Abstract

SCHIRACK, ANDRIANA VAIS. The Effect of Microwave Blanching on the Flavor

Attributes of Peanuts. (Under the direction of K.P. Sandeep.)

The use of microwave technology as an alternative blanching method for

peanuts could potentially reduce energy costs and processing time, and lead to

products with better nutrient retention. However, an off-flavor was found in peanuts

which were microwave-blanched at high temperatures. As a result, the objective of

this research has been to determine the impact of different microwave blanching

parameters on the properties of roasted peanuts, and to characterize the off-flavor

observed during high-temperature microwave blanching using a descriptive sensory

panel and analysis of volatile flavor compounds. The processing parameters best

suited for microwave blanching of peanuts were determined based on energy

absorbed during processing, internal and surface temperatures, loss in moisture

content, and blanchability. The best blanchability resulted from higher process

temperatures and lower final moisture content. However, peanuts which reached

the highest internal temperatures during blanching also developed an off-flavor,

which was characterized by increased intensities of stale/floral and burnt/ashy notes.

Solvent extraction / solvent assisted flavor evaporation (SAFE), gas

chromatography-olfactometry (GC/O), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

(GC/MS), aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA), threshold testing, and model

systems were used to examine the chemical compounds which may be responsible

for this microwave-related off-flavor. Analysis revealed an increased formation of

guaiacol, phenylacetaldehyde, and 2,6-dimethylpyrazine in the off-flavored peanuts

as compared to a process control, which led to the burnt and stale/floral

characteristics noted by descriptive sensory panel. These compounds were only a

small fraction of over 200 aroma-active compounds which were found to contribute

to roasted peanut flavor using GC/O. This research illustrates the importance of the

relative concentrations of the many aroma-active compounds found in peanuts.

These findings could aid in training sensory panels to evaluate processing-related

off-flavors, because guaiacol and phenylacetaldehyde could be used as chemical

standards to define the burnt/ashy and stale/floral off-flavors which can occur during

high temperature processing. Through this project, it was determined that it is

possible to achieve acceptable blanchability in peanuts using microwave blanching

while minimizing the possibility of an off-flavor.

ii

Dedicated to my husband, Pete

iii

BIOGRAPHY

Andriana Schirack is originally from Columbus, Ohio, where she attended

Ohio State University as an OSU Medalist Scholar and National Merit Scholar.

Andriana graduated with a B.S. in Food Science in December, 1997 after completing

an internship in product development of infant formula with Ross Laboratories. In

2000, Andriana completed a master’s program in Food Science at North Carolina

State University with a minor in statistics. During this time, she was also employed

as an aseptic processing technician in the dairy plant. From 2000 to 2003, Andriana

was an Assistant Food Scientist at Jim Beam Brands in Clermont, Kentucky, where

she was trained in analytical chemistry for technical problem solving and developed

new beverages for global launch as part of the product development team. She

began her Ph.D. program in the summer of 2003 under the direction of Dr. K.P.

Sandeep, and has been very active in the national IFT Student Association and the

NCSU Food Science Club. Andriana and her husband, Pete, will move to

Minneapolis, MN where she will begin work at General Mills as an R&D Scientist.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to my advisor, Dr. K.P. Sandeep, and my committee members, Dr.

MaryAnne Drake, Dr. Tim Sanders, and Dr. Donn Ward for their guidance. Also,

thanks to the many family and friends who have supported me in the past several

years. Most of all, a huge thanks to my husband, Pete – for making this possible.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Tables ......................................................................................................viii

List of Figures ....................................................................................................... x

Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ 1

References.................................................................................................... 7

Chapter 2. Literature Review ............................................................................. 10

Composition of Peanuts .............................................................................. 11

Overview of Peanut Production................................................................... 12

Harvesting................................................................................................... 13

Curing ......................................................................................................... 14

Effect of Peanut Immaturity......................................................................... 18

Storage ..................................................................................................... 20

Blanching .................................................................................................... 21

Roasting...................................................................................................... 26

Microwave Processing ................................................................................ 28

Mechanisms of Action ................................................................................. 30

Dielectric Properties .................................................................................... 32

Microwave Blanching of Peanuts ................................................................ 35

Flavor Chemistry of Peanuts....................................................................... 36

Flavor Production During Roasting ............................................................. 37

Roasting Parameters Effect on Flavor ........................................................ 43

Flavor Research in Other Nuts.................................................................... 45

Precursors to Roasted Notes ...................................................................... 46

Off-flavors in Peanuts ................................................................................. 47

Flavors Due to Lipid Oxidation .................................................................... 48

Off-flavors Due to Anaerobic Respiration.................................................... 52

Fruity Fermented Off-flavor ......................................................................... 55

Off-flavors Due to External Contamination.................................................. 57

Dark Soured Aromatic Off-flavor ................................................................. 57

Methods of Flavor Analysis ......................................................................... 58

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) .................................. 64

Correlation to Quality and Sensory ............................................................. 65

Gas Chromatography – Olfactometry (GC-O)............................................. 66

GC-O Applications ...................................................................................... 69

Sensory Evaluation ..................................................................................... 70

Descriptive Sensory Analysis...................................................................... 74

Project Objectives ....................................................................................... 76

Abbreviations .............................................................................................. 78

Symbols ...................................................................................................... 80

vi

References.................................................................................................. 81

Chapter 3. Effect of Processing Parameters on the Temperature and

Moisture Content of Microwave-Blanched Peanuts ............................................ 90

Abstract....................................................................................................... 91

Introduction ................................................................................................ 91

Materials and Methods................................................................................ 94

Results and Discussion............................................................................... 97

Energy Absorption .................................................................................. 97

Peanut Temperature ............................................................................... 98

Change in Moisture Content ................................................................. 101

Blanchability.......................................................................................... 102

Conclusions .............................................................................................. 104

Acknowledgments..................................................................................... 105

Abbreviations ............................................................................................ 106

References................................................................................................ 107

Tables and Figures ................................................................................... 109

Chapter 4. Impact of Microwave Blanching on the Flavor of Roasted

Peanuts............................................................................................................. 118

Abstract..................................................................................................... 119

Introduction ............................................................................................... 120

Materials and Methods.............................................................................. 123

Peanuts................................................................................................. 123

Processing Experiments ....................................................................... 123

Temperature Measurement During Blanching ...................................... 124

Moisture Content Analysis .................................................................... 125

Sensory Evaluation ............................................................................... 125

Data Analysis ........................................................................................ 126

Results and Discussion............................................................................. 127

Sensory Analysis .................................................................................. 127

Temperature Profiles and Change in Moisture Content ....................... 128

Conclusions .............................................................................................. 130

Abbreviations ............................................................................................ 130

Acknowledgments..................................................................................... 131

References................................................................................................ 132

Table Legends .......................................................................................... 135

Chapter 5. Characterization of Aroma-Active Compounds in Microwave

Blanched Peanuts............................................................................................. 141

Abstract..................................................................................................... 142

Introduction ............................................................................................... 143

vii

Materials and Methods.............................................................................. 145

Peanuts................................................................................................. 145

Chemicals ............................................................................................. 147

Static Headspace Gas Chromatography............................................... 147

Solvent Extraction with Solvent Assisted Flavor Evaporation (SAFE)... 148

Gas Chromatography/Olfactometry (GC/O) .......................................... 149

Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)............................. 150

Identification of Odorants ...................................................................... 151

Quantification of Odorants .................................................................... 151

Threshold Testing ................................................................................. 152

Sensory Evaluation of Peanut Models .................................................. 153

Results and Discussion............................................................................. 154

Sensory analysis................................................................................... 154

Static Headspace Analysis.................................................................... 155

Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry ...................................................... 156

Quantification ........................................................................................ 159

Threshold Determination....................................................................... 160

Model Systems ..................................................................................... 163

Conclusion ................................................................................................ 165

Acknowledgments..................................................................................... 165

References................................................................................................ 167

Chapter 6. Conclusions and Future Work ........................................................ 178

Conclusions .............................................................................................. 179

Future Work .............................................................................................. 182

References................................................................................................ 184

Appendices ....................................................................................................... 185

Appendix 1: Analysis of Peanut Volatiles by Solvent Extraction, SAFE,

GC-O, and GC-MS.................................................................................... 186

Appendix 2: Quantification of Peanut Volatiles ........................................ 192

Appendix 3: Summary of Aroma-Active Compounds Found in

Peanut Samples Using Aroma Extract Dilution Analysis (AEDA).............. 194

viii

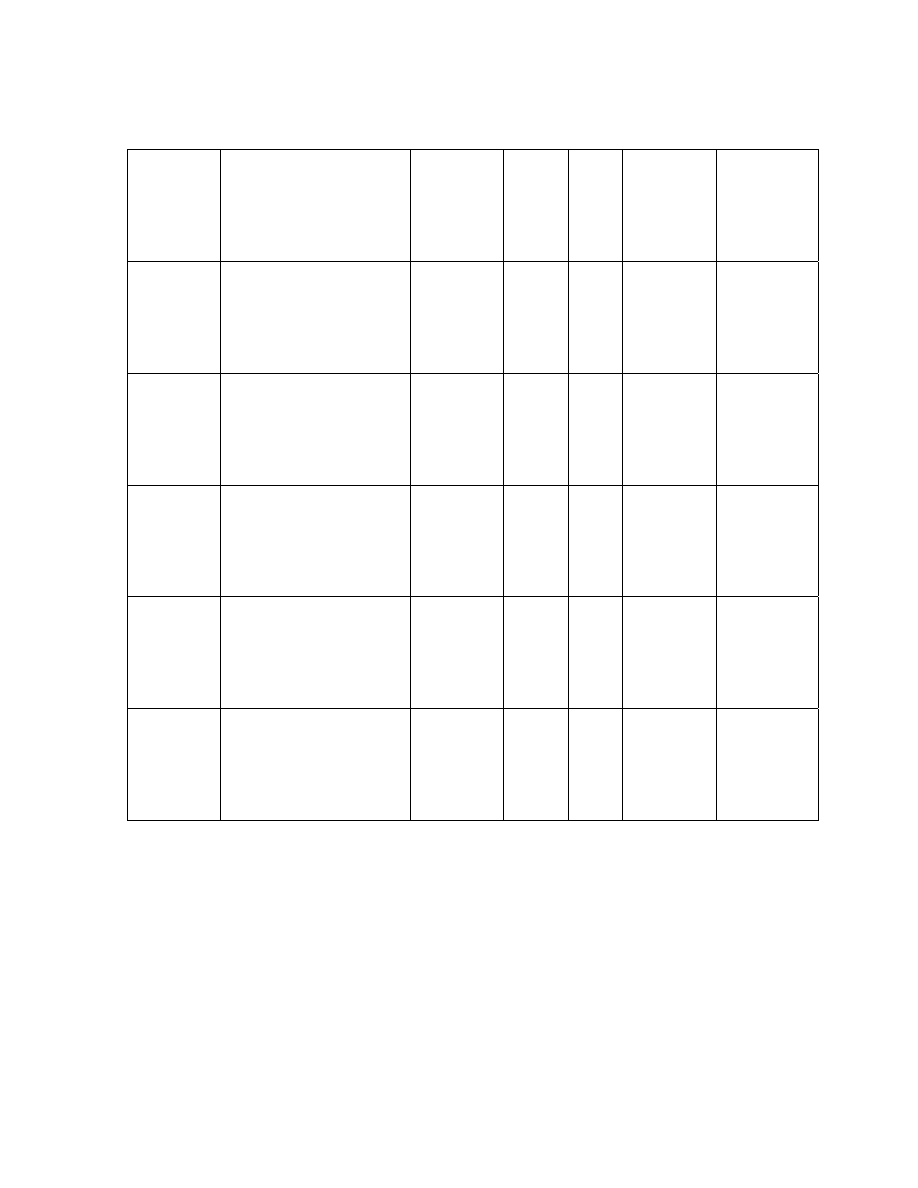

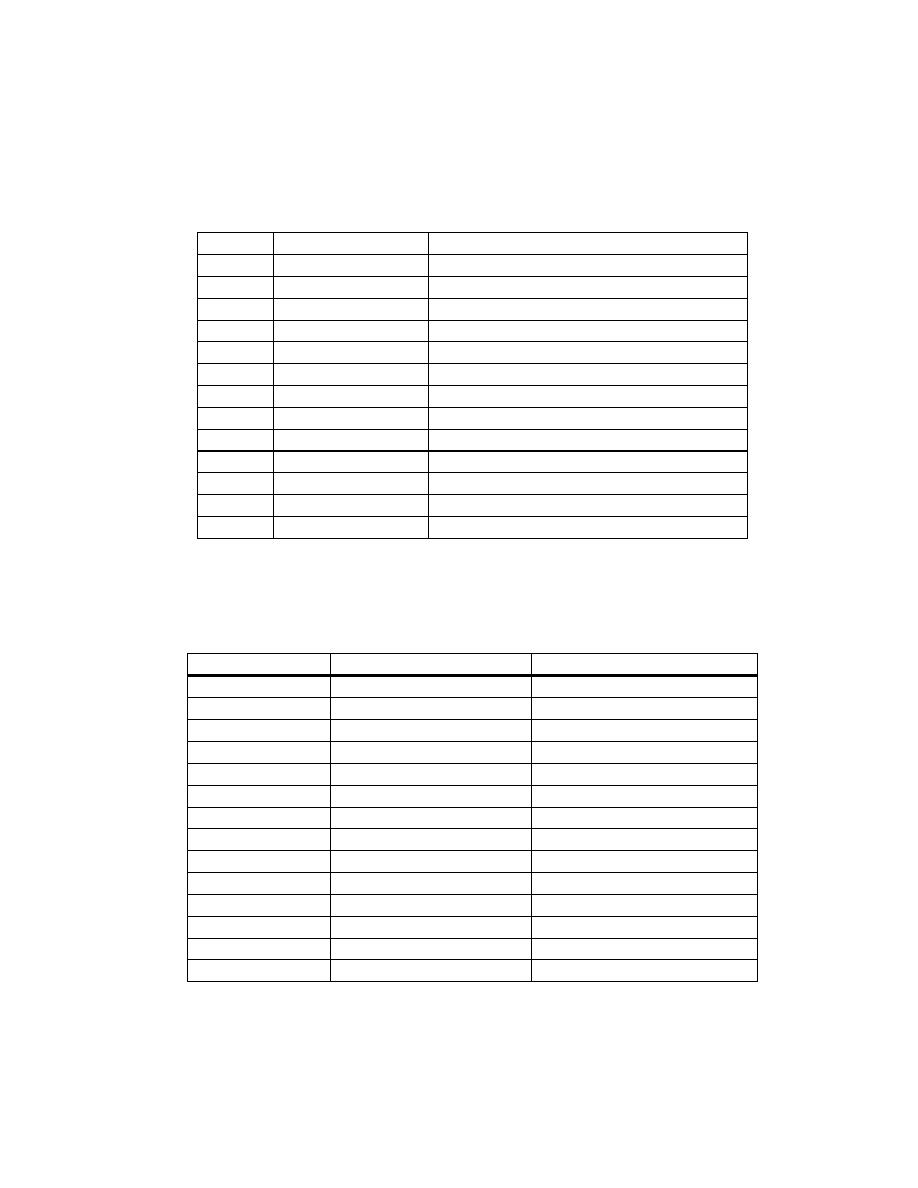

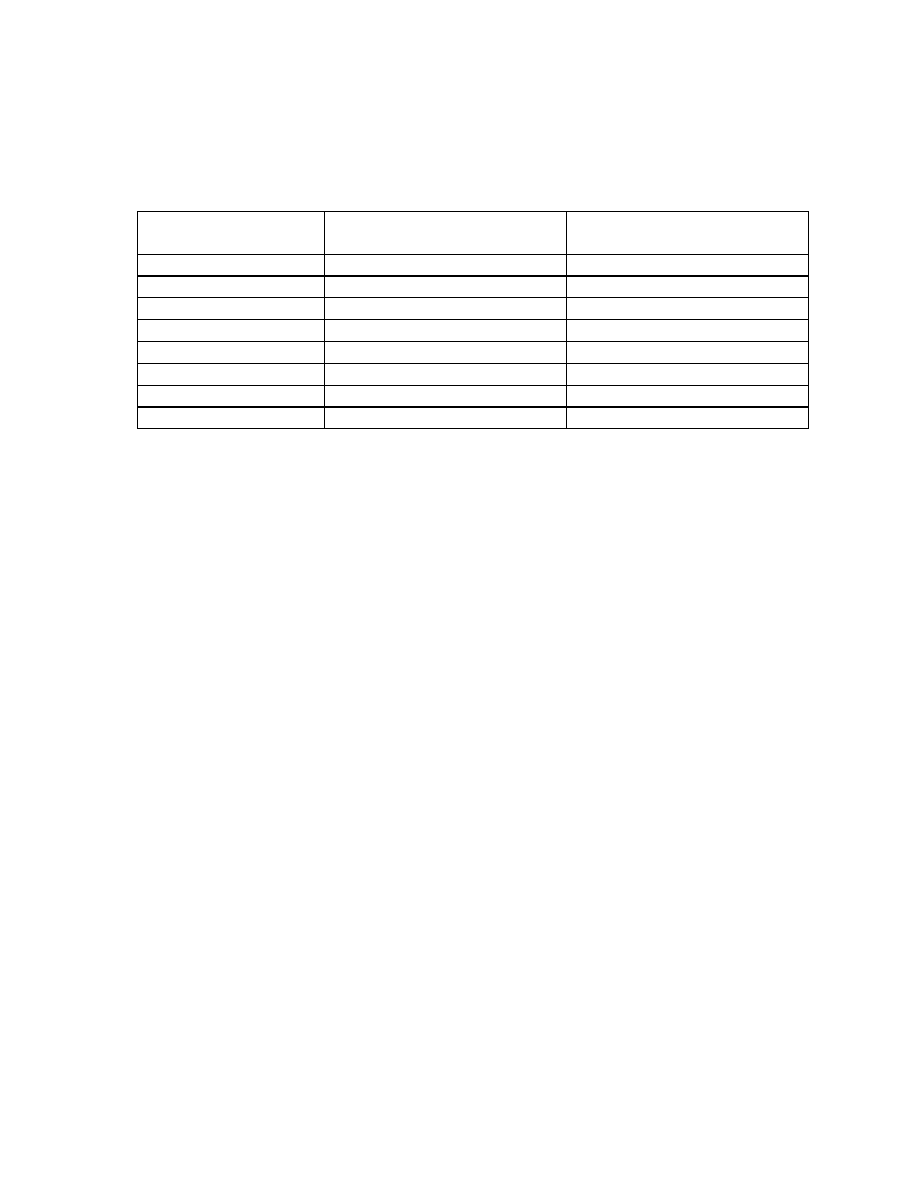

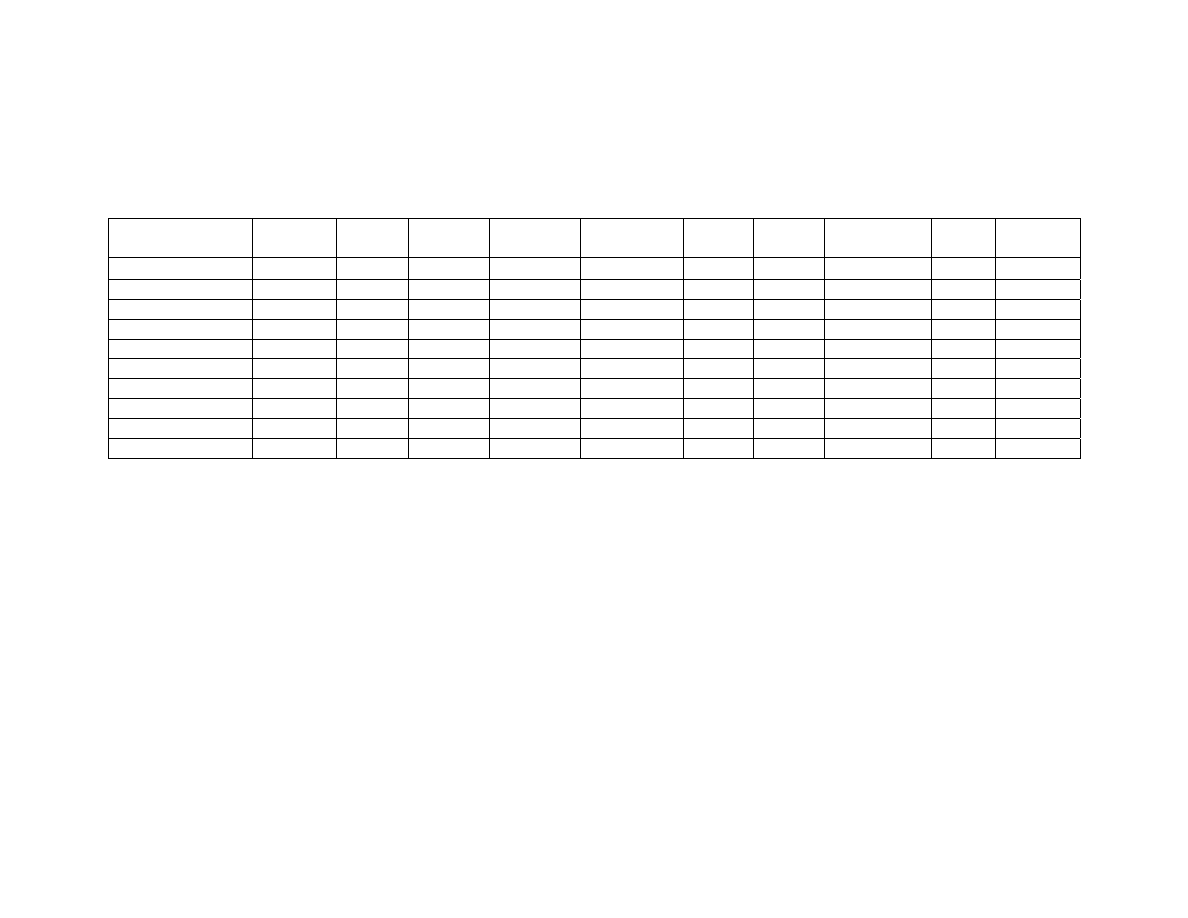

LIST OF TABLES

Chapter 2

Table 1

Peanut Volatile Analysis by Gas Chromatography .......................... 63

Table 2

Lexicon of Peanut Flavor Descriptors (Johnsen et al., 1988) .......... 72

Chapter 3

Table 1

Processing Parameters During Microwave Blanching of

Peanuts ....................................................................................... 109

Table 2

Means by Treatment of Internal Temperatures of Peanuts

During

Microwave

Blanching ....................................................... 109

Table 3

Maximum Internal Temperatures of Peanuts by Treatment

During

Microwave

Blanching ....................................................... 110

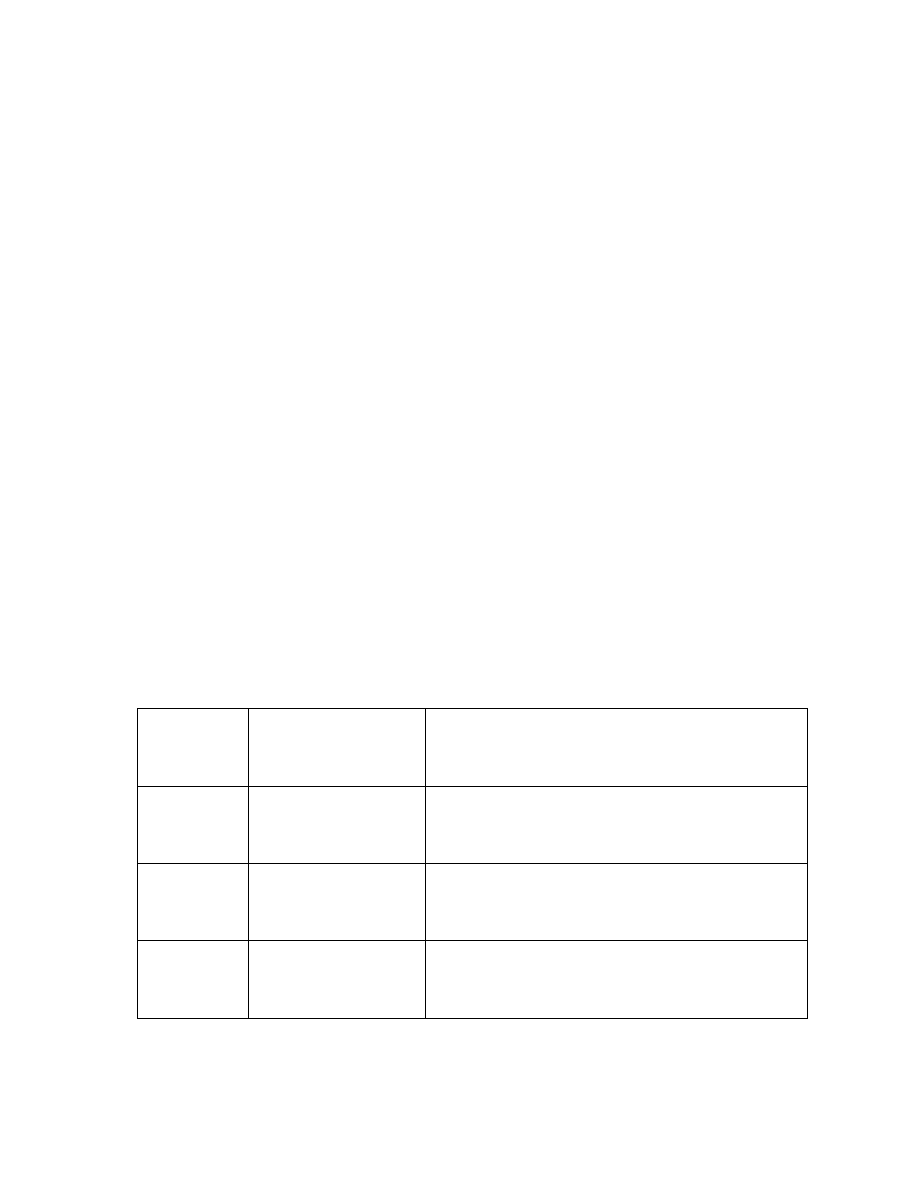

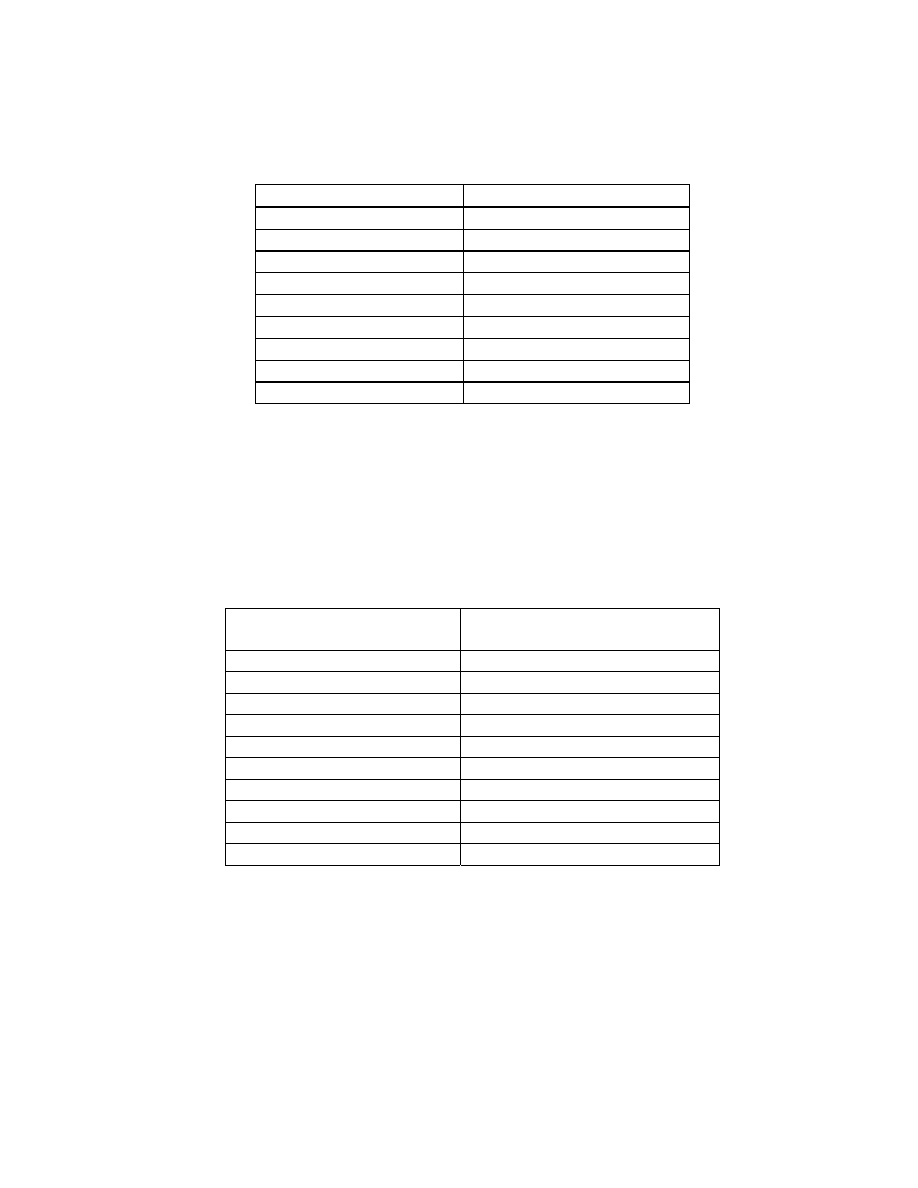

Chapter 4

Table 1

Microwave Application Parameters and Resulting Blanching

Efficiency ....................................................................................... 136

Table 2

Lexicon of Peanut Flavor Descriptors (Modified From Johnsen

et al., 1988; and Sanders et al., 1989) .......................................... 137

Table 3

Means Separation of Blanching Treatments by Sensory

Attribute......................................................................................... 138

Table 4

Correlations Between Peanut Flavor Attributes............................. 139

Table 5

Maximum Internal Temperature in Peanuts by Treatment ............ 140

Table 6

Moisture Content of Peanuts After Blanching................................ 140

Chapter 5

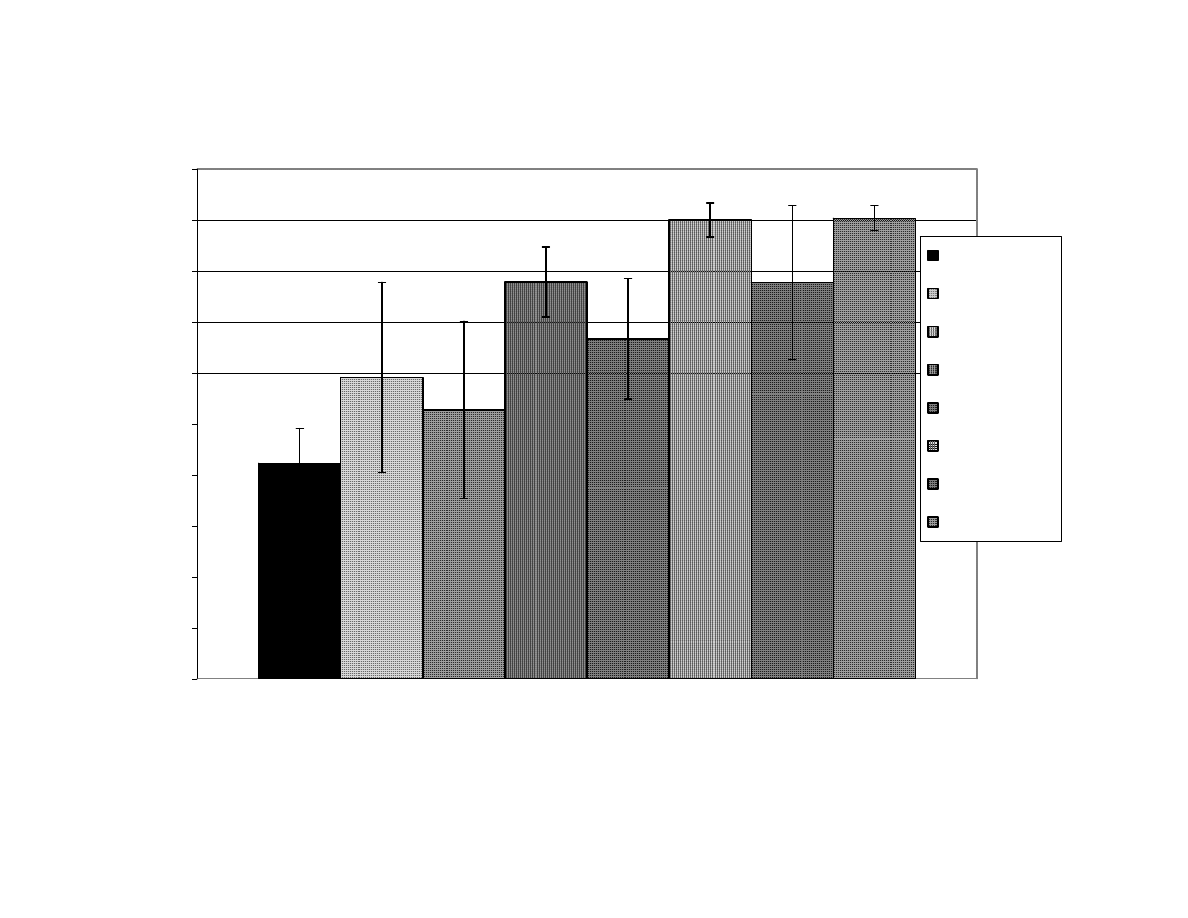

Table 1

Effect of High Temperature Microwave Blanching on Sensory

Attributes ..................................................................................... 172

Table 2

Model System Concentrations in Reference Peanut Paste……...173

ix

Table 3

High Impact Aroma-Active Compounds in Peanuts as

Determined

by AEDA .................................................................. 174

Table 4

Relative Abundance of Selected High Aroma Impact

Compounds

in

Peanuts ............................................................... 176

Table 5

Quantification, Sensory Orthonasal Threshold Values, and Odor

Activity Values of Selected Compounds in Peanuts .................... 177

Appendices

Table 1

Aroma Active Compounds in Reference Peanuts Detected by

Gas

Chromatography-Olfactometry............................................. 194

Table 2

Aroma-Active Compounds in Microwave-Blanched Peanuts

Detected by Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry......................... 201

x

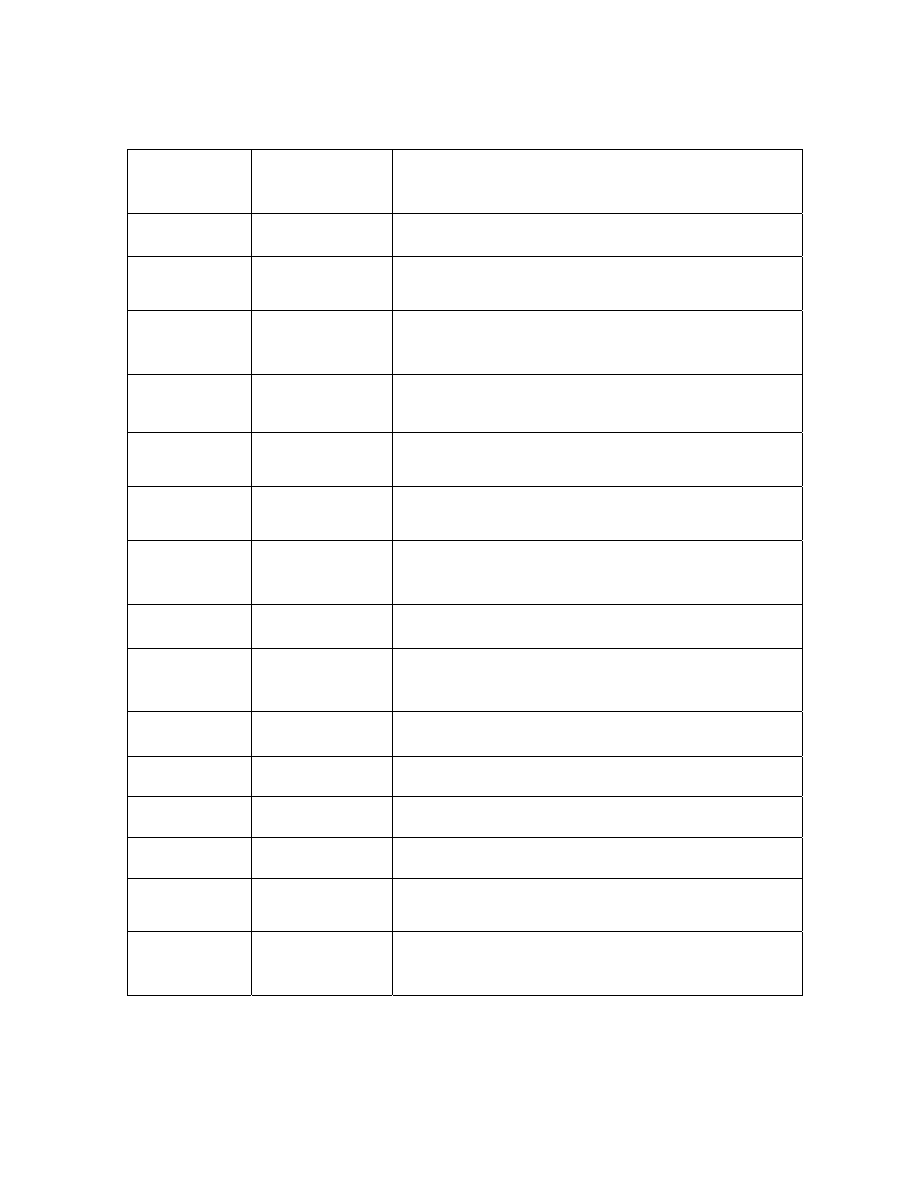

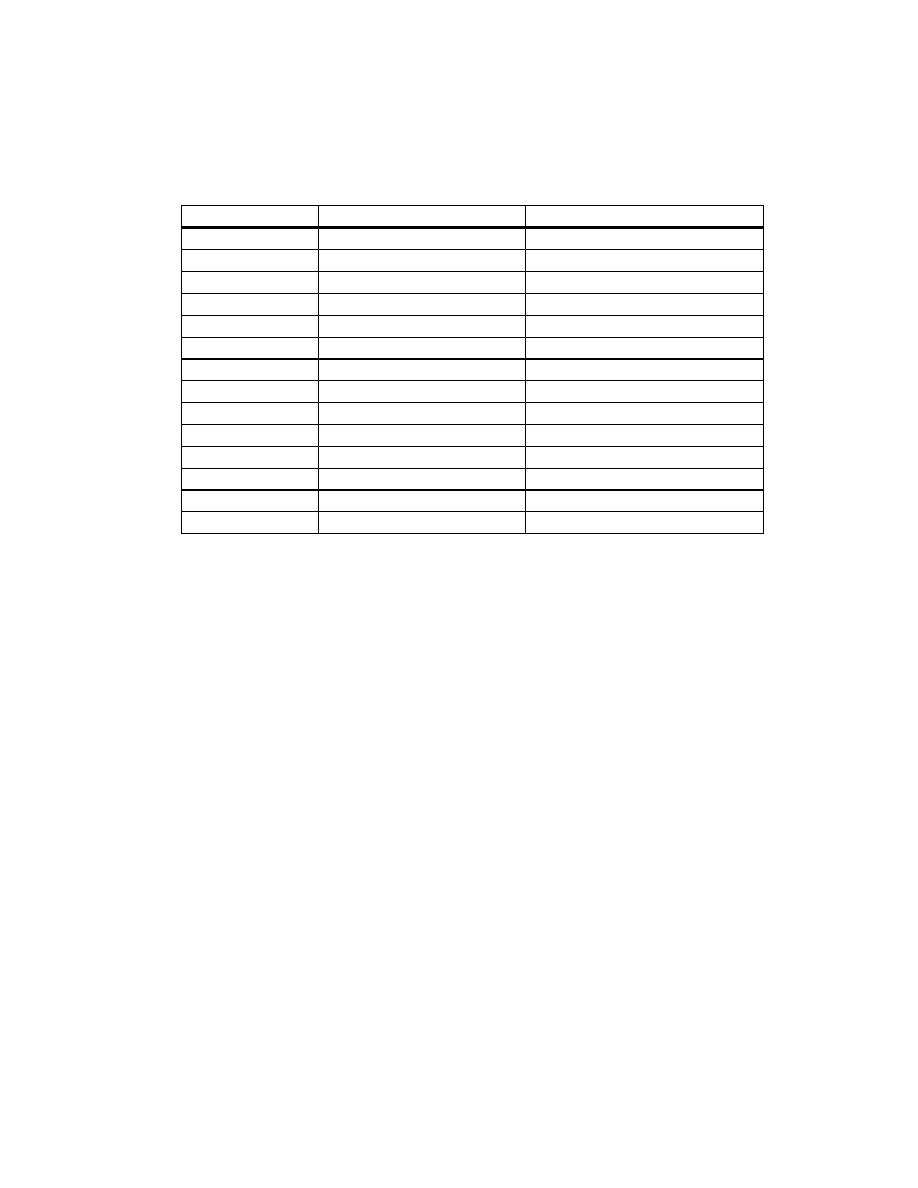

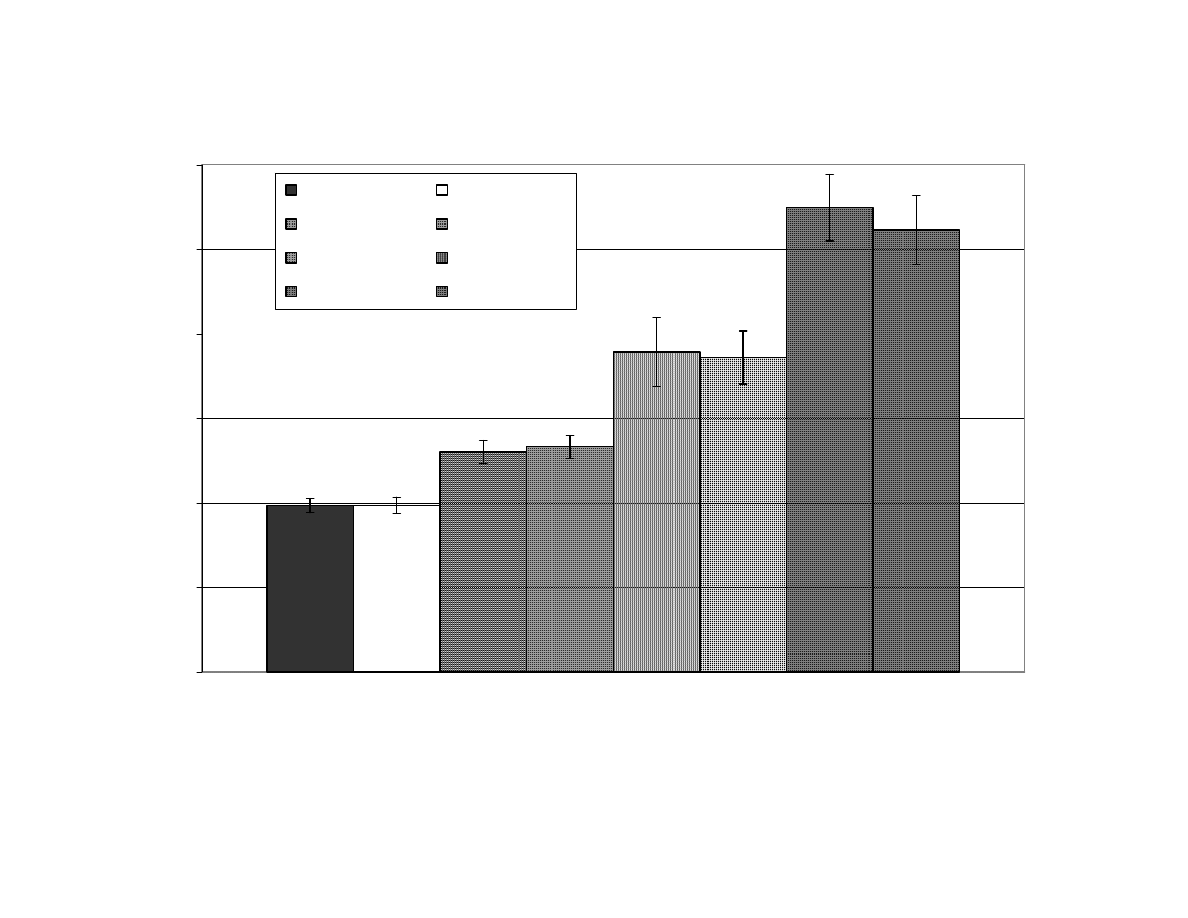

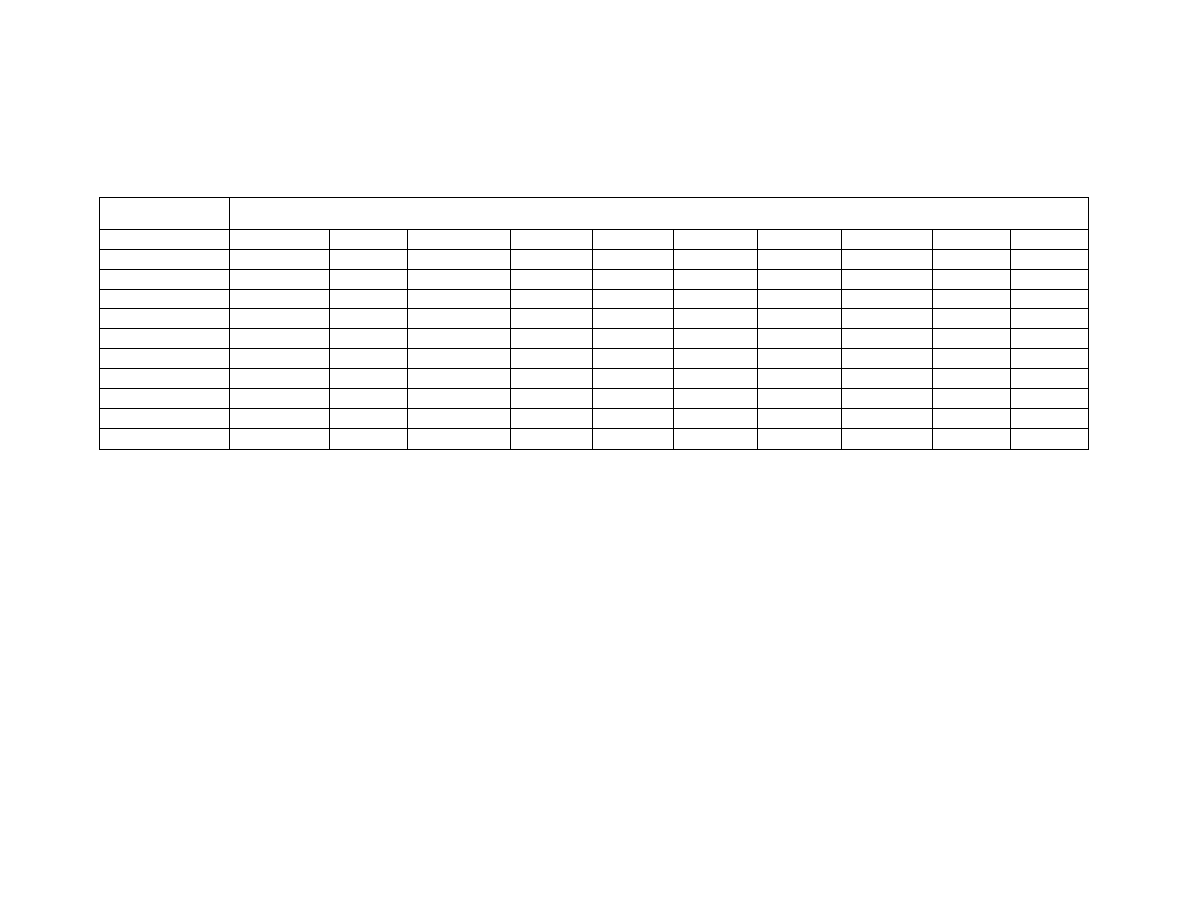

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

Chapter 3

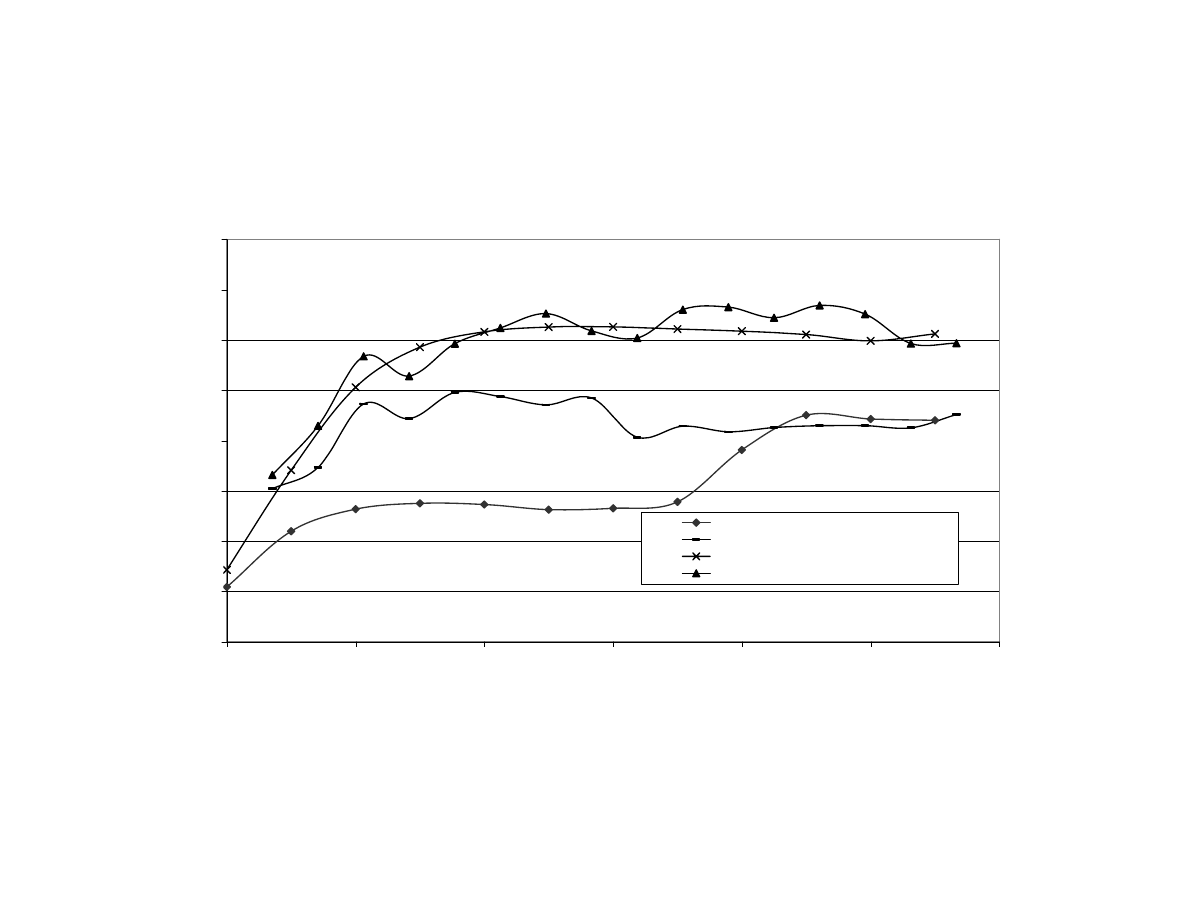

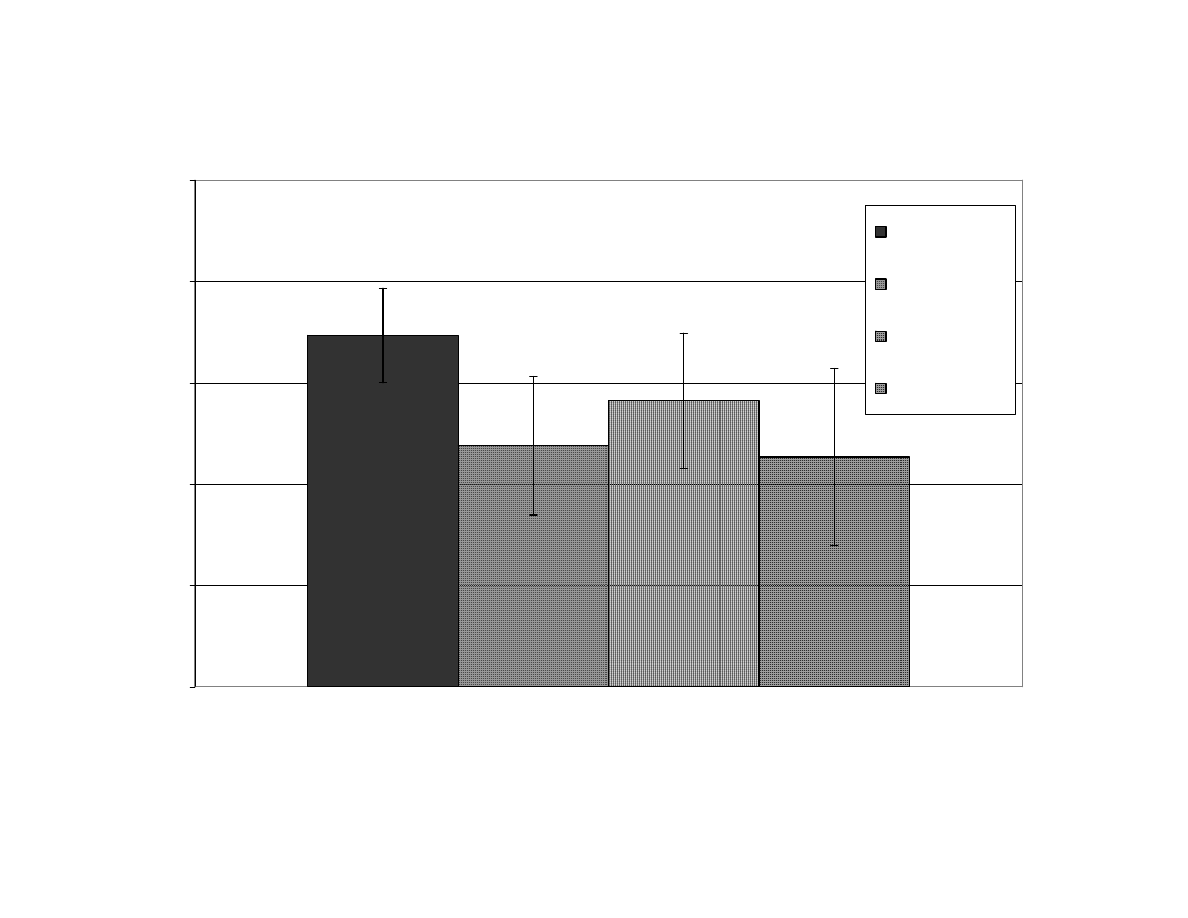

Figure 1

Mean Energy Absorbed by Peanuts Per Treatment for All

Replicates During Microwave Heating for 4, 5, 8, or 11

Minutes

(Set 1) ............................................................................ 111

Figure 2

Internal and Surface Temperatures of Peanuts During

Microwave Blanching for 11 Minutes With and Without Using

Fan

(Set 1) .................................................................................. 112

Figure 3

Internal and Surface Temperatures of Peanuts of 5 and 11%

Initial Moisture Content (MC) During Microwave Blanching for

11 Minutes Without Using a Fan (Set 2)...................................... 113

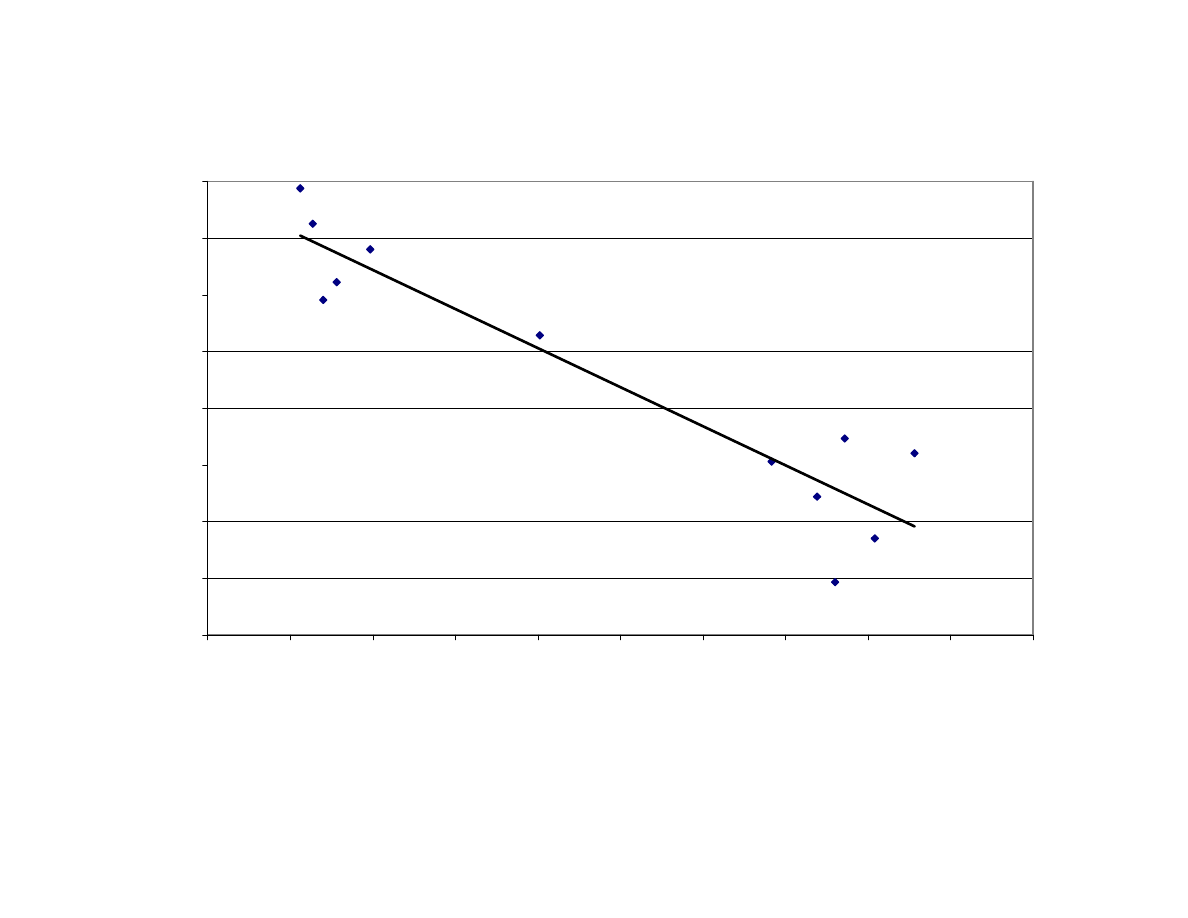

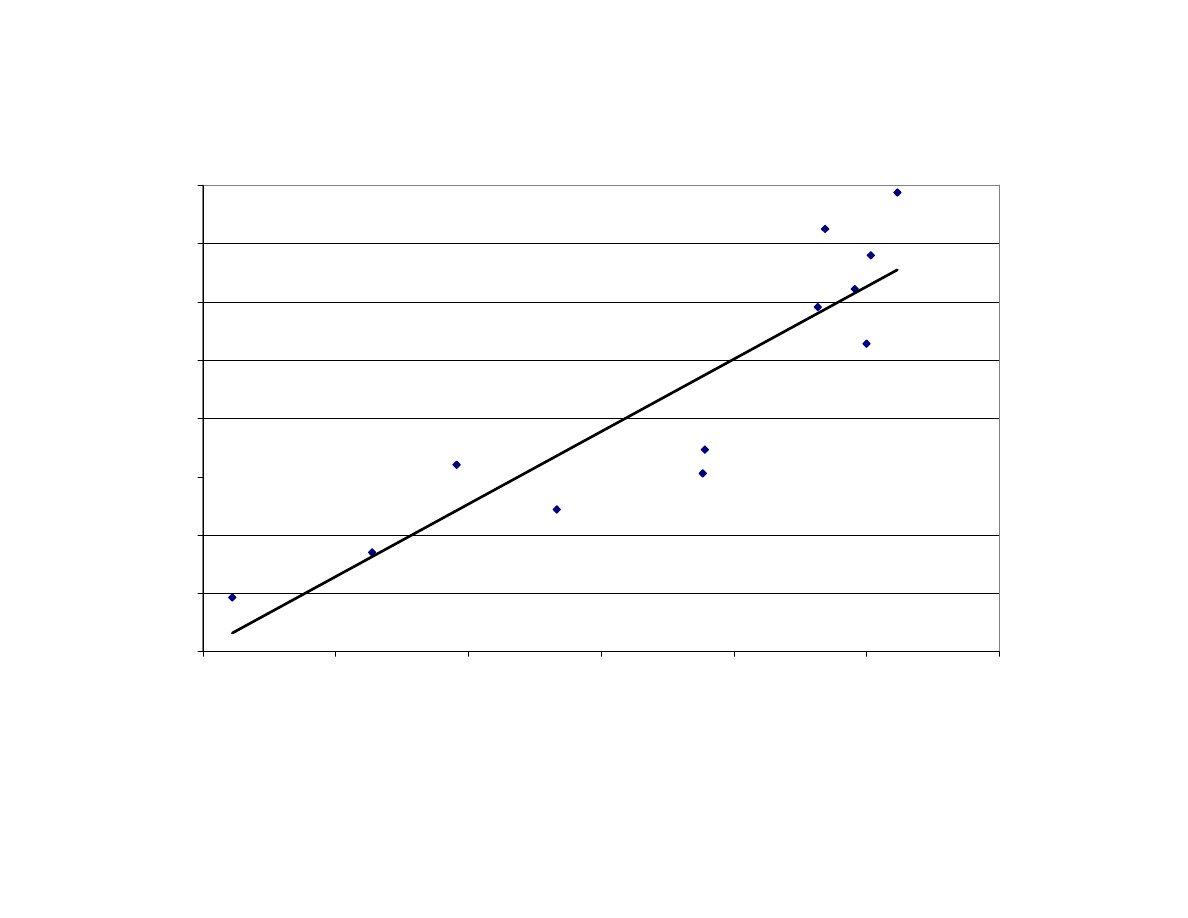

Figure 4

Relationship Between Maximum Internal Temperature and Final

Moisture Content of Peanuts After Microwave Blanching

(Correlation

R

2

= 0.87). F= Fan Used During Blanching,

NF = No Fan Used, MC = Moisture Content............................... 114

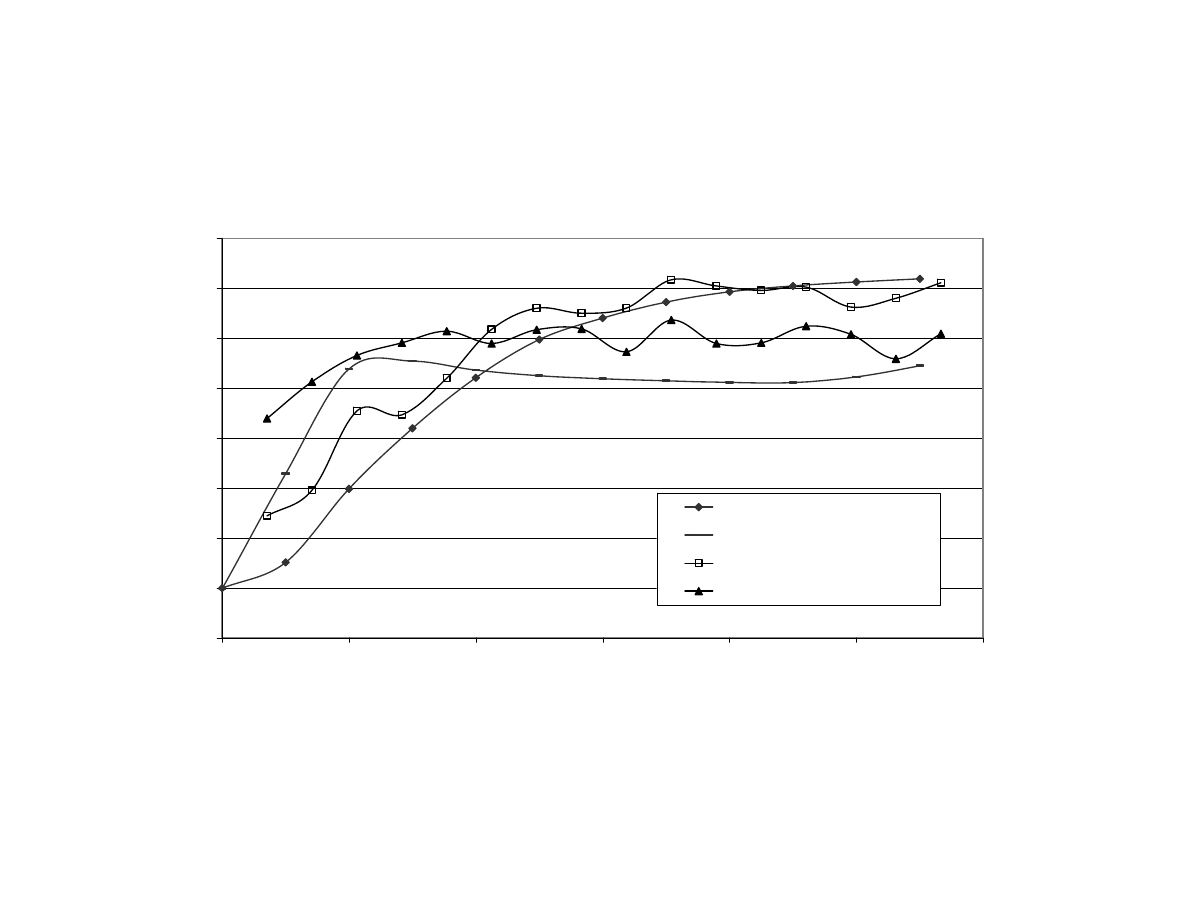

Figure 5

Mean of Blanchability Results Per Treatment for All Replicates

During Microwave Blanching of Peanuts for 4, 5, 8, or 11

Minutes

(Set 1) ............................................................................ 115

Figure 6

Mean of Blanchability Results Per Treatment for All Replicates

During Microwave Blanching of Peanuts for 11 Minutes

Without Using a Fan (Set 2) ........................................................ 116

Figure 7

Relationship Between Maximum Internal Temperature and

Blanchability of Peanuts After Microwave Blanching

(Correlation

R

2

= 0.81). The Average Final Moisture Content

(MC) of Each Treatment is Noted ................................................ 117

1

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

2

Peanuts are a valuable agricultural crop in the United States, specifically in

Virginia, the Carolinas, and in the Southeast and Southwest regions. The annual

production of peanuts in the United States reached 4.2 billion pounds in 2004

(NASS, 2005). Peanuts are valuable nutritionally due to their high protein content

and the amount of unsaturated fats. The most common use of peanuts worldwide is

crushing for oil and meal. The oil is used for cooking and as a salad oil, while the

defatted meal is processed into protein concentrates and isolates. In the United

States, a majority of the domestic peanut crop is used for products such as peanut

butter, and it also serves as a versatile ingredient in confections.

When peanuts are roasted, they obtain a unique flavor which drives product

marketing in the peanut industry. This flavor is the result of genetics, handling,

storage, and processing factors (Sanders et al., 1995). As a result, there is an

interest in the effects of harvesting and processing techniques on peanut flavor

(Singleton and Pattee, 1991; Singleton and Pattee, 1992; Osborn et al., 1996; Baker

et al.

, 2003; Didzbalis et al., 2004).

The processing of peanuts includes several steps from harvesting to final

product. Handling of the peanut crop starts with digging, shaking off soil and debris,

drying the peanuts from 35 - 40% moisture content to 15 - 20%, combining to

separate the pods from the plants, transport to storage facilities, removing the hulls,

and blanching to remove the seed coat from the kernels (Ory et al., 1992). After

blanching, most of the peanuts are roasted for use in peanut butter, confections, or

other snack foods.

3

The processing parameters used during blanching can have significant

impacts on the final product quality. The process of peanut blanching consists of an

application of heat followed by abrasive removal of the seed coat. This step is done

for several reasons. Blanching results in the removal of the seed coat which contains

tannins that contribute off-flavors and off-colors. Blanching is also used to remove

foreign material and dust (St. Angelo et al., 1977). It also reduces enzyme activity

and moisture content, which are factors impacting subsequent quality (Adelsberg

and Sanders, 1997). Furthermore, blanching aids in the electronic color-sorter

removal of damaged or discolored seeds, which are associated with aflatoxin

contamination (Sanders et al., 1999).

Several methods are used for blanching: dry-blanching, spin-blanching,

water-blanching, alkali-blanching, and hydrogen peroxide-blanching. In general, the

most common method in industrial processing is dry-blanching. In this process,

peanuts are placed on conveyor belts and moved through large hot-air ovens in

which the direction of airflow is alternated in successive zones (Adelsberg and

Sanders, 1997). The peanuts are heated in sequential zones from 30 °C to 90 °C,

with a total processing time of approximately 45 minutes. During this time, moisture

is removed from the peanuts, the seed coat is loosened, and after cooling, the seed

coats are mechanically removed (Sanders et al., 1999). Paulsen and Brusewitz

(1976) suggested that the mechanism of blanching is due to differences in thermal

expansion and subsequent contraction of the seed and seed coat, resulting in a

loosening of the seed coat.

4

Microwave processing has been investigated as an alternative to traditional

processing methods due to the speed of operation, energy savings, and efficient

process control (Giese, 1992). Since heating takes place only in the food material

and not in the surrounding medium, microwave processing can reduce energy costs.

Shorter heating times also lead to greater nutrient retention, better quality

characteristics such as texture and flavor, as well as increased production (Giese,

1992). The use of a continuous microwave system for blanching has been proposed

as a means of reducing production time and energy costs during peanut processing.

Previous studies at North Carolina State University have shown promise for the use

of an industrial microwave system. Peanuts were effectively blanched by the

microwave when the peanuts reached temperatures over 85 °C and final moisture

contents of 6% or lower. In a study using a series of individual trays of peanuts

passing through the microwave field, Rausch et al. (2005) examined the potential

use of microwaves for peanut blanching. In the current study, refinement of the

microwave applicator has allowed a solid bed of peanuts to be exposed to

microwave energy in a continuous process, using a processing technique similar to

that of Boldor et al. (2005).

The best blanching efficiencies result from peanuts which are subjected to the

highest temperatures during blanching and lose the most moisture. Moisture

content affects blanchability as well as stability and flavor quality of peanuts

(Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997; Katz, 2002). However, high temperature processing

has been tied to the formation of off-flavors. For example, elevated temperatures are

used during curing, in which the moisture content of the peanuts after digging is

5

reduced from 35-40% moisture to 8-10% to prevent quality losses before further

processing. It has been documented that curing peanuts at temperatures above

35 °C is related to the formation of anaerobic by-products which produce an off-

flavor. Also, with increased curing temperatures above 35 °C, positive attributes

such as roasted peanutty decrease while off-flavors such as fruity/fermented

increase in intensity (Sanders et al., 1990). This decrease in positive flavor attribute

intensity with increase in temperature has also been observed in dry-blanching

(Sanders et al., 1999).

Such changes in the quality and flavor of peanuts have been described

previously using descriptive sensory analysis. Peanuts were first evaluated using a

method called the Critical Laboratory Evaluation of Roasted Peanuts, or CLER

(Holaday, 1971). Later, sensory lexicons for peanuts and peanut products were

constructed by Oupadissakoon and Young (1984) and Syarief et al. (1985). A

standardized lexicon was subsequently developed to address deficiencies in earlier

models such as lack of differentiation of oxidized off-flavors and lack of

sweet/caramel descriptors (Johnsen et al., 1988). The lexicon used in this research

incorporates a ten point scale to rate intensity of flavor attributes using commercially

available products as references (Sanders et al., 1989).

Using descriptive sensory analysis, a processing-related off-flavor has been

noted in peanuts undergoing high-temperature microwave blanching (Katz, 2002).

The chemical cause of this off-flavor is not yet known. In other studies, specific

volatile compounds identified by GC-mass spectrometry have been linked to sensory

attributes in peanuts (Young and Hovis, 1990; Vercellotti et al., 1992). Instrumental

6

techniques can be used to analyze the volatile compounds which affect peanut

flavor, although these compounds are present at very low concentrations and can

interact with other components of the food matrix, leading to difficulties in their

extraction (Reineccius, 2002). A variety of extraction and isolation techniques have

been applied in peanut flavor research, including solvent extraction and high vacuum

distillation (Didzbalis et al., 2004), static headspace (Young and Hovis, 1990), and

dynamic headspace (Crippen et al, 1992). Other off-flavors which have been

documented in peanuts, such as fruity fermented, have been linked to their

causative chemical compounds (Didzbalis et al., 2004). By identifying the

compounds responsible for an off-flavor, the possible causes, such as anaerobic

respiration, lipid oxidation, or enzymatic activity, may be determined and the off-

flavor itself can possibly be prevented.

The use of microwave technology for blanching peanuts can result in a large

reduction in processing time, subsequent cost savings, and better product quality.

The objective of this study was to characterize the impact of different microwave

blanching parameters on the quality and flavor of roasted peanuts, and to identify

the chemical components responsible for the off-flavor caused by high-temperature

microwave blanching. Microwave blanching is an alternative processing method

which holds the promise of better product quality and more efficient process control,

if properly implemented. However, the occurrence of an off-flavor in the final product

may be problematic in the adoption of this method. The identification of the

chemical compounds causing this off-flavor could ultimately aid in the development

of an alternative blanching method for peanuts using microwave technology.

7

REFERENCES

Adelsberg GD, Sanders TH. 1997. Effect of peanut blanching protocols on bed

and seed temperatures, seed moisture, and blanchability. Peanut Science 24:

42-46.

Baker GL, Cornell JA, Gorbet DW, O'Keefe SF, Sims CA, Talcott ST. 2003.

Determination of pyrazine and flavor variations in peanut genotypes during

roasting. J. Food Sci. 68(1): 394-400.

Boldor D, Sanders TH, Swartzel KR, Farkas, BE. 2005. A model for

temperature and moisture distribution during continuous microwave drying.

Journal of Food Process Engineering 28(1): 68-87.

Crippen KL, Vercellotti JR, Lovegren NV, Sanders TH. 1992. Defining roasted

peanut flavor quality. Part 2. Correlation of GC volatiles and sensory flavor

attributes. In: Charalambous G, editor. Food Science and Human Nutrition.

New York: Elsevier Science Publishers. p 211-227.

Didzbalis J, Ritter KA, Trail, AC, Plog FJ. 2004. Identification of fruity/fermented

odorants in high temperature cured roasted peanuts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52:

4828-4833.

Giese J. 1992. Advances in microwave food processing. Food Technology

46(9): 118-123.

Holaday CE. 1971. Report of the peanut quality committee. Journal of

American Peanut Research and Education Association 3: 238-241.

Johnsen PB, Civille GV, Vercellotti JR, Sanders TH, Dus CA. 1988.

Development of a lexicon for the description of peanut flavor. Journal of

Sensory Studies 3: 9-17.

Katz TA. 2002. The effect of microwave energy on roast quality of microwave

blanched peanuts. Master's Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh,

NC.

NASS. 2005. USDA crop production 2004 summary. Washington, DC:

National Agriculture Statistics Service.

Ory RL, Crippen KL, Lovegren NV. 1992. Off-flavors in peanuts and peanut

products. In: Charalambous G, editor. Developments in Food Science v. 29:

Off-Flavors in Foods and Beverages. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier

Science Publishers. p 57-75.

Osborn GS, Young JH, Singleton JA. 1996. Measuring the kinetics of

8

acetaldehyde, ethanol, and ethyl acetate within peanut kernels during high

temperature drying. Transactions of the ASAE 39(3): 1039-1045.

Oupadissakoon C, Young CT. 1984. Modeling of roasted peanut flavor for some

Virginia type peanuts from amino acid and sugar contents. J. Food Sci. 49: 52-

58.

Paulsen MR, Brusewitz GH. 1976. Coefficient of cubical thermal expansion for

Spanish peanut kernels and skins. Transactions of the ASAE 19(3): 592-595,

600.

Rausch TD, Sanders TH, Hendrix KW, Drozd JM. 2005. Effect of microwave

energy on blanchability and shelf life of peanuts. J. Agric. Food Chem.,

submitted.

Reineccius, G. 2002. Instrumental methods of analysis. In: Taylor AJ, editor.

Food Flavor Technology. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. p

210-251.

St. Angelo AJ, Kuck JC, Hensarling TP, Ory RL. 1977. Effects of water and spin

blanching on oxidative stability of peanuts. Journal of Food Processing and

Preservation 1: 249-260.

Sanders TH, Adelsberg GD, Hendrix KW, McMichael Jr. RW. 1999. Effect of

blanching on peanut shelf-life. Peanut Science 26: 8-13.

Sanders TH, Blankenship PD, Vercellotti JR, Crippen KL. 1990. Interaction of

curing temperature and inherent maturity distributions on descriptive flavor of

commercial grade sizes of Florunner peanuts. Peanut Science 17: 85-89.

Sanders TH, Pattee HE, Vercellotti JR, Bett KL. 1995. Advances in peanut flavor

quality. In: Pattee HE, Stalker HT, editors. Advances in Peanut Science.

Stilwater, OK: American Peanut Research and Education Society, Inc. p 528-

553.

Sanders TH, Vercellotti JR, Blankenship PD, Crippen KL, Civille GV. 1989.

Interaction of maturity and curing temperature on descriptive flavor of peanuts.

J. Food Sci. 54(4): 1066-1069.

Singleton JA, Pattee HE. 1991. Peanut moisture/size, relation to freeze damage

and effect of drying temperature on volatiles. J. Food Sci. 56(2): 579-581.

Singleton JA, Pattee HE. 1992. Maturity and storage affect freeze damage in

peanuts. J. Food Sci. 57(6): 1382-1384.

Syarief H, Hamann DD, Giesbrecht FG, Young CT, Monroe RJ. 1985.

9

Interdependency and underlying dimensions of sensory flavor of selected

foods. J. Food Sci. 50: 631-638.

Vercellotti JR, Crippen KL, Lovegren NV, Sanders TH. 1992. Defining roasted

peanut flavor quality. Part 1. Correlation of GC volatiles with roast color as an

estimate of quality. In: Charalambous G, editor. Developments in Food

Science v. 29: Food Science and Human Nutrition. Amsterdam, The

Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers. p 183-206.

10

CHAPTER 2:

LITERATURE REVIEW

11

Composition of Peanuts

The structure of a peanut seed consists of two cotyledons and a germ, which

is enveloped in a thin skin called the testa. The peanut heart contains bitter material

and as a result is often removed during processing, while the testa is removed

during blanching. The testa contains mainly protein, fiber and carbohydrates, as

well as tannins which give the skin a bitter flavor (Hoffpauir, 1953).

Within each year, the composition and quality of the peanut crop changes due

to climatic variations as well as different harvesting and handling techniques (Pattee

et al.

, 1990). Peanut seeds consist of approximately 50% fat and 30% protein

(Hoffpauir, 1953). The main fatty acids found in peanuts include palmitic, oleic, and

linoleic acids. Up to 6% of peanut oil consists of long chain saturated fatty acids

such as arachidic acid (20:0), behenic acid (22:0), lignoceric acid (24:0), oleic acid

(18:1), and linoleic acid --18:2 (Chung et al., 1993). A large percentage of peanut oil

consists of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are a substrate for oxidation by

lipoxygenase (Ory et al., 1992, St. Angelo, 1996). Ahmed and Young (1982)

indicated that the oleic/linoleic acid ratios in the peanut varied with cultivar, growing

location, maturity, as well as temperatures during the last few weeks of harvest.

This oleic/linoleic acid ratio has been positively correlated to oil stability.

The protein in peanuts includes albumins, and two globulins, arachin and

conarachin. The total protein has a high digestibility coefficient and has significant

amounts of 10 essential amino acids (Hoffpauir, 1953). The specific amino acid

content of peanuts varies depending on the type of peanut, cultivar, location, and

12

maturity, because the concentrations of free amino acids decrease as the peanut

matures (Basha and Young, 1996; Ahmed and Young, 1982).

While in general, plants possess naturally occurring antioxidants such as

superoxide dismutase, tocopherols, carotenes, and ascorbic acid, oilseeds are

specifically identified with peroxidases and catalase. Peroxidase and catalase

function by aiding the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, and

thereby help eliminate this precursor to free radical species (Sanders et al., 1993).

Peanut oil also contains antioxidants such as α, γ, and δ tocopherols (Hoffpauir,

1953).

The other components in peanuts include carbohydrates such as starch,

sucrose, pectins, and cellulose (Hoffpauir, 1953). Sucrose is the main carbohydrate

in peanuts. In processing, there are slight losses in sucrose during roasting,

although glucose and fructose decrease to a greater extent. Peanuts also contain

high levels of potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium, although the amounts

change with cultivar (Ahmed and Young, 1982).

Overview of Peanut Production

In the early 1990’s, China, the U.S., and Argentina were the most important

peanut exporting countries, and the primary importers were the European

Community, Japan, and Canada. However, imports to the European Community

have dropped due to a policy shift encouraging the use of rapeseed or sunflower

seed oil instead of importing peanut oil. Most of the increases in peanut production

since the 1970’s have occurred in Asian countries such as India, China, Indonesia

13

and Burma. The peanut prices in the Rotterdam market have been recognized as

the world reference price, and this has been tied to monthly estimates of peanut

production in America’s Southeast (Carley and Fletcher, 1995).

The United States produces approximately 10% of the world’s peanuts

(Sanders et al., 1993). Each year in the U.S., 700,000 hectares of peanuts are

harvested, with each hectare producing approximately 2.8 tons (Smith et al., 1995).

The U.S. peanut industry relies on an extensive price support and production quota

system (Carley and Fletcher, 1995). Peanuts are grown in the Southeast (Alabama,

Florida, Georgia), Southwest (Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico), as well as in

Virginia and North Carolina (Smith et al., 1995). There are four major market types

of peanuts in the U.S.: runner, virginia, valencia, and spanish (Sanders et al., 1993).

The most important use of world peanut production remains the crushing of

peanuts for oil and meal (Carley and Fletcher, 1995). The oil is used for cooking

and as a salad oil, while the defatted meal is processed into high protein

concentrates and isolates. In comparison, a large percentage of peanuts in the

United States is used for peanut butter and in confections. Alternative uses for

peanut protein have been explored for applications such as fermented milk and

yogurt systems, soup bases, nonfermented cheese analogs, meat product

ingredients, breads and snack products, and the replacement of casein in extended

milk products (McWatters and Cherry, 1982).

Harvesting

Harvesting includes the removal of peanuts from the ground, and separating

the nuts from soil and vines. Further steps include drying the peanuts from 35-40%

14

moisture content to 15-20%, combining to separate the pods from the plants,

transport to storage facilities, removing the hulls, and blanching to remove the testa

from the seeds (Ory et al., 1992). Peanuts are separated from accompanying

materials during harvest by vibrating, perforated screens or by a belt screen which

uses multiple parallel belts rotating continuously around sheaves (Smith et al.,

1995). There is a potential for off-flavor development if the peanuts are damaged

during handling, because lipoxygenase, which is usually separated from the oil by

cell compartmentalization, can then oxidize the oil and create off-flavors (Ory et al.,

1992).

The harvest is set at a time to maximize the number of mature pods.

However, immature pods are usually present in every lot, especially during

abnormally cool or hot harvesting weather, and are difficult to separate from mature

pods. The percent of immature pods in a lot depends on the peanut variety, weather

conditions during growth and development, as well as harvest date (Osborn et al.,

2001).

Curing

Curing is the process of reducing the moisture content of peanuts to a level

maintaining safety and quality (Young et al., 1982). Curing is needed before

combining because when the peanuts contain 35-40% moisture, they are soft and

susceptible to damage by the combine (Ory et al., 1992). Curing dries the peanuts

either completely, or to 20-25% wet basis (w.b.) moisture in the field, with a final

artificial drying in wagons to 8-10%. If the peanuts are not dried to less than 10%

15

(w.b.) within 3 days, large quality losses result from biological activity (Young et al.,

1982). Fungus growth due to high moisture content can lead to high free fatty acid

concentrations, caused by fungal lipase activity (Sanders et al., 1993).

In wagon drying, a balance is needed in air flow, air humidity, and drying time

so that the bottom layers of peanuts are not over-dried, but the top layer of peanuts

will not spoil before drying is completed (Young et al., 1982). Deep-bed drying of

peanuts can be envisioned as the drying of successive single layers. For each

layer, the temperature and humidity of the air is changed as it passes through the

peanuts (Troeger, 1982).

The rate of moisture removal during peanut drying is proportional to the

difference in vapor pressure of the peanut interior and that of the surrounding air. As

the moisture content of the peanut decreases, the time needed to remove a certain

amount of moisture increases because the vapor pressure difference is not as great.

When the humidity of the air becomes equal to that of the peanuts, drying ceases

(Troeger, 1982).

The heat used for drying also promotes reactions of the concentrated peanut

components (Sanders et al., 1993). The step of curing in peanut processing initiates

catabolic processes, such as degradation of carotenoids. Enzymatic and

nonenzymatic reactions also occur, which have been only minimally investigated

(Sanders et al., 1995).

Troeger (1982) conducted drying simulations to determine effects of varying

parameters on drying time and energy use. Simulations showed that drying peanuts

with a higher airflow rate (4.72 m

3

/s versus 3.05 m

3

/s) decreased drying time about

16

6%, while energy use increased 45% as a result. Too low of airflow resulted in a

greater difference in moisture content in peanuts between the top and bottom layers

of the dryer, and the initial moisture content of the peanuts also had a significant

effect on the variation between peanut layers. Allowing the drying air to rise 15 °C

reduced drying time by 36%, while energy consumption increased 14%. However,

this higher temperature rise also reduced the relative humidity to an unacceptable

range to maintain product quality (Troeger, 1982).

Delwiche et al. (1986) examined the use of microwaves for peanut curing in

comparison to traditional methods. Because peanuts must be dried at temperatures

lower than 35 °C and humidity greater than 60% to maintain quality, drying times

exceed 30 hours for peanuts which are dried in standard wagons. Due to faster

processing times, the energy requirement for microwave vacuum drying was found

to be less than for traditionally dried peanuts. However, high moisture shelling

followed by microwave drying led to elevated levels of Aspergillus flavus growth on

the seeds. In addition, as microwave process rate and temperatures increased,

seed germination potential decreased and the seeds were more susceptible to

abrasion and impact. During these experiments, Delwiche et al. (1986) adjusted

microwave power levels depending on the initial temperature and moisture content

of the peanuts, using the following equation:

Q = γ

dry

c

dry

(T

f

-T

i

) + γ

dry

c

w

[mc

i

/ (1-mc

i

)] (T

f

-T

i

) + h

lg

γ

dry

[(mc

i

/ 1-mc

i

) – (mc

f

/1-mc

f

)]

Where:

Q = Energy per unit volume (kJ/m

3

)

γ

dry

=

Bulk density of dry seeds (kg/m

3

)

17

c

dry

= Specific heat of dry seeds (1.880 kJ / (kg °C))

T

f

and T

i

= Final and initial temperature of seeds (°C)

mc

i

and mc

f

= Initial and final seed moisture content (wb)

c

w

= Specific heat of water (4.187 kJ/(kg °C))

h

lg

= Heat of vaporization of water (2.418 x 104 kJ/kg at 35 °C)

The curing of peanuts at temperatures above 35 °C has been associated with

anaerobic by-products which produce an off-flavor (Whitaker et al., 1974). An

increase in the concentration of alcohols, aldehydes and esters, especially ethanol,

ethyl acetate, and acetaldehyde, is thought to be tied to this change in respiration

from aerobic to anaerobic (Pattee et al., 1990). At the high rates of respiration

occurring at high curing temperatures, oxygen cannot diffuse into the seed at a

sufficient rate, causing anaerobic respiration to take place. This was shown in an

experiment by Whitaker et al. (1974), in which a significant depression in oxygen

partial pressure was found inside peanuts cured at 52 °C compared to those cured

at 24 °C.

With increasing curing temperature, positive attributes such as roasted

peanutty decreased and fruity fermented intensity increased (Sanders et al., 1990).

Volatiles such as mercaptans, carbon dioxide, and carbonyls also increased during

roasting after high temperature curing (Young, 1973). Drying temperatures above

35 °C are avoided to prevent off-flavor formation (Troeger, 1982).

18

Effect of Peanut Immaturity

Peanut quality is affected by the degree of maturity at harvest, which reflects

the extent of interaction of genetic, physiological and biochemical processes

(Sanders et al., 1995). Maturity in peanuts is achieved more quickly at higher soil

temperatures, while irrigation practices and harvest date also affect peanut maturity

class (Sanders, 1989). Peanuts are a botanically indeterminate plant, which flower

and initiate peanut development over an extended period of time. Although in

general, a larger seed is related to greater degree of maturity, in commercial peanut

lots of any specific size, a range of maturities is found. In fact, not all mature

peanuts are large and not all immature peanuts are small (Sanders et al., 1995).

Quality characteristics such as roast color, flavor, and storability are variable within

peanut lots of the same commercial size, and this may be the result of a distribution

of maturities (Sanders, 1989).

Differences in maturity will affect the carbohydrate and amino acid

composition, as well as the moisture content of the peanuts. As the peanuts mature,

the moisture content decreases, although a range of moisture contents are present

at harvest of 20-70%. As a result of this and the related biochemical and physical

development of the peanuts during processing and shelf life, quality differences can

occur (Sanders et al., 1993). For example, during maturation and processing steps

such as curing, the precursors for Maillard reaction reach optimum levels (Sanders

et al.

, 1995). Also, as peanuts mature, there is an increase in total oil,

triacylglycerol, and the oleic to linoleic acid ratio. At the same time, free fatty acids,

mono- and diacylglycerols, and polar lipids decrease in concentration. Although

19

there is no direct correlation published between amount of oil and shelf life, a

significant correlation has been shown between oil content with maturity, which itself

is related to flavor and shelf life potential (Sanders et al., 1993).

The compositional and structural differences in the proteins and sugars of

immature peanuts suggest that these components will react differently to processes

in manufacture (Sanders, 1989). Vercellotti et al. (1994) formulated a biochemical

model of carbohydrate turnover during peanut curing. Immature peanuts had more

low molecular weight reducing substances and oligosaccharides than the mature

peanuts at all stages during curing. In addition, during maturation, many enzyme-

catalyzed reactions occur by way of proteases, lipases, glycosidases, and

phosphatases to make flavor intermediates. This dependence on timing may

change the flavor compounds present in the final product (Sanders et al., 1993). As

a result of these compositional differences, the type of response to conditions such

as high temperature curing or freeze damage will also vary based on maturity

(Sanders et al., 1995).

The degree of maturity will also affect color development of the peanuts

during roasting. Immature peanuts brown at a lower temperature and more rapidly

than mature peanuts. Consequently, close control of roasting is needed to reach the

optimum Hunter L value of 50 ± 1 (Ory et al., 1992).

Immature peanuts also vary in their flavor profiles. In general, immature

peanuts are more susceptible to off-flavor formation than mature peanuts (Osborn et

al.

, 2001), and at a given temperature, immature peanut seeds have a higher level of

off-flavor production than mature seeds (Pattee et al., 1965). Immature peanuts

20

have significantly lower intensities of positive notes such as roasted peanutty flavor

after roasting, and a higher intensity of off-flavors such as painty, cardboardy, and

fruity-fermented (Sanders, 1989; Pattee et al., 1990; McNeill and Sanders, 1998). In

addition, sour and bitter notes were higher in immature peanuts, and increased in

intensity with increasing curing temperature (Sanders et al., 1989). Sanders et al.

(1989, 1989b) determined that the flavor potential of any peanut lot is related to its

percentage of immature peanuts and the methods of curing and handling applied.

Storage

After curing, peanuts can be stored before further processing, and the storage

conditions will affect the final product quality. When peanuts are stored after harvest,

storage time and seed size will affect carbohydrate and amino acid composition,

volatiles, and roast seed blanchability (Pattee et al., 1982). Raw peanuts are subject

to loss in quality during storage due to insect, bird, and rodent infestation, microbial

activity, mechanical damage, physical changes such as weight loss or shrinkage,

biochemical changes in flavor, and absorption of odors (Smith et al., 1995). Farmers

stock peanuts, or peanuts which have only been picked and threshed, are stored

anywhere from one week to as long as 10 months (Smith et al., 1995).

Decreasing the moisture and temperature in a storage facility will decrease

quality loss during storage. Generally, the best storage conditions for farmer stock

peanuts are approximately 10 °C and 7.5% moisture content wet basis (Smith et al.,

1995). However, if the storage conditions drop below 7% moisture or 7 °C, high

losses in milling quality result when the peanuts are shelled (Smith et al., 1995).

21

Peanuts are commonly stored in flat-storage warehouses, including the

conventional form, the conventional with doghouse, and the muscogee with

doghouse type warehouses. Large crops of peanuts can also be stored in circular

tanks or silos such as those used in the grain industry. For adequate air circulation

through the peanut mass, there is a minimum distance which should be maintained

between the peanut mass and the warehouse roof at the eaves. Peanuts are loaded

into a warehouse using a hydraulic lift or hoist to empty peanuts from the drying

trailer into a dump pit. A bucket elevator then transports the peanuts to a horizontal

belt conveyor with a mobile tripper which distributes the peanuts in the storage

space below. Farmer stock peanuts can be damaged when handled by a bucket

elevator at belt speeds greater than 61 m/min, by crushing during loading and

unloading, or by the drop from the tripper to the warehouse floor (Smith et al., 1995).

After storage, peanuts are cleaned, shelled and undergo gravity or density

separation. Damaged and split seeds are removed during processing using

bichromatic machines, cameras, or electronic sorting machines (Smith et al., 1995).

Blanching

The next steps in peanut processing include blanching and roasting. The

process of peanut blanching consists of an application of heat followed by abrasive

removal of the seed coat. This step is done for several reasons. Blanching results in

the removal of the seed coat which contains tannins that contribute off-flavors and

off-colors (St. Angelo et al., 1977). Blanching also reduces enzyme activity and

moisture content, which are factors impacting subsequent quality (Adelsberg and

22

Sanders, 1997). For example, in a study of lipoxygenase activity in blanched

peanuts, the enzyme activity significantly decreased with increasing heating time

and temperature. Furthermore, blanching aids in the removal of damaged or

discolored seeds, which are associated with aflatoxin contamination (Sanders et al.,

1999). After the seed coats are removed during blanching, electronic color sorters

are used to detect the damaged seed, effectively reducing aflatoxin in contaminated

lots (Whitaker, 1997).

Several methods are used for blanching: spin-blanching, water-blanching,

dry-blanching, alkali-blanching, and hydrogen peroxide blanching. In spin blanching,

peanuts are passed through a skin cutter, dried to lower the moisture to 5%, and

then the skins are loosened and removed using a spin-blancher. Water-blanched

peanut seeds are slit and treated with 86 °C water for 90 seconds, dried to bring the

moisture to 5%, and the skins are then removed mechanically (St. Angelo et al.,

1977).

In general, the most common method in industrial processing is dry

blanching. To dry the peanuts, they are placed on conveyor belts and moved

through large hot-air ovens in which the direction of air flow is alternated in

successive zones (Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997). The peanuts are treated to

increasing temperatures in subsequent zones from 30 °C to 90 °C, with a total time

of approximately 45 minutes. During this time, moisture is removed from the

peanuts and the seed coat is loosened, and after cooling, the seed coats are

mechanically removed (Sanders et al., 1999). Specific information on industrial

blanching protocols is hard to obtain due to proprietary issues. However, industrial

23

blanching has been imitated using a Proctor and Schwartzingle chamber. This is a

flame-heated oven with airflow control, which can be alternated at timed intervals

while gradually increasing oven temperatures (Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997).

It has been suggested that the mechanism of blanching is due to differences

in thermal expansion and subsequent contraction of the seed and seed coat,

resulting in a loosening of the seed coat. In an experiment by Paulsen and

Brusewitz (1976), the coefficient of cubical thermal expansion of seeds (50 – 60.5 x

10

-5

/ °C) was significantly different than that for peanut skins (26.5 – 55 x 10

-5

/ °C),

and as drying continued, the coefficient for cubical thermal expansion for skins

decreased due to moisture loss. This trend led to an increased stress and rupturing

of the skins as the seeds expanded at an increased rate (Paulsen and Brusewitz,

1976).

The efficiency of blanching has been correlated to the genetic makeup of the

plant, with the selection of certain parents resulting in improved blanchability

(Cruickshank et al., 2003). However, processing parameters during blanching have

a significant impact as well. Adelsberg and Sanders (1997) studied the effects of

varying parameters on peanut temperature distributions and blanching efficiency.

The magnitude of peanut bed temperature variation during blanching was related to

final oven set point temperature and to dwell time at each temperature setting. The

temperature variation of individual seeds was up to 5 °C between the seed surface

and a set distance (3 mm) inside the seed. This difference was thought to be due to

the high oil content in peanuts, which leads to low thermal conductivity values

(Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997). Individual seed variation in temperature may affect

24

degree of enzyme inactivation, moisture loss, blanchability, and storage stability

(Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997). In addition, an increase in the range of exit surface

temperatures of the peanuts was correlated to non-uniform drying, which causes a

large variation in single seed moisture distribution (Vilayannur, 1998; Rausch, 2002).

The effects of moisture content and time-temperature parameters were also

evaluated in terms of blanching efficiency. In general, with increasing temperatures

and increasing moisture loss, blanching becomes more efficient (Paulsen and

Brusewitz, 1976; Katz, 2002). Blanchability was correlated with the final oven set

point temperature and negatively correlated with the final moisture content when

above 3.8% (Adelsberg and Sanders, 1997). The specific parameters giving the best

blanching efficiencies are still being debated. Adelsberg and Sanders (1997)

reported that reduction of peanut moisture content from 5.5 to < 4 % using

temperatures of 87.7 °C for 45 and 60 minutes and 98 °C for 30, 45, and 60 minutes

resulted in blanchability above 75%. However, Katz (2002) found that blanching

treatments in which peanut temperatures exceeded 96.7 °C and moisture content

was lower than 6.0%, showed blanching efficiencies greater than 84.5%.

The perception in the peanut industry is that blanching reduces shelf life

(Sanders et al., 1999). For example, blanching has been tied to an increase in lipid

oxidation in raw peanuts (Ory et al., 1992). Pattee and Singleton (1971) suggested

that blanching may increase production of off-flavors in peanuts during storage

compared to raw peanuts, because although methanol and acetaldehyde

concentrations decreased during blanching, pentane increased over storage as a

result of enzyme reactions or lipid oxidation. However, in a study by Sanders et al.

25

(1999), no detrimental effects of blanching on oxidative stability were found.

Although blanched and nonblanched peanuts were different in peroxide value and

OSI value, all values were within acceptable ranges, indicating no meaningful shelf

life differences over storage (Sanders et al., 1999).

The quality and oxidative stability of the peanuts may depend on temperature

and time parameters used during blanching. In a study by Rausch (2002), peanuts

were stable to lipid oxidation after microwave blanching, as determined by peroxide

value, oxidative stability index, hexanal and pentanal concentrations, when treated

with specific power and exposure time conditions. However, peanut batches which

reached surface temperatures above 100 °C declined rapidly in quality over the 28-

week storage period (Rausch, 2002). Blanching temperature has also been

correlated with other flavor effects. Positive attributes such as roasted peanutty had

a weak negative relationship with final blanching temperature in peanuts blanched to

high temperatures (98.9 °C) and for longer times (Sanders et al., 1999).

It has also been reported that different types of blanching appear to have

varying effects on shelf life stability. Unblanched peanuts were the least and water-

blanched were the most stable of roasted peanuts (St. Angelo et al., 1977).

However, it has been reported that in unroasted peanuts, water-blanched peanuts

have the shortest shelf life, while spin-blanched peanuts and unblanched raw

peanuts were more stable. It has been suggested that water-blanched peanuts gain

a glaze of protein and lipids washed from the insides of slits made during blanching.

This glaze oxidizes and shortens shelf life of the peanuts as compared to spin-

blanched nuts and unblanched nuts which are not roasted (St. Angelo et al., 1978).

26

Additional detrimental effects occur in peanuts which are blanched to reduce

aflatoxin levels. In this case, blanching may result in a more rapid deterioration of

already inferior quality peanuts (Sanders et al., 1999).

Moisture content has been shown to affect the stability and flavor quality of

the peanuts (Pattee et al., 1982; Sanders, 1998; Katz, 2002). The best blanching

efficiencies result from peanuts which are subjected to the highest temperatures

during blanching and lose the most moisture. In addition, a uniform moisture

distribution in the peanut batch after blanching allows for a more uniform roast and

overall better quality of the final product (Rausch, 2002). Moisture content also has

an effect on formation of flavor precursors during storage before final processing.

Peanuts which were stored at a higher moisture content (8.7-9.2% versus 6%) had

more hydrolysis of sugars and proteins, as well as a greater deterioration of quality

(Pattee et al., 1982). Furthermore, higher moisture peanuts had lower roasted

peanutty intensity and pyrazine concentrations, and had higher intensities of sensory

notes related to lipid oxidation, such as painty and cardboard (Abegaz et al., 2004).

Roasting

After blanching, many of the peanuts will be roasted for use in peanut butter,

confections, or other snack foods. During processing in a continuous roaster, the

product is metered onto the roaster bed which is an oscillating pan or a fixed-pitch

belt. Hot air is generated in the upper chamber by using either electricity or fuel

sources. This heated air is then distributed from above or below to make a fluidized

bed. Mixing is induced in the peanut bed by bubbling air from below or jet shearing

27

when the air is distributed from above (Cammarn et al., 1990). A recirculation fan is

used to remove exhaust gas. Peanuts are roasted at an internal temperature of 265

to 300 °F, and the moisture content is lowered from 4-6% moisture to 1% moisture

(Hoffpauir, 1953). As a result, reactions such as the Maillard reaction occur which

are key to the formation of typical roasted peanut flavor and color.

The predominant reactions occurring during roasting include the Maillard

reaction, Strecker degradation, and sugar caramelization. The Maillard reaction

involves a reducing sugar, such as glucose from the hydrolysis of sucrose, and an

amino acid under specific conditions of pH, water activity, and temperature. The

reaction intermediate loses a water molecule to form glycosylamine. After the

subsequent Amadori rearrangement, an amino keto sugar is formed, which can lead

to further decomposition products (Cammarn et al., 1990).

The Strecker degradation involves the decomposition of glucose to a dione,

which reacts with an amino acid and loses water molecule, and eventually

polymerizes to form pyrazines or other products. At high temperatures,

caramelization of sugars can also occur. Caramelization involves the dehydration

and decomposition of sugar molecules to form a variety of products such as

aldehydes, ketones, sugar fragments, and unsaturated rings. These unsaturated

molecules can absorb light to make brown pigments (Cammarn et al., 1990).

In addition to protein and carbohydrate reactions, after the peanuts are

roasted, the oil is more susceptible to oxidation. This occurs despite the fact that

lipoxygenase and polyphenoloxidase have been denatured, because of the

presence of nonenzymatic catalysts (Ory et al., 1992).

28

Microwave Processing

Microwave processing has been explored as an alternative to traditional

processing methods, due to its speed of operation, energy savings and efficient

process control. Because heating takes place only in the food material and not the

surrounding medium, microwave processing can reduce energy costs. Shorter

heating times lead to greater nutrient retention, better quality characteristics such as

texture and flavor, as well as increased production (Giese, 1992).

The development of the continuous conveyor microwave oven in the 1960’s

greatly aided the industrial use of microwaves for food processing, due to a more

uniform distribution of microwave energy. Conveyor systems include resonant-

cavity systems and waveguide systems. A conveyor passes through a microwave

field in a resonant cavity system, while the product conveyor in a waveguide system

runs through a slot perpendicular to the waveguide (Giese, 1992).

There are not many large-scale industrial microwave applications currently,

with less than 500 worldwide (Giese, 1992). The exceptions include the use of

microwaves for tempering of frozen foods, precooking of poultry and pork products,

and drying of pasta and onions. Tempering using microwaves can be completed in

minutes, compared to the 2-5 day period needed for traditional thawing techniques,

and there is less microbial growth, little weight loss, increased juice and flavor

retention, and less space required. Microwave cooking has been increasingly

successful for precooking bacon, meat patties, and poultry, due to increased yields,

shorter preparation times, and increased product quality (Mudgett, 1989). The

cooking of bacon by microwave processing also yields high quality rendered fat as a

29

by-product (Giese, 1992). Drying is conducted with combination of conventional

heating and microwaves for pasta, which utilizes less energy and less case

hardening (Mudgett, 1989). In addition, many industrial processes combine

conventional and microwave heating to raise the surface temperature and improve

browning and crisping, to accelerate drying rates, or to reduce microbial counts

(Mudgett, 1989).

Other applications are still being explored for microwave processing.

Microwaves are commonly used for drying cookies and biscuits, but are not used for

commercial bread baking despite energy savings reported. Microwave sterilization

is currently conducted at 110-130 °C under pressure, although problems are still

being addressed such as development of proper packaging materials, excessive

surface heating, and cooling after sterilization (Giese, 1992). Microwave processes

with potential include vacuum and freeze drying, fat rendering, roasting, and

pasteurization (Mudgett, 1989). In the drying of mushrooms, combined microwave

and hot air drying allowed a shorter heat treatment; as a result, the mushrooms had

a higher aroma retention and preservation of the volatile ratios which are significant

to mushroom flavor (DiCesare et al., 1992). Microwaves have also been

investigated as an alternative method to blanch vegetables (Sevirini et al., 2003),

and this method has shown advantages in vitamin C and carotenoid retention in

microwave-blanched carrots, spinach and bell peppers (Ramesh et al., 2002)

In peanut processing, microwave vacuum drying has been researched as a

method for curing (Delwiche, 1986). Microwaves have also been investigated as an

alternative method to roast peanuts (Megahed, 2001). However, Megahed (2001)

30

concluded that in comparison to conventional roasting methods, the use of

microwave technology resulted in the increase of conjugated dienes and trienes,

epoxy and hydroperoxide formation, oil darkening, and the general formation of

undesirable and possibly harmful oxidation products and pigments. Likewise,

Yoshida et al. (2005) found that following microwave roasting, the lipid profile of

peanuts changed unfavorably, as free fatty acids and diacylglycerols increased

significantly, although the unsaturated fatty acids which were located in the second

position on the triacylglycerol were protected from oxidation.

Mechanisms of Action

Microwaves are electromagnetic waves which are between radio and infrared

wavelengths on the electromagnetic spectrum. High frequency energy is emitted by

the magnetron, and includes poles of positive and negative charge changing

direction billions of times each second. As a result, water, salts, and other polar

molecules line up according to charge in the microwave electric field (Giese, 1992).

In orientation polarization, dipoles such as water attempt to follow the rapidly

changing electrical field, and energy is lost due to random thermal motion of water;

this type of polarization is highly temperature dependent (Ryynanen, 1995).

Hydrated ions in a food also try to move in the direction of the changing electrical

field, and transfer energy as a result (Ryynanen, 1995).

Microwave energy heats foods instantaneously, unlike conventional heating

methods, which transfer thermal energy from product surfaces inward 10-20 times

more slowly (Mudgett, 1989). Heating using microwaves is based on the ability of

31

the material to absorb electromagnetic radiation and convert it into heat. The

magnetic field interactions in food are negligible, due to only trace amounts of

magnetic materials present such as nickel, cobalt, or iron. As a result, only the

electric field has an effect (Ryynanen, 1995; Mudgett, 1989). The overall heating

rate in microwave processing is dependent on dielectric constant and dielectric loss,

specific heat, and density. Microwave energy inactivates microorganisms by thermal

denaturation of proteins and nucleic acids, just like conventional thermal processing,

and depends on the same time/temperature relationships (Mudgett, 1989).

The transmission properties of the electromagnetic waves are related to the

dielectric and thermal properties of the food, and also determine the distribution of

energy (Ryynanen, 1995). Packaging also has an effect, as microwaves are

transmitted through ceramic, plastics, paper, and glass, but metals such as

aluminum foil reflect microwaves (Giese, 1992). Energy reflected from the surface

causes standing wave patterns of nodes and antinodes, which result in uneven

energy distribution at product surfaces and hot and cold spots within the product

(Mudgett, 1989).

The microwave penetration depth and overall heating rate will be determined

by the specific heat, density, surface to volume ratio, thermal conductivity,

evaporative cooling of the food, as well as the shape of the food. The sphere and

cylinder are the best shapes for microwave heating, because microwaves can

penetrate the food from all sides. In general, foods which have a high surface-to-

volume ratio will cook more rapidly (Giese, 1992). Products heated in a continuous

microwave with slab geometry, such as trays of peanuts in microwave blanching,

32

experience more heating on the surface than in the middle of the product, which

exposes a limitation of infrared thermometry for process measurements (Rausch,

2002)

The moisture content and temperature of the product affect rates of internal

conduction and surface convection. These are determined by thermal diffusivity,

and are also affected by heat loss from surface cooling by moisture evaporation

(Mudgett, 1989). The electric field inside the load is affected by the dielectric

properties, geometry of the load, and the oven configuration (Ryynanen, 1995).

For practical purposes, penetration depth is calculated, which is the depth

below a plane surface at which the power density of the electromagnetic wave has

decayed by 1/e (~37%) of its surface value (Ryynanen, 1995). Foods which contain

more moisture and salt content will exhibit less penetration depth by the

microwaves, and subsequently have less uniform heating (Mudgett, 1989; Giese,

1992).

Dielectric Properties

The permittivity describes the ability of a material to absorb, transmit, and

reflect electromagnetic energy. Permittivity has two parts: the real permittivity or

dielectric constant, ε', and the imaginary component or dielectric loss, ε".

Permittivity is described by the equation (Ryynanen, 1995):

ε = ε' - j ε"

Where:

ε = Relative complex permittivity

33

ε' = Relative real permittivity (dielectric constant)

ε" = Relative dielectric loss factor

j = Imaginary unit

The dielectric constant relates the ability of the material to absorb energy,

while the dielectric loss factor is related to various mechanisms of energy

dissipation. The dielectric loss is always positive and usually smaller than the

dielectric constant (Ryynanen, 1995). The dielectric constant decreases with

increasing temperature, while temperature has a variable effect on dielectric loss,

depending on the product. A large dielectric loss will translate into shorter heating

times (Giese, 1992).

Dielectric properties are most commonly measured in one of three ways: by

open-ended coaxial probe, transmission line, or by resonant cavity. In all of these

methods, a microwave signal is generated at a certain frequency and is directed at

or through the material being tested. By observing the changes in signal caused by

the material, the dielectric properties are calculated (Engelder and Buffler, 1991).

In general, food products have a loss factor of 25 or less, and exhibit a

penetration depth of 0.6-1.0 cm. However, dielectric properties change with the

composition of the food and with frequency. Both ε' and ε" are affected by the

moisture content, concentration of salt, frequency of electromagnetic field, and the

temperature. Dielectric properties are also affected by the physical state of the food.

For example, as the temperature of frozen goods rises through thawing, both ε' and

34

ε" increase greatly, but then decrease after thawing with rising temperature

(Ryynanen, 1995).

Water is the main component of most foods, and as a result, its

concentration will also determine its dielectric properties. Dielectric properties have

been of interest in agricultural products for use in determining moisture content. In

agricultural products, the dielectric properties vary widely among different kinds of

grain, crop and weed seed, although in general both ε' and ε" are greater in samples

of higher bulk densities and higher equilibrium moisture content. For example, the

dielectric properties at microwave frequencies have been used to nondestructively

estimate the moisture content of shelled peanuts (Trabelsi and Nelson, 2006).

The salt in foods binds the free water molecules, and acts as a conductor in

an electromagnetic field. As a result, salt depresses the permittivity and elevates the

dielectric loss factor when compared to pure water, because it adds charge carriers

to the matrix. However, while ε' increases with water content, low or moderate salt

content does not affect this value much (Ryynanen, 1995). For salty foods at lower

frequencies, ε' decreases sharply with a rise in temperature. In pure water, ε'

increases slightly with decreasing frequency. The degree of influence of water and

salt content in a food depends on the amount to which they are bound or restricted

in movement by other food components (Ryynanen, 1995). Likewise, the effect of

colloidal organic solids is to depress the permittivity (dielectric constant) by excluding

more dielectrically active materials such as water from the volume. The exclusion of

water by carbohydrates affects dielectric properties, as carbohydrates do not show

much dipole polarization at microwave frequencies (Ryynanen, 1995). For fats and

35

oils, both ε' and ε" are low and relatively independent of frequency and temperature

(Ryynanen, 1995).

The dielectric properties of shelled and unshelled peanuts have been

measured in bulk samples (Trabelsi and Nelson, 2004). Shelled peanuts have