image005

The above information corresponded to the State of research at the time of the publication of the Dictionary. But ten years of fruitful excavation work added new cult buildings to the group of those known from the written sources such as the temples in Radogośc, Szczecin, Wolin, Wolgast (Wołogoszcz), Garz and Gutzkow. In 1967 remains of temples were dis-covered near Feldberg, later in Wolin, Gross Raden, Ralswiek and Parchim, in some other cases the function of the building is unclear.

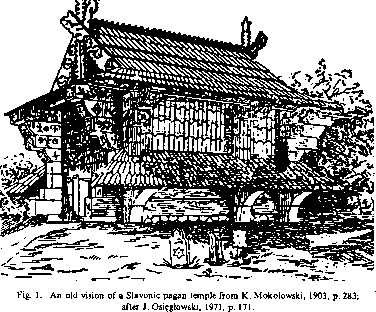

The first task is to specify what can be considered as a tempie, because this term is sometimes applied to all sanctuaries, both those situated in roofed buildings and those where gods were worshiped in the open air. The author of this work reserves the name of tempie to a roofed building regarded as a place of revelation or presence of a deity or deities, containing their effigies or symbols, sacred and guarded by a taboo, constituting a centre of cult rituals. No definition is perfect, so this one also causes certain problems. The Slavs (like the Germans and other tribes) had some buildings used by the community for both religious and secular purposes, in which sacrifices, prayers and rites, including ritual feasts and carouses, took place along with entertainment and counselling. That type of buildings can be named “cult hall” to distinguish them from sacrosanct temples. The union of sacrum and profanum should not shock us. The borderline between a ritual feast and secular celebration was certainly fuzzy, while the cult was intertwined with all aspects of merrymaking. Until now merrymaking, trad-ing and social gatherings are closely connected with cult and holidays, in earlier times the connection used to be even stronger.

In written sources temples and cult halls are referred to by various names. Apart from Latin (Wienecke, 1940, p. 190-192), 01d-Scandinavian (Knytlingasaga, ch. 122), or even Arabie expressions, we are lucky to know native Slavonic names, which are First of all the Ruthenian word khram and Pomeranian kącina. The former was recorded in the llth, the latter in the 12th century. Both unambiguously denote a building used for cult purposes. Khram, apart from “a pagan tempie” (khram idolsky), later often meant “a church” or “an Orthodox church,” it can also refer to a house, a hut or a hall, but never signifies open space. Apart from Old Ruthenian and Old Church Slavonic, this word is attested in Bulgarian (khram — tempie), Slovene (hram = house, the house of God, peace), Czech (chram = church), Polish (Old Polish and dialectal chromina = hut) and Lower Lusatian (chrom = building) (Sreznievsky, vol. 3, 1956, p. 1398-1399; Vasmer, 1953-1958, vol. 3, p. 263-264). The word kącina is also unąuestionable. Although Romantics tried to interpret the Latin transcription contina wrongly as gontyna (“a house with a shingle roof,” from the word gont = shingle), the correct etymology of this word, deriving kącina from kąt — comer, includes into the explanation of its sense the notion of “a building with a roof.” The word kąt (the place where two walls meet) is used in Polish until now to denote a house or fiat. The Old Polish phrase

cztyrzy kąty (four comers) mean simply a house. Kutina in Czech and k’tina in Bulgarian mean “a hut” (Sławski, vol. 1, 1952-1956, p. 318-319; Słownik Staropolski, vol. 3, 1960-1962, p. 263). Thus, kącina was a building with four corners, a house that could function as a place of meetings and a seat of deities.

Less attention has been devoted to the words bożnica and świątynia. Bożnica, derived undoubtedly from bog (god), was recorded in 1146 in Primary Chronicie as mysterious “Turowa bozhnica.” In contemporary Polish bożnica means only “synagogue,” but according to A. Bruckner (1985a, p. 34) it used to denote any “house of god.” The word świątynia (from svęt, święty = holy), although not recorded as early as the previous one, may have eąually ancient etymology. This claim is supported by the existence of Polish villages named Świątniki in which ancillary peasants serving the churches lived in the times of the first Piasts (SSS, vol. 5, p. 578).

The fact that recorded words denoting temples differed in Western and Eastem Slavs was used by H. Łowmiański (1979, p. 230) as an argument for the thesis that originally the Slavs did not know temples sińce there is no common expression for that notion. The word kącina, however, seems to be a pars pro toto type of name, and the fact that it was recorded

13

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

04 wells (1) CMAPTER HO. ABOVE o CRYPT 5TAIR3 TO TOWER ; FOUNDATION OF

04 wells (1) CMAPTER HO. ABOVE o CRYPT 5TAIR3 TO TOWER ; FOUNDATION OF

2 Twelve to fifteen are usually laid at one time on submerged objects, G. subsłriałus Steph. and G.

V V ALAN 1 Yom thc shadow of thc I worfchouse to thc luxury of tlie TITANIC. But is Lifs dream

image071 corresponding to the political primacy of the town’s rulers, sovereigns of Ruthenia ciaimin

image002 Thls is a fascinating addition to the world of "what If” fiction THE TIMES What If t

image007 Mon. Tues. Wed. Thurs. Frl. Sat Day of the week Walce cime Had to be woken

image008 THE ENGINE AT HEARTSPRINGS CENTER Take away the will to live. nan becomes a machi

00100 ?e6667c29dfdea3c59f1657bb3f2b02 99 The OCAP manufacturing process remains in an unknown State

488 The main thesis is that morę information relevant to the shareholders is revealed on the website

morphographical survey will also be reąuired to map the Pleistooene and Holocene sediments. Above al

EPIA 2011 ISBN: 978-989-95618-4-7 To extract the gamę State of a database of played poker, an applic

Chapter III - FINANCES 1. Factual Information Pursuant to the Act of Higher Education the University

image001 The"SECOND EXPERIMENT By J. O. Jeppson. The fas-be the key to eternity—or doom. At you

image001 ‘The past is hrought to life willi hrilliant colours, comhincd willi a perfect whodunit. Wh

image001 THE CITY OP THE’ (Mustration by Paul) The man with the metal mask rosę, and going to the bo

image002 SOMETHING NEW IN 1 0 • • U 1 i 0 In addition to a fuli score of the very best in new sc

więcej podobnych podstron