13979 m337$

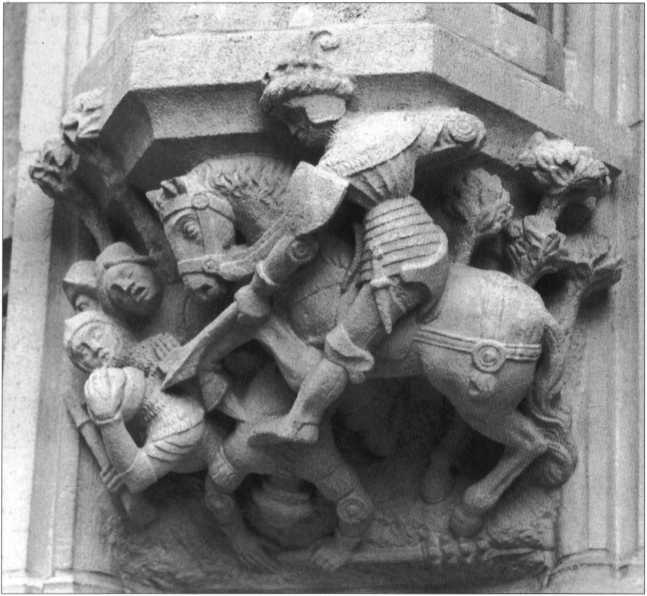

Another carving from the Stadhuis in Leuven portrays a fully armoured knight riding down a group of foot soldiers, perhaps representing the Duke of Burgundy defeating rebels from Gent. (Author’s photo)

war of siege and coun-tersiege. At first, of course, the French were largely on the defensive, and here the ability of towns and castles to defy the English was of paramount importance. Fortunalely for France defence sdll held an advantage over offence in such warfare, and most major sieges were really intensified blockades. Here the main role of a defender’s stone-throwing engines was to destroy the besieger’s siege machines. During the defence of the castle of Bioule in 1346-47, for example, resistance was organised in a concentric manner: first the stone-throwing mangonels and cannon, then the larger ‘two-feet’ crossbows, then ordinary crossbowmen manning (he walls, and finally men dropping rocks on the enemy by hancl. On those occasions when French forces were on

the offensive they, like the English, still relied on blockade,

polluting a water supply, filling a defensive ditch, then approaching the wali with mobile towers or sheds to protect their miners. While besieging La Roche Darien in 1347 Charles of Blois had trees and hedges felled and drainage ditches filled to deny cover for English archers should they attempt a sortie.

lndividual combat skills were also morę sophisticated than was once thought, and by the limę of the Hundred Years War a knight was no mere muscular thng relying solely on the strength of his sword-arm - nor did he indulge in the almost ritualised fencing seen in the 16th century. Instead his attitude towards close combat skills had much in common with modern commando training. Swordplay relied on both cut and thrust, while combat between horsemen armed with lances relied on what might be called the ‘psychological edge’. The natural human tendency to look away shortly before impact was fully recognised, as was the need for constant practice and the selection of weapons suited to an individual’s strength.

The middle years

During the second phase of the Hundred Years War the realities of warfare and the culture of chivalry clashed dramatically for the French noblesse. Whereas honour said that a challenge to battle should never be refused, recent bitter experience argued that it often should be. This led to tortured consciences and sleepless nights for many commanders. Though it was increasingly common for the men-at-arms to dismount to

24

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

m337 The remarkable mid-15th century carvings on the front of the Stadhuis in Leuven are

Fox, Norman ?ctus?valier B ‘ Down from the hills in the early dawn light King Ćonover had co

12572 strona1 (13) How do we say these numbers? Choose from the words in the box. Then listen and 8

6 Abstract The whole application we have created from the basis in Java technology, using applicatio

diagram07 Egg and Dart Moulding from ONE OF THE CARYATIDES FROM THE ErECHTHEUM IN THE British Museum

My na me: Class:Lessons 11-20 Vocabulary 1 Who sald what? Choose from the professlons In the box. Th

Liberation the time in which the toxin is released from the form in which it is administered may be

14 Galii. Leucosiidae m. Urnalana gen. nov. Zool. Med. Leiden 79 (2005) fered from the type in the f

15357 Unit 6 (gr A , strona 1) Class Name VOCABULARY (20 MARKS) 1 Complete the gaps with a verb fr

47389 P1190323 (2) 202 Mirem SgyiłkiwŁk i l.ouct Silesia in the form of the cucinplui From the scttl

2008g (2010) Funnelbeaker Culture artifacts from the settlement in Mozgawa, Pińczów Commune, Świętok

więcej podobnych podstron