CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

497

© 2001 Psychology Press Ltd

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WORK AND ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY, 2001, 10 (4), 497–522

Conflict escalation and coping

with workplace bullying:

A replication and extension

Dieter Zapf and Claudia Gross

Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt, Germany

Bullying or mobbing is used for systematically harassing a person for a long time.

In the context of stress theory, bullying is a severe form of social stressors at work,

whereas in terms of conflict theory, bullying signifies an unsolved social conflict

having reached a high level of escalation and an increased imbalance of power.

Based on a qualitative study with 20 semi-structured interviews with victims of

bullying and a quantitative questionnaire study with a total of 149 victims of

bullying and a control group (N = 81), it was investigated whether bullying victims

use specific conflict management strategies more often compared with individuals

who are not bullied, and whether coping strategies used by successful copers with

bullying differ from those of the unsuccessful copers. Successful copers were

those victims who believe that their situation at work has improved again as a

result of their coping efforts. The qualitative data showed that most victims started

with constructive conflict-solving strategies, changed their strategies several

times, and finally tried to leave the organization. In the interviews, the victims of

bullying most often recommended others in the same situation to leave the

organization and to seek social support. They more often showed conflict

avoidance in the quantitative study. Successful victims fought back with similar

means less often, and less often used negative behaviour such as frequent

absenteeism. Moreover, they obviously were better at recognizing and avoiding

escalating behaviour, whereas in their fight for justice, the unsuccessful victims

often contributed to the escalation of the bullying conflict.

Workplace bullying or “mobbing” as it is called in many Continental European

countries, has become an important issue in Europe. Research started in Sweden

(e.g., Leymann, 1996), Norway (e.g., Einarsen, 2000; Einarsen & Skogstad,

1996), and Finland (e.g., Björkqvist, Österman, & Hjelt-Bäck, 1994; Vartia,

1996), and many other countries have followed in the meantime. Research was

done by Cowie et al. (2000), Hoel, Cooper, and Faragher (this issue), and Rayner

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/pp/1359432X.html

DOI:10.1080/13594320143000834

Requests for reprints should be addressed to Prof. D. Zapf, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-

Universität, Institut für Psychologie, Mertonstr, 17, 60054 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Email:

D.Zapf@psych-uni-frankfurt.de

498

ZAPF AND GROSS

(1997) in the UK; by Mikkelsen and Einarsen (1999) in Denmark; den Ouden

(1999) in The Netherlands; Kirchler and Lang (1998) and Niedl (1995, 1996) in

Austria; von Holzen-Beusch, Zapf, and Schallberger (in press) in Switzerland;

Mackensen von Astfeld (2000) and Zapf, Knorz, and Kulla (1996) in Germany;

Kaucsek and Simon (1995) in Hungary; and Cowie et al. (2000) in Portugal.

Outside Europe, bullying research has been carried out by Keashly, Hunter, and

Harvey (1997) in the US and Sheehan, Barker, and Rayner (1999) in Australia.

Research summaries (Einarsen, 2000; Zapf, 1999a) have come to the conclusion,

that bullying is an ubiquitous problem in most organizations with a prevalence

rate between 1% and 4% causing severe health damage in the victim of bullying.

Whereas most research on bullying so far emphasized the stress perspective,

there is comparatively little literature on bullying from the perspective of conflict

research. This will be done in the present article. The central research question is:

How do individuals cope with workplace bullying given that many bullying cases

have reached an advanced stage of conflict escalation? To give an answer to this

question we will deal with the stress and coping as well as with the conflict

management literature.

From a stress perspective, bullying behaviour as a subset of social stressors

(Zapf et al., 1996) can be conceptualized either as daily hassles (Kanner, Coyne,

Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981) or as critical life events, for example, when physical

or sexual violence is used or when substantial decision competencies are taken

away which may completely change the status of a person in the firm. These

social stressors negatively affect the individual’s health. Leymann (1993, 1996)

suggested an operational definition of bullying. To call it bullying, such negative

social behaviour should occur for at least half a year and at least once a week.

Bullying can start with an equal power structure. However, after some time, an

unequal power structure will result and limit the resources of the victims to

defend themselves (Einarsen, 2000; Knorz & Zapf, 1996). This may be so if a

person lacks skills to manage an escalating conflict or if he or she gets into an

outsider position and looses the support of other colleagues and supervisors.

Finally, if social stressors occur in a department, almost everybody will be

negatively affected after some time. However, bullying is usually targeted at

a particular person. These considerations led to the following definition of

bullying: Bullying occurs, if somebody is harassed, offended, socially excluded,

or has to carry out humiliating tasks and if the person concerned is in an inferior

position. To call something bullying, it must occur repeatedly (e.g., at least once

a week) and for a long time (e.g., at least 6 months). It is not bullying if it is a

single event. It is also not bullying if two equally strong parties are in conflict

(cf., Einarsen, 2000; Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996; Leymann, 1993; Zapf, 1999a).

In the present article we will follow this relatively strict definition of bullying. It

should be noted that other authors use less strict definitions with regard to the

time frame (less than 6 months) and the frequency of the bullying behaviour (less

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

499

often than once a week) (cf., Einarsen, 2000; Hoel, Rayner, & Cooper, 1999;

Zapf, 1999a)

Various studies have shown that bullying is not a passing problem. Given the

definition above, the minimum duration of bullying is 6 months. Leymann (1996)

reported an average duration of 15 months, Einarsen and Skogstad (1996)

reported 18 months, and Zapf (1999a) summarized various German studies

reporting mean bullying durations of between 29 and 46 months. Taking these

studies together, it can be concluded that a substantial number of all bullying

cases last longer than 2 years. These kinds of long-lasting and badly managed

conflicts that go far beyond everyday quarrelling, are at the centre of this paper.

Some authors suggested that in the context of bullying the conflict situations tend

to escalate (e.g., Einarsen, 2000; Leymann, 1996) and get worse in the course of

time. In the study of Zapf (1999a), indirect evidence could be found for this in

that the duration of bullying correlated positively with the numbers of bullies. We

will argue that bullying according to the definition mentioned previously is an

escalated conflict situation. This escalated conflict situation is a non-control

situation for the victim. Therefore, otherwise successful conflict management

strategies (Rahim & Magner, 1995; Thomas, 1992) or successful stress manage-

ment strategies such as active problem solving (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) will

not prove successful when applied in an escalated bullying situation. To support

our proposition we will first describe some conflict escalation models referred to

in the bullying literature. Then we will deal with conflict management and coping

strategies.

CONFLICT ESCALATION MODELS

If a conflict is defined as “the process that begins when one party perceives that

the other has negatively affected, or is about to negatively affect, something that

he or she cares about” (Thomas, 1992, p. 653), there is probably general agree-

ment that bullying falls under this conflict definition. Bullying can be described

as a certain subset of conflicts. Whereas conflicts can even be positive (task-

related or cognitive conflicts, de Dreu & van de Vliert, 1997; Tjosvold, 1991),

can occur between parties of equal power, can consist of only one conflict

episode, and can be resolved relatively quickly, conflicts underlying bullying are

negative for the victim, result in an unequal power structure, consist of a series of

related conflict episodes and last for a long time according to the definition of

bullying presented earlier. Leymann (1996) not only suggested that there should

be a minimum duration to speak of bullying. He also suggested a model

describing the typical process of bullying which showed parallels with escalation

models in conflict research. Another model was suggested by Björkqvist

(1992). Leymann’s (1993, 1996) model differentiated between various stages

over time.

500

ZAPF AND GROSS

Critical incidents. Leymann argued that the starting point of bullying is

typically a triggering situation which is most often a conflict. Not much is known

about what exactly leads from a conflict into a bullying situation. Hypothetically,

this first bullying phase (which according to Leymann is not yet bullying) may be

very short.

Bullying and stigmatizing. In the next phase, the person is stigmatized and

becomes the victim of bullying in the sense of the definition of bullying given

earlier. Bullying activities may comprise quite a number of behaviours, which, in

normal interaction, are not necessarily indicative of aggression or expulsion.

However, being subjected to these behaviours almost on a daily basis and for a

very long time, they can change their meaning and may be used in stigmatizing

the person in question. Single bullying behaviours, regardless of their normal

meaning in day-to-day interaction, share the intent to “get at a person” or punish

him or her. Thus, damaging the victim is the main characteristic of these events.

Personnel management. In the next stage, management steps in—making

the case “official” in the organization. According to Leymann, the previous

stigmatization of the victim makes it easy to misjudge the situation as being the

fault of the subjected person. Management tends to accept and overtake the

position of the bullies and their negative view of the victim. From the point of

view of the management, it is often easier to get rid of the victim. This is

particularly so if more than one bully is involved, which is very often the case

(Zapf, 1999a). One person, the victim, can more easily be removed and be

replaced than can a group of bullies. According to Leymann, these actions often

imply the violations of rights by personnel management. In this phase, the

subjected person ultimately becomes marked and stigmatized. Colleagues and

management tend to create explanations why bullying developed. They hold

personal characteristics of the victims responsible rather than environmental

factors.

Expulsion. The final stage of bullying is, according to Leymann (1993), the

expulsion from the organization. The threat to become expelled is made

responsible for the development of serious illnesses (Groeblinghoff & Becker,

1996; Leymann, 1996; Leymann & Gustafsson, 1996), which cause the victims

to seek medical or psychological help. However, the subjected person can be

very easily incorrectly diagnosed by some professionals who do not believe the

victim. Some of the misdiagnoses according to Leymann are paranoia, manic

depression, or character disturbance. In recent years, Leymann included this

misdiagnosis as an extra stage in his model (Leymann, 1996).

Leymann described bullying as a situation where the victims can do little to

solve the problem. They become stigmatized. The expulsion from the firm is

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

501

described as the unsuccessful end of the story. Leymann does not go into details

with regard to conflict management or stress management strategies. However,

because the expulsion from the firm is described as against the interest of the

victim, one can assume that in Leymann’s view, the victims’ attempts to solve the

problem are all considered to be unsuccessful.

Björkvist (1992, after Einarsen, 2000) suggested a three-phase model of

bullying with a focus on the intensity of bullying behaviour. In the first phase,

indirect strategies of bullying such as spreading rumours or permanently

interrupting the victims are used aiming at degrading the victim. In the second

phase, more direct acts of aggression appear. The person is isolated, humiliated in

public, and people make fun of him or her. By degrading the victim, the bullies

make sure that their behaviour is justified and that they do not have to feel guilty.

In the third phase, extreme forms of direct aggression and power are used. The

victim is accused of being psychologically ill, he or she is blackmailed, and

threats to distribute intimate knowledge are put forward. Björkqvist et al. did not

discuss the conflict management behaviour of the victim; instead they focused on

the conflict escalation process as characterized by more and more threatening

measures directed against the victim. Björkqvist’s and Leymann’s models have

in common that bullying becomes worse and worse in the course of time, and, in

its final stage, it leaves the victim in a powerless situation where he or she cannot

successfully apply coping strategies which might end the conflict situation.

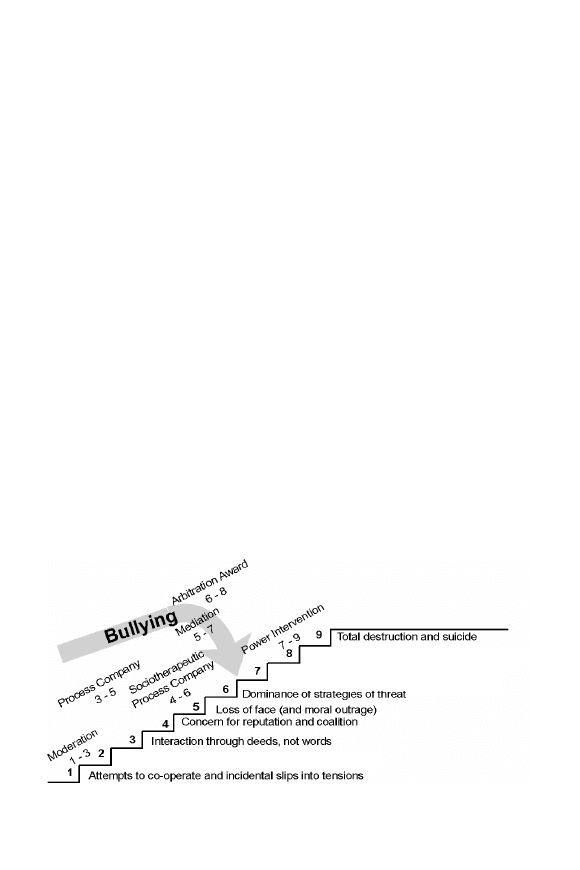

The use of more and more severe means to harm the other party is also

characteristic for the conflict escalation model of Glasl (1982, 1994; see also

Neuberger, 1999) which was developed before research on workplace bullying

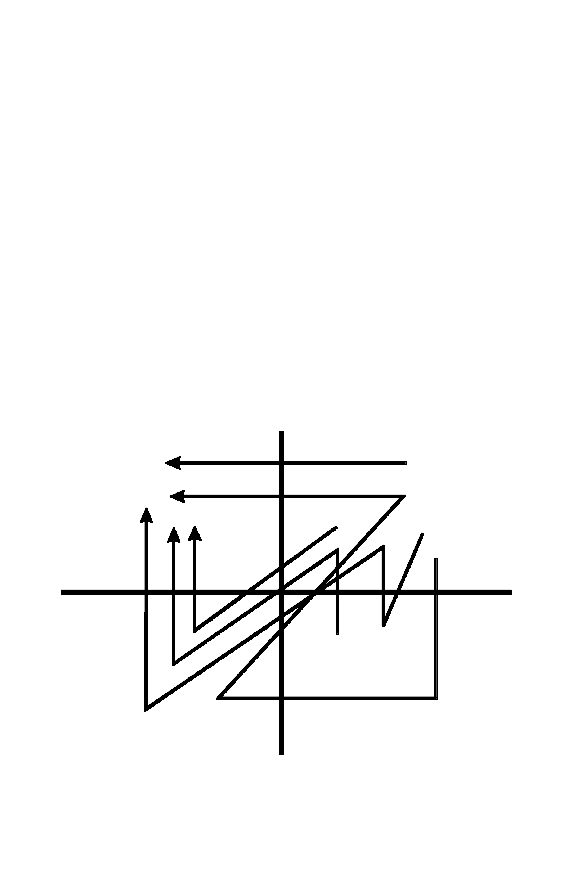

started. Glasl’s model (Figure 1) of “levels of conflict escalation” differentiates

between three phases and nine stages.

Figure 1. The conflict escalation model of Glasl (1994).

Systematic destructive campaigns against

the sanction potential of the other party

Attacks against the power nerves of the enemy

Polarization and debating style

502

ZAPF AND GROSS

Phase 1: Rationality and control. Glasl’s model starts with a rational

conflict. Conflicts are perceived to be inevitable in organizations and under

certain circumstances they may even contribute to innovation and performance of

an organization (e.g., de Dreu, 1997). In the first phase the conflict parties are all

interested in reasonable solutions of the problems they have to deal with. They

interact with some degree of co-operation and deal mostly with impersonal topics

or issues. The conflict parties are aware of tensions but try to handle them in a

rational and controlled manner. The three stages of this phase differ in that stage

1 is characterized by attempts to co-operate, however, accompanied by incidental

slips into tensions and frictions, stage 2 by polarization and debating style, and

stage 3 by interaction through deeds instead of words.

Phase 2: Severing the relationship. The next phase is achieved when the

original conflict has more and more vanished and the relationship between the

parties has become the main source of tension. Distrust, lack of respect, and overt

hostility evolve. In this phase the parties find it more and more difficult to solve

any conflicts together and they attempt to exclude each other. The fourth stage is

characterized by concern for reputation and coalition, the fifth by the loss of face

(and moral outrage), and the sixth by the dominance of strategies of threat.

Phase 3: Aggression and destruction. In the third phase confrontations

become very destructive. The other party is viewed as having no human dignity,

and any attempt to achieve positive outcomes is blocked. The parties would

risk their own welfare, or even existence, in order to damage or destroy the

other. Glasl argued that this third phase would hardly be reached in an

organization.

One central assumption of this article is that bullying in its final stage is a

boundary phenomenon between phase 2 and phase 3 (see Figure 1). That is,

severe cases of bullying as discussed in this article can be characterized by the

culprits’ firm belief that it is impossible to collaborate with the victim anymore.

The logical consequence is then that in the interest of the culprits, the victim

should leave the firm. This corresponds with Leymann’s (1993, 1996) final phase

of the bullying process. It also corresponds with research on the reasons of

bullying. In a study of Zapf (1999b), the most often agreed upon reason for

bullying from the victims’ point of view was “they wanted to push me out of the

firm”. Einarsen and Skogstad (1996) found that victims of long-lasting

harassment were more frequently attacked than victims with a shorter history.

Leymann (1993) argued that many victims did not realize for a long time what

happened to them. Their case had already escalated quite a bit until they started to

understand in what situation they were. Bullying may not always follow the stage

model of Glasl (1994). Rather, because of the heterogeneity of causes of bullying

(Einarsen, 1999; Zapf, 1999b), there may be a lot of variants. Steps in Glasl’s

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

503

model may be left out and bullying may directly begin at higher levels of

escalation.

So far, there has been little empirical research in the bullying literature about

the course of conflict escalation. Therefore, we were interested first, whether the

conflict situation is, indeed escalating. One indicator for this is whether bullying

behaviour does increase in the course of time (cf., Einarsen & Skogstad, 1996).

We wanted to know whether bullying victims with a longer period of being

bullied were more frequently bullied compared with victims of a shorter period.

Moreover, we were interested whether there is some evidence that bullying cases

follow the conflict escalation model of Glasl (1994) described earlier.

THE MANAGEMENT OF CONFLICTS

IN THE WORKPLACE

The next question was: What do bullied people do in escalated conflict

situations? Although conflicts at work are a daily phenomenon, only a few

studies analysed conflict management strategies concerning this particular group

of organizational conflicts. The conflict management (e.g., de Dreu & van de

Vliert, 1997; Thomas, 1992) and stress management literature (e.g., Lazarus &

Folkman, 1984; Schönpflug, 1983; Semmer, 1996) have much in common,

which is of no surprise because many stressful situations are social conflicts.

Moreover, some kind of problem solving plays an important role in both areas. In

the following we will concentrate on the conflict management literature, but, in

cases, will also draw upon the stress management literature.

A widespread model differentiates conflict handling strategies according to

how one attempts to satisfy one’s own concern and the concern of the other party

(Blake & Mouton, 1964; Thomas, 1992) resulting in five conflict strategies

in interactions with supervisors, colleagues, and subordinates: integrating,

obliging, dominating, avoiding, and compromising. Integrating involves high

concern for one’s own interests as well as for the interests of the other party and

aims at collaboration. Obliging involves low concern for one’s own interests and

high concern for the other party. Playing down differences belongs to this

strategy. Dominating involves high concern for one’s own interests and low

concern for the interests of the other party. An example is forcing behaviour to

win one’s position. Avoiding is associated with low concern for both parties and

withdrawal behaviour and ignoring conflicts are typical behaviours. There is

empirical evidence for the psychological validity of this differentiation (Rahim &

Magner, 1995; Thomas, 1992). Therefore, we were interested whether the

victims of bullying showed a specific pattern of these strategies and whether

certain strategies were preferred in comparison to non-victims. Moreover, we

were interested in what kind of strategies the victims suggest others should use in

order to cope with bullying.

504

ZAPF AND GROSS

Conflict research shows that individuals most often start with constructive

strategies to solve conflicts. In some cases they may use passive strategies and

wait and see whether the conflict situation disappears again (Martin &

Bergmann, 1996; Withey & Cooper, 1989). Given the unequal power structure in

bullying and the fact that bullying victims have difficulties to defend themselves

according to the definition of bullying which also implies that they have little

control in the conflict situation, one can assume that obligation and conflict

avoidance are preferred strategies (cf., Keashly & Nowell, in press). Dominating

requires power which is not available for the bullying victims. Problem-oriented

strategies such as integrating require the possibility to influence the overall

situation which is also difficult for the victims. This assumption is supported by

empirical findings showing that problem-solving oriented strategies of conflict

management are little successful if the conflicts are not task oriented anymore (de

Dreu, 1997). Previous research on bullying (Knorz & Zapf, 1996; Niedl, 1996)

supports this view. In these studies bullying victims tried various active and

passive conflict management strategies which, however, did not prove

successful, otherwise bullying would have been stopped. Only in exceptional

cases could the conflicts be solved. In these cases, the victims either left the

company, or they tried to survive somehow in the organization, mostly using

some kind of withdrawal behaviour.

In stress research it has been shown, that control is an important moderator for

successful coping (Semmer, 1996). Control means to “have an impact on the

conditions and one’s activities in correspondence with some higher-order goals”

(Frese, 1989, p. 107). Although active coping proves useful in situations with

high control, this is not so for low control situations, as in the case of bullying. If

the situation cannot be changed, then intrapsychological strategies such as

cognitive restructuring, relaxation strategies, but also denial, avoidance, or

simply “doing nothing” may prove more useful (e.g., Begley, 1998; Lazarus &

Folkman, 1984; Semmer, 1996; Weber, 1993). Coming into an inferior position

with difficulties to defend oneself has been described as a core characteristic of

bullying (Einarsen, 2000; Leymann, 1993). If an individual lacks power and

control in a situation, then active approaches are neither possible nor useful.

Rather, the victim has to apply other, mostly passive, strategies to survive.

In a study of Niedl (1995, 1996), the EVLN-model of Withey and Cooper

(1989) was chosen to analyse changes in the behaviour of bullying victims. The

EVLN model comprizes four reactions: exit, voice, loyalty, or neglect, which can

be described by the two dimensions active vs. passive and constructive vs.

destructive. People who are dissatisfied can focus their attention on non-work

interests (passive and destructive reduction of commitment: neglect). Moreover,

they may try to improve their situation through voice (active and constructive

problem solving). Another possibility is to passively support the organization

with loyalty (passive, but constructive hope of problem solving). Finally,

employees may quit their job (exit which is active, but destructive from the view

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

505

of the organization). According to this model, dissatisfied employees choose

those acts that are efficacious and whose costs are low for the individual. Withey

and Cooper characterized these reactions as independent factors, which could be

confirmed by a varimax rotation factor analysis. Although the reactions of some

individuals might not change and although there are a lot of possible variations

how to change the behaviour, they found two different behavioural sequences.

Niedl (1995, 1996) used this model in a small sample of participants of a 6-week

rehabilitation programme at a German hospital. In this interview study, most of

the patients first reacted with some kind of constructive coping (voice, loyalty).

After perceiving that their problem-solving attempts were not successful, the

reactions turned to “destructive” forms such as leaving the firm (exit) or reducing

commitment (neglect). Most of the “final reactions” were of this type. Niedl

(1996) concluded that the individuals surveyed did not cope using simple “fight

or flight” strategies. Rather, a more complex sequence of reaction patterns could

be observed. Given these findings we were interested whether we were able to

replicate Niedl’s study. Based on the theoretical considerations presented earlier

and on Niedl’s empirical findings, we expected that victims of bullying would,

first, use a series of both active and passive conflict management strategies.

Second, we expected that because of the unequal power situation which leaves

little control to the victim, active and constructive strategies such as voice do not

prove successful.

In an earlier study (Knorz & Zapf, 1996), we compared victims whose

situation continued to worsen with those who stated that their situation had fully

improved again at the time the victims responded to the questionnaire or the

interviews. We identified those people who successfully coped with bullying and

those whose conflicts got worse and worse. Four out of twenty-one participants

who took part in a qualitative interview were identified as successful copers.

They agreed in showing the following three characteristics: (1) They defined a

clear boundary and made up a decision to get out of the bad game called bullying.

(2) Personal stabilization: Because most of the victims were mentally in a bad

shape and suffered from a lack of personal resources, they sought for a period of

regeneration, e.g., by longer “time out” (sick leave) and psychotherapy (in

contrast to frequent short-term absenteeism). (3) In each case, objective changes

of the work situation by intervention of a third party (usually higher manage-

ment) took place. Although some bullying victims reported to have coped

successfully with their case, nobody was able to achieve this without external

help. These objective changes typically implied that bullies and victims were

separated with regard to space, assigning either the bully or the victim to another

work unit or department. If there was more than one bully, it was usually the

victim who was relocated. In this case, management tried to find adequate work

tasks comparable to those the victim had before. Not a single person in this first

study was able to restore the situation they had before the bullying episode.

Those people who said that their situation was okay again, indicated that this was

506

ZAPF AND GROSS

obviously only possible by some organizational change managed by a third

party, typically members of the higher management. Based on these con-

siderations and previous research, we were interested in how far “successful”

bullying victims, which are those who report that their work situation was almost

as good as it was before bullying started, differ in their use of coping strategies

from those victims who report that, in spite of their coping efforts, their overall

situation got even worse. In summary, we were interested in the following

research questions:

(1) Is there evidence that bullying is an escalating conflict situation in terms

of an increased frequency of bullying in the course of time?

(2) Are there typical courses of conflict escalation in the case of workplace

bullying?

(3) Are there typical patterns of conflict management among victims with

regard to the two-dimensional taxonomy of conflict strategies of Thomas

(1992) (dominating, avoiding, obliging, compromising, and integrating)

and the EVLN-model of Withey and Cooper (1989)?

(4) Is there a difference in the use of conflict management strategies between

victims and non-victims?

(5) What strategies would the victims recommend other victims to use?

(6) Do “successful” victims of bullying differ in their coping behaviour from

“unsuccessful” victims?

In the results section we will first present results based on a qualitative study

referring to the research questions 2, 3, and 5. In the following quantitative study

we will present data related to research questions 1, 4, and 6.

METHOD

Sample

The research questions were studied using both a qualitative and a quantitative

approach. The quantitative sample consisted of three subsamples. The first

subsample (Konstanz sample) was collected between October 1995 and July

1998 and consisted of 96 bullying victims. They were recruited by means of

newspaper articles on bullying, local broadcasting, bullying self-help groups,

and by the help of a German organization called “Society against Psycho-social

Stress and Mobbing GpSM”. Mean age was 44 years, 55% were women. A

control group (N = 37) was collected by a snowball system starting with persons

personally known to members of the research project. From those persons we got

addresses of other persons who were prepared to take part in the study. In so far,

the control sample was a convenience sample. However, it was tried to match the

control group with the bullying group according to gender, age, and education.

That is, we systematically searched for certain people to improve the match,

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

507

e.g., by systematically approaching people with higher or lower education. Mean

age of this control group was 36 years, 62% were women.

The second subsample (N = 118) was collected by the Deutsche Angestellten-

Gewerkschaft DAG, Stuttgart. The DAG published an article about the bullying

project in an internal journal. Interested job stewards then asked for question-

naires to distribute them. Here, the mean age was 42 years, and 55% were

women. Although the Konstanz sample consisted of more severe bullying cases

(longer mean duration of bullying, higher scores on the bullying scales), the

results of both samples were very similar.

The third subsample of the quantitative study was identical with the sample of

the qualitative study. That is, we distributed a standardized questionnaire and

carried out structured qualitative interviews. This sample was recruited with the

help of the “Association against psychosocial stress and mobbing”, another

German organization dealing with workplace bullying. The sample consisted of

20 bullying victims aged between 35 and 59 years. One person was excluded

from the sample. Fifteen of the remaining nineteen individuals were women.

About 25% of this sample worked in the public administration and another 25%

in the education sector. Fifteen per cent worked in the health care sector, another

15% in the service industry and 10 % in the chemical industry.

For reasons of parsimony and clarity the three samples were collapsed for the

quantitative analyses. The total sample consisted of 268 participants, of which

149 were victims of bullying according to the criteria described later, 81

belonged to the control group. They fulfilled neither of the criteria. 38 partici-

pants fulfilled one or two criteria. They were excluded from the analyses

comparing victims and non-victims and successful and unsuccessful victims.

Sixty-six per cent of the bullying sample and forty-nine per cent in the control

group were women, the mean age of the bullying sample was 45 years, and the

mean age of the control group was 37 years. Twenty-six per cent of the bullying

sample (20% of the control sample) had a “Hauptschulabschluß” (lower stream

school-leaving certificate), 29% (27%) had “mittlere Reife” (middle stream

school-leaving certificate), 11% (20%) had “Abitur” (high school diploma

qualifying for university entrance), and 34% (33%) some type of university

degree.

Instruments

Bullying was measured with a list of items adapted from the German translation

of the Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terrorization (LIPT; Leymann,

1990). These items included bullying by organizational measures (e.g., question-

ing a person’s decisions; judging a person’s job performance wrongly or in an

offending manner; assigning degrading tasks to the person concerned), social

isolation (e.g., one does not talk to the person concerned; being treated like air),

attacking the private sphere (e.g., permanently criticizing a person’s private life;

508

ZAPF AND GROSS

making a person look stupid; suspecting a person to be psychologically

disturbed), verbal aggression (e.g., shouting at or cursing loud at a person; verbal

threats), physical aggression (e.g., threat of physical violence; minor use of

violence), and rumours (e.g., saying nasty things about a person behind his/her

back) (cf., Zapf et al., 1996 for details).

To measure the escalation of the bullying cases and strategies applied

by the victims we used items developed by Knorz and Zapf (1996). To measure

conflict behaviour we used a German translation of the Rahim Organizational

Conflict Inventory (ROCI II; Rahim & Magner, 1995, appendix) measuring the

five styles of conflict handling with regard to interactions with supervisors by

using 26 items and using a five-point Likert-scale on which a high degree

represents a frequent use of this style of conflict handling. Items 20 and 21 in the

appendix of Rahim and Magner were excluded from the scales because of

reliability problems. The results were, however, not different if these items

were not excluded. Psychometric properties of the scales are summarized in

Table 1.

Moreover, coping strategies of successful and unsuccessful victims were

measured using a list of single-item measures developed by Knorz and Zapf

(1996). This list of items was developed on the basis of the stress and coping and

the conflict management literature as well as on preceding qualitative interviews

with victims.

u

TABLE 1

Scale characteristics of study variables

Mean

SD

Coefficient

No. of

alpha

items

Bullying (sample: bullying victims, N = 144–149)

Organizational measures

2.92

0.96

.85

13

Social isolation

2.64

1.07

.73

4

Attacking private sphere

2.20

1.00

.69

5

Verbal aggression

3.31

0.95

.74

6

Rumours

4.19

1.43

.74

2

ROCI II (total sample, N = 268)

Dominating

2.75

.90

.76

4

Compromising

3.59

.80

.63

3

Integrating

3.67

.82

.87

7

Obliging

3.44

.69

.80

6

Avoiding

3.08

.93

.84

6

Range of all scales is between 1 and 5.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

509

Procedure

To define the bullying group, three criteria were combined that were used in the

literature (Zapf, 1999a). In line with Leymann (1993, 1996) bullying had, first, to

last at least 6 months, and, second, negative acts as operationalized in a list of

bullying items had to occur at least once a week. This was operationalized by two

items (“How frequent were these acts in all?” and “How long was the duration of

the bullying behaviours described above?”) presented after the list of bullying

acts. The third criterion was that the participants had to agree that they were a

victim of bullying according to the definition mentioned earlier in this article

which was presented in the questionnaire after the list of bullying items (response

format “yes” and “no”).

Successful and unsuccessful victims were differentiated on basis of the item

“Have you been able to improve your situation by your behaviour?” Those who

responded “yes, completely” (9 out of 149) were defined to be successful, those

who responded “no, the situation got even worse” (67 out of 149) were defined as

unsuccessful. In all other cases, the situation either did not change or only

slightly improved or deteriorated.

The participants for the qualitative study received the questionnaire and were

interviewed using a semi-structured interview form. All these 20 interviews were

tape recorded and then literally transcribed. One person was excluded because of

serious psychological complaints that questioned the reliability of the interview

(case 11). The interview manual was based on the manual developed by Knorz

(1994). This manual served for structuring the interviews but the questions were

formulated freely and in unclear situations it was inquired again to get more and

detailed information. This semi-structured procedure should allow a free

description of the bullying experiences. The manual actually consisted of 32

questions, which focused on the career and the workplace, the bullying process

(bullying actions, coping strategies, and development), consequences of the

bullying actions, appraisal of coping strategies, and of the social support and their

professional perspective for the future. The questions used in this article focused

especially on the bullying process. Special attention was paid to the starting point

of bullying, its cause, its development, bullying actions, coping reactions and

their changes during the process, potential phases of bullying, and the victims’

advice how to cope with bullying, for other bullying victims.

To analyse the conflict strategies, raters rated the interview material and

assessed the reported conflict management behaviour according to the strategies

based on the definitions given in Rahim and Magner (1995). Moreover, part of

these semi-standardized interviews were theoretically based on the EVLN-model

by Withey and Cooper (1989; see also Niedl, 1996). The participants were

requested to reconstruct their process from that point on from where they had

510

ZAPF AND GROSS

perceived bullying for the first time. The resulting qualitative data where then

structured according to the EVLN-model. Coping strategies were identified with

regard to the EVLN-model of Withey and Cooper (1989), which were then

assessed by two independent raters resulting in a typical pattern of coping

strategies in the time course for each participant.

RESULTS

Qualitative interview results

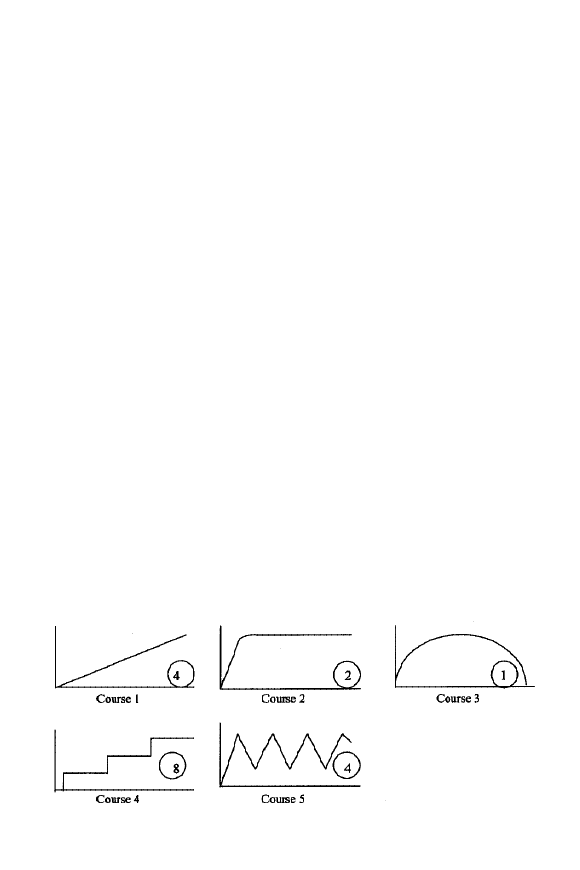

The first research question analysed in the qualitative study referred to the

escalation process of bullying. Five different courses of bullying were presented

(Figure 2). Four participants reported that their bullying case continuously

escalated (course 1) . The case of two participants escalated very rapidly and

continued on an escalated level (course 2). In one case the conflict continuously

escalated, but continuously de-escalated again after some time (course 3). In

eight cases which is almost 50% of the sample, the conflict escalated in stages

(course 4) as predicted by Glasl’s (1994) model, and in four cases escalation and

de-escalation alternated several times (course 5). Taken together, 14 out of 19

participants reported that bullying escalated more and more as time went by.

One result of the qualitative interviews was that it was not always the bullies

who contributed to the escalation of the conflict. In several cases, the bullying

victims were not at all aware of the provocative or threatening potential of their

own behaviour. The most common case was to start a legal complaint against a

supervisor. In the interviews, the victims sometimes mentioned “en passent” that

they started such a complaint as if it were nothing. They were surprized when

asked what they had expected about how their relation to the supervisor would be

like in the future after this complaint. It seemed that they had not thought about it.

This kind of behaviour was not found among by the successful victims.

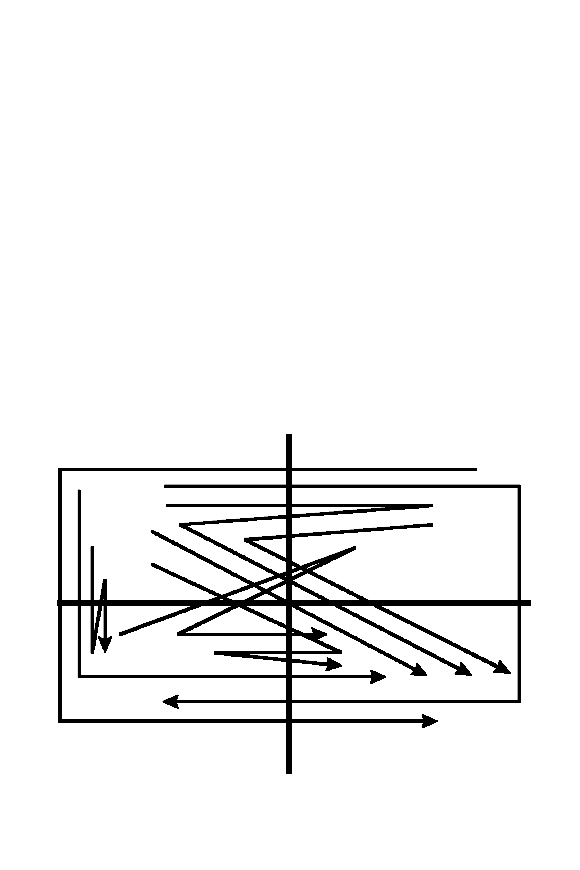

Our next research question referred to the conflict strategies of Rahim and

Magner (1995). The results are shown in Figure 3. Patterns of conflict manage-

Figure 2. Courses of conflict escalation: Results from the qualitative study.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

511

ment behaviour are represented by the various lines in the figure. The numbers of

each participant show how many of them who chose a particular sequence of

conflict management strategies. The relative position within a quadrant is

without meaning. The majority of the participants (14 out of 19) started with

integrating, two started with dominating, and three with obliging. Two partici-

pants ended up with dominating behaviour; however, the majority (17 out of 19)

ended up with conflict avoiding. Only two participants directly changed from

integrating to avoiding. Most of the participants changed their conflict strategy

several times using integrating most often. This overall pattern suggests that the

victims of bullying first tried an active and constructive way to solve the conflict

which was, however, not successful. Remarkably, 10 out of the 19 participants

tried to oblige. That is, they tried to adapt to the other party and give up their own

interests. However, this was also not successful to end the conflict. Only two

persons used compromising. The majority ended up in trying to escape the

conflict after having experienced that their efforts did not lead to any solution.

As described in the method section, the qualitative data were also structured

by the EVLN-model and used to analyse the process of bullying with regard to its

In te g ra tin g

O b lig in g

D o m in a tin g

A v o id in g

C o m p ro m is in g

10 16 18

12

14

5 6 8 9

15 17

2 3 4

7

1 13

19 20

Figure 3. Conflict management strategies of Rahim and Magner (1995): Results from the

qualitative study.

512

ZAPF AND GROSS

organizational effects. Exit stands for active but destructive behaviour such as

quitting the job; voice implies active and constructive problem solving; loyalty

consists of passive but constructive hope of problem solving; and neglect stands

for passive and destructive reduction of commitment. The results in Figure 4

show patterns of conflict management behaviour represented by the various

lines. The number of each participant show who chose a particular sequence of

conflict management strategies. Each line in the figure stands for a group with

similar conflict courses. There were five different courses of conflict

management. The most frequent course was VLVNE (voice–loyalty–voice–

neglect–exit). The majority started with active strategies (voice) to constructively

solve the problem. Only three out of nineteen individuals showed a passive

behaviour (loyalty) in the beginning waiting for a solution. Most often, loyalty

was followed by voice, voice was followed by neglect, finally followed by exit.

Most participants changed their strategy several times. There were only two

persons who directly chose exit after voice. They actively tried to change their

situation for a long time but were not successful. Successful victims of this study

did not differ from the unsuccessful victims in the choice and course of conflict

management strategies. In sum, these qualitative analyses showed that the

E X IT

V O IC E

N E G L E C T

L O Y A LT Y

A c tiv e

P a s s iv e

D e s tru c tiv e

C o n s tru c tiv e

7 1 0 1 6 2 0

1 3 1 4

1 2 3 5 8 9

4 1 8 1 9

1 2 1 5 1 7

Figure 4. Conflict management strategies according to the EVLN-Model of Withey and Cooper

(1989): Results from the qualitative study.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

513

victims were not successful in applying active and constructive strategies to

solve the conflict but mostly ended up in exit or conflict avoidance behaviour.

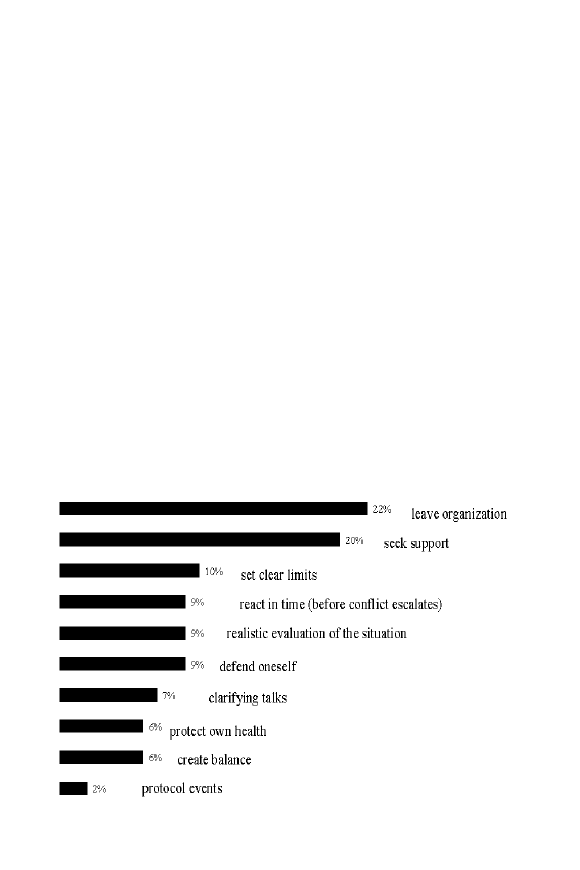

Finally, the victims were asked what kind of advice they would give to

somebody who is in a similar situation of being bullied. The answers were

categorized and the results are shown in Figure 5. Leaving the organization was

the most often recommended strategy, followed by seeking support. These

results correspond with the analyses according to the EVLN model.

Results of the quantitative study

First, it was investigated whether the frequency of being bullied increased the

longer a person was bullied which was considered an indication of conflict

escalation. Results are presented in Table 2. In the table, groups of victims with

increasing duration of bullying are compared. Significant differences occurred

for bullying by organizational measures, attacking the private sphere, and

rumours. A tendency appeared for social isolation in the expected direction. With

the exception of bullying by organizational measures, the group of victims

bullied more than 3 years reported the highest frequency of being bullied. All in

all, a tendency of being bullied more the longer bullying lasted, occurred for three

out of five bullying strategies. A systematic decrease of being bullied in the

course of time could not be observed.

Next, the use of Rahim and Magner’s (1995) conflict strategies of victims and

non-victims were compared (see Table 3). There was a tendency that victims

used dominating less often than the control group, p = .09. As expected they used

Figure 5. Frequency of suggestions of victims how to cope with bullying.

514

ZAPF AND GROSS

conflict avoidance as a passive strategy significantly more often than did

the control group. No differences occurred for obliging, compromising, and

integrating.

Next, in replicating Knorz and Zapf (1996), coping strategies were analysed

according to how often they were used by successful and unsuccessful victims of

bullying. Results are shown in Table 4. To make the comparison easier, the data

of Knorz and Zapf (1996) are presented as well. First, it should be noted that only

6% of the sample were “successful” victims according to the criterion described

earlier. This was even lower than in the sample of Knorz and Zapf, where six out

of fifty (12%) could be identified as successful.

Looking at the overall samples, talking with the bullies was the most often

used strategy. However, this strategy was significantly more often used by the

unsuccessful victims supporting the qualitative results that voice behaviour did

not prove successful. Moreover, fighting back with similar means, which is

another active strategy, was not used at all by the successful bullying victims and

was significantly different from the unsuccessful victims in the present sample.

The same was true for frequent absenteeism at work. It should also be noted that

the successful victims in both samples did not use drugs. Finally, the mean

duration of bullying of the successful victims (24 months, SD = 24) was

significantly shorter than the mean duration of the unsuccessful victims (49

months, SD = 39, p < .05).

DISCUSSION

The present study analysed bullying from a conflict and conflict management

perspective. In the literature, bullying has been described as an escalated conflict

situation. When bullying has reached its final stage, bullies and victims typically

see little chance to work together anymore and many victims are convinced that

the bullies want to expel them from the firm. In the present study, quantitative

TABLE 2

Conflict escalation and the frequency of bullying

Duration of bullying (in months)

<6

³

6 and

³

12 and

³

24 and

³

36

F (df=4)

<12

<24

<36

Organizational measures

2.49

2.78

2.64

3.22

3.09

2.54*

Social isolation

2.26

2.41

2.43

2.68

2.92

2.24

a

Attacking private sphere

2.00

1.75

1.89

2.35

2.66

7.11**

Verbal aggression

3.28

3.16

3.06

3.41

3.55

1.74

Rumours

4.29

3.53

4.23

4.10

4.67

4.06**

*p < .05, **p < .01.

a

0 = .067.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

515

analyses showed that three out of five bullying strategies occurred more often for

bullying with a longer duration, indicating that bullying is escalating in the

course of time. Thus, the study replicates previous findings of Einarsen and

Skogstad (1996). Moreover, the qualitative data show that most of the bullying

cases escalate continuously or in stages. During the development of the conflict,

a variety of active and passive conflict management strategies are applied,

however, they do not prove successful. Leaving the organization is, therefore, the

ultimate reaction of many victims of bullying. In the quantitative analyses

bullying victims use conflict avoidance as a passive strategy more often than the

participants in the control group. Only a very few victims of bullying could be

identified who report that they succeeded in being again in a situation as good as

it was before the bullying started. Again, the successful victims tended to use

active direct strategies less often than the unsuccessful victims. Moreover, they

tried to make no mistakes and to be as correct as possible. One interpretation is

that these persons were particularly sensible not to contribute to the further

escalation of the conflict. Rather, they tried to de-escalate the situation by their

behaviour.

The results of the present study support the view that bullying in an advanced

stage is a non-control situation for the victim. Leaving the organization or

separating bully and victim seem to be the only solution available. Taking these

findings together, active strategies, which imply the direct confrontation with the

bullies, and inadequate passive strategies, which might harm the victim in the

long run (such as drug use and strategies that would weaken the victim’s position

and that would give the bullies even more possibilities to negatively affect the

victims such as frequent absenteeism from work), were used less often by the

successful victims. This result is in line with Aquino (2000), who found that the

TABLE 3

Use of conflict management strategies of victims

and control group

Bullying victims

Control group

(139 < N <143)

(N = 80)

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Dominating

2.65

a

0.93

2.86

a

0.82

Compromising

3.37

0.86

3.39

0.63

Integrating

3.67

0.84

3.77

0.74

Obliging

3.49

0.74

3.38

0.61

Avoiding

3.18

b

0.98

2.80

b

0.78

a

means were significantly different, p = .09, T = 1.76, df = 219.

b

means were significantly different, p < .01, T = 3.16, df = 194.8 for

inhomogeneous variances.

516

ZAPF AND GROSS

516

T

A

B

LE

4

C

o

n

fl

ic

t m

an

ag

em

en

t

st

ra

te

g

ie

s

o

f s

u

cc

es

sf

u

l a

n

d

u

n

su

cc

es

sf

u

l b

u

lly

in

g

v

ic

ti

m

s

Pr

es

en

t s

tu

dy

Kn

or

z a

nd

Z

ap

f (

19

96

)

To

ta

l

Si

tu

at

io

n

Si

tu

at

io

n

D

iff

er

en

ce

To

ta

l

Si

tu

at

io

n

Si

tu

at

io

n

D

iff

er

en

ce

sa

m

pl

e

co

m

pl

et

el

y

wo

rs

en

ed

co

m

pl

et

el

y

sa

m

pl

e

co

m

pl

et

el

y

wo

rs

en

ed

co

m

pl

et

el

y

(N

=

1

45

)

im

pr

ov

ed

(N

=

6

7)

im

pr

ov

ed

vs

.

(N

=

5

0)

im

pr

ov

ed

(N

=

1

8)

im

pr

ov

ed

vs

.

(N

=

9

)

wo

rs

en

ed

(N

=

6

)

wo

rs

en

ed

Ite

m

(%

)

(%

)

(%

)

(C

hi

2

-te

st

)

(%

)

(%

)

(%

)

(C

hi

2

-te

st

)

Ta

lk

ed

w

ith

th

e b

ul

lie

s

77

44

82

*

66

33

89

*

Su

pe

rv

iso

r c

al

le

d

in

65

63

68

n.

s.

40

17

56

p

=

.1

0

W

or

ke

rs

’ r

ep

re

se

nt

at

iv

es

ca

lle

d

in

64

50

66

n.

s.

40

0

61

*

Si

tu

at

io

n

w

ith

b

ul

lie

s a

vo

id

ed

58

63

54

n.

s.

56

67

50

n.

s.

Ig

no

re

d

sit

ua

tio

n

at

w

or

k

46

50

51

n.

s.

50

67

50

n.

s.

Tr

ad

e u

ni

on

ca

lle

d

in

45

56

44

n.

s.

20

17

28

n.

s.

Ps

yc

ho

th

er

ap

y

44

50

49

n.

s.

16

17

17

n.

s.

Fo

ug

ht

b

ac

k

w

ith

si

m

ila

r

m

ea

ns

36

0

40

*

36

50

39

n.

s.

Fr

eq

ue

nt

ab

se

nc

e f

ro

m

w

or

k

32

0

34

*

24

0

28

p

=

.1

5

Lo

ng

-te

rm

si

ck

le

av

e

30

13

32

n.

s.

24

17

28

n.

s.

Em

pl

oy

ee

’s

n

ot

ic

e

23

13

29

n.

s.

14

0

22

n.

s.

D

ru

gs

22

0

25

p

=

.1

3

8

0

0

n.

s.

Tr

an

sf

er

to

o

th

er

jo

b

17

38

12

*

8

17

6

n.

s.

A

pp

lie

d

fo

r e

ar

ly

p

en

sio

n

6

0

11

n.

s.

6

0

6

n.

s.

*p

<

.0

5.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

517

use of active problem-solving strategies in escalated conflicts may actually

increase victimization, and it is in line with Rayner (1999) who found that open

discussion and information sharing with the bully increased the likelihood of the

bully retaliating against the victim. This result also corresponds with Glasl’s

(1994) recommendations for intervention measures in escalated conflict

situations. Glasl recommends moderation and process supervision techniques for

the early stage (1–5) and sociotherapeutic process supervision and mediation

techniques for advanced stages (4–7). Arbitration award and power intervention

are suggested for stage 6–9. If we assume that escalated bullying conflicts can be

located at stages 6 and 7, then the latter intervention techniques seem to be

adequate according to Glasl. Arbitration award and power intervention are law-

and power-based intervention measures rather than psychological ones. From the

qualitative reconstruction of the cases both of Knorz and Zapf (1996) and of the

present study, it can be concluded that these conflicts were solved by higher

management decisions that separated the victims from their perpetrators rather

than restoring the situation before bullying. These were obviously power-based

decisions and can be subsumed under Glasl’s (1994) non-psychological

intervention methods. That is, were these non-control situations not only from

the victim’s point of view; even for third parties it was not possible to execute

control and restore the situation before bullying. This interpretation is supported

by many anecdotal reports of professional helpers of bullying victims who often

are not able to find reasonable solutions for the bullying situation except

separating the conflict parties. Finally, the present data are in line with the

contingency model of third party intervention of Fisher and Keashly (1990; see

also Keashly & Nowell, in press). The authors propose that efforts at de-

escalation have to recognize the need to go down the conflict escalation ladder

stage by stage and apply the intervention methods of the next lower stage rather

than “jumping down” to the low levels of conflict escalation, e.g., by attempting

to solve the escalated conflict by rational discussion (e.g., calmly talking to the

bullies).

It should be noted that the results of the present study should not be used for an

overall assessment of conflict management strategies. For example, one should

not conclude that active problem-oriented conflict strategies, such as talking with

the other conflict party, are of little use. Research has shown the usefulness of

these strategies. Recalling that, on the one hand, frequency of bullying is between

1% and 4% in most organizations, and that, on the other hand, managers report

spending about 20% of their time dealing with conflicts (Thomas, 1992), it can be

concluded that by far the most conflicts are solved and that such conflict

strategies work reasonably well. However, in a few cases, these strategies do not

work. In such situations the conflicts tend to escalate and become bullying

according to the definition given in the introduction. In this sense a series of

failing conflict management attempts is a main characteristic of bullying (cf.,

Niedl, 1995). Thus, bullying describes a rather small percentage of conflicts

518

ZAPF AND GROSS

where otherwise successful strategies have failed. Theoretically, this is supported

by the models of Fisher and Keashly (1990) and Glasl (1994) who suggest that

strategies successful for solving conflicts at the lower level of escalation, do not

work in escalated situations.

Looking at the conflict management strategies used by successful victims, one

interpretation is that they successfully avoided the further escalation of the

conflict. The problem inherent in some of the more active conflict management

strategies such as calling in supervisors, works committee representatives, or the

trade union is that these strategies, although mostly legally justified, might be

perceived as threatening by the other party. As long as nobody is called in, a

conflict situation is “unofficial” and no legal action has to take place. If

supervisors or the works committee are informed they normally cannot ignore the

case. The bullies perceive this behaviour as “armament of the other party”, which

may lead to rearming on their side. At this point, psychological means (do not

directly confront the bullies; be careful in calling in supervisors or the trade

union; try to de-escalate) and legal means (use all juridical means available;

collect evidence for bullying behaviour; call in supervisors, trade union, or

lawyers; make the case official) to handle the conflict obviously diverge, even

into opposite directions. There are, of course, consequences for the consulting of

bullying victims. Depending on who does the consulting the case will likely go in

different directions. Applying legal means often implies to give up the job.

Therefore, the decision to involve legal means has to be made very carefully.

Sometimes, the victims themselves contribute to the escalation of the conflict,

for example, by starting a legal complaint against another person. These

observations support the importance of sensitivity for escalation processes which

is related to the ability of perspective taking, that is to see the conflict from the

perspective of the other party.

Our previous studies showed that changing workgroup or department seems

to be a reasonable solution for the successful victims of the present study,

whereas there is a dispute about leaving the firm as a potential strategy, because

the victims usually feel forced to leave the organization. Rather, they perceive

this as their last chance and often they accept working conditions (position, work

tasks, salary) substantially worse than in the firm in which they were bullied

(Knorz & Zapf, 1996; von Holzen-Beusch et al., in press). In addition, many

victims believe that it is highly unfair that the “victims” have to go and the

“perpetrators” are allowed to stay. Leaving the organization as a reasonable con-

flict outcome has, therefore, to be thoroughly discussed and planned to provide at

least some support for the victim. This stands in contrast to the management

behaviour reported by various authors (e.g., Einarsen, Raknes, Matthiesen, &

Hellesøy, 1994; Leymann, 1993). They describe that third parties or managers

often tend not to acknowledge the harm done to the victim. Rather, they often

justify their behaviour as fair treatment of a difficult person who cannot be

tolerated anymore at the workplace. Besides legal regulations and compensation

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

519

claims, it is a difficult psychological process to leave the firm, especially if

commitment is high (von Holzen-Beusch et al., in press), and the victims often

have to learn that their rights are not upheld and that the bullies get off

unpunished. In sum, the studies of this article point to the limited means of

handling escalated bullying conflicts and they underscore the importance of

preventive measures: to prevent bullying at all and to enable intervention in early

stages of conflict escalation. This is supported by the comparison of the duration

of bullying conflicts of successful and unsuccessful victims.

There are several limitations in this study. First, parts of the results are based

on mostly qualitative data. As in other studies that have exclusively dealt with

samples of bullying victims, it was impossible to draw a random sample.

Collecting samples with the help of bullying organizations may certainly lead to

a specific selection of victims. It can be assumed that escalated cases are

overrepresented. Moreover, members of associations of bullying are usually

more active in fighting for their case than victims who are not organized. In

addition, too small a number of successful victims was identified to draw firm

conclusions. On the other hand, the results converge with some previous results

of Keashly, Trott, and MacLean, (1994), Knorz and Zapf (1996), and Niedl

(1996). More research is needed to further support these findings of this study.

REFERENCES

Aquino, K. (2000). Structural and individual determinants of workplace victimization: The effects

of hierarchical status and conflict management style.

Journal of Management, 26, 171–193.

Begley, T.M. (1998). Coping strategies as predictors of employee distress and turnover after an

organizational consolidation: A longitudinal analysis.

Organizational Psychology, 71, 305–329.

Björkqvist, K. (1992). Trakassering förekommer bland anställda vid AA (Harassment exists among

employees at Abo Academy). Meddelanden fran Abo Akademi, 9, 14–17.

Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Hjelt-Bäck, M. (1994). Aggression among university employees.

Aggressive Behavior, 20, 173–184.

Blake, R.R., & Mouton, J.S. (1964). Managerial grid. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Cowie, H., Jennifer, D., Neto, C., Angula, J.C. Pereira, B., del Barrio, C., & Ananiadou, K. (2000).

Comparing the nature of workplace bullying in two European countries:

Portugal and the UK. In M. Sheehan, S. Ramsey, & J. Patrick (Eds.), Transcending the

boundaries: Integrating people, processes and systems. Proceedings of the 2000 conference

(pp. 128–133). Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, September.

de Dreu, C.K.W. (1997). Productive conflict: The importance of conflict management and conflict

issue. In C.K.W. de Dreu & E. Van de Vliert (Eds.), Using conflict in organizations (pp. 9–22).

London: Sage Publications.

de Dreu, C.K.W., & Van de Vliert, E. (Eds.). (1997). Using conflict in organizations. London: Sage

Publications.

den Ouden, M.D. (1999). Mobbing victims and health consequences. Paper presented at the Ninth

European Congress of Work and Organizational Psychology, Helsinki, Finland, May.

Einarsen, S. (1999). The nature and causes of bullying.

International Journal of Manpower, 20,

Einarsen, S. (2000). Harassment and bullying at work: A review of the Scandinavian approach.

Aggression and Violent Behavior: A Review Journal, 4, 371–401.

520

ZAPF AND GROSS

Einarsen, S., Raknes, B.I., Matthiesen, S.B., & Hellesøy, O.H. (1994). Mobbing og harde

personkonflikter. Helsefarlig samspill pa arbeidsplassen [Harassment and severe interpersonal

conflicts at work]. Soreidgrend: Sigma Forlag.

Einarsen, S., & Skogstad, A. (1996). Prevalence and risk groups of bullying and harrassment at

work.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 185–202.

Fisher, R.J., & Keashly, L. (1990). Third party consultation as a method of intergroup and

international conflict resolution. In R.J. Fisher (Ed.), The social psychology of intergroup and

international conflict resolution (pp. 211–238). New York: Springer Verlag.

Frese, M. (1989). Theoretical models of control and health. In S.L. Sauter, J.J. Hurrel, &

C.L. Cooper (Eds.), Job control and worker health (pp. 108–128). New York: Wiley.

Glasl, F. (1982). The process of conflict escalation and roles of third parties. In G.B.J. Bomers &

R. Peterson (Eds.), Conflict management and industrial relations (pp. 119–140). Boston:

Kluwer-Nijhoff.

Glasl, F. (1994). Konfliktmanagement. Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte und Berater [Conflict

management: A handbook for managers and consultants] (4th ed.). Bern, Switzerland: Haupt.

Groeblinghoff, D., & Becker, D. (1996). A case study on mobbing and the clinical treatment of

mobbing victims. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 277–294.

Hoel, H., Rayner, C., & Cooper, C.L. (1999). Workplace bullying. In C.L. Cooper & I.T.

Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 14,

pp. 195–230). Chichester: Wiley.

Kanner, A.D., Coyne, J.C., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R.S. (1981). Comparison of two modes of

stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events.

Kaucsek, G., & Simon, P. (1995). Psychoterror and risk-management in Hungary. Paper presented

as poster at the 7th European Congress of Work and Organizational Psychology, Györ,

Hungary, April.

Keashly, L., Hunter, S., & Harvey, S. (1997). Abusive interaction and role state stressors: The

relative impact on student residence assistant stress and work attitudes. Work and Stress, 11,

175–185.

Keashly, L., & Nowell, B.L. (in press). Conflict, conflict resolution and bullying. In

S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C.L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying in the workplace. London:

Taylor & Francis.

Keashly, L., Trott, V., & MacLean, L.M. (1994). Abusive behavior in the workplace: A

Violence and Victims, 9, 341–357.

Kirchler, E., & Lang, M. (1998). Mobbingerfahrungen: Subjektive Beschreibung und Bewertung

der Arbeitssituation [Bullying experiences: Subjective description and assessment of the work

situation]. Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 12, 352–262.

Knorz, C. (1994). Mobbing—eine Extremform von sozialem Streß am Arbeitsplatz [Mobbing—an

extreme form of social stressors at work]. Unpublished diploma thesis, Department of

Psychology, University of Giessen, Germany.

Knorz, C., & Zapf, D. (1996). Mobbing—eine extreme Form sozialer Stressoren am Arbeitsplatz

[Mobbing—an extreme form of social stressors at work]. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und

Organisationspsychologie, 40, 12–21.

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

Leymann, H. (1990). Handbok för användning av LIPT-formuläret för kartläggning av risker för

psykiskt vald [Manual of the LIPT questionnaire for assessing the risk of psychological

violence at work]. Stockholm: Violen.

Leymann, H. (1993). Mobbing—Psychoterror am Arbeitsplatz und wie man sich dagegen wehren

kann [Mobbing—psychoterror in the workplace and how one can defend oneself]. Reinbeck,

Germany: Rowohlt.

Leymann, H. (1996). The content and development of mobbing at work.

CONFLICT ESCALATION AND BULLYING

521

Leymann, H., & Gustafsson, A. (1996). Mobbing and the development of post-traumatic stress

disorders.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2),

Mackensen von Astfeld, S. (2000). Das Sick-Building-Syndrom unter besonderer

Berücksichtigung des Einflusses von Mobbing [The sick building syndrome with special

consideration of the effects of mobbing]. Hamburg, Germany: Verlag Dr. Kovac.

Martin, G.E., & Bergmann, T.J. (1996). The dynamics of behavioral response to conflict in the

workplace.

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69, 377–387.

Mikkelsen, E.G., & Einarsen, S. (1999). The role of victim personality in workplace bullying.

Unpublished manuscript, Psykologisk Institut, Risskov, Denmark.

Neuberger, O. (1999). Mobbing. Übel mitspielen in Organisationen [Bullying: Playing bad games

in organizations] (3rd ed.). München/Mering, Germany: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

Niedl, K. (1995). Mobbing/Bullying am Arbeitsplatz. Eine empirische Analyse zum Phänomen

sowie zu personalwirtschaftlich relevanten Effekten von systematischen Feindseligkeiten

[Mobbing/bullying at work: An empirical analysis of the phenomenon and of the

effects of systematic harassment on human resource management]. München, Germany:

Hampp.

Niedl, K. (1996). Mobbing and well-being: Economic and personnel development implications.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 239–249.

Rahim, M.A., & Magner, N.R. (1995). Confirmatory factor analysis of the styles of handling

interpersonal conflict: First-order factor model and its invariance across groups.

Applied Psychology, 80, 122–132.

Rayner, C. (1997). The incidence of workplace bullying.

Journal of Community and Applied

Social Psychology, 7, 199–208.

Rayner, C. (1999). From research to implementation: Finding leverage for prevention.

International Journal of Manpower, 20, 28–38.

Schönpflug, W. (1983). Coping efficiency and situational demands. In R. Hockey (Ed.), Stress and

fatigue in human performance (pp. 299–330). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Semmer, N.K. (1996). Individual differences, work stress, and health. In M.J. Schabracq,

J.A. Winnubst, & C.L. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of work and health psychology (pp. 51–86).

Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Sheehan, M., Barker, M., & Rayner, C. (1999). Applying strategies for dealing with workplace

bullying.

International Journal of Manpower, 20, 50–56.

Thomas, K.W. (1992). Conflict and negotiation processes in organizations. In M.D. Dunnette &

L.M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 651–

718). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Tjosvold, D. (1991). The conflict positive organization. New York: Academic Press.

Vartia, M. (1996). The sources of bullying—psychological work environment and organizational

climate.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 203–214.

Volkema, R.J., & Bergmann, T.J. (1989). Interpersonal conflict at work: An analysis of behavioral

Von Holzen-Beusch, E., Zapf, D., & Schallberger, U. (in press). Warum Mobbingopfer ihre

Arbeitsstelle nicht wechseln [Why bullying victims don’t change their job]. Zeitschrift für

Personalforschung.

Weber, H. (1993). Dem Phlegma eine Chance! Argumente gegen das Persönlichkeitsideal des

problemzentriert Bewältigenden [Give phlegm a chance! Arguments against the personality

ideal of problem centred coping]. In L. Montada (Ed.), Bericht über den 38. Kongreß der

Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie in Trier (Vol. 2, pp. 770–778). Göttingen, Germany:

Hogrefe.

Withey, M., & Cooper, W. (1989). Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative

Science Quarterly, 34, 521–539.

522

ZAPF AND GROSS

Zapf, D. (1999a). Mobbing in Organisationen. Ein Überblick zum Stand der Forschung [Mobbing

in organizations. A state of the art research review]. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- & Organisations-

psychologie, 43, 1–25.

Zapf, D. (1999b). Organizational, work group related and personal causes of mobbing/bullying at

work.

International Journal of Manpower, 20, 70–85.

Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the relationship between mobbing factors, and job

content, the social work environment and health outcomes.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

[Życińska, Heszen] Resources, coping with stress, positive emotions and health Introduction

Coping with Vision Loss Understanding the Psychological, Social, and Spiritual Effects by Cheri Colb