Review

The role of child sexual abuse in the etiology

of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury

Maniglio R. The role of child sexual abuse in the etiology of suicide and

non-suicidal self-injury.

Objective: To address the best available scientific evidence on the role

of child sexual abuse in the etiology of suicide and non-suicidal self-

injury.

Method: Seven databases were searched, supplemented with hand-

search of reference lists from retrieved papers. The author and a

psychiatrist independently evaluated the eligibility of all studies

identified, abstracted data, and assessed study quality. Disagreements

were resolved by consensus.

Results: Four reviews, including about 65 851 subjects from 177

studies, were analyzed. There is evidence that child sexual abuse is a

statistically significant, although general and non-specific, risk factor

for suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. The relationship ranges from

small to medium in magnitude and is moderated by sample source and

size. Certain biological and psychosocial variables, such as serotonin

hypoactivity and genes, family dysfunction, other forms of

maltreatment, and some personality traits and psychiatric disorders,

may either act independently or interact with child sexual abuse to

promote suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in abuse victims, with

child sexual abuse conferring additional risk, either as a distal and

indirect cause or as a proximal and direct cause.

Conclusion: Child sexual abuse should be considered one of the several

risk factors for suicide and non-suicidal self-injury and included in

multifactorial etiological models.

R. Maniglio

Department of Pedagogic, Psychological, and Didactic

Sciences, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy

Key words: self-injury; suicide; child abuse; sexual

abuse; etiology; review

Roberto Maniglio, Department of Pedagogic, Psycho-

logical, and Didactic Sciences, University of Salento, Via

Stampacchia 45

⁄ 47, 73100 Lecce, Italy.

E-mail: robertomaniglio@virgilio.it

Accepted for publication September 7, 2010

Summations

• Child sexual abuse is a statistically significant, but modest, risk factor for suicidal and non-suicidal

self-injurious behaviour and ideation.

• Child sexual abuse may not have a primary role in the etiology of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury.

• Additional biological and psychosocial risk factors may, in some cases, be directly responsible for, or,

in other cases, contribute to the risk of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour by

mediating the relationship between child sexual abuse and self-injurious behaviour.

Considerations

• The role of child sexual abuse in the etiology of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury is complex.

• The presence of confounding variables and the poor quality of the studies do not allow for causal

inferences to be made.

• All studies included in this review did not assess data quality and validity and aggregated different

study findings, particularly those with different levels of methodological quality.

Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011: 124: 30–41

All rights reserved

DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01612.x

2010 John Wiley & Sons A/S

ACTA PSYCHIATRICA

SCANDINAVICA

30

Introduction

Lethal and non-lethal self-inflicted injuries, includ-

ing completed and attempted suicide as well as non-

suicidal self-injury (i.e., intentional and direct self-

damaging acts causing bodily harm, without the

intent to die), are a serious public health problem

throughout the world (1–6) and present severe

repercussions on individuals, families, and society

at large (7), including direct and indirect economic

costs (8).

Given the seriousness of self-inflicted injuries,

much literature has attempted to investigate the

factors that promote suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours, with many clinicians and

researchers focusing on child sexual abuse as a

primary etiological factor. In fact, a growing

number of studies addressing the potential associ-

ation between sexual victimization in childhood

and suicide or non-suicidal self-injury in adoles-

cence or adulthood have been published over the

past 20 years. Efforts to summarize the findings of

these studies have resulted in several qualitative

and quantitative reviews.

It should be noted here that although extensive

evidence supports important distinctions between

suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviours

in terms of base rates, frequency, correlates,

lethality, and treatment outcomes (see 9), in the

literature on the sequelae of child abuse, suicidal

and non-suicidal forms of self-injury have been

often considered together as a common outcome

in survivors of child abuse (10, 11). For instance,

both

suicidal

behaviour

and

non-suicidal

self-injurious

behaviour

have

been

seen

as

deliberate self-damaging acts in which abuse

victims engage to reduce abuse-related distress

(see e.g., 12).

In general, literature reviews (e.g., 10, 11, 13–

35) have found high rates of suicidal and non-

suicidal self-injurious behaviours among victims

of child sexual abuse. However, there are funda-

mental questions concerning the nature and the

specific pathways of the association between child

sexual abuse and suicide and non-suicidal self-

injury that remain unanswered. Much of this

uncertainty might be attributable, in part, to the

methodological limitations of the literature on

child abuse. Most reviews of the empirical liter-

ature are characterized by imprecision and sub-

jectivity (see 31, 36). In fact, many reviews have

specified neither the data sources that were

searched nor the criteria used for including

studies. Furthermore, the majority of these liter-

ature reviews have not assessed data quality and

validity and have aggregated different study find-

ings, paying more attention to findings suggesting

harmful effects. As a result, causal inferences

cannot be made and conclusions cannot be drawn.

Thus, the role of sexual victimization in childhood

as a causal factor for suicide and non-suicidal self-

injury in adolescence or adulthood is not well

understood (11).

Aims of the study

To understand how and why some victims of early

sexual victimization self-injury in later life, this

paper provides a qualitative and semi-quantitative

analysis of the findings of the several reviews that

have addressed the literature on the association

between child sexual abuse and suicide and non-

suicidal self-injury. Given the severity of self-

inflicted injuries and with the current high levels

of public and scientific interest in child abuse, an

analysis of what is currently known about the

potential role of child sexual abuse in the etiology

of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury is required to

implement research and prevention efforts.

Material and methods

Given that this systematic review is part of a more

comprehensive review of the literature on child

sexual abuse, the methods are illustrated in detail

elsewhere (37, 38) and are only briefly described

here.

To obtain relevant studies, seven internet-based

databases (AMED, Cochrane Reviews, EBSCO,

ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and ScienceDi-

rect) were searched for articles published between

January 1966 and December 2008. Separate

searches were conducted for the keywords child

(hood) sexual abuse and child(hood) sexual mal-

treatment. Further articles were identified by a

manual search of reference lists from retrieved

papers.

Studies were included whether they (i) appeared

in peer-reviewed journals; (ii) were published in

full; (iii) were critical reviews of the literature; (iv)

were not dissertation papers, editorials, letters,

conference proceedings, books, and book chapters;

(v) reviewed studies sampling human subjects; (vi)

investigated medical, neurobiological, psychologi-

cal, behavioural, sexual, or other health problems

following

childhood

sexual

abuse;

(vii)

had

primary and sufficient data derived from longitu-

dinal, cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort stud-

ies. For the purposes of the present systematic

review, only reviews that examined suicidal and

non-suicidal forms of self-injury following child

sexual abuse were included.

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

31

In accordance with guidelines for systematic

reviews (39–44), data were abstracted and study

quality was assessed on the basis of the following

criteria: (i) evidence identification, i.e., the data

sources (e.g., computerized databases, key jour-

nals, or reference lists from pertinent articles and

books) used to identify studies, including years

searched, keywords, and constraints; (ii) study

selection, i.e., the criteria used to select studies for

inclusion in the review; (iii) data extraction, i.e., the

process by which researchers obtained the neces-

sary information about study characteristics and

findings from the included studies; (iv) quality

assessment, i.e., the criteria or guidelines used for

assessing data quality and validity; (v) data syn-

thesis and analysis, i.e., the methods used to

analyze the results and the strength of evidence

as well as the description of the main results in an

objective, rigorous, and transparent fashion, with

the highest quality evidence available receiving the

greatest emphasis. Based on these criteria, each

study was assigned one of the following ratings:

good (study meets all criteria well), fair (study

does not meet one criterion), or poor (study does

not meet more than one criterion). Those studies

which were judged poor were rejected, because

they had important methodological limitations

that could invalidate their results.

Given that the assessment of all the papers by at

least two researchers working independently may

limit biases, minimize errors, improve reliability of

findings, reduce the possibility that relevant reports

will be discarded, and ensure that decisions and

judgments are reproducible (39, 41), the author,

R. M., and a psychiatrist, professor of Criminol-

ogy, independently evaluated the eligibility of all

studies identified, abstracted data, and assessed

study quality. Disagreements among authors were

discussed and resolved by consensus after review of

the article and the review protocol.

Results

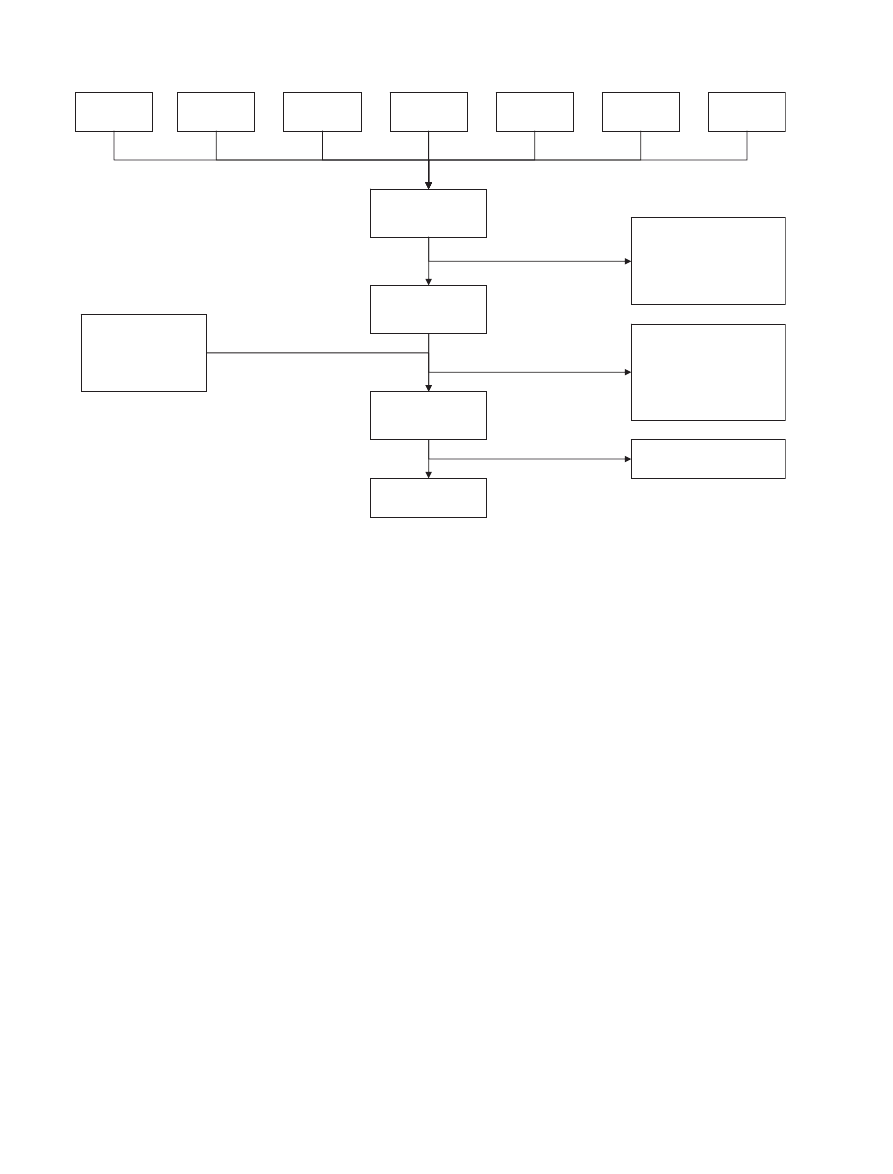

A total of 20 535 articles were identified. The

internet-based search identified 20 502 articles, 0

from AMED, 9 from Cochrane, 1550 from EBSCO,

1154 from ERIC, 2514 from MEDLINE, 7956 from

PsycINFO, and 7319 from ScienceDirect. Thirty-

three articles were identified by the manual search of

reference lists. Two hundred and forty-four full-text

articles were retrieved for more detailed evaluation

and 39 fulfilled all inclusion criteria. Of these, 35 did

not meet more than one of the quality criteria. For

these reasons, these studies were judged poor and

were rejected. Four reviews were judged fair,

because they did not meet the fourth criterion (i.e.,

they lacked a formal quality assessment) and were

included in this systematic review. A summary of

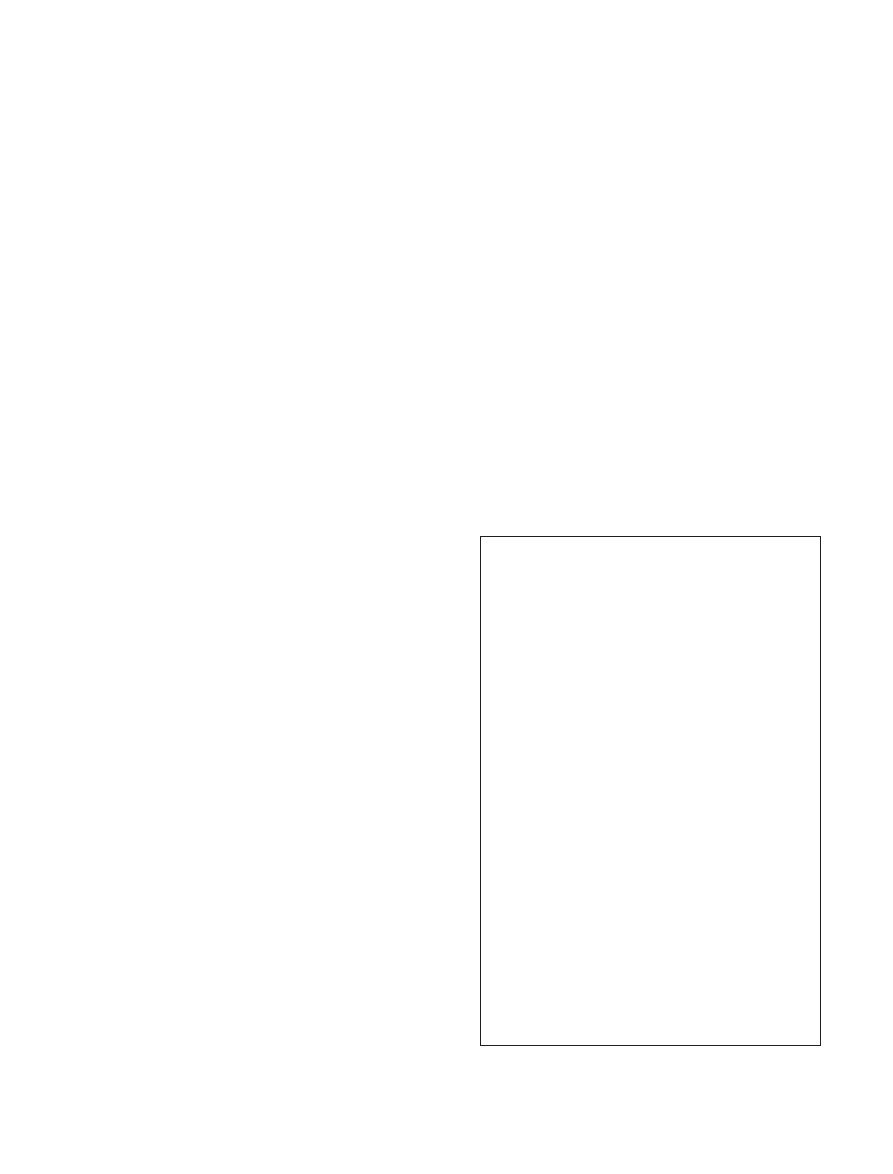

the study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Description of studies

The four reviews included in this systematic review

are described in Table 1. All the meta-analyses

were published between 1996 and 2008 and

reviewed a total of 177 studies (including 222

different subject samples, with 65 851 subjects). Six

(3.38%) of these studies were analyzed by more

than one review. The following sample types were

investigated: both young and adult subjects, only

adults, both males and females, and only females.

One of these meta-analyses focused on non-

suicidal self-injurious behaviour. All the other

reviews assessed suicide or non-suicidal self-injury

along with several other psychological or behavio-

ural sequelae of child sexual abuse. In the studies

included in each review, suicidal and non-suicidal

self-injurious behaviours were usually measured by

suicide and non-suicidal self-injury inventories,

scales, or questionnaires, investigator-authored

items or questions, or suicide and non-suicidal

self-injury-related items, or subscales from clinical

questionnaires, scales, and inventories.

All these reviews detailed the data sources used

to identify studies, the criteria used to select studies

for inclusion in the review, and the process by

which researchers acquired the necessary informa-

tion concerning study characteristics and findings

from the included studies. All the reviews under-

took a quantitative analysis of the data (i.e., meta-

analysis) to infer whether child sexual abuse was

significantly related to suicidal and non-suicidal

self-injurious behaviours and to estimate the

strength of this relationship. All the meta-analyses

described the main results in an objective fashion,

specified the methods that were employed to obtain

these results, took into account the strength of

evidence, investigated whether any observed effects

were consistent across studies, explored possible

reasons for any inconsistencies, and outlined how

heterogeneity was explored and quantified.

The following moderator variables were ana-

lyzed: form and date of publication of the study,

site of the study, size and source of the samples,

gender, socioeconomic status, and age of the

subjects at the time of assessment, sampling

strategy, method of assessment of abuse (e.g.,

questionnaire list), type of statistic used, definition

of child sexual abuse based on the maximum age of

victim, level of contact, consent, force, frequency,

and duration of abuse, relationship to the perpe-

trator (e.g., parent), age when abused. Multiple

Maniglio

32

regression, analysis of variance, and test of cate-

gorical models were used to determine whether

moderator variables accounted for significant

heterogeneity in effect sizes.

The main findings of the four meta-analyses

included in this systematic review are qualitatively

and semi-quantitatively analyzed in an evidence-

based, objective, and balanced fashion, with the

highest quality evidence available receiving the

greatest emphasis (45). To represent the degree of

the relationship between child sexual abuse and

suicide and non-suicidal self-injury, the effect size

estimators d and r were used. Positive d and r

values indicate higher levels of symptomatology for

sexually abused participants compared with con-

trol participants. According to Cohen (46), d of

0.20, 0.50, and 0.80, and r of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50

correspond to small, medium, and large effect

sizes.

Strength of the association between child sexual abuse and

suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour

In their review, Klonsky and Moyer (24) under-

took a meta-analysis of 45 samples from 43 studies,

with a total of 13 687 subjects, to address the

relationship between child sexual abuse and non-

suicidal self-injurious behaviour. Results showed

that child sexual abuse was significantly related to

non-suicidal self-injury. Such association was small

in magnitude.

Neuman et al. (26) provided 15 meta-analyses to

address the relationship of child sexual abuse with

a variety of psychological, behavioural, and sexual

problems, including self-mutilation and suicidal

ideation or behaviour. Three studies were used in

the non-suicidal self-injury meta-analysis and eight

in the suicidal ideation or behaviour meta-analysis.

Results indicated that child sexual abuse was

significantly related to suicidal and non-suicidal

self-injurious behaviour. The magnitudes of such

relationships were small to medium. Child sexual

abuse was significantly related also to all the other

problems, with magnitudes ranging from small to

medium.

In the review by Paolucci et al. (28), six meta-

analyses were undertaken to address the associa-

tion of child sexual abuse with a number of

psychological, behavioural, and sexual outcomes,

including suicidal ideation or behaviour. Ten

studies, with a total of 4008 subjects, were used

in the suicidal ideation or behaviour meta-analysis.

Results indicated a significant association between

child sexual abuse and suicidal ideation or behav-

iour. Such relationship was nearly medium in

magnitude. Child sexual abuse was significantly

AMED (n = 0)

Cochrane

(n = 9)

EBSCO

(n = 1550)

ERIC

(n = 1154)

Articles identified and

screened for retrieval

(n = 20 502)

Articles retrieved for

more detailed

evaluation (n = 211)

Articles excluded on title /

abstract review (n = 20 291):

editorials, letters, or conference

proceedings; no critical review

of the literature; no focus on

effects of child sexual abuse

Articles excluded on full-text

review (n = 205): no critical

review of the literature; no

focus on depression; no

sufficient data from

longitudinal, cross-sectional,

case-control, or cohort studies

Articles identified from

reference lists of

retrieved articles and

retrieved for detailed

evaluation (n = 33)

Articles included for

quality assessment

(n = 39)

MEDLINE

(n = 2514)

PsycINFO

(n = 7956)

Sciencedirect

(n = 7319)

Articles included

(n = 4)

Articles rejected on quality

assessment (n = 35)

Fig. 1.

Summary of study selection process.

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

33

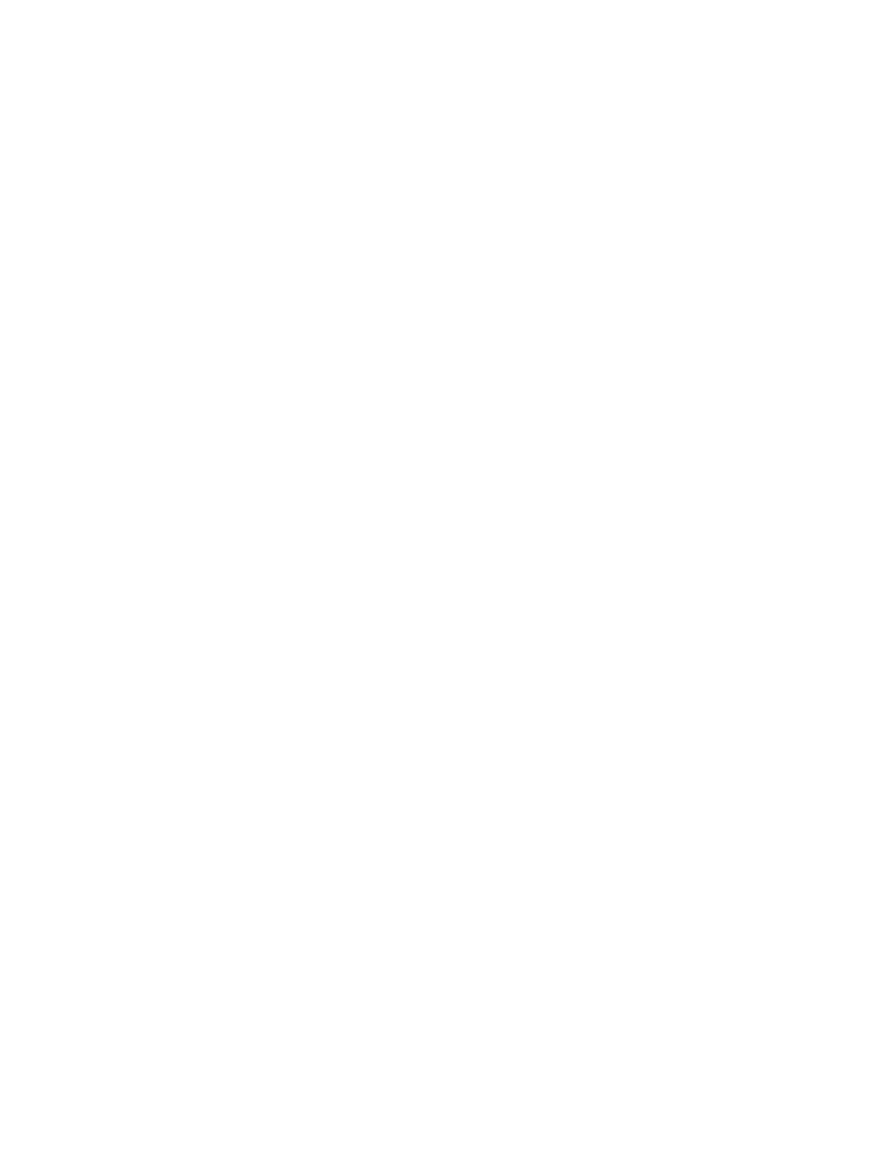

Table

1.

Description

and

results

of

the

included

reviews

Source

Main

methods

Subjects

Outcome

variables

Moderator

variables

Significant

outcomes

(effect

sizes

or

odds

ratios

[95%

confidence

interval];

homogeneity)

Significant

moderators

(between-group

homogeneity)

Klonsky

&

Moyer

(24)

Systematic

search;

study

selection;

meta-analysis

Male

&

female

young

&

adult

patients

&

non-patients

(43

studies,

45

samples,

13

687

subjects)

Self-injurious

behaviour

Sample

size

and

source,

gender

and

age

of

the

subjects

at

the

time

of

assessment

Self-injurious

behaviour

(u

=

0.23

[0.20–0.26],

P

<

0.001;

Q

=

90.47,

P

<

0.001)

Sample

source

(Q

=

5.34,

P

<

0.001),

sample

size

(N

>

125:

u

=

0.21)

Neuman

et

al.

(26)

Systematic

search;

study

selection;

meta-analysis

Female

adult

patients

or

non-patients

(38

studies,

11

162

subjects)

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

,

self-mutilation,

overall

psychopathology

,

anger

,

anxiety

,

depression,

revictimization,

sex

problems,

substance

abuse,

self-concept,

interpersonal

problems,

dissociation,

obsessions

or

compulsions,

somatization,

posttraumatic

stress,

general

symptoms

Publication

date

and

form,

sample

size

and

source,

age

of

subjects

at

the

time

of

assessment,

assessment

of

abuse,

type

of

statistic,

relationship

to

the

perpetrator

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

(d

=

0.34

[0.24–0.44]),

self-mutilation

(d

=

0.42

[0.19–0.64]),

overall

psychopathology

(d

=

0.37

[0.33–0.41];

Q

=

62.36,

P

<

0.01),

anger

(d

=

0.39

[0.25–0.51]),

anxiety

(d

=

0.40

[0.34–0.47]),

depression

(d

=

0.41

[0.36–0.46]),

revictimization

(d

=

0.67

[0.50–0.84]),

sex

problems

(d

=

0.36

[0.30–0.42]),

substance

abuse

(d

=

0.41

[0.31–0.51]),

self-concept

(d

=

0.32

[0.32–0.47]),

interpersonal

problems

(d

=

0.39

[0.22–0.46]),

dissociation

(d

=

0.39

[0.32–0.47]),

obsessions

⁄

compulsions

(d

=

0.34

[0.22–0.46]),

somatization

(d

=

0.34

[0.24–0.45]),

posttraumatic

stress

(d

=

0.52

[0.44–0.59]),

general

symptoms

(d

=

0.46

[0.40–0.52])

Overall

impairment:

sample

source

(Q

B

=

9.40,

P

<

0.01)

Paolucci

et

al.

(28)

Systematic

search;

study

selection;

meta-analysis

Male

&

female

young

&

adult

patients

&

non-patients

(37

studies,

88

samples,

25

367

subjects)

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

,

depression,

posttraumatic

stress,

early

sex

or

prostitution,

sex

perpetration,

intelligence

or

learning

Gender

and

socioeconomic

status

of

subjects

at

the

time

of

assessment,

level

of

contact

and

frequency

of

abuse,

relationship

to

the

perpetrator

,

age

when

abused

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

(d

=

0.44

[0.40–0.48]),

depression

(d

=

0.44

[0.41–0.47]),

posttraumatic

stress

(d

=

0.40

[0.37–0.43]),

early

sex

⁄

prostitution

(d

=

0.29

[0.25–0.32]),

sex

perpetration

(d

=

0.16

[0.11–0.21]),

intelligence

⁄learning

(d

=

0.19

[0.12–0.26])

Maniglio

34

Table

1.

Continued

Source

Main

methods

Subjects

Outcome

variables

Moderator

variables

Significant

outcomes

(effect

sizes

or

odds

ratios

[95%

confidence

interval];

homogeneity)

Significant

moderators

(between-group

homogeneity)

Rind

et

al.

(31)

Systematic

search;

study

selection;

meta-analysis

Male

&

female

adult

non-patients

(59

studies,

51

samples,

15

635

subjects)

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

,

overall

psychopathology

,

alcohol,

anxiety

,

depression,

dissociation,

eating

disorders,

hostility

,

interpersonal

sensitivity

,

locus

of

control,

obsessions

or

compulsions,

paranoia,

phobia,

psychosis,

self-esteem,

sex

problems,

social

impairment,

somatization,

general

symptoms

Publication

form,

study

site,

sampling

strategy

,

gender

and

age

of

the

subjects

at

the

time

of

assessment,

sampling

strategy

,

assessment

of

abuse,

age

of

victim

in

abuse

definition,

level

of

contact,

consent,

force,

frequency

,

and

duration

of

abuse,

relationship

to

the

perpetrator

Suicidal

ideation

or

behaviour

(r

=

0.09

[0.06–0.12];

v

2

=

10.94),

overall

psychopathology

(r

=

0.09

[0.08–0.11];

v

2

=

49.19,

P

>

0.50),

alcohol

(r

=

0.07

[0.02–0.12];

v

2

=

2.97),

anxiety

(r

=

0.13

[0.10–0.15];

v

2

=

4.62),

depression

(r

=

0.12

[0.10–0.14];

v

2

=

25.71),

dissociation

(r

=

0.09

[0.04–0.15];

v

2

=

1.86),

eating

disorders

(r

=

0.06

[0.02–0.10];

v

2

=

9.92),

hostility

(r

=

0.11

[0.06–0.16];

v

2

=

11.22,

P

<

0.05),

interpersonal

sensitivity

(r

=

0.10

[0.06–0.15];

v

2

=

11.78),

obsessions

⁄

compulsions

(r

=

0.10

[0.06–0.15];

v

2

=

5.01),

paranoia

(r

=

0.11

[0.07–0.16];

v

2

=

10.34),

phobia

(r

=

0.12

[0.07–0.17];

v

2

=

8.08),

psychosis

(r

=

0.11

[0.06–0.15];

v

2

=

10.13),

self-esteem

(r

=

0.04

[0.01–0.07];

v

2

=

51.31,

P

<

0.05),

sex

problems

(r

=

0.09

[0.07–0.11];

v

2

=

39.49,

P

<

0.05),

social

impairment

(r

=

0.07

[0.04–0.10];

v

2

=

20.37),

somatization

(r

=

0.09

[0.06–0.12];

v

2

=

15.20),

general

symptoms

(r

=

0.12

[0.08–0.15];

v

2

=

18.77)

Overall

impairment:

incest

(r

=

0.09),

gender

⁄consent

interaction

(z

=

2.51,

P

>

0.02;

females,

r

=

0.11

[0.09–0.13];

v

2

=

14.50)

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

35

related also to all the other outcomes, with

magnitudes ranging from small to medium.

Rind et al. (31) provided 18 meta-analyses to

address the relationship of child sexual abuse with

a variety of psychological, behavioural, and sexual

problems, including suicidal ideation or behaviour.

Nine samples, with a total of 5425 subjects,

were used in the suicidal ideation or behaviour

meta-analysis. Results showed that child sexual

abuse was significantly related to suicidal ideation

or behaviour. The magnitude of such relationship

was of small size. Child sexual abuse was signifi-

cantly related to several other outcomes, with

magnitudes of small size.

Moderators of the relationship between child sexual abuse and

suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour

Klonsky and Moyer (24) found that the distribu-

tion of effect size estimates exhibited significant

heterogeneity. An analog of an analysis of variance

procedure appropriate for effect size data showed

that sample type was a significant moderator of the

relationship between abuse and non-suicidal self-

injury. This relationship was stronger for the

clinical samples than for the non-clinical samples.

Further analysis of effect sizes revealed that some

explanation of effect size variance was also

accounted for by sample size. Studies with larger

samples (N > 125) reported smaller effect sizes.

According to the authors, this result suggested the

possibility of a bias toward publishing studies with

statistically significant results, because studies with

smaller sample sizes required larger effect sizes to

achieve statistical significance. Indeed, formal

analyses found evidence of publication bias, sug-

gesting that smaller studies with positive findings

were more likely to be published than smaller

studies with null or negative findings.

In the review by Neuman et al. (26), a significant

heterogeneity among effect sizes was found. Focus-

ing on the sample-level rather than symptom-level

effect sizes, the authors found that the variability in

sample-level effect sizes could be accounted for by

sample source. Clinical samples generated larger

effect sizes. There was a tendency for studies with

smaller samples (N < 50) to yield comparatively

high mean effect sizes, compared to studies that

examined larger numbers of subjects.

In the review by Paolucci et al. (28), a series of

analyses of variance revealed that none of the

moderators was statistically significant.

Rind et al. (31) found that the effect sizes were

generally homogeneous. Further analysis of the

sample-level effect sizes indicated that larger effect

size estimates were significantly linked to intra-

familial abuse and definition of abuse including

both willing and unwanted sex (only for women).

Importantly, certain family variables (i.e., physical

or emotional abuse and neglect, adaptability, con-

flict or pathology, family structure, support or

bonding, and traditionalism) were confounded with

child sexual abuse. The confounding of child sexual

abuse and family environment raised the possibility

that child sexual abuse was not causally related to

outcomes or was related in a smaller way than

uncontrolled analyses had indicated. To address

this issue, the relationship between family variables

and symptoms was examined. Thus, 18 further

meta-analyses were provided. Two samples, includ-

ing 634 subjects, were used in the suicidal ideation

or behaviour meta-analysis. Results showed that

family environment was significantly related to

suicidal ideation or behaviour (r = 0.26; 95%

confidence interval: [

)0.18 to 0.33]). The magnitude

of such relationship was medium to large, and, thus,

larger than that of the association between child

sexual abuse and suicidal ideation or behaviour.

Discussion

Main results from the studies

i) Across methodologies, samples, and mea-

sures, there is a statistically significant

association between child sexual abuse and

suicidal

and

non-suicidal

self-injurious

behaviour or ideation.

ii) The magnitude of the relationship between

child sexual abuse and suicide and non-

suicidal self-injury ranges from small to

medium.

iii) Child sexual abuse is significantly related

also to several other psychological and

behavioural problems.

iv) Sample source and sample size account, in

part, for effect size variance, with studies

with smaller samples and subject samples

drawn from clinical populations reporting

larger effect sizes.

v) All the other moderators generate conflicting

or non-significant results: more severe and

traumatic forms of sexual victimization such

as those involving force, violence, penetra-

tion, longer duration, and high frequency of

sexual contact do not increase the likelihood

of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in

people who have been sexually victimized

as children.

The results of the four meta-analyses included

in

this

systematic

review

show

that

across

Maniglio

36

methodologies, samples, and measures, survivors

of child sexual abuse are significantly at risk of

suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. However, child

sexual abuse was significantly related also to

several other psychological and behavioural prob-

lems. Therefore, child sexual abuse should be

considered a general, non-specific risk factor for

suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviours.

The magnitude of the relationship between child

sexual abuse and suicide and non-suicidal self-

injury ranged from small to medium. Moderator

analyses revealed that sample source and sample

size accounted, in part, for effect size variance.

More specifically, studies with smaller samples

reported larger effect sizes. This result suggests the

possibility of publication bias, with smaller studies

with positive findings being more likely to be

published than smaller studies with null or negative

findings (24). Furthermore, subject samples drawn

from clinical populations yielded larger effect sizes

than did subject samples drawn from non-clinical

samples. This result suggests that psychiatric sam-

ples tend to exclude well-adjusted survivors of

sexual abuse because these samples are likely to

constitute the negative extreme of abuse outcomes

(31). In contrast, community and student samples

tend to include more well-adjusted abuse survivors,

because a certain level of wellness is required to

perform daily activities, such as occupational tasks,

school

obligations,

family

responsibilities,

or

household activities.

All the other moderators generated conflicting or

non-significant

results.

Many

clinicians

and

researchers (see, e.g., 11, 14, 15) have suggested

that the relationship between child sexual abuse

and suicide and non-suicidal self-injury may be

greater for more severe and traumatic forms of

sexual victimization, such as those involving force,

violence, penetration, longer duration, and high

frequency of sexual contact. Nevertheless, the

results of this systematic review do not confirm

suspicions that such factors concerning aspects of

the abuse experience increase the likelihood of

suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in people who

have been sexually victimized as children.

Causality issues

The results of this systematic review show a

statistically significant, but modest association

between child sexual abuse and suicidal and non-

suicidal self-injurious behaviours. However, it

should be noted that causal inferences cannot be

made, because of the presence of confounding

variables and methodological weaknesses in the

studies included in each review. Many of the

studies investigating the relationship between

child abuse and suicide or non-suicidal self-injury

are characterized by a generally poor methodolog-

ical quality (14). Indeed, most studies have design,

sampling, and measurement problems, such as

poor sampling methods, absence of appropriate

comparison groups, inadequate operationalization

and measurement of abuse histories and outcomes,

insufficient control for effect modifiers and con-

founders, or designs inappropriate to prove cau-

sality. In addition, it should be noted that all the

reviews included in this systematic review did not

assess data quality and validity and aggregated

different study findings, particularly those with

different levels of methodological quality. There-

fore, findings should be interpreted cautiously.

Most importantly, much of the traditional

empirical research on the relationship between

child sexual abuse and suicide or non-suicidal self-

injury has not controlled for the overlap with other

biological, psychological, or social factors that

increase the risk of suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours (see e.g., 11). Thus, it is

unclear whether suicide and non-suicidal self-

injury in subjects who have been sexually abused

in childhood may be attributable to early sexual

abuse or whether suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours may be attributable to other

risk factors that may precede, accompany, or

follow the experience of child sexual abuse.

Several reviews have shown that suicide and

non-suicidal self-injury are related to genetic com-

ponents (47–56), abnormalities in the serotonergic

system (57–60), other forms of child abuse, espe-

cially emotional (61) and physical maltreatment

(21, 62, 63), dysfunctional family relationships and

climate, especially impaired or unsatisfying parent–

adolescent relationships, unsupportive parenting,

high family conflict, low family cohesion, parental

divorce, and ineffective family communication (20,

21, 34, 64), personality variables, especially aggres-

sion (21, 32, 65–67), impulsivity (21, 32, 67),

hopelessness (20, 21, 32, 65, 68, 69), negative

affectivity (see 70), and ineffective problem-solving

ability (21, 32), and psychiatric disorders (20, 21,

65), especially schizophrenia (71, 72) depressive

(73–76), personality (77; see also 78), and sub-

stance-related disorders (79–82), anorexia nervosa

(83, 84), and bipolar (76, 85-87; see also 88),

attention deficit hyperactivity (89), and posttrau-

matic stress disorder (90).

Some of these factors might better account for

the risk of self-injury and suicide in people who

have been sexually victimized as children, rather

than the experience of child sexual abuse itself

having a causal role in the etiology of suicide and

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

37

non-suicidal self-injury. More specifically, there is

evidence that the various forms of child maltreat-

ment are highly prevalent and intercorrelated in

dysfunctional families (13, 63, 91, 92). Speaking

more broadly, it has been noted that, in these

distressed families, it is difficult to determine the

specific effects of child sexual abuse over and above

the effects of dysfunctional environment and

genetic contribution (14, 63, 91, 93), because of

the high prevalence of family problems and co-

occurring forms of child maltreatment as well as

histories of substance abuse, psychiatric disorders,

and suicidal behaviour among parents that may be

transmitted to their offspring (93). For example, in

the meta-analysis by Klonsky and Moyer (24),

those studies that controlled for borderline per-

sonality disorder and family environment revealed

a minimal or negligible relationship between child

sexual abuse and non-suicidal self-injury. In the

meta-analysis by Rind et al. (31), certain family

variables (e.g., family structure, conflict, pathol-

ogy, support or bonding, and traditionalism) were

confounded with child sexual abuse and more

strongly related to suicidal ideation and behaviour

than was child sexual abuse.

In sum, it is possible that, in abusive contexts or

dysfunctional families, both environmental and

biological factors may increase the risk of suicidal

and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviours in off-

spring (93). Multiple risk factors for suicide and

non-suicidal self-injury other than child sexual

abuse, such as a family history of suicidal behav-

iour, mental illness, or substance abuse in parents

and offspring, family conflict or dysfunction, and

other forms of child abuse, might also be present in

these dysfunctional contexts. Some of these factors

may be directly responsible for suicide and non-

suicidal self-injury in the survivors of child sexual

abuse.

In addition, other factors may contribute to the

likelihood of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injuri-

ous behaviours in adolescent or adults who were

sexually abused as children by mediating the

relationship between early sexual victimization

and self-injurious behaviour. In fact, it is possible

that the effects of child sexual abuse on later

suicide and non-suicidal self-injury may operate

through the mediating influences of other vari-

ables, such as neurobiological substrates and

certain personality traits or psychiatric disorders.

In other words, it is possible that child sexual abuse

may promote other biological or psychological

conditions which, in turn, might lead the victim to

engage in suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. In

these cases, child sexual abuse would not have a

direct pathway to suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours but instead would have a

direct relationship with another condition, which,

in turn, would have a direct pathway to self-

injurious behaviour.

More specifically, it is possible that child sexual

abuse may influence suicidal and non-suicidal

self-injurious behaviour by negatively affecting

neurobiological or personality development. For

example, it has been hypothesized that sexual

abuse in childhood may set serotonergic function

at a lower level (94). This effect might persist into

adolescence or adulthood, contributing to the

increased risk for suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours. It has been also suggested

that the effects of serotonin hypoactivity and genes

on suicidal behaviour may operate through impul-

sivity and aggression (32, 65). Furthermore, in the

meta-analysis by Klonsky and Moyer (24), those

studies that controlled for hopelessness suggested

that the relationship between child sexual abuse

and non-suicidal self-injury became minimal or

negligible. Therefore, it is possible that the rela-

tionship between child sexual abuse and suicidal

and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour might be

mediated by neurobiological alterations and some

personality variables, such as impulsivity (95),

aggression (95), poor problem-solving skills (35),

and hopelessness (35).

Most importantly, in many cases, psychological

disturbance, in terms of dysfunctional personality

traits or psychiatric disorders following child

abuse, may lead child sexual abuse survivors to

self-injury to reduce painful abuse-related internal

states. A literature review has shown that most

non-suicidal self-injurers identify the desire to

alleviate negative affect as a reason for self-

injuring and present decreased negative affect

and relief after self-injury (96). It has been

hypothesized that suicidal and non-suicidal self-

injurious behaviours may be seen as emotionally

avoidant coping activities, i.e., behavioural strat-

egies employed to temporarily avoid, reduce,

anesthetize, interrupt, or alleviate unpleasant

internal states, such as, thoughts, memories, feel-

ings, or affects, associated with an abuse history,

to provide survivors with a temporary sense of

calm and relief, at least for some period of time

(10, 12, 16–18, 29, 32, 95–99). In other words, it is

possible that child sexual abuse might lead to

psychic distress, in terms of dysfunctional person-

ality traits, psychiatric disorders, or painful abuse-

related internal states, which, in turn, might lead

child abuse victims to employ emotionally avoi-

dant coping behaviours, such as self-inflicted

injuries, to achieve temporary relief, especially

when these individuals also have concurrent prob-

Maniglio

38

lem-solving deficiencies or poor coping skills (100,

101). Although often effective in the short term,

emotionally avoidant coping strategies are rarely

adaptive in the long term, leading to repeated

cycles of self-inflicted injuries in the presence of

future pain, subsequent calm, the slow building of

further tension, and, ultimately, further self-harm

(16).

In conclusion, the results of this systematic review

reveal that the role of child sexual abuse in the

etiology of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury is

complex. Being a victim of child sexual abuse is a

significant, although general and non-specific, risk

factor for suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious

behaviour and ideation. However, child sexual abuse

is not the only important risk factor for suicide and

non-suicidal self-injury. Evidence to date suggests

that, in many cases, child sexual abuse has not a

primary role in the etiology of suicidal and non-

suicidal self-injurious behaviour. Additional biolog-

ical, psychological, and social risk factors, such as

serotonin hypoactivity and genes, family dysfunc-

tion, co-occurring forms of child maltreatment, and

certain personality traits and psychiatric disorders

may, in some cases, be directly responsible for suicide

and non-suicidal self-injury, or, in other cases,

contribute to the risk of self-inflicted injuries by

mediating the relationship between child sexual abuse

and suicide and non-suicidal self-injury. However, it

is apparent that being a victim of child sexual abuse

may sometimes confer additional risk of suicidal and

non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour either as a

distal and indirect cause or as a proximal and

direct cause. Thus, child sexual abuse should be

considered one of the several risk factors for suicide

and non-suicidal self-injury and included in multi-

factorial etiological models to elucidate the mecha-

nisms that contribute to self-injury in survivors of

child abuse. To achieve this goal, several methodo-

logical advances in research in this area are required,

such as use of longitudinal designs, control for

confounders, employment of study samples repre-

sentative of the general population and matched

comparison groups, and, for literature reviews,

assessment of data quality and validity.

Acknowledgement

I thank Oronzo Greco, MD, University of Salento, Lecce,

Italy, for his help on study selection, data abstraction, and

quality assessment.

Declaration of interest

This study has no external funding source and was not

financial supported. The author has indicated he has no

financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The

author has not other interests in specific in relation to the

pharma industry without any direct connection to this study.

References

1. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A. Suicidal behavior preven-

tion: WHO perspectives on research. Am J Med Genet

2005;133:8–12.

2. Levi F, La Vecchia C, Lucchini F et al. Trends in mortality

from

suicide,

1965–99.

Acta

Psychiatr

Scand

2003;108:341–349.

3. Moscicki EK. Epidemiology of completed and attempted

suicide: toward a framework for prevention. Clin Neu-

rosci Res 2001;1:310–323.

4. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee

S

.

Suicide

and

suicidal

behavior.

Epidemiol

Rev

2008;30:133–154.

5. World Health Organization. Prevention of suicide:

guidelines for the formulation and implementation of

national strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization,

1996.

6. World Health Organization. The global burden of dis-

ease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization,

2008.

7. Miller TR, Covington K, Jensen A. Costs of injury by

major cause, United States, 1995: cobbling together esti-

mates. In: Mulder S, Van Beeck EF, eds. Measuring the

burden of injury. Amsterdam: ECOSA, 1999:23–40.

8. Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM et al. Reducing

suicide: a national imperative. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press, 2002.

9. Nock MK ed. Understanding non-suicidal self-injury:

origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association, 2009.

10. Yates TM. The developmental psychopathology of

self-injurious

behavior:

compensatory

regulation

in

posttraumatic adaptation. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:

35–74.

11. Santa Mina EE, Gallop RM. Childhood sexual and phys-

ical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a

literature review. Can J Psychiatry 1998;43:793–800.

12. Briere J. Child abuse trauma: theory and treatment of the

lasting effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992.

13. Bagley C. The long-term psychological effects of child

sexual abuse: a review of some British and Canadian studies

of victims and their families. Ann Sex Res 1991;4:23–48.

14. Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, Dacosta GA, Akman D.

A review of the short-term effects of child sexual abuse.

Child Abuse Negl 1991;15:537–556.

15. Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, Dacosta GA, Akman D,

Cassavia

E

. A review of the long-term effects of child

sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 1992;16:101–118.

16. Briere JN, Elliot DM. Immediate and long term impacts

of child sexual abuse. Future Child 1994;4:54–69.

17. Briere JN, Runtz M. Childhood sexual abuse: long-term

sequelae and implications for psychological assessment.

J Interpers Violence 1993;8:312–330.

18. Briere J, Runtz M. The long-term effects of sexual

abuse: a review and synthesis. New Dir Ment Health

Serv 1991;51:3–13.

19. Browne A, Finkelhor D. Impact of child sexual abuse:

a review of the research. Psychol Bull 1986;99:66–77.

20. Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with

suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

39

population-based studies. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:957–

979.

21. Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting D, Shaffer D. Youth

suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the

past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry

2003;42:386–405.

22. Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual abuse of boys: definition,

prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management. JAMA

1998;280:1855–1862.

23. Kendall-Tackett K, Williams LM, Finkelhor D. Impact of

sexual abuse on children: a review and synthesis of recent

empirical studies. Psychol Bull 1993;113:164–180.

24. Klonsky ED, Moyer A. Childhood sexual abuse and non-

suicidal

self-injury:

meta-analysis.

Br

J

Psychiatry

2008;192:166–170.

25. Mulvihill D. The health impact of childhood trauma: an

interdisciplinary review, 1997–2003. Issues Compr Pediatr

Nurs 2005;28:115–136.

26. Neumann DA, Houskamp BM, Pollock VE, Briere J. The

long-term sequelae of childhood sexual abuse in women:

a meta-analytic review. Child Maltreat 1996;1:6–16.

27. Nurcombe B. Child sexual abuse I: psychopathology. Aust

N Z J Psychiatry 2000;34:85–91.

28. Paolucci EO, Genuis ML, Violato C. A meta-analysis of

the published research on the effects of child sexual abuse.

J Psychol 2001;135:17–36.

29. Polusny MA, Follette VM. Long-term correlates of child

sexual abuse: theory and review of the empirical litera-

ture. Appl Prev Psychol 1995;4:143–166.

30. Putnam F. Ten year research update review: child sexual

abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:269–

278.

31. Rind B, Tromovitch P, Bauserman R. A meta-analytic

examination of assumed properties of child sexual abuse

using college samples. Psychol Bull 1998;124:22–53.

32. Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Attempted and completed

suicide

in

adolescence.

Annu

Rev

Clin

Psychol

2006;2:237–266.

33. Valente SM. Sexual abuse of boys. J Child Adolesc Psy-

chiatr Nurs 2005;18:10–16.

34. Wagner BM. Family risk factors for child and adolescent

suicidal behavior. Psychol Bull 1997;121:246–298.

35. Yang B, Clum GA. Effects of early negative life experi-

ences on cognitive functioning and risk for suicide:

a review. Clin Psychol Rev 1996;16:177–195.

36. Rind B, Tromovitch P. A meta-analytic review of findings

from national samples on psychological correlates of

child sexual abuse. J Sex Res 1997;34:237–255.

37. Maniglio R. The impact of child sexual abuse on health: a

systematic

review

of

reviews.

Clin

Psychol

Rev

2009;29:647–657.

38. Maniglio R. Child sexual abuse in the etiology of

depression: a systematic review of reviews. Depress

Anxiety 2010;27:631–642.

39. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. CRDs guidance

for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University

of York Press, 2008.

40. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG. Systematic reviews

in health care: meta-analysis in context, 2nd edn. London:

BMJ Publication Group, 2001.

41. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic

reviews of interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons,

2006.

42. Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thou-

sand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000.

43. Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social

sciences: a practical guide. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub-

lishing, 2006.

44. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. Meta-analysis of

observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for

reporting. JAMA 2000;283:2008–2012.

45. Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alter-

native to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:9–18.

46. Cohen J. Statistical power analyses for the behavioral

sciences, 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988.

47. Anguelova M, Benkelfat C, Turecki G. A systematic re-

view of association studies investigating genes coding for

serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter: II.

Suicidal behavior. Mol Psychiatry 2003;8:646–653.

48. Arango V, Huang YY, Underwood MD, Mann JJ. Genetics

of the serotonergic system in suicidal behavior. J Psychi-

atr Res 2003;37:375–386.

49. Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J. Genetics of suicide: an over-

view. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2004;12:1–13.

50. Bellivier F, Chaste P, Malafosse A. Association between

the TPH gene A218C polymorphism and suicidal

behavior: a meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuro-

psychiatr Genet 2004;124:87–91.

51. Bondy B, Buettner A, Zill P. Genetics of suicide. Mol

Psychiatry 2006;11:336–351.

52. Lalovic A, Turecki G. Meta-analysis of the association

between tryptophan hydroxylase and suicidal behavior.

Am J Med Genet 2002;114:533–540.

53. Li D, He L. Meta-analysis supports association between

serotonin transporter (5-HTT) and suicidal behavior. Mol

Psychiatry 2007;12:47–54.

54. Lin PY, Tsai G. Association between serotonin transporter

gene promoter polymorphism and suicide: results of a

meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2004;55:1023–1030.

55. Rujescu D, Thalmaier A, Mıller H-J, Bronisch T, Giegling

I

. Molecular genetic findings in suicidal behavior: what is

beyond the serotonergic system? Arch Suicide Res

2007;11:17–40.

56. Voracek M, Loibl LM. Genetics of suicide: a systematic

review

of

twin

studies.

Wien

Klin

Wochenschr

2007;119:463–475.

57. Mann JJ, Brent DA, Arango V. The neurobiology and

genetics of suicide and attempted suicide: a focus on the

serotonergic

system.

Neuropsychopharmacology

2001;24:467–477.

58. Mann JJ. Role of the serotonergic system in the patho-

genesis of major depression and suicidal behavior. Neu-

ropsychopharmacology 1999;21:99–105.

59. Souery D, Oswald P, Linkowski P, Mendlewicz J. Molecular

genetics in the analysis of suicide. Ann Med 2003;35:191–

196.

60. Van Heeringen K. The neurobiology of suicide and suici-

dality. Can J Psychiatry 2003;48:292–300.

61. Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent

abuse and neglect research: a review of the past 10 years.

Part I: physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J Am

Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1214–1222.

62. Malinosky-Rummell R, Hansen DJ. Long-term conse-

quences of childhood physical abuse. Psychol Bull

1993;114:68–79.

63. Briere J. The long-term clinical correlates of childhood

sexual victimization. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1988;528:327–334.

64. Wagner B, Silverman M, Martin C. Family factors in

youth suicidal behaviors. Am Behav Sci 2003;46:1171–

1191.

Maniglio

40

65. Joiner Te JR, Brown JS, Wingate LR. The psychology and

neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annu Rev Psychol

2005;56:287–314.

66. Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Caine ED. Reac-

tive aggression and suicide: theory and evidence. Aggress

Violent Behav 2003;8:413–432.

67. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, Malone KM. Toward a

clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients.

Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:181–189.

68. Brezo J, Paris J, Turecki G. Personality traits as correlates

of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide

completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand

2006;113:180–206.

69. Glanz LM, Haas GL, Sweeney JA. Assessment of hopeless-

ness in suicidal patients. Clin Psychol Rev 1995;15:49–64.

70. Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA et al. Personality traits as

prospective predictors of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr

Scand 2009;120:222–229.

71. Pinikahana J, Happell B, Keks NA. Suicide and schizo-

phrenia: a review of literature for the decade (1990–1999)

and implications for mental health nursing. Issues Ment

Health Nurs 2003;24:27–43.

72. Reid S. Suicide in schizophrenia. A review of the litera-

ture. J Ment Health 1998;7:345–353.

73. Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric

diagnoses in 3275 suicides: a meta-analysis. BMC Psy-

chiatry 2004;4:37–47.

74. Isometsa ET. Psychological autopsy studies: a review. Eur

Psychiatry 2001;16:379–385.

75. Wolfsdorf BA, Freeman J, Deramo K, Oveholser J, Spirito

A

. Mood states: depression, anger, and anxiety. In: Spirito

A

, Overholser JC, eds. Evaluating and treating adolescent

suicide attempters: from research to practice. New York:

Academic, 2003:55–81.

76. Rihmer Z. Suicide risk in mood disorders. Curr Opin

Psychiatry 2007;20:17–22.

77. Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R. Suicide in

borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Nord J

Psychiatry 2005;59:319–324.

78. Blasco-Fontecilla H, Baca-Garcia E, Dervic K et al.

Severity of personality disorders and suicide attempt.

Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:149–155.

79. Bagge CL, Sher KJ. Adolescent alcohol involvement and

suicide attempts: toward the development of a conceptual

frame work. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:1283–1296.

80. Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A. Adolescent suicidal behav-

ior and substance use: a review with implications for

treatment research. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28:77–88.

81. Hufford MR. Alcohol and suicidal behavior. Clin Psychol

Rev 2001;21:797–811.

82. Mehlenbeck R, Spirito A, Barnett N, Overholser J.

Behavioral factors: substance use. In: Spirito A, Over-

holser JC

, eds. Evaluating and treating adolescent suicide

attempters: from research to practice. San Diego, CA:

Academic Press, 2003:113–146.

83. Franko DL, Keel PK. Suicidality in eating disorders:

occurrence, correlates, and clinical implications. Clin

Psychol Rev 2006;26:769–782.

84. Pompili M, Mancinelli I, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R.

Suicide in anorexia nervosa: a meta-analysis. Int J Eat

Disord 2004;36:99–103.

85. Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide

and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic

review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:693–704.

86. Kilbane EJ, Gokbayrak NS, Galynker I, Cohen L, Tross S.

A review of panic and suicide in bipolar disorder: does

comorbidity increase risk? J Affect Disord 2009;115:1–10.

87. Post RM, Leverich GS, Xing G, Weiss SB. Developmental

vulnerabilities to the onset and course of bipolar disorder.

Dev Psychopathol 2001;13:581–598.

88. Sa´nchez-Gistau V, Colom F, Mane´ A, Romero S, Sugranyes

G

, Vieta E. Atypical depression is associated with suicide

attempt in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand

2009;120:30–36.

89. James A, Lai FH, Dahl C. Attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder and suicide: a review of possible associations.

Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;110:408–415.

90. Panagioti M, Gooding P, Tarrier N. Post-traumatic stress

disorder and suicidal behavior: a narrative review. Clin

Psychol Rev 2009;29:471–482.

91. Briere J, Elliot DM. Sexual abuse, family environment,

and psychological symptoms: on the validity of statistical

control. J Consult Clin Psychol 1993;61:284–288.

92. Sheldrick C. Adult sequelae of child sexual abuse. Br J

Psychiatry 1991;158:55–62.

93. Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetics studies, suicide, and

suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet

2005;133:13–24.

94. Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev

Neurosci 2003;4:819–828.

95. Baud P. Personality traits as intermediary phenotypes in

suicidal behavior. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet

2005;133:34–42.

96. Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a

review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:226–

239.

97. Connors R. Self-injury in trauma survivors: functions and

meanings. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996;66:197–206.

98. Stanley B, Winchel R, Molcho A, Simeon D, Stanley M.

Suicide and the self-harm continuum: phenomenological

and biochemical evidence. Int Rev Psychiatry 1992;4:149–

155.

99. Suyemoto KL. The functions of self-mutilation. Clin Psy-

chol Rev 1998;18:531–554.

100. Maniglio R. Severe mental illness and criminal victimiza-

tion:

a

systematic

review.

Acta

Psychiatr

Scand

2009;119:180–191.

101. Maniglio R. The role of deviant sexual fantasy in the

etiopathogenesis of sexual homicide: a systematic review.

Aggress Violent Behav 2010;15:294–302.

Child sexual abuse and self-injury

41

Copyright of Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be

copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Severity of child sexual abuse and revictimization The mediating role of coping and trauma symptoms

MMPI 2 F Scale Elevations in Adult Victims of Child Sexual Abuse

The Role of Seeing Blood in Non Suicidal Self Injury

Co existence of GM and non GM arable crops the non GM and organic context in the EU1

The Role of Trust and Contractual Safeguards on

How Did You Feel Increasing Child Sexual Abuse Witnesses Production of Evaluative Information

Resistance to organizational change the role of cognitive and affective processes

The Roles of Gender and Coping Styles in the Relationship Between Child Abuse and the SCL 90 R Subsc

Newell, Shanks On the Role of Recognition in Decision Making

Morimoto, Iida, Sakagami The role of refections from behind the listener in spatial reflection

86 1225 1236 Machinability of Martensitic Steels in Milling and the Role of Hardness

ROLE OF THE COOPERATIVE BANK IN EU FUNDS

Illiad, The Role of Greek Gods in the Novel

Hippolytus Role of Greek Gods in the Euripedes' Play

The Role of the Teacher in Methods (1)

THE ROLE OF CATHARSISI IN RENAISSANCE PLAYS - Wstęp do literaturoznastwa, FILOLOGIA ANGIELSKA

The Role of Women in the Church

The Role of the Teacher in Teaching Methods

więcej podobnych podstron