HENRY

JAMES

(1843-1916)

• James was born in

New York City on Apr.

15, 1843

• the second son of

Henry James, a noted

Swedenborgian

theologian and social

theorist, and the

younger brother of

William James, the

psychologist and

philosopher

Henry James at eight years

old with his father, Henry

James, Sr.

-a daguerreotype by Mathew

Brady

• James’ childhood and

early youth were passed

in unusually stimulating

surroundings:

He belonged to a novel-reading,

playgoing family

Thomas Carlyle and Ralph Waldo

Emerson were frequent visitors to

the household

• The family had a

substantial income--Henry

James, Sr., had inherited

his father's estate of $3

million--and periodically

lived in Europe.

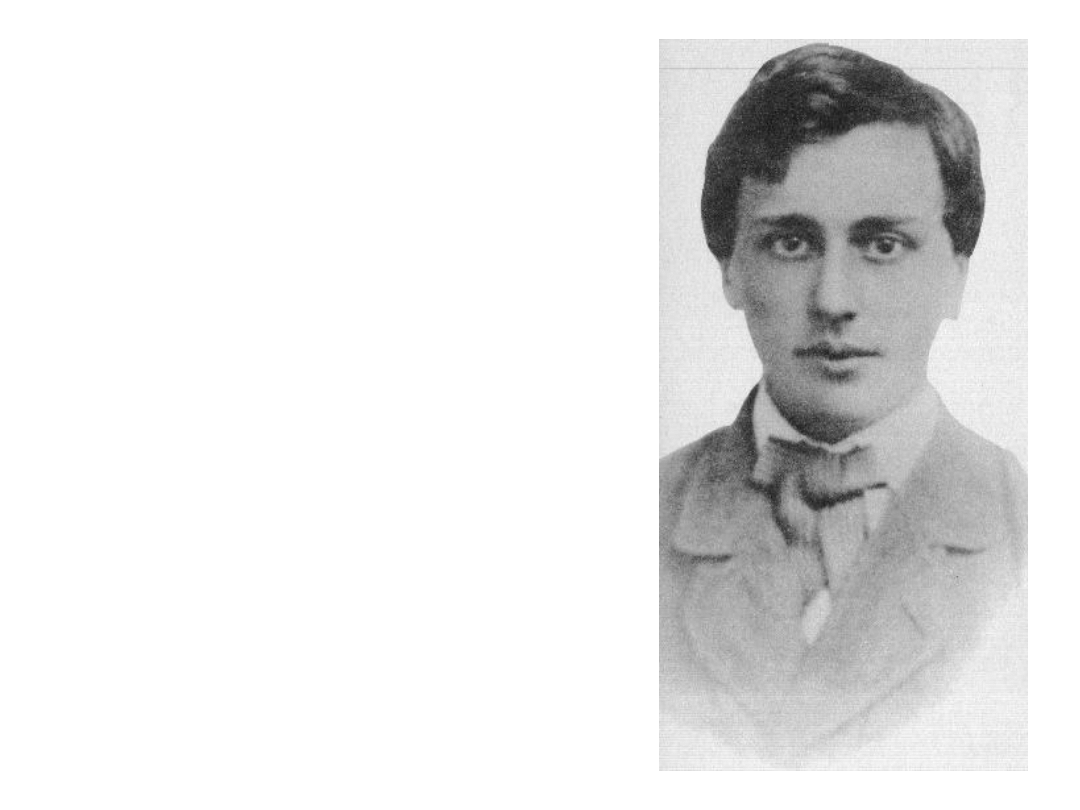

James at 16

education

• James went to a number of schools and was

provided with private tutors.

• His education came from his walks, his reading,

especially of novels, and his visits to the parks

and museums of European cities where he

observed the people around him.

• In 1860 the James family returned from Europe

and settled in Newport, R.I. There the 17-year-

old Henry developed a friendship with the painter

John La Farge, which is reflected in his fiction:

many of James' major characters are artists, and

his imagery is often derived from painting.

• In 1861 James received a back injury

which prevented him from enlisting

with the North at the outbreak of the

Civil War.

• In 1865 James' first signed short

story appeared in the Atlantic

Monthly. Its editor, William Dean

Howells, became a lifelong friend.

Europe

James made his first independent trip to Europe

in 1869, going first to London and then to the

continent. He observed not only the countries

themselves but also his fellow citizens:

Americans adrift in the Old World, bewildered

by an environment with deep historical

associations, filled with a profound sense of

human corruption but also an appreciation for

beauty and the sensuous texture of experience.

This year abroad provided James with the

"international" theme

of much of his fiction: the

collusion of the Old and the New Worlds, usually

in the form of some innocent American lured

but finally betrayed by Europe.

Work – 1870s

• First novel, Watch and Ward, in 1870.

• First significant short story, "A

Passionate Pilgrim," published in the

Atlantic Monthly in 1871. His early

tales, usually depicting American

manners and relationships, reflect the

influence of Dickens, Balzac,

Hawthorne, and George Eliot.

• Roderick Hudson (1875), a novel

describing the disintegration of a young

American sculptor living in Rome.

Paris

• In 1875 he took up residence in Paris

• a friend of the Russian novelist Ivan

Turgenev

• Member of the literary circle

composed of Gustave Flaubert, Guy

de Maupassant, Émile Zola, Alphonse

Daudet, and Edmond de Goncourt

London

James felt himself an outsider in France, and in 1876 he

emigrated to England.

He lived in London for two decades, occasionally

journeying to the continent to gather material for his

travel writing.

His fiction focused on the international theme.

• The American (1877)

• Daisy Miller (1878)

• The Portrait of a Lady (1881)

• Washington Square (1881)

• The Bostonians (1886)

• The Princess Casamassima (1886)

• The Tragic Muse (1890)

• In 1897 James purchased

Lamb House in Rye.

• He divided his time

between writing and

entertaining visitors.

• Led a remarkable social

life: he records dining

out 107 times one

winter.

• A great favorite with

the ladies, he never

married.

• James' emotional life

has long fascinated

critics.

His fiction is unusually

cerebral in nature,

continually emphasizing

intellectual perception

rather than immediate

physical experience.

A photograph of James in 1897

Work – 1900s

With the turn of the

century, James entered

into his final and

greatest period of

writing, producing three

massive novels:

• The Wings of the Dove

(1902),

• The Ambassadors

(1903),

• The Golden Bowl

(1904).

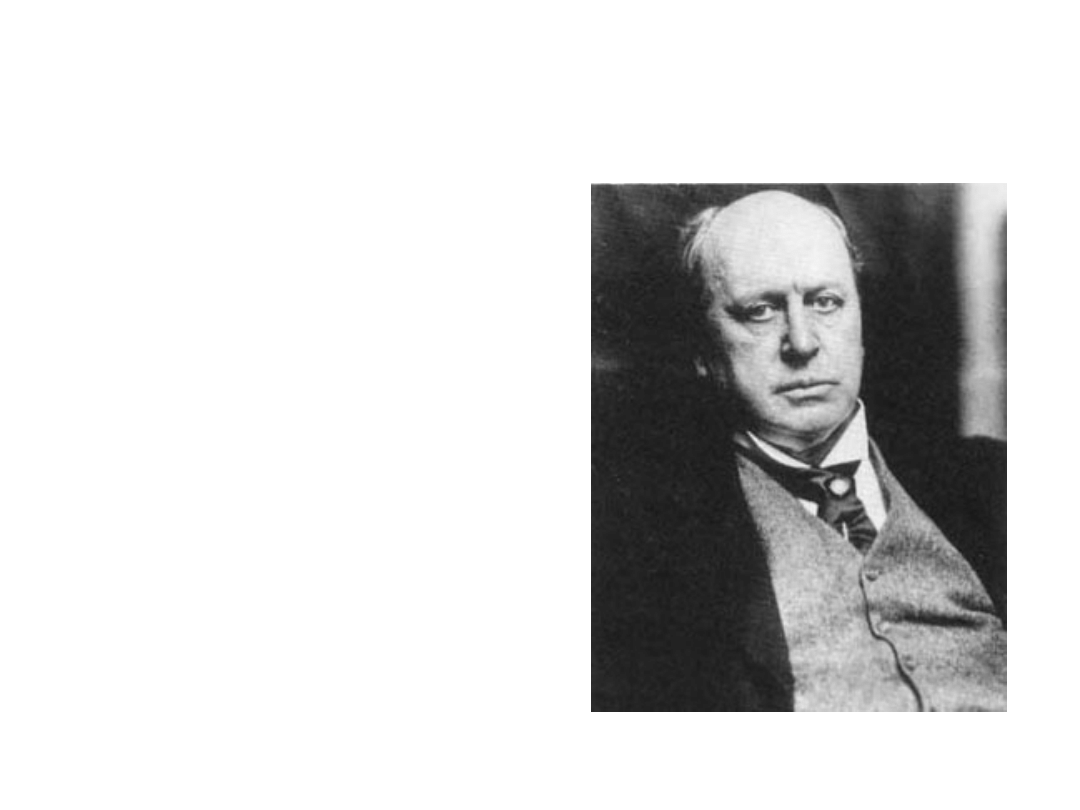

Henry James in

1904

• In 1904 he returned to the United States and toured

the country. The product of this trip was The

American Scene (1907), a somewhat pessimistic

analysis of American life.

• During the remainder of his life, James chose and

revised the pieces to be included in the 24-volume

"New York edition" of his works; he wrote his

famous prefaces on the art of fiction for this edition.

• Between 1910 and 1914 he completed two volumes

of a projected 5-volume autobiography: A Small Boy

(1913) and Notes of a Son and Brother (1914).

• He also started two novels, The Sense of the Past

and The Ivory Tower, and a volume of

autobiography, The Middle Years, which were never

finished.

• In 1915 James

became a British

subject to protest the

neutrality of the

United States during

the early years of

World War I. Later

that same year he

was awarded the

Order of Merit by

George V.

• He died in London on

Feb. 28, 1916, and his

ashes were returned

to Cambridge, Mass.,

for burial in the James

family plot.

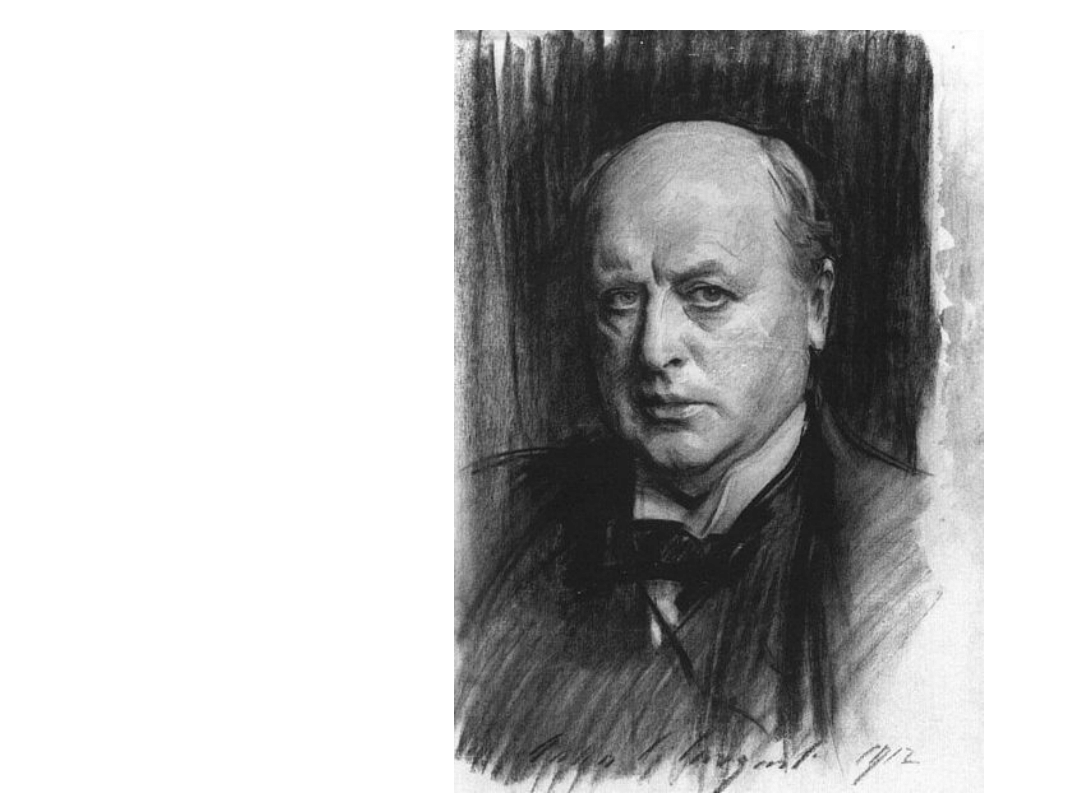

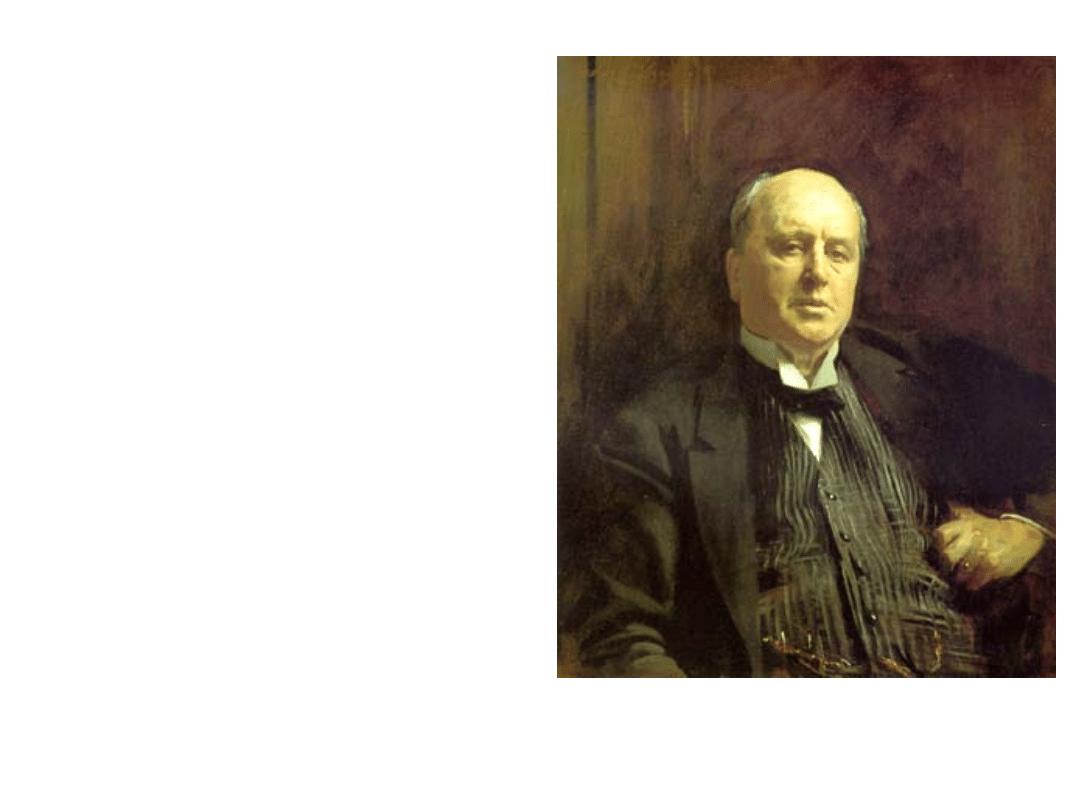

A 1913 portrait of James by Sargent

James’s theory of fiction

As a critic James asked such questions as:

• What makes a good novel?

• How does an author construct one?

• What is the relationship between the way a novel

is constructed (its form or shape) and the vision of

life it contains?

• From what point of view should the story be

narrated: Should it be told directly by the author,

who presents the thoughts and feelings of all the

characters, or, as James came to think, should the

narrator be a single character in the novel, who

only knows what he sees, feels, and observes?

Although the English novel had existed for over a

century, these questions had never before been

considered in a systematic fashion.

Classic essay “

The Art of Fiction”

(1884):

• A novel has only one obligation: to be

“interesting.”

• The novel is “a personal, a direct impression

of life; that, to begin with constitutes its

value, which is greater or less according to

the intensity of the impression.”

• By “life,” or experience, what James really

meant was “a mark made on the

intelligence.” Hence, he preferred not to

render “the affair at hand,” but rather

someone’s impression of the affair.

Thus James was one of the first great--and conscious--

experimentalists

in the craft of fiction, exploring

new ways of seeing and shaping life through new

ways of telling a story.

In his late fiction especially,

the story is told

through the eyes of an interested, usually

perceptive observer

James felt this made the work more compelling

since the reader sees only what the observer sees

and follows the workings of his mind as he tries to

understand the meaning of various appearances in

the world around him

Typically, these appearances are misleading

The “action” in the novels consists of the observer

gradually penetrating appearances and

comprehending the truth

influence

James’ technique of dramatizing

thought profoundly altered the history

of the novel. His influences can be

seen in the works of such authors as

Joseph Conrad,

Dorothy Richardson,

Virginia Woolf,

James Joyce.

Works

During his lifetime James produced

• 20 full-length novels

• a dozen novellas

• over 100 tales

• in addition he wrote

autobiographies, essays, criticism,

biography, travel literature, and

thousands of letters.

Works

James' critics usually divide his career

into three periods:

• The first or "early" phase (1865-

1882)

• The middle period (1882-1900)

• The last period (1900-1904)

Early Period (1865-1882)

The first or "early" phase was the period of

apprenticeship as a writer, culminating with the

publication of The Portrait of a Lady in 1881.

• Pervading the early period is the so-called

"international" theme

, a complicated concept

because, for James, America and Europe each had both

a positive and a negative side.

• The positive aspect of the American character was its

vitality, reliability, innocence; the negative, a tendency

to over-simplify life and to mistrust beauty, art, and

sensuality. The European character was positive in its

appreciation of beautiful and pleasurable experience as

well as in its sophisticated awareness of the

complexities of human nature, and negative in its

amorality and expedience.

• James' novels may be viewed as an attempt to find a

way of life that would combine the good aspects of both

worlds.

Early period: most important

works

• The novella

Daisy Miller

and the novels

Roderick Hudson

and

The American

concern

generous but naive Americans who are defeated

by a corrupt European environment.

• The Europeans

(1878) reverses the theme and

deals with a European thwarted in America: the

Baroness Eugenia-Camilla-Dolores-Münster comes

with her brother to New England from Europe to

stay with some wealthy American cousins in the

hope of making her fortune, but is rejected for her

amorality by the bachelor she had hoped to marry.

• The Portrait of a Lady

, a brilliant rendering of a

proud spirit trapped by a combination of

circumstances; inexplicable fact: it ends with

Isabel's decision to remain with Osmond.

Middle Period (1882-1900)

• James abandoned the international theme, and

eventually fiction itself, for drama writing seven plays in

five years.

• Failing in the theater he again returned to fiction,

utilizing, however, the theatrical techniques he had

learned. Such works as

The Spoils of Poynton

(1897),

What Maisie Knew

(1897), and

The Awkward Age

(1899) reveal the effects of James' flirtation with drama.

• The Bostonians

grew partly out of the contemporary

feminist movement, focuses on two women--charming,

delicate Verena Tarrant and the strong-minded,

aggressive suffragette Olive Chancellor. The contrast

between their two personalities produces a conflict,

with certain sexual overtones. The novel is notable for

its emphasis on the effects of environment.

The Princess Casamassima

Its hero, Hyacinth Robinson,

disgusted by the appalling social

conditions in London, joins a radical

underground movement. When he is

selected to perform an assassination,

however, he is torn between his belief

in socialism and his duty as a civilized

member of society, and he finally

commits suicide.

The Turn of the Screw

During the middle period James became preoccupied

with ghost stories ("The Jolly Corner," "The Friends

of the Friends") and with stories about tortured

childhood and adolescence ("What Maisie Knew",

"The Awkward Age").

These concerns come together in his famous novella

The Turn of the Screw

(1898).

• James had been fascinated with a friend's tale about

"a couple of small children in an out-of-the-way place,

to whom the spirits of certain ‘bad’ servants, dead in

the employ of the house, were believed to have

appeared with the design of getting hold of them."

• The real genius of The Turn of the Screw is that every

detail is susceptible to more than one interpretation.

The tale brilliantly exemplifies James' theory of the

horror story: to suggest rather than state the horror,

letting the reader imagine his own evil since what he

imagines will be more frightening than an explicit

statement.

The middle period is also notable for two of James' small

masterpieces,

The Aspern Papers

(1888) and

The Beast in the Jungle

(1903).

• The hero of The Beast in the Jungle is a refined,

egotistic gentleman, John Marcher, who feels that an

extraordinary fate will overtake him. He confides his

belief to a close friend, May Bartram, and then waits for

"the hidden beast to spring." It is only upon his friend's

death that Marcher realizes the truth of his fate: he is

the man to "whom nothing was to have happened"; his

obsession had blinded him to May Bartram's love and

thus to his one chance for a rich and meaningful life.

• A theme dominant in James: the immorality of that

excessive dedication to ideas or ideals--literary, artistic,

or metaphysical—that violates human considerations.

Last Period (1900-1904)

James returned to the international

theme to write his three greatest novels,

•The Wings of the Dove,

•The Ambassadors,

•The Golden Bowl,

characterized by a masterful use of

symbolism and a radical complexity

both of style and of moral vision.

The Wings of the Dove

concerns a

young American heiress, Milly Theale, who is at

once possessed of a great capacity for life and

doomed by a fatal illness. A famous physician in

England tells her that with sufficient will she

may have a chance to survive. He suggests that

falling in love may save her. She does fall in

love, with an impoverished young journalist

named Merton Densher, who, unknown to Milly,

is in love with her friend Kate Croy, a brilliant,

beautiful, but penniless English girl. Kate loves

Merton but, also desiring wealth, conceives a

plot: Merton will marry Milly and, when she dies,

inherit her fortune. Then Kate and he will marry

and live in great style on the inheritance. …

Milly discovers the plot and the discovery kills

her. James says, however, that everything that

happened to Milly constituted "what she should

have known"; she should not have trusted

appearances. The irony is that she would have

died sooner had she not trusted appearances--

she was doomed either way. In the end, she

leaves Merton her fortune anyway. This act, in its

rather scalding generosity, causes Merton to

loathe what he has done and to fall in love with

Milly's "memory," turning against Kate when she

wishes him to keep the money. Thus all three

characters are ravaged. The novel is a profound

study of interlocking human guilt and woe.

The Ambassadors

dramatically exemplifies the effectiveness of

James' narrative technique. The novel is

presented through the hero's

consciousness; its events are his

perceptions; its theme is the lasting value of

the insights gained from these perceptions.

The following quotation illustrates not only

the quality of Strether's mind, which

apprehends a rural scene in terms of art and

literature, but also James' indirect method of

presenting the workings of that mind:

He had taken the train, a few days after this,

from a station--as well as to a station--

selected almost at random; such days, whatever

should happen, were numbered, and he had gone

forth under the impulse--artless enough, no

doubt--to give the whole of one of them to that

French ruralism, with its cool special green,

into which he had hitherto looked only through

the little oblong window of the picture frame.

It had been as yet, for the most part, but a

land of fancy for him--the background of

fiction, the medium of art, the nursery of

letters; practically as distant as Greece, but

practically also as consecrated.

The style of this section, typical of James, with sentences

turning back upon and qualifying themselves with dashes

and clauses as further feelings and ideas suggest

themselves, has been criticized as fussy and convoluted.

However, James' concern was to reflect processes of

thought and sensibility whose complexity and progression

could, he felt, only be captured by a parallel complexity in

syntax and diction.

The Golden Bowl

is often considered

James' most difficult work. The plot itself is

complicated since the characters are usually

acting upon knowledge they are attempting

to conceal from each other. Also, perhaps

because James dictated the novel, its style

is especially oblique and convoluted. In

spite of its difficulty, however, The Golden

Bowl is a great moral study of suffering,

masterfully depicting the anguish that

accompanies all important human

relationships.

Critical Writings

• James' treatment of novelists in such works as

French Poets and Novelists (1878) and Notes on

Novelists (1914) was acutely perceptive. His studies

of George Sand, George Eliot, and Balzac, and the

essays on Turgenev, Trollope, Daudet, Maupassant,

Loti, and D'Annunzio are particularly worthy of note.

• Hawthorne (1879) accurately states Hawthorne's

excellences and limitations as a novelist.

• James' prefaces to the “New York edition” of his

works comprise one of the outstanding examples of

a creative artist's commentary on his own

performance and are regarded as essential to a truly

comprehensive understanding of the art of fiction.

Recent fictionalized

biographies:

David Lodge, Author, Author (2004)

Colm Tóibín, The Master (2004)

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

- Slide 18

- Slide 19

- Slide 20

- Slide 21

- Slide 22

- Slide 23

- Slide 24

- Slide 25

- Slide 26

- Slide 27

- Slide 28

- Slide 29

- Slide 30

- Slide 31

- Slide 32

- Slide 33

- Slide 34

- Slide 35

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Robert Silverberg The Martian Invasion Journals of Henry James

HENRY JAMES Daisy Miller

Henry James Daisy Miller

Henry James The Turn of the Screw

HENRY JAMES Daisy Miller

Silverberg, Robert The Martian Invasion Journals of Henry James(1)

Henry James Daisy Miller

Daisy Miller, by Henry James

Daisy Miller by Henry James

Henry James Daisy Miller

Henry James DAISY MILLER

Henry James

Henry James The Jolly Corner

Rawlings American Theorists of the Novel Henry James, Lionel Trilling, Wayne C Booth

Henry James doc

Henry James Daisy Miller

Henry James The Beast in the Jungle

więcej podobnych podstron