8342937076

EFFECTS OF SO., & N02 SINGLY OR IN COMBINATION ON GROWTH PERFORMANCE OF COCOA MIRlpS

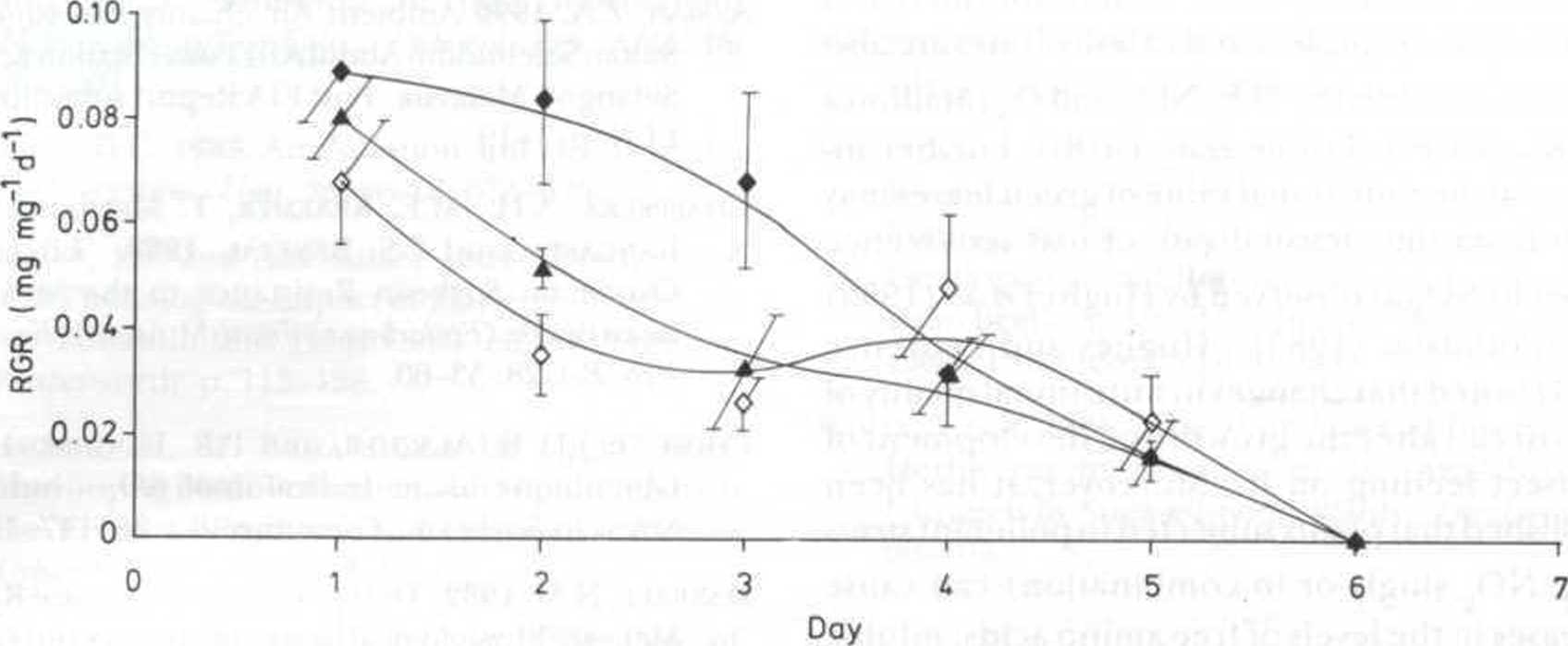

Fig. 6: Progress curues ojminds relatiyegrowth rateexposed to 0.030 + 0.035 ppm ofSO2 + NOy

A control. ♦ mińds and cocoa shoolsfumigatedsimultan*ously;Q mińdsfedonpostfumigated shoots. The plots were of mean yalues with 95 % conjidence limits

However, based on cumulative weights, FIL treatment recordcd 12-15% higher va)ues comparedtotheothertwotreatments. In contrasc, exposure to NO., resulted in significant differences between treatments for mean weights (P<0.05 level) and cumulative weights (P<0.01 level). Combination of the two pollutants at lower concentrationsalsoshowed significant difTerences in mean and cumulative weights (P<0.01 level). Growth stimulation due to fumigation of the host plant together with nymphs provides valuable insightsinto therelation between doseof pollutant and response of the insect as suggested by Hughes et al. (1985). Field observations by Jaeger et al. (1972) in artificial fumigation experimentsshowed that the mexican bean beetle (Epilachna varivestis Mulsant) larvae fed on SO., fumigated soybeans (Giycine maxL.) developed faster, grew larger, had lower mortality and exhibited a distinct feeding preference for fumigated leavesover Controls. These findings are in agreement with the results of this study utili/.ingelevated NO., and SO., concentradons or NO., and SO., in combination which showed better growth stimulation when nymphs and leaves of the host plant were exposed simultaneously to the pollutant. These resultssuggest that the ratę of uptake of SOg either singly or in combination (NO., + S02) may be morę important in explaining the effects on the insects than the total dose. Alstad and

Edmunds (1982) pointed out that the degree of

50., toxicity below the threshold levels of foliar in jury compared to NO., at the same concentration isverymuch higher on plan ts which provide greater impacton physiologicalchangessuchasan increase in freeaminoacidsin thefoliage. providingagood source of food for the nymphs. On the contrary, Hughes etd\. (1985) noted that the reduced cjuality ofleavesas food (due to detrimental effects of the pollutantson plant metabolism and celi integrity) may impair insect growth. He also proposed that the poor growth of insects feeding on foliage exposed to pollutant concentradons exceeding the foliar injury threshold level was primarily the consequence of tissue damage and necrosiscaused by the pollutant.

The possibility that the pollutants had a direct effect on the insects is minima! sińce the concentra-tionsof the pollutants used in these experiments were relatively Iow. Dohmen etaL (1984) reported that direct fumigation ofaphids (AphisfabaeScop.)

with SO., and NO., (at 400 /igm”^ and 400/igm"3 respectively) feeding on artificial diets produced no significant differences in growth. In contrast, the mean relative growth rates ofaphids gro wn on

post-fumigation plants (SO., and NO.,) caused significant increases in aphid performance. Using

50., - treated soybean on mexican bean beetles (MBB), Chiment et ai (1986) showed a direct

11

PERT ANI KA VOL. 14 NO.l. 1991

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Pertamk. 14(1). 7-13(1991)The Effects of S02 and NO,, Singly or in Combination on the Growth Perform

Stitch Yariations Any stitch can be worked in this way, singly, or in a group, or cluster. A ‘raised

variable that combines the effects of frequency and temperaturę. In view of the fact that all

xvii humidity in (a) or minimal temperaturę in (b). Residual minimal absolute humidity Controls for

00169 ?8fdc7697ba8e0e2234fcfe61c09204 170 McWilliams satisfy ^3 = r/0 = T] + T2. In addition to exa

img012 3 17. In winter months loads stacked outside may be covered in ice and snów, the effect of&nb

Programmes of Study in English (or in other languages) • BA in Polish Sludies •

Doctoral dissertation: The Analysis of Economieal Effects of Implementation of Selected Metaheuristi

Effect Of Dividends On Slock Prices 4 is affected by managerial and behavioral environment in U.S. T

Effect Of Dividends On Slock Prices 5 dividend policy in a new way. Discussion of dividend policy ca

Effect Of Dividends On Slock Prices 7 that can be in accordance with the expectations of their share

18 Małgorzata Bednarczyk, Ewa Wszendybył-Skulska According to the model presented in Figurę 2, the e

więcej podobnych podstron