image088

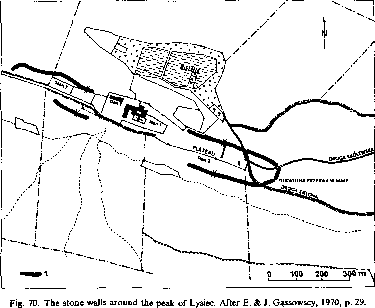

Poland.” The central position of the mountain was even morę profoundly stressed by Marcin Kromer (Polonia, I, 1589, p. 484), who claimed that Łysieć was situated in the middle of Little Poland (cf. Derwich, 1992, p. 21-22). The mountain is symbolically identified with Calvary (Golgotha), because of the relics of the Holy Cross, the Christian cosmic tree, possessed by the monastery sińce the 14th c. (Rutkowska-Płachcińska, 1987; Derwich, 1992, p. 438). A sanction of sacrum for such an identiflcation was found. In the vision of St Emeric, recorded in Powieść rzeczy istey (this motif is present also in Długosz and other sources, cf. Derwich, 1992, p. 238-260), which allegedly inspired him to handle the relics of the Holy Cross to the monastery, an angel tells him: “You should know that on the mountain called Golgotha, which translates as Łysa Góra, the Saviour suffered on the cross, which was blessed with His blood, and it is the same which you bear on your chest. Therefore, on behalf of God I tell you to bring the wood of the Holy Cross to the monastery on Łysa Góra” (Słupecki, 1991, p. 378-379). Such an identiflcation must have converged with the older tradition, according to which Łysieć was regarded as the central point of Poland or a part of Poland. Probably Łysieć was not transformed into Holy Cross by coincidence. Hence, Master Vincent might have located the legend-ary battle of the Poles with Alexander the Great at the foot of this mountain, through which the fight acąuired a mythical dimension in the micro-cosm organized around the peak.

Powieść rzeczy istey lists three deities, Lada, Boda and Leli, and a tempie devoted to them. Długosz, however, does not mention any pagan rituals held on Łysieć, although he knew something about Łada, if in his “Polish pantheon” he identified a deity of this narne with Mars and devoted much space to Diana, who, according to Powieść rzeczy istey, ruled the Łysieć castle. After A. Bruckner, we should probably classify the trinity from Łysieć as a construct of an erudite, modelled after the original invocation of the monastery, and ąualify it as a late tradition, echoed in the Polish Olympus created by Jan Długosz. Subseąuent chroniclers of the monastery added further names to the list. Wojciech Rufin (1611, card 174), misinter-preting the chronicles of Joachim Bielski (1597, I, p. 51) and Maciej Miechowita (II, 2, 1521, p. 24), eąualled Boda and Leli with Castor and Pollux, providing them with a mother, Łada, identified with Leda. Marcin Kwiatkiewicz (1696, p. 1-17) enlarged the original trio from Powieść rzeczy istey with Pogoda (Weather) and Gwizd-Pogwizd (Whistie), drawn also from Miechowita. The only part of Powieść rzeczy istey that withstands criticism is the very core of tradition, i.e. the conviction that Łysieć was a pagan sanctuary. It is confirmed by an excellent description of pagan relicts in the merrymaking organized in front of the monastery on Whitsun, when during a fair “trumpets, drums and whistles and other musie played, dances and merry capers and other [enjoyment] took place; besides there were many cases of theft, murder and other crimes and disturbances.” In 1468 king Casimir Jagiellon at the abbot’s wish forbade to hołd this fair, which - as was stressed - had not been confirmed with any privilege (Kodeks dyplomatyczny Polski, 1858, vol. 3, no. 222, p. 444-446; cf. Wojciechowska, 1991; differently in Derwich, 1992, p. 272, 488-489).

There is, however, a tentative proof of the existence of some statues on Łysieć. Drzewo żywota z raiu (The tree of life from the paradise) by Jacek Jabłoński (1735, p. 10) supplements the motives presented above with the following information: “in the year 1686, picking the rock at a side in front of the Church door [they] incidentally found a place or a bed in which an old Idol in coals rested.” The information about that flnd has been often ąuoted from Niemcewicz’s (1858, p. 11-12) relation of his joumey to the Cracow region in 1811, which is evidently based on Jabłońskfs text. Another possibility is that the sculpture was of Christian provenance. In view of the vivid tradition of Łysiec’s pagan past, each statuę found in the ground, if it was dilapidated, might have been taken for a confirmation of the legend about idołs. It is difflcult to guess whether the statuę resembled the stone figurę of the “Piłgrim,” standing at the road from Nowa Słupia to Łysieć, mentioned for the first time in sources in the 18th c. (Derwich, 1992,

1 - the walls.

179

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

image002 oió. The chimera was creatcd by a forcign govcrnmcnt. 017. The chimera is

image019 pantheon, called “the god of gods.” He was the only object of generał, public worship, infl

image002 (45) The Cowboys (hristmas MiradeANNĘ McALLISTERtecSPECIAL EDITION” Published by Siłhouette

screenshot 1 Hn Bootstrap CDNCurrent version WARNING: On the webpage was detected morę than one vers

image003 (89) The Cowboy s Christmas MiradeANNĘ McALLISTERSpecial edition" Published by Silhoue

maze l 3 BRAVE KID MAŻE - LARGENAME:_HELP JOE FIND HIS PATH TO THE MOUNTAIN HUT. for morę printables

THEWARSAWINSTITUTE REVIEW ST US Presidential Election from the Perspective of Poland and Centra

Spis treści 9 Małgorzata Dolata, Competitive position of East Poland rural areas from the point of v

image001 (From The Geography of Calamity: Geopolitics of Humań Dieback, by J. Holdren) Attributable

image001 .. the beglnning was cruclal. Survival was mora than a matter of plant-anlmal balartce

image001 Till the end of tłme

image002 "Poul Anderson, always a master of science f iction, here delivers THE BEST OF HIS MAN

image002 ORBIT 4 The latest in a unigue. up to-the minute series of SF arC thologies. ORBIT 4 is “A

więcej podobnych podstron