==================================

T

A

B

&

### 44

{

..

ö ö

e

#

ön ö ö ö ö ööö

ö ö ö

e

#

ö ö

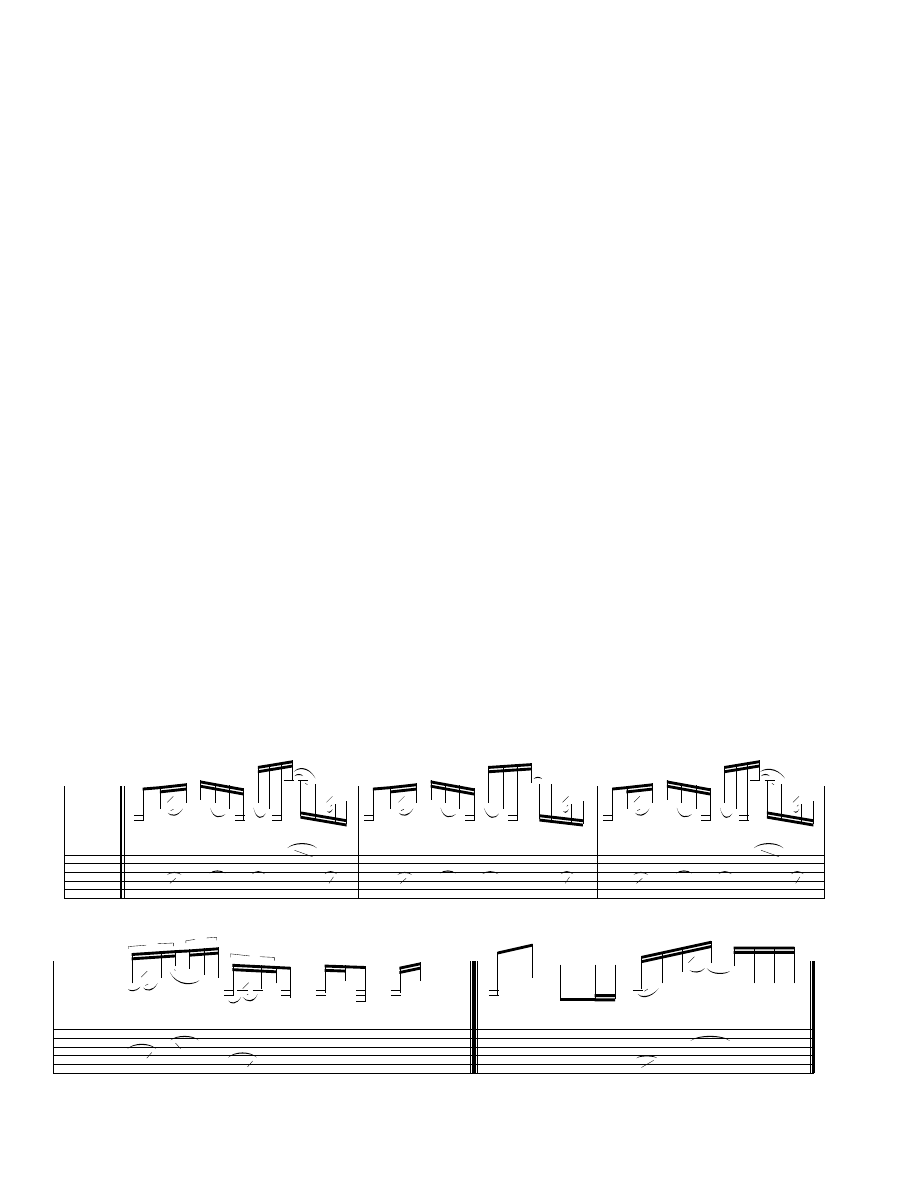

Open A Tuning: EAEAC E

E

C

A

E

A

E

#

0

0

2

3

0

0

0

3 3

0

0

5

3

2

3

0

ö ö

e

#

ön ö ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö ö ö

e

#

ö ö

0

0

2

3

0

0

0

3 3

0

0

3

2

3

0

3

ö ö

e

#

ön ö ö ö ö ööö

ö ö ö

e

#

ö ö

0

0

2

3

0

0

0

3 3

0

0

5

3

2

3

0

#

n

n

n

w/ slide

“The only way you can get good—unless you’re a genius—is to copy.” — R i t c h i e Bl a c k m o re, Ju l y / Au g . ’ 7 3 G P

1 2 4

GUITAR PLAYER OCTOBER 1999

B Y J E F F M c E R L A I N

==================================

T

A

B

&

###

E

C

A

E

A

E

#

ö

e

#

ön ö ön ö ö

ö

e

ön ö ön À À ö

3

3

3

À À

ä

{

..

0

2

3

5

3

0

3

0

2

3

0

3

X

X

2

X

X

{

..

ö

ööön ööö ööö ööö

ön öb

öb

e

öb ö öö

ö

ööö ööö {

..

(

)

4x

0

3

3

2

3

3

2

3

3

2

3

3

2

3

6

6

5 5

(6) 5

6

6

5

6

6

5

6

6

B R

2

w/out slide

1

3

1

2

2

3

1

1

3

2

Chris Whitley’s

Twisted Blues

“DAYS OF OBLIGATION”

is a hidden track on songwriter

and slide guitarist Chris Whitley’s

critically acclaimed CD,

Din of

Ecstasy. [To learn more about

Chris Whitley and his approach

to slide, see our May ’95, July ’97,

and July ’98 issues.] According to

Whitley, the quirky blues is a

cross between Bukka White and

Thelonious Monk. “I wrote this

tune very quickly,” he says, “I

wanted something crude, but not

too familiar. I would never have

come up with this kind of a riff if

I didn’t have vocals in mind.

Without vocals, most of my stuff

would bore me.”

Whitley feels his strength lies

in simplicity, though “Days of

Obligation” is hardly simple. I’ve

written out the song’s basic riff

as Whitley showed it to me. If

you listen to the track, you’ll

hear how he weaves variations

on this theme.

F

Fiin

ne

e p

po

oiin

nttss.. The tune has a

percussive, funky sixteenth-note

feel. In the tradition of many old

Delta bluesmen, such as Bukka

White and Son House, the tune

stays mostly on the I7 chord.

Whitley plays the song in open-

A tuning (E, A, E, A, C#, E). Except

for open strings and the low

G and

F# at the end of bar 4, he plays all

the notes in the first four bars with

a slide, which he sports on his 4th

finger. It

t a k e s

practice

to get the

“It’s important

to bring some-

thing of your own

to the party.”

—Jeff McErlain

==================================

T

A

B

&

ö ö ö ö

û

=

3

44 öj öö# öö öö

3

ö ö ö ö

ö ö ö ö

e

#

öö ö ö#ö öö öbö

3

öbö öö ööb öö

e

#

öö ö ö

ö

e

#

öön öJ ä

ö

#

e

öbö öö öö öö# öö öö öbön öö öö

3

3

3

öö

öböö

ööbb

b

ööö

öö

úúú

úú

G7

F7

C7

C7

A 9 G9

b

2

1

1

3

3

3

3

2

2

1

1

3

3 3

2

3

3

3

1

1

2

3

3

3

1

2

5

3

3

4

5

5

6

6

7

7

5

5

5

5

3

3

4

3

3

3

2

1

1

4

4

5

5

3

3

3

3

1

1

2

10

10

10

8

8

9

10

10

11

11

12

11

12

11

12

10

11

10

11

10

11

9

10

9

10

9

10

8

9

11

11

11

11

10

10

10

10

10

9

n

n

1

2

2

1

2

1

2

1

n

nn

3

song’s many hammer-ons and pull-offs

right. Use a light touch—your frets won’t like

it if you drop your slide onto the strings too

hard.

C

Ch

ha

an

ng

ge

e iitt u

up

p.. Whitley draws on Delta

blues from the ’20s and ’30s, but he’s not con-

tent to simply imitate the past greats. The

important lesson here is that with effort, you

can put a new twist on an old tradition.

Whether you’re into blues, jazz, country, R&B,

funk—whatever—it’s important to bring

something of your own to the party. g

A faculty member at National Guitar

Workshop and transcriber for Hal Leonard,

Jeff McErlain has toured Europe and record-

ed three disks with Liquid Hips.

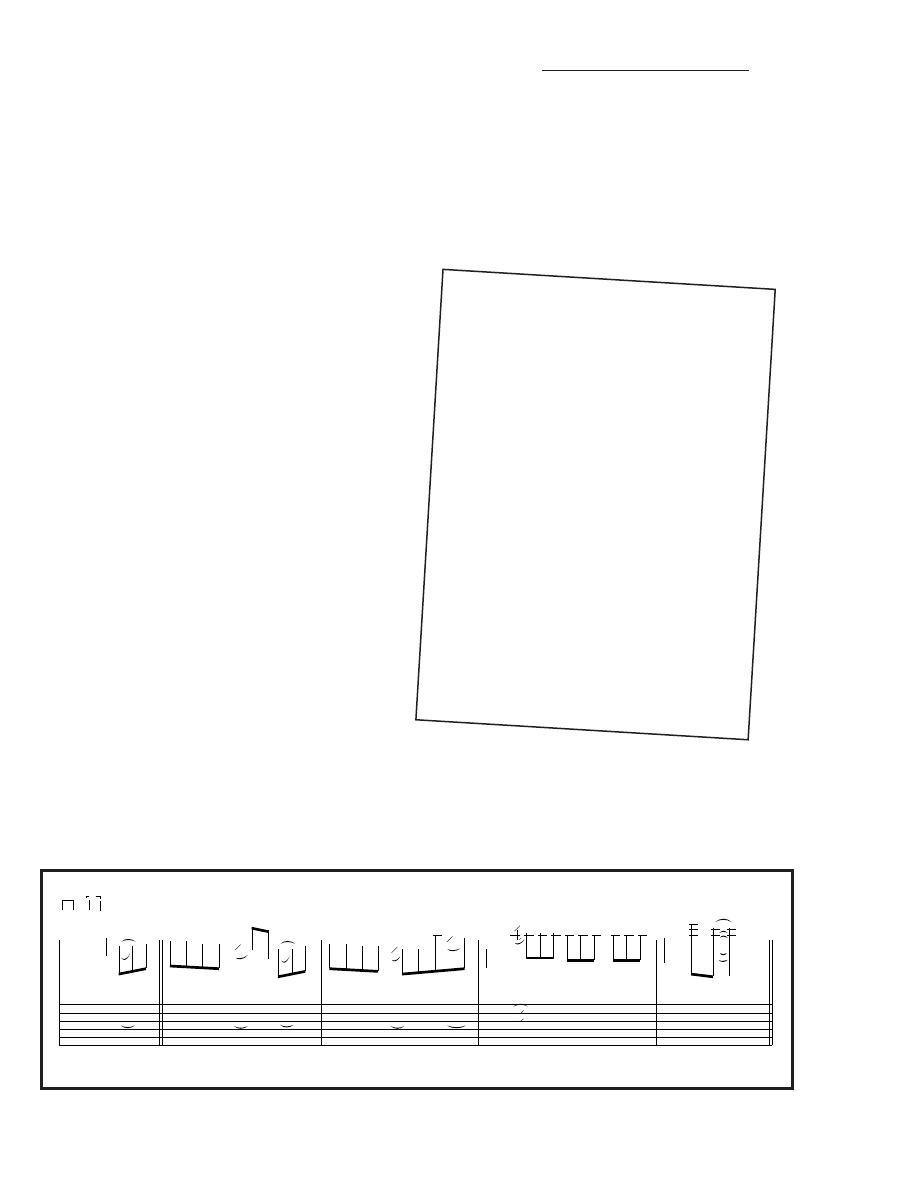

ANYONE SEEKING A

solid foundation in

blues—its progressions,

chord voicings, rhythm pat-

terns, and basic soloing—

will welcome David Ham-

burger’s

Beginning Blues

Guitar [$20.90, from Alfred

Publishing]. This clearly

written book-and-CD pack-

age covers essential funda-

mentals—notes on the neck,

key signatures, intervals, ba-

sic chord construction, and

diatonic harmony—along

with details on major, minor,

and pentatonic scales.

The book comes packed

with musical exercises de-

signed to teach such blues-

approved techniques as ham-

mers, pulls, slides, string

bending, and vibrato. Virtual-

ly every example is some-

thing you can play onstage—

there’s no endless drilling on

pure technique. For example,

when learning how to finger

pull-offs, you’re also learning

classic phrases used by every-

one from T-Bone Walker to

Jimmy Page.

Beginning Blues Guitar

also features some nifty in-

tros and turnarounds, one of

which is shown here. “To cre-

ate an intro,” writes Ham-

burger, “you might take a

particular chord-based riff

and move it through all three

chords of the turnaround,

ending on a descending

turnaround lick.”

This example illustrates

the intro building process by

moving an R&B double-stop

figure through the V7, IV7,

and I7 chords of a

C blues,

and capping the phrase with

a handy turnaround. You can

play this intro with a flatpick

or a hybrid pick-and-fingers

grip. If you opt for the latter,

try using a pick on the fourth

string, and your middle and

ring fingers on the third and

second strings, respectively.

(For a twangy sound, snap

the double-stops by pulling

straight up on the strings

and quickly releasing them.)

As a bonus, Hamburger

offers practicing tips, in-

cluding how to organize

your time, how to use a

metronome or drum ma-

chine, and how to grow from

your mistakes. The compan-

ion CD contains 56 audio

excerpts—plenty to get you

moving around the fret-

board. For those wanting vi-

sual action, Alfred offers a

90-minute

Beginning Blues

Guitar video for $14.95.

—ANDY ELLIS g

B

O

O

K

B

R

O

W

S

I

N

G

B E G I N N I N G B L U E S G U I T A R

www.guitarplayer.com OCTOBER 1999 GUITAR PLAYER

1 2 5

© 1994 Alfred Publishing Co., Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

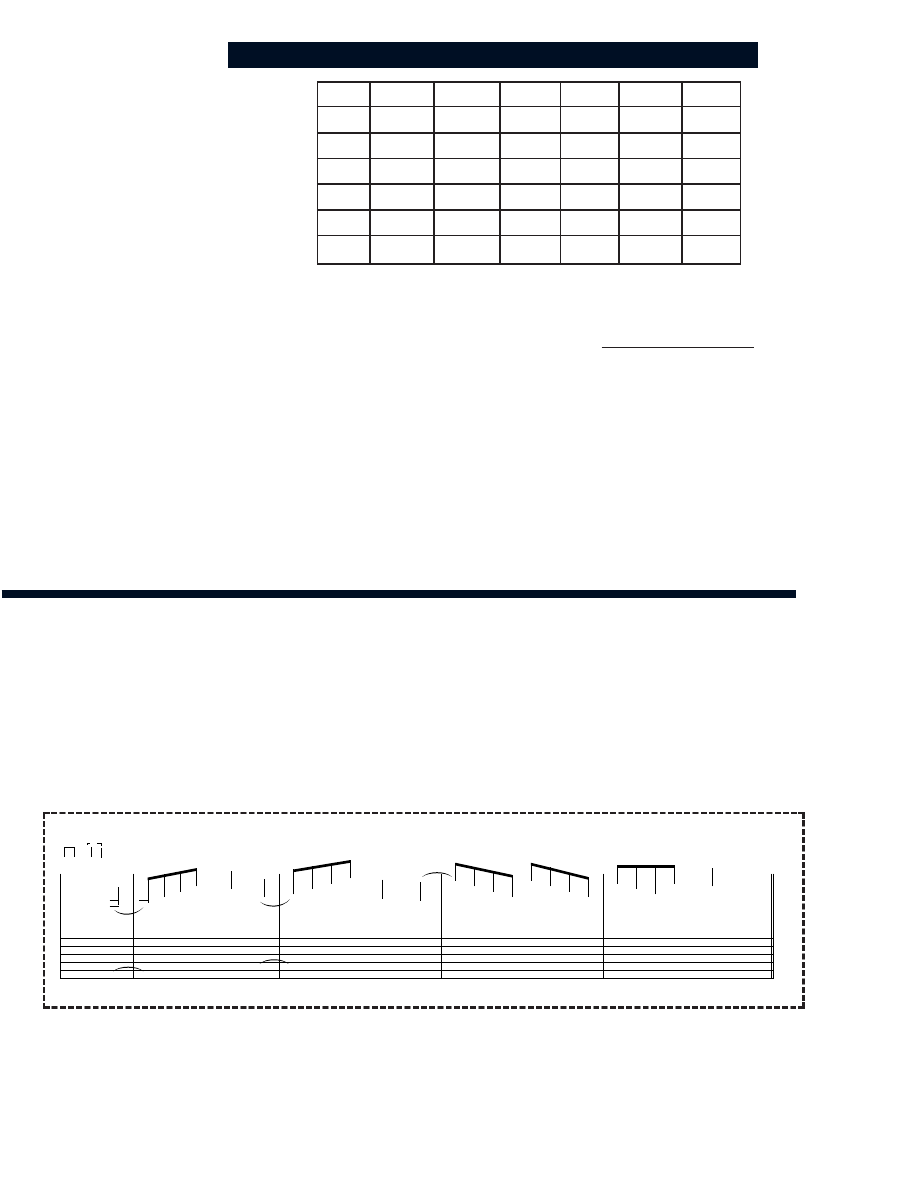

B A C K T R A C K

IN THE PAST MONTHS,

several readers have expressed an

interest in modes: What are they?

How are they constructed? How

do you to use them? We’ll address

the first two questions in this les-

son, and explore applications in

upcoming Back Track install-

ments.

O

Ov

ve

errv

viie

ew

w.. A special kind of

scale, modes play an important

role in melodic improvisation.

Smart soloists learn to associate

modes with common chord types.

Then when they see a certain

chord, these players automatically

have a set of notes from which to

extract a melody. In this scenario,

the melody and rhythm may be

improvised, but the sonic building

blocks have been pre-selected.

There are two ways to look at

modes. Both views use the major

scale as a reference point, and each

view has its advantages.

T

Th

he

e ““ssc

ca

alle

e iin

nv

ve

errssiio

on

n”” v

viie

ew

w..

You can think of a mode as an

in-

version of a major scale. Instead of

starting on the first tone of, say,

C

major, and ascending one octave

through the scale, you start on an-

other tone and ascend an octave.

Check it out:

• Ascending an octave from the

2nd tone of the major scale yields

the Dorian mode.

• Ascending from the 3 yields

Phrygian.

• Ascending from the 4 yields

Lydian.

• Ascending from the 5 yields

Mixolydian.

• Ascending from the 6 yields

Aeolian.

• Ascending from the 7 yields

Locrian.

Even the major scale can be

viewed as a mode—it’s called Ion-

ian. E

Ex

x.. 1

1 shows the seven modes

of the

C major scale: C Ionian, D

Dorian,

E Phrygian, F Lydian, G

Mixolydian,

A Aeolian, and B

Locrian.

T

Th

he

e 7

7--sstte

ep

p p

prro

og

grra

am

m. Every

mode has a particular sound. For

instance, Dorian has a jazzy minor

vibe, Lydian has a spiky major

sound, and Phrygian exudes a fla-

menco flavor. Here’s why: Each

mode has a unique sequence of

whole- and half-steps. You can see

this in E

Ex

x.. 2

2—the steps are iden-

tified as either W (whole) or H

(half ). Compare the sequences,

and then play the modes to hear

how each sequence has its own

sonic character.

When viewing a mode as an in-

version of a major scale, remember

that both the mode and its parent

scale share the same key signature.

To internalize this concept, pick up

1 2 6

GUITAR PLAYER OCTOBER 1999

“Music can’t be accurately described with words.” — Jo h n S c o f i e l d , Ju n e ’ 8 7 G P

==================================

T

A

B

& ö ö ö ö

ö ö ö ö

G Mixolydian

ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö ö

ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö ö

A Aeolian

B Phrygian

W W H W W H W

W H W W H W W

H W W H W W W

10

10

10

8

9

9

7

7

10

10

8

9

9

7

7

10

10

10

8

9

9

7

10

7

==================================

T

A

B

& ö ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö

ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö

C Ionian

D Dorian

E Phrygian

F Lydian

W W H W W W H

W H W W W H W

H W W W H W W

W W W H W W H

8

8

7

10

10

10

7

9

8

7

10

10

10

7

9

7

8

7 10

10

7

9

7

9

8

10

10

7

9

7

9

10

Modes in a Nutshell

B Y A N D Y E L L I S

Ex. 1 Modes of

C

Major: The “Scale Inversion” View

B Locrian

B

C

D

E

F

G

A

B

A Aeolian

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

A

G Mixolydian

G

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

F Lydian

F

G

A

B

C

D

E

F

E Phrygian

E

F

G

A

B

C

D

E

D Dorian

D

E

F

G

A

B

C

D

C Ionian

C

D

E

F

G

A

B

C

Ex. 2

your guitar and rework a pet

major-scale fingering into its

seven corresponding modes.

T

Th

he

e ““ffo

orrm

mu

ulla

a”” v

viie

ew

w.. The

other way to comprehend

modes is wonderfully direct:

Apply a specific formula to a se-

lected major scale, and you’ll

transform it into a mode. Using

this method, the original major

scale and resulting mode are

parallel—they share the same

root or starting note.

For example, lower the 3rd

and 7th tones of any major

scale, it becomes Dorian. Okay,

let’s dive in:

•

C major comprises C, D, E,

F, G, A, B, and C.

• Lower the 3 and 7 (turning

E to Eb and B to Bb), and

presto—

C Dorian: C, D, Eb, F,

G, A, Bb, and C.

E

Ex

x.. 3

3 shows the formulas for

the seven modes of the major

scale. Take

one major scale—

say,

G—and apply these formu-

las to it. Linger with each mode

(

G Dorian, G Phrygian, G Lydi-

an,

G Mixolydian, G Aeolian,

and

G Locrian) to experience its

singular flavor.

C

Co

on

nn

ne

ec

cttiin

ng

g tth

he

e d

do

ottss.. You’ll

need patience to decode

modes, but they’re invaluable

for composing and improvis-

ing, so it’s worth the sweat.

Some suggestions:

• Eventually, you’ll want to

understand modes from both

scale inversion and formula

perspectives, but at first, just fo-

cus on whichever one makes

the most sense to you.

• Listen and play, play and

listen. Your fingers and ears

have a way of unraveling even

the gnarliest music theory.

• Meanwhile, prepare your-

self for one of those

a-ha! mo-

ments. For instance, while ap-

plying the Dorian formula (b3,

b7) to a D major scale (D, E, F#,

G, A, B, C#, D), you’ll play D Do-

rian (

D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D) and

suddenly flash on how these

notes are the

same as if you

started a

C major scale on D

(the 2nd tone). It all connects,

just give it time. g

All of us—no matter how

long we’ve played or how skilled

we are—have gaps in our knowl-

edge. Back Track is an ongoing

Sessions series designed to fill

these holes and inspire musical

breakthroughs. Got a topic you’d

like us to address? Send your

question to Back Track, c/o

Gui-

tar Player, 411 Borel Ave. #100,

San Mateo, CA 94402, or e-mail

it to guitplyr@mfi.com.

Send us your candidate for Lick of the Month

(preferably notated

and on cassette), along with

a brief explanation of why it’s cool and how to

play it. If we select your offering, you’ll get a funky

custom T-shirt that’s available

only to Lick of the

Month club members. Mail your entry to Lick

of the Month,

Guitar Player, 411 Borel Ave. #100,

San Mateo, CA 94402. Include your name, ad-

dress, and phone number. Materials won’t be re-

turned, and please don’t call the office to check

the status of your submission. You’ll get your shirt

if your lick is chosen.

==================================

T

A

B

&

bb 44

öj ö ö ö

ö ä ö öj ö ö ö ö ä öJb ä öJ ö ö ö ö öb öb ö ö ö ö ä öj Î

Swing feel

B maj7

E maj7

Dm7

D m7

b

b

b

Cm7

F7

ö ö ö ö

û

=

3

5

5

6

8

7 5

5

6

5

8

7 6 5

7

8

5

4

4

6

7

3

5

6

3 2

>

>

öb

öb

1

1

2

4

3

1

1

1

2

4

3

2

1

1

3

4

1

1

3

4

4

1

3

1

C H R O M A T I C T O U C H D O W N

L i c k

o f

t h e

M o n t h

THIS MONTH’S LICKMEISTER IS

Lou Tourtellot of Wakefield, Massachusetts.

He writes, “A workmate of mine at Parker

Guitars gets a kick out of this lick. In the

key of

Bb, it starts with a Imaj7-IVmaj7

change and then drops chromatically

(IIIm7-bIIIm7) into a IIm7-V7 turnaround.”

For starters, play this lick with alternate

picking. Then, try sweep picking the arpeg-

gios in bars 3 and 4. “Whenever you pick

up the guitar to play,” concludes Tourtellot,

“pretend you have an audience.” g

www.guitarplayer.com OCTOBER 1999 GUITAR PLAYER

1 2 7

“My parts come from improvisation and accident.” —The Edge, June ’85 GP

Ionian

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Dorian

1

2

b3

4

5

6

b7

Phrygian

1

b2

b3

4

5

b6

b7

Lydian

1

2

3

#4

5

6

7

Mixolydian

1

2

3

4

5

6

b7

Aeolian

1

2

b3

4

5

b6

b7

Locrian

1

b2

b3

4

b5

b6

b7

Ex. 3 Modes: the “Formula” View

© 1999 by Adrian Legg. International copyright secured. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

1 2 8

GUITAR PLAYER OCTOBER 1999 www.guitarplayer.com

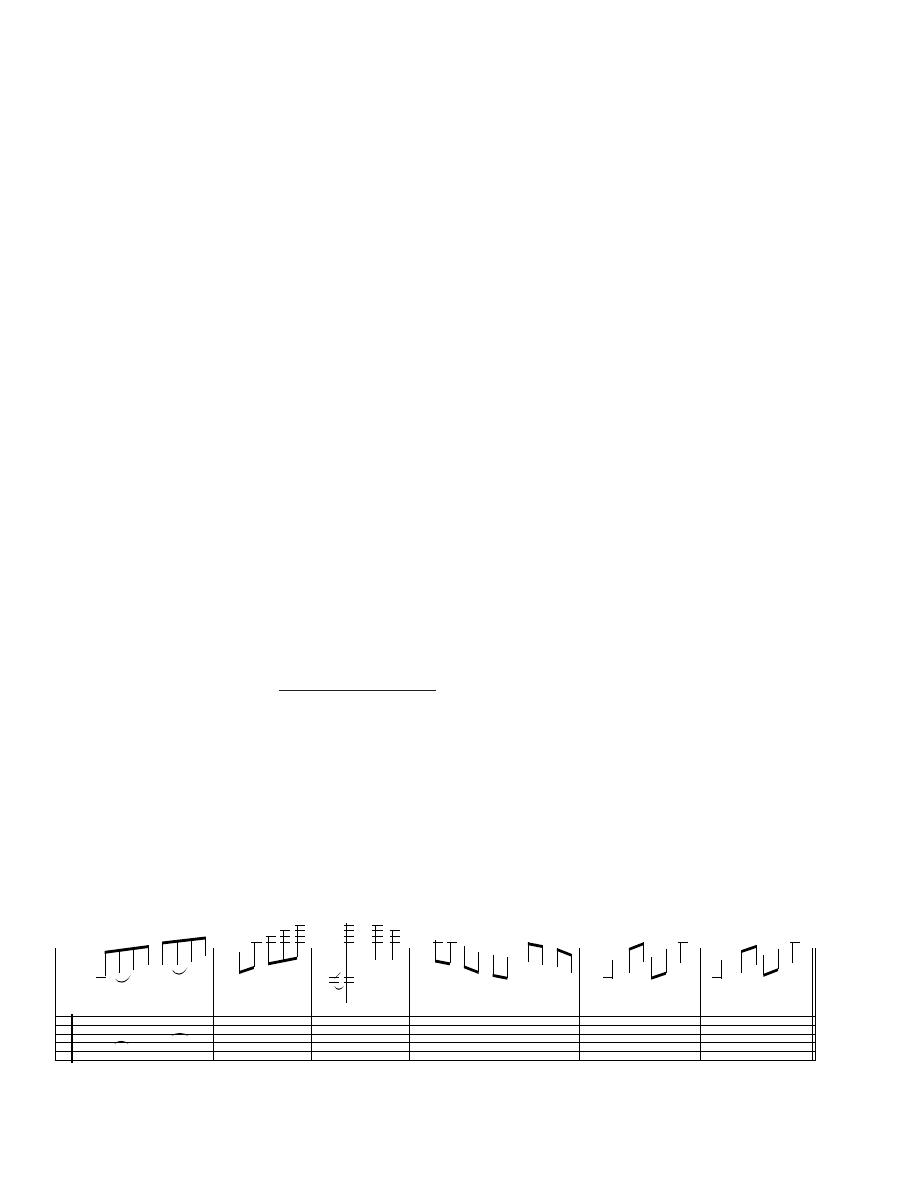

THIS FINGERPICKING

figure is the intro to “Cradle

Songs”—an instrumental from

my recent record,

Fingers &

Thumbs. I recorded the tune

capoed at the 5th fret, because I

like the way open strings ring in

the middle register.

I used a piezo bridge pickup,

which I mention because you

might have intonation difficulties

playing this capoed passage

through a magnetic pickup. If the

low open notes vibrate too close to

the pickup, its magnetic pull could

interfere with string vibration.

P

Pe

errffo

orrm

ma

an

nc

ce

e ttiip

pss.. Play this

passage freely—there’s no partic-

ular tempo for the intro—but

make sure the arpeggios flow up

to the highest note and ripple

smoothly back down.

If you’re playing a non-cutaway

acoustic, your fretting hand will

make contact with the neck joint

when reaching for the high notes.

Just stretch over the guitar’s treble

shoulder a little, and you’ll be able

to grab that

A at the 17th fret.

Anchoring your picking-hand

heel anywhere near the bridge

will inhibit sustain. Instead, let

your arm provide stability from

where it rests on the edge of the

guitar body. (Anchoring with the

pinky doesn’t work for me at all—

it introduces too much rigidity

into my picking hand.)

F

Fiin

ng

ge

erriin

ng

g d

de

etta

aiillss.. For a harp-

like effect, sustain all notes as

long as possible. Here are some

fingering details:

• Hold the low

C (bar 1, beat

one) until you have to move your

2nd finger to play the high

C in

bar 2.

• Also hold that second

G (bar

1, beat three) with your 4th finger

until you have to change posi-

tions in bar 2.

• Let the last note in bar 1 sus-

tain through bar 2. This open

C

should ring under the high

C, and,

in fact, still be ringing when you

pick the

A octaves in bar 3.

• Sustain bar 2’s high

C against

the next two notes (

E and G).

• In bar 4, alternate your 2nd

and 1st fretting fingers as you work

your way across the strings at the

twelfth position. As you descend,

be careful not to disturb the open

string that follows each fretted

note. Pluck the fretted notes with

your thumb and the open strings

with your index finger. g

British fingerstyle wizard Adri-

an Legg offers many useful tips on

his Homespun instructional

video,

How to Cheat at Guitar. His

latest record,

Fingers & Thumbs, is

on Red House Records. For tour-

ing and contact info (as well as

complete transcriptions of Legg’s

wonderful National Public Radio

commentaries), visit www.roe.ac.

uk/mjpwww/legghead.htm.

==================================

T

A

B

&

44

ö ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö 58 ö

ö ö ö

ö

44

e

ú

ú ö ö

54

ö ö ö ö ö ö ö ö

ö ö

44

öb ö

ö ö ö

öU

ö

n

(

)

ö ö

ö ö ö

U

Very freely

capo @ 5th fret

let notes ring

* capo V

2

1

4

1

p

p

i

p

p i

i

m

p

i

i

p

2

1

4

4

m

3

1

m

m

2

2

1

1

2

p p

p

p p

i i

i

i

i

p

p

p

i

m

a

p

p

p

i

m

a

1

1

3

3

1

2

8

5

5

7

10

5

5

7

5

5

13

12

15

5

17

15

12

12

12

5

5

12

12

5

5

13

5

6

5

5

7

6

5

7

5

5

5

6

7

* All 5th fret notes played as open strings.

Cradle Songs

B Y A D R I A N L E G G

B E N S O N PH OTO : V E RY L OA K L A N D

www.guitarplayer.com OCTOBER 1999 GUITAR PLAYER

1 2 9

INSPIRED BY

Wes Montgomery and Djan-

go Reinhardt, George Ben-

son has long embraced oc-

taves for his soloing

and

comping. “Octaves do for

the guitar what a mute does

for a trumpet,” he told

GP.

“When you play a high note

on the guitar, it can be very

obnoxious. With octaves,

the low note has a tendency

to round off that high, shrill

note. When you add the oc-

tave, it softens the sound by

becoming a compromise be-

tween the two notes, be-

cause you don’t really hear

either one, but rather

something in between.

“When I want to add

body to a one-dimensional,

thin sound, I’ll use octaves or

certain formulas that use oc-

taves. One formula has a

sixth in addition to the oc-

tave. For example, I might

play a

G-E-G. The sixth can

move in and out according to

the chord progression.

“Another formula puts a

fifth or fourth within the oc-

tave. To stay within the con-

text of the melodic scale, I

might have to reposition the

inside note—for instance,

changing a fourth to the

fifth—so that I don’t clash

with the harmony.

“Instead of playing the

root and octave simultane-

ously, attack them at differ-

ent times. That’s when the

fun starts—when you play

octaves rhythmically.” g

George

Benson on

Harmonized

Octaves

F

L

A

S

H

B

A

C

K

:

A

U

G

U

S

T

’

7

6

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Gramatyka historyczna in a nutshell

t. osobo in a nutshell, statystyka, statystyka

Physics Papers Steven Weinberg (2003), Damping Of Tensor Modes In Cosmology

usb in a nutshell

Stephen Hawking The Mathematical Universe in a Nutshell

Perl in a Nutshell

Java Nested Types Java in a Nutshell

Polish Commercial Law in a Nutshell

Education in Poland

Participation in international trade

in w4

Metaphor Examples in Literature

Die Baudenkmale in Deutschland

więcej podobnych podstron