64388 S5004015

Coms and potoer in La te Iron Age Britain 28

remained recognisable as a head, though freąuently other 'spirit heads’ would gro w outofit.

In Gallia-Belgica there was also variability, but the main trend here was the abstracdon of Apollo’s features. In difFerent series various aspects such as the flowing locks of hair, the wreath or the eye were exaggerated, undl the link between the odginał image and the resuldng pattem was virtually lost. The now soli tary horse also started to become slightly disjointed, and other objects began to float in the spaces around it.

British coinage derircd largely from the coinage of Gallia-Belgica, and here abstracdon reached its limits. In Dorset everything became a series of abstract dots, while in Lincolnshire the abstractions mainly took the form of crescents. Yet even though abstracdon took place and the man/horse image became difficult to recognise in places, a gradu a 1 lineal descent can always be traced. Only in one area did this abstracted man/horse image give way to another, and that was in East Anglia. Here the horse’s mouth grew larger and its jaws became serrated; it is morę commonly referred to nowadays as the Norfolk wolf (British J: VA6io:EA5-6) .

The dominance of this family of imagery on the gold coin of northem Europę for several centuries, in some regions, is stunning. Why should this newly imported alien form of materiał culture have taken hołd so? Often when a new form of artefact arrives into a society from a different social context, it takes on a new role appropriate to its new social setting. Yet, however coin functioned in Gaul and Britain, the conservadsm in the imagery does beg the quesdon as to why it remained the same for so long. Somedmes objects, simply because of their alien provenance, can become invested with a symbolic value. But this cannot be the answer, or at least not the whole one. The image itself must have had some pardcular significance for it to have remained so constant, and that image must have been surrounded by all sorts of : social taboos to protect it. As I have argued above, I believe that the imagery symbolised the union between the ruler and the land.

The arrival of gold in Britain

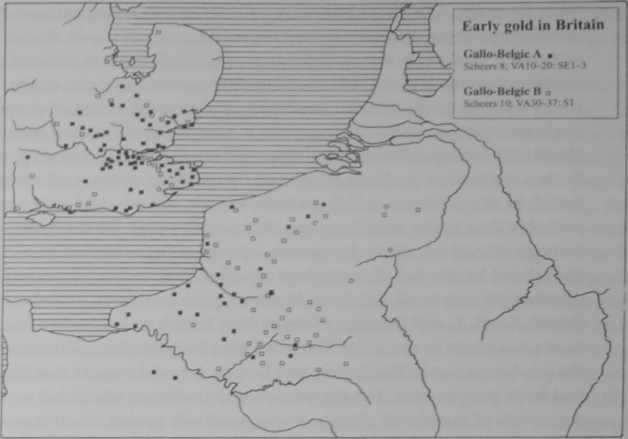

The first coins to appear in any significant numbers in Britain were Gallo-Belgic A (Sch.8:VAio-20:SEi-3) and Gallo-Belgic B (Sch.io:VA30-37*.Si). Their distribu-tion is shown in Fig. 2.2. They are mainly found in north Kent, Hertfordshire and Essex, yet in each case there are also coins found on the south coast from Selsey eastwards for a short stretch. Gallo-Belgic A were probably the earliest - around the mid-second century BC - but their producdon condnued for a long time. Gallo-Belgic B probably appeared at much the same time, though producdon did not condnue for quite so long. Eventually these were succeeded by Gallo-Belgic C (Sch.9:VA42~48:SE4), which appears to have been produced throughout the first half of the first century BC. Whilst all of these are called ‘Gallo-Belgic’ coins, it is quite possible that some of them were actually minted in Britain.

Meanwhile, another sort of coin also began to be produced in Britain in the mid-late second century BC: potin or cast tin-bronze coins. The main findspots for these were again in north Kent and north of the Thames, but here a notę of caudon

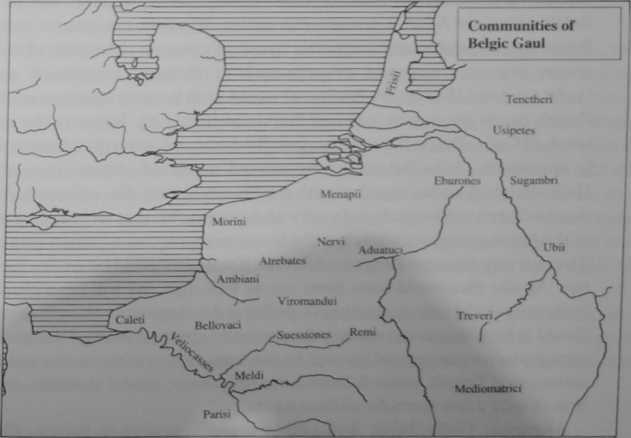

Fig. 2.2 Distribudon map of Gallo-Belgic A, Gallo-Belgic C and the communiries of NE Ga ul

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

S5004023 Coins and power in Lata Iron Age Britain 40 to have been taken over the colour of the early

S5004025 m Coins and potoer iti Late Iron Age Britain 44 represented at female pub

S5004027 Coins and power in Late Iron Age BritainThe various stages of t rance imagery Coins and pow

S5004028 PCoins and pcwer in Lare Iron Age Britain Fik

S5004029 Coins and potuer in Late Iron Age Britain 52 and some other areas have only gone so far as

46870 S5004024 Coins and power in Late Iron Age Britain 42 This effect was the primary driving lorce

więcej podobnych podstron