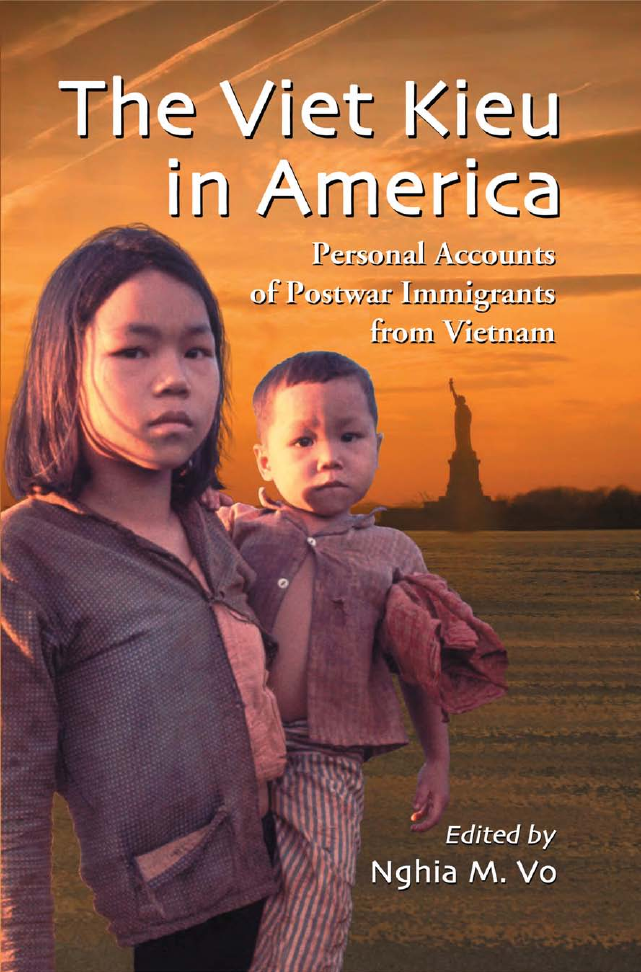

The Viet Kieu in America

A

LSO BY

N

GHIA

M. V

O AND FROM

M

C

F

ARLAND

The Vietnamese Boat People, 1954 and 1975–1992

(2006)

The Bamboo Gulag: Political Imprisonment

in Communist Vietnam (2004)

The Viet Kieu

in America

Personal Accounts of Postwar

Immigrants from Vietnam

E

DITED BY

N

GHIA

M. V

O

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

C

ATALOGUING

-

IN

-P

UBLICATION

D

ATA

The Viet Kieu in America : personal accounts of postwar

immigrants from Vietnam / edited by Nghia M. Vo.

p.

cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7864-4470-0

softcover : 50# alkaline paper

1. Vietnamese Americans — Social conditions.

2. Vietnamese

Americans — Cultural assimilation.

3. Refugees — United States —

History — 20th century.

4. Vietnamese Americans — Biography.

5. Refugees — United States — Biography.

6. Refugees — Vietnam —

Biography.

I. Vo, Nghia M., 1947–

E184.V53V53

2009

973'.00495922 — dc22

2009029677

British Library cataloguing data are available

©2009 Nghia M. Vo. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying

or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover photographs ©2009 Shutterstock

Manufactured in the United States of America

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To the Vietnamese-Americans and

Allied Forces who have fought

for freedom in Vietnam and to the

Vietnamese who have suffered in

silence under the communist regime.

This page intentionally left blank

Table of Contents

Introduction

1

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

1. The Lotus Pond

Nghia M. Vo

13

2. Remembering Saigon

Nghia M. Vo

29

3. The Vietnam War: Snapshots

Chat V. Dang

38

4. A Pilgrim

Nghia M. Vo

46

II. O

PPRESSION AND

E

SCAPE

5. My Life as a Zombie

Thien M. Ngo

65

6. Anatomy of an Escape

Theresa C. Trask

74

7. The Guava Tree

Anh Hai

86

8. The So-Called Reeducation Camp

Trong T. Ngo

94

9. The Lady in Black

Dieu Hien

101

10. A Second Chance

Chau Dinh An

110

11. The Wish

Thanh Cuc

119

12. My April

Thach N. Truong

127

III. S

TRUGGLE

, H

EALING AND

R

EMEMBRANCE

13. Shadow of the Past

Mai Lien

133

14. A Refugee’s Life

Hien V. Ho

138

15. Guam, the Transit Island

Nghia M. Vo

157

16. I Left My Heart in ... Saigon

Nghia M. Vo

165

17. April 30th

Thach N. Truong

173

vii

IV. T

HE

P

RESENT

18. A Love Affair

Christina Vo

179

19. Little Saigon, Westminster, California

Nghia M. Vo

183

20. The Journey Home

Hieu V. Ho

191

21. On Searching

Christina Vo

195

22. On Being a Viet Kieu

Nghia M. Vo

199

Epilogue

208

Chapter Notes

217

Suggested Reading

225

Index

227

viii

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

Introduction

The Viet Kieu, or overseas Vietnamese, came to the United States

shortly after the end of the Vietnam War (1975). Within three short

decades, they have acquired social visibility through their hard work and

business dealings. They form large ethnic commercial enclaves in major

U.S. cities with their distinctive pho restaurants, nail salons, realty agen-

cies, food and video stores, as well as other businesses. They also make

their presence felt in the computer and financial industries. Nguyen,

Pham, Le, Tran and so on are ubiquitous names in telephone directo-

ries. While many hold doctoral degrees in sciences and medicine from

U.S. universities, some have entered the show business, political, and

sports arenas. Although a few Vietnamese-Americans have been elected

state representatives in California and Texas, Anh Cao on December 7,

2008, became the first to be elected to the U.S. Congress by defeating

the nine-term incumbent William J. Jefferson in a district that is 60 per-

cent black.

1

The purpose of this book is to retrace the lives of some of these

immigrants — the second largest refugee group in the U.S.— from the

war-torn Vietnam to the peaceful U.S. with the goal of understanding

the reasons for their presence in this country. Although no two lives are

similar, they all share many representative features that will be discussed

throughout this book and especially in the chapter “On Being a Viet

Kieu.”

Although they arrived as war refugees — the largest diaspora in mod-

ern history — the fact that they came in different ways, by different routes

and at different periods gives their experiences a varied and complex

1

flavor. Some arrived by sea and others by air; some in 1975 and others

in the 1990s. Some came straight from Vietnam right after the war while

others languished for years in concentration camps or Asian refugee

camps; some encountered minimal problems during their escapes while

others faced insurmountable ordeals before landing in the U.S. and other

western countries. Though the basic causes of their escapes — commu-

nist oppression, loss of human rights and religious freedom, economic

loss — were similar, each experience was unique.

In this book, the Viet Kieu describe their personal experiences of

the war, their old country, their escape, and their new American homes.

They share details of their lives — some intimate, others banal — as they

look back at the two decades of war in Vietnam and the three decades

they have spent in this country. Past remembrances differ from one per-

son to another. Some talk mostly about the past while others focus essen-

tially on the present. The common thread is the repercussions of the long

and tumultuous war on their lives up until now. They have either wit-

nessed or experienced different phases of the war and post-war years:

(1) peace and war in Vietnam; (2) oppression that led them to escape;

(3) laborious struggles in the new lands while trying to heal their wounds;

and (4) the present. The book is therefore divided into these four main

sections. Some overlap in the histories is inevitable.

Some of the people in this book were officers in the Armed Forces

of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), some were artists and doctors who

went through the daunting post-war reeducation camps, while others

were housewives and middle-aged women who suffered throughout the

war and made new lives in the U.S. One was a midwife. One person was

born after the war (“A Love Affair”). The majority come from South and

central Vietnam. These are people from all walks of life. Their experi-

ences form a kaleidoscope through which we can analyze their views and

feelings about the society they lived in. Although their perspectives vary,

they offer a rare view of a cross section of the Viet Kieu population.

Their insights allow us to look at a group of immigrants who differ in

opinions and views, but have in common an attachment to the old coun-

try and their presence in the United States.

Although some books have described the Viet Kieu as a group, none

so far has dealt with particular individuals from the time they lived in

Vietnam until they have firmly settled in the United States. No one has

2

I

NTRODUCTION

previously looked at this group of people through the various stages of

their lives from the 1950s peacetime in South Vietnam to their present

life in the United States. The Viet Kieu in America is designed to fill that

void. Who are they?

Viet Kieu is a term that began to be used by the Hanoi government

some three decades ago to label in a derisive way those who escaped

abroad. As the refugees gradually became academically and economi-

cally successful while the Hanoi government was mired in regional wars

with Cambodia and China, poverty, corruption, and isolation, percep-

tions began to change. The Viet Kieu have sent back medicine and money

(more than $3 billion in 2007) to their relatives in Vietnam and have

indirectly boosted the country’s economy. When they returned to Viet-

nam in the early 1990s, they brought with them knowledge and money.

They were envied by the local people who, in the meantime, had suf-

fered through two decades of economic crisis and political upheaval

under the communist system. From defeated people trying to get out of

the country in rickety boats, the Viet Kieu became “rich uncles, savvy

investors, entrepreneurs, or knowledgeable people.” From that time

onward, mainland Vietnamese desired to be associated with the Viet

Kieu, who became the mirror through which they saw the free world,

especially the United States.

These are the voices of some of these immigrants who within a short

period were transported from their war-torn land to peaceful countries.

Changes in their social conditions and needs during the past three decades

are also documented. If in the beginning they had to deal with the trauma

of the war and post-war years and reeducation camps, they now talk

about investment, empowerment, social issues and divorces.

After 1975, men (and some women) associated with the Saigon gov-

ernment (Republic of Vietnam) were sent to the so-called reeducation

camps. These were actually concentration camps designed to incarcer-

ate, brainwash, torture, and suppress this southern elite or ruling class

with the goal of completing on the social level the military conquest of

the rebellious South. These were communist Vietnam’s Auschwitz camps,

more than a thousand of them spread out from the South to the North.

There were more reeducation camps than schools: over 600 district reed-

ucation camps, more than 100 provincial camps and more than 20

national camps.

2

There were military and civilian camps depending on

whether they were run by the military or civilians. Military camps were

Introduction

3

especially designed for “political” inmates (army officers, soldiers, gov-

ernment officials, politicians) while the remaining people were channeled

through civilian camps.

Northern military camps were far worse than southern camps as far

as discipline or length of incarceration was concerned (“The Guava Tree,”

“A Second Chance”). Northern camp inmates were not allowed to meet

with their relatives until the third year of their incarceration. A few were

released after five years while the rest lingered in the camps from six to

25 years.

3

They included high-ranking military and civilian officials:

officers from captains or above and cabinet members, senators, politi-

cians, lawyers, and other professionals. Many inmates died in these camps

because of brutal mistreatment–torture, harsh confinement, starvation,

and lack of medical care and medicine. Southern camps were reserved

for low-level officers and soldiers who did not pose a direct threat to the

government (“The So-called Reeducation Camp,” “My Life as a Zom-

bie”). Although the exact number of inmates has yet to be released, it

ranges from a few hundred thousand to more than a million. If the major-

ity have released early on, about 343,000 people received the full harsh

concentration-type incarceration.

4

Treatment varied from camp to camp and ultimately was the deci-

sion of the camp commander or most likely the political cadre, the pow-

erful representative of the communist party. Therefore anyone caught

escaping could be shot to death in one camp but only severely punished

in another. Overall, the treatment was repressive and brutal: those who

did not comply with the rules were in a sense doomed. Their “disap-

pearance or death” for unknown reasons (“A Second Chance”) resulted

in many undocumented deaths in these camps. Their families were only

notified many years down the road or not all. This explains the thou-

sands of officers still unaccounted for on the South Vietnamese side.

Sadly, no one cared about this fact for they were on the losing side.

Besides brainwashing and brutal labor-type work, inmates were also

starved to death.

5

Their food ration consisted in general of two bowls of

rice or its equivalent a day. They supplemented their diet with whatever

they could catch or grab: tree roots, berries, snakes, insects, lizards, rats,

worms and so on. This unusual and exotic diet caused many of them to

die from poisoning or intoxication.

During the incarceration period, women struggled to keep their

families afloat and thus became the sole breadwinners. They peddled

4

I

NTRODUCTION

anything from food products to furniture, jewelry, and motorbikes in

order to survive. They tracked down their husbands, who were usually

incarcerated in remote areas, and visited with them in their jailed camps.

While many patiently waited for their return (“My Life as a Zombie,”

“The Guava Tree”), others, unable to handle the stressful situation,

moved on with their lives.

After their release, inmates were stripped of their citizenship and

watched closely by the local police to whom they had to report daily.

This was the ultimate blow to their pride for after suffering years of

incarceration and indoctrination, they felt they were discarded by the

wayside. Many developed mood changes, irritability, anger, nightmares,

and depression that follows them until this day. These were signs of Post

Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that were noted in war combatants

or inmates incarcerated in communist jails (“The Guava Tree”). Many

immediately or soon afterwards planned their escape. Staying put meant

accepting in a fatalistic way whatever the repressive communist regime

imposed on them: loss of citizenship, jobs, homes, and even expulsion

to the new economic zones (NEZ).

6

Escaping abroad became one way

to deny the communists any control over their bodies and minds, to

regain their pride and to maintain their sanity.

Escaping was, however, neither easy nor without danger. That the

former prisoners were willing to face untold dangers to escape oppres-

sion spoke volumes about their yearning for freedom. “Give me freedom

or give me death” seemed to be their motto at the time. After more or

less harrowing trips, they landed in western countries and the U.S. after

staying for various lengths of time in substandard refugee camps in

Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and other southeastern Asian countries.

7

They left behind a few monuments to commemorate landing in these

host countries as well as to honor those who had died at sea during their

escapes. In a wicked move and with the goal of erasing all traces of the

diaspora, the Hanoi government in 2005 pressured the Indonesian and

Malaysian governments to destroy the commemorative monuments on

the islands of Galang and Bidong. So far, the Galang monument has been

destroyed.

Surviving the diaspora and becoming economically independent in

western countries has been the proudest achievement of the Viet Kieu.

They have done it in less than three decades. Their successes have pos-

itively impacted American society as well as communist Vietnam. They

Introduction

5

have sent about $3 billion each year to help their relatives back home

and to invest in Vietnam. They get involved not only in commercial

ventures but also in various humanitarian projects through cultural, reli-

gious and medical organizations. In the U.S., they pride themselves on

having among their ranks a National Football League player in Dallas,

a few Rhodes Scholars in England, a NASA astronaut, a college student

who has received seven degrees at MIT in five years, a CEO of a large

electronics firm in Silicon Valley, another CEO at a Fortune 500 finan-

cial company, a New York hotel owner who gave $1 million to the 9/11

victims and so on. They are also proud of a refugee who came to the

U.S. in 1980 and began selling Vietnamese sandwiches during lunchtime

from a converted truck in California in 1981. He became so successful

that he opened a Lee Sandwiches store that blossomed into a full-fledged

company. He presently owns 25 sandwich stores and 500 sandwich

trucks in California and Arizona. He teamed up with his partner to

donate $1 million to Coastline Community College toward the goal of

building a college dedicated to teaching English and technology in West-

minster, California. And the list of achievers goes on and on. While

some are big-time achievers, others who have met with moderate suc-

cess have contributed their time, money, and effort to other Viet Kieu

less fortunate than they.

If they are successful financially, they also have their personal prob-

lems: their lives began to unravel because of social issues like love, money,

rights, and gender equality. Problems that have been left sitting on the

back burner while they struggled for financial stability re-emerge anew

and have to be dealt with. Rifts that were barely visible became huge

eyesores.

Women who have previously been homemakers tucked inside their

kitchens and told to serve their husbands and children have become wage

earners and emerge out of their houses asking for rights and gender

equality.

8

They crack open the emancipation door and run away in droves.

From taboo topics, divorces and remarriages have become mainstream

topics in the Vietnamese community abroad. Housewives who have usu-

ally been shy and reserved about sharing their private lives have become

more open and have volunteered their thoughts. Women who have never

witnessed divorces previously have gone through series of divorces and

remarriages themselves: one “Catholic” lady is presently going through

her third divorce, all of them in the U.S. Marital bonds that have been

6

I

NTRODUCTION

tight in the old country have loosened dramatically in the United States.

If in Vietnam men tend to be polygamous because of tradition, in the

U.S. women feel freer and either have boyfriends or remarry easily.

Employment outside the home has freed many of them: financially sta-

ble, they divorce their mates on the first occasion. Other problems — jobs,

money, social standings, and children — have also torn these marital

bonds apart. A woman who would never have thought about divorcing

her husband in the old country would now look down on him if he earns

less money, is less qualified, or is socially inferior to her. Having lost

their male attractiveness, husbands are easily discarded.

9

Faithfulness and

duty, which have been important virtues of women in Vietnam, have

been replaced by rights and divorce abroad.

This is not to say that virtues have been totally discarded by the

wayside. On the contrary, many spouses have remained faithful to their

mates. In this series, two women waited 12 and three years respectively

for their husbands to return from concentration camps: they continued

to live with and care for them long afterwards (“The Guava Tree,” “My

Life as a Zombie”). What needs to be stressed is that changes are under

way. The old Confucian values they have shared in the past have been

forcefully assaulted by the war, western values, greed, money, and so on.

The extent of damages caused by these forces will not be known until

the dust has finally settled. What is certain is that traditional values will

prevail to a certain degree, though to what extent is unknown at the

present time.

The social fabric of the Viet Kieu community tends to parallel the

society they live in. A recent study showed that 18 percent of U.S. men

ages 40 to 44 with less than four years of college have never been mar-

ried, up from 6 percent a quarter-century ago. This is thought to be

related to increasing female economic independence and the greater

acceptance of couples living together outside of marriage.

10

Many young

women Viet Kieu feel free to pursue their careers even after marriage

whereas they wouldn’t have three decades earlier. While Loan Chau’s

father escaped successfully from Vietnam in 1979 after spending four

years in reeducation camps, she, then six years of age, and her mother

were caught during another escape attempt. Her mother landed in jail

and she grew up in Vietnam. She moved to the U.S. in 1991, acquired a

degree in Information and Management Systems and became a singer

and entertainer. She continued her singing career after marrying a den-

Introduction

7

tist and fellow Viet Kieu.

11

Singer Tran Thu Ha, 22, born and raised in

Hanoi after the war, came to the U.S. in 2002 during an entertainment

tour, married a Viet Kieu born in the U.S. two years later and contin-

ued her singing career.

12

The end of the war was associated with a downhill slide for men

and women in South Vietnam, which basically became a large prison

camp. No country had ever enslaved its own citizens as ruthlessly and

shamelessly and on such a scale as North Vietnam did — except maybe

communist Russia, China, North Korea and Cuba. What the Viet Kieu

had endured was beyond belief: incarceration in concentration camps,

torture, starvation, forced indoctrination, strict police monitoring, loss

of citizenship and property, escape and retraining in western countries,

nightmares, stress disorders, and loss of self-esteem and self-worth for

men, and loss of material and moral support, rapes, beatings and mur-

ders by pirates, and sorrows and nightmares for women.

13

The road to freedom has been paved with torrents of tears, sea-

deep sorrows, and mountains of physical and moral hardships. The only

choice was to escape abroad in order to get away from the vindictive-

ness of the communists. Two million people fled Vietnam during the

1975–1995 diaspora and many more would have taken a similar path had

they had the financial or physical means. A joke at that time dramati-

cally described that pathologic experience: if lampposts had legs, they

too would have escaped from Ho’s paradise. It turned out to be the largest

sea diaspora ever recorded in world history.

The defeated, disillusioned and depressed Viet Kieu eventually

landed on western countries’ shores only to emerge three decades later

as a strong economic and political force that challenged the Hanoi com-

munist government. This book is about some of the people who have

survived death and despair in their country and built a new and brighter

life for themselves and their families on foreign soils. Being a Viet Kieu

is therefore synonymous to surviving the oppressive red tide regime and

to rising free, unbound, and successful like a phoenix.

Andrew Lam summarized it well when he wrote: “For though the

story of how you suffered, how you lost your home, your loved ones and

how you triumphed is not new, it must always be told.... It is the only

light we ever have against the overwhelming darkness.”

14

This collection of oral histories, although small, documents the lives

of a group of refugees from their homeland to their adoptive country.

8

I

NTRODUCTION

They have become wanderers of the world, having established them-

selves in more than 50 different countries. Were it not for the mother

tongue that remains the vital link between the Viet Kieu, they would

not have understood each other. This book also details the progressive

social changes these immigrants experienced in America. Although some

of them have shed their Confucian beliefs and embraced western ways,

others have remained fairly conservative. The fact that they have come

to the United States within a definite period of time from 1975 to 1995

makes it easy for researchers to study them as a fairly homogenous group

like no other immigrant group in the U.S. in the past.

Finally, I would like to thank all participants for sharing their per-

sonal experiences, joys, pains, failures, and successes. Their contribu-

tions to the study of the Vietnamese culture and society in general and

of the Viet Kieu in particular are invaluable.

The story “A Second Chance” has been adapted from the news of

the Voice of America.

Introduction

9

This page intentionally left blank

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

This page intentionally left blank

1

The Lotus Pond

Nghia M. Vo

E

DITOR

’

S

N

OTE

: Life in the bucolic sea resort of Vung Tau evokes the

quiet times of the early 1950s when the Catholic and French colonial

culture intersected with the local Vietnamese Buddhist culture. This

was the time of peace and prosperity before the rumbles of war.

Ba Ria, my grandparents’ hometown, was in the 1950s a small tran-

sit town no one would have ever heard of had it not been situated in a

strategic position between Saigon, the bustling capital of South Vietnam,

and the seaside resort of Vung Tau. Buses loaded with passengers and

belongings that bulged from its backside and rooftop made many daily

trips between the two cities. They stopped every ten or fifteen minutes

to pick up or drop off new passengers. Tilting heavily on one side or

another under its cumbersome load, they sputtered through the crowded

streets of downtown Ba Ria. In the process, they generated a lot of

noise — helpers yelled or banged on the bus door to signal the driver to

stop or move on — and left a trail of black diesel smoke behind them.

They frequently made a ten-minute stop at the transportation center

close to the market where they disgorged people, belongings, and at times

live poultry destined for sale at the local market.

The Vietnamese Smile

The ten-minute stop could, however, become a half-hour stop

depending upon the circumstances. In a land where rice and food had

13

always been plentiful and where peace had been present for some time,

the South Vietnamese tended to take it easy and enjoy life. They took

their time and dragged their feet because there was no pressure to com-

plete any task. Work, although necessary in life, was never intended to

be a goal in itself. Celebrations took precedent over other matters and

people competed against each other to throw parties to entertain their

guests. And there were plenty of reasons to celebrate: weddings, engage-

ments, births, deaths, promotions, and new acquisitions besides the reg-

ular holidays. Time in this environment became “elastic” and punctuality

is not a recognized Vietnamese virtue.

Passengers who were left sitting on the parked buses in one hundred-

degree heat without air conditioning might get angry and demand an

explanation. The driver’s assistant, while apologizing for the delay, would

state he was waiting for a few passengers or a shipment that had not yet

arrived. He would promise the bus would leave “soon.” That remark was

punctuated by either a big smile or a smirk. The Vietnamese smiled fre-

quently.

1

The smile, however, does not have any sarcastic meaning as else-

where in the world. Intended to deflect the attention away from any

embarrassing situation, it often inflamed the anger and irritation of west-

erners who perceived the inappropriate behavior as an insult. The Viet-

namese smiled not only when they were happy, but also when they were

sad or ambivalent about something. They smiled because as straightfor-

ward people they could not fib very well and were often at a loss for words

to explain their complex feelings. They also smiled when they were caught

in an embarrassing situation. Unable to produce an adequate explana-

tion for what they had done right or wrong or to express the deep regret

they felt, they just awkwardly smiled. This is known as a “sorry-smile,”

a unique Vietnamese trait that has been misunderstood by westerners

and Vietnamese alike. On the other hand, if they did not smile, they

could become angry or answer in a blunt manner in order to protect the

deep emotions they experienced. For beneath this smile or bluntness ran

a wealth of often complex if not contradictory feelings or emotions.

My Grandparents’ Home

My grandparents, who moved to Vung Tau in the early 1940s,

bought a two-acre orchard planted with longan trees — Vung Tau’s lon-

14

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

gans are known in the country for their sweetness and texture. My grand-

father, however, passed away shortly after the purchase. The orchard

turned out to be a good investment for the future and stability of the

family, since my grandmother, a housewife with at most an elementary

education, did not work. Women were not allowed to go to school in

the 1920s and 1930s and without education, they could not get a decent

job. The orchard therefore provided the family with a steady source of

income, though it was not big enough to feed a large family year round.

They also bought a townhouse — a colonial import — with running

water and electricity, which was rather uncommon in the countryside at

the time. I still remember that house, which was located about a mile

away from the orchard. It was the first of a row of seven one-story brick

houses. It was divided into three almost equal sections: a family room,

a bedroom, and a kitchen area with a bathroom. The front door opened

directly into the family room that contained a hutch and a dining table

as well as a five-foot tall altar made of fine black wood and encrusted

with lacquered designs.

On top of the altar was the picture of a handsome man I wished I

knew: my grandfather. He passed away before I had the chance to meet

him. On the side of the picture were two brass candleholders, an incense

holder, a gong, and a brass plate with fruit offerings. Once a week my

grandmother brought bananas, mangoes, or other fruit depending on the

season, lit up a few incenses, beat the gong a few times, and mumbled

prayers after bowing many times in front of the picture. I understood

that this was “ancestor worship”

2

through which the living conveyed

their respects and debt to the deceased and kept the relatives’ soul happy

in the other world (ben kia the gioi). In return, the appeased soul would

protect the family from disaster or unhappy circumstances. It has been

said that if a soul was not cared for properly through that worship, it

could become an angry ghost and hurt the family.

The whole family slept in the middle room on three seven-by-

five-feet dark-brown, wooden divans. Instead of a mattress, a straw mat

was spread over the hard wooden surface that remained cool and was

therefore very inviting in the hot summer weather, but was definitely

cold and unfriendly during winter. At night each person was required

to hang up his or her own mosquito net, which would have to be folded

back and taken down each morning. Without exception, everyone went

through the same routine every day. Life thus became a monotonous

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

15

routine that was necessary in order to fight against the buzzing and blood-

thirsty mosquitoes. They were so hungry that they would dart to any

unprotected skin and caused sharp and painful bites that swelled into

red raised lesions or could lead to severe chronic malaria or Dengue

fever.

3

The back room of the townhouse consisted of a bathroom, kitchen

and dining room and led to a small enclosed courtyard. Cooking was

done with charcoal or wood. Smoke would fill up the kitchen area and

darken its walls. Since refrigeration was not frequently used at the time,

my grandmother, like other housewives, would go to the market every

day to get fresh food, meat and vegetables with cooking done daily.

The Confucian Family

According to Confucian rules

4

that were ingrained in the psyche of

the Vietnamese and were a relic of past Chinese influence (111

B

.

C

.–939

A

.

D

.), the society is patriarchal in nature. The wife should be obedient

to her husband. He provides for her needs and she faithfully serves him.

Should the husband die, his wife would faithfully raise the children,

especially her eldest son who in the absence or death of the father rep-

resented the authority in the family.

5

Family ties in a Confucian world

were vital to the stability of the society; back then, no one dared to chal-

lenge these two-millennia old rules unless he was willing to be ostra-

cized.

The family was a miniature society with its often unwritten rules,

regulations, and etiquettes. It is structured on many generations. As long

as they were alive, grandparents, parents, children, uncles, aunts, and

cousins were all part of the family. Everyone knew his or her own place

in this “extended family,” for respect for the elders was de rigueur in this

hierarchical society. They occupied the best place at the table and were

cared for until their death. They were often served first and given the

best portions of the meals. The family concept took precedent over the

individual, as evidenced by the fact that the Vietnamese and Chinese

family names (contrary to western rules) came first followed by the mid-

dle then the first names. People therefore addressed themselves by their

titles and first names, like Mr. Paul, Ms. Mary, or Dr. Bill rather than

by their last names.

16

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

Life at the Farm

I spent a couple of years with my grandmother in the simple coun-

tryside and quiet atmosphere of Vung Tau. She first lived at the town-

house but later moved to the house at the orchard and rented out the

townhouse to weekenders. The stay at the farm gave me a unique expe-

rience without which I would never have known what country life was

like. Since there was no running water at the farm, rainwater was col-

lected during the rainy season and stored in huge earthen jars that sat

on the side of the house. During the dry season, workers were hired to

carry water from the nearby well to fill up the jars. Because the water sat

idle for a long time, it served as an ideal breeding ground for a swarm

of mosquitoes. Geckos — up to six or seven-inches long — used to crawl

on the walls and made their presence felt by making their characteristic

noises: Cac Ke ... Cac Ke ... Cac Ke.... Outside, hens warned us in the

morning they had laid their eggs with their Cu Tac ... Ca Tac ... Cu Tac

... calls. I knew it was time to run out and collect them.

The orchard had about 40 to 50 longan trees as well as a few papaya

and guava trees. The 20-to-30-foot-high trees produced flowers in spring

then small longans that had to be covered until maturity. Ladders were

used to reach the outermost branches where the clusters were the most

difficult to cover. Workers peeled back the proximal leaves and carefully

shoved the clusters of longans into straw bags. They then tied the neck

of the bags to prevent bats from coming in contact with the fruits. Bats

came out at dusk, made rapid circles above the trees, then dropped on

their targets. They loved the juicy longans and could wipe out a whole

tree in a couple of nights thereby greatly diminishing the harvest. Work-

ers had to work fast for two to three weeks to prevent the destructive

behavior of the hungry bats. Everyone would rest for the next two to

three months during which the fruits matured.

At the end of the summer, the air was filled with the fruity aroma

of ripe longans. Grandmother would check whether they were ready for

harvest. She would undo the straw tie and widen the neck of the bag

before carefully pulling it back, making sure not to pull on the fruits

themselves. At harvest time, workers broke the branches holding the

bags and carefully passed them down to grandma. She opened the heav-

ily loaded bags, pulled out the ripe longans and with great care set them

aside. I remember the excitement in her voice, the sound of “uh ... ah”

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

17

escaping from her lips as an expression of pleasure at the sight of the

golden and ripe longans. She handled them with extreme gentleness as

longans attached to their stalks were more valuable than loose ones. Ripe

fruits were covered with a thin yellow-pinkish skin, which once peeled,

let a sweet juicy liquid flow out. The trick was to catch the juice before

it spilled all over one’s shirt. The fruit was then dropped into one’s mouth

while the tongue was used to separate the soft velvety meat from its

brown seed. It was time to spit out the seed and to enjoy the succulent

meat. I loved longans’ sweet and juicy taste and could never resist the

temptation to sample them, although over-sampling did result in indi-

gestion or stomach cramps.

Wholesale buyers came to the orchard to bargain. They bought

large quantities of fruits and took them to the market for resale. Within

two to three weeks, the harvest was completed and it was time for the

clean up. The straw bags were left to dry in the sun then stored away so

they could be reused next season.

Weekends at the Beach

Vung Tau exhibited the simple and quiet atmosphere and the charm

of a small town. It has two beaches: bai truoc (front) and bai sau (back).

The two-mile long bai truoc was bordered by row after row of hundred-

year-old palm and pine trees that gave it shade and protection from the

hot tropical sun and an atmosphere of year-round greenery. It was bor-

dered by a large mountain on the right side and a smaller one on the

left. It was always crowded, especially on weekends because it was part

of the town itself. The bai sau was remotely situated on the other side

of the smaller mountain. It was less crowded and cleaner than the bai

truoc. Without foliage, it did not provide any protection from the sun.

The countryside peacefulness was shattered every weekend by the

influx of thousands of Saigonese who suddenly doubled or tripled the

town’s population. Demands for room, food, and entertainment sky-

rocketed and usually exceeded local capacity. Housewives — my grand-

mother included — put their houses up for rent. They went to the beach

every Friday afternoon to look for their own customers.

Visitors paraded their cars around town and drove aimlessly along

the usually deserted roads. Cars and motorcycles that were rarely seen

18

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

during weekdays appeared out of nowhere. Bumper to bumper traffic

was common especially on beach roads. Vroom... Vroom.... Drivers fought

for the right of way as they negotiated the narrow streets amidst heavy

traffic. Yells, screams, laughs were heard everywhere. The beach sud-

denly became crowded, noisy, and bright with lights and sounds. Street

vendors descended in swarms on the beach peddling all kinds of food.

Spicy braised shrimp, boiled clams, and especially salty roasted crabs

were offered along with the ubiquitous roasted dried squids that were

consumed with hot hoisin sauce. Loud music could be heard hundreds

of yards away. After the lively Friday and Saturday nights, Sunday morn-

ing peace descended on the town as one by one the “strangers” packed

up and departed, leaving behind tons of garbage. It was time for grand-

mother to clean up the house, put everything back in order, and get ready

for next week’s guests.

My memories of my grandmother are still very strong. Like other

Vietnamese women, she enjoyed chewing betel leaves and areca nut

mixed with a little tobacco. During social gatherings, as guests chatted

about their families and businesses, she would offer them betel leaves and

areca nuts. The mixture was supposed to give them an “aphrodisiac”

feeling. They then spat the red liquid into a jar or sometimes onto the

ground, which when stepped on would stick to the soles of shoes like

gel.

The Shrine of the Whale

I also remember the time I went to the dinh, a large community

hall about two-and-a-half miles from the orchard. Four gilded dragons,

one in each corner, decorated the curved roofs of the dinh where all the

county’s activities took place. A whale that had beached and died the

night before gave the villagers an occasion to celebrate since it is unusu-

ally rare for a whale to beach close to the village. According to traditions

borrowed from the Chams centuries ago, villagers would pay their last

respects to the Ca Ong (King of the Fish) so that the spirits inhabiting

the fish would help fishermen in their business. The Chams

6

were a Hin-

duized civilization that flourished in present-day central Vietnam

between the 7th and 15th centuries

A

.

D

. The Vietnamese, being selec-

tive, had adapted this foreign tradition and made it their own. Not as

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

19

adept in seafaring as the Chams, they kept this tradition hoping whales

would protect their fishermen from the perils of the sea.

Monks dressed in saffron robes presided over the unprecedented

ceremony. There were the usual offerings of fruits, flowers, and food that

seemed to be more abundant than usual. I stood there in awe looking at

the large plates of plump grapefruits, tropical green oranges, juicy lon-

gans, purple mangosteens, and spiny and suspiciously smelly durians.

My eyes opened wide at the view of the graceful pink and white lotuses,

yellow-gold chrysanthemums, and deep-red gladioli that were carefully

arranged in gigantic earthen vases. A haze of lingering smoke emanated

from the hundreds of lit incense sticks and candles. The villagers had

brought home-made sticky rice cakes along with a variety of vegetarian

dishes as offerings to Buddha and the spirit of the Ca Ong. The food was

later served along with drinks to all the guests.

The whale looked so huge that I was afraid of getting close to it.

Although it was dead, it still looked frightening with its large, hazy eyes

and its massive weight resting on a row of tables set up in the middle of

the dinh. Never before had I seen such a large fish. I remember wonder-

ing how the villagers could have transported such a huge mammal from

the beach to this place, especially through narrow, winding countryside

roads. Nor did I know how they would dispose of it. The town must

have mobilized all the villagers just to lift the whale off the beach. I only

found out years later that they had disposed of the flesh but kept its

skeleton stored in huge glass cases in the Lang Ca Ong (Shrine of the

Whale). Vung Tau could then boast of having one of the few shrines in

South Vietnam dedicated to the “cult of the whale” where visitors could

come and revere this fishermen’s savior.

On another occasion, Hat Boi was also performed at the dinh. These

were traditional Vietnamese musical plays during which classic themes

were rehashed: good versus evil, sages versus demons. Characters with

given superhuman features engaged in fantastic adventures during which

they tried to prove their moral greatness against evil creatures or devi-

ous people. The actors and actresses dressed in traditional multicolored

costumes carried swords and spears with flags sticking out of pockets sewn

to their backs. The heavy make-up they wore not only gave away the

role they played but also conveyed their own emotions. For example, a

strong and valiant prince always had his face painted in red with dark

black eyelashes and a long silky beard. To the rhythm of traditional musi-

20

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

cal instruments such as cymbals, gongs, tambourines, and flutes, the

actors would retell familiar stories while gesticulating and moving

around. Each gesture or facial expression was symbolic and full of his-

torical meaning. These musical plays were magical and grandiose and

drew audiences from near and far. I remember how fascinated I was by

the display of colorful costumes, the facial expressions, armaments, and

movements of actors and actresses. I especially loved the plays in which

the good characters always won over the evil ones and I would ask my

grandmother to take me to see the next play.

Colonial Education

I lived in two worlds: one of Vietnamese tradition and the other

made from remnants of French colonialism, which in the late 1950s coex-

isted uneasily before finally giving way to a predominant Vietnamese

society. The Europeans came to Southeast Asia looking for spices and

trade and for an access route to China as early as the 16th century. Oth-

ers used the occasion to proselyte and teach Catholicism. At first, the

Vietnamese kings and emperors looked away and tolerated them with

some uneasiness. Believing they were sons of Heaven and in their man-

date as emperors, they did not feel threatened by the infidels. However,

as the influence of the priests grew, uneasiness turned into suspicion, then

fear; at the urging of the mandarins (high court officials), the kings shut

down all doors and contacts, trying to keep foreign influence at bay. The

self-imposed isolation kept them in their backwardness and away from

modern technological advances that could help improve the welfare of

the people. Economic and cultural stagnation soon led to the downfall

of the feudal monarchy in the face of foreign invasion.

While living in Vung Tau, I first attended a grammar school man-

aged by a French schoolmistress — a relic of French colonization. Look-

ing back, I remember a rainy day in October when my grandmother

unexpectedly showed up at the school with a raincoat for me. The teacher

called me over to pick it up. Although thankful for her gesture, I was

embarrassed because of all the parents it had to be MY own grandmother

who showed up with a raincoat. I did not know how to deal with the

situation and mumbled something the teacher could not understand. A

big and loud “Thank you, Grandma” might have helped. The shy, soft,

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

21

and lacking-warmth words I uttered did not, however, satisfy the teacher

who sent me to the back room to sit in for the rest of the day. As I was

not very adventurous, I had not explored the back of the building. I

knew vaguely that there was a storage area but did not realize its real use.

There, to my big surprise, I found many other students who were also

“serving time” for various reasons. Amazingly, I wound up spending an

interesting day in the back room and never enjoyed school that much.

We made airplanes out of paper and threw them into the air. We were

free to do anything we wished except make noise. The teacher, who was

always in the front room busy taking care of the “good” students, rarely

set foot in the back room.

As I came home from school one day, I noticed a beautiful young

lady sitting in the living room of our townhouse polishing her nails.

Since I did not know what this stranger was doing in our house, I went

to the back and asked my grandmother. She told me the lady was vaca-

tioning while waiting for her husband to pick her up. For a few days, I

had a wonderful time with her. The lady, despite not being my mother,

took me to the market and bought me toys, the delight of any child.

There was nothing fancy, although I appreciated her care and warmth.

She took me to the beach and let me swim in its warm waters while she

read magazines. There was no question I missed her a lot when she left.

It was only later that I thought what I missed was a real mother like her.

I did not realize until years later that I was involved in a swap. My

uncle and one aunt went to live with my mother in Saigon to further

their schooling (there were no French high schools in Vung Tau), and

in order to cut down on her workload — she had five children — she sent

me to Vung Tau to stay with my grandmother. So for two school years,

I lived apart from my parents and siblings. It never came to my mind to

ask my mother why she singled me out for the swap because I knew she

did the right thing and I really enjoyed living in the countryside during

all this time. This period actually gave me another insight as to what life

was all about.

The following year, I went to study with the sisters at the St.

Bethany convent. As in any Catholic institution, the beginning and the

end of the day were devoted to prayers. Overall, the sisters were good

teachers and I enjoyed studying with them. But I always thought they

were best at making money. Since they knew very well that students

could not resist sweet temptations, they brought out all kinds of candies

22

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

and cookies to sell to the students during recess times. We all rushed out

of classes to buy these candies and gorge ourselves. The sisters also sold

books, pencils, papers, and other school supplies. From my youthful

perspective, it looked as if the sisters were making a lot of money from

us.

The sisters were also great motivators. During the fall season

(although Vietnam actually has but two seasons — rainy and dry), leaves

would fall and cover the whole school ground. I did not know why they

did not hire workers to rake the leaves. Perhaps they could not afford it

or maybe they just did not want to. Whatever the case, the students were

asked to do the job and therefore had to show up earlier than usual for

that purpose. Later, we would be rewarded for our good deeds. After

class began, we would line up in front of the sister and in turn would

name our own prize: forty points for my friend Tam. And the sister duti-

fully would mark down the number in a big black register book — impres-

sive in its size. I thought I would deserve a higher mark since I did more

work than Tam. I settled for 80 points. And the sister dutifully wrote

down the number. We then returned to our seats happy about having

done a good deed while at the same time earning some extra points that

would be added to our marks and could raise our overall standing in the

class. And so every morning, we would come back and volunteer to work.

This may explain why the sisters’ schoolyard was always the cleanest in

the neighborhood.

During the lunch recess that took place between 12 noon and 2

P

.

M

., we walked home to take our lunch and to nap. Someone would

beat a gong around 2

P

.

M

. to advise children and employees to either

return to school or to their offices. The tropical weather was so hot in

Vietnam (air conditioning was not available at the time), that a long

siesta during which schools and offices were closed was necessary. I later

noticed that other countries like Mexico and Italy enjoy similar lunch

breaks. During these recesses, I sometimes stayed back, waded in a small

puddle of water in the back of the school or looked for crickets in the

bushes. There was nothing like the freedom to roam around and search

for the unknown. When I arrived home late for lunch, I would sustain

a barrage of questions from my grandmother with occasional spanks on

the butt if I did not give her the right answer.

At the end of the school year, each family had to contribute to the

commencement in order for us to obtain our reward. This came in the

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

23

forms of books, crayons, pens, and so on, which were presented at a spe-

cial ceremony. Students accompanied by their parents and relatives

crowded a gathering hall. Following the usual speeches, students whose

names were called came to the podium to receive their reward.

Buddhist Influence

In that provincial atmosphere, besides countryside life and French

education, I was also exposed to two major religions: Buddhism and

Catholicism. Had I been brought up in busy Saigon like my brothers,

that influence would not have been significant. The simple and relaxed

life in Vung Tau brought people closer to religions. While Catholicism

was brought into Vietnam by the French fairly recently, Buddhism has

been present since the second century

A

.

D

. Buddhism permeated Asian

society the same way that Christianity was the main religion in Europe

and America. Coming from India and China, it spread into Vietnam

from the second to the sixth centuries and reached the height of its glory

between the seventh to fourteenth centuries

A

.

D

. Although not all Viet-

namese actually practiced strict Buddhism, they followed a Buddhist

code of living that explained why the South Vietnamese are benevolent,

compassionate, and pacific. Contrary to their northern counterparts,

they did not like to engage in war or killing, except under extenuating

circumstances.

7

On one occasion, I went with grandmother to her hometown, Ba

Ria, to see her adviser, a hermit monk who lived on top of the Ba Ria

mountain. Since there was no asphalt road to the top, we had to climb

steep slopes through narrow mountain trails that accommodated only one

person at a time. These trails that were not designed for visitors, but only

for monks wanting to live in seclusion, were rugged and barely passable.

Some steps were as short as a child’s foot or as high as a foot and a half.

Others were missing or even non-existent. Time and traffic had taken

its toll on these steps. By the time we reached the summit, I was so

exhausted that all I wanted to do was to sit down on the porch to rest

my cramped legs. I looked at the rugged but peaceful hills that spread

all the way to the horizon while grandmother talked to the monk. I was

impressed by the ascetic and simple life these monks led, far away from

the corrupting ways of modern society. Visitors came to ask monks’

24

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

advice on all subjects including affairs of the heart and family problems,

as well as questions about religion and afterlife. In return, they offered

the monks either goods, fruits, or money. The monks functioned as spir-

itual guides, advisers, and occasionally fortunetellers. They were the

“learned” men who spent all their time studying, thinking, praying and

dispensing their wisdom to lay people.

Grandmother had a large prayer room at her orchard house with a

three-foot tall bronze Buddha sitting atop the altar. This was her “sacred”

area, and I used to walk into this place with awe, apprehension, and

respect. The bronze statue inspired not only peace with its eternal and

enigmatic smile, but also, for a youngster like me, a sense of power, mys-

tery, and force. One could feel that there was something more in the air

than just a simple statue. Grandmother insisted that everyone (usually

my two aunts and I) be present at the hour-long nightly prayer session.

It could take up to two hours, especially during certain Buddhist

occasions. No exceptions were allowed as Saturday and Sunday were

also prayer days. I used to dread these long prayer sessions. Worship-

pers donned brown gowns while saffron robes were reserved for monks.

The worst thing I remember about these nightly sessions was the need

to wear one of these brown robes. They were infrequently washed, and

the pungent acid odor of the sweat from all worshippers who had worn

them before clung to them. Only swarms of buzzing mosquitoes

were attracted to this odor. I almost became sick every time I had a robe

on.

Grandmother began her nightly session by lighting up candles and

incenses; slowly, in a very religious manner, she began reciting Nam Mo

A Di Da Phat ... Nam Mo A Di Da Phat ... while beating on the gong.

The rhythmic pounding of the wooden stick on the gong induced rapid

relaxation and peace in the quiet evening. Once in a while, she hit a

bronze bell that tolled a clear, sharp, and metallic sound: bong ... bong....

The sound disrupted the peacefulness of the night and marked the sig-

nal for everyone to bow down. Recitations would go on and on and were

interrupted only by another bell sound. Soothed by the monotonous

incantations, I fell asleep in the middle of the long and “challenging”

prayer sessions. Neither the incantations nor the bell sounds could dis-

turb my nap. My aunt would wake me up, but soon I fell asleep again

and had to be brought to bed.

While living in Vung Tau, during daytime, I had to say prayers to

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

25

Jesus and the Virgin Mary at the sisters’ school, but at night, I had to

don a brown robe to say prayers to Buddha. I keenly remember the rou-

tine: Praise the Lord or Ave Maria songs in the morning then Nam Mo

A Di Da Phat incantations at night. Melodious songs and hymns in the

morning were followed by the monotonous recitations of Buddhist texts

in the evenings. That was enough to give any youngster a split person-

ality, although I moved from one religion to another without difficulty.

I had no problem talking to a Buddhist nun one minute or to a Catholic

sister the next one: for me they were both good people. I was reciting

the verses like a bird because I really did not understand the meaning of

the Buddhist and Catholic texts at that time. I was therefore repulsed

by their stiffness and routine. I only realized years later that they were

the foundations of my upbringing and would help me in my search for

peace of mind and meaning of life. More than the reciting of incompre-

hensible texts and monotonous incantations, these hours of prayers forced

me to turn inward and look at another dimension of life. This was my

introduction to spirituality without which life could not reach its full

potential and meaning.

The local pagoda in Vung Tau housed many Buddhist monks,

apprentices, and nuns. It was a huge one-story spread-out complex with

lodgings, kitchens, working areas, and a large gathering hall located at

one end of a large lotus pond. The main hall was presided over by a 15-

foot-tall bronze Buddha statue along with numerous smaller statues of

all sizes from different countries. There were even a few Indian Buddha

statues with twelve arms, six on each side. Each Buddha had its own and

particular gaze: peaceful for some and stern for others. A soft and per-

manent smile graced the face of some statues while others remained

stone-faced and tight-lipped. An overall air of mystery, majesty and

power permeated the praying area and caused guests to enter the hall

with awe and respect. The poorly lit hall (due in part to the absence of

windows) increased the mystery of the environment. Hundred of incenses

and candles were lit during main celebrations. Swirls of dense incense

smoke gracefully floated around the statues suspended in limbo in mid-

air while emanating celestial aromas all over the area. Offerings of

bananas, oranges, pineapples, and durians were prominently displayed

on the altar along with a multitude of flowers. Monks sang prayers while

hitting gongs and bells intermittently during these celebrations that could

last a long time.

26

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

The Lotus Pond

I was too young, bored, and uninterested to participate in these

major celebrations. I therefore joined the young apprentice monks behind

the pagoda close to the lotus pond. We jumped into one of the canoes

anchored on the shoreline and paddled around the pond, admiring the

thousands of green lotus leaves that seemed to float on the surface of the

water among beautiful pink lotus flowers, some in full bloom. Nothing

instilled an image of peacefulness and permanency more than these green

lotus leaves sitting still, impervious and unsinkable on the surface of the

water. It was no wonder that people had always painted Buddha sitting

and meditating on a lotus leaf. The apprentice told me about how they

used lotus flowers to decorate the altars, stems of the flowers to cook side

dishes, and lotus seeds to eat. The lotus flower thus had multiple uses

besides symbolizing the purity and freshness of the soul that even mud

could not stain. Then one of the apprentices would recite the famous

folk song:

Nothing is more beautiful than the lotus in the pond,

Green leaves, white flowers, amidst yellow stamens,

Yellow stamens, white flowers, green leaves,

Close to mud, yet does not smell muddy at all.

We paddled slowly, savoring every minute of freedom and peace-

fulness looking at the fish swimming just below the surface of the limpid

water while butterflies and dragonflies swirled around us in complete

silence. The barking of a dog in the distance or the chirping of the birds

occasionally interrupted this quietness. There was nothing more peace-

ful than taking a ride around this isolated lotus pond: no wind, no rip-

ples, and no noises. The overall atmosphere conveyed an image of serene

peacefulness that symbolized Vietnam just emerging from colonialism.

It also allowed me to let my thoughts wander in the quiet and deserted

countryside among the beautiful lotus flowers, a time for recollection and

healing. That was the reason I always came back to take more rides

around this pond.

The full circle around the pond took us some time to cover. When

it was time to turn around, I would beg for another trip around the pond

to no avail. As the canoe reached the shore, I jumped into the water try-

ing to get to the ground first. Once though, the bottom of the pond

1. The Lotus Pond (Vo)

27

turned out to be deeper than expected and I got all wet. I remember

how the apprentices started laughing, then brought me inside, took off

my clothes to dry, and gave me a snack while I was waiting for my clothes.

On another occasion as I was sitting in front of the boat, I leaned

forward and saw minnows swimming right under the still surface of the

water. I dropped the iron chain to see whether it would scare the fish.

When I turned around, to my surprise I found a minnow swimming in

a small puddle at the bottom of the boat. I tried to do it again, but this

time no new fish got trapped into the boat. I never found out whether

it was just a coincidence or whether the chain had forced the fish to get

in through a small hole at the bottom of the boat.

This was life in Vung Tau and South Vietnam in general as I knew

it in the early and mid–1950s. Life was bucolic, tranquil and simple, and

the people were happy and benevolent. Life unwound itself before us,

lovely and peaceful like the stillness of the pond with its lotus flowers,

its minnows and its absence of ripples. There was no rumor about war

or killing. My countrymen and I were lulled by this peacefulness that in

retrospect left us unprepared for the fact that this idyllic life would not

last long and that worse things were about to fall on all of us.

28

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

2

Remembering Saigon

Nghia M. Vo

E

DITOR

’

S

N

OTE

: In “Remembering Saigon” a Viet Kieu remembers

the old Saigon with its flower market, soccer games, autumn festival,

and lengthy preparations for the Tet festival. The Cho Cu market

where food was served outdoors, the French architecture, the influence

of the Americans and the languorous times spent at the Saigon pier

are recounted. It was a city with diverse backgrounds and strong Chi-

nese, French, American and Vietnamese influences. The women in

their tightly fit ao dai with their free ends floating in the wind evoked

an image of yin in a yang environment. Saigon was and remains an

entrepreneurial, rebellious, and non-conformist city that personifies the

South Vietnamese spirit.

The largest city in the country was a bustling commercial city. It

was a sleepy Cambodian (Khmer) fishing settlement known as Prey

Nokor when the Vietnamese settled around it in 1624 and began to con-

trol it in 1698.

1

In the early 1970s at the height of the American inter-

vention, it boasted almost two million people, although that number

could be two to three times higher due to the large influx of refugees

coming from the countryside. It was the economic center of South Viet-

nam, the eye, ear, and heart of the country. Rice harvested from the lush

paddy fields of the Mekong Delta, fish and shrimp farm-raised along the

banks of the river, rubber from the surrounding plantations, and tea and

coffee from the central highlands were all shipped to Saigon for trade.

Imported goods arrived at the port of Saigon. This was where commerce

began and ended in Vietnam.

29

Downtown Saigon

Remnants of French architecture were apparent in many sections

of the city, among them the Opera House (former Congressional Build-

ing), the City Hall, the Main Post Office, and Notre Dame Cathedral.

Majestic boulevards lined with hundred-year-old trees and dotted with

high-rise buildings and chic villas coexisted with small winding alleys

lined with corrugated-steel covered shacks and crumbling houses. Saigon

was crowded, dirty, and disorganized in some areas, while it was serene,

upscale, and almost deserted in others. Beautiful women were seen wear-

ing exotic ao dai —Vietnamese tunics slit on both sides from the waist

down — or tailored European outfits, and mixed with poorly-dressed

people in multicolored shirts with black pants. Saigon was a city of wide

contrasts, a city for rich and poor that served at one time as a French

provincial city: It was once dubbed as the “Pearl of southeast Asia.”

Giant tamarind trees grew on both sides of certain streets. They

became so huge and had such dense foliage that they provided a perfect

shade from the sizzling summer sun. I once felt like I was biking under

a canopy of jungle trees each September when I returned to school.

Nowadays, the sight of a tamarind immediately brings back to me the

memories of these school years where I got my first taste of freedom, met

my first school friends, and played and competed against them in many

curricular and extra-curricular activities.

Close by stood the Gia Long School, where beautiful, shy and gig-

gling girls wearing their white ao dai could be encountered. I remember

fondly watching them walking on the sidewalks with one hand clutch-

ing their books and the other holding onto their non la (conical hat) as

the wind frequently displaced the hat off their heads. The free ends of

their ao dai undulated in the breeze and their thick, black, and silky hairs

fell like a nape all the way down their waists. The ao dai molded tightly

against the curvatures of their bodies exposing their beauty. It has been

said that they hid everything but also exposed everything. The girls wore

wooden guoc (clogs) that beat the pavement with rhythmic noises Coc

... coc ... coc. I used to marvel at how they could move with such ease

and precision in their slippery guoc while holding onto their non la, hair,

and ao dai that floated in the wind. The grace and gentleness with which

they moved, still strikes me to this day. They conveyed an image of the

frailty of the Vietnamese in the middle of political storms and war

30

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

tragedies. This was the picture of yin in the middle of a yang environ-

ment.

I often biked down Cong Ly Avenue and the Presidential Palace

would appear on my right. If I turned left in front of the Palace, I ended

up on Thong Nhat Avenue. There stood the magnificent Notre Dame

Cathedral, the main Post Office, the American Embassy and at the end

of the avenue the Saigon Zoo and National Museum. Cong Ly Avenue

led me straight to the Intercontinental and Majestic hotels. During the

height of the war, these places became favorite gathering areas for Amer-

ican GIs, foreign journalists, and businessmen who exchanged tips or

traded news about the war and Saigon politics.

Further down the road flowed the Saigon River, which brought an

array of foreign ships and with them merchandise, tales, and news from

abroad in exchange for rice, seafood, rubber, and the local charm of the

jewel of Southeast Asia. My parents used to take us to the Bach Dang

pier to watch the huge foreign ships load and unload their merchandise

and to look at sampans and rowboats gliding quietly on the dark waters

of the river. This was another image of yin (sampans) and yang (ships)

at work and Saigon was full of these contrasting images. The river, which

must have been clear at its source, had collected all the garbage humans

dumped into it throughout its journey to the sea. When the river waters

finally arrived in Saigon, they had acquired a dark and sad color that was

beyond recognition. They nonetheless made their way into the ocean

where they would dump their load and regain their fresh color by mix-

ing with ocean water. Once in a while, the noise of a motorized engine

ripped the air and disturbed the quiet peace. A few ducks waddled in

the cold waters and quacked relentlessly. We sat on the pier under a large

umbrella sipping cold drinks and savoring the light breeze that swept

the area while dreaming about a boat trip to a faraway island. Close by

was the My Canh floating restaurant where people could dine while

watching river activities. The exotic location attracted many customers —

mostly foreigners. The Viet Cong used the occasion to terrorize the pop-

ulation: They blew it up in June, 1965, killing 124 people including 28

Americans.

We were brought back to reality when sunset rays signaled the time

to go home. We then went to the Cho Cu (Old Market) to have dinner

together. There were many indoor restaurants along with excellent out-

door dining areas that served dishes from noodles with Peking duck to

2. Remembering Saigon (Vo)

31

pho.

2

Meals were washed down with delicious desserts of lychee drinks

and xam bo luong, Chinese fruity drinks that were claimed to be energy

boosters. As in many Asian cities, outdoor dining provided some of the

best food in the city in a casual and relaxed atmosphere.

On weekends, while ladies enjoyed shopping, their husbands went

to the stadium to enjoy soccer matches between Saigonese and foreign

teams. Soccer was the main sporting attraction in the country with the

two best teams being “Army” and “Customs.” I remember these times

when my father took us to the large Cong Hoa stadium in Cho Lon to

watch these games. A smaller downtown stadium had been torn down

because of its inability to accommodate large crowds. We had to arrive

early to the stadium otherwise there would be no good places left. We

pushed and shoved trying to squeeze through the small gates and sat

through rain and heat to watch our team play and cheer it up. We either

came home jubilant or depressed depending on whether our team won

or lost, although the experience was always entertaining.

Flower Market

Saigon would not be Saigon without its flower market that gath-

ered a few weeks before the Tet festival. Tet fell between January 19 and

February 26, and marked the Oriental New Year as well as everyone’s

birthday. According to oriental customs, everyone was considered one

year older on Tet day no matter which month he was born in. This

explains why Tet was such a big holiday in Vietnam. Most people cele-

brated it for three days, while those who could afford it took the whole

month off.

Preparations began as early as two to three months prior to the date.

My parents would have new outfits custom-made. We went shopping

for new shoes. This was the busiest time of the year for the tailors who

worked overtime to complete their customers’ orders. Each customer

would have two to three new outfits made and brought in an array of

fabrics in all colors, in silk, brocade, or just plain but expensive fabric.

Houses were brushed up and sometimes repainted, broken doors and

windows were repaired, new curtains made, and chandeliers and silver-

ware polished. This was the time to settle all the debts, as they could

bring bad luck for the incoming year.

32

I. P

EACE AND

W

AR

There was fervor in the air. People were on the move. They bought

everything and merchants had their best time ever. Candles, incenses,

and firecrackers were sold along with grapefruits, watermelons, persim-

mons, oranges and so on. There were rice cakes filled with pork meat

called banh chung and banh tet as well as candies, cakes, sweet dried fruit,

soft drinks, and beer.

The flower market took place on Nguyen Hue Avenue in down-

town Saigon. Ablaze with colors and filled with sweet fragrance, it

remained open daily until midnight and closed on lunar New Year’s Eve.

The spectacle was even more spectacular at night. A rich variety of flowers

were found: dahlias, yellow chrysanthemums, red cockscombs, red and

white poinsettias, yellow “mai” (Prunus mume tree), orchids and kum-

quat trees. We went from one vendor to another to try to get the best

deal possible. Vendors, on the other hand, hawked their products extol-

ling the beauty and freshness of their flowers and competed for cus-

tomers’ attention. My parents chose a mai, the flower of Tet, and hoped

it would bloom during the length of the Tet festival: This would be a

sign of good luck for the incoming year. Vietnamese people lived more

with their feelings, predictions, and hopes than on actively seeking or

fighting for something concrete. They spent a lot of money on for-

tunetellers trying to foresee the future — especially during the Tet period.