Gardner M R Is quantum logic really logic djvu

STOR

Is Quantum Logic Really Logic?

Michael R. Gardner

Philosophy of Science, Volume 38, Issue 4 (Dec., 1971), 508-529.

Stable URL:

http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28197112%2938%3A4%3C508%3AIQLRL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-U

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR’s Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a joumal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission.

Philosophy of Science is published by The University of Chicago Press. Please contact the publisher for further permissions regarding the use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/joumals/ucpress.html.

Philosophy of Science

©1971 Philosophy of Science Association

JSTOR and the JSTOR logo are trademarks of JSTOR, and are Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. For morę information on JSTOR contactjstor-info@umich.edu.

©2003 JSTOR

http://www.j stor.org/ Wed Jun 11 07:16:41 2003

IS QUANTUM LOGIC REALLY LOGIC?1 2

MICHAEL R. GARDNERf

Hamard XJniversity

Putnam and Finkelstein have proposed the abandonment of distributivity in the logie of ąuantum theory. This change results from defining the connectives, not truth-functionally, but in terms of a certain empirical ordering of propositions. Putnam has argued that the use of this ordering (“implication”) to govern proofs resolves certain paradoxes. But his resolutions are faulty; and in any case, the paradoxes may be resolved with no changes in logie. There is therefore no reason to regard the partially ordered set of propositions as a logie—i.e. as embodying a criterion for soundness of proofs. Its role in ąuantum theory ought to be understood in an entirely different way.

1. Logic and Necessity. There is a sense of “necessary” according to which a sentence is a necessary truth just in case any evidence whatever would confirm it,

1. e., just in case it could never be rational to abandon belief in its truth. The laws of logie are surely the prime candidates for necessity in this sense. If it could be shown that we already possess good grounds for abandoning some of the standard logical laws, they would be debarred from candidature for necessity. It would then become doubtful that any sentences at all are ąualified aspirants for that lofty status. Some physicists and philosophers have in fact suggested that certain ąuantum-mechanical paradoxes have refuted the distributive laws, and that ąuantum theory ought therefore to embody a nondistributive logie. Their claims seem to support Quine’s famous suggestion [24] that the laws of logie are not necessary (or “analytic”).

2. The Paradoxes. Consider the following experimental setup: x

1

2

iR

Photographic piąte

source passes through Ah and suppose the emission pattern is symmetric so that P(A1) = P(A2) = V2P(A1 V A2).

Then

P(Ai v Aa, R) = PKA, v A2) • R]/P(A! v Aa)

= P(A! • RV A2- R)/P(A1 v A2)

= • RJ/PiA, v a(2) + P(a(2 • RyPiA, v a(2)

= P(AX • RyiPUJ + P(a(2 • R)/2P(A2)

p(ai v a(2, p) = p) + v2p(a2, p).

We can measure P(A1 v a(2, P) by counting the number of photons striking P in a long time-interval and dividing by the number striking the entire screen—i.e. the number passing through either 1 or 2. Since the value oiP(Au R) should presum-ably be unaffected by closing 2, we can measure it by counting the arrivals during another interval during which only 1 is open. P(Aa, R) is measured with only 2 open. The paradox is that the values thus obtained do not satisfy the eąuation derived above (following Putnam [21]). Graphed as a function of x (the position of P) the two distributions look approximately like this:

Fig. 3

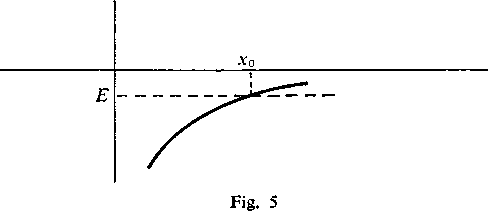

The second paradox relates to the ąuantum-mechanical phenomenon of tun-neling, or barrier-penetration. Suppose that the potential energy of a particie is a

function of position similar to that shown below:

and that a particie with total energy E less than V0 (the value classically reąuired to escape) is initially inside the well. According to ąuantum mechanics, the prob-ability is positive that the particie will later be found outside the well, even though to arrive there it must pass through a region in which its potential energy exceeds its total energy, which is impossible. The escape of alpha particles from uranium nuclei provides experimental confirmation of this result. The energy E of the escaped particles may be measured in the region F ~ 0 (where E — the kinetic energy) and the paradoxical relation E < V0 thereby verified (cf. Reichenbach [27], p. 165).

The last of our initial set of paradoxes is due to Heisenberg ([10], p. 33). The potential energy of an atom with a single orbital electron looks roughly as follows:

F

If the system is in an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian and the eigenvalue is E, the electron presumably cannot move out beyond the point xQ at which V — E. But according to ąuantum theory, the probability is positive that the electron will be found at any arbitrarily large distance from the nucleus. In any sufficiently large sample of atoms with energy E, there will therefore be some in which the potential exceeds the total energy, just as in the second paradox.

When he first introduced the paradox, Heisenberg sought to resolve it by arguing that any measurement which could localize the electron in a region beyond x0 would introduce additional energy into the system and thereby prevent a yiolation of conservation of energy. But as Reichenbach points out in connection with ana-logous attempts to dismiss the tunneling paradox, the problem is to explain how the electron could get far enough from the nucleus to be detected by an apparatus well beyond x0—e.g. a mile away. The energy it has after it interacts has no bearing on the ąuestion of how it got to the apparatus at all.

3. Propositions and Subspaces. The proposal to adopt a nondistributiye logie for ąuantum theory was originated by Birkhoff and von Neumann [4], and has morę recently been supported and developed by such writers as Mackey, Jauch, Piron, Yaradarajan, Finkelstein, and Putnam.

Essentially, the proposal is that we postulate an imbedding (order-preserving map) of the system of “experimental propositions” of ąuantum theory into an appropriate Hilbert space. Certain relations and operations are defined for the system of subspaces and then correlated with logical relations and operations. The laws of the new logie may then be, as it were, read off from the Hilbert space. As it turns out, the analogs of the classical distributive laws,

a A (b V c)h((i a i) v (a a c)

a V (b A c) <-> (a V b) A (a v c)

are false in the system of subspaces. Accordingly, ąuantum logie differs from standard logie most conspicuously in its lack of distributivity.

The Hilbert spaces H used in ąuantum mechanics are separable, complete linear vector spaces over the complex numbers, possessing an inner product (x, y) and norm (x, x). Separability means that there is a seąuence fne H such that each vector in H is a sum of the form 2“=i anfn• Completeness means that any Cauchy seąuence of vectors of H converges (in the norm) to a uniąue vector of H. A subset M. of His a linear manifold if it is closed under addition and scalar multiplication, and a sub-space if in addition it contains any vector to which any seąuence of members of M converges. If M is a subspace, its orthocomplement M1 is the subspace containing all vectors orthogonal to all members of M. The subspaces are partially ordered by the subset relation. This ordering permits the following definitions: if {Mt} is a family of subspaces, its span Ui is the least subspace containing all the — lub {Mt}. Its set-theoretic intersection Hi is the greatest subspace contained in each of the M( — glb {Mt}. It can be shown that any subspace and its orthocomplement span the entire space. The set L of subspaces of H forms a complete lattice: i.e. it has a maximal and a minimal element, and Ut and f)i exist for all sub-sets {M(} of L.

The ąuantum-logical operations are not defined truth-functionally, as in standard and even Reichenbachean (three-valued) logie, but in terms of a relation ©, to be defined later, which is a partial ordering of certain formulas. The atomie for-mulas are expressions of the type “A = a” or “A e E,” where A is an observable, a is a real number, and £ is a half-open interval on the real linę. The formulas are thought of as predicates of ąuantum-mechanical systems. “py = 6” is true of the system S iff the y component of S's momentum is 6. Two formulas are equivalent iff they bear © to each other. The equivalence classes of formulas are called ‘(experimental) propositions’ by ąuantum logicians, and the formulas they contain are their names. They might better be called ‘properties’, sińce they are classes of predicates rather than of sentences.

Using schematic letters in place of formulas, we can define an ordering <, called implication, of the propositions:

P < q =aetY © V-

Since propositions are equivalence classes of formulas, mutual implication of propositions is actually identity:

P = q = (P < q and q < p).

The disjunction V f pt of a class of propositions is its least upper bound, and the con-junction Ai Pi is its greatest lower bound. We assume that these bounds always exist. It follows that there is a proposition, called ‘I’, which is implied by every other, and one, called ‘0’, which implies every other. (‘0’ is also used to denote the sub-space consisting solely of the zero vector.) We assume there is an operation ‘ — ’ satisfying the usual properties of negation:

— —a = a — a A a = 0 a < b = —b < —a.

We can now describe the imbedding h of the ąuantum propositional calculus into the lattice of subspaces. We begin with the propositions which assert that an observable has a particular value: A — a. If a is not an eigenvalue of A, even if it is in the (continuous) spectrum of A, h(A — a) = 0. If a is an eigenvalue of A cor-responding to a single eigenvector h(A = a) is the one-dimensional subspace {aji | c complex}. If a corresponds to several eigenvectors, h(A = a) is the span of them all. h(A e (c, b]) = the rangę of the operator (Eb - Ec), where {Ex} is the spectral family corresponding to A (Jordan [12], p. 42).

We proceed recursively to define the imbedding for molecular propositions:

KViPd = UiKpd h(AiPi) = Di Kpd K~p) = KpY-

For reasons to be explained later, we postulate that h is order-preserving:

a < b s h(a) c h(b).

It follows that

h( 0) = 0 h{ 1) = H.

A proposition equal to 1 — i.e. correlated to H — is said to be a logical truth. 0 is said to be logically false.

In its formal structure, quantum logie is in some respects similar to standard logie. For example, by definition of the connectives,

P A q < p,

and

p <py q.

Since h(p v — p) — h(p) \J h{—p) — h(p) u h(p)1 = H,

p\/ -p = 1,

i.e. p V —pisa logical truth. It is now easy to see, however, that ąuantum logie is nondistributive. For let H be a two-dimensional Hilbert space, and let N — h(ss — ft/2), M = h(sx — ft/2), Ml = h(sx = —ft/2), where s* and sz represent com-ponents of spin. Now

N n (M u Ml) = NnH = N,

whereas

(Nn M) u (Nn M1) = 0 u 0 = 0.

The order-preserving character of the imbedding implies that

ss — fij2 A (sx = ft/2 vs,= —fi/2)

i= (sz = fi/2 A sx = ftj2) v (sz = ft/2 As, = —fi/2).

There is no ąuestion, then, that if we postulate a logical structure imbeddable into the subspaces of a Hilbert space, it will be nondistributive. The only ąuestion is whether we have reason to do so. We will shortly be considering the reasons offered by Jauch, Finkelstein, and Putnam. One of the difficulties in evaluating their arguments, however, consists in understanding exactly what the proposal is. It is formulated in terms of a relation <, (or ©), which is called “implication,” but in a sense which is simply left unanalyzed by many of the writers we are considering —e.g. Varadarajan [28] and Piron [18]. This in itself suggests that ‘a implies b' in the ąuantum propositional calculus is to be taken in the ordinary sense—i.e. as truth of ‘a => b’ under all interpretations by means of truth-tables. But this notion of implication obviously presupposes standard truth-functional logie, and yields a & b and a or b—in the ordinary truth-functional senses—as glb {a, b} and lub {a, b}. It therefore effects no revision in logie at all. Jauch ([11], p. 74) claims to be using a somewhat weaker notion of implication—“whenever a is true, b is true, too.” That is, “for any system S, if the proposition a is true of it, so is the proposi-tion b.” But this version is objectionable for the same reason as the previous one. a & b—again in the ordinary sense—is obviously a lower bound, in Jauch’s ordering, of {a, b}. Further, if whenever c is true of S, so is a and so also is b, then so is a & b. Hence, c < a&b. Hence, a & b = glb {a, b). Again, we get no revision in logie.

David Finkelstein [7] has contributed greatly to the clarification of the relevant notion of implication. He suggests that “the relation of inclusion [or implication] A<=- B ... simply means that every source of members that all can pass the test A (as determined by sampling and physical induction) also provides a population which passes [i.e. can or would pass] test B (as determined the same way).”

Finkelstein construes implication as a relation between properties, which in turn he construes as certain classes of sources and detectors of systems possessing those properties. However, to facilitate comparisons with other writers, we will continue to view properties (“propositions”) as equivalence classes of formulas. ‘The test A' in Finkelstein’s definition must then, of course, be read ‘any test to determine whether or not the proposition A is true of a system.’

We can illustrate the properties of the operations defined in terms of Finkel-stein’s implication by means of a few examples. That the logically false proposition 0 implies every proposition means, on this interpretation, that if all of a source’s product would pass a test to determine if 0 is true of it, then it would all pass any other test. (This can be true only if such a source has no product—i.e. only if nothing passes a test for 0.) Similarly, that every proposition implies 1 simply means that all of the product of any source would pass a test for 1. Retuming to our spin example, if a proposition C is a lower bound for {sz — fi/2, sx = hj2}, then any source all of whose product would pass a test for C produces systems which all would pass a test for ss = h/2 and which all would pass a test for sx — h/2. But it is known experimentally that there are no such sources—except, of course, those which produce nothing. Hence, nothing passes a test for C—i.e. C = 0. Accordingly, 0 is the only, and therefore the greatest, lower bound for {ss = fi/2, sx = h/2}:

(sz = h/2 A sx = h/2) = 0.

Similarly,

(ss = fi/2 A sx = -fi/2) = 0.

Suppose that some proposition D is an upper bound for this set. Then a test for D would be passed by all particles with sx = fi/2 and also all particles with sx = —fi/2. Since these are the only possible values of sx for systems of the type under consideration, a test for D is a test for 1. (Notice that sińce 1 is the proposition correlated to H, and sińce H varies with the type of system under consideration, the identity of 1 varies as well.) It follows that

lub {sx = fi/2, sx — —h/2} = (sx = fi/2 v sx = —hj2) = 1.

These results, as we saw earlier, are sufficient to yield nondistributivity.

Using Finkelstein’s definition of ‘ < ’ and our knowledge of the standard quan-tum theory, we can also explain why the imbedding of the lattice P of propositions into the lattice L of subspaces is to be expected. To each proposition p there cor-responds an observable a measurement of which is said to yield 1 if a system passes a test for p and 0 if it fails. An observable which yields only the values 1 and 0 is said to be a question. One of the postulates of quantum theory is that each observ-able corresponds to a self-adjoint operator in Hilbert space. The operator Ap cor-responding to the aforementioned question is necessarily a projection—i.e. Ap = Ap. Now every subspace corresponds to a unique projection, of which it is the rangę. Accordingly, we postulate in particular that Ap is the projection onto h(p). The rangę of Av is {</> \ (3f)(Ap<f> = 0)}. But sińce if Ap<j> = <p, then Ap2</> = Ap<p = t/j, h(p) is also the set of (equivalently, the span of) all eigenvectors of Ap with eigen-value 1: {>// \ Ap</j = 1 • <p}. Suppose, now, that p < q. Then for any device D, if all of D" s product would pass a test for p, then all of it would pass a test for q. Consider a deyice D which prepares an eigenstate </> such that Ap<fi = 1 • i/j. Then all of D's product would pass a test for p, and therefore for q. It follows that Aą<p = 1 • as well. Hence, any eigenstate of Ap with eigenvalue 1 is also an eigenstate of Aą with eigenvalue 1. Therefore, h(p) <=■ h{q). So if p < q, then h(p) <= h(q). The converse may be argued similarly: h{p) c h(q) implies that if Ap</j — l ‘ </j, then Aq</j = 1 • </j, and hence that p < q. This establishes the imbedding of P into L.

The last few paragraphs show that if we assume the standard Hilbert space for-mulation of ąuantum theory, we can show that P is imbeddable into L and that P therefore has certain properties—e.g. nondistributivity—which reflect empirical relations among tests and sources (“state-preparations,” in the terminology of [1]). But it is also possible to proceed in the opposite direction—that is, to view P as embodying these empirically known facts and then to show that these are of such a character that P must necessarily be imbeddable into the linear manifolds of a linear vector space over some field. In proving this, we increase somewhat the plausibility and naturalness of the axioms of ąuantum theory, sińce all of these axioms (in e.g. Mackey’s formulation [14]) are plausible almost to the point of triyiality, except the one which postulates an embedding of P into the subspaces of a complex, separable, infinite-dimensional Hilbert space. While no justification is known for the choice of this particular sort of space, we can at least show that there must be an embedding into the linear manifolds of some linear vector space or other.

For our purposes only a very sketchy outline of this deduction is necessary. For details see Jauch [11]. If S is a subset of a lattice L, then the closure of S under v and A is the lattice generated by S. If S generates a Boolean (i.e. distributive) lattice, all its members are compatible. Compatibility of p and q—i.e. p $ q—is equivalent to the existence of an observable B and Borel sets Ex and E2 such that

p = Be Ex and q = B e E2.

It can also be shown that p $ q is equivalent to the condition that Ap and At com-mute (cf. Mackey [14], pp. 70, 77). (These two equivalences have suggested to many that compatibility is the same as simultaneous testability, but we will follow Park and Margenau [16] in rejecting this interpretation.) Empirical study of the lattice P and its sublattices shows that only 1 and 0 are compatible with every element of P. P is therefore said to be irreducible. We assume it is a complete lattice. It is also, of course, orthocomplemented (i.e. has an operation with the usual properties of negation). A proposition implied by no other except 0 is called a point. A point may be pictured as a proposition of the form

(Ai = ćZi) A (A2 = aż) A ...,

where {Af} is a maximal set of compatible obsembles.1 Jauch’s axiom of atomicity asserts that every nonzero proposition is greater than some point and that if q is a point such that a < x < a V q, then x = aovx = a\/q. Finally, we postulate that Pis weakly modular, i.e. that

if p < q, then p $ q.

1 Observables‘^ and B are compatible iff A e Ei and B e E% are compatible, for all Borel sets Ei and E2.

On Finkelstein’s interpretation of ‘ < this axiom is quite plausible—at least if one already knows the Hilbert space theory. If p is not 0 and every eigenstate of Ap with eigenvalue 1 is such a State of Aq, then some States are eigenstates of them both. Hence, it is not implausible to suppose that Ap and Aą commute.

It is known that every irreducible, complete, atomie, orthocomplemented, weakly modular lattice can be imbedded into a projective geometry. The imbedding I preserves order: a < b iff I(a) <= I(b). It is also known that every projective geometry of dimension greater than 2 is isomorphic to the linear manifolds of a vector space over some field. Accordingly, the theory of projectiye geometries, together with Jauch’s axioms conceming P, provides a partial justification for postulating an imbedding of P into the subspaces of a complex, separable, infinite-dimensional Hilbert space, though it cannot justify the choice of this sort of space as opposed, say, to a Hilbert space over the ąuatemions.

One might or might not agree that these considerations significantly increase the naturalness of the axioms of ąuantum theory. In particular, it is doubtful that the axioms of irreducibility and weak modularity have much morę płausibility than what they derive from one’s knowledge of commuting and noncommuting opera-tors in the standard Hilbert space ąuantum theory. The second part of the axiom of atomicity also seems quite artificial. It is unclear, then, why Jauch’s excursion through the theory of projectiye geometries should be thought of much interest to the physicist. Why should he not simply postulate the imbedding into L and be done with it? In the end, that is what he has to do anyway.

4. “Logic” and Logic. We have seen that certain ąuantum theorists postulate a partially ordered set P which consists of equivalence classes of expressions of a certain kind, and which bears certain formal similarities and also certain formal dis-similarities to the standard propositional calculus. They also claim that the study of this structure increases somewhat the naturalness of the employment of Hilbert spaces in ąuantum theory. Some of these theorists, howeyer, have not been content with this modest claim, but have asserted something ąuite different about the structure of P: that it shows that ąuantum theory “is illogical, yiolates the canons of classical logie” (Finkelstein [7]), and that sińce we have empirical grounds for adopting P rather than classical logie, “logie is . .. a natural science” rather than a body of a priori, necessary truths (Putnam [21]).

In adopting this interpretation of P, with its attendant philosophical implications, Finkelstein and Putnam have madę morę explicit a view which was apparently held by Birkhoff and von Neumann in their original paper [4]. They also suggested that ąuantum theory does not “conform to classical logie,” and that ąuantum logie is “interesting from the standpoint of pure logie” in that its “naturę is determined by ąuasi-physical and technical reasoning, different from the introspectiye and philosophical considerations which have had to guide łogicians hitherto.” This com-parison between their work and that of łogicians obyiously indicates that they view ąuantum logie as an altematiye logie, in something like the ordinary sense of the term.

This interpretation is by no means the only possible one. In fact, it seems to be a minority view among the leading workers in the field. Jauch for example, writes

The propositional calculus of a physical system has a certain similarity to the corresponding calculus of ordinary logie. In the case of ąuantum mechanics, one often refers to this analogy and speaks of ąuantum logie in con-tradistinction to ordinary logie. This has unfortunately caused ... confusion.

The calculus introduced here has an entirely different meaning from the analogous calculus used in formal logie. Our calculus is the formalization of a set of empirical relations which are obtained by making measurements.... The calculus of formal logie, on the other hand, is obtained by making an analysis of the meaning of propositions. It is true ... tautologically.... Thus, ordinary logie is used even in ąuantum mechanics of Systems with a propositional calculus vastly different from that of formal logie. The two need have nothing in common. It turns out, however, that, if viewed as abstract struc-tures, they have a great deal in common without being identical ([11], p. 77).

On this view, then, ąuantum logie is logie only in a Pickwickian sense. It could less misleadingly be described as an algebraic structure, embodied in ąuantum theory, which bears certain purely formal similarities to a logie but does not function as a logie: proofs in ąuantum theory, according to Jauch, are constructed using rules of deduction specified by standard logical Systems. This is also the view of Piron:

Certain authors have wanted to see in the foregoing axioms the rules of a new logie. In fact, these axioms are only the rules of calculation and the usual logie can be applied without needing to be modified [18].

Mackey, though he does not deal with this ąuestion in his book, maintains in con-versation that his version of ąuantum theory does not embody a deviant logie. It simply begins with nine postulates concerning abstract structures, and proceeds to draw conclusions from them using the rules of deduction (and connectives) of standard logie. An examination of Mackey’s book will confirm that all of his arguments could be formalized in standard ąuantification theory.

In an unpublished talk (1970), John Stachel of Boston University remarked that ąuantum theory is fuli of misnomers: “observables,” which are not observable; “the uncertainty principle,” which gives ąuite certain information about disper-sions; “wave functions,” which have nothing to do with waves; and now “ąuantum logie,” which is not a logie but an algebraic structure bearing certain formal similarities to the standard propositional calculus: e.g.

pAq<q vs. p&q->q.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to see which of these two interpretations of ąuantum logie is correct. Nonę of the proponents of the nonlogical view of ąuantum logie has published a cogent argument for his interpretation, or even madę elear exactly what the relevant considerations are. Jauch, for example, argues that ąuantum logie expresses empirical relations, whereas logie in the true sense is based upon meaning relations. One of the philosophical ąuestions at issue, of course, is whether logie in the true sense is empirical. This ąuestion is obviously begged in Jauch’s remarks. Nor is it elear what Piron means by “rules of calculation,” or why Mackey denies that P is itself a deviant logie, granted that his theory also uses standard logie.

To decide whether the Putnam-Finkelstein view or the Jauch-Piron-Mackey view is correct—i.e. whether ąuantum logie is a logie or just a “logie”—we must first ask what a logie is. In the first sentence of what was probably the first book on logie, the Prior Analytics, Aristotle wrote that “the subject of our inąuiry.. . is demonstration” [2]. Similarly, Charles Peirce wrote that while “nearly a hundred definitions of [logie] have been given,... it will be generally conceded that its central problem is the classification of arguments, so that all those that are good are thrown into one division, and those which are bad into another” [17]. Quine has also claimed that “the chief importance of logie” lies in the techniąues it pro-vides “for showing, given two statements, that one implies the other; herein lies logical deduction” ([22], p. xvi). If Aristotle, Peirce, Quine (and other logicians too numerous to name) are right, then the crucial ąuestion in deciding whether ąuantum logie is a logie is whether Jauch et al., are correct in claiming that all inferences in ąuantum theory use standard logie; or whether, on the contrary, at least some inferences reąuire rules based upon ąuantum-logical implication. We shall return to this ąuestion shortly.

In addition to its proof-theoretic or syntactic aspect, logie also has a model-theoretic or semantic aspect. In recent writings Quine has emphasized the latter by defining logie as “the systematic study of the logical truths” [26], Perhaps, then, van Fraassen is right in saying that “a logie is a system of axioms and/or rules which characterizes the set of valid sentences and the set of valid arguments for a certain language” [8].

The task of providing a semantics is the task of defining truth, or truth under various interpretations. It may at first seem difficult or even impossible to do this for ąuantum logie. We have to express the truth conditions of the ąuantum-logical propositions in language which is antecedently understood, and yet our familiar language embodies standard logie. This difficulty becomes ąuickly appa-rent if we try to define truth in the usual Tarskian fashion. It is easy enough to stipulate that for each atomie proposition AeE,

A e E is true of a system S = In S, A has a value in E.

However, when we try to extend this by recursion to molecular propositions, we run into difficulty immediately:

x A y is true of S s x is true of S and y is true of S

is evidently incorrect, as is any other clause stated in terms of the truth-values of the conjuncts, sińce ‘ A ’ is not truth-functional. (In PutnanTs ąuantum logie, a con-junction of true propositions may be true, but may also be contradictory.)

It might seem possible to solve this problem by restricting the class of molecular propositions in such a way as to restore truth-functionality. This was von Neumann’s idea in his book ([15], p. 251), where he defined p A q and p V q only when p and q are compatible. The resulting restricted class of propositions is called Po. This move does yield truth-functionality at least of measurement results (where 1 is truth and 0 is falsity). If p and q are compatible, the proposition or ąuestion a A b corresponds to the product Ap • Aa of the projections Ap and Aq. A measurement of it therefore yields the product of the values of p and q—i.e. 1 iff the latter both are 1. p V q corresponds to the operator Ap + Aą — Aą' Ap and therefore yields 0 iff both p and q yield 0. Accordingly, it may seem possible to define truth for this restricted class of ąuestions—measured and unmeasured—in the usual Tarskian fashion.

However, this suggestion runs afoul of a recent result of Kochen and Specker [13]. In the course of a proof of the nonexistence of one kind of hidden yariable theory, they show that it is not possible to maintain both that Po is imbeddable in L and that one can assign truth-values to all the elements of Po while giving ‘ A5 and ‘ V ’ their usual truth-functional meanings. A homomorphism from Po into Z2 = {0, 1} is a map h such that for all compatible a, b e Po,

h(a V b) = h(a) + h(b) — h(a)h(b) h{a A b) = h(a)h(b)

Ki) = i.

Such a map would therefore correspond to an assignment of truth-values to the propositions in Po which accorded with the usual truth-tables for the connectives. If ‘ A ’ and ‘ V ’ have their normal meanings within Po, there should be many such mappings—one for each assignment of truth-values to all the atomie propositions. However, Kochen and Specker have proven that there is no homomorphism of P? into Z2. It follows that one cannot define truth for elements of P¥ in the Tarskian manner—using, as it does, the standard truth-functions.

Of course, there is no reason to assume that a definition of truth need be any-thing like Tarski’s. Indeed, Finkelstein’s interpretation of P$ in terms of sources and tests does suggest a definition of truth which does not presuppose truth-functionality. Suppose we begin in Tarskian fashion by defining truth for atomie propositions as follows:

A g E is true of a system S s In S, A has a value in E.

A test for A e E, of course, is then a test which would be passed by S iff A e E is true of S. We then proceed recursively as follows: a test for —p is one which would be passed by S1 iff A e S is not true of S; if p and q are compatible, a test for p W q is a least upper bound (in Finkelstein’s ordering of tests) of a pair of tests for p and for q respectively; if p and q are compatible, a test for p A g is a greatest lower bound of a pair of tests for p and for q respectively. Finally, haying defined tests for all the molecular propositions, we can say that any proposition r is true of S iff S would pass a test for r. This might seem to be the only method for defining truth in Po which accords with the empirical interpretation of the structure in terms of tests.

Surprisingly, this apparently innocent definition also conflicts with the result of Kochen and Specker. It presupposes that it is possible to say (though perhaps not always to know) of any proposition whether a test for it would yield truth or falsity. The reason predictions (correct guesses) of this sort conflict with Kochen and Specker is obvious. Suppose a test for p would yield truth. Then let h(p) = 1. If it would yield falsity, let h(p) = 0. Clearly, a test for 1 would yield truth. A test forp h q would yield truth iff tests for p and for q would both yield truth; corres-pondingly for p v q. Therefore, for all compatible a, b:

Ml) = i

h(a A b) — h(a)h(b)

h(a V b) = h(a) + h{b) — h(a)h(b).

But these are the conditions for a homomorphism of P$ into Z2, and Kochen and Specker have shown there are such mappings. The ąuestion of whether a test for a proposition would yield truth does not in generał have a uniąue answer. (As Bell suggests [3], one way of understanding this is by realizing that the answer may de-pend upon what other propositions are tested along with p.)

Another faulty ąuantum semantics—and one which seems in danger of acąuiring currency—makes Pe X“true under an assignment L (i.e. in State L) just in case L is an eigenstate of Pop, the operator associated with P, with eigenvalue in X” [6, 8]. As Reichenbach ([27], p. 95) and Popper [19, 20] have emphasized, just as any assignment of a probability to a single event is relative to that event’s member-ship in a certain reference class, the assignment of a State or wave function to a single particie is relative to its membership in an ensemble of particles similarly prepared. For example, sx = fij2 may have a probability of % relative to an atom’s emission from a diatomic molecule with a total spin of 0, and a probability of 1 relative to its emission followed by a measurement yielding sx = —ń/2 for the other atom from the same molecule [5]. The first atom will be in an eigenstate of sx relative to the latter preparation, but not relative to the former. Claiming that the truth-values of sentences about a particie are determined by its State or wave-function, then, commits one to the absurdity that these truth-values depend upon which reference class one views the particie as a member of. As is quite elear in e.g. Mackey’s book, a ąuantum State of a system is an assignment of a probability to each proposition conceming it. Now to say that the probability of a proposition is l/2 obviously leaves open the ąuestion of whether it is true. Hence, the notion that a ąuantum State determines truth-values is absurd. Essentially, it is the error of which Einstein accused Bohr: that of assuming that the State is a complete descrip-tion of a system, when it is not even a uniąue description ([19], p. 459).

In view of all these difficulties, it might well appear that if a ąuantum physicist espouses a deviant logie, there is no way we—beginning from a common sense, standard-logical perspective—could come to understand him. Quine, indeed, has claimed that the notion of understanding-someone-to-espouse-a-deviant-logic is incoherent, sińce the fact that someone has been construed to be denying standard logical laws is the strongest possible evidence that he has been misconstrued ([23], pp. 57 ff, 69). We ought rather to “impute our orthodox logie to him, or impose it upon him, by translating his language to suit” ([26], p. 82).

The feeling that lack of truth-functionality creates this sort of difficulty, however, arises from an excessively narrow conception of how the ąuantum-logical propositions can be understood. The “operational” definition of truth rejected a moment ago provides a clue to the solution to our problem. In order to move to the ąuantum-logical standpoint from the common sense one, we need not translate a molecular proposition into ordinary English by means of the sort of part-by-part correspon-dence reąuired by Tarski’s recursive clauses. We need only notę that each proposition corresponds to a uniąue ąuestion: Ae Eto the observable a measurement of which yields 1 if A e E and 0 if not; ViPi to the least upper bound of the ąuestions corresponding to the p,’s; and so on. Since even a molecular proposition corresponds to a single observable, we can State its truth conditions, not in terms of the component propositions, but simply in terms of that observable. The truth-definition for ąuantum logie, then, is quite triyial: a proposition is true of S iff the corresponding observable has the value 1 in S. What the failure of the “operational” definition shows is that “A = 1” is not equivalent to “A measurement of A would yield 1.”

With this definition of truth in hand, it is intuitively plausible that the quantum-logical characterization of logical truth ought to be as in section 3 above: a proposition is logically true iff a measurement of the corresponding question always yields 1 after any preparation—in any possible world, as it were.

Having found no objections to the semantic aspect of quantum logie, let us now look at the proof-theoretic aspect in the light of the following parody. Suppose that some of the propositions (other than 0 and 1) have proper names—‘Oscar’, Trving’, etc. Then define a relation -> over the propositions as follows :

p->q = p and q have names, and that of p is lexically prior to that of q; ot p = 0; or q = 1; or p = q-

This is a partial ordering: reflexive, transitive, antisymmetric. Further, any set has a least upper bound and a greatest lower bound. We can therefore define certain other propositions, related to p and q, as follows:

pAq = glb {p, q)

p0q = lub {p, q}.

It follows from these definitions that

pAq->q

and

p->p0q.

Let 1 be called a logical truth. Suppose, finally, that quantum theorists had some reason to be interested in <P, -»>, the propositions as ordered by e.g. because this structure turned out to be isomorphic to some other structure they are interested in, and because this isomorphism had true experimental consequences. Would it then be reasonable to say, because ‘A’ and ‘0’ obey some laws disanalogous to those governing ‘and’ and ‘or’, that quantum theory “yiolates the canons of classical logie ?” Would it be reasonable to say, because the properties of this structure have empirical conseąuences, that “logie is empirical?” And would it be any morę reasonable to say these things if we decided to cali -> by the name ‘implication’ ?

This far we have seen no morę reason to say that ąuantum logie <P, < > is a logie than we would have for saying that <P, ->> is a logie if it were somehow a ąuantum-theoretically interesting partial ordering of the propositions. What morę, beyond mere interestingness, would be reąuired to make us willing to regard <P, ->> as a logie ? Presumably, if it turned out to be a good idea to use it to govern proofs, we would not hesitate—that is, if it turned out to be a good idea to infer from any named proposition any proposition whose name is lexically later. It would, of course, be rather surprising if there were good reasons to support this proposal. It should seem comparably unlikely that there are good reasons to support the corresponding proposal for <P, <>. In view of the principal reason why some physicists and mathematicians are interested in <P, <>—viz. that there is some hope of proving that it is imbeddable in <L, <=), or at least in something like <L, c>—it would be a peculiar coincidence if it also turned out to govern some (but not all) proofs in ąuantum theory. Let us not prejudge the issue, however, but look for examples of proofs governed by < rather than standard implication.

We already have the testimony of Mackey, Jauch, and Piron that we will find no such proofs in their writings. One searches in vain for examples in the publica-tions of Varadarajan and Finkelstein. Thus, the leading physicists and mathematicians who work in what is called ‘ąuantum logie’ actually use standard logie exclusively. However, a philosopher, Hilary Putnam, building upon suggestions by Finkelstein in lectures, has claimed that they are mistaken in thus restricting them-selves. He has argued that if we construct proofs in accordance with ąuantum logie, we can avoid the two-slit and orbital-electron paradoxes [21]. (The tunnel-ing paradox, though Putnam does not mention it, can be treated in the same way.) In the second linę of our derivation of the two-slit paradox (section 2), we assumed that

{Ax v A2) A R = (Ai A R) V (A2 A R).

Quantum logie—lacking, as it does, a distributive law—enables us to błock the paradox by prohibiting the inference from the left side of this statement to the right. In our derivation of the orbital-electron paradox, we asserted that there is a positive probability that an orbital electron with energy H = E is at a certain distance Xi > x0 from the nucleus, even though V(x1) > E. But the conjunction

H = E A x = x1

is contradictory in ąuantum logie, simply because h{x = x1) = 0. Less trivially, it is contradictory even to assert that a particie with energy E has an unspecified position greater than x0. If {Ex} is the spectral family associated with position (Jordan [12], p. 43), a e (x0, oo] corresponds to E„ — EXo = 1 — EXo. The rangę of this projection is obtained by taking the set of all wave functions and making the value of each one 0 for all x < x0. Since the energy-eigenfunctions under discussion have nonzero values for x < x0, the subspace spanned by any of them intersects h(x e (x0, oo]) only at 0. Hence,

H = E A x > x0

is contradictory. The resolution of the paradox, then, consists in pointing out that the set of premises asserted in deriving it is contradictory and therefore unassert-able. The tunneling paradox may be resolved by the same remark, replacing ‘orbital electron’ by ‘alpha particie’.

Putnam ([21], p. 190) and Finkelstein ([7], p. 207) assume that each of the propositions of P—not just those about macroscopic objects—is either true or false, and that every observable has a value at every time. Putnam and Finkelstein are therefore not open to the charge that they make any arbitrary and unexplained distinction between macroscopic and microscopic levels on the score of truth-or-falsity. One might be inclined to object that they make an unexplained distinction between these two levels on the score of distributivity, sińce propositions ascribing ordinary traits to ordinary (macroscopic) objects presumably obey classical logie. But Putnam claims that “ąuantum mechanics itself explains the approximate validity of classical logie ‘in the large.”’ [21]. Perhaps in some futurę publication he will expand upon this brief remark.

His discussion of the paradoxes provides Putnam with the grounds—which are lacking in most of the literaturę in this area—for claiming not only that the struc-ture P serves to provide a partial justification for the employment of Hilbert spaces in ąuantum theory, but also that it functions within the theory as a deviant logie. It functions as a logie in that it provides a new set of propositional connec-tives, a new characterization of logical truth, and a new standard of soundness of inferences. Having cited physical experiments which provide grounds for preferring this new logie to the old, Putnam feels justified in concluding that logie is an empiri-cal science.

But let us take a closer look at his Solutions to the paradoxes. First, it is not enough simply to point out that the argument supporting the two-slit paradox uses the distributive law, which does not in generał hołd in ąuantum logie. Since dis-tributivity holds in some cases (e.g. if all the propositions involved are compatible), Putnam is obligated to show that the rules of his logie entail that, in particular, distributivity fails in the case of

(1) (Ai v A2) A R.

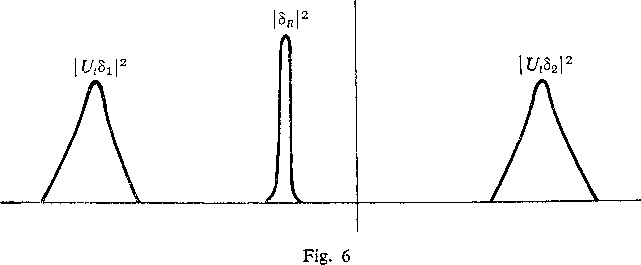

He has claimed in conversation that in order to show this, one must take into ac-count the fact that these propositions are true of an individual photon at different times. Suppose some photon passes through one of the slits at time 0 and strikes the screen at time t. In order, then, to determine the subspace corresponding to (1), he proposes that we take a basis for h(Ax v A2), the subspace assigned to Ax V Az under our earlier mapping ignoring time, and project its members forward in time using the operator Ut = e~“H. The span of the resulting vectors is the subspace corresponding to Ax V A2 when it is to be combined with a proposition which, like R, refers to time t.

A rough, qualitative argument should suffice to show that if we follow this procedurę, no failure of distributivity results. Idealizing in a way which should not affect the essential character of the results, assume that the slits are very narrow and therefore prepare approximate eigenstates Sx and S2 of position. If we apply Ut to them, they spread out somewhat. If R asserts (idealizing) that the photon arrives at a certain point on the screen, then R corresponds to the subspace spanned by an eigenstate SB localized at that point. The sąuares of these three wave functions therefore look roughly as follows at the screen:

It should be elear that one cannot obtain a function like SB by taking any linear combination (or limit thereof) of functions like and Ut82. Therefore, neither SB nor any scalar multiple of it lies in the subspace spanned by UtS1 and UtS2. Therefore, this subspace has a zero intersection with that spanned by SR. Hence,

(2) (At V A2) a R = 0.

Since SB is not a scalar multiple of either (7j8x or UtS2, At A R = 0. Hence

(At v A2) a R = (At A R) V (A2 A R).

There is an easier way to see that (2) is true. Presumably, there is no nontrivial source all of whose product passes through 1 or 2 and arrives at R. Diffraction and interference assure that photons which pass through the diaphragm are distributed over a part of the screen larger than R. But this means that the only and therefore greatest lower bound of {At v A2, R} is 0.

If this is correct, there is no failure of distributivity in the two-slit paradox. It therefore provides no support for rules of deduction prohibiting distribution. (The result (2) that it is contradictory to say that a particie went through either 1 or 2 and arrived at R is another unwelcome conseąuence of PutnanTs version of ąuantum logie.)

A second objection to the logical interpretation (i.e. deductive use) of ąuantum logie must be offered only conditionally, sińce the details cannot be argued here. It is addressed only to those readers who agree with Park and Margenau [16], Popper [19, 20], and Ballentine [1] on the following thesis:

The uncertainty principle does not imply that x = 3 and px = 5 cannot both be shown experimentally to be true of system S at time t; and furthermore, any version of ąuantum theory which did have such a conseąuence would be empirically false.

The objection is that in view of this thesis, there is no motivation for holding that x = 3 A px = 5 is unassertable—i.e. either undefined or contradictory—for it can in fact be shown experimentally to be true. Since the embedding of Pinto L has the immediate conseąuence that

(3) (x = 3 A px = 5) = 0,

and sińce Putnam and Finkelstein interpret this statement as asserting that these two propositions cannot both be true of S at t, the ąuantum-logical version of ąuantum theory is false on the Putnam-Finkelstein interpretation.3 It is therefore obviously unsuitable for the resolution of the three paradoxes of section 2.

It is important to realize that these objections to viewingP as a deviant logie are by no means intended to establish that the structure is without interest—i.e. that it has no role to play in ąuantum theory. We have already observed that it serves to express certain surprising facts in a striking notation, and that the use of this notation provides a partial justification for the only nontrivial ąuantum-theoretic axiom. Nor are the above arguments intended to deny, for example, that (3) is true. For that statement is merely a deviant notation for the assertion,4 using standard logie, that there is no source whose product all would pass a test for x = 3 and all would pass one for px = 5. We have simply argued that it is a mistake to interpret this empirical generalization about sources as a meta-assertion to the effect that it is contradictory to say that both x — 3 and px = 5 are true of a given system. The impossibility of all of a source’s product having both these properties does not imply the impossibility of some of the product’s having both. To adopt the Putnam-Finkelstein interpretation is to be overly impressed by the formal resemblance of (3) to

x — 3&px = 5<-^p & —p.

In sum, <P, <> ought to be viewed as a partial ordering of the propositions, which is of interest because of its embedding into <L, >, and not as a deviant logie.

The essential reason is that a logie governs the construction of proofs, and we have seen no reason to construct any proofs in accordance with the partial ordering <.

This rejection of a nondistributive logie for ąuantum theory leaves us with some unfinished business, however: the unresolved paradoxes of section 2. Solutions which involve no change in logie will be the subject of the next sections.

5. The Two-slit Paradox Reconsidered. In section 2 we presented the arguments allegedly sustaining our original three paradoxes somewhat uncritically, without raising objections which might have been appropriate. In these sections we will re-examine these arguments to see if there are reasonable ways to avoid their conclu-sions without modifying our logie. If such ways do exist, we shall almost certainly want to adopt them, because of Quine’s “maxim of minimum mutilation” ([26], pp. 7, 86,100; [23], p. 20). The maxim is that when we have to choose among alter-native revisions in a theory to account for unexpected observations, similarity of a new theory to the old counts heavily in its favor. One way to avoid unnecessarily radical revisions is to abandon the less generał beliefs used in deriving the false prediction. If we find a white raven, we abandon ‘Ali ravens are black’ rather than ąuantification theory, which applies to our entire world-theory and ought not to be held responsible for this failing of the biological part of it.

With these considerations in mind, let us look again at the two-slit paradox. The assumption that each photon always has a location and follows a definite trajectory through one slit or the other, using ordinary logie and probability theory, implies that the intensity at R is given by

1AP{A1, R) + V2P(A2, R).

Putnam claims that this expression is false, and that some revision is therefore needed in the transformation rules used to derive it. But how does he know it is false ? The two-slit experiment itself determines the total probability P(A1 v A2, R) and not the separate probabilities P(Ait R), i = 1,2. Apparently, the only way we can determine the results of passage through one slit is by closing the other. But how do we know P(AU R) is the same whether or not slit 2 is open? Do not the experimental results constitute a refutation of this very assumption? Why should we mutilate the elegant, efficient, and familiar logie of truth-functions and ąuanti-fiers rather than give up the intuitive prejudice that probabilities relative to passage through one slit should be unaffected by closing the other ? It is certainly surprising that this dependence should exist, but it is not unintelligible. Presumably, no ąuantum theorist would accept the maxim never to assume that microscopic particles do anything surprising. In any case, we are not unfamiliar with trajectories influenced by distant objects—as in gravitation, for example. Two-slit interference is not, after all, an instance of the gross sort of nonlocality encountered in the EPR paradox [5], where the event (j* acąuiring a value) occurs in precisely the same way regardless of the distance to its cause. As slit 2 is moved farther away, its effect on P(Alf R) becomes less and less. In this respect, interference is a great deal like gravitation.

Though initially puzzling, this effect is explainable, in the sense that it follows (by standard logie) from the axioms of ąuantum theory together with certain initial conditions. It is therefore as well explained as any other ąuantum phenomenon— e.g. the decay of excited atomie States. If we do not demand, in addition to the transition probabilities which ąuantum theory provides, a precise description of the forces caused by the nucleus and acting on individual orbital electrons, we should not demand a description of the forces caused by the opening of slit 2 and acting on individual photons at slit 1. Quantum theory is adeąuate to explain the two-slit experiment to the extent that such phenomena can be explained—i.e. statistically.

6. The Energy Paradoxes Reconsidered. In the derivation of the orbital-electron paradox (section 2), it is assumed that if the system is in an eigenstate of H with eigenvalue E, then w(H)—the value of H—is E, and that

(*) E= w(H) = + W{vCr)).

From this follows the false proposition that \\r\\ cannot be so large that w(V(r))

exceeds E. But, sińce p2 and V(r) do not in generał commute, (*) is an instance of the assumption which Bell [3] criticized von Neumann for attributing to hidden variable theorists—the assumption that the value of the sum of two noncommuting observables must be eąual to the sum of their separate values. We measure the energy levels of atoms by spectroscopic analysis of their radiation, for example, and certainly not by measuring simultaneous values of p and V(r) and combining them according to (*). There is therefore no a priori reason to expect that their values should be related to E by (*)• The orbital-electron paradox should be regarded as a refutation of (*) rather than of standard logie, in keeping with the principle of minimum mutilation.

An additional example may help make it clearer that in ąuantum theory the values of energy, momentum, and potential do not bear the relations they have in classical physics, as is asserted by (*)• The Hamiltonian of a one-dimensional harmonie oscillator is H — p2/2m + y2kx. The eigenvalues of H are En = (n + Yz)h. If in the nth energy eigenstate the only possible values of p2jlm and of l/2kx were those whose sum is En, then the system would be confined to an ellipse in the p — x piane. However, the eigenfunctions of the harmonie oscillator are Hermite functions, which have nonzero values for nearly all values of p (or of x). Therefore, values of p (or x) are possible which do not accord with (*)•

The tunneling paradox has less support than that of the orbital electron. Since it does not assume that the system is in an eigenstate of H, it must instead assume that the sum

5 = w{Q+ w(v(7))

is conserved. This ąuantity is measured after the escape of an alpha particie (i.e. when V(r) ~ 0), and it is assumed that it had the same value s0 when it was in the region where w(V(r)) > s0, which is impossible. However, the conservation of the sum of the values of kinetic energy and the potential is not a theorem of ąuantum theory. The theory does imply constancy of the expectation value of H, but says nothing about s. We are, therefore, free to deny that s is constant. In fact, the role which potentials play in ąuantum theory indicates that we should not expect con-servation of s. If the acceleration of a particie of mass m were given by

(**) a = —- V V(r), m

then it would be a theorem that s is constant (e.g. Goldstein [9], pp. 3 f.). A theory which assumed (**) would, of course, be classical and not ąuantum mechanical. In ąuantum theory, some particles approaching a barrier described by V(r) are reflected and some are transmitted. V(r) certainly, then does not give the accele-rations of individual particles. We therefore have no reason to expect the sum of its value and that of the kinetic energy to be conserved.

7. Conclusion. We have seen that the two-slit, orbital-electron, and tunneling para-doxes are based upon intuitive prejudices and mistakes, rather than assumptions within the ąuantum theory proper, and that it is evidently better to correct these than revise our logie. It remains, however, to assess the relevance of all of this to Quine’s critiąue of necessary truth. After examining (too briefly) the alleged ąuantum-theoretical utility of three-valued and nondistributive logics, Quine remarks:

The merits of the proposal may be dubious, but what is relevant just now is that such proposals have been madę. Logic is in principle no less open to revision than ąuantum mechanics or the theory of relativity ([26], p. 100).

Quine is certainly right in suggesting that the technical demerits of these particular proposals leave open the ąuestion of whether logie is empirical. However, it is unclear why Quine thinks (as he appears to here) that the mere fact, that proposals to revise logie for empirical reasons have been madę, is adeąuate to establish that such proposals are at least coherent—i.e. to establish that logical laws are confirmed or disconfirmed through the role they play in a total scientific theory, and are therefore open to revision when the theory conflicts with experimental fact. What does establish this latter thesis, however, is simply that there is no intelligible alternative, as Finkelstein argues in conversation.

If Quine is right in claiming that it is unintelligible to say that our knowledge of logical laws derives from their meanings or from conventions or semantical rules ([24]; [25], pp. 71-125), then there is no justification for driving an epistemological wedge between logical truths and other truths. That is, there is no alternative to saying that logical laws, like natural laws, acąuire empirical warrant when the total scientific theory is experimentally corroborated, and that accordingly, they may be altered in order to improve the empirical success of the theory. While Putnam has failed to support this thesis by actually producing good empirical reasons to revise logie, the thesis that such reasons could in principle exist is strong enough to stand on its own.

REFERENCES

[1] Ballentine, L. E. “The Statistical Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.” Reoiew of Modern Physics 42 (1970): 358.

[2] Basic Works of Aristotle. Edited by R. McKeon. New York, 1941.

[3] Bell, J. S. “On the Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics.” Review of Modern Physics 38 (1966): 447.

[4] Birkhoff, G. and Neumann, J. von. “The Logic of Quantum Mechanics.” Annals of Mathematics 37 (1936): 823.

[5] Bohm, D. Quantum Theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1951.

[6] Fine, A. “Some Conceptual Problems of Quantum Theory.” Pittsburgh Series in Philoso-phy of Science 5 (1972).

[7] Finkelstein, D. “Matter, Space, and Logic.” Boston Studies in Philosophy of Science 5. Edited by V. R. Cohen and M. Wartofsky. Dordrecht, 1970.

[8] Fraassen, B. C. van. “The Labyrinth of Quantum Logics.” Unpublished. University of Toronto.

[9] Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics. Reading, Mass., 1959.

[10] Heisenberg, W. Physical Principles of the Quantum Theory. Translated by C. Eckart and F. Holt. New York, 1930.

[11] Jauch, J. M. Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. London, 1968.

[12] Jordan, T. F. Linear Operators for Quantum Mechanics. New York, 1969.

[13] Kochen, S. and Specker, E. P. “The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics.” Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 17 (1967): 59.

[14] Mackey, G. The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. New York, 1963.

[15] Neumann, J. von. The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Translated by R. Beyer. Princeton, 1955. (German ed., 1932).

[16] Park, J. L. and Margenau, H. “Simultaneous Measurability in Quantum Theory.” International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1 (1968): 211.

[17] Peirce, C. “Logic.” In Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology. Edited by J. Baldwin. New York, 1925.

[18] Piron, C. “Quantum Axiomatics.” Hehetica Physica Acta 37 (1964): 439.

[19] Popper, K. R. Logic of Scientific Discocery. New York, 1965. (German ed., 1934).

[20] Popper, K. R. “Quantum Mechanics without ‘the Observer’.” Quantum Theory and Reality. Edited by M. Bunge. New York, 1967.

[21] Putnam, H. “Is Logic Empirical?” Boston Studies in Philosophy of Science 5. Edited by V. R. Cohen and M. Wartofsky. Dordrecht, 1970.

[22] Quine, W. V. Methods of Logic. New York, 1959.

[23] Quine, W. V. Word and Object. Cambridge, Mass., 1960.

[24] Quine, W. V. From a Logical Point of View. New York, 1963.

[25] Quine, W. V. Ways of Paradox. New York, 1966.

[26] Quine, W. V. Philosophy of Logic. Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1970.

[27] Reichenbach, H. Philosophic Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Berkeley, 1944.

[28] Yaradarajan, V. S. Geometry of Quantum Theory, Princeton, 1968.

•-

Light source

Diaphragm Fig. 1

Let P(A{, R) be the probability that a photon which passes through slit i (i = 1, 2) strikes the smali region R. Let P(At) be the probability that a photon emitted by the

Received January, 1971.

t Present address: Dept. of Philosophy, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Ma. This paper is based upon part of a Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1971.1 wish to acknowl-edge helpful conversations with Jeffrey Bub, Imre Lakatos, Sir Karl Popper, Hilary Putnam, Abner Shimony, and Lawrence Sklar.

Actually, (3) is trivially true, simply because each conjunct is 0. But points corresponding to those in this paragraph and the next may also be madę about propositions of the form x e (3 — e, 3 + e] and px e (5 — 8, 5 + 8], where e • 8 < 6/2. In the momentum representation, px e (5 — 8, 5 + 8] corresponds to the operator which reduces each wave function to 0 outside the interval (5 — 8, 5 + 8] and leaves it otherwise unchanged. Each of the functions in the rangę of this operator has a dispersion in px which is < 8. By the uncertainty principle, the Fourier transforms of these functions will have dispersions > 6/28. The transforms com-prise h(px e (3 — 8, 3 + 8]) in the position representation. h{x e (3 — e, 3 + e]) is a set of wave functions reduced to 0 outside (3 — e, 3 + «]. Each of them has a dispersion < e. Hence if e < 6/28, nonę of them is in h(px e (5 — 8, 5 + 8]), and

X s (3 — e, 3 + e] A px e (5 — 8, 5 + 8] = 0.

That some statements using this alleged deviant logie are notational variants of statements using standard logie provides support for Quine’s thesis that “the deviant logician’s predica-ment” is that “when he tries to deny the doctrine he succeeds only in changing the subject”

[26].

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Synthese Library 409 Studies in Epistemology, Logic, Methodology, and Philosophyof Science Paweł

image002 Brian Aldiss is one the most influential -and one of the best - SF writers Britain has eve

image002 ORBIT 8 is the latest in this unique series of anthologies of the best new SF. Fourteen sto

00039 ?0994c0b89c0edd69cbdfecf717cc9b 38 Molnau OPS5 (Official Production System, Version 5) is a w

00059 ;51d879c0dc447efbe08f5c4c0bfdc0 58 Hembree & Zimmerx, = x,_, +/1 (y, where X is a constan

img038 (14) stereotype n (U20 T32) a fixed idea, especially one that is wrong, that people have

"REALLY SEXY. SIZZLING KIND OF SEXY... MAKES YOU WANT TO MELT IN THE PROCESS."—BITTEN 8Y B

RCover 2 "The Lensmen saga is ą588ł mono/SfiTróm the dawn of science fiction. It s all here—a s

AGH Uniyersity of Science and Technology UST Academic Cenlre for Materials and Nano-technology, whic

Technological quality of the product is highly dependent on characteristics and State of technologic

DIAGNOSIS II: POLYCENTRIC GLOBALISATION World society is coming about not under the Icadcrship of in

photos. In many remote parts of the country this is expensive and time consuming and most of the wor

sa 30 “ N D L I r E ” (Patented) NULI FE is recommend-ed by prominent phys-icians of to-day. is tlić

sa 30 “ N D L I r E ” (Patented) NULI FE is recommend-ed by prominent phys-icians of to-day. is tlić

jff 018 a moderate amount of resistance. The next step is Free-Style practice. CHOOSING YOUR STYLE O

Kelley Armstrong Women of the Otherworld 1 Bitten Cover “Armstrong is up there with the big gir

więcej podobnych podstron