"mess you up"

August 2003

The Deadlift - page 1

Functionality and Wall Ball - page 1

Anatomy and Physiology for Jocks - page 5

Functionality & Wall Ball

Much is currently being made of “functional exercise.”

A Google search returned 950,000 hits for “functional

exercise.” Even a cursory review of the Internet sites

featuring “functional exercise” would seem to support

the notion that functional exercise was something done

on/with Swiss Balls and rubber bands.

Physical therapists define functional exercise as exercise

in multiple planes using multiple joints. Legendary

seminarist

Paul Chek

(

has

his own definition, but much

of what is termed functional

exercise seems to be specialized

exercises closely linked to

rehabilitation and

physical

therapy

8&oe=UTF-8&q=functional+ex

ercise+physical+therapy

Where functional exercise is

touted for athletic training it

seems to be largely about core training – lots of Swiss

ball and trunk work. While surely of some value, this is

not the functionality that CrossFit is pursuing and it is

our contention that the benefits of functional movements,

as we’ll define them, exceeds the orthopedic and

neurological advantages generally cited by advocates of

“functionality”.

We see the bulk of human action as being comprised of

a limited number of irreducible fundamental movements.

These fundamental movements we call functional. They

include, but are not limited to, squatting, deadlifting,

cleaning, lunging/running/walking, jumping, throwing,

climbing, and pressing. (

continued on page 2

)

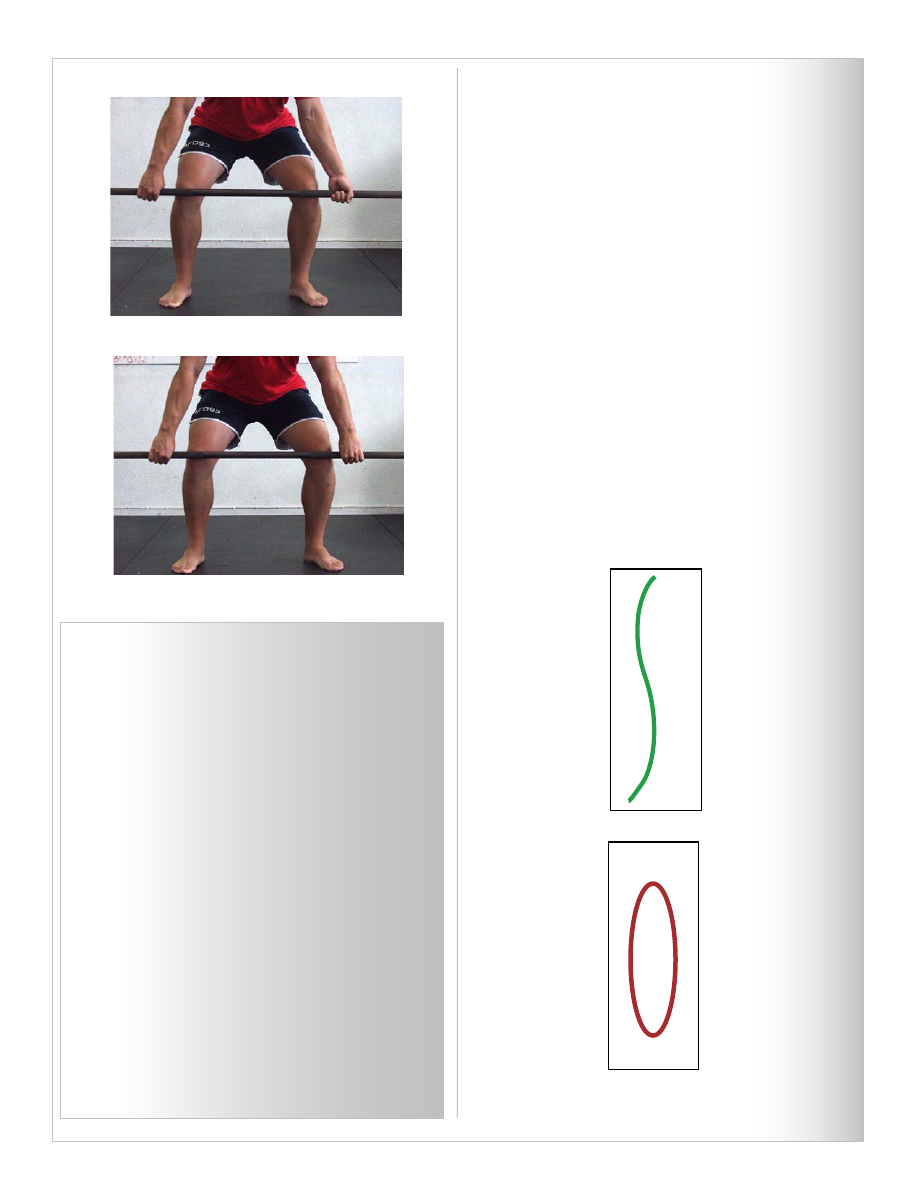

The Deadlift

The deadlift is unrivaled in its simplicity and impact

while unique in its capacity for increasing head to toe

strength.

Regardless of whether your fitness goals are to “rev-up”

your metabolism, increase strength or lean body mass,

decrease body fat, rehabilitate your back, improve athletic

performance, or maintain functional independence as a

senior, the deadlift is a marked shortcut to that end.

To the detriment of millions,

the deadlift is infrequently used

and seldom seen by most of the

exercising public and, believe it

or not, athletes.

It might be that the deadlifts

name has scared away the

masses; it’s older name, “the

healthift”, was a better choice

for this perfect movement.

In its most advanced application

the deadlift is prerequisite

to, and a component of, “the

world’s fastest lift”, the snatch, and “the world’s most

powerful lift”, the clean; but it is also, quite simply, no

more than the safe and sound approach by which any

object should be lifted from the ground.

The deadlift, being no more than picking a thing off the

ground keeps company with standing, running, jumping,

and throwing for functionality but imparts quick and

prominent athletic advantage like no other exercise.

Not until the clean, snatch, and squat are well developed

will the athlete again find as useful a tool for improving

general physical ability.

The deadlift’s primal functionality, whole body nature,

and mechanical advantage with large loads suggest its

strong neuroendocrine impact, and (

continued on page 4

)

THE

CrossFit Journal

IN THIS ISSUE:

1

August 2003

(“Functionality and Wallball”

continued from page 1

)

This atomist or reductionist view has us asking of every exercise “how universal is the motor recruitment pattern?”

When this litmus is applied to biking and the bench press the answer comes back “not very.” When we ask the same of

running and push-press the answer comes back “very.”

The case for a potent neuroendocrine response associated with many of the exercises that we’ve dubbed functional seems

like a fairly straightforward argument. It is known, for instance, that cleans, deads, and squats carry an inordinately large

neuroendocrine response. When you review the list of factors or exercises associated with significant neuroendocrine

response they largely or completely meet our requirements of being fundamental, elemental or irreducible, and universal

to sport and life.

It is our strong and reasoned suspicion that the rest of the entire cast of characters we’re calling functional will eventually

be demonstrated to be responsible for evoking a significant neuroendocrine response. That is, that the pull-up, dip, box

jump, running and the like, used in the manner in which we use them, are making large systemic contributions to

overall fitness. This view while novel, if not revolutionary, takes a back seat to a second CrossFit suspicion that is truly

revolutionary.

We have come to believe that the specificity of cardiorespiratory training adaptations to exercise modality is a function

of an exercise’s lack of functionality. This suggests three things. One, a more functional training modality will offer a

greater cardiorespiratory benefit than a less functional modality. Two, a regimen of functional movements, developed

across all three metabolic pathways develops cardiorespiratory fitness with greater application to a larger number of

activities, which implies the third, there are varying qualities of cardiovascular fitness.

Currently we see each major functional movement carrying with it a cardiorespiratory capacity that can be developed

independently and in conjunction with other functional movements to provide a superior cardiorespiratory response. We

base this view on two commonplace observations in our clinical work.

First, elite runners, cyclists, swimmers, or triathletes crumble when exposed to simple CrossFit-like stressors and their

failure is obviously cardiorespiratory. (Email us and we’ll tell you how we know!

) Second, our

athletes are increasingly doing very well in competitions based on skills and activities for which they’ve little or no

training (if you’d like supporting details of this, again email

).

Run, press, jump, throw, squat, deadlift, lunge, climb, and clean against all three metabolic pathways in varying

combinations, at high intensity and you’ll be at most several weeks out from good to great performance (strength and

conditioning wise) for nearly any sport or activity.

The claim here is that regimens like our WOD are ultimately a better cardiorespiratory prep than cycling or running for any

sport except cycling or running. In fact, the advantage extends to all ten general physical adaptations (cardiorespiratory

endurance, stamina, strength, power, speed, flexibility, agility, accuracy, balance, and coordination).

The cardiorespiratory benefit of mixed modal, high intensity functional movements, a la CrossFit’s WOD is a better,

more useful, broader cardiovascular stimulus than any monostructural activity like biking, swimming, or running - even

in combinations.

The clear implication in light of our view of athletic training and more conventional practices is that the most efficacious

tools available for metabolic conditioning are not generally employed. Until training regimens incorporate traditional

resistance training protocols (weighlifting and gymnastics/calisthenic) to replace or supplement traditional “cardio”

modalities (bike, run, swim, etc.) athletic conditioning remains inferior.

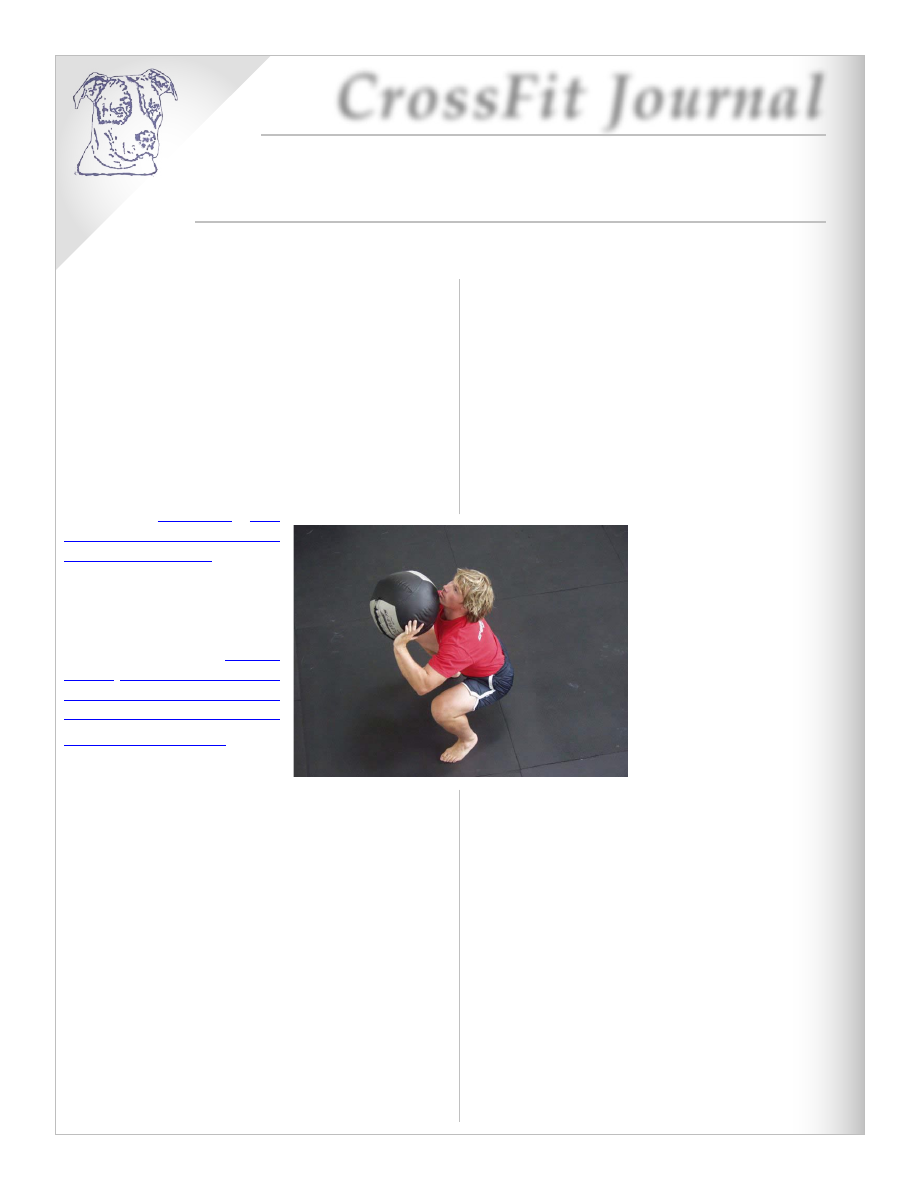

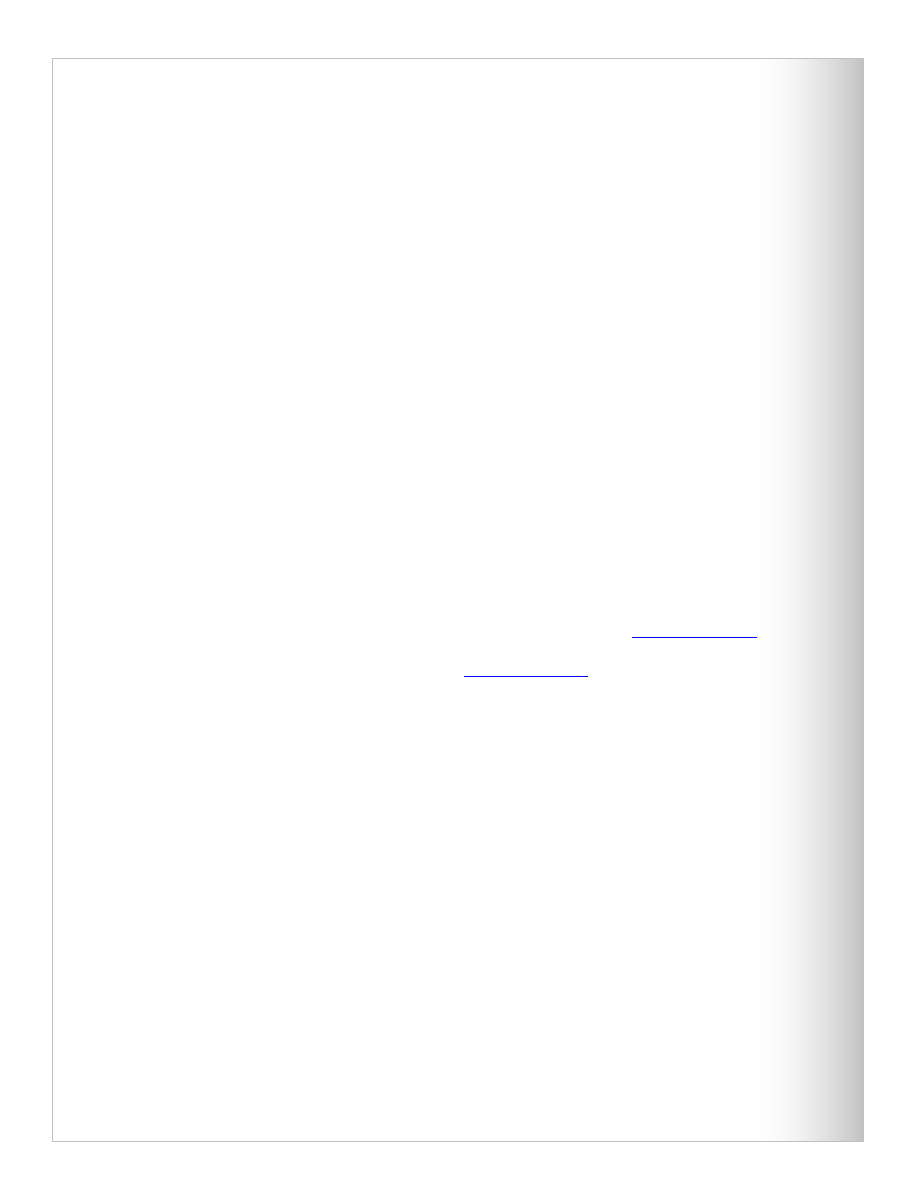

We offer as an example of high functionality and marked carryover of cardiorespiratory benefit to sport and human

performance in general, our “Wall-Ball” exercise. This exercise is largely a front squat and push-press combination. The

functionality of throwing or shooting an object from overhead and standing up is hopefully obvious.

2

August 2003

(“Functionality and Wallball”

continued from page 2

)

We use a 20-pound

and a flat vertical target (originally the wall and hence the name) located

about 8-10 feet above the ground.

The movement begins as a front squat and follows through to a push press/shove that sends the ball up and forward to

the target from which it rebounds back to the throwers outstretched arms where it is “absorbed” back into the squat. In

its entirety the wall-ball is quite simply a throw.

When perfected each shot looks identical to the one before and the ball’s contact and departure are gentle and smooth.

If the athlete endeavors to quiet the drill, the benefit to mechanics and breathing technique are immense.

The drill can be made as difficult as needed by increasing the weight of

the ball, moving back from the target, or raising the target.

Start and see how long you can continue hitting these milestones:

30 seconds/12 shots

1-minute/25 shots

1 1⁄2 - minutes 37 shots

2-minutes/50 shots

2 1⁄2 - minutes 62 shots

3-minutes/75 shots

3 1⁄2 - minutes/87 shots

4-minutes/100 shots

4 1⁄2 - minutes/112 shots

5-minutes/125 shots

5 1⁄2 - minutes/137 shots

6-minutes/150 shots

On failure (falling behind) rest and try again. Over time you want to

get where you can do 150 shots in 6 minutes or less.

Our best time for 150 shots at a 10 feet high with a 20 lb. ball belongs

to Mike Weaver at 4:52.

If you have the resources it might be best to master the drill (6

minutes/150 squats) with the 4-pound ball and work your way up to

the 20-pound ball. (Dynamax has balls at 4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18, and 20

pounds.)

Here are technique fundamentals:

• Each rep begins with a rock bottom squat

• Keep the elbows down and in

• Keep the ball low to the chest

• Don’t let the ball obstruct view of target

• Launch with little finger roll and push

• Make ascending and descending movements the same

• Minimize breathing and ball contact noise

• Breath deeply and attempt to synchronize breathing to shot rate

The wall-ball drill is comprised of two highly functional classical weightlifting movements brought together at light

loads and extended duration to create a super-potent metabolic conditioning tool with an enormous potential for

increasing athletic performance.

3

August 2003

(“The Deadlift”

continued from page 1

)

for most athletes the deadlift delivers such a quick boost in general strength and sense of power that its benefits are

easily understood.

If you want to get stronger, improve your deadlift. Driving your deadlift up can nudge your other lifts upward, especially

the Olympic lifts.

Fear of the deadlift abounds, but like fear of the squat, is groundless. No exercise or regimen will protect the back from

the potential injuries of sport and life or the certain ravages of time like the deadlift. (S

ee Inset “Doc & Coach” - page 5

)

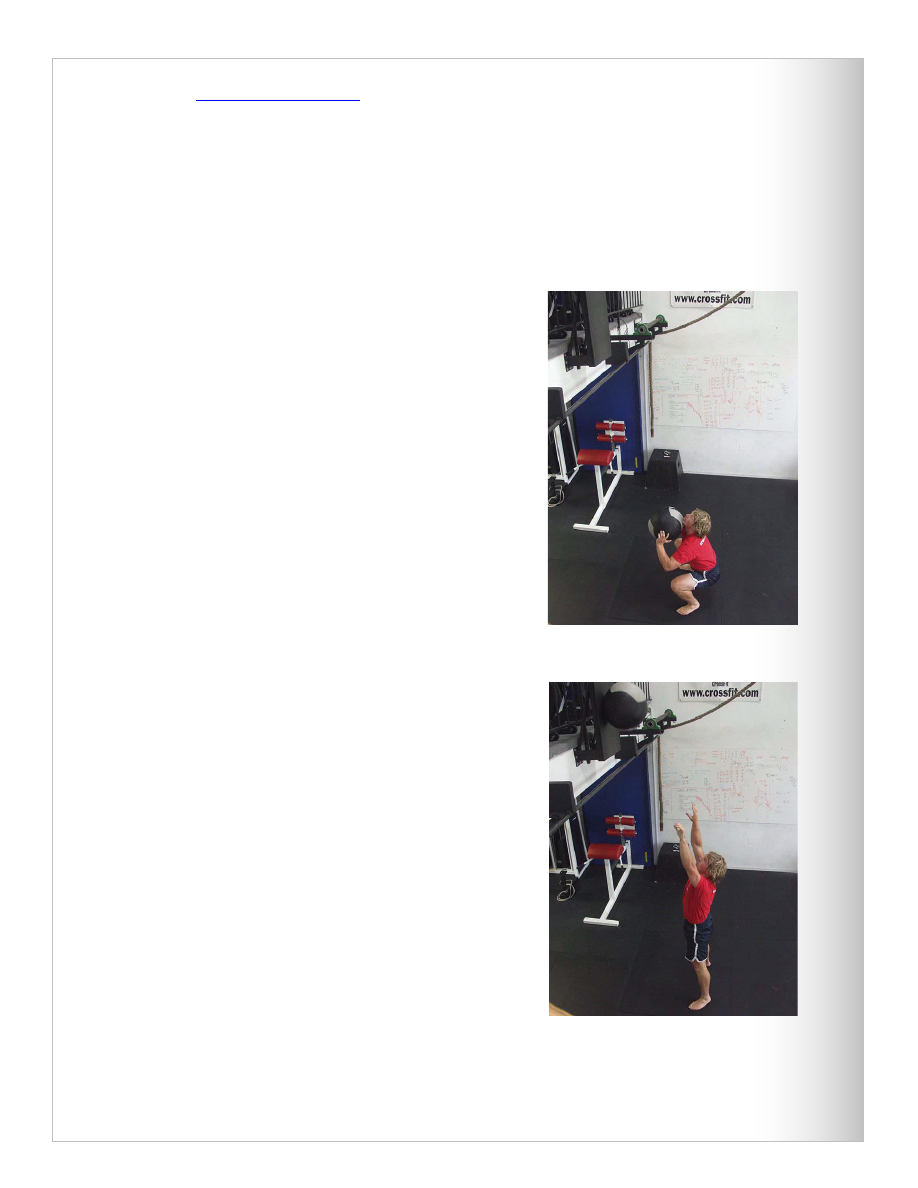

We recommend deadlifting at near max loads once per week or so and maybe one

other time at loads that would be insignificant at low reps. Be patient and learn to

celebrate small infrequent bests.

Major benchmarks would certainly include bodyweight, twice bodyweight, and

three times bodyweight deadlifts representing a “beginning”, “good”, and “great”

deadlifts respectively.

For us, the guiding principles of proper technique rest on three pillars: orthopedic

safety, functionality, and mechanical advantage. Concerns for orthopedic stresses

and limited functionality are behind our rejection of wider than hip to shoulder width

stances. While acknowledging the remarkable achievements of many powerlifters

with the super wide deadlift stance we feel that its limited functionality (we can’t

safely, walk, clean, or snatch from “out there”) and the increased resultant forces

on the hip from wider stances don’t warrant but infrequent and moderate to light

exposures to wider stances.

Experiment and work regularly with alternate, parallel, and hook grips. Explore

carefully and cautiously variances in stance, grip width, and even plate diameter –

each variant uniquely stresses the margins of an all-important functional movement.

This is an effective path to increased hip capacity.

Consider each of the following cues to a sound deadlift. Many motivate identical

behaviors, yet each of us responds differently to different cues.

• Natural stance with feet under hips

• Symmetrical grip whether parallel, hook, or alternate

• Hands placed where arms won’t interfere with legs while pulling from the

ground

• Bar above juncture of little toe and foot

• Shoulders slightly forward of bar

• Inside of elbows facing one another

• Chest up and inflated

• Abs tight

• Arms locked and not pulling

• Shoulders pinned back

• Lats and triceps contracted and pressing one another

• Keep your weight on heels

• Bar stays close to legs and essentially travels straight up and down

• Torso’s angle of inclination remains constant while bar is below the knee

• Head straight ahead or slightly up

• Shoulders and hips rise at same rate when bar is below the knee

• Arms remain perpendicular to ground until lockout

4

August 2003

Anatomy and Physiology for Jocks

Effective coaching requires efficient communication.

This communication is greatly aided by coach and

athlete sharing a terminology for both human movement

and body parts.

We’ve developed an exceedingly simple lesson in

anatomy and physiology that we believe has improved

our ability to accurately and precisely motivate desired

behaviors and enhanced our athletes’ understanding of

both movement and posture.

Basically, we ask that our athletes learn four body parts,

three joints (not including the spine), and two general

directions for joint movement. We cap our A&P lesson

with the essence of sports biomechanics distilled to three

simple rules.

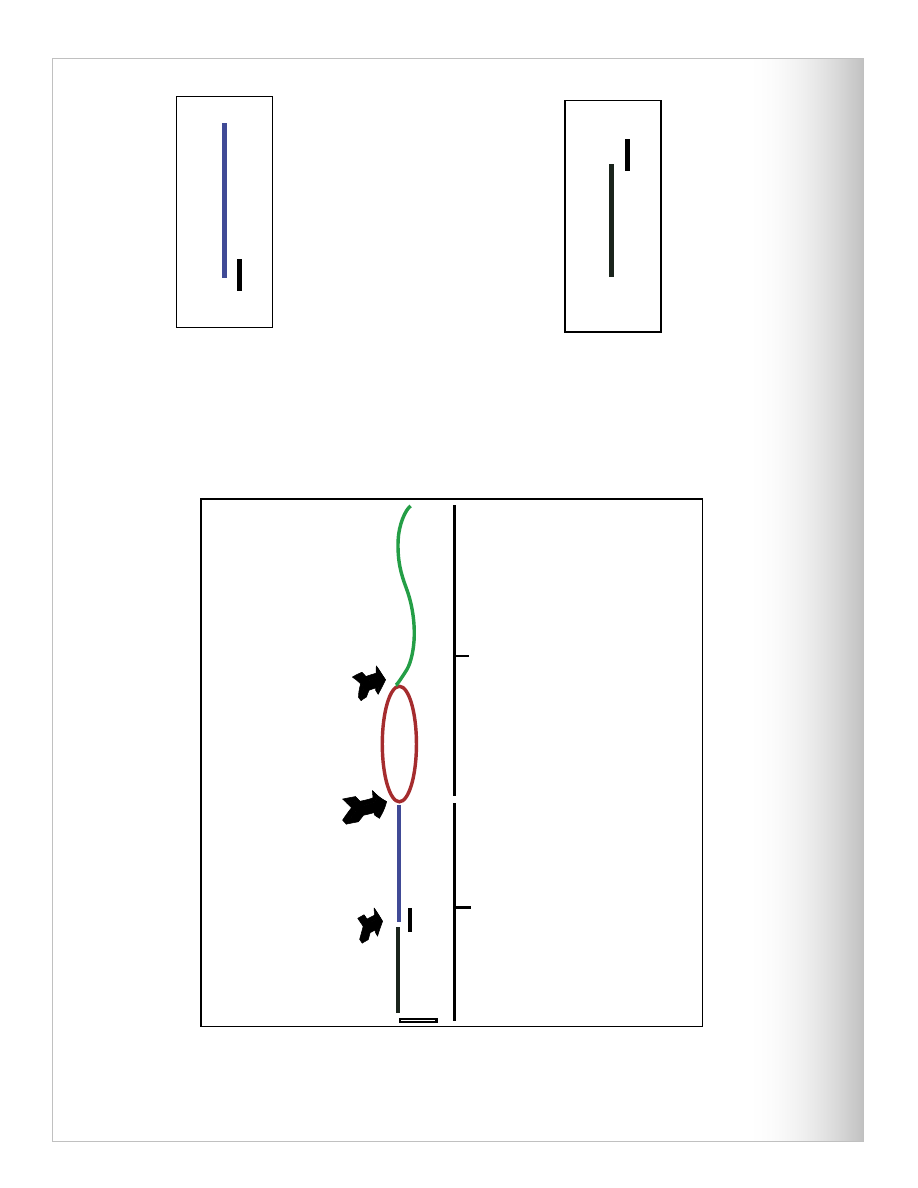

We use a simple iconography to depict the spine, pelvis,

femur, and tibia. We show that the spine has a normal

“S” shape and where it is on the athlete’s body. We

similarly demonstrate the pelvis, femur, and tibia.

(“The Deadlift” continued from page 4)

Mixed Grip

Parallel Grip

Spine

Pelvis

Coach and Doc

(reenactment of actual conversation)

Doc: Many of my patients shouldn’t be doing the

deadlift.

Coach: Which one’s are those, Doc?

Doc: Many are elderly, marginally ambulatory, and

frail/feeble and osteoporotic.

Coach: Doc would you let such a patient, let’s say an

old woman, walk to the store to get cat food?

Doc: Sure, If the walk weren’t too far, I’d endorse it.

Coach: All right, suppose after walking home she

came up to the front door and realized that her keys

were in her pocket. Is she medically cleared to set the

bag down, get her keys out of her pocket, unlock the

door, pick the bag back up, and go in?

Doc: Of course, that’s essential activity

Coach: As I see it the only difference between us

is that I want to show her how to do this “essential

activity” safely and soundly and you don’t.

Doc: I see where you’re going. Good point.

Coach: Doc, we haven’t scratched the surface.

5

August 2003

We next demonstrate the motion of three joints. First, the knee is the joint connecting tibia and femur. Second, working

our way up, is the hip. The hip is the joint that connects the femur to the pelvis. Third, is the sacroiliac joint (SI joint),

which connects the pelvis to the spine. (We additionally make the point that the spine is really a whole bunch of joints.)

We explain that the femur and tibia constitute “the leg” and that the pelvis and spine constitute “the trunk”.

That completes our anatomy lesson – now for the physiology. We demonstrate that “flexion” is reducing the angle of a

joint and that “extension” is increasing the angle of a joint.

Femur

Tibia

��� ������ ��� �����

����� � ������ ��� �����

���� �����

��� �����

���������� �����

������ ��������

���� ���������

���� ���������

6

August 2003

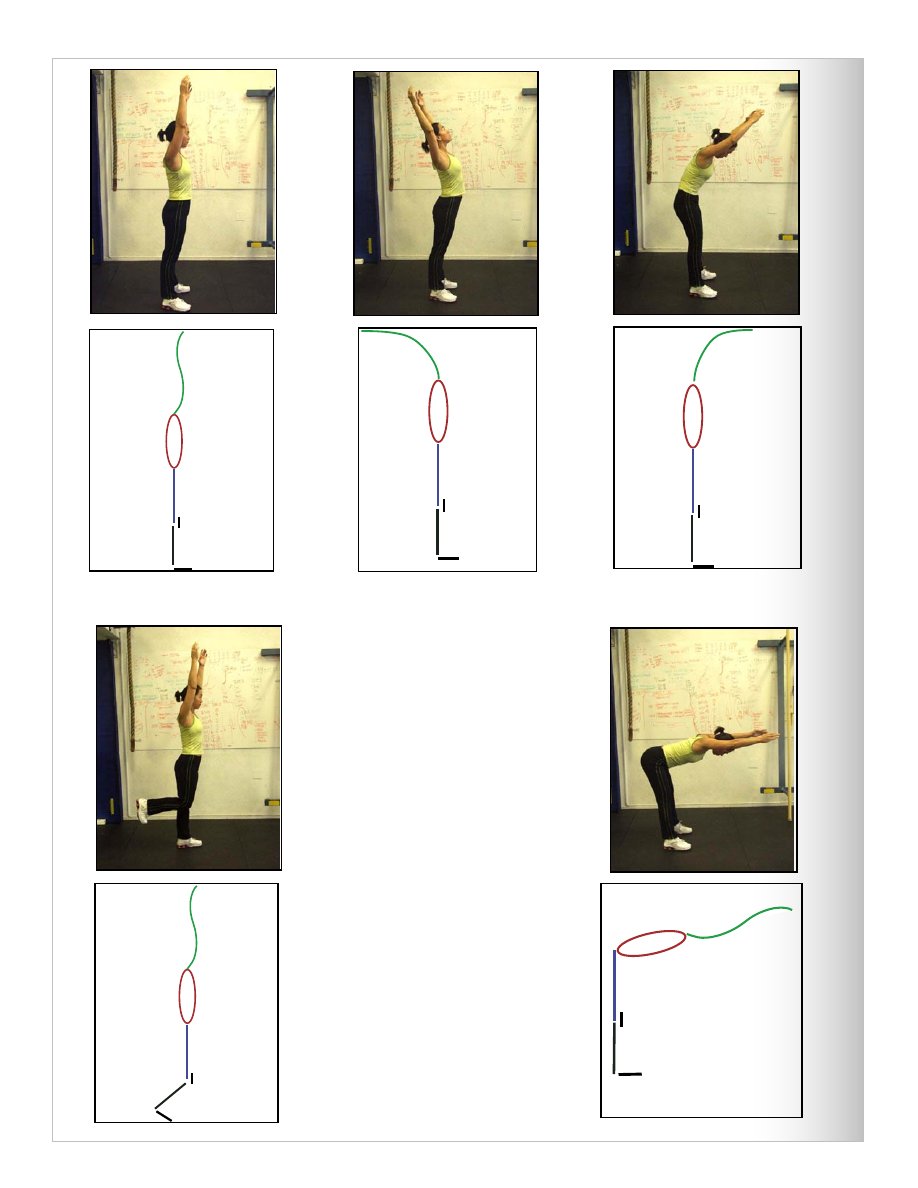

Trunk neutral, hip extension,

leg extension

Trunk extension

Trunk flexion

Leg flexion

Hip flexion

7

August 2003

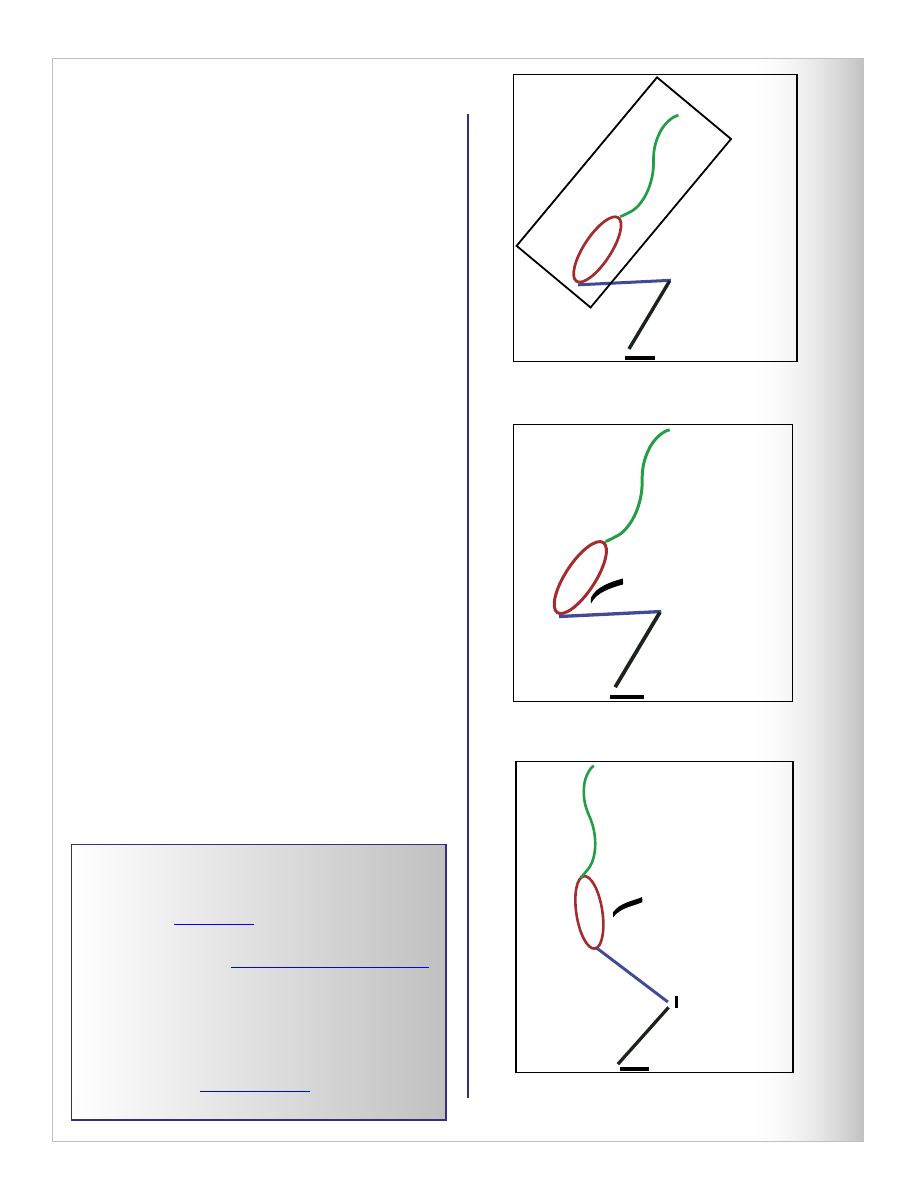

Before covering our distillation of essential biomechanics

we test our students to see if everyone can flex and extend

their knee (or “leg”), hip, spine and sacroiliac joint (or

“trunk”) on cue. When it is clear that the difference

between flexion and extension is understood at each joint

we cue for combinations of behaviors, for instance, “flex

one leg and trunk but not your hip”.

Once the joints, parts, and movements are clear we offer

these three tidbits of biomechanics:

• Functional movement generally

weds the spine to the pelvis. The SI

joint and spine were designed for

small range movement in multiple

directions. Endeavor to keep the

trunk tight and solid for running,

jumping, squatting, throwing,

cycling, etc...

• The dynamics of those movements

comes from the hip – primarily

extension. Powerful hip extension

is certainly necessary and nearly

sufficient for elite athletic capacity.

• Do not let the pelvis chase the femur

instead of the spine. We’ve referred

to this in the past as “muted hip

function” (Jan ‘03:5). We also call

it “frozen hip” because when the

pelvis chases the femur the hip angle

remains open and is consequently

powerless to extend.

Four parts, three joints, two motions, and three rules give

our athletes and us a simple but powerful lexicon and

understanding whose immediate effect is to render our

athletes at once more “coachable”. We couldn’t ask for

more.

CrossFit Journal

The CrossFit Journal is an electronically distributed magazine (emailed e-zine)

chronicling a proven method of achieving

elite fitness.

For subscription information go to:

http://www.crossfit.com/cf-info/store.html

, or

send a check or money order in the amount of $25 to:

CrossFit

P.O. Box 2769

Aptos CA 95001

Please include name, address and email address. If you have any questions

or comments send them to

. Your input will be greatly

appreciated and every email will be answered.

������ ��� ����� ����

��������

������ ������� �����

����� ����� ���� ��� ���

8

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Crossfit vol 10 Jun 2003 METABOLIC CONDITIONING

Crossfit vol 16 Dec 2003 COMMUNITY

Crossfit vol 15 Nov 2003 FOOD

Crossfit vol 10 Jun 2003 METABOLIC CONDITIONING

Crossfit vol 14 Oct 2003 TEAM WORKOUT

Crossfit vol 19 Mar 2004 WHAT IS CROSSFIT

USTAWA z dnia 12 czerwca 2003 r. o terminach zapłaty w transakcjach handlowych

Crossfit vol 3 Nov 2002 MUSCLE UP, GLYCEMIC INDEX

Vol 12 Harmonogram przeglądu 1

Brzuch i miednica 2003-2004 2 - puste, Anatomia, Anatomia, wydział lekarski

12. Drogi ruchowe, I rok, I rok, Anatomia

(12) Rozporzadzenie 1-2003 o systemie stosowania regul konkurencji, Europeistyka II rok EPG, Ćwiczen

więcej podobnych podstron