S5003995

The Celts outside Gaul

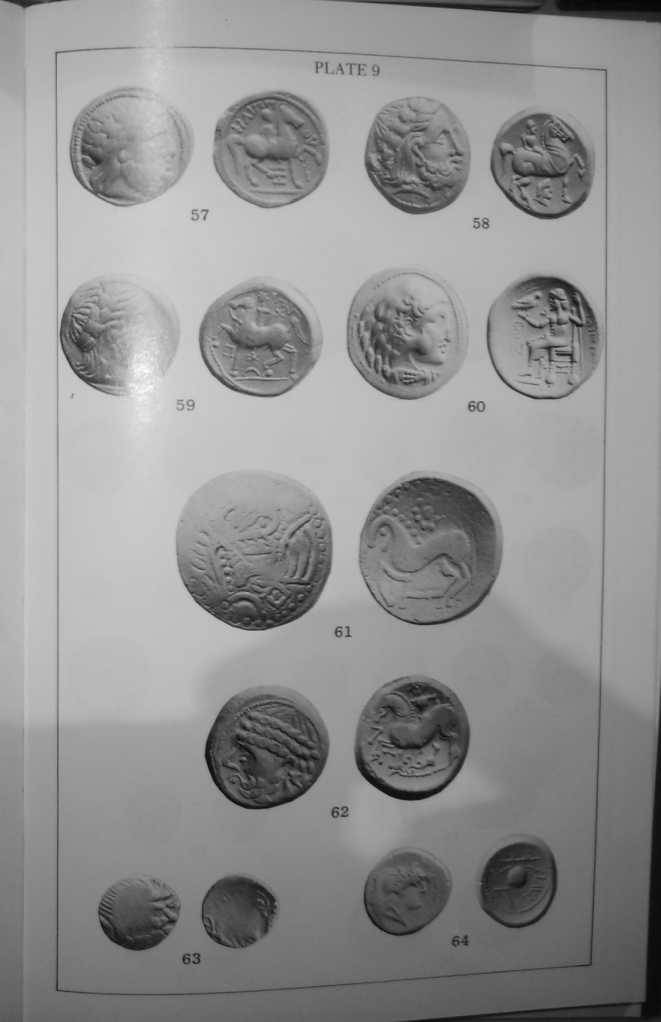

fincncss. At the same time, geographical distribution became morę dear-cut than before, and at least four important coinage areascan bedefined and correlated witb Dacian tribal blocks. This process seems to indicate that therc was a steepening of the political hierarchy, characteristic of progress towards paramount ldngship. but here under Dacian rather than Celtic overlordship.

Around 80-70 bc, traditional native coin types based on Hellenistic models were generally abandoned in favour of Roman Republican denarii and their imitations, suggesting a radica) change in the cultural climgte of-the area, perhaps related to the growing ascendancy of the Dacian king Burebista. This inaugu-rates the third and finał phase of native coinage in the Danube basin, but by now Celtic influence upon this, as upon other aspects of Danubian culture, had weakened until it was indistinguishable from the contribution madę by the local Getae and Dacians. The ascendancy of the Celts seemed to end with the waning of the meroenary connection with Macedon.

The reason why the Macedonian silver tetradrachm was preferred to the gold stater as the prototype for native coinage among the eastem Celts is unknown and mysterious, contrasting markedly with the preference of the central and western Euro-pean Celts. It may, however, have much to do with their close geographical proximity to the Mediterranean, for although during the fourth and third centuries gold coinage was struck by some of the leading Mediterranean States to pay mercenary soldiers, the normal Mediterranean currency metal and universal standard of value during the entire period with which this book is concerned was silver. It is therefore very strildng that in contrast with their compatriots inland, Celtic communities actually resident on the fringes of the Mediterranean from Languedoc to the Danube Basin all adopted silver as their principal currency metal in conformity with Mediterranean usage. This may have been in order to facilitate generał economic interchange with the adjacent Mediterranean world, for Celtic communities so located madę an important contribution to the everyday upkeep of their Mediterranean neighbours, supplying them with foodstuffs and raw materiał s as welł as with slaves and mercenary soldiers. This meant that even warrior communities must have entered into a varied rangę of commercial transactions for which a shared si1ver standard of value was undoubtedły helpful.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

S5003994 The Celts outside Gaul The earliest native coinages of Celtic Europę were usually therefore

S5003992 Chapter FourThe Celts outside Gaul By the third century bc when the first independent Celti

73016 S5004003 The Celts outside Gaul The Celts outside Gaul the Celts. They therefore struck no coi

S5004000 The Celts outside Gaul uith other Iron Age artefacts in central European graves and hoards

00444 )a588943785e7aaa29215489e95475a A Graphical Aid for Analyzing Autocorrelated Dynamical System

ly to confine itself to political processes, at the same time it ought to constitu-te the whole of s

“ WESTERN » I S P0LAND2S At the same time, Western Poland has slightly higher leve

3 7 11 We inform few competitors that we conduct negotiations with them at the same time. We organiz

its registered office in Nicosia, Cyprus, constituting 49% of the share Capital of WIRBET. At the sa

Fili your bag with coffee beans or loose tea for a gift that can be used and displayed at

CCF20100223�012 The main difference between English and Polish diphthongs, and at the same time łhe

beginning of 1970. At the same time imports passed through an entir ? administratively conditioned c

considered from a regional point of view. At the same time imports should be placed under stronger e

więcej podobnych podstron