82 (123)

158 The Viking Age in Denmark

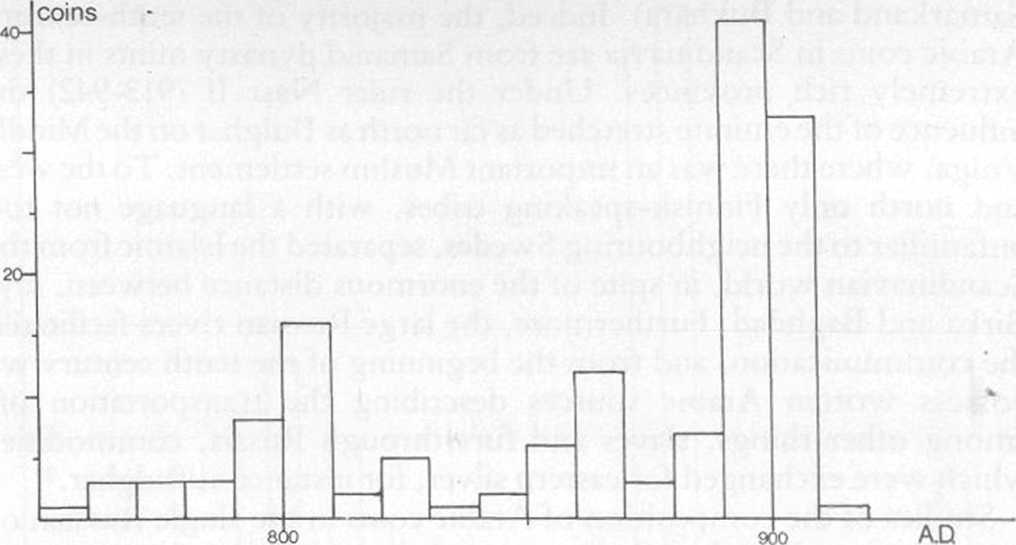

Figurc 48 Distribution of Arabie coins in an carly tenth-century silver-hoard from Over Randlcv, east Jylland

tails and are madc up almost entircly of new coins (Fig. 52).36 This signifies, for instancc, that Russia, almost dcvoid of Arabie coins in the latcr ninth century, received a large stock of new coins at the beginning of the tenth century, which explains why the tenth-century hoards hołd few old Arabie coins as compared with new ones. On the other hand, the hoards in the Islamie world before 800 often have long, quite powerful tails, sińce they are madę up of both old and new coins (Fig. 51).37 This observation explains the long tails of the Russian and Scandinavian finds of the ninth century. Furthermore, it demonstrates that the many solitary eighth-century Arabie coin finds in Scandinavia were most probably part of the generał ninth-century importation and not a result of pre-Viking Age contacts. This accords with the dates of the hoards too; in both Russia and Scandinavia the earliest hoards with Arabie coins stem from the 780s.38 Incidentally, the composition of the eighth-ccntury hoards in the Islamie world throws some doubts on the effect of the famed reform of coinage of'Abd al-Malik in about 700.39

As noted, the composition of the hoards is caused by several factors: import, export and consumption. But not infrequently the patterns, as Dolin puts it, are taken to reflect the export flow only.40 The heavy tails would thus mean that the old coins were piling up, because of the decline or absence of exporting, while new ones were still coming in. But this easily leads to false conclusions. For instance, the powerful tails of the hoards of the mid-tenth century reflect a period of strong importation, followed by a decline. The export, and the consumption, are regarded as merely dependent on the size of the import.

Bolin saw the Arabie silver flowing frcely through Scandinavia and into western Europę from 850 and until the appearance of the taił with powerful termination in the hoards, before 950. Bolin’s reasons for not

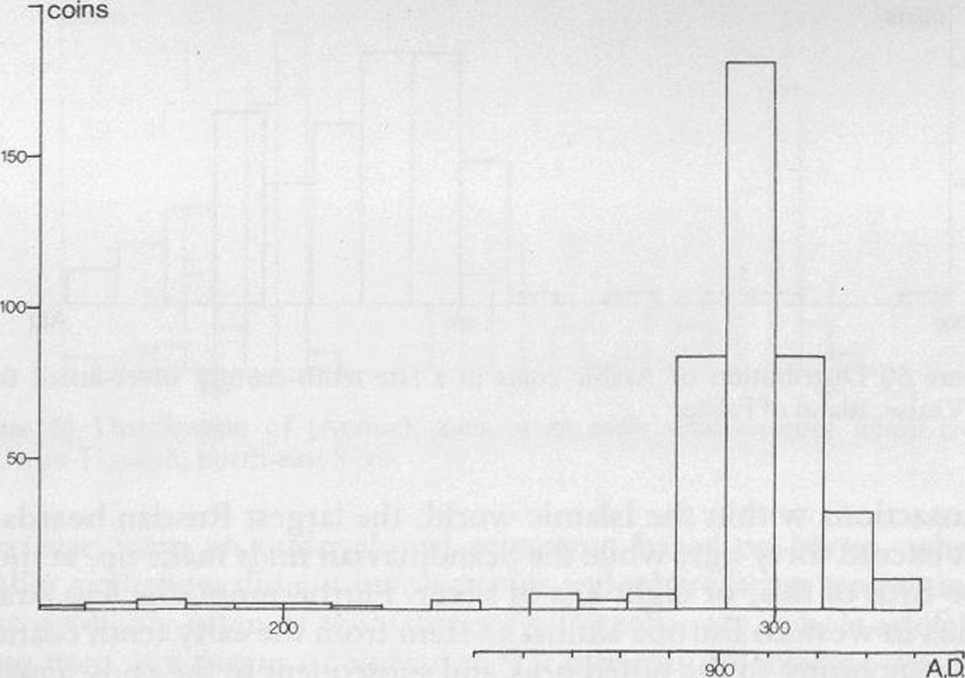

Figurc 49 Distribution of Arabie coins in a mid-tenth-ccntury silvcr-hoard from • Terslev, Sjaelland

admitting Arabie coins into Southern Scandinavia, and from there to the west, before 850 are weak, sińce we have, among other things, four hoards from Denmark with such coins and a terminus post quem before 850.41 For the period 800 to 850 Bolin saw a Frankish dominance in coins, reflecting west European purchases of, among other things, slaves and furs for sale to the Islamie world. In about 850 the Scandinavians took over the transactions themselves, using the trade routes through Russia. As a result, Arabie silver now flowed into Scandinavia and gave the Vikings the background for launching their attacks on western Europę. Furthermore, this silver, according to Bolin, should have caused an expansion of the western economy in the same period.

According to our own discoveries, the raids in western Europę correspond to the drastic decline in silver of the later ninth century. This was not noted by Bolin. Furthermore, Arabie coins are ex-tremely rare in the west, though this may be because they were melted down, sińce the quality of the Arabie silver coins is very fine. Moreover their use as a means of payment, being non-Christian and of another standard, in countries with a morę or less controlled coinage, was limited and difficult. In fact, we have little knowledge of the amount of silver flowing from, say, Samarkand to London via Bulghar and Hedeby.42 But it may have been fairly modest. At Hedeby Arabie coins do not outnumber Danish and west European coins;43 and while gigantic amounts of silver were involved in single

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

80 (129) 154 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 44 Distribution of Arabie coins in a sam ple of north-

83 (120) 160 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 50 Distribution of Arabie coins in a late tenth-centur

81 (117) 156 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 46 Distribution of Arabie coins in a samplc of castcrn

57 (213) 108 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę IV. Silvcr and copper dccorated spurs, length about 21

58 (195) 110 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę VI. Sample from late tenth-century silver-hoard at Taru

60 (189) 114 The Viking Age in Denmark Platc X. Ship-sctting and runestonc (on smali mound) at Glave

62 (179) 118 The Viking Age in Denmark Plato XIV. Iron tools from a tenth-ccntury hoard atTjclc, nor

63 (170) 120 The Viking Age in Denmark % Platę XVI Pagc with illustration of an English manuscript f

64 (171) 122 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 30 Distribution of wealth in three cemeteries as measu

66 (160) 126 The Viking Age in Denmark have becn fouhd (Figs 32-3).7 They stem from thc same provinc

68 (153) 130 The Viking Age in Denmark two tortoise bucklcs to reprcsent wornen of high standing, th

69 (151) 132 The Viking Age in Denmark heavy cavalry burials, fincr wcapon graves of thc simple type

70 (150) 134 The Viking Age in Denmark cemetcry at Lejre on Sjaelland a dccapitatcd and ticd man was

74 (134) 142 The Viking Age in Denmark 5C~ł silver 800 900 kxx) A.D. Figurę 37 Fluctuations in che r

75 (129) 144 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 38 Average weight ofthesilver-hoardsofthe period 900 t

27 (504) 48 The Viking Age in Denmark Europcan meteorological data for earlier per

29 (466) 52 The Viking Age in Denmark We have already mentioned the expansion of grasses, and it is

30 (454) 54 The Viking Age in Denmark touch, so the political developmcnt we have described in previ

31 (444) 56 The Viking Age in Denmark pig SO- A horse B 50- 50 cattle 50" sheep (Qoat) Figurę 1

więcej podobnych podstron