Simposium Sains Kesihatan Kebangsaan ke 7

Hotel Legend, Kuala Lumpur, 18 – 19 Jun 2008 : 202 – 204

Chronic pain and psychological well-being

Farezadi, Z.

1

, *Normah, C. D.

1

, Zubaidah, J.

2

& Maria, C.

3

1

Health Psychology Unit, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia,

Jalan Raja Muda Abdul Aziz, 50300 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia,

Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan

3

Department of Anaesthesiology, Hospital Selayang, Selangor Darul Ehsan

*Corresponding author: Tel: +603-92897048; Fax: +603-26911052; Email address: normah@medic.ukm.my

Chronic pain and psychological distress have been found to

frequently co-occur. The aim of this study is to evaluate the

relationship between pain intensity, physical disability, self-

efficacy, active coping, catastrophizing and psychological

distress (stress/tension, anxiety, and depressive symptoms.

Data were collected from 88 chronic pain patients who were

referred to the pain clinic in Selayang Hospital. The data

collected include sociodemographic data, pain intensity using

the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), physical disability by using

the Physical Disability Questionnaire (PDQ), psychological

distress assessed by the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

(DASS-42), pain self-efficacy assessed by the Pain Self-

Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) and catastrophizing thoughts

by using the Pain Responses Self-Statement (PRSS).Self-

efficacy showed negative correlation with both physical and

psychological variables while catastrophizing have positive

correlation with physical and psychological aspect of pain.

Active coping have negative correlation with physical profiles

but showed positive association with psychological aspects of

pain. This study provides information about variables and

factors associated with psychological well-being of chronic

pain sufferers and provide implications on the aspects of

treatment modalities in managing chronic pain patients.

Introduction

Pain, particularly chronic pain, is one of the most common threat

to the quality of life (QOL) worldwide and will become more so

as the age increases. The burden of unrelieved pain is also a major

problem for health services throughout the world.

Pain is a widespread human experience. The International

Association for the Study of Pain defined pain as “an unpleasant

sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or

potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such

damage“(Merskey, 1986). Current understanding and concepts of

pain are based on the developments from the Gate Control Theory

of Pain suggested by Melzack and Wall (1965). The internal

biopsychosocial variables that may influence the pain responses

include the autonomic, immune, stress regulation, and

endogenous opioid system. The psychological variables that may

influence the pain responses include cultural factors, past

experiences, personality, attention, motivational and cognitive

factors (Melzack, 1999a).

Chronic pain does not have any clear biological function and

is usually associated with negative impact on the physical,

psychological and social well-being of the individual (Stembach,

1989). Bonica (1990) defined chronic pain as “pain that persists

beyond the usual course of an acute disease; or persists more than

a reasonable time for an injury to heal or is associated with a

chronic pathological process that causes continuous pain; and

recurs at intervals for months or years”. Its origin, duration,

intensity, and specific symptoms vary. In terms of duration,

chronic pain has been defined as pain lasting longer that three or

six months (Merskey & Bogduk, 1994).

Pain that is not controlled can generate serious physical,

psychological and social effects and can have a disruptive impact

on a person’s daily life. The physical effects may include

progressive physical deterioration such as general fatigue and

debility caused by disturbance of sleep, appetite, decreased

physical activity, side effects from excessive medication (Von

Korff & Simon, 1996).

Most patients with chronic pain experience emotional

distress to a varying degree. The emotional impacts of chronic

pain include reactive depression, hopelessness, despair and

dependency, loss of sleep, loss of self-worth, loss of mobility,

anxiety over the pain itself and also how the patient is perceived

by their family and peers, loss of employment, anger directed

outward in generalized manner, and in some cases, suicide. A

variety of factors such as the nature and prognosis of the

condition, coping abilities, social support, attitudes and behaviors

of health professionals and patient’s beliefs can contribute to the

extent of emotional distress (Skevington, 1995). Other factors

include locus of control, stress level, self-efficacy and negative

thoughts. Active coping strategies were related to reduce pain

severity, lower levels of depression and less functional

impairment while the reverse applied to passive coping strategies

(Nicholas, 1987). Negative thinking such as catastrophizing has

always been found to be significantly related to heightened pain

severity in a variety of chronic pain conditions and related to

lower pain thresholds and pain tolerance levels in normals

(Sullivan et al, 2001). Self-efficacy refers to the ability to cope

effectively or exert control over pain. Self-efficacy was found to

have significant inverse correlation with pain intensity and

interference with life (Lin, 1998).

The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationships between

pain intensity, physical disability, self-efficacy, active coping,

catastrophizing and psychological distress (stress/tension, anxiety,

and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Participants

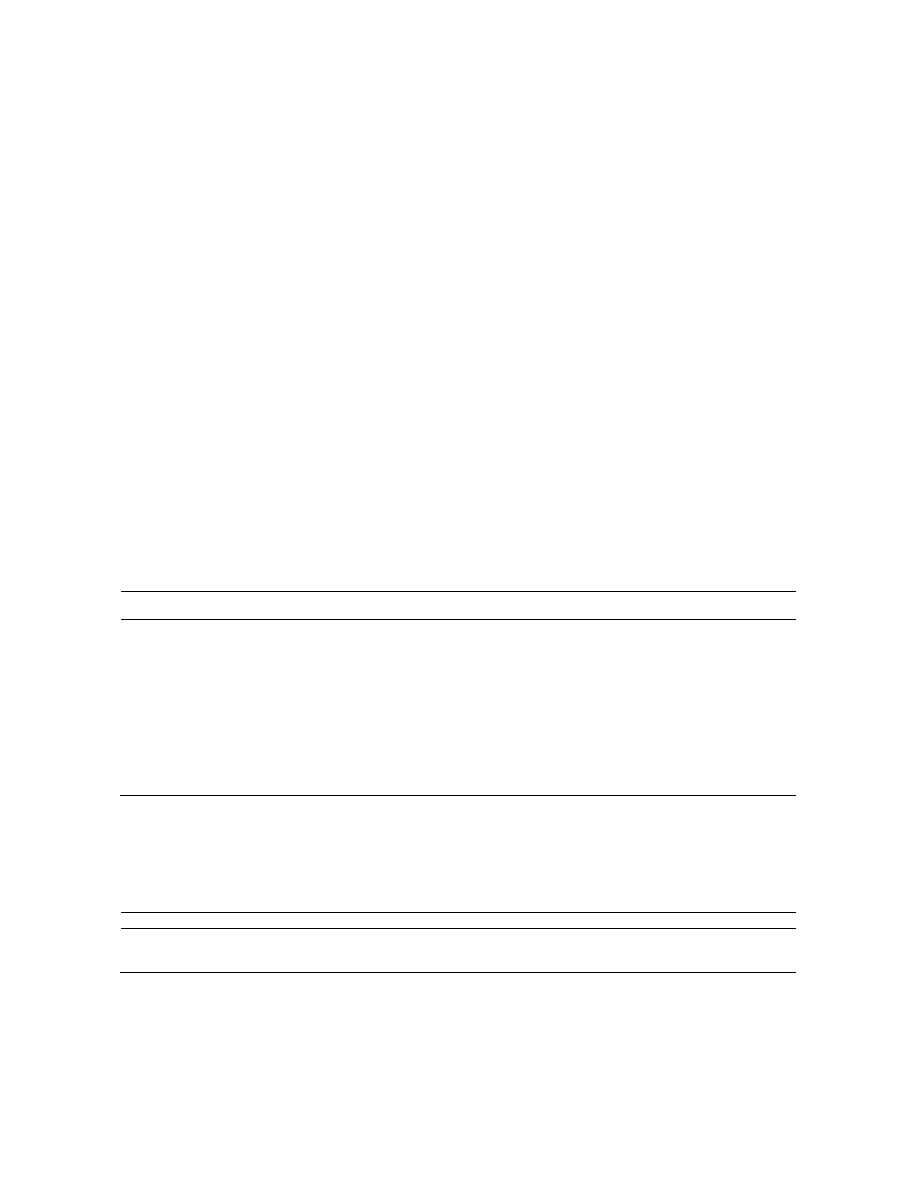

Participants were 88 chronic pain patients recruited from

Selayang Hospital, Selangor. of the 88 patients, 54.5% were

females and 45.5% were males, The average age was 48 ± 12

years old. The majority of patients were married (64.8%),

working (67%) and aged above 41 years old (77.3%). In terms of

ethnicity, 39.8% were Malay, 18.2% Chinese, and 6.8% were

other races (Table 1).

Research Design

Sihat2008

ISBN 978-983-43150-9-2

Farezadi, Z. et al./Sihat2008 : 202 – 204

203

This is a retrospective study. Pain profiles were gathered from the

Pain Management Clinic, Selayang Hospital, Selangor from 2004

to 2007.

Measures

The data collected include the sociodemographic data, pain

intensity using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), physical

disability by using the Physical Disability Questionnaire

(PDQ)(Roland & Morris, 1983), psychological distress assessed

by the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-42)(Lovibond &

Lovibond, 1995), pain self-efficacy assessed by the Pain Self-

Efficacy

Questionnaire

(PSEQ)(Nicholas,

1989)

and

catastrophizing thoughts by using the Pain Responses Self-

Statement (PRSS).

Result

Self-efficacy in general has significant negative correlation with

pain intensity (r = -.219, p < .05), physical disability (r = -.366, p

< .01), stress (r = -.279, p < .01), anxiety (r = -.251, p < .05), and

depression (r = -.380, p < .01)(Table 2). Catastrophizing in

general has significant positive correlation with pain intensity (r =

.416, p < .01), stress (r = .564, p < .01), anxiety (r = .485, p < .01),

and depression (r = .633, p < .01). Active coping in general has no

significant correlation with pain intensity, physical disability,

stress, anxiety and depression.

Discussion

Self-efficacy in general has significant negative correlation with

pain intensity, physical disability, stress, anxiety and depression.

This means that high self-efficacy reduced the pain instensity,

physical disability, stress, anxiety and depression. This result is

consistent with previous findings by other researchers (Arnstein et

al., 1999; Lynch et al., 1996; Sharloo & Kaptein, 1997).

Catastrophizing in general was found to have positive correlation

with pain intensity, stress, anxiety and depression but not with

physical disability. This means that high catastrophizing will

make the pain intensity and physical disability worse and increase

the level of stress, anxiety and depression. The result is supported

by previous research (Severeijns et al., 2001; Sullivan et al., 2001;

Turner et al., 2001).

Active coping in general has no significant correlation with pain

intensity, physical disability, stress, anxiety and depression. This

result was not supported by other research (Gatchel & Turk,

1999). The nonsignificant relationships can be related to the

coping strategies used which in any given situation are dependent

upon contextual factors and the individual’s appraisal of these. A

passive strategy in one instance may be in fact be adaptive in

another. Second, those with chronic conditions were more likely

to use a combination of various and varied coping responses to

manage their condition and adjust their life accordingly.

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic Data of Chronic Pain Patients

Variables

Frequency

Percent

Age

< 40 years old

20

22.7

> 41 years old

68

77.3

Gender

Male

40

45.5

Female

48

54.5

Ethnicity

Malay

35

39.8

Chinese

16

18.2

Others

6

6.8

Marital Status

Single

20

22.7

Married

57

64.8

Divorced/Widowed

11

12.5

Job Status

Working

59

67

Not Working

29

33

TABLE 2 Pearson Correlation between Self-Efficacy, Catastrophizing, and Active Coping with

Pain Intensity, Physical Disability, Stress, Anxiety and Depression

Pain Intensity

Physical Disability

Stress

Anxiety

Depression

Self-Efficacy

-.219*

-.366**

-.279**

-.251*

-.380**

Catastrophizing

.416**

.185

.564**

.485**

.633**

Active Coping

-.016

-.081

.034

.047

-.011

* p < .05, ** p < .01

Farezadi, Z. et al./Sihat2008 : 202 – 204

204

Conclusion

Chronic pain was found to be associated with psychological well-

being and psychological distress chronic patients. However, this

association was explained by other features, which are known to

be associated with such pain. Chronic pain itself does not

necessarily predict psychological distress, rather, other mediating

factors such as self-efficacy, catastrophizing and coping strategies

might play important role in affecting psychological well-being of

chronic pain patients. The findings support the argument that it is

the interaction between chronic pain, physical, and psychological

factors that influence patients’ psychological well-being.

Therefore, factors such as self-efficacy and catastrophizing should

not be overlooked in the treatment of patients with chronic pain.

Any treatment modalities utilized in treating chronic pain patients

should not only focus on the physical aspects of the patients, but

social and psychological aspects as well. Health practitioners

handling chronic pain patients need to evaluate patients’

psychological aspects so that treatment can be provided

effectively, for example, conducting treatments with the aims of

maximizing self-efficacy and minimizing catastrophizing.

Consequently, this may help chronic patients to improve their

psychological well-being.

References

Arnstein, P., Caudill, M., Mandle, C., Norris, A., & Beasley, R.

Self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between pain

intensity, disability and depression in chronic pain patients.

Pain 80: 483-491.

Bonica, J.J. 1990. Definition and taxonomy of pain. In: Bonica,

J.J. Ed. The Management of Pain, pp. 18-27. Pennsylvania:

Lea and Febiger.

Gatchek, R.J., & Turk, D.C. 1999. Psychosocial Factors in Pain:

Critical Perspectives. New York: The Guilford Press.

Lovibond, S.H., & Lovibond, P.F. 1995. Manual for the

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Australia: The

Psychological Foundation of New South Wales Inc.

Lynch, R.T., Agre, J., Powers, J.M., & Sherman, J. 1996. Long-

term follow up of outpatient interdisciplinary pain

management with a no-treatment comparison group.

American Journal of Physical Medical Rehabilitation 75:

213-222.

Melzack, R. 1999a. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain 6:

S121-126.

Melzack, R., & Wall, P.D. 1965. Pain mechanisms: A new theory.

Science 150: 971-979.

Merskey, H., & Bogduk, N. 1994. Classification of Pain,

Description of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definition of

Pain Terms. Seattle: IASP Press.

Merskey, H. 1986. Internal Association for the Study of Pain:

Classification of chronic pain. Pain 3: S217.

Nicholas, M.K. 1989. Self-efficacy and chronic pain. Paper

presented at the annual conference of the British

Psychological Society, St. Andrews.

Roland, M., & Morris, R. 1983. A study of natural history of back

pain, part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure

of disability in low back of pain. Spine 8: 141-144.

Severeijns, R., Vlaeyen, J.W., van den Hout, M.A., & Weber,

W.E. 2001. Pain catastrophizing predicts pain intensity,

disability, and psychological distress independent of the level

of physical impairment. Clinical Journal of Pain 17: 165-

172.

Skevington, S. 1995. Psychology of Pain. Chichester: John Wiley

& Sons.

Stembach, R.A. 1989. Acute versus chronic pain. In: Wall, P.D. &

Melzack, R. Eds. Textbook of Pain, pp. 242-246. Edinburgh:

Churchill Livingstone.

Sullivan, M.J., Thiorn, B., Haythornthwaite, J.A., Keefe, F.,

Martin, M., Bradley, L.A., & Lefebvre, J.C. 2001. Clinical

Journal of Pain 17: 52-64.

Turner, J.A., Dworkin, S.F., Mancl, L., Huggins, K.H., &

Truelove, E.L. 2001. The role of beliefs, catastrophizing and

coping

in

the

functioning

of

patients

with

temporomandibular disorders. Pain 92: 41-51.

Von Korff, M., & Simon, G. 1996. The relationship between pain

and depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 30: 101-108.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

[Rathi & Rastogi] Meaning in life & psychological well being in pre adolescents & adolescents

Caplan (2003) Preference for online social interaction A theory of problematic Internet use ans psy

04 Emotions and well being across cultures

25 Natural Ways to Relieve Headaches A Mind Body Approach to Health and Well Being by Romy Fox

The Effects of Performance Monitoring on Emotional Labor and Well Being in Call Centers

Work motivation, organisational identification, and well being in call centre work

Working conditions, well being, and job related attitudes among call centre agents

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Chronic Pain for Dummies

Moberg Spiritual Well Being Questionnaire

Neurobiology and Psychotherapy 12

22 The climate of Polish Lands as viewed by chroniclers, writers and scientists

Baudrillard, Critical Theory And Psychoanalysis

Methapor and Psychoterapy

Chronic Pain Syndromes After Ischemic Stroke PRoFESS Trial

Toward a Psychology of Being Abraham Maslow

Baudrillard, Jean Critical Theory And Psychoanalysis

więcej podobnych podstron