86 (111)

166 The Viking Age in Denmark

166 The Viking Age in Denmark

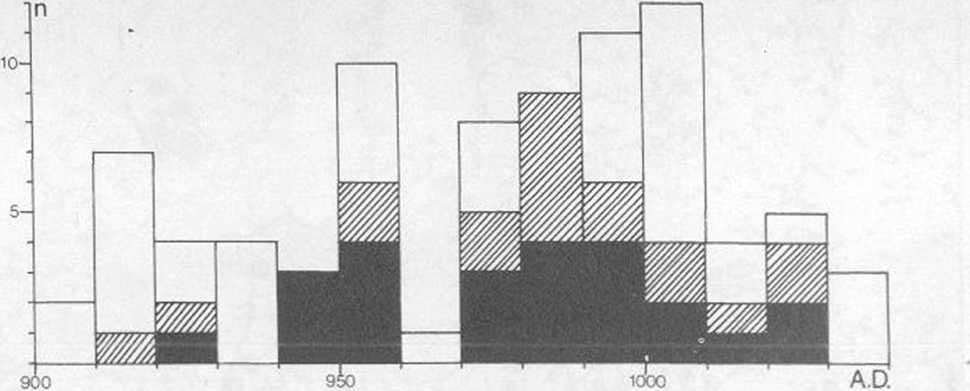

Figurę 56 Coin-dated silver hoards of the period 900 to 1040 A.D. by dccades and according to distance from open water. Whitc signature = 0-4 kilometres from open water; striatcd = 5-9 kilometres from open water; and black = 10, or morę, kilometres from open water. (Appendix XI)

%

political/historical record may not have directly affectcd the popu-lation at largo.

The Southern pressure is morę clearly demonstrated in the periods of minting at Hedeby. It is hardly an accident that the first Nordic coins belong to the phase of Frankish interest in Denmark in the first half of the ninth century, corresponding to the early peak in silvcr and the intemational contacts with both east and west. The first halfof the ninth century also saw the important controlled planning of Hedeby and the establishment of the first churches in the Southern Jylland towns.

The late ninth century, the generał period of decline, saw the abolition of thesc relations and institutions. At the beginning of the tenth century the new influx of silver and expansion of trade involved the west too, leading to the German attack of 934 on the riches of Hedeby, where minting was renewed. Further southem pressure is scen in the nomination of the first bishops in 948, but at this time a new depression of silver, among other things, led to a number of changes in Danish society, including King Harald’s conversion to Christianity. Shortly afterwards the German emperor sought to emphasise his impact on the Danish bishops, but probably in vain.

A flow of German silver, corresponding to an increase in trade relations, is parallel to the attack in 974, but also to a modernisation of the economy, including a wider use of coins and the first local mass-minting. In 988 the German nomination of a bishop for Odense took place in a country which now was different in every important institution from the Denmark of King Godfred, two hundred years earlier, though the integration of the east was probably not yet complete.

Although the German impact was now slackening for the time being, and wras to some extent substituted for by an English one - for instance, in the case of coins - and Denmark had become a political unity, set apart from its neighbours, the country was also on the way to being transformed into a west European State.

Chapter 8

SUMMARY

In the last half of the first millennium began a period of climatic optimum. This was accompanied by a population growth and a development of the subsistence economy, not only in size but also in kind; the previous stress on the rearing of animals, for instance, was checked by an expansion of cereal-growing, in which rye became morę common, though barley was still the major crop. The emphasis on plant protein led to a larger population than cver before, though the ratio between agricultural (open) lands and forest was no larger in 800 than it had been at the beginning of the millennium. That period had been another phase of climatic optimum, whereas the centuries around 500 A.D. suffered severe hardships of cold, wet weather, poor harvests and a relatively smali population.

Agricultural expansion was aidcd also by new tools, such as the wheel-plough, while the settlement pattern remained much the same as before. Villages were apparently regulated, and contained single farmsteads, madę up of one or morę long-houses on a traditional model, with both living quarters and the stable under the same roof, with associated minor buildings for craft and other activities. Sonie socio-economic ranking within the villagcs is seen in a few major farms. But in the tenth century another type of farm develops, the magnate estate, with fine living quarters separated from the rest of the buildings, having special functions and lying along the perimeter of the large courtyard. The magnate farms had so far appeared only in western Denmark, but here we have other reasons to expect elear social divisions of the population in the tenth century. The common villages were also restructured at the end of the Viking Age.

International exchange had already been practised for five thousand years in Denmark, but in the eighth century the ports of Hedeby, and especially of Ribe, were established to facilitate the trade with western Europę. In 800 Hedeby, protected by the Danevirke frontier walls, was laid out as a planned settlement and dcveloped into a major centre of exchange, and of the transit of goods and persons between the

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

75 (129) 144 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 38 Average weight ofthesilver-hoardsofthe period 900 t

Go to www.menti.com and use the codę 97 86 68What are the first words to come to your mind about Cor

ISSUES IN INFORMATION SCIENCE - INFORMATION STUDIES Ihe core purpose of this journal is to provide

2 The Soviate preferred to look for freeh racruite, suoh aa Wanda osilewska for estadia. In the peri

69 (151) 132 The Viking Age in Denmark heavy cavalry burials, fincr wcapon graves of thc simple type

81 (117) 156 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 46 Distribution of Arabie coins in a samplc of castcrn

49 (253) 92 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 25 Reconstructed tcnth-century pit-houses of the town o

50 (241) 94 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 26 Part of thc city of Lund (Skinę) at the beginning of

22 (669) 38 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 8 B. ‘Aftcr Jelling’ Stones in southernmost Jylland. Si

26 (518) 46 The Viking Age in Denmark Draved Mosc Prollle 1959 Figurę 10 Fluctuations in the degree

47 (269) 88 The Yiking Age in Denmark Figurę 24 Reconstruction of ninth-century house from the centr

m85$ Viking swords found in the Thames and River Witham: all belong to the period after c. 950. supp

5 Tanzimat and “Mecelle” 111 land law was accepted in 185825. The exclusion of the possession o

f14 8 The Field Guide to North American Males A lovely book by Mariorie Ingall F orlhc oming in F eb

fund to Id in the dotted lines to make creases and fold back / s i Iver paper The

00055 ?8eb8f33682dd4ffedb872005d8a4b1 54 Hembree & Zimmer quite a while for discussion of the K

00100 ?e6667c29dfdea3c59f1657bb3f2b02 99 The OCAP manufacturing process remains in an unknown State

więcej podobnych podstron