Ethnic Migration in Central

and Eastern Europe: Its

Historical Background and

Contemporary Flows

Roel Jennissen*

Research and Documentation Centre, Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice

Abstract

This article aims to describe the historical background of international ethnic

migration in Central and Eastern Europe. The rise and fall of the Habsburg Empire

in Central Europe and the Ottoman Empire in Southeastern Europe has been the

underlying cause of many ethnic migration flows in Central and Eastern Europe in

the post-communist era. Moreover, the German Ostkolonisation, border changes

after the two World Wars, and interstate migration in the former Soviet Union

caused a large pool of potential ethnic migrants. In addition to the description of

this historical background, this article contains a description of important contem-

porary ethnic migration flows that originate from the aforementioned historical

developments, and a discussion of future developments of ethnic migration in

Central and Eastern Europe.

I. Introduction

International migration figures were traditionally low in communist Europe from

the 1960s.

1

Since the second half of the 1980s, however, international migration

figures in the former communist countries (the countries in transition) significantly

increased (Okólski 1998). Given the turbulent history of Eastern Europe, the

potential number of migrants in Eastern Europe was very large (Van de Kaa 1996).

After the collapse of communism, ethnic minorities in Eastern Europe were able

(or forced) to migrate to their country of origin, and as a result ethnic migration has

* Roel Jennissen is researcher at the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) of the

Dutch Ministry of Security and Justice. He also worked at the Netherlands Interdisciplinary

Demographic Institute (NIDI), where he conducted most of the research for this article. He

obtained a Ph.D. in demography from the University of Groningen on the basis of the book

Macro-Economic Determinants of International Migration in Europe (2004). Currently, his

main research interests are the integration of non-Western minorities in the Netherlands,

international migration, and historical demography.

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

252

once again become significant. Both ethnic migration within Central and Eastern

Europe and ethnic migration from Central and Eastern Europe to Germany (and to

a lesser extent to Finland, Greece, and Israel) reached a high level in the 1990s. The

aim of this article is to describe the historical developments and events that

eventually ended in the ethnic mosaic of Central and Eastern Europe when

communism fell. Moreover, this article describes important contemporary migra-

tion flows that originate from these historical developments. This article also deals

with the contemporary factors that have had an impact on these migration flows,

which are often labelled ‘ethnic migration’.

In Central and Eastern Europe, many population groups have lived outside their

own nation-states – if they have had one at all. Three specific historical develop-

ments were largely responsible for this situation. Firstly, the rise and fall of two

large multi-ethnic states, i.e. the Habsburg Empire and the Ottoman Empire,

played an important part. Secondly, many ethnic Germans have lived outside the

united Germany because of ancient migration to the east and border changes after

the World Wars. Thirdly, many people have lived outside their home country in the

former Soviet Union because of interstate migration within the Soviet Union

before its disintegration. The following three sections describe these historical

developments and examples of important ethnic migration flows that have origi-

nated from these developments. The topic of the fifth section is future develop-

ments of ethnic migration in Central and Eastern Europe. This article ends with

some concluding remarks.

II. The Habsburg and the Ottoman Empires

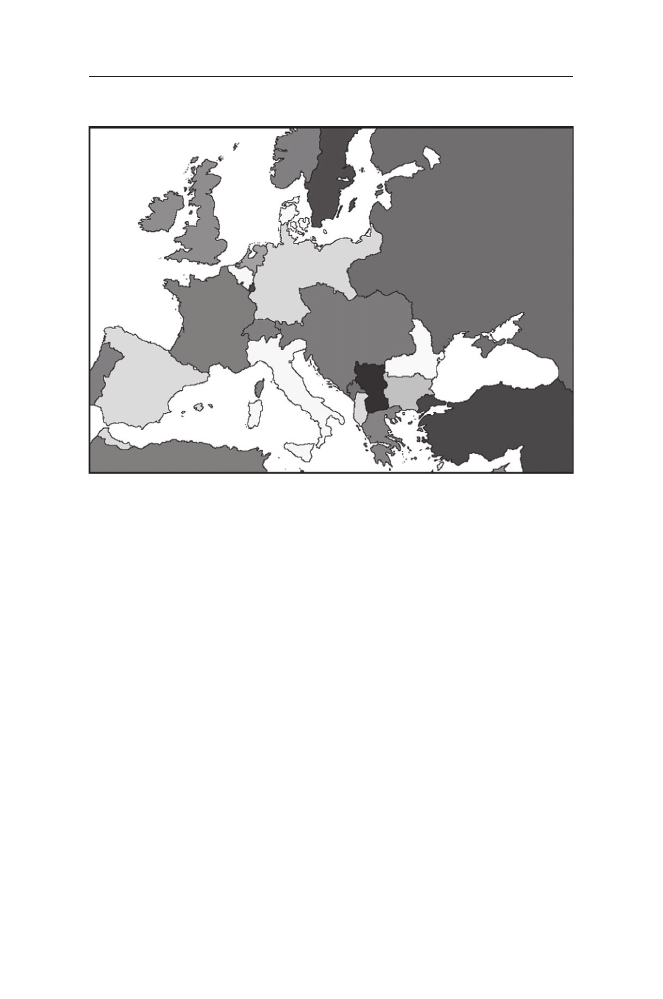

At the dawn of the First World War the Habsburg Empire (Austria-Hungary)

comprised

contemporary

Austria,

Hungary,

Slovenia,

Croatia,

Bosnia-

Herzegovina, the contemporary Czech and Slovak Republics, Vojvodina, Transyl-

vania, Trentino-Alto Adige, and parts of contemporary southern Poland and

western Ukraine (see Figure 1). In contrast to the Western European states, the

Habsburg Empire was a multiethnic state, in which people of different ethnic

descent (Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians, Roma-

nians, Poles, Ruthenians, Slovenes, and Italians) lived together (Sked 1989).

The disintegration of the Habsburg Empire, which occurred after the First World

War, appeared to be the root cause of many small ethnic migration flows. Hungary,

for instance, lost large parts of its historical territory, as a consequence of the treaty

of Trianon, which came into effect in 1920. Hence, many ethnic Hungarians have

lived in Romania (Transylvania), Czechoslovakia (southern Slovakia), and Yugo-

slavia (Vojvodina) (Courbage 1998). Many ethnic Hungarians harboured the wish

to migrate to Hungary, and the end of communism offered the chance for many of

them to do so. Yugoslavia was a multiethnic state, as it was established out of the

southern Slavic provinces of Austria-Hungary, Serbia,

2

and Montenegro. In turn,

after the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, many people from ethnic

minorities were forced to migrate out of the area where they and their ancestors

had lived for centuries. Often they migrated to the successor state that was

inhabited by a majority of the people of their own ethnic group.

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

253

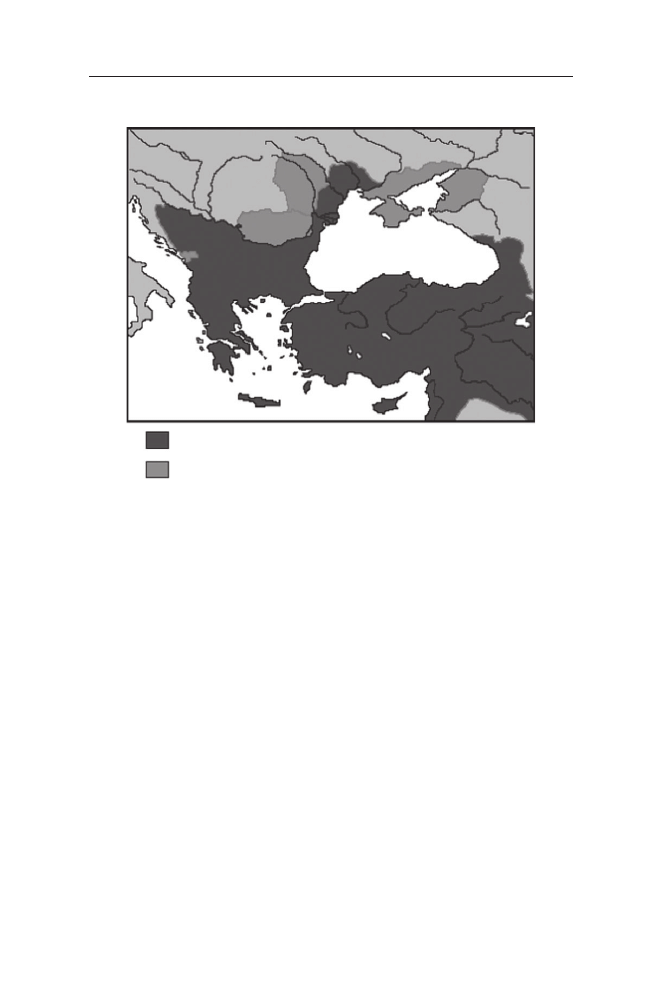

Similar to the Habsburg Empire, the Ottoman Empire was also a multiethnic

state. It dominated (parts of) the contemporary Southeastern European states of

Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, the Former Yugosla-

vian Republic of Macedonia (FYROM), Kosovo, Albania, and Romania for more

than 200 years (Quataert 2000; see also Figure 2).

Examples of ethnic migration flows in the post-communist era that can be

attributed to the multiethnic character of the Ottoman Empire are the Turks, who

emigrated from Bulgaria, and the Greeks, who emigrated from Albania. The

Ottoman domination of Southeastern Europe brought Islam to this region.

However, the sultans also tolerated the continued existence of the various forms of

Christianity to which the original population adhered (Kinross 1977). This reli-

gious tolerance often originated out of necessity and was often accompanied with

several discriminating measures towards non-Muslims. Albanians, Bosniaks, and

the Pomaks in Bulgaria are examples of population groups who voluntarily

3

converted to Islam during Ottoman rule. The different coexisting religions in the

former Yugoslavia led to a sense of nationhood among Orthodox Serbs, Catholic

Croats, and Bosnian Muslims, although these groups have a common Slavic

ancestry (Ingrao 1996). Conflicts between these groups caused large ethnic migra-

tion flows in the post-communist era.

The changing frontier between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires and other

border changes were also the root cause of many ethnic migration flows in the

post-communist era. Examples include the Serbs who emigrated from Krajina

(Croatia), the Albanians who emigrated from Kosovo (Serbia and Montenegro),

Figure 1. Europe in 1914

Dual Kingdom of

Austria-Hungary

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

254

and the Hungarians who emigrated from Transylvania (Romania). According to

Ingrao (1996:3), the Habsburgs resettled 600,000 Serbs near their southern mili-

tary border (the so-called Vojne Krajina). Many Serbs had to flee from this area

after the Croatian army conquered this area in 1995. Ingrao also states that the

Ottomans replaced Serbs, who fled en masse from Kosovo at the end of the

fourteenth century, with loyal Albanian Muslims. Many Albanians were forced to

flee from Kosovo in 1999. Hungarians, who settled in Transylvania at the end of the

ninth century, claim that Slavonic tribes were the only inhabitants of the Danube

basin when they conquered it. However, according to Romanian historiography,

Romanians, who are seen as Romanised Dacians, had lived in Transylvania for

centuries before the Hungarians arrived (Deletant 1992). Hence, both Hungarians

and Romanians consider Transylvania as part of their historical homeland. Many

Romanians (Vlachs) migrated to Transylvania after the Ottomans were driven

away from this area, because of heavy burdens on Romanian peasants in Wallachia

and Moldavia, which were still under Ottoman rule. Eventually, Romanians con-

stituted the majority in Transylvania in the eighteenth century (Péter 1992).

Transylvania became Romanian territory when the treaty of Trianon was signed in

1920. About 1.6 million ethnic Hungarians lived in Transylvania in 1992. The

Hungarian population in Romania can be divided into two groups: Magyars and

Szekels (Cushing 1992). The latter, who live in the southeastern part of Transyl-

vania, developed their own social structure and often consider themselves as

separate from the other Hungarians. Many ethnic Hungarians emigrated from

Transylvania after the fall of communism.

Figure 2. The northern part of the Ottoman Empire in 1740

Bosnia

Wallachia

Moldavia

Ottoman Empire

Vassal states

Anatolia

Black Sea

Rumelia

Transylvania

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

255

III. Ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe

Overpopulation in the German states and labour shortages in several Central and

Eastern European areas induced many Germans to migrate eastwards. This

so-called Ostkolonisation started in the twelfth century and continued up to the

nineteenth century. Large groups of Germans settled in the Baltic area, the Sudeten

area, Bohemia-Moravia, Poland, and Hungary in the first three centuries of the

Ostkolonisation. Wars and turmoil in Central and Eastern Europe caused a decline

in the number of Germans who migrated eastwards in the fifteenth century.

Subsequently, the Turkish expansion in Southeastern Europe virtually ended the

southeastern migration until the Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683. After withstand-

ing this siege, the Habsburg emperors sponsored Germans to settle near the

frontier as a buffer against the Ottomans. In this period many Germans migrated to

Transylvania,

4

Vojvodina, and Slavonia. During the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries, Russia conquered expansive yet sparsely populated fertile territories

around the Black and Caspian Seas. From 1763, Catherine II and her successors

encouraged German farmers to inhabit these areas. Hence, many ethnic Germans

lived in the Volga steppes, the Ukraine, the Crimea, and in the Caucasian provinces

(Schoenberg 1970). During the 1930s, many ethnic Germans were deported to

Siberia and Central Asia as part of the collectivisation of agriculture. The Nazi

attack on the Soviet Union provided Stalin a charter to abolish the Autonomous

Socialistic Republic of the Volga Germans and to deport ethnic Germans, who

were considered as Hitler’s fifth column, to the Asiatic part of the Soviet Union

(Long 1988; Sinner 2000). After the Second World War, many ethnic Germans

from Romania were deported to labour camps in the Soviet Union (Groenendijk

1997).

In addition to the 8.3 million Germans who lived outside Germany because of

historical migration to the east, millions of Germans lived outside the territory of

the contemporary reunited Germany because of border changes after the First and

Second World Wars. Germany lost large parts of the provinces of West Prussia and

Posen and the eastern part of Upper Silesia to Poland, the Memel region to

Lithuania, and the Hultschin region (an area in the south of Upper Silesia) to

Czechoslovakia

5

as stipulated by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Moreover, the

city of Danzig became a ‘free city’ governed by the League of Nations (Schoen-

berg 1970; Tooley 1997). Germany reoccupied these territories in the first years of

the Second World War, but lost them again to the advancing Red Army at the end

of this war. The loss of the Second World War had even more far-reaching

territorial consequences for the eastern part of Germany: the provinces of East

Pomerania, East Brandenburg, Silesia, and the southern part of East Prussia were

allocated to Poland (see Figure 5), while the northern part of East Prussia was

placed under Soviet administration. About 9.5 million Germans lived in the

German provinces that lay east of the Oder-Neisse line

6

at the start of the Second

World War. Many Germans from the lost eastern provinces and ethnic Germans

from central and eastern European states fled or were expelled to the four military

occupation zones after the war. Almost two million ethnic Germans and Germans

from the eastern provinces were killed during the last months of the war. In 1950,

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

256

about 11 million German expellees lived in the two German states (about 8 million

in West Germany and about 3 million in East Germany). Furthermore, Austria and

other Western countries received about 500,000 German expellees. At this time it

was estimated that about 4.2 million ethnic Germans still lived in other central and

eastern European states: 1.7 million in Poland, 1.4 million in the Soviet Union,

300,000 in Czechoslovakia, and 750,000 in southeastern European countries

(Fleischer and Proebsting 1989; Münz and Ohliger 2001; Schoenberg 1970).

Table 1 presents the number of Aussiedler in the period 1950–2005 and their

country of origin. Aussiedler are ethnic Germans who did not use to live in one of

the two German states but in other central or eastern European countries and that

migrated to the Federal Republic of Germany after the Second World War.

7

In the period 1950–1984, more than 1.25 million Aussiedler arrived in West

Germany. In this period the most represented country of origin was Poland

(59.5%), followed by Romania (13.0%), Czechoslovakia (7.6%), the Soviet Union

(7.5%), and Yugoslavia (6.8%). Ethnic migration to East Germany was very small

after 1950, because the East German authorities did not want to upset the relation-

ships with the other East Bloc states (Bade 2000). Despite the more than 1.25

million ethnic Germans who migrated to West Germany in the period 1950–1984,

the number of ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe and in Central Asia

was still very large in 1985.

Most Aussiedler came from the (former) Soviet Union (73.3%), followed by

Poland (22.7%), and Romania (8.7%) in the period 1985–2005. The number of

Aussiedler from the remaining countries was quite small, as the number of ethnic

Germans in these countries had already significantly decreased in the former

decades. For instance, the borders of Yugoslavia were relatively open after the

Second World War. Therefore, the number of ethnic Germans in Yugoslavia was

already quite small after the 1950s. The number of ethnic Germans in Czechoslo-

vakia was also already small towards the end of the 1960s, since large numbers of

ethnic Germans emigrated from Czechoslovakia in the 1960s (Fleischer and

Proebsting 1989). Many of them emigrated at the end of the 1960s in the years

around the ‘Prague Spring’. The figures in Table 1 show that the number of

Aussiedler from the countries which had relatively closed borders (Poland,

Romania, and the Soviet Union) was much larger in the 1970s compared to the

1960s. The Ostpolitik of the Brandt/Scheel Administration, which was inaugurated

in October 1969, improved the relationship between West Germany and the

communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. This enabled more ethnic

Germans who lived in this area to emigrate to West Germany (Banchoff 1999;

Bucher 2000). West Germany often granted credit to Poland, Romania, and the

Soviet Union in exchange for the exit visas of ethnic Germans. Poland received, for

instance, a credit of 2.3 billion Deutschmarks for the promise that 125,000 people

of German origin were allowed to leave the country within a year (Mak 2004).

Another remarkable fact that emerges from Table 1 is that the number of

Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union is considerably larger than the estimated

number of ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union in 1950 (2.3 million versus 1.4

million). Moreover, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans still lived in the

former Soviet Union in the middle of the first decade of the new millennium.

8

A

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

257

T

a

b

le

1

.

The

n

umber

of

A

ussiedler

b

y

country

of

origin,

1950–2005

1950–59

1960–69

1970–79

1980–89

1990–99

2000–05

Total

(former)

Soviet

Union

13,580

8,571

56,585

176,565

1,630,041

448,992

2,334,334

Poland

292,183

110,618

202,712

632,803

204,069

2,462

1,444,847

Romania

3,454

16,294

71,417

151,161

186,340

1,435

430,101

(former)

Czechoslovakia

20,361

55,733

12,775

12,727

3,437

51

105,084

(former)

Yugoslavia

57,512

21,108

6,205

3,282

2,234

37

90,378

Remaining

countries

51,132

9,192

6,172

7,549

3,055

38

77,138

Total

438,222

221,516

355,866

984,087

2,029,176

453,015

4,481,882

Sources:

Bundesambt

für

die

Anerk

ennung

ausländischer

Flüchtlinge

(2002)

and

Bundesambt

für

Mig

ration

und

Flüchtlinge

(2006).

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

258

part of the natural growth of the German population in the former Soviet Union

may explain the aforementioned discrepancy. Moreover, the population able to

apply for Aussiedler status had increased because of mixed marriages. The share of

mixed marriages was very high among the German population in the Soviet Union.

According to Dietz (1995), nearly half of the married ethnic Germans lived in

mixed marriages in the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan at the end of the 1970s.

However, there are also indications that many Aussiedler who arrived after the

1980s had only weak cultural ties to the German motherland (see, e.g., Dietz

1999). Thus, economic motives probably contributed considerably to this migra-

tion flow, which is labelled ‘ethnic migration’, after the 1980s.

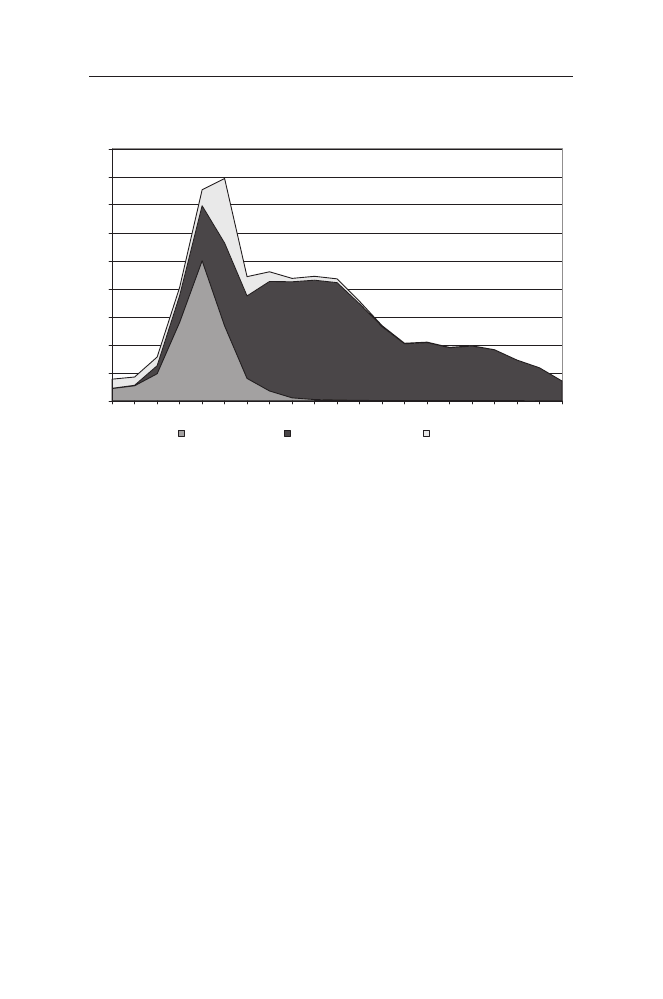

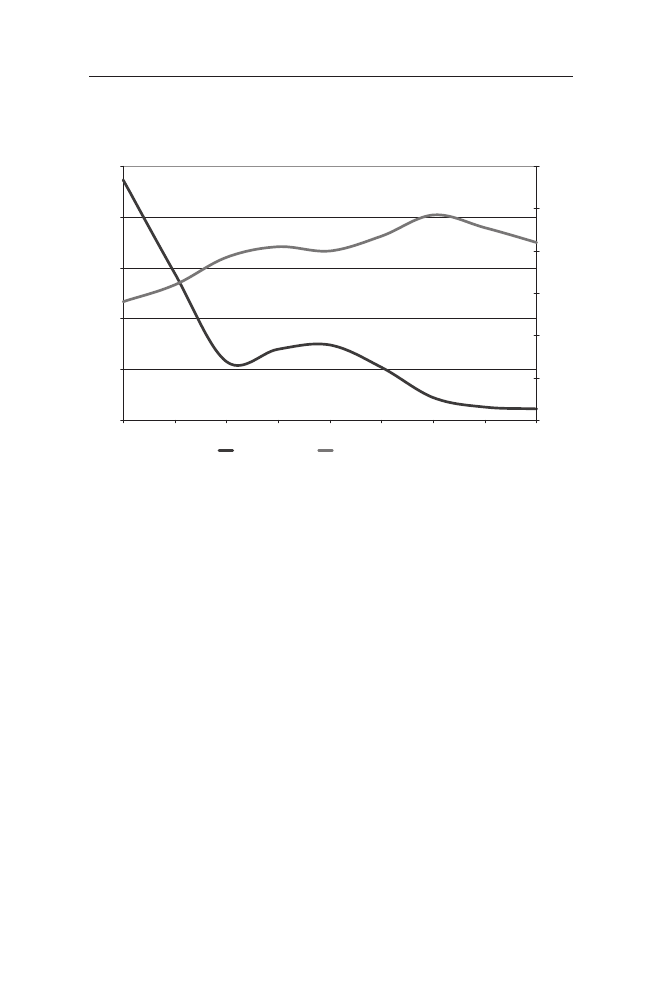

As is shown in Figure 3, the number of Aussiedler from the (former) Soviet

Union exceeds the number of Aussiedler from Poland since 1990. Before 1990 the

number of Aussiedler from Poland, which peaked in 1989, was by far the largest.

Figure 3 also shows a large number of Aussiedler from countries other than Poland

and the Soviet Union in 1990. About 111,000 ethnic Germans from Romania

migrated to Germany in this year after the fall of the Ceaus¸escu regime (Bunde-

sambt für die Anerkennung ausländischer Flüchtlinge 2002). This was more than

half of the total ethnic German population in Romania in 1990. Since July 1990,

Aussiedler intending to migrate to Germany had to complete a fifty-page applica-

tion form in German in their country of residence (Heinelt and Lohmann 1992,

cited in Groenendijk 1997; Thränhardt 1995, cited in Groenendijk 1997). This

might be a reason why the number of Aussiedler decreased after 1990. Since

December 1992, Aussiedler had to prove that their wish to migrate to Germany was

based on ill treatment related to the Second World War, with the exception of those

Figure 3. The number of Aussiedler (in thousands) from Poland, the

(former) Soviet Union, and other countries, 1985–2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

Poland

(former) USSR

other countries

Sources: Bundesambt für die Anerkennung ausländischer Flüchtlinge (2002) and Bundesambt für Migration

und Flüchtlinge (2006).

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

259

who live in the former Soviet Union (Groenendijk 1997).

9

This has meant in

practice that hardly any ethnic Germans from countries outside the former Soviet

Union qualified for Aussiedler status.

Kazakhstan and the Siberian part of the Russian Federation were the most

represented departure countries of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union: in

1998, for instance, 50.4% of all Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union came

from Kazakhstan, 40.4% from the Russian Federation, 3.2% from Kyrgyzstan,

2.8% from Ukraine, 1.5% from Uzbekistan, and 1.6% from the remaining succes-

sor states of the Soviet Union (Waffenschmidt 1999). As we can see in Figure 3, the

number of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union decreased after 1996. The

introduction of a German language test in July 1996 was an important cause of this

decrease. Furthermore, the German authorities reduced the yearly quota of Aussie-

dler from 225,000 to 100,000 in 2000 (Dietz 2002). Ethnic migration from the

former communist European and Central Asian countries to Germany is bound to

end, as people born after 1992 cannot apply for Aussiedler status (Groenendijk

1997). After 2005 there were only a few thousand Aussiedler annually (Bundesa-

mbt für Migration und Flüchlinge 2011).

IV. The Soviet Union

International migration occurred on a very modest scale in the former Soviet

Union until the end of the 1980s. However, within the Soviet Union many people

were involved in interstate migration. Labour shortages and Sovietisation politics

(accompanied by Russification) induced many Slavs to migrate to other non-Slavic

regions of the Soviet Union. Öberg and Boubnova (1993) provide a comprehensive

description of these migration flows. After the Second World War many Russians,

Ukrainians, and Belarussians migrated to the newly acquired territories in the west

of the Soviet Union (the Baltic states, Kaliningrad, and parts of Poland). Another

very large group of migrants was the group of forced migrants during the Stalin

era. Many of these migrants were involved in intrastate migration (mainly from

Western Russia to Siberia). On the other hand, many inhabitants of mainly Russia,

Ukraine, and Belarus, but also of other republics, were forced to migrate to other

states.

10

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the ‘spring period’ set in. Substantial restruc-

turing activities characterised this period. Vast amounts of resources were invested

to develop new land, mainly in Central Asia. Again many people migrated to other

states, especially from the Slavic states to Central Asia. This time migration had a

less coercive character. Most emigrants from Russia, who went to Central Asia,

were relatively higher educated labour migrants, who were attracted to the rapidly

industrialising and modernising urban areas (Lewis and Rowland 1977).

After the disintegration of the Soviet Union many Slavs were induced to return

to their homeland. Therefore, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus experienced net

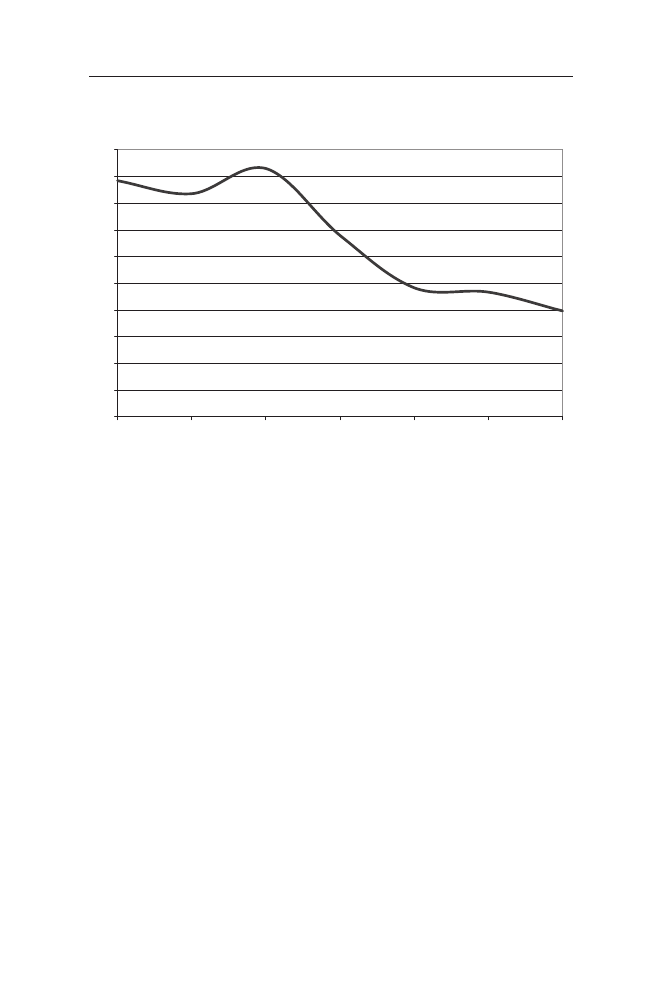

immigration from other non-Slavic former Soviet states. Figure 4 plots the trend of

migration to the Slavic former Soviet states from the non-Slavic former Soviet

states from the dissolution of the Soviet Union to 1998. This figure provides a good

indication of the volume and trend of Slavic return migration in the post-

communist era, although not all migrants are necessarily Russians, Ukrainians, or

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

260

Belarussians. Hence, Figure 4 may overestimate Slavic return migration. On the

other hand, Figure 4 does not capture Slavic return migration from the autonomous

areas of the Russian Federation.

Migration from non-Slavic to Slavic former Soviet states was very large in the

1990s (see Figure 4). Many Slavs left because they were unsatisfied with the

changes in the independent non-Slavic successor states of the Soviet Union.

Furthermore, the withdrawal of troops of the former Red Army, of whom many had

a Russian, Ukrainian, or Belarussian nationality, caused this large emigration flow.

In 1994, a record number of more than 900,000 emigrants from non-Slavic former

Soviet republics entered the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and Belarus. After 1994,

migration from non-Slavic to Slavic republics decreased as the pool of Slavs who

were exposed to considerable pressure to return had shrunk.

Although return migration of Slavs reached enormous proportions after the

dissolution of the Soviet Union, it started earlier. Much south to north migration

also occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. About 300,000 immigrants from

Central Asia entered Russia yearly (Goskomstat 1997). This migration was a result

of the emerging labour surpluses among the rapidly growing (due to high fertility)

Muslim population groups in the less developed southern regions and of chronic

labour shortages in low-fertility, more developed Russia. Most migrants were

probably Russian nationals (Rowland 1993). Additionally, the educational level of

the indigenous population in the south of the Soviet Union had increased signifi-

cantly in the post-war period (Lewis and Rowland 1977). According to Lewis and

Rowland, this educational expansion would reduce the need for high-skilled

Russians in the modern sector in southern regions. Thus, pressure to return may be

Figure 4. Migration (in thousands) to the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and

Belarus from non-Slavic former Soviet Republics in the 1990s

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1000

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

Source: United Nations (2001).

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

261

not the only cause of the Slavic return migration in the former Soviet Union. The

changing supply on the labour market in both the southern (Central Asian and

Transcaucasian) and the Slavic Soviet states may also have played an important

role.

The Poles were another Slavic population group that not only had to face

interstate migration within the Soviet Union on a large scale but also international

migration because of relocations of the Soviet Union’s western border. Millions of

Poles lived in Russia when the Russian Revolution started in 1917. Although

Poland became an independent country in 1918 after World War I, many Poles

continued to live in territories that were part of the Soviet Union after independ-

ence. Similar to ethnic Germans who lived in the Soviet Union, many Poles were

deported to Kazakhstan as part of the collectivisation of agriculture in the 1930s.

At least 250,000 Poles had to make this involuntary journey. An estimated 40% of

this group did not survive the first winter in Central Asia. After the Soviet invasion

of the so-called Kresy region in eastern Poland in 1939, the Soviets also sent

hundreds of thousands of people from this region to Kazakhstan and other Asiatic

parts of the Soviet Union. However, these people were allowed to repatriate to

Poland after the war (Iglicka 1998).

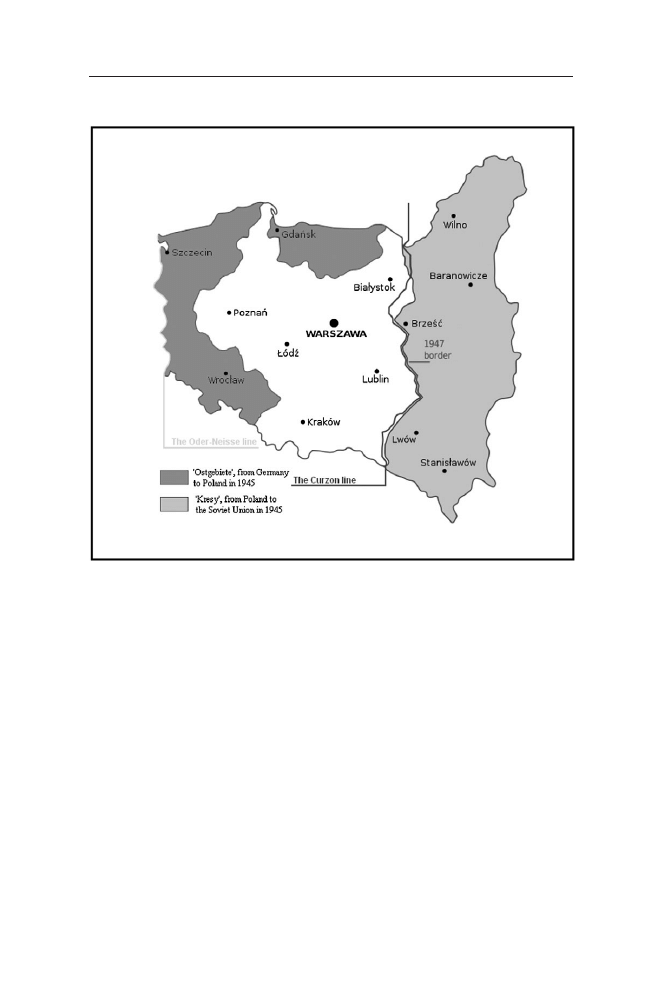

The definitive relocation of Poland’s eastern and the Soviet Union’s western

border after World War II (see Figure 5) was an incentive for 2.2 million Poles to

leave those parts of Poland that became part of the Soviet Union and to settle

themselves west of the Curzon line

11

(Alexander 2003). On the other hand,

hundreds of thousands ethnic Ukrainians, Belarussians, and Lithuanians moved in

the opposite direction (Praz˙mowska 2004). Officially 1.3 million Poles stayed in

the Kresy region after the war (Eberhardt 2006). Moreover, probably some hun-

dreds of thousands of ethnic Poles lived in other parts of the Soviet Union at the

end of the 1940s. In the period 1955–1959, about 250,000 ethnic Poles migrated

from the Soviet Union to their motherland (Korys´ 2003). The official number of

Poles in the Soviet Union in 1989 was still 1.1 million (Korcelli 1992). However,

this might be an underestimation, as many Poles did not register their true ethnicity

in their official documentation (see, e.g., Iglicka 1998). After the fall of commu-

nism, thousands of ethnic Poles repatriated from successor states of the Soviet

Union to Poland (see, e.g., Leven 2008).

V. A Tentative Look into the Future Based on Future

Economic Developments

There are many indications that economic developments have an impact on

migration flows (see, e.g., Hatton and Williamson 2003; Martin, Martin, and Cross

2007; Vogler and Rotte 2000). Both welfare differences between a potential

receiving and a potential sending country and the situation in the labour market in

receiving countries may influence migration flows. The theoretical underpinning

of the impact of welfare differences is based on neo-classical and Keynesian

economic theory while the theoretical underpinning of the impact of the latter is

based on the dual labour market theory (Massey et al. 1993). This theory argues

that the demand for (unskilled) labour in receiving countries often determines the

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

262

entry requirements of these countries. In times of labour shortages, receiving

countries may lower their entry criteria, which enables more potential immigrants

to enter these countries, while in times of large unemployment the opposite may

occur. The aforementioned theories are mostly used to explain labour migration

flows. However, migration driven by other motives may also be partly determined

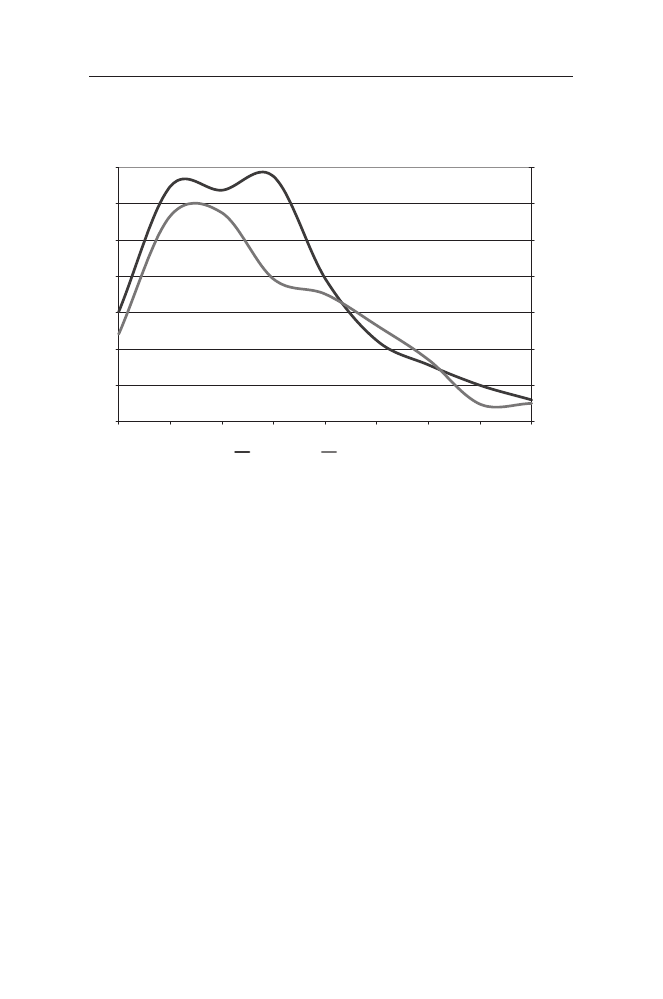

by economic factors (Jennissen 2003). Two figures will be presented to illustrate

the impact of the two aforementioned economic developments (trends in welfare

differences between the receiving and sending country and unemployment in the

receiving country) on ethnic migration in Central and Eastern Europe in this

section. Figure 6 shows the trends of Russian migration from Latvia to the Russian

Federation

12

and the difference in GDP per capita between the Russian Federation

and Latvia

13

in the 1990s.

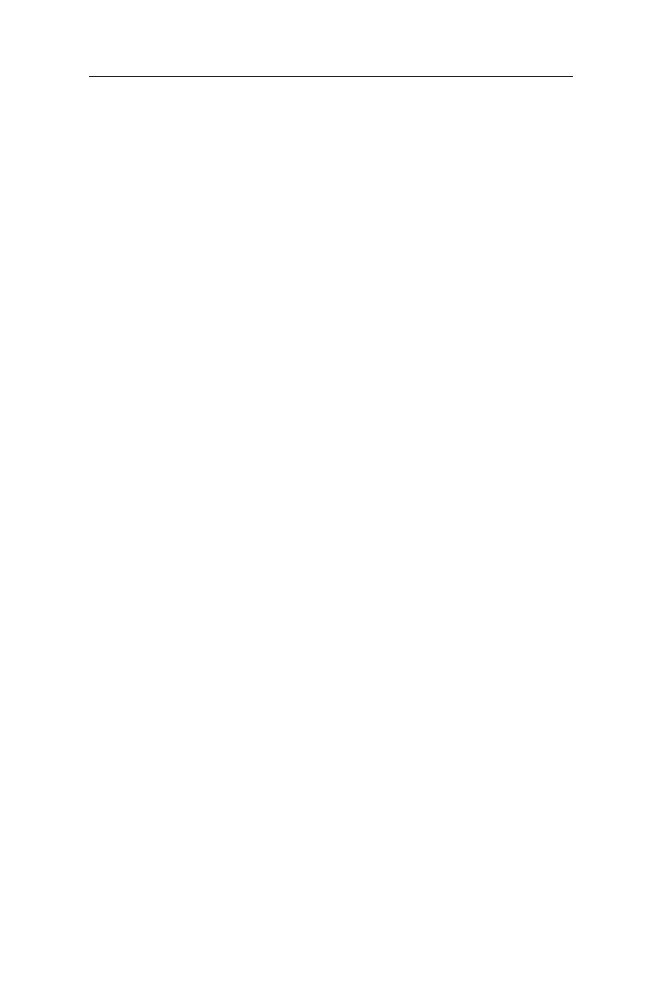

Figure 6 illustrates that the difference in real GDP per capita and ethnic migra-

tion from Latvia to the Russian Federation have a common pattern in the 1990s.

Not surprisingly, welfare differences appear to be the most important economic

determinants of this ethnic international migration flow, which is insensitive to

immigration policies. On the other hand, ethnic migration flows may be largely

affected by immigration policies. The equilibrium recovering function of interna-

tional migration, which removes, according to neo-classical economic thinking,

Figure 5. The relocation of Poland’s borders after World War II

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

263

differences in real wages, does not exist for migration flows that are sensitive to

immigration policies. Here, the argument is made that unemployment in the

receiving country is the most important determinant of international migration

flows that are sensitive to immigration policies. An example of an ethnic migration

flow that is sensitive to immigration policies is presented in Figure 7. This Figure

plots the trends of Aussiedler from Romania

14

and unemployment in Germany

15

in

the 1990s.

Figure 7 shows that the unemployment level in Germany has probably a nega-

tive impact on ethnic migration to Germany. This is an indication that the assumed

negative relation between unemployment in a receiving country and ethnic migra-

tion that is sensitive to immigration policies actually exists.

The deliberate statements about future developments of ethnic migration in

Central and Eastern Europe, which are formulated below, are for a large part based

on expectations about future economic developments. Ethnic migration from

Eastern to Western Europe in the post-communist era has consisted for the

overwhelming part of ethnic Germans who have migrated to Germany. As men-

tioned above, this ethnic migration flow is bound to end in the near future.

However, this does not mean that ethnic migration from Eastern to Western Europe

will completely disappear from the scene at that point in time. The enlargement of

the European Union (EU) in 2004 will probably have moved the border between

prosperous and less prosperous Europe further to the east with the lapse of time, if

the (economic) integration of the new former communist member states is suc-

cessful. This implies that ethnic migration from Romania,

16

Ukraine, and Serbia to

Hungary and ethnic migration from Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan to Poland

will become comparable to what we currently call ethnic migration from Eastern

Figure 6. Migration from Latvia to the Russian Federation (divided by the

midyear Russian population in Latvia) and the difference in GDP per

capita between the Russian Federation and Latvia

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

(mi

g

ran

ts / p

o

p

u

latio

n) x 1000

-2500

-2000

-1500

-1000

-500

0

500

1000

1990 in

terna

tio

n

al $

migration

GDP Russia - GDP Latvia

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

264

to Western Europe. Of course, some differences will still exist; the most significant

one is that, unlike Germany, Hungary and Poland did not bind themselves to

guarantee immigration and citizenship rights to ethnic Hungarians and Poles who

live in other Central and Eastern European states (Brubaker 1998). However, this

situation has been subject to change. For instance, from 2011 ethnic Hungarians

who live permanently in another country than Hungary may apply for a Hungarian

passport through a simplified procedure (Szymanowska and Groszkowski 2011).

Migration from non-Slavic to Slavic former Soviet states was very large in

the 1990s. Many Slavs left because they were unsatisfied with the changes in the

independent non-Slavic successor states of the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the

size of the Slavic population in non-Slavic former Soviet states is still very large,

despite much return migration. About 6.5 million ethnic Russians, for instance,

still lived in Central Asia in 1999 (Zhalimbetova and Gleason 2001). The number

of Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians in the Baltic states was about 1.5

million at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Euromosaic 2004). Develop-

ments in the non-Slavic republics will have a large impact on the extent of future

return migration to Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. The Transcaucasian and Central

Asian republics and Moldova are politically unstable. Moreover, some autono-

mous regions in the Russian Federation (e.g., Chechnya) are politically very

unstable as well. Explosions of (ethnic) violence in these states and autonomous

regions, which are difficult to predict, may lead to large Slavic return flows in the

former Soviet Union. Economic developments in both Slavic and non-Slavic

former Soviet states may also influence this return migration. Slavic return migra-

tion from the Baltic states will decrease further, in view of the expectation that the

Figure 7. Migration of ethnic Germans from Romania (divided by the

midyear ethnic German population in Romania) and unemployment in

Germany

0

50

100

150

200

250

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

(mi

g

ran

ts / p

o

p

u

latio

n) x 1000

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

per

centage

migration

unemployment in Germany

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

265

EU membership of these states will have a positive effect on their economic

development and political stability.

VI. Conclusions

The aim of this article was to describe the historical background of international

ethnic migration in Central and Eastern Europe. The rise and fall of the Habsburg

Empire in Central Europe and the Ottoman Empire in Southeastern Europe was the

underlying cause of many ethnic migration flows in Central and Eastern Europe in

the post-communist era. Moreover, the German Ostkolonisation, border changes

after the two World Wars, and interstate migration in the former Soviet Union

caused a large pool of potential ethnic migrants. In addition, this article discussed

future developments of ethnic migration in Europe based largely on expectations

about future economic developments. Ethnic migration from the countries in

Europe with a communist past to Western Europe will probably end in the near

future, simply because the pool of potential ethnic migrants has become very small.

The border between prosperous and less prosperous Europe probably moves in

gradual stages further to the east with the lapse of time because of the phased and

selective enlargement of the EU. This may cause new cases of large-scale ethnic

migration, which are partly triggered by welfare differences between the sending

and the receiving area. Future ethnic migration for instance from Transylvania and

Vojvodina to Hungary may be comparable to ethnic migration to Germany in the

1990s with regard to the determination of the potential ethnic migrants to move to

the motherland. In all likelihood economic developments will also have an impact

on ethnic migration in the former Soviet Union; however, ethnic migration in this

area is hard to predict as it may be highly influenced by explosions of (ethnic)

violence in the politically unstable regions of the former Soviet Union.

Notes

1

Most Central and Eastern European countries experienced low net emigration in the

period 1960–1988, albeit with some exceptions: East Germany, for instance, experienced

mass emigration before the construction of the Berlin Wall (1961); many Czechoslovakians

left their country in the years around the Prague Spring (1967–1968); and many Poles

migrated from their country at the beginning of the 1980s. The only communist country that

experienced considerable labour emigration was Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia did not maintain

the communist ‘rule’ of full employment. In response to unemployment, the Yugoslav

authorities allowed Yugoslav workers to work abroad.

2

The territory of the former Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia was part of Serbia at the

start of the First World War.

3

In addition to voluntary conversion to Islam, forced conversion also existed. However,

forced conversion was not the typical way inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire were adopted

to Islam (Sarieva 1995).

4

The presence of ethnic Germans in Romania (Transylvania) has a long history. The first

German settlers (Siebenbürger Sachsen), who were invited by the Hungarian king Geysa II

to protect the borders against Mongol and Tartar incursions and to cultivate the land, arrived

as early as the twelfth century (Gabanyi 2000).

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

266

5

We have to keep in mind that although these areas were officially German at that time, the

German population in these areas often constituted only a minority.

6

The contemporary border between the reunified Germany and Poland.

7

Inhabitants of the German Democratic Republic who migrated to the Federal Republic of

Germany were called Übersiedler.

8

For instance, in 2006 about 480,000 ethnic Germans lived in the Russian Federation

(author’s estimation based on the Russian census of 2002, the number of Aussiedler from

the Russian Federation, and the natural population growth in Russia) and about 200

thousand ethnic Germans lived in Kazakhstan (Auswärtiges Amt 2007).

9

Ethnic Germans who migrated to Germany after 1992 are called Spätaussiedler.

10

See Polian (2004) for an overview of forced migrations in the Soviet Union during the

Stalin era.

11

The Curzon line was a proposed demarcation line between Poland and the Soviet Union

during the Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921). In 1945, the Allied leaders agreed that the

Curzon line should be used to determine the eastern border between Poland and the Soviet

Union at the Yalta Conference. The current eastern border of Poland follows the Curzon line

with minor modifications.

12

Source for 1991–1998: United Nations (2001); for 1999 and 2000: Council of Europe

(2000; 2001). I used the immigration tables of the Russian Federation. The number of

migrants is divided by the mid-year Russian population in Latvia (Central Statistical Bureau

of Latvia 2001). Only the number of Russians in Latvia in the beginning of 2000 was

available. The data 1991–1999 have been estimated with the natural increase of Russians in

Latvia (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia 2001) and emigration from Latvia to the

Russian Federation. The natural increase of Russians in Latvia has been estimated as

‘natural increase of the total population of Latvia’ multiplied by (‘natural increase of

Russians in Latvia in 1995’ divided by ‘natural increase of the total population of Latvia in

1995’) for the years before 1995.

13

Source: Maddison (2001). The difference in GDP per capita is expressed in 1990

international dollars. The data for 1999 have been estimated as the data for 1998 times the

quotient of GDP per capita expressed in constant national currencies (International Mon-

etary Fund 2000) in 1999 and 1998.

14

Source for 1991–1996: Mammey and Schiener (1998); for 1997–1999: Bundesambt für

die Anerkennung ausländischer Flüchtlinge (2002). The number of migrants is divided by

the mid-year ethnic German population in Romania (Romanian National Commission for

Statistics 1992, cited in Mures¸an and Rotariu 2000). Only the number of ethnic Germans in

Romania in the beginning of 1992 was available. Data for the other years have been

estimated with the natural increase in Romania (Council of Europe 2001) and emigration of

ethnic Germans to Germany. The assumption has been made that the natural rate of

population growth for ethnic Germans was the same as for the total Romanian population.

15

Source: Gärtner (2000).

16

In the period between Hungary’s and Romania’s successful economic integration in the

EU.

References

Alexander, Manfred. 2003. Kleine Geschichte Polens. Stuttgart: Reclam Verlag.

Auswärtiges Amt. 2007. Außenpolitik A-Z. Berlin: AA.

Bade, Klaus J. 2000. Europa in Bewegung: Migration vom späten 18. Jahrhundert bis zur

Gegenwart. Munich: Verlag C.H. Beck.

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

267

Banchoff, Thomas. 1999. The German Problem Transformed: Institutions, Politics, and

Foreign Policy, 1945–1995. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1998. ‘Migrations of Ethnic Unmixing in the “New Europe”’. Interna-

tional Migration Review 32 (4): 1047–65.

Bucher, Hansjörg. 2000. ‘Regional Internal Migration and International Migration in

Germany since Its Unification’. Paper presented at the annual conference of the

Royal Geography Society with the Institute of British Geographers, Brighton, 5–7

January.

Bundesambt für die Anerkennung ausländischer Flüchtlinge. 2002. Statistik des Bundesa-

mtes. Nürnberg: BAFL.

Bundesambt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. 2006. Migration und Asyl. Nürnberg: BAMF.

Bundesambt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. 2011. Migrationsbericht 2009. Nürnberg:

BAMF.

Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia. 2001. Demographic Yearbook of Latvia. Riga: Central

Statistical Bureau of Latvia.

Council of Europe. 2000. Recent Demographic Developments in Europe. Strasbourg:

Council of Europe.

Council of Europe. 2001. Recent Demographic Developments in Europe. Strasbourg:

Council of Europe.

Courbage, Youssef. 1998. ‘Demographic Characteristics of National Minorities in Hungary,

Romania and Slovakia’. In The Demographic Characteristics of National Minorities in

Certain European States, ed. Werner Haug, Youssef Courbage, and Paul Compton.

Vol. 1. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Cushing, George. 1992. ‘Hungarian Cultural Traditions in Transylvania’. In Historians and

the History of Transylvania, ed. László Péter. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deletant, Dennis. 1992. ‘Ethnos and Mythos in the History of Transylvania: The Case of

the Chronicler Anonymus’. In Historians and the History of Transylvania, ed. László

Péter. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dietz, Barbara. 1995. Zwischen Anpassung und Autonomie: Rußlanddeutsche in der vor-

maligen Sovjetunion und in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Berlin: Duncker und

Humblot.

Dietz, Barbara. 1999. Ethnic German Immigration from Eastern Europe and the Former

Soviet Union to Germany: The Effects of Migrant Networks. Bonn: Institute for the Study

of Labor.

Dietz, Barbara. 2002. ‘East West Migration Patterns in an Enlarging Europe: The German

Case’. The Global Review of Ethnopolitics 2 (1): 29–43.

Eberhardt, Piotr. 2006. Political Migrations in Poland, 1939–1948. Warsaw: SEW UW.

Euromosaic. 2004. Regional and Minority Languages in the New Member States. Luxem-

burg: European Commission.

Fleischer, Henning and Helmut Proebsting. 1989. ‘Aussiedler und Übersiedler – Zahlen-

mäßige Entwicklung und Struktur’. Wirtschaft und Statistik 9: 582–89.

Gabanyi, Anneli U. 2000. Geschichte der Deutschen in Rumänien. Munich: Lands-

mannschaft der Siebenbürger Sachsen in Deutschland.

Gärtner, Manfred. 2000. EUR macro data. St. Gallen: University of St. Gallen.

Goskomstat. 1997. The Demographic Yearbook of Russia. Moscow: State Committee of the

Russian Federation on Statistics.

Groenendijk, Kees. 1997. ‘Regulating Ethnic Immigration: The Case of the Aussiedler’.

New Community 23 (4): 461–82.

Hatton, Timothy J. and Jeffrey G Williamson. 2003. ‘Demographic and Economic Pressure

on Emigration out of Africa’. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 105 (3): 465–86.

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

268

Heinelt, Hubert and Anne Lohmann. 1992. Immigranten im Wohlfahrtsstaat. Am Beispiel

der Rechtspositionen und Lebensverhältnisse von Aussiedlern. Opladen: Leske und

Budrich.

Iglicka, Krystyna. 1998. ‘Are They Fellow Countrymen or Not? The Migration of

Ethnic Poles from Kazakhstan to Poland’. International Migration Review 32 (4):

995–1015.

International Monetary Fund. 2000. The World Economic Outlook Database September

2000. Washington, DC: IMF.

Ingrao, Charles W. 1996. Ten Untaught Lessons about Central Europe: An Historical

Perspective. Minneapolis, MN: Center for Austrian Studies.

Jennissen, Roel P. W. 2003. ‘Economic Determinants of Net International Migration in

Western Europe’. European Journal of Population 19 (2): 171–98.

Kinross, J. and D.B. Patrick. 1977. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish

Empire. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Korcelli, Piotr. 1992. ‘International Migrations in Europe: Polish Perspectives for the

1990s’. International Migration Review 26 (2): 292–304.

Korys´, Izabela. 2003. Migration Trends in Selected EU Applicant Countries: Poland.

Warsaw: CEFMR.

Lewis, Robert A. and Richard H. Rowland. 1977. ‘East is West and West is East . . .

Population Redistribution in the USSR and Its Impact on Society’. International Migra-

tion Review 11 (1): 3–29.

Leven, Bozena. 2008. ‘Immigration – A New Challenge for Poland’. International Review

of Business Research Papers 4 (4): 83–91.

Long, James W. 1988. From Privileged to Dispossessed: The Volga Germans, 1860–1917.

Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Maddison, Angus. 2001. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. Paris: OECD.

Mak, Geert. 2004. In Europa: Reizen door de twintigste eeuw. Amsterdam: Atlas.

Mammey, Ulrich and Rolf Schiener. 1998. Zur Eingliederung der Aussiedler in die Ges-

ellschaft der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Ergebnisse einer Panelstudie des Bundesin-

stituts für Bevölkerungsforschung. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Massey, Douglas S., Joaquín Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, Adela Pellegrino, and

J. Edward Taylor. 1993. ‘Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal’.

Population and Development Review 19 (3): 431–66.

Martin, Philip, Susan Martin, and Sarah Cross. 2007. ‘High-Level Dialogue on Migration

and Development’. International Migration 45 (1): 7–25.

Münz, Rainer and Rainer Ohliger. 2001. ‘Immigration of German People to Germany:

Shedding Light on the German Concept of Identity’. The International Scope Review 3

(6): 60–74.

Mures¸an, Cornelia and Traian Rotariu. 2000. ‘Recent Demographic Development in

Romania’. In New Demographic Faces of Europe, ed. Tomáš Kucˇera, Olga Kucˇerová,

Oksana Opara, and Eberhard Schaich. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

Öberg, Sture and Helena Boubnova. 1993. ‘Ethnicity, Nationality and Migration Potentials

in Eastern Europe’. In Mass Migration in Europe: The Legacy and the Future, ed. Russell

King. London: Belhaven.

Okólski, Marek. 1998. ‘Regional Dimension of International Migration in Central and

Eastern Europe’. Genus 54 (1/2): 11–36.

Péter, László. 1992. ‘Introduction’. In Historians and the History of Transylvania, ed.

László Péter. New York: Columbia University Press.

Polian, Pavel M. 2004. Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations

in the USSR. Budapest: Central European University Press.

Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism: Vol. 11, No. 2, 2011

269

Praz˙mowska, Anita J. 2004. Civil War in Poland, 1942–1948. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Quataert, Donald. 2000. The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Romanian National Commission for Statistics. 1992. Statistical Yearbook 1992. Bucharest:

RNCS.

Rowland, Richard H. 1993. ‘Regional Migration in the Former Soviet Union during the

1980s: The Resurgence of European Regions’. In The New Geography of European

Migrations, ed. Russell King. London: Belhaven.

Sarieva, Iona. 1995. ‘Some Problems of the Religious History of Bulgaria and Former

Yugoslavia’. Religion in Eastern Europe 15 (3): 5–17.

Schoenberg, Hans W. 1970. Germans from the East: A Study of Their Migration, Resettle-

ment, and Subsequent Group History since 1945. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Sinner, Samuel D. 2000. Der Genozid an Russlanddeutschen 1915–1949. Fargo, ND:

Germans from Russia Heritage Collection.

Sked, Alan. 1989. The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire 1815–1918. London:

Longman.

Szymanowska, Lucie and Jakub Groszkowski. 2011. ‘The Implementation of the Hungar-

ian Citizenship Law’. Central European Weekly 4 (101): 2–4.

Thränhardt, Dietrich. 1995. ‘Germany: An Undeclared Immigration Country’. New Com-

munity 21 (1): 19–36.

Tooley, T. Hunt. 1997. National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the

Eastern Border, 1918–1922. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

United Nations. 2001. International Migration from Countries with Economies in Transi-

tion 1980–2000. New York: United Nations.

Van de Kaa, Dirk J. 1996. ‘International Mass Migration: A Threat to Europe’s Borders and

Stability?’ De Economist 144 (2): 261–84.

Vogler, Michael and Ralph Rotte. 2000. ‘The Effects of Development on Migration:

Theoretical Issues and New Empirical Evidence’. Journal of Population Economics 13

(3): 485–508.

Waffenschmidt, Horst. 1999. Integration deutscher Spätaussiedler in Deutschland. Berlin:

Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

Zhalimbetova, Roza and Gregory Gleason. 2001. ‘Bridges and Fences: The Eurasian

Economic Community and Policy Harmonization in Eurasia’. Central Asia Monitor

2001 (5/6): 18–24.

Roel Jennissen: Ethnic Migration in Central and Eastern Europe

270

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

01 [ABSTRACT] Development of poplar coppices in Central and Eastern Europe

Wiśniewski, Piotr; Kaminski, Tomasz; Obroniecki, Marcin Sovereign Wealth Funds in Central and Easte

Mike Haynes Russia and Eastern Europe

Prehistoric copper production in the Inn Valley (Austria) and the earliest copper in Central Europe

Kwiek, Marek Universities and Knowledge Production in Central Europe (2012)

Gender and Racial Ethnic Differences in the Affirmative Action Attitudes of U S College(1)

feminism and formation of ethnic identity in greek culture

e christanse scandinavian in eastern europe

Knapp Thalassocracies in bronze age eastern mediterranean trade making and breaking a myth

feminism and formation of ethnic identity in greek culture

Handbook of Occupational Hazards and Controls for Staff in Central Processing

Male Domestic Workers, Gender, and Migration in italy

Rica de la S , ‘’Social and Labour Market Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Spain’’,

więcej podobnych podstron