The effect of interorganizational

trust on make-or-cooperate decisions:

Disentangling opportunism-dependent

and opportunism-independent effects

of trust

Werner H Hoffmann, Kerstin Neumann, Gerhard Speckbacher

WU Vienna U. of Economics and Business, Department of Strategy and Innovation, Vienna, Austria

Correspondence:

Kerstin Neumann, WU Vienna U. of Economics and Business, Department of Strategy and Innovation, Nordbergstr 15,

Vienna, 1090, Austria.

Tel:

þ 431313364204;

Fax:

þ 43131336763;

E-mail: kerstin.neumann@wu.ac.at

Abstract

This paper seeks to analyze the effects of interorganizational trust on the decision to

vertically integrate a strategically important activity (‘make’) or sign a long-term agree-

ment with an external exchange partner to perform such an activity in collaboration

(‘cooperate’). On the basis of the literature available on interorganizational trust in

economics and sociology, we aim at theoretically and empirically disentangling

opportunism-based and opportunism-independent effects of trust on governance

choices. We develop a set of hypotheses on the moderating and direct roles of trust,

which are tested using a sample of integration/collaboration decisions made by Austrian

and German automotive suppliers. The results confirm both an opportunism-mitigating

effect of trust that lowers the transaction costs of a collaborative exchange and an

opportunism-independent effect that increases the transaction value of a collaborative

exchange and also encompasses non-economic motives for collaboration.

European Management Review (2010) 7, 101–115. doi:10.1057/emr.2010.8;

published online 27 May 2010

Keywords:

interorganizational trust; governance decisions; strategic alliances; cooperation; vertical

integration

Introduction

T

he question of whether a specific transaction should be

managed within the confines of a particular firm or in

collaboration with other firms is of key strategic

importance (Madhok and Tallman, 1998; Barney, 1999;

Leiblein and Miller, 2003). Furthermore, given the dramatic

increase in the number of collaborative, interorganizational

relationships seen in recent years (Osborn and Hagedoorn,

1997; Harbison and Pekar, 1998), such decisions are also of

high practical relevance.

Previous research indicates that the governance choices

made by firms are affected by the level of preexisting inter-

organizational trust between exchange

1

partners (Chiles

and McMackin, 1996; Zaheer and Harris, 2006; Gulati and

Nickerson, 2008). The standard theory put forward in the

analysis of decisions on firm boundaries is transaction cost

economics (TCE). According to standard TCE reasoning,

the impact of trust on governance choice is driven by the

threat of opportunistic behavior. Defining trust as ‘a type of

expectation that alleviates the fear that one’s exchange

partner will act opportunistically’ (Bradach and Eccles,

1989: 104), it has been argued that a higher level of trust

between exchange partners implies that fewer resources will

have to be spent on costly safeguards against opportunism

(see e.g. Lorenz, 1988; Barney and Hansen, 1994; Cummings

and Bromiley, 1996; Bigley and Pearce, 1998; Gulati and

Nickerson, 2008). Hence, trust ‘can substitute for hierarchical

contracts in many exchanges and serves as an alternative

European Management Review (2010) 7, 101–115

&

2010 EURAM Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved 1740-4754/10

palgrave-journals.com/emr/

control mechanism’ (Gulati, 1995: 93). Since the threat of

opportunistic behavior is a main driver favoring hierarch-

ical governance, a higher level of trust between exchange

partners results in a lower need for hierarchical governance.

This makes collaborative interorganizational exchanges

more attractive with collaboration substituting hierarchy

(Chiles and McMackin, 1996; Zaheer and Harris, 2006;

Gulati and Nickerson, 2008).

However, it has also been argued that TCE theories on

firm boundaries overemphasize the danger of opportunistic

behavior and the role of trust in averting negative outcomes

of opportunistic behavior while ignoring the relevance of

factors other than transaction costs (e.g. Zajac and Olsen,

1993; Conner and Prahalad, 1996; Ghoshal and Moran,

1996; Madhok and Tallman, 1998; Lindenberg, 2000). In

particular, existing literature on strategic alliances high-

lights the importance of trust as the ‘catalyst’ and ‘glue’

between transaction partners and an influencing factor in

governance choices (e.g. Ring and Van de Ven, 1992; Ring,

1996; Lane and Bachmann, 2000; Sydow, 2000; Bachmann

and Zaheer, 2006). Within collaborative exchange relations,

interorganizational trust can make communication and

coordination more effective, lead to deeper and broader

levels of cooperation and enhance information and knowl-

edge sharing routines (see e.g. Uzzi, 1997; Rousseau et al.,

1998; Mo¨llering, 2006).

Obviously, these lines of reasoning employ a broader

definition of interorganizational trust that extends beyond

an expectation that an exchange partner will not engage in

opportunistic behavior. In this paper we will also employ

a broad concept of trust which encompasses both – i.e.,

opportunism-dependent

and

opportunism-independent

explanations of the role of trust.

Using this broad concept of trust, we build on the literature

on strategic alliances and integrate existing research on the

role of trust within strategic alliances into the literature on

corporate boundary choices – i.e., choices between alliances

and vertical integration. We argue that preexisting inter-

organizational trust within collaborative relationships (alli-

ances) between firms (1) can substitute at least some of the

merits of ‘belonging to the same firm’ (e.g. mechanisms for

identification, coordination, communication and knowledge

sharing), (2) can lead to additional relational rents and, (3)

may function as a social mechanism that drives cooperation

independently of cost–benefit calculations. Hence, interorga-

nizational trust makes interfirm collaboration more likely

and leads to collaboration substituting hierarchy. While this

line of reasoning again leads to the prediction of a negative

effect of preexisting trust on the decision to integrate an

activity, it also complements the TCE view, since it proposes a

role of interorganizational trust even in cases where the threat

of opportunism is low and significant exchange hazards are

absent. In such a situation, TCE would not expect trust to

affect either governance costs or the governance mode (e.g.

Gulati and Nickerson, 2008: 692).

On the basis of previous research on interorganizational

trust in economics and sociology, our paper aims to

theoretically and empirically disentangle opportunism-

based and opportunism-independent effects of trust on

decisions between vertical integration and interfirm colla-

boration. In particular, we analyze whether the impact of

interorganizational trust on such decisions is conditional

on the threat of opportunistic behavior and whether trust

has an important impact even in cases where opportunism

does not play a significant role.

The role of trust in governance choices: an overview

Evidence from various disciplines strongly supports

the inclusion of trust as a critical element in economic

transactions (see e.g. Ring and Van de Ven, 1992; Mayer

et al., 1995; Ring, 1996). As far as collaborative exchanges

are concerned, it has been shown that interorganizational

trust impacts organizational structure (Gulati and Singh,

1998), contract design (Poppo and Zenger, 2002) as well as

transaction costs and performance outcomes (Aulakh et al.,

1996; Carson et al., 2003; Dyer and Chu, 2003; Gulati and

Nickerson, 2008).

The multidisciplinary nature and multitude of different

perspectives, levels and facets behind trust research make

agreement on a universally accepted definition of trust

difficult. However, building on a cross-disciplinary review

of scholarly writing, Rousseau et al. (1998: 395) conclude

that there are some ‘critical components’ common to the

notions of trust found in different disciplines. They suggest

the following ‘generally agreeable’ broad definition of trust:

‘Trust is a psychological state comprising the intention to

accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the

intentions or behavior of another’. There is a broad

consensus that – although trust is clearly a sociological

phenomenon that primarily emerges among individuals – it

can also be established between organizations if ‘the

positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of

another [organization]’ are shared by a dominant coalition

of the individuals in both organizations engaged in the

collaborative transaction (Nooteboom, 1996; Lane and

Bachmann, 2000; Zaheer and Harris, 2006).

The level of trust between the focal firm and its

(potential) exchange partner prior to the transaction

(preexisting trust, ex-ante trust) is relevant for analyzing

the effect of interorganizational trust on governance choice.

Ex-ante trust arises from (1) prior exchange experience, (2)

the general reputation of the (potential) exchange partner,

and (3) the broader institutional environment (e.g.

Bromiley and Cummings, 1995; Gulati, 1995; Bachmann,

2001; Bachmann and Zaheer, 2006).

Our study does not focus on how trust emerged and

which factors played what role in this process. Instead, we

focus on how the level of preexisting interorganizational

trust influences governance decisions. Our concept en-

compasses different aspects of trust (in particular calcula-

tive and non-calculative aspects), which correspond to

different sources and antecedents. Of course, from a

dynamic perspective it would also be interesting to analyze

how trust between exchange partners emerges over time

(see e.g. Gulati (1995) and Goerzen (2007) who point to the

importance of repeated interaction between exchange

partners to build up trust) and how this level of trust co-

evolves with governance decisions (e.g. Puranam and

Vanneste, 2009). However, an analysis of this kind lies

beyond the scope of our study.

In the following theory sections, we will build on the

above general definitions and illustrate how different

interpretations of interorganizational trust from various

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

102

theoretical perspectives depend on the underlying beha-

vioral assumptions and considered forms of vulnerability.

The role of trust from a TCE view

TCE is the standard theory put forward in the analysis of

decisions on firm boundaries. The concept of transaction

costs goes back to Coase (1937). To use this concept to

explain firm boundaries, the exact nature and sources of the

costs involved must first be specified, whereby two main

specification traditions prevail (see e.g. Langlois and

Robertson, 1989: 362).

The first line of research points to technological

indivisibilities and their resulting contracting and measure-

ment costs (Alchian and Demsetz, 1972; Barzel, 1982;

Cheung, 1983; Demsetz, 1988), while the second stresses the

importance of incomplete contracts and asset specificity

(Williamson, 1975, 1985). Both approaches work on the

assumption that actors might behave opportunistically and

predict a positive influence of such possible opportunistic

behavior on vertical integration.

Alchian and Demsetz (1972) argue that technological

indivisibilities in team-based production make it difficult to

link the rewards for cooperating team members to their

productivity. These difficulties are caused by the inter-

dependent resources of the transacting partners and result

in contracting costs and costs for monitoring partner

performance. An imperfect link between rewards and

performance may result in shirking or costly disputes

regarding the distribution of generated rents among the

cooperating partners. Internalizing a transaction may avoid

measurement and contracting costs, although the costs of

monitoring and measurement problems still also hinder the

performance of hierarchical transactions (Barzel, 1982;

Cheung, 1983; Demsetz, 1988; Masten et al., 1991). In

addition to a possible reduction in contracting and

measurement costs, internalizing a transaction significantly

reduces the problem of rent appropriation. However, even

if a transaction is internalized, disputes on rent distribution

can still occur between the actual business unit performing

the transaction and other business units (particularly if

these are organized as separate profit centers). But, since

the owners of the firm ultimately have the right to

appropriate all rents generated in all its business units,

the distribution of rents among different business units

becomes simply a matter of internal accounting. In

contrast, if different firms are involved, their owners will

have to negotiate for the generated rents, thus according

greater relevance to the issue of measuring the performance

of the individual transaction partners. Consequently, this

theory emphasizes the difficulties in evaluating the

performance of transaction partners (the so-called mea-

surement difficulties) as a behavioral uncertainty that can

favor vertical integration.

The second stream of TCE research – focusing on asset-

specificity – has clearly been the dominant approach in the

study of vertical integration. In essence, this approach

analyzes the effects of contractual incompleteness when

resources are transaction-specific (Williamson, 1975, 1985,

1991; Klein et al., 1978). Since drafting complete contracts,

which specify each party’s rights and obligations in an exact

and enforceable manner, can be costly (or even impossible),

this opens the door for ex-post bargaining among the

contracting parties. Providers of transaction-specific assets

are locked into the exchange relationship, since these assets

lose much of their value outside that particular relation-

ship. This can lead to costly renegotiations and – more

importantly – an ex-ante underinvestment in value enhan-

cing specific assets if the contracting parties suspect they

are not receiving their ‘fair share’ of the rents generated in

the course of the exchange relationship (the so-called hold-

up problem).

The hold-up problem makes more complex (and thus

more costly) governance forms (market

- hybrid -

hierarchy) advantageous, since they help to avoid the costs

that stem from opportunistic behavior on the part of

transaction partners. From a TCE perspective, activities

that are vertically linked with high transaction-specific

investments should be integrated when the risk of hold-up

is high. Conversely, activities with minimal specific

investments should be disintegrated. Using vertical alli-

ances, even activities with medium-scale transaction-

specific investments can be outsourced, particularly if

appropriate control and monitoring mechanisms are in

place to reduce the risk of opportunistic behavior on the

part of the transaction partner. The cornerstone of this line

of TCE reasoning is the behavioral uncertainty caused by

specific investments made by at least one of the transaction

partners.

TCE is built on the assumption of opportunistic behavior

and highlights two forms of vulnerability induced by such

behavior, namely (1) the inability to monitor and assess an

exchange partner’s performance, and (2) a lock-in condi-

tion caused by transaction-specific investments (see e.g.

Wathne and Heide, 2000: 42). Typically, in economics

literature in general and in TCE literature in particular,

trust is interpreted as the expectation that an exchange

partner will not (or at least only to a restricted extent)

engage in opportunistic behavior, i.e. will not take max-

imum advantage of arising opportunities and changing

conditions at the expense of the other exchange partner

(see e.g. Barney and Hansen, 1994: 176; also Zand, 1972;

Bradach and Eccles, 1998; Ring and Van de Ven, 1992;

Frank, 1993; Chiles and McMackin, 1996; Nooteboom, 1996).

As Williamson (1979: 234) notes, TCE does not assume

that all actors are ‘opportunistic in identical degree’. There

may be actors who engage only in simple self-interest

seeking (without guile) and others who engage in self-

interest seeking with guile, i.e. ‘lying, stealing, cheating, and

calculated efforts to mislead, distort, disguise, obfuscate,

or otherwise confuse’ (Williamson, 1985: 47). Since it is

difficult to actually distinguish between the less and the

more opportunistic, and since ‘even among the less

opportunistic most have their price’ (Williamson, 1985:

47), according to TCE the transaction partners basically

have to be prepared for the worst case.

Given the above general definition, we contend that –

from a TCE perspective – trust can be interpreted as a

positive expectation regarding the degree of opportunistic

behavior. In other words, the estimated probability that the

exchange partner will lie, steal, cheat, etc. is relatively low.

Nonetheless, the exchange partners are aware that – even in

trustful exchange relationships – there can be a ‘level of

temptation’ in which opportunistic behavior emerges to

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

103

some degree. Therefore, trust in this sense does not mean

there is no need at all for safeguards, monitoring and

control. In situations involving high specific investments

and where high performance measurement difficulties

make it easy to cheat, there is more room for opportunistic

behavior and a higher incentive for such opportu-

nistic behavior. Nonetheless, the expected level of oppor-

tunistic behavior remains lower in trusting exchange

relationships, despite the level of specificity and measure-

ment difficulties. As a consequence, fewer monitoring and

control mechanisms are required in a trusting exchange

relationship for all levels of asset specificity and perfor-

mance measurement difficulties, generally resulting in

lower transaction costs and, hence, less need for vertical

integration. The level of required monitoring and control

mechanisms, however, does increase with the degree of

asset specificity and performance measurement difficulties

for all levels of trust, but a high level of trust weakens the

positive influence of these transaction characteristics on

vertical integration (Lorenz, 1988; Barney and Hansen,

1994; Cummings and Bromiley, 1996; Dyer, 1997; Bigley

and Pearce, 1998; Das and Teng, 1998; Das and Teng, 2001).

Obviously, such a notion of trust is, of course, calculative.

Trust refers to a calculation of the optimal level of

monitoring and control mechanisms needed for a particular

transaction with a particular exchange partner.

With respect to the choice of governance modes, this

implies a moderating effect of trust. According to TCE, both

forms of vulnerability drive vertical integration. When the

level of interorganizational trust is low and opportunism

prevails, asset specificity and measurement difficulties both

induce a need for complex and costly monitoring and

control mechanisms. Substantial monitoring and control

costs can be avoided if the transaction partners are part of

the same firm, i.e. if the transaction is vertically integrated.

However, if the expectations of the level of opportunistic

behavior are positive in the above sense – that is if trust

prevails – fewer resources will have to be spent on

monitoring and control mechanisms. This implies that

the positive effect of performance measurement difficulties

and transaction-specific investments on vertical integration

is weaker when the level of trust is higher. In other words,

the effect of performance measurement difficulties and

asset specificity on the decision to vertically integrate a

transaction is moderated (i.e. attenuated) by the existing

level of trust between the exchange partners.

The moderating effect of trust on the impact of asset

specificity on governance choice has been argued theo-

retically in detail and clarified by Chiles and McMackin

(1996). Also the empirical findings by Artz and Brush

(2000) and Joshi and Stump (1999) indicate that the negative

impact of transaction-specific investments on collabora-

tive exchange is weakened by a high level of interorgani-

zational trust because trust reduces the perceived amount of

behavioral uncertainty (danger of hold-up). Thus, we

hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1:

Trust attenuates the positive relationship

between transaction-specific investments and integration.

If the performance of an exchange partner is difficult

to measure and assess, it is easier to cheat and there is

more room for opportunistic behavior. Hence, according

to standard TCE reasoning, performance measurement

difficulties have a positive effect on monitoring and

control costs as well as on bargaining costs on rent

distribution between the independent exchange partners.

According to TCE, such costs can be (partly) avoided

using hierarchical governance, making integration more

attractive. If trust prevails, i.e. if the expected degree

of opportunistic behavior on the part of the exchange

partner is lower, the need to monitor and control said

exchange partner’s performance is lower and costly

disputes on rent distribution are less likely to occur.

Moreover, pre-existing trust between the exchange

partners can make the performance measurement pro-

cess easier and less costly. Thus, the positive direct effect

of performance measurement difficulties on the decision

to vertically integrate a transaction is weaker when the

existing level of trust between the exchange partners is

high. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2:

Trust attenuates the positive relationship

between performance measurement difficulties and

integration.

The role of trust beyond mitigating opportunism: transaction

value and sociological views

As Mo¨llering (2006: 24) notes, the opportunism-mitigating

role of trust represents a fairly restricted view of trust that

results from the fact that economic research on trust is

‘conservative’ in the sense that it focuses on opportunism

only. Here, the role of trust is to avert the negative

outcomes of opportunistic behavior, while other genuinely

positive effects of trust – such as more effective commu-

nication and coordination – are typically neglected (see also

Lindenberg, 2000). This TCE focus on possible negative

outcomes and neglect of factors that drive transaction value

have been widely criticized (e.g. Zajac and Olsen, 1993;

Dyer, 1997; Geyskens et al., 2006).

In the following section, we draw on insights regarding

the nature and effects of trust that go beyond its role in

averting the transaction costs stemming from opportunistic

behavior. While such concepts are compatible with the

above general definition of trust, the behavioral assump-

tions here differ significantly from those made in TCE and

also employ a broader concept of vulnerability. Vulner-

ability is created not only through specific investments and

performance measurement difficulties in the face of a

danger of opportunistic behavior, but also more generally

through the dependence on the exchange partner inherent

in every economic and social exchange relationship

(Sabel, 1993).

In contrast to the notion of trust found in TCE, this

suggests a significant impact of interorganizational trust on

the decision to collaborate which is independent of the

assumption of opportunistic behavior. In particular, inter-

organizational trust is expected to have a positive impact on

the decision to collaborate even for such transactions whose

characteristics do not indicate a high degree of exchange

hazards. Both economic and social motives can play a role

and are often interrelated.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

104

Trust and transaction value

We will first focus on economic rationales for the

importance of trust in collaborative exchange that go

beyond TCE reasoning. Here we build on existing literature

on strategic alliances, which highlights the importance

of trust as the ‘catalyst’ and ‘glue’ between transaction

partners and as an influencing factor in governance choices

(e.g. Dyer and Singh, 1998; Bachmann and Zaheer, 2006;

Zaheer and Harris, 2006). From an economic perspective,

trusting an exchange partner and establishing a collabo-

rative exchange aimed at gaining economic benefits is a

quasi-rational choice. In addition to its capacity to reduce

transaction costs, trust can give ‘access to economic gains

from cooperation’ (Rousseau et al., 1998: 396) and, hence,

increase transaction value.

Such gains can arise from the (trustful) sharing of new

technology among producers and suppliers, the disclosure

and transfer of valuable information (Dyer and Chu, 2003)

and the joint learning and knowledge sharing enabled by a

common language and shared routines (Szulanski et al.,

2004). The better the collaborating partners know each

other and the more openly they share their knowledge,

the more (new) opportunities to utilize synergies will be

identified and exploited. Indeed, activities can be organized

in a trustful exchange relationship in ways that approx-

imate their intra-firm counterparts while avoiding the costs

of hierarchical governance. In fact, interorganizational trust

positively influences all four determinants of relational

rents identified by Dyer and Singh (1998: 663): (1) Trust

supports the development and refinement of interorganiza-

tional problem-solving routines (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998).

(2) Trust increases the efficiency and effectiveness of the

governance of the cooperative relationship because it leads

to fewer conflicts and helps resolve emerging disputes, an

aspect that also has a positive impact on the length of

the collaboration (Ganesan, 1994). (3) Trust improves the

degree of compatibility in the organizational systems, pro-

cesses and cultures of exchange partners, thereby also

increasing the organizational complementarity of the

cooperating firms. According to Dyer and Singh (1998), a

high degree of organizational complementarity and a sound

cultural fit increase the economic gains of partnering. (4)

Trust has a positive influence on the scope and longevity of

the partnership and thus supports the development of

co-specialized assets by both exchange partners over time,

with a positive impact on the relational rents obtained from

the collaboration.

Sociological views of trust

However, the economic view on trust as a quasi-rational

choice has long been criticized for its undersocialized view

of human behavior. Since transactions are frequently

embedded in social relationships, the individualistic view

of human behavior found in economic theory limits the

scope and validity of an economic analysis of transactions

(see e.g. Granovetter, 1985). The sociological view of person-

hood is based on ‘the idea that persons are constituted, or

can constitute themselves, only in society’ (Sabel, 1993:

109). Such a view might well be expected to provide insights

into the importance of trust that go beyond the explana-

tions found in economic theory. With respect to the

concept of trust, the sociological view employs a model of

human action that differs from the behavioral assumptions

of economic theory (quasi-rational choice). Trust in this

sense means the non-calculative reliance on the goodwill

and integrity of others (Baier, 1986; Ring, 1996). From a

sociological perspective, trust is affect-based in the sense

that it is ‘grounded in reciprocated interpersonal care and

concern’ (Ring, 1996: 156; also Baier, 1986; McAllister,

1995). It refers to shared expectations, shared under-

standings, shared values, loyalty, a common language and a

common view of the world (see e.g. Sabel, 1993; Uzzi, 1997;

Rousseau et al., 1998; Nooteboom, 2000; Mo¨llering, 2006).

This ‘socialized’ notion of trust is also important for

collaborative interfirm exchanges since they are also

socially embedded and, as discussed above, interpersonal

care and concern and common understandings and feelings

can be expanded to an interorganizational level and become

a collective orientation for the individuals engaged in

the collaborative exchange (Nooteboom, 1996; Lane and

Bachmann, 2000). Social norms of reciprocity and indebt-

edness and the corresponding social (institutional) pro-

cesses and pressures may drive firms to opt for a colla-

borative arrangement – independent of economic consid-

erations.

While calculative (economic) and non-calculative (socio-

logical) explanations of the direct impact of interorgani-

zational trust on governance choices differ, all three lines

of theorizing – TCE, transaction value-based theories

and sociological views – nonetheless assume a positive

direct effect of trust between a firm and its potential

exchange partner on said firm’s decision to collaborate

instead of performing a transaction in-house. The higher

the level of pre-existing interorganizational trust bet-

ween the firm and its potential external exchange partner,

the greater the probability the firm will decide to

collaborate.

Hypothesis 3:

A high level of trust between a firm and its

potential external exchange partners has a negative effect

on integration.

However, the three lines of reasoning on the role of trust

differ in how they explain the effect of trust on governance

choice. According to TCE, the role of trust depends on its

capacity to reduce the likelihood of opportunistic behavior

by an exchange partner. Hence, trust moderates the impact

of the drivers of opportunistic behavior on integration. As

proposed by TCE, there are two such drivers, asset

specificity and performance measurement difficulties. For

transactions, however, where the threat of opportunism is

low and significant exchange hazards do not exist (i.e. when

neither asset specificity nor performance measurement

difficulties play a major role), TCE would expect no effect of

trust on governance costs and hence no effect on the make-

or-cooperate decision (e.g. Gulati and Nickerson, 2008:

692). As long as the threat of opportunistic behavior is low,

lack of trust does not drive a firm to integrate an activity it

would otherwise have carried out in collaboration with an

external exchange partner. Instead, TCE limits the oppor-

tunism-based effect of trust on the make-or-cooperate

choice to transactions with a substantial threat of

opportunistic behavior.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

105

Should a significant influence of trust on make-or-

cooperate decisions also be observed for transactions

associated with a low to medium threat of opportunistic

behavior, this effect cannot be explained using a TCE-based

argumentation but instead indicates an opportunism-

independent influence of trust on the choice between

integration and collaboration. The economic and non-

economic roles of trust discussed above imply that –

independent of the assumption of opportunistic behavior

– firms are less likely to choose a hierarchical governance

mode over a collaborative arrangement if there is a

potential exchange partner available who can be trusted.

A high level of interorganizational trust enables the

cooperating firms to enjoy many of the advantages typically

found in hierarchical governance (effective learning,

coordination and identification) and, at the same time,

more fully exploit the value creation potential (relational

rents) presented by a collaborative exchange. Moreover,

social norms, bonds and obligations may also drive firms to

establish a collaborative exchange even when the economic

gains from this mode of governing a given activity are

insignificant compared to fully integrating this activity.

Thus, we anticipate a significant – albeit weaker –

positive impact of interorganizational trust on collabora-

tion even for transactions associated with a relatively low

risk of opportunistic behavior and we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4:

A high level of trust between a firm and its

potential external exchange partners has a negative effect

on integration, even if the threat of opportunistic

behavior is low.

Table 1 summarizes the different aspects of how

interorganizational trust influences make-or-cooperate

decisions of firms. From an economic perspective, choosing

between distinctive governance modes is a quasi-rational

choice. Interorganizational trust may reduce the transac-

tion costs and increase the negotiation efficiencies

(Mesquita and Brush, 2008) of collaborative exchange in

situations in which exchange characteristics open up room

for opportunistic behavior. But trust may also enhance the

transaction value and the production efficiencies (Mesquita

and Brush, 2008) of a collaborative exchange independent

of the risk of opportunism. From a sociological perspective,

governance decisions are not viewed as quasi-rational

choices, but as decisions that are socially embedded and

constrained. These social (institutional) forces may drive

firms to collaborate even when there are no positive

economic gains over vertical integration.

Methods and data

Data collection

The data for this study were obtained through a survey of

integration/cooperation decisions made by automotive

suppliers in Austria and Southern Germany. The auto-

motive supply industry provides an excellent example for

the decomposition and reconfiguration of the value chain

by using interorganizational relationships. Automotive

suppliers are positioned at different steps in the value

chain of the automotive industry ranging from first to lower

tier suppliers. Therefore, decisions whether an activity

should be undertaken by the supplier itself or jointly

performed in a long-term cooperative relationship are both

common and of high strategic significance.

To determine the survey questions, we carefully reviewed

the relevant academic literature. We then conducted an

extensive pre-test with company General Managers to verify

the clarity of the structured questionnaire. Following the

pre-test, we modified the wording of some items slightly

(those that were confusing or lacked consistency in

interpretation), a process that further strengthened content

validity. Since data collection was to be carried out using a

web-based questionnaire, we also used the pre-test to verify

that the system functioned properly and was easy to use.

To ensure a sufficient respondent involvement and

response rate, we used a two-step data collection procedure.

In a first step that was conducted in autumn 2005, we

contacted the CEOs of 926 Austrian and Southern German

Table 1 Different views on the effects of interorganizational trust on make-or-cooperate decisions

Transaction cost view in economics

Transaction value view in economics

Sociological view

K

Boundary decisions as a quasi-

rational choice

K

Trust mitigates behavioral

uncertainties stemming from the

danger of opportunistic behavior

in a collaborative exchange

K

Trust lowers transaction costs

and increases negotiation

efficiencies in a collaborative

exchange

K

Indirect effect of trust

(moderating the direct effect of

exchange characteristics on

governance choice) and direct

positive effect of trust on

collaboration

K

Boundary decisions as a quasi-

rational choice

K

Trust increases economic gains

from a collaborative exchange

(independent of the danger of

opportunism)

K

Trust increases transaction value

and production efficiencies in a

collaborative exchange

K

Direct positive effect of trust on

collaboration

K

Boundary decisions are

constrained by social

(institutional) processes and

pressures

K

Trust between economic actors

stemming from their social

(institutional) embeddedness

influences their behavior –

independent of economic

considerations (social norms,

bonds and obligations)

K

Direct positive effect of trust on

collaboration

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

106

automotive suppliers. We asked if they had had to make a

decision in the last 2 years to either perform a strategically

important transaction in-house (‘make’) or sign a long-

term agreement with an independent partner to perform

such a transaction in collaboration (‘cooperate’). Those

who answered ‘yes’ were then asked to tell us which of the

two options they had chosen (‘make’ or ‘cooperate’). We

also asked whether they would be willing to take part in a

study to identify the factors influencing this type of

decision and provide us with the name of an internal

contact person with the most knowledge of this transaction

(most knowledgeable informant; Kumar et al., 1993). The

CEOs of 459 firms responded that such a decision had had

to be made in their firms in the last 2 years and provided

the relevant contact details. To collect the relevant infor-

mation on transaction characteristics, transaction context

and the (potential) collaboration partner, we designed two

versions of a structured questionnaire, one for transactions

in which the decision-makers had opted for a collaborative

arrangement and another in which vertical integration

(‘make’) had been chosen. It was pointed out to the

decision-makers that all responses had to refer to the time

the decision was made. Those who had opted to integrate

the transaction were asked to refer in their answers to

questions on the potential collaboration partner to their

most preferred partner of any potential partners. In a

second step which was conducted in summer 2006, we sent

a personalized e-mail to the respective contact persons

(decision-makers) in the 459 firms. The e-mail included an

explanation of the aim of the study, a link to the online

questionnaire and a personalized log in code (these codes

also enabled us to monitor the responding firms). We

followed this up with telephone reminders and a second

e-mail and finally received a total of 151 usable ques-

tionnaires. We believe that the data collection procedure

used provides credibility to our data as it makes sure that

the questionnaire was answered by the ‘right’ person, i.e.

the most knowledgeable informant with the authority to

take the underlying make-or-cooperate decision.

In line with Armstrong and Overton (1977) – and also

recently applied, for example, by Krishnan et al. (2006) and

Poppo and Zenger (2002) – we examined the likelihood of

non-response bias by comparing early to late respondents

using study variables. The assumption of the analysis is that

late respondents are representative of non-respondents. Our

analysis indicated that no significant mean differences exis-

ted between early and late respondents. Furthermore, we had

information on firm characteristics such as sales volume and

employee numbers for every firm in our initial sample (926).

As already suggested by, for example, Celly and Frazier

(1996), we compared such data from non-respondents with

data from respondents and again found no significant

differences. These analyses indicate that we had no serious

problem regarding non-response bias in our sample.

Measures

The questionnaire items for all independent variables,

unless stated otherwise, were measured using a 7-point

scale (where ‘1’ represented ‘disagree’ and ‘7’ represented

‘strongly agree’). For a detailed account of the use of

independent variables in this study, see Appendix Table A1.

Dependent variable

The objective of our study was to analyze the effects of

different transaction characteristics on decisions to either

vertically integrate a transaction or cooperate in a long-

term contractual relationship with a transaction partner.

Thus, the dependent variable is dichotomous with expres-

sions of integration (1) and cooperation (0). We refer to

‘integration (1)’ as a decision to perform a transaction

in-house (acquisitions excluded), while ‘cooperation (0)’

characterizes a transaction performed under a long-term

contractual agreement with an independent transaction

partner (i.e. non-equity alliances).

Trust

In our study, the level of interorganizational trust prior to

the transaction was measured using a 4-item scale based on

Zaheer and Venkatraman (1995) and Zaheer et al. (1998).

Our notion of trust includes not only calculative but also

non-calculative elements in the sense of ‘noncalculative

reliance in the moral integrity, or goodwill, of others’

(Ring, 1996: 156), with both these elements typically being

interrelated.

We measure interorganizational trust using the assess-

ment of the relevant decision-maker (the most knowledge-

able informant) of the most preferred (potential) collabo-

ration partner for the transaction in question. In our study

interorganizational trust is an expectation (expressed by the

relevant decision-maker) of the intentions or behavior of

the most preferred (potential) collaboration partner. This

expectation is the result of possible previous exchanges

with this (potential) partner, this partner’s general reputa-

tion and the broader institutional environment in which

this partner is embedded.

Asset specificity

A variety of forms of asset specificity have so far been

identified in literature (for an overview see David and Han,

2004; Geyskens et al., 2006). These include property, whose

value is specific to a particular site, customized physical

assets and human capital, as well as processes and products

tailored to a particular application. The asset specificity of a

transaction refers to the degree to which the assets that

support the transaction can be redeployed to ‘alternative

uses and alternative users without sacrifice of productive

value’ (Williamson, 1991: 282). Since it measures how

easily assets can be redeployed outside a particular bilateral

exchange relationship, it also serves as a measure for the

degree of bilateral dependency (David and Han, 2004;

Geyskens et al., 2006). To define asset specificity for our

study, we adopted proven measurement concepts from

other studies (including Anderson and Schmittlein, 1984;

Heide and John, 1990; Coles and Hesterly, 1998; Joshi

and Stump, 1999). We used a 5-item scale that measures

the degree to which human assets, physical assets and

organizational processes are specific to the considered

transaction.

Measurement difficulties

Interestingly, only a few empirical studies have so far

tried to define measurement difficulties. To measure the

difficulties in monitoring and evaluating the performance

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

107

of the transaction partner, we used a 2-item scale based on

Anderson (1985), John and Weitz (1989) and Poppo and

Zenger (1998). The first item measures the accuracy with

which the operational performance of the (potential)

exchange partner could be measured. The second item

measures the degree of transparency of the economic

benefits gained by the (potential) exchange partner from

the transaction.

Control variables

Since some studies report a significant direct effect of

environmental uncertainty on vertical integration, we

elected to use environmental uncertainty as a control

variable in our study. TCE proposes that environmental

uncertainty may have an effect on the decision to either

cooperate with an external exchange partner or integrate a

transaction and it therefore seemed appropriate to assess its

impact. For a detailed discussion of the mixed findings on

the relationship between environmental uncertainty and

vertical integration, see Krickx (2000), David and Han

(2004) and Geyskens et al. (2006). We categorized

environmental uncertainty into market (4-item measure)

and technological uncertainty (3-item measure). The items

are based on Walker and Weber (1987), Zaheer and

Venkatraman (1995), Robertson and Gatignon (1998) and

Sutcliffe and Zaheer (1998).

Researchers following a resource-based view of the firm

claim that the resources needed for a certain strategic

activitiy also play a crucial role in alliance decisions (e.g.

Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven, 1996; Madhok and Tallman,

1998; Das and Teng, 2000). Recent research offers strong

empirical support for the assumption that firms tend to

concentrate on activities where they possess – or are able to

build up – superior competences (e.g. Leiblein and Miller,

2003; Mayer and Nickerson, 2005). Consequently, we

included a control variable representing internal barriers

and constraints to develop the required competences

internally.

Empirical evidence shows that firms with high alliance

experience might have a greater propensity to cooperate

(and also be more successful in partnering) than firms with

low alliance experience, making cooperation experience a

further important control variable. Cooperation experience

was measured using a single item measure to determine

how much experience the responding firm had in managing

cooperative relationships.

Since a firm’s governance choices depend on its size, we

included firm size to control for a possible effect on the

make-or-cooperate decision. In line with previous research,

this variable was measured by the number of employees in

the organization. For data analysis, we used the natural

logarithm of the number of employees.

Methods and results

For the multi-item variables, each set of items was initially

subjected to item-to-total correlation to identify items that

did not belong to the specific theoretical construct. To

verify unidimensionality, a confirmatory factor analysis was

subsequently carried out for each multi-item variable using

the remaining sets of items (see e.g. Heide and John, 1990;

Stump and Heide, 1996). For every multi-item variable,

each set of items was hypothesized to be represented by a

single factor. Our results confirmed this hypothesis, and in

case of every multi-item variable the factor loadings exceed

0.4, which is seen to be an acceptable level (e.g. Stump and

Heide, 1996). To complete the construct validation process,

reliability was computed. All alpha coefficients of the multi-

item constructs display satisfactory levels of reliability,

i.e. greater than the 0.7 level recommended (e.g. Celly and

Frazier, 1996; see Table 2, alpha coefficients in parenth-

eses), with the exception of measurement difficulties, which

falls short of this threshold with an alpha coefficient of only

0.60. However, since this construct consists of only two

items with an inter-item-correlation of 0.43, the reliability

of measurement difficulties also lies at a satisfactory level.

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix with alpha coeffi-

cients, means and standard deviation. Unstandardized

means and standard deviations are reported for informa-

tion purposes; standardized variables (z-score transforma-

tion) are used in the analysis except for the dependent

variable. Correlations of the independent variables were

generally as expected and moderate in magnitude. Only the

measurement difficulties variable is significantly (P

o0.01)

correlated to asset specificity and trust. In addition, trust is

also significantly (P

o0.01) correlated with cooperation

experience.

Table 2 Means, standard deviations and correlations

a

Independent variables

Mean

SD

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1. Ln (size)

3,088.31

b

12,334.63

b

2. Cooperation experience

4.32

1.53

0.27**

3. Resource barriers

3.42

1.87

0.12

0.17*

4. Market uncertainty

4.55

1.34

0.13

0.07

0.09

(0.85)

5. Technological uncertainty

3.85

1.56

0.11

0.03

0.13

0.09

(0.81)

6. Trust

5.27

1.14

0.01

0.24** 0.01 0.01

0.03

(0.83)

7. Asset specificity

4.21

1.29

0.04

0.07

0.03

0.01

0.15

0.07

(0.72)

8. Measurement difficulties

3.27

1.42

0.19*

0.28**

0.06

0.09

0.17* 0.26**

0.23** (0.60)

a

n

¼ 151.

b

Size.

*P

o0.05, **Po0.01, two-tailed tests.

Alpha coefficients appear on the diagonal in parentheses.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

108

To test Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, we used hierarchical

logistic regression analysis because the dependent variable,

integration, is binary (Jaccard, 2001; Cohen et al., 2003).

These hypotheses were tested in three logistic regression

models (see Table 3).

Model 1 consists of all control variables. In model 2, all

main effects were added, while model 3 shows the full

model with the hypothesized interaction effects added. It

consists of (1) the set of control variables (firm size,

cooperation experience, resource barriers, market uncer-

tainty and technological uncertainty), (2) the main effects

from the second model, i.e. trust (Hypothesis 3), asset spe-

cificity and measurement difficulties, and (3) the inter-

action effects of trust and asset specificity (Hypothesis 1)

and trust and measurement difficulties (Hypothesis 2).

As Table 3 shows, the control variables in model 1 differ

regarding the significant impact on vertical integration. Our

results indicate that the characteristics of the resources

needed significantly affect boundary decisions. Internal

barriers and constraints to develop the required resources

internally significantly favor cooperation (0.65, P

o0.01,

odds ratio of 0.53). Considering the environmental

uncertainties, our results show a weak positive effect of

technological uncertainty on integration (0.36, P

o0.1, odds

ratio of 1.43) whereas no effect was found for market

uncertainty. However, as the further models show, the effect

of technological uncertainty seems to be not very robust.

This evidence is in line with the mixed empirical findings

on the influence of environmental uncertainty on boundary

choices (David and Han, 2004). Since TCE suggests an

impact of environmental uncertainty on governance

decisions, we tested for both the direct effect of environ-

mental uncertainty as well as for any interaction effects with

TCE variables, but found no significant results in our

sample. Similarly, in our data neither cooperation experi-

ence nor firm size play a significant role in boundary

decisions.

In model 2, the main effects, i.e. the effect of trust,

asset specificity and measurement difficulties on integra-

tion, were tested. Our results show that, in accordance with

Hypothesis 3, the higher the degree of trust in the

(potential) transaction partner, the lower the propensity

of the firm to integrate a strategically important activity

(0.73, P

o0.001, odds ratio of 0.48). We also found

support that the presence of the transaction characteristics

asset specificity and measurement difficulties positively

influences the integration decision (0.55, P

o0.05, odds

ratio of 1.73 and 0.52, P

o0.05, odds ratio of 1.68), which is

consistent with TCE reasoning and numerous previous

empirical studies.

In model 3, the two interaction terms test for the indirect

effect of trust on the make-or-cooperate decision to

examine the hypothesis that trust will attenuate the direct

effect of asset specificity (Hypothesis 1) and measurement

difficulties (Hypothesis 2), respectively. As Table 3 shows,

both hypotheses are indeed supported (P

o0.05). Moreover,

the odds ratio estimates indicate that each of these

significant interaction terms has a lower odds ratio than

the main effects of the TCE variables (Jaccard, 2001;

Santoro and McGill, 2005), indicating that the probability of

integration declines in combination with trust.

With regard to the goodness-of-fit statistics, the

chi-square goodness-of-fit estimates associated with all

models were significant (model 1 with P

o0.01, model 2 and

model 3 with P

o0.001). Furthermore, both models 2 and 3

significantly improve the prior models (P

o0.001 and

Table 3 Results of logistic regression analysis for Hypotheses 1, 2 3

a

Independent variables

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

Step 1: Control variables

Ln (size)

0.02 (0.09) 1.02

0.02 (0.11) 1.02

0.03 (0.11) 0.97

Cooperation experience

0.24 (0.19) 0.79

0.06 (0.22) 1.06

0.08 (0.24) 0.92

Resource barriers

0.65** (0.20) 0.53

0.80*** (0.23) 0.45

0.97*** (0.26) 0.38

Market uncertainty

0.20 (0.18) 1.22

0.19 (0.22) 1.21

0.19 (0.22) 1.21

Technological uncertainty

0.36

+

(0.19) 1.43

0.34 (0.22) 1.41

0.48* (0.23) 1.62

Step 2: Main effects

Trust

0.73*** (0.22) 0.48

0.93*** (0.26) 0.40

Asset specificity

0.55* (0.23) 1.73

0.58* (0.24) 1.78

Measurement difficulties

0.52* (0.22) 1.68

0.56* (0.25) 1.75

Step 3: Interaction

Asset specificity trust

0.58* (0.25) 0.56

Measurement difficulties trust

0.67* (0.26) 0.51

Log-likelihood

185.38

153.96

140.16

Chi

2

18.04**

49.46***

63.26***

Likelihood ratio test (df) vs prior model

31.42 (3)***

13.80 (2)**

Pseudo-R

2

0.15

0.38

0.46

a

n

¼ 151.

Standardized regression coefficients and adjusted R

2

are reported with standard errors in parentheses and odds ratio estimates in bold.

+

P

o0.1, *Po0.05, **Po0.01, ***Po0.001, two-tailed tests.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

109

P

o0.01 respectively), and a different measure of fit, the

pseudo R

2

, underscores these findings. Hence, our results

emphasize both the importance of the direct effect of trust,

asset specificity and measurement difficulties, as well as

the moderating effect of trust on the make-or-cooperate

decision.

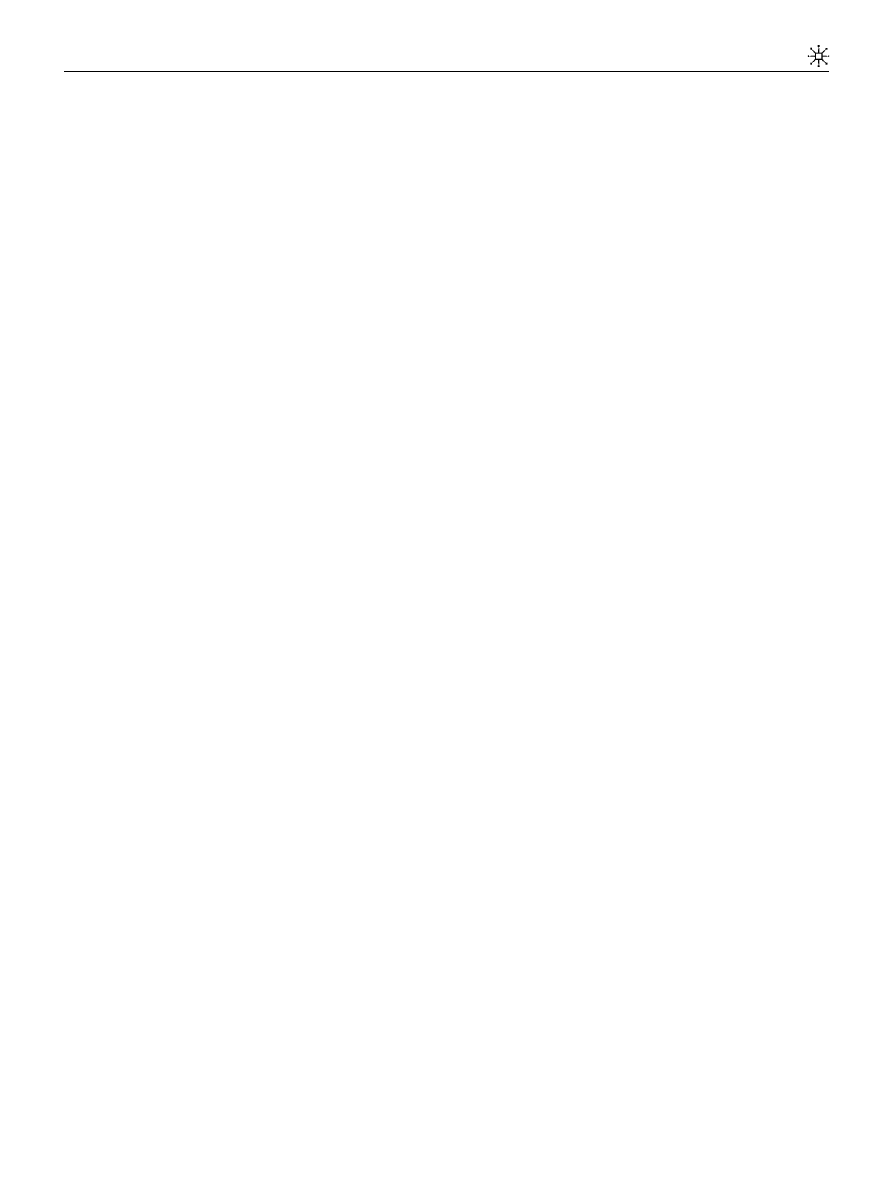

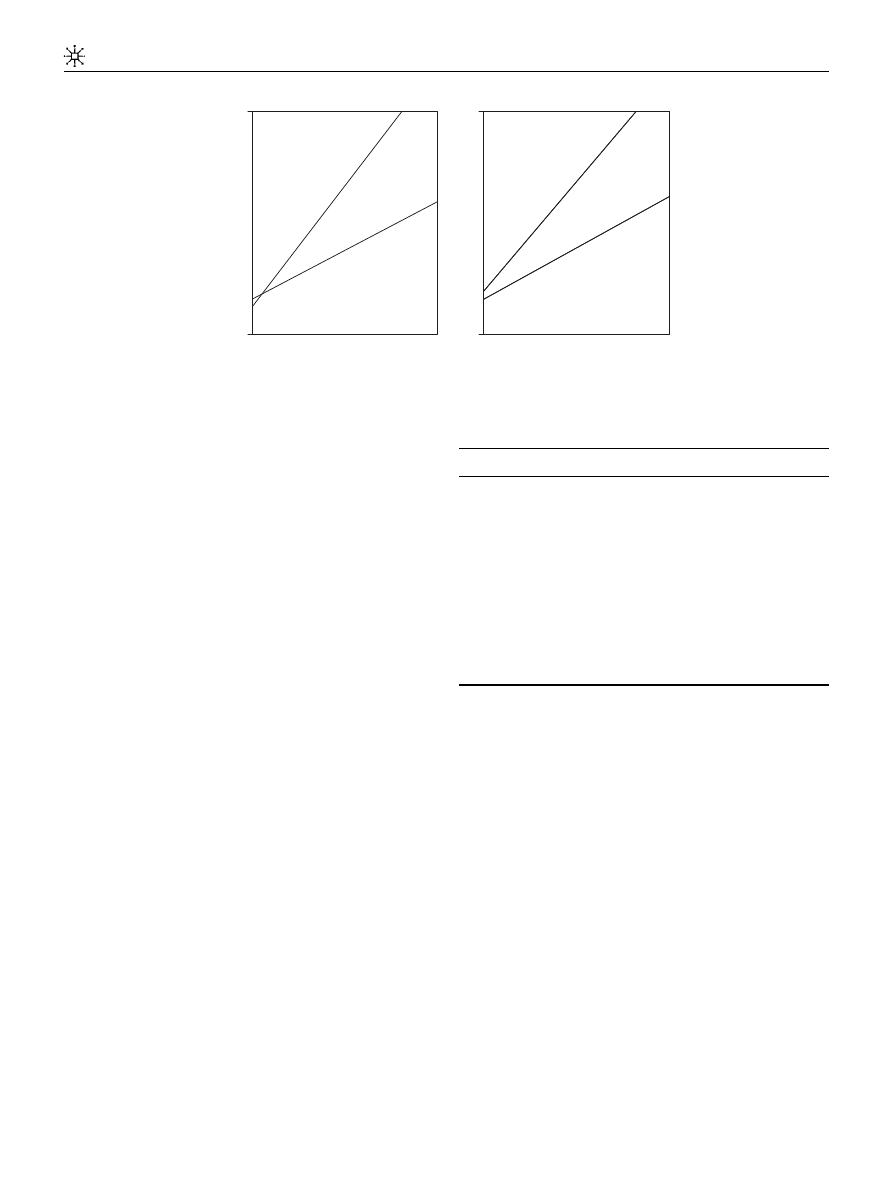

To further assess the implications of the regression

results, we plotted the relationship between the probability

of integration (as opposed to cooperation) on one axis and

asset specificity on the other axis, using separate graphs to

represent the different levels of trust. We also created a

similar plot for measurement difficulties as the independent

variable (see Figure 1). For this purpose, we split our

sample in two data sets: one containing all ‘high trust cases’

(trust44) and one containing all ‘low trust cases’ (trust

o ¼ 4).

The two graphs in Figure 1 illustrate that our data indeed

support Hypotheses 1 and 2. They show that the effects of

asset specificity and measurement difficulties on vertical

integration are much stronger when trust between the

transaction partners is low. In ‘high trust cases’, the direct

effects of the two TCE variables on vertical integration are

significantly attenuated.

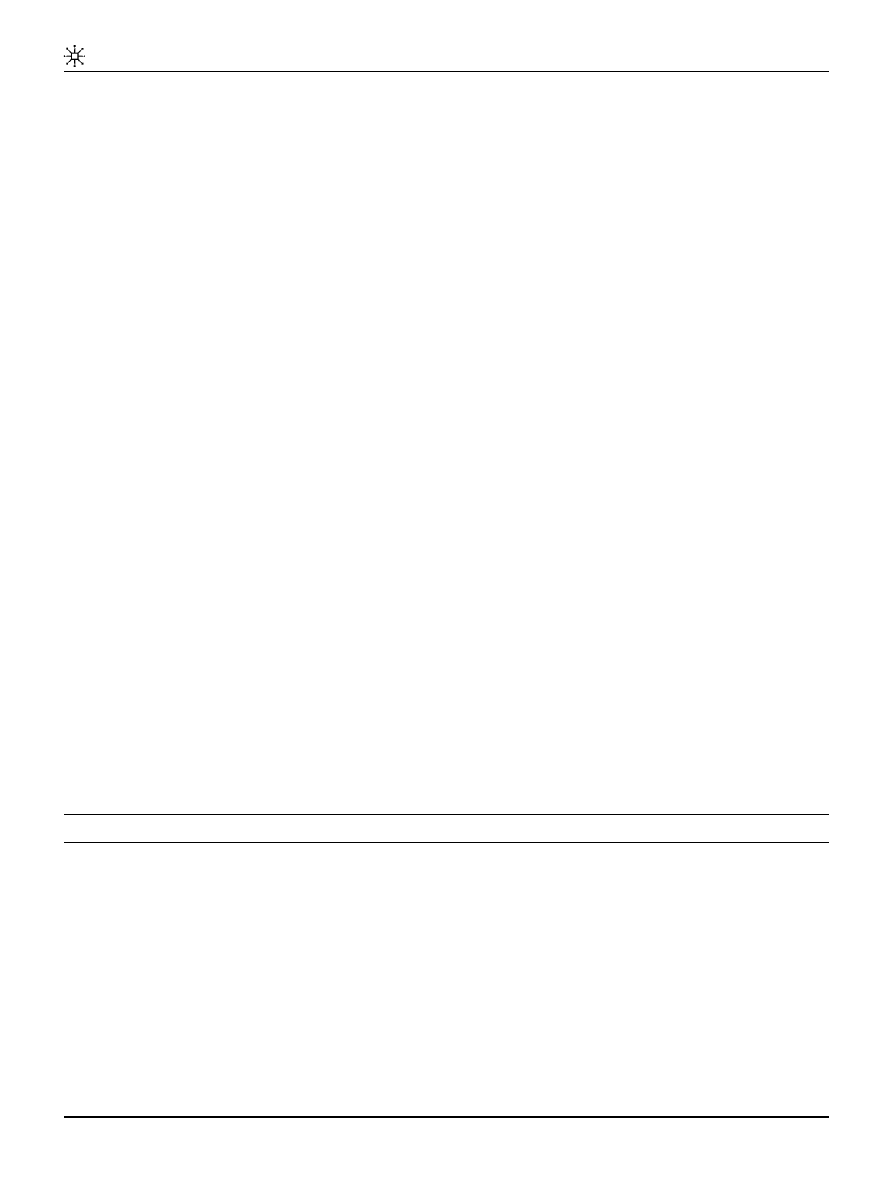

Hypothesis 4 suggests that interorganizational trust

would have a negative effect on integration even when the

threat of opportunistic behavior is low. We created a new

variable opportunism by combining both drivers of oppor-

tunistic behavior according to TCE, asset specificity and

measurement difficulties. To test Hypothesis 4, we calcu-

lated the interaction effect of trust and opportunism by

categorizing the variable opportunism threefold: value zero

for all cases less than 3, value one for all cases between 3

and 5, and value two for all cases more than 5. The full

regression model consists of all control variables used in

the calculations of Hypotheses 1–3, the direct effect of trust

and the categorized variable of opportunism, and the

interaction effect between the two. The results of the

regression analysis show that trust indeed has a significant

negative effect on integration even when the magnitude of

opportunism is low (see Table 4).

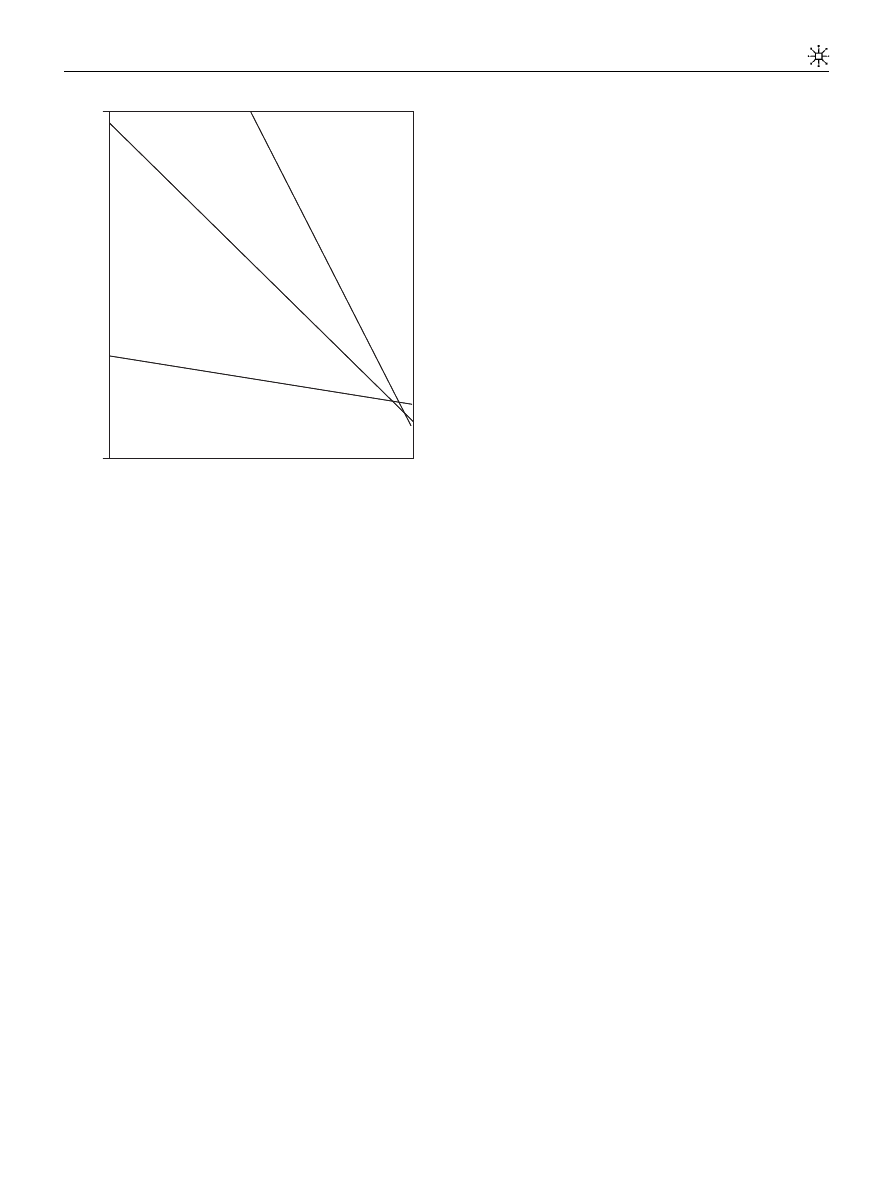

Again, we plotted a graph (Figure 2) to further illustrate

these results. We considered opportunism, according to the

regression results to be low only in cases with a value less

than 3 and high in cases more than 5. For illustration

purpose we also include graphically the overall negative

effect of trust on the probability of performing an activity

in-house. This graph shows that trust has an influence on

the boundary choice even in cases with low opportunism,

i.e. there is still a negative influence on the probability of

performing an activity in-house. However, Figure 2 also

indicates that the influence of trust on boundary choices

plays a more important role when opportunism is

considered to be high.

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical implications

The purpose of this paper is to contribute to providing a

better understanding of the role of trust in decisions

on firm boundaries. Bringing together explanations on the

Probability of integration

1

0

Asset specificity

Low trust

High trust

High

Low

Probability of integration

1

0

Measurement difficulties

Low trust

High trust

High

Low

Figure 1 Interaction effects of trust and asset specificity and trust and measurement difficulties on integration.

Table 4 Results of logistic regression analysis for Hypothesis 4

a

Independent variables

Model

Ln (size)

0.07 (0.11) 0.93

Cooperation experience

0.13 (0.23) 0.88

Resource barriers

0.99*** (0.26) 0.37

Market uncertainty

0.16 (0.23) 1.18

Technological uncertainty

0.51 (0.23)* 1.67

Trust

1.01*** (0.27) 0.36

Opportunism

0.81** (0.26) 2.26

Opportunism trust

0.99** (0.30) 0.37

Log-likelihood

141.73

Chi

2

61.68***

Pseudo-R

2

0.45

a

n

¼ 151.

Standardized regression coefficients and adjusted R

2

are

reported with standard errors in parentheses and odds ratio

estimates in bold.

*P

o0.05, **Po0.01, ***Po0.001, two-tailed tests.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

110

impact of trust from TCE and research on the value-

enhancing role of trust in strategic alliances, we analyze the

role of trust in the decision to either perform a strategically

important transaction in-house (‘make’) or handle it in

a long-term cooperative arrangement with an external

exchange partner (‘cooperate’). In particular, we use a

broad concept of trust that encompasses three different lines

of theorizing on the role of trust in governance choices –

TCE, transaction value-based theories and sociological

views – to disentangle opportunism-based and opportu-

nism-independent effects of trust. Our empirical results

confirm the relevance of both opportunism-based and

opportunism-independent explanations of the role of trust

in boundary choices. With respect to opportunism-based

explanations, our data provide strong evidence for the

TCE proposition that trust moderates the effect of asset

specificity on the decision to vertically integrate an activity

or carry it out with an independent exchange partner. We

extended the standard TCE explanation by including the

difficulties of measuring an exchange partner’s perfor-

mance in our model. Our data confirm that performance

measurement difficulties – in addition to asset specificity –

significantly influence make-or-cooperate choices. More-

over, we also anticipated a moderating effect of trust on

the influence of performance measurement difficulties on

make-or-cooperate decisions. This is confirmed by the

study and our results provide empirical evidence for the

existence of such a moderating effect. Since the negative

effect of trust on integration is shown to be significantly

stronger in cases where the threat of opportunistic behavior

is high, our study confirms theoretical reasoning and prior

empirical evidence that interorganizational trust reduces

transaction costs by mitigating the threat of opportunistic

behavior and enables firms to choose a less expensive

governance mode than vertical integration.

While our opportunism-based interpretation of inter-

organizational trust corresponds to Williamson’s (1993)

view that trust can be reduced to calculative behavior

(reserving non-calculative forms of trust for ‘personal

relations’, e.g. within families) in the context of economic-

ally relevant exchange relationships, we nonetheless pro-

pose that the role of trust in governance choices goes well

beyond averting the transaction costs stemming from

opportunistic behavior. Indeed, our study is the first to

provide empirical evidence that trust has a significant

positive impact on collaboration even for transactions with

a low danger of opportunistic behavior (stemming from

asset specificity and measurement difficulties) and for

which TCE would not propose a significant effect of trust

on the make-or-cooperate choice.

This opportunism-independent effect of interorganiza-

tional trust can be explained using both economic and non-

economic considerations. From an economic perspective,

interorganizational trust increases the transaction value

of a collaborative exchange by positively influencing the

breadth, depth and longevity of collaboration. Therefore, a

higher level of interorganizational trust makes collaborative

exchange economically more beneficial. This insight is parti-

cularly important with regard to opportunism-independent

theories of firm boundaries. A number of authors have

argued that firms provide specific mechanisms for identi-

fication, coordination, communication and knowledge

sharing, which generate value yet are not available through

market contracting (see e.g. Rumelt, 1995: 124; also Cohen

and Levinthal, 1990; Conner and Prahalad, 1996; Demsetz,

1988; Kogut and Zander, 1996; Poppo and Zenger, 1998).

While we agree with this view, we also contend that such

gains can – at least in part – also be realized within a

trusting collaboration. Hence, interorganizational trust can

substitute at least some of the merits of ‘belonging to the

same firm’ and make a collaborative arrangement more

valuable. In addition, a collaborative exchange with another

firm can generate relational rents (Dyer and Singh, 1998) by

effectively accessing external resources. Consequently, we

conclude that a high level of interorganizational trust

enables the cooperating firms to enjoy many of the advan-

tages typically found in hierarchical governance and, at the

same time, to more fully exploit the value creation potential

that comes from a collaborative exchange.

Looking beyond these opportunism-independent, yet

calculative explanations of interorganizational trust, we

also propose a non-economic explanation of the empirically

established opportunism-independent effect of interorga-

nizational trust. From a non-calculative perspective, social

(institutional) processes and pressures can also increase the

likelihood of collaborative exchange. Here, the decision to

collaborate (and to trust an external exchange partner) is

not so much the result of a calculation of the most

beneficial governance mode for a given transaction from an

economic perspective, but rather emerges as a result of

social norms, bonds and obligations. In particular, norms

of reciprocity and indebtedness as well as social proximity

(‘belonging to the same group’) can lead to collaborative

behavior independent of economic considerations. This

interpretation of the findings of our study is in line with the

Probability of integration

Trust

High

Low

High opportunism

All cases

1

0

Low opportunism

Figure 2 The effect of trust on integration when the threat of opportunism

is low.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

111

theoretical reasoning for interorganizational trust proposed

by neo-institutionalism (Zucker, 1987; Oliver, 1990) and

socio-psychology (Baier, 1986; Ring, 1996). Although we

argue that their interrelatedness makes it difficult to clearly

differentiate empirically between the different kinds of

opportunism-independent interorganizational trust, our

classification and discussion of the different effects of

interorganizational trust contributes to providing a better

understanding of the different roles of trust and, particu-

larly, to the controversial discussion on the relation

between trust and calculativeness (see e.g. Craswell, 1993;

Saparito et al., 2004; Bromiley and Harris, 2006).

Managerial implications

Trust does matter! Our study confirms anecdotes by

executives who, for a long time, have been pointing to the

central importance of inter-organizational trust for bound-

ary decisions.

Companies that have been able to develop and maintain

trustful relationships with a number of other companies do

have a fundamental strategic advantage. This social capital

makes it possible for the focal company to organize certain

activities more efficiently and flexibly with exchange

partners. Even when exchange hazards are low, the level

of trust between exchange partners plays an important role.

A high level of trust between them not only reduces

transaction costs but also enhances transaction value.

However, our argument that also non-calculative motives

might increase the propensity of companies to cooperate

sheds light on a potential danger: firms might choose a

cooperative exchange that is not economically beneficial to

them. Firms need to be aware that in situations character-

ized by repeated ties with a specific exchange partner, this

might lead to interorganizational inertia in the long run.

When firms are reluctant to terminate an established

cooperative relationship that is not economically beneficial

anymore, this will negatively influence their competitive-

ness and performance.

Limitations

As with all empirical studies, our study is not free from

several limitations. The findings of this empirical study are

based on data from 151 make-or-cooperate decisions in one

industry sector (automotive supply). Our sociological

considerations clarify the fact that the role of trust is, in

many ways, contingent on the ‘sociological context’ (see

Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998). Cultural context,

values and practices strongly impact human behavior and

vary not only at the industry and organization level, but

also at the social level (Hofstede, 1980; House et al., 2004).

Gelfand et al. (2004: 457) note that the nature and impor-

tance of organizational trust vary with the level of

individualism/collectivism in the cultural context (Sako,

2000; Dyer and Chu, 2003; Huff and Kelley, 2003). The

automotive industry in Austria and Southern Germany is

characterized by a dense network of interorganizational

relationships. The different firms all know each other fairly

well and most of them are members of an ‘automotive

cluster’. These factors might result in a relatively important

role for trust and limit the generalizability of the empirical

results to other cultural contexts and to other industries. In

environments where the economic actors are not embedded

in a dense network of relationships, effects that rely on social

embeddedness might play a less prominent role. Thus, one

could argue that in such situations (industries) the impor-

tance of non-calculative trust will be lower than in highly

connected settings.

Moreover, our analysis does not focus on how trust is

created and extended, although it would indeed be

interesting to compare economic rationales for the creation

of trust with sociological views (on this see e.g. Sabel, 1993).

Obviously, the reasons why people trust each other may

be important in differentiating empirically between the

different forms of interorganizational trust and their

different effects on governance decisions. Our study is only

a first step towards exploring the specific effects of the

different aspects of interorganizational trust on governance

choices in greater detail. A dynamic and socialized view of

trust, which takes account of how it is generated and how

the trust-building process interacts with boundary choices,

could provide important additional insights (Gulati, 1995;

Goerzen, 2007; Puranam and Vanneste, 2009). Such an

analysis may even help to overcome the problem of how

to distinguish empirically between the different forms of

opportunism-independent interorganizational trust and

explore the relative importance and combined effects of

its calculative and non-calculative elements on boundary

choices.

Note

1 We use the terms transaction and exchange synonymously.

References

Alchian

, A. A. and H. Demsetz, 1972, ‘‘Production, information costs, and

economic organization’’. American Economic Review, 62: 777–795.

Anderson

, E., 1985, ‘‘The salesperson as outside agent or employee:

A transaction cost analysis’’. Marketing Science, 4: 234–255.

Anderson

, E. and D. C. Schmittlein, 1984, ‘‘Integration of the salesforce:

An empirical examination’’. Rand Journal of Economics, 15: 385–395.

Armstrong

, J. S. and T. S. Overton, 1977, ‘‘Estimating nonresponse bias in mail

surveys’’. Journal of Marketing Research, 14: 396–402.

Artz

, K. W. and T. H. Brush, 2000, ‘‘Asset specificity, uncertainty and

relational norms: An examination of coordination costs in collaborative

strategic alliances’’. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 41:

337–362.

Aulakh

, P. S., M. Kotabe and A. Sahay, 1996, ‘‘Trust and performance in

cross-border marketing partnerships: A behavioral approach’’. Journal of

International Business Studies, 27: 1005–1032.

Bachmann

, R., 2001, ‘‘Trust, power and control in trans-organizational

relations’’. Organization Studies, 22: 337–365.

Bachmann

, R. and A. Zaheer (eds.) 2006, Handbook of trust research.

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Baier

, A., 1986, ‘‘Trust and antitrust’’. Ethics, 96: 231–260.

Barney

, J. B., 1999, ‘‘How a firm’s capabilities affect boundary decisions’’.

Sloan Management Review, 40: 137–145.

Barney

, J. B. and M. H. Hansen, 1994, ‘‘Trustworthiness as a source of

competitive advantage’’. Strategic Management Journal, 15: 175–190.

Barzel

, Y., 1982, ‘‘Measurement costs and the organization of markets’’. Journal

of Law and Economics, 25: 27–48.

Bigley

, G. A. and J. L. Pearce, 1998, ‘‘Straining for shared meaning in

organization science: Problems of trust and distrust’’. Academy of

Management Review, 23: 405–421.

Bradach

, J. L. and R. G. Eccles, 1989, ‘‘Price, authority and trust: From ideal

types to plural forms’’. Annual Review of Sociology, 15: 97–118.

Effect of interorganizational trust

Werner H Hoffmann et al

112

Bromiley

, P. and L. L. Cummings, 1995, ‘‘Transaction costs in organizations

with trust’’. In R. Bies, B.H. Sheppard and R. Lewicki (eds.) Research

on negotiation in organizations, Vol.5. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press,

pp. 219–247.

Bromiley

, P. and J. Harris, 2006, ‘‘Trust, transaction cost economics, and

mechanisms’’. In R. Bachmann and A. Zaheer (eds.) Handbook of trust

research. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 124–143.

Carson

, S. J., A. Madhok, R. Varman and G. John, 2003, ‘‘Information

processing moderators of the effectiveness of trust-based governance in

interfirm R&D collaboration’’. Organization Science, 14: 45–56.

Celly

, K. S. and G. L. Frazier, 1996, ‘‘Outcome-based and behavior-based

coordination efforts in channel relationships’’. Journal of Marketing

Research, 33: 200–210.

Cheung

, S. N. S., 1983, ‘‘The contractual nature of the firm’’. Journal of

Law & Economics, 26: 1–21.

Chiles

, T. H. and J. F. McMackin, 1996, ‘‘Integrating variable risk preferences,

trust, and transaction cost economics’’. Academy of Management Review, 21:

73–99.

Coase

, R. H., 1937, ‘‘The nature of the firm’’. Economica, 4: 386–405.

Cohen

, J., P. Cohen, S. G. West and L. S. Aiken, 2003, Applied multiple

regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Cohen

, W. M. and D. A. Levinthal, 1990, ‘‘Absorptive capacity: A new