Abstract

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

:

an evaluation of the links between souterrain ware

and Hebridean ceramics

I

AN

A

RMIT

*

Division of Archaeological, Geographical and Environmental Sciences,

University of Bradford, United Kingdom

[Accepted 30 May 2007. Published 9 May 2008.]

Although some limited consideration has been given to the possibility of links

between the early medieval ceramic traditions of the Western Isles and the souterrain

ware of north-east Ireland, these have tended to be framed in the context of sup-

posed Dalriadic cultural infl uence fl owing from Ireland to Scotland. A re-evaluation

of the possible relationships between these pottery styles suggests that souterrain

ware might instead be seen as part of a regional expansion of western Scottish pot-

tery styles in the seventh–eighth centuries

AD

. This raises the question of what social

processes might underlie the cross-regional patterning evident in what remains a

vernacular, rather than a high-status, technology.

Archaeological studies of cultural connections between Scotland and Ireland during

the fi rst millennium

AD

have been hampered by a number of perceptual and organi-

sational factors. Modern political boundaries have inevitably led to the emergence

of distinct archaeological traditions within Scotland and Ireland, while histories of

prospection, methodologies of recording, conventions in publication, and priorities

for excavation have also evolved differently. Curatorial and classifi catory systems

have similarly grown up quite separately on either side of the North Channel. While

understandable for a variety of reasons, this has tended to compartmentalise primary

archaeological research and prevent the perception of some interesting aspects of

cultural patterning which cut across modern political boundaries.

The few attempts to embrace material on both sides of the water in our period

have tended to be driven not by archaeological, but by historical or pseudo-historical

questions deriving from what are generally very partial documentary sources. For the

fi rst millennium

AD

the two great marker points are of course the supposed Dalriadic

migration from Ulster to Argyll around

AD

500, and the Viking movements south

and westwards through the Hebrides to south-west Scotland and Ireland from around

AD

800. It is the fi rst of these that is of concern to us most directly here. For present

purposes, the discussion will be restricted to the specifi cally archaeological aspects

of the debates surrounding Scottish Dál Riata.

Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy Vol. 108C, 1–18 © 2008 Royal Irish Academy

Introduction

*

Author’s e-mail: i.armit@qub.ac.uk

doi: 10.3318/PRIAC.2008.108.1

Ian Armit

2

The voice of all Antiquity pronounces Ireland to have been Scotia: to omit

a host of authorities, Adamnan’s Life of Columba and Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History ought to have been suffi cient to prevent a question being raised on

the subject.

Dr William Reeves quoted by Anderson 1881

Debates on the historical authenticity of the Dalriadic migrations have ebbed and

fl owed, but the archaeological side of the debate in particular has been dogged by

the problems associated with properly assimilating the archaeological material from

Antrim and Argyll. While recent attempts to downplay the likelihood of a signifi cant

migration have much to commend them, especially with regard to the detailed critique

of the available documentary material (Campbell 2001), the archaeological side of

the question has been more diffi cult to address. The divergent research traditions and

priorities of archaeologists in Atlantic Scotland and north-east Ireland have been such

that the archaeological material from the two areas is not easily synthesised. Argyll,

for example, has benefi ted from survey programmes carried out over many years and

published in admirable detail (R.C.A.H.M.S. 1971; 1975; 1980; 1984; 1988). Even if

its archaeology remains less well understood than in other parts of Atlantic Scotland

(partly because of the sheer density and variety of the settlement record), its settle-

ment patterns in the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

can at least be sketched in outline (e.g.

Armit 2004). In essence, these comprise landscapes of small stone-walled enclosed

settlements and crannogs interspersed with a smaller number of larger, nuclear forts,

which represent the residences of the upper echelons of Dalriadic society (Alcock

1987; Nieke 1990; Lane and Campbell 2000; Campbell 2001).

Given the centrality of the written sources in determining archaeological

research agendas for this area, it is unsurprising that such attempts as have been

made to investigate Scottish–Irish links in the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

have focussed

on the quest to identify Irish antecedents, or at least parallels, for this distinctive (and

presumably Dalriadic) settlement pattern. It is probably fair to say that archaeologists

working in Scotland have taken the lead in these matters; not unexpectedly given the

iconic quality of the Dalriadic settlement in the wider history of the Scottish nation

(since the dynasts of Dál Riata eventually became the fi rst successful monarchs of a

nation approximating to the geography of modern Scotland). By contrast, the archae-

ological identifi cation of Irish Dál Riata has been a peripheral question at best for

most Irish archaeologists.

Unlike Argyll, the key area within Ireland, the Antrim coast, has been poorly

served by archaeological survey of fi eld monuments, despite a long and impres-

sive tradition of artefact collection, particularly associated with the rich coastal fl int

sources. There has been no published survey to match the Royal Commission’s work

in Argyll, or indeed to match Jope’s (1966) Archaeological survey of County Down.

Nor has there been any real delineation in print of the specifi c character of late pre-

historic and early medieval settlement patterns. Perhaps as a result, archaeologists

seeking Irish Dál Riata have had to be content with a rather homogenised Irish settle-

ment pattern of ringforts and crannogs synthesised and analysed by writers for whom

the question of Dalriadic origins was of limited interest.

Dál Riata in

archaeology

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

3

Closer examination of the specifi c character of Irish Dál Riata, however,

reveals some possible parallels for nuclear forts in north-east Ireland (e.g. Doonmore

near Fair Head; Anon 1988, 6) as well as a range of coastal enclosures with morpho-

logical similarities to their counterparts in Argyll (including the traditional capital of

Irish Dál Riata at Dunseverick). Irish Dál Riata also contains an unusually low dens-

ity of ringforts which, in any case, seem to date well after the traditional period of

the Dalriadic migration (Stout 1997). Nonetheless, despite some promising avenues

for further research, the parallels remain generalised and less than compelling.

Campbell (2001) has convincingly highlighted the problems with the conventional

picture of Fergus Mór’s cross-channel migration, yet we must give weight nonethe-

less to the more general theme of cultural contacts between north-east Ireland and

Scotland at this time. The tale of Fergus may be an origin-myth conjured up to serve

the interests of one particular band of aspirant dynasts, but to carry any force it must

surely have refl ected some perceived reality, some experience or social memory of

contacts and movements of individuals, families and war-bands across the North

Channel. The archaeological evidence for such contacts runs deep, from at least the

Neolithic (e.g. Cooney 2000) to the early centuries

AD

(Warner 1983), a matter of a

few generations before our mythical(?) Fergus.

It is inevitable, particularly in a period when literacy was a new and socially

restricted phenomenon, that written records will refl ect the interests, motives and

preoccupations of the social group who commission and/or produce them. In the

period in question that group was comprised of clerics and dynasts (particularly the

more enduringly successful ones). Thus we have a plethora of saints’ lives, kings’

lists and brief records of historical events (mainly battles and sieges) signifi cant in

the world-view of that particular subset of the early medieval population. Yet the

worlds portrayed in these fragmentary accounts should not be equated with the ‘real’

worlds of the time. To take one example, do terms like Dál Riata refl ect genuine

ethnonyms that would have been applicable to, and understood by, the majority of

the people occupying Argyll in the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

? Or should we simply

understand them as referring to the dominant elite? If, as seems probable, the latter is

closer to the truth, then the ‘histories’ portrayed in the records associated with these

elites come to seem even more partial and skewed. There is no particular reason,

therefore, why the patternings observable in the material culture of the period should

bear any specifi c relationship to ‘historical’ interpretations extrapolated from these

records. As archaeologists, we would be foolish to turn our backs on the documen-

tary sources, but we also need to avoid privileging them as any more than insights

into the actions, self-identities and motivations of a limited (if infl uential) sector of

the population.

This really is the core of the problem. As archaeologists, should we not strive

to resist the magnetic charms of these historical episodes and investigate the very

real archaeological linkages between these near neighbours in their own right? Even

if Fergus did exist, and even if he and his followers did make the crossing and estab-

lish the Dalriadic dynasty in Argyll, his migration was part of a long-term process;

a process which has left a good deal of archaeological evidence if we choose to look

Archaeology and

early histories

Ian Armit

4

for it. This evidence ranges beyond even the most generous reconstruction of historic

Dál Riata, both chronologically and geographically.

What is required, in the author’s view, is a stricter archaeological approach

to the period, focusing on the observable patterning of material culture across parts

of the region over the long term, and avoiding any specifi c focus on ‘events’ attested

by the fragmentary documentary sources. Even a superfi cial analysis of the material

culture of the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

suggests parallels between western Scotland

and north-eastern Ireland. Most obviously, both share in the distribution of certain

types of high-status metalwork, ranging from doorknob spearbutts in the fourth–fi fth

centuries

AD

(Heald 2001) through to a range of brooch and pin types in subsequent

centuries. The example we will examine here, however, is one which refl ects material

culture at a ‘vernacular’ level as distinct from the high-status exchange of decorated

metalwork: indigenous hand-made ceramics. This paper endeavours to show that the

study of such material has been inhibited both by the organisational divide which

separates Scottish and Irish archaeology, and, perhaps more importantly, by a mis-

placed reliance on the documentary sources. The specifi c case of Dál Riata will be

returned to later.

Although I was following the coastline, I seemed to be making little progress,

for, however far I travelled, the Mull of Kintyre was still visible on the right

hand side ... It was some time before I worked out that what I had been

looking at was County Antrim. Ireland had been omitted from the atlas.

(Bradley 2003, 222)

For most of Scotland and Ireland the early medieval period is effectively aceramic.

The exceptions to this general observation, however, are the north-east of Ireland and

the Hebrides. In Ireland, the appearance of a geographically restricted ceramic trad-

ition at this time seems rather surprising, since Ireland had apparently been aceramic

throughout the preceding Iron Age (Raftery 1995). In Scotland, however, the Hebri-

dean pottery tradition of the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

represents simply the continu-

ation of a long-established tradition of ceramic usage that stretches back through the

Iron Age and earlier (indeed a seemingly unbroken tradition of ceramic production

can be traced back to the Early Neolithic in the Western Isles).

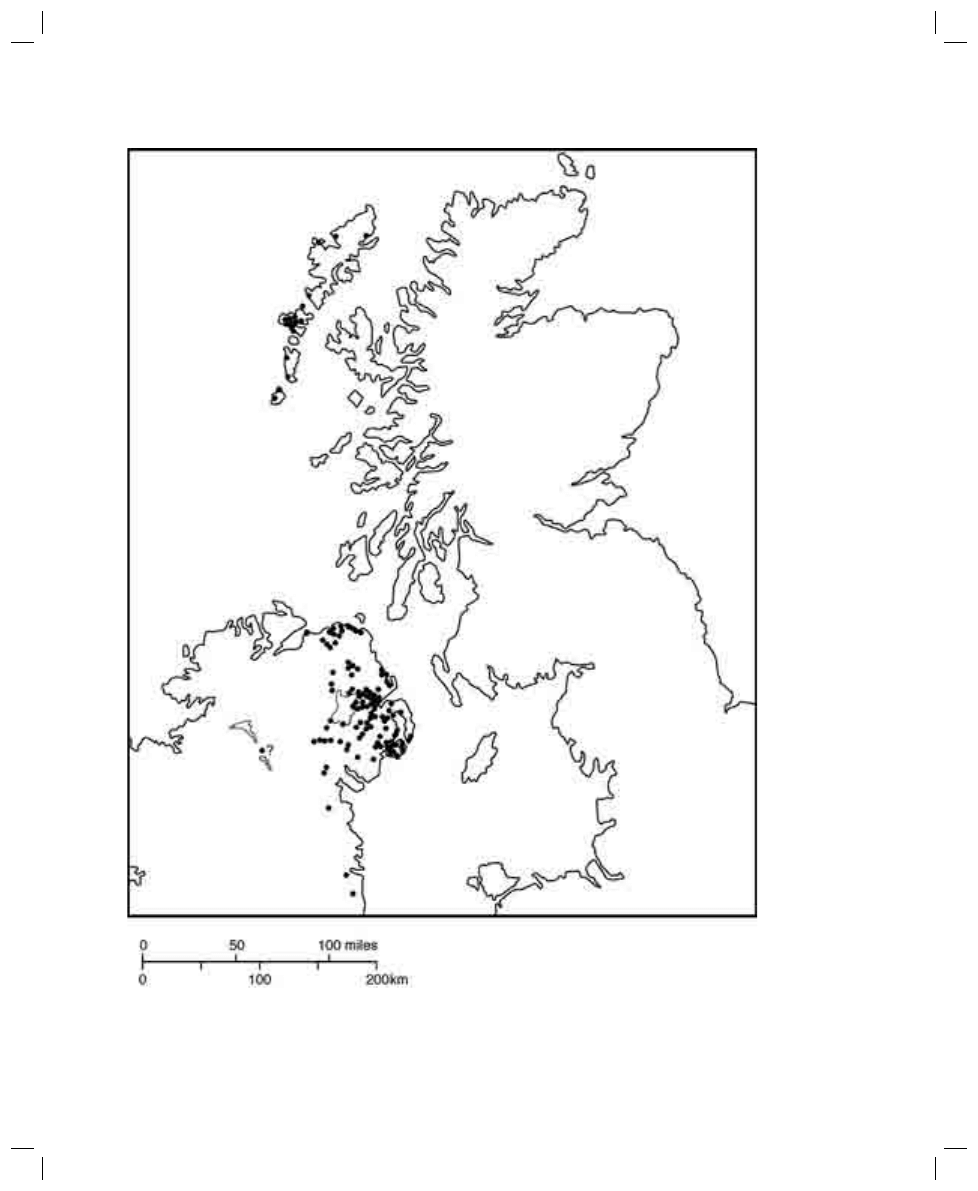

A glance at an initial distribution map showing these two pottery traditions

(Fig. 1), each an island in its own aceramic desert, suggests the possibility of some

form of cultural link between the two. Yet, despite some previous consideration of

possible relationships between these traditions, this appears to be the fi rst time that

the two distributions have been mapped together, and there has been no systematic

comparative study of ceramics across the region as a whole. Indeed, such limited

discussion as there has been on the possibility of cultural links in pottery production

have focussed almost exclusively on the role of pottery as an indicator of Dalriadic

colonial infl uence (e.g. Young 1966, 54). As is so often the case, archaeological

research has been led by questions drawn from documentary sources; sources which,

in this instance, seem particularly inappropriate.

Early medieval

pottery in Ireland

and Scotland

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

5

F

IG

. 1—Unmodifi ed distributions of Hebridean ‘Plain Style’ pottery and souterrain ware; after Lane 1990, ill. 7.7 and

Edwards 1990 respectively.

Ian Armit

6

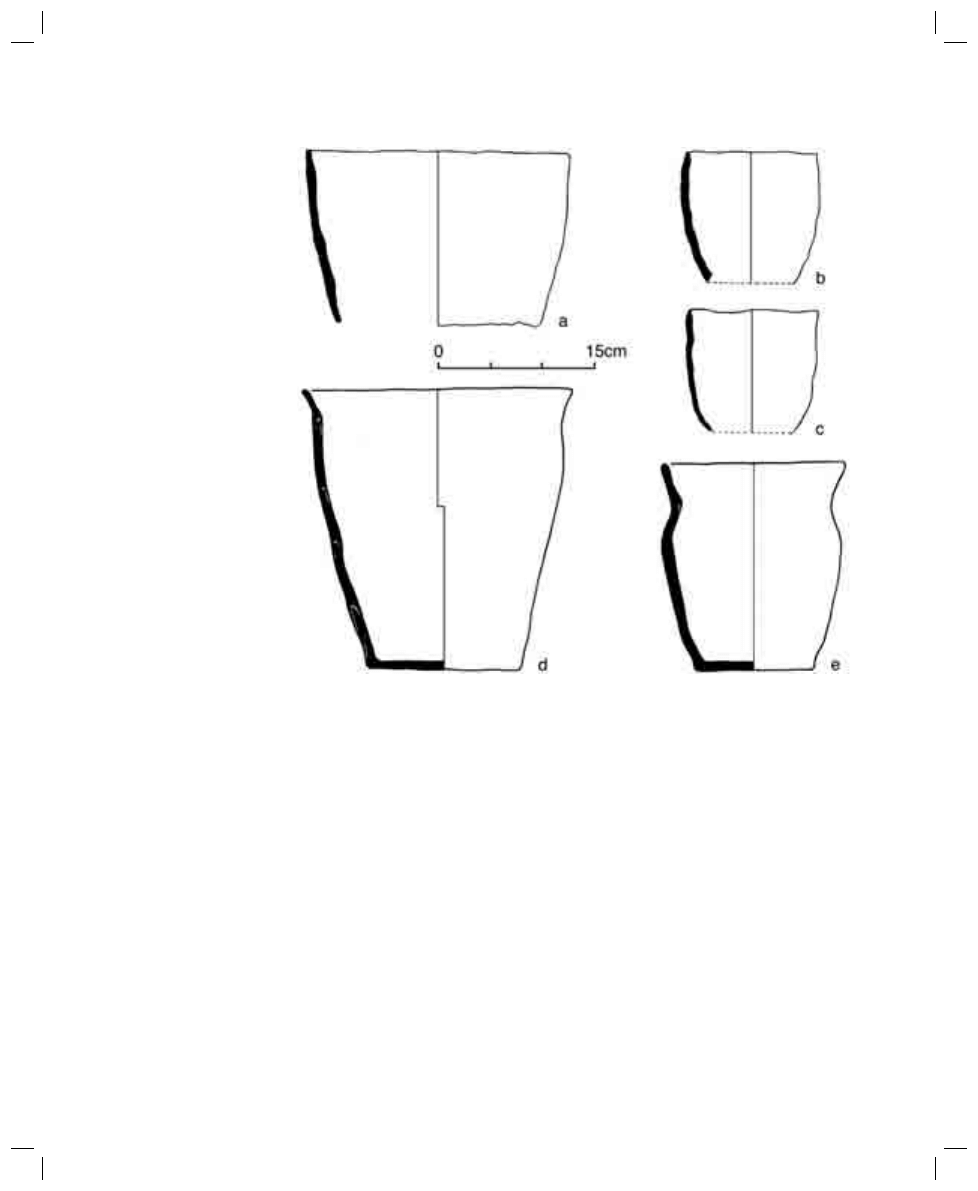

Pottery in Ireland

The early medieval period in the north-east of Ireland sees the emergence of locally

produced hand-made ceramics known collectively as souterrain ware (Fig. 2, Ryan

1973). Although there are clear variations within souterrain ware (e.g. Lane 1983

349–58) it has nonetheless usually been discussed as a single style, and insuffi cient

analysis of specifi c assemblages has been achieved to facilitate any meaningful sub-

division. The following observations thus treat souterrain ware, heuristically, as a

homogenous ceramic tradition:

1. Souterrain ware has no particularly close link with souterrains. The pot-

tery is found on sites of all early medieval settlement types and was clear-

ly employed by at least some of those individuals inhabiting high status

sites such as crannogs, ecclesiastical establishments and even the possible

‘nuclear’ fort of Doonmore (Childe 1938; McMullen 2000).

F

IG

. 2—Souterrain ware: a. Dundrum Sandhills, b. Lough Faughaun, c. Moylarg crannog,

d. Ballymacash, e. Lissue (a–d after Edwards 1990, 72, fi g. 28; e after Bersu 1948, 52, fi g. 12).

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

7

2. The quality of the pottery is variable, but much if not all of it seems to

have been fi red on simple open hearths (McMullen 2000, 5–6), presumably

in a domestic context. The impression is of a well-established regional

tradition carried out by non-specialists as was the case with prehistoric

pottery in the Western Isles.

3. Souterrain ware is overwhelmingly restricted in its distribution to the

north-east of Ireland, mostly to counties Antrim and Down (although

the dominance of these over adjacent counties may be exaggerated by the

distribution of archaeological excavations within Ulster). Despite a few

outliers further south along the east coast, the population of the rest of

early Christian Ireland was seemingly content to remain aceramic, pre-

sumably using vessels of metal, wood or other perishable materials to

fulfi l the roles in cooking, serving and food storage, which souterrain

ware provided in the north-east.

4. There is considerable variation within the region in terms of forms, fabrics

and the predominance of various decorative motifs (see Edwards 1990,

73 for a summary), but most usually the pots appear to have been ‘fl at-

bottomed with straight, nearly vertical sides’ (Mallory and McNeill 1991,

217). The perceived unity of the style may derive in part from its position

as one small ‘ceramic island’ in a much larger aceramic island. Any inter-

nal variation, in other words, is negligible when compared with the more

deep-rooted distinction between the ceramic and aceramic regions. When

examined in detail, however, it is clear that there is in fact signifi cant vari-

ation in form and style, with fl aring rims being documented, for example,

from Ballintoy (Evans 1945).

5. The occurrence of ‘grass-marking’ on the basal portions of many sou-

terrain ware vessels has played a central role in earlier discussions of

the possible links between the Irish and Scottish ceramic traditions (e.g.

Young 1966, 54). Grass-marked vessels seem to have been numerically

dominant in the souterrain ware tradition, although it is important to note

that their proportions and distribution within assemblages have not been

recorded systematically (Ivens 1984).

It has often seemed that grass-marking has been accorded a

cultural signifi cance, marking these Irish pots as somehow intrinsically

different from contemporary non-grass-marked vessels in the Hebrides.

As has been shown experimentally, however, grass-marking results sim-

ply from the use of chopped grass to prevent the vessel adhering to its

base plate during manufacture (Ivens 1984, contra Thomas 1968). The

Hebridean ceramic tradition was to a large extent practised in loca-

tions on or close to the extensive machair coastlines, with their unlim-

ited quantities of clean pure shell sand (Armit 1996), which could have

served the same purpose as chopped grass. Indeed, sand was probably

also used in Ireland, as many souterrain ware vessels show no evidence

of grass-marking. It would be interesting to see if grass-marking occurs

preferentially on sites distant from ready sources of sand, but no such

study has yet been carried out.

Ian Armit

8

Grass-marking is by no means exclusive to souterrain ware.

Examples can be found on Cornish pottery of the mid-fi rst millennium

AD

(Preston-Jones and Rose 1986), and variations on the theme are also evident

much earlier in the Hebridean Iron Age, notably at Eilean Olabhat, North

Uist, where grass mat impressions are prominent on the bases of vessels

dating to around the fourth century

BC

(Armit et al. forthcoming), as well

as during the Norse period. One clear line of enquiry for future research

on souterrain ware is the degree to which the occurrence of grass-marking

varies both chronologically and geographically. In any case, it seems on

present evidence that the initial occurrence of grass-marking in Ireland

need be no more than a simple refl ection of functional expediency in the

production process, with no implications for cultural origins or infl uences.

6. There appears to have been a development from an initial plain style

towards increasing decoration principally in the form of applied cordons

(Ryan 1973, 628–9), the classic case being the ringfort of Lissue (Bersu

1947). These applied cordons are remarkably similar to those which dom-

inate Hebridean assemblages in the early–mid-fi rst millennium

AD

(see

below) but this need not occasion any particular excitement since similar

motifs can be found in widely different times and places, and are probably

skeuomorphs mimicking the stitching on leather bags, as well as fulfi lling

a functional role as aids for lifting.

7. Despite this outline of relative chronology, the absolute chronological

range of souterrain ware is poorly understood. Ryan, using a range of

material associations (which he acknowledged as being unsatisfactory),

proposed a range from the sixth–seventh century

AD

to the twelfth cen-

tury or later (Ryan 1973, 626). Later writers have been more cautious

regarding the proposed start dates and have tended to place the origins of

souterrain ware in the seventh–eighth centuries (Edwards 1990, 74) with

the eighth century more generally favoured (Mallory and McNeill 1991,

201). Although, in some cases, souterrain ware has been recovered from

the same sites as E-Ware (Ryan 1973, 626) which now seems to have

been traded primarily in the fi rst half of the seventh century (Campbell

cited in Lane 1994, 107), the two types have yet to be found in the same

contexts. Where stratigraphic information is available, souterrain ware

seems to have been deposited later than E-Ware (e.g. Lynn 1986). It is

highly probable that souterrain ware was in use by the

AD

780s, as a sherd

from a mill in Drumard Townland appears to pre-date the emplacement of

timbers felled in

AD

782 (Baillie 1986), while the decorated assemblages

most likely appeared during the ninth century at the earliest (Mallory

and McNeill 1991). A radiocarbon date (UB-2002 1380+65 bp) from the

pre-Rath B levels at Dunsilly, Co. Antrim, which contained undecorated

souterrain ware (McNeill 1992), calibrates to

AD

530–780 at 2 sigma,

suggesting that souterrain ware was present at the site during the eighth

century, if not earlier. On balance, it seems most likely that souterrain

ware fi rst appears in the period from the mid-seventh to the mid-eighth

centuries

AD

, between approximately

AD

650–780.

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

9

In general, explanations for the origins of souterrain ware have tended to

focus within Ireland itself and have adopted a culture-historical approach. In par-

ticular it has been suggested that the distribution of souterrain ware may refl ect the

‘political and other distinctiveness of the kingdom of the Ulaid’ (Ryan 1973, 631–2),

a cultural distinctiveness which may even be refl ected in the earlier concentration of

La Tène metalwork in the north-east. It is unclear, however, why ‘dietary and culinary

practice’ (Ryan 1973) should be different under the Ulaid than elsewhere in Ireland.

Cultural connections with areas outside Ireland have also been invoked at

various times. The possible contribution of Cornish pottery traditions will not be

pursued here (see Ryan 1973, 629); instead, we will focus on the suggestion of a

Hebridean connection. First, however, we must examine the present state of under-

standing of the western Scottish pottery sequence.

The pottery sequence in western Scotland

While Iron Age pottery usage in most of Scotland was minimal, a strong and highly

developed ceramic tradition was maintained in the north and west, centring on the

Western Isles. This pottery was locally produced and hand-made, exhibiting a wide

range of vessel and rim forms, and a high degree of decoration. Although at its

most profuse and elaborate in the Western Isles, similar pottery was made in Orkney,

Shetland and the north Scottish mainland.

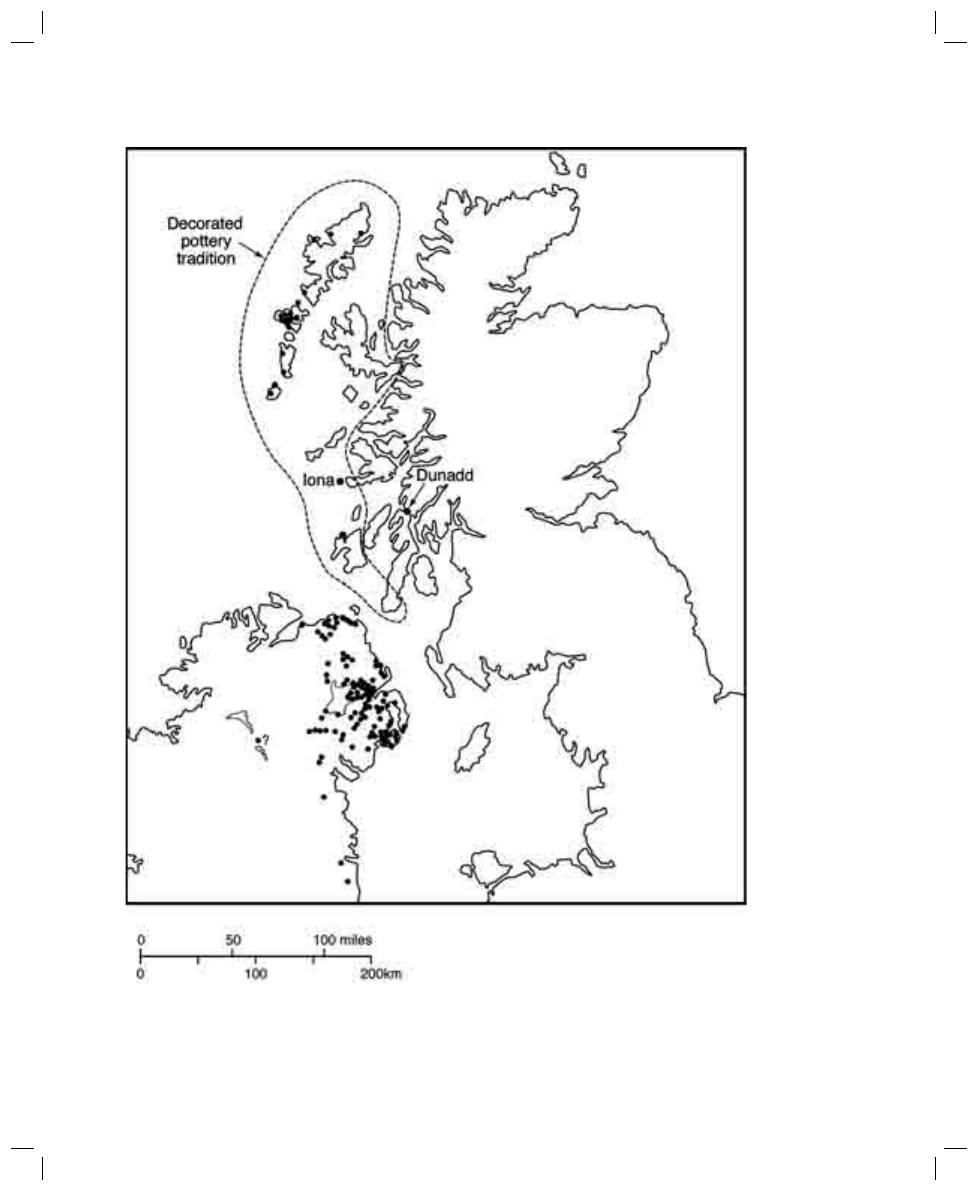

The southern extent of this pottery style during the Middle Iron Age is

relevant to the subsequent development of ceramics in the region. Lane has delineated

a zone of distribution encompassing the Western Isles and Skye but extending no

further south than Coll and Tiree (Fig. 1). This, however, is simply the zone with the

greatest density of sites and the largest assemblages. Lane also notes limited occur-

rences of this pottery style on Islay, Oronsay, Iona (at Dun Cul Bhuirg; Ritchie and

Lane 1980) and even at Dun Kildalloig close to the southern tip of Kintyre (Lane

1990, 123–6). The revised distribution zone indicated here (Fig. 3) takes account of

these additional sites.

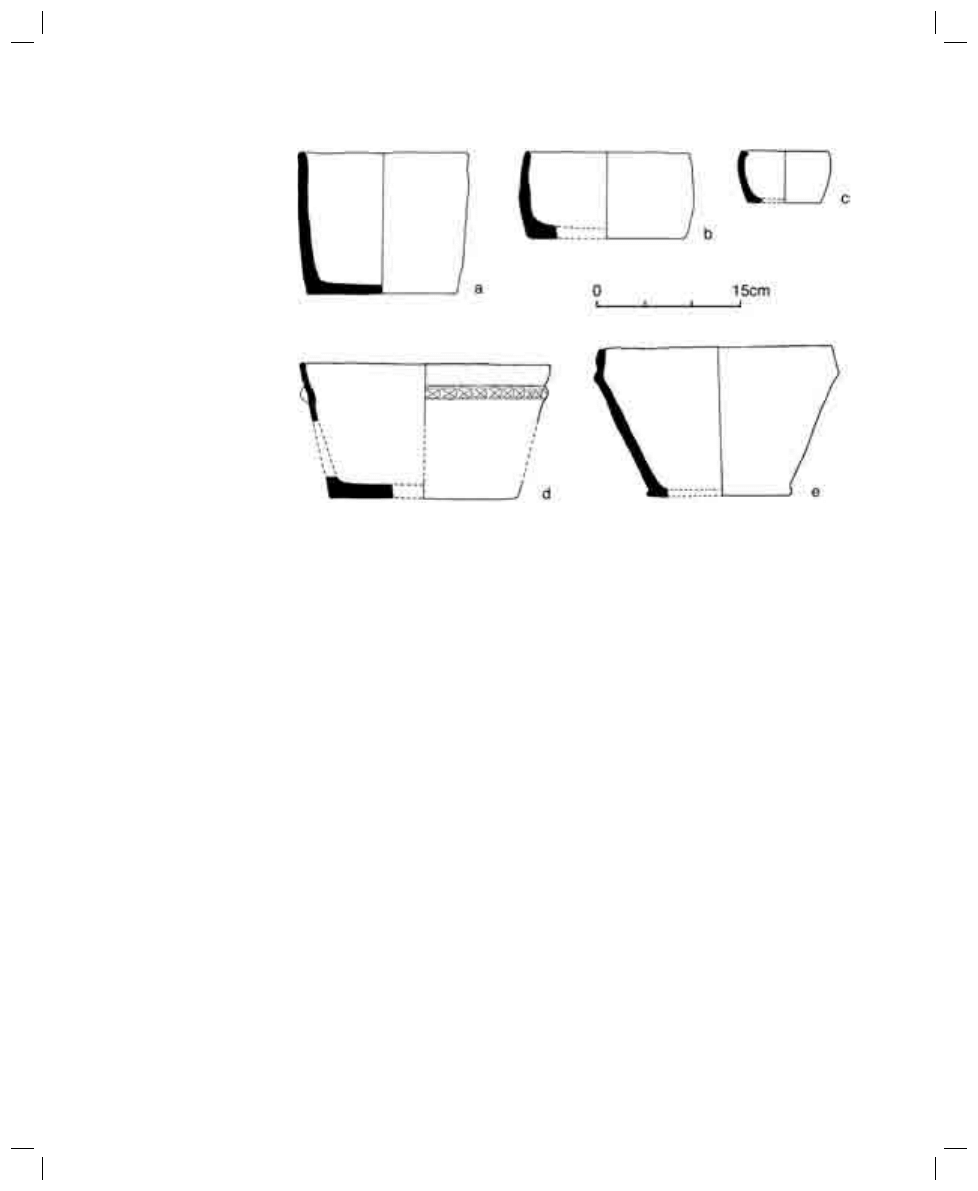

During the fi rst

millennium

AD

ceramic production continued but with a

marked reduction in the variety of form and decoration, the latter becoming limited

to occasional applied cordons (Fig. 4, Armit 1992, 144). Nonetheless, Hebridean

sites of this period, e.g. Eilean Olabhat (Armit et al. forthcoming) and Loch na

Beirgh (Harding and Gilmour 2000), continue to yield substantial assemblages. By

the eighth century, Hebridean pottery was more or less devoid of decoration and

forms had become restricted to simple bucket shapes with straight sides or fl aring

rims; Alan Lane’s ‘Hebridean Plain Style’ (Lane 1990). Lane drew attention to the

problems in establishing a chronology for this pottery style, which was until recently

reliant on the problematic dating evidence from the Udal in North Uist (Lane 1990,

122–3). This had seemed to suggest a start date for the pottery as early as the fourth

or fi fth centuries

AD

. More recently, however, excavated assemblages from Loch na

Beirgh (Harding and Gilmour 2000) and the pre-Plain Style assemblage from Eilean

Olabhat (Armit et al. forthcoming) have indicated that the Plain Style is most unlike-

ly to pre-date the seventh century

AD

.

Ian Armit

10

F

IG

. 3—Early medieval hand-made pottery in Scotland and Ireland, also indicating the main distribution of the Hebridean

Iron Age pottery tradition.

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

11

F

IG

. 4—Hebridean ‘Plain Style’ pottery: a–c. Dun Cuier, Barra (after Young 1955, 20, fi g. 7);

d–e. Udal, North Uist (after Lane 1990, 118, illus. 7.3).

The distribution of Plain Style pottery remained centred on the Western

Isles, although hand-made ceramics from Iona (Lane and Campbell in Haggarty

1988, 208–12; Hall in McCormick 1993, 89), Dunadd (Lane and Campbell 2000,

104) and Ardnave on Islay (Lane 1990, 127) suggest some use of ceramics further

south in Argyll. This ‘southern extension’ of the western Scottish material will be

discussed in greater detail below as it is of considerable importance in the study of

the interaction between Scotland and Ireland. A small quantity of hand-made ceram-

ics, including one sherd of possible souterrain ware, has also been recovered from

the excavations at Whithorn in the south-west of Scotland (Campbell 1997, 358).

Lane has also defi ned a distinct ‘Viking Age’ pottery assemblage in the

Western Isles initially identifi ed on the basis of his work at the Udal in North Uist

and subsequently recognised on numerous, often unstratifi ed sites, throughout the

islands (Lane 1983, 350–8). This pottery is characterised by ‘sagging and fl at-based

bowls, cups and fl at pottery discs or platters’ and, like souterrain ware, it is often

grass-marked (Lane 1990, 123). The appearance of grass-marking in the Western

Isles is especially striking, as it represents the conscious replacement of traditional

techniques with a minor technological innovation which brought no obvious prac-

tical benefi t.

Although Lane tentatively suggested a commencement in the ninth century

(1990, 122–3), the chronology of this ‘Viking Age’ pottery has become increasingly

problematic. The original dating was based on a single radiocarbon determination,

and some unpublished stratigraphic relationships to apparently Viking cultural mater-

ial, from the Udal in North Uist (Crawford n.d.). Recent excavations of a Norse

Ian Armit

12

house at Cille Pheadair in South Uist, however, have suggested late eleventh or

twelfth century associations for the platters which form the most distinctive elements

of this assemblage (Campbell 2002, 142). Excavations at Bornais Mound 3, also in

South Uist, have similarly shown an absence of platters in levels dated from the late

tenth and early eleventh centuries, and their fi rst appearance in levels dated from the

late thirteenth to late fourteenth centuries (Lane 2005, 194). This substantially later

dating may also be supported by the suggestion that these platters are skeuomorphs

of fl at disc baking stones found in Late Norse contexts in both Scandinavia and the

Northern Isles (Campbell 2002, 142). All of this suggests that the transition from

Lane’s Plain Style to what now appears misleadingly labelled as ‘Viking-Age’ pot-

tery, may date anywhere between the ninth and twelfth centuries, with the balance

of probability suggesting a post-1000

AD

start date. While the appearance of grass-

marking may yet refl ect a movement of ceramic technology from Ireland to Scotland,

it cannot be taken as a proxy Dalriadic colonial expansion. Instead, this particular

phase of interaction appears to occur in a Late Norse context.

The seemingly unlikely appearance of early medieval pottery production in the very

area of Ireland closest to the ‘reservoir’ of ceramic production that is the Western

Isles clearly demands investigation. Possible connections between these Irish and

Scottish pottery traditions have been suggested by scholars on both sides of the

North Channel at various times over the past century. Estyn Evans (1945), for exam-

ple, suggested some rather generalised parallels between pottery from Ballintoy in

Co. Antrim and the Hebridean assemblages as early as 1945, while Proudfoot (1958,

27–8) made similar observations with regard to the souterrain ware assemblage from

the ringfort ditch at Ballyaghagan.

In Scotland, the fi rst signifi cant work was by Alison Young, drawing on her

extensive experience of excavation in the Western Isles. Young (1955, 310–11) sug-

gested, for example, that sherds of what would now be identifi ed as Hebridean Plain

Ware, from the latest pre-Norse occupation at Dun Cuier in Barra and A’ Cheardach

Bheag in South Uist (Young and Richardson 1959), might be derived from ‘Northern

Irish’ pottery via contacts with Dalriadan settlement of Argyll. Young’s suggested

links, most fully developed in her 1966 paper on the overall development of Hebridean

pottery styles (Young 1966, 54), centred on the perceived similarity of forms (nota-

bly fl aring and inturned rims) and certain fabric types between elements of the Dun

Cuier assemblage and Irish sites like Drumnakill (Evans 1945) and the promon-

tory fort at Larriban (Childe 1938). The fl aring rim forms identifi ed by Evans at the

former site (e.g. 1945, 27 fi g. 7) certainly appear similar to those of Hebridean Plain

Style vessels, although they are unstratifi ed and may (on the basis of decoration on

some) be fairly late in the souterrain ware sequence. Ryan examined the Dun Cuier

sherds as part of his study of souterrain ware but was non-committal on the possibil-

ity of a connection, citing the undiagnostic nature of the fabrics (1973, note 78).

It is interesting that, in Young’s view, the cultural infl uences driving the

development of these pottery styles were exclusively from Ireland to Scotland; the

vector of transmission being a hypothetical extension of the supposed historically

attested Dalriadic migration. Given the lengthy pedigree of pottery production in the

Scottish–Irish

connections

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

13

Western Isles and the complete absence of any corresponding ceramic background in

Ireland, one might have expected that any infl uences would have fl owed in precisely

the opposite direction. That this possibility seems not to have been considered gives

some indication of the power of the ‘Dalriadic paradigm’ and highlights the tendency

for archaeological evidence to be downplayed in favour of documentary evidence,

no matter how limited the latter might be. The same assumption of one-way cultural

traffi c underlies Lane’s suggestion that pre-existing Hebridean pottery traditions

were ‘eventually infl uenced by the introduction of Souterrain Ware styles at Iona’

(1990, 127). More recent work and the general ‘tightening up’ of the chronology of

the western Scottish sequence, however, allows for a new picture to be developed.

The rich settlement landscapes of Argyll have been subject to much less excavation

than those of the Western Isles, and this is particularly problematic when it comes to

understanding the material culture of the Iron Age and early medieval periods. None-

theless, there has been some excavation in recent times. Much of this has focussed

on sites associated with the historical presence of Dál Riata; particularly Dunadd, the

traditional capital of Scottish Dál Riata, and Iona, the monastic settlement associated

with Columba and his successors. Both sites have yielded indigenous hand-made

pottery, albeit in relatively small quantities compared to the settlement sites of the

Western Isles.

Excavations at Iona by various excavators over a number of years have yield-

ed several small assemblages of hand-made pottery. Lane and Campbell’s (1988) dis-

cussion of this material indicates that, although dating is imprecise, both locally made

and possibly also Irish-made pottery was in use within the monastic community in

the period from the seventh to ninth centuries

AD

, and certainly prior to

AD

1000. This

equates to Reece’s ‘middle monastic phase’ (1981, 104), although the very earliest

phases of the monastery may have been aceramic (Barber 1981, 364). Among this

material are several sherds exhibiting the grass-marking associated with souterrain

ware, and grass-marked bases have come from at least three separate programmes of

excavation on the island (Barber 1981; Reece 1981; Haggarty 1988). The radiocar-

bon dates and general cultural context of the material strongly suggest a pre-Norse

date for this pottery (especially Reece 1981). This places the Iona material within

the same chronological bracket as Lane’s Hebridean Plain Style, although fabric,

form and the presence of likely imports tie the Iona material more closely to Ireland

than to the Western Isles. Slightly more recent excavations, however, have produced

further hand-made sherds including some from grass-tempered (as opposed to grass-

marked) vessels which Hall has explicitly linked to pre-Norse and Norse pottery

traditions of northern and western Scotland (Hall in McCormick 1993, 89).

Limited as it is, the pottery assemblage from Iona seems profuse when

compared with that from Dunadd. The excavations at Dunadd have produced only

two small sherds of hand-made pottery of likely early medieval date (seventh to

ninth centuries

AD

), and these are entirely unproven to be of that period (Lane and

Campbell 2000, 104). Nonetheless, their occurrence confi rms the presence of ceram-

ics in the area during the period when Dalriadic power was at its height, i.e. during

the currency of the Hebridean Plain Style.

Back to Dál Riata

Ian Armit

14

Standing back from the detail, and ignoring for one moment the ‘historical’ Dalriadic

population movements, what patterns are discernible from this ceramic data? What

we appear to have, during the mid-seventh–eighth centuries

AD

, is a regional expan-

sion of ceramic production. From an initial focus on the Western Isles and western

seaboard of Scotland during the Middle Iron Age, ceramic production extends to

encompass much of north-east Ireland. Ceramic production continued in both areas

for several centuries thereafter with some evidence of regionality, most notably the

extensive occurrence of grass-marking in Ireland. From around

AD

1000 or later, the

occurrence of grass-marking seems to have spread northwards, becoming common-

place across the whole region from the Western Isles (in Lane’s ‘Viking-Age’ style)

to Ulster. In other words, pottery production seems to have spread from Scotland

to Ireland some time around the mid-seventh–eighth centuries

AD

, followed by the

movement, several centuries later, in the eleventh or twelfth centuries

AD

, of a spe-

cifi c technological convention (the use of chopped grass as a basal treatment) back

from Ireland and southern Argyll to Scotland (the technique also appears some time

around the eighth century

AD

in Cornwall, suggesting either independent develop-

ment or some other current of infl uence). The seemingly spontaneous appearance of

grass-marking in Irish souterrain ware need occasion no particular surprise once we

abandon the idea that it represents some form of cultural marker.

The picture presented here is in marked contrast to former interpretations

which tended to see the Irish producers of souterrain ware as the prime movers,

introducing aspects of their ceramic technology to western Scotland as part of a

broader wave of Dalriadic cultural infl uence. We need then to consider the nature of

the social processes which underlie the patternings visible in the material culture.

What, in other words, does this pottery mean? The parallel developments in ceramics

in Ulster and western Scotland suggest that certain individuals or groups must have

moved within these regions during the mid-seventh–eighth centuries

AD

taking with

them knowledge of the techniques of hand-made pottery production and a range of

stylistic and technological traditions.

Who were these individuals? The evidence of the Western Isles pottery

sequence suggests that, by the middle of the fi rst millennium

AD

, pot-making had

become a low-status activity. Vessels were functionally effi cient but plain and sim-

ple. The elaborate visual language expressed through pottery decoration during the

Middle Iron Age had long since disappeared. If, as seems probable, pot-making was

primarily a female activity, then the decline in the centrality of ceramics within the

domestic sphere may refl ect a downgrading of women’s roles through the fi rst mil-

lennium

AD

. Alternatively, it has been suggested that from the end of the Middle Iron

Age there was a disintegration of traditional kinship bonds within the islands and the

establishment of hierarchies based increasingly on wealth and social position (Armit

2005). In this context we may see certain activities, such as pottery-making, being

increasingly associated with marginalised social groups. In either case, it appears

that by the second half of the fi rst millennium

AD

pottery production was a ubiquitous

but low-status activity in the Western Isles. It seems probable, therefore, that paral-

lelism in ceramics between north-east Ireland and the Hebrides refl ects the move-

ment of low status people; either as groups or individuals. This effectively means

that an entirely different set of social processes must be invoked in the interpretation

Discussion

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

15

of these ceramic patterns than we might commonly use to account for the spread

of high-status objects such as the decorative metalwork that has absorbed so much

scholarly attention in this period (e.g. Spearman and Higgitt 1993). As we shall see,

however, the aggrandisement of this bejewelled elite group may have been intimately

associated with the physical displacement of the dispossessed.

Although the detailed discussion was restricted to the issue of ceramic links, similar

arguments can be constructed using other aspects of material culture. For ex ample,

the same areas within which these pottery traditions are found also witness the

development of distinctive fi gure-of-eight house forms which, in both regions, give

way over time to a new tradition of rectilinear buildings (e.g. Lynn 1978, Armit

1996). What is now required is the more detailed analysis of the full range of cul-

tural phenomena available to archaeologists, at scales appropriate to the phenomena

under discussion, and freed from the presumptions of pseudo-historical narrative.

We do not yet understand the mechanisms by which these cultural traits developed

and spread. What is clear is that they did not operate as discrete ‘packages’ in the trad-

itional culture-historical mould. Nor can they easily be equated to any ethnic map

which we might hope to reconstruct from analysis of the documentary sources.

The parallel development of ceramics shows contacts between the Western

Isles and north-eastern Ireland perhaps initiated in the mid-seventh–eighth centuries

with continuation or renewal of those contacts in the Late Norse period. These links,

observable in the patterning of material culture, suggest the spread of cultural infl u-

ences at a ‘vernacular’ level, refl ecting contacts and directions of movement that are

far from obvious from the limited documentary sources. Indeed this would suggest

that the cultural infl uences detectable archaeologically are not a proxy for the move-

ment of a ‘people’ (which would be, in any case, a rather anachronistic concept for

this period) but rather refl ect a range of more complex social relationships relating

to the exploitation and displacement of low status and marginalised groups, and the

parallel emergence of a mobile aristocratic elite. One striking possibility is that low

status individuals were displaced from western Scotland to Ireland through slave-

raiding and trading, which were sponsored and mediated by elite groups such as the

Dalriadan aristocracy (Armit forthcoming).

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Society for American Archae-

ology’s sixty-ninth Annual Meeting in Montreal, 2004, supported by a British Acad-

emy Overseas Conference Grant.

Alcock, L. 1987 Economy, society and warfare among the Britons and Saxons.

Cardiff. University of Wales Press.

Anderson, J. 1881 Scotland in early Christian times. Edinburgh. David Douglas.

Anon 1988 Historic monuments in Antrim coast and glens: area of outstanding natural

beauty. Belfast. Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland.

Conclusion and

prospect

Acknowledgements

References

Ian Armit

16

Armit, I. 1992 The later prehistory of the Western Isles of Scotland. British Archae-

ological Reports (British Series) 221. Oxford. Tempus Reparatum.

Armit, I. 1996 The archaeology of Skye and the Western Isles. Edinburgh. Edin-

burgh University Press.

Armit, I. 2004 The Iron Age. In D. Omand (ed.), The Argyll book, 46–59. Edin-

burgh. Birlinn.

Armit, I. 2005 Land-holding and inheritance in the Atlantic Scottish Iron Age. In

V. Turner, R.A. Nicholson, S.J. Dockrill and J.M. Bond (eds), Tall stories: 2

millennia of brochs, 129–43. Lerwick. Shetland Amenity Trust.

Armit, I. forthcoming ‘Perishable wares’: Dál Riata, Merovingia and the early

medieval slave trade.

Armit, I., Campbell, E. and Dunwell, A.J. forthcoming Excavation of an Iron Age,

early historic and medieval settlement and metal-working site at Eilean

Olabhat, North Uist. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Baillie, M.G.L. 1986 A sherd of souterrain ware from a dated context. Ulster Jour-

nal of Archaeology 49, 106.

Barber, J.W. 1981 Excavations on Iona 1979. Proceedings of the Society of Anti-

quaries of Scotland 111, 282–380.

Bersu, G. 1947 The rath in townland Lissue. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 10,

30–58.

Bradley, R. 2003 Neolithic expectations. In I. Armit, E. Murphy, E. Nelis and D.D.A.

Simpson (eds), Neolithic settlement in Ireland and western Britain, 218–22.

Oxford. Oxbow.

Campbell, E. 1997 The hand-built dark age pottery. In P. Hill (ed.), Whithorn and

St Ninian: the excavation of a monastic town 1984–91, 358. Stroud. Sutton.

Campbell, E. 2001 Were the Scots Irish? Antiquity 75, 285–92.

Campbell, E. 2002 The Western Isles pottery sequence. In B. Ballin-Smith and I.

Banks (eds), In the shadow of the brochs, 139–44. London. Tempus.

Childe, V.G. 1938 Doonmore, a castle mound near Fair Head, County Antrim.

Ulster Journal of Archaeology 1, 122–35.

Cooney, G. 2000 Recognising regionality in the Irish Neolithic. In A. Desmond,

G. Johnson, M. McCarthy, J. Sheehan and E. Shee-Twohig (eds), New

agendas in Irish prehistory: papers in commemoration of Liz Anderson,

49–65. Wicklow. Wordwell.

Crawford, I.A. n.d. The West Highlands and islands; a view of 50 centuries. Cam-

bridge. Great Auk Press.

Edwards, N. 1990 The archaeology of early medieval Ireland. London. Routledge.

Evans, E.E. 1945 Field archaeology in the Ballycastle district. Ulster Journal of

Archaeology 8, 14–32.

Haggarty, A.M. 1988 Iona: some results from recent work. Proceedings of the

Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 118, 203–13.

Harding, D.W. and Gilmour, S.M.D. 2000 The Iron Age settlement at Beirgh, Riof,

Isle of Lewis, Volume 1, the structures and stratigraphy (Calanais Research

Series no. 1). Edinburgh. University of Edinburgh.

Heald, A. 2001 Knobbed spearbutts of the British and Irish Iron Age: new examples

and new thoughts. Antiquity 75, 689–96.

Irish–Scottish connections in the fi rst millennium

AD

17

Ivens, R. 1984 A note on grass-marked pottery. Journal of Irish Archaeology 2,

77–9.

Jope, E. (ed.) 1966 An archaeological survey of County Down. Belfast. H.M.S.O.

Lane, A. 1983 Dark-age and Viking-age pottery in the Hebrides, with special reference

to the Udal, North Uist. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London.

Lane, A. 1990 Hebridean pottery: problems of defi nition, chronology, presence and

absence. In I. Armit (ed.), Beyond the brochs, 108–30. Edinburgh. Edin-

burgh University Press.

Lane, A. 1994 Trade, gifts and cultural exchange in dark age western Scotland.

In B.E. Crawford (ed.), Scotland in dark age Europe, 103–15. St Andrews.

Committee for Dark Age Studies.

Lane, A. and Campbell, E. 2000 Dunadd: an early Dalriadic capital. Oxford.

Oxbow Books.

Lane, A. 2005 Pottery. In N. Sharples (ed.), A Norse farmstead in the Outer Hebri-

des: excavations at Mound 3, Bornais, South Uist, 194–5. Oxford. Oxbow.

Lane, A. and Campbell, E. 1988 The pottery. In A.M. Haggarty (ed.), Iona: some

results from recent work. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scot-

land 118, 203–13: 208–12.

Lynn, C. 1978 Early Christian period domestic structures: a change from round to

rectangular plans? Irish Archaeological Research Forum 5, 29–45.

Lynn, C. 1986 Excavations on a mound at Gransha, County Down, 1972 and 1982:

an interim statement. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 48, 81–90.

Mallory, J.P. and McNeill, T.E. 1991 The archaeology of Ulster. Belfast. Institute

of Irish Studies.

McCormick, F. 1993 Excavations at Iona, 1988. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 56,

78–107.

McMullen, S. 2000 A comparison between the souterrain ware and everted rim

ware of County Antrim, Northern Ireland. Unpublished BSc Dissertation,

Queen’s University Belfast.

McNeill, T.E. 1992 Excavations at Dunsilly, Co. Antrim. Ulster Journal of Archae-

ology 54–5, 78–112.

Nieke, M.R. 1990 Fortifi cations in Argyll: retrospect and future prospect. In I. Armit

(ed.), Beyond the brochs, 131–42. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

Preston-Jones, A. and Rose, P. 1986 Medieval Cornwall. Cornish Archaeology 25,

135–85.

Raftery, B. 1995 The conundrum of Irish Iron Age pottery. In B. Raftery, V. Megaw

and V. Rigby (eds), Sites and sights of the Iron Age: essays on fi eldwork

and museum research presented to Ian Matheson Stead, 149–56. Oxford.

Oxbow.

Reece, R. 1981 Excavations in Iona 1964–74. Institute of Archaeology, Occasional

Publication No. 5. London. Institute of Archaeology.

Ritchie, J.N.G. and Lane, A.M. 1980 Dun Cul Bhuirg, Iona, Argyll. Proceedings of

the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 110, 209–29.

Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland

(R.C.A.H.M.S.) 1971 Argyll. An inventory of the ancient monuments: 1.

Kintyre. Edinburgh. H.M.S.O.

Ian Armit

18

R.C.A.H.M.S. 1975 Argyll. An inventory of the ancient monuments: 2. Lorn. Edin-

burgh. H.M.S.O.

R.C.A.H.M.S. 1980 Argyll. An inventory of the ancient monuments: 3. Mull, Tiree,

Coll and northern Argyll. Edinburgh. H.M.S.O.

R.C.A.H.M.S. 1984 Argyll. An inventory of the ancient monuments: 5. Islay, Jura,

Colonsay and Oronsay. Edinburgh. H.M.S.O.

R.C.A.H.M.S. 1988 Argyll. An inventory of the ancient monuments: 6. Mid

Argyll and Cowal: prehistoric and Early Historic monuments. Edinburgh.

H.M.S.O.

Ryan, M. 1973 Native pottery in early historic Ireland. Proceedings of the Royal

Irish Academy 73C, 619–45.

Spearman, R.M. and Higgitt, J. (eds) 1993 The age of migrating ideas: early medi-

eval art in northern Britain and Ireland. Edinburgh. Sutton.

Stout, M. 1997 The Irish ringfort. Dublin. Four Courts Press.

Thomas, C. 1968 Grass-marked pottery in Cornwall. In J. Coles and D.D.A. Simp-

son (eds), Studies in ancient Europe, 310–31. Leicester. Leicester University

Press.

Warner, R.B. 1983 Ireland, Ulster and Scotland in the earlier Iron Age. In A.

O’Connor and D.V. Clarke (eds), From the Stone Age to the ’Forty-Five:

studies presented to R.B.K. Stevenson, 160–87. Edinburgh. John Donald.

Young, A. 1955 Excavations at Dun Cuier, Isle of Barra, Outer Hebrides. Proceed-

ings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 89, 290–328.

Young, A. 1966 The sequence of Hebridean pottery. In A.L.F. Rivet (ed.), The Iron

Age in northern Britain, 45–58. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

Young, A. and Richardson, K.M. 1959 A’ Cheardhach Mhor, Drimore, South Uist.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 93, 135–73.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Functional improvements desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplast

Functional improvements desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplast

Increased diversity of food in the first year of life may help protect against allergies (EUFIC)

05 Potential climate induced vegetation change in Siberia in the twenty first century

KasparovChess PDF Articles, Sergey Shipov In the New Champion's First Public Appearance, a Resolute

On the Connection of the Living and the?ad

Freedom in the United States Analysis of the First Amendme

Military men figured prominently in the leadership of the first English

Moonchild (Liber LXXXI The Butterfly Net) A Prologue by Aleister Crowley written in 1917 first pu

First Time In The Behind

Zelazny, Roger The First Chronicles of Amber 01 Nine Princes in Amber

Aurel Braun NATO Russia Relations in the Twenty First Century (2008)

Nature of bacterial colonization influences transcription of mucin genes in mice during the first we

H G Wells The First Men in the Moon

Galician and Irish in the European Context Attitudes towards Weak and Strong Minority Languages (B O

Shock waves in molecular solids ultrafast vibrational spectroscopy of the first nanosecond

Pamela R Frese, Margaret C Harrell Anthropology and the United States Military, Coming of Age in th

Thomas C Holt The Problem of Race in the Twenty first Century (2001)

PROGRESS IN ESTABLISHING A CONNECTION BETWEEN THE ELECTROMAGNETIC ZERO POINT FIELD AND INERTIA

więcej podobnych podstron