New Forms Taschen 165

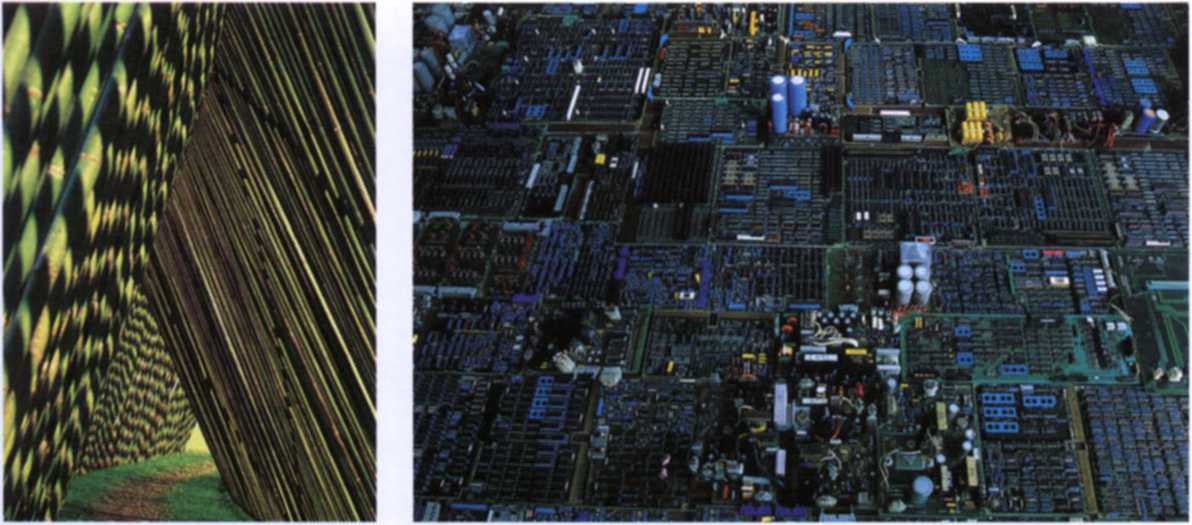

Bottom lefr Hiroshi Teshigahara Tca Ceremony Numazu, Japan. 1992 Using his favonte materiał, bamboo, Teshigahara excels in the creation of unusual environments, which in this case created a ceremonia! path between tea houses designed by architects Tadao Ando, Arata Kozaki and Kiyonori Kikutake. An ephemeral work of mstallation art, Teshigahara's bamboo calts on ancient traditions that orchestrate space, much as contemporary Japanese architec-turę does in some instances.

Bortom right Raffael Rheinsberg “Another World, Another Time," mstallation

Kamakura Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura. Japan, 1992 Using elect ronić components, this artist. born in 1943 in Kieł, evokes the view of Tokyo that he obtamed by takmg photographs of the city from the 59th floor of the Sunshine Bmldings, one of Tokyo's few skyscrapers. In this instance. art casts light on the apparent disorganization of the Japanese urban environment. by comparing it to one of the morę strictly organized technological forms of modern society.

artists in the post-war years. Some of these have not been recognized in the West because of the direct connection of their work to Japanese tradition. Others may have been underestimated. Such would seem to be the case of the sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-88), born of a Japanese father and an American mother. Noguchi's last studio, located in the town of Murę, on the island of Shikoku, is unfortunately not open to the public because of legał disputes. Hundreds of his sculptures, often looking like massive blocks of unsculpted stone, are piled and placed in the grounds of this property. Noguchi is of interest to the debate about the relationship between art and architecture because of his masterful sense of space. He brought a Japanese sense of minimal intervention, a kind of Zen spirit to contemporary art, and showed that space and form could be seen in a different way, while keeping their deep, intimate connection to the past, and indeed to naturę. Again, it will come as no surprise that members of the Japanese committee for the defense of Noguchi's work indude Ando, Isozaki and Miyake.

Japan's cities, Tokyo foremost among them, are not at all similar to their Western counterparts. The massive, sprawling vista of urban Tokyo is enough to impress even the most blasć of visitors. Morę often than not, Tokyo seems to new visitors to be a pure expression of chaos - even neighboring buildings can face in different di-rections as though intent on breaking rank and going their own way. But there are reasons for this, and apparent chaos may indeed be a different, or higher, form of organization. A German artist, Raffael Rheinsberg, born in 1943 in Kieł, seems to have captured thisin his piece 'Another World, Another Time," installed in 1993 at the Kamakura Museum. Madę with electronic components, this large work suggests that what looks disorganized may indeed be highly sophisticated, a lesson that some contemporary architects seem to have absorbed in recent years.

Three architects, two of them foreigners, have brought different approaches to a new relationship between art and architecture in Japan. I.M. Pei's 1990 Bell Tower at Misono, Shiga, for example is based in its form on a traditional Japanese musical instrument, the bachi. Built for a religious sect near Kyoto, this beli tower is one of Pei's purest and most spiritual structures.

Much less spiritual, the buildings of Shin Takamatsu, such as his Syntax located in Kyoto. are often based on an exaggerated machinę metaphor. Takamatsu's drawings, though, give an eerie presence to forms that are often anthropomorphic as well as mechanical.

Aizt ano Architecture 175

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

New Forms Taschen 089 Arata Isozaki Nagi MoCA Nagi cho. Okayama. Japan, 1992-94 This smali museum wa

69129 New Forms Taschen 059 Pages 64/6 S Hiroshi Hara Umeda Sky City Kita-ku, Osaka, Japan

New Forms Taschen 121 Makoto Se i Watanabe Aoyama Art School Tokyo, Japan. 1988-90 Like a mecha

więcej podobnych podstron