The Relations of Gender and Personality Traits on Different Creativities:

A Dual-Process Theory Account

Wei-Lun Lin

Fo Guang University

Kung-Yu Hsu

National Chung Cheng University

Hsueh-Chih Chen

National Taiwan Normal University

Jenn-Wu Wang

Fo Guang University

In the present study we examine the ways in which gender and personality traits are related to divergent

thinking and insight problem solving. According to the dual-process theory account of creativity, we

propose that gender and personality traits might influence the ease and choice of the processing mode

and, hence, affect 2 creativity measures in different ways. Over 300 participants’ responses on the

Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults (Chen, 2006), HEXACO Personality Inventory (Ashton & Lee,

2009; Lee & Ashton, 2004), Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (Yu, 1993), and performance while

conducting insight-problem tasks, are collected. The results show that Openness was positively correlated

with divergent thinking performance, whereas Emotionality was negatively correlated with insight

problem-solving performance. Women performed better on divergent thinking tests, whereas men’s

capabilities were superior on insight problem tasks. Furthermore, Openness exhibited a mediating effect

on the relationships between gender and divergent thinking. The relationships among gender, personality,

and creative performance, as well as the implications of these findings on cultural differences and

real-field creativity, are discussed.

Keywords: HEXACO, personality trait, gender, divergent thinking, insight problem-solving

Creativity is closely related to human development and achieve-

ment at the individual or societal level. Researchers have investi-

gated creativity from several aspects (e.g., the 4P model, or the

Person, the Product, the Process, and the Press; Mooney, 1963;

Rhodes, 1961). Various measures are used to differentiate high

from low creative abilities. When considering people’s creative

potentials, divergent thinking is the main focus of the “psycho-

metric approach,” and creative problem solving (e.g., insight prob-

lem solving) is extensively investigated in the “cognitive ap-

proach” (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999; Sternberg, Lubart, Kaufman,

& Pretz, 2005). Both are representative indexes that were widely

applied. Nevertheless, theories and accumulating evidence have

shown that these two measures of creativity might involve two

distinct processes (Perkins, 1998; Sternberg et al., 2005; Wake-

field, 1989). These two processes are correlated with different

cognitive factors (Lin, 2006; Lin, Hsu, Chen, & Chang, 2011; Lin

& Lien, 2011). Further, individuals’ performances on the two

measures are not correlated (Lin, Lien, & Jen, 2005). In the present

study we investigate how personality traits, as well as gender,

correlate differently with divergent thinking and creative problem-

solving abilities in accordance with the dual-process theory ac-

count of creativity (Lin & Lien, 2011). In the following para-

graphs, we briefly review the distinction between these two types

of creativity measures. Our predictions about the ways they relate

to individuals’ personality traits and gender, based on the dual-

process theory account of creativity, are then proposed.

Distinction Between Divergent Thinking and Creative

Problem Solving

The concept of divergent thinking refers to the ability to gener-

ate diverse and numerous responses to a given question that

increases the likely output of creative ideas (Guilford, 1956). It

serves as the theoretical basis for many creativity tests (Guilford,

1963; Torrance, 1966; Wallach & Kogan, 1965) in the psycho-

metric approach for creativity (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999; Stern-

berg et al., 2005). For example, the examinee is asked to list as

many as possible interesting and unusual uses for a brick in

accordance with the Unusual Uses Test (Guildford, 1956). Four

main indexes are then applied to assess responses and reflect

divergent thinking ability: (1) The fluency index refers to the

This article was published Online First December 12, 2011.

Wei-Lun Lin and Jenn-Wu Wang, Department of Psychology, Fo Guang

University, Yilan County, Taiwan; Kung-Yu Hsu, Department of Psychol-

ogy, National Chung Cheng University, Chiayi County, Taiwan; Hsueh-

Chih Chen, Department of Educational Psychology and Counseling, Na-

tional Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan.

This research was supported partially by a grant to Wei-Lun Lin from

National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 97–2410 –H– 431– 014). The

work was also supported by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, under the

Aiming for the Top University Plan at National Taiwan Normal University.

We thank James Kaufman and other anonymous reviewers for their ex-

tremely helpful comments.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Kung-Yu

Hsu, Department of Psychology, National Chung Cheng University, Tai-

wan, No. 168, University Road, Minhsiung Township, Chiayi County

62102, Taiwan. E-mail: kungyu@ntu.edu.tw

Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts

© 2011 American Psychological Association

2012, Vol. 6, No. 2, 112–123

1931-3896/11/$12.00

DOI: 10.1037/a0026241

112

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

ability to generate many responses; (2) the flexibility index refers

to the ability to switch categories between responses; (3) the

originality index refers to the ability to generate rarely seen re-

sponses according to the norm; and (4) the elaboration index is

specifically used with respect to a figural question that refers to the

degree of elaboration that is achieved by adding detailed decora-

tions.

On the other hand, the tradition of investigating creative

problem-solving ability in the cognitive approach traces back to

studies about insight problems by Gestalt psychologists. Problem

solvers usually encounter obstacles at first, then later invent a

sudden “a-ha!” solution (Dominowski, 1995; Ohlsson, 1984; Wal-

las, 1926). For example, in a situation in which participants were

required to attach a candle to a wall by using the only objects that

were available, they usually encountered obstacles (functional

fixedness of the tack box as a container, not a candlestick) and

could not successfully solve the problem (i.e., the candle problem;

Duncker, 1945). This type of problem is considered a “productive

problem” and requires more creativity than a “reproductive prob-

lem” (such as algebraic problems) because it cannot be solved by

the existing rules. Instead, a reconstruction of the problem repre-

sentation is required to achieve success (Weisberg, 1995). The

number of correctly solved insight problems is usually used as an

index of creative ability in this approach.

Wakefield (1989) differentiated problem types along ill- versus

well-defined and open- versus closed-solution dimensions. A di-

vergent thinking task is described as a well-defined, open-solution

problem, whereas an insight problem is considered as an ill-

defined, closed-solution one. With respect to the essential proper-

ties of creativity (i.e., novelty and appropriateness; Mayer, 1999),

an open-solution, divergent thinking question better emphasizes

the novelty aspect of creativity (e.g., numerating the uses of a brick

without considering whether they are practical. Only the number

and unusualness of the responses are scored). In contrast, an

insight or creative problem with a specific solution goal (e.g.,

successfully attaching a candle to a wall) demands ideas that are

novel as well as appropriate, which are consistent with the problem

constraints (e.g., using only objects available; Lin & Lien, 2011;

Lin et al., 2005).

Empirical evidence indicates that individuals’ performance on

the two tasks did not correlate with each other (e.g., Lin et al.,

2005), as well as that various cognitive factors correlated differ-

ently to these two measures. For example, intelligence is found to

exhibit moderate positive correlations with creative problem solv-

ing, but it correlates with divergent thinking to a lesser extent

(Sternberg et al., 2005). Similarly, working memory capacity is

found to be positively correlated with insight problem solving, but

not with divergent-thinking performance (Lin & Lien, 2011).

Individuals with better divergent thinking performance are found

to exhibit lower cognitive inhibition ability (as measured by a

retrieval-induced-forgetting paradigm, Anderson, Bjork, & Bjork,

1994) than controls, whereas individuals with better insight

problem-solving performance do not (Lin, 2006). In addition, the

aspects of the breadth of attention are found to exhibit different

roles in divergent thinking and insight problem solving (Lin et al.,

2011).

Lin and Lien (2011) suggested that these results reflected dif-

ferent processes that might involve in divergent thinking and

creative problem solving with respect to the framework of dual-

process theories of cognition (J. St. B. T. Evans, 2003, 2007;

Sloman, 1996; Stanovich & West, 2000). Dual-process theories

have been proposed to account for individuals’ cognitive process-

ing on wide-ranging cognitive functions, including learning and

memory, reasoning, decision making, and judgment (J. St. B. T.

Evans, 2008). These theories assume that people possess two

alternative process systems under one cognitive function. System

1 (or the heuristic system) processes information in an associative,

intuitive, and effortless manner without capacity limits. It is evo-

lutionarily early and comprises prior knowledge and experience.

On the other hand, System 2 (or the analytic system) involves

logical and rule-based processes in which execution relies on

cognitive resources. It is considered evolutionarily recent and

permits abstract thinking. For example, in a syllogism task, a

logically correct validity judgment is proposed to be derived from

System 2 processing, whereas a judgment influenced by prior

experiences or beliefs without considering its logical status is

derived from System 1 processing (i.e., the belief-bias effect; J. St.

B. T. Evans, 2003).

Different tasks also might require differential involvement of

both systems (Stanovich, 1999). With respect to these view-

points pertaining to the context of creativity, Lin and Lien

(2011) proposed that idea generation in divergent thinking,

which emphasizes novelty, primarily relies on associative, ef-

fortless System 1 processing. On the other hand, the ability to

generate plausible solutions in creative problem solving reflects

both novelty and appropriateness. It requires System 1 as well

as rule-based, resource-limited System 2 processing.

According to Stanovich (1999), some individual difference vari-

ables could account for the choice of processing mode; for exam-

ple, cognitive style. Cognitive style

1

is a combination of mental

abilities and personality (Guastello, Shissler, Driscoll, & Hyde,

1998). Research also revealed that there were gender differences in

cognitive style (e.g., Sadler-Smith, 2001). Therefore, we hypoth-

esize that personality traits and gender might also influence the

ease and choice of the processing mode. We explored how per-

sonality traits and gender correlate differently with respect to the

differential involvement of System 1 and System 2 processing

during the divergent thinking and insight problem-solving mea-

sures.

1

Zhang and Sternberg (2006) proposed a “mode of thinking” in discus-

sions about the cognitive styles. The three modes of thinking, which

include analytic, holistic, and integrative, are similar conceptions to the

dual-process theory (Stanovich & West, 2000). However, the dual-process

theory (System 1 and System 2) focuses on depicting the fundamental

information processing modes and is evident in various cognitive func-

tions. On the other hand, cognitive style represents a higher level concep-

tion, a combination of mental abilities and personality, or the ways in

which people prefer to use their abilities (Guastello et al., 1998). Besides,

there are various concepts or taxonomies of cognitive styles (Zhang &

Sternberg, 2009). As Stanovich and West (2000) pointed out, the dual-

process theory depicted computational capacity at the algorithmic level of

analysis, whereas cognitive or thinking styles indexed individual differ-

ences at the intentional level of analysis. Both contributed independently to

the variances of individual differences in performance on various cognitive

tasks (Stanovich & West, 1998). Further, the two conceptions are different

in malleability that might be affected by long- or short-term practice

(Baron, 1985).

113

GENDER, PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CREATIVENESS

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

The Relationships Between Personality Traits and

Creativity

Several personality traits have been identified as being related to

creativity. At the surface trait level, creative individuals are found to

be more reserved, dominant, serious, inattentive to rules, sensitive,

and self-sufficient (Guastello, 2009; Runco, 2007). At the source trait

2

level, studies based on the five-factor model (McCrae & Costa, 2008)

consistently find positive relationships between Extraversion, Open-

ness to Experience, and creativity (Batey, Chamorro-Premuzic, &

Furnham, 2010; Batey & Furnham, 2006; for the meta-analysis of the

Big Five source traits with creative behavior, see Guastello, 2009).

Conscientiousness is sometimes found to be negatively related to

creativity (Batey et al., 2010; Batey & Furnham, 2006). However,

Feist’s (1998) meta-analysis indicated that although artists were less

conscientious than nonartists, scientists were more conscientious than

nonscientists. Researchers also found that creative individuals possess

some negative traits, such as deviance (Eisenman, 1997) and psy-

choticism (Eysenck, 1995). Although the results are fruitful, some

paradoxical personalities existed. As Csikszentmihalyi (1996) pointed

out in his interviews with highly successful individuals, these inter-

viewees seemed to be both logical and naı¨ve, disciplined yet playful,

introverted and extraverted, realistic but imaginative, objective but

passionate, and feminine and masculine.

The above results were usually derived from studying eminent

people in various domains or assessing normal people’s creative

potentials using certain measurements. As mentioned above, al-

though different personality traits have been linked to scientific

and artistic creativity (other artists’ traits included norm doubting,

nonconformity, independence, hostility, and lack of warmth, and

traits of scientists were dominance, arrogance, and high self-

confidence; Feist, 1999), studies that investigated normal people

mostly utilized divergent thinking tests to differentiate high from

low creative people. The differences of personality traits between

people with high and low creative problem-solving potentials seem

to have been less extensively investigated.

Given that the two measures of divergent thinking and creative

problem solving exhibit different properties and involve different

processes, their relationships with different personality traits merit

clarification. For example, Neuroticism or Emotionality, a con-

struct in the five-factor model, is found closely related to mental

pathology (Matthews, Deary, & Whiteman, 2003). It might hinder

System 2 processing in which an objective, rational, and rule-

based process is required that underlies creative problem solving.

However, it might not necessarily hinder associative, intuitive

System 1 processing that divergent thinking mainly requires. Some

evidence gave support to this speculation. For example, research

has found that Psychoticism (Eysenck, 1995) or mood disorders

(Nowakowska, Strong, Santosa, Wang, & Ketter, 2005) were

correlated with divergent thinking performance, whereas positive

and stable emotions facilitated insight problem-solving abilities

(G. Kaufmann, 2003). On the other hand, Openness to Experience

might especially facilitate System 1 processing (and hence diver-

gent thinking performance) when the richness of ideas, but not

necessarily appropriateness, could effortlessly be associated. Pre-

vious research did find that Openness to Experience and divergent

thinking were closely related (Batey & Furnham, 2006; Batey et

al., 2010). It is still questionable whether Openness to Experience

helps to generate novel and appropriate ideas that could fulfill the

constraints of solving goals in creative problem solving.

The present study utilizes the HEXACO Personality Inventory

(Ashton & Lee, 2009; Lee & Ashton, 2004), which is considered

more generalizable and inclusive than the five-factor model. Hon-

esty/Humility, Emotionality, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Consci-

entiousness, and Openness to Experience are assessed to determine

the different relationships between personality traits and the two

creativity measures.

The Relationships Between Gender and Creativity

Inconsistent results of gender differences in creativity have been

obtained in the past (J. C. Kaufman, 2006). Some studies showed that

no differences existed (e.g., P. C. Cheung, Lau, Chan, & Wu, 2004),

but other studies found that women performed better on the divergent

thinking tests than men (Dudek, Strobel, & Runco, 1993; Kim &

Michael, 1995; Kuhn & Holling, 2009). Few studies have investigated

gender differences in creative problem solving. However, some re-

search has found that women possessed a more intuitive cognitive

style, whereas men were found to be more sensational (Sadler-Smith,

2001). Further, women were determined to be more interested in

people, while men were more attracted by objects (Baron-Cohen,

2003; Connellan, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Batki, & Ahluwalia,

2000). Some researchers thus proposed that women preferred holistic,

intuitive thinking and relied more on System 1 processing, whereas

men were good at analytic thinking and System 2 processing (Wang,

2011). According to the dual-process theory account of creativity (Lin

& Lien, 2011), divergent thinking mainly relies on System 1 process-

ing, while creative problem solving also requires System 2 process-

ing. It is hypothesized that women could perform better on divergent

thinking tests, as previously findings have shown, whereas men could

be more adept at solving creative or insight problems.

In the following experiment, we use a divergent thinking test

(Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults [ATTA]; Chen, 2006), an

insight problem task (one of the representative creative problems),

the HEXACO–PI–R (Revised HEXACO Personality Inventory,

Lee & Ashton, 2004), as well as Raven’s Advanced Progressive

Matrices (APM; Yu, 1993; a test for general intelligence

3

), to

investigate the relationships between personality traits, gender, and

2

The surface traits refer to personality traits that are the most specific

and proximally related to external behaviors. The source traits refer to

personality traits that are the results of factor-analysis on numerous per-

sonality tests (Guastello, 2009). The present study examined the relation-

ships between creativity and the source traits (HEXACO) because the

source traits, which were more basic, were thought to contain surface-level

traits. We also could provide exploratory data of the Taiwanese sample and

compare it with past findings on the relationship between the Big Five and

creativity in different cultures.

3

According to the reviews of Sternberg and colleagues (2005), the

relationships between intelligence and divergent thinking were more con-

sistent with the threshold theory. It stated that intelligence and creativity

are correlated up to an IQ of 120, and the relationship dissolves for higher

IQs. However, the relationships between intelligence and creative problem

solving are consistently correlated even for higher IQs. Besides, our

participants were recruited from five universities and were possibly diverse

in intelligence. Thus, we collected intelligence scores in the present study

as a controlled variable. We also inspected its different roles on divergent

thinking and creative problem solving.

114

LIN, HSU, CHEN, AND WANG

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

the two creativity measures (i.e., divergent thinking and insight

problem solving). Different relationships between personality

traits and gender with different creativity measures are expected.

In addition, previous studies have inspected the relationships

between personality and creativity, as well as the connection

between gender and creativity (as described in the previous re-

views, these analyses were often with a single creativity measure,

divergent thinking) and the relationships between personality and

gender (e.g., Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae, 2001; Schmitt, Realo,

Voracek, & Allik, 2008). To our knowledge, there are no studies

about how personality and gender interact or mediate each other to

contribute to creative behavior. The moderation and mediation

effects of personality and gender on divergent thinking and insight

problem-solving performance also are explored in the present

study.

Method

Participants and General Procedure

A total of 320 undergraduate students from five universities in

Taiwan participated in this study (57.8% women; M age

⫽ 19.45

years, SD

⫽ 1.89). The collection of different university students

prevents homogeneity and enables greater variance of our data.

Each participant provided informed consent and participated in

some or all subtests (i.e., insight problem task and HEXACO: n

⫽

284; ATTA: n

⫽ 301; APM: n ⫽ 291)

4

in consecutive 2-week

anonymous group testing sessions that were 1-hr in duration. All

participants received a gift and were debriefed when they finished

all of the tasks.

Instruments and Procedures

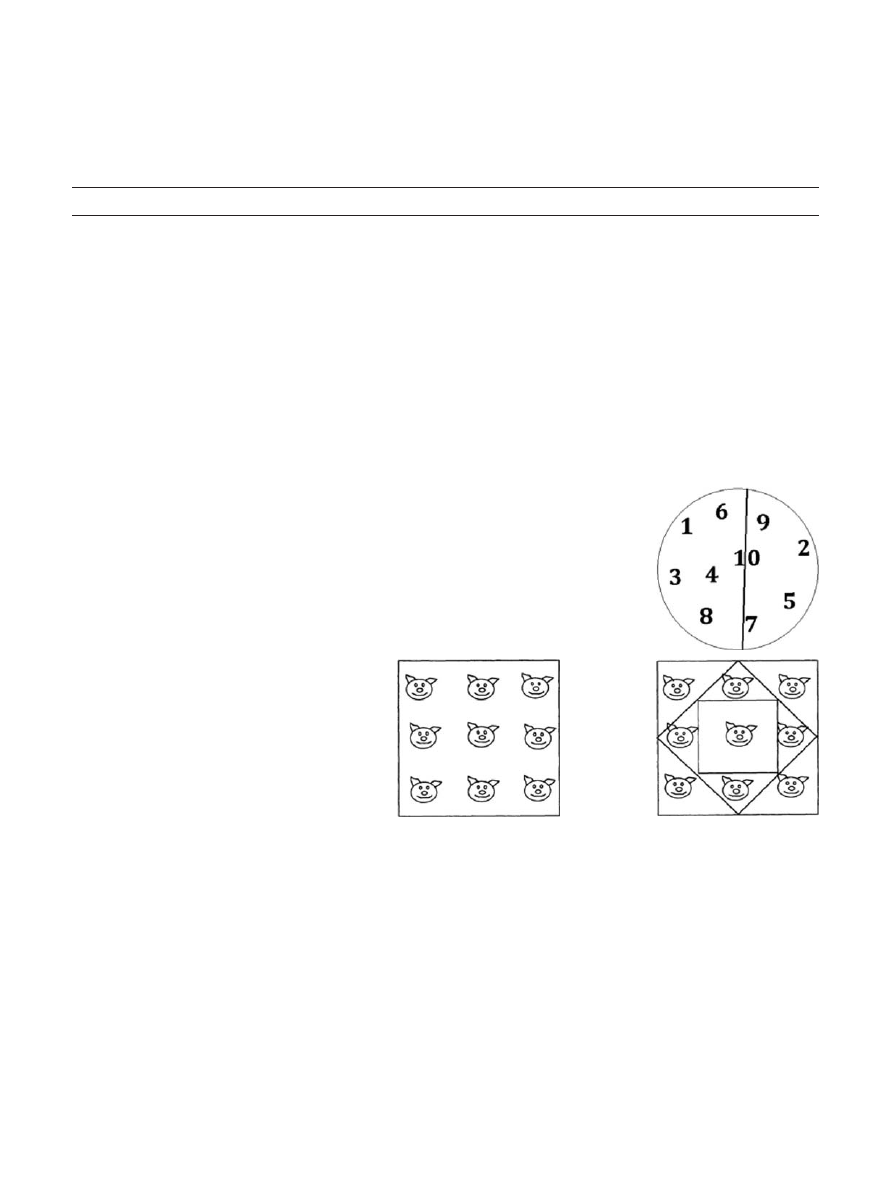

Creative problem-solving measure—Insight problem task.

Eighteen insight problems (nine verbal and nine figural) were first

selected from an insight-problems inventory Web site at Indiana

University (http://www.indiana.edu/

⬃bobweb/d4.html). The in-

clusion of these problems fulfilled the criterion of “pure” insight

problems that necessarily require a reconstructing process, as

suggested by Weisberg (1995). A pretest (n

⫽ 52) on these 18

problems was then conducted. According to the results of the

pretest, we chose five verbal problems and five figural problems

with moderate difficulty levels (i.e., ranging from 25% to 70% for

verbal problems and 21.6% to 62.7% for figural problems). The 10

insight problem task for this study can be found in the Appendix.

The proceedings of the verbal and figural problems were coun-

terbalanced between participants. Participants were given 20 min

to complete the task. At the end, they were required to report

whether they had previously seen and/or known the answers to any

of the problems. The performance scores were calculated as the

percentage of unfamiliar problems that were answered correctly

within the verbal, figural, and 10 total insight problems. The

participants’ average accuracy rates on the verbal, figural, and total

problems were 38% (SD

⫽ .29), 43% (SD ⫽ .28), and 40% (SD ⫽

.25). The correlation of accuracy rates between verbal and figural

problems was .55, p

⬍ .01. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were

.54, .51, .68 for the scores on the verbal, figural, and whole

problems, respectively.

Divergent thinking measure—Abbreviated ATTA.

The

Chinese version of the ATTA (Chen, 2006) is a translated version

of ATTA (Goff & Torrance, 2002). It includes three subtests: a

verbal test (question enumeration) and two figural tests (figural

completion). Three minutes is allowed for each subtest. The test,

which was developed as a large-sample norm in Taiwan for

undergraduate students, established satisfactory reliability and va-

lidity results (Chen, 2006).

Participants’ responses were scored by two independent raters

for fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration, which are

among the most representative indexes for divergent thinking

abilities. The interrater reliability coefficients for these four kinds

of scores ranged from .83 to .97. The fluency scores were simply

the total number of responses generated by each participant. The

flexibility scores represented the number of different categories of

responses. The originality scores represented the sum of scores on

each response in comparison to the norm and scored as either 0 or

1. The elaboration scores of the figural subtests were scored as the

number of elaborated decorations in each response.

Participants’ performance on the ATTA was scored as follows:

fluency: M

⫽ 12.11, SD ⫽ 4.01; flexibility: M ⫽ 7.87, SD ⫽ 2.69;

originality: M

⫽ 3.22, SD ⫽ 2.42; elaboration: M ⫽ 5.36, SD ⫽

4.31. The scores for these indexes were mostly significantly cor-

related with those of each of the others (the Pearson’s r ranged

from .31 to .83, p

⬍ .01); however, originality and elaboration

exhibited no correlation (r

⫽ .07, p ⫽ .24).

Personality measure—HEXACO–PI–R.

The HEXACO–

PI–R (Ashton & Lee, 2009; Lee & Ashton, 2004) measures six

personality traits: Honesty/Humility, Emotionality, Extraversion,

Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience.

These six personality traits came from the factor analysis results of

personality lexicons of six different languages. As previously

mentioned, the inventory was considered to be more generalizable

and inclusive than the five-factor model. There are 16 items for

each personality trait, and a 5-response Likert scale is used from 1

(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This inventory was

translated into the Chinese version by one of the authors. Two

Chinese personality psychologists who were trained in the United

States and the United Kingdom examined the quality of this

translation. The Chinese version of this inventory then was trans-

lated into English. The back-translation version of this inventory

was checked by authors of this inventory and the incorrect trans-

lations were modified. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, which

ranged from .74 to .82, were obtained for the scores on these six

scales of the Chinese version in this study. The different types of

measurement equivalence (i.e., configural, metric, and error vari-

ance) of the HEXACO–PI–R were found in a multiple age group

ranging from early adolescence to adulthood by the use of confir-

matory factor analysis (Hsu, 2010).

General ability measure—APM.

The Chinese version of

APM (Yu, 1993) was administered to assess participants’ general

intelligence. In this test, every test item consists of the presenta-

tions of several graphs, including an empty one. Participants have

to find the relationships between them by choosing the most

4

The participants were also assessed with the Adult Temperament

Questionnaire (D. E. Evans & Rothbart, 2007). The results are reported in

another paper.

115

GENDER, PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CREATIVENESS

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

reasonable graph to accompany the empty one from among the

eight graphs. The test has established stable reliability and validity

results: The retest reliability was .91 (Fould, Forbes, & Bevans,

1962), and the correlations between the APM scores and intelli-

gence tests were high (e.g., rs

⫽ .4 to .6, Schweizer & Moosbrug-

ger, 2004).

For a proper time control, we excluded the first 12 items, which

were found to add little to the discriminative power of the test

(Bors & Stokes, 1998), and used Items 13 to 36. The total admin-

istrating time was 25 min. The performance scores were calculated

as the total number of items correct. Our participants’ scores

ranged from 0 to 23, with Ms

⫽ 12.45, SD ⫽ 5.16.

Results

The Relationships Between the Two Measures of

Creativity and General Intelligence

We first examined the relationships between participants’ per-

formances on divergent thinking and insight problem solving. As

shown in Table 1, although fluency and flexibility scores exhibited

small positive correlations with verbal, figural, and total insight

problem-solving accuracy (rs

⫽ .19, .22, .24; rs ⫽ .23, .24, .26,

p

⬍ .01, respectively), the indexes of originality and elaboration

were not correlated with insight problem-solving performance

(rs

⫽ .01 to .11, ns). Because the correlations between the four

indexes of divergent thinking and the two indexes of insight

problem solving were high, we partialed out the effects of other

indexes within one task. The extent of correlations was smaller

between fluency, flexibility, and insight problem-solving perfor-

mance (rs ranged from .12 to .19, p

⬍ .05). These results indicate

that individuals’ performances on the two creativity measures were

only slightly related on some of the indexes.

The correlations between the participants’ creative performance

and APM scores, referred to as their general intelligence and

representing their cognitive abilities, were also computed. As

Table 1 shows, participants’ divergent thinking performance—

fluency, flexibility, and elaboration—were positively correlated

with their APM scores (rs

⫽ .21, .23, .20, respectively, small effect

sizes as defined by Cohen, 1988; p

⬍ .01). There was no corre-

lation between intelligence scores and the originality index (r

⫽

.01, ns). On the other hand, participants’ APM scores were more

highly correlated to their insight problem-solving performance,

with rs

⫽ .39, .43, and .46, p ⬍ .01, to verbal, figural, and total

problem-solving accuracy, respectively. All of these coefficients

achieved a medium level of effect sizes, as defined by Cohen

(1988). These results fit well with previous findings that creative

problem-solving ability depended more on intelligence than did

the divergent thinking performance (Sternberg et al., 2005).

The Relationships Between Two Creativity Measures

and Personality Traits

One of the main purposes of the present study was to inspect

how personality traits correlated differently with divergent think-

ing and creative problem-solving performance. As Table 2 shows,

Openness to Experience was positively correlated to divergent

thinking indexes (rs

⫽ .24, .22, .24, .19, p ⬍ .01, for fluency,

flexibility, originality, and elaboration indexes, respectively). Ex-

traversion was also positively correlated to most of the divergent

thinking indexes (rs

⫽ .14, .13, .16, p ⬍ .05, for fluency, flexi-

bility, and elaboration indexes, respectively, but not to the origi-

nality index, r

⫽ .10, ns). Nevertheless, neither Openness to

Experience or Extraversion exhibited correlations with most of the

participants’ insight problem-solving performance (rs ranged from

.00 to .09, ns, except the verbal insight problem-solving perfor-

mance exhibited a weak positive correlation with Openness to

Experience, r

⫽ .13, p ⬍ .05). On the other hand, Emotionality

was found to be negatively correlated to insight problem-solving

performance (rs

⫽ ⫺.16, ⫺.13, ⫺.17, p ⬍ .01, for verbal, figural,

and total insight problem-solving accuracy, respectively), but not

to divergent thinking performance (rs ranged from .01 to .08, ns;

even emotionality and elaboration index were positively corre-

lated, r

⫽ .12, p ⬍ .05). Honesty, Agreeableness, and Conscien-

tiousness were not correlated to either divergent thinking or

insight problem-solving performance. The above results

showed a pattern as predicted: Divergent thinking performances

related positively to Openness to Experience and Extraversion,

whereas insight problem-solving performances were hindered

by Emotionality.

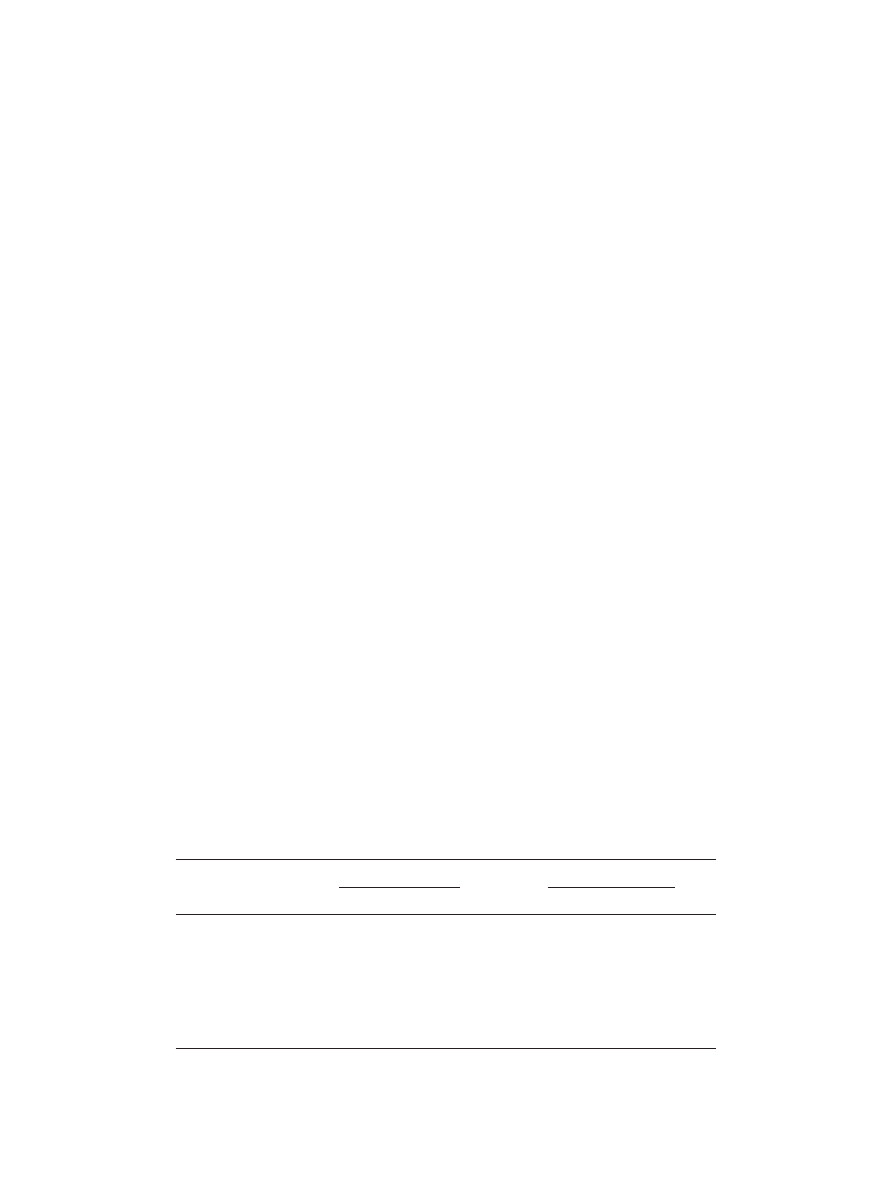

Table 1

The Relationships Between Creativity Measures and Intelligence

Creativity

measures

Fluency

Divergent thinking

Elaboration

Insight problem

APM

Flexibility

Originality

Verbal

Figural

Total

Divergent thinking

Fluency

—

.83

ⴱⴱ

.35

ⴱⴱ

.31

ⴱⴱ

.19

ⴱⴱ

.22

ⴱⴱ

.24

ⴱⴱ

.21

ⴱⴱ

Flexibility

—

.37

ⴱⴱ

.35

ⴱⴱ

.23

ⴱⴱ

.24

ⴱⴱ

.26

ⴱⴱ

.23

ⴱⴱ

Originality

—

.07

.08

.11

.11

.01

Elaboration

—

.01

.09

.06

.20

ⴱⴱ

Insight problem

Verbal

—

.55

ⴱⴱ

.88

ⴱⴱ

.39

ⴱⴱ

Figural

—

.88

ⴱⴱ

.43

ⴱⴱ

Total

—

.46

ⴱⴱ

Note.

APM was used to measure participants’ intelligence. APM

⫽ Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices.

ⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .01.

116

LIN, HSU, CHEN, AND WANG

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

The Relationships Between Two Creativity Measures

and Gender

Another purpose of the present study was to inspect how gender

correlated differently to the two creativity measures. We separately

analyzed the performance of our female (n

⫽ 181 for ATTA and

n

⫽ 169 for insight problem task) and male (n ⫽ 118 for ATTA

and n

⫽ 111 for insight problem task) participants on the ATTA

and insight problem task. The results, which are shown in Table 3,

indicate that our male participants performed better on most of the

insight problem-solving indexes than their female counterparts:

.48

⫾ .28 versus .40 ⫾ .28, t(282) ⫽ 2.57, p ⬍ .05, d

5

⫽ .31, for

the verbal accuracy; and .45

⫾ .26 versus .37 ⫾ .24, t(282) ⫽ 2.45,

p

⬍ .05, d ⫽ .30, for the total accuracy. Except for the figural

accuracy, only marginally significant effect of gender existed,

.41

⫾ .30 vs. .35 ⫾ .28, t(282) ⫽ 1.7, p ⫽ .09. On the contrary,

female participants performed better in most of the divergent

thinking indexes over male participants: 12.48

⫾ 4.0 versus

11.53

⫾ 4.19, t(297) ⫽ ⫺1.97, p ⫽ .05, d ⫽ .23, for fluency;

8.15

⫾ 2.59 versus 7.42 ⫾ 2.80, t(297) ⫽ ⫺2.29, p ⬍ .05, d ⫽ .27,

for flexibility; and 6.04

⫾ 4.43 versus 4.33 ⫾ 3.94, t(297) ⫽

⫺3.41, p ⬍ .01, d ⫽ .40, for elaboration. The exception was that

female participants did not perform better on the originality index

than male counterparts: 3.36

⫾ 2.31 vs. 2.98 ⫾ 2.58, t(297) ⫽

⫺1.33, ns. These results indicate the different gender effects on

divergent thinking and insight problem-solving performance and

support our prediction.

The Relationships Between Personality Traits, Gender,

and Two Creativity Measures

To understand how gender and personality traits contribute to

the performance of divergent thinking and insight problem solving,

several hierarchical multiple-regression analyses were conducted.

In all of these analyses, the steps of the variables that entered the

equations were as follows: (1) APM (where intelligence scores

could be controlled), (2) gender, (3) Honesty-Humility, Extraver-

sion, Emotionality, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Open-

ness to Experience. All of the personality variables in the final step

were entered simultaneously.

As Table 4 shows, the APM score accounted for 4 to 18% of

variance of two creativity indexes,

⌬F(1, 318) ⫽ 11.91 to 67.65,

p

⬍ .001, except for the originality index of divergent thinking.

When the gender variable was entered into the equation (Model 2),

the amount of variance explained in both creativity measures

(

⌬R

2

⫽ .01 to .04, p ⬍ .05) significantly increased from Model 1,

in which only the APM scores was included,

⌬F(1, 317) ⫽ 3.91 to

12.51, p

⬍ .05. When personality variables were further included

in Model 3, the amount of variance explained (

⌬R

2

⫽ .05, for all

the above three indexes, p

⬍ .01) in divergent thinking perfor-

mance increased further,

⌬F(6, 311) ⫽ 3.10 to 3.15, p ⬍ .01, but

not in the insight problem-solving performance.

When intelligence, gender, and personality were included as

predictors (Model 3), APM scores could predict significantly both

creative performances (with

s ⫽ .34 to .41 for insight problem-

solving, p

⬍ .001, and s ⫽ .20 to .21 for divergent thinking, p ⬍

.001, except originality). The predictive powers were larger for the

insight problem-solving consideration. Gender significantly pre-

dicted some of the indexes of both creative performances, but in an

opposite direction. For insight problem solving,

s ⫽ ⫺.14 (p ⬍

.01) and

⫺.12 (p ⬍ .01) for verbal and total accuracy. On the other

hand,

⫽ .16 (p ⬍ .01) for the elaboration index on divergent

thinking.

As for the predictive powers of personality traits on creativity

measures, Openness to Experience could significantly predict all

of the four indexes of divergent thinking (with

s ⫽ .19, .18, .20,

.15, p

⬍ .05, for fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration

indexes, respectively). Nevertheless, it could only predict one

index, verbal accuracy, of insight performance (with

⫽ .13, p ⬍

.01). In addition, Extraversion could only predict elaboration

scores in divergent thinking (

⫽ .13, p ⬍ .05).

The above results indicate that, after controlling the effects of

intelligence on two creativity performances, our male and female

participants performed better at different creativity tasks (i.e., insight

problem solving and divergent thinking), respectively. As for the roles

5

The effect size, d, is computed according to the formula: d

⫽ t[(1/

n

1

)

⫹(1/n

2

)]

.5

(Cortina & Nouri, 2000), where t refers to the statistical value

of t test, n

1

and n

2

refer to the numbers of female and male participants.

This formula is used for an unequal cell condition.

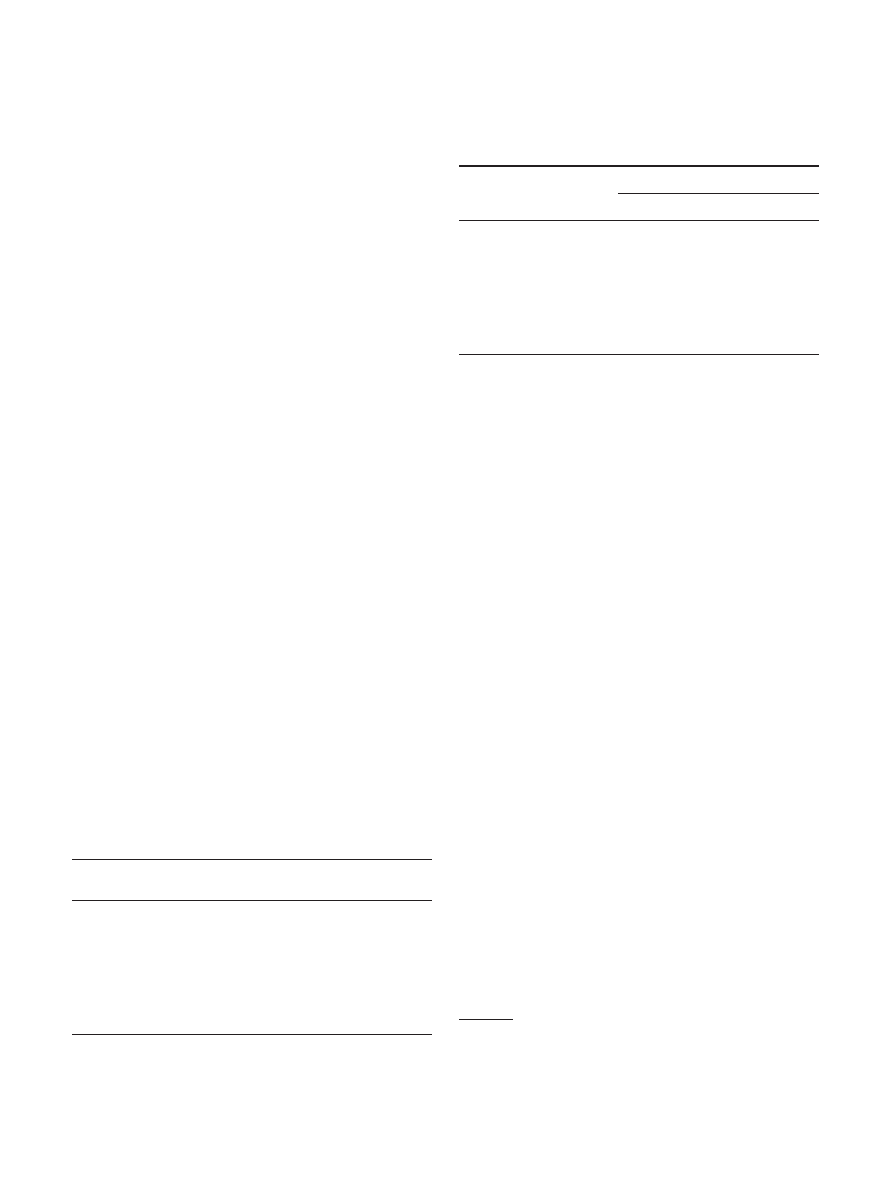

Table 2

The Relationships Between Creativity Measures and Personality

Traits

Creativity

measures

H

E

X

A

C

O

Divergent thinking

Fluency

⫺.02

.01

.14

ⴱ

.05

.06

.24

ⴱⴱ

Flexibility

.03

.08

.13

ⴱ

⫺.03

.03

.22

ⴱⴱ

Originality

.04

.01

.10

.05

.02

.24

ⴱⴱ

Elaboration

⫺.02

.12

ⴱ

.16

ⴱ

⫺.03

⫺.02

.19

ⴱⴱ

Insight problem

Verbal

⫺.03

⫺.16

ⴱⴱ

.00

.07

.01

.13

ⴱ

Figural

⫺.07

⫺.13

ⴱ

.05

.09

.05

.03

Total

⫺.05

⫺.17

ⴱⴱ

.03

.10

.03

.09

Note.

H

⫽ Honesty-Humility; E ⫽ Emotionality; X ⫽ Extraversion; A ⫽

Agreeableness; C

⫽ Conscientiousness; O ⫽ Openness to Experience.

ⴱ

p

⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .01.

Table 3

Means and Standard Deviations of Two Creativity Measures

Between Male and Female Participants

Creativity

measures

Participants

Male

Female

Divergent thinking

Fluency

11.53 (4.2)

12.48

ⴱ

(4.0)

Flexibility

7.42 (2.8)

8.15

ⴱ

(2.6)

Originality

2.98 (2.6)

3.36 (2.3)

Elaboration

4.33 (3.9)

6.04

ⴱⴱ

(4.4)

Insight problem

Verbal

0.48 (0.28)

0.40

ⴱ

(0.28)

Figural

0.41 (0.30)

0.35 (0.28)

Total

0.45 (0.26)

0.37

ⴱ

(0.24)

Note.

Standard deviations are in parentheses.

ⴱ

p

⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .01.

117

GENDER, PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CREATIVENESS

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

of personality traits, the regression results were more complex, al-

though most of the patterns were preserved as in the correlation

analysis (see Table 2). Personality also seemed to exhibit a lesser

effect on insight problem solving than divergent thinking.

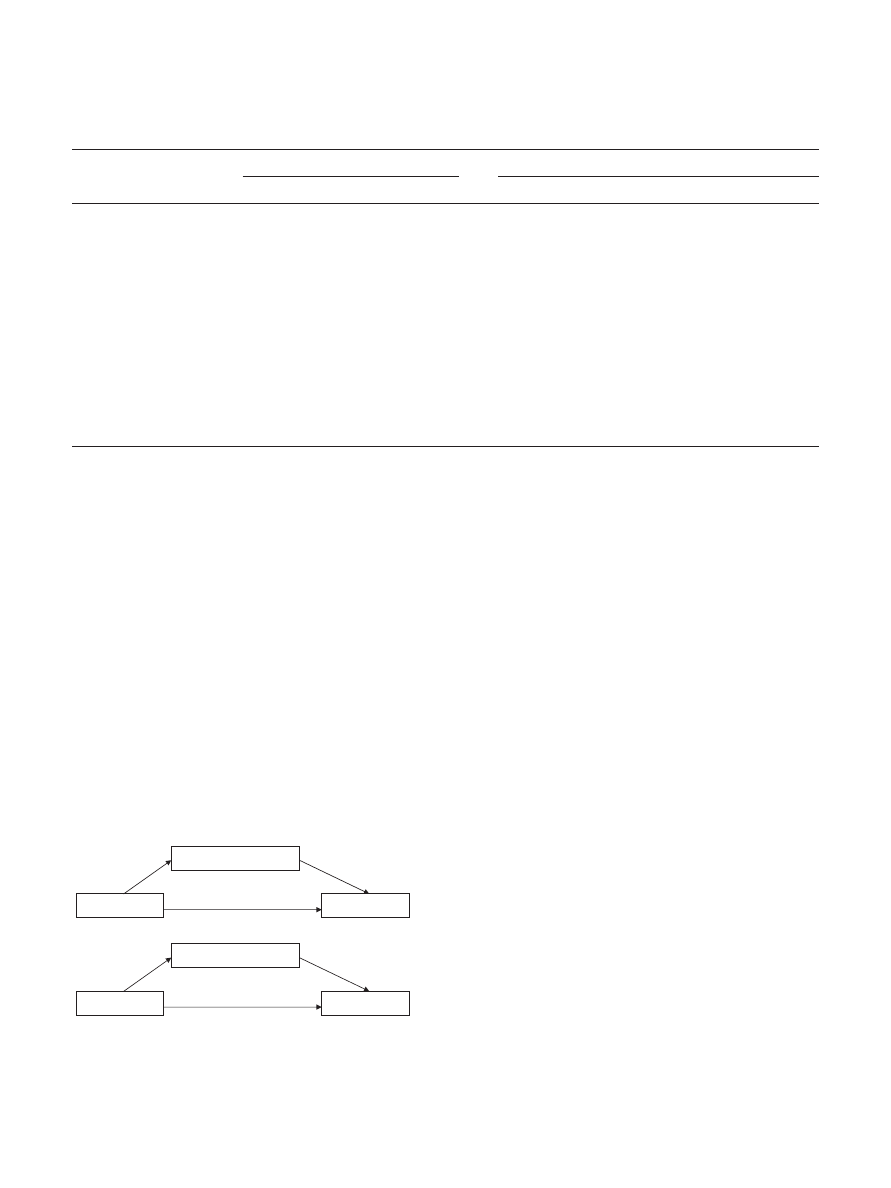

Inspecting Table 4, it was found that, compared to Model 2, the

predictive powers of gender were diminished when the personality

variables were entered into the regression analysis in Model 3 for

the indexes of fluency and flexibility. These results revealed that

the mediation effects of personality traits (especially Openness to

Experience) could be found. The mediation analyses were further

conducted to investigate whether different gender predicted differ-

ent creative performances through personality traits. The results

revealed (see Figure 1A) that the initial associations between

gender and fluency scores were eliminated by the inclusion of

Openness to Experience, indicating a full mediation effect (Sobel

z value

⫽ 2.05, p ⬍ .05). The associations between gender and

flexibility scores were also attenuated by the mediation of Open-

ness (see Figure 1B), to a marginally significant degree (Sobel z

value

⫽ 1.74, p ⫽ .08). Other analyses did not show any signif-

icant mediation effects of personality on the relationships between

gender and creative performances.

In addition, we examined whether gender and personality variables

interacted on the two creative performances. Therefore, Model 4 was

constructed and Gender

⫻ Personality variables were entered as

predictors. The results showed no significant moderation effects.

Discussion

The present study specifies and examines how personality traits

and gender are related to different creativity measures: divergent

thinking and insight problem solving. These two creativity mea-

sures are investigated and applied extensively but independently

by the psychometric and cognitive approach in creativity research

literature. Our results mainly showed that different personality

traits in the HEXACO–PI–R were related to different creativity

measures. Our male and female participants performed differently

in the two creativity measures. Interesting findings were also

obtained when considering the relationships between gender, per-

sonality traits, and creativity. The more detailed discussions of

these findings are stated as follows.

As our data showed (see Table 2), Openness to Experience and

Extraversion correlated significantly to most of the participants’

divergent thinking performances. These results replicated the pre-

vious findings in which these two personality traits were identified

as being important in creativity, when only the divergent thinking

sort of measurement was used (Batey & Furnham, 2006; Batey et

al., 2010). However, Openness to Experience and Extraversion

were not so related to close-ended, insight problem solving when

we took this measurement into consideration. Instead, individuals

who performed better on insight problem solving possessed less

Emotionality, as our data showed a negative correlation between

Emotionality and insight problem-solving performance.

Table 4

Intelligence, Gender, and Personality Traits as Predictors of the Two Creativity Measures

Predictors in model

Insight problem

Divergent thinking

Verbal

Picture

Total

Fluency

Flexibility

Originality

Elaboration

Model 1

APM

.350

ⴱⴱⴱ

.389

ⴱⴱⴱ

.419

ⴱⴱⴱ

.195

ⴱⴱⴱ

.205

ⴱⴱⴱ

.013

.190

ⴱⴱⴱ

⌬R

2

.123

ⴱⴱⴱ

.151

ⴱⴱⴱ

.175

ⴱⴱⴱ

.038

ⴱⴱⴱ

.042

ⴱⴱⴱ

.000

.036

ⴱⴱⴱ

Model 2

APM

.352

ⴱⴱⴱ

.390

ⴱⴱⴱ

.420

ⴱⴱⴱ

.193

ⴱⴱⴱ

.204

ⴱⴱⴱ

.013

.188

ⴱⴱⴱ

Gender

⫺.150

ⴱⴱ

⫺.102

ⴱ

⫺.144

ⴱⴱ

.111

ⴱ

.129

ⴱⴱ

.077

.191

ⴱⴱⴱ

⌬R

2

.023

ⴱⴱ

.010

ⴱ

.021

ⴱⴱ

.012

ⴱ

.017

ⴱⴱ

.006

.037

ⴱⴱⴱ

Model 3

APM

.342

ⴱⴱⴱ

.389

ⴱⴱⴱ

.413

ⴱⴱⴱ

.197

ⴱⴱⴱ

.213

ⴱⴱⴱ

.009

.197

ⴱⴱⴱ

Gender

⫺.141

ⴱⴱ

⫺.069

⫺.121

ⴱⴱ

.096

†

.092

.043

.157

ⴱⴱ

Honesty

⫺.028

⫺.062

⫺.051

⫺.026

.039

.036

⫺.004

Emotionality

⫺.091

⫺.081

⫺.096†

.011

.065

.024

.094

Extraversion

⫺.019

.044

.014

.083

.108†

.053

.128

ⴱ

Agreeableness

.003

.037

.028

⫺.009

⫺.073

.003

⫺.049

Conscientiousness

.029

.072

.051

.050

.025

⫺.013

⫺.027

Openness to Experience

.127

ⴱ

⫺.006

.069

.187

ⴱⴱⴱ

.175

ⴱⴱⴱ

.204

ⴱⴱⴱ

.149

ⴱⴱ

⌬R

2

.028

.019

.023

.054

ⴱⴱ

.053

ⴱⴱ

.048

ⴱⴱ

.053

ⴱⴱ

Note.

APM was used to measure participants’ intelligence; Gender: Male 0, Female 1.

†

p

⬍ .10.

ⴱ

p

⬍ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .01.

ⴱⴱⴱ

p

⬍ .001.

A

B

Gender

Openness to Experience

Fluency

β = .09 (.11*)

β = .12 *

β = .21 *** (.24***)

Gender

Openness to Experience

Flexibility

β = .11 (.12*)

β = .12 *

β = .18 *** (.22**)

Figure 1.

The mediation effects of personality trait (Openness to Expe-

rience) on the relationships between gender and the fluency (A), flexibility

(B) index of divergent thinking.

ⴱ

p

⫽ .05.

ⴱⴱ

p

⫽ .01.

ⴱⴱⴱ

p

⫽ .001.

118

LIN, HSU, CHEN, AND WANG

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

An interesting finding in the regression analysis (see Table 4)

revealed that Openness to Experience also significantly predicted

verbal insight problem-solving performance even after intelligence

and gender were controlled. Given that Openness to Experience is

assumed to be related to the richness of ideas an individual holds

and processes (Batey et al., 2010), one possible explanation is that

some less dominant concepts (but that are keys to the correct

answers) that lie in the descriptions of our particular verbal insight

problems were equally and properly processed as the dominant

concepts by individuals with a high level of Openness to Experi-

ence; hence, the likelihood of correct solutions increased. The role

of Openness to Experience on insight problem solving still needs

further investigation with different problems as measures.

Turning to the role of gender, our data showed a pattern of disso-

ciation between gender and different creativity measures (see Table

3). Although women performed better on most of the indexes of

divergent thinking test, which was also demonstrated by previous

studies (Dudek et al., 1993; Kim & Michael, 1995; Kuhn & Holling,

2009), our data first showed that men were better at an insight

problem-solving task. When inspecting the relationships between

gender, personality traits, and creativity, our results showed that the

predictive powers of gender generally decreased when personality

variables were included in the regression analyses, especially for

divergent thinking indexes (see Table 4). Although the moderation

effects of gender and personality were not significant, the mediation

analyses showed some interesting findings. Women performed better

on divergent thinking tasks and are more open to experience than men

(additional analysis that we performed showed a significant correla-

tion between gender and Openness to Experience, r

⫽ .12, p ⬍ .05).

The significant mediation effects of Openness to Experience on the

relationships between gender and divergent thinking indexes (fluency,

in particular) indicated that women possessed a higher level of Open-

ness to Experience, which further enhanced their fluency in divergent

thinking.

There was no significant mediation effect of personality on the

relationships between gender and insight problem-solving perfor-

mance, although analysis showed that gender and Emotionality

were significantly correlated (r

⫽ .21, p ⬍ .01). In addition, Table

4 also showed that the amount of variance explained in insight

problem-solving performance did not increase when personality

variables were further included in the regression analysis. These

results indicate that gender did not predict insight problem-solving

performance through Emotionality and personality traits played

smaller roles on insight problem solving. Instead, insight problem-

solving performance was mainly predicted by intelligence (APM)

and gender differences. Although the regression weights that were

obtained, as shown in Table 4, were rather low, the present study

may provide an exploratory direction. The ways in which gender

and personality interact to influence different creativity measures

remain an interesting issue that merits further exploration.

As previously mentioned, Lin and Lien (2011) proposed a dual-

process account of creativity to explore the differential involvement of

Systems 1 and 2 processing in divergent thinking and creative prob-

lem solving. In respect to this theory, the present study hypothesizes

that different gender and personality traits might influence the ease

and choice of the processing mode and, hence, affect divergent

thinking or creative problem solving differently on either side (as we

used insight problems as one kind of creative problems). Our results

support this theory. First, the participants’ performances on the two

measures were only slightly correlated, indicating different processes

that the two measures might possibly involve. Second, although

women have been suggested to be prone to holistic, intuitive, and

System 1 thinking, and men have been suggested to be dominated by

analytic and System 2 thinking (Wang, 2011), our results showed that

female and male participants performed better at divergent thinking

and insight problem solving, respectively. Third, Emotionality, which

was hypothesized to hinder analytical, System 2 processing with its

high level, was found to be negatively related to insight problem-

solving performance. Openness to Experience, which might espe-

cially facilitate associative, System 1 processing, was found to be

positively related to divergent thinking performance. These results

support the notions of dual-process account of creativity (Lin & Lien,

2011) in that the idea generation in divergent thinking mainly relies on

associative, intuitive, and effortless System 1 processing. However,

generating plausible solutions in creative problem solving additionally

requires rule-based, analytical, and resource-limited System 2 pro-

cessing.

Another interesting issue that requires further discussion is how

culture may have played a role in our study on the relationships

between gender, personality, and creativities. Our data was collected

in Taiwan, but some researchers pointed out that gender differences in

creativity (divergent thinking performance, in particular) could be best

expected in Western cultures (e.g., Kuhn & Holling, 2009). As men-

tioned, P. C. Cheung and colleagues (2004) found no gender differ-

ences in the fluency index in a Hong Kong sample. Our results

showed that Taiwanese women performed better in divergent thinking

than men, consistent with the findings in Western culture (Dudek et

al., 1993; Kuhn & Holling, 2009) as well as Kim and Michaels’

(2005) finding on a significant gender difference in creativity in a

Korean sample. In addition, although creativity could be hindered by

the social structure of the collectivism culture (Runco, 2007) and

Openness to Experience could be not encouraged in Chinese society

(McCrae, Yik, Trapnell, Bond, & Paulhus, 1998), we found that

Openness to Experience and Extraversion were positively related to

divergent thinking. As F. M. Cheung and colleagues (2008) argued,

the construct of openness in Chinese culture should incorporate the

idea- or interest-related cognitive styles in Western culture with in-

terpersonal potency and Extraversion in the collective culture. Our

measures of Openness to Experience and Extraversion could capture

the part of the Chinese notion of Openness to Experience. Our results

also imply that, even in a detrimental context (e.g., collectivism

culture) for creativity, the personal dispositions could enhance one’s

creativity.

Although many factors may contribute to the real-life achievement

of creativity, creativity potentials or abilities (such as divergent think-

ing and creative problem solving) were considered the essential com-

ponents of this achievement (Eysenck, 1995; Sternberg et al., 2005).

The present study that focuses on individuals’ creative potentials

might provide some implications for real-world creativity. A scientist

discovers the principles of the world according to phenomena and

evidence, whereas an artist creates works of art without constraining

the work to concrete explanations of objectives (Simonton, 2008;

Stent, 2001). Creative problem solving, with its closed-ended prop-

erty, could be closer to the scientific discovery processes, whereas

divergent thinking tasks might characterize more artistic processes by

their open-ended nature (Lin & Lien, 2011). Previous work has

identified some different personality traits that belong to artists and

scientists (Feist, 1999). Our study suggests that Emotionality and

119

GENDER, PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CREATIVENESS

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Openness to Experience might be other traits that could differentiate

them with a possible theoretical base (i.e., the dual-process account of

creativity, Lin & Lien, 2011). Our study also gives support to and a

possible explanation concerning the observations that women are

more interested in social and artistic events, whereas men are more

interested in scientific activities (Betz & Fitzgerald, 1987). Further,

men are better than women at scientific studies (Ceci, Williams, &

Barnett, 2009; Martin, Mullis, Gonzalez, & Chrostowski, 2004).

If factors are found to be correlated differently with divergent

thinking and creative problem solving, they might be used to

differentiate individuals with distinct potentials and design for

various training programs that are applied to improve different

creative achievements.

References

Anderson, M. C., Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1994). Remembering can

cause forgetting: Retrieval dynamics in long-term memory. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 1063–

1087. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.20.5.1063

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO– 60: A short measure of

the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment,

91, 340 –345. doi: 10.1080/00223890902935878

Baron, J. (1985). Rationality and intelligence. Cambridge, England: Cam-

bridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511571275

Baron-Cohen, S. (2003). The essential difference: The truth about the male

and female brain. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Batey, M., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Individual

differences in ideational behavior: Can the Big Five and psychometric

intelligence predict creativity scores? Creativity Research Journal, 22,

90 –97. doi: 10.1080/10400410903579627

Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2006). Creativity, intelligence and personality:

A critical review of the scattered literature. Genetic, Social, and General

Psychology

Monographs,

132,

355– 429.

doi:

10.3200/

MONO.132.4.355-430

Betz, N. E., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1987). The career psychology of women.

Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Bors, D. A., & Stokes, T. L. (1998). Raven’s Advanced Progressive

Matrices: Norms for first-year university students and the development

of a short form. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58, 382–

398. doi: 10.1177/0013164498058003002

Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s under-

representation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations.

Psychological Bulletin, 135, 218 –261. doi: 10.1037/a0014412

Chen, C.-Y. (2006). The Chinese version of Abbreviated Torrance Test for

Adults. Taipei, Taiwan: Psychological Publishing.

Cheung, F. M., Cheung, S. F., Zhang, J., Leung, K., Leong, F., & Yeh,

K. H. (2008). Relevance of openness as a personality dimension in

Chinese culture: Aspects of its cultural relevance. Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, 39, 81–108. doi: 10.1177/0022022107311968

Cheung, P. C., Lau, S., Chan, D. W., & Wu, W. Y. H. (2004). Creative

potential of school children in Hong Kong: Norms of the Wallach-

Kogan Creativity Tests and their implications. Creativity Research Jour-

nal, 16, 69 –78. doi: 10.1207/s15326934crj1601_7

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences

(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Connellan, J., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Batki, A., & Ahluwalia, J.

(2000). Sex differences in human neonatal social perception. Infant Behavior &

Development, 23, 113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00032-1

Cortina, J. M., & Nouri, H. (2000). Effect size for ANOVA designs.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Costa, P. T., Jr., Terracciano, A., & McCrae, R. R. (2001). Gender

differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising

findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 322–331.

doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of

discovery and invention. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Dominowski, R. L. (1995). Productive problem solving. In S. M. Smith,

T. B. Ward, & R. A. Finke (Eds.), The creative cognition approach (pp.

73–96). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dudek, S. Z., Strobel, M. G., & Runco, M. A. (1993). Cumulative and

proximal influences on the social environment and children’s creative

potential. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154, 487– 499. doi: 10.1080/

00221325.1993.9914747

Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving (L. S. Lees, Trans.). Psycholog-

ical Monographs, 68(Whole No. 270).

Eisenman, R. (1997). Creativity, preference for complexity, and physical and

mental health. In M. A. Runco & R. Richards (Eds.), Eminent creativity,

everyday creativity, and health (pp. 99 –106). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Evans, D. E., & Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Developing a model for adult

temperament. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 868 – 888. doi:

10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2003). In two minds: Dual-process accounts of rea-

soning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 454 – 459. doi: 10.1016/

j.tics.2003.08.012

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2007). Hypothetical thinking: Dual processes in

reasoning and judgment. Hove, England: Psychology Press.

Evans, J. St. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judg-

ment and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278.

doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity. New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511752247

Feist, G. J. (1998). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic

creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 290 –309. doi:

10.1207/s15327957pspr0204_5

Feist, G. J. (1999). The influence of personality on artistic and scientific

creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 273–

296). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Gilhooly, K. J., & Murphy, P. (2005). Differentiating insight from non-

insight problems. Thinking and Reasoning, 11, 279 –302. doi: 10.1080/

13546780442000187

Goff, K., & Torrance, E. P. (2002). Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults

manual. Bensenville, IL: Scholastic Testing Service.

Guastello, S. J. (2009). Creativity and personality. In T. Rickards, M. A.

Runco, & S. Moger (Eds.), Routledge companion to creativity (pp.

256 –266). Abington, England: Routledge.

Guastello, S. J., Shissler, J., Driscoll, J., & Hyde, T. (1998). Are some

cognitive styles more creatively productive than others? Journal of

Creative Behavior, 32, 77–91.

Guilford, J. P. (1956). The structure of intellect. Psychological Bulletin, 53,

267–293. doi: 10.1037/h0040755

Guilford, J. P. (1963). Potentiality for creativity and its measurement. In

E. F. Gardner (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1962 invitational conference on

testing problems (pp. 31–39). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Ser-

vice.

Guilford, J. P. (1967). The nature of human intelligence. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

Hsu, K.-Y. (2010). The age differences of personality traits on HEXACO–

PI–R from early adolescence to adulthood. Unpublished manuscript,

Fo-Guang University, Ilan, Taiwan.

Kaufman, J. C. (2006). Self-reported differences in creativity by ethnicity

and gender. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20, 1065–1082. doi:

10.1002/acp.1255

Kaufmann, G. (2003). Expanding the mood-creativity equation. Creativity

Research Journal, 15, 131–135.

Kim, J., & Michael, W. B. (1995). The relationship of creativity measures

to school achievement and to preferred learning and thinking style in a

120

LIN, HSU, CHEN, AND WANG

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

sample of Korean high school students. Educational and Psychological

Measurement, 55, 60 –74. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055001006

Kuhn, J.-T., & Holling, H. (2009). Measurement invariance of divergent

thinking across gender, age, and school forms. European Journal of

Psychological Assessment, 25, 1–7. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.1

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO

Personality Inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 329–358.

doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8

Lin, W.-L. (2006). The relationships of cognitive inhibition, working

memory capacity, and different creativity tasks. (Unpublished doctorial

dissertation). National Taiwan University, Taipei City, Taiwan.

Lin, W.-L., Hsu, K.-Y., Chen, H.-C., & Chang, W.-Y. (2011). Different

attentions, different creativities: A trait approach. Manuscript submitted

for publication.

Lin, W.-L., & Lien, Y.-W. (2011). The different role of working memory in

divergent thinking and creative problem solving: A dual-process theory

account. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Lin, W.-L., Lien, Y.-W., & Jen, C.-H. (2005). Is the more the better? The

role of divergent thinking in creative problem solving (Chinese). Chi-

nese Journal of Psychology, 47, 211–227.

Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., Gonzalez, E. J., & Chrostowski, S. J.

(2004). TIMSS 2003 international science report: Findings from IEA’s

repeat of the third international mathematics and science study at the

eighth grade. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study

Center, Boston College.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2003). Personality traits.

Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (1999). Fifty years of creativity research. In R. J. Sternberg

(Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 449–460). New York, NY: Cambridge

University Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. Jr. (2008). The five factor model of

personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.),

Handbook of Personality. New York: Guilford Press.

McCrae, R. R., Yik, M. S. M., Trapnell, P. D., Bond, M. H., & Paulhus,

D. L. (1998). Interpreting personality profiles across cultures: Bilingual,

acculturation, and peer rating studies of Chinese undergraduates. Jour-

nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1041–1055. doi: 10.1037/

0022-3514.74.4.1041

Mooney, R. L. (1963). A conceptual model for integrating four approaches

to the identification of creative talent. In C. W. Taylor & F. Barron

(Eds.), Scientific creativity: Its recognition and development (pp. 331–

340). New York, NY: Wiley.

Nowakowska, C., Strong, C. M., Santosa, C. M., Wang, P. W., & Ketter, T. A.

(2005). Temperamental commonalities and differences in euthymic mood dis-

order patients, creative controls, and healthy controls. Journal of Affective

Disorder, 85, 207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.11.012

Ohlsson, S. (1984). Restructuring revisited II: An information processing

theory of restructuring and insight. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology,

25, 117–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1984.tb01005.x

Perkins, D. N. (1998). In the country of the blind and appreciation of

Donald Campbell’s vision of creative thought. Journal of Creative

Behavior, 32, 177–191.

Rhodes, M. (1961). An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappa, 42,

305–310.

Runco, M. A. (2007). Creativity: Theories and themes: Research, devel-

opment and practice. London, England: Elsevier Academic Press.

Sadler-Smith, E. (2001). The relationship between learning style and

cognitive style. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 609 – 616.

doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00059-3

Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a

man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality

traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

94, 168 –182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168

Schweizer, K., & Moosbrugger, H. (2004). Attention and working memory

as predictors of intelligence. Intelligence, 32, 329 –347. doi: 10.1016/

j.intell.2004.06.006

Simonton, D. K. (2008). Creativity and genius. In O. P. John, R. W.

Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and

research (pp. 679 –700). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sloman, S. A. (1996). The empirical case for two systems of reasoning.

Psychological Bulletin, 119, 3–22. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.3

Stanovich, K. E. (1999). Who is rational? Studies of individual differences

in reasoning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (1998). Individual differences in rational

thought. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 127, 161–188.

doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.127.2.161

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Individual differences in reasoning:

Implications for the rationality debate. The Behavioral and Brain Sci-

ence, 23, 645–726. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00003435

Stent, G. S. (2001). Meaning in art and science. In K. H. Pfenninger &

V. R. Shubik (Eds.), The origins of creativity (pp. 31– 42). Oxford,

England: Oxford University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Pros-

pects and paradigms. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity

(pp. 3–15). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., Lubart, T. I., Kaufman, J. C., & Pretz, J. E. (2005).

Creativity. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge

handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 351–369). New York, NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Torrance, E. P. (1966). Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking: Norms-

technical manual. Princeton, NJ: Personnel Press.

Wakefield, J. F. (1989). Creativity and cognition some implications for arts

education. Creativity Research Journal, 2, 51– 63. doi: 10.1080/

10400418909534300

Wallach, M. A., & Kogan, N. (1965). Modes of thinking in young children:

A study of the creativity and intelligence distinction. New York, NY:

Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich.

Wang, J.-W. (2011). Gender differences in the development of implicit and

explicit scientific thinking. Unpublished manuscript, Fo-Guang Univer-

sity, Ilan, Taiwan.

Weisberg, R. W. (1995). Case studies of creative thinking: Reproduction

versus restructuring in the real world. In S. M. Smith, T. B. Ward, &

R. A. Finke (Eds.), The creative cognition approach (pp. 53–72). Cam-

bridge, MA: MIT Press.

Yu, S.-J. (1993). The Chinese version of Raven’s Progressive Matrices

Test. Taipei, Taiwan: Chinese Behavioral Science.

Zhang, L.-F., & Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The nature of intellectual styles.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Zhang, L.-F., & Sternberg, R. J. (2009). Intellectual styles and creativity.

In T. Rickards, M. A. Runco, & S. Moger (Eds.), Routledge companion

to creativity (pp. 256 –266). Abington, England: Routledge.

(Appendix follows)

121

GENDER, PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CREATIVENESS

This

document

is

copyrighted

by

the

American

Psychological

Association

or

one

of

its

allied

publishers.

This

article

is

intended

solely

for

the

personal

use

of

the

individual

user

and

is

not

to

be

disseminated

broadly.

Appendix A

Ten Insight Problems and Solutions Used

Problems

Solutions

1. Earth problem

Still 6 sextillion (the concrete

and stone were already part

of the earth when it was

weighed)

It is estimated that the earth weighs 6 sextillion tons. How much more would the earth weigh

if 1 sextillion tons of concrete and stone were used to build a wall?

2. Hole problem

Zero (there is no dirt in a hole)

How many cubic centimeters of dirt are in a hole 6 meters long, 2 meters wide, and one meter

deep?

3. Cabin problem

The match

Erin stumbles across an abandoned cabin one cold, dark and snowy night. Inside the cabin are

a kerosene lantern, a candle, and wood in a fireplace. She only has one match. What should

she light first?

4. Magician problem

He threw it up in the air