70737 w01X

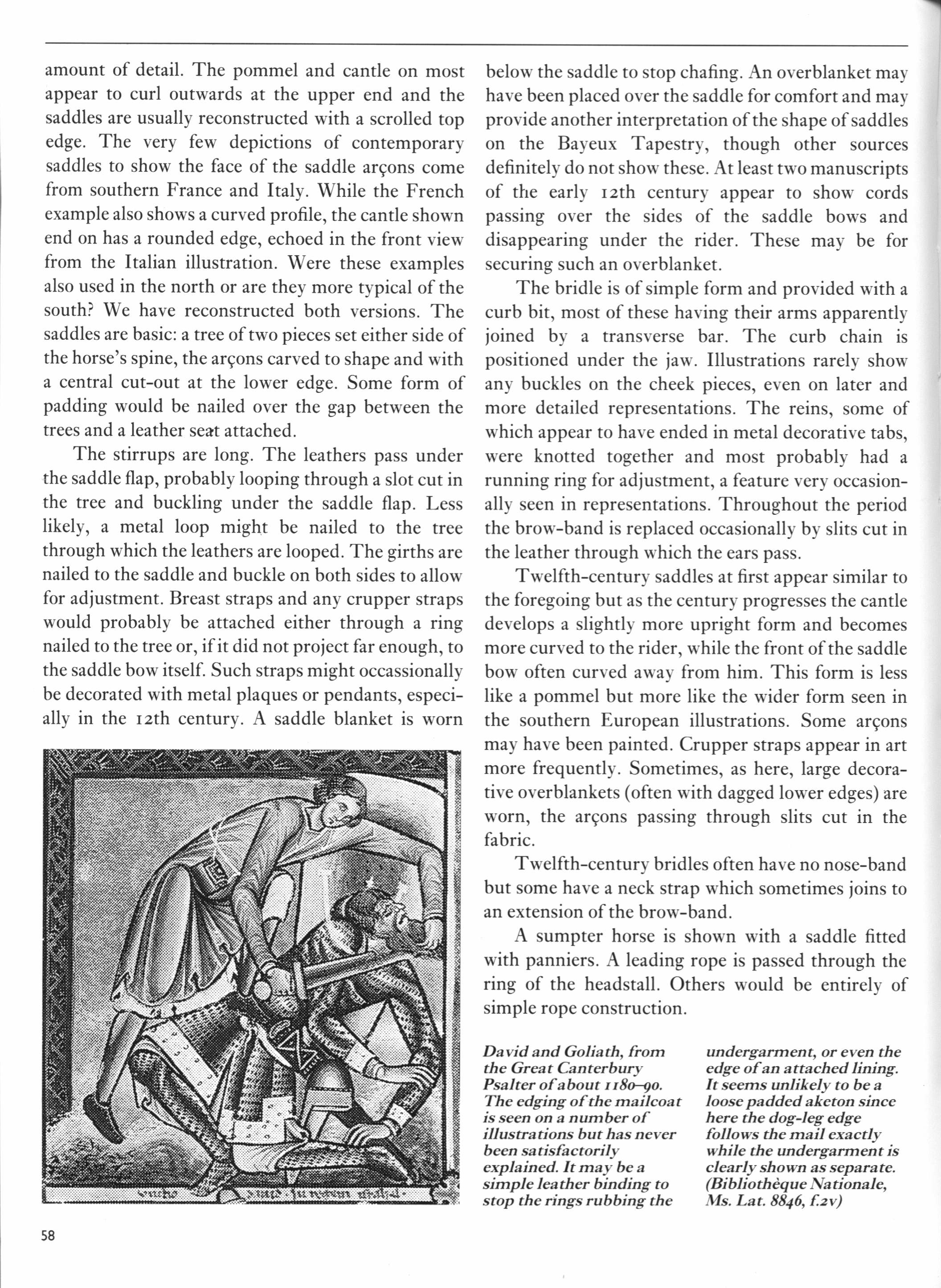

undergarment, or even the edge of an attached lining. It seems unlikely to be a loosc padded akcton sińce here the dog-leg edge follows the mail cxactly while the undergarment is cl early shown as separate. (Bibliotheąue Nationale, XIs. Lat. 8846, f.2v)

amount of detail. The pommel and cantle on most appear to curl outwards at the upper end and the saddles are usually reconstructed with a scrolled top edge. The very few depictions of contemporary saddles to show the face of the saddle aręons come from Southern France and Italy. While the French example also shows a curved profile, the cantle shown end on has a rounded edge, echoed in the front view from the Italian illustration. Were these examples also used in the north or are they morę typical of the south? We have reconstructed both versions. The saddles are basie: a tree of two pieces set either side of the horse’s spine, the aręons carved to shape and with a central cut-out at the lower edge. Some form of padding would be nailed over the gap between the trees and a leather seat attached.

The stirrups are long. The leathers pass under the saddle flap, probably looping through a slot cut in the tree and buckling under the saddle flap. Less likely, a metal loop might be nailed to the tree through which the leathers are looped. The girths are nailed to the saddle and buckie on both sides to allow for adjustment. Breast straps and any crupper straps would probably be attached either through a ring nailed to the tree or, if it did not project far enough, to the saddle bow itself. Such straps might occassionally be decorated with metal plaąues or pendants, especi-ally in the i2th cen tury. A saddle blanket is worn

below the saddle to stop chafing. An overblanket may have been placed over the saddle for comfort and may provide another interpretation of the shape of saddles on the Bayeux Tapestry, though other sources definitely do not show these. At least two manuscripts of the early i2th cen tury appear to show cords passing over the sides of the saddle bows and disappearing under the rider. These may be for securing such an overblanket.

The bridle is of simple form and provided with a curb bit, most of these having their arms apparently joined by a transverse bar. The curb chain is positioned under the jaw. Illustrations rarely show any buckles on the cheek pieces, even on later and morę detailed representations. The reins, some of which appear to have ended in metal decorative tabs, were knotted together and most probably had a running ring for adjustment, a feature very occasion-ally seen in representations. Throughout the period the brow-band is replaced occasionally by slits cut in the leather through which the ears pass.

Twelfth-century saddles at first appear similar to the foregoing but as the century progresses the cantle develops a slightly morę upright form and becomes morę curved to the rider, while the front of the saddle bow often curved away from him. This form is less like a pommel but morę like the wider form seen in the Southern European illustrations. Some aręons may have been painted. Crupper straps appear in art morę freąuently. Sometimes, as here, large decora-tive overblankets (often with dagged lower edges) are worn, the aręons passing through slits cut in the fabric.

Twelfth-century bridles often have no nose-band but some have a neck strap which sometimes joins to an extension of the brow-band.

A sumpter horse is shown with a saddle fitted with panniers. A leading ropę is passed through the ring of the headstall. Others would be entirely of simple ropę construction.

David and Goliath, from the Great Canterbury Psalter ofabout 1180-90.

The edging of the mailcoat is seen on a number of illustrations but has never been satisfactorily explained. It may be a simple leather binding to stop the rings rubbing the

58

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Si LOKESH CHANDRA for the consecration of Ihe two statues. This datę had to be specially auspicious,

It seems nevertheless to be the generał opinion that he cannot long escape the power and malice of t

Back C629 BEST SELLER ROMANCEEcstasyANNĘ WEALE When Suzy Walker won the title of Britain’s Top Secre

GCT02G01 BMP USING THE MOUSE Screen 2 of 3 If the arrow moves over to the edge of the screen, or if

skanuj0173 „Strategie mangement is a stream of decisions and actions which leads to the development

koli1aa Take your first stitch Follow the arrows at the edge of the chart to where they meet. This s

172 A. Wyszomirski even the process of applying for hosting a big event (e.g. EXPO ) is important, b

172 A. Wyszomirski even the process of applying for hosting a big event (e.g. EXPO ) is important, b

htdctmw 073 DRAWING THE HUMAŃ HEAD! Or even the inhuman head— we’re not prejudiced!

image042 (3) Selecl (or Enter) the Name of the Poły mer here

3536f77b0d3b2e31303a32fc8d4300f5 ST1TCHING/ - cross & half cross stitches Follow the arrows at t

183 ----, D. R. F. Taylor, eds.,(1981): Development form Above or Balów? The Dlale

Diagnosis & laboratory testing To rule out or confirm the diagnosis of paralytic poliomyelitis.

CCF20100109�002 TOPIĆ SENTHNCES - advanced Topie scntenccs can bc positioned at the beginning, in th

więcej podobnych podstron