79 (124)

152 The Viking Age in Denmark

Roskilde, in the newly won provinces, were the most important localities. A monopoly silver coinage, however, was not cstablishcd until the end of the eleventh cen tury, while many foreign coins of smali denomination were still circulating widely. The number of Sven’s coins is very smali, and at the beginning of this century only four were known, from four localities, as compared with 32 ninth-century and 588 tenth-century coins of the earlier types.21 In this survey the number of Knud coins was 492 (from 59 localities), while the number of coins of Hardeknud, the son of King Knud, was 633, from 36 finds.

By this period the coins were probably serving as an all-purpose rneans of exchange, though they may still have been put into circulation on special occasions, for instance as payments to the army. Considering their propaganda value, it is hardly coincidence that most of the coins were struck to the east of Storę Baelt, and not in the Jelling homelands to the west.

D. 7'rade and imported siher: the Arab connection

In the Danish silver hoards of the ninth century we have at least 113 Arabie coins as compared with 33 west European, mainly Frankish coins, and no Nordic ones. The same picture is seen for the port of Kaupang in Norway, and for Birka too. At Kaupang we have 20 Arabie coins, four west European coins and one Nordic coin.22 From the graves at the mid-Swedish township of Birka come 10 west European, 30 Nordic and 46 Arabie coins, many of them used as trinkets.23 Only at Hcdeby do the Nordic and west European coins, throughout the Viking Ago, occur morę often than the Arabie ones,21 which, however, are three or morę times as heavy as the European specimens.

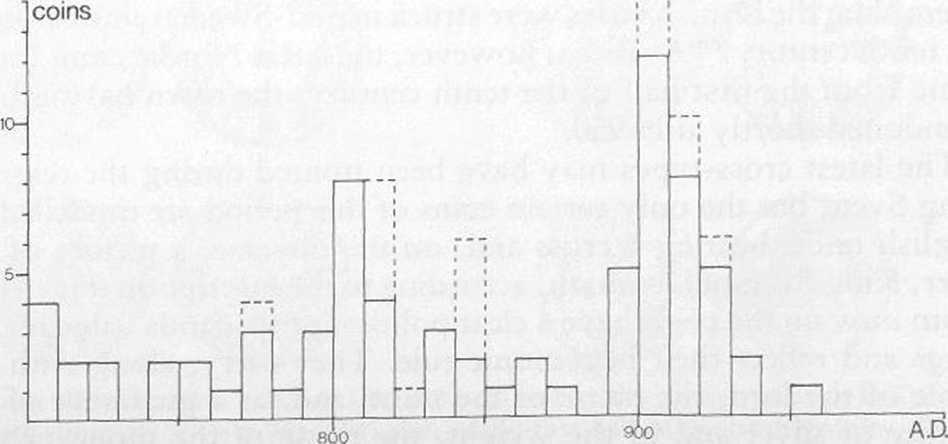

Figuro 42 Distribution ot" Arabio and (indicatcd by broken lineś) west European, and a couplc ofByzantinc coins of the graves from Birka, mid-Swedcn

Studying the dates of the ninth-ccntury coins, the Arabie coins concentrate in the early half of the century. At Birka, for instance, 17 coins are from between 8(X) and 850 (20 before 800, but probably also bclonging to the ninth-century period of importation), while only three stem from 850 to 890 (Fig. 42). The west European coins also cluster in the early half of the century. (The datę of the Nordic coins is not commented upon, sińce it is dependent on the imported ones.) The Kaupang picture is similar, but the number of coins is much smaller. In sum, we obscrve an early period of the ninth century with international contacts and, as we have seen above, a sizablc silver stock, followed by a period of little trade and a shrinking amount of silver. This latter phase corresponds to the major Viking raids in western Europę, which must be viewed in the light of competition for scarce surpluses. (We should also remind ourselves that the ninth century might have witnessed a climatic depression with conse-quences for the harvest.) Nevertheless, little silver was carried back to the Scandinavian homelands, to judge by the coin dates.

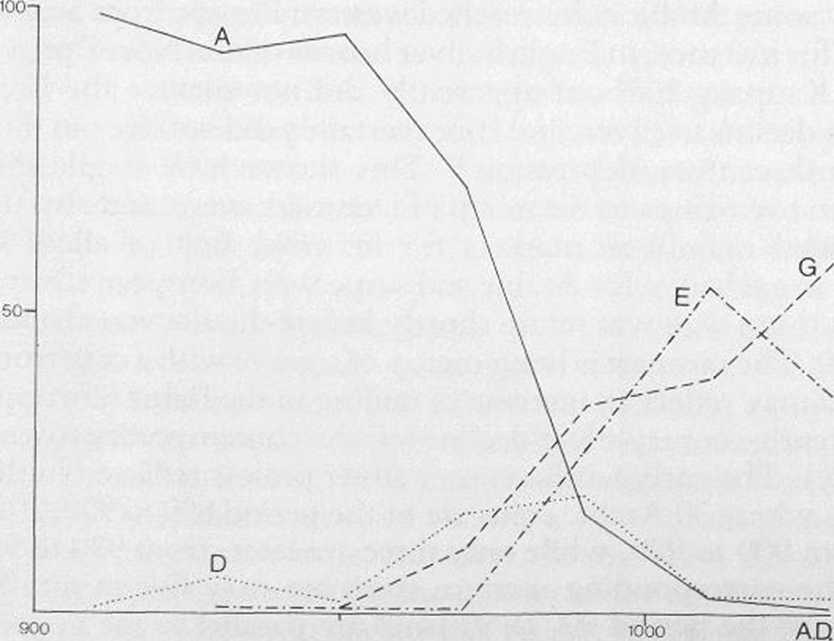

Moving on in time, the Arabie coins become very common from about 890, corresponding to the major peak in the amount of silver at the beginning of the tenth century. Soon after, howevcr, in the middle of the century, the Arabie coins disappear almost completely (Fig. 43). A German25 and, a little later, an English importation of coin began in the second half ot the tenth century, but the west European coins did not make up for the eastern losses, which put the silver stock at its lowest in about 950. Furthermore, at the beginning of the tenth

Figurc 43 Percentages of rcspectivcly Arabie (unbrokcn lines), German (broken lines), English (broken lines with points) and Nordic, basically Danish (lines of points) coins in the silvcr-hoards of the period 900 to 1040 A.D.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

78 (124) 150 The Viking Age in Denmark Figuro 41 Danish coins, c. 800 to 1035 A.D. (1) = ‘Hcdeby’ co

57 (213) 108 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę IV. Silvcr and copper dccorated spurs, length about 21

58 (195) 110 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę VI. Sample from late tenth-century silver-hoard at Taru

60 (189) 114 The Viking Age in Denmark Platc X. Ship-sctting and runestonc (on smali mound) at Glave

62 (179) 118 The Viking Age in Denmark Plato XIV. Iron tools from a tenth-ccntury hoard atTjclc, nor

63 (170) 120 The Viking Age in Denmark % Platę XVI Pagc with illustration of an English manuscript f

64 (171) 122 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 30 Distribution of wealth in three cemeteries as measu

66 (160) 126 The Viking Age in Denmark have becn fouhd (Figs 32-3).7 They stem from thc same provinc

68 (153) 130 The Viking Age in Denmark two tortoise bucklcs to reprcsent wornen of high standing, th

69 (151) 132 The Viking Age in Denmark heavy cavalry burials, fincr wcapon graves of thc simple type

70 (150) 134 The Viking Age in Denmark cemetcry at Lejre on Sjaelland a dccapitatcd and ticd man was

74 (134) 142 The Viking Age in Denmark 5C~ł silver 800 900 kxx) A.D. Figurę 37 Fluctuations in che r

75 (129) 144 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 38 Average weight ofthesilver-hoardsofthe period 900 t

27 (504) 48 The Viking Age in Denmark Europcan meteorological data for earlier per

29 (466) 52 The Viking Age in Denmark We have already mentioned the expansion of grasses, and it is

30 (454) 54 The Viking Age in Denmark touch, so the political developmcnt we have described in previ

31 (444) 56 The Viking Age in Denmark pig SO- A horse B 50- 50 cattle 50" sheep (Qoat) Figurę 1

32 (433) 58 The Viking Age in Denmark and from a rurąl scttlemcnt, Elisenhof, less than fifty kilome

80 (129) 154 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 44 Distribution of Arabie coins in a sam ple of north-

więcej podobnych podstron