ETHNIC MINORITIES IN SPAIN:

TEACHER, PARENT, AND STUDENT BELIEFS AND EDUCATIONAL

PERFORMANCE IN MULTICULTURAL SCHOOLS

Dr. Pilar Arnaiz; Dr. Pedro P. Berruezo; Remedios de Haro; Dr. Rogelio Martínez

Faculty of Education

University of Murcia (Spain)

The debate on diversity and, in particular, the inescapable challenges accompanying it, gives much food for thought to schools at the

beginning of the twenty first century. As a consequence of the migration phenomenon undergone in Europe in recent decades, cultural

diversity has become one of the main focuses of attention. Integration of foreign students is insufficient in that minority cultural groups

who have previously been overlooked also need consideration. In the Spanish context, this particularly means gypsy people. A new

education context is arising with significant and difficult challenges that, in essence, demand development of intercultural contexts.

Appropriate teacher education is essential if teachers and schools are to be endowed with new abilities, strategies and knowledge in order to

improve their practice. Only this will enable them to offer an education response adapted to the diversity of their students.

The qualitative study we present was carried out in southeast Spain where 7.3% of the population is recent immigrants from Eastern

Europe, South America and North Africa. The study focuses on the primary education system ’s response to increasing diversity in the

student population. The study was conducted in 14 schools. Archival information (demographic data, student grades) and interviews were

conducted with a diverse sample that included 14 head teachers, 97 teachers, 75 students, and 22 families. Findings suggest that schools

embrace an assimilationist view of education and have little familiarity with multicultural education notions. Important differences are

observed in the educational outcomes of various groups; specifically, academic failure affects 30% of students from mainstream culture,

80% of Moroccan and 62% of gypsy students. The authors discuss the implications of findings in the context of the history and status

these groups have had in Spanish society and identify reforms required to accommodate the educational needs of an increasingly diverse

student population in this nation.

Key words:

Interculturality, immigration, ethnic minorities, gypsy, assimilation, exclusion, inclusion, school failure, ethnocentrism.

Introduction

We live in a multicultural society. The education sphere is directly affected by this phenomenon and is taking on new characteristics,

particularly the presence of increasingly heterogeneous school populations. This requires acceptance and recognition of their differences

(ethnicity, gender, culture, social class, exceptional abilities, handicaps or giftedness) from a level playing field. Schools must meet the

challenge of developing intercultural education.

Unfortunately education research is providing worrying data in this area. The assimilationist model drives education practice and conceptions

in many primary and secondary schools, thus denying differences and leading to the failure or exclusion of certain groups. As Meirieu (2004)

points out, the desire for homogeneity spoils schools, impoverishing them and preventing interaction or opportunities to test the

knowledge of students who think or learn differently.

Various studies carried out in Spain aimed at finding out, analysing and evaluating the incorporation of and educational response to cultural

diversity (Bartolomé, 1997; Fernández Enguita, 1996, 1999; General Secretariat of the Gypsy Foundation, 2002; Valero, 2002; García and

Moreno, 2002; Garreta, 2003; Report of the Defensor del Pueblo on Schooling of Immigrant Children, 2003; and that of García Llamas et al,

2004) have exposed the limited ability of education institutions to create a school of and for everyone.

This study presents a research project (Arnaiz, 2001) developed in the Autonomous Community of Murcia aiming to describe, analyse and

evaluate the level of gradual incorporation of children from other cultures and racial groups (North African and gypsy), as well as the nature

and type of education being offered to the diverse student population present in Primary and the first two years of Compulsory Secondary

Education in this Spanish Region. It was carried out in the academic years 1997/08, 1998/99 and 1999/00.

Specifically, this study presents part of the research devoted to finding out the evolution and tendencies resulting from the migration

phenomenon both in Spain and in this Region and the repercussions in the education sphere, such as the attitude of schools and teachers

to these students and the benefits and drawbacks in curriculum development caused by their cultural differences. Once these aspects have

been explored, we go on to look at the academic performance of the different groups under study. Likewise, we examine the thoughts of

parents and children from both the minority and majority cultures on the relationships established between peers.

1. Establishing the research focus

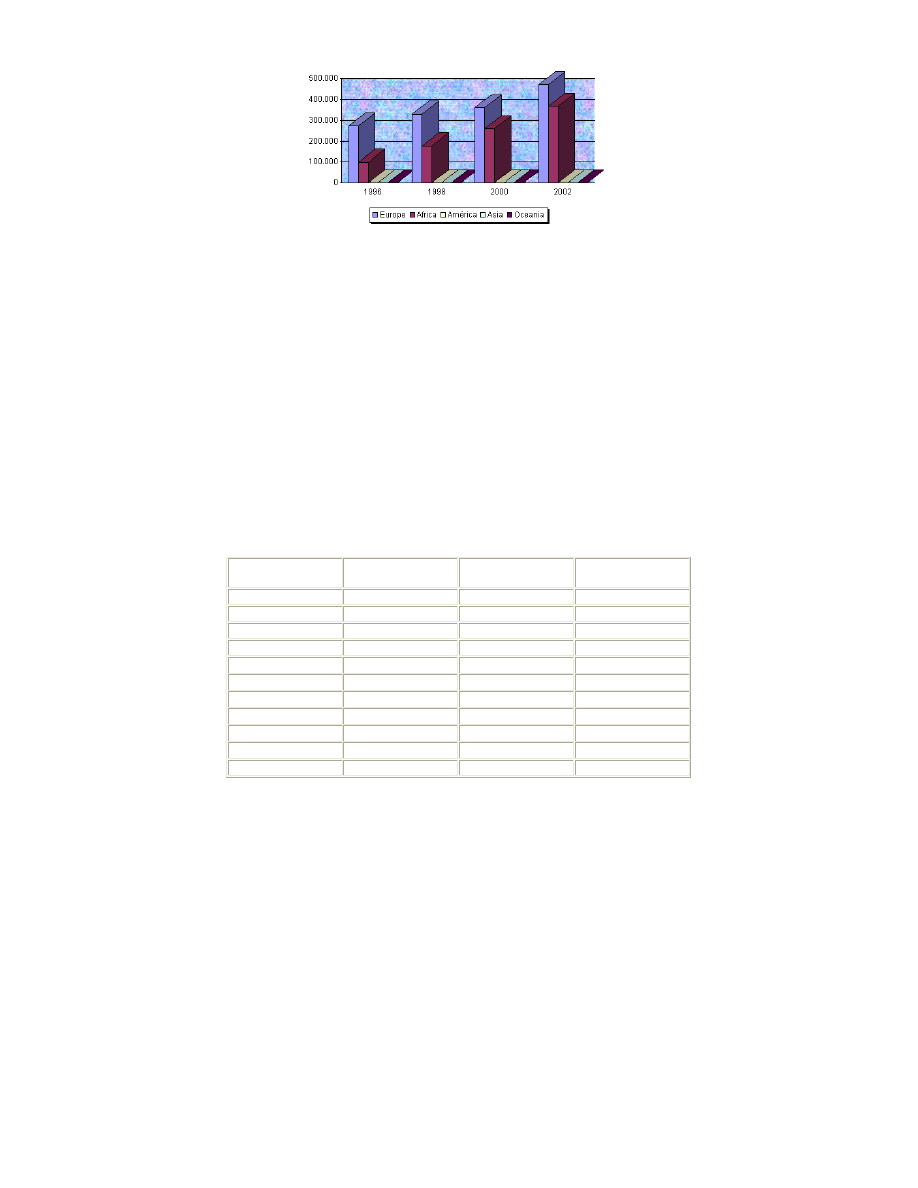

Since the 80s, Spain has undergone a slow but inexorable increase in foreign residents, as can be seen from the following data. In 1990

there were 407,647 foreign residents; in 1996 538,984 were registered; and in 2002 the country had 1,324,001 registered foreign

residents to whom must be added the number of undocumented immigrants. That the number is gradually growing and constant is evident.

The period from 19972002 should be highlighted, in that its analysis is the key to understanding the characteristics of current immigration

in Spain. During this period, the total number of foreigners doubled, but it is not only the numbers that are of significance, but also the

principal protagonists of this acceleration. The following diagram gives the figures and origin:

Figure 1. Evolution by continent or origin of foreign residents, 19962002. Source: Annual Statistics of Foreigners 2002 (2003). Madrid:

Ministry of Interior

According to the latest figures supplied by the Ministry of the Interior (Home Office), on December 31, 2003, 1,647.011 foreigners were

registered in Spain originating from Europe (34.1%), America (32.2%), Africa (26.21%), Asia (7.2%) and Oceania (0.06). By province, the

greatest concentrations are found in Madrid, Barcelona, Alicante, Malaga, Murcia and the Balearic Islands. The Murcia Region is the fifth

autonomous community in number of foreign residents, with Africans making up 47.43% of the total and South Americans 34.65%.

The change undergone over recent decades because of the migration phenomenon is reflected in schools. The same tendency of constant

and numerically significant increase in foreign residents in the second half of the 90s commented upon above is reflected in the education

sphere. In the academic year 1999/00 annual increments of over 30%, 40% and almost 50% occurred. In just nine years we have moved

from the figure of 50, 076 foreign students in 1993/94 to that of 398, 187 in 2003/04

The autonomous communities with the highest number of foreign pupils are Madrid, Catalunya, Valencian Community, Andalusia, Canary

Islands and Murcia. Among these, the significance of the Murcian figures can be discerned if we note that Murcia is in fourth position in the

number of North African students in schooling.

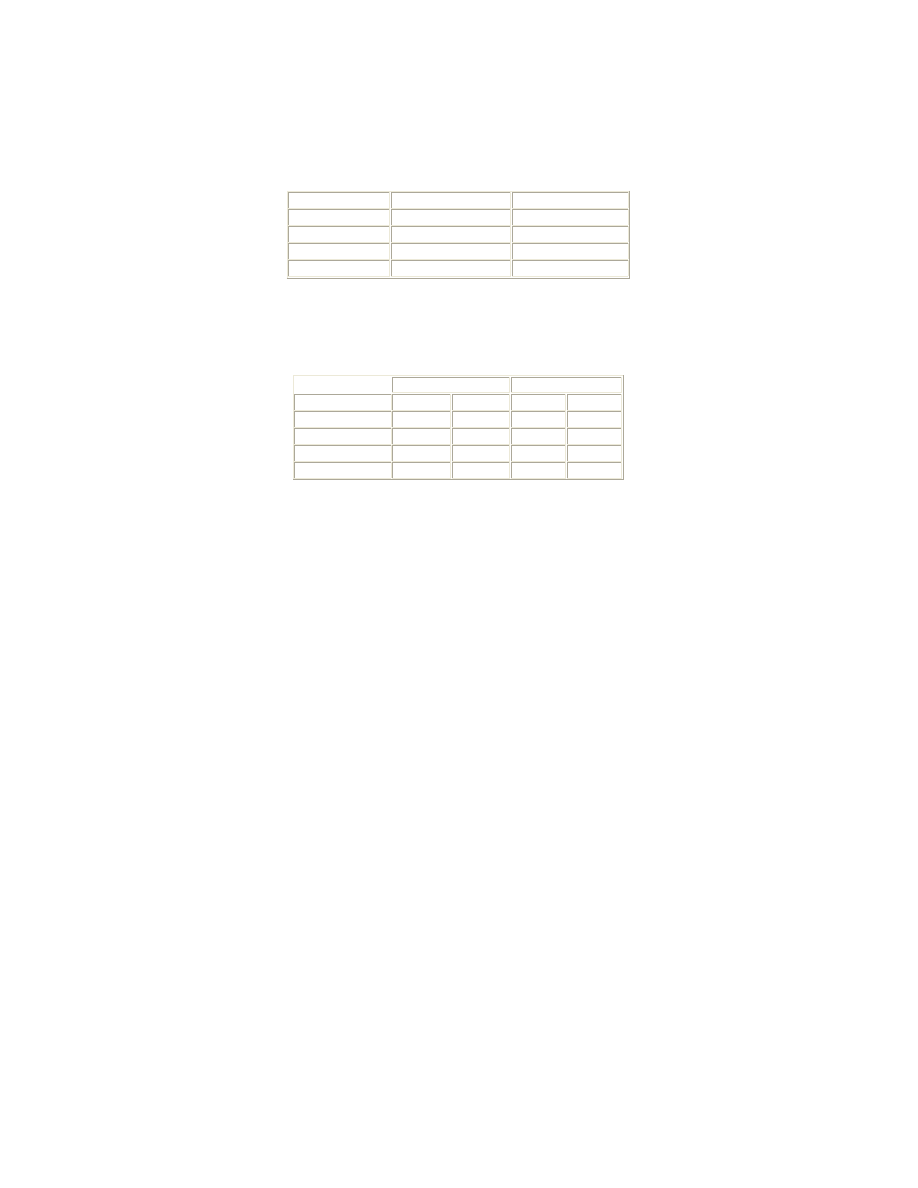

The number of foreign students in the Region of Murcia has been in steady increase since 1994/95, with a noticeable rise as from 1997/98

when an increase of 42.8% on the previous year’s figures can be seen. From then until now, the growth rate has been over fifty per cent. If

in the academic year 2000/01 there were 4,481 foreign students in schooling, in just three years the figure has risen to 18,592 in 2003/04.

The table below shows the changes and rise in foreign student numbers in Murcia Region.

Table 1. Change in foreign student numbers in Murcia Region

Source: Education Statistics in Spain 200304. Advanced Data (2004). Madrid: Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport.

In this context, combined with the presence of gypsy population, our research project was set in motion (Arnaiz et al, 2001) and ran over

the academic years 1997/98, 1998/99, 1999/2000. There were two fundamental objectives: to establish the true situation and determine

proposals for improvement based upon analysis and evaluation of data obtained in pursuit of the former.

The objectives proposed for the present study are:

l

To find out the attitude of teachers and schools towards these pupils, benefits and drawbacks perceived and the reflection of cultural

differences in the curriculum offered.

l

To analyse and evaluate the academic attainment of the different groups under study.

l

To understand the ideas of parents and pupils from both minority and majority cultures on the peer relationships established.

2. Empirical Study

2.1. Population and sample

The population under study came from all the state primary schools of the Region of Murcia taking students from other cultures (in the

academic year 1997/98 these groups comprised 3,369 gypsy and 1176 North Africans in the Region). The criteria applied to make up the

sample were as follows:

l

Municipalities where the greatest numbers of North African immigrants and gypsy population were to be found.

l

Schools’ years of experience in dealing with students from cultural minority groups:

n

Schools new to dealing with students from other cultures

n

Schools with an average experience (34 years) in attending to these students.

n

Schools with a lot of experience in dealing with students from ethnic minorities.

The research sample was taken from fourteen primary schools in Murcia Region, a total of 1,584 students, from the first years of Primary

Education (68 years) until the first two years of Compulsory Secondary Education (1214 years). Pupil distribution was as follows:

Table 2. Distribution of sample by cultural group

Re the sample distribution by gender, it is worth highlighting that the number of North African boys in schooling is 78 %, whereas the

number of girls in compulsory schooling is less than a quarter, specifically 21.69 %. This contrasts with the percentages for the remaining

intake which near 50 % for male and female. The student distribution from the selected sample is as follows:

Table 3. Distribution of sample by gender

2.1. Data collection techniques

The most important technique, because of the weight given it in this study, is that of semi structured interview with the management teams

(14), teachers (97), parents and pupils from the majority culture (14 and 42 respectively) and minority (8 and 33 respectively) from the

schools under study. Information on different areas was collected according to the group interviewed. Below we set out and analyse the

information obtained.

l

School management teams and teachers: reaction to the presence of students from minority cultures in the school and classrooms,

perceived benefits and drawbacks, needs and curricular proposal on offer.

l

Students: Respect for students as much from the majority as from the minority cultures, the relationships between them, whether of

acceptance or rejection, experiences and feelings of these students as a result of living in a multicultural space.

l

Parents: What were the feelings of parents from both cultures about the relationships established between their children as well as the

hopes and expectations of parents from minority groups.

From the study of academic attainment, the evaluation reports of different courses where the sample population was to be found were

used. The evaluation report at the end of each two year cycle is an official document wherein appears information on the students over a

cycle (two academic years), specific measures taken for each pupil requiring this (support teaching and/or curricular adaptation), marks

attained in each area of the curriculum and the decision on promotion to the next level. Documents used were as follows:

l

Final Evaluation Report from the First Cycle of Primary Education (68 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the Second Cycle of Primary Education (810 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the Third Cycle of Primary Education (1012 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the First Cycle of Compulsory Secondary Education (1214 years)

2.3. Data analysis techniques

The research has adopted a qualitative and quantitative methodology according to the nature of the study. The model of Miles and

Huberman (1984) for the collection, summary and presentation of data and the extraction of conclusionsproofs were taken as reference for

interview analysis. The computer programme for qualitative analysis NUDIST (QSR, 1994) has helped with this task. The group devised a

calculus measure for the statistical analysis of the evaluation reports.

3. Results and discussion

We continue with the presentation of results obtained from the collection and information analysis techniques applied.

3.1. Interviews

The presentation of results begins with reactions expressed by schools and teachers to the presence of ethnic minority pupils. It is worth

mentioning that the majority of management teams interviewed saw the situation as perfectly normal. 71% said that the presence of these

pupils caused no problem in the centre, but rather they were seen as equal to other students, irrespective of their culture or country of

origin. Part of these, 21%, expressed their initial worries and doubts re this new situation in that they did not know how to behave or relate

to these students. 8% pointed out the considerable difficulties occasioned by the high numbers of ethnic minorities joining the school each

year, coupled with language deficiencies and ratio increases.

As with the management teams, the majority of the teachers reacted to the incorporation of students from different cultures with normality

and acceptance (55%). We were often surprised by expressions such as seeing these students as “just like the others”, with nothing to

distinguish them from their classmates. Yet the cultural, linguistic and social differences and all that this can contribute to school life are

patent. Alongside this attitude of normality, other teachers (28%) believed that the presence of these pupils created a series of difficulties,

problems for the classroom and school, such as interfering with the pace of the class, creating disruption and conflict, problems of

adaptation and integration, lack of contact between families and the school, unfamiliarity with the language in the case of North African

students and a long list of drawbacks, as will be seen below. 15% of teachers expressed unease and uncertainty. The main reason for this

reaction was unfamiliarity with the language and not knowing how to deal with these students. Finally, 12% of the remaining teachers

believed that the presence of these students represented a professional challenge.

Within this majority position of normality, the only advantage to the incorporation of students from different ethnic minorities, indicated, in

unequal measure by management (78.57%) and teachers (15%) was that of cultural enrichment, the opportunity to find out about another

culture. Among the teachers, this view was put forward by those who had gypsy students in their classes. They believed the enrichment

was twosided (majority and minority cultures) in that knowledge of other cultures was deepened, as can be seen from the following

quotations:

“The main advantage is the enrichment all students derive, because they become more open minded. Whenever possible, benefit is taken

from this.”

(Management Team Centre 11)

“It is a source of enrichment for everyone as long as other cultures are studied and we take advantage of these students’ presence. The

other students can learn their language, their customs and culture. This is very gratifying as it brings us closer.”.

(Teachers Centre 11)

In contrast to this single advantage found by the majority of school management teams and a minority of teachers, we can find a long list

of disadvantages and/or drawbacks to these pupils’ presence, pointed out by both and that, oddly enough are always laid at the pupil’s

door. Hence we would like to point out that these students’ presence in schools has supposed, in the words of Enguita (1999, 135, 136),

“… little short of a torpedo to the flotation line of the school ship, however much they are accepted and assumed” and, therefore, “to

claim that there is nothing new under the sun is a way of sidestepping the issue and, in fact, is what a good number of teachers do”.

Re schools with North African students, the main drawback encountered is that of unfamiliarity with the language and for those with gypsy

students that of absenteeism. In the case of the former, the language is perceived as the main handicap to the teachinglearning process or

even the normal pace of the class, combined with adaptation problems in that, according to teachers, these inhibit relationships based on

equality.

In the case of gypsy children, it would seem that absenteeism is seen as the main disadvantage deriving from their presence in schools with

this ethnic minority. Irregular attendance causes disturbance to the normal class rhythm in that the pupils fall out of step with the class

level. A greater effort from the teachers is also required in that extra work has to be prepared for these pupils. Absenteeism is a more acute

problem among gypsy students and does not significantly affect the North African pupils, but they are held back by other factors such as

late commencement of schooling which frequently causes learning difficulties. Both groups are affected by drop out from schooling as from

the age of 13/14, especially girls.

“The problem is communication. When the students speak the language, there is no problem.”

(Teachers Centre 4)

“It can be frustrating when you have done your best and there are children who continue to be absent or leave because they are

itinerant.”

(Management team– Centre 8)

Another drawback found in five of the schools was that of rejection among students, both inside and outside the classroom. Specifically, in

three of these schools there have been outbreaks of racism and xenophobia, especially between gypsy and North African pupils. The

management teams told us that these students have serious behaviour problems between themselves and with the rest of the school

population. This situation has created a certain tension in peer group relationships, with a marked tendency for students from the same

racial group to stay together, both in school time and beyond.

“There have been few disadvantages, but there have been situations of tension and rejection among students”.

(Management team– Centre 5)

Similarly, teachers talk of confrontation and rejection, saying that relationships between students of different cultures are good within the

classroom, but at break times and out of school times they are more problematic or non existent. Thus in the playground it can be seen

that pupils form groups with those from their own culture.

Another difficulty as perceived by management teams and teachers is that of lack of school books and equipment, particularly among gypsy

pupils. They also refer to behaviour problems, especially the difficulty some North Africans and/or gypsies have with complying with school

rules and behaving well in class. Four schools also mentioned problems due to a lack of hygiene in pupils from certain ethnic minorities,

claiming that these pupils come to school dirty and smell, so provoking rejection by their classmates.

“Of the gypsies, they complain of their lack of hygiene, their smell, rather than their ethnicity. There are children who smell very

bad, of urine, faeces or sweat, so that no one can go near them…”.

(Management Team– Centre 13)

Only in three centres do problems connected with health and food appears. These refer to an unbalanced diet. Those interviewed claimed

that the gypsies tend to eat badly: they do not pay attention to the healthgiving properties of food, they eat an excess of industrialised

cakes and sweet foods and have no fixed meal times. In the case of North African students, it was found that their economic situation

affected their nutrition and they could not always eat several times a day, sometimes only eating at school lunch times.

Along with this list of drawbacks, seven of the school management teams mentioned the lack of material, economic and human resources to

answer the pupils’ needs in that the education authorities did not send them in accord with students’ arrival.

“We do not have enough material or human resources, only the good will of the teachers, which is, of course, very important”.

(Management team– Centre 4)

The same proportion of schools mentioned the considerable difficulties caused when North African students joined the school and began

their studies because they bought no documentation of their previous schooling.

Other disadvantages mentioned by the teaching body referred to: increased workload, lack of human resources, poor coordination among

the teachers and lack of training. Teachers highlight the extra work that this type of student causes, given that they need a lot of time and

attention. Also stressed is the need to prepare material especially for the North Africans because of language limitations.

“Teachers have to do three times the amount of planning: for those who are achieving the normal curriculum goals, for those

who fall short because of handicaps and require support and for those who exceed who also need a different type of work”.

(Teachers – Centre 10)

Teachers recognise their lack of training to deal with the cultural diversity of the schools. They also point out that sometimes there is no co

ordination between colleagues and a lack of human resources to support these students.

“If I had specific training, it would not matter to me if the child were North African or Russian. The problem is what I do with hi

m ”.

(Teachers– Centre 2)

Faced with all these drawbacks to the presence of students from ethnic minorities, management teams and teachers totally agree about

their needs, putting human resources in first place and material resources in second as the solution to the problem. The prime objective

identified by schools and teachers is the integration of these students, an integration they understand as adoption of the values, customs

and culture of the majority group. Thus it can be seen that while at a theoretical level there is hope of acceptance, of responding to the

demands of cultural diversity, at a practical level difficulties and problems arise in its execution because of an absence of an intercultural

project. Therefore, once the objectives of integration and language learning have been attained, teachers move on to work on the curricular

objectives according to pupils’ stage of schooling without adapting them in any way. Thus, the process becomes that of mere assimilation

of ethnic minority pupils.

“Like the rest of the staff, within my classroom I teach everyone. My subject is the same for all my students, the reality is that

they are the same as everyone else. Normally I make no distinctions among my students and neither do they, so differences disappear ”.

(Teachers – Centre 10)

Intercultural education is relegated to the celebration of peace day or other specific events, so that it takes on a marginalised, deficient and

anecdotal character in that it does not run through the whole teachinglearning process. In short, the majority of teachers admit to not

doing any kind of multicultural activity, excusing themselves because they do not know the culture, do not have time or it is difficult to

integrate it into the curriculum plans. Dealing with diversity is therefore not present in a school life that only sees the majority cultural

viewpoint.

In the light of this situation, gypsy and North African families stress the importance of the school. However, many express their discontent

with the fact that there is an absence of their cultural traits in the curriculum, affirming that their children are forced into the cultural and

school model of the majority culture. The desire expressed by all the families interviewed is for recognition of equality within difference, that

the school should become a space open to interculturalism. The protagonists’ words sum this up:

“When the school has different groups of students, I would recommend that an important point to deal with is that of inter

culturalism, with the aim of not excluding any culture and not imposing the majority culture. This enriches not only the minorities, but

everyone.”

(Cultural minority parents– Centre 3)

If the beliefs of the parents and pupils of the majority and minority cultures on peer relationships are borne in mind, it can be seen that

interculturalism remains very distant. Half of parents from the minority culture interviewed confirm the rejection suffered by their children.

If we look to parents from the majority culture, in spite of their perception of a climate of acceptance in the schools, they point out a series

of negative aspects, among which rejection, for various motives, stands out. In some contexts, language limitations cause situations of

rejection or non acceptance because of misunderstandings between students. Most of the parents from the majority culture, who were

interviewed, with the exception of those from one centre, claimed that these students had problems adapting to the education system.

Among the reasons given behaviour problems and their refusal to associate with other classmates should be mentioned.

“There are North African students who do not want to integrate, nor their parents. However, until they integrate there cannot be equality

of education”.

(Majority culture parents– Centre 4)

Re rejection, students from the majority culture as much as those from the minority culture openly admit to the scarcity of contacts

between each group and even occasions of rejection.

“Each goes their own way…Often, outside school, you see them in the street and say hello, but nothing more”.

(Majority culture students– Centre 4)

“I don’t talk to them, don’t trust them and they are not my friends”.

(Minority culture students– Centre 4)

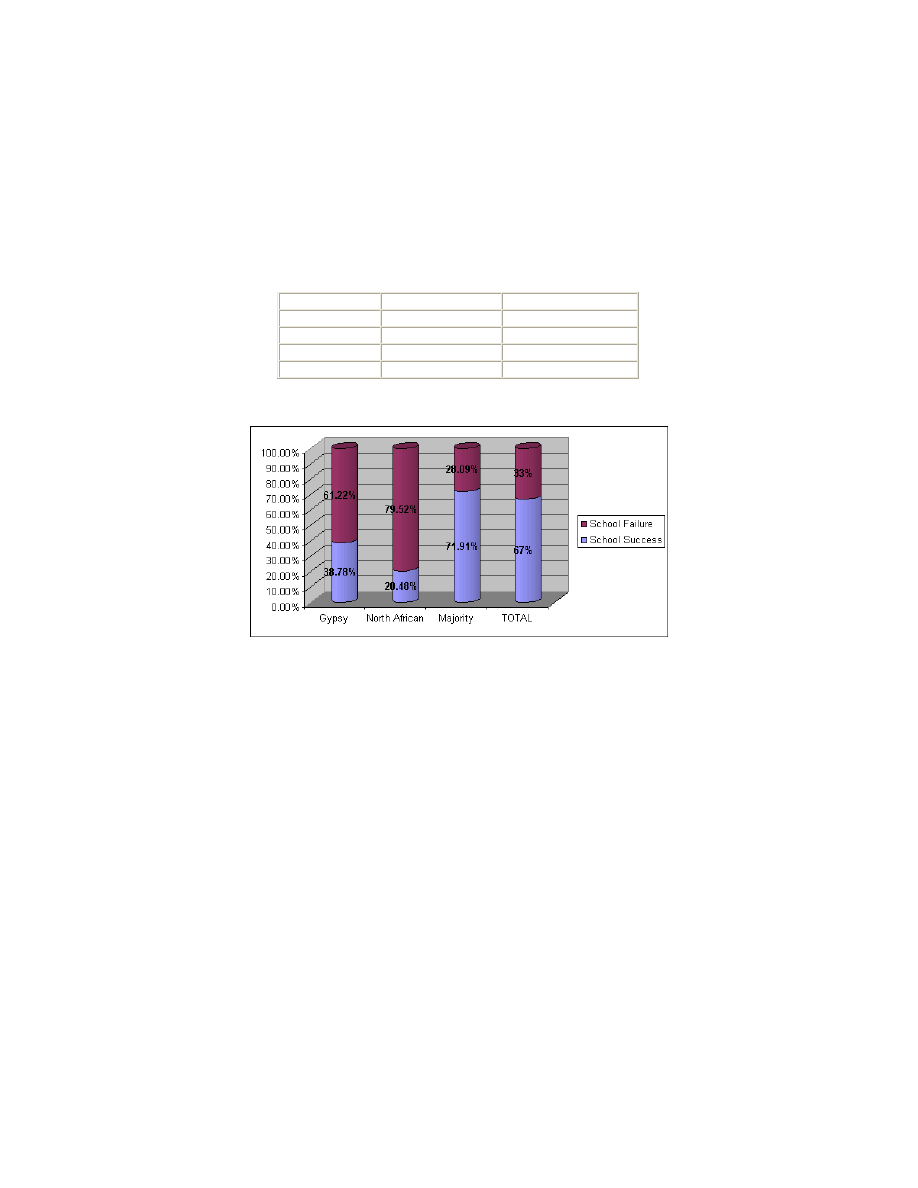

3.2. Academic Attainment

We will now look at the success and failure rate of pupils from the groups under study. Analysis of the academic results of pupils studying

in the schools from the sample indicates that the average of those who successfully pass the level in which they are registered is 67 % as

opposed to 33 % who fail. These failure rates can be influenced, among other factors, by the variable of “cultural origin” in that the

percentage of students from the majority culture who pass the level is 71.91 %, compared to the remainder (North African and gypsy)

whose overall rate is 31.8 %. Among the groups studied, the failure rate is noticeably higher among North African students at 79.52 %

with gypsy students registering 61.22 % failure. It could be affirmed, therefore, that one of the factors determining school failure is that of

cultural origin.

Table 4. Percentage of school failure by groups

Figure 2. Percentage of school failure

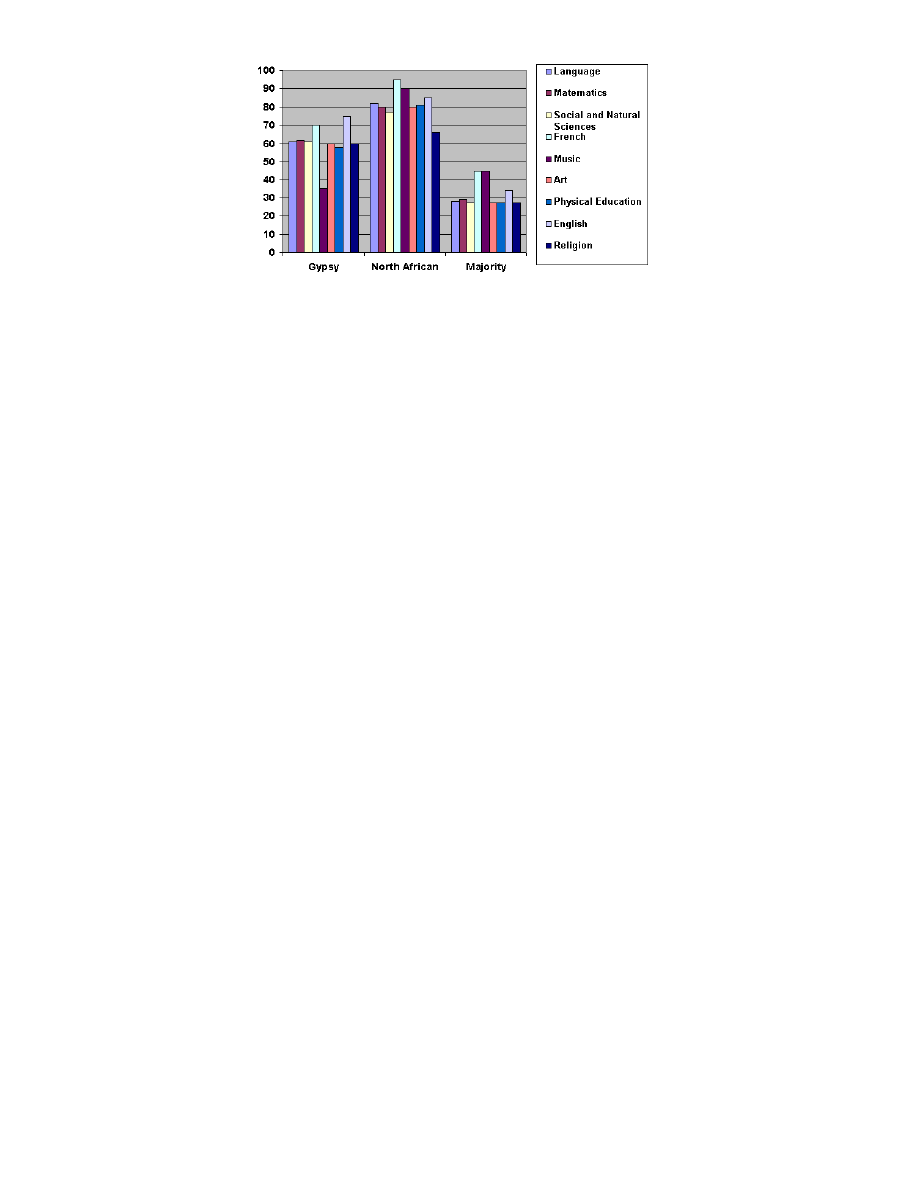

A detailed study by subject of the different education stages and cycles lead us to the following conclusions. Firstly, academic success is

greater for students from the majority culture, especially in the core subjects of Mathematics and Language than for the remainder from

minority cultural groups. While the majority culture group has a failure rate of around 28%, in the case of North Africans and gypsy

students it attains 82% and 61% respectively. Given that control of these areas is basic to access to the other subjects in the curriculum,

as well as basic skills for coping at a social level, it would be justifiable to say that the high failure and later drop out rates are proven

aspects of our education system.

Secondly, in those areas where basic core skills do not have direct repercussion on learning, such as Physical Education, Music, Art or

Religion, the success rates as much for North African as gypsy children are very similar to those obtained in core subjects. The average

success rate is around 38%. This leads to the conclusion that academic failure is not only dependent upon certain subjects, but that

students who fail tend to do so in all subjects, possibly due to multiple contextual variables among which could be cited a poor academic self

image, a low evaluation of school learning and the weak acquisition of the resources and basic skills that facilitate access to the different

subjects.

Thirdly, the average number of students from the majority culture who achieve academic success in the different subject areas nears 70%,

with only 30% failing in the learning process. This data contrasts with that of the North African and gypsy pupils who show percentages

around 20% and 38% respectively. Comparing academic failure rates between the three groups that make up the sample, the subjects with

the highest failure rates are: English, French, Language and Mathematics for the gypsy pupils and French, Music, English, Language and

Mathematics for the North Africans, as is the case for the majority culture, though at lower levels. The next diagram gives a comparative

summary of failure rates of students from different cultural groups.

Figure 3. Percentage of failure by subject area

If we analyse the academic attainment of students at the various education stages (Primary and Compulsory Secondary Education) from the

schools in the study sample, it can be seen that it is at Secondary level (1214 years) that students from different minority groups most

fail. This failure rate is even more pronounced among North African students in that a percentage of almost 97% is reached in the subjects

of Language and Mathematics and that the gypsy children have 100% failure rate in core subjects at some schools, in spite of being

Spanish speakers. In contrast, students from the majority culture do not exceed the percentage of 47% failure in any of the subjects

making up the academic curriculum. We can conclude that in spite of the lower number of pupils from gypsy and North African cultures

found in our schools compared to the majority culture at Secondary level, the failure rate of ethnic minority groups is greater in all subject

areas.

While it can be said that academic failure is influenced by a multiplicity of variables, there is no doubt that those least favoured in social and

family terms are those who bear the greatest burden of failure. Students from cultural minority groups such as the gypsies and North

Africans in our study are frequently the object of social deprivation and marginalisation hat affect their academic performance throughout

their schooling.

4. Conclusions

Below we present the conclusions obtained from the analysis.

1) The attitudes expressed by the teachers and management teams towards the presence in the schools and classes of students of other

cultures and races have been of normality. The management teams tried at all costs to convince us and show that North African and gypsy

pupils were accepted quite normally. However, in spite of expressing their acceptance in principle, they later expressed feelings of fear,

disquiet and resentment of the difficulties caused by these pupils. Similarly, teachers expressed their acceptance of the situation while fully

aware of the difficulties arising. A minority of teachers expressed fear and uncertainty of knowing how to handle these students. Likewise,

for another small minority the situation set new challenges and goals for their teaching.

2) The difficulties perceived in the presence of students from minority cultural groups are of various types. Management teams and

teachers agree in pointing out a long list of problems such as: language limitations, lack of hygiene, irregular attendance, delay in the

teaching –learning process, problems of behaviour, adaptation, and diet as well as the lack of human and material resources and

consequent increased workload. Additionally, the management teams mention the difficulties arising during the registration process since

the documentation required is not available and/or rejection found in some schools. The teachers also refer to other drawbacks linked to

professional development such as the lack of training, poor coordination between teachers in the school and the high teacherstudent

classroom ratio.

3) The needs identified by schools are those linked to an increase primarily in human resources and then in material resources, especially for

the learning of Spanish language.

4) The main objective of the teachinglearning process is the incorporation/integration into the majority group. No intercultural proposal is

put forward, this being limited to specific days or activities that do not entail understanding, appreciation or respect for the groups found in

the education context. An assimilationist viewpoint rather than an intercultural one predominates.

5) Parent and pupils of both cultures (majorityminority) acknowledge the existence of problems in peer relationships

6) Expectations focused on the school of families from minority cultures are many. North African parents on the whole see in the school the

opportunity for the realisation of many of there own unattained dreams and hopes for a better future.

7) Re student academic achievement, the following can be observed:

l

The academic achievement of students from the majority culture is superior at all education levels and stages looked at than that of

North African and gypsy pupils. The percentage of students of the majority culture who do not attain the minimum objectives

established for each cycle in which they are registered is around 30% in contrast to the North African and gypsy students with a

failure rate nearing 70%.

l

The academic failure rate is higher for North African than for gypsy pupils, a fact that may be due, among other aspects to lack of

familiarity with castellan, a key factor for school learning.

l

Pupils from the majority culture have a higher success rate in the core subjects (Language and Mathematics) than the gypsy and

North African students. Given the importance of these areas, students from ethnic minorities tend to fail in greater numbers in these

subjects and therefore in the majority of other school subjects

The presence of cultural minorities is a challenge for the school. However, it is difficult to establish positive interaction between students,

one that generates understanding, acceptance and appreciation of the other, if we put assimilation and integration before it, if this means

their abandoning their own identity traits and adopting ours. We must stop subjecting the students to the study plans designed for the

majority in the name of integration. Abandonment of ethnocentrism is the first step towards abolishing inequality among human beings.

Only from a position of equality can we speak of interculturalism. Hence it is necessary to:

l

Sensitize and make the education community aware of the role and functions to be undertaken by a democratic school and the place

ethnic minorities should have. This must start from an analysis of the school’s internal and external context and the beliefs and

actions of the teaching staff in the face of diversity.

l

Count upon an education policy that supports the encouragement and development of schools of and for everybody. It will be

necessary to provide schools with human resources (sociocultural mediators, interpreters…), and material and support resources

needed to carry out such a project.

l

Encourage the development of intercultural projects involving the whole education community. Intercultural education should be the

axis for development of the teachinglearning process and all aspects of education should be guided by its principles.

l

Design and develop plans for teacher training both at the preservice and inservice levels that can respond to the new challenges and

goals posed by the multicultural society in which we live. Teacher training courses should be based around the needs and contexts of

schools themselves.

The thread running through this study is that if we want quality education for everyone, the school must be in touch with the needs of

twenty first century society, which means rebuilding and conceiving our education system anew. Rigorous thinking is urgently called for on

the preparation offered our pupils, the methodologies employed and the curriculum established to determine whether the model

underpinning development in schools leads towards assimilation, superficial pluralism or interculturalism (Arnaiz and de Haro, 2005).

home

.

about the conference

.

programme

.

registration

.

accommodation

.

contact

Inclusive and Supportive Education Congress

International Special Education Conference

Inclusion: Celebrating Diversity?

1st 4th August 2005. Glasgow, Scotland

Academic year

Foreign student

Total

Overall Increase

Percentage Increase

1993/94

458

1994/95

589

131

28.6

1995/96

659

70

11.8

1996/97

826

167

25.3

1997/98

1,180

354

42.8

1998/99

1,927

747

63.3

1999/00

2,921

994

51.5

2000/01

4,481

1,560

53.4

2001/02

8,370

3,889

86.7

2002/03

13,462

5,092

60.8

2003/04

18,592

5,130

38.1

GROUP

Nº OF STUDENTS

PERCENTAGE

Gypsy

98

6.19 %

North African

92

5.81 %

Majority

1394

88.01 %

TOTAL

1584

100 %

Nº OF STUDENTS

PERCENTAGE

GROUP

Male

Female

Male

Female

Gypsy

49

49

50%

50%

North African

20

72

21.69%

78.31%

Majority

660

734

47.33%

52.67%

TOTAL

729

855

46.01%

53.99%

GROUP

SCHOOL SUCCESS

SCHOOL FAILURE

Gypsy

38.78%

61.22%

North African

20.48%

79.52%

Majority

71.91%

28.09%

TOTAL

67%

33%

ETHNIC MINORITIES IN SPAIN:

TEACHER, PARENT, AND STUDENT BELIEFS AND EDUCATIONAL

PERFORMANCE IN MULTICULTURAL SCHOOLS

Dr. Pilar Arnaiz; Dr. Pedro P. Berruezo; Remedios de Haro; Dr. Rogelio Martínez

Faculty of Education

University of Murcia (Spain)

parnaiz@um.es

The debate on diversity and, in particular, the inescapable challenges accompanying it, gives much food for thought to schools at the

beginning of the twenty first century. As a consequence of the migration phenomenon undergone in Europe in recent decades, cultural

diversity has become one of the main focuses of attention. Integration of foreign students is insufficient in that minority cultural groups

who have previously been overlooked also need consideration. In the Spanish context, this particularly means gypsy people. A new

education context is arising with significant and difficult challenges that, in essence, demand development of intercultural contexts.

Appropriate teacher education is essential if teachers and schools are to be endowed with new abilities, strategies and knowledge in order to

improve their practice. Only this will enable them to offer an education response adapted to the diversity of their students.

The qualitative study we present was carried out in southeast Spain where 7.3% of the population is recent immigrants from Eastern

Europe, South America and North Africa. The study focuses on the primary education system ’s response to increasing diversity in the

student population. The study was conducted in 14 schools. Archival information (demographic data, student grades) and interviews were

conducted with a diverse sample that included 14 head teachers, 97 teachers, 75 students, and 22 families. Findings suggest that schools

embrace an assimilationist view of education and have little familiarity with multicultural education notions. Important differences are

observed in the educational outcomes of various groups; specifically, academic failure affects 30% of students from mainstream culture,

80% of Moroccan and 62% of gypsy students. The authors discuss the implications of findings in the context of the history and status

these groups have had in Spanish society and identify reforms required to accommodate the educational needs of an increasingly diverse

student population in this nation.

Key words:

Interculturality, immigration, ethnic minorities, gypsy, assimilation, exclusion, inclusion, school failure, ethnocentrism.

Introduction

We live in a multicultural society. The education sphere is directly affected by this phenomenon and is taking on new characteristics,

particularly the presence of increasingly heterogeneous school populations. This requires acceptance and recognition of their differences

(ethnicity, gender, culture, social class, exceptional abilities, handicaps or giftedness) from a level playing field. Schools must meet the

challenge of developing intercultural education.

Unfortunately education research is providing worrying data in this area. The assimilationist model drives education practice and conceptions

in many primary and secondary schools, thus denying differences and leading to the failure or exclusion of certain groups. As Meirieu (2004)

points out, the desire for homogeneity spoils schools, impoverishing them and preventing interaction or opportunities to test the

knowledge of students who think or learn differently.

Various studies carried out in Spain aimed at finding out, analysing and evaluating the incorporation of and educational response to cultural

diversity (Bartolomé, 1997; Fernández Enguita, 1996, 1999; General Secretariat of the Gypsy Foundation, 2002; Valero, 2002; García and

Moreno, 2002; Garreta, 2003; Report of the Defensor del Pueblo on Schooling of Immigrant Children, 2003; and that of García Llamas et al,

2004) have exposed the limited ability of education institutions to create a school of and for everyone.

This study presents a research project (Arnaiz, 2001) developed in the Autonomous Community of Murcia aiming to describe, analyse and

evaluate the level of gradual incorporation of children from other cultures and racial groups (North African and gypsy), as well as the nature

and type of education being offered to the diverse student population present in Primary and the first two years of Compulsory Secondary

Education in this Spanish Region. It was carried out in the academic years 1997/08, 1998/99 and 1999/00.

Specifically, this study presents part of the research devoted to finding out the evolution and tendencies resulting from the migration

phenomenon both in Spain and in this Region and the repercussions in the education sphere, such as the attitude of schools and teachers

to these students and the benefits and drawbacks in curriculum development caused by their cultural differences. Once these aspects have

been explored, we go on to look at the academic performance of the different groups under study. Likewise, we examine the thoughts of

parents and children from both the minority and majority cultures on the relationships established between peers.

1. Establishing the research focus

Since the 80s, Spain has undergone a slow but inexorable increase in foreign residents, as can be seen from the following data. In 1990

there were 407,647 foreign residents; in 1996 538,984 were registered; and in 2002 the country had 1,324,001 registered foreign

residents to whom must be added the number of undocumented immigrants. That the number is gradually growing and constant is evident.

The period from 19972002 should be highlighted, in that its analysis is the key to understanding the characteristics of current immigration

in Spain. During this period, the total number of foreigners doubled, but it is not only the numbers that are of significance, but also the

principal protagonists of this acceleration. The following diagram gives the figures and origin:

Figure 1. Evolution by continent or origin of foreign residents, 19962002. Source: Annual Statistics of Foreigners 2002 (2003). Madrid:

Ministry of Interior

According to the latest figures supplied by the Ministry of the Interior (Home Office), on December 31, 2003, 1,647.011 foreigners were

registered in Spain originating from Europe (34.1%), America (32.2%), Africa (26.21%), Asia (7.2%) and Oceania (0.06). By province, the

greatest concentrations are found in Madrid, Barcelona, Alicante, Malaga, Murcia and the Balearic Islands. The Murcia Region is the fifth

autonomous community in number of foreign residents, with Africans making up 47.43% of the total and South Americans 34.65%.

The change undergone over recent decades because of the migration phenomenon is reflected in schools. The same tendency of constant

and numerically significant increase in foreign residents in the second half of the 90s commented upon above is reflected in the education

sphere. In the academic year 1999/00 annual increments of over 30%, 40% and almost 50% occurred. In just nine years we have moved

from the figure of 50, 076 foreign students in 1993/94 to that of 398, 187 in 2003/04

The autonomous communities with the highest number of foreign pupils are Madrid, Catalunya, Valencian Community, Andalusia, Canary

Islands and Murcia. Among these, the significance of the Murcian figures can be discerned if we note that Murcia is in fourth position in the

number of North African students in schooling.

The number of foreign students in the Region of Murcia has been in steady increase since 1994/95, with a noticeable rise as from 1997/98

when an increase of 42.8% on the previous year’s figures can be seen. From then until now, the growth rate has been over fifty per cent. If

in the academic year 2000/01 there were 4,481 foreign students in schooling, in just three years the figure has risen to 18,592 in 2003/04.

The table below shows the changes and rise in foreign student numbers in Murcia Region.

Table 1. Change in foreign student numbers in Murcia Region

Source: Education Statistics in Spain 200304. Advanced Data (2004). Madrid: Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport.

In this context, combined with the presence of gypsy population, our research project was set in motion (Arnaiz et al, 2001) and ran over

the academic years 1997/98, 1998/99, 1999/2000. There were two fundamental objectives: to establish the true situation and determine

proposals for improvement based upon analysis and evaluation of data obtained in pursuit of the former.

The objectives proposed for the present study are:

l

To find out the attitude of teachers and schools towards these pupils, benefits and drawbacks perceived and the reflection of cultural

differences in the curriculum offered.

l

To analyse and evaluate the academic attainment of the different groups under study.

l

To understand the ideas of parents and pupils from both minority and majority cultures on the peer relationships established.

2. Empirical Study

2.1. Population and sample

The population under study came from all the state primary schools of the Region of Murcia taking students from other cultures (in the

academic year 1997/98 these groups comprised 3,369 gypsy and 1176 North Africans in the Region). The criteria applied to make up the

sample were as follows:

l

Municipalities where the greatest numbers of North African immigrants and gypsy population were to be found.

l

Schools’ years of experience in dealing with students from cultural minority groups:

n

Schools new to dealing with students from other cultures

n

Schools with an average experience (34 years) in attending to these students.

n

Schools with a lot of experience in dealing with students from ethnic minorities.

The research sample was taken from fourteen primary schools in Murcia Region, a total of 1,584 students, from the first years of Primary

Education (68 years) until the first two years of Compulsory Secondary Education (1214 years). Pupil distribution was as follows:

Table 2. Distribution of sample by cultural group

Re the sample distribution by gender, it is worth highlighting that the number of North African boys in schooling is 78 %, whereas the

number of girls in compulsory schooling is less than a quarter, specifically 21.69 %. This contrasts with the percentages for the remaining

intake which near 50 % for male and female. The student distribution from the selected sample is as follows:

Table 3. Distribution of sample by gender

2.1. Data collection techniques

The most important technique, because of the weight given it in this study, is that of semi structured interview with the management teams

(14), teachers (97), parents and pupils from the majority culture (14 and 42 respectively) and minority (8 and 33 respectively) from the

schools under study. Information on different areas was collected according to the group interviewed. Below we set out and analyse the

information obtained.

l

School management teams and teachers: reaction to the presence of students from minority cultures in the school and classrooms,

perceived benefits and drawbacks, needs and curricular proposal on offer.

l

Students: Respect for students as much from the majority as from the minority cultures, the relationships between them, whether of

acceptance or rejection, experiences and feelings of these students as a result of living in a multicultural space.

l

Parents: What were the feelings of parents from both cultures about the relationships established between their children as well as the

hopes and expectations of parents from minority groups.

From the study of academic attainment, the evaluation reports of different courses where the sample population was to be found were

used. The evaluation report at the end of each two year cycle is an official document wherein appears information on the students over a

cycle (two academic years), specific measures taken for each pupil requiring this (support teaching and/or curricular adaptation), marks

attained in each area of the curriculum and the decision on promotion to the next level. Documents used were as follows:

l

Final Evaluation Report from the First Cycle of Primary Education (68 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the Second Cycle of Primary Education (810 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the Third Cycle of Primary Education (1012 years)

l

Final Evaluation Report from the First Cycle of Compulsory Secondary Education (1214 years)

2.3. Data analysis techniques

The research has adopted a qualitative and quantitative methodology according to the nature of the study. The model of Miles and

Huberman (1984) for the collection, summary and presentation of data and the extraction of conclusionsproofs were taken as reference for

interview analysis. The computer programme for qualitative analysis NUDIST (QSR, 1994) has helped with this task. The group devised a

calculus measure for the statistical analysis of the evaluation reports.

3. Results and discussion

We continue with the presentation of results obtained from the collection and information analysis techniques applied.

3.1. Interviews

The presentation of results begins with reactions expressed by schools and teachers to the presence of ethnic minority pupils. It is worth

mentioning that the majority of management teams interviewed saw the situation as perfectly normal. 71% said that the presence of these

pupils caused no problem in the centre, but rather they were seen as equal to other students, irrespective of their culture or country of

origin. Part of these, 21%, expressed their initial worries and doubts re this new situation in that they did not know how to behave or relate

to these students. 8% pointed out the considerable difficulties occasioned by the high numbers of ethnic minorities joining the school each

year, coupled with language deficiencies and ratio increases.

As with the management teams, the majority of the teachers reacted to the incorporation of students from different cultures with normality

and acceptance (55%). We were often surprised by expressions such as seeing these students as “just like the others”, with nothing to

distinguish them from their classmates. Yet the cultural, linguistic and social differences and all that this can contribute to school life are

patent. Alongside this attitude of normality, other teachers (28%) believed that the presence of these pupils created a series of difficulties,

problems for the classroom and school, such as interfering with the pace of the class, creating disruption and conflict, problems of

adaptation and integration, lack of contact between families and the school, unfamiliarity with the language in the case of North African

students and a long list of drawbacks, as will be seen below. 15% of teachers expressed unease and uncertainty. The main reason for this

reaction was unfamiliarity with the language and not knowing how to deal with these students. Finally, 12% of the remaining teachers

believed that the presence of these students represented a professional challenge.

Within this majority position of normality, the only advantage to the incorporation of students from different ethnic minorities, indicated, in

unequal measure by management (78.57%) and teachers (15%) was that of cultural enrichment, the opportunity to find out about another

culture. Among the teachers, this view was put forward by those who had gypsy students in their classes. They believed the enrichment

was twosided (majority and minority cultures) in that knowledge of other cultures was deepened, as can be seen from the following

quotations:

“The main advantage is the enrichment all students derive, because they become more open minded. Whenever possible, benefit is taken

from this.”

(Management Team Centre 11)

“It is a source of enrichment for everyone as long as other cultures are studied and we take advantage of these students’ presence. The

other students can learn their language, their customs and culture. This is very gratifying as it brings us closer.”.

(Teachers Centre 11)

In contrast to this single advantage found by the majority of school management teams and a minority of teachers, we can find a long list

of disadvantages and/or drawbacks to these pupils’ presence, pointed out by both and that, oddly enough are always laid at the pupil’s

door. Hence we would like to point out that these students’ presence in schools has supposed, in the words of Enguita (1999, 135, 136),

“… little short of a torpedo to the flotation line of the school ship, however much they are accepted and assumed” and, therefore, “to

claim that there is nothing new under the sun is a way of sidestepping the issue and, in fact, is what a good number of teachers do”.

Re schools with North African students, the main drawback encountered is that of unfamiliarity with the language and for those with gypsy

students that of absenteeism. In the case of the former, the language is perceived as the main handicap to the teachinglearning process or

even the normal pace of the class, combined with adaptation problems in that, according to teachers, these inhibit relationships based on

equality.

In the case of gypsy children, it would seem that absenteeism is seen as the main disadvantage deriving from their presence in schools with

this ethnic minority. Irregular attendance causes disturbance to the normal class rhythm in that the pupils fall out of step with the class

level. A greater effort from the teachers is also required in that extra work has to be prepared for these pupils. Absenteeism is a more acute

problem among gypsy students and does not significantly affect the North African pupils, but they are held back by other factors such as

late commencement of schooling which frequently causes learning difficulties. Both groups are affected by drop out from schooling as from

the age of 13/14, especially girls.

“The problem is communication. When the students speak the language, there is no problem.”

(Teachers Centre 4)

“It can be frustrating when you have done your best and there are children who continue to be absent or leave because they are

itinerant.”

(Management team– Centre 8)

Another drawback found in five of the schools was that of rejection among students, both inside and outside the classroom. Specifically, in

three of these schools there have been outbreaks of racism and xenophobia, especially between gypsy and North African pupils. The

management teams told us that these students have serious behaviour problems between themselves and with the rest of the school

population. This situation has created a certain tension in peer group relationships, with a marked tendency for students from the same

racial group to stay together, both in school time and beyond.

“There have been few disadvantages, but there have been situations of tension and rejection among students”.

(Management team– Centre 5)

Similarly, teachers talk of confrontation and rejection, saying that relationships between students of different cultures are good within the

classroom, but at break times and out of school times they are more problematic or non existent. Thus in the playground it can be seen

that pupils form groups with those from their own culture.

Another difficulty as perceived by management teams and teachers is that of lack of school books and equipment, particularly among gypsy

pupils. They also refer to behaviour problems, especially the difficulty some North Africans and/or gypsies have with complying with school

rules and behaving well in class. Four schools also mentioned problems due to a lack of hygiene in pupils from certain ethnic minorities,

claiming that these pupils come to school dirty and smell, so provoking rejection by their classmates.

“Of the gypsies, they complain of their lack of hygiene, their smell, rather than their ethnicity. There are children who smell very

bad, of urine, faeces or sweat, so that no one can go near them…”.

(Management Team– Centre 13)

Only in three centres do problems connected with health and food appears. These refer to an unbalanced diet. Those interviewed claimed

that the gypsies tend to eat badly: they do not pay attention to the healthgiving properties of food, they eat an excess of industrialised

cakes and sweet foods and have no fixed meal times. In the case of North African students, it was found that their economic situation

affected their nutrition and they could not always eat several times a day, sometimes only eating at school lunch times.

Along with this list of drawbacks, seven of the school management teams mentioned the lack of material, economic and human resources to

answer the pupils’ needs in that the education authorities did not send them in accord with students’ arrival.

“We do not have enough material or human resources, only the good will of the teachers, which is, of course, very important”.

(Management team– Centre 4)

The same proportion of schools mentioned the considerable difficulties caused when North African students joined the school and began

their studies because they bought no documentation of their previous schooling.

Other disadvantages mentioned by the teaching body referred to: increased workload, lack of human resources, poor coordination among

the teachers and lack of training. Teachers highlight the extra work that this type of student causes, given that they need a lot of time and

attention. Also stressed is the need to prepare material especially for the North Africans because of language limitations.

“Teachers have to do three times the amount of planning: for those who are achieving the normal curriculum goals, for those

who fall short because of handicaps and require support and for those who exceed who also need a different type of work”.

(Teachers – Centre 10)

Teachers recognise their lack of training to deal with the cultural diversity of the schools. They also point out that sometimes there is no co

ordination between colleagues and a lack of human resources to support these students.

“If I had specific training, it would not matter to me if the child were North African or Russian. The problem is what I do with hi

m ”.

(Teachers– Centre 2)

Faced with all these drawbacks to the presence of students from ethnic minorities, management teams and teachers totally agree about

their needs, putting human resources in first place and material resources in second as the solution to the problem. The prime objective

identified by schools and teachers is the integration of these students, an integration they understand as adoption of the values, customs

and culture of the majority group. Thus it can be seen that while at a theoretical level there is hope of acceptance, of responding to the

demands of cultural diversity, at a practical level difficulties and problems arise in its execution because of an absence of an intercultural

project. Therefore, once the objectives of integration and language learning have been attained, teachers move on to work on the curricular

objectives according to pupils’ stage of schooling without adapting them in any way. Thus, the process becomes that of mere assimilation

of ethnic minority pupils.

“Like the rest of the staff, within my classroom I teach everyone. My subject is the same for all my students, the reality is that

they are the same as everyone else. Normally I make no distinctions among my students and neither do they, so differences disappear ”.

(Teachers – Centre 10)

Intercultural education is relegated to the celebration of peace day or other specific events, so that it takes on a marginalised, deficient and

anecdotal character in that it does not run through the whole teachinglearning process. In short, the majority of teachers admit to not

doing any kind of multicultural activity, excusing themselves because they do not know the culture, do not have time or it is difficult to

integrate it into the curriculum plans. Dealing with diversity is therefore not present in a school life that only sees the majority cultural

viewpoint.

In the light of this situation, gypsy and North African families stress the importance of the school. However, many express their discontent

with the fact that there is an absence of their cultural traits in the curriculum, affirming that their children are forced into the cultural and

school model of the majority culture. The desire expressed by all the families interviewed is for recognition of equality within difference, that

the school should become a space open to interculturalism. The protagonists’ words sum this up:

“When the school has different groups of students, I would recommend that an important point to deal with is that of inter

culturalism, with the aim of not excluding any culture and not imposing the majority culture. This enriches not only the minorities, but

everyone.”

(Cultural minority parents– Centre 3)

If the beliefs of the parents and pupils of the majority and minority cultures on peer relationships are borne in mind, it can be seen that

interculturalism remains very distant. Half of parents from the minority culture interviewed confirm the rejection suffered by their children.

If we look to parents from the majority culture, in spite of their perception of a climate of acceptance in the schools, they point out a series

of negative aspects, among which rejection, for various motives, stands out. In some contexts, language limitations cause situations of

rejection or non acceptance because of misunderstandings between students. Most of the parents from the majority culture, who were

interviewed, with the exception of those from one centre, claimed that these students had problems adapting to the education system.

Among the reasons given behaviour problems and their refusal to associate with other classmates should be mentioned.

“There are North African students who do not want to integrate, nor their parents. However, until they integrate there cannot be equality

of education”.

(Majority culture parents– Centre 4)

Re rejection, students from the majority culture as much as those from the minority culture openly admit to the scarcity of contacts

between each group and even occasions of rejection.

“Each goes their own way…Often, outside school, you see them in the street and say hello, but nothing more”.

(Majority culture students– Centre 4)

“I don’t talk to them, don’t trust them and they are not my friends”.

(Minority culture students– Centre 4)

3.2. Academic Attainment

We will now look at the success and failure rate of pupils from the groups under study. Analysis of the academic results of pupils studying

in the schools from the sample indicates that the average of those who successfully pass the level in which they are registered is 67 % as

opposed to 33 % who fail. These failure rates can be influenced, among other factors, by the variable of “cultural origin” in that the

percentage of students from the majority culture who pass the level is 71.91 %, compared to the remainder (North African and gypsy)

whose overall rate is 31.8 %. Among the groups studied, the failure rate is noticeably higher among North African students at 79.52 %

with gypsy students registering 61.22 % failure. It could be affirmed, therefore, that one of the factors determining school failure is that of

cultural origin.

Table 4. Percentage of school failure by groups

Figure 2. Percentage of school failure

A detailed study by subject of the different education stages and cycles lead us to the following conclusions. Firstly, academic success is

greater for students from the majority culture, especially in the core subjects of Mathematics and Language than for the remainder from

minority cultural groups. While the majority culture group has a failure rate of around 28%, in the case of North Africans and gypsy

students it attains 82% and 61% respectively. Given that control of these areas is basic to access to the other subjects in the curriculum,

as well as basic skills for coping at a social level, it would be justifiable to say that the high failure and later drop out rates are proven

aspects of our education system.

Secondly, in those areas where basic core skills do not have direct repercussion on learning, such as Physical Education, Music, Art or

Religion, the success rates as much for North African as gypsy children are very similar to those obtained in core subjects. The average

success rate is around 38%. This leads to the conclusion that academic failure is not only dependent upon certain subjects, but that

students who fail tend to do so in all subjects, possibly due to multiple contextual variables among which could be cited a poor academic self

image, a low evaluation of school learning and the weak acquisition of the resources and basic skills that facilitate access to the different

subjects.

Thirdly, the average number of students from the majority culture who achieve academic success in the different subject areas nears 70%,

with only 30% failing in the learning process. This data contrasts with that of the North African and gypsy pupils who show percentages

around 20% and 38% respectively. Comparing academic failure rates between the three groups that make up the sample, the subjects with

the highest failure rates are: English, French, Language and Mathematics for the gypsy pupils and French, Music, English, Language and

Mathematics for the North Africans, as is the case for the majority culture, though at lower levels. The next diagram gives a comparative

summary of failure rates of students from different cultural groups.

Figure 3. Percentage of failure by subject area

If we analyse the academic attainment of students at the various education stages (Primary and Compulsory Secondary Education) from the

schools in the study sample, it can be seen that it is at Secondary level (1214 years) that students from different minority groups most

fail. This failure rate is even more pronounced among North African students in that a percentage of almost 97% is reached in the subjects

of Language and Mathematics and that the gypsy children have 100% failure rate in core subjects at some schools, in spite of being

Spanish speakers. In contrast, students from the majority culture do not exceed the percentage of 47% failure in any of the subjects

making up the academic curriculum. We can conclude that in spite of the lower number of pupils from gypsy and North African cultures

found in our schools compared to the majority culture at Secondary level, the failure rate of ethnic minority groups is greater in all subject

areas.

While it can be said that academic failure is influenced by a multiplicity of variables, there is no doubt that those least favoured in social and

family terms are those who bear the greatest burden of failure. Students from cultural minority groups such as the gypsies and North

Africans in our study are frequently the object of social deprivation and marginalisation hat affect their academic performance throughout

their schooling.

4. Conclusions

Below we present the conclusions obtained from the analysis.

1) The attitudes expressed by the teachers and management teams towards the presence in the schools and classes of students of other

cultures and races have been of normality. The management teams tried at all costs to convince us and show that North African and gypsy

pupils were accepted quite normally. However, in spite of expressing their acceptance in principle, they later expressed feelings of fear,

disquiet and resentment of the difficulties caused by these pupils. Similarly, teachers expressed their acceptance of the situation while fully

aware of the difficulties arising. A minority of teachers expressed fear and uncertainty of knowing how to handle these students. Likewise,

for another small minority the situation set new challenges and goals for their teaching.

2) The difficulties perceived in the presence of students from minority cultural groups are of various types. Management teams and

teachers agree in pointing out a long list of problems such as: language limitations, lack of hygiene, irregular attendance, delay in the

teaching –learning process, problems of behaviour, adaptation, and diet as well as the lack of human and material resources and

consequent increased workload. Additionally, the management teams mention the difficulties arising during the registration process since

the documentation required is not available and/or rejection found in some schools. The teachers also refer to other drawbacks linked to

professional development such as the lack of training, poor coordination between teachers in the school and the high teacherstudent

classroom ratio.

3) The needs identified by schools are those linked to an increase primarily in human resources and then in material resources, especially for

the learning of Spanish language.

4) The main objective of the teachinglearning process is the incorporation/integration into the majority group. No intercultural proposal is

put forward, this being limited to specific days or activities that do not entail understanding, appreciation or respect for the groups found in

the education context. An assimilationist viewpoint rather than an intercultural one predominates.

5) Parent and pupils of both cultures (majorityminority) acknowledge the existence of problems in peer relationships

6) Expectations focused on the school of families from minority cultures are many. North African parents on the whole see in the school the

opportunity for the realisation of many of there own unattained dreams and hopes for a better future.

7) Re student academic achievement, the following can be observed:

l

The academic achievement of students from the majority culture is superior at all education levels and stages looked at than that of

North African and gypsy pupils. The percentage of students of the majority culture who do not attain the minimum objectives

established for each cycle in which they are registered is around 30% in contrast to the North African and gypsy students with a

failure rate nearing 70%.

l

The academic failure rate is higher for North African than for gypsy pupils, a fact that may be due, among other aspects to lack of

familiarity with castellan, a key factor for school learning.

l

Pupils from the majority culture have a higher success rate in the core subjects (Language and Mathematics) than the gypsy and

North African students. Given the importance of these areas, students from ethnic minorities tend to fail in greater numbers in these

subjects and therefore in the majority of other school subjects

The presence of cultural minorities is a challenge for the school. However, it is difficult to establish positive interaction between students,

one that generates understanding, acceptance and appreciation of the other, if we put assimilation and integration before it, if this means

their abandoning their own identity traits and adopting ours. We must stop subjecting the students to the study plans designed for the

majority in the name of integration. Abandonment of ethnocentrism is the first step towards abolishing inequality among human beings.

Only from a position of equality can we speak of interculturalism. Hence it is necessary to:

l

Sensitize and make the education community aware of the role and functions to be undertaken by a democratic school and the place

ethnic minorities should have. This must start from an analysis of the school’s internal and external context and the beliefs and

actions of the teaching staff in the face of diversity.

l

Count upon an education policy that supports the encouragement and development of schools of and for everybody. It will be

necessary to provide schools with human resources (sociocultural mediators, interpreters…), and material and support resources

needed to carry out such a project.

l

Encourage the development of intercultural projects involving the whole education community. Intercultural education should be the

axis for development of the teachinglearning process and all aspects of education should be guided by its principles.

l

Design and develop plans for teacher training both at the preservice and inservice levels that can respond to the new challenges and

goals posed by the multicultural society in which we live. Teacher training courses should be based around the needs and contexts of

schools themselves.

The thread running through this study is that if we want quality education for everyone, the school must be in touch with the needs of

twenty first century society, which means rebuilding and conceiving our education system anew. Rigorous thinking is urgently called for on

the preparation offered our pupils, the methodologies employed and the curriculum established to determine whether the model

underpinning development in schools leads towards assimilation, superficial pluralism or interculturalism (Arnaiz and de Haro, 2005).

home

.

about the conference

.

programme

.

registration

.

accommodation

.

contact

Inclusive and Supportive Education Congress

International Special Education Conference

Inclusion: Celebrating Diversity?