75 (129)

144 The Viking Age in Denmark

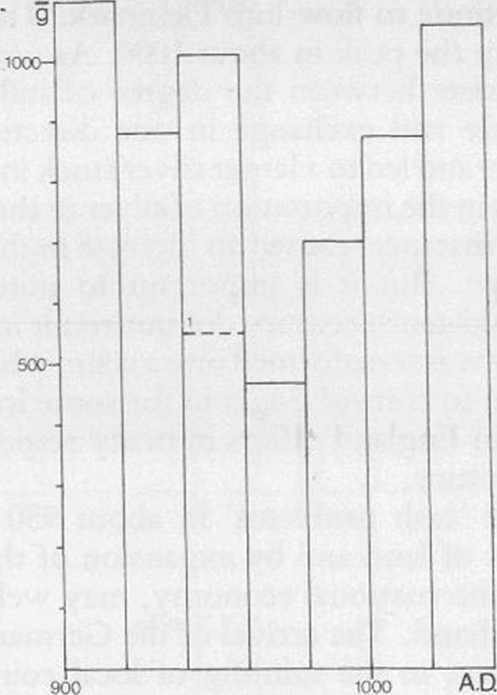

Figurę 38 Average weight ofthesilver-hoardsofthe period 900 to 1040 A.D. (1) gives the averagc if the Terslev-find (Appendix XI) is omitted, the largest of the period

population of the island (2.01). This could stem from geographical conditions, the inland area being relatively smali, but cven with a K-value like that held by nearby Skane, Bornholm holds the highest amount of silver in Denmark (0.84, or, with the K-value for only south Skane, 0.88). This, incidentally, makes the suggested riches of another island of the Baltic, Gotland, morę credible and not merely a result ofthe exposure to piracy with an accompanying high freąuency of deposition (cf. below). Northern Jylland (silvcr amount 0.05) and Fyn plus the surrounding islands (0.09) have very little silvcr. South Jylland, including the Jelling province, is rclatively rich (0.16), especially if Southern Slesvig is excluded (0.20). (Fyn together with the latter area make 0.07.) Sjadland and surrounding islands come next to Bornholm in their riches (silver amount 0.70), while Skane is morę on the level of south Jylland, having 0.19 as index. South-westcrn Skane alone is 0.22, while north-eastern Skane, together with the neigh-bouring provinces of Halland and Blekinge, makes 0.13 (Fig. 39).

Leaving Bornholm aside, Sjaelland is, perhaps unexpectedly, the wealthiest zonę in the tenth to early eleventh century (most finds stemming from the second half of the tenth century). On the other hand, Sjaelland and surrounding islands make up the largest area of high-quality soils in Denmark and must have been quite densely populated, though with much forest. To the west of Sjaelland, the border areas of the early Jelling State, characterised by their for-tifications, cavalry graves and weapon graves, etc., are poor in silver in spite of the presence of depcndants of the centre. But here we have suggested that grants of land, and not cash paymcnts, were used as compensations tor military and other obligations. The land may have been taken from rebel groups, for instance, and the grants augmented by the silver decline around 950. The province housing Jelling was in possession of morę silver. Apart from sheer poverty, which we may detect in the marginal provinces of Halland, north-eastern Skane and Blekinge, the little silver in western Denmark is most probably due to investments in various enterprises, like the fortresses, and the buying, for instance, of luxuries or even food-stuffs, such as the Slavonian rye found at the Fyrkat fortress.9 It is obviously important to look further into the social aspects ofthe distribution ofsilver.

The average weight of the hoards also has a significance, indicating much in a different and independent way about the size of the silver stock, as measured against the division of wealth among the higher echelons. We expect the amount of silver in an area to correlate with the average weight, as was the case in the abovc study of the time trends (Appendix XIV). Bornholm, however, has a very Iow value, only 365g, in spite of the large stock of silver. The social conditions were probably quite cqual on the isolated and rather smali island. For south Jylland the average is relatively high, 1155g, and, excluding Southern Slesvig, 1422g. Still higher comes the Sjaelland island group with 2001 g, while north Jylland and Fyn have, respectively, 339g and 488g. Skane makes 688g, or, without the north-eastern part, 743g. Halland, Blekinge and north-eastern Skane amount to 394g. Apart from the deviating result on Bornholm, the picture corresponds well, as expected, with the above calculations of the size of the silver stock.

In the ninth century, Southern Jylland may have been the wealthiest area, the hoards having an average weight of 1033g with 192g only for the rest of Denmark. Only three ninth-century fmds above 500g are madę, all from south Jylland (Appendix XIII).

A preliminary ‘degree of social stratification’, built on the ratio of silver hoards, respectively above and below 500g, can be established for the finds from the period 900 to 1010. T he picture corresponds, as expected, to the above scatter of the average weight. The morę finds over 500g in an area, as compared with the number of finds below 500g, the higher the average weight of silver hoards, and the higher the preliminary degrec of social stratification. To arrive at the true degree of stratification we must divide the preliminary values by the corresponding measures for the amounts ofsilvcr in the various areas, sińce the latter distort the picture of the social division of wealth, when using a fixed intersection, the 5(X)g.

The preliminary degree of social stratification for the ninth century is 0.30 (three finds above 500g divided by ten below7; cf. Appendix XIII). The observed amount of silver is 6705g and the K-value 0.08 (one inland find divided by thirteen in all); the standardiscd amount is 6705

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

86 (111) 166 The Viking Age in Denmark 166 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 56 Coin-dated silver hoa

80 (129) 154 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 44 Distribution of Arabie coins in a sam ple of north-

81 (117) 156 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 46 Distribution of Arabie coins in a samplc of castcrn

49 (253) 92 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 25 Reconstructed tcnth-century pit-houses of the town o

50 (241) 94 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 26 Part of thc city of Lund (Skinę) at the beginning of

22 (669) 38 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 8 B. ‘Aftcr Jelling’ Stones in southernmost Jylland. Si

57 (213) 108 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę IV. Silvcr and copper dccorated spurs, length about 21

58 (195) 110 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę VI. Sample from late tenth-century silver-hoard at Taru

60 (189) 114 The Viking Age in Denmark Platc X. Ship-sctting and runestonc (on smali mound) at Glave

62 (179) 118 The Viking Age in Denmark Plato XIV. Iron tools from a tenth-ccntury hoard atTjclc, nor

63 (170) 120 The Viking Age in Denmark % Platę XVI Pagc with illustration of an English manuscript f

64 (171) 122 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 30 Distribution of wealth in three cemeteries as measu

66 (160) 126 The Viking Age in Denmark have becn fouhd (Figs 32-3).7 They stem from thc same provinc

68 (153) 130 The Viking Age in Denmark two tortoise bucklcs to reprcsent wornen of high standing, th

69 (151) 132 The Viking Age in Denmark heavy cavalry burials, fincr wcapon graves of thc simple type

70 (150) 134 The Viking Age in Denmark cemetcry at Lejre on Sjaelland a dccapitatcd and ticd man was

74 (134) 142 The Viking Age in Denmark 5C~ł silver 800 900 kxx) A.D. Figurę 37 Fluctuations in che r

27 (504) 48 The Viking Age in Denmark Europcan meteorological data for earlier per

29 (466) 52 The Viking Age in Denmark We have already mentioned the expansion of grasses, and it is

więcej podobnych podstron