117

Humour effect on memory and

attitude: moderating role of

product involvement

Hwiman Chung

New Mexico State University, Las Cruces

Xinshu Zhao

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This study examined the moderating effects of product involvement on the effects of

humour on memory and attitude towards the advertisement by using multi-year survey

(1992 to 1997) of responses to commercials shown during the Super Bowl. Positive and

significant relationships between humorous advertisements on memory and attitude were

found through multiple regression analysis. Furthermore, results show that humorous

advertisements are more effective in low-involvement products in terms of memory and

attitude towards the advertisement.

Due in part to the popularity of using humorous advertising

campaigns (according to Weinberger and Spotts, 24.4% of prime-time

television advertising in the USA is intended to be humorous), the

advertising scholars have studied the effects of humorous advertising

campaigns on advertising effectiveness (e.g. Markiewicz 1974; Cantor

& Venus 1980; Belch & Belch 1983; Duncan et al. 1983; Gelb & Pickett

1983; Sutherland & Middleton 1983; Madden & Weinberger 1984).

Sternthal and Craig (1973) drew some tentative but useful conclusions

about the effects of humour on advertising by reviewing the early

literature on humour in general, and Gelb and Pickett (1983) and

Spotts et al. (1997) provide some theoretical discussions of how

humorous advertising may affect consumers. These discussions

consider the use of humorous messages, which can create some

positive (favourable) attitudes towards the advertised brand through a

transfer of effect created by the ad to the brand. This transfer of

International Journal of Advertising, 22, pp. 117–144

© 2003 Advertising Association

Published by the World Advertising Research Center, Farm Road, Henley-on-Thames,

Oxon RG9 1EJ, UK

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 117

effect has been proven by researchers in consumer behaviour (Ray &

Batra 1983; Holbrook & O’Shaughnessy 1984; Mitchell 1986).

In terms of advertising effectiveness, numerous studies have

suggested that advertising liking could contribute to an advertise-

ment’s effectiveness in terms of recall, brand preference or persuasion

(Du Plessis 1994; Hollis 1995). As Du Plessis (1994) and Walker and

Dubitsky (1994) reported, commercial liking (or attitude towards the

ad) relates positively to advertising recall. One theoretical background

for this relationship is that likeable or well-liked advertisements can

affect an individual’s information processing by creating positive

arousal, increasing the memory of the advertised material, and

creating more favourable judgements of the advertisement message

(Edell & Burke 1986; Aaker & Myers 1987). Our purpose extends

work in this research stream by considering the issues of product

involvement. The primary focus of previous studies of the effects of

humorous advertisements has been on attitude towards the

advertisement and memory. In this study, we include product

involvement as a moderating variable to provide insight into the

differences of humorous ads on subjects’ attitudes towards the ad and

memory. The purpose of the study is to add to the body of knowledge

regarding the effects of humorous advertisements on cognitive and

affective aspects of

advertising effectiveness and product

involvement. It is usually agreed among advertising practitioners that

we should not use humorous advertising for high-involvement prod-

ucts because it may cause effects opposite to those we intended. It is

important for advertising practitioners to understand what exact

effects humorous messages have, compared with non-humorous

advertising, because often the advertising objective is to get high recall

for an advertised brand by increasing the amount of attention. If,

indeed, humorous appeal is more effective in terms of grabbing

attention, high recall and message comprehension, it will be much

easier for advertising practitioners to develop an advertising message.

As some researchers argue that advertising studies which use

laboratory settings are weak in their ‘generalisability’ (see, for example,

Zhao 1997), this study also tries to find the effects of humour on

memory and attitude in a natural television-watching environment.

118

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 118

BACKGROUND

How different message appeal in an advertisement relates to the

effectiveness of that advertisement is a long-standing and unsolved

question. Academic studies report inconsistent results on the

effectiveness of humour in ads, but the absence of systematic

empirical results contrasts with humour’s widespread use (Markiewicz

1974) and the intuitive belief of advertisers that humour in ads

enhances persuasion (Madden & Weinberger 1984). Considerable

anecdotal evidence suggests that humorous advertisements can be

effective in selling products in many diverse product categories such as

soft drinks, cars and insurance (Markiewicz 1974). In addition,

research in advertising has investigated the effects of humorous

advertisements on many other response variables such as memory,

advertising liking, brand attitude and purchase intention. Even though

there has been considerable research, the findings fail to show a

systematic effect of humour on recall, recognition and ad liking.

Furthermore, few studies have focused on the differences of humour

effects across product categories. A rule of thumb among advertising

practitioners is to avoid humorous advertising for high-involvement

products because the results may be counterproductive. Because the

advertising objective is often to get high brand recall through high

attention, it is important that advertising practitioners understand the

exact effects of humour appeal compared with non-humorous

advertising. If humour is indeed more effective at grabbing attention,

supporting high recall and aiding message comprehension, advertising

practitioners may be wise to add a few laughs to their advertising

messages.

Researches about effects of humour

In 1973, Sternthal and Craig drew some tentative but useful conclu-

sions about the effects of humour in advertising by reviewing the early

literature on humour in general. Even though the literature they

reviewed is small, and not specific to advertising, their conclusions

about the often positive effects of humour eased the way for future

studies on the effects of humour. After Sternthal and Craig’s study,

Murphy and colleagues (1979) studied the effect of TV programme

types on the recall of humorous TV commercials. They found that the

programme environments within which humorous ads appear affect

the performance of both ads and items in tests of unaided recall. They

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

119

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 119

1

Footnote.

found that overall ad recall is much higher for humorous ads than for

non-humorous ads. Unlike Murphy et al.’s study, which was done in a

laboratory setting, Cantor and Venus (1980) tested the effect of

humour in radio ads on memorability and persuasiveness in a quasi-

natural setting. The results of their study also support the general

conclusions drawn by Sternthal and Craig.

Most advertising practitioners already used humorous advertise-

ments to promote products and services. According to Markiewicz

(1974), humorous advertising on TV and radio accounted for as much

as 42% of the total. A survey of executives in leading agencies

revealed that 90% of the respondents believed that humour enhances

advertising effects (Madden & Weinberger 1984). Further, it was

estimated that 24% of prime-time television advertising in the USA

used humorous messages (Weinberger & Spotts 1989).

Madden and Weinberger (1982) studied the effects of humour on

attention levels, but, unlike previous studies, they used magazine

advertisements to test the effects of humour. They also tested whether

the potential heightening of attention is moderated by audience

factors such as race and gender. They found that humorous

advertisements outperformed normal ads on each recall category.

Gelb and Pickett (1983) tried to find out whether humour in an ad

influenced cognitive components (e.g. ad liking/disliking, attitude

towards ad, attitude towards brand, and purchase intention of

advertised product), as well as attention and recall. They found a

relationship between the perception of humour in an ad and a positive

attitude towards the ad, although the direction of causal flow is

unknown. They also found a positive relationship between attitude

towards brand and perceived humour. However, the perception of

humour in an ad was not related to purchase intention. Belch and

Belch (1983) found similar results. They found that humorous

messages are evaluated more favourably by the audience than serious

messages, and they produce more positive perceptions of advertiser

credibility, more favourable attitudes towards the ad, and more

favourable cognitive responses. However, attitude towards using the

advertised product (in this case the product was the services of

Federal Express) and purchase intention were not affected differently

by serious vis-à-vis humorous messages.

Lammers and colleagues (1983) also tried to understand the

persuasive effects of humour by using trace consolidation theory.

They hypothesised that a more humorous message would increase

120

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 120

1

Footnote.

persuasion-related measures (cognitive responses and attitude) in the

long run. It was found that when cognitive response measures were

taken immediately after subjects were exposed to ad materials, there

was little difference between the serious and humorous ads. However,

when cognitive response measures were delayed, the humorous appeal

produced more cognitive responses than the serious appeal. It was also

found that most of the increased cognitive activity came in the form

of pro-argumentation. They concluded that humorous appeal may be

more effective than serious appeal because humour, in the long run,

stimulates more favourable cognitive responses. Sutherland and

Middleton (1983) also tried to expand the effects of humour to

include message credibility as well as recall. They found, however, that

although humour can attract audience attention, there is no difference

between straight and humorous appeals in terms of recall of the

advertising message. Moreover, they found that straight messages are

more likely to be judged as credible than humorous messages and that

straight messages have more authority than humorous messages. Thus

Sutherland and Middleton’s study produced totally different results

compared with previous studies of recall and credibility.

Duncan and colleagues (1983) re-examined the effects of humour

on advertising comprehension by focusing on type of humour

measurement (manipulated vs. perceived) and humour location in the

advertisement. Their results also confirmed the results of previous

studies about the effects of humour on advertising comprehension.

Duncan and Nelson (1985) also found that humour can increase

attention paid to an ad, improve advertising liking, reduce irritation

experienced from the commercial and increase product liking. Just as

in previous studies, however, humour did not have any influence on

purchase intention. They concluded that humorous ads seem to be

more appropriate for generating awareness than for generating

persuasion or purchase intention.

Recently, advertising scholars used different approaches to study

the effects of humour by focusing on the role of moderating or

mediating variables on the effects of humour, such as advertising

repetition, prior exposure to ad messages and audience size. Zhang

and Zinkhan (1991) studied the effects of humour in ads in relation to

ad repetition and size of audience. They found that humorous ads

tend to produce higher levels of perceived humour, positive brand

attitude and brand information recall. However, ad repetition has no

influence on perceived humour and overall effectiveness of

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

121

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 121

1

Footnote.

advertising. Further, Zhang (1996) studied the effects of humour in

print ads using ‘need for cognition’ as a mediating variable and found

that the effect of humour is moderated by individual differences in

need for cognition. Chattopadhyay and Basu’s study (1990) found that

the effect of humour on consumer attitude and choice behaviour was

moderated by the message recipient’s prior evaluation of the

advertised brand. Therefore, when prior brand evaluation is positive,

humorous ads are more effective than non-humorous ads and vice

versa.

In sum, previous research has failed to prove consistently superior

persuasive effects of humorous ads over non-humorous ads. The

absence of empirical results contrasts with humour’s widespread use

in many different products (Markiewicz 1974) and the intuitive belief

of advertising practitioners that humour in ads enhances persuasion

(Madden & Weinberger 1984). Most studies measuring the effects of

humorous ads on recall and comprehension suggest that findings are

mixed; that is, some found positive effects and others found negative

effects. However, most studies of source credibility and liking of

source found that humorous ads have a positive influence. Finally,

several studies found that humorous ads do not have a positive impact

on choice behaviour, such as purchase intention.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Cognitive and affective effects of humour

Humour’s effects on the cognitive process have usually been measured

in terms of memory and comprehension. In advertising research, the

emphasis has been on memory rather than on comprehension

(Du Plessis 1994). Advertising researchers have identified recall and

recognition as processes that access memory traces of commercial

messages. Although the recall and recognition to measure advertising

effectiveness is a long-standing debate (see Du Plessis (1994) for a

review), the fundamental difference between the two is that recall is

measured by asking subjects to specify the stimulus without aid,

whereas recognition is measured by asking subjects to identify whether

they have seen or heard the stimulus before. Krugman (1986) argues

that recall and recognition measures are different in nature and

suggests that the advertising industry has failed to make the

distinction.

122

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 122

1

Footnote.

There is no simple way to decide which method is most useful. In

some situations, advertising research requires either recall or

recognition measures; in other cases, both recall and recognition are

required. The threshold theory posits that recall and recognition

measure the same memory but that recognition requires a lower

threshold of familiarity (Kintsch 1970). However, according to the

dual-process hypothesis (Anderson & Bower 1972), recall consists of

two steps – memory search and recognition. In this sense, recognition

is a sub-process of recall. To recall items, a subject generates possible

candidates for recall during the search process and then selects items

through recognition. It is therefore a logical explanation that

recognition is less sensitive than recall and understandable that

recognition scores are substantially higher than recall scores. Thus to

gain higher recall, a stronger encoding process and more frequent

exposure is needed.

Humour’s effects on recall and recognition may be explained by

operant conditioning theory. As Nord and Peter (1980) explain,

operant conditioning occurs when the probability that an individual

will emit one or more behaviours is altered by changing the events or

consequences that follow the particular behaviour. Unlike

information-processing theory, operant conditioning views humour as

a reward for listening to the advertising message (Phillips 1968).

Therefore, a humorous advertisement could be better understood and

recalled than a similar non-humorous advertisement because humour

was a positive reinforcement. This better memory may also be

explained by the positive impact of emotional arousal (effect) to

memory. Ambler and Burne (1999) posit that if consumers are

emotionally aroused while watching commercials, those commercials

are more likely to be recalled by them. Thus they argue that advertising

with high affective components is more likely to be remembered by

consumers. In this sense, it is possible that consumers can be

emotionally aroused through watching humorous advertisements and

this emotional arousal in turn affects consumers’ memory over

advertisements. Another possible rationale for the effects of humour

is Helson’s adaptation-level theory (1959), which deals with the

capacity of a stimulus to attract attention. Each stimulus that an

individual encounters becomes associated with an adaptation or

reference level. Thus attention is attracted when the individual

perceives the focal stimulus to be plainly different from its reference

stimuli. In this case, humour specific to an advertising context or

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

123

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 123

1

Footnote.

perceived as exceptional will be noticed because, in general, unique

advertisements are learned and recalled better than non-humorous

commercials. Therefore, the first hypothesis regarding the humour

effect is as follows:

H1:

Degree of perceived humour in an advertisement will be

positively related to the unaided and aided recall.

As indicators of advertising effectiveness, Attitude towards the ad

(hereafter Aad), Attitude towards the brand (hereafter Ab) and

Purchase Intention (hereafter PI) are usually examined. Many studies

have reported Aad as a mediator of advertising effects on Ab and PI

(Mitchell & Olson 1981; Lutz 1985; MacKenzie et al. 1986; Holbrook

& Batra 1987). In 1981, Mitchell and Olson first introduced the notion

that consumers’ choice behaviour is likely to be influenced by attitude

towards the advertising stimulus. Mitchell and Olson (1981) proposed,

and found empirical support for, the mediational effects of attitude

towards the ad. They suggested that Aad should be considered as

distinct from beliefs and brand attitudes. Using a classical conditioning

approach, they reasoned that the pairing of an unknown brand name

(unconditioned stimulus) with a highly valenced visual (conditioned)

stimulus probably causes the transference of affect from ad to brand.

Researchers have since shown that Aad, which is defined as an

affective construct representing feelings of

favourability/

unfavourability towards the advertising itself, mediates the effects of

advertising content on Ab and consumers’ Acb (Attitude towards

choice behaviour) (Mitchell & Olson 1981; Shimp 1981; Lutz 1985;

MacKenzie et al. 1986; MacKenzie & Lutz 1989). This mediating role

of Aad has been found continuously in many other consumer studies

(Belch & Belch 1983; Gelb & Pickett 1983; Park & Mittal 1985;

Zinkhan & Zinkhan 1985; Park & Young 1986; Zhang 1996).

Recently, however, some studies have found the reverse relationship

between Aad and Ab (see e.g. Madden & Ajzen 1991). That is, in some

cases, consumers’ prior attitudes towards the brand also influence

positively or negatively their attitudes towards the advertisement of

that brand (Machleit & Wilson 1988). Thus, in a familiar brand,

attitude towards the advertisement will be influenced by consumers’

prior attitude towards the brand.

In the advertising area, the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF)

Copy Research Validation project has emphasised the role of ‘liking’ a

commercial as an important evaluative measurement (Haley &

124

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 124

1

Footnote.

Baldinger 1991). The basic question relating to commercial liking is

whether likeable advertising is inherently more effective than less

likeable advertising. In broader terms, there are two primary rationales

to explain how ad liking might contribute to advertising effectiveness.

The first has to do with cognitive processing. If consumers like the

advertising they are more likely to notice and pay attention to the ads

and more likely to assimilate and respond to the advertising message.

The second rationale has to do with affective response. According to

Lutz’s (1985) affect transfer model, if consumers experience positive

feelings towards the advertising, they will associate those feelings with

the advertiser or the advertised brand. Thus the more the ad is liked,

the more positive feelings are created towards the brand. As seen in

previous studies, several advertising scholars have found that

perceived humour in an advertisement has an impact on the message

receiver’s attitude towards the ad (Belch & Belch 1983; Gelb & Pickett

1983). That is, the more humour the receiver perceives in the

advertisement, the more favourable attitude towards the ad the

receiver has. This finding is also confirmed by Chung and Zhao

(2000). Thus the second hypothesis is suggested:

H2:

Degree of perceived humour in an advertisement will be

associated positively with the attitude towards the ad.

Moderating role of product involvement

In the advertising research area, involvement has a long history. First,

Krugman drew the involvement issue to the forefront of advertising

research. Applying learning theory, Krugman (1965, 1977) found that

people remembered better those ads which were presented first and

last. Krugman (1965) argued that advertising actually had low levels of

involvement. He also operationalised the involvement as the number

of ‘bridging experiences’, namely connections or personal references

per minute that the viewer made between his own life and the

advertisement. Since Krugman’s seminal argument about television

advertising, the construct of involvement has emerged as an

important factor in studying advertising effectiveness (Wright 1973;

Krugman 1977; Rothschild 1979; Petty & Cacioppo 1981a, 1981b;

Petty et al. 1981; Petty et al. 1983; Greenwald & Leavitt 1984). In these

studies, involvement usually refers to: personal relevance to the

message and product (Petty & Cacioppo 1981; Engel & Blackwell

1982; Greenwald & Leavitt 1984); arousal, interest, or drive evoked by

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

125

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 125

1

Footnote.

a specific stimulus (Park & Mittal 1985); a person’s activation level

(Cohen 1982); and goal-directed arousal capacity (Park & Mittal 1985;

Park & Young 1986).

The variables proposed as the antecedents of involvement may be

divided into three categories. The first relates to the characteristics of

the person, the second relates to the physical characteristics of the

stimulus. Thus involvement will be different according to the types of

media or content of the communication. The third category relates to

the situation. For example, the person’s involvement will be different if

he or she watches the advertising when planning to buy that product.

These three categories are usually used for ascertaining involvement.

Among these proposed antecedents, the second and third categories

were based on the assumptions that involvement is activated by

external stimulus (Taylor & Joseph 1984).

Although involvement has been recognised as an interaction

between individual and external stimuli, product involvement has been

defined as ‘salience or relevance of a product rather than an

individual’s interest in a product’ (Salmon 1986). Recently, researchers

divided product involvement into two distinct types. The first type is

situational involvement

, which reflects product involvement that occurs

only in specific situations. The second type is enduring involvement, which

represents an ongoing concern with a product that transcends

situational influences (Houston & Rothschild 1978; Rothschild 1979).

All these constructs are focused mainly on the external stimulus rather

than on an individual’s general interest in a product.

Analysing individuals’ common interest in a product is very

important in the sense that marketers and advertisers need some

baselines to segment markets according to consumers’ product

involvement. In this sense, the construct ‘product involvement’ has a

meaning that may be used for the majority of consumers. Therefore,

the term ‘product involvement’ used in the business area has a very

different meaning compared with those constructs that are focused

mainly on relations between individual and specific external stimuli.

‘Product involvement’ is often used interchangeably with ‘perceived

product involvement’ in the marketing literature (Kapferer & Laurent

1985). The meaning and definition of ‘product involvement’ differ

across researchers. For example, Cushing and Douglas-Tate (1985)

defined ‘product involvement’ as ‘how the product fits into that

person’s life’ (p. 243). To them, product involvement is a sort of

degree of importance to a person. To Zaichkowsky (1985), product

126

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 126

1

Footnote.

involvement is referred to as the relevance that individuals perceive in

the product’s values according to their own interests and needs.

Similarly, Tyebjee (1979) describes product involvement as strength of

belief about the product class, but others characterise involvement in

the product class as the relevance or salience of a product class to

receivers (Mitchell 1979; Greenwald & Leavitt 1984; Zaichkowsky

1985).

The Elaboration Likelihood Model (hereafter ELM: Petty &

Cacioppo 1981a, 1986a, 1986b) posits that persuasion can occur via

two routes – the central and peripheral routes. The central route

requires a person’s cognitive elaboration of advertising message

(persuasive message in their studies), and the peripheral route occurs

in the absence of cognitive elaboration for those persuasive

arguments. According to ELM, a person’s processing of information

differs by his or her level of involvement. When consumers have high

MAO (Motivation, Ability and Opportunity) to process communi-

cation, they are willing or able to exert a lot of cognitive processing

effort, which is called high-elaboration likelihood.

On the contrary, when MAO is low, consumers are neither willing

nor able to exert a lot of effort. However, a person’s elaboration

likelihood is also influenced by situational variables such as product

type. That is, a high-involvement product situation would enhance a

person’s motivation for issue-relevant thinking and increase a person’s

‘elaboration likelihood’, so the central route to persuasion will

probably be induced. A low-involvement product situation would

probably create low consumer motivation to process information,

which leads to greater possibility of a peripheral route to persuasion.

Therefore, we expect that a humorous message in an advertisement

will work as a peripheral cue so that it is more effective for a low-

involvement rather than a high-involvement product. That is, a

consumer is less motivated to process information for a low-

involvement product and is thus more likely to form an attitude

towards the ad based on peripheral cues such as a humorous message

that we expect to function as a peripheral cue. Conversely, the

humorous advertisement is less likely to affect consumers with a high-

involvement product since consumers are more motivated to expend

cognitive processing effort for high-involvement products.

Thus the following hypotheses are suggested:

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

127

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 127

1

Footnote.

H3:

Humorous ads will be more effective in a low-involvement

product than in a high-involvement product in terms of

attitude towards the advertisement.

H4:

Humorous ads will be more effective in a low-involvement

product than in a high-involvement product in terms of

memory of advertised brand.

METHOD

Telephone survey

The data on attitude towards the ad and memory were collected via a

telephone interview and then aggregated across respondents.

Telephone interviews were conducted in Chapel Hill, North Carolina

from 1992 to 1996, and in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1997. Three

telephone interview sessions were conducted from Monday through

Wednesday evenings following the Super Bowl games. Graduate and

undergraduate students enrolled in research classes conducted

telephone surveys of local residents. Random-digit dialling was used

to include unlisted numbers. The interviewers asked for the person

who had the next birthday in the household. If a call yielded no

answer, the number was redialled at least three times before being

discarded. No respondents knew beforehand that we would be

conducting the interviews after the games, so the viewing situation

was completely natural.

Measurements

Wells and colleagues (1992) state that advertising plays several

different roles: the marketing role, the communication role, the

economic role and the societal role. However, these different roles are

all based on the function of providing information for different

purposes. Advertising imparts information that triggers consumer

needs, provides information for buyers and helps consumers make

wise decisions based on comparing product features. All purchase

decisions involve the memory of alternative brands. Therefore, a

rational, conscious brand choice decision depends on memories of the

brands. For this reason, all market or advertising research involves

some sort of memory test because memory is one of the most

128

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 128

1

Footnote.

important measurements for advertising effectiveness. Further,

Attitude towards the ad (Aad) is a frequently employed measure of

advertising effectiveness. Many studies have explored the role of Aad

as a mediator of advertising’s Attitude towards the brand (Ab) (e.g.

Mitchell & Olson 1981; Lutz et al. 1983; Lutz 1985; Edell & Burke

1987; Holbrook & Batra 1987). And, the hierarchy-of-effects para-

digm (e.g. Lavidge & Steiner 1961; Preston 1982) has also explored

Aad’s role in the purchase process.

Following the traditional measurement for advertising effectiveness,

this study also measures memory and attitude towards the

advertisement as two important dependent variables.

MEMORY

The unit of analysis in this study is each brand advertised during the

games. Memory was measured by unaided recall and aided recall.

Following an instruction, interviewers asked each respondent whether

he or she had watched the Super Bowl game, and which part. Those

who watched any part of the game were asked to list all

advertisements they remembered seeing during the game. Two coders

coded the response separately, which had been recorded verbatim

during the interviews. The two sets of results were in agreement in all

but one case (more than 99%). The unaided recall rates were then

calculated by dividing the number of respondents who recalled the

brand (Rü) by the number of respondents who watched the segment

(s) in which the brand was advertised (W¾).

After the unaided recall measure, aided recall was measured.

Respondents were given a list of brand names and asked if they

remembered seeing an advertisement for that brand during the game.

The aided recall rate was then calculated by dividing the number of

respondents who said they remembered seeing an advertisement for

each brand (Gü) by the number of respondents who watched the

segment (s) in which the brand was advertised (W¾). Although the

memory measure used here is not exactly the same as the day-after

recall (DAR) used by advertising agencies or research companies, it has

been validated in a series of previous studies (Zhao 1997; Chung &

Zhao 2000).

ATTITUDE TOWARDS THE AD

The second dependent variable used in this study was attitude towards

the ad. In experimental design, researchers have used several

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

129

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 129

1

Footnote.

dimensions to measure attitude towards the ad. For example, several

studies have used a four-item index: good–bad, like–dislike, irritating–

not irritating and uninteresting–interesting (Mitchell & Olson 1981;

Gardner 1985; Mitchell 1986). Batra and Ahtola (1991) support the

argument that attitude towards the ad is not only one-dimensional.

Instead, they found two dimensions of attitude: hedonic and

utilitarian. However, other studies have used only a one-item index

such as like–dislike or favourable–unfavourable (Burke & Edell 1986;

Edell & Burke 1987).

For this study, we focused on the degree of advertising likeness.

Our purpose was to find whether or not the perceived humour affects

advertising liking. Therefore, it was unnecessary to measure other

dimensions of attitude in this study. Attitude towards the ad was

measured by asking those respondents who remembered seeing an ad

how likeable or dislikeable they thought the ad was. Nine-point Likert

scales ranging from 1 – ‘it was one of the best’ – to 9 – ‘it was one of

the worst’ – were used. To facilitate interpretation (to obtain the same

scale with unaided and aided recall), all the scores were linearly

transformed to 0–100; here 100 represents the most likeable and 0

represents the least likeable. Those scored were then averaged across

respondents for each brand for each year.

Independent variable

DEGREE OF HUMOUR

An independent variable for this study was perceived humour in an

advertisement. Some studies have found that different types of

humour have different effects in terms of attention and memory (see

e.g. Madden 1982; Speck 1991). For instance, Speck (1991) divided

humorous messages into five different categories – comic wit,

sentimental humour, satire, sentimental comedy and full comedy – and

found that the effects of humour ranged from strongly positive for

full comedy to an essentially null effect for sentimental humour. Some

studies used five- or six-item semantic questions to measure the degree

of humour in an advertisement. However, in this study humour was

treated and measured as a unitary form since we focused on only

comic wit type of humour which is used most frequently in

advertising.

To measure the degree of perceived humour in each advertisement

aired during the Super Bowl game, undergraduate students in a large

southern university were used. Even though it has been found that

130

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 130

1

Footnote.

younger people are more likely than older people to rate advertise-

ments as humorous and that younger people’s categories of humour

are different from those of older people, students were used for

methodological convenience since it was impossible to ask each

respondent who watched the game and advertisement to rate the

degree of perceived humour in each ad.

All students watched the taped advertisements through a big screen

in a computer laboratory room and rated the degree of perceived

humour in an advertisement with a nine-point Likert scale (1 is least

humorous and 9 is most humorous). In addition, to obtain the same

scale as other variables, all degrees of perceived humour were linearly

transformed to a 0–100 scale, where 100 represents the most

humorous and 0 represents the least humorous. Those scores were

then averaged across respondents for each brand for each year.

Moderating variable

PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

For this study, the Foote, Cone and Belding (FCB) grid for 60

common products (Ratchford 1987) was used as a guideline to divide

the products advertised during the game into two different categories:

high-involvement product and low-involvement product. Two

graduate students were trained to categorise the products according to

an FCB grid for 60 common products. Each worked independently

and categorised all products advertised during the game according to

the same FCB grid for 60 common products. After finishing

categorising the products, they exchanged their work and checked

whether there were differences. In fact, almost all the products

advertised during the Super Bowl game are within the range of 60

common products or similar products to those of 60 common

products used by Ratchford (1987). Therefore, no problem exists with

regard to categorising products according to the FCB grid.

Control variables

There are several other variables that can explain significant amounts

of variance in the dependent variables, such as ad frequency. A brand

that places more ads should be more likely to influence the dependent

variables (in particular memory), and this is also more likely to

truncate the effects of humour in ads. Even though several scholars

have found that attitude towards the ad decreased with increased

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

131

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 131

1

Footnote.

advertising exposure (high frequency) (Messmer 1979; Burke & Edell

1986; Machleit & Wilson 1988), ‘mere exposure’ theory posits that

people are likely to give higher attitude ratings to the repeated exposed

stimuli. Further, higher frequency is likely to be associated with better

memory. Ad frequency is therefore controlled in the regression

analysis as a continuous variable. We also considered the variable ‘year’

as another confounding variable, since we recognised that when we

pooled the data there was a chance that differences between years

could confound the effects of humour in each ad during the Super

Bowl game. We therefore created five dummy variables, year 1993

through year 1997 (1992 serves as a comparison).

RESULTS

Data screening

The data were analysed through Systat version 9.0 and were screened

before the analysis began. The results found no severe univariate

outliers. Though descriptive statistics found the unaided recall to be

highly skewed, it is natural and reasonable to expect a highly skewed

recall score (Jin & Zhao 1999; Chung & Zhao 2000). Since regression

analysis is very sensitive to outlying cases, all the statistics for finding

outlying and influencing cases were worked out. Apart from unaided

recall, there were no significant outlying and influencing cases in terms

of leverage, studentised deleted residual, and Cook’s distance (see

Appendix for details). In terms of unaided recall, one case was identi-

fied as a highly influencing case. However, because the percentage of

Cook’s distance for this case (17.8%) belongs to moderate range (10 to

50%: Neter et al. 1999), this case was not deleted from the dataset.

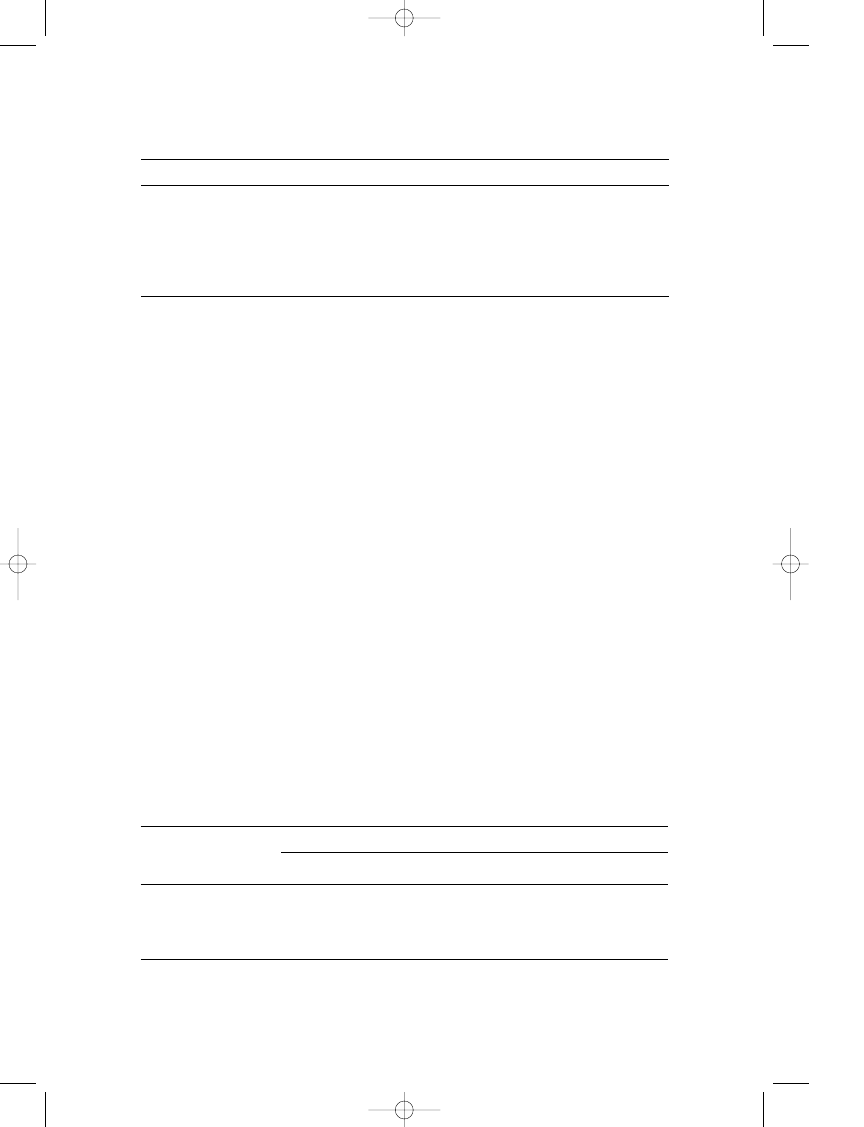

Descriptive statistics for data

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables –

memory and attitude towards the ad – independent variable,

moderating variable and control variable. The highest score for

unaided recall was 87% and the lowest was 0, and the mean was

6.54%. For aided recall, the highest brand had 78.31% and the lowest

brand had 8.61%, with a mean of 29%. The least favourable brands

had an attitude score of 35% and the most favourable brands had an

attitude score of 92%. For the dependent variable, the least humorous

132

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 132

commercial had 6 points and the most humorous commercial had 92

points in terms of degree of humour.

Hypotheses tests

HYPOTHESES 1

The first hypothesis proposes a positive relationship between a

humorous advertisement and subjects’ memory of an advertised

brand. Using degree of humour as an independent variable, simple

regression was done to check the relationship between memory and

humour. As hypothesised, humour and memory have a positive

relationship (Table 2).

Simple regression shows the significant regression model ( p <

0.001), and regression coefficients were both significant ( p < 0.001)

and positive for unaided and aided recall. Total variations that can be

explained by an independent variable were 22% for unaided recall and

26% for aided recall. Humour effect on memory was further

investigated including control variable such as frequency. In this

analysis, we also included dummy coded year variables since there is a

possibility that a different year has a different degree of humour.

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

133

TABLE 1

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTIC FOR VARIABLES

Min

Max

Mean

SD

Median

Skewness

Kurtosis

Attitude towards

the ad

35.00

91.57

58.45

8.98

57.54

0.279

0.958

Unaided recall

0.00

87.00

6.54

16.42

0.00

3.336

11.168

Aided recall

8.61

78.31

29.00

14.92

24.42

1.172

1.028

Ad frequency

1.00

7.00

1.61

1.12

1.00

Humour

6.64

91.01

50.45

21.47

47.27

0.142

–1.041

TABLE 2

HUMOUR EFFECTS ON UNAIDED AND AIDED RECALL

Unaided recall

Aided recall

Coefficient

Beta

Coefficient

Beta

Constant

–11.632

10.931***

Humour

0.360***

0.471***

0.358***

0.515***

Total R²

0.222

0.266

Adjusted R²

0.219

0.263

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 133

1

Footnote.

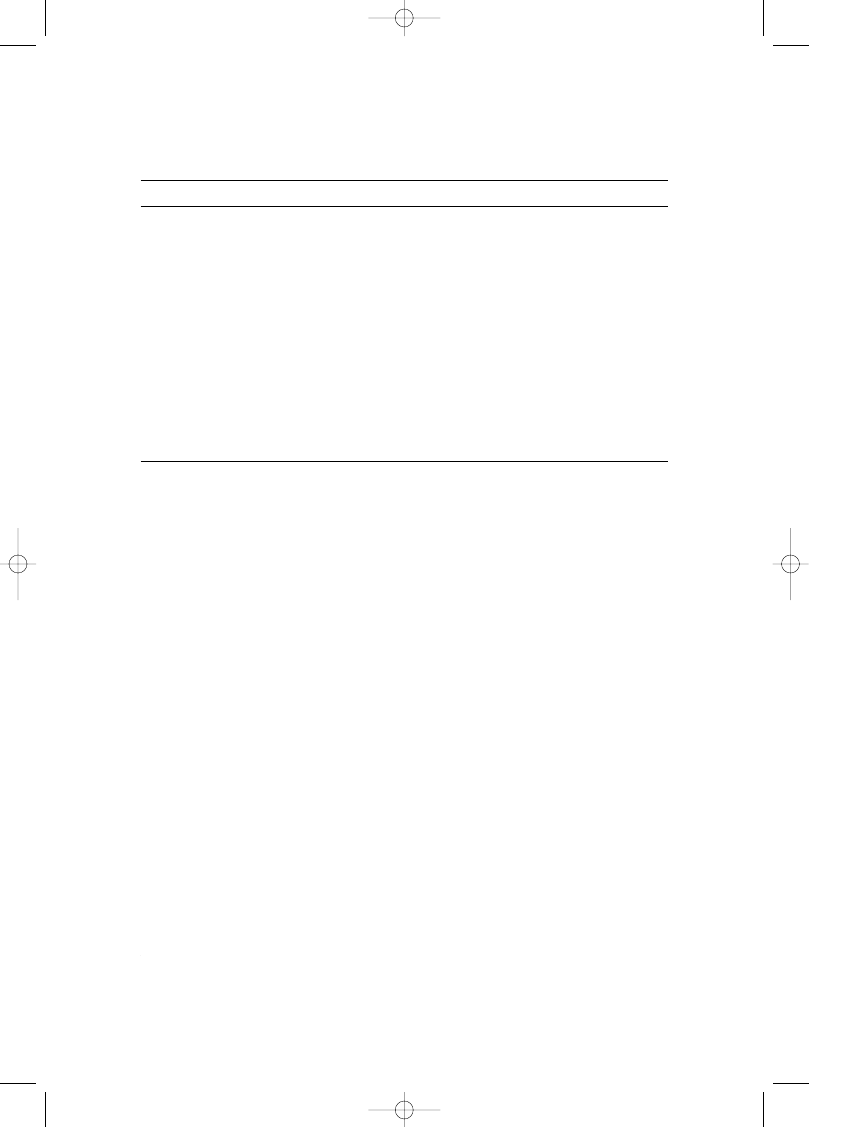

Humour including those control variables was also regressed on both

unaided and aided recall (Table 3). As expected, degree of humour in

a commercial related positively to both unaided and aided recall above

and beyond the control variables.

Year variable (1992 was used as a comparison year) shows no

significant effect on dependent variable, which means no significant

differences among different years. Also, as expected, ad frequency has

a positive relationship with memory and ad frequency itself explains

30% and 27% of total variations for unaided and aided recall, respec-

tively. Humour effect, when control variables were included, became

smaller (10% for unaided recall and 15% for aided recall), but still had

significant and positive coefficients for memory. Therefore, the first

hypothesis suggesting a positive relationship between memory and

humour was supported.

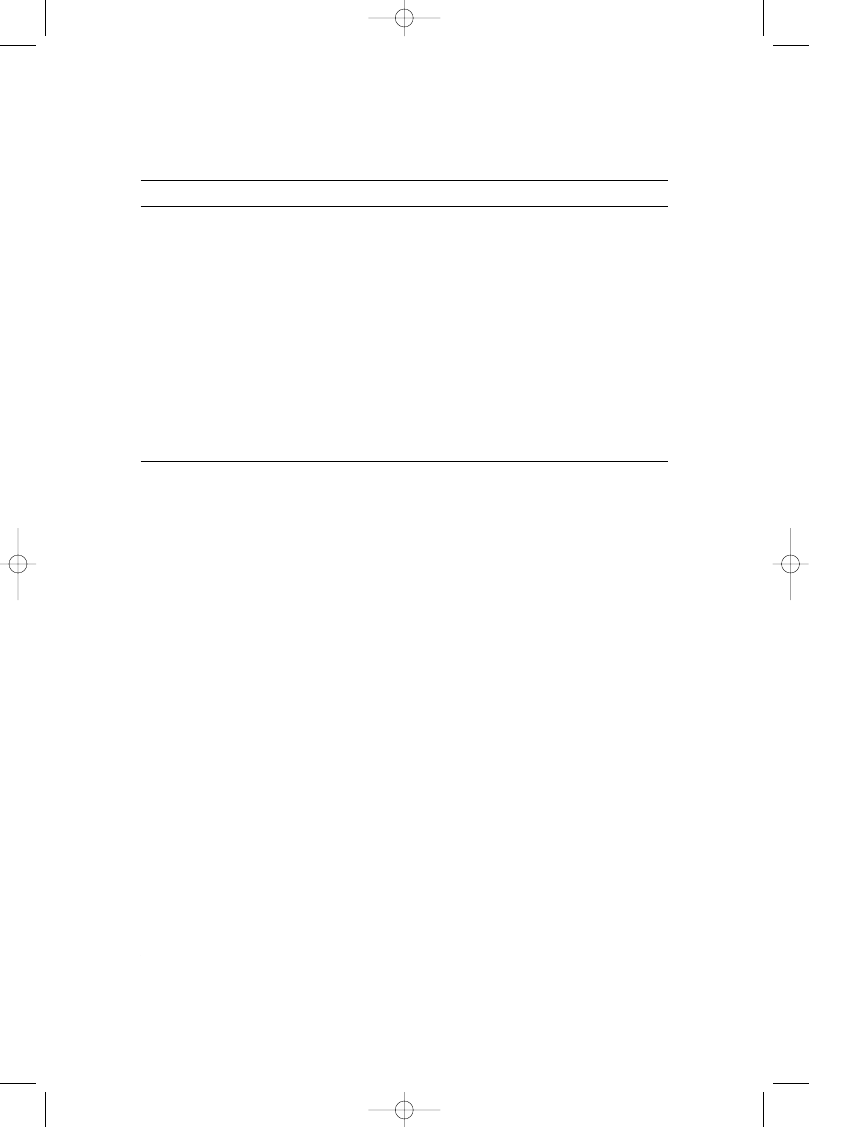

HYPOTHESES 2

The second hypothesis also proposes a positive relationship between

humour and attitude towards the advertisement. Following simple

regression of humour on attitude, multiple regression including

control variables was also run (Table 4). As shown in the table,

humour itself explains almost 9% of variation in attitude towards the

advertisement and had a significant positive coefficient for attitude

134

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

TABLE 3

HUMOUR EFFECTS ON UNAIDED AND AIDED RECALL

INCLUDING CONTROL VARIABLES

Unaided recall

Aided recall

Constant

–18.707

6.015**

1993

0.419

0.164

1.188

0.030

1994

3.742

0.089

–0.879

–0.023

1995

–0.307

–0.007

–0.002

–0.001

1996

2.348

0.050

1.253

0.030

1997

2.063

0.049

–0.557

–0.015

Frequency

6.593***

0.451***

5.415***

0.408***

Humour

0.261***

0.341***

0.280***

0.404***

R² by year

0.009

0.002

R² by frequency

0.298***

0.271***

R² by humour

0.106***

0.149***

Total R²

0.414

0.422

Adjusted R²

0.400

0.408

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 134

1

Footnote.

towards the advertisement. Unlike for memory, ad frequency explains

only 1% of variation but it was significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2,

suggesting positive relations between attitude and humorous message,

was also supported by the data.

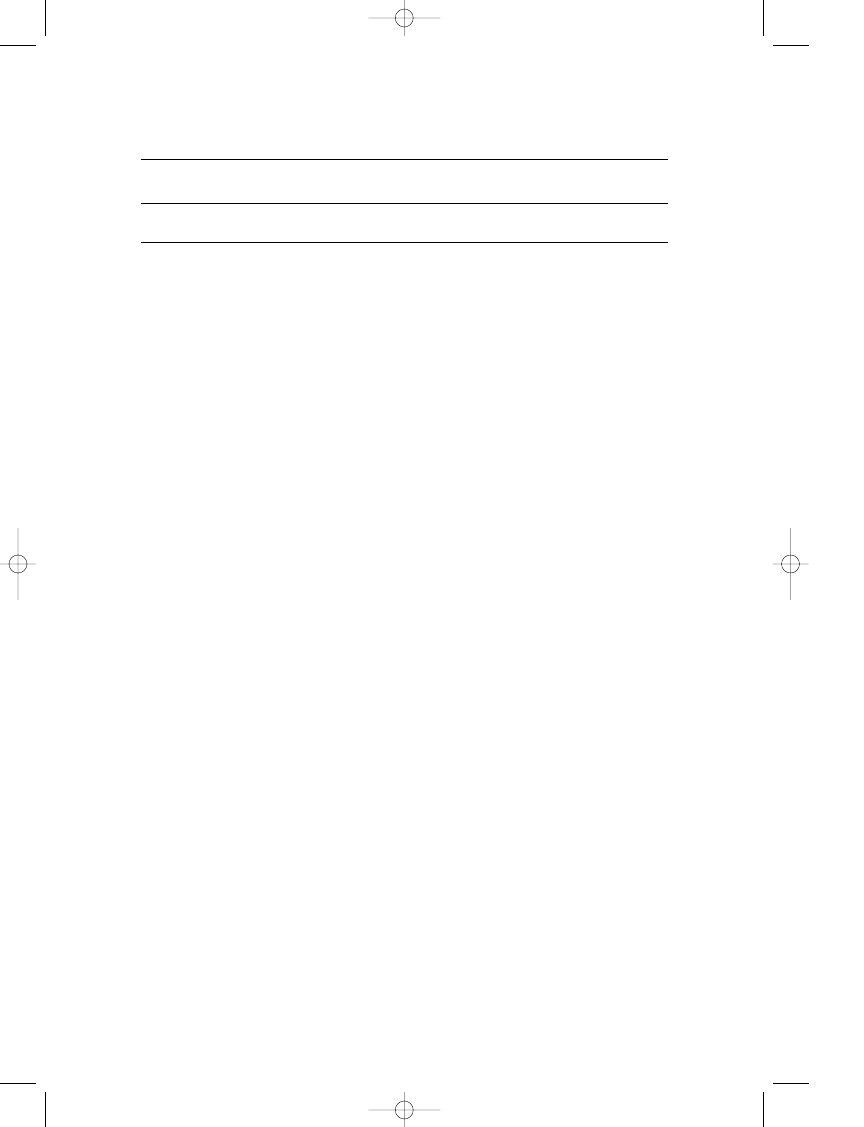

HYPOTHESES 3 AND 4

Hypotheses 3 and 4 predict the possible moderating effect by product

involvement. In this study, product involvement was not measured

directly from surveyed individuals. Instead, categorical product

involvement was used. That is, advertised products were categorised

into high-involvement and low-involvement products based on a

frequently used FCB grid. Further, to test hypotheses 3 and 4, the

amount of effect of humour on memory and attitude was compared

for high- and low-product involvement. Table 5 shows the amount of

total variations explained by humour across high- and low-product

involvement. As shown in the table, humour explains many more

variations in low-product involvement. In terms of unaided recall

there are 11.1% differences between high and low-product

involvement, and for aided recall there are almost 13% differences. For

attitude towards the ad, a humorous message explains 10% more

variations in low-involvement products.

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

135

TABLE 4

HUMOUR EFFECTS ON ATTITUDE TOWARD THE AD

INCLUDING CONTROL VARIABLES

Unaided recall

Constant

51.119***

1993

1.815

0.076

1994

–0.512

–0.022

1995

0.557

0.022

1996

–0.223

–0.009

1997

1.070

0.047

Frequency

0.267

0.033

Humour

0.128***

0.305***

R² by year

0.005

R² by frequency

0.014*

R² by humour

0.085***

Total R²

0.105

Adjusted R²

0.084

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 135

1

Footnote.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This study examined the relationship between a humorous advertise-

ment and memory and attitude, and the role of product involvement

in this relationship. Overall, strong positive relationships were found

between a humorous advertisement and memory of advertised brand

and attitude towards the advertisement. Further, it was found that

those positive relationships were much stronger within low-

involvement products than within high-involvement products.

All the research hypotheses were supported in our data. The simple

and multiple regressions for hypotheses 1 and 2 show that humour in

a television commercial does appear to have some positive effects on

unaided and aided recall and attitude towards the ad. Our findings

imply that most humorous advertisements during the 1992 to 1997

Super Bowl games did a good job in these respects.

As the advertising environment has become increasingly crowded,

humour in advertising appears to be playing a larger role in helping ads

stand out. In addition, most previous studies were done in forced

exposure environments using print ads (two researchers used

television ads in forced exposure); therefore, the subjects’ attention

levels could have been higher than in a natural television viewing

situation. The fact that we allowed attention to vary naturally in our

study may partially explain the larger effects we observed. We might

therefore infer that the ‘believers’ in humour advertisements are right.

Indeed, despite the contradicting opinions of other researchers and

advertisers, it can be a powerful tool for attention-grabbing in some

sense since research has suggested that enhanced attention leads to

more extensive processing, which in turn leads to higher memory

(Petty & Cacioppo 1985).

These findings have some practical implications for advertising

practitioners. First of all, using humorous advertisements will be more

effective in the highly cluttered environment of broadcasting, in

136

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

TABLE 5

MODERATING EFFECTS OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

Unaided recall

Aided recall

Attitude towards ad

R² by humour²

R² by humour

R² by humour

High involvement

3.5***

4.1***

2.1***

Low involvement

14.6***

16.9***

10.3***

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 136

1

Footnote.

particular television, to win higher attention from the audience and to

further increase memory of the brand and a favourable attitude

towards the advertisement. Humorous advertisements worked well for

gaining favourable attitudes from the audience, and worked well even

for increasing memory of the advertised brand. Scholars have found

that affective reaction to stimulus will increase attitude both towards

the ad and towards the brand. Even though this study did not measure

attitude towards the brand, it seems possible that humorous

advertisements can elicit a favourable attitude towards the advertise-

ment and further increase favourable attitude towards the advertised

brand (Batra & Ray 1985; Edell & Burke 1986). A second implication

is related to the role of product involvement. Findings suggest that

even though the effects of humour were statistically significant in both

high- and low-involvement products, the effects of humour in high-

involvement products were small and marginal.

As expected, humorous messages work very well in low-

involvement products. This phenomenon may be explained fully by

ELM; that is, humorous messages can serve as a peripheral cue and

work better only in a low-involvement situation. Therefore, advertising

practitioners should be very cautious about using humorous

advertisements for high-involvement or high-risk products. In some

sense they can be distracting elements for those who have high-

product involvement.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting the findings of

this study. First, this study did not consider the effects of news

coverage on brand recall and recognition. Jin and Zhao (1999) suggest

that news coverage can explain more than 70% of the variance for

brand recall and 60% of the variance for brand recognition. That is,

brand recall and recognition are influenced heavily by news coverage

of the advertised brand. In this context we should consider the

characteristics of the Super Bowl game. Because the Super Bowl is the

most visible advertising event and has tremendous media coverage,

Super Bowl advertising also draws special media attention. Therefore,

Super Bowl advertising will have wide media coverage before it is

aired; thus the higher recall and recognition score may be due in part

to the media coverage received. Second, in this study humour was

treated and measured as a unitary form. However, as Speck (1991)

pointed out, different types of humour may have a different humour-

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

137

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 137

1

Footnote.

type effect. Third, recall and recognition rates may have been affected

by ads aired either before or after the Super Bowl game. Some national

advertisers use new advertisements only for the Super Bowl, while

others rerun their famous or favourite advertisements during the

Super Bowl. Fourth, brand familiarity may be an important variable

that can influence dependent measures. More familiar brands are more

likely to be remembered. Fifth, methodological concerns may exist

because we used university students to rate the humorous advertising,

while recall and recognition and ad liking were measured among city

residents. It was found that younger people are more likely than older

people to rate advertisements as humorous and that younger people’s

categories of humour are different from those of older people. These

differences may work against our positive findings between humorous

advertisements and memory and attitude.

APPENDIX: SCREENING DATA

To see whether there are outlying and/or heavily influencing data,

leverage, studentised deleted residual, and Cook’s distance were used

to evaluate the outlying and influencing cases in the data.

First, the average leverage was calculated for all three variables.

Average leverage for unaided recall, aided recall, and attitude towards

the ad was 0.0705 (11/156), so it was considered larger in terms of

leverage if the leverage of case exceeds twice the average leverage.

Therefore, several cases were identified as having high leverage.

However, those cases had smaller leverage than 0.5 (usually considered

as a cut point; see Neter et al. 1999). So in terms of leverage no case

was identified as an outlying case.

Second, the studentised deleted residual (defined as ti = di/s{di})

was calculated to see whether there was any outlying case. Bonferroni-

corrected critical value at

α = 0.05 was 2.998. In unaided recall, 6 cases

were identified as having bigger score in terms of studentised deleted

residual, but in other variables, no case was identified as having bigger

score.

Finally, the Cook’s distance was calculated, and the corresponding

percentile to the value of Cook’s score was used to see whether there

was a heavily influencing case. As a general rule of thumb, the case

that had more than 50% of Cook percentile was used as a major

influencing case (see Neter et al. 1999). All the cases identified as

138

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 138

1

Footnote.

outlying case in terms of leverage and studentised deleted residual

were not major influencing cases in terms of Cook. All the cases have

Cook’s percentile less than 50%, the largest percentile among cases

was only 17.8% (Cook’s distance 0.202). Therefore, no one case was

deleted for final analysis.

REFERENCES

Aaker, D.A. & Myers, J.G. (1987) Advertising Management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

Ambler, T. & Burne, T. (1999) The impact of affect on memory of advertising.

Journal of Advertising Research

, 39 (March/April), pp. 25–34.

Anderson, J.R. & Bower, G.H. (1972) Recognition and retrieval process in free

recall. Psychological Review, 79 (March), pp. 97–123.

Batra, R. & Ahtola, O.T. (1991) The measurement and role of utilitarian and

hedonic attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), pp. 159–170.

Batra, R. & Ray, M. (1985) How advertising works at contact. In Psychological

Processes and Advertising Effects

, L.F. Alwitt & A.A. Mitchell (eds). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 13–44.

Belch, G.E. & Belch, M.A. (1983) An investigation of the effects of repetition on

cognitive and affective reactions to humorous and serious television

commercials. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, pp. 4–10.

Burke, M.C. & Edell, J.A. (1986) Ad reactions over time: capturing changes in the

real world. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (June), pp. 114–118.

Cantor, J. & Venus, P. (1980) The effect of humor on recall of a radio

advertisement. Journal of Broadcasting, 24(1), pp. 13–22.

Chattopadhyay, A. & Basu, K. (1990) Humor in advertising: the moderating role

of prior brand evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research, 27 (November),

pp. 466–476.

Chung, H. & Zhao, X. (2000) Does humor really matter?: Some evidence from

super bowl advertising. Paper presented in the Advertising Research Division

of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication,

Phoenix, AZ, 9–12 August.

Cohen, J.B. (1983) Involvement and you: 1000 great ideas. In Advances in Consumer

Research

, Vol. 10, ?.? Wilkie, R.P. Bagozzi & A.M. Tybout (eds). Ann Arbor, MI:

Association for Consumer Research, pp. 325–328.

Cushing, P. & Douglas-Tate, M. (1985) The effect of people/product relationship

on advertising processing. In Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects: Theory,

Research, and Applications

, L.F. Alwitt, & A.A. Mitchell (eds), Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 241–259.

Duncan, C.P. (1979) Humor in advertising: a behavioral perspective. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science

, 7(4), pp. 285–306.

Duncan, C.P. & Nelson, J.E. (1985) Effects of humor in a radio advertising

experiment. Journal of Advertising, 14(2), pp. 33–40.

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

139

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 139

1

Footnote.

Duncan, C.P., Nelson, J.E. & Frontczak, N.T. (1983) The effect of humor on

advertising comprehension. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, pp. 432–437.

Du Plessis, E. (1994) Recognition versus recall. Journal of Advertising Research, 34(3),

pp. 75–91.

Edell, J.A. & Burke, M.C. (1987) The power of feelings in understanding

advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (December), pp. 421–433.

Engel, J. & Blackwell, R.D. (1982) Consumer Behavior. New York: Dryden Press.

Fletcher, A.D. & Bowers, T.A. (1991) Fundamentals of Advertising Research (4th edn).

Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Gardner, M.P. (1985) Mood states and consumer behavior: a critical review. Journal

of Consumer Research

, 12 (December), pp. 281–300.

Gelb, B.D. & Pickett, C.M. (1983) Attitude-toward-the-ad: links to humor and to

advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 12(2), pp. 34–42.

Gelb, B.D. & Zinkhan, G.M. (1986) Humor and advertising effectiveness after

repeated exposures to a radio commercial. Journal of Advertising, 15(2),

pp. 15–20.

Greenwald, A.G. & Leavitt, C. (1984) Audience involvement in advertising: four

levels. Journal of Consumer Research, 11 (June), pp. 581–592.

Haley, R.I. & Baldinger, A.L. (1991) The ARF copy research validity project.

Journal of Advertising Research

, 31(2), pp. 11–32.

Helson, H. (1959) Adaptation-level theory. In Psychology: A Study of a Science,

I. Sensory Perception and Physiological Formulations

. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Holbrook, M.B. & Batra, R. (1987) Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of

consumer response to advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (December),

pp. 404–420.

Holbrook, M.B. & O’Shaughnessy, J. (1984) The role of emotion in advertising.

Psychology and Marketing

, 1 (summer), pp. 45–64.

Hollis, N.S. (1995) Like it or not, liking is not enough. Journal of Advertising

Research

, 35(5), pp. 7–16.

Houston, M.J. & Rothschild, M.L. (1978) Conceptual and methodological

perspectives on involvement. In 1978 Educators’ Proceedings, S.C. Jain (ed.).

Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, pp. 184–187.

Jin, H. & Zhao, X. (1999) Effects of media coverage on advertised brand recall

and recognition. In Proceedings of the 1999 Convention of the American Academy of

Advertising

, M.S. Roberts (ed.), pp. 54–61.

Kapferer, J. & Laurent, G. (1985) Consumers’ involvement profile: new empirical

results. In Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 12, E.C. Hirschman & M.B.

Holbrook (eds). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 290–295.

Kintsch, W. (1970) Models for free recall and recognition. In Models of Human

Memory

, D.A. Norman (ed.). New York: Academy Press, pp. 333–373.

Krugman, H.E. (1965) The impact of television advertising: learning without

involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29, pp. 349–394.

Krugman, H.E. (1977) Memory without recall, exposure without perception.

Journal of Advertising Research

, 17(4), pp. 7–12

Krugman, H.E. (1986) Low recall and high recognition of advertising. Journal of

Advertising Research

, 26(2), pp. 79–86.

140

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 140

1

Footnote.

Lammers, H.B., Leibowitz, L., Seymour, G.E. & Hennessey, J.E. (1983) Humor

and cognitive responses to advertising stimuli: a trace consolidation approach.

Journal of Business Research

, 11, pp. 173–185.

Lavidge, R.J. & Steiner, G.A. (1961) A model for predictive measurements of

advertising effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 25 (October), pp. 59–62.

Lutz, R.J. (1985) Affective and cognitive antecedents of attitude toward the ad: a

conceptual framework. In Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects: Theory,

Research, and Applications

, L.F. Alwitt, & A.A. Mitchell (eds). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 45–56.

Lutz, R.J., MacKenzie, S.B. & Belch, G.E. (1983) Attitude toward the ad as a

mediator of advertising effectiveness: determinants and consequences. In

Advances in Consumer Research

, Vol. 10, R.P. Bagozzi & A.M. Tybout (eds). Ann

Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 532–539.

MacKenzie, S.B. & Lutz, R.J. (1989) An empirical examination of the structural

antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context.

Journal of Marketing

, 53 (April), pp. 48–56.

MacKenzie, S.B., Lutz, R.J. & Belch, G.E. (1986) The role of attitude toward the

ad as mediator of advertising effectiveness: a test of competing explanations.

Journal of Marketing Research

, 23 (May), pp. 28–35.

Machleit, K.A. & Wilson, R.D. (1988) Emotional feelings and attitude toward the

advertisement: the roles of brand familiarity and repetition. Journal of

Advertising

, 17(3), pp. 27–35.

Madden, T.J. & Ajzen, I. (1991) Affective cues in persuasion: an assessment of

causal mediation. Marketing Letters, 2(4), pp. 359–366.

Madden, T.J. & Weinberger, M.G. (1982) The effects of humor on attention in

magazine advertising. Journal of Advertising, 11(3), pp. 8–14.

Madden, T.J. & Weinberger, M.G. (1984) Humor in advertising: a practitioner view.

Journal of Advertising Research

, 24(4), pp. 23–29.

Markiewicz, D. (1974) Effects of humor on persuasion. Sociometry, 37(3),

pp. 407–422.

Messmer, D.J. (1979) Repetition and attitudinal discrepancy effects on the affective

response to television advertising. Journal of Business Research, 7(1), pp. 75–93.

Mitchell, A.A. (1979) Involvement: a potentially important mediator of consumer

behavior. In Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 6, W.H. Wilkie (ed.). Ann Arbor,

MI: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 20–24.

Mitchell, A.A. (1986) The effect of verbal and visual components of

advertisements on brand attitudes and attitude toward the ad. Journal of

Consumer Research

, 13 (June), 12–24.

Mitchell, A.A. & Olson, J.C. (1981) Are product attribute beliefs the only mediator

of advertising effects on brand attitude. Journal of Consumer Research, 18

(August), pp. 318–332.

Murphy, J.H., Cunningham, I.C. & Wilcox, G.B. (1979) The impact of program

environment on recall of humorous television commercials. Journal of

Advertising Research

, 18(2), pp. 17–21.

Neter, J., Kutner, M.H., Nachtsheim, C.J. & Wasserman, W. (1999) Applied Linear

Statistical Models

(3rd edn). New York: WCB/McGraw-Hill.

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

141

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 141

1

Footnote.

Nord, W.R. & Peter, J.P. (1980) A behavioral modification perspective on

marketing. Journal of Marketing, 44 (spring), pp. 36–47.

Park, C.W. & Mittal, B. (1985) A theory of involvement in consumer behavior:

problems and issues. In Research in Consumer Behavior, Vol. 1, J.N. Sheth (ed.).

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Park, C.W. & Young, S.M. (1986) Consumer response to television commercials:

the impact of involvement and background music on brand attitude

formation. Journal of Marketing Research, 23 (February), pp. 11–24.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1981a) Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary

Approaches

. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1981b) Issue involvement as moderator of the

effects on attitude of advertising content and context. In Advances in Consumer

Research

, Vol. 8, K.B. Monroe (ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer

Research, pp. 20–24.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1985) Central and peripheral routes to persuasion:

the role of message repetition. In Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects,

L.F. Alwitt & A.A. Mitchell (eds). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

pp. 91–111.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986a) Communication and Persuasion: Central and

Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change

. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986b) The elaboration likelihood model of

persuasion. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 19, L. Berkowitz

(ed.). New York: Academic Press, pp. 123–205.

Petty, R.E., Cacioppo, J.T. & Goldman, R. (1981) Personal involvement as a

determinant of argument-based persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology

, 41, pp. 847–855.

Petty, R.E., Cacioppo, J.T. & Schuman, D. (1983) Central and peripheral routes to

advertising effectiveness: the moderating role of involvement. Journal of

Consumer Research

, 10 (September), pp. 135–146.

Phillips, K. (1968) When a funny commercial is good, it’s great! Broadcasting,

74

(13), p. 26.

Preston, I. (1982) The association model of the advertising communication

process. Journal of Advertising, 11(2), pp. 3–15.

Ratchford, B.T. (1987) New insights about the FCB grid. Journal of Advertising

Research

, 27(4), pp. 24–38.

Ray, M.L. & Batra, R. (1983) Emotion and persuasion in advertising: what we do

and don’t know about affect. In Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 10,

R.P. Bagozzi, & A.M. Tybout (eds). Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer

Research, pp. 543–548.

Rothschild, M.L. (1979) Advertising strategies for high and low involvement

situations. In Attitude Research Plays for High Stakes, J. Maloney, & B. Silverman

(eds). Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, pp. 74–93.

Salmon, C.T. (1986) Perspectives of involvement in consumer and communication

research. In Progress in Communication Sciences, Vol. 7, B. Dervin & M.J. Voight

(eds). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing, pp. 243–268.

Shimp, T.A. (1981) Attitude toward the ad as a mediator of consumer brand

choice. Journal of Advertising, 10(2), pp. 9–15.

142

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 142

1

Footnote.

Speck, P.S. (1991) The humorous message taxonomy: a framework for the study of

humorous ads. In Current Issues & Research and Advertising, J.H. Leigh & C.R.

Martin (eds), The Division of Research Michigan Business School, The

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, pp. 1–44.

Spotts, H.E., Weinberger, M.G. & Parsons, A.L. (1997) Assessing the use and

impact of humor on advertising effectiveness: a contingency approach. Journal

of Advertising

, 26(3), pp. 17–32.

Sternthal, B. & Craig, C.S. (1973) Humor in advertising. Journal of Marketing, 37

(October), pp. 12–18.

Sutherland, J.C. & Middleton, L.A. (1983) The effect of humor on advertising

credibility and recall. In Proceedings of the 1983 Convention of the American Academy

of Advertising

, D.W. Jugenheimer (ed.), pp. 17–21.

Taylor, M.B. & Joseph, W.J. (1984) Measuring consumer involvement in products.

Psychology and Marketing

, 1(2), pp. 65–77.

Tyebjee, T.T. (1979) Response time, conflict, and involvement in brand choice.

Journal of Consumer Research

, 6, pp. 259–304.

Walker, D. & Dubitsky, T.M. (1994) Why liking matters. Journal of Advertising

Research

, 34(3), pp. 9–18.

Weinberger, M.G. (1992) The impact of humor in advertising: a review. Journal of

Advertising

, 21(4), pp. 35–59.

Weinberger, M.G. & Spotts, H.E. (1989) Humor in U.S. versus U.K.

TV advertising. Journal of Advertising, 18(2), pp. 39–44.

Wells, W.D., Burnet, J. & Moriarty, S.E. (1992) Advertising: Principles and Practice.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Wright, P. (1973) The cognitive processes mediating acceptance of advertising.

Journal of Marketing Research

, 10 (February), pp. 53–62.

Zaichkowsky, J.L. (1985) Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer

Research

, 12 (December), pp. 341–352.

Zhang, Y. & Zinkhan, G.M. (1991) Humor in television advertising: the effects of

repetition and social setting. Advances in Consumer Research, 18, pp. 813–818.

Zhang, Y. (1996) Responses to humorous advertising: the moderating effect of

need for cognition. Journal of Advertising, 25(1), pp. 15–32.

Zhao, X. (1997) Clutter and serial order redefined and retested. Journal of

Advertising Research

, 37 (September/October), pp. 57–73.

Zinkhan, G.M. & Gelb, B.D. (1987) Humor and advertising effectiveness

reexamined. Journal of Advertising, 16(1), pp. 66–68.

Zinkhan, G.M. & Zinkhan, F.C. (1985) Response profiles and choice behavior: an

application to financial services advertising. Journal of Advertising, 14(3),

pp. 39–66.

MODERATING ROLE OF PRODUCT INVOLVEMENT

143

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 143

1

Footnote.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Hwiman Chung

received his Ph.D. from the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has worked as an ad agency account

executive, handling diverse clients ranging from a cosmetic company

to an airline. His major interest is in consumer behaviour in the new

media environment, with a particular focus on structure and design

issues in www advertising.

Xinshu Zhao

received his Ph.D. from University of Wisconsin,

Madison. His areas of research interest are Super Bowl advertising,

public opinion, and consumer behaviour in the new media

environment. His research papers have appeared in many industry

journals.

144

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVERTISING, 2003, 22(1)

Chung.qxd 28/01/03 13:45 Page 144

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Caffeine effect on mortality and oviposition in successive of Aedes aegypti

Norris, C E i Colman, A M (1993) Context effects on memory for televiosion advertisements Social Bah

[30]Dietary flavonoids effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism

[30]Dietary flavonoids effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism

53 755 765 Effect of Microstructural Homogenity on Mechanical and Thermal Fatique

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Effects of the Great?pression on the U S and the World

Heavy metal toxicity,effect on plant growth and metal uptake

Possible Effects of Strategy Instruction on L1 and L2 Reading

33 437 452 Primary Carbides in Spincast HSS for Hot Rolls and Effect on Oxidation

5 The importance of memory and personality on students' success

Effect of heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of cold rolled C Mn Si TRIP

48 671 684 Cryogenic Treatment and it's Effect on Tool Steel

Genetic and environmental effects on polyphenols

53 755 765 Effect of Microstructural Homogenity on Mechanical and Thermal Fatique

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Effect of thermal oxidation on corrosion and corrosion

więcej podobnych podstron