image078

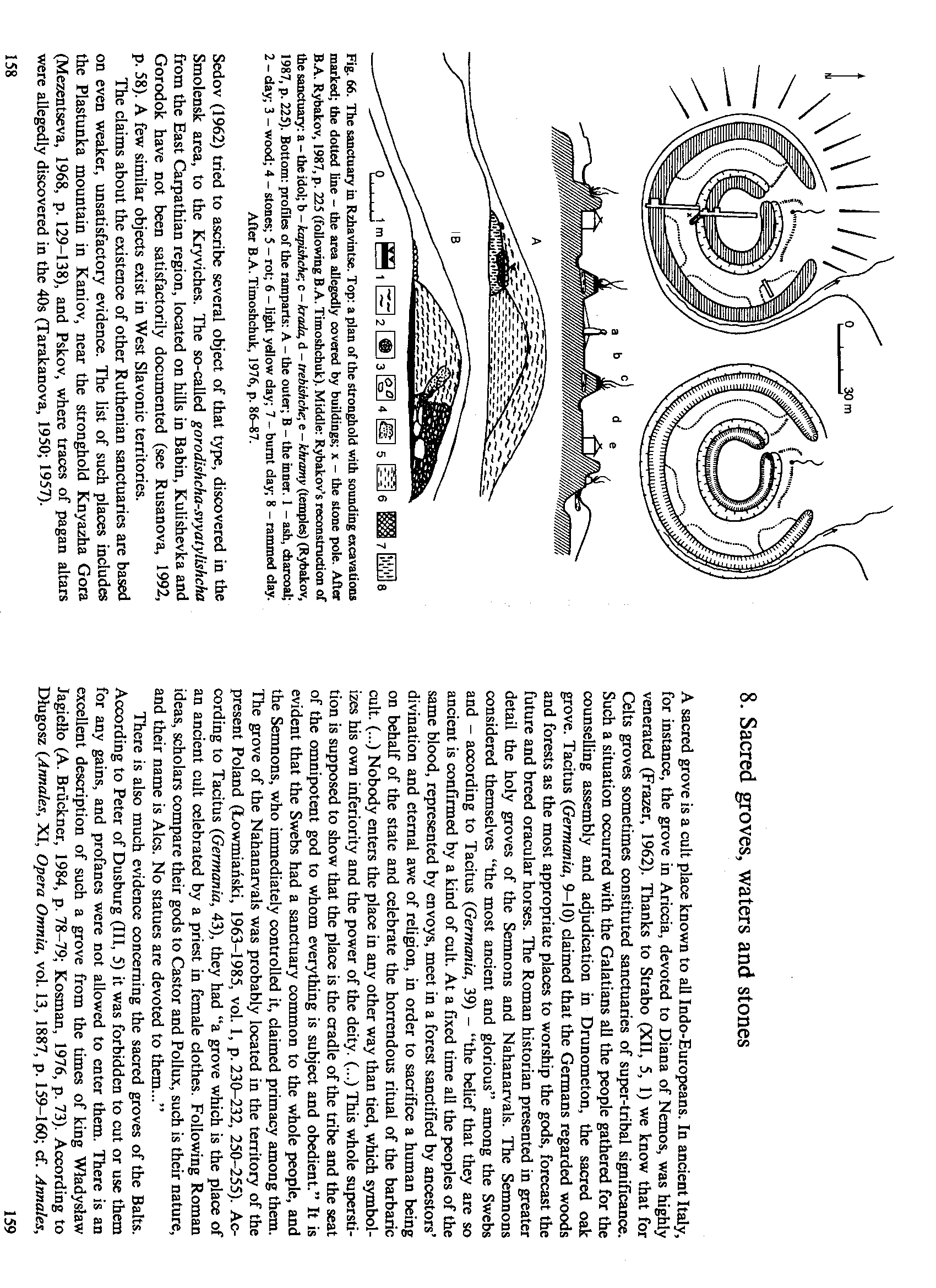

Fig. 66. The sanctuary in Rzhavintse. Top: a plan of the stronghold with sounding excavations marked; the dotted linę - the area allegedly covered by buildings; x - the stone pole. Aft er BA. Rybakov, 1987, p. 225 (following B.A. Timoshchuk). Middle: Rybakov’s reconstruction of the sanctuary: a - the idol; b - kapishche, c - krada, d - trebishche, e - khramy (temples) (Rybakov, 1987, p. 225). Bottom: profiles of the ramparts: A - the outer; B - the inner. 1 - ash, cfaarcoal; 2 - day; 3 - wood; 4 - Stones; 5 - rot; 6 - light ydlow day; 7 - burnt day; 8 - rammed clay.

After BA. Timoshchuk, 1976, p. 86-87.

Sedov (1962) tried to ascribe several object of that type, discovered in the Smoleńsk area, to the Kryviches. The so-called gorodishcha-svyatyłishcha from the East Carpathian region, łocated on hills in Babin, Kulishevka and Gorodok have not been satisfactorily documented (see Rusanova, 1992, p. 58). A few similar objects exist in West Siavonic territories.

The claims about the existence of other Ruthenian sanctuaries are based on even weaker, unsatisfactory evidence. The list of such places includes the Piastunka mountain in Kaniov, near the stronghold Knyazha Góra (Mezentseva, 1968, p. 129-138), and Pskov, where traces of pagan altars were allegedly discovered in the 40s (Tarakanova, 1950; 1957).

8. Sacred groves, waters and stones

A sacred grove is a cult place known to all Indo-Europeans. In ancient Italy, for instance, the grove in Ariccia, devoted to Diana of Nemos, was highly venerated (Frazer, 1962). Thanks to Strabo (XII, 5, 1) we know that for Celts groves sometimes constituted sanctuaries of super-tribal signiflcance. Such a situation occurred with the Galatians all the people gathered for the counselling assembly and adjudication in Drunometon, the sacred oak grove. Tacitus (Germania, 9-10) claimed that the Germans regarded woods and forests as the most appropriate places to worship the gods, forecast the futurę and breed oracular horses. The Roman historian presented in greater detail the holy groves of the Semnons and Nahanarvals. The Semnons considered themselves “the most ancient and glorious” among the Swebs and - aocotding to Tacitus {Germania, 39) - “the beiief that they aie so ancient is confirmed by a kind of cult. At a fixed time all the peoples of the same blood, represented by envoys, meet in a forest sanctified by ancestors’ divination and etemal awe of religion, in order to sacrifice a human being on behalf of the State and cełebrate the horrendous ritual of the barbarie cult. (...) Nobody enters the place in any other way than tied, which symbol-izes his own inferiority and the power of the deity. (...) This whole supersti-tion is supposed to show that the place is the cradle of the tribe and the seat of the omnipotent god to whom everything is subject and obedient.” It is evident that the Swebs had a sanctuary common to the whole people, and the Semnons, who immediately controlled it, claimed primacy among them. The grove of the Nahanarvals was probably located in the territory of the present Poland (Łowmiański, 1963-1985, vol. 1, p. 230-232, 250-255). Ac-cording to Tacitus {Germania, 43), they had “a grove which is the place of an ancient cult celebrated by a priest in female clothes. Following Roman ideas, scholars compare their gods to Castor and PolIux, such is their naturę, and their name is Alcs. No statues are devoted to them...”

There is also much evidence concerning the sacred groves of the Balts. According to Peter of Dusburg (III, 5) it was forbidden to cut or use them for any gains, and profanes were not allowed to enter them. There is an excellent description of such a grove from the times of king Władysław Jagiełło (A. Bruckner, 1984, p. 78-79; Kosman, 1976, p. 73). According to Długosz {Annales, XI, Opera Omnia, vol. 13, 1887, p. 159—160; cf. Annales,

159

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

image090 Fig. 73. The alleged sanctuary on Bogit mountain. The stronghold. The cult circle. The alle

image042 Fig. 18. The topography of the early-raedjevaj Wolin. A - the presumed location of the temp

image047 Fig. 22. The location of the stronghold in Gross Raden. 1 - the stronghold in Gross Grónow;

image049 1 m Fig. 26. The profile and plan of the remains of Ihe south-ea&tem wali base of the t

image083 Fig. 67. The enthroning ceremony of a Carinthian prince on an engraving from Osłerreichisch

image089 Fig- 71. The stoi»e walls around the peak of Góra Dobrzeszowska. 1 - the internal wali; 2 -

image094 Fig. 75. The Krak Mound near Cracow. Photo L. Słupecki. is banished, and as the małe linę i

image017 Fig. 10. The plan of the stronghold m Arcona reconstructed by H.Berlekamp and J.Herrmann. A

image056 Fig. 40. Stara Kourim. A large hall building. A - a plan; B - a profile of the wali constru

image064 Fig. 49. The alleged cult circle at Parsteiner lakę near Pehlitz. K - the drcle; R - ruins

image077 Fig. 64. Gniloy Kut near Grodek Podolsky. A plan and profile of ”the cult yard” or altar. 1

pies t ©Fold in half to ©Fold in the dotted linę ©Fold in the make crease and

012(1) 2 Name_ _ SkiB: Tradng curved Imes Follow the dotted linę and help the rocket get back to ear

015(1) Name_ _ Skill: Follcwing a mażeFolio w the dotted linę to help the snail get to the flowers.

Skill: Tradng straight lir>esName_Tracę the dotted linę to get the splder to his web. ©1995 Kelle

więcej podobnych podstron