347)

Step 2 variables entered stepwise

1R

2

β

Emotional exhaustion

1. Intensity of performance monitoring

.13

∗∗∗

.37

2. Supervisor support

.03

∗∗

−.17

3. Prob-solving demands

.02

∗∗

.15

4. Job control

.02

∗∗

−.15

Anxiety

1. Intensity of performance monitoring

.12

∗∗∗

.35

2. Job control

.04

∗∗∗

−.23

3. Supervisor support

.02

∗∗

−.14

4. Purpose of performance monitoring

.01

∗∗

−.13

Depression

1. Supervisor support

.13

∗∗∗

−.36

2. Job control

.08

∗∗∗

−.32

3. Intensity of performance monitoring

.03

∗∗∗

.20

Job satisfaction

1. Supervisor support

.32

∗∗∗

.57

2. Purpose of performance monitoring

.04

∗∗∗

.21

3. Job control

.02

∗∗∗

−.15

4. Prob-solving demands

.02

∗∗∗

−.14

5. Content of performance monitoring

.01

∗

.12

∗

p

< .05.

∗∗

p

< .01.

∗∗∗

p

< .001.

supervisor support did not moderate the relationship between the performance-

related content and beneficial-purpose of call monitoring and well-being.

To examine the relative effects of performance monitoring characteristics

and work context variables on well-being, a series of stepwise regressions were

conducted with each well-being measure as the dependent variable. At step one,

control variables were entered. At step two, all the performance monitoring and

work context variables were entered stepwise. From Table V, it is evident that the in-

tensity of monitoring has relatively higher associations with emotional exhaustion

(

β = .37, p < .01) and anxiety (β = .35, p < .01) than other performance moni-

toring variables and work context variables. Supervisor support has higher relative

levels of association with depression (

β = −.36, p < .01) and job satisfaction

(

β = .57, p < .01) than the other variables. Overall, supervisor support and job

control exhibit a more consistent and relatively higher level of association with the

well-being measures.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study show that performance monitoring in call centers is

an important antecedent of well-being and emotional labor, although the impact of

performance monitoring is not uniform. Thus, the various aspects of performance

monitoring had a positive and negative relationship with well-being. In particular,

and in line with previous work by Chalykoff and Kochan (1989) and Carayon

(1994), the performance-related content of monitoring was associated with low

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

75

depression and high job satisfaction but was unrelated to emotional exhaustion and

anxiety. This indicates that when clear performance criteria are developed and when

positive feedback is given regularly, the monitoring system will be associated with

greater well-being. The beneficial-purpose of monitoring was also associated with

low emotional exhaustion, low depression and high job satisfaction. Taken together,

these findings suggest that monitoring can play a role in improving well-being

when it is seen to be part of a broader system aimed at improving employees’

skills and abilities. It is the employee’s increased ability to cope with demand that

produces the improvements in well-being. The results do not support the argument

that monitoring is an intrinsically threatening and anxiety-provoking event.

Although the performance-related content and beneficial-purpose of monitor-

ing are positively associated with well-being, the perceived intensity of monitoring

had a strong negative association with all four measures of well-being. This nega-

tive relationship may be caused by the perceived intensity of the monitoring process

encouraging employees to focus inward on the effectiveness of their actions. This

may be beneficial in some circumstances, but it also means that greater effort

and attention is given to tasks that may normally be performed effortlessly. The

increase in efforts to regulate behavior (as evidenced by the positive relationship

between intensity and surface acting) means that more cognitive resources will be

devoted to the task at hand. Over time this may cause cognitive resources to be-

come depleted more rapidly, and it is this depletion of cognitive resources that has

been linked to higher anxiety and depression (Kuhl, 1992).

The finding that the intensity of monitoring accounts for much of the neg-

ative effects of monitoring on well-being addresses the fact that, although previ-

ous research has found that monitored employees reported worse well-being than

nonmonitored employees, it did not single out the performance monitoring char-

acteristics that caused this lower well-being. Indeed, the most consistent evidence

pointed to those characteristics that had positive effects on well-being. This study

has thus demonstrated that it is the perceived intensity of monitoring that accounts

for its negative effects. One issue arising from this is why do some people per-

ceive intensity to be higher than others? This study would seem to suggest that

it is not necessarily due to the frequency of monitoring, as there was no relation-

ship between the content and intensity of monitoring. Other individual, job, and

organizational factors may therefore play a part. For example, individual differ-

ences such as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997), personality and affectivity (Weiss &

Cropanzano, 1996), as well as differences in the perception of the nature and type

of performance criteria measured (i.e., some may be seen to be more intrusive)

may play a role.

A further point worth raising is that the performance-related content of mon-

itoring has specific effects on well-being. Thus, according to Warr’s typology

of employee well-being (Warr, 1996), the performance-related content of mon-

itoring tends to be associated with pleasurable and aroused states of well-being

(e.g., enthusiastic, cheerful, happy) rather than unpleasurable aroused states (e.g.,

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

76

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

anxious, tense) or unpleasurable unaroused states (e.g., gloomy, fatigued, sad). The

beneficial-purpose and intensity of monitoring had more global affects on well-

being. However, it can also be noted that, from the examination of relative effects,

the intensity of monitoring was more highly associated with unpleasant aroused

states (e.g., anxiety) and unpleasant unaroused states (e.g., emotional exhaustion).

The second main finding of this paper is that performance monitoring can be

an antecedent of emotional labor (i.e., manifest as emotional dissonance followed

by surface acting or deep acting) in call centers. Thus, emotional dissonance was

found to mediate the relationship between the beneficial purpose of monitoring and

surface acting. Of particular interest here are the reasons why a beneficial purpose

of monitoring may act to reduce emotional dissonance. One explanation is that a

beneficial purpose may lower an employee’s anxiety about being punished, or it

may increase their enthusiasm. In either case, the effect should lead to a reduction

in emotional dissonance and subsequent efforts to regulate emotion. Emotional

dissonance also mediated the relationship between the intensity of monitoring

and surface acting. This might be explained by the fact that the perception of

intense monitoring may make the person more aware of their emotional states and,

consequentially, of any dissonance that occurs.

In keeping with earlier research, emotional dissonance and surface acting were

also found to be directly and negatively associated with well-being (Zapf et al.,

1999). Thus, while the relationship between performance monitoring, emotional

labor, and well-being was not in the hypothesized form, emotional dissonance and

surface acting do seem to play a role in this relationship. However, it should be noted

that, against expectations, deep acting was unrelated to emotional dissonance. A

possible reason for this is that deep acting is a response to emotional dissonance

that then reduces emotional dissonance, which has the effect of cancelling out any

relationship that might be found when general levels of emotional dissonance are

measured. This points to the difficulty of studying emotional labor, particularly

through survey-based methods (Grandey, 2000). Indeed, research is clearly needed

that measures both the dissonance felt before attempts to regulate emotion and the

dissonance felt after attempts to regulate emotion. This might be best achieved

through experience sampling methodologies (Totterdell & Parkinson, 1999; Weiss,

Nicholas, & Daus, 1999).

An examination of how the work context affected the relationship between

performance monitoring and well-being revealed only small interaction effects and

no mediated effects. In particular, job control and supervisor were found to play a

small role in buffering the impact of the perceived intensity of performance mon-

itoring on well-being. One surprising finding was that supervisor support neither

mediated nor moderated the relationship between the content and purpose of mon-

itoring and well-being. The reasons for this are unclear, but it does indicate that,

in this context, variation within the performance-related content and the beneficial

purpose of monitoring are probably caused by other factors such as departmental

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

77

policies and culture. For example, departmental policies may strongly dictate the

content of performance monitoring in a call center and the supervisor’s style of

management may therefore have little effect on it.

With regard to relative effects, the intensity of monitoring appears to have

stronger effects on emotional exhaustion and anxiety than the other work context

variables or performance monitoring variables that were included in this study.

In contrast, supervisor support had a higher level of association with well-being

than the performance-related content and beneficial-purpose of monitoring. This

is in line with Carayon’s study (Carayon, 1994) that found that the work context

variables had higher associations with well-being than content-based performance

monitoring variables (it must be noted that this study did not examine the intensity

of monitoring).

The strong relationship between the perceived intensity of monitoring and

well-being has an important practical implication, namely, that every effort should

be made to reduce the perception that monitoring is intense. It is possible that the

perception of intensity is linked to the number and type of performance measures

used. Lowering the number and changing the type of performance measures may

reduce the perception that every aspect of behavior is monitored and decrease the

monitoring system’s pervasiveness. It might be argued, however, that any reduction

in the number of criteria may adversely affect the effectiveness of the performance

appraisal process. In response, it can be argued that feelings of intensity may

result in the performance appraisal criteria being devalued; and criteria need to be

valued if they are to be of use. Thus, removing nonessential performance criteria

should reduce intensity and improve the performance appraisal process. Job control

should also be increased by reducing restrictions on what an employee can say (this

is particularly pertinent to call centers that use scripts) and by involving employees

in the design of the monitoring system (Chalykoff & Kochan, 1989).

A further practical implication is that the monitoring system should involve

frequent and positive feedback and be based on clear performance criteria. More-

over, performance monitoring should be recognized as being part of a system that

aims to develop employees’ skills and performance and be designed so that it is

closely linked to other support and development practices such as performance

appraisal and coaching. By linking monitoring to these practices, the likelihood

of monitoring being accepted, and its positive impact on well-being, should in-

crease. The finding that supervisors can play a role in reducing the negative effects

of intensity on well-being implies that they should be given training on conduct-

ing performance appraisals. The need to invest in the training of supervisors is

acutely important in call centers, where CSAs are often promoted from within

to this role. This can lead to a situation where new supervisors have to deal

with sensitive issues (such as giving feedback on performance) under demand-

ing conditions, but are relatively inexperienced and ill equipped to cope with such

tasks.

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

78

Holman, Chissick, and Totterdell

Although the present study has a number of relevant findings, it is appropriate

to highlight several limitations. The first is that the study is cross-sectional and

the direction of causality cannot be confirmed. Second, common method variance

presents a potential source of invalidity to substantive interpretation. However,

while such biases can cause self-ratings to be associated with self-reported out-

comes, they would act against differential effects of the kind observed. A tendency

to respond positively or negatively would result in associations among all the vari-

ables but not in certain performance monitoring variables being positively related

to well-being and others negatively associated. Only demand characteristics of a

very sophisticated kind would artifactually create such effects. The use of self-

ratings might also be seen as problematic. Third, questions can be raised about the

extent to which these findings will generalize to organizations other than call cen-

ters. The prominence of performance monitoring in call centers may exacerbate the

strength of relationships found. In other organizations the effects of performance

monitoring may be much lower.

Future research would clearly benefit from being longitudinal and multi-

method. Equally important is the need to ground future research in this area in the-

ories of emotional regulation (e.g., Gross, 1998), theories that specify the structure,

causes and consequences of affective experiences at work (Weiss & Cropanzano,

1996) and in theories that posit alternative mechanisms (Karasek & Theorell,

1990). Thus, emotional labor is only one way that emotions might be regulated at

work in response to performance monitoring. Performance monitoring may affect

a whole host of regulatory strategies and these need to be addressed (Parkinson &

Totterdell, 1999). The causes of emotions at work could be strengthened by study-

ing a wider variety of “content” performance monitoring characteristics (e.g.,

source, target, the inclusion of positive and negative forms of feedback) and “moni-

toring cognitions” (e.g., trust, fairness; Stanton, 2000). The individual, job, and or-

ganizational factors that affect the perception of performance monitoring intensity

require further study. Another important mechanism that can be referred to as “the

performance and skill development” mechanism that is, how improvements in skill

increase employees’ ability to cope with work demands and the effects this has on

self-efficacy and well-being (Bandura, 1997; Jenkins & Maslach, 1994; Karasek &

Theorell, 1990). Future research should also examine the real-time consequences

(e.g., affect, customer service, emotional displays) of monitoring using diary meth-

ods or similar (Totterdell & Parkinson, 1999; Weiss, Nicholas, & Daus, 1999).

In summary, this study has further illuminated the relationship between per-

formance monitoring, work context, and well-being. In particular, it has shown

that performance monitoring as an important antecedent of well-being and one

that has both a positive and negative impact on well-being. However, the exact

mechanisms by which this occurs requires further research. This study has also

demonstrated that the work context can moderate the relationship between the

intensity of monitoring and well-being, although the effect of work context may

be relatively small. In all, this suggests that it is critical for practitioners, especially

P1: FHD/GRA/LOV

P2: GVG/GCZ

QC:

Motivation and Emotion [me]

pp444-moem-370754

April 9, 2002

7:34

Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999

Performance Monitoring, Emotional Labor and Well-Being

79

in a call center environment, to situate performance monitoring within a broader

system of employee development and to ensure that the monitoring system is not

viewed as intense.

REFERENCES

Aiello, J. R., DeNisi, A. S., Kirkoff, K., Shao, Y., Lund, M. A., & Chomiak, A. A. (1991). The impact

of feedback and individual/group monitoring on work effort. Paper presented at the American

Psychological Society, Washington.

Aiello, J. R., & Kolb, K. J. (1995). Electronic performance monitoring and social context: Impact on

productivity and stress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 339–353.

Aiello, J. R., & Shao, Y. (1993). Electronic performance monitoring and stress: The role of feedback and

goal setting. In M. J. Smith & G. Salavendy (Eds.), Human–computer interaction: Applications

and case studies (pp. 1011–1016). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Aiello, J. R., & Svec, C. M. (1993). Computer monitoring and work performance: Extending the social

facilitation framework to electronic presence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 537–

548.

Alder, G. S. (1998). Ethical issues in electronic performance monitoring: A consideration of deonto-

logical and teleological perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 729–743.

Axtell, C., Holman, D., Wall, T., Waterson, P., Harrington, E., & Unsworth, K. (2000). Shopfloor

innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and

Organisational Psychology, 73, 265–285.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

Baron, R. B., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psycho-

logical research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Belt, V., Richardson, R., & Webster, J. (1999, March 19). Smiling down the phone: Women’s work in

Telephone Call Centres. Call Centre Conference, London School of Economics.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives

of “people work.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 17–39.