The Law of the Sea

The Law of the Sea

History

Sources of the law of the sea

Codification

The Hague Codification Conference of 1930

UNCLOS I 1958

UNCLOS II 1960

UNCLOS III 1973-1982

1982 United Nations Convention on the Law

of the Sea

The Law of the Sea

Maritime areas:

Baselines

Territorial Sea

Contiguous Zone

Exclusive Economic Zone

Continental Shelf

High Seas

The Area

Archipelagic Waters

International Straits

The Law of the Sea

Delimitation of Maritime Areas

The Sea-Bed Authority

Protection of the Marine Environment

Settlement of Disputes

Supplementary Reading

The Law of the Sea - History

The development of the law of the sea cannot be

separated from the development of international law in

general.

The modern law of the sea dates to the beginning of

modern international law in the middle of the 17

th

century.

However, there are many examples of collections of rules

and maritime customs in the Middle Ages (i.e. Rhodian Sea

Law, a Byzantine work compiled between 7

th

and 9

th

centuries,

12

th

century Rolls of Oleron from France, Consolato del Mare,

published in Barcelona in the middle of the 14

th

century,

Maritime Code of Wisby from approx. 1407, followed by the

Hanseatic League). Maritime customs began to be accepted

throughout Europe.

The Law of the Sea - History

Great geographical discoveries

In the 15

th

and 16

th

centuries claims were laid by the

powerful maritime states, especially Portugal and Spain,

to the exercise of sovereignty over vast portions of the

seas. Portugal claimed maritime sovereignty over

the whole of the Indian Ocean and a very big part of the

Atlantic. Spain claimed rights over the Pacific and the

Gulf of Mexico.

The division of the seas and oceans between Spain and

Portugal by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas was approved

by the Pope.

The Law of the Sea - History

Freedom of the seas

In opposition to the principle of maritime

sovereignty, the principle of the freedom of

the seas began to develop. The freedom of the

high seas was seen to correspond to the

general interests of all states, particularly as

regards freedom of commerce between

nations.

The Law of the Sea - History

Hugo Grotius (1583-1645)

Grotius, the Dutch lawyer who is considered to be the

father of international law, is regarded as the father of

the law of the sea as well. Grotius was one of the first to

attack claims to sovereignty over high seas.

In his seminal work on the subject, Mare Liberum (The Freedom of the

Seas), published in 1609, Grotius articulated the principle

of the freedom of the seas, meaning that the sea should

be free and open to use by all countries. His argument was

based on two grounds:

1.

No sea or ocean can be the property of a nation because it is

impossible for any nation effectively to take it into possession by

occupation.

2.

Nature does not give a right to anybody to appropriate things that

may be used by everybody and are exhaustible.

The Law of the Sea - Sources

Customary law

International treaties

1494 Treaty of Tordesillas

1774 Russia – Turkey on Perpetual Peace and Amity

1815 Act of the Congress of Vienna

1884 Paris Convention for the Protection of Submarine Cables

1888 Convention on the Free Navigation of the Suez Canal

1903 Panama – USA Convention for the Construction of a Ship

Canal

1907 Convention concerning the Rights and Duties of Neutral

Powers in Naval Warfare

1907 Convention relative to the Laying of Automatic Submarine

Contact Mines

1910 Brussels Convention for the Unification of certain Rules

relating to Assistance and Salvage at Sea

1923 Geneva Convention and Statute on the Regime of

Maritime Ports

The Law of the Sea - Codification

The Hague Codification Conference of 1930

The Conference was unable to adopt a

convention concerning territorial waters as no

agreement could be reached on the question

of the breadth of territorial waters and the

problem of the contiguous zone. There was,

however, some measure of agreement

regarding the legal status of territorial waters,

the right of innocent passage and the baseline

for measuring the territorial waters.

The Law of the Sea - Codification

UNCLOS I, Geneva 1958

Convention on the Territorial Sea and

Contiguous Zone

Convention on the Continental Shelf

Convention on the High Seas

Convention on the Fishing and

Conservation of Living Resources of

the High Seas

The Law of the Sea - Codification

UNCLOS II 1960

The main purpose of UNCLOS II was to

determine the breadth of the territorial

sea. The Conference failed to agree on

the British 6+6 compromise (6 miles

territorial sea + 6 miles contiguous

zone) proposal.

The Law of the Sea - Codification

UNCLOS III 1973-1982

UNCLOS III experience has been described as “the

largest, most technically complex,

continuous negotiation attempted in modern times”

(R.L. Friedheim).

UNCLOS III negotiated on the basis of consensus, as a

package deal with the understanding that no

reservations to the Convention be permitted.

On April 30 1982 The United Nations Convention on

the Law of the Sea was adopted by voting. 130 states

voted in favour, 4 against (USA, Israel, Turkey and

Venezuela) and 17 abstained.

The Law of the Sea - Codification

1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Law of the Sea Convention was

signed by 117 states on December 10, 1982 in

Montego Bay, Jamaica.

The Convention entered into force in on November 16,

1994 after being ratified by 60 states.

The Convention consists of 17 parts with 320 articles

and 9 annexes

The Convention is a comprehensive code of rules of

international law on the sea. The greater part of the

Convention reflects already existing customary and

conventional (1958 Conventions) law of the sea.

However, much of the previous law was thereby

changed and many new rules introduced.

Baselines

Normal baseline (Article 5)

The normal baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea is

the low water line along the coast as marked on large-scale charts

officially recognized by the coastal State.

Straight baselines (Article 7)

In localities where the coastline is deeply indented and cut into, or if

there is a fringe of islands along the coast in its immediate vicinity, the

method of straight baselines joining appropriate points may be

employed in drawing the baseline from which the breadth of the

territorial sea is measured.

Combination of methods for determining baselines (Article 14)

The coastal State may determine baselines in turn by any of the

methods provided for in the foregoing articles to suit different

conditions.

Internal Waters

Internal waters (Article 8)

Waters on the landward side of the baseline of the territorial sea form

part of the internal waters of the State.

Bays (Article10)

For the purposes of this Convention, a bay is a well-marked

indentation whose penetration is in such proportion to the width of

its mouth as to contain land-locked waters and constitute more

than a mere curvature of the coast. An indentation shall not,

however, be regarded as a bay unless its area is as large as, or

larger than, that of the semi-circle whose diameter is a line drawn

across the mouth of that indentation.

Where the distance between the low-water marks of the natural

entrance points of a bay exceeds 24 nautical miles, a straight

baseline of 24 nautical miles shall be drawn within the bay in such

a manner as to enclose the maximum area of water that is possible

with a line of that length.

Territorial Sea

Every State has the right to establish the

breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not

exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured

from baselines determined in accordance

with this Convention (Article 3)

The outer limit of the territorial sea is the

line every point of which is at a distance

from the nearest point of the baseline equal

to the breadth of the territorial sea (Article

4)

TTerritorial Sea: Innocent Passage

Right of innocent passage (Article17)

Ships of all States, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy the right

of innocent passage through the territorial sea.

Passage shall be continuous and expeditious.

However, passage includes stopping and anchoring, but only in so

far as the same are incidental to ordinary navigation or are

rendered necessary by force majeure or distress or for the purpose

of rendering assistance to persons, ships or aircraft in danger or

distress.

Passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace,

good order or security of the coastal State. The Convention (Article

19) includes a list of activities prejudicial to the peace, good order

or security of the coastal State (e.g. threat or use of force, exercise

with weapons, fishing, propaganda).

Contiguous Zone

Contiguous zone (Article33)

In a zone contiguous to its territorial sea, described as

the contiguous zone, the coastal State may exercise the

control necessary to:

(a) prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal,

immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its

territory or territorial sea;

(b) punish infringement of the above laws and regulations

committed within its territory or territorial sea.

The contiguous zone may not extend beyond 24 nautical

miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the

territorial sea is measured.

Exclusive Economic Zone

The exclusive economic zone is an area beyond and adjacent to

the territorial sea.

In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has:

(a)

sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting,

conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non

living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and

its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic

exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of

energy from the water, currents and winds;

(b) jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions of this Convention with

regard to:

(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures;

(ii) marine scientific research;

(iii) the protection and preservation of the marine environment.

The exclusive economic zone shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles

from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.

Continental Shelf

The continental shelf of a coastal State

comprises the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas

that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the

natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer

edge of the continental margin, or to a distance of

200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the

breadth of the territorial sea is measured where the outer

edge of the continental margin does not extend up to that

distance.

the outer limit of the continental shelf shall not

exceed 350 nautical miles from the baselines from which

the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.

High Seas

High seas regime applies in all parts of the sea that are not

included in the

exclusive economic zone, in the territorial sea or in the internal

waters

of a State, or in the archipelagic waters of an archipelagic State

The high seas are open to all States, whether coastal or

land-locked. It comprises, inter alia, both for coastal and

land-locked States:

(a) freedom of navigation;

(b) freedom of overflight;

(c) freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines;

(d) freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations

permitted under international law;

(e) freedom of fishing;

(f) freedom of scientific research.

The Area

The Area and its resources are the common heritage

of mankind (Article 136)

No State shall claim or exercise sovereignty or

sovereign rights over any part of the Area or its

resources, nor shall any State or natural or juridical

person appropriate any part thereof. No such claim or

exercise of sovereignty or sovereign rights nor such

appropriation shall be recognized.

All rights in the resources of the Area are vested in

mankind as a whole, on whose behalf the Authority shall

act.

STRAITS USED FOR INTERNATIONAL

NAVIGATION

Straits used for international navigations are straits which

are used for international navigation between one part of the

high seas or an exclusive economic zone and another part of

the high seas or an exclusive economic zone.

In international straits all ships and aircraft enjoy the right

of transit passage, which shall not be impeded.

Transit passage means the exercise of the freedom of

navigation and overflight solely for the purpose of continuous

and expeditious transit between one part of the high seas or an

exclusive economic zone and another part of the high seas or

an exclusive economic zone.

States bordering straits may designate sea lanes and

prescribe traffic separation schemes for navigation in straits where

necessary to promote the safe passage of ships.

There shall be no suspension of transit passage.

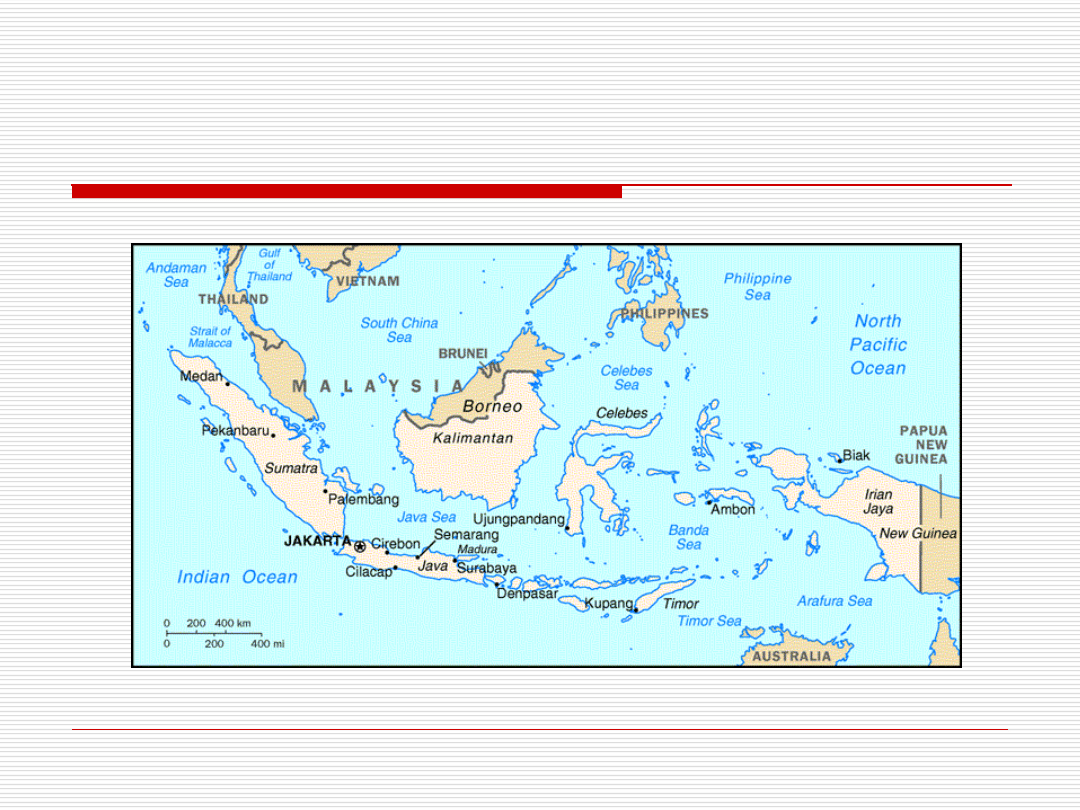

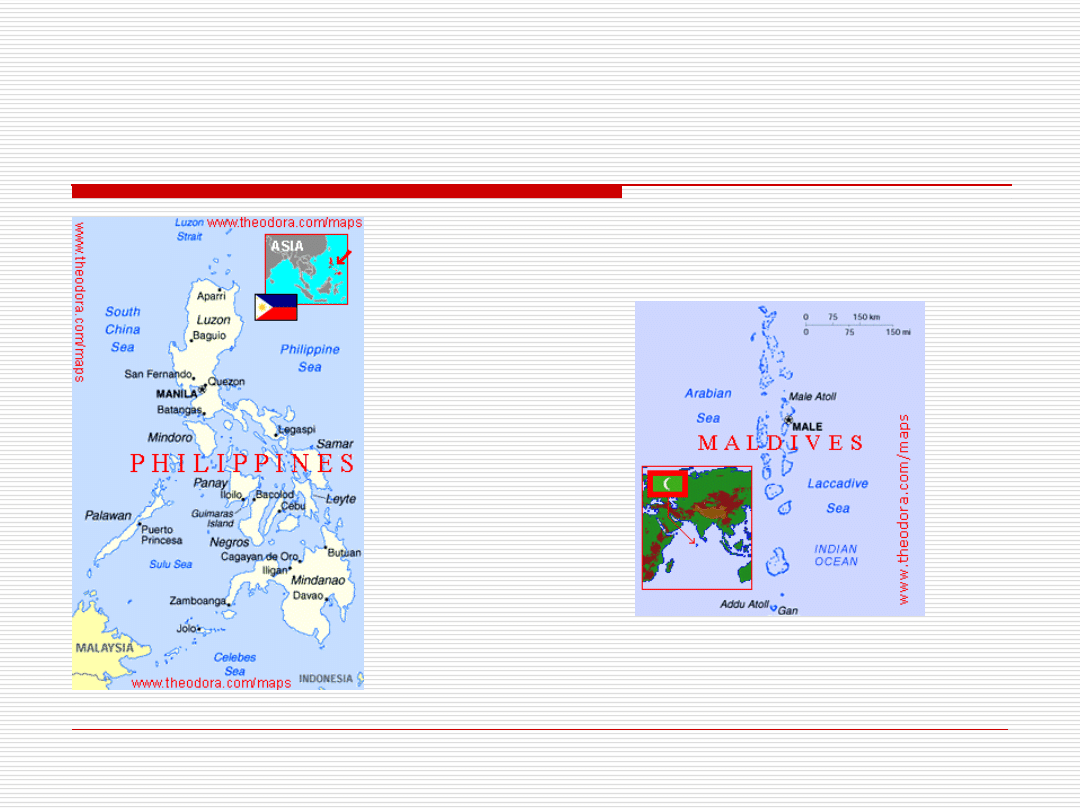

Archipelagic States

"archipelagic State" means a State constituted wholly

by one or more archipelagos and may include other islands

(Indonesia, for instance, consists of 17 508 islands);

"archipelago" means a group of islands, including parts of islands.

An archipelagic State may draw straight archipelagic baselines

joining the outermost points of the outermost islands of the

archipelago provided that within such baselines are included the

main islands and an area in which the ratio of the area of the water

to the area of the land, including atolls, is between 1 to 1 and 9 to

1.

The length of such baselines shall, in principle, not

exceed 100 nautical miles.

The breadth of the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the

exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf shall be

measured from archipelagic baselines.

Archipelagic States

Archipelagic States

Archipelagic States - Archipelagic

Sea Lanes Passage

The breadth of the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the

exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf shall be measured

from archipelagic baselines drawn in accordance with article 47.

The sovereignty of an archipelagic State extends to the waters

enclosed by the archipelagic baselines. This sovereignty extends to the

air space over the archipelagic waters, as well as to their bed and

subsoil, and the resources contained therein.

All ships and aircraft enjoy the right of archipelagic sea lanes

passage in such sea lanes and air routes.

Archipelagic sea lanes passage means the exercise in accordance

with this Convention of the rights of navigation and overflight in the

Normal mode solely for the purpose of continuous, expeditious and

Unobstructed transit between one part of the high seas or an exclusive

economic zone and another part of the high seas or an exclusive

economic zone.

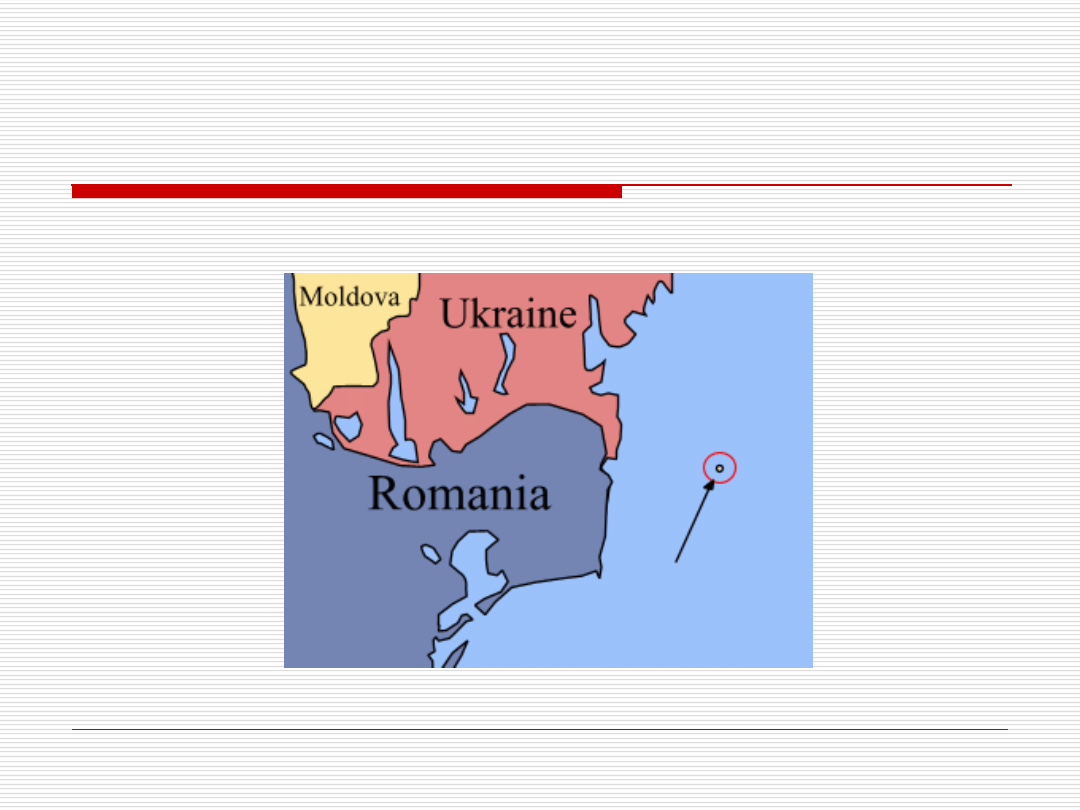

Delimitation of Maritime Areas –

Snake Island Case

Delimitation of Maritime Areas –

Snake Island Case

Document Outline

- The Law of the Sea

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- The Law of the Sea - History

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- The Law of the Sea - Sources

- The Law of the Sea - Codification

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Baselines

- Internal Waters

- Territorial Sea

- TTerritorial Sea: Innocent Passage

- Contiguous Zone

- Exclusive Economic Zone

- Continental Shelf

- High Seas

- The Area

- STRAITS USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION

- Archipelagic States

- Slide 26

- Slide 27

- Archipelagic States - Archipelagic Sea Lanes Passage

- Delimitation of Maritime Areas – Snake Island Case

- Delimitation of Maritime Areas – Snake Island Case

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

dr berry introduction to the law of the sea

The law of the European Union

Men of the Sea 1 0

the tragic ending of bonaparte of the sea OZC7OZY65JPIDVN4IH4423GPPGVL5HUKVHRO66Y

Stare?cisis and the Law of Precedent

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Analysis of the?ginning

Helsinki Principles on the Law of Maritime Neutrality

The Universal Law of Attraction

The law of the European Union

The law of attraction

Liber CL (The Law of Liberty) by Aleister Crowley

the law of one book 3

Liber DCCCXXXVII The Law of Liberty (Book 837)

Forstchen, William R Into the Sea of Stars

Law of the Wolf Tower Tanith Lee

The Law Of Attraction

Chains of the Sea Gardner Dozois

więcej podobnych podstron