1

Introduction to Maternity,

Newborn, and Women’s

Health Nursing

unit

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 1

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 2

Contemporary Issues and

Trends in Maternal, Newborn,

and Women’s Health

Key

TERMS

abortion

certified nurse midwife

(CNM)

doula

empowerment

ethics

family-centered care

health indicators

infant mortality rate

intrauterine fetal surgery

maternal mortality rate

nurse practice acts

Learning

OBJECTIVES

After studying the chapter content, the student should be able to

accomplish the following:

1. Define the key terms.

2. Identify the current trends in health care that affect women.

3. Outline the barriers that women have in accessing health care.

4. List three women’s health care indicators and how they are being addressed.

5. Describe the nursing implications of current trends in women’s health care.

6. Discuss the role of the nurse throughout the life cycle continuum.

Key

Learning

1

chapter

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 3

wow

person’s ability to lead a fulfilling

life and to participate fully in society depends largely on

his or her health status. This is especially true for women,

who often shoulder the combined burden of child rear-

ing, family health care, and career building. To fulfill her

responsibility to her loved ones, a woman must first care

for her own personal health.

Now more than ever, nearly every health care experi-

ence involves the contribution of a nurse. From birth to

death, and every health care emergency in between, will

likely involve the presence of a nurse. A knowledgeable,

supportive, comforting nurse often results in a superior

health care experience. Skilled nursing practice depends

on a solid base of knowledge and clinical expertise deliv-

ered in a caring, holistic manner. It is imperative that

nurses use their knowledge and passion to reach out to

their patients. They must help meet every woman’s health

care needs regardless of where a woman is in her life cycle

continuum. Nurses can help their patients to live health-

ier lives by providing emotional support, comfort, infor-

mation, advice, advocacy, support, and family counseling.

This chapter presents a general overview of issues

and trends in health care with which nurses often grapple

in caring for families with children. Nurses must know

how to approach these issues in a knowledgeable and sys-

tematic way to reduce conflict and to provide profes-

sional care.

Maternal and Women’s Health

Care Perspectives

Past Trends

Centuries ago, granny midwives handled the normal

birthing process for most women. Their training was

obtained through an apprenticeship with a more experi-

enced midwife. Most doctors only participated in child-

birth in the most extreme cases of difficulty. All births

took place in the home setting.

Childbirth in colonial America was a difficult and

sometimes dangerous experience. During the 17th and

18th centuries, women giving birth died as a result of

exhaustion, dehydration, infection, hemorrhage, or sei-

zures (Lehrman, 2003). In addition to her anxieties about

pregnancy, an expectant mother was filled with apprehen-

sions about the death of her newborn child. The death of

a child during infancy was far more common than it is

today. Approximately 50% of all children died before the

age of five (Lehrman, 2003). This can be compared with

the 0.07%

infant mortality rate

of today, which is a dra-

matic improvement (World Factbook, 2003).

During the early 1900s, physicians attended about half

the births in the United States. Midwives often cared for

women who could not afford a doctor. Most women were

attracted to hospitals because these institutions offered

pain management that was not available in home births.

Natural childbirth practices advocating birth without med-

ication and focusing on relaxation techniques were intro-

duced in the 1950s. These techniques opened the door to

childbirth education classes and helped bring the father

back into the picture. Both partners were participating

in the whole family experience by taking an active role in

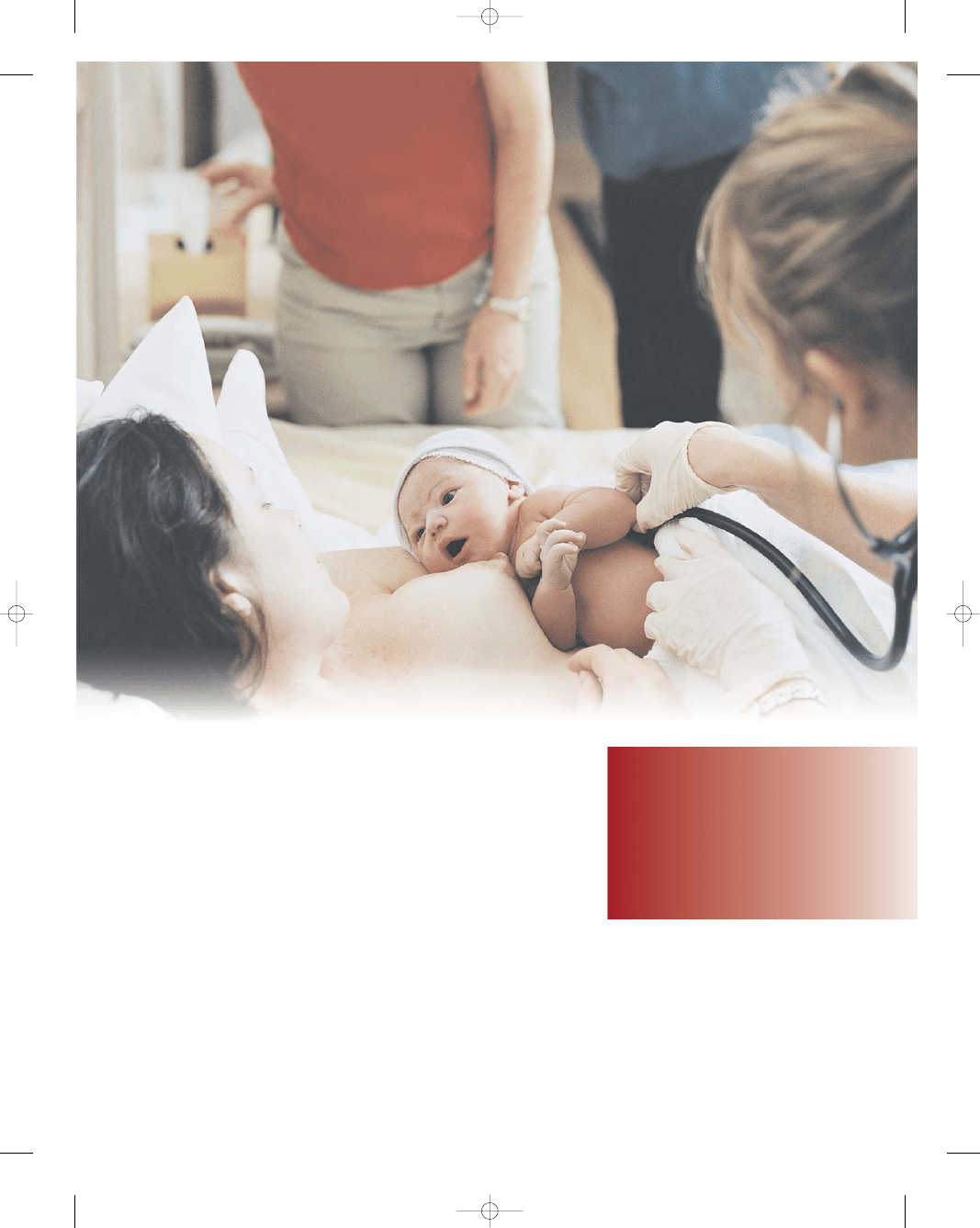

pregnancy, childbirth, and parenting (Fig. 1-1).

During the 1960s, consumer organizations formed and

advocated for family-centered maternity care (FCMC).

The International Childbirth Education Association

Being pregnant and giving birth are like crossing a narrow bridge. People can accompany

you to the bridge. They can greet you on the other side. But you walk that

bridge alone. . . .

A

A

B

●

Figure 1-1

Today, fathers and partners are welcome to

take an active role in the pregnancy and childbirth experience.

(A) Couples can participate together in childbirth education

classes. (Photo by Gus Freedman.) (B) Fathers and partners

can assist the woman throughout her labor and delivery.

(Photo by Joe Mitchell.)

4

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 4

(ICEA), the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in

Obstetrics (ASPO), and the National Association of

Parents and Professionals for Safe Alternatives in Child-

birth (NAPSAC) all stressed a strong commitment to fam-

ily values and responsibility in childbearing. In the 1970s,

female consumers and women health professionals chal-

lenged many assumptions of the obstetric system and

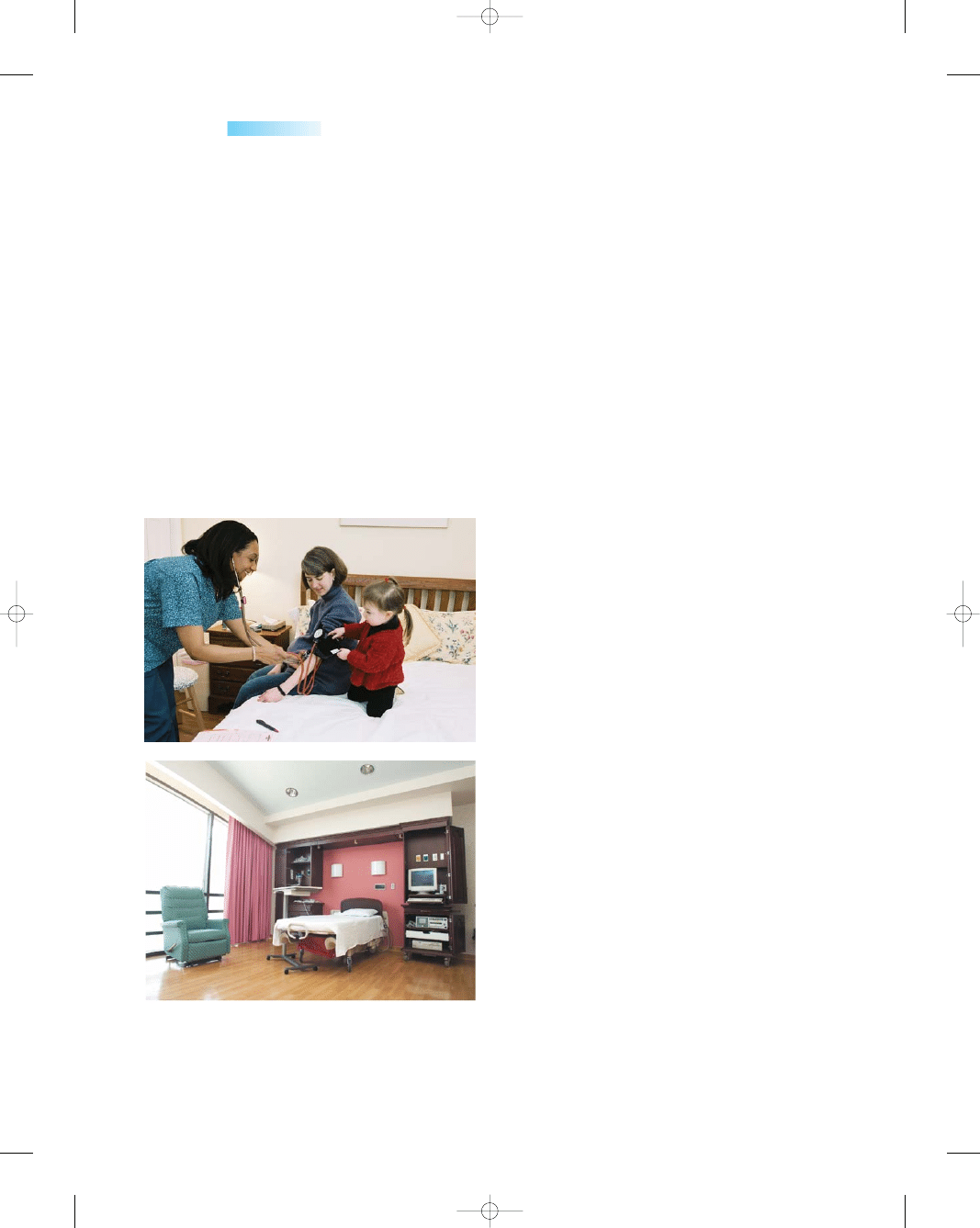

demanded new models of care delivery. From the 1980s

to the present, increased access to care for all women

(regardless of their ability to pay) and new hospital

redesigns (labor, delivery, and recovery [LDR] rooms;

and labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum [LDRP]

spaces) to keep “families together” during the childbirth

experience breathed new life into FCMC (Fig. 1-2).

Family-centered care

is the delivery of safe, sat-

isfying, quality health care that focuses on and adapts to

the physical and psychosocial needs of the family. It is a

cooperative effort of families and other caregivers that

recognizes the strength and integrity of the family. The

basic principles of family-centered care are as follows:

•

Childbirth is considered a normal, healthy event in the

life of a family.

•

Childbirth affects the entire family and relationships will

change.

•

Families are capable of making decisions about their own

care if given adequate information and professional sup-

port (Murray et al., 2002).

FCMC is based on the premise that the family is the

constant. Family members support one another well

beyond the health care provider’s brief time with them

during the childbearing process. FCMC views birth as a

normal life event, rather than a medical procedure. The

core values of FCMC that need to be integrated into all

nursing care provided to families include mutual respect

and trust of all parties, “informed choice” used by the

family,

empowerment

of the family unit, collaboration

in all decision making, and flexibility, quality, and indi-

vidualized care for all family members (Phillips, 2003).

In many ways, childbirth practices in the United

States have come full circle, as we see the return of nurse

midwives and doulas.

Certified nurse midwives

(CNMs)

have postgraduate training in the care of normal

pregnancy and delivery, and are certified by the American

College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM). A

doula

is a birth

assistant who provides quality emotional, physical, and

educational support to the woman and family during

childbirth and the postpartum period. Childbirth choices

are often based on what works best for the mother, child,

and family. Box 1-1 summarizes a time line of childbirth

in America.

Current Trends

Modern women are often faced with multiple responsi-

bilities that compete for their time and attention, includ-

ing the health of their parents, their children, and their

partner. These responsibilities may decrease a woman’s

ability to tend to her own mental and physical health

(nutrition, exercise, leisure activities, and so forth). A

woman who neglects her health may have to deal with the

consequences for the remainder of her life.

Today women are part of an evolving health care

delivery system. The cost of health care is soaring and the

federal government, insurance agencies, hospitals, and

health care providers are joining together in an attempt

to bring it under control. Several changes in the health

care arena have resulted, many of which have brought

about an increasingly complex health care system. Many

people feel “lost in the maze.”

Health care functions within the parameters of a mar-

ket setting, offering goods and services that carry cost to

health care consumers and patients. If a woman is preg-

nant, diabetic, and needs to go to an endocrinologist, she

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

5

A

B

●

Figure 1-2

Many different settings are available for

prenatal care, labor, and delivery. (A) Birthing centers and

(B) labor, delivery and recovery (LDR) rooms have inviting,

home-like atmospheres and encourage family-centered care.

(A, Photo by Gus Freedman; B, photo by Joe Mitchell.)

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 5

has very little choice except to purchase the services needed

or go without care. In the managed care environment of

health care today, the woman will need to go through her

“primary health care professional” or “gatekeeper” to

receive a referral to a specialist. Often she must trust her

primary provider to make that choice for her, instead of

making that decision on her own.

The best managed care principles value a compre-

hensive approach with a focus on prevention, early inter-

vention, and continuity of care. The goal is to consider

the merit of services, procedures, and treatments in view

of the resources available, thus the gatekeeper role, which

ensures that care is timely and necessary. In a perfect

world, all women would receive necessary quality care

throughout their lives, but we don’t live in the perfect

managed care world. With cost-cutting strategies, there

are many implications for women:

•

Decreased length of hospital stay for newborns and

high-risk neonates, which is often met by increased at-

home care given by women as caretakers

•

Loss of continuity of care and an establishment of a

trusting relationship with her health care provider when

the insurance plan does not cover the same provider she

may have been receiving care from for years

•

Potential prohibition of OB/GYN physicians from mak-

ing referrals for specialists if they are not classified as pri-

mary physicians (gatekeepers)

•

Restricting clinical judgment that impacts quality and

individualization of care, which may potentially increase

mother and infant morbidity by dictating length of stay

in the hospital when more observation and nursing care

are needed

•

Restricting the number and type of diagnostic studies

ordered by the health care provider, which may jeopar-

6

Unit 1

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH NURSING

1700s

Men did not attend births, because it was consid-

ered indecent.

Women faced birth, not with joy and ecstasy, but

with fear of death.

Female midwives attended the majority of all

births at home.

1800s

There is a shift from using midwives to doctors

among middle class women.

The word obstetrician was formed from the Latin,

meaning “to stand before.”

Puerperal (childbed) fever was occurring in

epidemic proportions.

Louis Pasteur demonstrated that streptococci

were the major cause of puerperal fever that

was killing mothers after delivery.

The first cesarean section was performed in

Boston in 1894.

The x-ray was developed in 1895 and was used to

asses pelvic size for birthing purposes

(Feldhusen 2003).

1900s

Twilight sleep (a heavy dose of narcotics and

amnesiacs) was used on women during child-

birth in the United States.

The United States was 17th out of 20 nations in

infant mortality rates.

Fifty to 75% of all women gave birth in hospitals

by 1940.

Nurseries were started because moms could not

care for their baby for several days after receiv-

ing chloroform gas.

Dr. Grantley Dick–Reed (1933) wrote a book

entitled Childbirth Without Fear that reduced

the “fear–tension–pain” cycle women experi-

enced during labor and birth.

Dr. Fernand Lamaze (1984) wrote a book entitled

Painless Childbirth: The Lamaze Method that

advocated distraction and relaxation techniques

to minimize the perception of pain.

Amniocentesis is first performed to assess fetal

growth in 1966.

In the 1970s the cesarean section rate was about

5%. By 1990 it rose to 24%, where it stands

currently (Martin, 2002).

The 1970s and 1980s see a growing trend to return

birthing back to the basics—nonmedicated,

nonintervening childbirth.

In the late 1900s, freestanding birthing centers—

LDRPs—were designed, and the number of

home births began to increase.

2000s

One in four women undergo a surgical birth

(cesarean).

CNMs once again assist couples at home, in hos-

pitals, or in freestanding facilities with natural

childbirths. Research shows that midwives are

the safest birth attendants for most women,

with lower infant mortality and maternal rates,

and fewer invasive interventions such as epi-

siotomies and cesareans (Keefe 2003).

Childbirth classes of every flavor abound in most

communities.

According to the latest available data, the United

States ranks 21st in the world in maternal

deaths. The maternal mortality rate is approxi-

mately 7 in 1000 live births.

According to the latest available data, the United

States ranks 27th in the world in infant mortality

rates. The infant mortality rate is approximately

7 in 1000 live births (United Nations, 2003).

BOX 1-1

CHILDBIRTH IN AMERICA: A TIME LINE

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 6

dize the health and well-being of the newborn and

mother, and precludes the parents from making decisions

about future pregnancy events (Youngkin & Davis, 2004)

Other trends in the health care system include

•

Changing demographics—an aging population

•

Economic forces that affect resources

•

Profound growth of technology and information

•

Proliferation of unlicensed assistive personnel provid-

ing health care

•

Communications and cultural issues associated with

the increasingly diverse needs of multicultural patients

•

Shortages of trained health care professionals

•

Movement of health care away from acute settings into

the community

Currently, the problem surmounting all health care

considerations is cost. Although cost containment is impor-

tant to restrain spiraling health care spending, costs and

efforts to contain them should not affect the quality or

safety of care delivered. The old saying that “an ounce of

prevention is worth a pound of cure” has been shown to

lower costs significantly. Mammograms, cervical cancer

screenings, prenatal care, and smoking cessation programs

are a few examples that yield positive outcomes and reduce

overall health care costs. Using technologic advances to

diagnose and treat breast cancer early positively saves lives

as well as fiscal resources.

Nurses can be leaders in providing quality care within

a limited-resource environment by stressing to the women

for whom they care the importance of making healthy

lifestyle and food choices, seeking early interventions for

minor problems before they become major ones, and edu-

cating themselves about health-related issues that affect

them so they can select the best option for themselves

and their families. Prevention services and health edu-

cation are the cornerstones of delivering quality women’s

health care.

These are just a few of the changes in the health care

system that consumers face when they need services.

These dramatic changes present a significant opportunity

for the nursing profession. Nurses who clearly articulate

their role in this changing environment will be able to help

their patients to navigate this increasingly complicated

health care system.

Future Trends/Needs

for Women’s Health

Based on our changing demographics concerning age,

ethnic background, education, workforce participation,

and booming childbearing statistics, the future trend for

women’s health will need to

•

Broaden the focus on women’s health, not just during

pregnancy, but throughout the entire life cycle

•

Integrate women’s and perinatal health services to com-

pensate for poor coordination of services by increasing

numbers of OB/GYNs being designated primary care

providers

•

Expand comprehensive, integrated programs and ser-

vices addressing women’s unique needs across their

life span

•

Offer better provider education about the consequences

of chronic health problems as well as enlighten all women

about better lifestyle choices to prevent the progression of

chronic conditions

•

Promote social policies that ensure economic security

and health care insurance coverage for women

•

Recognize sociocultural differences that affect women’s

caregiving roles, domestic violence, access to health infor-

mation, lifestyle preferences, autonomy to make health

decisions, and learning/motivation for health prevention

and promotion activities

•

Focus scientific research for more specific drug treat-

ments for breast cancer, osteoporosis, autoimmune dis-

eases, and menopause

•

Develop better diagnostic procedures for heart disease,

diabetes, arthritis, lupus, inflammatory diseases, and

detection of genetic disorders earlier

•

Support health care educational programs to increase

entry of diverse-culture students to provide a broad

range of women’s health services

Health Care Indicators

Health indicators

are used to measure the health of

the nation. They are global in nature and provide each

country with guidelines to assess their own health sta-

tus. General global health indicators include infant mor-

tality rate, at-risk birth weight, potential years of life

lost, life expectancy, disability-free life expectancy, and

self-rated health status (Osei et al., 2003). The lead-

ing health indicators reflect the major health concerns in

the United States at the beginning of the 21st century.

These indicators were selected on the basis of their abil-

ity to motivate action, the availability of data to measure

progress, and their importance as public health issues

(Healthy People 2010). The current leading health indi-

cators include

•

Physical activity

•

Overweight and obesity

•

Tobacco use

•

Substance abuse

•

Responsible sexual behavior

•

Mental health

•

Injury and violence

•

Environmental quality

•

Immunization

•

Access to health care (Healthy People 2010)

The objectives of Healthy People 2010 are categorized

according to the health indicators. Healthy People 2010 is

a broad-based, collaborative federal and state initiative that

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

7

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 7

has set national disease prevention and health promotion

objectives to be achieved by the end of the decade. The

initiative has two goals: to increase the quality and years

of healthy life and to eliminate health disparities among

Americans. An example of health disparity exists in peo-

ple with disabilities. Just because these individuals were

born with an impairing condition or have experienced

a disability or injury that has long-term consequences

does not negate their need for health promotion and dis-

ease prevention. In fact, their need for health-promoting

behaviors is accentuated. Many women with disabling

conditions such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple

sclerosis, or osteoporosis do not view themselves as

disabled, despite immense physical limitations. Nurses

need to remember that wellness is the lens of their self-

perception. The accompanying Healthy People 2010

box highlights national health goals for maternal and

infant health.

Mortality Rates

The federal government has pledged to improve maternal–

child care outcomes and thus reduce the statistics of mor-

tality rates for both women and children. The

maternal

mortality rate

counts the number of deaths from any

cause during the pregnancy cycle per 100,000 live births.

In the United States, the maternal mortality rate is 7.5. The

infant mortality rate counts the number of deaths of infants

younger than one year of age per 1000 live births. In the

United States, the infant mortality rate is 7.0 (Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2004, National

Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2005).

During the past several decades, mortality and

morbidity have dramatically decreased as a result of an

increased emphasis on hygiene, good nutrition, exercise,

and prenatal care for all women. However, women and

infants are still experiencing complications at significant

rates. The United States is one of the most medically and

technologically advanced nations and has the highest

per-capita spending on health care in the world, yet cur-

rent mortality rates in the United States indicate the

need for continued improvement.

A few facts might help present a clearer picture:

•

The current maternal mortality rate is approximately 7.5

maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (CDC, 2004).

•

The current infant mortality rate is approximately 7.0

infant deaths per 1,000 live births (CDC, 2004;

NCHS, 2005).

•

Two to three women die in the United States every day

from pregnancy complications, and more than 30% of

pregnant women (1.2 million women annually) expe-

rience some type of illness or injury during childbirth

(CDC, 2004).

•

The United States ranks 21st (below 20 other countries)

in rates of maternal deaths (deaths per 100,000 live

births).

•

The United States ranks 27th (below 26 other countries

with a population of at least 2.5 million) in rates of infant

deaths (deaths per 100,000 live births; United Nations,

2003). One reason cited for the high infant mortality rate

in the United States is the high rate of very-low-birth-

weight births in the country relative to other developed

countries (NCHS, 2005).

•

Most pregnancy-related complications are preventable.

The most common are ectopic pregnancy, preterm labor,

hemorrhage, emboli, hypertension, infection, stroke, dia-

betes, and heart disease.

•

The leading causes of pregnancy-related mortality for the

years 1991 to 1999 (the last years for which data are avail-

able) are embolism (20%), hemorrhage (17%), preg-

nancy-related hypertension (16%), and infection (13%;

CDC, 2003).

•

More than half of all infant deaths in 2002 were attribut-

able to five leading causes: congenital malformations

(20%), disorders relating to short gestation and unspeci-

8

Unit 1

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH NURSING

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

HEALTHY PEOPLE

2010

National Health Goals—Maternal and Infant Health

Goal:

Reduce fetal and infant deaths.

Goal:

Reduce maternal deaths.

Goal:

Reduce maternal illness and complications

resulting from pregnancy.

Goal:

Increase the proportion of pregnant women

who receive early and adequate prenatal care.

Goal:

Increase the proportion of pregnant women

who attend a series of prepared childbirth classes.

Goal:

Increase the proportion of very low-birth

weight (VLBW) infants born at level III hospitals or

subspecialty perinatal centers.

Goal:

Reduce cesarean births among low-risk

(full-term, singleton, vertex presentation) women.

Goal:

Reduce low birth weight (LBW) and VLBW.

Goal:

Reduce preterm births.

Goal:

Increase the proportion of mothers who

achieve a recommended weight gain during their

pregnancies.

Goal:

Increase the percentage of healthy, full-term

infants who are laid down to sleep on their backs.

Goal:

Reduce the occurrence of developmental

disabilities.

Goal:

Reduce the occurrence of spina bifida and

other neural tube defects (NTDs).

Goal:

Increase the proportion of pregnancies

begun with an optimum folic acid level.

Goal:

Increase abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes,

and illicit drugs among pregnant women.

Goal:

Reduce the occurrence of fetal alcohol

syndrome (FAS).

Goal:

Increase the proportion of mothers who

breast-feed their babies.

Goal:

Ensure appropriate newborn bloodspot

screening, follow-up testing, and referral to services.

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 8

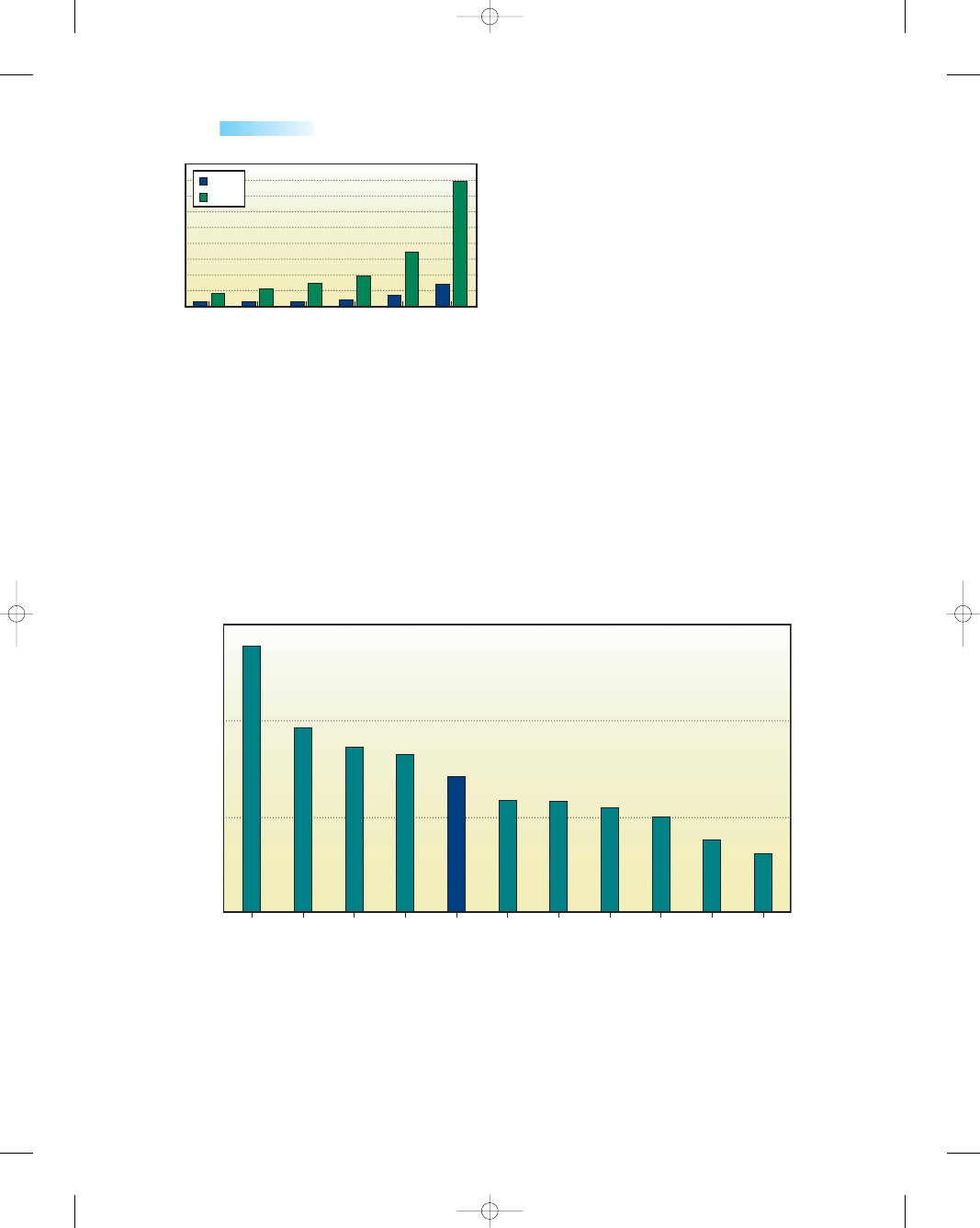

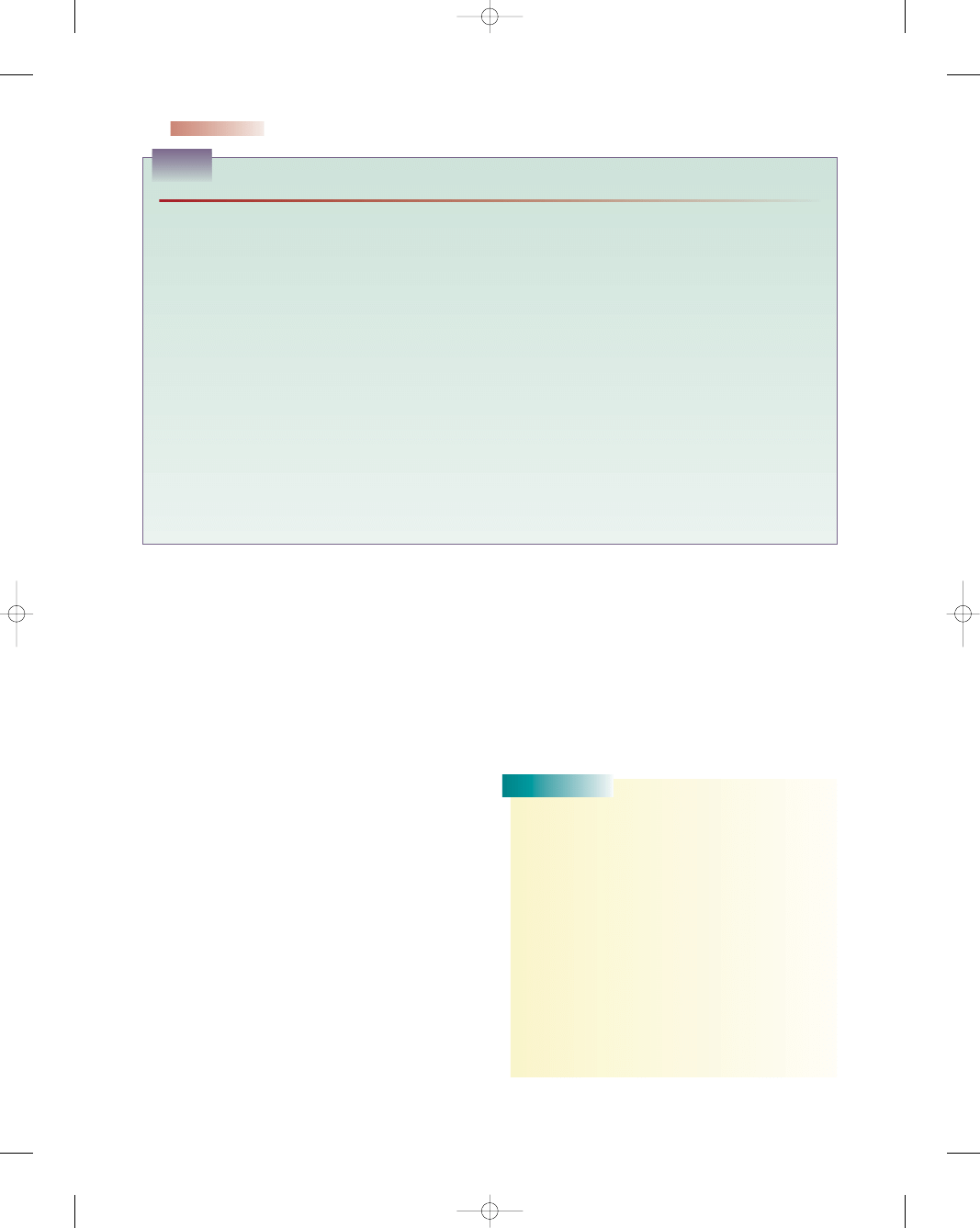

•

Infant mortality rates are higher for African-American,

Latin-American, and Native American babies. The rate

for African-American babies is twice that of white babies

(Keefe, 2003; Fig. 1-4).

Why is there such disparity within the United States?

The problem is multifaceted, but lack of care during preg-

nancy is a major contributing factor to a poor outcome.

Prenatal care is well known to prevent complications of

pregnancy and to support the birth of healthy infants.

Unfortunately, not all women are able to receive the same

quality and quantity of health care during a pregnancy.

More than 40% of African-American, Native American,

and Latino women do not obtain prenatal care during

their first trimester of pregnancy (Condon, 2004).

Several of the risk factors that contribute to high mor-

tality rates can be lessened or prevented with good precon-

ception and prenatal care. First, preconception screening

and counseling offer an opportunity to identify maternal

risk factors before pregnancy begins. Examples include

daily folic acid consumption (a protective factor) and alco-

hol use (a risk factor). During preconception counseling,

health care providers can also refer women for medical and

psychosocial or support services for any risk factors identi-

fied. Counseling should be culturally appropriate and lin-

guistically proficient.

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

9

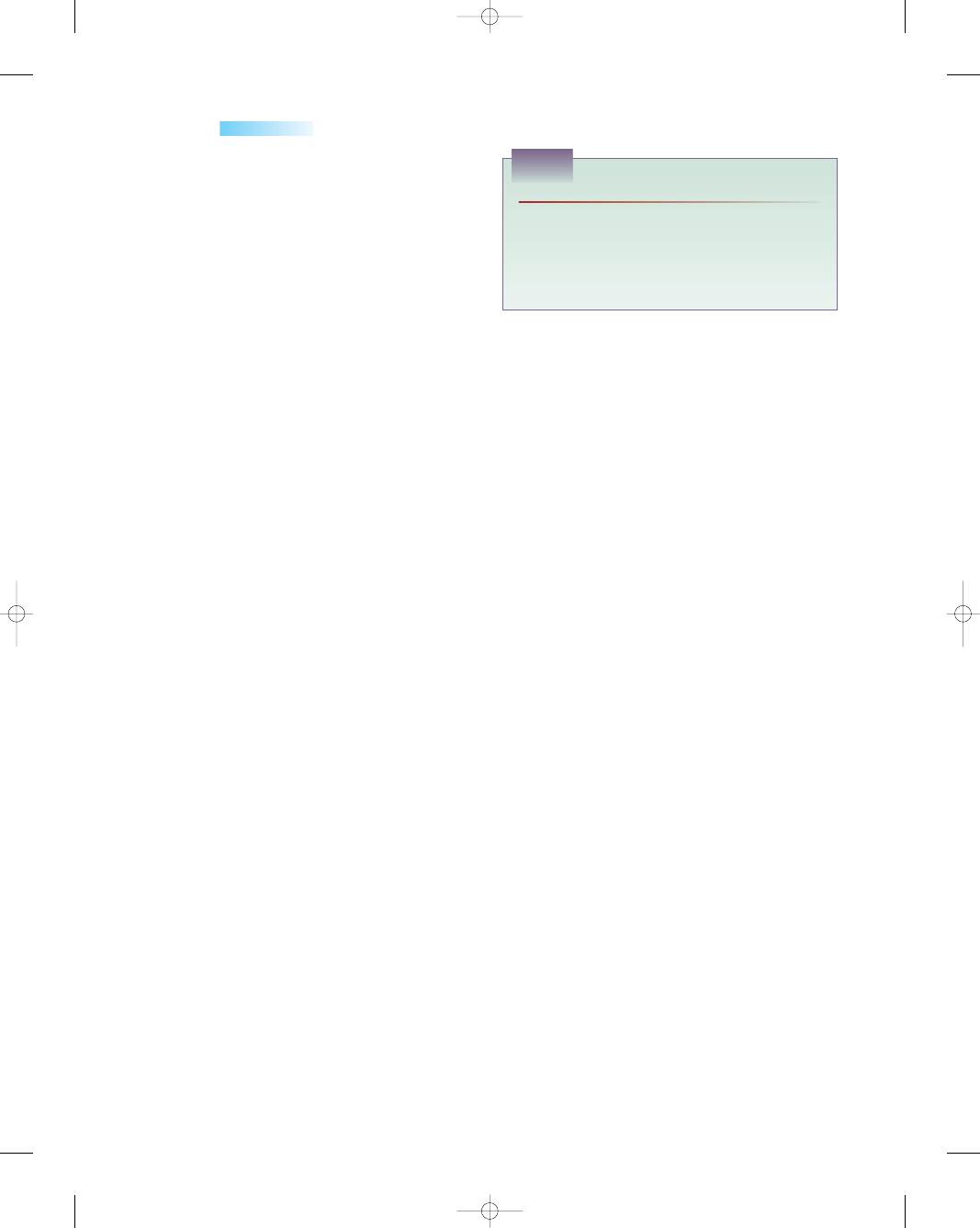

20–24

25–29

Age group (yrs)

30–34

35–39

≥

40

≤

19

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

White

Black

Ratio

* Deaths per 100,000 live births.

●

Figure 1-3

Pregnancy-related mortality ratios by race and

age, United States, 1991–1999. (Retrieved May 2005 from

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5202a1.htm.)

Race/Ethnicity

Black

non-

Hispanic

Hawaiian

†

Japanese

†

Chinese

†

Cuban

§

Filipino

†

American

Indian

†

Mexican

§

Puerto

Rican

§

0

5

10

15

13.9

9.6

8.6

8.2

7.0

5.8

5.7

5.4

4.9

3.7

3.0

Ratio

Total U.S. White,

non-

Hispanic

* Per 1,000 live births.

†

Can include persons of Hispanic and non-Hispanic origin.

§

Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

●

Figure 1-4

Infant mortality rates by selected racial/ethnic populations—United States,

2002. (Retrieved May 2005 from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/

mm5405a5.htm.)

fied LBW (17%), sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS;

8%), newborns affected by maternal complications of

pregnancy (6%), and newborns affected by complications

of placenta, cord, and membranes (4%) (Martin et al.,

2005).

•

The maternal mortality and morbidity rates for African-

American women have been three to four times higher

than for whites (Chang, 2003; Fig. 1-3).

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 9

Prenatal visits offer an opportunity to provide infor-

mation about the adverse effects of substance use and

serve as a vehicle for referrals to treatment services. The

use of timely, high-quality prenatal care can help to pre-

vent poor birth outcomes and improve maternal health by

identifying women who are at particularly high risk, and

then can be used to take steps to reduce risks, such as the

risk of high blood pressure or diabetes. Interventions tar-

geted at prevention and cessation of substance use during

pregnancy may be helpful in further reducing the rate of

preterm delivery and LBW. Continued promotion of folic

acid intake can help to reduce the rate of NTDs.

In addition, providing access to quality prenatal care

for all pregnant women without ability to pay will help

reduce the mortality rates tremendously. Access to family

planning services can also play a major role in preventing

maternal deaths by reducing health risks associated with

unplanned pregnancy.

Maternal mortality rates are nearly four times higher

for women of color than for white women (Keefe, 2003).

Researchers do not entirely understand what accounts for

these disparities, but some suspected causes of higher

maternal mortality rates for minority women include low

socioeconomic status, limited or no insurance coverage,

bias among health care providers (which may foster dis-

trust), and quality of care available in the community.

Language and legal barriers may also add to the various

reasons why some immigrant women do not receive good

prenatal care.

After birth, other health promotion strategies can sig-

nificantly improve an infant’s health and chances of sur-

vival. Breast-feeding has been shown to reduce rates of

infection in infants and to improve long-term maternal

health. Emphasizing to mothers that they should place

their infants on their backs to sleep will help reduce the

incidence of SIDS. Encouraging mothers to join support

groups to prevent postpartum depression and gain assis-

tance with sound child-rearing practices will help toward

improving the health of both mothers and their infants.

The CDC has called the disparity in maternal mortal-

ity rates in women of color and white women “one of the

largest racial disparities among public health indicators”

(CDC, 1999, p. 493). They have called for more research

and monitoring to understand and address the racial dis-

parities, along with increased funding for prenatal and post-

partum care. Not enough is known about the causes of

racial disparities in maternal and infant health, so addi-

tional research is needed to identify causes and design ini-

tiatives to reduce these disparities. In addition, the CDC is

calling on Congress to expand programs to provide pre-

conception and prenatal care to underserved women to

address the racial disparities.

The Health Resources and Services Administration

(HRSA)’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB)

has primary federal responsibility for improving the health

of mothers and children in the United States. More than

27 million infants, children, and pregnant women are

served by an MCHB program annually (Dyck et al., 2003).

A few of their programs and initiatives to improve the

health of mothers, infants, and children and to reduce

mortality rates are described in Box 1-2.

The Report Card on Women’s Health

Women of today face not only diseases of genetic origin

but also diseases that arise from poor personal habits as

well. Even though women represent 51% of the popula-

tion, only recently have researchers and the medical com-

munity focused attention on the special health needs

of women. One significant study that was published in

August 2000 assessed the overall health of women at the

state and national level. It identified an urgent need to

improve women’s access to health insurance and health

care services, place a stronger emphasis on prevention,

and invest in more research on women’s health (National

Women’s Law Center [NWLC] et al., 2000).

The study identified several health care indicators that

measure women’s access to health care services. It mea-

sured the degree to which women receive preventive health

care and engage in health-promoting activities (Box 1-3).

The report card gave the nation an overall grade of

“unsatisfactory,” and not a single state received a grade

of “satisfactory.” Among the other substandard findings

were the following:

•

No state has focused enough attention on preventive

measures, such as smoking cessation, exercise, nutri-

tion, and screening for diseases.

10

Unit 1

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH NURSING

• Healthy Start—through community outreach, home

visitation, and a network of support services, targets

the poorest neighborhoods where the likelihood of

maternal and infant mortality and LBW is highest.

• Health and Human Services (HHS) Interagency Council

on Low Birth Weight—has been established to promote

multidisciplinary research on LBW and preterm births,

scientific exchange, policy initiatives, and collaboration

among HHS agencies.

• Food fortification—along with the national campaign to

educate women about the preventive benefits of taking

folic acid, has resulted in decreases in the prevalence

of spina bifida and anencephaly.

• Increased research—concerning genetic, environmental,

and behavioral factors that have an influence on

pregnancy outcomes for mother and infant is being

undertaken.

• CDC’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System

(PRAMS)—is an ongoing, state-specific surveillance

system designed to identify and monitor select maternal

behaviors and experiences before, during, and after

pregnancy. PRAMS surveillance now covers approxi-

mately two thirds of all US births (Dyck et al., 2003).

BOX 1-2

MCHB PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 10

•

Too many women lack health insurance coverage.

Nationally, nearly one in seven women (14%) have no

health insurance.

•

No state has adequately addressed women’s health

needs in the areas of reproductive health, mental health,

and violence against women.

•

Limited research has been done on health conditions

that primarily affect women and that affect women dif-

ferently than men (NWLC et al., 2000).

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

Poor health habits affect all women. Smoking, drug abuse,

high cholesterol, and obesity lead to high mortality and

morbidity rates in our nation. CVD is the number one

cause of death of women, regardless of racial or ethnic

group. Approximately 500,000 women die annually in the

United States of CVD, equaling a rate of about one death

per minute (Alexander et al., 2004) Women who endure a

heart attack are more likely than men to die and oftentimes

are more difficult to diagnose than men because of their

vague and varied symptoms. Heart disease is still thought

of as a “man’s disease” and thus is not considered as a

diagnosis when a woman presents to the emergency room.

The common perception held by many nurses that

CVD is a man’s disease could cost women their lives.

Many nurses believe erroneously that only men need to

worry about heart attacks and stroke, but CVD is an equal-

opportunity killer. Consider these myths:

•

Breast cancer kills more women than CVD.

•

CVD is more deadly in men.

•

Men and women experience the same symptoms.

Now examine the facts about CVD:

•

CVD is the number one killer of women and stroke is

number three.

•

One in 10 women age 45 to 64 has some form of CVD.

•

CVD is more challenging to diagnose in women than

men.

•

One of two American women dies of CVD, whereas 1 in

30 dies of breast cancer.

•

Approximately 35% of heart attacks in women go unno-

ticed or unreported.

•

Health care professionals do not take CVD symptoms

seriously in women.

•

Heart attack is twice as deadly in women as men

(American Heart Association [AHA], 2004).

Nurses need to take heed and look beyond the obvi-

ous “crushing chest pain” textbook symptom that heralds

a heart attack in men, because women present much dif-

ferently and the diagnosis is missed if CVD is not on their

radar screen of possibilities. Look for the following risk

factors in women:

•

Cigarette smoking

•

Smoking and use of oral contraceptives or hormone

replacement therapy

•

Obesity

•

Consuming a diet high in saturated fats

•

Stress

•

Sedentary lifestyle

•

Hypertension

•

Hyperlipidemia

•

Strong family history

•

Diabetes mellitus

•

Postmenopausal

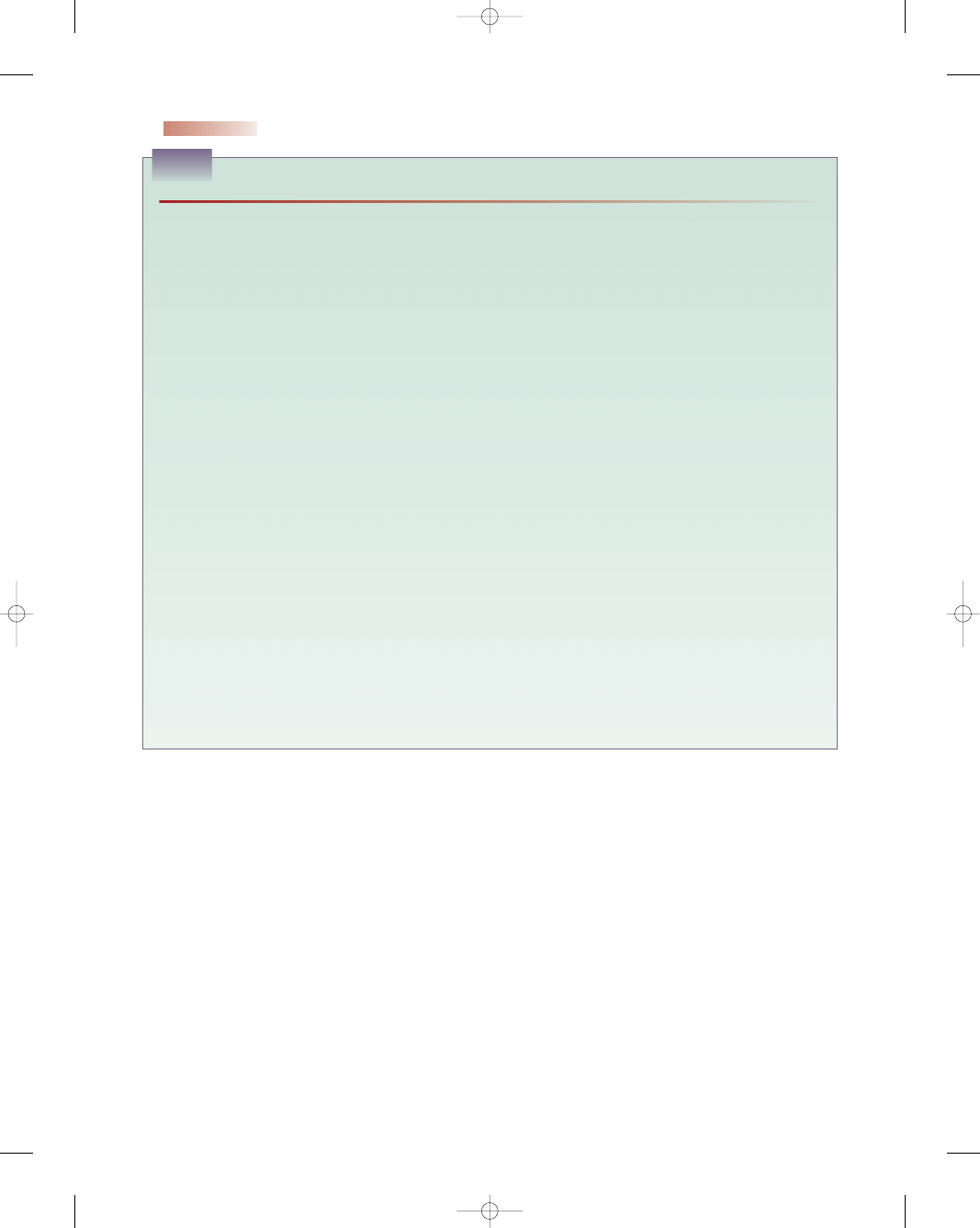

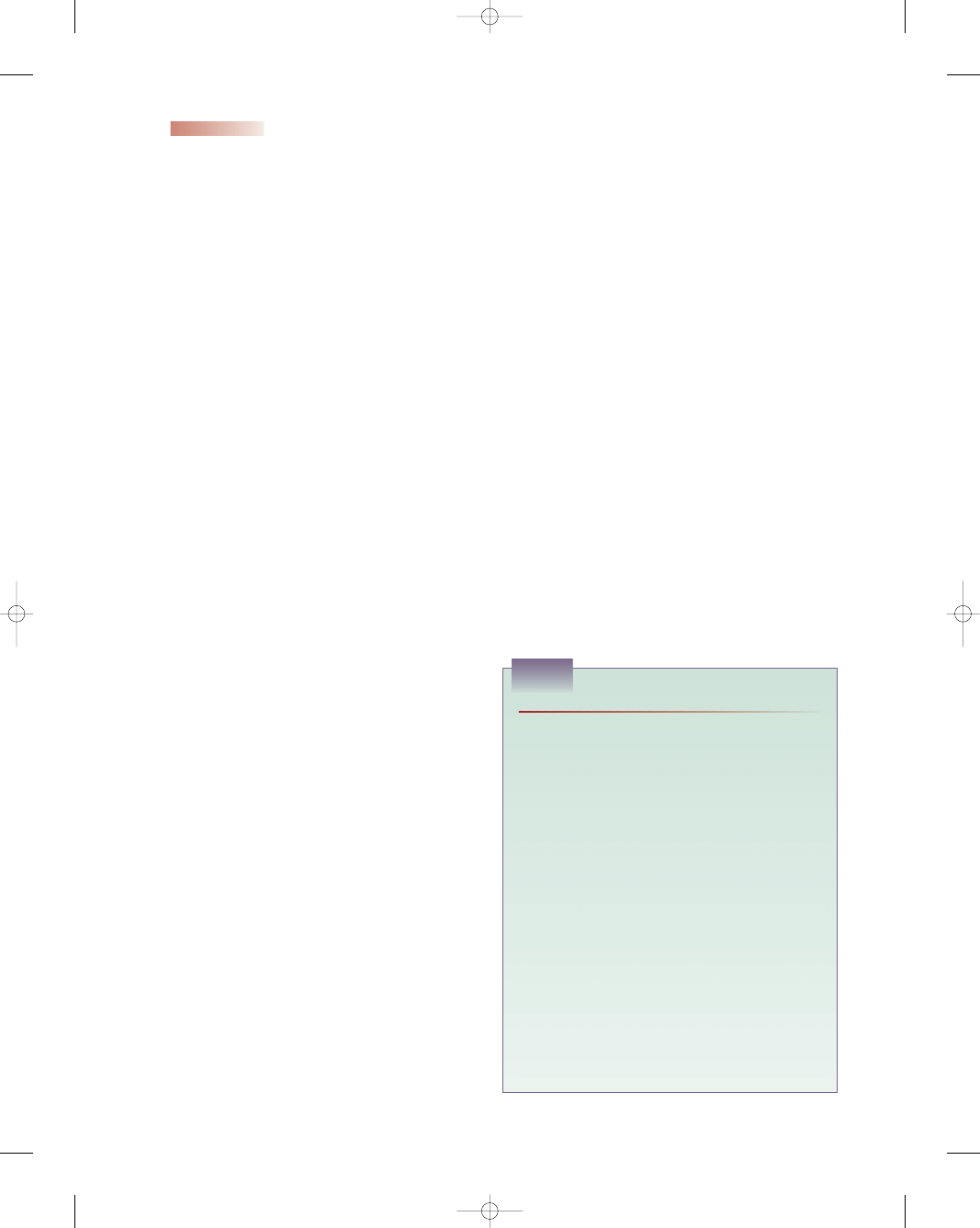

Figure 1-5 presents a sample health risk assessor to help

nurses and patients assess the patient’s risk of heart attack.

Consider CVD as a possibility in women who present

with any of the following clinical symptoms: chest dis-

comfort in the center of the chest that goes away and

comes back (can be described as pressure, squeezing,

or feeling of fullness); discomfort in one or both arms

or shoulders, the back, neck, jaw, or stomach; shortness

of breath; nausea; lightheadedness; breaking out in a cold

sweat; paleness; atypical abdominal pain; and unexplained

fatigue (AHA, 2004).

Prevention efforts to reduce the number victims of

CVD in women include

•

A low-cholesterol, low-fat diet

•

Aspirin therapy and treatment of hypertension

•

Daily exercise

•

Achieving an ideal weight

•

Smoking cessation measures

•

Cholesterol-lowering agents

•

Stress management (Condon, 2004)

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

11

• Lung cancer death rate

• Diabetes

• Heart disease death rate

• Binge drinking

• High school completion

• Poverty

• Wage gap

• Rate of AIDS

• Maternal mortality rate

• Rate of Chlamydia infection

• Breast cancer death rate

• Heart disease death rate

• Smoking

• Being overweight

• No physical activity during leisure time

• Eating five fruits and vegetables daily

• Colorectal screening

• Mammograms

• Pap smears

• First trimester prenatal care

• Access to health insurance

BOX 1-3

THE NATIONAL INDICATORS OF WOMEN’S HEALTH

Adapted from National Women’s Law Center, FOCUS/University of

Pennsylvania, the Lewin Group. (2000). Making the grade on women’s

health: a national state-by-state report card. Washington, DC: National

Women’s Law Center.

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 11

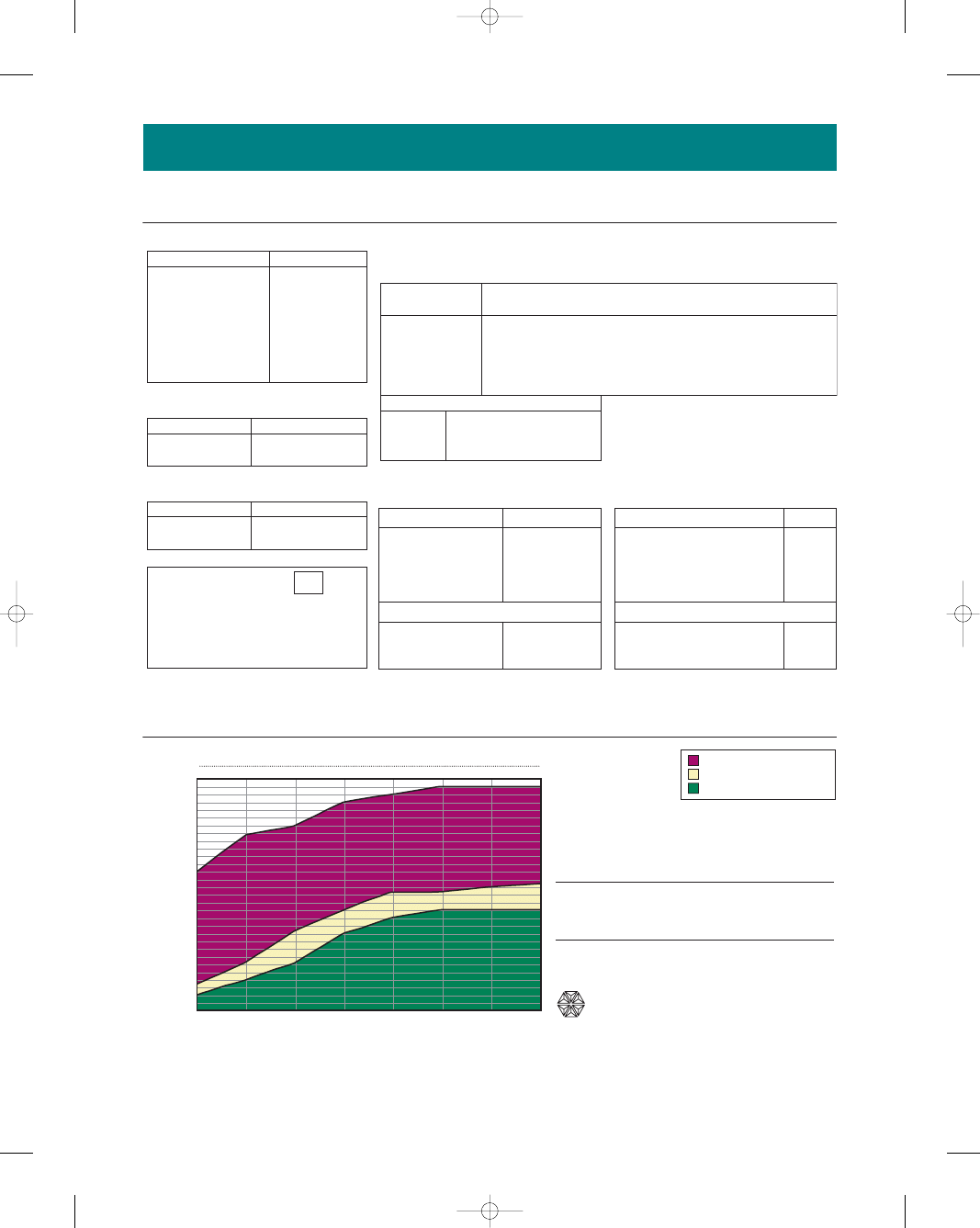

65–69

70+

D3-F091-7-99

© 1999 Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton NJ 08543

60–64

55–59

Score on Risk Assessment

50–54

45–49

40–44

Below are some easy-to-complete questions about your health and lifestyle that will help you assess your risk of a heart

attack. The questions are designed to encourage discussion with your healthcare professional. Circle your points for each

risk factor. Add them up and place your total points in the box. Then use the graph below to determine your risk.

The red zone indicates a higher than average risk for a

heart attack. The yellow zone indicates an average risk

for a heart attack. It is desirable for you to be in the

lower or green zone, which indicates a lower than

average risk of a heart attack.

1. HOW OLD ARE YOU?

2. DO YOU SMOKE?

35 – 39

120 – 129

160 – 199

35 – 44

45 – 49

50 – 59

200 – 239

240 – 279

280 and over

60 and over

Low

Low

Use the Heart Risk Assessor as a general guide. If you have already had a heart attack or have heart disease, your heart attack risk is

significantly higher. Only your healthcare professional can evaluate your risk and recommend treatment plans to reduce your risk.

If you don’t know your cholesterol level or blood pressure, ask your healthcare professional if your levels should be checked.

Normal

High

High

Average

Low

High

Average

5. WHAT IS YOUR TOTAL CHOLESTEROL

LEVEL?

Systolic

Less than 120

Less than 160

Less than 35

130 – 139

140 – 159

160 or more

40 – 44

45 – 49

50 – 54

55 – 59

60 – 64

65 – 69

70 and over

Age

Points

Points

Points

Points

Points

HDL (good) cholesterol (mg/dL)

Total cholesterol (mg/dL)

Don’t know, but I have been told it is:

Don’t know, but I have been told it is:

Don’t know, but I have been told it is:

–4

0

Heart Risk Assessor — Women

3

6

7

8

8

8

Yes

No

Yes

No

2

4

0

0

4

0

3. DO YOU HAVE DIABETES?

Now determine your risk. To do this, use

the graph. Find your score on the left,

run your finger across the line to match

your age, and place an X at this point.

Score (Total Points)

4. WHAT IS YOUR BLOOD PRESSURE?

Look up your points on the table below. Your systolic pressure (higher number) is on the

left and your diastolic pressure (the lower number) is along the top.

Diastolic

79 or less

90 – 99

100 or more

85 – 89

80 – 84

–3

–3

–2

–2

0

0

1

1

5

5

1

1

1

3

3

0

0

0

2

2

3

0

0

0

2

3

0

0

0

2

3

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

6. WHAT IS YOUR HDL (GOOD)

CHOLESTEROL LEVEL?

–3

–3

2

Heart Attack Risk Groups, Women Age 35 and Older

Heart Attack

Risk*

35–39

Age Group

0

5

10

20

26

–4

Higher Than Average Risk

Lower Than Average Risk

Average Risk

If you have already had a heart attack or have heart disease,

your heart attack risk is significantly higher. Only your health-

care professional can evaluate your risk and recommend

treatment plans to reduce your risk.

* Risk estimates were derived from the results of the Framingham

Heart Study

Provided as an educational service from

Bristol-Myers Squibb Company

●

Figure 1-5

Sample Health Risk Assessor form to help detect the risk for heart attack in

women. (Used with permission from Bristol-Myers-Squibb Company.)

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 12

Cancer

Cancer falls as the second leading cause of death among

women (Grantham, 2002). Women have a one in three

lifetime risk of developing cancer, and one out of every four

deaths is from cancer (Alexander et al., 2004). Although

much attention is focused on cancer of the reproductive

system, lung cancer is the number one killer of women.

This is largely the result of the higher rates of smoking by

women as well as the effects of second-hand smoke. Lung

cancer has no early symptoms, making early detection

almost impossible. Because of this, lung cancer has the

lowest survival rate of any cancer. More than 90% of peo-

ple who get lung cancer die of the disease (Breslin & Lucas,

2003).

Breast cancer occurs in one in every eight women in a

lifetime, with more than 183,000 women diagnosed annu-

ally in the United States. It is the most common malig-

nancy in women, and second only to lung cancer as a cause

of cancer mortality in women (American Cancer Society

[ACS], 2004). Although a positive family history of breast

cancer, aging, and irregularities in the menstrual cycle at

an early age are major risk factors, others include excess

weight, not having children, oral contraceptive use, exces-

sive alcohol consumption, a high-fat diet, and long-term

use of hormone replacement therapy (ACS, 2003). Early

detection and treatment appear to be the best chance for a

cure, and reducing the risk of cancer by decreasing avoid-

able risks continues to be the best preventive plan.

Improving Women’s Health

What can we do as a nation to improve the health of

women? There is no single answer to address the multi-

tude of issues that were identified in the state-to-state

study. Women’s health is a complex issue, and no single

policy is going to change the overall dismal state ratings.

Some policies may include

•

Expand health care to the uninsured

•

Overcome barriers to accessing care

•

Address the issue of violence toward women

•

Focus on wellness and prevention education programs

Although progress in science and technology have

helped reduce the incidence and improve survival rates in

several diseases, women’s health issues continue to have

an impact on our society. By eliminating or decreasing

some of the risk factors and causes for prevalent diseases

and illnesses, society and science could solve certain

chronic health problems. By focusing on the causes and

effects of particular illnesses, many women’s health issues

of today could be resolved.

Social Issues

Many social issues influence health care, including poverty,

limited access to health care (especially prenatal care), and

violence against women. These issues and possible inter-

ventions as they relate to nursing care are discussed next.

Poverty and Women

Despite many global economic gains during the last cen-

tury, poverty continues to grow, and the gap between rich

and poor is widening. Major gaps continue between the

economic opportunities and status afforded to women and

those offered to men. A disproportionate share of the bur-

den of poverty rests on women’s shoulders and under-

mines their health. For example:

•

70% of the 1.2 billion people living in poverty are female.

•

Iron deficiency anemia, which is a direct result of malnu-

trition and poverty, affects twice the number of women

compared with men.

•

Half a million women die needlessly from pregnancy-

related complications annually, the causes of which

are exacerbated by issues of poverty and geographic

remoteness.

•

On average, women are paid 30% to 40% less than

men for comparable work (World Health Organization

[WHO], 2000).

Poverty, particularly for women, is more than mone-

tary deficiency. Women continue to lag behind men in

control of cash, credit, and collateral. Other forms of

impoverishment may include deficiencies in literacy, edu-

cation, skills, employment opportunities, mobility, and

political representation, as well as pressures on their avail-

able time and energy linked to their role responsibilities.

These poverty factors may diminish a woman’s develop-

ment and affect her health status (WHO, 2000).

Barriers to Accessing Health Care

Women are the major consumers of health care services,

in many cases negotiating not only their own care, but

also that of their family members. Compared with men,

women have a greater rate of health problems, longer life

spans, and more significant reproductive health needs.

Their access to care is often complicated by their dis-

proportionately lower incomes and greater responsibil-

ities, juggling work and family concerns.

The Kaiser Women’s Health Study (Salganicoff et al.,

2002) surveyed approximately 4000 women between the

ages of 18 to 64 and found that their health care needs

were not being met, especially for women of color, those

who are poor, and those who are uninsured.

For many, affordability of care is a major concern. A

significant portion of women cannot afford to go to the

doctor and fill their drug prescriptions, even when they

have insurance coverage. Many health insurance plans do

not include prescription coverage and thus the person

must pay “out of pocket” (Box 1-4).

According to the Kaiser Women’s Health Study

(Salganicoff et al., 2002), women also have issues about

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

13

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 13

the quality of care they receive. More than one in five

women (22%) expressed concerns about the quality of

care compared with 17% of men. This issue was a partic-

ular problem for women in fair or poor health (40%).

Almost one in five women (18%) changed providers

within the past five years because of dissatisfaction with

care and concerns over quality—twice the rate of men

(Salganicoff et al., 2002). Because access to health care is

often unstable, relationships with health care providers are

often short lived, resulting in care that can be spotty and

disjointed (Salganicoff et al., 2002).

The value of prenatal care has been extensively doc-

umented in the literature as being equated with better

pregnancy outcomes. The proportion of women begin-

ning prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy

remained stable at 83.2% in 2000 (US Department of

Health and Human Services, 2002). However, finances,

transportation, language and/or cultural barriers, clinic

hours, and poor attitudes of the health care workers often

limit women’s access to prenatal care.

Financial Barriers

Financial barriers are one of the most important factors

that limit care. Many women have limited or no health

care and simply cannot afford the insurance. Although

Medicaid covers prenatal care in most states, the paper-

work and enrollment process is so burdensome that many

women do not register.

Transportation

Transportation to and from appointments can be challeng-

ing for patients who do not drive or own a car or cannot use

public transportation. The frequency of prenatal health

care visits can be quite burdensome, compounding the

transportation issue. The transportation issue becomes

even more difficult if the woman has small children that she

must take along with her. These challenges can prevent the

pregnant patient from making her scheduled appointments.

14

Unit 1

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH NURSING

• Low-income women were twice as likely (23%) as those with

higher incomes (10%) to have fair or poor health status.

• Low-income women 45 to 64 years old reported

49% had arthritis

41% had hypertension

32% had anxiety or depression

• Latinos were the most likely to report poor health (29%).

• African-American women were most likely to report

activity limitations (16%).

• African-American women (45–64 years old) reported

hypertension (57%) and arthritis (40%).

• One in six Latino and African-American women

(45–64 years old) were diagnosed with diabetes during

the past five years.

• One in three low-income women have no health insurance.

• Fifty-seven percent of uninsured women work either

full- or part-time.

• Thirty-seven percent of Latino women are without

insurance coverage.

• One in seven women reported their insurance plans did not

provide adequate coverage to meet their health care needs

• One half of low-income women delayed or never

received treatment because of lack of approval for

treatment or tests.

• Seventeen percent of women did not have a regular

health provider; 46% of uninsured women did not have

a regular provider; and 31% of Latinos and 24% of low-

income women lacked a regular provider.

• Seventeen percent of women of color reported they had

difficulty communicating with their provider and left the

office.

• Latino (31%) and uninsured (24%) women experienced

access problems and barriers to care, and were least likely

to have had a doctor visit within the past year.

• Women on Medicaid (40%), Latino women (38%),

and African-American women (27%) were more likely

to rely on hospital clinics and health centers for health

care.

• Uninsured women were consistently less likely than

women with private coverage to obtain any recom-

mended preventive screening tests (Salganicoff et al.,

2002).

BOX 1-4

THE KAISER WOMEN’S HEALTH STUDY HIGHLIGHTS

Consider

THIS!

I was a 17-year-old pregnant migrant worker needing pre-

natal care. Although my English wasn’t good, I was able

to show the receptionist my “big belly” and ask for ser-

vices. All the receptionist seemed interested in was a social

security number and health insurance—neither of which I

had. She proceeded to ask me personal questions con-

cerning who the father was and commented on how

young I looked. The receptionist then “ordered” me in a

loud voice to sit down and wait for an answer by someone

in the back, but never contacted anyone that I could see.

It seemed to me like all eyes were on me while I found an

empty seat in the waiting room. After sitting there quietly

for over an hour without any attention or answer, I left.

Thoughts:

Why did she leave before receiving any

health care service? What must she have been feel-

ing during her wait? Would you come back to this

clinic again? Why or why not?

Consider

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 14

Language Barriers

Language is how people communicate with each other to

increase their understanding or knowledge base. If a

health care worker cannot speak the same language as the

client or does not have a trained interpreter available, a

barrier is created. This language barrier might prevent the

client from accessing prenatal care that could increase the

chances affecting the pregnancy outcome. Frequently,

communication between people who speak the same

language can be misinterpreted.

Cultural Barriers

Culture is the sum of the beliefs and values that are

learned, shared, and transmitted from generation to gen-

eration by a particular group. Cultural beliefs and values

vary among different groups, and nurses must be aware,

understand, and respect cultural beliefs different from

their own. Nurses who feel their cultural values and pat-

tern of behavior are superior (ethnocentrism) frequently

set up barriers that inhibit diverse cultures from receiving

prenatal health care.

Clinic Hours

Clinic hours must meet the needs of the patients, not the

health care providers who work there. Evening and/or

weekend service hours might be needed to meet the work-

ing client’s schedule. It is important to evaluate the avail-

ability and accessibility of the offered service.

Poor Attitudes of Health Care Workers

Some health care workers exhibit negative attitudes toward

poor and/or culturally diverse families, which could pro-

hibit women from seeking health care. Long delays, hur-

ried examinations, and rude comments by staff might

increase a patient’s level of discomfort with the health care

team and may discourage return appointments.

Violence and Women

Violence against women is a major health concern—one

that costs the health care system millions of dollars and

thousands of lives. Violence affects women of all ages,

ethnic backgrounds, races, educational levels, socioeco-

nomic levels, and all walks of life. Nurses often come in

contact with abused women, but fail to identify, acknowl-

edge, or report the abuse. Pregnancy is often a time when

physical abuse starts or escalates, resulting in poorer out-

comes for the mother and the baby. Assessing for abuse

carries the responsibility of listening for and following up

on a possible incidence of abuse. Nurses serve their

clients best by not trying to rescue them, but by helping

them build on their strengths, providing support, and

thereby empowering them to help themselves. All nurses

need to include “RADAR” in every client visit (Box 1-5).

For a thorough discussion of violence and women, see

Chapter 9.

Legal and Ethical Issues

Law and

ethics

are interrelated and affect the entire

nursing practice. Professional nurses must understand

the limits in their scope of practice, standards of care,

institutional or agency policies, and state laws. Every

nurse is responsible for knowing current information

regarding ethics and laws related to their practice. Three

sources of rules and regulations provide guidelines for

safe and legal nursing practice:

1. State

Nurse Practice Acts

2. Standards of Care set by the American Nurses Asso-

ciation (ANA)

3. Policies and procedures set by the employer

Ethics provide rules and principles that can be used

for resolving ethical dilemmas. The ANA recently revised

their code of ethics (ANA, 2001), which should guide

nurses in their ethical practice. Ethical decisions in mater-

nal health frequently involve maternal–fetal conflict,

in which the status of the fetus as a person is still being

debated. In maternity care, the ethical assumption is made

that the pregnant woman’s decision regarding medical

intervention will be beneficial to both the expectant mother

and her fetus. This is not always the case when the mother’s

needs or wishes may injure the fetus. Abortion, sub-

stance abuse, and fetal therapy are examples that might

bring about ethical conflict to all involved in the decisions

that influence that family unit.

Throughout the world, effects of violence, abuse, as

well as rape confront nurses daily in their practice settings.

Women are the primary victims of these “human crimes.”

Clearly, these acts harm women, and nurses need to look

to the ethical principle of nonmaleficence to justify action.

The principle of nonmaleficence asserts an obliga-

tion not to inflict harm on others. It is usually translated

as, “First, do no harm.” Once nurses are convinced that

these abusive acts violate the principle of nonmaleficence,

they can turn to their own ANA code of ethics for guid-

ance (ANA, 2001).

According to the ANA code of ethics, nurses have an

ethical duty to respect the dignity and human rights of

other persons and to treat them with compassion regard-

less of health condition, ethnicity, or life style (ANA, 2001,

p. 7). In addition, the nurse is to “promote, advocate, and

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

15

R–Routinely screen every patient for abuse.

A–Ask direct, supportive, and nonjudgmental questions.

D–Document all findings.

A–Assess your client’s safety.

R–Review options and provide referrals.

BOX 1-5

RADAR

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 15

strive to protect the health and safety of the patient”

(ANA, 2001, p. 12). Ethical codes demand action and

mandate nurses do something about violation of human

rights, not only for the abused women by reporting it, but

also on the professional, local, and national levels.

Human abuse, wherever it occurs, diminishes every

human being. The challenge to all nurses is what they

can do to make a difference in abused women’s lives and

to reduce its incidence. The right ethical choice is to

move beyond ethical beliefs to ethical action (Silva &

Ludwick, 2002).

Abortion

Abortion was a volatile legal, social, and political issue even

before the Roe v. Wade decision to legalize abortion by the

Supreme Court in 1973. The term

abortion

describes

the willful or purposeful termination of a pregnancy, usu-

ally within the first three months. Each year, an estimated

46 million abortions occur worldwide. In 2000, 1.3 mil-

lion abortions took place in the United States. Forty-nine

percent of pregnancies among American women are

unintended, and 50% of them are terminated by abortion

(Alan Guttmacher Institute, 2004). The highest per-

centages of reported abortions in 2000 were for women

who were younger than 25 years of age (52%), white

(57%), and unmarried (81%). In 2000, the racial char-

acteristics of women obtaining abortions were 57%

white, 46% black, and 7% other (Whitcomb, 2004).

Abortion is one of the most common procedures per-

formed in the United States. It has become a hotly

debated political issue that separates people into two

camps: pro-choice and pro-life. The pro-choice group

supports the right of any woman to make decisions about

her reproductive functions on the basis or her own moral

and ethical beliefs. The pro-life group feels strongly that

abortion is killing and deprives the fetus of the basic right

to life. Both sides will continue to deliberate this very

emotional issue for years to come.

Today there are several modalities available to ter-

minate a pregnancy: dilation and curettage, vacuum

extraction, or medical termination by ingesting the med-

ications methotrexate/misoprostol (Cytotec) or mifepris-

tone (RU 486). When a woman chooses to terminate her

pregnancy, she now has options, depending on how far the

pregnancy has developed. For a surgical intervention she

has up to 14 weeks’ gestation; for a medical intervention

she has up to 9 weeks’ gestation (Goss, 2002). Regardless

of the method a woman chooses, all procedures require

that women have emotional support, a stable environment

in which to recover, and nonjudgmental care throughout.

Abortion is a complex issue, and the controversy lies

not only in the public arena, but many nurses struggle

with the conflict between their personal convictions and

their professional duty. Nurses are taught to be support-

ive patient advocates and interact with a nonjudgmental

attitude under all circumstances, but nurses are not

immune to having their own personal and political views,

and they may be very different from the patients’. Nurses

need to clarify their own personal values and beliefs on

this issue and be able to provide nonbiased care before

assuming responsibility for clients who might be in a

position to consider abortion. Their decision to care for

or refuse to care for the patient affects staff unity, influences

staffing decisions, and challenges the ethical concept of

duty (Marek, 2004).

The ANA’s Code of Ethics for Nurses upholds the

nurse’s right to refuse to care for a patient undergoing

an abortion if the nurse ethically opposes the procedure

(ANA, 2001). Nurses need to make their values and

beliefs known to their managers before the situation occurs

so alternate staffing arrangements can be made. Open

communication and acceptance of personal beliefs of one

another can promote a comfortable working environment.

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse can cause fetal injury and thus has legal

and ethical implications. In some instances, courts have

issued jail sentences when pregnant women caused harm

to their fetuses. Many state laws require reporting evidence

of prenatal drug exposure and might charge pregnant

women with negligence and endangerment of a child. The

punitive approach to fetal injury raises the question of how

much government control is appropriate and how much

should be allowed in the interest of child safety (Box 1-6).

Fetal Therapy

Intrauterine fetal surgery

is a procedure that involves

opening the uterus during pregnancy, performing a sur-

gery, and replacing the fetus in the uterus. The risks to the

fetus and the mother are both great, but may be used to

correct anatomic lesions (London et al., 2003). Some argue

that medical technology should not interfere with nature

and thus this intervention should not take place. Others

would vote for the better quality of life for the child made

possible with the surgical intervention. For many people,

these are ethical debates and intellectual discussions. For

nurses, these procedures may be part of a daily routine.

Nurses do play an important supportive role in caring

and advocating for their patients and their families. As

medical science expands the use of technology, frequent

ethical situations will surface that test a nurse’s belief sys-

tem. Encouraging open discussions to address potential

emotional issues and differences in opinion among staff

members is healthy and opens the door for increasing tol-

erance of differing points of view. In caring for patients

undergoing ethically sensitive procedures, the nurse can

•

Offer objective information to the woman and her family

•

Recognize and validate the woman’s myriad feelings

•

Project a nonjudgmental attitude

•

Respect the decision made by the family

•

Assess the family’s emotional support system

•

Ask questions using reflection to ascertain feelings

•

Use appropriate touch to demonstrate support

•

Make appropriate referrals for continuity of care

16

Unit 1

INTRODUCTION TO MATERNITY, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH NURSING

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 16

Nursing Management

The health care system is intricately woven into the polit-

ical and social structure of society. Nurses who under-

stand social, legal, and ethical health care issues can play

an active role in meeting the health care needs of women.

Nurses striving to address these complex concerns might

want to consider the following suggestions:

1. Be aware of your own beliefs, attitudes, and miscon-

ceptions.

2. Examine and debate your feelings to validate or change

them.

3. Stay current about the impact of social/legal/ethical

issues on the family.

4. Be sensitive to different beliefs and values from your

own.

5. Stay knowledgeable about community resources for

all issues.

6. Offer your expertise on these issues to community

groups.

7. Become a client advocate by ensuring clients know all

their options.

8. Maintain your expertise in clinical practice to avoid

litigation.

9. Speak to your legislators about your opinion regarding

political action.

It is imperative that nurses take a proactive role in

advocating and empowering their clients. Nurses need to

enable women to increase control over the determinants

of health to help improve their health status. A woman

may become empowered when she develops skills not

only to cope with her environment, but also when she

works to change it. Nurses can take on that mentoring

role with women and their families, and help improve

their health outcome.

K E Y C O N C E P T S

●

Nurses need to evoke empowerment in their patients

by enabling, permitting, and investing them with the

power of knowledge.

●

Family-centered care is the delivery of safe, satisfy-

ing, quality health care that focuses on and adapts to

the physical and psychosocial needs of the family.

●

Child-birthing practices evolved from female atten-

dants at home to male physicians delivering babies

in hospitals with the use of analgesia by the early

1900s.

●

Today, freestanding birthing centers, LDRP units,

and home births are the norm.

●

Changing demographics, economics, growth of tech-

nology and information, an increasing multicultural

patient base, and a shortage of health care workforce

to meet demands have made the health care system

difficult to navigate.

●

Women with health problems, who need health care

services the most, often have the hardest time get-

ting care because of plan coverage policies, afford-

ability concerns, and limited transportation to

access that service.

●

Healthy People 2010 is a broad-based collaborative

federal and state initiative that has set national dis-

ease prevention and health promotion objectives to

be achieved by the end of the decade.

●

All states need to address disease prevention and

health promotion to make a difference in the health

status of our nation.

●

Some of the social issues affecting women’s health

care include poverty, access to health care (especially

prenatal care), and violence.

●

Every nurse is responsible for knowing current

information regarding ethics and laws related to

their practice.

Chapter 1

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES AND TRENDS IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN, AND WOMEN’S HEALTH

17

In 1992, a South Carolina court sent Cornelia Whitner,

34, who had used cocaine while pregnant, to jail for eight

years because she violated state laws regarding child

abuse and neglect. According to the court, she should

have known that cocaine use would result in the birth

of a damaged baby; therefore, she had to be punished

(Lester 1999). Ms. Whitner is an African-American

woman who was born and raised in South Carolina.

When her youngest son was born she was arrested. A test

indicated that he had been exposed to cocaine during her

pregnancy. Ms. Whitner was never counseled about her

substance abuse problem during her pregnancy and was

never offered treatment as a way to avoid arrest. When

she was indicted, there was not a single inpatient residen-

tial drug treatment program in the entire state designed

to treat pregnant drug users (Anderson 2000).

Based on the advice of her court-appointed attorney,

Ms. Whitner pled guilty to the charge of child abuse.

At her guilty plea and sentencing hearing, Ms. Whitner

admitted that she was chemically dependent and

requested help. Although Ms. Whitner and her attorney

emphasized both the need and the desire for treatment,

the court sentenced her to eight years in prison.

Author’s Note: The public’s concern for the welfare

of the child is often expressed as anger at the mother.

As a result, policy makers tend to punish these women

with jail sentences or removal of their children from

their custody. Research shows that treatment for drug

addictions is effective. The federal government spends

millions annually on services for drug-exposed children

in school. If that were spent on early intervention, we

could prevent the children’s deficits from occurring.

But to do this, we must first accept that substance

abuse by pregnant women is similar to other treatable

health problems. We must remove the societal stigma

associated with drug use and advocate treatment for

these women. Substance abuse should be viewed as a

sickness, not a crime.

BOX 1-6

PREGNANT, HOOKED, AND BOOKED

10681-01_UT1-Ch01.qxd 6/19/07 2:54 PM Page 17

●

State nurse practice acts, standards of care, and

agency policies and procedures are three categories

of safeguards that determine the law’s view of

nursing practice. The recently revised Code of Ethics

for Nurses by the ANA should act as an ethical guide

for the practice of nursing.

●

The nurse’s role in advocating for women’s health

must encompass local, state, and national issues that

influence access to care and research.

References

Alexander, L. L., LaRosa, J. H., Bader, H., Garfield, S. (2004). New

dimensions in women’s health (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and

Bartlett Publishers.

American Cancer Society. (2004). Breast cancer facts and figures.

[Online] Available at www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0.asp.

American Cancer Society. (2005). What are the risk factors for breast

cancer? Cancer Reference Information. [Online] Available at

www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_2X_What_are_

the_risk_factors_for_breast_cancer_5.asp?sitearea

=.

American Heart Association. (2005). Cardiovascular disease and

women. [Online] Available at www.americanheart.org.

American Nurses Association. (2001). Code of ethics for nurses with inter-

pretive statements. Washington, DC: American Nurses Publishing.

Anderson, W. (2000). Letter to President and CEO of NAACP. South

Carolina Advocates for Pregnant Women (SCAPW). [Online]

Available at http://scapw.org/NAACPltr.htm.

Breslin, E. T., & Lucas, V. A. (2003). Women’s health nursing: toward

evidence-based practice. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2004). Safe motherhood:

promoting health for women before, during and after pregnancy.

Atlanta: CDC, Division of Reproductive Health.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Fact sheet: preg-

nancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991–1993.

[Online] Available at www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/

fs030220.htm. Accessed May 2005.